Abstract

Background

Over the last decade, the pharmaceutical industry has witnessed longer, more complex, and expensive clinical trials. This complexity contributes to delays in clinical trial implementation, execution, monitoring, recruitment, data cleaning, and interpretation. Our aim was to develop a protocol complexity tool (PCT) to simplify clinical trial execution without compromising science or quality.

Methods

Using a collaborative design process, a taskforce comprising 20 cross-functional experts in clinical trial design and execution developed a PCT, between June 2021 and December 2022 and comprising 26 questions across 5 domains (operational execution, regulatory oversight, patient burden, site burden and study design). Individual domain scores and total complexity score (TCS) were calculated, and agreed by consensus, for 16 pre-identified phase II-IV difficult clinical trials across 3 therapeutic areas. Change in score was assessed post-PCT pass through. The relationship between TCS and key trial indicators (i.e. time-to-site activation and participant enrolment) was assessed for 26 studies by correlation analysis.

Results

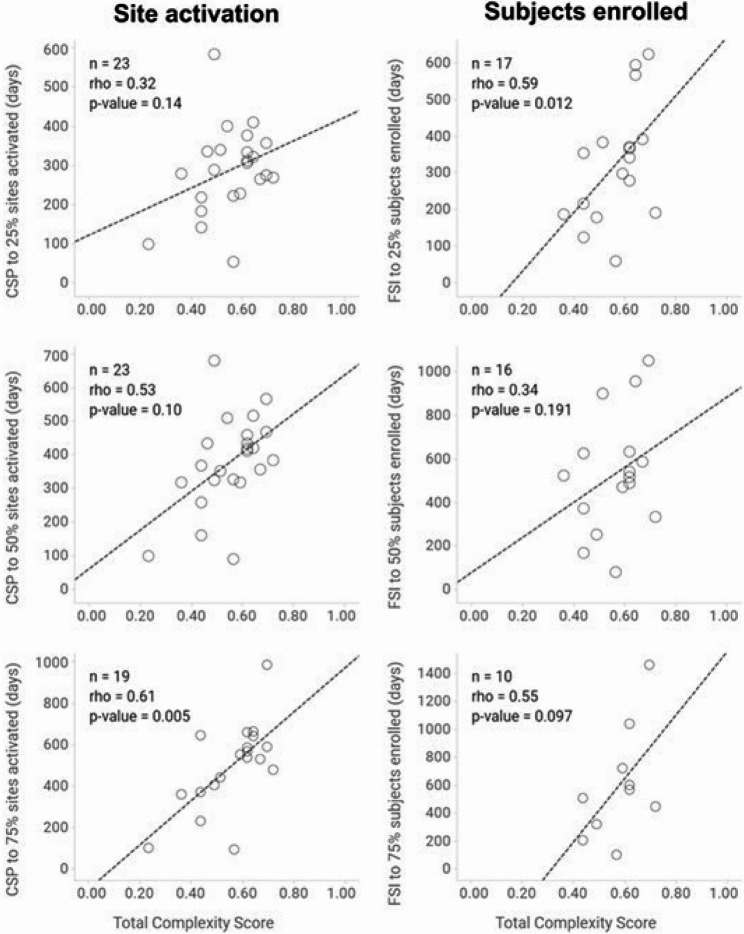

Post-PCT pass through, the TCS was reduced in 12 trials (75%), remained the same in 3 trials (18.8%) and increased in 1 trial (6.2%). Complexity was most notably decreased in the operational execution and site burden domains, decreasing in 50% and 43.8% of assessed trials, respectively. Time-to-site activation and participant enrolment positively correlated with TCS, reaching statistical significance at 75% site activation (rho = 0.61; p = 0.005; n = 19) and 25% participant recruitment (rho = 0.59; p = 0.012; n = 17).

Conclusions

We have developed a Protocol Complexity Tool to objectively measure the complexity of a study protocol consistently and transparently. The PCT is capable of driving simplification, enhancing collaboration, and creating additional confidence in trial designs. In the future, we envision the tool will support earlier discussions to develop protocols that are simpler to execute and more cost-effective.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12874-025-02652-9.

Keywords: Operational execution, Regulatory oversight, Patient burden, Site burden, Study design

Background

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), when appropriately designed, conducted and reported, provide the highest level of evidence to evaluate and translate research data into clinical practice. However, they have become ever more expensive and complex, and the duration required to finalise recruitment has increased [1, 2]. A recent review of 220 completed studies reported a 37% increase in the number of endpoints, a 39% increase in the number of participating countries, a 35% increase in the number of patients, a substantial increase in the number of investigative sites, and a significant increase in trial duration between 2011 and 2015 and 2016–2021 [1]. Others have reported an increase in the duration of phase 3 studies of approximately 1 year (from 2.25 years to 3.25 years) between 2010 and 2021 [3]. Phase 3 trials have also become more expensive, with the cost per patient rising from $728 in 2001–2005 to $978 in 2011–2015 [4].

The traditional risks of failing to demonstrate safety and efficacy remain [5]. However, in addition to these risks, the industry faces rising operational and execution risks [6–12]. Patient enrolment and logistical problems top the list of difficulties [4, 8–11, 13–15]. The literature has shown that 86% of trials fail to meet enrolment timelines, and 1/3 of phase 3 trials fail due to enrolment problems [16]. However, there are reasons to believe that operational failure might be more common than generally reported in the literature [17–20], with significant variations reported between different therapeutic areas [21]. Other risk factors included the number of endpoints, eligibility criteria, procedures per visit, number of countries, and investigative sites [11].

Pharmaceutical companies frequently focus on disease markets with greater unmet need and more demand, but also with a significant amount of competition [22]. In the clinical trial setting, competition has two main components: internal competition for resources and external competition for patient populations and sites. Many times, new compounds require differentiation from existing standard of care that leads to more endpoints, study assessments, and eventually to complicated studies [1]. Protocols should be sufficiently complex to enable competitive drug development, but simple enough to be operationalised. Operational complexity contributes to study delays and significantly burdens sites and patients [23]. Furthermore, prior to approval and execution, a study protocol is typically subjected to a series of protocol review committees and feedback is solicited on draft protocol designs from patients and investigative site staff [4, 24]. The approval process and multiple inputs ultimately translates into larger studies involving more participating sites, that lead to slower recruitment rates, that ultimately result in longer timelines to complete [23].

