Abstract

To improve our understanding of the genetic links between strains originating from food and strains responsible for human diseases, we studied the genetic diversity and population structure of 130 epidemiologically unrelated Listeria monocytogenes strains. Strains were isolated from different sources and ecosystems in which the bacterium is commonly found. We used rRNA gene restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis with two endonucleases and random multiprimer DNA analysis with seven oligonucleotide primers to study multiple genetic features of each strain. We used three clustering methods to identify genetic links between individual strains and to determine the precise genetic structure of the population. The combined results confirmed that L. monocytogenes strains can be divided into two major phylogenetic divisions. The method used allowed us to demonstrate that the genetic structure and diversity of the two phylogenetic divisions differ. Division I is the most homogeneous and can easily be divided into subgroups with dissimilarity distances of less than 0.30. Each of these subgroups mainly, or exclusively, contains a single serotype (1/2b, 4b, 3b, or 4a). The serotype 4a lineage appears to form a branch that is highly divergent from the phylogenetic group containing serotypes 1/2b, 4b, and 3b. Division II contains strains of serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, and 3a. It exhibits more genetic diversity with no peculiar clustering. The fact that division II is more heterogeneous than division I suggests that division II evolved from a common ancestor earlier than division I. A significant association was found between division I and human strains, suggesting that strains from division I are better adapted to human hosts.

Listeria monocytogenes was first described by Murray in 1926 in guinea pigs and was recognized as a human pathogen over 70 years ago. Its clinical manifestations include meningitis, meningoencephalitis, bacteremia (27), and occasionally localized infections (16). Listeriosis is particularly dangerous for immunocompromised people and pregnant women, as fetuses may be affected by perinatal listeriosis (23). It is now known that humans become infected after ingesting contaminated food products (10). The expansion of the agro-food industry, together with the use of cold storage systems, has led to the contamination of a wide variety of foods with listeriae (10), resulting in large food-borne outbreaks. However, sporadic listeriosis remains the most frequent manifestation of the illness (2).

Although we have a thorough understanding of the virulence of the bacterium and the physiopathology of the illness, the epidemiology of human listeriosis is not fully understood (26). All 13 L. monocytogenes serotypes can cause human listeriosis, but serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b account for 95% of the cases that occur (22). The differential prevalence of these serotypes and the absence of clear links between particular forms of listeriosis and certain serotypes may be explained by studying the genetic structure of the L. monocytogenes population. Several typing methods, such as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, ribotyping, random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), have already been used to divide this species into two groups. The first contains serotypes 1/2b and 4b, and the second contains serotypes 1/2a and 1/2c (1, 6, 11, 15, 31). However, the precise genetic structure of each group has only been determined in part. In addition, some groups have reported the existence of a third evolutionary lineage (20) containing strains from serotype 4a, which are thought to be less virulent (32).

We studied the genetic diversity and population structure of L. monocytogenes species by using a collection of strains isolated from various ecological sources. We developed a multiprimer RAPD method with seven primers as a phylogenetic tool. The multiprimer RAPD data were analyzed by each of three clustering methods alone and in combination with rRNA gene (rDNA) restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) data. Our results confirmed that L. monocytogenes is composed of two distant phylogenetic divisions of strains and indicated that the third division is, in fact, a branch of the first division. Moreover, our genetic analysis demonstrated for the first time that the genetic characteristics of the two divisions differ in terms of heterogeneity and the link between individuals, suggesting differences in the evolution of the two populations of strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

We collected 130 epidemiologically unrelated strains of L. monocytogenes strains from the various ecosystems, including the natural environment and farms (n = 19), animals with clinical symptoms (n = 31), food products (n = 30), adult human infections (n = 30), and perinatal infections (n = 20). Seven of the adult human strains represented seven different epidemics (Angers [1976], Carliste [1981], Halifax [1981], Boston [1983], California [1985], Switzerland [1987], and Val d'Oise [1988]). All of the epidemic strains belonged to serotype 4b, except for the strains involved in the Carliste (serotype 1/2a) and Val d'Oise (serotype 1/2b) epidemics. All of the strains were isolated between 1976 and 1999 in France, England, Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, the United States, and Canada. The epidemiological, geographical, and temporal origins of the strains are indicated in Table 1. All of the isolates were biochemically characterized by conventional identification methods (3).

TABLE 1.

Epidemiological, geographical, and temporal origins of the 130 epidemiologically unrelated strains of L. monocytogenes used in this study

| Straina | Serotype | Origin codeb | Specific source | Geographical origin | Yr of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | 1/2a | A | NKc | France | 1989 |

