Abstract

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is often underdiagnosed in Malaysia due to limited specialized training and validated screening tools. Although the McLean Screening Instrument for BPD (MSI-BPD) is a well-established measure, it lacks validation in Southeast Asia. This study evaluated the MSI-BPD’s psychometric properties in a Malaysian context.

Methods

Two samples, including a clinical sample of psychiatric outpatients (N = 101; mean age = 28.02 years; 74.3% female) and a healthy control group (N = 314; mean age = 29.75 years; 74.8% female), were recruited from a public hospital in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and a private university in Malaysia, respectively. Participants in the clinical sample completed the MSI-BPD along with other self-report psychological symptom measures, and BPD diagnoses were confirmed through a semi-structured clinical interview. Psychometric analyses were conducted on the clinical sample to assess the scale’s internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity, factor structure, and predictive validity concerning BPD diagnosis. Both the clinical and healthy control samples were included in a known-groups validity analysis to further evaluate the scale.

Results

The MSI-BPD exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) and convergent validity, as evidenced by significant correlations with related psychological symptoms. The scale also demonstrated good discriminant validity and predictive accuracy (area under the curve = 0.91), with an optimal cut-off score of 8. Confirmatory factor analyses supported a four-factor model (with factors identified being affective disturbances, impulsivity, unstable relationships, and disturbed cognition) as the best fit among the five evaluated models. The study also established the known-groups validity of the MSI-BPD, demonstrating its ability to distinguish clinical samples from healthy controls, with clinical participants scoring significantly higher than controls.

Conclusions

The MSI-BPD is a valid and reliable tool for screening BPD in Malaysia. The findings enhance our understanding of BPD’s construct validity and factor structure in Southeast Asia, which leads to a more universal and cross-cultural understanding of BPD. Validating the screening instrument is crucial for improving mental health assessments and interventions, as well as strategies to better identify individuals at-risk for BPD for early intervention optimizing outcomes in a low-resource Southeast Asian context.

Keywords: Borderline personality disorder, McLean screening instrument for BPD, Psychometric validation, Psychiatric outpatients

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a psychological disorder featuring dysregulations in emotions, behaviors, interpersonal relationships, and cognition [2]. The disorder is frequently co-morbid with other mental disorders, such as anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder [3]. If left untreated, high levels of BPD symptoms can adversely impact quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and are associated with higher healthcare utilization [4]. Treating BPD presents challenges, given the disorder’s association with high suicide risk [5] and high incidence of self-harm behaviors [6].

The global prevalence rates of BPD traits have been estimated to range from 0.7 to 3.9% in adults, and 3–14% among adolescents and children [7]. The burden of psychiatric service utilization in BPD populations is significant, with up to 65% of in- and out-patients worldwide meeting BPD’s diagnostic criteria [7]. Contrary to the assumption that BPD is less prevalent in non-Western cultures, these authors did not identify significant differences in BPD prevalence rates between Western and non-Western countries. Notably, epidemiological data on the prevalence of BPD in low-and middle-income countries, especially in the Southeast Asian region is relatively scarce. In Malaysia, few studies have systematically investigated the prevalence of BPD in community or clinical settings. Studies using convenience sampling have identified the prevalence of BPD to be 2.9% in a forensic setting [8], and 14% in a tertiary general hospital [9]. In clinical settings, BPD is frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, largely due to limited specialized training among clinicians in its assessment and treatment. High comorbidity rates with disorders such as bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, excessive shame and stigma, and clinical presentation heterogeneity preclude straightforward diagnosis of BPD across all developmental stages [10]. Additionally, the absence of locally validated screening tools for BPD further complicates accurate diagnosis, making it challenging to provide tailored care. This gap in diagnosis and treatment has broader implications for public health, as it affects the effectiveness and accessibility of mental health services for individuals with BPD.

Within the broader literature, several measures are available to assess and screen for symptoms of BPD in clinical and research settings. Examples of these measures include the McLean Screening Instrument for BPD (MSI-BPD; [11], the Personality Assessment Inventory- Borderline Subscale [12], and the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4th edition—BPD Scale [13]. Of these measures, the MSI-BPD is among the most commonly used due to the scale’s brevity and availability in the public domain. In particular, the scale consists of ten self-report items with dichotomous answer options, making it easily administrable. The scale’s psychometric properties have been examined in several populations, ranging from psychiatric outpatients [14], community adults [15], adolescents [16], and college students [17]. The MSI-BPD has also been translated into multiple languages such as Dutch [18], Persian [19], Chinese [20], Urdu [21], to name a few.

Geographically, the majority of studies assessing the validity of the MSI-BPD were carried out in North America, Europe, and selected regions of Asia, and few studies have validated its use in the Southeast Asian context. In a study based in Singapore, the MSI-BPD demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity in a psychiatric outpatient sample [22]. The scale also demonstrated predictive validity, with a cut-off score of 7 corresponding to moderate-to-high sensitivity and specificity in predicting the diagnosis of BPD. In Malaysia, a study by Nurul Hazrina and Affizal [23] validated a Malay-translated version of the MSI-BPD among female prisoners, and found that the translated scale had moderate internal consistency and high test-retest reliability. The study however did not assess the scale’s predictive utility with regards to the diagnosis of BPD. To date, no research has yet assessed MSI-BPD’s psychometric properties and diagnostic utility among psychiatric outpatients in Malaysia.

As highlighted earlier, BPD is a disorder consisting of dysregulation across several domains, with a total of nine symptom criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) [2]. Symptoms of BPD are heterogeneous; for example, some of the symptoms pertain to emotional lability and maladaptive expression (i.e., inappropriate expression of anger); whereas others relate to cognitive dysregulation (e.g., identity instability and stress-related paranoia or dissociation). With a minimum of five positive symptoms being the threshold for diagnosis, there are 256 possible ways one could meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder [24]. Given the heterogeneity of BPD’s symptomatology, it is of value to examine core dimensions that underlie BPD’s symptom presentations.

Much research has examined BPD’s factor structures, and studies have generated differential factor models, ranging from one-factor models to four-factor models [1, 20]. A study involving community adults and students based in the United Kingdom found support for a one-factor model of BPD [25]. Another study by Sanislow et al. [26], which involved a sample of treatment-seeking adults in the United States, revealed a three-factor model of BPD consisting of affective dysregulation, disturbed relatedness, and behavioral dysregulation. Lastly, Lieb et al. [1] proposed a four-factor model of BPD that consists of affective disturbances, impulsivity, unstable relationships, and disturbed cognition. The four-factor structure was supported in a study involving a sample of community adults based in the United States, and the factor structure was found to be consistent across subgroups of Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic participants [27].

