Abstract

Cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of mortality, highlighting the critical need for novel therapeutic strategies. RNA-based therapeutics, including siRNA and mRNA, offer promising approaches for cardiac diseases, yet their clinical application is limited by low heart specificity and suboptimal delivery methods. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are widely used for RNA delivery but often accumulate in non-cardiac tissues, reducing their effectiveness. To address this, an extracellular matrix (ECM)-LNP composite is developed for targeted RNA delivery to the myocardium. The LNPs are conjugated to the ECM scaffold to enhance RNA retention. In vivo experiments demonstrate effective mRNA delivery and expression within the heart, with preferential targeting towards immune cells. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a key regulator of cell proliferation and inflammation, is found to affect macrophage polarization in this study. The therapeutic potential of EGFR siRNA delivered via ECM-LNP composite is further explored in a mouse model of myocardial infarction (MI). Results indicate that ECM-siEGFR@LNP reduces cardiac fibrosis and promotes M2 macrophage polarization. This effect is associated with down-regulation of the EGFR-AKT signaling pathway. In conclusion, this study presents an injectable platform for heart-specific RNA delivery and sheds light on the role of EGFR signaling in the cardiac repair process.

Keywords: Localized delivery, siRNA therapy, Extracellular matrix-lipid nanoparticle composite, Myocardial infarction, Epidermal growth factor receptor

Graphical abstract

An extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogel–lipid nanoparticle (LNP) composite was developed in this study. LNPs were covalently conjugated to the ECM scaffold. The ECM-LNP composite enables precise and sustained delivery of RNA drugs into the heart after intramyocardial injection. Delivering Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) siRNA into the heart using ECM-LNP composite promoted heart repair after myocardial infarction in mice. At the cellular level, ECM-LNP-siEGFR facilitated macrophage M2 polarization during the inflammatory stage. Transcriptome and histological analyses indicated that EGFR siRNA decreased AKT phosphorylation in macrophages after ischemic heart injury.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally, with MI being among the most prevalent [1]. During an acute MI, the occlusion of a coronary artery leads to extensive cardiomyocyte necrosis and apoptosis. Consequently, the loss of cardiomyocytes in the infarcted area is permanent, with fibrotic tissue forming in their place. Currently, there are no approved clinical therapies capable of preventing this pathological fibrosis or reversing adverse cardiac remodeling. In severe cases, MI can progress to heart failure, a condition for which heart transplantation remains the only curative option [2]. Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches are urgently needed to enhance cardiac repair following MI.

Aberrant EGFR signaling has been observed in infarcted hearts [3]. In addition, inhibiting EGFR signaling reduces fibrosis in models of renal, hepatic, and pulmonary injury [[4], [5], [6]]. EGFR suppression also facilitates the phenotypic transition of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 state to the pro-reparative M2 state [7,8]. These findings suggest that EGFR is a potential therapeutic target for tissue injury. However, despite the evaluation of EGFR-targeting siRNA and chemical inhibitors in various disease models, their therapeutic potential in MI has not yet been investigated.

RNA-based medicines represent a promising new class of therapeutics for cardiovascular diseases, with many siRNA and mRNA drugs under investigation for MI. However, less than 10 RNA therapeutics for cardiomyopathy are currently in clinical trials [9]. A major limitation of RNA therapy for cardiac applications is the rapid dispersion of RNA@LNP from the injection site due to diffusion and circulation, which significantly shortens the therapeutic window [[10], [11], [12]]. For instance, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) expression decreased by approximately 200-fold within 72 h after intramyocardial injection of LNPs encapsulating 150 μg of VEGF-A mRNA in mice [13]. Previous studies have demonstrated that sustained delivery using biocompatible materials can improve the therapeutic efficacy of bioactive molecules while minimizing adverse effects [3,14,15]. Thus, we hypothesize that increase RNA retention via an injectable, sustained-release delivery platform may significantly enhance the therapeutic potential of RNA-based treatments for cardiac diseases.

Decellularized ECM is a relatively new material in tissue engineering, with applications as a scaffold for both in vitro and xenograft studies. Additionally, ECM can be processed into an injectable solution that polymerizes at physiological temperatures. Intramyocardial injection of heart-derived ECM hydrogel preserves cardiac function and reduces scarring in various MI models [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. Preclinical and clinical studies suggest that ECM-derived biomaterials are unlikely to provoke severe inflammatory responses, partly due to the removal of immunogenic cytokines [19,20]. Moreover, the primary components of ECM, such as collagen and fibronectin, are naturally occurring fibrous proteins with low immunogenicity [[21], [22], [23], [24]]. ECM-derived materials are well-suited as biocompatible scaffolds for controlled drug release [3]. However, the use of ECM-derived materials for the delivery of LNPs encapsulating RNA molecules has not yet been reported.

This study introduces the development of an ECM-LNP composite designed for the sustained delivery of RNA therapeutics. This composite is biocompatible, injectable, and thermal polymerizable compared to other RNA delivery platforms [25,26]. LNPs were covalently conjugated to the ECM scaffold to slow nanoparticle release, with the release rate adjustable by modifying crosslinker concentrations. The composite was tested in vivo to assess mRNA accumulation and expression. In addition, we have reported that ECM-colchicine co-treatment promotes heart repair in neonatal mice [3]. In this current work, we further investigated the mechanism behind the ECM-colchicine-induced heart repair, and demonstrated that EGFR activity influences macrophage polarization. Additionally, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of ECM-siEGFR@LNP in adult mice with MI, and assessed its influence on the immune response.

2. Methods

2.1. LNP fabrication

LNPs were composed of five components: 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) (Bide Pharm, China), phosphatidylcholine (Aladdin, China), DMG-PEG 2000 (Bide Pharm, China), cholesterol (Aladdin, China), and palmitic acid (Aladdin, China). The lipids were dissolved in pure ethanol (Innochem, China) at predetermined molar ratios (Table 1). The lipid stock solution was stored at −20 °C for up to one month.

Table 1.

Molar ratios of lipids in each formula.

| Formula | DOTAP | Phosphatidylcholine | DMG-PEG | Cholesterol | Palmitic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49.5 | 10 | 1.5 | 38 | 1 |

| 2 | 47.5 | 10 | 1.5 | 36 | 5 |

| 3 | 45 | 10 | 1.5 | 33.5 | 10 |

| 4 | 50 | 10 | 1.5 | 28.5 | 10 |

| 5 | 40 | 10 | 1.5 | 38.5 | 10 |

| 6 | 50 | 10 | 1.5 | 38.5 | 0 |

For luciferase mRNA@LNP fabrication, Luciferase mRNA (GeneScript, China) dissolved in TE buffer (Beyotime, China) was combined with lipids in ethanol at room temperature. The volume ratio of ethanol to water was 1:3, and the weight ratio of lipids to mRNA was 10:1. The solution was vortexed for 30 s and allowed to sit at room temperature for 15 min. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) mRNA@LNP and siEGFR@LNP were prepared using the same method. RNA@LNP was diluted to 0.5 mL using 1 × PBS and then purified using a 30k MWCO ultrafiltration spin column (Beyotime, China) by centrifuge at 3000 g for 10 min. The spin columns were disinfected using 70 % ethanol before use.

2.2. ECM preparation

ECM was prepared following an established protocol [18]. Briefly, pig ventricles were cut into approximately 0.5 cm3 pieces and decellularized in 500 ml of 1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (Aladdin, China) for 3 days. The samples were then washed in 500 ml of 1 % Triton X-100 (Aladdin, China) for 1 day, followed by washing in 1 L of deionized (DI) water for 4 days. Water was changed every day. After washing, decellularized samples were transferred into 50 ml conical tubes and frozen at −80 °C overnight. Sample were then lyophilized for 3 days. The dried samples were digested with pepsin (Sigma, USA) to produce a liquid ECM hydrogel precursor. Every 10 mg of dry ECM was digested with 1 mg of pepsin in pH 2 water. After digesting for 48 h at room temperature, the pH was adjusted to 7.5 using 2N NaOH and 10 × PBS. The ECM solution was stored at 4 °C until use.

2.3. ECM-LNP fabrication

First, the pH of the LNP (encapsulating mRNA) suspension was adjusted to 6.0 using 2N HCl and 10 × PBS. Separately, dissolving 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) (Aladdin, China) in pure ethanol, and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (Aladdin, China) in DI water. The EDC and NHS solutions were then added to the LNP suspension at a 1:100 volume-to-volume ratio. The EDC and NHS concentrations were calculated based on a 10:1 M ratio of EDC/NHS to palmitic acid. For example, 5 μmol of EDC in 10 μl ethanol and 5 μmol of NHS in water were added to 1 ml of pH 6.0 PBS buffer containing 10 μmol of total lipids (0.5 μmol of palmitic acid). The buffer was allowed to sit at room temperature for 15 min after adding EDC and NHS. LNP samples were centrifuged in a 30k MWCO ultrafiltration spin column at 3000 g for 10 min to remove excessive EDC and NHS molecules. LNPs were washed twice in 1 x PBS and then resuspended in the same volume of 1 x PBS as of before ultrafiltration. Subsequently, the LNPs were added to the ECM solution and kept on ice for at least 30 min. The volume ratio of LNPs to ECM was 1:5. The ECM-LNP composite was used immediately.

2.4. Dynamic light scattering and zeta potential analysis

RNA@LNP was diluted with DI water to achieve a concentration of 1 mg RNA@LNP per milliliter. The diameter and zeta potential of the samples were measured using a Zetasizer Nano SZ90 (Malvern, UK). For each measurement, 1.5 mL of the sample was added to a 10 mm quartz cuvette, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) data were recorded for 60 s, with each measurement repeated six times. To measure the zeta potential, RNA@LNP was suspended in 1 mL of 1 × PBS and transferred to a 10 mm glass cuvette. A surface zeta potential cell (Malvern, UK) was used to record the zeta potential. To assess RNA@LNP stability, samples were kept at 25 °C for 30 days. RNA@LNP diameters were measured using DLS on days 1, 3, 7, 14, and 30.