| 57 | 1/2a | A | Sausage | France | 1990 |

| 59 | 1/2a | A | Cheese | France | 1990 |

| 64 | 1/2a | A | Cheese | France | 1992 |

| 65 | 1/2a | A | Cold cooked meats | France | 1993 |

| 67 | 1/2a | A | Chicken | France | 1993 |

| 68 | 1/2a | A | Cold cooked meats | Spain | 1994 |

| 70 | 1/2a | A | NK | France | 1994 |

| 71 | 1/2a | A | Smoked salmon | Spain | 1996 |

| 72 | 1/2a | A | Meat | France | 1996 |

| 76 | 1/2a | A | Smoked salmon | NK | 1997 |

| 80 | 1/2a | A | Cold cooked meats | NK | 1999 |

| 112 | 1/2a | E | Dung | France | NK |

| 115 | 1/2a | E | NK | France | 1989 |

| 116 | 1/2a | E | Silage | France | 1989 |

| 118 | 1/2a | E | Water (pond) | France | 1991 |

| 122 | 1/2a | E | NK | France | 1993 |

| 124 | 1/2a | E | Silage | NK | 1999 |

| 125 | 1/2a | E | Water | France | 1999 |

| 127 | 1/2a | E | Water | Switzerland | NK |

| 23 | 1/2a | F | Skin | France | 1987 |

| 28 | 1/2a | F | Placenta | France | 1992 |

| 40 | 1/2a | F | Placenta | France | 1988 |

| 49 | 1/2a | F | Umbilical cord | France | 1999 |

| 50 | 1/2a | F | Cerebrospinal fluid | France | 1996 |

| 3 | 1/2a | H | NK | Englandd | 1981 |

| 14 | 1/2a | H | Blood culture | Belgium | 1988 |

| 24 | 1/2a | H | Blood culture | France | 1990 |

| 27 | 1/2a | H | Blood culture | Cayenna | 1990 |

| 32 | 1/2a | H | Cerebrospinal fluid | France | 1993 |

| 45 | 1/2a | H | Cerebrospinal fluid | France | 1999 |

| 46 | 1/2a | H | NK | Switzerland | 1998 |

| 81 | 1/2a | N | Spinal cord (lamb) | France | 1986 |

| 85 | 1/2a | N | Brain (lamb) | France | 1988 |

| 88 | 1/2a | N | Placenta (cow) | France | 1988 |

| 89 | 1/2a | N | Placenta (cow) | France | 1989 |

| 90 | 1/2a | N | Brain (sheep) | France | 1989 |

| 93 | 1/2a | N | Placenta (sheep) | France | 1989 |

| 94 | 1/2a | N | Brain (lamb) | France | 1989 |

| 95 | 1/2a | N | Runt | France | 1989 |

| 96 | 1/2a | N | Runt (goat) | France | NK |

| 97 | 1/2a | N | Liver (sheep) | France | 1990 |

| 103 | 1/2a | N | Cow | France | 1992 |

| 105 | 1/2a | N | NK | France | 1992 |

| 107 | 1/2a | N | Fetus (goat) | France | 1993 |

| 108 | 1/2a | N | NK | England | 1993 |

| 110 | 1/2a | N | Udder | France | 1990 |

| 111 | 1/2a | N | Eye (cow) | France | NK |

| 52 | 1/2b | A | NK | France | 1988 |

| 53 | 1/2b | A | Salad | France | 1988 |

| 58 | 1/2b | A | MilK | France | 1990 |

| 62 | 1/2b | A | Sauerkraut | France | 1992 |

| 74 | 1/2b | A | Meat | Spain | 1997 |

| 78 | 1/2b | A | Chicken | France | 1999 |

| 113 | 1/2b | E | Silage | France | NK |

| 114 | 1/2b | E | Silage | France | NK |

| 119 | 1/2b | E | Silage | France | 1991 |

| 130 | 1/2b | E | Water (brook) | Switzerland | 1997 |

| 9 | 1/2b | F | Blood culture | Germany | 1986 |

| 10 | 1/2b | F | Fetus | France | 1986 |

| 15 | 1/2b | F | Placenta | France | 1986 |

| 20 | 1/2b | F | Cerebrospinal fluid | The Netherlands | 1990 |

| 18 | 1/2b | H | Blood culture | Franced | 1988 |

| 36 | 1/2b | H | Blood culture | Spain | 1995 |

| 39 | 1/2b | H | NK | France | 1997 |

| 47 | 1/2b | H | Wound | Switzerland | 1998 |

| 91 | 1/2b | N | Brain (lamb) | France | 1989 |

| 101 | 1/2b | N | Lymph nodes | France | 1991 |

| 51 | 1/2c | A | Cheese | France | 1988 |

| 69 | 1/2c | A | Meat | Spain | 1994 |

| 79 | 1/2c | A | Meat | France | 1999 |

| 123 | 1/2c | E | NK | France | 1995 |

| 26 | 1/2c | H | Blood culture | France | 1990 |

| 42 | 1/2c | H | Blood culture | England | 1999 |

| 60 | 3a | A | Turkey | France | 1991 |

| 129 | 3b | E | NK | Switzerland | 1997 |

| 22 | 3b | H | Blood culture | France | 1990 |

| 35 | 3b | H | Blood culture | Spain | 1995 |

| 41 | 3b | H | Cerebrospinal fluid | Italy | 1999 |

| 87 | 3b | N | Cerebrospinal fluid (goat) | France | 1988 |

| 19 | 4a | F | Blood culture | The Netherlands | 1990 |

| 99 | 4a | N | Brain (goat) | France | 1991 |

| 54 | 4b | A | Potatoes | France | 1988 |

| 55 | 4b | A | Cheese | France | 1988 |

| 61 | 4b | A | Milk | Belgium | 1991 |

| 63 | 4b | A | Cold cooked meats | France | 1992 |

| 66 | 4b | A | Cheese | France | 1993 |

| 73 | 4b | A | Chicken | Spain | 1997 |

| 75 | 4b | A | Smoked salmon | France | 1997 |

| 77 | 4b | A | NK | Italie | 1999 |

| 117 | 4b | E | NK | France | 1989 |

| 120 | 4b | E | Silage | France | 1991 |

| 121 | 4b | E | Silage | France | 1991 |

| 126 | 4b | E | Dung | France | NK |

| 128 | 4b | E | NK | Switzerland | NK |

| 5 | 4b | F | Blood culture | Switzerland | 1985 |

| 8 | 4b | F | Cerebrospinal fluid | Germany | 1986 |

| 13 | 4b | F | Placenta | France | 1988 |

