Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, is frequently associated with musculoskeletal complications, including sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which substantially impair patient quality of life. Despite these clinical observations, the molecular mechanisms linking AD to bone loss remain insufficiently explored. In this study, we examined the femoral bone microarchitecture and transcriptomic profiles of APP/PS1 transgenic mouse models of AD to elucidate the disease’s impact on bone pathology and identify potential gene candidates associated with bone deterioration. We performed micro-computed tomography (microCT) and RNA transcriptome analysis on the femoral bone of these mice. We observed a significant reduction in bone microstructure in both male and female APP/PS1 mice compared to their wild-type counterparts. Transcriptomic analysis of femoral bone tissue revealed substantial differential gene expression between AD mice and controls. Specifically, APP/PS1 mice exhibited differential expression in 289 protein-coding genes across both sexes. Notably, in female APP/PS1 mice, 664 genes were differentially expressed, with key genes such as Shh, Efemp1, Arg1, EphA2, Irx1, and PORCN potentially implicated in bone loss. In male APP/PS1 mice, 787 genes were differentially expressed, with Sel1l, Ffar4, Hspa1a, AMH, WFS1, and CLIC1 emerging as notable candidates in the context of bone deterioration. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis further revealed distinct sex-specific gene pathways between male and female APP/PS1 mice, underscoring the differential molecular underpinnings of bone pathology in AD. This study identifies novel sex-specific genes in the APP/PS1 mouse model and proposes potential therapeutic targets to mitigate bone loss in AD patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-025-01535-7.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, APP/PS1 mice, Bone loss

Introduction

The aging process is an inevitable and irreversible phenomenon characterized by progressive loss of physiological function that impacts overall health [1]. Although the delineation of old age varies, the World Health Organization (WHO) designates individuals aged 60 years and above as constituting this demographic, a cohort witnessing rapid growth [1, 2]. Aging population is on the rise due to the adoption of healthier lifestyles and advancements in medical interventions, culminating in an increased life expectancy. By 2050, the WHO expects the global population to have more individuals over 60 (2.1 billion) than adolescents between 10 and 24 (2.0 billion) [2, 3]. Given these demographic shifts, unraveling the complexities of diseases associated with aging will guide future research to delay pathological changes and promote healthy aging.

Cancer, musculoskeletal frailty, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are among the top causes of pathologic aging [4]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder prevalent in the geriatric demographic and is the leading cause of dementia [4]. As AD progresses, patients present with impaired language, declining problem-solving skills, and behavioral changes [5, 6]. These functional impairments hinder individuals from performing daily normal activities and ultimately result in death 8.5 years after onset [7]. In 2020, 5.8 million Americans were living with AD, and as life expectancy increases, the prevalence will grow to 13.8 million Americans in 2050. Furthermore, AD is prevalent worldwide, as 152 million individuals will have this disease in 2050 [8]. The main pathogenesis behind AD involves beta-amyloid (A plaque deposition throughout the brain, neurofibrillary tangle formation, and persistent neuroinflammation [6]. There are also features of AD pathogenesis that are seen in other aging-related diseases, such as cellular senescence, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [4]. Therefore, it is not surprising that AD progression is associated with various comorbidities. In addition to cardiovascular disease and cancer, AD patients suffer from increased rates of osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and femoral neck fractures [4, 9, 10].

Osteoporosis is a medical condition characterized by the weakening of bones, making them fragile and more susceptible to fractures [11]. These fractures contribute to increased morbidity and mortality in the aging population [12]. Globally, osteoporosis affects hundreds of millions of people, with estimates suggesting that over 200 million individuals are impacted by the condition. It is a significant public health concern, particularly among older adults with AD [13]. While prevention methods and therapeutic drugs for osteoporosis have been established, few studies focus on the molecular mechanism driving bone loss.

