Abstract

Periodontitis is an infectious disease caused by plaque-associated microorganisms. The condition is characterized by the activation of oxidative stress and immune responses, which contribute to tissue destruction. Carbon monoxide (CO)-based gas therapy, utilizing CO releasing molecules (CORMs), presents a promising therapeutic strategy; however, its efficacy is constrained by the short half-life and limited cellular uptake of CORMs. In this study, metal-phenolic networks (MPN) were employed as a carrier to stabilize CORMs via metal-ligand coordination, thereby forming a nanocomplex designated as CO@MPN. This nanocomplex demonstrated effective scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and exhibited ROS-responsive CO release. Following phagocytosis by macrophages, CO@MPN significantly decreased intracellular ROS levels, reduced the production of inflammatory factors in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages, facilitated macrophage polarization towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, and activated heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) to further attenuate inflammation. In murine models of experimental periodontitis, CO@MPN significantly inhibited inflammatory bone loss and exerted macrophage-regulating effects. The findings underscore the potential of ROS-responsive CO gas therapy as a promising strategy for the treatment of periodontitis and the management of other inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Metal phenolic network, Carbon monoxide releasing molecules-3, Macrophage, Reactive oxygen species, Periodontitis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

CO@MPN nanocomplex stabilized CORMs via metal-phenolic networks.

-

•

CO@MPN demonstrates effective scavenging of ROS and exhibits ROS-responsive CO release.

-

•

CO@MPN suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines, and promotes M2 macrophage polarization via HO-1 activation.

-

•

In murine periodontitis, CO@MPN significantly inhibited inflammatory bone loss.

1. Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic infectious disease characterized by the progressive destruction of periodontal supporting tissues, primarily initiated by plaque microorganisms [1]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and macrophages play significant roles in this pathological process [2]. Upon bacterial invasion of periodontal tissues, immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages generate a respiratory burst via the respiratory chain metabolic pathway to eradicate the bacteria [3,4]. This process results in the release of ROS, including superoxide anions, into phagosomes and the extracellular environment [5], leading to an increased expression of inflammatory mediators within the tissue and the excessive production of ROS, which contributes to periodontal tissue damage [6,7]. Additionally, macrophages constitute a crucial component of the innate immune response, serving as a primary defense mechanism against microbial invasion and infection. During the progression of periodontitis, M1-type macrophages are involved in bactericidal activities and antigen presentation, although they also contribute to collateral damage to surrounding tissues [[8], [9], [10]]. In contrast, during the healing phase of periodontitis, there is an increase in the proportion of M2-type macrophages, which inhibit osteoclastic activity and pro-inflammatory factor secretion, thereby promoting tissue repair [11,12]. Consequently, the restoration of oxidative homeostasis and the modulation of immune responses are considered crucial strategies in the treatment of periodontal disease [13,14].

Previous studies have demonstrated that low concentrations of carbon monoxide (CO) exhibit anti-inflammatory [15] and vasodilatory properties [16]. Furthermore, CO has been shown to mitigate ischemia-reperfusion injury and acute organ damage [17,18], possess antibacterial activity [19], and inhibit tumor progression [20]. Notably, it can suppress the expression of inflammatory factors, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and inhibit osteoclast formation in the context of periodontitis, while also promoting osteogenic differentiation [21]. As an innovative gaseous therapeutic approach, CO has the potential to synergistically modulate the immune microenvironment for the treatment of diabetic periodontitis [22]. CO releasing molecules-3 (CORM-3), which serves as exogenous sources of CO, facilitates the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and inhibits the release of inflammatory cytokines in human periodontal ligament cells stimulated by lipopolysaccharide [23]. Additionally, CORM-3 has demonstrated significant potential in treating periodontal disease by inhibiting the expression of adhesion molecules in human gingival fibroblasts induced by inflammatory factors, thereby reducing the infiltration and adhesion of immune-active cells [24]. However, its rapid release rate (t1/2 ≈ 1 min) and low cellular uptake (0.018 %) pose significant limitations to its application [25,26]. To address these challenges and achieve targeted CO delivery with controlled release, various carriers, including peptides, ferritin cages, and polymeric micelles, have been investigated [27,28]. Polymeric micelles are synthesized through a complex process, and while iron oxide-loaded nanoparticles can induce material aggregation within cells for tumor cell eradication, they are not suitable for treating inflamed tissues. To enhance the applicability of CORM-3 in the therapeutic context of periodontal inflammation, the development of a simpler and more efficient CORM-3 nanocarrier is necessary.

Metal-phenolic networks (MPN) constitute a class of coordination-driven supramolecular structures formed through the spontaneous self-assembly of polyphenols with diverse metal ions [29]. The assembly process occurs rapidly under ambient conditions, such as room temperature stirring, offering significant advantages for formulating bioactive coatings. Specifically, the mild synthesis parameters readily accommodate the integration of thermally labile cargos while preserving their bioactivity [30]. MPN enable the encapsulation of therapeutics across a broad molecular weight spectrum. The coordination-based network effectively allows stimuli-responsive drug release-triggered by ROS or pH variations [30,31]. Beyond their utility as coating materials, MPN exhibit inherent biological compatibility and possess multifaceted therapeutic properties, including potent antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities [32,33]. This functional synergy has positioned MPN as promising active coating systems for diverse biomedical applications [30,31,34].

In this study, MPN were utilized as ROS-responsive carriers for CORM-3 in the context of CO gas therapy for periodontitis. The CO@MPN nanoparticles were synthesized through a one-step self-assembly process involving metal-phenolic coordination. Upon administration to inflamed tissues, these nanoparticles were internalized by macrophages via endocytosis. The elevated ROS levels trigger the dissociation of the MPN, resulting in the intracellular release of CO. Consequently, these nanoparticles effectively inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory factors while promoting the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines. This modulation of macrophage polarization significantly mitigates tissue damage typically associated with periodontal inflammation (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Metal-phenolic encapsulation of CO releasing molecules for gas therapy of periodontitis.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Fabrication and Characterization of CO@MPN