| 17 | 4b | F | Blood culture | England | 1988 |

| 21 | 4b | F | Cerebrospinal fluid | The Netherlands | 1990 |

| 29 | 4b | F | Fetus | France | 1990 |

| 30 | 4b | F | Placenta | France | 1992 |

| 33 | 4b | F | NK | France | 1997 |

| 44 | 4b | F | Skin | France | 1999 |

| 48 | 4b | F | Amniotic fluid | Switzerland | 1998 |

| 1 | 4b | H | NK | Franced | 1976 |

| 2 | 4b | H | NK | Canadad | 1981 |

| 4 | 4b | H | NK | United Statesd | 1983 |

| 6 | 4b | H | NK | United Statesd | 1985 |

| 7 | 4b | H | Blood culture | France | 1986 |

| 11 | 4b | H | NK | Switzerlandd | 1987 |

| 12 | 4b | H | Cerebrospinal fluid | France | 1988 |

| 16 | 4b | H | Blood culture | France | 1982 |

| 25 | 4b | H | Cerebrospinal fluid | France | 1990 |

| 31 | 4b | H | Ascites | France | 1993 |

| 34 | 4b | H | Blood culture | France | 1994 |

| 37 | 4b | H | Blood culture | Spain | 1996 |

| 38 | 4b | H | Septic arthritis | France | 1996 |

| 43 | 4b | H | Cerebrospinal fluid | France | 1999 |

| 82 | 4b | N | Brain | France | 1987 |

| 83 | 4b | N | Placenta | France | 1988 |

| 84 | 4b | N | Brain (cow) | NK | 1988 |

| 86 | 4b | N | Cerebrospinal fluid (lamb) | France | 1988 |

| 92 | 4b | N | Brain (ewe) | France | 1989 |

| 98 | 4b | N | Brain (ewe) | France | 1990 |

| 100 | 4b | N | Brain (cow) | France | 1991 |

| 102 | 4b | N | Brain (cow) | France | 1992 |

| 104 | 4b | N | Brain (goat) | France | 1992 |

| 106 | 4b | N | Ewe | France | 1993 |

| 109 | 4b | N | Feces | France | 1994 |

The strains are numbered as in Fig. 1, 2, and 3. Strains were isolated from various ecosystems (the environment, animals, food products, adult human infections, and perinatal infections). All of the strains were isolated between 1976 and 1999 in France, England, Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, the United States, and Canada.

Origin codes: A, food products; E, environment; F, perinatal infections; H, adult human infections; N, animals.

NK, not known.

Strain representing one of the seven different epidemics (Angers [1976], Carliste [1981], Halifax [1981], Boston [1983], California [1985], Switzerland [1987], and Val d'Oise [1988]).

Serotyping.

Serotyping was carried out with antisera OI, OI-II, OIV, OV-VI, OVI, OVII, OVIII, and OIX for somatic antigens and with antisera H-A, H-AB, H-C, and H-D for flagellar antigens in accordance with the manufacturer's (Mast Diagnostic, Amiens, France) instructions.

Extraction of genomic DNA.

Each strain was subcultured on Trypticase soy agar containing 5% horse blood. The culture was harvested in 1 ml of buffer (1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 0.5× Triton). Twenty microliters of 10% lysozyme (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and 20 μl of 2% proteinase K (Sigma) were added, and the mixture was incubated for 60 min at 37°C and then for 60 min at 60°C before undergoing two phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) (Sigma) extractions. After centrifugation, DNA was precipitated by the addition of 10% NaCl in absolute ethanol for 10 min at −80°C; the sample was then recentrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 1× Tris-EDTA.

Generation of rDNA RFLP patterns.

DNA (6 μg) was digested with EcoRI and PvuII (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting fragments were separated by horizontal electrophoresis for 16 h at a constant voltage (50 V) in a 1% agarose gel made in TBE buffer (8.9 mM Tris, 8.9 mM borate, 0.25 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). DNA from the type strain Citrobacter koseri CIP 105177 was digested with MluI and included in each gel as a molecular weight marker. DNA fragments were vacuum transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche) as recommended by the manufacturer (Vacuoblot; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Probes were prepared by randomly priming 250 ng of Escherichia coli 16S and 23S rRNA (Boehringer) with a mixture of hexanucleotides (Pharmacia), cloned Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL), and digoxigenin (Boehringer). The samples were hybridized with the probes overnight at 65°C and then washed in sodium citrate buffers as previously described (8). The hybridized probe was visualized by immunodetection with anti-digoxigenin Fab fragments conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. The light emitted by the chemiluminescent substrate CSPD (Boehringer) was recorded on hyperfilm MP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

RAPD fingerprinting.

