Abstract

A 13-kb DNA fragment containing oriC and the flanking genes thdF, orf900, yidC, rnpA, rpmH, oriC, dnaA, dnaN, recF, and gyrB was cloned from the gram-negative plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris 17. These genes are conserved in order with other eubacterial oriC genes and code for proteins that share high degrees of identity with their homologues, except for orf900, which has a homologue only in Xylella fastidiosa. The dnaA/dnaN intergenic region (273 bp) identified to be the minimal oriC region responsible for autonomous replication has 10 pure AT clusters of four to seven bases and only three consensus DnaA boxes. These findings are in disagreement with the notion that typical oriCs contain four or more DnaA boxes located upstream of the dnaA gene. The X. campestris pv. campestris 17 attB site required for site-specific integration of cloned fragments from filamentous phage φLf replicative form DNA was identified to be a dif site on the basis of similarities in nucleotide sequence and function with the Escherichia coli dif site required for chromosome dimer resolution and whose deletion causes filamentation of the cells. The oriC and dif sites were located at 12:00 and 6:00, respectively, on the circular X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome map, similar to the locations found for E. coli sites. Computer searches revealed the presence of both the dif site and XerC/XerD recombinase homologues in 16 of the 42 fully sequenced eubacterial genomes, but eight of the dif sites are located far away from the 6:00 point instead of being placed opposite the cognate oriC. The differences in the relative position suggest that mechanisms different from that of E. coli may participate in the control of chromosome replication.

The gram-negative plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris is the causal agent of black rot in crucifers, causing tremendous loss in agriculture worldwide (48). This bacterium is also known to produce an exopolysaccharide, xanthan gum, which is important in pathogenicity and has a variety of applications in oil drilling, food, cosmetics, and agriculture (37). We have previously constructed a physical map of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome (4.8 Mb) bearing restriction sites for four rare-cutting enzymes, SwaI (6 sites), PacI (5 sites), I-CeuI (2 sites), and PmeI (2 sites), and determined the chromosomal location for 23 genetic loci, including two rRNA operons and the genes involved in xanthan synthesis and yellow pigmentation (42). However, the map still lacks important landmarks, such as the origin of chromosome replication (oriC) and the sequence equivalent to that of Eschericia coli dif required for resolution of chromosome dimers (2, 5, 10, 20).

Bacterial chromosome replication is initiated at the oriC region where a cluster of four or more DnaA boxes are present for the binding of DnaA, an initiator protein sharing high degrees of sequence similarity to homologues from different bacteria, to cause local unwinding of DNA within oriC (8, 20, 22, 31, 53). The oriC region can be isolated as autonomously replicating DNA fragments, called oriC plasmids (16, 17, 18, 21, 28, 34, 36, 54, 56). Studies of oriC regions from more than 10 species of eubacteria have revealed several important characteristics (Bacillus subtilis, accession number NC_000964; Bacillus halodurans, NC_002570; Buchnera sp. APS, NC_002528; Clostridium acetobutylicum, NC_003030; Pasteurella multocida, NC_002663; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, AE_004091; Pseudomonas putida, X62540; Staphylococcus aureus Mu50, NC_002578; and Xylella fastidiosa, NC_002488). First, genome organization of the oriC region is conserved. In the oriC flanking regions, gidA, thdF, yidC, rnpA, rpmH, dnaA, dnaN, recF, and gyrB have been identified, and clustering of dnaA, dnaN, recF, and gyrB is common. Second, in gram-positive bacteria, DnaA boxes exist in both upstream and downstream noncoding regions flanking dnaA gene and replication initiates within the downstream DnaA box region; in contrast, the DnaA box cluster is only found upstream of the dnaA gene in gram-negative bacteria (22). However, different organizations have also been observed in some other bacteria. The oriC regions of E. coli, Vibrio harveyi, and other enteric bacteria are located between gidA and mioC far upstream from the dnaA gene (56). Caulobacter crescentus oriC is located between hemE and rpsT about 2 kb away from dnaA, which is separated from the dnaN, recF, gyrB cluster by a distance of 150 kb (55). The dnaA gene is not present in the vicinity of the Coxiella burnetii oriC region, which contains only two DnaA boxes (36). In Sinorhizobium meliloti, Synechocystis spp., and Prochloroccus marinus, oriC-like sequences have not been detected in the regions next to that of dnaA (18, 26, 27).

In E. coli, the circular chromosome replicates in a bidirectional manner, and replication forks meet in the terminus region directly opposite oriC (1, 10). Lying in the middle of the terminus region is the dif site required for converting circular chromosome dimers into monomers at the end of a replication cycle (2, 5, 10). Strains deleted for dif are incapable of normal partitioning of the newly replicated chromosomes into daughter cells, resulting in the Dif phenotype, which includes abnormal nucleoid morphology, filamentation in a fraction of the cells, induction of the SOS repair system, and decreased growth rate and plating efficiency compared to those of wild-type cells (10, 23). It is known that RecA function and the RecBCD and RecF pathways contribute to the formation of chromosome dimers. The Dif phenotype is suppressed in a recA mutant, partially suppressed by either of the mutations in recB or recF, and completely suppressed by the double mutations (10, 35).

In X. campestris pv. campestris, a chromosomal attB site has been identified which is required for the site-specific integration of the cloned replicative form (RF) DNA fragment from the filamentous phage φLf (15). In this study, we (i) cloned and sequenced the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region, (ii) showed that the attB site also served as the dif site required for chromosome dimer resolution, and (iii) determined the location of oriC and dif sites on the chromosome map.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and Luria agar were the media for cultivation of E. coli (37°C) and X. campestris (28°C). The antibiotic used was ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml), gentamicin (15 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), or tetracycline (15 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phage used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mk+) supE44 thi-1 recA gyrA relA1 φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| Xanthomonas | ||

| X. campestris pv. campestris 17 | A wild-type strain isolated in Taiwan, Apr | 50 |

| Xc17-ori | X. campestris pv. campestris 17 derivative with SwaI-PacI sites and Kmr gene integrated near oriC, Apr, Kmr | This study |

| Xc17::KFSK | X. campestris pv. campestris 17 derivative with SwaI-PacI sites and Kmr gene integrated at the dif site, Apr, Kmr | This study |

| L1 | X. campestris pv. campestris 17 recA mutant constructed by inserting a Kmr cartridge into the HindIII site of the recA gene, Apr, Kmr | 12 |

| NT3 | X. campestris pv. campestris 17 recA mutant constructed by inserting a Gmr cartridge into the HindIII site of the recA gene, Apr, Gmr | This study |

| NT1(Δ4445) | X. campestris pv. campestris 17 mutant constructed by replacing the 4,445-bp FHR with a Tcr cartridge, Apr, Tcr | 15 |

