Abstract

This study examined the differential sensitivity of intramedullary spinal cord tumors (IMSCTs) and healthy tissue to focused ultrasound (FUS) and microbubbles in a rat model of IMSCT. F98 glioma cells were injected into spinal cords of F344 rats. FUS (580 kHz, 10 ms bursts, 1 Hz pulse repetition frequency, 40 s) was delivered to tumor and adjacent healthy tissue at varying pressures (0–1.2 MPa) following intravenous injection of microbubbles (1.00 ± 0.85 µm; 2.4 × 107 microbubbles/100 g). Tissues were collected 24 h post-treatment for histological analysis. Healthy tissue exhibited pressure-dependent damage, including significant differences in red blood cell (RBC) extravasation between 0 and 1.2 MPa conditions (0 ± 0 vs 1.73 × 105 ± 2.15 × 105, p = 0.015), hemorrhagic pools, and tissue disintegration. Conversely, the presence of histopathological features in tumors, regardless of pressure, and no significant differences in RBC extravasation areas between exposure conditions suggests no treatment-induced damage at the tested exposures. These findings indicate F98 gliomas are less sensitive to FUS and microbubbles than healthy spinal cord, likely due to reduced vascularity (p < 0.00001 compared to grey matter, p < 0.05 compared to white matter). This finding indicates alternative strategies (e.g. nanodroplets or molecularly-targeted bubbles) must be explored for effectively treating CNS tumors with low vascularity.

Keywords: Focused ultrasound, Microbubble, Anti-vascular therapy, Spinal cord tumor, Glioma, Tumor vasculature

Subject terms: Biophysics, CNS cancer, Acoustics

Introduction

Although the use of ultrasound and microbubbles has long been established in diagnostic applications, in the last two decades, the therapeutic potential of focused ultrasound (FUS) and microbubble technologies has gained significant attention1. At low acoustic pressures (mechanical index, MI—defined as the peak negative pressure divided by the square root of the frequency—< 0.72) this approach leverages microbubbles’ stable, non-inertial oscillations to transiently enhance the permeability of nearby barriers3, such as cell membranes and vessel walls, thereby facilitating more effective drug delivery to targeted tissues4. In neurology, this technique can be employed to enhance drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) by modulating the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and blood–spinal cord barrier (BSCB)5,6. These two semi-permeable barriers protect the CNS from pathogens and toxic substances while maintaining the regulated chemical balance necessary for optimal neural function7,8. However, they also filter out systemically administered therapeutic agents, making them the primary impediment to effective drug delivery to the CNS9. Therefore, modulating the BBB or BSCB through non-invasive mechanical means—specifically by applying focused ultrasound in combination with circulating microbubbles, which oscillate in response to the acoustic field and exert mechanical stresses on the vascular endothelium—can improve drug delivery through both enhanced transcellular and paracellular drug delivery, and potentially improve neuro-oncological conditions10. Currently, feasibility and safety of BBB modulation is being clinically tested in several indications including primary11–13 and metastatic14 brain tumors and neurodegenerative diseases15–17, while BSCB modulation is undergoing preclinical evaluation18–21, highlighting the potential of these approaches for advancing drug delivery strategies to CNS tumors.

At higher acoustic pressures, with corresponding MI values exceeding ~ 0.7 for short pulses or lower for longer pules, however, microbubbles exhibit more violent behavior including larger radial excursions and bubble collapse (inertial cavitation), which can lead to more severe and potentially irreversible bioeffects, primarily manifesting as damage to the vasculature (anti-vascular effects)22,23. Anti-vascular effects induced by ultrasound and microbubbles offer promising applications, particularly in tumor growth suppression24,25, radiosensitivity enhancement26,27, tumor immune microenvironment modulation28, and mechanical lesion formation29, all of which are currently being actively investigated10.

US-induced anti-vascular therapy has shown promising results in inhibiting or delaying tumor growth30. This effect is largely attributed to the vascular damage caused by inertial cavitation forces through over-stretch injury, vessel wall invagination, and micro-jetting25,30. Vascular damage can give rise to either a rapid, permanent blood flow shutdown or a temporary reduction in blood flow, which often results in widespread apoptosis and necrosis, particularly in the tumor’s central regions, tumor size reduction, and enhanced survival rates10.

The mainstay of this intervention is that in most organs, especially those with low vascularization, the angiogenic, fragile tumor vasculature is preferentially more sensitive to ultrasound-induced anti-vascular therapy than the healthy tissue23. Wang et al. reported that while immature vessels—characterized by increased permeability, compromised basement membrane, and limited pericyte coverage—were significantly diminished after the treatment, the mature vessels remained largely unaffected31. Additionally, in a murine melanoma model, Wood et al. observed that the pre-existing arterioles and venules encapsulated within the tumor were not impacted by low-intensity ultrasound and microbubble treatment. In contrast, the newly formed angiogenic vessels were disrupted by the therapy24,32. Liu et al. also demonstrated during anti-vascular treatment of subcutaneous tumors from the Walker 250 cell line at different ultrasound pressures that large vessels in proximity always stayed perfused33. This highlights the importance of vessel immaturity in these treatments.

An additional benefit of ultrasound-induced vascular damage in tumors is its potential to augment other anti-cancer therapies10. When combined with chemotherapy, the anti-vascular effects are amplified, synergistically boosting tumor growth inhibition34. The two treatments effectively complement each other’s limitations by targeting different tumor region23,35,36, and by promoting drug uptake23.

US-induced anti-vascular effects can also enhance the tumor response to radiation therapy10. This synergistic effect stems from the cavitation-mediated activation of the ASMase-ceramide pathway which promotes endothelial cell death37,38.

Additionally, FUS-induced immunomodulation through vascular changes, primarily by enhancing vascular permeability and recruiting immune cells, has been studied for its role in altering immunosuppressive cytokine profiles and triggering an inflammatory response that can further attack the tumor28,39.

While all these strategies have been explored in non-CNS tumors, most research on ultrasound-induced anti-vascular effects in CNS tissue has focused on lesioning normal brain tissue.

The concept of using the mechanical forces generated by FUS and microbubbles to create lesions in normal brain tissue was initially proposed to address the challenges of thermal ablation of brain tumors, particularly complications related to skull heating29. By utilizing blood pool microbubbles and low-intensity ultrasound, this non-thermal approach confined the treatment effects to the vasculature. McDannold et al. demonstrated that this method could successfully target the base of the skull and create well-defined lesions while sparing nearby nerves. The sparing effect was due to myelinated nerves being less vascularized, leading to reduced microbubble concentration and, consequently, minimal bioeffects in these areas. Lesion formation was attributed to vascular damage or rupture with multiple microhemorrhages observed in the targeted area and subsequent ischemic necrosis or hemorrhagic necrosis29,40. Moreover, studies on the long-term impacts of brain lesioning found no evidence of unexpected, delayed effects41. One challenge with FUS and microbubble treatment is that vascular damage is observed in regions along the ultrasound beam that are outside the focal zone—that is, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) focal region in both axial and lateral directions. This pre-focal damage is thought to result from uneven distribution of microbubbles, ultrasound exposure surpassing the cavitation threshold along the beam path, or from cavitating bubbles that may block the propagation of ultrasound42. While this method has been investigated in normal brain tissue, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding its application and efficacy in CNS tumor treatment, particularly since it is not evaluated against the tumor’s pathological vascular structures, despite the method’s primary focus on the vasculature. The need to address the tumor’s vascular structure gains additional significance when noting that glioblastoma, the most aggressive and most common primary brain cancer43, presents with a highly heterogeneous and continually evolving microenvironment, one aspect of which is diversity in the vascular generation patterns44. While angiogenesis was long thought to be the sole mechanism for tumor vascularization, it is now understood that during the early oncologic phase of glioma and in moderately aggressive tumors both angiogenesis and vascular co-option play critical roles in tumor development44. Although vascular co-option was discovered nearly 30 years ago, its significance in cancer research has only recently been acknowledged45. Vascular co-option is a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-independent mode of tumor vascularization by which tumor cells occupy the abluminal side of the pre-existing vascular network of the host tissue and hijack the vessels to secure essential oxygen and nutrients and grow without formation of new vessels44,46. These vessels are structurally different from angiogenic vessels whose characteristics have facilitated numerous successful preclinical anti-tumor therapies in other organs.