Seven previously described primers were chosen (Table 2). The PCR mixture consisted of buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2 [pH 8.3]), the four deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Boehringer) at 100 μM each, 0.4 μM primer, 25 ng of DNA, and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) in a total volume of 25 μl. Each sample was subjected to one denaturation cycle (4 min at 94°C, 1 min at 36°C, and 2 min at 72°C) in a DNA Thermal Cycler 9600 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). This was followed by 35 cycles as follows: denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 36°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min (for the last cycle, extension was done at 72°C for 10 min). The resulting amplified products were separated in a 1% agarose gel in TBE buffer for 3 h at a constant voltage of 100 V. The amplified products were detected by UV transillumination with ethidium bromide staining. A 1-kb ladder (Gibco BRL) was used as a molecular size standard.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of the seven primers used for multiprimer RAPD

Computer phylogenetic analysis.

Photographs of gels (RAPD) and of autoradiographs (rDNA RFLP) were digitalized with a video camera connected to a microcomputer (Bio-Profil; Vilber-Loumat, Marne la Vallée, France). The Taxotron package (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), including RestrictoScan, RestrictoTyper, Adanson, and Dendrograph, was used for numerical analysis. The molecular size of each fragment was calculated from the distance migrated by use of the global reciprocal method of Schaffer and Sederoff. The distance matrix was used to calculate the complement of the Dice coefficient for each pair of strains. For a given strain, the RAPD type was defined as the combination of patterns obtained with the seven primers. Relationships between types were calculated by use of the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA), the complete-linkage method, and the neighbor-joining method (25, 28) and were represented as a dendrogram.

RESULTS

Serotypes.

The serotype distribution of the 130 L. monocytogenes strains was as follows: 1/2a, 48 strains; 1/2b, 20 strains; 1/2c, 6 strains; 3a, 1 strain; 3b, 5 strains; 4a, 2 strains; 4b, 48 strains.

Genetic structure of the L. monocytogenes population as established by rDNA RFLP analysis.

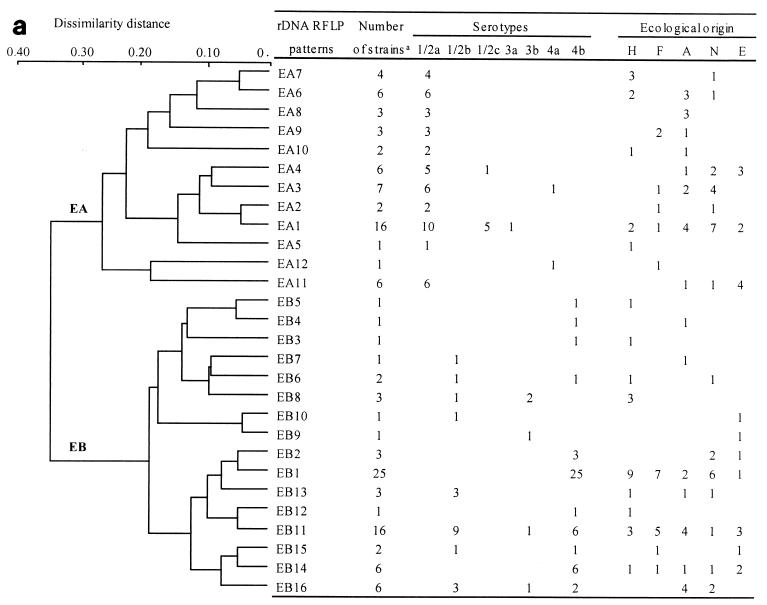

Whatever the endonuclease used, the rDNA RFLP analysis identified two phylogenetic divisions: EA and EB with EcoRI and PA and PB with PvuII (Fig. 1). EA contained 12 patterns, and EB contained 16 patterns (Fig. 1a). PA contained 18 patterns, and PB contained 14 patterns (Fig. 1b). EA and PA contained the same strains, belonging to serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, 3a, and 4a. Similarly, EB and PB regrouped the same strains, belonging to serotypes 1/2b, 4b, and 3b. rDNA RFLP analysis did not reveal any peculiar links between the various serotypes obtained by clustering.

FIG. 1.

Dendrograms showing the genetic relationships among the 28 rDNA RFLP patterns obtained for the 130 L. monocytogenes strains studied with EcoRI (a) and the genetic relationships among the 32 rDNA RFLP patterns obtained with PvuII (b). The dendrograms were constructed by computer analysis with the Taxotron package by using the UPGMA. On the right is the correlation between rDNA RFLP patterns and the serotypes and origins of the strains.

Several rDNA RFLP patterns contained a large number of strains (Fig. 1). The 30 adult clinical isolates were distributed into 14 patterns, but 18 strains (60%) grouped into 4 of the EcoRI patterns: EB1, EB8, EB11, and EA7. The 20 strains from perinatal infections were distributed into nine patterns, but 12 (60%) grouped into EcoRI patterns EB1 and EB11. Among the patterns obtained with PvuII, 16 of the 30 adult clinical strains (53%) were distributed into two patterns: PB1 and PA13. Similarly, 13 (65%) of the 20 perinatal infection strains were clustered into patterns PB1 and PB5 (Fig. 1).