| NT2(Δ345) | X. campestris pv. campestris 17 mutant constructed by replacing the 345-bp HincII (containing a dif site) fragment within FHR with a Tcr cartridge, Apr, Tcr | 5 |

| NT1R(att51) | Derived from NT1(Δ4445) by reinserting the dif site, carried by a pDIFT insert (a 51-bp HincII-PstI fragment), via homologous recombination at the Tcr gene, Apr, Tcr | 15 |

| NT1recA::Gm | Derived from NT1(Δ4445) by inserting a Gmr cartridge into the recA gene, Apr, Tcr, Gmr | This study |

| Xc17NT1::HIMA | Derived from NT1(Δ4445) by inserting pDIFHIM into the himA gene, Apr, Tcr, Kmr | This study |

| Xc17NT1::XHC | Derived from NT1(Δ4445) by inserting pDIFXHC into the UDP-glucose dehydrogenase gene, Apr, Tcr, Kmr | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pOK12 | E. coli general cloning vector, P15A replicon, lacZα fragment, Kmr | 43 |

| pBluescript+ | E. coli general cloning vector, ColE1 replicon, lacZα fragment, Apr | Stratagene |

| pUC18 | E. coli general cloning vector, ColE1 replicon, lacZα fragment, Apr | 51 |

| pUC19G | Gmr cartridge from pUCGM ligated with the blunt-ended AvaII-SspI large fragment from pUC19 | This study |

| pUC4K | Derivative of pUC18, providing a Kmr cartridge | 39 |

| pUCGM | Derivative of pUC18, providing a Gmr cartridge | 32 |

| pHP45Ω-Tc | Derivative of pBR322, providing a Tcr cartridge | 24 |

| pBA571 | An internal fragment of X. campestris pv. campestris dnaA (571 bp) amplified by PCR and cloned in pOK12 | This study |

| pXK130 | A 13-kb Sau3A1 fragment containing oriC from X. campestris pv. campestris cloned in pOK12 | This study |

| pXK12 | The upstream 9,471-bp KpnI-HindIII fragment from a pXK130 insert cloned in pOK12, autonomous replication in X. campestris pv. campestris | This study |

| pUEK1.3 | The upstream 1,310-bp KpnI-EcoRI fragment from a pXK130 insert cloned in pUC18 | This study |

| pUEK1.3Km | NotI fragment containing SwaI-PacI sites and a Kmr gene from pUT-Tn5(pfm)CmKm cloned into pUEK1.3 | This study |

| pXB7 | The downstream 5,537-bp HindIII-BamHI fragment from a pXK130 insert cloned in pOK12 | This study |

| pUP1 | The PstI fragment from a pXK130 insert (nt 6231-7242) cloned in pUC19G | This study |

| pUP2 | The PstI fragment from a pXK130 insert (nt 4432-6231) cloned in pUC19G | This study |

| pOH1.7 | The HindIII fragment from a pXK130 insert (nt 7706-9450) cloned in pOK12 | This study |

| pGORI2333 | A PCR fragment corresponding to nt 5527-7859 of a pXK130 insert cloned in pUC19G, autonomous replication in X. campestris pv. campestris 17a | This study |

| pGORI1041 | A PCR fragment corresponding to nt 6819-7859 of a pXK130 insert cloned in pUC19G, autonomous replication in X. campestris pv. campestris 17a | This study |

| pGORI547 | A PCR fragment corresponding to nt 7313-7859 of a pXK130 insert cloned in pUC19G, autonomous replication in X. campestris pv. campestris 17a | This study |

| pFSK | pBluescript+ derivative carrying a 792-bp PstI-NotI insert, containing an attP site, from phage φLf that can mediate site-specific integration into the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome | This study |

| pKFSK | pFSK derivative with the NotI fragment containing SwaI-PacI sites and a Kmr gene from pUT-Tn5(pfm)CmKm inserted in the NotI site | This study |

| pDIF | The 51-bp HincII-PstI segment containing the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dif site cloned in pOK12 | This study |

| pDIFT | pDIF derivative with a Tc gene inserted in the HindIII site of the multicloning sites of the vector | This study |

| pBSU327 | A 2.7-kb fragment containing the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 recA gene cloned in pUC18 | 12 |

| pDIFXHC | A 0.6-kb XhoI-HincII fragment containing part of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 UDP-glucose dehydrogenase gene cloned in pDIF | This study |

| pDIFHIM | A 0.4-kb KpnI-BamHI fragment containing the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 himA gene cloned in pDIF | This study |

pGORI2333, pGORI1041, and pGORI547 each carried a PCR fragment amplified by using forward primers corresponding to nt 5527 to 5544, 6819 to 6838, and 7313 to 7331 of the pXK130 insert, respectively, and the same reverse primer with a sequence complementary to nt 7842 to 7859 of the pXK130 insert.

DNA techniques.

Restriction endonucleases and other enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.), Takara (Kyoto, Japan), and Amersham (Uppsala, Sweden) and were used according to the instructions provided by the suppliers. The procedures described by Sambrook et al. (29) were used for preparation of chromosome and plasmid DNA, agarose gel electrophoresis, end labeling of oligonucleotides, preparation of 32P-labeled probes, Southern hybridization, and transformation of E. coli. Nucleotide sequence was determined by the dideoxy chain termination method of Sanger et al. (30). Electroporation was performed to transform X. campestris as previously described (45). A DNA fragment internal to the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dnaA gene was PCR amplified with the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome as the template and with primers UP1 (5′-GAAGAGTTTTTCCACACCTT-3′), corresponding to nucleotides (nt) 1412 to 1429, and DOWN1 (5′-GCACGGTCGTATGGTCGC-3′), complementary to nt 878 to 859 from the start codon of P. putida dnaA, respectively (7). These two regions represent the most conserved regions among the bacterial dnaA genes.

Tagging of oriC and dif sites and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

To localize the oriC region on the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome, the gene tagging method developed previously (42) was employed to insert additional rare-cutting sites, one for SwaI and one for PacI, near the oriC region. The steps included the following: (i) cloning of the 1.3-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment containing the C terminus of thdF gene and the N terminus of orf900, from the leftmost part of the pXK130 insert (Fig. 1A) into pUC18 to generate pUEK1.3; (ii) cloning of the NotI segment containing the rare-cutting sites and the kanamycin resistance gene (Kmr) from pUT-Tn5(pfm)CmKm (49) into the NotI site within the pUEK1.3 insert, resulting in pUEK1.3Km; and (iii) electroporation of pUEK1.3Km into X. campestris pv. campestris 17, allowing for chromosomal integration via the homologous region, the 1.3-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment. The mutant strain obtained was designated Xc17-ori. The same strategy was used to tag the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dif site, except that the NotI segment containing the rare-cutting sites and the Kmr gene from pUT-Tn5(pfm)CmKm was cloned into pFSK to generate pKFSK (Table 1), which was then electroporated into X. campestris pv. campestris 17, allowing for integration into the dif site and generating strain Xc17::KFSK.

