Abstract

In this biomechanics study, we compared the use of knot fixation or backstitching at the end of a continuous suture with the use of conventional absorbable sutures to close a porcine stomach incision. We then evaluated whether the backstitching method could be considered a novel, surgical, knot-free closure technique. A total of 40 suturing samples were obtained and divided into 20 samples from the posterior wall and 20 from the anterior wall. These sets of 20 samples were then randomly grouped into the backstitching group and the knotting group, with 10 samples per group for each associated wall. Biomechanical tests were performed to compare the maximum load and tensile stiffness differences between the backstitching group and the knotting group. The maximum load and tensile stiffness differences between the backstitching group and the knotting group were not significant for the posterior or anterior walls of the porcine stomach. The use of backstitching at the end of an incision with continuous conventional absorbable sutures provides similar biomechanical properties to those of knot fixation, and the backstitching method shows promise as a novel surgical knot-free closure technique.

Keywords: Porcine stomach, Absorbable sutures, Suture, Backstitching, Biomechanical

Subject terms: Medical research, Biophysics

Introduction

The laparoscopic technique is an important minimally invasive surgical method in modern surgery, featuring minimal trauma and fast recovery. With continuous breakthroughs that have overcome many technical barriers, laparoscopic technology has developed from simple laparoscopy to a variety of complex laparoscopic surgeries, and two-port and single-port laparoscopic surgeries have been derived from multiple-port laparoscopic surgeries. However, the creation of laparoscopic knots is challenging, especially when the end of a continuous suture needs to be knotted; consequently, these knots create a barrier to the widespread use of laparoscopy. Owing to a certain amount of tension, an assistant is often needed to fix the first knot, which restricts the development of minimally invasive techniques such as single-port laparoscopy to some extent. To address this technological challenge, equipment such as ligating clips and V-loc™ barbed sutures has emerged1–3. These types of equipment have unique advantages and disadvantages in various applications, such as suboptimal suture holding strength when using ligating clips and the relatively high cost of V-loc™ barbed sutures. With future improvements in suturing technology, will it be possible to use conventional absorbable sutures without having to tie knots? This is an interesting question.

An examination of the sewing process used for clothes reveals an interesting phenomenon: although most seam ends are not knotted, they are still extremely strong. The reason for this is that the backstitching method used in sewing plays a very important role. A further literature review revealed that the backstitching method was widely used in sewing several centuries ago4. Is it possible to achieve a similar effect when applying this ancient method to suture tissues during surgery? To explore this question, the biomechanical differences between the use of knot fixation and backstitching at the end of a continuous suture with conventional absorbable sutures to close tissues were examined. We hypothesized that the backstitching method could provide biomechanical properties comparable to those of the knotting method and that the backstitching method could further promote the development of minimally invasive surgical techniques.

Materials and methods

Selection of suture tissue

To simulate human myometrium or vaginal wall suturing, porcine stomachs were used in this study. All the porcine stomach samples were obtained from the same slaughterhouse (Angu Town slaughterhouse, Shizhong District, Leshan City, Sichuan Province). The pigs were slaughtered in the early morning of the same day. The omentum and fat adhering to the stomach wall were removed by the staff at the slaughterhouse. Each porcine stomach was subsequently rinsed with tap water, and 20 porcine stomachs with appropriate weights were selected for this study. Good ventilation was maintained in the slaughtering area. All operations were performed in accordance with the “Operating Procedures of Livestock and Poultry Slaughtering—Pig” in China (standard number: GB/T 17236-2019). Since this study was an exploratory pilot study, given the research budget, we selected 20 porcine stomachs with an average weight of 0.69 ± 0.07 kg as the research objects. In accordance with the regulations of the Experimental Animal Management Committee of Sichuan Province, the use of porcine stomachs from a slaughterhouse for research purposes did not require approval from an ethics committee. The study was granted an exemption from the ethical review process by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital of Leshan.