Although some clinical trial complexity tools for workload planning and characterization have been described [25, 26], there is a lack of established methodologies to measure protocol complexity, facilitate protocol simplification, or accelerate study completion. We have developed the Protocol Complexity Tool (PCT) to objectively measure the complexity of a protocol routinely and uniformly during the design and finalisation of study protocols. The aim of this article was to describe the development and utility of the PCT.

Methods

Study design

This study, conducted between June 2021 and December 2022, utilised a collaborative design process to identify and categorize key trial design features and components necessary to describe and assess protocol complexity (Additional file 1). Decisions were balanced, considering the necessity of maintaining good science while recognizing the need for more effective spend of resources. A PCT was developed after an extensive literature review, as well as discussions with, and consensus of a taskforce comprising 20 cross-functional experts in the design, operation and execution of clinical trials.

Protocol complexity tool development

Identification and categorization of trial design components

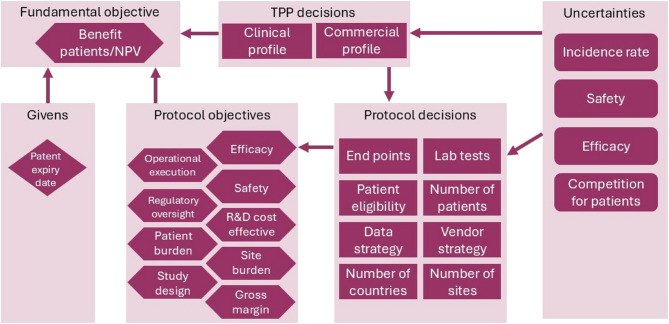

Components considered important when designing clinical trials included ‘givens’, ‘objectives’, ‘decisions’ and ‘uncertainties’ (Fig. 1). ‘Objectives’ were sub-divided into fundamental objectives (e.g. benefits for patients and Net Present Value) and eight protocol objectives (including efficacy, safety, regulatory oversight, site burden, etc.). ‘Decisions’ were categorized as either Target Product Profile (TPP) or protocol decisions. TPP decisions reflected a trade-off between the clinical profile (i.e. what is technically feasible) and the commercial profile (i.e. what is needed to launch a competitive drug). A total of 8 protocol decisions that must be made in the protocol design were identified and included the number of endpoints, patients, eligibility criteria, etc. (Fig. 1) In addition, several uncertainties were recognised. We considered efficacy, safety, incidence rate, and patient competition as the most relevant. Finally, patent expiratory date was the only ‘given’ identified. The protocol objections and decision components were reorganized and revealed the need for 3 tools to measure different protocol metrics namely: (i) benefits (both clinical and commercial), (ii) costs and (iii) complexity (Fig. 2). Tools to measure benefit [27] and cost are already available. This paper focuses on development and testing of a PCT.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the protocol complexity tool design process

Abbreviations: R+D: research and development; TPP: Target Product Profile

Fig. 2.

Reorganization of protocol complexity tool into components of 3 protocol assessment tools

Abbreviations: R+D: research and development; TPP: Target Product Profile

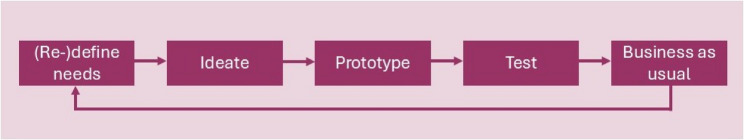

Agile development

The PCT was developed collaboratively using a workflow of design thinking approach (Fig. 3) and was initially made available as a prototype web application. Consensus was achieved via effective dialogue and articulation of choices and their consequences, integrating over 450 comments and facilitating five version releases. After the fifth release, the tool was incorporated into an existing trial design and costing tool.

Fig. 3.

Workflow design of thinking

Protocol complexity tool

The final PCT comprised 5 domains: i) study design, (ii) patient burden, (iii) site burden, (iv) regulatory oversight and (v) operational execution. A total of 26 multiple-choice questions were used to assess the complexity of each the five domains. Each question has 3 answer options and is scored on a 3-point scale: low complexity = 0, med complexity = 0.5 and high complexity = 1. The individual question scores were averaged within each domain to give a domain complexity score (DCS) between 0 and 1 for each domain. The five DCS results were summed to provide a total complexity score (TCS) between 0 and 5 (Fig. 3). Each answer was identically weighted. Multiple choice questions for each study were answered by authors with expertise in protocol design and implementation within each therapeutic area (Additional file 2). All scores were reviewed and agreed by consensus. The full list of questions, all possible answers, and scoring system of the PCT are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Protocol complexity tool domains, questions, answers and scoring

| Domain | Questions | Complexity | Definition | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | 1 |

Endpoints ≥ 5 primary/secondary endpoints (lined to TPP); ≥ 5 exploratory endpoints; Some primary/secondary endpoints are novel or unvalidated |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 |

| Mid | 1 of the complexity factors is true | 0.5 | |||

| High | > 1 of the complexity factors is true | 1 | |||

| 2 | Learnings from previous studies | Low | The study design has been fully validated in the disease setting (e.g. considerable learning were applied from previous studies or design is based on effective analogue) | 0 | |

| Mid | The study design has been partially validated in the disease setting (e.g. some learnings were applied from previous studies or design is partially based on effective analogue) | 0.5 | |||

| High | The study design has not been validated in the disease setting | 1 | |||

| 3 |

Study type Given the complexity factors: Paediatric or adolescent study population; Complex PK/PD sampling schedule; Complex mechanistic study or mechanistic sub-study included |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 of the complexity factors is true | 0.5 | |||

| High | > 1 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 4 | Design complexity | Low | Protocol includes a statistical study design with a single final analysis planned and includes ≤ 2 treatment arms | 0 | |