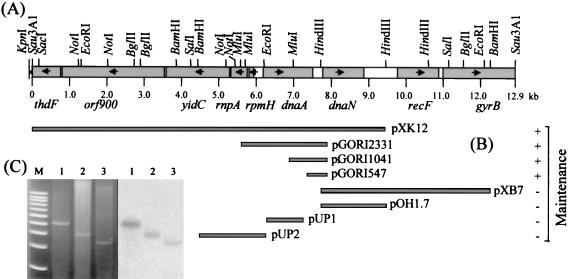

FIG. 1.

(A) Restriction map of the pXK130 insert, a Sau3A1 partial fragment, from X. campestris pv. campestris 17 containing oriC and the flanking genes. The restriction sites were deduced from the nucleotide sequence. The leftmost KpnI site was from the vector. (B) Deletion mapping of the oriC region. The oriC-containing fragments were obtained by either restriction enzyme digestion or PCR amplification and were cloned in the E. coli vector pOK12 (pXK12, pXB7, and pOH1.7) or pUC19G (pUP1, pUP2, pGORI2331, pGORI1041, and pGORI547), as described in Table 1. A plus or minus indicates that the plasmid was capable or incapable of autonomous replication in X. campestris pv. campestris 17, respectively. (C) Detection of minichromosomes in X. campestris pv. campestris 17. Plasmids pGORI2331 (lane 1), pGORI1041 (lane 2), and pGORI547 (lane 3) were extracted from the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 transformants and treated with EcoRI, which cut the vector once. The linearized plasmids were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (left panel) and were transferred by Southern blotting, followed by hybridization with labeled pGORI547 as the probe (right panel).

The procedures described by Tseng et al. (42) were used for the preparation of intact chromosomes, in-gel digestion of the chromosomes with PacI and SwaI, and PFGE in a CHEF-DR III machine from Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.).

Analysis of DNA and protein sequences.

Sequence analysis was performed with the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, Wis.) package. The BLAST algorithms of the National Center for Biotechnology Information were used for sequence searches. The complete genome sequences of eubacteria were from NCBI Microbial Genomes, http//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/entrez/genom-table-cgi.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the oriC-containing region from X. campestris pv. campestris 17 has been registered in GenBank under accession number AY057934.

RESULTS

Cloning of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC-containing fragment.

To clone the oriC-containing fragment from X. campestris pv. campestris 17, an internal fragment of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dnaA gene was synthesized by PCR, cloned, and used as a probe for Southern hybridization to screen for positive clones in an X. campestris pv. campestris 17 genomic library. The primers used for PCR (described in Materials and Methods) represented two of the most conserved regions within the dnaA gene of P. putida that has a genomic G+C content similar to that of the Xanthomonas genomes (63 to 67%) (4). Nucleotide sequence determined for this fragment (571 bp) showed 64% identity to that of the corresponding region of P. putida dnaA (7). This fragment was cloned into pBSK+ to generate plasmid pBA571. Using the labeled 571-bp fragment as the probe for Southern hybridization with the library constructed by cloning the fragments generated by partial digestion with Sau3A1 into pOK12, several clones showing hybridization signals were obtained. One of the clones, designated pXK130 and containing an insert of 13 kb, was capable of replication in X. campestris pv. campestris 17, indicating that the insert contained the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC gene. Figure 1A shows the restriction map of the pXK130 insert.

Sequence of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC-containing fragment.

The 13-kb insert of pXK130 was subcloned into M13mp18 and mp19, and the nucleotide sequences of both strands were determined. Sequence analysis revealed 12,837 bp containing nine open reading frames (ORFs). These ORFs, with the first five running leftward and the last four running rightward, were identified by sequence similarity shared with the amino acids encoded by the genes clustered with oriC in other bacteria (except for orf900). Contiguously, these genes were thdF (nt 729 to 1, incomplete), orf900 (nt 3454 to 752), yidC (nt 5268 to 3547), rnpA (nt 5730 to 5284), rpmH (nt 5909 to 5769), dnaA (nt 6153 to 7481), dnaN (nt 7755 to 8855), recF (nt 9685 to 10860), and gyrB (nt 10974 to 12837, incomplete) (Fig. 1A). Table 2 shows the percent identities of the amino acid sequences shared with those of the homologues from X. fastidiosa, P. putida, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and B. subtilis. Among the homologues, the X. fastidiosa proteins always shared the highest degrees of identity with those of X. campestris pv. campestris 17, ranging from 50 to 93% (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Percent identities of deduced amino acid sequences from the genes around X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC with those of the corresponding gene products from other bacteria

| Bacteriuma | % Identity for protein:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThdFb | ORF900 | YidC | RnpA | RpmH | DnaA | DnaN | RecF | GyrBb | |

| X. fastidiosa (NC_002488) | 71 | 57 | 69 | 50 | 93 | 83 | 77 | 59 | 83 |

| P. putida (X62540) | 58 | —c | 40 | 37 | 75 | 49 | 55 | 33 | 66 |

| P. aeruginosa (NC_002516) | 62 | — | 39 | 35 | 80 | 48 | 55 | 33 | 65 |

| E. coli (L10328) | 56 | — | 36 | 35 | 78 | 54 | 50 | 34 | 67 |

| B. subtilis (NC_000964) | 38 | — | — | 37 | 63 | 38 | 26 | 27 | 53 |

Accession numbers are in parentheses.

Only a partial sequence is available.

—, no homologue present.

There were three large intergenic regions, which were between rpmH and dnaA (243 bp), dnaA and dnaN (273 bp), and dnaN and recF (829 bp).

The X. campestris pv. campestris 17 minichromosome.