Preparation of suture tissues

The outdoor temperature on the morning of the slaughtering day was 27 °C. It took nearly three hours from the start of butchering until the time when the porcine stomachs were rinsed. The purchased porcine stomachs were uniformly loaded into a foam box with multiple ice packs, and the porcine stomachs were stored in a freezer at 4 °C after more than ten minutes of transportation. After approximately 2 h, the stomachs of the pigs were individually removed from the freezer for cutting. The temperature of the porcine stomach cutting and suturing room was set to 26 °C. To minimize the mechanical differences among the samples5, the porcine stomachs were cut in the following manner: each porcine stomach was cut along the midline of the greater curvature of the stomach, the serosal surface of the porcine stomach was kept at the top, and then, the porcine stomach was tilted in a fan shape, with the positions of the esophagus and pylorus used as anatomical references. All the porcine stomachs were kept in the same orientation (Fig. 1). Rectangular pieces of tissue were cut from the posterior wall and the anterior wall, with lengths and widths of 13 cm and 6 cm, respectively. Before the samples were cut, a ruler and marker pen were used for positioning purposes. The short side at the level of the pylorus was marked; then, the long side, 3–5 cm lateral to the midline of the lesser curvature of the stomach, was marked, and this side was essentially parallel to the midline of the lesser curvature (Fig. 2). Owing to the muscle layer thickness difference between the posterior and anterior walls of a porcine stomach, the samples cut from the posterior and anterior walls were labeled and separated. To maintain the humidity of the porcine stomachs, they were covered with wet gauze containing normal saline before and after the cutting step, and normal saline was sprayed occasionally to keep the gauze moist. When each of the 20 porcine stomachs were cut, the cut tissues were washed uniformly with running tap water, each rectangular porcine stomach was cut into two pieces at almost the midline, and the incision was used for tissue suturing.

Fig. 1.

Orientation of porcine stomach samples.

Fig. 2.

Marking and cutting of porcine stomach.

Tissue suturing

Initially, the same continuous suturing procedure was performed for both the backstitching group and the knotting group. The stitch spacing was set to 1 cm, the margin was 0.6 cm, each stitch was a full-thickness suture, and a total of 5 stitches were used. After the first suture, a standard surgical knot was used. The sutures were then partially tightened during the continuous suturing process. After the fifth stitch, the operator tightened the sutures successively. The assistant informed the operator of the randomization group assignment immediately before tightening the final throw of the continuous suture. Knotting fixation or backstitching operations were performed according to randomization, where the novel backstitching operation was used for the backstitching group and traditional surgical knot fixation was used for the knotting group.

To ensure that the baseline data for the backstitching group and the knotting group were consistent, the 20 samples derived from the posterior walls and the 20 samples acquired from the anterior walls of the porcine stomachs were each independently randomized into the backstitching group and the knotting group. Notably, numbers between 1 and 20 were generated by a random number generator and separately assigned to the anterior and posterior samples; the samples with odd numbers were added to the knotting group, and those with even numbers were included in the backstitching group. Thus, 10 samples were contained in each group: the posterior knotting group, anterior knotting group, posterior backstitching group, and anterior backstitching group. The samples derived from the anterior walls of the porcine stomachs were sutured sequentially before the samples acquired from the posterior wall were sutured.