AD and bone loss are interconnected through several mechanistic pathways that influence each other [14, 15]. Chronic systemic inflammation, a hallmark of AD, can exacerbate bone loss. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in AD contribute to increased osteoclastogenesis and subsequent bone resorption [16]. Furthermore, AD is associated with heightened oxidative stress, which adversely affects bone homeostasis by promoting osteoclast activity and inhibiting osteoblast function [17]. Additionally, physical inactivity, frequently observed in AD due to cognitive and motor impairments, leads to muscle atrophy (sarcopenia) and reduced mechanical loading on bones, further accelerating bone resorption [18]. Furthermore, studies have proposed that bone loss in AD is linked to disruptions in AKT kinase signaling [19], vitamin D deficiency [13], and insufficient Wnt- catenin signaling [14]. In this study, we aim to understand the molecular mechanisms contributing to bone loss in Alzheimer’s disease by analyzing the bone RNA transcriptome of APP/PS1 female and male mice. Given the different rates of bone loss between males and females, we predict gene expression to vary between the two sexes. Therefore, these data will highlight sex-specific genes contributing to increased bone loss in AD mice. Our unique approach of characterizing differential gene expression in AD bone could help establish therapeutic gene targets to combat a common comorbidity in Alzheimer’s patients.

Methods

Animal handling: The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Augusta University approved all the animal protocols. To accurately depict AD, the APP/PS1 mouse model was selected, as they are double transgenic mice expressing a chimeric mouse/human amyloid precursor protein (Mo/HuAPP695swe) and a mutant human presenilin 1 (PS1-dE9). Male and female wild-type mice (WT mice, male n = 7, female n = 4) (C57BL6) and APP/PS1 mice (APP/PS1, male n = 7, female n = 5) (MMRRC Strain #034832-JAX) were obtained at 23–24 months and housed in a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water throughout the study. The mice were sacrificed to collect femurs, and all the soft tissue was removed from the samples. The femur samples were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for micro-CT.

Micro-computed tomography analysis (µCT): To measure mineral density and morphometric parameters, femurs were scanned in a Bruker SkyScan 1272 X-Ray microtomograph (Bruker MicroCT, Kontich, Belgium) as previously described [20, 21]. Prior to scanning, each femur was fixed in 10% formalin, firmly wrapped in polyester gauze, then packed into 0.65-mL microcentrifuge tubes filled with 70% ethanol. During acquisition, specimens were positioned in parallel with the vertical axis of the scanner. Projection images were acquired using an image pixel size of 8.8 µm2 at a camera resolution of 1224 × 820 pixels. The X-ray source was set to a voltage of 60 kVp at 166 µA. A 0.25-mm aluminum filter was used for beam hardening correction. Each specimen was rotated 180° in 0.5° steps, with four averaged frames acquired per step. A random movement setting of 10 was applied. Three hundred eighty-six projections per specimen were reconstructed into cross-sectional images using Bruker’s NRecon software (ver. 1.7.4.6). A software beam hardening correction of 50% and a ring artifact reduction of 3 were applied across all specimens. Reconstructions were loaded into Bruker’s CT-Analyzer (CTan) program (ver. 1.20.3) for 2D and 3D morphometry. Using CTan, we isolated two representative volumes-of-interest (VOI) in each femur for separate analyses of trabecular and cortical bone. The trabecular VOI was selected based on the length of the femur and used the distal growth plate as a reference point, while the cortical VOI was established at the midpoint of the femur. Each VOI was composed of 51 z-planes of 8.8 µm thickness, comprising a total of 448.8 µm length of bone. Contouring for both trabecular and cortical regions-of-interest was done using an automated process. A global threshold was used for segmentation.

Isolation of RNA and sequencing: Total RNA was isolated from the femurs of the sacrificed mice. Initially, the bone was broken in 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube and washed thoroughly three times with PBS to collect clean bone chips. The bone chips were then crushed into powder form with a mortar and pestle using liquid nitrogen. Finally, QIAzol reagent (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) was then added to the powdered bone samples, and RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Cat. No./ID: 74,004, Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions from the bone. RNA purity and concentration were measured with NanoPhotometer Pearl (IMPLEN, CA, USA) after extraction. The RNA library and transcriptome sequencing were carried out by Novogene Co., Ltd. (Sacramento, CA). Illumina sequencing was carried out at Novogene Co., Ltd. (Sacramento, CA).