Additionally, considering that creating lesions in the highly vascularized brain tissue requires substantially lower ultrasound exposure and is relatively more straightforward compared to other organs29,31,33, safety concerns arise for adjacent healthy CNS tissue when applying all the aforementioned anti-vascular anti-tumor strategies to CNS tumors. Therefore, this study aims to investigate vascular damage in a rat orthotopic model of intramedullary spinal cord tumor (IMSCT) and adjacent healthy tissue to comparatively analyse the vulnerability of these tissues to FUS-induced anti-vascular effects. IMSCTs are primary spinal cord tumors that arise inside the medullary canal of the spinal cord and invade spinal cord parenchyma47. These tumors share histopathological traits with their brain counterparts48 and, although they occur less frequently, they pose a significant clinical challenge because current therapeutic options often fall short, fail, or cause adverse side effects49. Moreover, with the majority of CNS tumor treatment research focusing on brain tumors, treatment of spinal cord tumors remains largely underexplored50.

Results

A total of 26 rats bearing F98 glioma tumors situated in the spinal cord were treated with FUS and microbubbles at non-derated pressure levels of 0, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.2 MPa. In each animal, both the tumor tissue and the adjacent healthy tissue were subjected to treatment. Tissue samples were collected 24 h post-treatment for histological analysis.

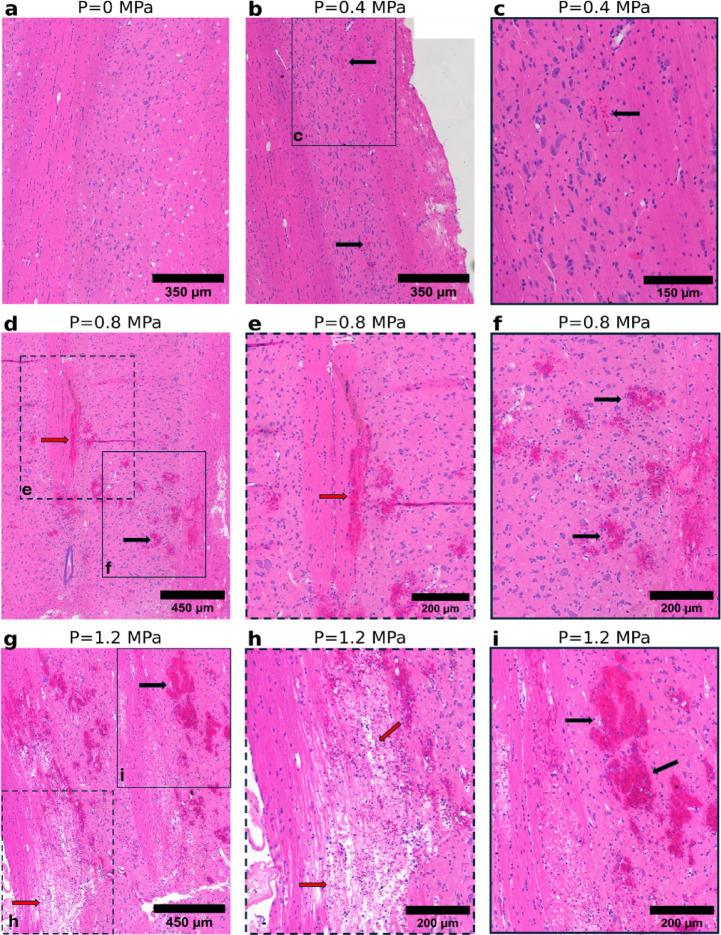

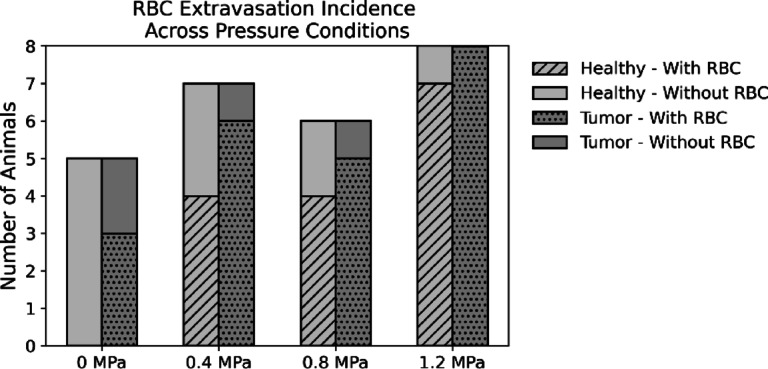

Histological analysis of H&E-stained sections of the treated healthy tissue demonstrated pronounced morphological changes across different pressure levels (Fig. 1). At sham level, the tissue structure remained well preserved, providing a clear baseline for comparison. At 0.4 MPa, a few animals exhibited red blood cell (RBC) extravasation, indicating early signs of vascular damage; however, in most animals the tissue architecture remained largely intact. Vascular damage observed at 0.4 MPa may be attributable to standing wave formation within the spinal canal resulting in an under-estimation of in situ pressure. At 0.8 MPa, there was a notable increase in damage characterized by more extensive RBC extravasation and the appearance of hemorrhagic pools. This progression may reflect a transition from stable to inertial cavitation occurring between 0.4 and 0.8 MPa under the specified experimental conditions, with the onset of inertial cavitation likely playing a key role in amplifying the extent and severity of vascular disruption. Integration of acoustic monitoring in future studies would provide greater insight into cavitation regimes during these treatments. At 1.2 MPa, extensive bleeding was observed; moreover, severe degradation of tissue structure, with notable disintegration of spinal cord tracts, was evident. Interestingly, in certain areas where the spinal cord tracts had disintegrated, the observable bleeding was less severe. Figure 2 summarizes the incidence of RBC extravasation across treatment groups.

Fig. 1.

Representative H&E-stained histological images of healthy tissue subjected to varying pressure conditions. (a) No structural changes. (b) Minimal RBC extravasation (black arrow). (c) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the solid box in (b); a limited number of RBCs are present. (d) A marked increase in RBC extravasation (black arrow) and appearance of hemorrhagic pools (red arrow). (e) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the dashed box in (d). (f) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the solid box in (d). (g) More extensive bleeding (black arrow) and severe structural damage to cord tracts (red arrow). (h) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the dashed box in (g) showcasing spinal cord tissue disintegration. (i) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the solid box in (g).

Fig. 2.

Incidence of RBC extravasation observed in tumor and healthy treated tissue across different pressure levels.

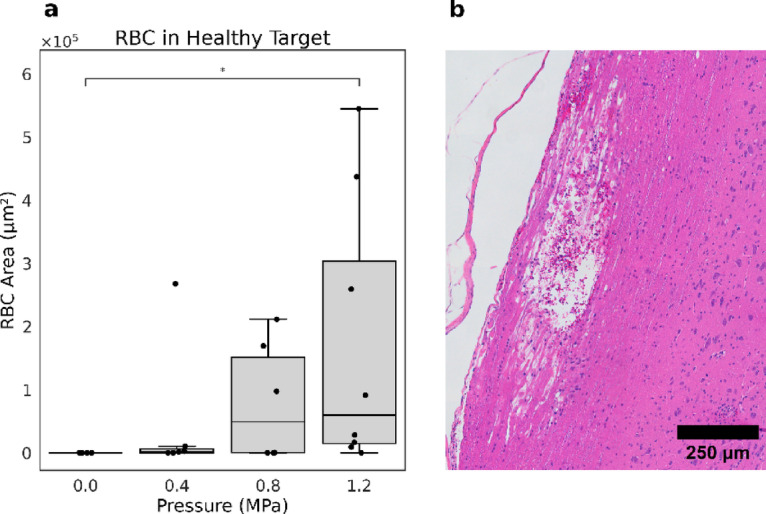

For quantitative analysis, the area of RBCs was measured across different pressure levels. The data indicated a clear increase in RBC area with rising ultrasound pressure (Fig. 3a); with a statistically significant difference between the 0 MPa and 1.2 MPa groups using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (0 ± 0 vs 1.73 × 105 ± 2.15 × 105, p = 0.015). One important observation was that disintegration of spinal cord tracts was observed in 50% of the animals treated at 1.2 MPa, and in these cases, the RBC area appeared markedly reduced (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of RBC area in healthy tissue across varying pressure conditions. (a) Boxplot showing the quantification of RBC area in treated healthy tissues, indicating an increase with rising pressure. (b) Representative H&E-stained histological image at 1.2 MPa illustrating extensive tissue damage, yet a reduced presence of RBCs in the damaged region.