2.5. RNA encapsulation efficiency measurement

Six micrograms of RNA were dissolved in 45 μL of TE buffer, and 60 μg of lipids were added in 15 μL of ethanol. RNA concentrations were measured using the Qubit RNA BR assay (Thermo Fisher, USA). To measure unencapsulated RNA, the RNA@LNP were diluted with TE buffer, and to measure total RNA, a 2 % Triton X-100 TE buffer solution was used. 10 μL of the RNA@LNP sample or RNA standards were added to each well of a 96-well black plate, followed by the addition of 190 μL of Qubit working solution. After a 5-min incubation at room temperature, the fluorescence signal was measured using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN, Switzerland). The excitation wavelength was set at 625 ± 15 nm, and the emission wavelength was set at 665 ± 15 nm. The encapsulation efficiency was calculated using the following equation: .

2.6. Cryogenic SEM and TEM

Cryo-SEM was performed using a Gemini 300 scanning electron microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The ECM-RNA@LNP composite was frozen in liquid nitrogen for 10 min prior to imaging. Samples were then sublimated at −90 °C for 10 min and imaged at −140 °C. The scanning voltage was set to 2 kV.

Cryo-TEM was conducted using a Talos F200C G2 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher, USA). RNA@LNP and empty LNP samples in TE buffer were first stained with 2.5 mg/mL thionine acetate (Aladdin, China) to enhance RNA contrast. Thionine acetate in DI water solution was added at a 1:100 v/v ratio to RNA@LNP and empty LNP samples immediately before cryo-freezing. Three microliters of samples were applied to the sample holder and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were then imaged at 200 kV.

2.7. LNP release from ECM-LNP composite

LNPs containing fluorescein (FITC) (Innochem, China) were prepared by adding 600 μL of ethanol containing 3 mg of lipids to 1.8 mL of DI water containing 0.3 mg of FITC-labeled dextran (MW 4000) (Beyotime, China). The samples were dialyzed against DI water using a 10 kDa dialysis bag for 1 day to remove unencapsulated FITC-dextran. The final FITC-dextran@LNP concentration was approximately 0.86 mg/mL, corresponding to 1.4 μmol of lipids per milliliter or 0.07 μmol of palmitic acid per milliliter. EDC/NHS stock solutions were added to the FITC-dextran@LNP at a 1:100 dilution. To study the release rate of the tuned FITC-dextran@LNP, the final EDC/NHS concentrations were set to 70, 7, 0.7, 0.07, 0.007, 0.0007, 0.00007, and 0 μmol/mL (corresponding to molar ratios of 1:1000 to 1000:1 palmitic acid to EDC/NHS). FITC-dextran@LNP was then added to 150 μL of ECM at a 1:5 volume-to-volume ratio in 1.5 mL tubes and incubated at 37 °C to induce gelation. The ECM-FITC-dextran@LNP composite was incubated in 300 μL of 1 × PBS at room temperature, with buffer changes occurring daily. The sampled buffers were stored in the refrigerator and analyzed using a Spark microplate reader after the final sampling.

2.8. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

RNA@LNP, ECM, and ECM-RNA@LNP were lyophilized before spectrometry. The samples were ground with KBr and processed into KBr pellets. They were then examined using a Spectrum 100 fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer (PerkinElmer, USA). The transmittance from 400 to 4000 wavenumbers was recorded with a resolution of 1 wavenumber. The FT-IR curves were subsequently baseline corrected using Spectragryph (Friedrich Menges).

2.9. X-ray diffraction

ECM and ECM-RNA@LNP composite were lyophilized in glass dishes. Samples were analyzed using a D8 Advance X-ray Diffractometer (Bruker, China). The measurement power was 1600 W. The measurement step was 0.03°, from 10 to 80°.

2.10. Rheometry of ECM and ECM-LNPs

Pre-gel ECM or ECM-RNA@LNP was used for rheometry. To measure the modulus of gelled samples, 800 μL of the liquid sample was added to the sample holder and heated to 37 °C for 5 min. A 10 mm diameter plate was employed for the measurements. The strain was set to 1 %, and the frequency ranged from 10 Hz to 0.1 Hz. To determine the gelation time, the liquid sample was first placed in the sample holder at 25 °C. The moduli were then recorded at 37 °C using 1 % strain and 1 Hz frequency for 6 min.

2.11. Mouse cardiac cell isolation and RNA delivery tests

Mouse cardiac cells were isolated following published protocols [27,28]. In brief, day 1 neonatal mice were quickly rinsed in 75 % ethanol and decapitated. Hearts were harvested and minced into ∼0.5 mm3 pieces using a surgical scissor. The tissue was incubated in digestion buffer for 10 min at 37 °C. The digestion buffer consisted of DMEM supplemented with 0.2 g/L pancreatin (Aladdin, China), and 2070 U/L collagenase II (Yeasen, China). After digestion, the supernatant was transferred into a new conical tube. One milliliter of fetal bovine albumin (FBS) (Every Green, China) was added to end the digestion. Cells were washed in DMEM once and then layered on top of a Percoll (Cytiva, China) gradient. The gradient was prepared by slowly overlaying 40.5 % Percoll solution on top of 58.9 % Percoll solution. After centrifuge at 1800 g for 45 min, cardiomyocytes located at the interface of the low and high-density Percoll layer were collected into a new tube and washed in DMEM twice. Similarly, non-cardiomyocytes (primarily fibroblasts) located in the low-density Percoll layer were harvested and washed. Cells were suspended in DMEM supplemented with 15 % FBS and plated into 1 % gelatin-coated 48-well tissue culture plates. After overnight plating, cells were cultured in maintaining media [2 % FBS, 1 × Pen/Strep in DMEM] containing LNPs for 24 h. Before imaging, dead cells were stained with 2 μg/ml Propidium iodide (Aladdin, China), and nuclei were labeled via 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Aladdin, China).

To investigate the transfection efficiency of different formula, 0.5 μg of GFP mRNA (Genscript, China) incapsulated by 5 μg of lipids were added to each well. Lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher, China) was used as the positive control.

To optimize the N/P ratio, cells were cultured in 200 μL of culture media containing 0.5 μg of GFP mRNA and various amounts of lipids. GFP mRNA@LNP were prepared by mixing 0.5 μg of mRNA in 30 μL of Opti-MEM with 10 μL of ethanol containing 50, 5, 0.5, or 0.05 μg of lipids, which correspond to 26:1, 2.6:1, 0.26:1, 0.026:1 nitrogen/phosphate (N/P) ratios. The N/P ratio was calculated according to the following equation:

where

2.12. Bone marrow derived macrophages isolation and culture

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) were isolated from the hind limbs of mice following a published protocol [29]. After euthanasia, hind limbs were harvested and disinfected in 70 % ethanol. Muscles were removed using forceps and scrapes. The epiphyses of the femur and tibia were removed to expose the bone marrow cavity. Bone marrow was flushed from the bones using 1xPBS through a 23G needle into a 50 mL conical tube. Bone marrow was centrifuged at 200×g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Red blood cells were lysed using Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Yeasen, China). After washing in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % Penicillin/Streptomycin, the remaining cells were suspended in 1 mL of DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS, 1 % Penicillin/Streptomycin, and 25 ng/mL mouse CSF-1 (Abclonal, China) [bone marrow culture medium], and then filtered through a 100 μm cell strainer. Cells were seeded into cell culture plates and cultured for 4 days. Afterward, cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with EGFR siRNA or inhibitor for 1 day. For siRNA treatments, cells were exposed to DMEM containing 100 nM siRNA (siBDM1999A, RIBO Bio, China). The transfection was facilitated using Lipofectamine 3000 following the manufacturer's protocol. For gefitinib treatment, cells were cultured in DMEM containing 1 μM gefitinib. Both EGFR and NC siRNAs were purchased from RiboBio, China.

Cells cultured in 12-well plates were harvested for western blot analysis. After washing with 1 × PBS, cells were lysed using 100 μl RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Following centrifugation, protein concentrations in the supernatant were measured using a BCA assay, and 20 μg of protein per sample was used for western blot analysis.

Cells in 48-well plates were used for immunostaining. After washing with 1 × PBS, cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed three times with 1 × PBS, permeabilized with 1 × PBS containing 0.1 % Triton X-100 for 10 min, and then blocked with washing buffer containing 10 % normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in washing buffer containing 1 % BSA for 2 h, followed by secondary antibodies for 1 h. Finally, cells were stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI in 1 × PBS and washed three times in 1 × PBS. Images were captured using a Ti-2E fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Japan) at 10 × magnification. For each well, three random images were taken within 24 h of staining.

2.13. In vivo fluorescent and chemiluminescent imaging

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Shanghai Jiaotong University (SJTU).

CD-1 mice were used due to their outbred nature and relative ease of handling. Week 8 CD-1 mice (Charles River, China) were first anesthetized with 5 % isoflurane (RWD, China) and then transferred to the surgical area. Anesthesia was maintained with 1.5 % isoflurane. Body temperature was maintained using a heating pad connected to a temperature probe, and the limbs were secured to the surgical plate with sterilized tape. Mice were intubated with a 22G tube connected to a ventilator (KEW Basis, China), with a tidal volume of 1 mL and a frequency of 100 strokes per minute. After shaving the chest hair, the skin was cleaned with povidone iodine and 70 % ethanol. Incisions were made through the skin and the fifth intercostal space to expose the left ventricle. For whole-body imaging, 50 μL of the sample was injected into the myocardium using a 100 μL Hamilton syringe connected to a 33G needle, with three injections made in the myocardium. For major organ imaging, 30 μL of the sample was injected into the myocardium. Following the injections, the incisions were closed with 6-0 nylon sutures. The incubation tube was removed, and the mice were returned to their cages once they had awakened.

LNPs were conjugated to ECM using EDC/NHS at a molar ratio of 1 μmol lipids to 0.5 μmol EDC/NHS. In the mRNA delivery experiment, luciferase mRNA@LNP (diluted 1:5 in 1 × PBS) or ECM-luc mRNA@LNP (diluted 1:5 in ECM) was injected. LNPs were conjugated to ECM using EDC/NHS at a molar ratio of 1 μmol lipids to 0.5 μmol EDC/NHS. Approximately 4 μg of luciferase mRNA was administered to each mouse.

Animals were imaged using an IVIS (PerkinElmer, USA) on days 1, 3, and 7 after injection. Mice were anesthetized with 5 % isoflurane and maintained with 2 % isoflurane. Hair removal was achieved using a hair removal cream. Luminescence mode was used to assess luciferase activity. Prior to imaging, syringe-filtered D-luciferin potassium salt (Beyotime, China), dissolved in saline, was intraperitoneally injected at 150 μg D-luciferin per gram of body weight. Imaging was performed 10 min after injection. Images were analyzed using Living Image 4.7.3 (PerkinElmer, USA). Signals from the abdomen and limbs, which were due to auto-luminescence, were excluded from further analysis.