Even though culture is known to influence symptom presentations of psychological disorders [28, 29], the extent to which components or core dimensions of BPD vary across cultural contexts remains under-researched. To date, relatively less work has examined the presentation and factor structure of BPD in Asia, compared to North American or European contexts. In Asia, several studies have examined the factor structure of MSI-BPD in different samples, providing varying support for the different factor models [19–23, 30, 31]. In particular, one study evaluated the factorial validity of an Urdu version of the MSI-BPD in a sample of Pakistani patients with cardiac problems and found support for a one-factor model [21]. Another study, involving a sample of over 200 Iranian male soldiers, translated the MSI-BPD into Persian and found that the data fit both one-factor and two-factor models [19].

In East Asia, several studies based in China have established MSI-BPD’s factor structures. Leung and Leung [20] recruited over 4000 adolescents based in Hong Kong and found support for a four-factor model of BPD, with the factors consisting of affect dysregulation, interpersonal disturbances, impulsivity, and cognitive disturbances. Chen et al. [30] and Wang et al. [31] each examined MSI-BPD’s factorial validity in samples of Chinese college students and psychiatric patients, respectively, and both found support for a four-factor model. In sum, the findings indicate that a four-factor model may be the best fit for ethnic Chinese based in Asia. In Southeast Asia, a study by Keng et al. [22] involving two samples of Singaporean psychiatric patients and college students, found support for a three-factor model of BPD consisting of affect dysregulation, self-disturbances, and behavioral and interpersonal dysregulation. Lastly, a study by Nurul Hazrina and Affizal [23] validated a Malay-translated version of MSI-BPD in a sample of female prisoners in Malaysia and identified a four-factor solution for the measure.

Study aims

The present study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of MSI-BPD (internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity, and factor structure), establish a cut-off score that has the best sensitivity and specificity for BPD diagnosis, and assess the prevalence rate of BPD using a convenience sample of psychiatric patients in a public hospital in Malaysia. Drawing from prior research, we assessed several competing models of MSI-BPD’s factor structure: Gardner & Qualter’s [25] one-factor model, Keng et al.’s [22] three-factor model, Sanislow et al.’s [26] three-factor model, Leung and Leung [20]’s four-factor model, and Lieb et al.’s [1] four-factor model to identify the best-fitting factor structure for the clinical sample.

Further, the study aimed to establish MSI-BPD’s known-groups validity by comparing scores on the measure between the clinical sample and a healthy control group recruited from a different study. Known-groups validity refers to the ability of a measure to distinguish between groups that are theoretically expected to differ based on the construct being measured [32]. Despite extensive use of the MSI-BPD across clinical and research settings, few studies have directly assessed its known-groups validity. Addressing this gap is critical for assessing the instrument’s ability to accurately distinguish between psychiatric patients versus nonclinical individuals.

Methods

Participants

The clinical sample consisted of 101 patients who were recruited from a psychiatric outpatient unit in a public hospital in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Recruitment was carried out via convenience sampling, through posting of fliers in the psychiatry outpatient unit and direct referrals by psychiatrists. The study’s inclusion criteria were: 1) a current patient at the psychiatric clinic, 2) aged between 18 and 60 years, and 3) able to read and write English. The following were the study’s exclusion criteria: 1) experiencing persistent, active manic or psychotic symptoms, 2) being diagnosed with an intellectual disability or an organic brain disorder, and 3) presenting with imminent suicide risk during intake assessment. Sample size calculation indicated that a minimum of 100 participants would be required, based on the recommended 10:1 subject-to-item ratio [33, 34]. This study received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2019-495) of the National University of Malaysia.

The healthy control sample consisted of adults recruited from a parent study called Project INSPIRE (“Investigating Neurocognitive and Social Personality Influences on Regulation of Emotion”), a cross-sectional study investigating psychological and neurocognitive correlates of emotion regulation in a community sample in Malaysia. Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling approach, primarily from a university campus, and more broadly through social media to reach the wider community. Participants were eligible for the parent study if they were aged 18 and above, resided in Malaysia, were regular users of smartphones or a computer, and had regular Internet access. Data from a subset of the recruited participants (N = 314) who reported no current psychiatric diagnosis were included in the present study’s analyses. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Sunway University (Approval Number: SUREC 2024/093).

Procedure

All participants across both studies gave informed consent before participating in the study. For the clinical sample, eligible participants were invited to attend an assessment session consisting of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-BPD) interview and a battery of questionnaires assessing borderline symptoms, anxiety, depression, stress, identity disturbance, emotion regulation difficulties, impulsivity, and interpersonal difficulties (see Measures section). Assessors conducting the SCID-BPD interview were blind to the participants’ diagnostic status and/or participants’ self-report data based on the measures. Both assessors were Master of Clinical Psychology trainees who received training from the Principal Investigator in the administration of SCID-BPD. Information regarding participants’ pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses was retrieved from their medical records following completion of the assessment session. Each participant received RM50 (approximately US$11) for their participation in the study.

With regards to the study involving healthy control participants, participants completed an online battery of self-report measures assessing their demographic characteristics, BPD symptoms (using the MSI-BPD), and other personality and mental health outcomes. Each participant was paid RM5 (approximately US$1.10) e-voucher for completing the 20-minute survey. For this study, only data pertaining to participants’ demographic information and MSI-BPD scores were included in the analyses.

Measures

Clinical sample

Demographic information form

The study administered a demographic information form inquiring participants’ gender, ethnicity, age, relationship status, treatment history, and status of employment.

McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD; [11])

The MSI-BPD is a rating scale comprising ten dichotomous items corresponding with BPD’s DSM diagnostic criteria [2]. The original scale (in English) was administered in this study. A score of 7 or more has been suggested by past research as the clinical cut-off for a likely BPD diagnosis [11]. The measure demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity in a sample of American community adults [11].

Personality assessment Inventory – Borderline features scale (PAI-BOR; [35])

The PAI-BOR is a self-report questionnaire measuring symptoms of BPD. The scale consists of 24 items making up four subscales, namely identity problems, affective instability, self-harm, and negative relationships. Each item is rated on a four-point scale, ranging from 0 (false, not true at all) to 3 (very true). The scale demonstrated good criterion and concurrent validity in a sample of BPD patients in the United States [36]. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

Patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; [37])

The PHQ-9 was administered to assess depressive symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks. Items are rated on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Higher scores reflect greater severity of depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 demonstrated good internal reliability and validity in a psychiatric sample in the United States [38]. In this sample, the scale showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Depression anxiety and stress scales (DASS-21; [39])

The DASS-21 is a well-validated measure that assesses depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms in the past week. Only the Anxiety and Stress subscales from the DASS-21 were administered in this study. All items are rated on a four-point Likert scale. The internal reliability for the anxiety subscale and the stress subscale was 0.87 and 0.90 respectively, in this study’s sample.