CO@MPN nanoparticles were synthesized utilizing a revised “one-pot” method [35]. In this process, an aqueous solution of tannic acid (TA), FeCl3, polyethylene glycol (PEG, MW = 400), and CORM-3 was continuously stirred in deionized water at ambient temperature, resulting in self-assembly of CO@MPN nanoparticles (Fig. 1A). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging revealed that CO@MPN exhibited a spherical nanoparticle morphology with an approximate diameter of 150 ± 4.37 nm (Fig. 1B and C). In contrast to the pristine MPN particles, the TEM image of CO@MPN particles exhibited a distinct membrane-like coating on their surface. This morphological variation is likely attributable to the encapsulation of CORM-3 molecules within the MPN framework. Elemental mapping images demonstrated homogeneous ruthenium (Ru) distribution, indicating the effective loading of CORM-3 (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Fabrication and Characterization of CO@MPN. (A) Schematic diagram of the synthesis of CO@MPN. (B) SEM image of CO@MPN (scale bar: 500 nm). (C) TEM image of CO@MPN (scale bar: 100 nm). (D) EDS elemental mapping of CO@MPN. (E) FTIR absorption spectra of PEG, MPN, CORM-3, CO@MPN, illustrating the constituent components of CO@MPN; (F) Expression intensity of characteristic peaks in CO@MPN synthesized with varying proportions of CORM-3:TA in FTIR absorption spectra. (G) Zeta potentials and (H) Hydrodynamic sizes of MPN and CO@MPN. (I) UV/vis absorption spectrum of MPN, CORM-3 and CO@MPN. (J) Drug loading and encapsulation rates of CO@MPN at different mass ratios of CORM-3 to TA.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy results showed that both CORM-3 and CO@MPN contained carbonyl (C=O) bands at 1985 cm−1 and 2058 cm−1 (Fig. 1E), confirming the successful incorporation of CO into the MPN network [36]. Notably, the intensity of these characteristic peaks increased with higher CORM-3 content (Fig. 1F).

The diameter and zeta potential of CO@MPN were analyzed using a Malvern particle size analyzer. The CORM-3 loading retained the surface charge characteristics, as evidenced by the nearly identical zeta potential (Fig. 1G). Quantitative dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis confirmed the uniform colloidal properties of the two systems. The hydrodynamic diameter of MPN was 123 ± 5.23 nm (PDI = 0.16), while that of CO@MPN is 297 ± 8.75 nm (PDI = 0.181), confirming CORM-3 incorporation-induced particle expansion. A PDI value below 0.3 corroborates excellent dispersion stability and a negligible risk of aggregation (Fig. 1H). To validate our hypothesis concerning the loading of CORM-3, we employed UV–Vis spectrophotometry. The MPN UV spectrum revealed a broad peak within the 500–650 nm range, which was attributed to the Ligand-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) band involving tannic acid (TA) and Fe III. In comparison, the UV spectrum of CO@MPN demonstrated a positional shift in this broad peak relative to the MPN spectrum (Fig. 1I). This shift corresponded with the UV band observed in the CORM-3-TA solution (Fig. S1), thereby confirming the coordination between Ru in CORM-3 and TA [37]. This coordination facilitated the incorporation of CORM-3 into the MPN network. To investigate further, we synthesized various mass ratios of CO@MPN and employed Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) to quantify the Ru content. Subsequently, we calculated the loading and encapsulation efficiencies (Fig. 1J). The optimal CORM-3:TA ratio of 8:1 demonstrated high loading and encapsulation efficiencies, along with an appropriate drug amount, and was thus selected for subsequent experiments.

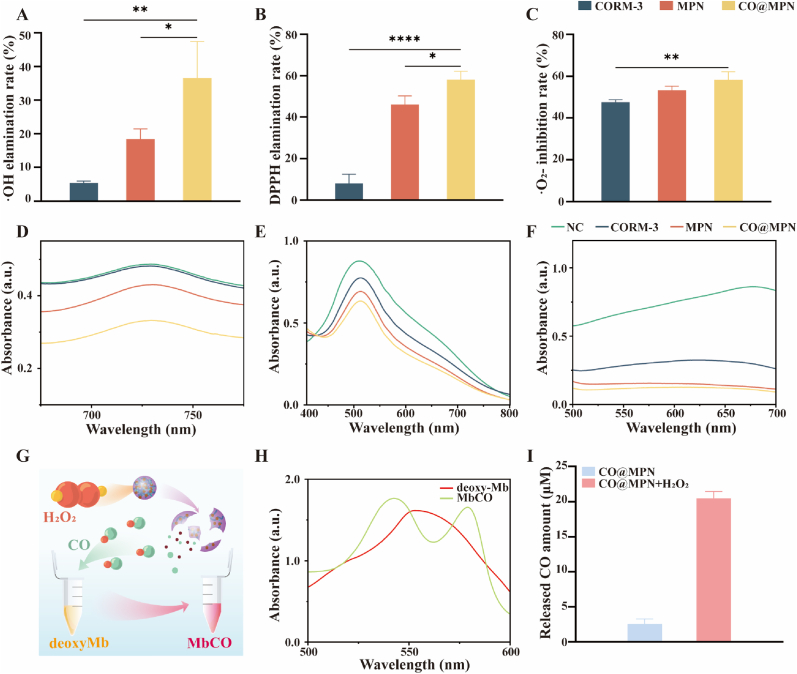

2.2. The ability of ROS scavenging and CO@MPN to release CO

We assessed the ROS scavenging capabilities of CORM-3, MPN, and CO@MPN. The findings revealed that CO@MPN exhibited the highest scavenging efficiency for radicals such as superoxide anion (·O2−) (Fig. 2A–D), DPPH (Fig. 2B–E), and hydroxyl radical (·OH) (Fig. 2C–F) when compared to CORM-3 and MPN at equivalent concentrations. Notably, MPN showed significant activity against DPPH and ·OH, whereas CORM-3 was more effective in scavenging ·O2− (Fig. 2A–F). Additionally, Fig. S2 illustrated the colorimetric changes in the solution corresponding to varying ROS scavenging rates.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of free radical scavenging ability and ROS-induced CO release of CO@MPN. The percentage of radical scavenging of as-prepared CO@MPN toward (A) ·OH, (B) DPPH, and (C)·O2− radicals (n = 3). UV/vis absorption spectra of (D) ·OH, (E) DPPH, and (F) ·O2− radical scavenging by CO@MPN (n = 3). (G) Schematic diagram of CO@MPN stimulated by hydrogen peroxide to release CO, causing deoxy-Mb to bind CO to form MbCO. (H) UV/vis absorption spectra of deoxy-Mb and MbCO. (I) CO release from CO@MPN in different environments (n = 3). All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. P-values are assessed by a one-way ANOVA analysis and marked as asteroids. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

The myoglobin assay is a traditional technique employed to detect CO release [38]. In this assay, myoglobin (Mb) is oxidized by sulfite to form deoxy-myoglobin (deoxy-Mb), which has a high affinity for CO. Specifically, 1 mol of deoxy-Mb binds with 1 mol of CO to produce MbCO (Fig. 2G), a transformation that can be monitored through changes in the UV–visible spectrum (Fig. 2H) [39]. To evaluate the efficacy of CO release from CO@MPN in response to ROS [40], we subjected CO@MPN to solutions simulating the oxidative stress associated with periodontal inflammation, both in the presence and the absence of H2O2. Using the myoglobin assay, we measured the absorbance change at 540 nm to calculate the concentration of MbCO, thereby determining the amount of CO released. The results demonstrated minimal CO release from CO@MPN in the absence of H2O2, whereas a significant increase in CO concentration was observed upon the addition of H2O2 (Fig. 2I). This suggests that CO@MPN facilitates enhanced CO release under oxidative stress conditions.