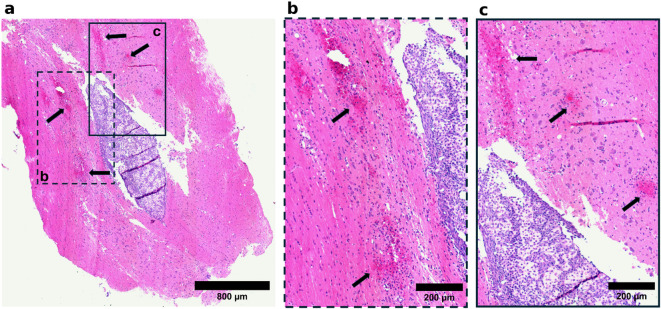

Tumor tissue, on the other hand, displayed some histological features such as red blood cell extravasation, hemorrhagic pools, cell ghosts, and proteinaceous fluid-filled cavities regardless of the applied pressure level (Fig. 4). Therefore, data interpretation relied on quantitative analysis to assess the severity and frequency of histopathological features and to identify potential trends across exposure conditions.

Fig. 4.

Representative H&E-stained histological images of tumor tissue illustrating key features across different treatment conditions. (a) RBC extravasation and proteinaceous fluid-filled cavities within the tumor tissue in the sham group. (b–d) Magnified views of the regions marked by dashed boxes in (a), showing (b) a proteinaceous fluid-filled cavity, (c) RBC extravasation, and (d) a proteinaceous fluid lake containing floating RBCs. (e) A representative tumor treated at 0.4 MPa, showing cavities filled with proteinaceous fluid and cell debris, with relatively well-defined margins. (f) A magnified view of the region marked by the dashed box in (e). (g) Another representative tumor treated at 0.4 MPa, exhibiting RBC extravasation. (h) A magnified view of the region marked by the dashed box in (g). (i) A representative tumor treated at 0.8 MPa. (j,k) Magnified views of regions marked by dashed boxes in (i), illustrating (j) a proteinaceous fluid-filled region and (k) RBC extravasation. (l) Another representative tumor treated at 0.8 MPa, demonstrating RBC extravasation. (m) A representative tumor treated at 1.2 MPa, showing cavities filled with proteinaceous fluid and floating RBCs. (n) A magnified view of the region marked by the dashed box in (m). (o) Another representative tumor treated at 1.2 MPa, showing cavities containing abundant cell debris. (p) A magnified view of the region marked by the dashed box in (o). The dotted brown lines in (a), (e), (g), (i), (l), (m), and (o) delineate the approximate tumor margins.

Quantitative analysis of the histology slides of the tumor tissue involved measuring the areas of proteinaceous fluid lakes with floating cell debris, and RBC regions (Fig. 5). In some tumor sections, proteinaceous fluid lakes had relatively sharp margins (observed in 1 animal at 0 MPa, 2 animals at 0.4 MPa and 4 animals at 1.2 MPa), suggesting a potential effect of the treatment as it could indicate that tissue damage might have opened up regions for fluid buildup51 (Fig. 4e,f). The area of proteinaceous fluid lakes with floating cell debris showed a slightly increasing trend with rising pressure levels (Fig. 5a); however, due to high variability of the data and the complex baseline pathology of tumor tissue, this trend is not particularly informative in assessing the extent of damage caused by the treatment.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative analysis of histopathological features in tumor tissue across varying pressure conditions. (a) Area of proteinaceous fluid-filled cavities containing cell debris in the tumor. (b) Area of RBCs normalized to the tumor size to adjust for the fact that larger tumors likely have a greater baseline of RBC presence. (c) The absolute RBC area in the tumor. The boxplots in (a), (b) and (c) do not indicate any statistically significant trends or meaningful patterns between these features and the applied pressure conditions. (d) RBC area in healthy and tumor tissue shown side by side for comparison, with healthy tissue exhibiting roughly an order of magnitude greater RBC presence. Direct statistical comparison of these groups may not be appropriate as it may imply a misleading equivalence between two biologically distinct environments. Tumor’s spontaneous leakage, an its elevated interstitial fluid pressure which can restrict RBC extravasation as well as differences in vascular structure and feeding patterns of tumor and healthy tissue further complicates direct comparison of RBC area in the two tissue types.

Similarly, RBC area quantification pointed to minimal hemorrhagic damage in the tumor, with no meaningful or statistically significant relationship between different groups, reinforcing the conclusion that the treatment’s impact on the tumor was limited, particularly in terms of vascular disruption (Fig. 5b). Moreover, as observed in Fig. 5d, the RBC extravasation in tumor tissue is approximately an order of magnitude lower than that observed in healthy tissue.

An additional example of this pattern is observed in the spinal cord in Fig. 6 (treated at 0.8 MPa), where, despite targeting the tumor, substantial hemorrhage and vessel rupture were evident in the healthy tissue on both sides of the tumor (Fig. 6b,c), while the tumor tissue itself remained largely intact. This further supports the differential response between healthy and tumor tissues under similar cavitation conditions.

Fig. 6.

The differential sensitivity of healthy tissue and tumor tissue to ultrasound treatment at 0.8 MPa. (a) Evidence of vascular damage (black arrows) in the healthy tissue surrounding the tumor, with the tumor tissue remaining intact, highlighting the increased sensitivity of the healthy tissue to the applied pressure. (b) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the dashed box in (a). (c) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the solid box in (a).

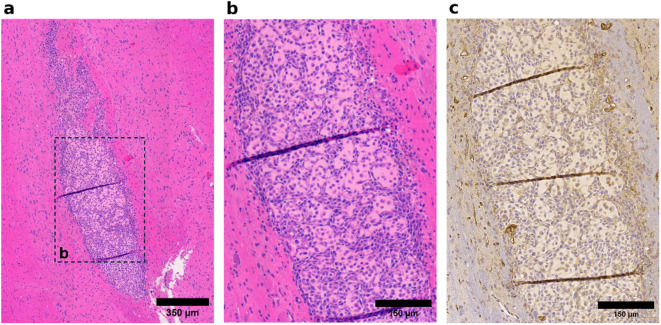

It is worth pointing out that the areas of RBCs and proteinaceous fluid lakes with cell debris in the experimental group treated at 0.8 MPa pressure are notably lower compared to the other groups, as shown in (Fig. 5a,b) respectively. This discrepancy likely stems from the inherent variability of the F98 glioma tumors, as a subset of tumors exhibited sparse vascularity and heterogeneous cellular morphology, with a mix of spindle-shaped cells and rounded cells with prominent cytoplasmic volumes interspersed in a proteinaceous matrix (Fig. 7). Despite the random assignment of animals to treatment groups, most tumors in the 0.8 MPa group happened to exhibit this phenotype. This inherent variability in the F98 tumors was only revealed upon histological analysis.

Fig. 7.

Representative histological images illustrating low vascularity and cellular heterogeneity in tumor tissue. (a) A representative tumor section showing low vascularity and heterogeneous cell morphology. (b) Higher magnification of the region boxed in (a), highlighting the varied cell morphology. (c) CD31-stained section adjacent to the H&E-stained section in the tissue block, demonstrating minimal detectable vascular structures.

TUNEL assay for detecting apoptotic cells did not reveal any TUNEL-positive nuclei in most of the tissue sections analyzed (12 out of 13 sections stained). The absence of TUNEL positivity in tissue sections such as those in Fig. 8a—which serves as an example of where positive staining was expected (as shown in Fig. 8b) but not observed—is likely due to the timing of tissue collection. While apoptosis has been observed as early as 4 h following FUS and microbubble-mediated lesioning in rabbit brain tissue52, that work used much higher pressures than studied here and it is possible that apoptosis could peak later at the lower pressures used in this study. In contrast, another study combining microbubble-mediated FUS and radiation therapy reported apoptotic activity at 72 h post-treatment in their FUS-only group, both in healthy rat brain and in F98 glioma tissue53. It is therefore possible that the 24 h interval may have been insufficient for apoptosis to progress to a level detectable by the TUNEL assay, and future studies should explore apoptosis over a range of timepoints.

Fig. 8.