Genetic structure of L. monocytogenes population as established by RAPD analysis.

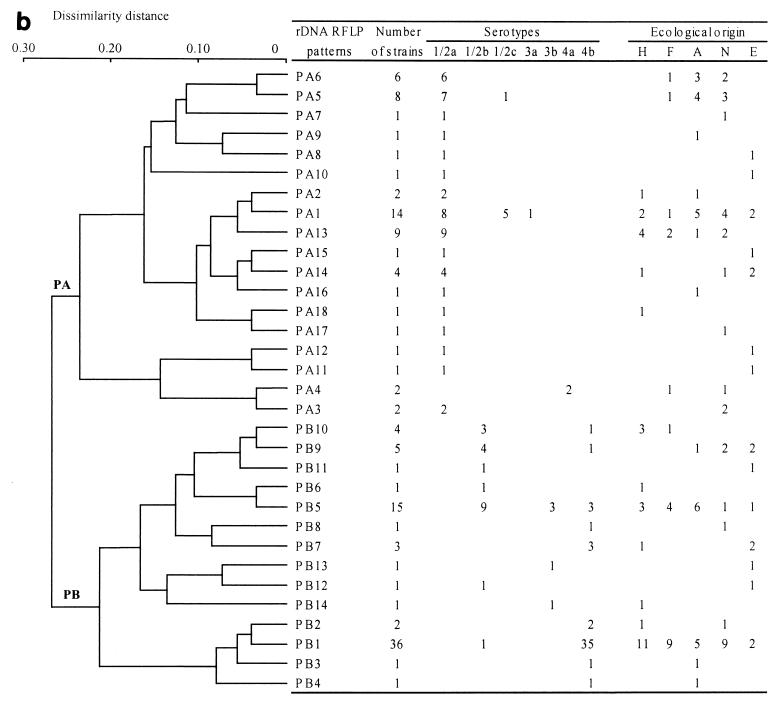

The size and number of bands obtained with each of the seven RAPD primers are listed in Table 2. The genetic relationships among the 130 L. monocytogenes strains are represented in a dendrogram constructed by the UPGMA and confirmed by the neighbor-joining and complete-linkage methods (Fig. 2). All three methods distinguished two divisions at a large dissimilarity distance (0.60). The first division, named RB, contained all of the strains from serotypes 1/2b, 4b, 3b, and 4a. The second division, named RA, contained strains of serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, and 3a. The two RAPD divisions contained the same strains as the rDNA RFLP divisions, except for the strains of serotype 4a. The RAPD method placed these strains in division RB with strains of serotypes 1/2b, 4b, and 3b (Fig. 2), whereas the rDNA RFLP analysis placed them in divisions EA and PA with strains of serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, and 3a (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram showing the genetic relationships among the 130 RAPD types obtained with the seven primers (Table 1) for 130 L. monocytogenes strains. The RAPD type is defined as the combinationof patterns obtained with the seven primers for a given strain. The dendrogram was constructed by computer analysis with the Taxotron package by using the UPGMA. The symbols ∗ and o indicate branches that were also found by the neighbor-joining and complete-linkage methods, respectively. Division RB is divided into 10 subclusters: RB1 to RB10. The serotypes and origins of the strains are indicated on the right (see also Table 1). Origin codes: A, food products; E, environment; F, perinatal infections; H, adult human infections; N, animals; #, epidemics.

In division RB, at a dissimilarity distance of 0.22, a certain degree of clustering was observed according to the serotype distribution of the strains. This clustering distinguished 10 different subgroups: RB1 to RB10. Among the 48 strains belonging to serotype 4b, 15 were located in subgroup RB2, 11 were in RB5, 9 were in RB6, 3 were in RB8, and 2 were in RB10. The remaining nine strains were randomly distributed within division RB. Among the 20 serotype 1/2b strains, 8 were in subgroup RB3, 4 were in RB8, 2 were in RB7, and the other 8 were randomly distributed within division RB. The five serotype 3b strains were randomly distributed within division RB. The two serotype 4a strains constituted a peculiar subgroup that diverged at a dissimilarity distance of 0.50 from the other division RB strains.

Most of the strains and RAPD types in the RA division diverged at a dissimilarity distance of over 0.30 and were not clustered according to serotype (1/2a versus 1/2c) (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic analysis by combined rDNA RFLP and multiprimer RAPD analyses.