2.3. Intracellular delivery of CO@MPN

To examine the antioxidative capacity within cells, CO@MPN was co-cultured with macrophages. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, CORM-3 alone has limited therapeutic efficacy due to its low cellular availability. In contrast, CO@MPN can penetrate cells, facilitating intracellular CO release and ROS scavenging. Initially, cytotoxicity assays were performed using Raw264.7 cells to determine the optimal concentration of CO@MPN. As shown in Fig. 3B, CO@MPN demonstrated minimal cytotoxicity. Moreover, at a concentration of 40 μg/mL, it slightly promoted cell proliferation. Consequently, this concentration was selected for subsequent experiments. To explore the interaction between macrophages and CO@MPN, the nanoparticles were labeled with FITC-conjugated BSA. Upon introduction, CO@MPN initially adhered to and aggregated around the cells. Over time, some particles were observed intracellularly (Fig. 3C), suggesting that macrophages can internalize nanoparticles via phagocytosis [41,42]. Given the potent free radical scavenging ability of CO@MPN, we stimulated macrophages into an inflammatory state using lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Both flow cytometry (Fig. 3D and E) and laser confocal microscopy (Fig. 3F) demonstrated increased levels of ROS in the LPS-stimulated macrophages. However, the simultaneous addition of equivalent amounts of CORM-3, MPN, and CO@MPN resulted in a reduction of ROS levels in the LPS-stimulated macrophages. Importantly, CO@MPN showed a markedly superior capacity for ROS clearance compared to the other groups.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of Cytotoxicity, Colocalization, and Anti-Oxidative Stress of CO@MPN in Vitro. (A) Effect of CO@MPN on ROS in macrophages. (B) CCK-8 assay of Raw 264.7 cells incubated with different concentration of CO@MPN after 12, 24 and 48 h, respectively. (C) Laser confocal microscopy images of BSA-FITC-labeled CO@MPN co-incubated with Raw 264.7 cells after 6, 12 and24 h (green indicates CO@MPN labeled with FITC, red denotes cell membranes stained with Dil, and blue represents cell nucleus). (D) Flow cytometry of ROS levels in Raw 264.7 cells under different treatment conditions. (E) Percentage clearance of ROS in each experimental group. (F) Representative fluorescent images of the intracellular ROS in Raw 264.7 cells after different treatments. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. P-values are assessed by a one-way ANOVA analysis and marked as asteroids. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

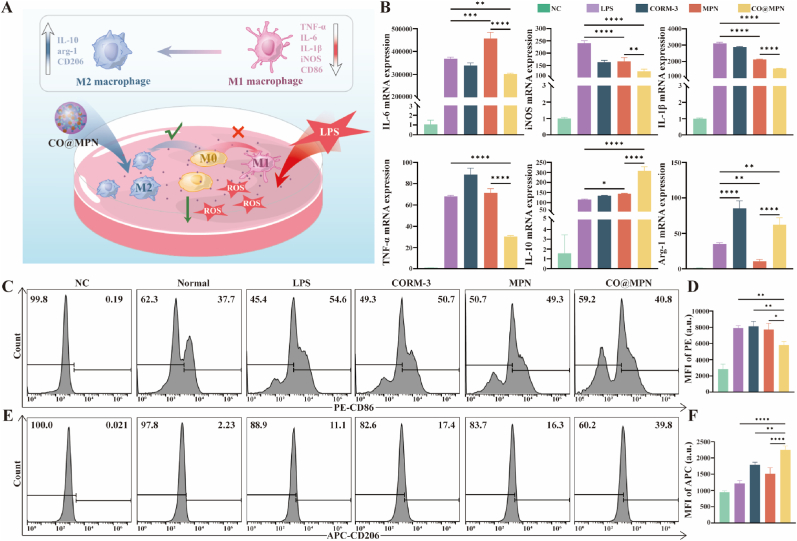

2.4. Immunomodulatory Effect of CO@MPN in vitro

Given the antioxidant properties of CO@MPN, we utilized quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR) to evaluate cellular inflammatory factors, thereby determining its anti-inflammatory effects (Fig. 4A). M1 macrophages, recognized as pro-inflammatory functions, produce interleukin-6 (IL-6), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Conversely, anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages are distinguished by their secretion of arginase-1 (arg-1) and IL-10 [43,44]. Following exposure to 1 ng/mL LPS for 24 h, the macrophages demonstrated an upregulation of inflammatory factors typical of both M1 and M2 phenotypes. Notably, CO@MPN more effectively inhibited M1-associated factors compared to MPN or CORM-3 alone, which facilitated the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α. Furthermore, CO@MPN enhanced the expression of M2-associated factors, particularly IL-10, although it exhibited a slightly reduced upregulation of arg-1 compared to CORM-3 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Immunomodulatory Effect of CO@MPN in Vitro. (A) Effect of CO@MPN on macrophage polarization. (B) The mRNA expression levels of M1 markers (IL-6, iNOS, IL-1β, and TNF-α) and M2 markers (IL-10 and arg-1) determined by qPCR assay. (C) Flow cytometry of CD86 expression levels in Raw 264.7 cells under different treatment conditions. (D) Flow cytometry of CD206 expression levels in Raw 264.7 cells under different treatment conditions. (E) Mean fluorescence intensity of PE-CD86 in flow cytometric assays. (F) Mean fluorescence intensity of APC-CD206 in flow cytometric assays. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. P-values are assessed by a one-way ANOVA analysis and marked as asteroids. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Flow cytometry was utilized to determine the impact of CO@MPN on macrophage polarization by analyzing the expression levels of proteins associated with M1 and M2 phenotypes. CD86 is identified as a marker for M1 macrophages, whereas CD206 serves as a marker for M2 macrophages [45]. LPS-stimulated macrophages were employed as a positive control. In comparison to the control group, both MPN and CORM-3 individually exhibited minimal downregulation of CD86 (Fig. 4C and D) and slight upregulation of CD206 (Fig. 4E and F). In contrast, CO@MPN demonstrated significantly more pronounced effects. Consequently, CO@MPN demonstrated a superior capacity to modulate macrophage polarization and augment anti-inflammatory responses.