| Mid | Protocol includes multiple analysis time points (e.g. for routine interim and final analyses), or 2 treatment arms in a cross-over design, or a parallel group design with 3 or 4 treatment arms | 0.5 | |||

| High | Protocol includes multiple analysis time points (e.g. for multiple interim analyses with stopping criteria, multiple sage design, adaptive design, umbrella/basket study design) | 1 | |||

| 5 | Sub-studies | Low | No sub-studies are included in the protocol | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 sub-study is included in the protocol | 0.5 | |||

| High | > 1 sub-studies are included in the protocol | 1 | |||

| 6 | Other study design issues* | Low | Decreased complexity due to other factors | 0 | |

| Mid | No effect on complexity due to other factors | 0.5 | |||

| High | Increased complexity due to other factors | 1 | |||

| Patient burden | 7 |

Patient visit burden Give the complexity factors: - Treatment duration (> 340 days for late studies, >90 days for early studies); - Number of visits (> 12 per year per patient); - High frequency visits (weekly or more frequent); - Requirement for overnight stay; - Number of procedures (> 300/year per patient for late studies, > 10/visit/patient for early studies - Length of any visit (> 6 h) as recorded in the study design visualization tool (SNAKE tool) |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 |

| Mid | Some (i.e. 1–3) of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | Most (i.e. ≥4) of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 8 |

Patient assessment burden Given the complexity factors: - Invasive assessments; - Blood draws (> 3 mL); - IP toxicity; - PK included; - Multiple additional patient self-assessments (e.g. spirometry, e-diaries) |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 9 | Patient insights activity | Low | Team consulted patient insights (current or historical) and all major comments implemented | 0 | |

| Mid | Team consulted patient insights (current or historical) and this did not lead to significant study changes | 0.5 | |||

| High | Team did not consult patient insights (current or historical) | 1 | |||

| 10 | Other patient burden factors | Low | Decreased complexity due to other factors | 0 | |

| Mid | No effect on complexity due to other factors | 0.5 | |||

| High | Increased complexity due to other factors | 1 | |||

| Site burden | 11 |

Site start up Given the complexity factors: - Multiple procedures require additional trainings/certificates; - Requirement for central equipment (e.g. central spirometry); - New equipment/digital device which require site training; - High perceived risk of protocol amendments |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 12 |

Site execution Given the complexity factors: - Complex courier (e.g. samples to multiple locations) - Many procedures (> 300/patient/year for late studies, > 10/visit/patient for early studies); - Few patients per site (< 5 for late studies, < 3 for early studies), due to scarcity of suitable patients (e.g. a rare indication) - Extra contracting needed (e.g. with at-home nursing service); - Complex administration (dosing, IP preparation); - Involvement of multiple institutions/departments |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | Some (i.e. 1–3) of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | Most (i.e. ≥4) of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 13 |

Schedule of assessment burden Given the complexity factors: - Timing of visit > 6 h as recorded in the study design visualization tool (SNAKE tool); - Patients are required to attend > 3 departments/locations in a single visit; - Majority of site expertise is needed for the study |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 of the complexity factors is true | 0.5 | |||

| High | > 1 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 14 |

Treatment management Given the complexity factors: - Complex packaging (multiple bottles, bottles vs. blister packs, multiple injections); - Novel administration device required; - Self-administration is not possible; - Multiple protocol-mandated medications (IP, active comparator or background therapy) to manage - Need to actively manage the patient’s dose levels of IP, active comparator and/or background therapy (e.g. via titration) |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 15 | Other site burden factors | Low | Decreased complexity due to other factors | 0 | |

| Mid | No effect on complexity due to other factors | 0.5 | |||

| High | Increased complexity due to other factors | 1 | |||

| Regulatory oversight | 16 | Discussion with regulators | Low | Both indication and the development program are supported by regulators | 0 |

| Mid | The indication is supported by regulators, but not the development program | 0.5 | |||

| High | Neither the indication nor the development program is supported by regulators | 1 | |||

| 17 | Endpoints | Low | The endpoints are aligned with guidance or prior Health Authority feedback from this program | 0 | |

| Mid | The endpoints are aligned with guidance or prior Health Authority feedback from another program | 0.5 | |||

| High | The endpoints are not aligned with existing guidance or prior Health Authority feedback | 1 | |||

| 18 |

Regulatory requirements Given the complexity factors: - Severe privacy concerns regarding digital data collection, storage and use (e.g. GPS, personal information); - Severe security concerns regarding digital data collection storage and use (e.g. general data protection regulation considerations, cross-border data transmission); - Severe concerns regarding safety (e.g. known in class box warnings); - Known risk of regulatory issues in some regions for the project (e.g. not following guidance); - Severe project concerns regarding form and content of clinical study reports and regulatory communication documentation |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 19 | Other regulatory oversight factors | Low | Decreased complexity due to other factors | 0 | |

| Mid | No effect on complexity due to other factors | 0.5 | |||

| High | Increased complexity due to other factors | 1 | |||

| Operational execution | 20 |

Contracting vendors Given the complexity factors: - >4 vendors (all vendors including labs); - Use of a non-preferred vendor; - Increased vendor complexity (e.g. contracting arrangements, Home Health Professionals contracts and governance); - Using a vendor where Master Service Agreement is not in place and a Due Diligence process is needed. |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 21 |

Countries Given the complexity factors: - Large number of participating countries (n > 15 for Late Studies, n > 5 for Early Studies); - Some countries without good infrastructure (e.g. internet, IP distribution network, transport/shipment links), local therapy knowledge/KEEs); - Some countries do not have similar local guidelines/SoC |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 of the complexity factors is true | 0.5 | |||

| High | > 1 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 22 |

Analysis and reporting Given the complexity factors: - Computational time required to produce the results is > 2 weeks; - Total number of tables and figures > 200; - Statistical model convergence issues are expected; - Data quality is low; - Complex novel methods are introduced in the study (e.g. statistical ML/AI) |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 23 |