To localize the minimal region of X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome required for autonomous replication, subfragments from the pXK130 insert were generated by either restriction cut or PCR amplification. The subfragments were then cloned into pOK12 (Kmr) or pUC19G (Gmr) (Table 1, Fig. 1B). The resultant plasmids were separately electroporated into the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 recA mutants, L1 (for pUC19G derivatives) and NT3 (for pOK12 derivatives), and were selected for kanamycin or gentamicin resistance on LB agar plates. Since the vector could not be maintained, kanamycin or gentamicin resistance suggested that the insert, a minichromosome, contained the oriC which could support autonomous replication. Alkaline lysis was performed to detect the plasmids, and the plasmids extracted were subjected to Southern hybridization. The ability of autonomous maintenance was then further confirmed by transformation of X. campestris pv. campestris 17 cells with the same plasmids. Four of the clones containing overlapping inserts as shown in Fig. 1B, pXK12 (9,471-bp insert), pGORI2333 (2,333-bp insert), pGORI1041 (1,041-bp insert), and pGORI547 (547-bp insert), were found to be maintained autonomously as shown by Southern hybridization with labeled pGORI547 extracted from E. coli DH5α(pGORI547) as the probe (Fig. 1C). Among these oriC-containing plasmids, pGORI547 possessed the smallest insert that included the C-terminal 169 bp of dnaA, the 273-bp dnaA/dnaN intergenic region, and the N-terminal 105 bp of dnaN (Fig. 1B and 2A). We therefore identified the 273-bp dnaA/dnaN intergenic region as the oriC of X. campestris pv. campestris. pGORI2333 containing the complete dnaA gene showed a higher intensity of hybridization signal than the other plasmids with truncated dnaA, indicating that a higher copy number of pGORI2333 was present (Fig. 1C). To test maintenance, L1 cells containing pGORI2333, pGORI1041, or pGORI547 were subcultured five times in overnight cultures with gentamicin, each of which underwent about five doublings, and equal amounts of the cells were subjected to plasmid extraction. Ethidium bromide-stained plasmid DNA bands with intensities comparable to those from the respective plasmids of the original clones were observed (data not shown). These data indicated that these autonomous plasmids could be maintained with the pressure of antibiotics in the recA background.

FIG. 2.

(A) Nucleotide sequence of the 547-bp fragment containing the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region. The base after the dnaA stop codon is counted as nt 1. Shown are the C terminus of dnaA, the 273-bp intergenic region, and the N terminus of dnaN. The three DnaA boxes are boxed, and the AT-rich clusters are shaded and in bold, each with an Arabic numeral to indicate the number of bases. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the three predicted X. campestris pv. campestris 17 DnaA boxes (the first one is the sequence on the complementary strand) and the consensus sequence of the E. coli DnaA box.

DnaA boxes and the pure AT clusters in the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region.

Sequence analysis of the 273-bp X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC revealed some important characteristics. First, it contained 49% A+T, which was much higher than that of the Xanthomonas chromosomes (33 to 36% A+T) (4). However, no AT-rich repeats resembling that in oriC of E. coli and other bacteria were found; instead, 10 pure AT clusters were present: one 7-mer, four 6-mers, one 5-mer, and four 4-mers (Fig. 2A). Second, it contained only three DnaA boxes which had a consensus sequence identical to that of E. coli (Fig. 2A and B) (31). They were situated within the dnaA/dnaN intergenic region, at bp 70 to 78, bp 105 to 113, and bp 237 to 245 downstream of the dnaA termination codon (Fig. 2A). The same relative location was found only in X. fastidiosa oriC (296 bp long; located in the dnaA/dnaN intergenic region), which contains five DnaA boxes and a very high A+T content (72%, including two long strings of AT-rich clusters) compared to that of the whole genome (52.5%) (21). However, no nucleotide sequence identity was shared between these two oriCs.

Chromosomal location of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region.

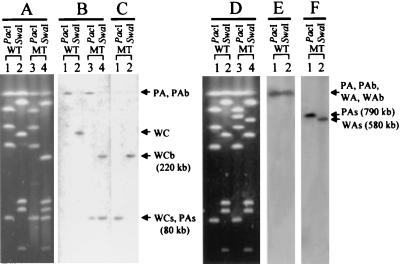

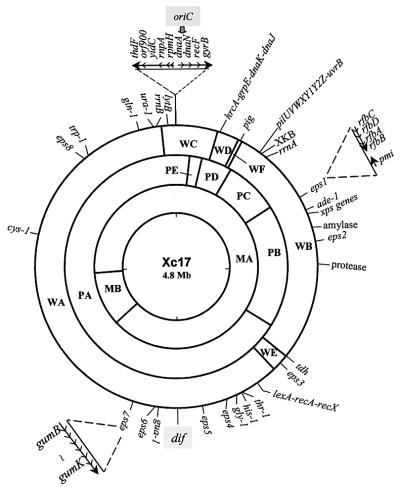

The X. campestris pv. campestris 17 ori gene was localized by the gene tagging strategy described in Materials and Methods, in which one PacI and one SwaI site carried by a suicide plasmid were integrated into the 1.3-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment containing the C terminus of the thdF gene and the N terminus of orf900 (Fig. 1A), resulting in the tagged mutant Xc17-ori. To compare the restriction patterns, chromosomes from X. campestris pv. campestris 17 and Xc17-ori were separately cut with PacI or SwaI. Then the digests were separated by PFGE, which displayed five PacI fragments and six SwaI fragments (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 2) with known sizes (42). Using labeled pUEK1.3, which contains the 1.3-kb KpnI-EcoRI insert, as the probe for Southern hybridization with the digests of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome, the hybridization signal was found to associate with PA (PacI fragment A, 3,270 kb) and WC (SwaI fragment C, 300 kb) (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that oriC was located within the PA/WC overlapping region (Fig. 4). This overlapping region has previously been calculated to be 160 kb (42). The PA fragment from the Xc17-ori chromosome was cut by PacI into subfragments PAb and PAs. Since PAs and PE (PacI fragment E, 80 kb) formed a double band (Fig. 3A, lane 3) as judged by the stronger intensity of PAs than that of PE alone in the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 digest, we estimated the size of PAs to be 80 kb. This result suggested that the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region was located ca. 80 kb from the PA/PE interface (Fig. 4). After SwaI digestion, the WC fragment of the Xc17-ori chromosome was missing and two subfragments, WCb (220 kb) and WCs (80 kb), were generated (Fig. 3A, lane 4). This result suggested that the oriC region was located ca. 80 kb from the WA/WC interface and ca. 220 kb from the WC/WD interface (Fig. 4). Here, the distance from oriC to the WA/WC interface plus that from oriC to the PA/PE interface were equivalent to the length of the PE/WC overlapping region. In other words, the oriC region was located in the middle of the PA/WC overlapping region. Southern hybridization with the labeled plasmid pUEK1.3 as the probe showed signals with PAb, PAs, WCb, and WCs (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4), confirming that X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC was located within the PA/WC overlapping region (Fig. 4). Taking this data together, we set the middle point in the PA/WC overlapping region as 12:00 on the circular X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome map.

FIG. 3.

Southern hybridization of the SwaI and PacI fragments from the X. campestris pv. campestris chromosomes. The chromosomes from X. campestris pv. campestris 17 (wild type [WT] in panels A and D), the oriC-tagged mutant Xc17-ori (MT in panel A), and the dif-tagged mutant Xc17::KFSK (MT in panel D) were digested with SwaI or PacI as indicated above the lanes. The digests were subjected to PFGE (A and D). The DNA fragments were transferred onto nylon membranes and hybridized with the 32P-labeled probes. Both membranes were reused and washed before being probed with another probe. Probes used were pUEK1.3, carrying the 1.3-kb KpnI-EcoRI fragment which contains the C terminus of thdF gene and the N terminus of orf900 (B); pOH1.7, carrying the 1.7-kb HindIII fragment which contains the dnaN gene (C); the 345-bp fragment containing dif (E); and pBSU327, containing the recA gene (F). Designations of the important fragments and the hybridizing signals are indicated at the right-hand side of each set of panels.

