Abstract

Background

Oral cancer is a major health issue in the world because of its high morbidity and mortality rates. Dysregulated apoptosis, is involved in tumor progression and treatment resistance. Friedelin, a natural triterpenoid, has been shown to have potential to modulate apoptosis pathways. This study investigates the therapeutic effects of Friedelin, particularly on its interactions with apoptotic proteins, cytotoxic effects on KB oral cancer cells, and ability to induce apoptosis through intrinsic signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Interaction networks were constructed by taking target genes related to Friedelin and oral cancer identified by CTD and GeneCards, and applying them in the STITCH database for analysis. Apoptotic binding affinity of key proteins, towards Friedelin was determined using molecular docking. The cytotoxic potential of Friedelin was accessed by performing in vitro assays such as MTT, morphology analysis, and Annexin V-FITC flow cytometry. The regulation of Friedelin on apoptosis was validated through gene expression analysis.

Results

Network analysis identified Friedelin's critical interactions with apoptotic regulators. Molecular docking revealed strong binding affinities, particularly with Bax (−8.3 kcal/mol) and Bcl2 (−8.0 kcal/mol). Cytotoxicity assays showed dose- and time-dependent effects. Gene expression analysis confirmed upregulation of Bax, Caspase-3, and TP53, and downregulation of Bcl2, demonstrating activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathways.

Conclusion

Friedelin is an anticancer agent that has great potential for oral cancer treatment by modulating apoptotic signaling pathways and inducing apoptosis. Future studies should be conducted on the in vivo validation and clinical translation of Friedelin as a novel therapeutic candidate.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Oral cancer remains a significant global health challenge due to its aggressive nature and limited treatment options. Despite advancements in medical knowledge and technology, the mortality rate associated with oral cancer underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies to address its complexity. Central to oral cancer pathology is apoptosis, a tightly regulated process essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis. In oral cancer, this balance is disrupted, allowing malignant cells to proliferate unchecked. Dysregulation of apoptosis not only promotes tumor growth but also contributes to resistance against various chemotherapeutic agents.1

Apoptosis involves mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, cytochrome c release, apoptosome formation, and the activation of caspase-9 and downstream caspases, ultimately leading to DNA fragmentation. The extrinsic pathway, initiated by factors such as Fas ligand or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), triggers procaspase activation. Recent study suggest that inducing apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells represents a promising strategy for combating oral cancer, with pharmacological and biological approaches yielding encouraging results.2

Natural compounds have emerged as potential cancer adjuvants due to their diverse pharmacological properties. Among them, friedelin, a pentacyclic triterpenoid abundant in plants such as Aristotelia chilensis, Cannabis roots, and Maytenus ilicifolia, has garnered attention for its biological activities (Fig. 1). Traditionally used to treat pain and inflammation, friedelin exhibits anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic, and cytotoxic effects in a dose-dependent manner, including against human MCF-7 breast cancer cells.3 It also inhibits human liver cytochrome P450 enzymes, displays weak antibacterial effects, and possesses vasodilatory, antioxidant, and gastroprotective properties, as demonstrated in rat models.4

Fig. 1.

Structure of friedelin.

Despite growing evidence of friedelin's anticancer properties, its specific effects on apoptosis in oral cancer remain inadequately explored. Understanding its mechanisms as a chemotherapeutic agent could facilitate targeted approaches to oral cancer treatment. This study employed a combined in vitro and computational approach to investigate friedelin's impact on key apoptotic markers in oral cancer cells. By analyzing molecular pathways, we sought to elucidate friedelin's potential as an adjuvant therapy for oral cancer. Our findings underscore its role in modulating apoptosis, paving the way for further research into its therapeutic applications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. In silico analysis

Computational tools were used to analyze the interaction of friedelin with proteins involved in oral cancer. After following Kuhn et al.,5 protein targets were predicted and analyzed in the STITCH database to create an interaction network visualized with Cytoscape.6 Molecular docking studies were carried out using PyRx (Autodock). Protein structures, such as Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, and p53, were retrieved from RCSB PDB, prepared using BIOVIA Discovery Studio, and converted to compatible formats with Open Babel. BIOVIA was used to visualize the docking output and determine the binding affinity of the interaction mode.