TUNEL and H&E staining on immediately adjacent tissue sections treated at 1.2 MPa. (a) TUNEL-stained slide where apoptotic nuclei are expected but not present (black arrows), suggesting that 24 h was insufficient for apoptosis to be detectable. (b) H&E-stained slide from the adjacent section showing significant tissue damage.

To evaluate baseline vascularity, CD31 immunohistochemical analysis was performed in the sham group. As illustrated in Fig. 9, the CD31-positive area was significantly greater in healthy spinal cord tissue compared to tumor regions. Specifically, grey matter exhibited the highest vascularity (4.26 ± 0.71%), followed by white matter (1.43 ± 0.22%), whereas tumor tissue showed a reduced CD31-positive area (0.66 ± 0.27%). Statistical analysis revealed that both grey matter and white matter had significantly higher CD31+ areas compared to tumor tissue (p < 0.00001 and p = 0.048, respectively). These findings indicate a pronounced reduction in vascularity within the tumor microenvironment relative to the surrounding healthy tissue.

Fig. 9.

CD31-positive area as an indicator of vascularity in grey matter, white matter, and tumor tissue. Vascularity is significantly higher in healthy tissue (both grey and white matter) compared to tumor (****p < 0.00001, *p < 0.05).

Representative images in Fig. 10 further support these findings, visually demonstrating the higher vascularity in healthy regions compared to tumor tissue. Notably, vessel diameters were measured from selected vessels across several representative fields. These measurements revealed that vessels within tumor tissue tended to have larger diameters compared to those in healthy spinal cord regions (Fig. 10c,f,i). The observed difference was consistently evident in the sampled areas, suggesting distinct vascular remodeling within the tumor microenvironment.

Fig. 10.

CD31-positive vessels stained with DAB, along with selected vessel diameter measurements to illustrate differences in vessel size across tissue types. (a) Healthy tissue, dark brown staining indicates endothelium. (b) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the dashed box in (a); increased vascularity is observed in the grey matter on the right side of the red dashed line, compared to the white matter on the left. (c) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the solid box in (b); vessel diameters are consistently below 10 µm in this sample. (d) Tumor tissue exhibiting high cellularity with densely packed tumor cells. (e) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the dashed box in (d). (f) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the solid box in (e); vessel diameters are consistently above 10 µm in this sample. (g) Tumor tissue exhibiting heterogeneous cell populations and proteinaceous fluid. (h) Higher magnification of the region outlined by the dashed box in (g). The red dashed line delineates the tumor boundary. Increased vascularity is observed in the healthy tissue adjacent to the tumor. (i) Higher magnification of the area marked by the solid box in (h), showing a single large-diameter vessel within the tumor.

The collective findings indicate that the clear pressure-dependent relationship observed in the treated healthy tissue was absent in the tumor sections, suggesting that the observed alterations are more likely due to tumor’s intrinsic pathological processes, such as necrosis, and the compromised vascular integrity commonly observed in aggressive gliomas. Some of the observed alterations could also arise from tissue handling or processing artifacts rather than the applied cavitation. Although the possibility of some FUS-induced tissue damage in tumors cannot be entirely ruled out, quantitative analysis did not reveal any consistent or measurable evidence of such effects.

Discussion

This work examines FUS-induced anti-vascular effects at varying pressure levels in an orthotopic F98-induced glioma model in the spinal cord. The objective of the study was to compare the treatment responses between tumor tissue and adjacent healthy tissue. Our findings revealed pressure-dependent damage in the healthy tissue, while the tumor tissue largely resisted the treatment. In healthy tissue, the histopathological features observed—RBC extravasation, hemorrhagic pools, tissue disintegration—represent a spectrum of injury severity. RBC extravasation typically reflects early vascular leakage; hemorrhagic pools indicate more extensive rupture and tissue disintegration reflects a very severe damage to the spinal cord.

While a significant difference was found between the RBC area in 0 MPa and 1.2 MPa groups in healthy tissue, one potential explanation for the absence of statistical significance between the 1.2 MPa group and the groups treated at lower pressures relates to the extensive disruption of spinal cord tracts that likely reduced the overall observable RBC area in the affected regions. Although the exact mechanism underlying this reduction remains uncertain, it may be attributed to partial clearance of extravasated RBCs during tissue processing, as the tissues treated at 1.2 MPa may have been too severely damaged to retain extravasated blood. Nevertheless, it suggests that the RBC area at 1.2 MPa may underestimate the true extent of damage. It is also worth noting that the data variability observed in the boxplot in Fig. 3a may have contributed to the lack of statistical significance between other groups. This data variability may be attributed to anatomical variability, as small differences in targeting can greatly change the insertion loss of the spine54 depending on if the sound travels through bone or through intervertebral spaces. An additional limitation is the somewhat coarse (100 µm) intervals for our histology analysis. It is possible that some RBC extravasation events occurred between sections but were not captured by our analysis. Therefore, the absence of observable RBC extravasation does not necessarily indicate a lack of treatment effect. Nevertheless, in summary, these observations revealed a pressure-dependent compromise of vascular integrity in treated healthy tissue.

However, in tumor tissue, observed features are characteristic of the baseline pathology of the F98 glioma model and were present even without treatment (0 MPa). The abnormal vascular structure, high permeability, spontaneous hemorrhage, and necrotic regions intrinsic to the tumor result in the presence of these histopathological findings independent of applied ultrasound pressure. While some FUS-induced effects may be present, the presence of similar abnormalities in sham-treated animals makes it difficult to attribute them solely to treatment. Quantitative analysis was therefore used to explore potential trends, but no statistically significant, meaningful or dose-dependent relationship was found between FUS exposure and histological changes in tumor tissue, so the available data do not allow us to definitively distinguish treatment effects from baseline tumor pathology.

The lower sensitivity of the F98-induced tumor tissue to FUS-induced anti-vascular therapy could be attributed to the tumor’s other modes of vascularization, beyond angiogenesis, as well as its lower vascularity.

As noted earlier, in the process of vascular co-option, tumor cells migrate along the pre-existing vessels and exploit them to secure their metabolic needs46. Migration of tumor cells along the co-opted vessels as a trail55 facilitates motility45, invasion, and tumor growth in an infilterative manner; however, tumor growth is usually less destructive with tumors often respecting and reflecting the histological structure of the host organ56. Co-opted vessels also retain certain features of their original structure. Notably, they preserve the mature state of the basement membrane with substantial pericyte coverage56. However, they still undergo some structural and functional changes. Firstly, tumor cells insert themselves between pericytes and astrocytes56, detaching the astrocyte foot processes from the blood vessels, which compromises the endothelial tight junctions and leads to increased permeability of the co-opted vessels44,57,58. Additionally, co-opted vessels undergo lumen enlargement to enhance blood flow and sustain the continuous growth of the tumor59.

Vascular co-option may result in reduced sensitivity of tumor vessels to treatment with FUS and microbubbles due to the robust structure of the co-opted vessels and their lumen enlargement. To explain further, firstly, it is widely accepted in the field of FUS with microbubble-mediated antivascular therapy that tumor vessels are preferentially more sensitive to vascular damage due to their underdeveloped and physically defective structure33. However, most studies in this field have been conducted in less vascularized organs where tumors predominantly rely on angiogenesis for growth22,25,33,34, and angiogenic vessels often have incomplete or absent basement membranes with deficiencies in smooth muscle cells and pericytes, which makes them heavily dependent on endothelial cells for structural support60. Consequently, simply damaging endothelial cells may make vessels more sensitive to mechanical damage. However, the more robust co-opted vessels, which benefit from a mature basement membrane61, exhibit greater resistance to vascular damage compared to angiogenic vessels. Zheng Liu et al. demonstrated that while endothelial damage could be induced in larger vessels, it did not lead to vessel obstruction or disruption33. This finding confirms that a mature basement membrane, in contrast to the primitive structure of angiogenic vessels, where endothelial damage may result in significant vessel disruption, can prevent major damage to the vessel even if the endothelial cells are compromised.

Secondly, larger vessels are more resistant to cavitation-mediated vascular bioeffects23,33,62, partly because the localized shear, contact, and acoustic forces63 exerted by micron-sized microbubbles are less pronounced in wider vessels. Therefore, co-opted vessels are less vulnerable to mechanical disruption due to their lumen enlargement.