Subsequently, we explored the mechanism through which CO@MPN influences macrophage polarization. CO primarily mediates intracellular physiological effects via three pathways: inducing heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression, activating guanylate cyclase, and modulating p38 MAPK phosphorylation [46]. By interacting with HO-1, CO attenuates inflammation-associated signaling pathways and modulates macrophage polarization [47]. Supporting this mechanism, previous studies have shown that CORM-3 exerts anti-inflammatory effects on TNF-α and IL-1β-stimulated human gingival fibroblasts through the HO-1 pathway [25]. Consequently, we evaluated HO-1 expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages treated with varying concentrations of CORM-3 using Western blot analysis. Baseline HO-1 expression was constitutively low in the absence of LPS stimulation. However, co-treatment with LPS and CORM-3 resulted in a significant, concentration-dependent increase in HO-1 levels (Fig. 5A and B), thereby corroborating previous findings [48]. In the assessment of CO@MPN components under inflammatory conditions, it was observed that neither CORM-3 nor MPN independently triggered the activation of HO-1. Notably, CO@MPN significantly enhanced this response (Fig. 5C and D). These findings suggest that the encapsulation of CORM-3 within MPN facilitates a controlled intracellular release, resulting in an increased upregulation of HO-1. Therefore, we propose that CO@MPN influences macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype by upregulating intracellular HO-1 expression, subsequently suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Fig. 5.

Activation HO-1 in LPS-induced macrophages. (A–B) Protein expression levels of HO-1 in Raw 264.7 after incubated with different concentration of CORM-3 determined by Western blotting. (C–D) Protein expression levels of HO-1 in Raw 264.7 after incubated with different treatments determined by Western blotting. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3. P-values are assessed by a one-way ANOVA analysis and marked as asteroids. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

2.5. Therapeutic Effect of CO@MPN on periodontitis mice

To evaluate the in vivo therapeutic potential of CO@MPN, a periodontitis mouse model was established using silk ligation followed by LPS injection, as illustrated in Fig. 6A. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) analysis of the mouse maxilla (Fig. 6B) demonstrated significant reductions in the alveolar ridge height at the proximal and distal mesio-buccal regions of the maxillary second molar across all experimental groups, with the exception of blank group. Two-dimensional cross-sectional images revealed indistinct alveolar ridge tops and decreased bone density, indicative of pronounced resorption. Quantitative measurement and statistical analysis of the distance from the distal mesial alveolar ridge top to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) showed that the CO@MPN group experienced significantly less bone resorption compared to other experimental groups (Fig. 6C); along with increased bone volume fraction and trabecular thickness (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Therapeutic Effect of CO@MPN on Periodontitis Mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the process of modeling periodontitis mice. (B) Three-dimensional reconstruction and cross-section of the mouse maxilla. (C) Quantitative analysis of bone resorption of the maxillary second molar in mice. (D) Analysis of the alveolar bone density of the maxillary second molar in mice. (E) H&E staining images of the maxillary second molar in mice. (F) Immunohistochemical staining of iNOS and CD206. (G) Percentage of iNOS expression in tissue sections. (H) Percentage of CD206 expression in tissue sections. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 6. P-values are assessed by a one-way ANOVA analysis and marked as asteroids. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining indicated continuity between the sulcus epithelium and the junctional epithelium in the control group, characterized by a gingival sulcus base adjacent to the CEJ, normal collagen fiber morphology, and minimal alveolar bone resorption. In contrast, the remaining three groups exhibited disruption of the gingival epithelium, displacement of the gingival sulcus base, fragmentation of collagen fibers, significant resorption of alveolar bone, a reduction in bone height. Notably, within the experimental cohorts, the CO@MPN group displayed significantly less bone resorption and the mildest epithelial destruction (Fig. 6E). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed a significant increase in iNOS expression in the LPS group compared to the NC group, alongside a modest rise in CD206 expression. This finding suggests that macrophages in periodontal inflammation predominantly polarize towards the M1 phenotype. The CO@MPN group notably exhibited a more pronounced downregulation of M1-associated iNOS and an upregulation of M2-associated CD206 relative to other experimental groups, aligning with our previous in vitro findings (Fig. 6F–H). Macrophage phenotypic polarization is pivotal for periodontal tissue regeneration. During the initial healing phase, M1 macrophages are vital for defense including phagocytosing microbes and debris. However, their activation also contributes to inflammation, immune modulation, and leads to bone resorption if prolonged. In contrast, M2 macrophages promote tissue repair, regeneration, and inflammation resolution [49]. Therefore, an increased M1/M2 ratio within the periodontal milieu is identified as a significant contributor to alveolar bone resorption. The CO@MPN formulation employed in this study exhibits immunomodulatory capabilities, as it effectively inhibits the activation of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages while simultaneously promoting the expression of pro-reparative M2 macrophages. The alteration of macrophage phenotypic balance represents a crucial mechanism through which CO@MPN markedly enhances the regeneration and repair of periodontal tissues.

Furthermore, H&E staining of tissue sections from vital organs (including heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys) demonstrated preserved histo-cellular architecture, thereby highlighting the favorable histocompatibility of CO@MPN (Fig. S3). A straightforward one-pot method synthesizes CO@MPN , enabling operational simplicity and scalable production. Although this gas therapy-based approach shows promising therapeutic efficacy in experimental models of periodontitis, future research is necessary to confirm its clinical benefits by employing key periodontal indices, such as probing depth, gingival bleeding index, and clinical attachment level. Comprehensive long-term biosafety evaluations are crucial for CO@MPN.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we developed a ROS-responsive CO gas nanosystem for the treatment of periodontitis. CORM-3 was effectively encapsulated within the MPN through intermolecular interactions, achieving ROS-mediated CO release to maximize therapeutic CO bioavailability. The nanoparticles exhibited excellent immunomodulatory and ROS scavenging functions, demonstrating a significant capacity to inhibit inflammatory tissue loss associated with periodontitis. In conclusion, this study introduces a straightforward and promising oxidative stress-responsive CO nanocarrier system, offering valuable insights for gas therapy applications in periodontitis and other inflammatory diseases.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Synthesis of MPN and CO@MPN