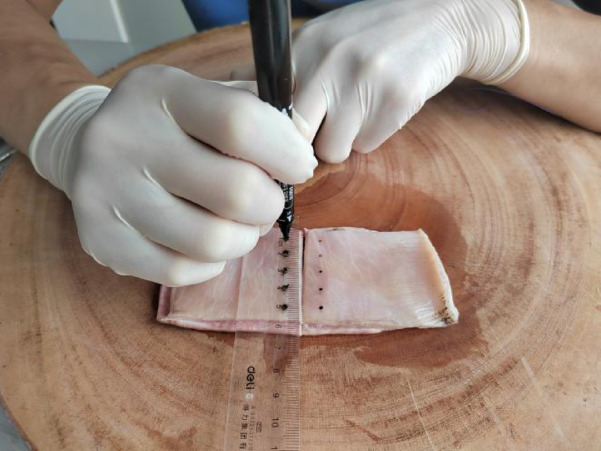

All porcine stomach suturing was completed by a doctor with more than ten years of clinical experience (Wangjing Ren). The fixation of the first thread knot at the end of the continuous sutures in the knotting group was completed by the same person in each case (Juan Liu). Appropriate strength was maintained during the operation to avoid suture wear caused by the instrument buckle. The sample cutting and suturing steps were completed on the same day. Before the start of the experiment, three porcine stomachs were purchased for repeated suturing practice and biomechanical testing. The needle entry and exit points of each stitch were marked with a plastic tool via manual punching (Fig. 3). The needle was forced into the samples at a uniform angle using a needle holder (Fig. 4), and toothed forceps were used to ensure that each stitch in the continuous suture was as close to the same as possible, thus reducing the suture variations. The specific process of the backstitching operation was as follows: after the suture of the last stitch in the continuous suture was taut, the suture at the needle exit point was fixed via laterally curved hemostatic forceps. Then, the needle was held by one hand and adjusted, and backstitching was performed for a total of 3 stitches. After each stitch, the suture was gradually tightened, and the suture at the needle exit point was fixed again with laterally curved hemostatic forceps. The first stitch of the backstitch was passed under the forward suture (Fig. 5). The second stitch of the backstitch only went through the tissue, the third stitch of the backstitch passed under the forward suture again (Fig. 6), and a tail thread with a length of approximately 1 cm remained.

Fig. 3.

Needle entry and exit points marked.

Fig. 4.

Needle insertion using a needle holder.

Fig. 5.

First backstitch.

Fig. 6.

Third backstitch.

Selection of sutures

The sutures used in this study were 2–0-gauge absorbable sutures produced by Johnson & Johnson Medical (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. (material: Polyglactin 910; model: VCP1345H; production lot number: S24040080; production date: April 16, 2024). Four samples were extracted from each suture.

Biomechanical test of suture tissues

Biomechanical testing was completed at the Product Quality Supervision and Inspection Institute of Leshan. The electronic universal testing machine was produced by Shenzhen SUNS Technology Stock Co., Ltd.(model: UTM6103; accuracy level: 0.5; maximum test force: 1 kN; power: 0.4 kW; serial number: UTM14056), the corresponding load‒displacement curve was recorded by the testing machine via Material Test 4.1, and the test was terminated when the tissue was obviously torn and the load decreased significantly (Fig. 7). The maximum load was defined as the maximum force value obtained from the load‒displacement curve, and the tensile stiffness was defined as the slope of the linearly increasing region of the load‒displacement curve. The biomechanical tests conducted for all the samples were completed by the same person (Tingcheng Qin) on the night of the suturing day, and Wangjing Ren and Juan Liu assisted with recording the biomechanical test results. The sample fixation process was as follows: a tissue holder was used to fix the upper end of the sample; then, the sample was allowed to hang naturally; and finally, the lower end of the sample was fixed with another tissue holder so that the long axis of the sample was kept vertical with respect to the horizontal position as much as possible. The distance between the two tissue holders was initially set to 5 cm (Fig. 8), and the tension test speed was uniformly set to 2 cm/min. All the samples were successfully tested, and no tissue slippage or suture breakage issues occurred during the stretching process.

Fig. 7.

Load‒displacement curve during testing.

Fig. 8.

Sample fixation for testing.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software. First, a normality test was performed on the biomechanical indicators. If the data were normally distributed, a homogeneity of variance test and an independent-samples t test were further performed on the data from the two groups. Otherwise, the Mann‒Whitney U test was performed. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was used as the criterion for assessing statistical significance.The biomechanical properties of the two suturing methods were compared by first analyzing samples from the anterior wall, followed by those from the posterior wall. Subsequently, a mixed analysis was conducted to compare the biomechanical properties between the backstitching and reverse suturing methods.