FIG. 4.

Improved chromosome map of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris 17. The map originally constructed bore 13 rare-cutting sites (PmeI, 2; PacI, 5; and SwaI, 6) and 23 genetic loci (42). Additional loci determined in this study include, in clockwise order, the oriC region; hrcA, grpE, dnaK, and dnaJ, the stress-responsive genes (47); pilUVWXY1Y2Z and uvrB, the type IV pilus biogenesis genes and DNA repair gene (13); xps gene cluster, the type II protein secretion gene cluster; the amylase gene; the protease gene; the dif site; and the lytB homologue. Arrows outside the circles represent the transcriptional directions. Gene location and transcriptional direction were determined by PFGE separation of the chromosomal digests in conjunction with Southern hybridization as described in this and other studies (13, 42).

To determine the orientation of the genes clustered with X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC, Southern hybridization was performed with the digests from the Xc17-ori chromosome by using the probe prepared from plasmid pOH1.7 that carries the 1.7-kb HindIII fragment containing the dnaN gene (Fig. 1A and B). The hybridization signal was associated with PAs and WCb (Fig. 3C), indicating that the dnaN gene localized to the right of oriC on the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 map (Fig. 4). In other words, the five left-side genes (thdF, orf900, yidC, rnpA, and rpmH) were oriented counterclockwise, and the four right-side genes (dnaA, dnaN, recF, and gyrB) were oriented clockwise (Fig. 4).

Identification of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dif sequence.

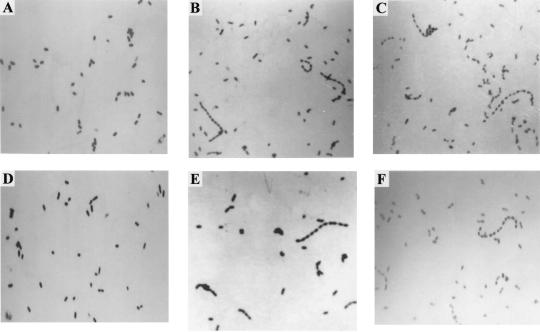

Previously we demonstrated that cloned fragments from the filamentous phage φLf RF DNA can mediate integration, either by homologous recombination at the φLf-homologous region (FHR) in the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome or by site-specific integration at the attB site within the FHR (15). The FHR is 4,445 bp long and is composed of three consecutive HincII fragments of 2,266, 1,834, and 345 bp, with the attB site being contained in the 345-bp fragment. Requirement of the FHR region for integrations was demonstrated by using two deletion mutants, NT1(Δ4445) and NT2(Δ345), in which the FHR and the 345-bp attB-containing HincII fragment, respectively, were replaced with a Tcr cartridge. Both types of integration were abolished in NT1(Δ4445), whereas only the site-specific integration was impaired in NT2(Δ345) (15). It was also demonstrated that the mutant NT1R(att51), in which the 51-bp HincII-PstI segment (within the 345-bp fragment) containing the attB site was reinserted into the Tcr cartridge of NT1(Δ4445), could still accommodate the wild-type levels of site-specific integration (15). With striking similarity to E. coli dif, the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 attB site contained an identical central core, 8 of 11 nucleotides identical left arm and 8 of 11 nucleotides identical right arm (15). Because of the homology and because one of the consequences caused by dif deletion is the appearance of a subpopulation of stringed cells, a deletion-induced filamentation called the Dif phenotype (13), we were interested to know whether deletion of the attB site in X. campestris caused the same consequence. In this study, NT1(Δ4445) and NT2(Δ345) were used to test for the effects. In both mutant strains cultured in LB broth, over 40% of the cells were filamentous as revealed by microscopy (Fig. 5B and C). In contrast, microscopic examination of NT1R(att51) showed that the wild-type morphology was restored (Fig. 5A and D). Based on these results, we proposed that the attB site for φLf integration possessed the function required for the resolution of the chromosome dimer. It was therefore called dif for X. campestris, following the designation for E. coli.

FIG. 5.

Effects of deletion and reinsertion of the dif site on the cell morphology of X. campestris pv. campestris. (A) Wild-type X. campestris pv. campestris 17; (B) NT1(Δ4445), deleted for the 4,445-bp FHR; (C) NT2(Δ345), deleted for the 345-bp HincII fragment within FHR; (D) NT1R(att51), the dif site reinserted near the original site; (E) Xc17NT1::HIMA, the dif site inserted in the himA gene; (F) Xc17NT1::XHC, the dif site inserted in the UDP-glucose dehydrogenase gene. Cells were observed under a light microscope.

In E. coli, RecA function is involved in the formation of chromosomal dimers and mutation of recA suppresses the Dif phenotype (10, 35). In this study, the recA gene of NT1(Δ4445) was knocked out by gene replacement with the Gmr cartridge, and the resultant double mutant was designated NT1recA::Gm. The Dif phenotype of this strain was found to be suppressed (data not shown).

Chromosomal location of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dif sequence.

To localize the dif site on the circular X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome map, we used the same tagging strategy as that for localizing oriC, except that the fragment used to mediate integration was the 792-bp PstI-NotI fragment carrying the attp site from φLf RF DNA. The resultant tagged strain was called Xc17::KFSK. In Southern hybridization with the digests of X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome using the labeled 345-bp fragment as the probe, the hybridization signal was associated with fragments PA (PacI fragment A, 3,270 kb) and WA (SwaI fragment A, 2,880 kb), indicating that the dif-like sequence resided within the overlapping region of fragments WA and PA (Fig. 3E). In the digests of the Xc17::KFSK chromosome, fragments WA and PA were cut by SwaI and PacI into WAb plus WAs (580 kb) and PAb plus PAs (790 kb), respectively. With labeled pBSU327 carrying an insert containing the recA gene (Fig. 4) (12) as the probe for Southern hybridization, the signal was associated with PAs and WAs (Fig. 3F), indicating that the dif sequence was located 790 kb from the PA/PB interface and 580 kb from the WA/WE interface (Fig. 4). On the basis of the data obtained from determination of the chromosomal locations, the distance between oriC and dif could therefore be calculated by summing up the sizes of WAs, WCb (220 kb), and the remaining SwaI fragments (whose sizes had been known previously): WD (125 kb), WF (17 kb), WB (1,369 kb), and WE (98 kb) (Fig. 4) (42). The sum was 2,409 kb, approximately half the size of the 4.8-Mb X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome (42). In other words, the chromosomal locations of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 dif site and oriC were on opposite sides (Fig. 4), like those of E. coli (20).