MPN and CO@MPN were prepared through one-pot assembly. In the preparation of the sample, the process began with the addition of 50 μL of a 5 mg/mL FeCl3·6H2O solution (HEOWNS, Tianjin, China), followed by 200 μL of a 5 mg/mL TA solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A). These were then supplemented with 1.55 mL of deionized water and 200 μL of PEG 400 (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The resultant mixture was subjected to magnetic stirring at a speed of 600 rpm, maintained at room temperature for a duration of 30 min. Upon completion of the stirring process, the sample was carefully transferred into an EP tube and centrifuged at 8000×g for 10 min using a high-speed centrifuge (Heraeus, Germany), with the operation conducted at room temperature. Pour off the supernatant. Add deionized water, resuspend and disperse by ultrasonication (SCIENTZ, China), centrifuge again at 8000×g for 10 min, discard the supernatant, lyophilized for 12 h, weighed and stored at −4 °C. The steps for the synthesis of CO@MPN were the same as those described above, except for the addition of CORM-3 (Macklin, Shanghai, China) in the first step of adding the solution in an extra step.

4.2. Characterization of CO@MPN

To quantify the Ru content, 2.1 mg of lyophilized CO@MPN powder was dissolved in 4 mL of aqua regia and subsequently diluted to a total volume of 50 mL. The concentration of Ru was determined using ICP-MS (Nexion 350X, PerkinElmer, U.S.A.), which facilitated the calculation of the corresponding CORM-3 content for assessing drug loading efficiency and entrapment efficiency. FTIR spectroscopy was then conducted using an ALPHA II spectrometer (Bruker, MA, USA). Following background subtraction, samples of PEG, MPN, CORM-3, and CO@MPN were placed on the sample stage. FTIR absorption spectra were acquired and analyzed using Origin software, with a focus on characteristic peaks such as carbonyl vibrations. For UV–Vis absorption analysis, solutions of MPN, CO@MPN, and CORM-3 at equivalent concentrations were prepared and transferred to quartz cuvettes. Spectra ranging from 250 to 800 nm were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-2600i spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan). Finally, DLS measurements were conducted. Freshly prepared aqueous solutions (0.1 mg/mL) of lyophilized MPN and CO@MPN powders were loaded into a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSE instrument (Malvern, U.K.) to determine hydrodynamic size and zeta potential.

For the SEM analysis, a titanium sheet was securely mounted onto the sample stage using adhesive tape. 1 mg/mL CO@MPN aqueous solution was then carefully pipetted and applied dropwise onto the titanium sheet, allowing it to air-dry at room temperature. Once dried, the surface was uniformly coated with a thin layer of gold to enhance conductivity. Subsequently, the topographical features of the MPN and CO@MPN nanoparticles were thoroughly examined under a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Phenom, U.S.A.), providing detailed insights into their surface morphology. Besides, the photographs were taken. A piece of copper mesh was placed on the filter paper and a trace amount of 0.1 mg/mL sample solution was added dropwise upwards. After IR drying, the internal structure of the particles of CO@MPN was observed under a JEM-2100 TEM microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed.

4.3. Free radical elimination

Mix H2O2 and FeSO4 (Aladdin, Shanghai, China), solutions in deionized water to achieve 0.5 mM and 0.72 mM concentrations, respectively. Sonicate for 10 min, distribute into 4 EP tubes, and add deionized water, CORM-3, MPN, and CO@MPN to each. Centrifuge at 8000 ×g for 10 min, transfer supernatants to fresh EP tubes, and add 50 μM [ = 2,2′-Azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic Acid Ammonium Salt)] (ABTS, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) solution. Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 5 min. Measure absorbance at 600–850 nm with a UV spectrophotometer, specifically at 730 nm using a microplate reader, and calculate ·OH clearance rate.

In the experimental setup, 1 mL of a 0.1 mM 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) solution in ethanol (Macklin, Shanghai, China) was introduced into each of the four bottles. The last three bottles were further supplemented with CORM-3, MPN, and CO@MPN, respectively. After allowing the mixtures to stand at room temperature for 1 h, the contents were carefully transferred to EP tubes. The tubes were then subjected to centrifugation at 8000×g for 10 min, following which the supernatants were meticulously collected. Spectrophotometric analysis was conducted to measure the absorbance across a wavelength range of 300–800 nm using a UV spectrophotometer. For specific quantification, the absorbance at 570 nm was also assessed with a microplate reader, facilitating the subsequent calculation of the DPPH clearance rate.

Five bottles were each added 200 μL riboflavin (0.1 mM in PBS), 125 μL L-methionine (100 mM in PBS), and 105 μL nitro tetrazolium blue chloride (NBT, 0.5 mM in DMF) (Macklin, Shanghai, China). CORM-3, MPN, and CO@MPN were individually supplemented to the last three bottles, with PBS bringing each to 1 mL. After UV irradiation for 1 h (excluding the first group), liquids were transferred to EP tubes. Supernatants were isolated via centrifugation, and ·O2− inhibition rates determined by absorbance measurements at 500–700 nm on a UV spectrophotometer and specifically at 560 nm using a microplate reader.

4.4. Detection of CO release

To investigate the CO release from CO@MPN, we utilized the well-established myoglobin assay. We began by mixing myoglobin (200 μM) (Mb; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A) with Na2S2O4 (2.4 mg/mL) (Macklin, Shanghai, China), followed by a 10-min sonication at room temperature (RT) to produce deoxy-Mb. The baseline absorbance at 540 nm, recorded as A0, was then measured using a UV–vis spectrophotometer. To proceed, we added an excess of 10 mg/mL CORM-3 to the deoxy-Mb solution and allowed the mixture to react at RT for 20 min, enabling the conversion of deoxy-Mb to MbCO. UV–vis spectrophotometry was used to record the UV spectra at 500–600 nm of deoxy-Mb, and MbCO, respectively. After reduction of Mb to deoxy-Mb solution according to the above method. A CO@MPN solution with a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL was prepared and added to the reaction mixture, which was then incubated at room temperature for 20 min, with the reaction being carried out both in the presence and absence of H2O2. The absorbance at 540 nm was subsequently measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer, with the 0.1 mg/mL CO@MPN solution serving as the background. The recorded value was designated as A1. The concentration C(MbCO) of MbCO was calculated according to the following equation [37].

| (1) |

ε540 nm is 15.4 mM−1 cm−1 l is the optical range 1 cm and C0(deoxy-Mb) is the initial myoglobin solution concentration 200 μM.