Site selection Given the complexity factors: - Large number of sites (n > 250 for Late Studies, n > 100 for Early Studies); - Insufficient number of available sites (i.e. need to engage with lower tier sites); - AZ has limited experience in disease (i.e. need to establish new relationships); - Majority (> 75%) of sites previously not collaborated with AZ |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 24 |

Competition Given the complexity factors: - Competition found in > 25% of sites; - >1 external competing study for same target patient population with similar MOA (e.g. severe COPD treated with a biologic); - Competition with other AZ studies; - Competition expected in multiple regions (e.g. EU & US) |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 25 |

Investigational product and comparator Given the complexity factors: - Current formulation is not suitable for clinical development (e.g. solubility issues prevent achievement of therapeutic dose); - Shelf life < 12 months; - Previous country level importation issues with IP or comparator; - Lack of expertise or resources to ramp up the production of compound sufficiently (e.g. personalised manufacturing) |

Low | None of the complexity factors is true | 0 | |

| Mid | 1 or 2 of the complexity factors are true | 0.5 | |||

| High | ≥ 3 of the complexity factors are true | 1 | |||

| 26 | Other operational factors* | Low | Decreased complexity due to other factors | 0 | |

| Mid | No effect on complexity due to other factors | 0.5 | |||

| High | Increased complexity due to other factors | 1 | |||

| TCS | Sum of domain scores | ||||

AI artificial intelligence, AZ AstraZeneca, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DCS domain complexity score, EU European Union, GPS global positioning system, IP investigational product, KEE key external expert, ML machine learning, MOA mechanism of action, PK pharmacokinetics, SoC standard of care, TCS total complexity score, TPP target product profile, US United States

*added in recognition that not all aspects can be covered in a finite set of questions. This final question is used to address issues that have not been covered in the other questions of the same domain

Metrics provided by the PCT include individual domain complexity score (DCS), overall TCS and change in TCS which were calculated as follows:

|

where N is the number of questions within the domain.

|

where D is the number of domains.

|

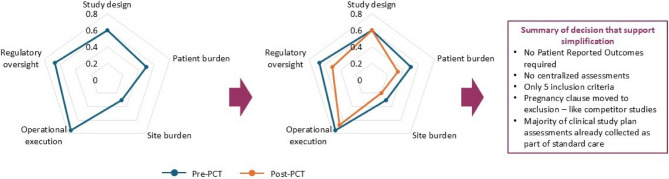

An example output from the PCT is provided in Fig. 4, facilitating visualization of protocol complexity compared to reference.

Fig. 4.

Example of spider plot output from the protocol complexity tool

Protocol complexity tool in use

Individual DCS and TCS were calculated for 16 pre-identified phase II-IV clinical trials, across 3 broad therapeutic areas (i.e. respiratory and immunology, cardiovascular renal metabolism and V & I) with a complex design and change in score assessed post-PCT pass through. Trials considered for inclusion were required to be in the ‘start up’ or ‘introducing amendments’ phase, were selected a priori across a range of therapy areas and were considered complex by task force members (Table 2). The relationship between TCS and key trial indicators (i.e. time to site activation and participant enrolment) was assessed for 23 studies by correlation analysis.

Table 2.

Protocols passed through the protocol complexity tool (n = 16) and included in the correlation analyses (n = 23)

| Protocol (Clin Trials.gov) | Therapy area | Study design | No. countries | No. sites | No. patients | Phase | Published Ref if approp. |

Start and end date (status) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chinook D3250C00059 |

R&I | A Phase 4, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel Group, Placebo Controlled Study to Evaluate the Effect of Benralizumab on Structural and Lung Function Changes in Severe Eosinophilic Asthmatics | 5 | 56 | 81 | IV | N |

Start: 17.10.19 End: 09.09.26 (Recruiting) |

|

Crescendo D6582C00001 |

R&I | A Phase IIa Randomised, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled, Parallel Arm, Multi-Centre Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Mitiperstat (AZD4831), for 12–24 Weeks, in Patients With Moderate to Severe COPD | 14 | 146 | 380 | II | N |

Start: 14.11.22 End: 12.08.24 (Completed) |

|

Deliver D169CC00001 |

CVRM | An International, Double-blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Study to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on Reducing CV Death or Worsening Heart Failure in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction | 21 | 458 | 6263 | III |

Y [31] |

Start: 27.08.18 End: 27.03.22 (Completed) |

|

Dialize-Outcomes D9487C00001 |

CVRM | An International, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Effect of Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate on Arrythmia-related Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants on Chronic Hemodialysis With Recurrent Hyperkalemia | 26 | 490 | 2698 | III | N |

Start: 30.04.21 End: 07.03.24 (Terminated) |

|

Dominica D3250C00024 |

R&I | Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab in Paediatric Patients With Severe Eosinophilic Asthma | 11 | 86 | 200 | III | N |

Start: 05.04.23 End: 16.05.32 (Recruiting) |

|

Endeavor D6580C00010 |

CVRM | A Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Multi-center Sequential Phase 2b and Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of AZD4831 Administered for Up to 48 Weeks in Participants With Heart Failure With Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction > 40% | 18 | 288 | 711 | II/III | N |

Start: 30.06.21 End: 27.03.24 (Completed) |

|

Kalos D5982C00007 |

R&I | A Randomized, Double-Blind, Double Dummy, Parallel Group, Multicenter Variable Length Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of PT010 Relative to PT009 and Symbicort® in Adult and Adolescent Participants With Inadequately Controlled Asthma | 23 | 642 | 2200 | III | N |

Start: 15.12.20 End: 21.03.25 (Completed) |

|

Logos D5982C00008 |

R&I | A Randomized, Double-Blind, Double Dummy, Parallel Group, Multicenter Variable Length Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of PT010 Relative to PT009 and Symbicort® in Adult and Adolescent Participants With Inadequately Controlled Asthma | 18 | 577 | 2200 | III | N |

Start: 01.03.21 End: 20.03.25 (Completed) |

|

MPO D5680C00017 |

R&I | Terminated | ||||||

|

Natron D3254C00001 |

R&I | A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled, 24 Week Phase III Study With an Open-label Extension to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab in Patients With Hypereosinophilic Syndrome | 17 | 69 | 120 | III | N |