2.2. Chemicals

The study procured commercial Friedelin dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma Chemical Pvt., Ltd. St. Louis, MO., USA); trypsin-EDTA, fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics-antimycotics, Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco US), total RNA Isolation Reagent (TRIR) (Invitrogen in the United States); Go Taq Green master mix (Promega) and the reverse-transcriptase enzyme (New England Biolabs, US); β-actin, Bax, Bcl-2, Casp3, Casp9, p53, and Eurofins Genomics India Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India, provided the primers.

2.3. Maintenance of cell lines

Cell line KB-1, a human epithelial carcinoma cell line originally derived from an oral epidermoid carcinoma were obtained from National Centre for Cell Science (Pune, India) cultured in RPMI media containing 10 % FBS, 1 % amphotericin B, and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated in 37 °C humidified with a 5 % CO 2 atm. When the cell cultures reached confluency, cells were trypsinized and plated for further experiments.

2.4. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using MTT assay. Cells (5 × 104/well) were plated in 96-well plates, treated with friedelin at 100 and 200 μg/mL, and incubated for 24 h. After treatment, 20 μL of MTT reagent was added, and the cells were incubated and then added with DMSO to dissolve formazan crystals. The absorbance was read at 570 nm by an ELISA reader. Cell viability (%) was calculated as [(treated absorbance/control absorbance) × 100].

2.5. Morphological studies

Concentrations of friedelin obtained from the MTT assays were applied to cells (2 × 105/well) grown in 6-well plates for 24 and 48 h. Morphological changes, characterized by the apoptosis, were observed through a phase-contrast microscope.

2.6. Flow cytometry

Apoptosis was estimated through flow cytometry analysis after the cells were incubated with friedelin (1 × 106 cells/well) for 24 and 48 h. Cells were stained, fixed, and analyzed by using the BD FACS instrument, along with Cell Quest Pro V 3.2.1 software.

2.7. mRNA expression analysis

TRIR reagent was used to extract total RNA, which was spectrophotometrically quantified. Reverse transcription kit was used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA). Real-time PCR was used to determine the gene expression of the following: Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, and p53 (Table 1). Amplification and melt curves were plotted, and relative quantification was calculated7, 8.

Table 1.

Primer's detail.

| S.no | Gene name | Primers (5 ′–3 ′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P53 | F- 5′ CCAGCAGCTCCTACACCGGC 3′ | 7 |

| R- 5′ GAAACCGTAGCTGCCCTG 3 | |||

| 2 | Bcl-2 | F- 5′ GGTCGCCAGGACCTCGCCGC 3′ | 7 |

| R- 5′ AGTCGTCGCCGGCCTGGCG 3′ | |||

| 3 | Bax | F- 5′ GAGCTGCAGAGGATGATTGC 3 | 7 |

| R- 5′CCGGGAGCGGCTGTTGGGCT 3′ | |||

| 4 | Casp-3 | F- 5′ GTACAGATGTCGATGCAGC 3′ | 7 |

| R- 5′ CACAATTTCTTCACGTGTA 3′ | |||

| 5 | Casp-9 | F- 5′ CCTGCGGCGGTGCCGGCTGC 3′ | 8 |

| R-5′ GTGTCCTCTAAGCAGGAGAT 3′ | |||

| 6 | β-actin | F- 5′ CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC 3′ | 8 |

2.8. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical differences between groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons post hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Interaction network analysis

Applying CTD and GeneCards, overlapping genes connected with Friedelin and oral cancer were retrieved and analyzed in the STITCH database for significant interactions involving apoptosis regulators like Bcl2, Bax, TP53, Casp3, and Casp9 (Fig. 2). The network brought out that Friedelin had strong binding potential and functional connectivity, hence is highly in the center of regulating apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Interaction network of Friedelin with key apoptotic regulators (BCL2, BAX, TP53, CASP3, CASP9) and signaling pathways (PI3K-AKT, p53) constructed using STITCH, CTD, and GeneCards, showing that TP53 is the central hub in intrinsic pathway activation.