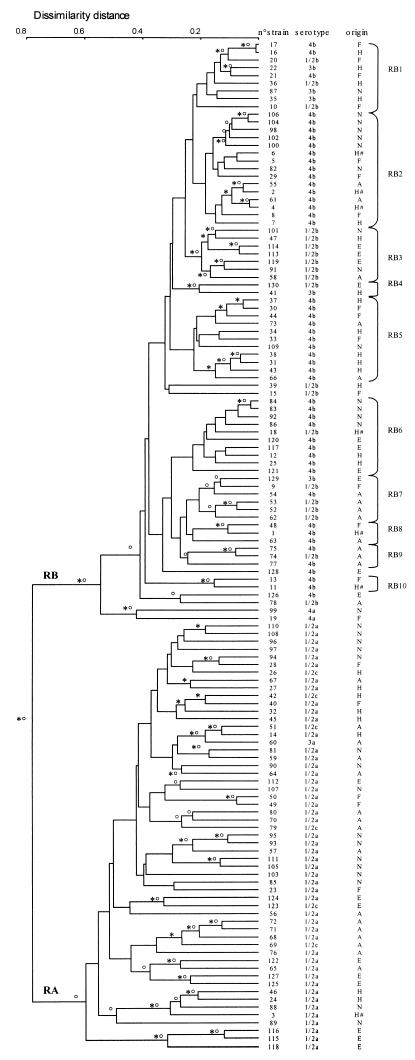

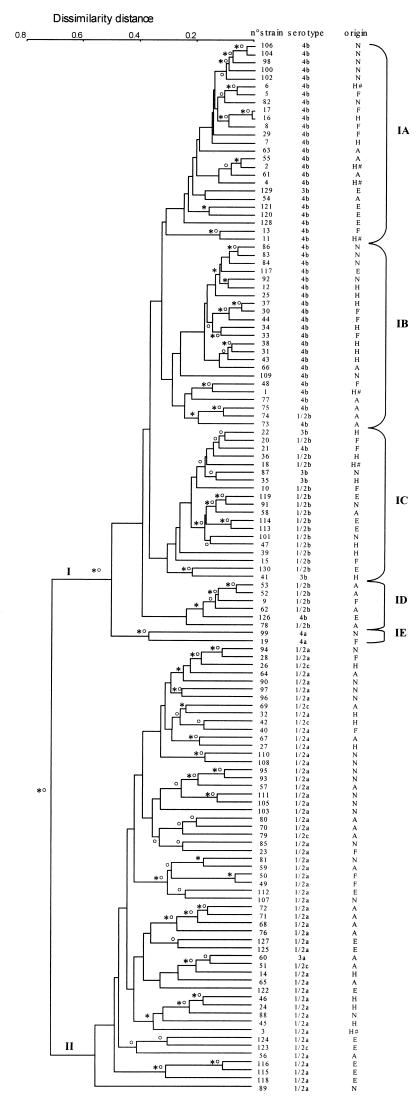

The combined data from the multiprimer RAPD analysis and rDNA RFLP confirmed that L. monocytogenes is composed of two major phylogenetic divisions (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, combining the data from the two methods significantly improved clustering according to serotypes in phylogenetic division I. Indeed, four homogeneous subgroups were distinguished at a dissimilarity distance of 0.30 in this division. The first (IA) and second (IB) contained 24 and 22 of the 48 serotype 4b strains, respectively, and the third (IC) and fourth (ID) contained 14 and 5 of the 20 serotype 1/2b strains, respectively. The five serotype 3b strains were grouped within subgroups IA (one strain) and IC (four strains) (Table 3). A fifth subgroup (IE) contained the two serotype 4a strains but at a greater dissimilarity distance (0.40).

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram showing the genetic relationships between the combination of the RAPD types obtained with the seven primers and the rDNA RFLP patterns obtained with EcoRI and PvuII for 130 L. monocytogenes strains. The dendrogram was constructed by computer analysis with the Taxotron package by using the UPGMA. The symbols ∗ and o indicate branches that were also found by the neighbor-joining and complete-linkage methods, respectively. Phylogenetic division I is divided into five subgroups, named IA to IE. The serotypes and ecological origins of the strains are indicated on the right (see also Table 1). Origin codes: A, food products; E, environment; F, perinatal infections; H, adult human infections; N, animals; #, epidemics.

TABLE 3.

Division of the L. monocytogenes population into two phylogenetic divisions on the basis of the ecological origins of the strainsa

| Origin | No. of strains in:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic division Ib

|

Phylogenetic division II | ||||||

| Total | IA | IB | IC | ID | IE | ||

| Environment | 10 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 9 | |

| Animal samples | 15 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 16 | |

| Food products | 14 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 16 | |

| Adult human infections | 21 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 9 | ||

| Perinatal infections | 15 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

The strains were divided by combining the data obtained by multiprimer DNA analysis and rDNA RFLP analysis.

Phylogenetic division I is subdivided into five subgroups.

In phylogenetic division II, the combined data did not identify genetic subgroups within serotype 1/2a (48 strains) or 1/2c (6 strains). In addition, the resulting dendrogram was more highly branched than that of division I, the branches were longer than those in division I, and the dissimilarity distance between most of the strains was over 0.35, which is consistent with the heterogeneous structure of phylogenetic division II (Fig. 3).

The strains from the environment, pathological animal samples, and food products were distributed randomly among the two phylogenetic divisions and subgroups. Conversely, 36 of the 50 human strains (adult and perinatal infections) were located in division I (Fig. 3). We compared the distribution of the strains isolated from the environment, animals, and food products with the distribution of the strains isolated from humans (Table 3) and found significantly more human isolates in division I (P = 0.015; χ2 test).