4.5. Cell culture

The National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China) supplied the Raw 264.7 macrophage cell line. Grown in complete medium (DMEM, High-glucose, XP biomed, Shanghai, China) containing 10 % FBS (EvaCell, Suzhou, China) and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin (Ps, Gibco, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.), and placed in a 37 °C incubator with 5 % CO2 (Binder, Germany). When the cell density hit 70 %–80 %, the cells were viewed under a microscope and then passaged.

4.6. Cytotoxicity assays

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of CO@MPN, an in vitro CCK-8 assay (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was conducted. Raw 264.7 cells, at a density of 104 per well, were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 12 h. Subsequently, the medium was replaced with a pre-prepared solution containing 0–100 μg/mL of CO@MPN. Following an incubation period of 1–3 days, each well received 100 μL of CCK-8 solution, which was prepared as 10 % reagent in serum-free medium. The plates were then incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 1.5 h. Subsequently, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader, and the relative cell activity was calculated, with the control group's activity normalized to 100 %.

4.7. Co-localization of CO@MPN

CO@MPN (1 mg/mL) was mixed with BSA/FITC (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at a 40:1 vol ratio, stirred for 10 h in the dark, and washed twice. Raw 264.7 cells (2.4 × 105/well) were seeded in a 24-well plate for 12 h, with a 14-mm cell crawler in each well. Upon completion of the incubation period with 150 g/mL CO@MPN-FITC and 1 ng/mL LPS for designated intervals of 6, 12, or 24 h, the wells were subsequently treated with 500 μL of a 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (Dil, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) working solution, prepared by diluting Dil in PBS at a ratio of 1:1000. This treatment was conducted for 30 min at 37 °C in a dark environment, followed by a thorough washing process consisting of two rinses with PBS. Add 500 μL of Hoechst 33342 working solution (Hoechst 33342:medium = 1:1) (Biosharp, Guangzhou, China) to each well, and wash twice after dark reaction at 37 °C for 20 min. The cell crawls were taken out and placed on slides with anti-fluorescence attenuator, and observed and photographed using a laser confocal microscope (FV3000, OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan.).

4.8. Evaluation of intracellular ROS elimination

To investigate the effects of CORM-3, MPN, and CO@MPN on Raw 264.7 cells, we began by seeding the cells at a density of 6 × 105 per well into 6-well plates. After allowing them to adhere for 12 h, we treated the cells with the respective compounds in complete medium for 24 h. Subsequently, we stimulated the cells with 1 ng/mL LPS (Solarbio, Beijing, China) to induce inflammation. To measure ROS production, we then added a DCFH-DA working solution (1.5 mL per well) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Following this, we performed three rounds of washing and resuspended the cells in 500 μL of PBS for fluorescence microscopic analysis (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For further analysis, we harvested 2 × 106 cells from each group into EP tubes after the 24-h drug incubation. We centrifuged the tubes at 1200 rpm for 5 min to remove supernatants. As a negative control, we resuspended cells in 500 μL of PBS. For the experimental groups, we resuspended cells in 200 μL of DCFH-DA working solution (DCFH-DA: serum-free medium 1:1000), incubated at room temperature for 20 min, washed thrice, and finally resuspended in 500 μL of PBS. All samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry (Accuri-C6, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lake, New Jersey, U.S.A.).

4.9. qRT-PCR assay

Cells lysed, and total RNA extracted with RNAzol® RT Reagent. RNA concentration assessed by Nanodrop. RNA reverse transcribed to DNA using SPARK script Ⅱ RT superMix (Cisco Jet, China). Amplification mixture comprised 1 μL DNA, 0.2 μL each of pre- and post-primers (0.2 μM), 5 μL SYBR Green (2×), and 3.6 μL RNase H2O per 10 μL system. Amplification performed on Real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (Roche, Swiss) using a two-step protocol: 94 °C for 3 min, After the initial denaturation, 40 cycles of 10s at 94 °C and 30s at 60 °C were carried out. To determine the expression levels of the target gene, we first extracted the Ct values from the PCR curves. Using these Ct values, we then calculated the relative expression levels by applying the 2−ΔΔCt method. For accurate comparison, the expression levels of various genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. The specific primers utilized in our experiments are detailed in Table S1.

4.10. Flow cytometry

Performed preliminary operations as described. Collected 2 × 106 cells/tube in pre-cooled PBS. Added 100 μL blocking solution (Fc blocker:PBS = 1:200) (TruStain FcX™ PLUS (anti-mouse CD16/32) Antibody, Biolegend, San Diego, CA.U.S.A.) to each, incubated on ice in dark for 10 min. Rinsed, then added 100 μL PE anti-mouse CD86 Antibody (1:200 in PBS) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA.U.S.A.), Following a 60-min incubation at room temperature in darkness, the sample underwent three rinses and was then assessed with flow cytometry. For APC-CD206 staining (Biolegend, San Diego, CA.U.S.A.), post cell sealing, added 200 μL fixative (Elabscience, Wu Han, China) and 200 μL PBS, fixed cells for 60 min at room temp in dark. Added 1 mL membrane permeabilizer (Elabscience, Wu Han, China), centrifuge after 5 min of reaction, discarded supernatant. Continued staining with APC-CD206 solution, following steps identical to PE-CD86 staining.

4.11. Western blot analysis

The cell culture protocol was maintained uniformly throughout the experiment. Each well was rinsed three times with PBS, after which 200 μL of chilled lysate (PMSF: RIPA = 1:100) (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added. The mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min before being transferred to EP tubes. To enhance lysis, the tubes were shaken for an additional 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was then collected and transferred to a new EP tube. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and was adjusted with SDS-PAGE Sample Loading Buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and PBS for further analysis. Proteins were heated at 100 °C for 5 min, loaded into precast gel channels (4–20 %, 15-well, elife, China) alongside markers, and electrophoresed at 120 V for 1 h. In our Western blot procedure, we utilized PVDF membranes (0.45 m, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for the protein transfer, which was conducted at a steady current of 400 mA over a duration of 30 min. Once the transfer was complete, we proceeded to block the membranes using skimmed milk (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for a 1-h period at room temperature, with continuous shaking to ensure even coverage. The blocked membranes were then subjected to an overnight incubation at 4 °C with a mixture of primary antibodies, specifically anti-β-actin and anti-HO-1, both sourced from Proteintech Group (Wuhan, China). After the overnight incubation, the membranes were thoroughly washed with TBST to remove any unbound antibodies. This was followed by a 1-h incubation at room temperature with secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit HRP), aimed at detecting the primary antibodies. The membranes were finally rewashed with TBST to prepare for the subsequent detection steps. And developed using ECL (Biosharp, Guangzhou, China) in a machine. Gray values were analyzed using ImageJ software.