3.2. Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking confirmed the significant binding affinities of Friedelin to the primary apoptotic proteins, Bax (−8.3 kcal/mol), Bcl-2 (−8.0 kcal/mol), and Caspase-9 (−8.1 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3). Major interactions, like hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts, proved the potential of Friedelin for the effective modulation of apoptosis signaling pathways (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Molecular docking interactions of friedelin with apoptosis-related proteins: Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, and p53, respectively. Each panel (A: 2D, B: 3D) shows key binding residues and interaction types, including van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, and π-interactions. Friedelin is shown in grey with red oxygen atoms, docked within the protein's active site. Color-coded surfaces highlight donor (magenta) and acceptor (green) regions. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Molecular docking and interaction of Friedelin to apoptosis-related proteins (Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, Caspase-9, and p53)a.

| Name | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Category (From) | Types (To) | Group (From) | Group (To) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRI-BAX | −8.3 | Hydrogen Bond | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | H-Donor | H-Acceptor |

| FRI-BAX | Hydrophobic | Pi-Sigma | C-H | Pi-Orbitals | |

| FRI-BCL2 | −8.0 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Sigma | C-H | Pi-Orbitals |

| FRI-BCL2 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl | |

| FRI-BCL2 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl | |

| FRI-BCL2 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl | |

| FRI-CAS3 | −7.9 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | H-Donor | H-Acceptor |

| FRI-CAS3 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Conventional Hydrogen Bond | H-Donor | H-Acceptor | |

| FRI-CAS3 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Pi-Sigma | C-H | Pi-Orbitals | |

| FRI-CAS9 | −8.1 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Pi-Sigma | C-H | Pi-Orbitals |

| FRI-p53 | −7.9 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Hydrogen Bond | H-Donor | H-Acceptor |

| FRI-p53 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Hydrophobic | C-H | Pi-Orbitals | |

| FRI-p53 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Hydrophobic | C-H | Pi-Orbitals | |

| FRI-p53 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Hydrophobic | Pi-Orbitals | Alkyl | |

| FRI-p53 | Ligand Non-bond Monitor | Hydrophobic | Pi-Orbitals | Alkyl |

From and to indicating the interaction established from Ligand to Protein.

3.3. Cytotoxicity of friedelin

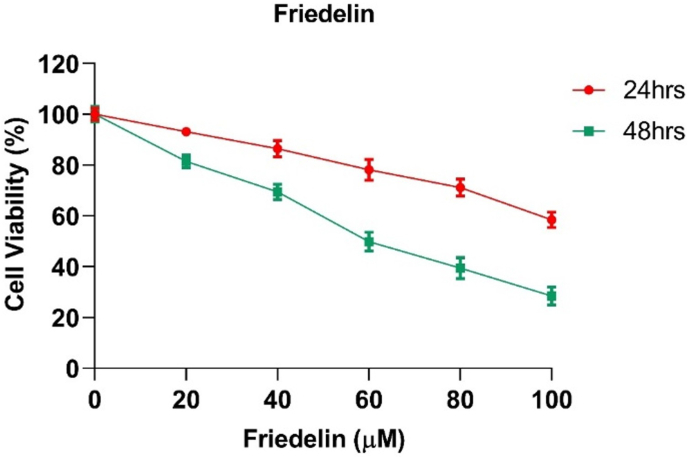

Friedelin exhibited dose-related cytotoxicity against KB cells with IC50 values of 117.25 μM at 24 h and 58.72 μM at 48 h, thus demonstrating its effective anti-proliferative effects (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Friedelin's dose- and time-dependent impact on cell viability. Friedelin treatment at increasing concentrations (0–100 μM) decreased cell viability for both 24 and 48 h, with the effect being most noticeable at 48 h. Mean ± SEM is used to express the data (n = 3).

3.4. Morphological alterations

Friedelin-treated KB cells exhibited significant morphological alterations characteristic of apoptosis, which included loss of adhesion and cell fragmentation (Fig. 5). These were more pronounced at the end of 48 h, which indicates its cytocidal activity.

Fig. 5.