Sequencing data analysis: Forty paired-end raw RNA-seq datasets (wildtype and APP/PS1, provided by Novogene in FASTQ format) were transferred to the Partek® Flow® server (Partek Inc., 2020) via SFTP, resulting in 20 paired RNA-seq samples. Sequencing reads were trimmed from the 3′ end if the quality score was below 20 or the minimum read length was less than 5. The trimmed reads were aligned to the mm39 reference genome using the STAR aligner. Subsequently, the aligned reads were quantified against the mm39 Ensembl annotation model (release 104) using the Partek E/M algorithm. Gene counts were normalized by applying an offset, counts per million (CPM), and log base 2 transformation, yielding 26,376 genes. The normalized gene counts were then subjected to a 2 × 2 ANOVA analysis, with AD and gender as the two factors, including interaction effects. A p-value of 0.05 and absolute fold change of 1 were the established cutoff values when analyzing potential genes involved in bone loss.

Results

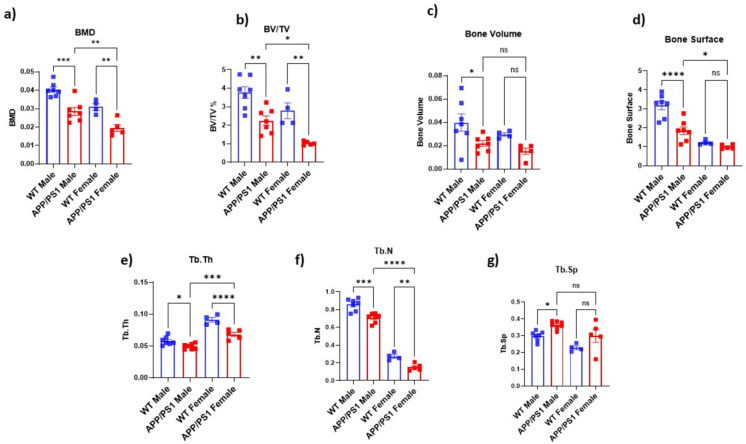

APP/PS1 AD mice have increased bone loss compared to wild-type mice: To assess bone quality and bone mineral density, micro-CT analysis was performed on WT and APP/PS1 mice (n = 4–8). We observed a decrease in bone microstructure in AD mice in both males and females. Specifically, bone mineral density was significantly reduced in both male (p = 0006) and female APP/PS1 mice (p = 0.0033) (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, trabecular bone volume relative to tissue volume (BV/TV) was significantly decreased in APP/PS1 mice in males (p = 0.028) and females (p = 0.0025) (Fig. 1b). In males, a significant reduction in bone surface (p = 0.0010) (Fig. 1d), trabecular number (p = 0.0006) (Fig. 1f), bone volume (p = 0.0406) (Fig. 1c), and trabecular thickness (p = 0.0119) (Fig. 1e) was also noted when compared to WT mice. We also found a significant increase in trabecular separation (p = 0.0007) (Fig. 1g) in APP/PS1 male mice. A similar trend was observed in female APP/PS1 mice across all the parameters. We found a significant decrease in bone volume (p = 0.0036) (Fig. 1c), bone surface (p = 0.0263) (Fig. 1d), trabecular thickness (p = 0.0024) (Fig. 1e), and trabecular number (p = 0.0026) (Fig. 1f) as compared to WT mice. Trabecular separation was augmented in female APP/PS1 mice (p = 0.1567) (Fig. 1g), although no significant change was observed (Table S1). These results align with previous studies that reported decreased bone microstructure in AD patients (clinical studies) and various AD mouse models. For instance, studies in human populations have demonstrated that AD is associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures [13–15, 22, 23]. Similarly, several AD mouse models have significantly increased bone loss [24–26].

Fig. 1.

Effects of Alzheimer’s disease on the bone structural quality of male (upper panel) and female (lower panel) femurs measured by micro-computed tomography. a Bone mineral density (BMD), b bone volume to total volume (BV/TV), c bone volume, d bone surface, e trabecular thickness (Tb. Th), f trabecular number (Tb.N), g trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) in males and h BMD, i BV/TV, j bone volume, k bone surface, l Tb. Th, m Tb.N, n Tb.Sp in females. Black circles (WT mice, male n = 7, female n = 4) and red squares (APP/PS1, male n = 7, female n = 5) represent the number of mice for each sex. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test for two groups (*p < 0.04, **p < 0.01)