DISCUSSION

Even though L. monocytogenes causes relatively few cases of human disease, it is still a major problem for public health because it is widespread and present in many food products. A better understanding of the ecological epidemiology and particularly of the genetic structure of listeriae should help us to understand the origin of human listeriosis. Thus, we used multiprimer RAPD and rDNA RFLP analyses to determine multiple genetic features of 130 L. monocytogenes strains isolated from humans, animals, food products, and the environment to define the genetic diversity and structure of the two phylogenetic divisions that compose the L. monocytogenes species more accurately.

rDNA RFLP analysis, which explores stable regions of the genome, has already been used to determine the genetic diversity of several bacterial species (7, 18). RAPD fingerprinting is also an interesting method for assessing the genetic structure of a microbial population, and it is particularly well suited for phylogenetic analysis because when several primers are used, this method explores the genome thoroughly (8, 24, 29, 30). The combination of these two molecular methods is an original and powerful tool for identifying genetic events that have occurred in bacterial genomes. The multiple genetic traits identified by these methods must be analyzed by several clustering methods to appreciate the strength of the genetic links between individuals. Indeed, multiple clustering methods showed that the branch topologies were similar, indicating that the designated phylogeny is correct (12, 24). We used combined data from multiprimer DNA analysis and rDNA RFLP analysis to determine the genetic links between strains by three clustering methods (the UPGMA, the neighbor-joining method, and the complete-linkage method). Thus, we believe that the genetic structure obtained for our L. monocytogenes population is correct.

Our procedure confirmed that the L. monocytogenes population is divided into two clearly distinct phylogenetic divisions, as previously demonstrated by other molecular methods (6, 7, 11, 17, 19), including the most recently developed AFLP method (1). One division is composed of strains belonging to serotypes 1/2b, 4b, and 3b, and the other contains strains of serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, and 3a. All of these concordant results seem to confirm that the species L. monocytogenes is indeed composed of two phylogenetic divisions. However, one multilocus enzyme electrophoresis study included serotype 4a strains in the same division as strains from serotypes 1/2b, 4b, and 3b (17), whereas an AFLP study included them in the same division as strains from serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, and 3a (1). Partial sequencing of the listeriolysin gene has suggested the existence of a third evolutionary lineage containing strains of rare serotype 4a (20). A combination of ribotyping and allelic analysis of the three virulence genes also suggested the existence of this lineage (32). Our data also showed that the position of the branch regrouping the strains from serotype 4a was uncertain. rDNA RFLP analysis found that these strains belonged to one phylogenetic division, and RAPD analysis found that they belonged to the other division. The combination of the two methods clustered the strains from serotype 4a as a lineage that diverged precociously from phylogenetic division I (Fig. 3). The relatively large dissimilarity distance (0.50) between the serotype 4a strains and the four other subclusters in phylogenetic division I may explain why other molecular methods found that this subgroup was a third phylogenetic lineage.

In this study, the large exploration of the bacterial genome and the use of several clustering methods further elucidated the genetic structure of the two phylogenetic divisions that compose the species L. monocytogenes. The two divisions were shown to be genetically different. Division I is homogeneous. This is the case for the population of serotype 4b strains (11) and for serotype 1/2b strains. Indeed, most of the strains clustered at a small dissimilarity distance (less than 0.30) and strong subclustering was obtained, identifying five subgroups (IA, IB, IC, ID, and IE) (Fig. 3), each mainly, or exclusively, marked by a specific phenotypic expression, i.e., the nature of the somatic and flagellar antigen factors characterized by serotyping. Conversely, phylogenetic division II appears to be more heterogeneous, with the dissimilarity distance between strains often exceeding 0.35. There was no obvious subclustering, and serotyping did not identify any genetic subgroups. These results indicate a lower degree of linkage between individuals in phylogenetic division II. The refined genetic structure obtained by the combined used of ribotyping and random multiprimer analysis, which considered each genetic division as a whole, except for the serotype 4a strains from division I, is in agreement with that obtained by Aarts et al. (1).