2.14. Adult mice myocardial infarction

Mice were prepared for surgery as described above. Week 8 CD-1 mice were randomly assigned to sham, MI control, NC siRNA@LNP, siEGFR@LNP, ECM, ECM-siEGFR@LNP groups. For the EGFR siRNA injection experiment, 50 μL of NC siRNA@LNP, siEGFR@LNP, or ECM-siEGFR@LNP was injected into the myocardium. siRNA@LNP was freshly prepared before the in vivo experiments. LNPs were conjugated to ECM using EDC/NHS at a molar ratio of 1 μmol lipids to 0.5 μmol EDC/NHS. Each mouse received 13 μg of siRNA, encapsulated by 130 μg of lipids. Three injections were administered to each heart. Mice were euthanized 3 days after injection, and left ventricles were used for protein extraction and Western blot analysis.

To induce MI, the heart was exposed, and an 8-0 nylon suture was used to ligate the left anterior descending artery approximately 3 mm below the left atrium. Successful ligation was confirmed by a color change. Following this, 50 μL of siEGFR@LNP, ECM, ECM-NC siRNA@LNP, or ECM-siEGFR@LNP was injected into the left ventricle. Each heart received 1 nM of siRNA. Three injections were made: one above the ligation site and two in the infarct area. In MI control hearts, 1 × PBS was injected, and no ligation was performed in the sham group. After recovering from anesthesia, the mice were returned to their cages.

2.15. Neonatal mice myocardial infarction

Neonatal MI was induced following an established protocol [30]. Briefly, Day 5 mice were anesthetized via hypothermia and placed on an ice bag during the surgery. After immobilizing the limbs with tape, the skin was disinfected with povidone iodine and 70 % ethanol. Incisions were made through the skin, muscle, and the fourth intercostal space. Once the left ventricle was exposed, the LAD artery was ligated using a 10-0 nylon suture. Three microliters of ECM, 0.083 mg/mL colchicine, or ECM-nanostructured lipid carrier-colchicine (0.25 mg colchicine per milliliter) were injected into the myocardium. Two injections were made in each heart, one above the ligation site and one in the infarct zone. The incisions in the intercostal space and muscles were closed using a 6-0 suture, and the skin incision was sealed with skin glue (3M, USA). After surgery, the mice were warmed under a heating lamp for 15–60 s before being returned to their littermates. Echocardiography was performed on day 21 post-surgery, while hearts for RNA sequencing and Western blot analysis were harvested on day 5 post-surgery.

2.16. Echocardiography

Cardiac function was assessed using echocardiography at 1 and 4 weeks post-MI. Mice were anesthetized with 5 % isoflurane, which was maintained at 1.5 % during the procedure. They were then placed on a heating plate, with limbs secured using tape. Heart rate was monitored and adjusted to between 400 and 500 beats per minute by modulating the isoflurane concentration. Left ventricular function was recorded using a Vevo 3100 system (FujiFilm, Japan) with an MX550 probe. M-mode recordings were captured and analyzed with Vevo Studio (FujiFilm, Japan).

2.17. Histological analysis of hearts

After the week 4 echocardiography, mice hearts were harvested. Hearts were rinsed in ice-cold saline containing 5 U/ml heparin, then fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 72 h. Following fixation, the samples were washed in 1 × PBS, equilibrated in sucrose buffers, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura, USA). The frozen hearts were sectioned into 10 μm thick slices using a cryotome (Leica CM1950, Germany) and mounted onto adhesive microscope slides. Samples were stored at −20 °C until staining.

To evaluate the potential adverse effects of LNPs in vivo, heart, lungs, livers, kidneys, and spleen were harvested on day 3 after intramyocardial injection of LNP or ECM-LNP. Samples were fixed in 4 % PFA, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 10 μm slices. Histological analyses were performed using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and Masson staining.

For immunostaining, sections were first washed three times with 1 × TBS, permeabilized with 0.025 % Triton X-100 in TBS for 5 min, and blocked with 10 % normal goat serum in TBS for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibody incubation occurred overnight at 4 °C, followed by three TBS washes. The sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI (Aladdin, China) for 10 min, and washed in TBS three times. Anti-fading mounting medium (Solarbio, China) was applied to each section before sealing with coverslips using nail polish. The antibody staining buffer consisted of 1 × TBS with 1 % BSA (Innochem, China).

Masson's trichrome staining was performed using a kit (Solarbio, China). Sections were washed in TBS, mordanted in Bouin's fixative at 56 °C for 1 h, and stained with Weigert's hematoxylin, Biebrich scarlet, and Aniline blue as per the kit instructions. Sections were sealed with solidified mounting medium (Solarbio, China).

Alpha-SMA (67735-1-IG), vimentin (80232-1-RR), CD31 (28083-1-AP), CD206 (18704-1-AP), CD68 (66231-2-Ig), iNOS (18985-1-AP), pAKT (28731-1-AP), and pMAPK (28733-1-AP) antibodies were obtained from Proteintech, while secondary antibodies were purchased from Thermo Fisher. The final primary antibody concentration was 3 μg/ml, and the secondary antibody concentration was 4 μg/ml.

Imaging was performed using an Olympus BX63 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) at 20 × magnification for vasculature and 40 × magnification for macrophages and fibroblasts. Six random images were taken from each section, focusing on the infarct area (for fibroblast and macrophage analysis) or the border zone (for vasculature analysis). Masson's trichrome-stained sections were imaged at 20 × magnification and stitched to create a whole heart image.

2.18. Western blot of tissue sample

Forty micrograms of fresh heart tissue were homogenized in 200 μL of RIPA buffer (Epizyme, China) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Epizyme, China) using a plastic pestle attached to a hand homogenizer (Jingxin, China). Following homogenization, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay (Beyotime, China). For each sample, 20 μg of protein was used for western blot analysis.

The protein samples were mixed with 5 × loading buffer (Epizyme, China) and DI water to a final volume of 20 μL. After heating at 95 °C for 10 min, the samples were briefly centrifuged, vortexed, and loaded onto pre-made 4–20 % PAGE gels (Beyotime, China) for electrophoresis. The voltage was set to 120 V, and the gels ran for 90 min. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to 0.4 μm PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA) via wet transfer at 400 mA for 60 min with the transfer tank kept on ice. After the transfer, the PVDF membranes were washed three times with 1 × TBS containing 0.1 % Tween-20 (washing buffer) and blocked in 1 % milk or 1 % BSA in washing buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Following primary incubation, the membranes were washed three times with washing buffer and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After three additional washes, the membranes were imaged using the CFX Opus 96 (Bio-Rad, USA).

Primary antibodies against Gapdh (60004-1-Ig) and Sost (21933-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech; Wnt7b (A7746), EGFR (A11577), and phospho-EGFR (Y1068) (AP0301) were purchased from Abclonal, while HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Proteintech. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:1000, except for Gapdh, which was diluted 1:50,000. Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:10,000 in washing buffer containing 1 % BSA. ECL substrate (Epizyme, China) was used to detect the signal, and the intensity of the ECL signal was quantified using ImageJ software.

2.19. RNA sequencing of cardiac tissue

Hearts for RNA sequencing were harvested from day 5 post-MI mice. Approximately 20 mg of cardiac tissue from the infarct and border zones were dissected and used for RNA extraction via the Trizol method. RNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher, USA), and RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA). The transcriptome library was prepared using the VAHTS Universal V5 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Vazyme, China). mRNA sequencing was performed by OEbiotech (Shanghai, China) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between MI, ECM, and ECM-siEGFR@LNP groups were identified using DESeq2 [31]. Thresholds were set at q-value <0.05 with a fold change >2 or <0.5. Further analysis of DEGs was performed using Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment [32], Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis [33], Reactome, and WikiPathways enrichment. Additionally, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was conducted on all genes [34], and protein-protein interactions were analyzed using the STRING database [35].

2.20. qPCR of cardiac tissue

Total mRNA was extracted from freshly isolated hearts using RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, China). After measuring the RNA concentrations using a NanoDrop One (ThermoFisher, China), 2 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (Yeasen, China). Samples were diluted 1:5 using RNase-free water and used for qPCR. qPCR was performed using a SYBR Green-based kit (Yeasen, China) on a qTOWER3G real-time thermal cycler (Analytik Jena, Germany). Cycle threshold values were analyzed using qPCRsoft ver 4.1 (Analytik Jena, Germany).

2.21. Flow cytometry of heart cells

Heart cell isolation protocol and cell gating strategy were adopted from published articles [[36], [37], [38]]. Thirteen micrograms of EGFR siRNA encapsulated by 130 μg of lipids were suspended in 50 μl of 1xPBS and injected into the myocardium immediately after LAD ligation in each mouse. NC siRNAs were injected into the MI control mice. Hearts were harvested on day 5 after MI and be used immediately for cell isolation. In brief, after washing in cold 1xPBS once, each heart was minced to approximately 1 mm3 pieces using a surgical scissor. After centrifuge at 50 g for 3 min, hearts were resuspended in RPMI1640 buffer containing 1 mg/ml collagenase II (300U/mg, Yeasen Bio., China). Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Afterward, samples were filtered using 70 μm and 40 μm cell strainers. Large chunks on the 70 μm strainer were triturated using the rough end of a 1 mL syringe plunger. Strainers were washed using 5 mL of 1xPBS containing 2 % BSA and 2 mM EDTA. Samples were then centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min, and the supernatants were discarded. Cells were fixed in 1xPBS containing 2 % BSA and 1 % PFA for 10 min on ice, centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min, and resuspended in 1xPBS containing 1 % BSA [staining buffer]. Samples were kept in fridge and be used within 24 h. For flow cytometry, 3 × 106 cells were used. Cells were blocked using 1xPBS containing 1 % BSA and Fc blocker for 10 min on ice. Afterward, cells were centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min and resuspended in 300 μl of staining buffer containing fluorophore-conjugated antibodies. After incubating on ice for 1 h, samples were washed in 1xPBS once and resuspended in 1xPBS for flow cytometry. Flow cytometry was performed using a BD LSRFortessa cell analyzer (US.). The results were further analyzed using Flowjo v10.9.0 (BD, US.). PerCP-Cyanine5.5-CD11b (M1/70) (CPY5-65055), FITC-MHC II (I-A/I-E) (FITC-65122-25UG), CoraLite Plus 750-CD206 (CL750-98031) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech (China). PE-CD86 (A27137), ABflo 594-CD150 (A24973), and ABflo 647-CD310 (MGL1/2) (A25069) antibodies were purchased from Abclonal (China).