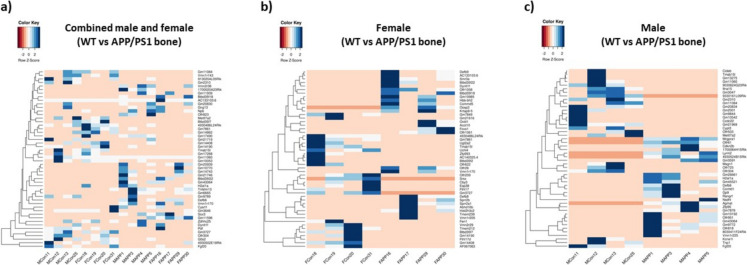

Bone transcriptome is altered in mice with Alzheimer’s disease: Comparison of the femur transcriptome (combined male and female) between wild-type controls and APP/PS1 mice revealed significant differences in gene expression (Fig. 2a). A total of 289 differentially expressed protein-coding genes were identified, meeting the criterion of a p-value < 0.05 and exhibiting an absolute fold change of at least 1. Among these genes, 162 were upregulated, while 127 were downregulated. Notably, the most downregulated genes, including Gm3727, G0s2, and Slfn8, displayed fold changes of − 1.5 or lower. Conversely, the most upregulated genes, such as Gtf2h5, H2-M11, and Cabp2, exhibited fold changes exceeding 1.65. There are also several genes that met the cutoff parameters and could be linked to the development of bone loss in AD. Although the majority of differentially expressed genes lack established roles in AD-associated bone loss, prior studies have highlighted the significance of some of these genes in musculoskeletal function (Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Heat maps show differential gene expression in femurs of a wild-type (WT) vs APP/PS1 mice (n = 8 for both groups), b wild-type vs APP/PS1 female mice (n = 4 for both groups), and c wild-type vs APP/PS1 male mice (n = 4 for both groups). Shades of blue indicate positive z-scores, while orange depicts negative z-scores

Sex-specific alterations in bone transcriptome in Alzheimer’s disease: Comparison of bone transcriptomes between wild-type and APP/PS1 female mice revealed distinct differences in gene expression patterns (Fig. 2b). Using the criteria mentioned above, 664 protein-coding genes were identified as differentially expressed. Among the 322 upregulated genes, Tbc1d21, Ccr1l1, and Hist2h3c2 exhibited the highest expressions, demonstrating fold changes exceeding 2.3. Conversely, 342 downregulated genes were observed, with Gm3727, Trmt112, and Slfn8 displaying the lowest expressions, each with at least a 2.4-fold decrease. Notably, the androgen receptor (Ar) is a downregulated gene involved in hormone signaling that has been previously implicated in bone growth (Table S3) [27]. Aside from Ar, there were many novel genes with absolute fold changes greater than 1 that could contribute to bone loss in AD mice.

There were also differences in the bone transcriptome of APP/PS1 males, and the alterations in gene expression did not align with the femur transcriptome of female APP/PS1 mice (Fig. 2c). In the male APP/PS1 bone transcriptome, 787 protein-coding genes were differentially expressed with a p-value < 0.05 and an absolute fold change greater than 1. Of the 787 protein-coding genes, 465 were upregulated with Mrgpra1, Gtf2h5, and Ccdc87 showing fold changes of at least 2.8. Mgp was among the upregulated genes with a known function in osteoclast differentiation and osteoblast inhibition (Table S4) [28]. There were 322 downregulated genes, and Gm47283, Gm5127, and Gm21969 showed at least a 2.6-fold decrease in expression. Adipoq and Cyp19a1 were downregulated genes with known roles in osteoblast differentiation and bone mineral density regulation, respectively (Table S4) [29, 30]. In addition to these previously identified genes, there were novel, differentially expressed genes that could be involved in the onset of bone loss in APP/PS1 males (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differentially expressed novel genes in bones of (a) combined male and female APP/PS1 mice (b) female APP/PS1 mice, and (c) male APP/PS1 mice

| Gene | Fold change | Function |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Combined male and female APP/PS1 mice | ||