Start: 20.07.20 End: 23.04.27 (active not recruiting) |

|

NGP Safety D5985C00003 |

R&I | A Randomized, Double-Blind, 12-Week (With an Extension to 52 Weeks in a Subset of Participants), Multi-Center Study to Assess the Safety of Budesonide, Glycopyrronium, and Formoterol Fumarate (BGF) Delivered by MDI HFO Compared to BGF Delivered by MDI HFA in Participants With Moderate to Very Severe COPD | 9 | 110 | 558 | III | N |

Start: 27.09.22 End: 26.03.24 (Completed) |

|

Nimbus D3551C00001 |

R&I | A 6-month, Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Multi-centre, Parallel-group, Phase II Study with an Optional Safety Extension Treatment Period up to 6 months, to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of 3 Different Doses of AZD5069 Twice Daily as Add-on Treatment to Medium to High Dose ICS and LABA, in Patients with Uncontrolled Persistent Asthma | 13 | 99 | 1146 | II |

Y [32] |

Start: 11.2012 End: 08.2014 (Completed) |

|

Provent D8850C00002 |

V&I | A Phase III Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Multi-center Study in Adults to Determine the Safety and Efficacy of AZD7442, a Combination Product of Two Monoclonal Antibodies (AZD8895 and AZD1061), for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis of COVID-19 | 5 | 118 | 5197 | III |

Y [33] |

Start: 21.11.20 End: 08.12.23 (Completed) |

|

Stabilize-CKD D9488C00001 |

CVRM | A Phase 3, International, Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Effect of Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate on CKD Progression in Participants With CKD and Hyperkalaemia or at Risk of Hyperkalaemia | 20 | 462 | 716 | III | N |

Start: 30.09.21 End: 07.02.24 (Terminated) |

|

Tilia D9185C00001 |

R&I | A Phase III, Multicentre, Randomised, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Tozorakimab (MEDI3506) in Patients Hospitalised for Viral Lung Infection Requiring Supplemental Oxygen | 39 | 493 | 2902 | III | N |

Start: 13.12.22 End: 19.06.26 (Recruiting) |

|

Vathos D5982C00006 |

R&I | A Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel Group, Multicenter 24 Week Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Budesonide and Formoterol Fumarate MDI Relative to Budesonide MDI and Open-Label Symbicort® Turbuhaler® in Participants With Inadequately Controlled Asthma | 8 | 245 | 630 | III | N |

Start: 12.01.22 End: 26.02.25 (Completed) |

|

Etesian D7990C00003 |

CVRM | A Randomized, Parallel, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Dose-ranging, Phase 2b Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of AZD8233 Treatment in Participants With Dyslipidemia | 3 | 35 | 119 | IIb | N |

Start: 28.10.20 End: 20.07.21 (Completed) |

|

Resolute D3251C00014 |

R&I | A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Chronic-dosing, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab 100 mg in Patients With Moderate to Very Severe COPD With a History of Frequent COPD Exacerbations and Elevated Peripheral Blood Eosinophils | 30 | 582 | 645 | III | N |

Start: 26.08.19 End: 08.08.25 (Active, not recruiting) |

|

Oberon D9180C00003 |

R&I | A Phase III, Multicentre, Randomised, Double-blind, Chronic-dosing, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Two Dose Regimens of Tozorakimab in Participants With Symptomatic COPD With a History of COPD Exacerbations | 20 | 375 | 1060 | III | N |

Start: 03.01.22 End: 23.03.25 (Active, not recruiting) |

|

Titania D9180C00004 |

R&I | A Phase III, Multicentre, Randomised, Double-blind, Chronic-dosing, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Two Dose Regimens of Tozorakimab in Participants With Symptomatic COPD With a History of COPD Exacerbations | 19 | 332 | 1060 | III | N |

Start: 07.02.22 End: 19.01.26 (Active, not recruiting) |

|

Hudson GI D3258C00001 |

R&I | A Multi-center, Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled 3-Part Phase 3 Study to Demonstrate the Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab in Patients With Eosinophilic Gastritis and/or Gastroenteritis | 15 | 160 | 12 | III | N |

Start: 18.01.22 End: 13.02.24 (Terminated) |

|

Mahale D325BC00001 |

R&I | A Multicentre, Randomised, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled, 52 Week, Phase III Study With an Open-label Extension to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Benralizumab in Patients With Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis | 16 | 164 | 100 | III | N |

Start: 21.07.21 End: 16.04.24 (Terminated) |

|

Frontier4 D9180C00002 |

R&I | A Phase II, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of MEDI3506 in Participants With Moderate to Severe COPD and Chronic Bronchitis | 15 | 159 | 136 | II | N |

Start: 14.12.20 End: 13.11.23 (Completed) |

|

Zenith D4325C00001 |

CVRM | A Phase 2b Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled, Parallel Group Dose-Ranging Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Zibotentan and Dapagliflozin in Patients With CKD With Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate ≥ 20 mL/Min/1.73 m^ | 20 | 251 | 542 | IIb |

Y [34] |

Start: 28.04.21 End: 01.06.23 (Completed) |

|

Flash D7552C00001 |

R&I | A Phase 2a, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Assess Efficacy and Safety of Atuliflapon Given Orally Once Daily for Twelve Weeks in Adults With Moderate to Severe Uncontrolled Asthma | 25 | 388 | 666 | IIa | N |

Start: 27.01.22 End: 29.01.26 (Recruiting) |

Abbreviations: CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CV cardiovascular, CVRM cardiovascular renal and metabolism, HFA hydrofluoroalkane, HFO Hydrofluoroolefin, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, LABA long-acting β2-agonist, MDI metered dose inhaler, NCT national clinical trial, R&I respiratory and immunology

Emperor, Nimbus, and MPO studies were not included in the correlation analysis due to missing data regarding operational metrics

*First 16 trials assessed for complexity pre- and post-PCT pass through

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean [standard deviation, SD]); median [interquartile range]) were used to summarize total and domain complexity scores pre- and post-PCT, overall and for each of 16 studies assessed (see Table 2). The proportion of studies for which total and domain scores ‘decreased’, remained ‘unchanged’ and ‘increased’ was also calculated. Spearman’s’ correlation was used to assess the relationship between TCS and two key trial metrics (site activation and participants enrolled). An assumption of causality was made (i.e., a high complexity score causes a trial to take longer to finish). In total, 23 studies were included in the association analysis (see Table 2). The TCS was calculated as the sum of all domain scores from individual parameter axes (study design, patient burden, site burden, regulatory oversight, and operational execution) divided by the maximum possible sum of such scores achievable in the PCT. Site activation was expressed as the number of days between protocol finalization and the time that a certain percentage of sites (25–75%) had been activated. Participant enrolment was expressed as the number of days between first participant in and a certain percentage of participant recruitment (25–75%).