Barratt impulsiveness Scale- short form (BIS-15-SF; [40])

The BIS-SF was administered as a measure of trait impulsivity. The measure is composed of 15 items rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (rarely/never) to 4 (almost always). The scale has good internal consistency in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Difficulties with emotion regulation Scale- short form (DERS-SF; [41])

The DERS-SF was administered to assess the extent of emotional dysregulation experienced by participants. The measure comprised 18 items rated on a five-point scale (1 [Almost Never] to 5 [Almost Always]). The measure has demonstrated high correlations (r =.91 −.98) with the original, 36-item DERS [42]. The scale showed high internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Rosenberg’s stability of self scale (RSOS; [43])

The RSOS assesses the extent of instability one experiences in relation to one’s self-image. The scale includes five items that are rated on a four-point scale, with higher scores reflecting greater instability of self-concept. Results from a meta-analysis indicate that the scale has high convergent validity and test-retest reliability [44]. The scale’s internal consistency was 0.74 in the present sample.

Inventory of interpersonal Problems – Personality disorder scales (IIP-PD-25; [45])

The IIP-PD-25 is a self-report scale that assesses interpersonal difficulties experienced by individuals with personality disorders. The scale consists of 25 items that are rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 [not at all distressing] to 4 [extremely distressing]). The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

State-Trait anger expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2; [46])

The STAXI-2 is a 25-item scale that assesses the frequency of anger expression, suppression of anger, and control of expression of anger. It has demonstrated high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity in clinical and research settings [46]. Participants rate each item on a four-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). In this sample, the scale’s internal consistency was 0.78.

Big five inventory (BFI; [47])

Two subscales of the BFI were administered to assess extraversion (eight items) and openness to experience (ten items). Given that both personality facets are not expected to be associated with BPD symptoms, these subscales were administered to assess MSI-BPD’s discriminant validity. The scale’s items are rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this sample, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.76 and 0.66 for extraversion and openness, respectively.

BPD module of the structured clinical interview for axis II personality disorders (SCID-BPD; [48])

The SCID-BPD is a semi-structured clinical interview used to diagnose BPD. Past studies have demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability for the interview [49, 50]. In this study, two study interviewers completed independent ratings for 10% of all participants to assess the interview instrument’s inter-rater reliability. Analyses yielded high intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC = 0.97; using absolute agreement definition) for all SCID-BPD item scores.

Healthy control sample

The study involving the healthy control sample also administered a demographic data form. The form consisted of items inquiring participants’ gender, ethnicity, age, relationship status, psychiatric status, and status of employment. Only participants reporting no current psychiatric diagnosis (n = 314, out of 348 recruited participants) were included in the present study’s analysis of MSI-BPD’s known-groups validity. The MSI-BPD was also administered in this study, with known features of the scale having been described in the section above.

Data analyses

Data analyses were carried out using SPSS version 27 and AMOS 26. Descriptive statistics were conducted to characterize the samples. Psychometric analyses were conducted on the clinical sample to assess the scale’s internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity, factor structure, and predictive validity concerning BPD diagnosis. To examine MSI-BPD’s convergent and discriminant validity, we performed correlational analyses to examine the association between MSI-BPD scores and measures of psychological symptoms (BPD symptoms, depression, and anxiety), interpersonal difficulties, anger expression, impulsivity, stability of self-image, openness to experience, and extraversion. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which MSI-BPD’s total scores could accurately predict participants’ SCID-II BPD diagnosis. MSI-BPD’s overall diagnostic accuracy was determined using Area Under the ROC-curve (AUC).

Subsequently, we performed a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to evaluate the extent to which the data fit the following models established in prior literature: [1] Gardner and Qualter [25]’s one-factor model [2], Sanislow et al.’s [26] three-factor model [3], Keng et al.’s [22] three-factor model [4], Lieb et al.’s [1] four-factor model, and [5] Leung and Leung [20]’s four-factor model. Table 1 outlines the models of BPD that are subjected to CFA with maximum likelihood estimation. Conventional literature suggests the use of weighted least square when data are not normally distributed; however, later findings have shown that maximum likelihood remains robust when processing the same kind of data [51]. Maximum likelihood tends to be more stable overall and shows higher accuracy regarding both empirical and theoretical fit compared to other estimators [51], as commonly reported in previous MSI-BPD validation studies [19, 21]. Multiple goodness-of-fit indexes were used to evaluate the MSI-BPD competing models: Ratio of Chi-Square to the Degrees of Freedom (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). A χ2/df ratio of less than 2 represents a good model fit [52]. CFI, TLI, and IFI values of 0.90 or above reflect a good fit [53]. RMSEA values less than 0.05 are described as good, values between 0.05 and 0.08 as acceptable, values between 0.08 and 0.1 as marginal, and values greater than 0.1 as poor [54].

Table 1.

Models of BPD subject to confirmatory factor analyses

| Models of BPD | Factors |

|---|---|

| Gardner & Qualter (2009)’s One-Factor Model | NA |

| Sanislow et al. (2002)’s Three-Factor Model |

(1) Affective dysregulation (affective instability, inappropriate anger, and efforts to avoid abandonment) (2) Disturbed relatedness (unstable relationships, identity disturbance, and chronic emptiness) (3) Behavioral dysregulation (impulsivity and suicidal/self-mutilative behavior) |

| Keng et al. (2018)’s Three-Factor Model* |

(1) Affective dysregulation (affective instability, anger dyscontrol) (2) Self-disturbances (identity disturbance, dissociative symptoms) (3) Behavioral and interpersonal dysregulation (impulsive behaviors, self-mutilation/suicide, unstable relationships, abandonment fear, paranoid ideation) |

| Lieb et al. (2004)’s Four-Factor Model |

(1) Affective disturbances (affective instability, inappropriate anger, chronic emptiness) (2) Impulsivity (impulsive acts, self-mutilating or suicidal behaviors) (3) Unstable relationships (unstable relationships, fear of abandonment) (4) Disturbed cognition (identity disturbances, dissociative/psychotic symptoms) |

| Leung & Leung (2009)’s Four-Factor Model |

(1) Affective dysregulation (affective instability, anger dyscontrol) (2) Impulsivity (impulsive acts, self-mutilating or suicidal behaviors) (3) Interpersonal disturbances (unstable relationships, abandonment fear, paranoid ideation) (4) Self/cognitive disturbances (chronic emptiness, identity disturbances, dissociative symptoms) |

*Chronic emptiness was excluded from Keng et al. (2018) ’s three-factor BPD model due to a lack of fit between the item and the established model. Specifically, inclusion of this item in the model resulted in inadmissible solutions

To evaluate the known-groups validity of the MSI-BPD, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted with group condition (clinical vs. healthy control participants) as the independent variable. Age, and gender, and ethnicity (with Malay as the reference group) were included as covariates to control for their potential confounding effects [55]. The analysis assessed whether MSI-BPD scores differed significantly between the two groups, with clinical participants expected to score significantly higher than healthy control participants.