CD11b+ and CD86+ cells were identified as macrophages. Among the macrophages, CD206+ cells were identified as M2 macrophage, and CD206-cells were identified as M1 macrophage. Among the M2 macrophages, CD301+ cells were identified as M2a macrophage, CD150+ cells were identified as M2c macrophage, and CD301-/CD150-/MHC II + cells were identified as M2b macrophage.

To investigate the uptake of LNPs, GFP mRNA was delivered into the heart via an ECM-LNP composite. Forty microliters of ECM-LNP composite containing 4 μg of GFP mRNA were injected into the myocardium. Hearts were harvested 1 day post-injection for flow cytometry analysis. After fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.1 % Triton X-100 and blocked using staining buffer supplemented with Fc blocker and 1 % normal goat serum. Cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells were identified by staining with unconjugated primary antibodies followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. Specifically, cardiomyocytes were labeled with cardiac troponin T antibody, smooth muscle cells with alpha-smooth muscle actin antibody, fibroblasts with vimentin antibody, and endothelial cells with CD31 antibody. Leukocytes were stained directly using fluorophore-conjugated CD45 antibody. Following staining, samples were analyzed by flow cytometry within 1 h. Collected events were down-sampled to 1 × 106 events per sample using FlowJo software before further analysis.

2.22. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad, USA). Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using the t-test, while comparisons among three or more groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA. For comparisons between different groups across various time points, two-way ANOVA was used. Post-hoc inter-group comparisons for three or more groups were performed using Tukey's test. A 95 % confidence interval was applied for all analyses. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance, along with average values and standard deviations, are indicated in the plots.

3. Results

3.1. Designing carboxyl-functionalized lipid nanoparticles for RNA delivery

To achieve site-specific delivery, we developed an ECM-LNP composite for the heart. The LNPs were composed of cationic lipid DOTAP, phosphatidylcholine, DMG-PEG 2000, cholesterol, and palmitic acid. Palmitic acid provided carboxyl groups for EDC/NHS-induced crosslinking (Fig. 1A). Six formulations were tested to assess the impact of each component on particle size, stability, and RNA encapsulation (Fig. 1B). Cryogenic TEM revealed that lipids with RNAs formed circular vesicles, with RNAs arranged concentrically within the particles (Fig. 1C). The RNA encapsulation efficiency of various LNP formulations was then investigated using a fluorescent RNA assay (Fig. S1A). Increasing the molar ratio of palmitic acid slightly decreased RNA encapsulation efficiency (Fig. 1D), possibly due to the lowered N:P ratio.

Fig. 1.

Fabrication and characterization of carboxyl-functionalized LNPs. (A) Schematic illustration of ECM-LNP fabrication. (B) Molar ratios of DOTAP, cholesterol, and palmitic acid were varied across different LNP formulas. (C) Cryo-TEM analysis showed that lipids without RNAs formed empty vesicles, whereas LNPs containing RNAs displayed concentric RNA alignment within the particles. (D) Lipid molar ratios impacted RNA encapsulation efficiency, with approximately 75 % efficiency in Formula 2. (E) RNA@LNP diameters were measured using DLS. (F) Formula 2 exhibited a relatively stable diameter over 30 days. In addition, palmitic acid reduced RNA@LNP (G) diameter and (H) polydispersity index. (I) Variations in the molar ratio of lipids influenced the RNA@LNP zeta potential, with Formula 2 showing the highest zeta potential. (J) mRNA delivery efficiency was assessed using primary cardiomyocytes and non-cardiomyocytes (primarily cardiac fibroblasts), which expressed GFP proteins after 24 h of incubation with medium containing 0.5 μg mRNA and 5 μg lipids. (K) All formulas except formula 5 exhibited similar densities of GFP + cardiomyocytes compared to the positive control. (L) Similarly, the densities of GFP + non-cardiomyocytes were not changed by the various treatments. (n = 3. One-way ANOVA and Tukey's test applied; Naked mRNA was excluded from statistical analyses in panel K and L. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.)

The diameter and zeta potential of RNA@LNP were analyzed using DLS (Fig. 1E and S1B). mRNA vaccines are recommended to be stored below 4 °C [39,40]. To evaluate the stability of RNA@LNP under relatively adverse conditions, samples were kept at 25 °C over 30 days. The average diameters of all six formulas slightly decreased over 30 days, with the day 30/day 1 diameter ratio indicating that Formulas 2 had superior stability (Fig. 1F). The mean RNA@LNP diameter ranged from 150 to 210 nm. Incorporation of palmitic acid reduced the diameter (Fig. 1G) and polydispersity index (Fig. 1H). In addition, varying the ratio of palmitic acid changed the zeta potential of RNA@LNP (Fig. 1I). These results suggest that palmitic acid reduces RNA@LNP diameter and enhances stability. Similar effects of palmitic acid on liposome size have been reported by other groups [41], likely due to its role in directing phospholipid orientation and increasing bilayer density [42]. TEM measurements typically report smaller particle sizes compared to DLS due to the desiccated, high-vacuum environment of TEM imaging. Previous studies have noted that DLS measurements can be approximately 100 % larger than those obtained by TEM [27,28]. Therefore, these data collaboratively confirming the successful encapsulation of RNA within the LNPs.

The mRNA delivery efficiency was analyzed using mouse primary cardiac cells to estimate the transfection after intramyocardial administration. GFP expression was detected in cardiomyocytes and non-cardiomyocytes (primarily cardiac fibroblasts) 24 h after treatment (Fig. 1J). Formula 2 exhibited relatively high GFP + cell densities in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1K) and non-cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1L). A similar trend was observed in GFP fluorescence intensity, though the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. S1C and S1D). Apoptotic cells were labeled with propidium iodide (Fig. S1E). No significant difference was observed in the densities of PI + cardiomyocytes and non-cardiomyocytes (Fig. S1F and S1G). Based on these characterizations, Formula 2 was selected for further in vitro and in vivo studies due to its high stability, RNA encapsulation efficiency, and mRNA delivery efficiency.

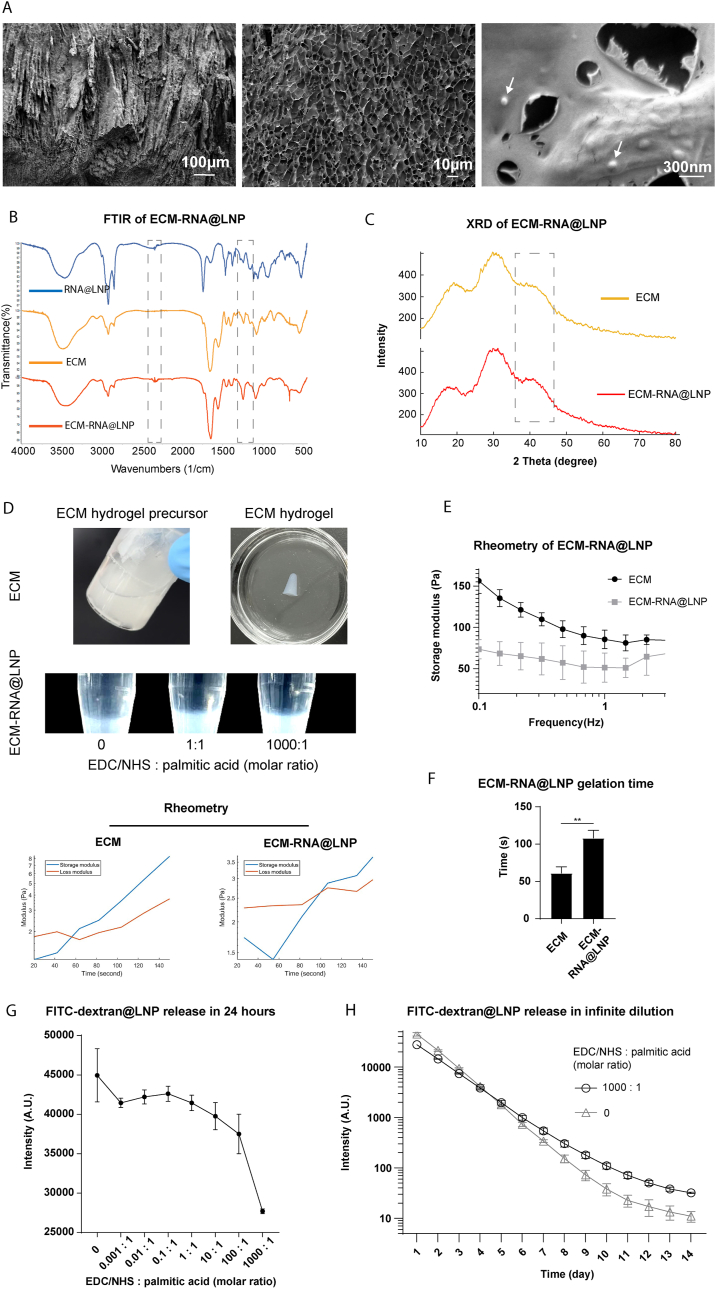

3.2. ECM-LNP composite fabrication and characterization

LNPs were covalently conjugated to the ECM scaffold using EDC/NHS chemistry. The ECM-RNA@LNP composite was visualized with cryo-SEM. Imaging revealed that the ECM-RNA@LNP composite had a meshwork structure with LNP embedded within the ECM scaffold (Fig. 2A). FT-IR partially confirmed LNP conjugation by showing an enhanced C-N stretching peak at 1246 cm−1 in the EDC/NHS-treated ECM-LNP composite compared to ECM hydrogel and RNA@LNP (Fig. 2B). Additionally, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis indicated a broad peak around 40°, suggesting the incorporation of LNP into the ECM scaffold (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that the ECM-LNP composite possesses a meshwork microstructure suitable for drug loading and that LNPs were linked to the ECM scaffold.