The greater genetic homogeneity in division I suggests that division I evolved from a common ancestor after division II (21). DNA sequencing of multiple genes may help to document this point further (14). The association between human strains and phylogenetic division I implies that strains from division I may be better adapted to the human host than are strains from division II.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Aguado (Pamplona, Spain), J. Bille (Lausanne, Switzerland), A. Brisabois (Paris, France), B. Facinelli (Ancona, Italy), P. Dufour (Lyon, France), F. Laurent (Lyon, France), C. Martin (Limoges, France), C. Ramanantsoa (Le Mans, France), A. Reynaud (Lempdes, France), O. Traore (Clermont-Ferrand, France), and J. M. Wautelet (Ottignies, Belgium) for providing some of the strains used in this study. We also thank S. Brun for technical assistance with serotyping. We are indebted to P. Martin and C. Jacquet (Centre National de Référence des Listeria, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for helping us to determine the serotypes of some fastidious strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarts, H. J., L. E. Hakemulder, and A. M. A. Van Hoef. 1999. Genomic typing of Listeria monocytogenes strains by automated laser fluorescence analysis of amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprint patterns. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 49:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2001. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 2000. JAMA 285:285-286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audurier, A., and C. Martin. 1989. Phage typing of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 8:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black, S. F., D. I. Gray, D. R. Fenlon, and R. G. Kroll. 1995. Rapid RAPD analysis for distinguishing Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes serotypes using a capillary air thermal cycler. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 20:188-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerlin, P., E. Bannerman, F. Ischer, J. Rocourt, and J. Bille. 1995. Typing Listeria monocytogenes: a comparison of random amplification of polymorphic DNA with 5 other methods. Res. Microbiol. 146:35-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosch, R., J. Chen, and J. B. Luchansky. 1994. Pulsed-field fingerprinting of listeriae: identification of genomic divisions for Listeria monocytogenes and their correlation with serovar. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2584-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce, J. L., R. J. Hubner, E. M. Cole, C. I. McDowell, and J. A. Webster. 1995. Sets of EcoRI fragments containing ribosomal RNA sequences are conserved among different strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5229-5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatellier, S., H. Huet, S. Kenzi, A. Rosenau, P. Geslin, and R. Quentin. 1996. Genetic diversity of rRNA operons of unrelated Streptococcus agalactiae strains isolated from cerebrospinal fluid of neonates suffering from meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2741-2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Destro, M. T., M. F. Leitao, and J. M. Farber. 1996. Use of molecular typing methods to trace the dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes in a shrimp processing plant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:705-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber, J. M., and P. I. Peterkin. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55:476-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves, L. M., B. Swaminathan, M. H. Reeves, S. B. Hunter, R. E. Weaver, B. D. Plikaytis, and A. Schuchat. 1994. Comparison of ribotyping and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2936-2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, J. 1993. Improving the accuracy of phylogenetic estimation by combining different methods. Syst. Biol. 43:331-340. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence, L. M., J. Harvey, and A. Gilmour. 1993. Development of a random amplification of polymorphic DNA typing method for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3117-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lecointre, G., L. Rachdi, P. Darlu, and E. Denamur. 1998. Escherichia coli molecular phylogeny using the incongruence length difference test. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15:1685-1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazurier, S. I., A. Audurier, N. Marquet-van der Mee, S. Notermans, and K. Wernars. 1993. A comparative study of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis and conventional phage typing for epidemiological studies of Listeria monocytogenes isolates. Res. Microbiol. 143:507-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mereghetti, L., N. Marquet-van der Mee, P. Laudat, J. Loulergue, J. Jeannou, and A. Audurier. 1998. Listeria monocytogenes septic arthritis. A case report and review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 4:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piffaretti, J. C., H. Kressebuch, M. Aeschbacher, J. Bille, E. Bannerman, J. M. Musser, R. K. Selander, and J. Rocourt. 1989. Genetic characterization of clones of the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes causing epidemic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3818-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pignato, S., G. M. Giammanco, F. Grimont, P. A. Grimont, and G. Giammanco. 1999. Molecular characterization of the genera Proteus, Morganella, and Providencia by ribotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2840-2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen, O. F., T. Beck, J. E. Olsen, L. Dons, and L. Rossen. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes isolates can be classified into two major types according to the sequence of the listeriolysin gene. Infect. Immun. 59:3945-3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen, O. F., P. Skouboe, L. Dons, L. Rossen, and J. E. Olsen. 1995. Listeria monocytogenes exists in at least three evolutionary lines: evidence from flagellin, invasive associated protein and listeriolysin O genes. Microbiology 141:2053-2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridley, M. 1996. Evolution. Blackwell Science Inc., Cambridge, Mass.

- 22.Rocourt, J., and P. Cossart. 1997. Listeria monocytogenes, p. 337-352. In M. P. Doyle, L. R. Beuchat, and T. J. Montville (ed.), Food microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Rocourt, J., C. Jacquet, and A. Reilly. 2000. Epidemiology of human listeriosis and seafoods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 62:197-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruimy, R., E. Genauzeau, C. Barnabé, A. Beaulieu, M. Tibayrenc, and A. Andremont. 2001. Genetic diversity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from ventilated patients with nosocomial pneumonia, cancer patients with bacteremia, and environmental water. Infect. Immun. 69:584-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlech, W. F., 3rd. 2000. Foodborne listeriosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:770-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuchat, A., B. Swaminathan, and C. V. Broome. 1991. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:169-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sneath, P. H. A., and R. R. Sokal. 1973. Numerical taxonomy. The principle and practice of numerical classification. W.H. Freeman & Co., San Francisco, Calif.

- 29.Tibayrenc, M., K. Neubauer, C. Barnabe, F. Guerrini, D. Skarecky, and F. J. Ayala. 1993. Genetic characterization of six parasitic protozoa: parity between random-primer DNA typing and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:1335-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, G., T. S. Whittam, C. M. Berg, and D. E. Berg. 1993. RAPD (arbitrary primer) PCR is more sensitive than multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for distinguishing related bacterial strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:5930-5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wernars, K., P. Boerlin, A. Audurier, E. G. Russell, G. D. Curtis, L. Herman, and N. van der Mee-Marquet. 1996. The W. H. O. multicenter study on Listeria monocytogenes subtyping: random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 32:325-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiedmann, M., J. L. Bruce, C. Keating, A. E. Johnson, P. L. McDonough, and C. A. Batt. 1997. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect. Immun. 65:2707-2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]