| Efnb1 | 0.3923 | Skeleton development signaling |

| Eif2a | 0.4175 | Translation initiation factor |

| NPY | 0.4263 | Neuropeptide involved in metabolism |

| Bag2 | 2.2346 | Chaperone protein regulation |

| IL-4 | 2.2501 | Immunoregulatory cytokine |

| Slc17a2 | 2.5140 | Transmembrane anion transporter |

| (b) Female APP/PS1 mice | ||

| Shh | 0.2606 | Hedgehog and Wnt signaling |

| Efemp1 | 0.2872 | Extracellular matrix protein |

| Arg1 | 0.3209 | Enzyme in urea cycle |

| EphA2 | 3.0525 | Membrane-bound protein in cell–cell communication |

| Irx1 | 3.4105 | Transcription factor in NF-κβ signaling |

| PORCN | 3.5554 | Cell signaling through Wnt pathway |

| (c) Male APP/PS1 mice | ||

| Sel1l | 0.2449 | Misfolded protein degradation |

| Ffar4 | 0.2466 | G-protein coupled receptor for free fatty acid |

| Hspa1a | 0.2483 | Heat shock protein |

| WFS1 | 3.0525 | Intracellular calcium regulation |

| AMH | 3.0951 | Cell signaling via TGF-β pathway |

| CLIC1 | 4.6913 | Chloride channel inhibitor |

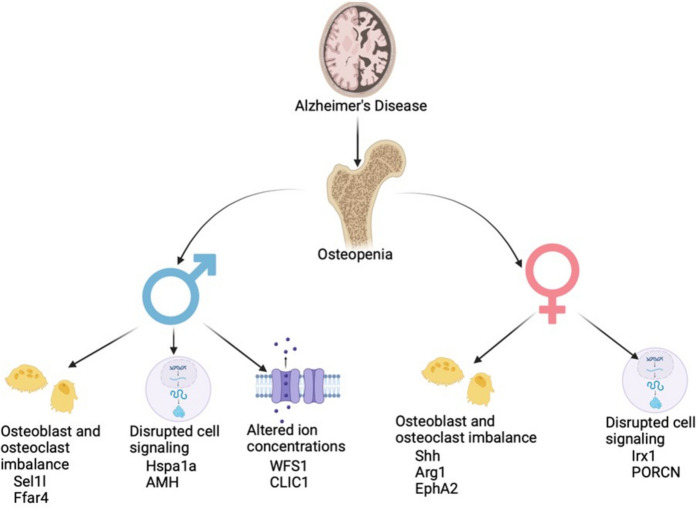

Gene sets are altered in a sex-specific manner according to Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis: GO enrichment analysis revealed that female and male APP/PS1 bone transcriptomes do not share identical gene set enrichments (Fig. 3). In the female APP/PS1 group, 310 gene sets with a p-value < 0.05 were identified, and the most enriched sets included negative regulation of T-cell proliferation, cellular response to interferon-gamma, and ephrin receptor signaling pathway. There were 249 statistically significant enriched gene sets in the male APP/PS1 group, and the most enriched sets were sensory perception of bitter taste, detection of chemical stimulus, and protein exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. In both female and male APP/PS1 groups, many novel genes potentially linked to the onset of osteopenia in AD were included in the statistically significant enriched gene sets (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed enriched gene sets that differed between wild-type and APP/PS1 a female and b male mice. List of novel genes with potential connections to bone loss in AD in c female and d male mice. Highlight gene sets potentially uncovering pathways that are sex specific and may have a role in AD-related pathology

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder primarily associated with aging, characterized by cognitive decline, memory loss, and behavioral changes [4–6]. While AD is primarily known for its profound effects on the central nervous system, it also manifests with a range of comorbidities that impact multiple organ systems, including the musculoskeletal system [31–33]. While previous clinical human [34] and rodent studies [34, 35] have shown bone loss in AD, our study elucidates the distinctive gene expression patterns in the bones of AD APP/PS1 mice and provides insights into potential sex-specific variations.

Upon comparing the femur transcriptome of APP/PS1 mice to wild-type counterparts, 289 genes exhibited differential expression. Novel genes were identified based on their statistical significance, higher absolute fold change, and potential relevance to AD-associated bone loss. Among the differentially expressed genes, downregulated candidates included Efnb1, Eif2a, and Npy, which are known for their involvement in cell signaling, protein synthesis, and metabolism. Conversely, upregulated genes encompassed Bag2, Foxj1, and Slc17a2, known to play roles in these fundamental cellular processes.