Results

Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics

Clinical sample

The sample’s average age was 28.02 years (range = 19–67 years old). Out of 101 participants, 74.3% of participants (74.3%) identified as female. The majority of participants were Malay (n = 72; 71.3%), followed by Chinese (n = 23; 22.8%), Indian (n = 2; 2%), and others. Most of the participants were single or never married (n = 69; 68.3%), whereas others were married or in an intimate relationship (n = 29; 28.7%) or separated or divorced (n = 9; 8.9%). In terms of the highest level of education achieved, the sample consisted of participants who completed a bachelor’s degree or above (n = 42; 41.6%), did not finish university or were current students (n = 14; 13.9%), and completed diplomas or pre-university certificates (n = 32; 31.7%). The remaining participants completed primary school or secondary school (n = 13; 12.9%). In addition, more than half of the participants were not employed (n = 60; 59.4%), while the remaining had either a full-time job (n = 27; 26.7%) or a part-time job (n = 14; 13.9%).

With regards to the diagnosis of BPD as established by the SCID-BPD interview, 44.6% (n = 45) of the participants met the diagnostic criteria for BPD. Meanwhile, a review of participants’ medical charts indicated that 34.7% (n = 35) of participants were diagnosed with BPD by their attending psychiatrists. Further information regarding participants’ diagnoses derived from their medical charts is presented in Table 2. We further examined inter-source concordance between chart-recorded BPD diagnosis and SCID-II interview diagnoses in a subsample of 98 participants, after excluding cases were chart data was not retrievable (n = 3). Chart diagnoses were coded as BPD-positive or negative, and compared against SCID-established results. Overall agreement was 80%, with a Cohen’s κ of 0.58, 95% CI [0.42–0.74], reflecting moderate concordance.

Table 2.

Diagnoses derived from participants’ medical records

| Diagnosis | n |

|---|---|

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 35 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 43 |

| Bipolar Disorder (I and II) | 28 |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | 5 |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 7 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 2 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 1 |

| Panic Disorder | 2 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 2 |

| Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | 2 |

| Schizophrenia | 2 |

| Schizoaffective Disorder | 1 |

| Adjustment disorder | 1 |

| Trichotillomania | 1 |

| Diagnosis not retrievable/not included on record | 7 |

Healthy control sample

The healthy control sample consisted of 314 individuals aged 18 to 71 years, with a mean age of 29.75 years (SD = 12.89). The majority of participants were female (74.8%), with males comprising 24.8%, and one individual identifying as “Other” (0.3%). Ethnic representation included predominantly Chinese participants (62.4%), followed by Malays (20.4%), Indians (10.8%), and others (6.4%). Regarding relationship status, most participants were single (57.0%), with others being in a relationship (21.0%), married (20.1%), or separated/other (2.0%). In terms of education, nearly half of the participants had a bachelor’s degree (48.7%), while others held postgraduate qualifications (19.7%), diplomas (16.6%), or secondary education (15.0%). Approximately half of the sample was unemployed (52.2%), followed by those in full-time employment (37.6%) and part-time employment (10.2%).

Internal consistency

The MSI-BPD demonstrated good internal consistency in the clinical sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) and the healthy control sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.84).

Convergent and discriminant validity

In the clinical sample, the MSI-BPD showed good convergent validity, with the total score correlating significantly and in expected directions with borderline symptoms, depression, stress, anxiety, impulsivity, emotion regulation difficulties, anger expression, instability of self-concept, and interpersonal difficulties (rs ranging from 0.56 to 0.85; all ps < 0.001). The scale also demonstrated discriminant validity, as the total score was not correlated with openness or extraversion. Table 3 presents the results from these analyses.

Table 3.

Correlations between MSI-BPD and other study measures

| MSI-BPD | |

|---|---|

| PAI-BOR | 0.849*** |

| BIS | 0.593*** |

| DERS-SF | 0.640*** |

| RSOS | 0.559*** |

| IIP-PD | 0.631*** |

| STAXI | 0.593*** |

| PHQ9 | 0.581*** |

| DASS-A | 0.647*** |

| DASS-S | 0.676*** |

| BFI-EX | − 0.007 |

| BFI-OP | 0.051 |

***p <.001, two-tailed. MSI-BPD = McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder; PAI-BOR = Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Scale; BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale- Short Form; DERS-SF = Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale- Short Form; RSOS = Rosenberg’s Stability of Self Scale; IIP-PD = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems – Personality Disorder Scales; STAXI = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2; PHQ9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; DASS-A = Anxiety Subscale of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales; DASS-A = Stress Subscale of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales; BFI-EX = Extraversion Scale of the Big Five Inventory (BFI); BFI-OP = Openness to Experience Scale of the BFI