Results

Effect of protocol complexity tool pass through

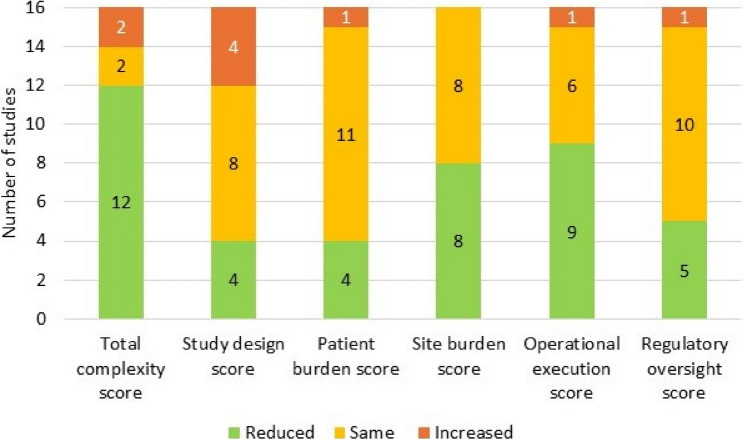

Use of the PCT reduced protocol complexity by 11% on average (n = 16 studies), reducing the TCS from 2.55 (SD 0.41) pre-PCT to 2.27 (SD 0.41) post-PCT (Table 3). All PCT domains contributed, but complexity reduction was predominantly driven by reductions in mean site burden, operational execution and regulatory oversight scores, which were reduced post-PCT by 16%, 17% and 15%, respectively. TCS was reduced post-PCT in 12 trials (75%), remained the same in 2 trials (12.5%) and increased in 2 trials (12.5%) (Fig. 5). Operational execution score was most frequently reduced post-PCT (9 studies; 56%), followed by site burden score (8 studies; 50%); although 8 trials (50%) showed no reduction in site burden score post-PCT. Regulatory oversight score was reduced in 5 studies (10%) and study design and patient burden scores were each reduced in 4 trials (25%); however, scores remained unchanged for the majority of studies for each of these domains (Fig. 5). DCSs increased in a minority of studies, most notably for study design which saw a DCS increase in 4 studies. The pre-and post-PCT DCS and TCS for each of the 16 studies is provided in online supplement (Additional file 3) and plotted for one of these studies (i.e. TILIA, NCT05624450) in Fig. 6. A trial of this size (n = 2902 patients) would usually have 12–18 inclusion criteria. Pass through the PCT enabled a reduction to 5 inclusion criteria with additional significant study simplification.

Table 3.

Mean change in domain complexity score and total complexity score post-Protocol complexity tool pass-through

| Domain | Pre-PCT | Post-PCT | Change in score | % mean change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study design DCS Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

0.57 (0.18) 0.60 (0.25) |

0.56 (0.13) 0.60 (0.20) |

−0.01 0.00 |

−2% |

|

Patient burden DCS Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

0.51 (0.13) 0.50 (0.00) |

0.48 (0.13) 0.50 (0.17) |

−0.03 0.00 |

−6% |

|

Site burden Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

0.46 (0.13) 0.50 (0.15) |

0.38 (0.16) 0.40 (0.25) |

−0.08 −0.10 |

−16% |

|

Operational execution DSC Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

0.65 (0.20) 0.67 (0.25) |

0.54 (0.17) 0.50 (0.29) |

−0.11 −0.17 |

−17% |

|

Regulatory oversight DCS Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

0.35 (0.19) 0.33 (0.33) |

0.30 (0.16) 0.25 (0.21) |

−0.05 −0.08 |

−15% |

|

TCS Mean (SD) Median (IQR) |

2.55 (0.41) 2.56 (0.58) |

2.27 (0.41) 2.23 (0.78) |

−0.28 −0.33 |

−11% |

DCS domain complexity score, IQR inter-quartile range, PCT protocol complexity tool, SD standard deviation, TCS total complexity score

Fig. 5.

% of studies (n=16) with reduced, unchanged and increased complexity scores post-PCT pass through

Abbreviations: PCT: protocol complexity tool

Fig. 6.

Example of comparison of individual DCS for TILIA protocol (NCT05624450) pre- and post-PCT pass through

Legend: Scoring scheme: there are 5 domains and 26 questions. The response to each individual question is one of 3 levels - the equivalent low (0), medium (1) or high (2). The result for each axis is the sum of the individual questions divided by maximum score for each domain. Thus, the scale for each axis is 0 (all questions answered as'low' complexity) to 1 (all questions answered as'high' complexity). Abbreviations: DCS: domain complexity score; PCT: protocol complexity score

Protocol complexity correlations

Protocol complexity correlated reasonably well with key study metrics. For site activation, this correlation followed a gradient; highest (rho = 0.61; p = 0.005; n = 19) when 75% of sites were activated, reducing to 0.53 (p = 0.10; n = 23) and 0.32 (p = 0.14; n = 23) when 50% and 25% of the sites were activated, respectively (Fig. 7). For Participant enrolment the picture was more complex. Correlation with TCS was greatest when 25% of participants had been recruited (rho = 0.59; p = 0.012; n = 17), reducing to 0.34 (p = 0.191; n = 16) when 50% of participants had been enrolled, but increasing again to 0.55 (p = 0.097; n = 10) when 75% of participants had been enrolled (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Correlation between PCT and site activation and participant enrollment