Results

There were no significant maximum load or tensile stiffness differences between the backstitching group and the knotting group (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Biomechanical test and statistical results.

| Biomechanical indicators | n | Backstitching group | Knotting group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum loada (N) | 10 | 77.05 ± 9.68 | 76.28 ± 7.92 | 0.85 |

| Tensile stiffnessa (N/mm) | 10 | 3.37 ± 0.86 | 3.39 ± 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Maximum loadb (N) | 10 | 69.15 ± 14.07 | 65.21 ± 9.68 | 0.48 |

| Tensile stiffnessb (N/mm) | 10 | 2.74 ± 0.76 | 2.80 ± 0.59 | 0.84 |

| Maximum loadc (N) | 20 | 73.10 ± 12.43 | 70.75 ± 10.31 | 0.52 |

| Tensile stiffnessc (N/mm) | 20 | 3.06 ± 0.85 | 3.10 ± 0.81 | 0.87 |

aSamples from the anterior walls of the porcine stomachs.

bSamples from the posterior walls of the porcine stomachs.

cSamples from the posterior and anterior walls of the porcine stomachs.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that the knot-free backstitching of conventional absorbable sutures provides biomechanical strength comparable to that of knotted fixation, and if the operator can hold and adjust the needle with one hand, end-suture fixation can be accomplished for conventional absorbable sutures by one person.

The results of this interesting study seem to be novel and important, although the results cannot be fully verified simply based on the widespread use of the backstitching method in the sewing process used for clothing. However, some processes in nature display similar phenomena. For example, Micromys minutus and New World monkeys have graspable tails, and when their tails are tightly wrapped around a plant or branch for a few turns, they can hang their bodies upside down in the air6,7.

To scientifically explain our results, our team conducted extensive literature reviews and interdisciplinary discussions. Unfortunately, the theoretical knowledge currently available to us is insufficient for fully and accurately explaining the results. Many questions still require further explorations, including the friction coefficient between the suture and the porcine stomach after backstitching, the applicability of the Euler‒Eytelwein formula in this complex scenario, and other related factors.

Our study has certain limitations. First, as this was a pilot experiment, the sample size was relatively small. In future studies, we will increase the sample size to further verify the findings. Second, the optimal backstitching strategy is not yet known, and scientific issues related to the backstitching operation, such as the difference between the friction coefficients of the suture and different tissues, the difference between the tissue inflammatory responses caused by different backstitching strategies, and the biomechanical differences among the different backstitching strategies, remain to be investigated. Third, fatigue testing was not performed in the biomechanical testing phase, which would have increased the level of confidence in the applicability of the approach. Finally, some differences are present between the biological properties of tissues in isolation and in vivo as well as among different species and genera, and more studies are needed to determine whether these results can be effectively applied to human clinical practice.

As this was a preliminary investigation, the feasibility of a knot-free backstitching operation was verified in this study. We hope that through interdisciplinary cooperation, other researchers will further explore this topic to promote the development of minimally invasive surgical techniques.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the team at American Journal Experts for their valuable assistance with language editing and proofreading. Their expertise has significantly improved the clarity and readability of this manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Wangjing Ren, Juan Liu and Tingcheng Qin .The first draft of the manuscript was written by Wangjing Ren and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other modes of support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

Detailed data related to this study can be requested from the corresponding author, Xiao-li Wan (leyi2025@163.com).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was granted exemption from the ethical review process by the Ethics Committee of People’s Hospital of Leshan (date: September 17, 2024).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lin, Y. et al. The efficacy and safety of knotless barbed sutures in the surgical field: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci. Rep.6, 23425 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafermann, J., Silas, U. & Saunders, R. Efficacy and safety of V-LocTM barbed sutures versus conventional suture techniques in gynecological surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet.309(4), 1249–1265 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarin, T. et al. Comparison of holding strength of suture anchors on human renal capsule. J. Endourol.24(2), 293–297 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratas, J. Villaste rõivaste õmblusvõtted keskaegsete arheoloogiliste leidude näitel/Stitches and seams of woollen garments based on medieval archaeological findings. Studia Vernacula13, 98–127 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao, J. et al. Stomach stress and strain depend on location, direction and the layered structure. J. Biomech.41(16), 3441–3447 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemelin, P. Comparative and functional myology of the prehensile tail in New World monkeys. J. Morphol.224(3), 351–368 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vega, D. A. et al. Anomalous slowdown of polymer detachment dynamics on carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett.122(21), 218003 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Detailed data related to this study can be requested from the corresponding author, Xiao-li Wan (leyi2025@163.com).