Predictive validity

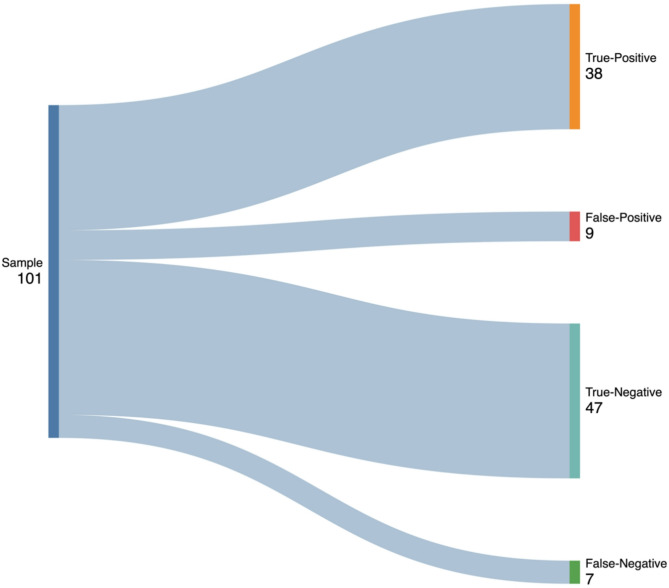

The performance of the MSI-BPD was compared against the diagnosis of BPD as determined by the SCID-II in the clinical sample. There were 38 true-positives, 9 false-positives, 47 true-negatives, and 7 false-negatives (see Fig. 1). At a cut-off score of 8 or above, the sensitivity of the MSI-BPD was 0.84, and the specificity was 0.84. In other words, the cut-off score allows the scale to correctly identify 84% of patients with BPD and 84% of patients without BPD. The AUC was 0.91 (95% CI [0.85, 0.96]). To further evaluate the predictive validity of the MSI-BPD for diagnosing BPD, we calculated the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) with a cut-off score of 8 on the MSI-BPD. The results showed that the MSI-BPD has a PPV of 0.81, indicating that 81% of participants scoring 8 or higher were correctly identified as having BPD according to the SCID-BPD diagnosis. The NPV of 0.87 indicates that 87% of participants scoring below 8 were correctly identified as not having BPD.

Fig. 1.

Sankey Diagram for MSI-BPD’s True-Positive, False-Positive, True-Negative, and False-Negative as Determined by SCID-BPD Diagnosis. Classification outcomes of the MSI-BPD screening tool against the SCID-II in the clinical sample. Sankey diagram created using the open-source, online tool SankeyMATIC (sankeymatic.com); path thickness is proportional to the number of participants in each classification category; x-axis reflects the diagnostic pathway from screening to confirmed diagnostic status; colors are for visual distinction only

Factor structure

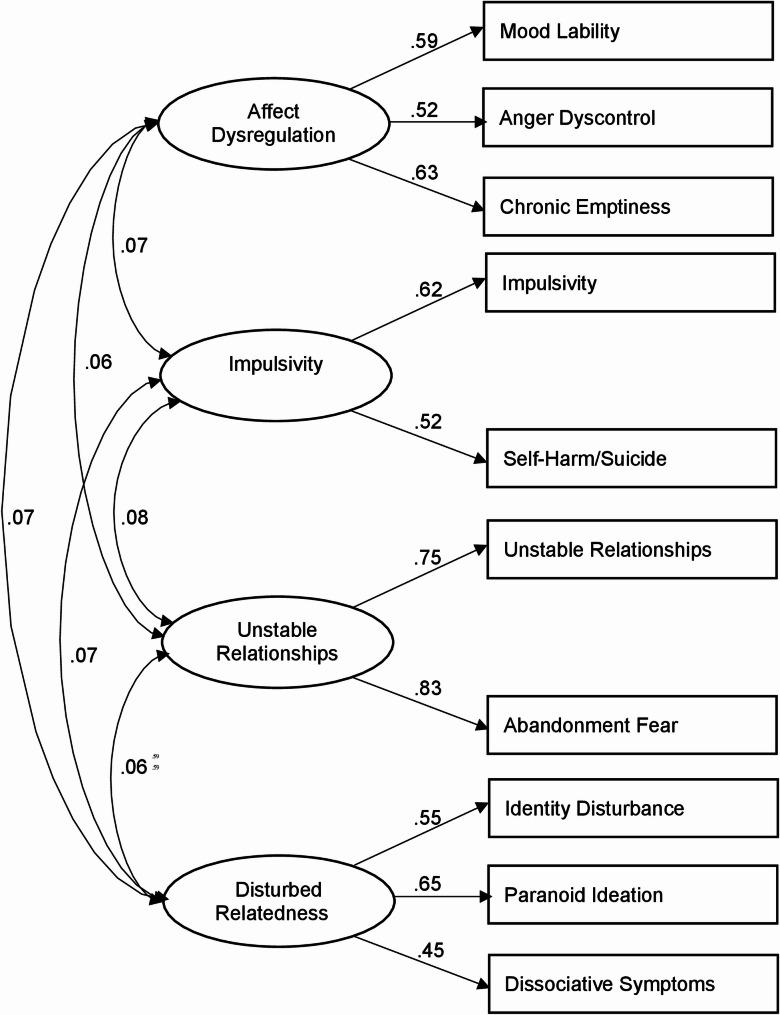

Table 4 presents model fit indices for each competing model in the clinical sample. For the fit indices reported in Table 4, CFI, TLI, and IFI values closer to 1.00 reflect a better-fitting model. Such values were largest for Lieb et al.’s [1] four-factor model when compared to the other competing models in the analysis. The χ2/df ratio was smallest for the Lieb et al.’s (2004) four-factor model. The superiority of Lieb et al.’s (2004) four-factor model over other models was also supported by RMSEA. The RMSEA was lower for the Lieb et al.’s [1] four-factor model than for other competing models. Taking all indices into consideration, Lieb et al.’s [1] four-factor model is the best-fitting model among the competing models. Figure 2 indicates the factor loadings and covariances for Lieb et al.’s [1] four-factor model. All parameters were significant at ps < 0.01.

Table 4.

Model fit indices of the MSI-BPD

| Fit Indices | Gardner & Qualter (2009) | Sanislow et al. (2002) | Keng et al. (2018) | Lieb et al. (2004) | Leung & Leung (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio of χ2 to df | 1.97 | 2.11 | 2.05 | 1.55 | 1.97 |

| Comparative Fit Index | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.88 |

| Tucker-Lewis Fit Index | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.82 |

| Incremental Fit Index | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

MSI-BPD = McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder

Fig. 2.

Factor Loadings and Covariances for Lieb et al.’s (2004) Four-Factor Model. All parameters were significant at ps < 0.01