Abbreviations: CSP=Clinical Study Plan, FSI=First Subject In

Discussion

Although some tools are described to assess the quality of RCTS, and standards for their conduct and reporting are well-established [28, 29], complementary tools to assess RCT complexity have not been developed. This is surprising when one considers that phase 3 RCTs are necessary to evaluate the efficacy and safety of candidate drugs, are a requirement by regulatory authorities worldwide, and are arguab

y, the most complex experiments performed in investigative medicine. Many trials fail because protocols are overly complex, showing a clear unmet need. To fill this gap, we developed a tool, the 5-domain PCT, informed by the literature and agreed by expert consensus, to measure protocol complexity consistently and transparently. We showed the benefit of PCT pass through, reducing overall protocol complexity in 75% of trials assessed, driven predominantly by complexity reduction in the operational execution and site burden domains. To date, 26 studies have been assessed using the PCT. This has led to future cost avoidance estimated at $10 M-$50 M per year and $ 930 K in full time equivalent hours (approximately 9,500) saved over a 3-year time horizon across AstraZeneca’s BioPharma R&D organization. Costs avoided were based on scale up based on one R&I study with comparison to original vendor contracts and considering future pipeline activities (see additional file 4). Cost savings were based on reduction of hours spent on scenario planning and protocol planning multiplied by hourly rates of appropriate functions in all studies assessed (see additional file 4). Furthermore, the PCT complexity metrics (i.e. DCS and TCS) enabled complexity visualization, cross protocol comparison, and facilitated discussion of possible simplified trade-offs that balance TPP demands with operational constraints, and/or provide a rationale for greater complexity if considered necessary. Finally, significant correlation of TCS with both site activation and participant enrolment was encouraging, suggesting robustness of the tool in complexity assessment, although additional tool validation is warranted.

Development of the PCT fills an important gap in the clinical trial toolbox. Its objective is not to strictly minimise the complexity of a protocol. A drug must be competitive in the market; hence, some complexity will be necessary. These product requirements are defined in the TPP which explains competitor attributes and trial landscape, the novel drug’s expected efficacy and safety profile, the number of endpoints, the expected number of participants needed to demonstrate a positive effect, and the timelines to finish the study. The PCT, therefore assessed the complexity defined by the TPP, enabling the project team to systematically explore the decision space, whilst recognizing that design decisions cannot be better than the best alternative identified. Designed to be easy to use and self-instructive, the tool can be used compare complexity of protocols currently being designed with previous comparable protocols or older versions of the same protocol. Use of the same tool to assess protocol complexity across therapy areas and visualization of complexity via production of complexity metrics should encourage earlier and more efficient collaboration between stakeholders representing commercial, clinical, and operations, facilitating discussion of simplified trade-offs that balance TPP demands with operational constraints and/or provide a rationale for greater complexity if considered necessary. Earlier and more efficient collaboration enables the design team to identify an approach that adds value to the business case and is operationally feasible. Once this insight is obtained, the preferred options can be presented to governance. Some studies are complex for good reason, but complexity trade-offs may identify a better understanding of the team’s chosen approach.

The new protocol complexity process, therefore, drives simplification, enhances collaboration, and creates confidence in trial design. More effective communication across the Therapeutic Areas, Clinical Development, Operations, Regulatory, and Clinical Supply improves study planning, improves general awareness of key issues and accelerates governance approval [30]. For example, enhancement in communication clarifies delivery issues and site feasibility and improves engagement with key stakeholders. This is in contrast to the prior way of working, where the project team had many one-on-one dialogues that resulted in complex protocols that are typically more expensive and more difficult to execute. The PCT Complexity Tool can fit within the ecosystem of processes and tools that already exist to measure benefit and costs, linking directly with governance boards and patient insights, complementing workstreams and tools and study visualization processes. The expectation is that over the coming years and with further enhancements, timely PCT pass through will increase the likelihood of study success.

Limitations of our study included the relatively small number of studies assessed. Of those studies passed through the PCT, most fell within the respiratory and immunology therapeutic area and the majority were Phase III. Further research to assess the utility of the PCT is warranted in a larger sample size, including studies from a range of therapeutic areas and phases, and from other pharmaceutical companies.

Conclusions

Current protocol design process tended to deliver complex protocols that were expensive and difficult to execute, creating a demand for a tool that drives simplification, enhances collaboration, and creates confidence in trial design. To our knowledge, no tool that measures protocol complexity exists. We have developed and tested a standard set of questions, divided into 5 domains, permitting the quantification and visualization of protocol complexity. A pilot study exploratory analysis demonstrated a positive correlation of protocol complexity with both site activation and participant enrolment, suggesting robustness of the tool for complexity assessment, although additional tool validation is warranted (e.g. checking whether protocol simplification facilitates faster recruitment, etc.). The PCT was designed to be easy to use, self-instructive, and permitting visualization of where study complexities lie. It enabled cross-functional team discussions, thus aligning the study design before the plan is brought to governance. This process could be the standard approach to assess the complexity of clinical trial protocols across clinical studies and therapeutic areas. Over the coming years it is expected that further enhancements will be made that will lead to a further reduction of burden– the burden to our patients and burden to participating sites.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1. The collaborative design process. Additional file 2. author expertise. Additional file 3. Change in DCS and TCS post-PCT pass through. Additional file 4. Cost saving and cost avoidance estimates associated with protocol complexity tool implementation.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge Eleonor Fung, Lucy Southwell, Hitsh Pandya, Tim Harrisson, Marina Minou, Malin Aurell, Damian Zając, Sylwia Czarnomska, Natalie Fishburn, and Mene Pangalos, for their assistance in development of the Protocol Complexity ToolEditorial support was obtained from Dr Ruth B Murray, Medscript NZ Ltd.