Fig. 2.

ECM-LNP composite characterization. (A) The ECM-RNA@LNP exhibited a meshwork microstructure under cryogenic SEM. LNPs, appearing as bright dots (white arrows), were closely attached to the ECM scaffold following EDC/NHS conjugation. (B) Conjugation of ECM and LNPs was assessed by FT-IR, which showed amplified C-N stretching and C=O stretching peaks. (C) XRD measurement indicated a peak around 40° in ECM-LNP composite. (D) ECM hydrogel precursor, ECM hydrogel, and ECM-LNP composites treated with various concentrations of EDC/NHS. The storage and loss moduli of the ECM hydrogel and ECM-LNP composite precursors at 37 °C were measured. (E) Rheometry analysis showed that the ECM-LNP composite had a lower storage modulus than the ECM hydrogel. (F) The gelation time was approximately 110 s for the ECM-LNP composite and about 60 s for the ECM. (G) LNP release from the ECM-LNP composite was examined using LNPs containing FITC-dextran. Increasing the EDC/NHS concentration decreased the FITC-dextran@LNP release rate. (H) ECM-LNP composites treated with EDC/NHS exhibited a more consistent FITC-dextran@LNPs release in 14 days. (n = 3 in panel E to H. t-test applied for panel F. ∗∗p < 0.01. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.)

The liquid ECM hydrogel precursor transformed into a solid hydrogel through temperature-induced fiber protein self-assembly (Fig. 2D). The mechanical properties and gelation time of the ECM-RNA@LNP composite were analyzed using Rheometry. The solid ECM-RNA@LNP composite exhibited a lower storage modulus compared to the ECM hydrogel (Fig. 2E). The gelation time, determined by the crossover point of the storage and loss moduli, was approximately 60 s for the ECM precursor and approximately 110 s for the ECM-LNP precursor (Fig. 2F).

The release rate of LNPs can be modulated by adjusting the crosslinker concentration. To assess the impact of EDC/NHS concentration on LNP release, LNPs containing FITC-labeled dextran were used. Increasing the EDC/NHS concentration resulted in a reduced FITC-dextran@LNP release rate from the ECM-LNP composite over 24 h (Fig. 2G). Further analysis over 14 days revealed that ECM-LNP composites treated with EDC/NHS released FITC-dextran@LNPs at a more consistent rate compared to samples with no EDC/NHS treatment (Fig. 2H).

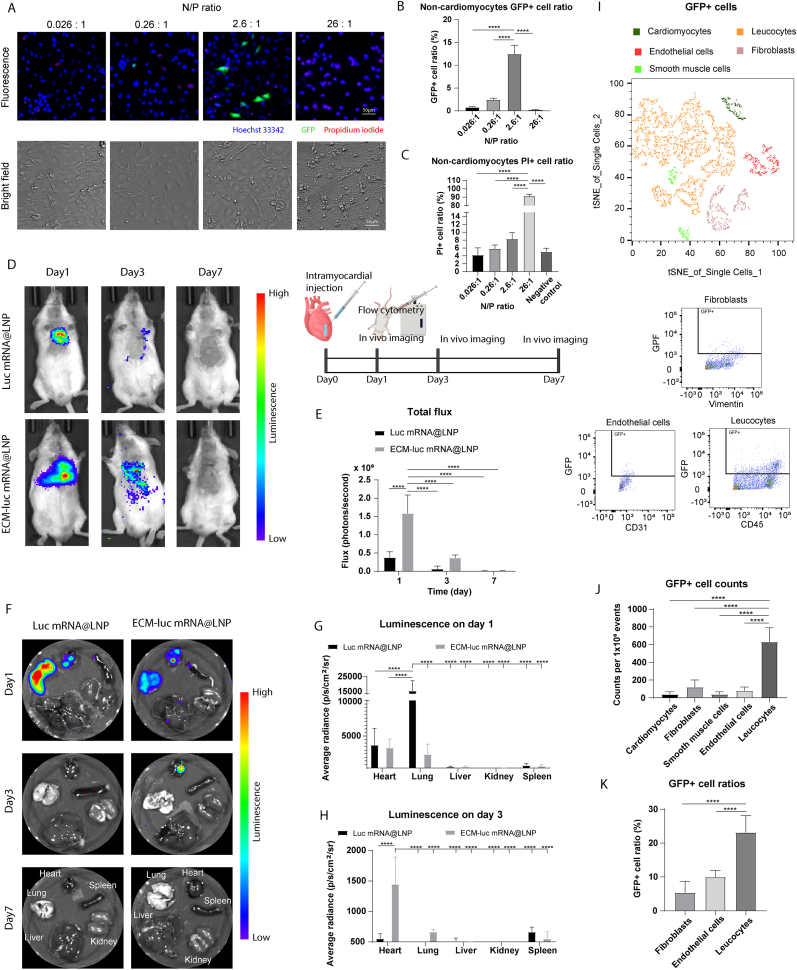

3.3. ECM-LNP composite increased RNA retention in the heart

The lipid dosage was optimized to improve the mRNA delivery efficiency. The N/P ratio showed a biphasic effect on mRNA transfection efficiency (Fig. 3A). The highest GFP expression was achieved with a 2.6:1 N/P ratio (10:1 lipid/mRNA weight ratio) in non-cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3B). Lowering the N/P ratio reduced mRNA encapsulation efficiency. On the other hand, cells treated with 26:1 N/P ratio exhibited a higher percentage of dead cells according to propidium iodide assay (Fig. 3C). Similar results were observed in cardiomyocytes as well (Fig. S2A–C.). Therefore, a 2.6:1 N/P ratio was selected for further experiments.

Fig. 3.

ECM-LNP composite increased mRNA retention in mice hearts. (A) The N/P ratio influences mRNA delivery efficiency in non-cardiomyocytes (primarily cardiac fibroblasts). (B) The maximum GFP + cell ratio was achieved with a 2.6:1 N/P ratio, while deviations from this ratio compromised mRNA expression. (C) The 26:1 N/P ratio exhibited high toxicity toward non-cardiomyocytes. (D) LNPs or ECM-LNPs containing luciferase mRNA were injected into the mice myocardium. (E) The total flux of chemiluminescence was greater in the ECM-luc mRNA@LNP group compared to the Luc mRNA@LNP group on day 1. The ECM-luc mRNA@LNP group also showed higher total flux on day 3, though the difference was not statistically significant. (F) Luminescence in major organs was further analyzed. (G) Strong luminescence was detected in the hearts and lungs on day 1 post-intramyocardial injection in both groups, with the lungs in the Luc mRNA@LNP group displaying the highest signal. (H) By day 3, luminescence was only detected in the hearts of the ECM-luc mRNA@LNP group. (I) GFP mRNA expression in cardiac cells were analyzed using flow cytometry. The population of various cell types were visualized using tSNE plot. (J) The number of GFP + leukocytes was significantly higher than that of other cell types. (K) Moreover, leukocytes showed a greater proportion of GFP + cells relative to their total population compared to other cardiac cell types. (n = 3 in panel B and C, n = 4 in panel E to H, n = 6 in panel J to K. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey's test applied. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.)

mRNA retention and expression were assessed using ECM-LNP composites containing luciferase mRNA (Fig. 3D). The total flux of the ECM-luc mRNA@LNP group on day 1 was the highest compared to other conditions (Fig. 3E). Analysis of luminescence signals in major organs revealed that, on day 1, the lungs in the Luc mRNA@LNP group displayed the highest radiance, approximately three times higher than that observed in the hearts of both groups (Fig. 3F and G). However, luminescence persisted in the hearts of the ECM-luc mRNA@LNP group until day 3, while no detectable luminescence remained in the hearts or lungs of the Luc mRNA@LNP group by this time point (Fig. 3H). These findings demonstrate that ECM-LNP significantly enhances mRNA retention and prolongs expression compared to LNP alone. To evaluate potential adverse effects following intramyocardial injection of ECM-RNA@LNP, histological analyses of the heart, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys were performed on day 3 post-injection. The results demonstrated no significant morphological changes or evidence of extensive fibrosis in major organs following treatment with either LNP or ECM-LNP (Fig. S3A).

To assess mRNA uptake by cardiac cells, GFP expression was analyzed by flow cytometry 1 day after ECM-GFP mRNA@LNP injection (Fig. 3I and Fig. S4A). tSNE mapping revealed that leukocytes constituted the largest proportion of GFP + cells. Significantly more GFP + leukocytes were identified compared to cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells (Fig. 3J), which is probably due to the high phagocytic activity of leukocytes [43,44]. Furthermore, the proportion of GFP + leukocytes relative to total leukocytes exceeded that of other cell types (Fig. 3K). These results suggest that leukocytes are the primary uptake targets for ECM-LNP-delivered RNAs, positioning the ECM-LNP composite as an effective vehicle for RNA-based therapies targeting immune cells.