In F98-induced rodent glioma tumors, Doblas et al. reported that no new vessels were formed during development of these tumors; rather, the diameter of pre-existing vessels expanded by up to 45%64. Similarly, prior research on intracerebral transplantation of F98 tumors indicates that their progression depends on the expansion of existing vessels rather than generation of new capillaries65. These findings suggest absence of angiogenic vessels and confirm lumen enlargement in our tumor model, both of which contribute to reduced sensitivity of these tumors to treatment with ultrasound and microbubbles.

Besides vascular co-option, which may serve as a contributing factor in a tumor’s reduced sensitivity, F98-induced tumors exhibit low vascularity, as confirmed by CD31 immunohistochemical analysis in the sham group. A lower density of vessels within the treatment field—assuming microbubbles are evenly distributed—leads to fewer bubbles and a reduced cavitation dose, thus limiting the damage level.

This aligns with the findings reported by Fletcher et al., where they investigated combining microbubble-mediated FUS and radiation therapy and demonstrated that the low vascular density and reliance on pre-existing vessels in F98 tumors can limit the efficacy of vascular-targeted therapies53.

It is important to acknowledge the possibility of other underlying mechanisms that have yet to be considered. The inherent heterogeneity of F98-induced tumors, and small group sizes in the present study, make it challenging to identify and isolate subtle effects that could help explain the mechanisms involved.

The differential response highlights the complexity of treating tumor tissues with FUS and microbubbles without inadvertently damaging the surrounding vitally important healthy CNS tissue. It has been established that optimizing the required physical energy to selectively destroy tumor vasculature without harming surrounding healthy tissue requires meticulous attention even in non-CNS tumors where the tumor vasculature is more sensitive to the treatment33. In the context of CNS tumors, this challenge is magnified due to the delicate nature of the surrounding healthy tissue.

However, our findings suggest that achieving the desired therapeutic effects in CNS tumors may require strategies to enhance cavitation activity specifically within tumor vasculature. This indicates that to leverage all anti-tumor anti-vascular strategies for CNS tumors, additional targeting methods are required. Approaches such as using nanodroplets, which remain acoustically inactive until the ultrasound exposure exceeds the acoustic droplet vaporization threshold, or antibody-targeted microbubbles that selectively bind to tumor-specific vascular markers, offer potential for enhanced efficacy66.

Moreover, these findings raise safety concerns even at lower, non-inertial ultrasound exposures. The cavitation dose required for effective BBB or BSCB opening could still be high enough to induce unintended damage in the surrounding healthy tissue, necessitating careful optimization of treatment parameters to balance efficacy and safety.

Limitations

In this study, there are several methodological considerations that should be acknowledged.

Firstly, male and female animals were initially sourced in balanced numbers and randomly assigned to treatment groups. However, losses due to surgical or anesthesia-related complications resulted in slight sex imbalances across groups, which we acknowledge as a limitation of the study.

Secondly, the in-situ pressure estimation in our study relied on a previously reported transmission rate measured at a slightly different frequency (551 kHz) and anatomical region (lower thoracic to lumbar), whereas our sonications were performed at 580 kHz in the mid-thoracic spinal cord. Although we expect transmission to fall within a similar range, direct measurement under our specific experimental conditions would improve the accuracy of pressure estimation. In addition, we did not implement a method to monitor or control the FUS dose delivered at each sonication site. The incorporation of real-time feedback or exposure control systems would allow for more consistent and reproducible dosing. In this context, it is important to note that for tumor-targeted sonications, the laminectomy performed during tumor inoculation created a partial acoustic window through the vertebral bone. This likely enabled more efficient and consistent ultrasound transmission to the tumor compared to the intact bone overlying healthy spinal cord regions. Therefore, even if some variability in exposure occurred, it is reasonable to assume that the tumors received at least equivalent, if not greater, acoustic energy relative to adjacent healthy tissue. The observation that tumors nonetheless exhibited lower levels of vascular disruption supports our primary conclusion that glioma tissue is less sensitive to FUS and microbubble treatment.

Additionally, spinal cord gliomas are known to share histopathological characteristics with their brain counterparts, and our observations of reduced vascularity and larger-diameter vessels within spinal cord F98 tumors align with findings reported by Doblas et al. in brain-implanted F98 models64. These similarities suggest a potentially comparable vascular phenotype. However, given inherent differences in the local microenvironment between the brain and spinal cord, this comparison should be interpreted with appropriate caution and is acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

Another consideration is that histological analysis was based on the selection of the section showing the most pronounced pathological features. Given the 100 µm interval between sections and the highly localized nature of cavitation-induced damage, some effects may have occurred between sections and gone undetected. Nonetheless, the same selection strategy was applied uniformly across all experimental groups, enabling reliable relative comparisons. We acknowledge, however, that focusing on the most affected section may introduce some degree of bias and represents a limitation of the current analysis.

We also acknowledge that after treatment, it was not possible to definitively attribute any observed decline in locomotor function to ultrasound treatment, as tumor progression itself often led to rapid deterioration, including mobility impairment or even partial paralysis within a day. No adverse events were clearly attributable to the treatment; however, the relatively short monitoring period following exposure may also have limited the detection of delayed or subtle treatment-specific effects.

Lastly, we acknowledge that future work could incorporate more comprehensive indicators of tissue damage, including the quantification of apoptotic cells, as well as methods to assess vascular integrity and their structural robustness, to provide a more complete understanding of the biological response.

Conclusions

The progressive increase in damage observed in healthy spinal cord tissue with rising FUS pressure, contrasted with the absence of treatment-induced damage in F98 glioma tumors, demonstrates the greater sensitivity of healthy CNS tissue to anti-vascular bioeffects. The reduced sensitivity of F98 tumors, driven by their lower vascularity and their likely reliance on the more robust pre-existing vessels, underscores the need for more precise targeting when using pressures near or above the inertial cavitation threshold (i.e., high-pressure exposures). In contrast, lower-pressure exposures—below the inertial cavitation threshold and typically considered safe for BBB or BSCB opening and drug delivery—may still pose a risk to adjacent healthy tissue, highlighting the importance of careful safety evaluation even at these levels.

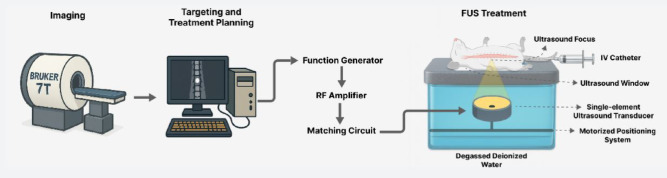

Methods

In short, MRI-guided FUS treatments utilizing house-made microbubbles were delivered at varying pressures, followed by histological analyses to assess tissue morphology and apoptotic activity. All methods and procedures described herein are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines67. A simplified schematic of the experimental setup and workflow is shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Simplified schematic of the experimental setup and workflow.

Bubble fabrication and characterization

Microbubble fabrication was based on the method described by Johanssen et al.68, with extensive modifications. 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL, USA) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL, USA) were solubilized in chloroform, mixed at a molar ratio of 9:1, and subsequently heated on a hot plate to evaporate the chloroform, leaving a lipid film behind. The lipid film was then dissolved in propylene glycol (PG) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) under constant stirring and heating above the DSPC transition temperature. After 1 h, the solution was added dropwise to a preheated solution composed of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) ensuring the volume ratio of PBS/PG/glycerol was maintained at 16:3:1. The resulting lipid cocktail underwent gas exchange with decafluorobutane (DFB) (Fluoromed, Round Rock, TX, USA) and agitation using a VialMix (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA) for 45 s to form microbubbles. The microbubbles were allowed to rest on ice for 20 min before administration.

To characterize the microbubbles, their size and concentration were measured using Beckman Coulter’s Multisizer 4e (Beckman Coulter Canada, LP, Mississauga, ON, Canada) on every experiment day. The microbubbles had a mean diameter of 1.00 ± 0.85 µm. Prior to injection, microbubbles were diluted 1:10, and animals received a standardized dose of 2.4 × 107 microbubbles per 100 g body weight. The injection volume, adjusted according to the microbubble concentration on each day and the animal’s weight, ranged from approximately 0.1 to 0.15 mL.