In E. coli, the location of the dif site is important; the Dif phenotype can be reverted by reinsertion of the dif sequence at a region near the original site, around 30 kb (14, 23, 40). In this study the effects of the location of the dif sequence on the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 chromosome were evaluated in mutants NT1::XHC and NT1::HIMA. NT1::XHC and NT1::HIMA were constructed by inserting plasmid pDIF, which carries the 51-bp HincII-PstI fragment containing the dif site, into eps3, carrying the UDP-glucose dehydrogenase gene (near 4:30, ca. 640 kb from the original dif site) and the himA gene (near 7:00, immediately upstream of eps7, which contains the gum gene cluster ca. 415 kb from the original dif sequence), respectively (Fig. 4). Microscopic examination showed that the Dif phenotype was not reverted by either of the insertions (Fig. 5E and F).

Distribution of dif-like sequences in bacteria.

To detect the distribution of dif-like sequences in Xanthomonas, the chromosomal DNA from X. campestris pathovars citri, manihotis, phaseoli, and vesicatoria and X. oryzae pv. oryzae were digested with EcoRI, separated in agarose gel, and subjected to Southern hybridization with the probe prepared from pDIF that carries the 51-bp HincII-PstI fragment containing the dif site. A single hybridization band was observed in each of the digests, indicating the presence of a dif sequence in all the Xanthomonas strains tested (data not shown).

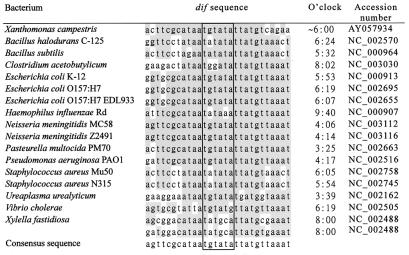

The occurrence of dif-like sequences and XerC/XerD recombinase homologues, the so-called Xer site-specific recombination system (XRS), has been described for several bacteria. In addition, 42 eubacterial genomic sequences have been published (as of 16 October 2001). In this study we searched the databases containing these genomes for nucleotide sequences similar to that of the E. coli dif site (the 28-bp region) and XerC/XerD homologues (3) by using E values of 10 and −30, respectively, as the cut points. Only 16 of these genomes, representing those from 13 species, were found to have both dif sequence and XerC/XerD homologues (Fig. 6). When the chromosomal location of the dif sequence relative to that of cognate oriC (setting the region containing DnaA boxes as 12:00) was compared, it was found that only eight of them, B. halodurans C-125, B. subtilis, E. coli K-12, E. coli O157:H7, E. coli O157:H7 EDL933, S. aureus Mu50, S. aureus N315, and Vibrio cholerae had a location close to 6:00, between 5:32 and 6:24 (Fig. 6). Five others were near either 4:00 (N. meningitidis MC58, N. meningitidis Z2491, and P. aeruginosa) or 8:00 (C. acetobutylicum and X. fastidiosa) (Fig. 6). The remaining three bacteria, Haemophilus influenzae Rd, Pasteurella multocida, and Ureaplasma urealyticum had dif sequences located at 9:40, 3:25, and 3:39, respectively (Fig. 6). In the latter eight cases, the dif sequences were located far away from the 6:00 point, with distances ranging from 147 kb (in U. urealyticum) to 689 kb (in P. aeruginosa). Finally, we also noted that (i) X. fastidiosa contained two dif-like sequences, which were about 10 kb apart (Fig. 6) (33), and (ii) V. cholerae had two chromosomes, but only the larger one possessed a dif sequence (9).

FIG. 6.

The dif sequences of the 17 eubacteria with known genome sequences (except for X. campestris pv. campestris 17) and their positions relative to the DnaA boxes of the cognate oriC at 12:00. The 6-nt central cores are boxed, and the conserved bases are shaded. Shown at the bottom is the consensus sequence derived from the alignments.

DISCUSSION

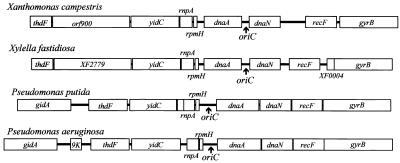

In this study we have characterized the oriC and dif sites of X. campestris pv. campestris 17. Identification of oriC was based on the observations that (i) the cloned fragments containing the dnaA/dnaN intergenic region (273 bp) were capable of autonomous replication, (ii) three DnaA boxes and several AT-rich clusters are contained within the 273-bp region, and (iii) the gene order around this region is conserved with those in other bacteria (Fig. 7). The attB site previously shown to be the region for site-specific integration of the cloned fragments from φLf RF DNA (15) was identified as the dif site based on the observations that (i) deletion of this region caused filamentation of the cells, (ii) reinsertion of a 51-bp segment containing attB near the original site resulted in a restoration of the wild-type phenotype, and (iii) the Dif phenotype was suppressed by a secondary mutation in the recA gene (Fig. 5).

FIG. 7.

Conservation of the local gene order around the oriC region of X. campestris pv. campestris 17, X. fastidiosa (GenBank accession number NC_002488), P. putida (X62540), and P. aeruginosa (NC_002516).

Two distinct characteristics of the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 DnaA boxes are worth noting. First, the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region contains only three DnaA boxes, which disagrees with the notion that a cluster of four or more DnaA boxes is an indication of a functional chromosome origin (22). Second, the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 DnaA boxes are located downstream of dnaA within the dnaA/dnaN intergenic region, a location different from that found for other gram-negative bacteria which are usually situated upstream of the dnaA, dnaN, recF, gyrB cluster or detached from dnaA (22). The same location relative to dnaA has been found only for oriC of X. fastidiosa (21, 33), a plant pathogenic bacterium shown to be closely related to Xanthomonas on the basis of 16S rRNA sequence comparison (46) and on the high degrees of identity shared between the protein homologues of the two bacteria (6). However, no similarity is shared between the nucleotide sequences of the two oriC regions.

The presence of orf900 is special, because only a homologue of unknown function is found in the corresponding region of X. fastidiosa (XF2779) but not in any other bacterial oriC regions sequenced to date. The protein product deduced from orf900 possesses interesting structural features. Amino acid positions 257 to 441 share 30% identity (46% similarity) with plasmid-encoded NodB from Sinorhizobium meliloti, a protein of 217 amino acids possessing chito-oligosaccharide deacetylase activity, required for nodulation (41). The same region also shares 36% identity (52% similarity) with the pgdA gene encoding a 463-amino-acid peptidoglycan, N-acetylglucoseamine deacetylase, between amino acids 286 and 441 in Streptococcus pneumoniae, proposed to contribute to virulence (44). In addition, amino acid positions 786 to 819, 820 to 853, and 854 to 887 of the orf900 product are three tandem motifs called the tetratricopeptide repeat, which is a degenerate 34-amino-acid repeated motif found in organisms as diverse as bacteria and humans, where the tetratricopeptide repeat proteins are involved in processes such as cell cycle control, transcription repression, stress response, protein kinase inhibition, mitochondrial and peroxisomal protein transport, and neurogenesis (11). We have knocked out orf900 by insertional mutation with a gentamicin resistance gene cartridge into the BglII site within its coding region and have tested for properties including colony morphology, phage sensitivity, and pathogenicity. The preliminary data indicated that no changes had been caused by the mutation (data not shown).