Morphological changes in KB cells treated with Friedelin showing characteristic apoptotic features, including loss of adhesion and cell fragmentation, with the most pronounced effects at 48 h, indicating its cytocidal activity.

3.5. Flow cytometry assay

Flow cytometry results were consistent with a significant increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells. Its value was as high as 22.29 % after 48 h of Friedelin treatment, thus showing the apoptotic potential (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Flow cytometry analysis, showing after 48 h of treatment with Friedelin, there are increases in apoptotic cell percentage, which indicated its potential toward apoptosis.

3.6. Gene expression assay

Friedelin treatment modulated apoptotic gene expression, downregulating anti-apoptotic Bcl2 and upregulating pro-apoptotic Bax, TP53, Caspase-3, and Caspase-9 (Fig. 7). These changes confirm the role of Friedelin in the activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathways and enhancement of p53-mediated signaling, demonstrating its therapeutic potential against oral cancer.

Fig. 7.

Friedelin treatment modulates apoptotic gene expression in KB cells. Fold changes in Bcl2, Bax, p53, Casp3, and Casp9 were normalized to β-actin and presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) indicate suppression of Bcl2 and activation of pro-apoptotic markers Bax, p53, Casp3, and Casp9 mRNA levels, suggesting intrinsic apoptotic pathway activation.

4. Discussion

Oral cancer has significant morbidity and mortality; the challenge is that it requires molecular understanding of the pathways that control cancer progression, resistance to therapy, and targets of novel therapies.9 Disruption of the major tissue homeostasis process apoptosis plays a role in tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Targeting pathways involved in apoptosis is very critical for effective cancer therapy.10 Friedelin, a bioactive natural product, has emerged as a promising therapeutic agent due to its modulation of apoptotic regulators.11,12

Friedelin modulates key apoptotic regulators such as Bcl2, Bax, TP53, Casp3, and Casp9. Network analysis from CTD, GeneCards, and STITCH databases suggests Friedelin interacts with essential apoptotic pathways with TP53 as a central hub. Molecular docking confirmed the dual regulatory functionality of Friedelin with high binding affinities to Bax (−8.3 kcal/mol) and Bcl2 (−8.0 kcal/mol), more potent than standard drugs like Obatoclax.13 Its stability and non-toxicity as an inhibitor of anti-apoptotic proteins support its role in targeting apoptotic pathways. The data indicate that Friedelin can potentially induce a shift from survival signals to pro-apoptotic signaling, which makes it an effective modulator for cancer treatment14, 15.

In vitro studies showed that Friedelin exhibits dose- and time-dependent cytotoxicity in KB cells with IC50 values of 117.25 μM at 24 h and 58.72 μM at 48 h. This is in agreement with previous studies in breast and prostate cancer.3,12 Flow cytometry showed significant induction of apoptosis in KB cells at 22.29 % after 48 h and thus supports the proapoptotic effect of Friedelin, consistent with observed effects on TNF-α, NF-κB, caspase-3, and PARP-1 expression.16,17

Gene expression analysis showed downregulation of Bcl2, upregulation of Bax, and increases in TP53, Casp3, and Casp9. This indicates both mitochondrial and extrinsic pathway modulation by Friedelin. Furthermore, Friedelin modulates ROS, a key controller of apoptosis, that triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and activates the caspase cascade.18, 19, 20 The results indicate that the modulation of oxidative stress by Friedelin can lead to a targeted apoptotic response with minimal off-target damage. Friedelin's interaction with the NF-κB signaling pathway further enhances apoptosis through inhibition of anti-apoptotic proteins.16,21

Friedelin, has shown promising anticancer properties across several cancer types. Studies have reported its ability to induce apoptosis, inhibit cell proliferation, and modulate key signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and NF-κB in cancers including breast,22 colon,23 and prostate carcinoma.24 Its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic effects further support its potential as a natural chemotherapeutic agent. These findings underscore friedelin's broader therapeutic relevance and warrant further exploration in context-specific cancer models.