Abbreviations

- DCS

domain complexity score

- PCT

protocol complexity tool

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- TCS

total complexity score

- TPP

target product profile

Authors’ contributions

BW: contributed to study design, data analysis and data interpretation. He directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript, created the first draft and reviewed subsequent drafts. AW: contributed to protocol complexity tool development. She contributed to and reviewed all draftsBP: contributed to protocol complexity tool development and data interpretation. He contributed to and reviewed all drafts. AP: contributed to study design and protocol complexity tool development. She contributed to and reviewed all drafts.CK: contributed to protocol complexity tool development. She contributed to and reviewed all drafts.GL: contributed to protocol complexity tool development and data collection. Contributed and reviewed all drafts.VP: contributed to protocol complexity tool development, training and implementation. She contributed to and reviewed all draftsIP: contributed to protocol complexity tool development. He contributed to and reviewed all drafts.All authors confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Funding

This study was funded by AstraZeneca.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors are employees of AstraZeneca and may or may not hold stock or stock options in the company.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Protocol design scope. And execution burden continue to rise, most notably in phase III. Turft center for the study of Drgu development impact report. 2023;25. https://csdd.tufts.edu/publications/impact-reports. [Last accessed 15 July 2025].

- 2.Markey N, Howitt B, El-Mansouri I, Schwartzenberg C, Kotova O, Meier C. Clinical trials are becoming more complex: a machine learning analysis of data from over 16,000 trials. Sci Rep. 2024;14:3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Culbertson J. Clinical trial duration trends and the study close out gap. 2022. https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/clinical-trial-duration-trends-the-study-closeout-gap-0001. [Last accessed 15 July 2025].

- 4.Getz KA, Campo RA. Trial watch: trends in clinical trial design complexity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun D, Gao W, Hu H, Zhou S. Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:3049–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones CW, Handler L, Crowell KE, Keil LG, Weaver MA, Platts-Mills TF. Non-publication of large randomized clinical trials: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman SJ, Shelton B, Mahmood H, Fitzgerald JE, Harrison EM, Bhangu A. Discontinuation and non-publication of surgical randomised controlled trials: observational study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha RA, Camm CF, Doganay E, Edison E, Siddiqui MRS, Orgill DP. Randomised controlled trials in plastic surgery: a systematic review of reporting quality. Eur J Plast Surg. 2014;37:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasenda B, von Elm E, You J, Blümle A, Tomonaga Y, Saccilotto R, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA. 2014;311:1045–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung KC, Malay S, Shauver MJ. The complexity of conducting a multicenter clinical trial: taking it to the next level stipulated by the federal agencies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:e1095-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith Z, Bilke R, Pretorius S, Getz K. Protocol design variables highly correlated with, and predictive of, clinical trial performance. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022;56:333–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brigante A, Russo B, Mongin D, Lauper K, Allali D, Courvoisier DS, et al. Extent of and reasons for discontinuation and nonpublication of interventional trials on connective tissue diseases: an observational study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2023;75:921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Easterbrook PJ, Matthews DR. Fate of research studies. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullati S, Courvoisier DS, Gayet-Ageron A, Haller G, Irion O, Agoritsas T, et al. Patient enrollment and logistical problems top the list of difficulties in clinical research: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie M, Gillen DL, Grill JD. Recruitment across two decades of NIH-funded Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrer S, Shah P, Antony B, Hu J. Artificial intelligence for clinical trial design. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40:577–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison RK. Phase II and phase III failures: 2013–2015. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:817–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graul AI, Dulsat C, Pina P, Cruces E, Tracy M. The year’s new drugs and biologics 2018: part II - News that shaped the industry in 2018. Drugs Today (Barc). 2019;55:131–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowden H, Munro J. Trends in clinical success rates and therapeutic focus. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:495–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graul AI, Pina P, Tracy M, Sorbera L. The year’s new drugs and biologics 2019. Drugs Today (Barc). 2020;56:47–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blazynski C, Runkel L. Completed trials: state of industry-sponsored clinical development. Report PharmaIntelligence Informa; 2019.

- 22.Deloitte Report. Be brave, be bold. Measuring return from pharmaceutical innovation. 15th edition. 2025. https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/articles/measuring-return-from-pharmaceutical-innovation.html [Last accessed 15 July 2025].

- 23.Gumber L, Agbeleye O, Inskip A, Fairbairn R, Still M, Ouma L, et al. Operational complexities in international clinical trials: a systematic review of challenges and proposed solutions. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e077132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shadbolt C, Naufal E, Bunzli S, Price V, Rele S, Schilling C, et al. Analysis of rates of completion, delays, and participant recruitment in randomized clinical trials in surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2250996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alphs LD, Bossie CA. ASPECT-R-a tool to rate the pragmatic and explanatory characteristics of a clinical trial design. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13:15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smuck B, Bettello P, Berghout K, Hanna T, Kowaleski B, Phippard L, et al. Ontario protocol assessment level: clinical trial complexity rating tool for workload planning in oncology clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:80–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willigers BJ, Nagarajan S, Ghiorghui S, Darken P, Lennard S. Algorithmic benchmark modulation: a novel method to develop success rates for clinical studies. Clin Trials. 2023. 10.1177/17407745231207858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E6_R2_Addendum.pdf [Last accessed 15 July 2025].

- 29.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehrotra S, Gobburu J. Communicating to influence drug development and regulatory decisions: A tutorial. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2016;5:163–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peikert A, Martinez FA, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Kulac IJ, Desai AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction according to age: the DELIVER trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2022;15:e010080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Byrne PM, Metev H, Puu M, Richter K, Keen C, Uddin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of a CXCR2 antagonist, AZD5069, in patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin MJ, Ustianowski A, De Wit S, Launay O, Avila M, Templeton A, et al. Intramuscular AZD7442 (Tixagevimab-cilgavimab) for prevention of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heerspink HJL, Kiyosue A, Wheeler DC, Lin M, Wijkmark E, Carlson G, et al. Zibotentan in combination with dapagliflozin compared with dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease (ZENITH-CKD): a multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, phase 2b, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023;402:2004–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1. The collaborative design process. Additional file 2. author expertise. Additional file 3. Change in DCS and TCS post-PCT pass through. Additional file 4. Cost saving and cost avoidance estimates associated with protocol complexity tool implementation.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.