The organization of the genes around the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC region is largely the same as that for X. fastidiosa, except that there is an ORF (XF0004) located between X. fastidiosa recF and gyrB. The organization is also highly similar to that of the P. putida and P. aeruginosa oriC regions, except that orf900 is absent from the later regions and that a small gene (9K) is inserted between yidC and rnpA in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 7). Similar genome organization is also found in the fully sequenced genomes of B. subtilis (accession number NC_000964), B. halodurans (NC_002570), Buchnera sp. APS (NC_002528), C. acetobutylicum (NC_003030), P. multocida (NC_002663), and S. aureus Mu50 (NC_002578).

For several bacteria (excluding E. coli), incompatibility has been observed between the plasmid oriC and chromosomal oriC due to titration of the endogenous DnaA protein by the plasmid oriC (22). Therefore, the copy number of oriC plasmids is usually low (25, 52, 54). In this study, the low copy number of the oriC plasmids with truncated dnaA indicates that the titration effect may also occur in X. campestris pv. campestris 17, and the higher copy number of pGORI2333 suggests that additional DnaA might have been produced from the plasmid-borne dnaA gene, making the total DnaA sufficient for the use of both oriC genes. In some bacteria, the oriC-containing plasmids cannot be maintained stably and tend to integrate into the chromosome (19, 21, 34, 38). The integration, mostly at or near their respective oriC regions, occurs even when a recA strain is used. In contrast, the X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC-containing plasmids studied here can be maintained autonomously in the recA strain under the selective pressure of an antibiotic.

By using a gene-tagging strategy we have localized X. campestris pv. campestris 17 oriC in the middle of the PA/WC overlapping region, which was therefore set as 12:00 on the circular chromosome map (Fig. 4). By using the same strategy the dif site was localized opposite oriC, near 6:00. Thus, the relative positions of oriC and dif are similar to those for E. coli, suggesting that a similar mechanism is employed to control chromosome replication in the two organisms.

Computer searches for the dif sequences and the XerC/XerD homologues and comparison of the relative positions between oriC and the cognate dif sequence have revealed several interesting points. First, of the 42 fully sequenced eubacterial genomes, only 16 possess the XRS, indicating that a system other than XRS is required for the resolution of chromosome dimers in the other bacteria that lack an XRS. Second, of the 17 bacteria (including X. campestris pv. campestris 17) that contain an XRS, only 9 (representing 7 species) locate their dif sequence near the 6:00 point. In the other eight genomes the distances between the dif site and the 6:00 point range from 147 kb (in U. urealyticum) to 689 kb (in P. aeruginosa). They are much longer than the distances that allow the dif site to retain the normal function in E. coli (around 30 kb), as demonstrated by the dif deletion and reinsertion experiments (14, 23, 40). These findings suggest either that the dif sites in these eight bacteria are not contained in the terminus region opposite oriC and thus their XRS can use a remote dif as the substrate or that their terminus regions containing the dif site are actually located at regions distant from the 6:00 point. If the latter proposal is true, then the two replication forks must proceed at unequal speeds during bidirectional replication so that they will meet in the terminus region which is far from the 6:00 point. Finally, in V. cholerae the dif site is only present in the larger chromosome, indicating that another mechanism(s) is available for the smaller chromosome to resolve the dimeric molecules.

Genome sequencing of X. campestris pv. campestris 17, the strain used in this study, is underway by collaborative efforts of several research groups, including our laboratory in Taiwan. The chromosome map of X. campestris pv. campestris 17 constructed previously has been improved in this study, and thus the utility of the map has increased. This will greatly benefit our genome sequencing project.

Acknowledgments

M.-R. Yen and N.-T. Lin contributed equally to this work.