The ephrin-B1 (Efnb1) gene belongs to the ephrin family and is involved in the development of the axial and appendicular skeleton through osteoblast and osteoclast regulation [36, 37]. We observed a marked downregulation of Efnb1 expression, a phenomenon previously associated with an osteoporotic phenotype in studies involving Efnb1 knockout mice [37]. This downregulation in Efnb1 expression potentially disrupts the equilibrium between osteoblast and osteoclast activity and, thus, might be involved in APP/PS1 bone loss. Moreover, aberrant expression of Eif2a, a crucial translation initiation factor, has also been implicated in perturbing the balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Notably, Li et al. reported the involvement of Eif2a in promoting osteoblast activation and suppressing osteoclast activity [38]. Our results support these findings, as diminished Eif2a expression in our study correlates with increased bone loss. Additionally, our study revealed alterations in the expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY), a neuropeptide traditionally recognized for its role in hunger stimulation [39]. Recent studies have highlighted its regulatory influence on bone homeostasis. Decreased NPY levels suppressed osteoblasts via reduced osteoprotegerin, and osteoclastogenesis becomes more prominent with increased RANKL expression [28, 29]. In our study, dysregulation of these genes (NPY, Eif2a, and Efnb1) could be involved in bone homeostasis imbalance leading to AD bone loss.

IL4, Slc17a2, and Bag2 were among the upregulated genes in the APP/PS1 bone transcriptome. IL-4, recognized as a cytokine pivotal in modulating antibody production and inflammation, has been previously associated with bone osteolysis and fragility in murine models. Consequently, the heightened IL-4 levels observed in the APP/PS1 mice could contribute to the onset of bone loss [40, 41]. Furthermore, increased levels of Slc17a2, a transmembrane anion transporter, were observed in the bones of APP/PS1 mice. While there are conflicting reports regarding Slc17a2 and osteoclast development, a study by Gupta et al. elucidated its significance in osteoclast survival [42]. Knockout Slc17a2 mice demonstrated increased bone formation, so it is possible that enhanced Slc17a2 activity could contribute to osteopenia [42]. Lastly, Bag2, known for its involvement in signaling protein degradation and apoptosis through interaction with heat shock proteins, presents an intriguing prospect in bone biology, although its precise role remains undetermined [28, 43]. Previous studies have shown an association between increased Bag2 expression and decreased BMD in post-menopausal females [44], and Wang et al. suggest Bag2 alters the natural homeostasis between osteoblasts and osteoclasts [43]. Together, these studies suggest that upregulated Bag2, Foxj1, and Slc17a2 expression in APP/PS1 bone could lead to bone loss.

While global analysis of bone transcriptome in APP/PS1 mice offers a comprehensive overview of the molecular alterations associated with AD, a more targeted sex-specific analysis can present greater potential for identifying specific therapeutic targets. Our analysis in female APP/PS1 mice showed Shh, Efemp1, and Arg1 genes were downregulated, while EphA2, Irx1, and PORCN were upregulated. Sonic hedgehog (Shh), known for its role in embryonic limb bud development, has garnered attention for its involvement in bone formation and fracture healing [45, 46]. Decreased Shh expression, as observed in female APP/PS1 mice, likely compromises osteoblastic bone formation, consequently promoting heightened bone resorption. Moreover, Koga et al. demonstrated a positive correlation between estrogen levels and Shh activity. In aging females, estrogen levels decrease, which could influence the reduced Shh levels seen in APP/PS1 female mice [47]. Similarly, decreased BMD was demonstrated in knockout Efemp1 mice [48]. Efemp1 is an extracellular matrix protein ubiquitously expressed in tissue, and dysregulated levels are implicated in bone degeneration. While the pathophysiological mechanisms linking downregulated Efemp1 to bone loss remain elusive, altered expression of Efemp1 has been shown in osteoarthritis and osteosarcoma [48, 49]. Conversely, Arg1, an enzyme integral to the urea cycle, exhibits an association with bone loss and estrogen activity [50, 51]. The decreased expression of Arg1, Efemp1, and Shh in female APP/PS1 mice might be involved in bone loss in AD.