Known-Groups validity

An ANCOVA was conducted to evaluate the known-groups validity of the MSI-BPD by comparing scores between clinical and healthy control participants, while controlling for age, gender, and ethnicity (with Malay as the reference category). The model revealed a significant main effect of condition, F(1, 408) = 93.27, p <.001, partial η² = 0.19, indicating that clinical participants scored significantly higher on the MSI-BPD than healthy controls. Estimated marginal means showed that the clinical group (M = 6.32, SE = 0.29, 95% CI [5.75, 6.89]) scored significantly higher than the healthy control group (M = 3.04, SE = 0.16, 95% CI [2.73, 3.34]), providing evidence for the known-groups validity of the MSI-BPD.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the psychometric properties and factorial validity of the MSI-BPD in a sample of Malaysian psychiatric outpatients. Results indicated that the MSI-BPD provides a reliable measurement of BPD symptoms (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). The scale also demonstrated convergent validity, as evidenced by significant, moderate-to-large correlations with BPD symptoms (as measured by PAI-BOR, another established measure), depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, difficulties with emotion regulation, impulsivity, anger expression, instability of self-concept, and interpersonal difficulties. These findings correspond with those of past studies demonstrating BPD’s association with symptoms of emotional lability [56], intense anger [57], impulsivity [58]and poor relationship satisfaction [59]. The measure was not correlated with openness and extraversion, indicating its discriminant validity. Results of CFA showed that Lieb et al. [1]’s four-factor model was the best fit among several competing models that were evaluated. The four factors are: (a) affective disturbances (emotional instability, inappropriate anger, persistent emptiness), (b) impulsivity (impulsive, self-harm or suicidal behaviors), (c) unstable relationships (stormy relationships, fear of abandonment), and (d) disturbed cognition (dissociative/psychotic symptoms, disturbance of identity). The finding is consistent with that of Leung and Leung [20] and Chen et al. [30], who also established a four-factor structure for the measure in a sample of adolescents based in Hong Kong and a sample of psychiatric patients based in mainland China, respectively. It is noteworthy that the factor solution differs from that of a study involving a Singaporean sample, which identified a three-factor solution (in which behavioral and interpersonal dysregulation merged into one factor) for the MSI-BPD [22]. The findings suggest that in the current sample of Malaysian psychiatric patients, disturbances in the behavioral and interpersonal domains can be conceptualized as distinct problem domains, as originally proposed by Lieb et al. [1]. Together, the generalizability of the four-factor model to Malaysian psychiatric outpatients implies that the key attributes of BPD may hold constantly across cultures. Nonetheless, it also calls for more investigation into how specific factors, such as affect lability and conflictual relationships, might present differently or be more prominent in Malaysian clients relative to Western counterparts. Future research should test whether variations might indicate distinct cultural values and patterns in emotion regulation and interpersonal relationship dynamics.

The present study established a cut-off score of 8 for the MSI-BPD. At this cut-off score and above, the scale demonstrates the best balance of sensitivity and specificity (0.84 each) for detecting potential BPD diagnosis against the DSM-5 criteria. Notably, the cut-off score is higher than that (i.e., 7 and above) established in several other studies [11, 14, 15], but is comparable to Chanen et al. [60] and Kröger et al. [61] which also established a similar cut-off score of 8 based on a child and adolescent outpatient sample in Australia and an outpatient adult sample in Germany respectively. Based on the derived PPV, a score of 8 or above on the MSI-BPD indicates that there is an 81% chance one would be diagnosed as having BPD. It is possible that mental health stigma in Malaysia may lead participants to underreport certain symptoms (e.g., suicidal ideation, emotional instability) [9]. A higher cut-off score compensates for this underreporting while maintaining diagnostic sensitivity.

The findings provide evidence for the known-groups validity of the MSI-BPD, as the scale successfully distinguished between the clinical sample and the healthy control group, with clinical participants scoring significantly higher on the scale. This demonstrates the scale’s ability to differentiate individuals with psychiatric symptoms from nonclinical populations. Notably, this is the first study to report the known-groups validity of the MSI-BPD, addressing a critical gap in the literature. The prevalence rate of BPD (established based on SCID-BPD diagnosis) in the present study (44.6%) is similar to, or higher than prevalence rates established in other studies based in Southeast Asia. In a study involving psychiatric outpatients in Singapore, the prevalence rate of BPD was 36% [22]. Another study involving a sample of female prisoners in Malaysia identified 17.8% of participants as screening positively for BPD [23]. Notably, the present study recruited a convenience sample, and the elevated prevalence rates (i.e., 34.7% prevalence established by chart-diagnosis; 44.6% prevalence established by SCID-interview) may be attributable to referral bias, as several co-investigators of the study (HMSS, LFC, LSCW, CLE) were psychiatrists who referred their own patients to the study. These co-investigators were aware that the study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the MSI-BPD, which may have influenced their likelihood of referring patients with BPD traits.

Beyond referral bias, other factors may contribute to the elevated prevalence rate of BPD. Future research comparing the prevalence of BPD diagnosis in our study participants with a broader psychiatry outpatient sample in Malaysia (ideally randomly selected) would yield valuable insights regarding the prevalence of BPD diagnosis in outpatient settings, as well as enable more systematic investigation into factors affecting higher versus lower prevalences rate in this setting.

This study is the first to evaluate MSI-BPD’s psychometric properties in a psychiatric outpatient setting in Malaysia. Administration of SCID-BPD interviews by trained assessors who were blind to participants’ diagnostic status allows for an objective assessment of MSI-BPD’s predictive validity with regard to the presence of a BPD diagnosis. The use of CFA enables the examination of theoretically derived clusters of BPD symptoms based on several competing models. Meanwhile, there are a few limitations to this study. First, the sample was drawn from a clinical setting in a large city in Malaysia, and the results may not be generalizable to the general public and other non-urban settings in Malaysia. Further, the sample size was relatively small, even though the sample recruited adheres to the subject-to-variables ratio recommended by Velicer and Fava [33]. Future studies should replicate the findings with a larger clinical sample. The majority of measures used in the study were self-report measures, which are subject to recall bias. Additionally, the established correlations may be inflated by common method bias. Lastly, there was a discrepancy in terms of ethnic composition between the clinical sample and healthy control sample, with the former sample consisting of a higher proportion of Malay participants. This difference in ethnic composition reflects broader patterns of healthcare utilization and accessibility in Malaysia, where public hospitals generally serve an often more Malay-majority population, while private universities and their surrounding communities may have a higher representation of Chinese students. To address the issue of ethnicity as a potential confounding factor in establishing MSI-BPD’s known-groups validity, we controlled for ethnicity as a covariate in our analyses. Overall, in spite of these limitations, the current study contributes to the growing body of evidence on the usage of MSI-BPD as an effective screening instrument for BPD.

Conclusion

In summary, this study showed that MSI-BPD is a reliable and valid tool for screening BPD in a psychiatric setting in Malaysia. Factor analysis showed that Lieb et al. [1]’s four-factor model provided the best fit for the data. The findings deepen our understanding of BPD’s construct validity in Southeast Asia and highlight the need for locally validated diagnostic tools. This is crucial for improving mental health assessments and interventions, as well as enhancing preventive medicine strategies. By tailoring early detection of BPD, clinicians can better identify at-risk individuals, mitigate the onset of more severe symptoms, and promote long-term well-being within the population.

Acknowledgements

The research team is grateful to all research participants for contributing their data to the study, as well as to Ivy Ng Ee Qi for her assistance in coordinating data collection for the study involving the healthy control sample.