4.12. Establishment and treatment of periodontitis mouse model

Conducted in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines, the Ethics Review Committee at Shandong University Stomatological Hospital granted formal approval for the experimental procedures, as outlined in protocol No. 20230377. Male C57 mice (6 weeks old, ∼20 g, from Viton Lever Animals, China) were used, with 6 per group, totaling 30. Located at the Animal Center of Shandong University, the mice were maintained under a 12-h dark/light regimen and a temperature range of 20–25 °C, with continuous availability of autoclaved food and water.

The mice were randomly divided into five groups. Apart from the control group, the mice in the other groups underwent silk ligation (5-0) of the maxillary second molar and buccal and palatal injections of LPS (1 μg/μL) for a duration of two weeks. After the modeling period, the respective drug solutions (PBS, CORM-3, MPN, CO@MPN) were administered in a similar manner for an additional two weeks. On the 14th day, the mice were euthanized, and their organs and maxillae were collected for further analysis.

4.13. Micro-CT analysis and H&E staining

Post-sampling, the mouse maxilla was immersed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (Biosharp, Guangzhou, China) for 24 h. Micro-CT scans were acquired with micro-CT (SKYSCAN 1276, BRUKER, Germany), followed by 3D reconstruction via the CTvox and bone density analysis using the CTAn. The samples were then decalcified in 10 % EDTA solution, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm for H&E and immunohistochemical staining. Sections underwent dewaxing in dimethylbenzene (FUYU CHEMICAL, Tian Jin, China) and graded ethanol, staining with a hematoxylin-eosin kit (Solarbio, Bei Jing, China), re-dehydration, and mounting with neutral gum (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Analysis was performed under a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

4.14. Immunohistochemistry staining

The tissue sections were initially dried at 60 °C for 1 h, then underwent dehydration in a sequence of xylene and graded alcohols, followed by antigen retrieval using a 0.1 % Trypsin Digestion solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China). To neutralize endogenous peroxidase, a peroxidase blocker (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) was added dropwise at ambient temperature. After the washing process, the sections were treated with primary antibodies, anti-iNOS (Abcam, Shanghai, China), anti-CD206 (GeneTex, Taiwan, China), and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The subsequent day, a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was applied and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. The sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin and developed using DAB (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) for coloration. Ultimately, the slides were observed under an optical microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

4.15. Statistical analysis

Data are reported as the average accompanied by the standard deviation (SD). When assessing multiple groups (three or more), statistical evaluations were executed via one-way or two-way ANOVA, supplemented by Tukey's HSD post-hoc test, all managed through GraphPad Prism (crafted by MacKiev Software, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Caiye Liu: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yi Chen: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ying Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Danyang Wang: Supervision, Software, Resources. Jinyan Sun: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Jiao Sun: Writing – original draft, Methodology. Lingli Ji: Supervision, Software, Methodology. Kai Li: Resources, Project administration. Wenjun Wang: Methodology, Investigation. Weiwei Zhao: Writing – original draft, Methodology. Hui Song: Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Jianhua Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Ethics statement

The Ethics Committee of the Stomatological Hospital at Shandong University granted approval for the animal studies, with the protocol number 20230377. These studies were conducted in strict accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. Additionally, the housing conditions and experimental procedures were designed to ensure the welfare and ethical treatment of the animals.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470981), Shandong Province Key Research and Development Program (2024CXPT090), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024YQ055). We thank Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for consultation and instrument availability that supported this work.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: Multiscale Composites published in Materials Today Bio.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.102213.

Contributor Information

Hui Song, Email: songhui@sdu.edu.cn.

Jianhua Li, Email: jianhua.li@sdu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Mosaddad S.A., Tahmasebi E., Yazdanian A., et al. Oral microbial biofilms: an update. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;38(11):2005–2019. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapple I.L.C., Matthews J.B. The role of reactive oxygen and antioxidant species in periodontal tissue destruction. Periodontol. 2000. 2007;43(1):160–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng J., Liu X., Li K., et al. Intracellular delivery of piezotronic-dominated nanocatalysis to mimic mitochondrial ROS generation for powering macrophage immunotherapy. Nano Energy. 2024;122 doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2024.109287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mi F., Zhao N., Jin L., et al. Conjugated polymers as photocatalysts for hydrogen therapy. BMEMat. n/a(n/a) e12126. doi: 10.1002/bmm2.12126. [DOI]