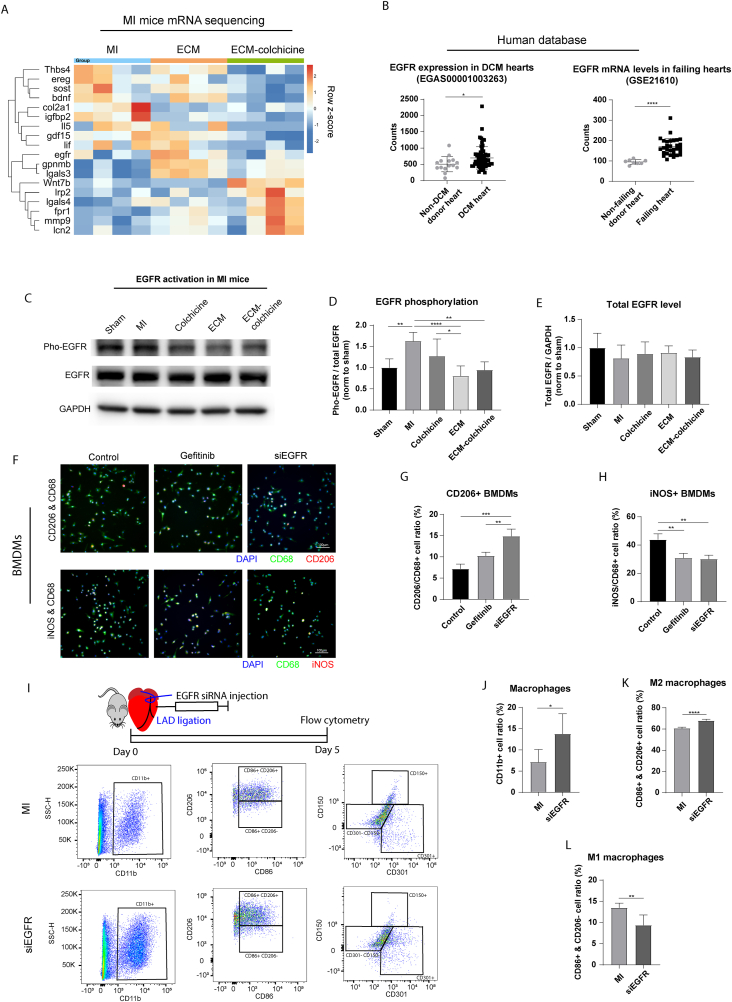

3.4. Interfering with EGFR activation promoted M2-like macrophage polarization

We have previously demonstrated that co-treatment with ECM and colchicine prevented ventricular remodeling in post-MI neonatal mice [3]. At 3 weeks post-MI, mice receiving the combination treatment showed improved cardiac function compared to the MI control group (Fig. S5A and S5B). In addition, ECM-colchicine promoted macrophage M2 polarization in the infarct area (Fig. S5C). Transcriptome analysis on day 5 post-MI highlighted several EGFR-related genes that were differentially expressed after ECM-colchicine treatment (Fig. 4A and S5D). To further validate the relationship between EGFR activity and cardiac injury response, EGFR expression in cardiomyopathy patients was examined using public datasets (Fig. S5E). Both dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure patient groups exhibited significantly increased EGFR mRNA expression compared to non-disease donor hearts (Fig. 4B). Western blot of mice hearts on day 5 post-MI hearts demonstrated that ECM-colchicine co-treatment reduced the ratio of phospho-EGFR to total EGFR, indicating reduced EGFR activation (Fig. 4C–E). Furthermore, ECM-colchicine co-treatment modulated the expression of EGFR-related sclerostin and wnt7b (Fig. S5F–H). These findings suggest an association between elevated EGFR expression and cardiomyopathies.

Fig. 4.

EGFR activation was involved in the regulation of macrophage M2 polarization after MI. (A) Transcriptomic analysis revealed EGFR as a potential regulator of cardiac post-injury response in mice. (B) Patient database demonstrated that dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and heart failure increased EGFR mRNA levels compared to non-disease hearts. (C) EGFR activity in mice hearts was assessed by western blot. (D) ECM-colchicine treatment significantly decreased EGFR phosphorylation compared to MI control. (E) No significant changes in total EGFR levels were observed among the different treatments. (F) The effects of EGFR inhibition in macrophage polarization were further analyzed using BMDMs. (G) EGFR siRNA increased the ratio of M2-like macrophage compared to control and gefitinib treatment. (H) Gefitinib and EGFR siRNA reduced the ratio of M1-like macrophage. (I) Macrophage polarization in siEGFR-treated hearts on day 5 after MI was analyzed using flow cytometry. EGFR siRNA increased the ratios of (J) CD11b + pan-macrophages and (K) CD11b+/CD86+/CD206+ M2 macrophages compared to the MI control. (L) In contrast, EGFR siRNA reduced the ratio of CD11b+/CD86+/CD206- M1 macrophages in comparison to the MI control. (n = 6 in panel D and E, n = 3 in panel G and H, n = 6 in panel J to L. One-way ANOVA and Tukey's test applied. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.)

The role of EGFR in macrophage polarization was explored using the bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs). An EGFR siRNA was employed after comparing the effectiveness of various EGFR siRNAs in suppressing EGFR activity (Fig. S5I–K). Cell polarization was examined through immunostaining (Fig. 4F). Gefitinib, an EGFR inhibitor, served as a positive control. Treatment with EGFR siRNA significantly enhanced M2-like polarization compared to both control and gefitinib treatments (Fig. 4G). Additionally, gefitinib and EGFR siRNA reduced the ratio of iNOS + M1-like macrophages compared to the control (Fig. 4H). Similar trends have also been observed in published works studying the relationship between EGFR inhibition and macrophage polarization [7,8]. To validate the effect of EGFR inhibition on macrophage polarization in vivo, macrophage subtypes in the hearts of adult mice on day 5 post-MI were analyzed via flow cytometry (Fig. 4I). EGFR siRNA increased the ratios of pan-macrophages (Fig. 4J) and M2 macrophages (Fig. 4K) compared to the MI control. In contrast, EGFR siRNA reduced the ratio of M1 macrophages (Fig. 4L). The ratios of M2a and M2b macrophages were not changed by EGFR siRNA treatment (Fig. S5L–N). These findings suggest that inhibiting EGFR expression promotes M2 macrophage polarization, potentially contributing to anti-inflammatory responses.

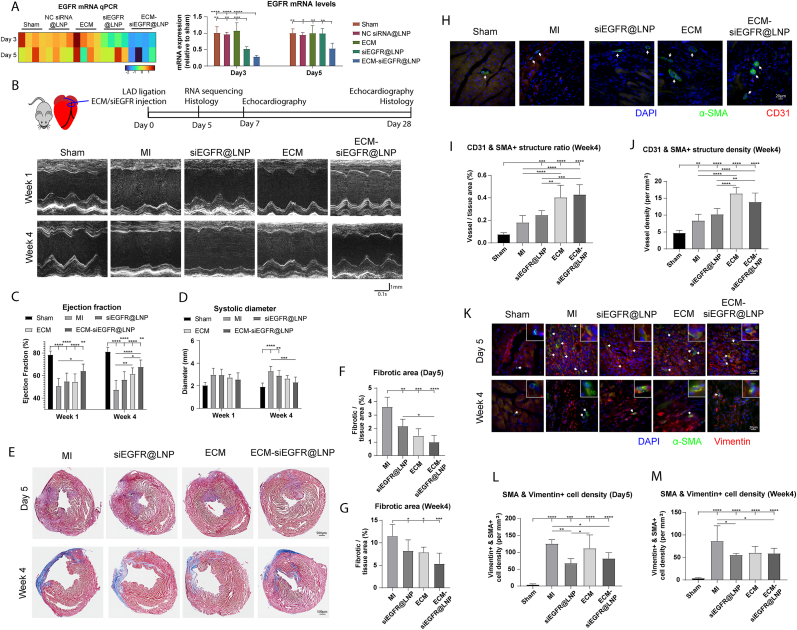

3.5. ECM-siEGFR@LNP preserved cardiac function in post-MI mice

To assess the impact of EGFR siRNA treatment in vivo, EGFR transcription, expression, and phosphorylation were examined. ECM-siEGFR@LNP reduced the EGFR mRNA levels on day 3 and 5 after injection compared to the other groups (Fig. 5A). The phosphorylated EGFR and pan-EGFR levels were lowered by ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment compared to NC siRNA@LNP control on day 3 following intramyocardial administration (Fig. S6A–D).

Fig. 5.

ECM-siEGFR@LNP preserved cardiac function after MI. (A) EGFR mRNA level was first examined on day 3 and 5 following siRNA intramyocardial injection. ECM-siEGFR@LNP lowered EGFR mRNA levels compared to the other groups at both time points. (B) In the mice MI model, echocardiography was used to measure cardiac function and dimensions. (C) ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment preserved ejection fraction compared to MI control at week 1 and week 4. (D) ECM-siEGFR@LNP also lowered the end-systolic diameter at week 4 post-MI. (E) The fibrotic area was assessed using Masson's Trichrome staining. ECM-siEGFR@LNP group exhibited the lowest fibrotic area on (F) day 5 and (G) day 28 post-MI. (H) Vasculature-like structures were labeled using α-SMA and CD31. ECM-siEGFR@LNP groups exhibited higher (I) vessel area and (J) vessel density than sham, MI control, and siEGFR@LNP at week 4 post-MI. (K) Fibroblast activation was examined through immunostaining for α-SMA and vimentin. ECM-siEGFR@LNP reduced the density of myofibroblast compared to the MI control on (L) day 5 and at (M) week 4 post-MI. (n = 7 in panel F to M; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's test applied. n = 4 in panel A, n = 7–8 in panel C and D; two-way ANOVA and Tukey's test applied, significance levels at the same week were labeled. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.)

Next, the therapeutic efficacy of ECM-siEGFR@LNP was evaluated in an adult mouse model of MI (Fig. 5B). Treatment with ECM-siEGFR@LNP significantly improved ejection fraction at week 1 and week 4 compared to the MI control group (Fig. 5C). Fractional shortening followed a similar pattern (Fig. S6E). Additionally, ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment demonstrated trends toward reducing systolic diameter (Fig. 5D) and diastolic diameter (Fig. S6F) relative to the MI control. Although ECM-NC siRNA@LNP treatment also exhibited beneficial effects on cardiac remodeling, the improvements were less pronounced than those observed with ECM-siEGFR@LNP (Fig. S6G). These results indicate that ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment preserves cardiac function post-MI.

Cardiac fibrosis was assessed on day 5 and day 28 post-MI (Fig. 5E). Treatments with siEGFR@LNP and ECM-siEGFR@LNP significantly decreased the fibrotic tissue area in comparison to MI control on both day 5 (Fig. 5F) and day 28 (Fig. 5G). Noticeably, ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment resulted in the smallest fibrotic area on day 5. Vascularization was analyzed in the border zone by labeling vessels with CD31 and α-SMA (Fig. 5H). ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatments showed higher ratios (Fig. 5I) and densities (Fig. 5J) of vasculatures at week 4 post-MI compared to other groups. Fibroblast activation in the infarct region was also examined (Fig. 5K). On day 5, siEGFR@LNP and ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatments reduced the density of myofibroblasts compared to MI control, with the siEGFR@LNP group demonstrating fewer myofibroblasts than the ECM treatment group (Fig. 5L). Similar effects were observed at week 4 (Fig. 5M). These findings indicate that ECM-siEGFR@LNP effectively promotes heart repair.