Friedelin has the ability to cause apoptosis and inhibit cell growth in oral cancer, as evidenced by the reported decrease in Bax and Bcl mRNA expression levels following therapy. Friedelin may reset the balance of the Bcl-2 family proteins in favor of apoptosis, which would result in the death of cancer cells, by reducing Bcl-2 and elevating Bax expression. The results have established, Friedelin as a strong apoptosis inducer that acts on major pathways, particularly through mitochondrial dysfunction and p53-mediated signaling.25 This multi-targeted approach makes Friedelin a promising candidate for cancer therapy, with potential advantages in overcoming resistance to traditional treatment. Future studies should explore in vivo validation, pharmacokinetics, and toxicological properties to optimize its therapeutic potential for oral cancer treatment.

5. Study limitation

This study exclusively examines laboratory experiments and computational models. These methods are beneficial; nevertheless, they fail to illustrate the complexity of living systems or the impact of genetic alterations on protein expression. The data do not validate at the protein level by assessing critical apoptotic markers such as Bax, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3 using Western blotting. Such evidence indicates that the mechanisms are less complex. Furthermore, the use of friedelin's effects in clinical settings is challenging due to the lack of testing in living creatures. Future research must examine protein levels alongside friedelin's efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and potential toxicities in living organisms to address these challenges.

6. Conclusion

Friedelin has a bright future in oral cancer therapy through the induction of apoptosis via ROS modulation and interaction with apoptotic proteins. Further research, including clinical validation and deeper investigation into its pharmacological properties, is required to explore its broader therapeutic applications and confirm its safety and efficacy in cancer treatment.

Patient consent

Since this study did not involve human participants or patient data, obtaining patient consent was not applicable.

Author contributions

PM conceived the project. RS designed the study. PR and AM performed the experiments, analyzed the data and edited the manuscript. PM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RS revised and edited the final draft.

Data availability statement

All materials are available from the corresponding author.

Ethical clearance

This study was conducted using in silico analyses and in vitro experiments, without the involvement of human or animal subjects. Therefore, ethical approval was not applicable.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Nil.

Contributor Information

Ramya Sekar, Email: drramyaopath@gmail.com.

Monisha Prasad, Email: monishaprasad.smc@saveetha.com.