Animal care practices

Animal Use Protocols were approved by the Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) animal care committee and complied with all regulations and guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, and all experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines. The rat housing room at SRI was equipped to maintain environmental conditions conducive to rat physiology, ensuring a controlled temperature of 18–22 °C, humidity levels of 40–60%, and a reversed light cycle. Standard polycarbonate shoebox cages furnished with corncob bedding for absorbency and odor control, crinkled paper for environmental enrichment and nesting, and a PVC tube for shelter were used to accommodate 2–3 rats of the same sex before the surgery. Each rat was individually caged after the surgery in cages with iso pad bedding to minimize the risk of introducing dust to the surgery site and to facilitate monitoring of bodily discharges. Food (Teklad Irradiated Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and water were available ad libitum. After the surgery, rats were provided with soft food, either chow pellets soaked in water or in Nestlé BOOST® nutritional energy drink, if weight loss exceeded 10%.

Cell culture

F98 glioma cells, originally isolated from a rat brain with undifferentiated malignant glioma, were sourced from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with 4.5 g/L glucose, L-glutamine and sodium pyruvate (Wisent 319-005-CL, St-Bruno, QC, Canada) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Wisent 080-450, St-Bruno, QC, Canada). The culture environment was regulated to sustain a constant temperature of 37 °C and a CO2 level of 5%. Subculturing was performed every 1–3 days at a confluency of 80–90% using 0.05% trypsin and 0.53 mM EDTA (Wisent 325–542-EL, St-Bruno, QC, Canada). On the day of the surgery, cells were counted using a hematocytometer, concentrated at 4 × 106 cells/mL, and suspended in Matrigel (Corning, NY, USA) at a 1:1 ratio just prior to injection to enhance retainment of the cells at the intended anatomical location.

Tumor inoculation

Male and female Fischer 344 rats (125–150 g) were obtained from Envigo (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and were allowed to acclimatize for one week before the tumor inoculation surgery. A total of 16 male and 10 female rats were used to enhance the generalizability of the findings. While sex differences were not the focus of this study, the inclusion of both sexes helps account for biological variability and supports the translational relevance of the results.

The surgery was performed using a slightly tailored version of the model developed by Caplan et al.69. In summary, the rats were anesthetized under isoflurane at 2–3%, and received subcutaneous injections of analgesics, antibiotics, and normal saline for hydration. In the surgery field, rats were positioned prone, the spinous process of the second thoracic vertebra (T2) was located, and the thoracic vertebra located 1 cm caudal to T2 was marked using a tissue marker. A longitudinal cut was made in the caudal direction within the thoracic region, the underlying tissues were retracted laterally, and the spinous process of the marked vertebra was removed to expose the spinal cord. Using a stereotactic frame, a Hamilton syringe loaded with a total of 10,000 F98 cells suspended in Matrigel was advanced through the intervertebral space until the needle contacted the dorsal surface of the spinal cord. This contact served as a reference point to control the injection depth, which was set at 1.5 mm into the cord. The injection was delivered over 1 min, after which the needle was kept in place for 5 min to prevent cells from refluxing along the needle track. The paravertebral tissues were stitched using 3-0 sutures, and the skin incision was closed using 4-0 sutures.

Pre and post-operative care involved a combination of systemic and topical treatments to support recovery and prevent infection. Rats received subcutaneous injections of Baytril (enrofloxacin, 10 mg/kg; Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, IN, USA) and Metacam (meloxicam, 2 mg/kg; Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) prior to surgery and daily for two days post-operatively. Vetergesic (buprenorphine, 0.018 mg/rat; Ceva Santé Animale, Libourne, France) was administered once immediately before surgery for analgesia, and Dexamethasone (2 mg/kg; Sandoz, Holzkirchen, Germany) was given once the day after surgery to reduce inflammation. A topical antibiotic, either Polysporin Complete (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or Flamazine (Smith & Nephew, Watford, UK), was applied to the surgical site immediately after surgery and as needed throughout the recovery period. Supportive care also included the provision of soft food and daily monitoring to assess motor function, abnormal discharges, and signs of pain or distress. Treatment was performed 7–10 days after tumor inoculation surgery.

Behavioral assessment

To quantitatively rate the rats’ locomotor behavior, the 21-point Basso–Beattie–Bresnahan locomotor scoring system was used (BBB Scoring)70. This scoring system was originally developed to evaluate locomotor function in rat models of thoracic spinal cord injury, making it an appropriate choice for assessing locomotor changes—including joint movements, hindlimb movements, stepping, coordination, trunk stability and position, paw placement, and tail position—after the tumor inoculation surgery. To conduct the assessment, each rat was individually exposed to an open-field environment for 4 min and its movement patterns were recorded. The rats were assessed daily for 1 week prior to surgery to ensure a healthy baseline and to acclimate the rats to handling and moving about the open-field environment without showing signs of fear. Post-surgery recordings continued until the FUS treatment.

MRI

To enable MR-guided targeting and treatment monitoring, rats underwent imaging using a 7 T MRI system (BioSpec 70/30 USR; Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a volume coil. Gadolinium-based contrast agent (0.1 mL/kg; Gadovist, Bayer Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada) was administered intravenously prior to imaging. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images were acquired using a fast spin echo sequence (TE = 5.5 ms, TR = 500 ms, 12 averages, rare factor = 4, FOV = 50 × 40 mm, pixel size = 0.2 × 0.2 mm, slice thickness = 0.5 mm). This setup provided the spatial resolution and contrast required to visualize the rat spine anatomy and localize the tumor by highlighting gadolinium extravasation through the tumor’s leaky vasculature before the treatment.

FUS treatment

For FUS treatment, animals were anesthetized and kept under anesthesia using 2–3% isoflurane in sterile air, breathing through a nose cone during the procedure. The back hair was shaved with an electric razor and then treated with a depilatory cream to ensure thorough removal of fur, minimizing bubbles and optimizing ultrasound coupling. A 22-gauge catheter was inserted into the tail vein of the animal to allow intravenous injection of MRI and ultrasound contrast agents. All injections were administered as bolus doses, each followed by a 0.5 mL saline flush.

Each animal received FUS exposures at two anatomically distinct locations: the tumor site and an adjacent region of healthy spinal cord tissue. The healthy tissue target was positioned 1.2–1.7 cm away from the tumor site in the lateral plane of the transducer and at least ~ 1 cm from the tumor margin, as confirmed on contrast-enhanced MRI. Microbubbles were administered immediately prior to the first sonication and the second treatment site was sonicated one minute later.

To minimize potential bias associated with treatment order, animals were randomly assigned to receive either the tumor or healthy tissue treatment first. This resulted in 11 tumor-first and 10 healthy-first treatments across the experimental groups. Specifically, in the 0.4 MPa group, 4 animals received tumor-first and 3 healthy-first; in the 0.8 MPa group, 3 were tumor-first and 3 healthy-first; and in the 1.2 MPa group, 4 were tumor-first and 4 healthy-first.

A spherically focused single-element PZT transducer with a center frequency of 580 kHz (75 mm diameter, F# 0.8) was mounted in a 3-axis preclinical FUS system (FUS Instruments, Toronto, ON, Canada). The system featured a tank filled with degassed deionized water housing the transducer, which was mounted on a motorized three-dimensional positioning arm capable of adjusting its position within the tank. The setup was completed with a lid equipped with an acoustic window. Animals were placed supine on a versatile sled compatible with both the imaging and the treatment systems, with their backs positioned on the acoustic window. This integration allowed for precise co-registration of FUS system coordinates with MRI coordinates, enabling targeted FUS delivery under MR guidance. FUS was delivered in 10 ms pulses with a pulse repetition frequency of 1 Hz (1% duty cycle) with varying pressures (free-field) of 0 (n = 5), 0.4 (n = 7), 0.8 (n = 6), and 1.2 MPa (n = 8) to the tumor and the adjacent healthy tissue, each with two treatment spots spaced 1 mm apart vertically. Based on a previously measured mean acoustic transmission through the rat spine (in mid to lower thoracic and lumbar regions) of 67 ± 15% at the relevant frequencies71, the estimated in situ pressure ranges in the mid-thoracic region were 0 MPa (MI = 0), 0.21–0.33 MPa (MI = 0.28–0.43), 0.42–0.66 MPa (MI = 0.55–0.87), and 0.62–0.98 MPa (MI = 0.81–1.29), respectively.

Additionally, as part of the study design, the animals were randomized using a random number generator prior to each experiment day to ensure unbiased allocation and control for potential confounders.