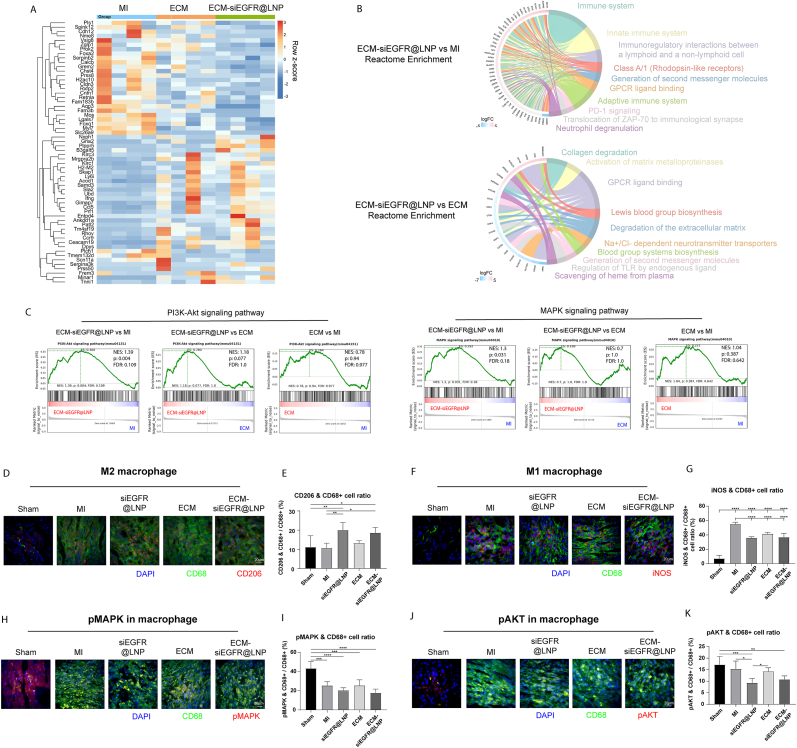

3.6. ECM-siEGFR@LNP affected AKT activity in macrophages

Signaling pathways affected by ECM-siEGFR@LNP were analyzed through mRNA sequencing on day 5 post-MI, revealing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Fig. 6A). Reactome analysis demonstrated that a large portion of DEGs between ECM-siEGFR@LNP and MI were related to the immune system, suggesting that EGFR interference modulates immune responses during the early stages of heart repair (Fig. 6B). Many DEGs between ECM-siEGFR@LNP and ECM were related to extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrosis. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to identify signaling pathways influenced by EGFR siRNA treatment, focusing on EGFR's known downstream effectors: Protein kinase B (AKT), Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), The signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR). ECM-siEGFR@LNP significantly increased the enrichment of genes associated with the PI3K-Akt and MAPK pathways compared to the MI control and ECM treatment (Fig. 6C), but not NF-κB, JAK-STAT, and PPAR pathways (Fig. S7A). These results suggest that ECM-siEGFR@LNP significantly modulates the activity of AKT and MAPK signaling pathways.

Fig. 6.

Transcriptome analysis of day 5 post-MI hearts. (A) The transcriptomic analysis identified the differentially expressed genes between the ECM-siEGFR@LNP and MI hearts. (B) According to Reactome analysis, several terms were associated with extracellular matrix remodeling in ECM-siEGFR@LNP versus ECM comparison. For ECM-siEGFR@LNP versus MI control, Reactome analysis revealed significant changes in immune response-related genes. (C) Genes related to the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways were modulated by ECM-siEGFR@LNP. (D) M2-like macrophages were identified by immunostaining for CD206 and CD68 in the infarct area on day 5 post-MI. (E) ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment significantly increased the ratio of M2-like macrophage compared to the MI control group. (F) M1-like macrophages were analyzed using immunostaining for iNOS and CD68. (G) siEGFR@LNP, ECM, and ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatments significantly reduced the ratio of M1-like macrophage compared to the MI control. (H) Phospho-MAPK-positive macrophages were assessed through immunostaining. (I) Less pMAPK + macrophages were observed in post-MI hearts than sham hearts. (J) Phospho-AKT + macrophages were examined. (K) ECM-siEGFR@LNP treatment lowered the ratio of pAKT + macrophage compared to sham. Notably, only siEGFR@LNP significantly reduced this ratio compared to the MI control. (n = 7. One-way ANOVA and Tukey's test applied. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.)

To validate the transcriptomic findings, macrophage polarization was first investigated. M2-like macrophages were labeled with CD206 and CD68 (Fig. 6D). ECM-siEGFR@LNP significantly increased the ratio of M2-like macrophages compared to MI control and sham groups (Fig. 6E). Pro-inflammatory M1-like macrophages were marked with iNOS and CD68 (Fig. 6F). All treatments (siEGFR@LNP, ECM, and ECM-siEGFR@LNP) reduced the ratio of M1-like macrophages in comparison to the MI control group (Fig. 6G). Next, MAPK and AKT phosphorylation in macrophages were evaluated. The ratio of phosphorylated-MAPK + macrophage was lower in post-MI hearts compared to sham (Fig. 6H and I). ECM-siEGFR@LNP group showed a decreased ratio of pAKT + macrophage compared to sham (Fig. 6J and K). These findings suggest that ECM-siEGFR@LNP suppresses AKT phosphorylation in macrophages and promotes M2 polarization during the inflammatory phase post-MI.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed a carboxyl-functionalized LNP that can be covalently linked to a hydrogel scaffold via EDC/NHS-mediated condensation. Bioactive molecules, such as mRNA and siRNA, can be encapsulated within these LNPs and delivered using the ECM-LNP composite. The ECM-LNP composite enhances LNP accumulation and prolongs mRNA expression following intramyocardial injection. We observed that delivering EGFR siRNA through the ECM-LNP composite preserved cardiac function and alleviated fibrosis. Previous research has demonstrated that LNP-gel composites can deliver LNPs, that cardiac ECM hydrogel promotes heart repair after MI, that the ErbB receptor family regulates fibrosis post-MI, and that EGFR influences macrophage activation [7,30,45,46]. However, to our knowledge, injectable platforms for precise and sustained LNP delivery into the heart and the therapeutic efficacy of EGFR siRNA for heart injury have not been reported. The hydrogel-LNP composite offers a promising solution to the challenge of low tissue specificity in mRNA therapy.

EGFR is a receptor for various extracellular ligands, including epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, and epiregulin [47]. Previous studies suggest that EGFR influences cardiomyocyte morphology and contractility. For instance, continuous infusion of EGFR antisense oligodeoxynucleotides reversed left ventricular hypertrophy in rats [48,49]. Furthermore, knocking down EGFR in cardiomyocytes resulted in cardiac contractile dysfunction in a mouse model [50]. These studies indicate that EGFR plays a role in regulating hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; however, its function in the response to myocardial injury remains unclear. Our findings suggest that reducing EGFR activity during the inflammatory stage after MI mitigates heart fibrosis. At the cellular level, interfering with EGFR expression reduced fibroblast activation and enhanced M2-like macrophage polarization. These observations align with reports of EGFR's inhibitory effects on M2 macrophage polarization in cancer and obesity models [51,52]. Furthermore, our results suggest that EGFR activity influences macrophage polarization in the injured heart through AKT signaling. Published works have shown that phosphorylated EGFR activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathways in cancer cells and cardiomyocytes [53,54]. Due to the complexity of the EGFR-AKT/MAPK network, its precise role in cardiac repair remains undetermined. For instance, while EGFR transactivation protects neonatal rat cardiomyocytes from apoptosis via AKT signaling, ligands-induced EGFR activation has also been associated with cardiac hypertrophy in adult mice [53,55]. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into how EGFR regulates macrophage function during the cardiac post-injury response, in addition to its role in cardiomyocytes.

As an alternative to the existing cardiac drug delivery platforms, the ECM-LNP composite offers a promising solution by enabling sustained RNA drug delivery over an extended period [56,57]. The composite rapidly polymerizes within 2 min after injection, which minimizes LNP displacement caused by heartbeats and circulation. As the ECM degrades, LNPs are gradually released, facilitated by the acidic environment of the infarcted heart that accelerates amide hydrolysis, leading to faster LNP release and targeted inflammation modulation. Currently, the ECM-LNP composite releases LNPs over approximately 14 days, with the majority being released within the first 4 days. Further modifications are needed to extend the release duration of LNPs, thereby improving the ECM-LNP composite's effectiveness in modulating heart regeneration and ventricular remodeling.

In addition to its role as a site-specific delivery platform, we demonstrated that the therapeutic efficacy of ECM hydrogel can be enhanced by incorporating specific drugs. In this study, the inclusion of EGFR siRNA in the ECM hydrogel showed a trend toward improving cardiac function compared to ECM hydrogel alone. This suggests that the therapeutic efficacy of the ECM-siEGFR@LNP composite could be further optimized by fine-tuning the dosage and release rate of the siRNA. Additionally, our findings indicate that EGFR siRNA effectively reduces heart fibrosis, highlighting its potential as a targeted therapy for extensive fibrosis.

High doses of LNPs can impact cell viability, as evidenced by abnormal cell morphology and reduced mRNA transfection efficiency observed at elevated LNP concentrations. Additionally, echocardiography measurements indicated that LNPs carrying negative control siRNAs slightly diminished the therapeutic efficacy of the ECM hydrogel. This side effect could potentially be mitigated by substituting the cationic lipids with ionizable lipids [58]. In addition to LNP dosage, the N/P ratio also affects the transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity. In our in vitro and in vivo experiments, an N/P ratio of 2.6 was employed. Both our results and previous reports indicate that an N/P ratio between 2 and 3 enables efficient mRNA delivery [[59], [60], [61]]. However, the optimal ratio may deviate from 2.6 because of the biphasic effects of N/P ratio on LNP size, mRNA copies per LNP, and frequencies of empty LNPs [62]. Previous studies have shown that increasing the N/P ratio enhances transfection efficiency, consistent with our findings [63,64]. Nevertheless, high N/P ratios have also been associated with adverse effects [65,66]. To identify the optimal N/P ratio, LNPs should be generated and evaluated at smaller incremental changes in N/P ratio, rather than large steps (e.g., a 10-fold change). In summary, the precise effects of N/P ratio and LNP dosage on RNA delivery efficiency and cytotoxicity require further investigation to guide the design of optimized LNPs for heart disease therapy.