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

Analysis of Covariance

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- BFI

Big Five Inventory

- BIS-15-SF

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale- Short Form

- BPD

Borderline Personality Disorder

- CFA

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- CFI

Comparative Fit Index

- DASS-21

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales

- DERS-SF

Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale- Short Form

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5

- IFI

Incremental Fit Index

- IIP-PD

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems – Personality Disorder Scales

- MSI-BPD

McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder

- NPV

Negative Predictive Value

- PAI-BOR

Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Features Scale

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- PPV

Positive Predictive Value

- RMSEA

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- RSOS

Rosenberg’s Stability of Self Scale

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview

- SCID-II

BPD Module of the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis II Personality Disorders

- STAXI-2

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2

- TLI

Tucker Lewis Index

Author contributions

SLK led the design and conceptualization of the overall study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. HMSS and LFC led data collection and write up involving the clinical sample of the study, and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. KAT contributed to data analyses and to drafting of the manuscript, and prepared Figs. 1 and 2. SV and NHZ contributed to data collection involving the healthy control sample and to editing of the manuscript. LCSW and SHS contributed to data collection involving the clinical sample and to drafting of the manuscript. MKW and CLE contributed to data collection involving the clinical sample. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from the Yale-NUS College Start Up Grant (R-607-264-328-121) awarded by Yale-NUS College to Dr. Shian-Ling Keng, the Early Career Researcher Grant Scheme awarded to Dr Samira Vafa (GRTIN-ECR(02)-DPSY-07-2024), and the Research Accelerator Grant Scheme awarded to Dr. Shian-Ling Keng (GRTIN-RAG(02)-DPSY-12-2024) by Sunway University.

Data availability

The data of this study are publicly available and can be accessed here: https://osf.io/vuzcr/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study obtained two separate ethics approval for each recruited sample. The ethics approval for the clinical sample was obtained from Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2019-495) of the National University of Malaysia, while the ethics approval for the control group was obtained from Research Ethics Committee of Sunway University (Approval Number: SUREC 2024/093). All participants signed the informed consent forms before the data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet [Internet]. 2004 Jul [cited 2025 Mar 1];364(9432):453–61. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673604167706 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [Internet]. Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association. 2013 [cited 2025 Mar 1]. Available from: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- 3.McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand [Internet]. 2000 Oct [cited 2025 Mar 1];102(4):256–64. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F. Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet [Internet]. 2011 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 1];377(9759):74–84. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673610614225 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Oldham JM, Psychiatry [Internet]. Borderline Personality Disorder and Suicidality. Am J. 2006 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Mar 1];163(1):20–6. Available from: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kehrer CA, Linehan MM. Interpersonal and Emotional Problem Solving Skills and Parasuicide among Women with Borderline Personality Disorder. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 1996 Jun [cited 2025 Mar 1];10(2):153–63. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/pedi.1996.10.2.153

- 7.Neacsiu AD, Eberle JW, Keng SL, Fang CM, Rosenthal MZ. Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder Across Sociocultural Groups: Findings, Issues, and Future Directions. Curr Psychiatry Rev [Internet]. 2017 Nov 24 [cited 2025 Mar 1];13(3). Available from: http://www.eurekaselect.com/153122/article

- 8.Varma SL, Wai BHK, Singh S, Subramaniam M. Psychiatric morbidity and HIV in female drug dependants in Malaysia. Eur Psychiatry [Internet]. 1998 [cited 2024 May 9];13(8):431–3. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-psychiatry/article/psychiatric-morbidity-and-hiv-in-female-drug-dependants-in-malaysia/8B22760AE967712DCBD79E3B04163CD1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hamidin A, Maniam T. A case control study on personality traits and disorders in deliberate self-harm in a Malaysian Hospital. Malays J Med Health Sci [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2024 May 9];4(2):71–82. Available from: http://www.medic.upm.edu.my/upload/dokumen/FKUSK1_MJMHS_2008V04N2_OP06.pdf

- 10.Chanen AM, Berk M, Thompson K. Integrating Early Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder and Mood Disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Sep [cited 2025 Mar 1];24(5):330–41. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00023727-201609000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Personal Disord. 2003;17(6):568–73. 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leichsenring F, Development, and First Results of the Borderline Personality Inventory. : A Self-Report Instrument for Assessing Borderline Personality Organization. J Pers Assess [Internet]. 1999 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 1];73(1):45–63. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327752JPA730104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bagby RM, Farvolden P. The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4). In: Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment. 2004. pp. 122–133.

- 14.Melartin T, Häkkinen M, Koivisto M, Suominen K, Isometsä E. Screening of psychiatric outpatients for borderline personality disorder with the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(6):475–9. 10.3109/08039480903062968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel AB, Sharp C, Fonagy P. Criterion validity of the MSI-BPD in a community sample of women. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2011;33(3):403–8. 10.1007/s10862-011-9238-5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noblin JL, Venta A, Sharp C. The validity of the MSI-BPD among inpatient adolescents. Assessment. 2014;21(2):210–7. 10.1177/1073191112473177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin JA, Tarantino DM, Levy KN. Investigating gender-based differential item functioning on the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD): an item response theory analysis. Psychol Assess. 2023;35(5):462–8. 10.1037/pas0001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.André JA, Verschuere B, Lobbestael J. Diagnostic value of the Dutch version of the McLean Screening Instrument for BPD (MSI-BPD). J Personal Disord. 2015;29(1):71–8. 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asl EM, Dabaghi P, Taghva A. Screening borderline personality disorder: The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder. J Res Med Sci [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Mar 3];25(1):97. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jrms/fulltext/2020/25000/Screening_borderline_personality_disorder__The.97.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Leung SW, Leung F. Construct Validity and Prevalence Rate of Borderline Personality Disorder Among Chinese Adolescents. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 2009 Oct [cited 2025 Mar 1];23(5):494–513. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/pedi.2009.23.5.494 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Munawar K, Aqeel M, Rehna T, Shuja KH, Bakrin FS, Choudhry FR. Validity and reliability of the Urdu version of the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder. Front Psychol. 2021;12: 533526. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.533526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keng SL, Lee Y, Drabu S, Hong RY, Chee CYI, Ho CSH et al. Construct Validity of the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder in Two Singaporean Samples. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 2019 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 1];33(4):450–69. Available from: 10.1521/pedi_2018_32_352 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hazrina MN. A A. Factorial Validity of the Malay-Translated Version of the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD) for Use Among Female Prisoner. Malays J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012;21(2). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/mjp/fulltext/2012/21020/factorial_validity_of_the_malay_translated_version.2.aspx