Tissue processing

Twenty-four hours post-treatment, animals underwent transcardial perfusion with saline for 5–7 min followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for an additional 5–7 min. After perfusion, the harvested tissues were immersed in 10% NBF for at least 24 h to allow to ensure thorough fixation. The formalin-fixed spinal cord tissue was then harvested, paraffin embedded, and sliced coronally, procuring 5 μm thick slices at 100 μm intervals. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on these sections to observe cell morphology and structure, RBC extravasation, and hemorrhagic pools.

TUNEL staining was performed on sections immediately adjacent to the H&E-stained slides using the DeadEnd™ Colorimetric TUNEL System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), which stains apoptotic nuclei dark brown for visualization by light microscopy. Sections were selected across all FUS pressure levels, including the sham group. The number of slides stained per group was as follows: Sham—3 slides; 0.4 MPa—3 slides; 0.8 MPa—4 slides; and 1.2 MPa—6 slides.

CD31 immunohistochemistry was performed on sections adjacent to those used for H&E and TUNEL staining in sham group to visualize vascular endothelial structures, following antigen retrieval. A rabbit monoclonal anti-CD31 antibody [EPR17259] (Abcam, ab182981; Cambridge, UK; 1:1000) was used in conjunction with the Mouse and Rabbit Specific HRP/DAB IHC Detection Kit (Abcam, ab236466; Cambridge, UK). The resulting DAB signal marked endothelial cells with a brown chromogen, allowing vessel visualization under light microscopy.

H&E- and TUNEL-stained slides were digitized using a Zeiss AxioImager microscope (Zeiss, Berlin, Germany), while CD31-stained slides were digitized using a TissueScope LE scanner (Huron Digital Pathology, St. Jacobs, Ontario, Canada). For each treatment target, the H&E-stained slide exhibiting the most prominent histopathological features was selected for analysis.

Image processing for H&E stained slides was subsequently performed using Fiji72 and the Labkit73 plugin, which enabled semi-automated segmentation of areas of interest such as RBC and proteinaceous fluid-filled cavities. Initially, a few representative areas of interest and background regions were manually highlighted within each image. Labkit then used this training data to automatically identify and generate masks for similar features across the image using its pixel classifier. The masks were then refined manually to ensure all relevant areas were correctly identified without unintended inclusions. The refined masks were used for quantitative analysis of the areas of interest in H&E-stained slides. TUNEL-positive cells were counted manually using the manual segmentation feature of Labkit.

CD31 immunohistochemical analysis was performed using QuPath74 (version 0.5.1). A pixel classifier based on a thresholding approach in the DAB channel was applied to identify CD31-positive areas. For each animal in the sham group, three anatomically distinct regions—the grey matter and white matter in the thoracic spinal cord, as well as the tumor—were selected and analyzed individually. The CD31-positive area was calculated as a percentage of the total tissue area within each region of interest, providing a comparative measure of vascularity across the different tissue types.

Blinding was applied to the interpretation of histological slides. However, quantification of histological features was not blinded, as it was performed using a standardized, semi-automated image analysis workflow involving objective metrics applied uniformly across all samples to minimize bias.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Python (SciPy) to evaluate differences in histological and immunohistochemical measurements across experimental conditions. For the analysis of H&E-stained sections across the four pressure groups, a non-parametric one-way Kruskal–Wallis H-test was used due to the non-normal distribution of the data, as confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. When significant differences were detected, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons.

For CD31 immunohistochemical analysis of vascularity in the sham group, where data were normally distributed, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare CD31-positive area among grey matter, white matter, and tumor regions. Tukey’s post hoc test was applied to determine pairwise differences.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to Shawna Gross Rideout for performing the surgeries essential to this study, Vishwaja Mewada for her veterinary expertise and support with animal-related procedures, Dr. Eleanor Stride and her team for their support in advancing the microbubble fabrication process, Jennifer Sun for the histology processing, and Sadiyah Saleh and Andy Assis for their valuable assistance with histology slide digitization. Support for this work was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT162112) and the Canada Research Chairs program.

Author contributions

M.A.O. and M.M. designed the study. M.M. and D.M.C performed experiments. C.H. conducted the histological interpretation. M.M. performed data analysis, prepared figures and drafted the manuscript. M.A.O. assisted with interpretation of data and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

M.A.O. holds industry partnered funding (Ontario Research Fund) with FUS Instruments as an industry partner. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dijkmans, P. A. et al. Microbubbles and ultrasound: From diagnosis to therapy. Eur. J. Echocardiogr.5, 245–246 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland, C. K. & Apfel, R. E. Fundamentals of the mechanical index and caveats in its application. J. Acoust. Soc. Am.105, 1324 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhury, S. M., Abou-Elkacem, L., Lee, T., Dahl, J. & Lutz, A. M. Ultrasound and microbubble mediated therapeutic delivery: Underlying mechanisms and future outlook. J. Control. Release326, 75–90 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, T.-Y., Wilson, K. E., Machtaler, S. & Willmann, J. K. Ultrasound and microbubble guided drug delivery: Mechanistic understanding and clinical implications. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol.14, 743–752 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMahon, D., O’Reilly, M. A. & Hynynen, K. Therapeutic agent delivery across the blood–brain barrier using focused ultrasound. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng.23, 89–113 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher, S.-M.P. & O’Reilly, M. A. Analysis of multifrequency and phase keying strategies for focusing ultrasound to the human vertebral canal. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control65, 2322–2331 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dotiwala, A. K., McCausland, C. & Samra, N. S. Anatomy, head and neck, blood brain barrier (2018). [PubMed]