Manikandan Alagumuthu, Email: mailtomicromani@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Dwivedi R., Pandey R., Chandra S., Mehrotra D. Apoptosis and genes involved in oral cancer - a comprehensive review. Oncol Rev. 2020;14(2):472. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2020.472. PMID: 32685111; PMCID: PMC7365992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M.K., Alqhtani N.R., Alnufaiy B., Alqahtani A.S., Elsahn N.A., Russo D., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of resveratrol on oral cancer: potential therapeutic implications. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):412. doi: 10.1186/s12903-024-04045-8. PMID: 38575921; PMCID: PMC10993553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subash-Babu P., Li D.K., Alshatwi A.A. In vitro cytotoxic potential of friedelin in human MCF-7 breast cancer cell: regulate early expression of Cdkn2a and pRb1, neutralize mdm2-p53 amalgamation and functional stabilization of p53. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2017;69(8):630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonisamy P., Duraipandiyan V., Ignacimuthu S. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic effects of friedelin isolated from Azima tetracantha Lam. in mouse and rat models. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;63(8):1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn M., von Mering C., Campillos M., Jensen L.J., Bork P. STITCH: interaction networks of chemicals and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D684–D688. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm795. PMID: 18084021; PMCID: PMC2238848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohl M., Wiese S., Warscheid B. Cytoscape: software for visualization and analysis of biological networks. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;696:291–303. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-987-1_18. PMID: 21063955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Fatlawi A.A., Al-Fatlawi A.A., Zafaryab M., et al. Rhein induced cell death and apoptosis through caspase dependent and associated with modulation of p53, Bcl-2/Bax ratio in human cell lines. Int J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2014;6(2) ISSN-0975-1491. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitupatum T., Aree K., Kittisenachai S., et al. mRNA expression of Bax, Bcl-2, p53, Cathepsin B, Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 in the HepG2 cell line with Hep88 mAb. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2016;17(2):703–712. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.2.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran Q., Maddineni S., Arnaud E.H., et al. Oral cavity cancer in young, non-smoking, and non-drinking patients: a contemporary review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;190 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104112. PMID: 37633348; PMCID: PMC10530437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jan R., Chaudhry G.E. Understanding apoptosis and apoptotic pathways targeted cancer therapeutics. Adv Pharmaceut Bull. 2019;9(2):205–218. doi: 10.15171/apb.2019.024. PMID: 31380246; PMCID: PMC6664112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ram H., Sarkar J., Kumar H., Konwar R., Bhatt M.L., Mohammad S. Oral cancer: risk factors and molecular pathogenesis. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011;10(2):132–137. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0195-z. PMID: 22654364; PMCID: PMC3177522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi B.P., Bhandare V.V., Vankawala M., et al. Friedelin, a novel inhibitor of CYP17A1 in prostate cancer from Cassia tora. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023;41(19):9695–9720. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2145497. PMID: 36373336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowtham H.G., Ahmed F., Anandan S., et al. In silico computational studies of bioactive secondary metabolites from Wedelia trilobata against anti-apoptotic B-Cell Lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) protein associated with cancer cell survival and resistance. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1588. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041588. PMID: 36838574; PMCID: PMC9959492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J., Hu T., Gao L., et al. Friedelane-type triterpene cyclase in celastrol biosynthesis from Tripterygium wilfordii and its application for triterpenes biosynthesis in yeast. New Phytol. 2019;223(2):722–735. doi: 10.1111/nph.15809. PMID: 30895623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emsen B., Engin T., Turkez H. In vitro investigation of the anticancer activity of friedelin in glioblastoma multiforme. Afyon Kocatepe Univ J Sci Eng. 2018;18:763–773. doi: 10.5578/fmbd.67733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandhu M., Irfan H.M., Arshad L., Ullah A., Shah S.A., Ali H. Friedelin and glutinol induce neuroprotection against ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in pup's brain through reduction of TNF-α, NF-κB, caspase-3, and PARP-1. Neurotoxicology. 2023;99:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2023.11.002. PMID: 37939858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy A., Cheriyan B.V., Perumal E., Rengasamy K.R., Anandakumar S. Effect of hinokitiol in ameliorating oral cancer: in vitro and in silico evidences. Odontology. 2024:Nov 14 doi: 10.1007/s10266-024-01020-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39540968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arivalagan N., Ramakrishnan A., Sindya J., Rajanathadurai J., Perumal E. Capsaicin promotes apoptosis and inhibits cell migration via the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) signaling pathway in oral cancer cells. Cureus. 2024;16(9) doi: 10.7759/cureus.69839. PMID: 39435241; PMCID: PMC11492975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J. The cell-cycle arrest and apoptotic functions of p53 in tumor initiation and progression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(3) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026104. PMID: 26931810; PMCID: PMC4772082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIlwain D.R., Berger T., Mak T.W. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2013;5(4) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. Erratum in: Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015 Apr 1;7(4):a026716. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a026716. PMID: 23545416; PMCID: PMC3683896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ditty M.J., Ezhilarasan D. β-sitosterol induces reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2021;11(6):541–550. doi: 10.22038/AJP.2021.17746. PMID: 34804892; PMCID: PMC8588954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subash-Babu P., Li D.K., Alshatwi A.A. In vitro cytotoxic potential of friedelin in human MCF-7 breast cancer cell: regulate early expression of Cdkn2a and pRb1, neutralize mdm2-p53 amalgamation and functional stabilization of p53. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2017 Oct 2;69(8):630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi B., Liu S., Huang A., et al. Revealing the mechanism of friedelin in the treatment of ulcerative colitis based on network pharmacology and experimental verification. Evid base Compl Alternative Med. 2021;2021(1) doi: 10.1155/2021/4451779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi B.P., Bhandare V.V., Vankawala M., et al. Friedelin, a novel inhibitor of CYP17A1 in prostate cancer from Cassia tora. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023 Nov 24;41(19):9695–9720. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2145497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panda S.P., Kesharwani A., Singh M., et al. Limonin (LM) and its derivatives: unveiling the neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory potential of LM and V-A-4 in the management of Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Fitoterapia. 2024;178 doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2024.106173. PMID: 39117089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All materials are available from the corresponding author.