- 24.Cavelti M, Lerch S, Ghinea D, Fischer-Waldschmidt G, Resch F, Koenig J et al. Heterogeneity of borderline personality disorder symptoms in help-seeking adolescents. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregulation [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Mar 1];8(1):9. Available from: https://bpded.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40479-021-00147-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Gardner K, Qualter P. Reliability and validity of three screening measures of borderline personality disorder in a nonclinical population. Personal Individ Differ [Internet]. 2009 Apr [cited 2025 Mar 1];46(5–6):636–41. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0191886909000087

- 26.Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):284–90. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selby EA, Braithwaite SR, Joiner TE, Fincham FD. Features of borderline personality disorder, perceived childhood emotional invalidation, and dysfunction within current romantic relationships. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(6):885–93. 10.1037/a0013673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gone JP, Kirmayer LJ. On the wisdom of considering culture and context in psychopathology. In: Millon T, Krueger RF, Simonsen E, editors. Contemporary directions in psychopathology: scientific foundations of the DSM-V and ICD-11. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 72–96. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronningstam EF, Keng SL, Ridolfi ME, Arbabi M, Grenyer BFS. Cultural aspects in symptomatology, assessment, and treatment of personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(4): 22. 10.1007/s11920-018-0889-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Zhong J, Liu Y, x, Lu H. y. Application of Mclean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder in Chinese psychiatric samples. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;19(5):595–601.

- 31.Wang Y, Freedom L, Zhong J. The adaptation of McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder among Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2001.

- 32.Davidson M. Known-Groups Validity. In: Maggino F, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 17]. pp. 3764–3764. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-17299-1_1581

- 33.Velicer WF, Fava JL. Affects of variable and subject sampling on factor pattern recovery. Psychol Methods. 1998;3(2):231–51. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.2.231. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Clark SL, Miller MW. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: an evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ Psychol Meas. 2013;73(6):913–34. 10.1177/0013164413495237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morey LC. Personality assessment inventory [Internet]. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa FL. 1991 [cited 2024 May 9]. Available from: https://paa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/PAI_Plus_Interpretive_PiC.pdf

- 36.Stein MB, Pinsker-aspen JH, Hilsenroth MJ. Borderline pathology and the personality assessment inventory (PAI): an evaluation of criterion and concurrent validity. J Pers Assess. 2007;88(1):81–9. 10.1080/00223890709336838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beard C, Hsu KJ, Rifkin LS, Busch AB, Björgvinsson T. Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. J Affect Disord [Internet]. 2016 Mar [cited 2025 Mar 1];193:267–73. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165032715310272 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 1995 [cited 2024 May 9];33(3):335–43. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/000579679400075U [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Spinella M, NORMATIVE DATA AND A SHORT FORM OF, THE BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE, Int J. Neurosci [Internet]. 2007 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 1];117(3):359–68. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00207450600588881 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Kaufman EA, Xia M, Fosco G, Yaptangco M, Skidmore CR, Crowell SE. The difficulties in emotion regulation scale short form (DERS-SF): validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38(3):443–55. 10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [Internet]. 1965 [cited 2025 Mar 1]. Available from: https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t01038-000

- 44.Webster GD, Smith CV, Brunell AB, Paddock EL, Nezlek JB. Can Rosenberg’s (1965) Stability of Self Scale capture within-person self-esteem variability? Meta-analytic validity and test–retest reliability. J Res Personal [Internet]. 2017 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 1];69:156–69. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S009265661630054X

- 45.Scarpa A, Luscher KA, Smalley KJ, Pilkonis PA, Kim Y, Williams WC. Screening for Personality Disorders in a Nonclinical Population. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 1999 Dec [cited 2025 Mar 1];13(4):345–60. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/pedi.1999.13.4.345 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Spielberger CD. Professional manual for the State-Trait anger expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2). Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999.

- 47.John OP, Srivastava S. The big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: theory and research. 2nd edn. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 102–38. [Google Scholar]

- 48.First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer R, Williams J, Benjamin L. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

- 49.Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM‐IV axis I disorders (SCID I) and axis II disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(1):75–9. 10.1002/cpp.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maffei C, Fossati A, Agostoni I, Barraco A, Bagnato M, Deborah D et al. Interrater Reliability and Internal Consistency of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), Version 2.0. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 1997 Sep [cited 2025 Mar 1];11(3):279–84. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/pedi.1997.11.3.279 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Olsson UH, Foss T, Troye SV, Howell RD. The Performance of ML, GLS, and WLS Estimation in Structural Equation Modeling Under Conditions of Misspecification and Nonnormality. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J [Internet]. 2000 Oct [cited 2025 Mar 1];7(4):557–95. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15328007SEM0704_3

- 52.Byrne BM, Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS. EQS, and LISREL: Comparative Approaches to Testing for the Factorial Validity of a Measuring Instrument. Int J Test [Internet]. 2001 Mar [cited 2025 Mar 1];1(1):55–86. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327574IJT0101_4

- 53.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods [Internet]. 1999 Sep [cited 2025 Mar 1];4(3):272–99. Available from: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272

- 55.Johnson BN, Lumley MA, Cheavens JS, McKernan LC. Exploring the links among borderline personality disorder symptoms, trauma, and pain in patients with chronic pain disorders. J Psychosom Res [Internet]. 2020 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 1];135:110164. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022399920300453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Trull TJ, Solhan MB, Tragesser SL, Jahng S, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, et al. Affective instability: measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(3):647–61. 10.1037/a0012532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, Koenigsberg HW, Silverman J, Siever LJ. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatr Res [Internet]. 2001 Nov [cited 2025 Mar 1];35(6):307–12. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022395601000383 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Chapman AL, Leung DW, Lynch TR. Impulsivity and Emotion Dysregulation in Borderline Personality Disorder. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 2008 Apr [cited 2025 Mar 1];22(2):148–64. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.2.148 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Hill J, Pilkonis P, Morse J, Feske U, Reynolds S, Hope H et al. Social domain dysfunction and disorganization in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med [Internet]. 2008 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 1];38(1):135–46. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0033291707001626/type/journal_article [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, McDougall E, Yuen HP, Rawlings D et al. Screening for Borderline Personality Disorder in Outpatient Youth. J Personal Disord [Internet]. 2008 Aug [cited 2025 Mar 1];22(4):353–64. Available from: http://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Kröger C, Vonau M, Kliem S, Kosfelder J. Emotion dysregulation as a core feature of borderline personality disorder: comparison of the discriminatory ability of two self-rating measures. Psychopathology. 2011;44(4):253–60. 10.1159/000322806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are publicly available and can be accessed here: https://osf.io/vuzcr/.