This research was partly supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC), Republic of China: NSC 85-2311-B-005-028 to Y.-H. Tseng and NSC 90-2311-B-320-001 to N.-T. Lin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann, B. J. 1990. Linkage map of Escherichia coli K-12, edition 8. Microbiol. Rev. 54:130-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakely, G., S. Colloms, G. May, M. Burke, and D. Sherratt. 1991. Escherichia coli XerC recombinase is required for chromosomal segregation at cell division. New Biol. 3:789-798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakely, G., G. May, R. McCulloch, L. K. Arciszewska, M. Burke, S. T. Lovett, and D. J. Sherratt. 1993. Two related recombinases are required for site-specific recombination at dif and cer in E. coli K12. Cell 75:351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradbury, J. F. 1984. Genus II. Xanthomonas Dowson 1939:187.AL, p. 199. In N. R. Krieg and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 5.Clerget, M. 1991. Site-specific recombination promoted by a short DNA segment of plasmid R1 and by a homologous segment in the terminus region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. New Biol. 3:780-788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dow, J. M., and M. J. Daniels. 2000. Xylella genomics and bacterial pathogenicity to plants. Yeast 17:263-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujita, M. Q., H. Yoshikawa, and N. Ogasawara. 1989. Structure of the dnaA region of Pseudomonas putida: conservation among three bacteria. Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli and P. putida. Mol. Gen. Genet. 215:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller, R. S., B. E. Funnell, and A. Kornberg. 1984. The dnaA protein complex with the E. coli chromosomal replication origin (oriC) and other DNA sites. Cell 38:889-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuempel, P. L., J. M. Henson, L. Dircks, M. Tecklenburg, and D. F. Lim. 1991. dif, a recA-independent recombination site in the terminus region of the chromosome of Escherichia coli. New Biol. 3:799-811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb, J. R., S. Tugendreich, and P. Hieter. 1995. Tetratrico peptide repeat interactions: to TPR or not to TPR? Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:257-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, T. C., N. T. Lin, and Y. H. Tseng. 1996. Isolation and characterization of the recA gene of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 221:459-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, T. C., M. C. Lee, C. H. Hung, S. F. Weng, and Y. H. Tseng. 2001. Sequence, transcriptional analysis and chromosomal location of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris uvrB gene. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:519-528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leslie, N. R., and D. J. Sherratt. 1995. Site-specific recombination in the replication terminus region of Escherichia coli: functional replacement of dif. EMBO J. 14:1561-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, N. T., R. Y. Chang, S. J. Lee, and Y. H. Tseng. 2001. Plasmids carrying cloned fragments of RF DNA from the filamentous phage φLf can be integrated into the host chromosome via site-specific integration and homologous recombination. Mol. Gen. Genet. 266:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madiraju, M. V., M. H. Qin, K. Yamamoto, M. A. Atkinson, and M. Rajagopalan. 1999. The dnaA gene region of Mycobacterium avium and the autonomous replication activities of its 5′ and 3′ flanking regions. Microbiology 145:2913-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marczynski, G. T., and L. Shapiro. 1992. Cell-cycle control of a cloned chromosomal origin of replication from Caulobacter crescentus. J. Mol. Biol. 226:959-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolin, W., D. Bramhill, and S. R. Long. 1995. The dnaA gene of Rhizobium meliloti lies within an unusual gene arrangement. J. Bacteriol. 177:2892-2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masters, M., V. Andresdottir, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1979. Plasmids carrying oriC can integrate at or near the chromosome origin of Escherichia coli in the absence of a functional recA product. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 43:1069-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messer, W., and C. Weigel. 1996. Initiation of chromosome replication, p. 1579-1601. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 21.Monteiro, P. B., D. C. Teixeira, R. R. Palma, M. Garnier, J. M. Bove, and J. Renaudin. 2001. Stable transformation of the Xylella fastidiosa citrus variegated chlorosis strain with oriC plasmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2263-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriya, S., Y. Imai, A. K. Hassan, and N. Ogasawara. 1999. Regulation of initiation of Bacillus subtilis chromosome replication. Plasmid 41:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perals, K., F. Cornet, Y. Merlet, I. Delon, and J. M. Louarn. 2000. Functional polarization of the Escherichia coli chromosome terminus: the dif site acts in chromosome dimer resolution only when located between long stretches of opposite polarity. Mol. Microbiol. 36:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prentki, P., and H. M. Krisch. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin, M. H., M. V. Madiraju, S. Zachariah, and M. Rajagopalan. 1997. Characterization of the oriC region of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 179:6311-6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter, S., and W. Messer. 1995. Genetic structure of the dnaA region of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. J. Bacteriol. 177:4245-4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richter, S., W. R. Hess, M. Krause, and W. Messer. 1998. Unique organization of the dnaA region from Prochlorococcus marinus CCMP1375, a marine cyanobacterium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:534-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salazar, L., H. Fsihi, E. de Rossi, G. Riccardi, C. Rios, S. T. Cole, and H. E. Takiff. 1996. Organization of the origins of replication of the chromosomes of Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis and isolation of a functional origin from M. smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 20:283-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaper, S., and W. Messer. 1995. Interaction of the initiator protein DnaA of Escherichia coli with its DNA target. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17622-17626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweizer, H. P. 1993. Small board-host-range gentamicin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. Bio/Technology 15:831-832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpson, A. J., F. C. Reinach, P. Arruda, et al. 2000. The genome sequence of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Nature 406:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh, R. A., N. R. Choudhury, and H. K. Das. 2000. The replication origin of Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:1070-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steiner, W. W., and P. L. Kuempel. 1998. Cell division is required for resolution of dimer chromosomes at the dif locus of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 27:257-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suhan, M., S. Y. Chen, H. A. Thompson, T. A. Hoover, A. Hill, and J. C. Williams. 1994. Cloning and characterization of an autonomous replication sequence from Coxiella burnetii. J. Bacteriol. 176:5233-5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutherland, I. W., and D. C. Ellwood. 1979. Microbial exopolysaccharide-industrial polymers of current and future potential, p. 107-150. In A. T. Bull, D. C. Ellwood, and C. Ratledge (ed.), Microbial technology. Society for General Microbiology, London, United Kingdom.

- 38.Suvorov, A. N., and J. J. Ferretti. 2000. Replication origin of Streptococcus pyogenes, organization and cloning in heterologous systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189:293-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor, L. A., and R. E. Rose. 1988. A correction in the nucleotide sequence of the Tn903 kanamycin resistance determinant in pUC4K. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tecklenburg, M., A. Naumer, O. Nagappan, and P. Kuempel. 1995. The dif resolvase locus of the Escherichia coli chromosome can be replaced by a 33-bp sequence, but function depends on location. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1352-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torok, I., E. Kondorosi, T. Stepkowski, J. Posfai, and A. Kondorosi. 1984. Nucleotide sequence of Rhizobium meliloti nodulation genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:9509-9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tseng, Y. H., K. T. Choy, C. H. Hung, N. T. Lin, J. Y. Liu, C. H. Lou, B. Y. Yang, F. S. Wen, S. F. Weng, and J. R. Wu. 1999. Chromosome map of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris 17 with locations of genes involved in xanthan gum synthesis and yellow pigmentation. J. Bacteriol. 181:117-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1991. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene 100:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vollmer, W., and A. Tomasz. 2000. The pgdA gene encodes for a peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20496-20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, T. W., and Y. H. Tseng. 1992. Electrotransformation of Xanthomonas campestris by RF DNA of filamentous phage φLf. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 14:65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells, J. M., B. C. Raju, H.-Y. Hung, W. G. Weisburg, L. Mandelco-Paul, and D. J. Brenner. 1987. Xylella fastidiosa gen. nov., sp. nov.: gram-negative, xylem-limited, fastidious plant bacteria related to Xanthomonas spp. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37:136-143. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weng, S. F., P. M. Tai, C. H. Yang, C. D. Wu, W. J. Tsai, J. W. Lin, and Y. H. Tseng. 2001. Characterization of stress-responsive genes, hrcA-grpE-dnaK-dnaJ, from phytopathogenic Xanthomonas campestris. Arch. Microbiol. 176:121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams, P. H. 1980. Black rot: a continuing threat to world crucifers. Plant Dis. 64:736-742. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong, K. K., and M. McClelland. 1992. Dissection of the Salmonella typhimurium genome by use of a Tn5 derivative carrying rare restriction sites. J. Bacteriol. 174:3807-3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang, B. Y., and Y. H. Tseng. 1988. Production of exopolysaccharide and levels of protease and pectinase activity in pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 29:93-99. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yee, T. W., and D. W. Smith. 1990. Pseudomonas chromosomal replication origins: a bacterial class distinct from Escherichia coli-type origins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:1278-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshikawa, H., and R. G. Wake. 1993. Initiation and termination of chromosome replication, p. 507-528. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 54.Zakrzewska-Czerwinska, J., J. Majka, and H. Schrempf. 1995. Minimal requirements of the Streptomyces lividans 66 oriC region and its transcriptional and translational activities. J. Bacteriol. 177:4765-4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zweiger, G., and L. Shapiro. 1994. Expression of Caulobacter dnaA as a function of the cell cycle. J. Bacteriol. 176:401-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zyskind, J. W., J. M. Cleary, W. S. Brusilow, N. E. Harding, and D. W. Smith. 1983. Chromosomal replication origin from the marine bacterium Vibrio harveyi functions in Escherichia coli: oriC consensus sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:1164-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]