In this study, the transfection efficiency in various cardiac cell types was likely below 30 %. Consistent with our observations, intramyocardial injection of GFP mRNA@LNP transfected less than 30 % of fibroblasts and endothelial cells according to microscopy measurements, and the transfection efficiencies were extremely low in cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle cells [67]. Despite this, modulating the behavior of even a small fraction of a specific cardiac cell type can significantly benefit heart regeneration. Increase the proportion of phospho-histone H3+ cardiomyocytes from ∼0.3 % to ∼0.5 % resulted in an approximately 50 % improvement in fractional shortening after MI [68], [69]. Additionally, increase the myofibroblast to fibroblast ratio from ∼12 % to ∼30 % enlarged the fibrotic area by ∼60 % after MI [70]. Therefore, we expect that targeting 10 % of leukocytes and fibroblasts could have a substantial therapeutic impact. Nevertheless, further enhancing transfection efficiency may improve the efficacy of siEGFR@LNP therapy.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed an ECM-LNP composite that integrates ECM hydrogel with covalently linked LNPs, providing a platform for precise and sustained delivery of LNPs to target organs. This composite allows for the encapsulation of various therapeutic agents, such as mRNA and siRNA. Using the ECM-LNP composite to deliver EGFR siRNA significantly enhanced cardiac repair following acute MI. The therapeutic effects were mediated by various cell types, including macrophages and fibroblasts, during the early stages of the injury response. Interfering with EGFR expression promoted macrophage M2 polarization by inhibiting AKT phosphorylation. These findings offer insight into the mechanisms of macrophage activation and response following MI.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xinming Wang: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yiming Zhong: Formal analysis, Data curation. Bei Qian: Methodology, Data curation. Shixing Huang: Methodology, Conceptualization. Qiang Long: Resources, Investigation. Haonan Zhang: Resources, Data curation. Qiang Zhao: Investigation, Funding acquisition. Xiaofeng Ye: Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve readability and language of the work. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Funding

This work was Sponsored by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1105100); National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (82125019); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82402485); Shanghai Pujiang Program (23PJ408200) from the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality, China; Faculty Investment Fund (RC20220018) from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine affiliated Ruijin Hospital; Chen Guang project (21CGA17) from Shanghai Municipal Education Commission and Shanghai Education Development Foundation; Youth Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82100264); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070429); National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Student Basic Research Project for Doctoral Students (823B2052); Program of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (202140184; 2022JC028); Program of Shanghai Academic (22S31905000; 201409005400); Shanghai Jiao Tong University medical engineering cross project (YG2022ZD002); Joint research project of Institute of Biomaterials and Regenerative Medicine, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (2022LHA10).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Xi Liu and Jingjing Cao in the Animal Imaging Facility at SJTU for assisting with echocardiography. We acknowledge the support of the staff in SJTU Electron Microscopy Center for SEM and TEM. We thank the Biocore in SJTU for microscopy imaging.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.102205.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kaptoge S., Pennells L., De Bacquer D., Cooney M.T., Kavousi M., Stevens G., Riley L.M., Savin S., Di Angelantonio E., et al. World Health organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health. Oct. 2019;7(10):e1332–e1345. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30318-3/ATTACHMENT/0BB4F97C-D682-49B9-9D58-A16B58C87155/MMC2.PDF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahit M.C., Kochar A., Granger C.B. Post-myocardial infarction heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. Mar. 2018;6(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/J.JCHF.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X., Shi H., Huang S., Zhang Y., He X., Long Q., Qian B., Zhong Y., Qi Z., Zhao Q., Ye X. Localized delivery of anti-inflammatory agents using extracellular matrix-nanostructured lipid carriers hydrogel promotes cardiac repair post-myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. Nov. 2023;302 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang D., Chen H., Zhao L., Zhang W., Hu J., Liu Z., Zhong P., Wang W., Wang J., Liang G. Inhibition of EGFR attenuates fibrosis and stellate cell activation in diet-induced model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. Jan. 2018;1864(1):133–142. doi: 10.1016/J.BBADIS.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkataraman T., Frieman M.B. The role of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in SARS coronavirus-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Antiviral Res. Jul. 2017;143:142–150. doi: 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao S., Pan Y., Terker A.S., Arroyo Ornelas J.P., Wang Y., Tang J., Niu A., Kar S.A., Jiang M., Luo W., Dong X., Fan X., Wang S., Wilson M.H., Fogo A., Zhang M.-Z., Harris R.C. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation is essential for kidney fibrosis development. Nat. Commun. Nov. 2023;14(1):7357. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43226-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X., Chen C., Ling C., Luo S., Xiong Z., Liu X., Liao C., Xie P., Liu Y., Zhang L., Chen Z., Liu Z., Tang J. EGFR tyrosine kinase activity and Rab GTPases coordinate EGFR trafficking to regulate macrophage activation in sepsis. Cell Death Dis. Nov. 2022;13(11):934. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05370-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia Q., Liu L., Yu Y., Wulamu W., Jia L., Liu B., Zheng H., Peng Z., Zhang X., Zhu R. Inhibition of EGFR pathway suppresses M1 macrophage polarization and osteoclastogenesis, mitigating titanium particle-induced bone resorption. J. Inflamm. Res. Nov. 2024;17:9725–9742. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S484529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dzau V.J., Hodgkinson C.P. RNA therapeutics for the cardiovascular System. Circulation. Feb. 2024;149(9):707–716. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.067373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheikh O., Yokota T. Developing DMD therapeutics: a review of the effectiveness of small molecules, stop-codon readthrough, dystrophin gene replacement, and exon-skipping therapies. Expet Opin. Invest. Drugs. Feb. 2021;30(2):167–176. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.1868434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W., Zhang X., Zhang C., Yan J., Hou X., Du S., Zeng C., Zhao W., Deng B., McComb D.W., Zhang Y., Kang D.D., Li J., Carson W.E., Dong Y. Biomimetic nanoparticles deliver mRNAs encoding costimulatory receptors and enhance T cell mediated cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. Dec. 2021;12(1):7264. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27434-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H., Jiang H., Xie W., Qian B., Long Q., Qi Z., Huang S., Zhong Y., Zhang Y., Chang L., Zhang J., Zhao Q., Wang X., Ye X. LNPs-mediated VEGF-C mRNA delivery promotes heart repair and attenuates inflammation by stimulating lymphangiogenesis post-myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. Nov. 2025;322 doi: 10.1016/J.BIOMATERIALS.2025.123410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson L., Clarke J.C., Yen C., Gregoire F., Albery T., Billger M., Egnell A.-C., Gan L.-M., Jennbacken K., Johansson E., Linhardt G., Martinsson S., Sadiq M.W., Witman N., Wang Q.-D., Chen C.-H., Wang Y.-P., Lin S., Ticho B., Hsieh P.C.H., Chien K.R., Fritsche-Danielson R. Biocompatible, purified VEGF-A mRNA improves cardiac function after Intracardiac Injection 1 week post-myocardial infarction in swine. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. Jun. 2018;9:330–346. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X., Zhang H., Xie W., Qian B., Huang S., Zhao Q., Ye X. Development of a decellularized extracellular matrix-derived wet adhesive for sustained drug delivery and enhanced wound healing. Mater. Today Bio. Jun. 2025;32 doi: 10.1016/J.MTBIO.2025.101734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawthorne D., Pannala A., Sandeman S., Lloyd A. Sustained and targeted delivery of hydrophilic drug compounds: a review of existing and novel technologies from bench to bedside. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. Dec. 2022;78 doi: 10.1016/J.JDDST.2022.103936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z., Long D.W., Huang Y., Chen W.C.W., Kim K., Wang Y. Decellularized neonatal cardiac extracellular matrix prevents widespread ventricular remodeling in adult mammals after myocardial infarction. Acta Biomater. Mar. 2019;87:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W.C.W., Wang Z., Missinato M.A., Park D.W., Long D.W., Liu H.-J., Zeng X., Yates N.A., Kim K., Wang Y. Decellularized zebrafish cardiac extracellular matrix induces mammalian heart regeneration. Sci. Adv. Nov. 2016;2(11) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Senapati S., Akinbote A., Gnanasambandam B., Park P.S.-H., Senyo S.E. Microenvironment stiffness requires decellularized cardiac extracellular matrix to promote heart regeneration in the neonatal mouse heart. Acta Biomater. Sep. 2020;113:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seif-Naraghi S.B., Singelyn J.M., Salvatore M.A., Osborn K.G., Wang J.J., Sampat U., Kwan O.L., Strachan G.M., Wong J., Schup-Magoffin P.J., Braden R.L., Bartels K., DeQuach J.A., Preul M., Kinsey A.M., DeMaria A.N., Dib N., Christman K.L. Safety and efficacy of an injectable extracellular matrix hydrogel for treating myocardial infarction. Sci. Transl. Med. Feb. 2013;5(173):173ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traverse J.H., Henry T.D., Dib N., Patel A.N., Pepine C., Schaer G.L., DeQuach J.A., Kinsey A.M., Chamberlin P., Christman K.L. First-in-Man study of a cardiac extracellular matrix hydrogel in early and late myocardial infarction patients. JACC Basic Transl Sci. Oct. 2019;4(6):659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams C., Quinn K.P., Georgakoudi I., Black L.D. Young developmental age cardiac extracellular matrix promotes the expansion of neonatal cardiomyocytes in vitro. Acta Biomater. Jan. 2014;10(1):194–204. doi: 10.1016/J.ACTBIO.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., Ansari A., Pierre V., Young K., Kothapalli C.R., von Recum H.A., Senyo S.E. Injectable extracellular matrix microparticles promote heart regeneration in mice with post‐ischemic heart injury. Adv Healthc Mater. Apr. 2022;11(8) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202102265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynn A.K., Yannas I.V., Bonfield W. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. Nov. 2004;71B(2):343–354. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palomino-Durand C., Pauthe E., Gand A. Fibronectin-enriched biomaterials, biofunctionalization, and proactivity: a review. Appl. Sci. Dec. 2021;11(24) doi: 10.3390/app112412111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong R., Talebian S., Mendes B.B., Wallace G., Langer R., Conde J., Shi J. Hydrogels for RNA delivery. Nat. Mater. Mar. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41563-023-01472-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desfrançois C., Auzély R., Texier I. Lipid nanoparticles and their hydrogel composites for drug delivery: a review. Pharmaceuticals. Nov. 2018;11(4):118. doi: 10.3390/ph11040118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]