- 5.Jiang Q.S., Zhao Y.X., Shui Y.S., et al. Interactions between neutrophils and periodontal pathogens in late-onset periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.627328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L.Q., Chen Y., Liu Y., et al. The role of oxidative stress and natural antioxidants in ovarian aging. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.617843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Li K., Shen L., et al. Metal phenolic nanodressing of porous polymer scaffolds for enhanced bone regeneration via interfacial gating growth factor release and stem cell differentiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;14(1):268–277. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c19633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han Y., Huang Y., Gao P., et al. Leptin aggravates periodontitis by promoting M1 polarization via NLRP3. J. Dent. Res. 2022;101(6):675–685. doi: 10.1177/00220345211059418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu S., Ding L., Liang D., et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis inhibits M2 activation of macrophages by suppressing -ketoglutarate production in mice. Molecular Oral Microbiology. 2018;33(5):388–395. doi: 10.1111/omi.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong B.-C. ATF3 mediates the inhibitory action of TNF-α on osteoblast differentiation through the JNK signaling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;499(3):696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerner U.H. Inflammation-induced bone remodeling in periodontal disease and the influence of post-menopausal osteoporosis. J. Dent. Res. 2006;85(7):596–607. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q., Chen B., Yan F., et al. Interleukin-10 inhibits bone resorption: a potential therapeutic strategy in periodontitis and other bone loss diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/284836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S., Wu W.-Y., Yeo J.C.C., et al. Responsive hydrogel dressings for intelligent wound management. BMEMat. 2023;1(2) doi: 10.1002/bmm2.12021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X., Sun Y., Lyu Y., et al. Hydrogels for ameliorating osteoarthritis: mechanical modulation, anti-inflammation, and regeneration. BMEMat. 2024;2(2) doi: 10.1002/bmm2.12078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryter S.W., Choi A.M.K. Targeting heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide for therapeutic modulation of inflammation. Transl. Res. 2016;167(1):7–34. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRae K.E., Pudwell J., Peterson N., et al. Inhaled carbon monoxide increases vasodilation in the microvascular circulation. Microvasc. Res. 2019;123:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segersvard H., Lakkisto P., Hanninen M., et al. Carbon monoxide releasing molecule improves structural and functional cardiac recovery after myocardial injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018;818:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryter S.W. Therapeutic potential of heme Oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in acute organ injury, critical illness, and inflammatory disorders. Antioxidants. 2020;9(11) doi: 10.3390/antiox9111153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Southam H.M., Smith T.W., Lyon R.L., et al. A thiol-reactive Ru(II) ion, not CO release, underlies the potent antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of CO-releasing molecule-3. Redox Biol. 2018;18:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidge K.S., Motterlini R., Mann B.E., et al. In: Poole R.K., editor. vol. 56. 2009. Carbon monoxide in biology and microbiology: surprising roles for the "Detroit Perfume"; pp. 85–167. (Advances in Microbial Physiology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lv W., Hu S., Yang F., et al. Heme oxygenase-1: potential therapeutic targets for periodontitis. PeerJ. 2024;12 doi: 10.7717/peerj.18237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Chu T., Jin T., et al. Cascade reactions catalyzed by gold hybrid nanoparticles generate CO gas against periodontitis in diabetes. Adv. Sci. 2024;11(24) doi: 10.1002/advs.202308587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J., Song L., Hou M., et al. Carbon monoxide releasing molecule-3 promotes the osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by releasing carbon monoxide. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018;41(4):2297–2305. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lv J., Liu Y., Jia S., et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing Molecule-3 suppresses tumor necrosis Factor-α- and Interleukin-1β-Induced expression of junctional molecules on human gingival fibroblasts via the heme Oxygenase-1 pathway. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6302391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita K., Tanaka Y., Sho T., et al. Intracellular CO release from composite of ferritin and ruthenium carbonyl complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(48):16902–16908. doi: 10.1021/ja508938f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motterlini R., Mann B.E., Johnson T.R., et al. Bioactivity and pharmacological actions of carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003;9(30):2525–2539. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matson J.B., Webber M.J., Tamboli V.K., et al. A peptide-based material for therapeutic carbon monoxide delivery. Soft Matter. 2012;8(25):6689–6692. doi: 10.1039/c2sm25785h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa U., van der Vlies A.J., Simeoni E., et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing micelles for immunotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132(51):18273–18280. doi: 10.1021/ja1075025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Y., Sun Q., Wu F.-G., et al. Polyphenol-containing nanoparticles: synthesis, properties, and therapeutic delivery. Adv. Mater. 2021;33(22) doi: 10.1002/adma.202007356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H., Wang D., Yu J., et al. Applications of metal–phenolic networks in nanomedicine: a review. Biomater. Sci. 2022;10(20):5786–5808. doi: 10.1039/d2bm00969b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarode A., Annapragada A., Guo J., et al. Layered self-assemblies for controlled drug delivery: a translational overview. Biomaterials. 2020;242 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X., Gao P., Tan J., et al. Assembly of metal phenolic/catecholamine networks for synergistically anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticoagulant coatings. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2018;10(47):40844–40853. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b14409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y., Chen Y., Ding T., et al. Janus porous polylactic acid membranes with versatile metal-phenolic interface for biomimetic periodontal bone regeneration. NPJ Regen. Med. 2023;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41536-023-00305-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan G., Cottet J., Rodriguez-Otero M.R., et al. Metal-phenolic networks as versatile coating materials for biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022;5(10):4687–4695. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.2c00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J.Q., Pan S.J., Zhou J.J., et al. Assembly of bioactive nanoparticles via metal-phenolic complexation. Adv. Mater. 2022;34(10) doi: 10.1002/adma.202108624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen D., Boyer C. Macromolecular and inorganic nanomaterials scaffolds for carbon monoxide delivery: recent developments and future trends. Acs Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2015;1(10):895–913. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozawa H., Haga M.A. Soft nano-wrapping on graphene oxide by using metal-organic network films composed of tannic acid and Fe ions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17(14):8609–8613. doi: 10.1039/c5cp00264h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motterlini R., Clark J.E., Foresti R., et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules - characterization of biochemical and vascular activities. Circ. Res. 2002;90(2):E17–E24. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.104530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunz P.C., Meyer H., Barthel J., et al. Metal carbonyls supported on iron oxide nanoparticles to trigger the CO- gasotransmitter release by magnetic heating. Chem. Commun. 2013;49(43):4896–4898. doi: 10.1039/c3cc41411f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren H., Wu Z., Li J., et al. A biomimetic, triggered-release micelle formulation of methotrexate and celastrol controls collagen-induced arthritis in mice. BMEMat. 2024;2(4) doi: 10.1002/bmm2.12104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magar K.T., Boafo G.F., Zoulikha M., et al. Metal phenolic network-stabilized nanocrystals of andrographolide to alleviate macrophage-mediated inflammation in-vitro. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023;34(1) doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao J., Chen Z., Liu S., et al. Nano-bio interactions between 2D nanomaterials and mononuclear phagocyte system cells. BMEMat. 2024;2(2) doi: 10.1002/bmm2.12066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mantovani A., Sica A., Sozzani S., et al. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosser D.M., Edwards J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viniegra A., Goldberg H., Cil C., et al. Resolving macrophages counter osteolysis by anabolic actions on bone cells. J. Dent. Res. 2018;97(10):1160–1169. doi: 10.1177/0022034518777973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin C.-C., Yang C.-C., Hsiao L.-D., et al. Heme Oxygenase-1 induction by carbon monoxide releasing Molecule-3 suppresses Interleukin-1β-Mediated neuroinflammation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang G., Fan M., Zhu J., et al. A multifunctional anti-inflammatory drug that can specifically target activated macrophages, massively deplete intracellular H2O2, and produce large amounts CO for a highly efficient treatment of osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2020;255 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song L., Li J., Yuan X., et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecule suppresses inflammatory and osteoclastogenic cytokines in nicotine-and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human periodontal ligament cells via the heme oxygenase-1 pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017;40(5):1591–1601. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun X., Gao J., Meng X., et al. Polarized macrophages in periodontitis: characteristics, function, and molecular signaling. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.763334. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.