- 8.Jin, L.-Y. et al. Blood–spinal cord barrier in spinal cord injury: A review. J. Neurotrauma38, 1203–1224 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song, K.-H., Harvey, B. K. & Borden, M. A. State-of-the-art of microbubble-assisted blood–brain barrier disruption. Theranostics8, 4393 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padilla, F., Brenner, J., Prada, F. & Klibanov, A. L. Theranostics in the vasculature: bioeffects of ultrasound and microbubbles to induce vascular shutdown. Theranostics13, 4079 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mainprize, T. et al. Blood–brain barrier opening in primary brain tumors with non-invasive MR-guided focused ultrasound: a clinical safety and feasibility study. Sci. Rep.9, 321 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anastasiadis, P. et al. Localized blood–brain barrier opening in infiltrating gliomas with MRI-guided acoustic emissions–controlled focused ultrasound. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.118, e2103280118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park, S. H. et al. Safety and feasibility of multiple blood–brain barrier disruptions for the treatment of glioblastoma in patients undergoing standard adjuvant chemotherapy. J. Neurosurg.134, 475–483 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng, Y. et al. MR-guided focused ultrasound enhances delivery of trastuzumab to Her2-positive brain metastases. Sci. Transl. Med.13, eabj4011 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karakatsani, M. E. et al. Focused ultrasound mitigates pathology and improves spatial memory in Alzheimer’s mice and patients. Theranostics13, 4102 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasca-Salas, C. et al. Blood–brain barrier opening with focused ultrasound in Parkinson’s disease dementia. Nat. Commun.12, 779 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrahao, A. et al. First-in-human trial of blood–brain barrier opening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat. Commun.10, 4373 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith, P., Ogrodnik, N., Satkunarajah, J. & O’Reilly, M. A. Characterization of ultrasound-mediated delivery of trastuzumab to normal and pathologic spinal cord tissue. Sci. Rep.11, 4412 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fletcher, S.-M.P., Choi, M., Ogrodnik, N. & O’Reilly, M. A. A porcine model of transvertebral ultrasound and microbubble-mediated blood-spinal cord barrier opening. Theranostics10, 7758 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero, A.-S. et al. Effect of ultrasound-mediated blood-spinal cord barrier opening on survival and motor function in females in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. EBioMedicine106, 105235 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne, A. H. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound to increase localized blood-spinal cord barrier permeability. Neural Regen. Res.12, 2045–2049 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todorova, M. et al. Antitumor effects of combining metronomic chemotherapy with the antivascular action of ultrasound stimulated microbubbles. Int. J. Cancer132, 2956–2966 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho, Y.-J., Wang, T.-C., Fan, C.-H. & Yeh, C.-K. Current progress in antivascular tumor therapy. Drug Discov. Today22, 1503–1515 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood, A. K. W., Schultz, S. M., Lee, W. M. F., Bunte, R. M. & Sehgal, C. M. Antivascular ultrasound therapy extends survival of mice with implanted melanomas. Ultrasound Med. Biol.36, 853–857 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, P. et al. A novel therapeutic strategy using ultrasound mediated microbubbles destruction to treat colon cancer in a mouse model. Cancer Lett.335, 183–190 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenbrey, J. R. et al. US-triggered microbubble destruction for augmenting hepatocellular carcinoma response to transarterial radioembolization: a randomized pilot clinical trial. Radiology298, 450–457 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore-Palhares, D. et al. Radiation enhancement using focussed ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles for head and neck cancer: A phase 1 clinical trial. Radiother. Oncol.198, 110380 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curley, C. T., Sheybani, N. D., Bullock, T. N. & Price, R. J. Focused ultrasound immunotherapy for central nervous system pathologies: Challenges and opportunities. Theranostics7, 3608 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDannold, N., Zhang, Y.-Z., Power, C., Jolesz, F. & Vykhodtseva, N. Nonthermal ablation with microbubble-enhanced focused ultrasound close to the optic tract without affecting nerve function. J. Neurosurg.119, 1208–1220 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goertz, D. E. An overview of the influence of therapeutic ultrasound exposures on the vasculature: High intensity ultrasound and microbubble-mediated bioeffects. Int. J. Hyperth.31, 134–144 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, J. et al. Selective depletion of tumor neovasculature by microbubble destruction with appropriate ultrasound pressure. Int. J. Cancer137, 2478–2491 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood, A. K. W. et al. The disruption of murine tumor neovasculature by low-intensity ultrasound—Comparison between 1-and 3-MHz sonication frequencies. Acad. Radiol.15, 1133–1141 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, Z. et al. Disruption of tumor neovasculature by microbubble enhanced ultrasound: A potential new physical therapy of anti-angiogenesis. Ultrasound Med. Biol.38, 253–261 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goertz, D. E. et al. Antitumor effects of combining docetaxel (taxotere) with the antivascular action of ultrasound stimulated microbubbles. PLoS ONE7, e52307 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eichhorn, M. E., Strieth, S. & Dellian, M. Anti-vascular tumor therapy: recent advances, pitfalls and clinical perspectives. Drug Resist. Updates7, 125–138 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood, A. K. W. et al. The antivascular action of physiotherapy ultrasound on murine tumors. Ultrasound Med. Biol.31, 1403–1410 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma, D. & Czarnota, G. J. Role of acid sphingomyelinase-induced ceramide generation in response to radiation. Oncotarget10, 6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai, P. et al. Breast tumor response to ultrasound mediated excitation of microbubbles and radiation therapy in vivo. Oncoscience3, 98 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao, L. et al. An experimental study: Treatment of subcutaneous c6 glioma in rats using acoustic droplet vaporization. J. Ultrasound Med.42, 1951–1963 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang, Y., Vykhodtseva, N. I. & Hynynen, K. Creating brain lesions with low-intensity focused ultrasound with microbubbles: A rat study at half a megahertz. Ultrasound Med. Biol.39, 1420–1428 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDannold, N., Zhang, Y. & Vykhodtseva, N. Nonthermal ablation in the rat brain using focused ultrasound and an ultrasound contrast agent: Long-term effects. J. Neurosurg.125, 1539–1548 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDannold, N. J., Vykhodtseva, N. I. & Hynynen, K. Microbubble contrast agent with focused ultrasound to create brain lesions at low power levels: MR imaging and histologic study in rabbits. Radiology241, 95–106 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamimi, A. F. & Juweid, M. Chapter 8—Epidemiology and Outcome of Glioblastoma. Glioblastoma; De Vleeschouwer, S. Preprint at (2017). [PubMed]

- 44.Mosteiro, A. et al. The vascular microenvironment in glioblastoma: a comprehensive review. Biomedicines10, 1285 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuypers, A., Truong, A.-C.K., Becker, L. M., Saavedra-García, P. & Carmeliet, P. Tumor vessel co-option: The past & the future. Front Oncol.12, 965277 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, Y., Wang, S. & Dudley, A. C. Models and molecular mechanisms of blood vessel co-option by cancer cells. Angiogenesis23, 17–25 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidson, C. L., Das, J. M. & Mesfin, F. B. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors. In StatPearls [Internet] (StatPearls Publishing, 2024). [PubMed]

- 48.Chamberlain, M. C. & Tredway, T. L. Adult primary intradural spinal cord tumors: A review. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep.11, 320–328 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tobin, M. K., Geraghty, J. R., Engelhard, H. H., Linninger, A. A. & Mehta, A. I. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: A review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg. Focus39, E14 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rauschenbach, L. Spinal cord tumor microenvironment. In Tumor Microenvironments in Organs: From the Brain to the Skin–Part A 97–109 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Peng, C. et al. Intracranial non-thermal ablation mediated by transcranial focused ultrasound and phase-shift nanoemulsions. Ultrasound Med. Biol.45, 2104–2117 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vykhodtseva, N., McDannold, N. & Hynynen, K. Induction of apoptosis in vivo in the rabbit brain with focused ultrasound and Optison®. Ultrasound Med. Biol.32, 1923–1929 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fletcher, S.-M.P. et al. A study combining microbubble-mediated focused ultrasound and radiation therapy in the healthy rat brain and a F98 glioma model. Sci. Rep.14, 4831 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu, R. & O’Reilly, M. A. Simulating transvertebral ultrasound propagation with a multi-layered ray acoustics model. Phys. Med. Biol.63, 145017 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Latacz, E. et al. Pathological features of vessel co-option versus sprouting angiogenesis. Angiogenesis23, 43–54 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haas, G., Fan, S., Ghadimi, M., De Oliveira, T. & Conradi, L.-C. Different forms of tumor vascularization and their clinical implications focusing on vessel co-option in colorectal cancer liver metastases. Front Cell Dev. Biol.9, 612774 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watkins, S. et al. Disruption of astrocyte–vascular coupling and the blood–brain barrier by invading glioma cells. Nat. Commun.5, 4196 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ribatti, D. & Pezzella, F. Vascular co-option and other alternative modalities of growth of tumor vasculature in glioblastoma. Front. Oncol.12, 874554 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qian, C.-N., Tan, M.-H., Yang, J.-P. & Cao, Y. Revisiting tumor angiogenesis: vessel co-option, vessel remodeling, and cancer cell-derived vasculature formation. Chin. J. Cancer35, 1–6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siemann, D. W., Chaplin, D. J. & Horsman, M. R. Realizing the potential of vascular targeted therapy: The rationale for combining vascular disrupting agents and anti-angiogenic agents to treat cancer. Cancer Invest.35, 519–534 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrera-Aguado, I. et al. The inhibition of vessel co-option as an emerging strategy for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 921 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez, P., Bottenus, N. & Borden, M. Cavitation characterization of size-isolated microbubbles in a vessel phantom using focused ultrasound. Pharmaceutics14, 1925 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Navarro-Becerra, J. A., Song, K.-H., Martinez, P. & Borden, M. A. Microbubble size and dose effects on pharmacokinetics. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.8, 1686–1695 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doblas, S. et al. Glioma morphology and tumor-induced vascular alterations revealed in seven rodent glioma models by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and angiography. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging32, 267–275 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seitz, R. J., Deckert, M. & Wechsler, W. Vascularization of syngenic intracerebral RG2 and F98 rat transplantation tumors: A histochemical and morphometric study by use of ricinus communis agglutinin I. Acta Neuropathol.76, 599–605 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Porter, T. M. et al. Acoustic droplet vaporization for nonthermal ablation of brain tumors. J Acoust Soc Am152, A153–A153 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Cerebral Blood Flow Metab.40, 1769–1777 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johanssen, V. A. et al. Targeted opening of the blood–brain barrier using VCAM-1 functionalised microbubbles and “whole brain” ultrasound. Theranostics14, 4076 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Caplan, J. et al. A novel model of intramedullary spinal cord tumors in rats: functional progression and histopathological characterization. Neurosurgery59, 193–200 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Basso, D. M., Beattie, M. S. & Bresnahan, J. C. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J. Neurotrauma12, 1–21 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Reilly, M. A. et al. Preliminary investigation of focused ultrasound-facilitated drug delivery for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastases. Sci. Rep.8, 9013 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arzt, M. et al. LABKIT: Labeling and segmentation toolkit for big image data. Front Comput. Sci.4, 777728 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep.7, 1–7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.