The novel, upregulated genes in female APP/PS1 mice (EphA2, Irx1, and PORCN) primarily function in cell signaling and communication. Irie et al. demonstrated that EphA2 is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase located on osteoclast and osteoblast surfaces and assists in bone remodeling. Increased expression of EphA2 in APP/PS1 mice might lead to enhanced osteoclastogenesis and suppressed osteoblast development, contributing to bone loss [52]. Furthermore, studies have identified a connection between EphA2 and estrogen [53, 54]. In aged females, decreased estrogen inversely regulates EphA2 levels and could contribute to sex-specific bone loss in females. EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase has been linked to the regulation of bone homeostasis, through its interactions with ephrin ligands and signaling pathways that influence the activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts responsible for bone resorption and bone formation, respectively.

Like EphA2, Irx1, a transcription factor that mediates osteoclastogenesis, is upregulated in APP/PS1 mice bones in our study. Increased Irx1 expression promotes NF-κβ synthesis, a central signaling pathway involved in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis [55, 56]. PORCN is an endoplasmic reticulum protein involved in bone remodeling by inhibiting the Wnt pathway [57]. In wild-type mice, Wnt induces osteoblast differentiation and suppresses osteoclast maturation, leading to bone formation [14, 58]; however, increased PORCN expression in APP/PS1 mice might block Wnt signaling and induce bone loss. These data support previous findings that dysregulated NF-κβ and Wnt signaling could play a role in bone loss in APP/PS1 mice. Bone loss in aged female is primarily driven by the decreased levels of hormones, particularly estrogen (during menopause), which accelerates bone resorption and decreases bone microstructure. This age-related bone loss can lead to osteoporosis and increased fracture risk. Interestingly, this decline level of estrogen and bone loss is also linked to AD pathology. The interaction between bone loss and AD is complex, with systemic inflammation and metabolic disturbances acting as key factors in both conditions, suggesting that age-induced bone loss may exacerbate cognitive decline in females.

In male bone transcriptome analysis, we identified several novel genes potentially linked to bone loss in APP/PS1 mice. Notably, Sel1l, Ffar4, and Hspa1a were downregulated, while AMH, WFS1, and CLIC1 were upregulated. Sel1l, known for facilitating protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum, has been previously implicated in modulating RANKL expression [59]. Decreased Sel1l expression has been linked to elevated RANKL levels, indicative of heightened osteoclast activity and bone resorption [60]. Hence, reduced Sel1l expression in male APP/PS1 mice may contribute to an osteopenic phenotype through augmented osteoclast activity. Similarly, downregulation of Ffar4 may impact bone loss by suppressing osteoblast activity. While Ffar4 primarily functions as a free fatty acid receptor, normal Ffar4 levels are pivotal in regulating osteoblast and osteoclast activity [61]. Consistent with observations in Ffar4 knockout mice, decreased Ffar4 expression in male APP/PS1 mice could lead to diminished bone mass. Likewise, Hspa1a, involved in various metabolic processes, modulates osteoblast function via the Wnt signaling pathway. Enhanced fracture healing facilitated by Hspa1a overexpression demonstrates its significance in promoting osteogenesis [62]. Conversely, under expression of Hspa1a, as observed in male APP/PS1 mice, may predispose to bone loss. The above dysregulated genes might be involved in the male bone pathology of APP/PS1 mice.

WFS1, AMH, and CLIC1 were upregulated genes in APP/PS1 male mice. WFS1, a gene responsible for Wolfram syndrome, regulates intracellular calcium levels in various tissues, including bone [63]. Dysregulation of calcium homeostasis is intricately linked to aberrant bone formation, heightening susceptibility to fractures and low BMD. Elevated WFS1 expression in male APP/PS1 mice likely disrupts intracellular calcium balance within bone, potentially contributing to the onset of bone loss. AMH, otherwise known as anti-Müllerian hormone, regulates male gonadal development through TGF-β signaling and is negatively regulated by testosterone. During aging, testosterone levels in men decline, which reduces AMH transcription inhibition [64]. A recent study also identified its role in NF-κβ-mediated osteoclast differentiation [65]. Increased AMH expression in APP/PS1 mice indicates increased osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, thereby fostering bone pathology. Furthermore, CLIC1, an intracellular chloride channel prominently expressed in osteoclasts, exhibited upregulation in male APP/PS1 mice. While the precise mechanism remains elusive, the literature suggests a pivotal role for CLIC1 in modulating osteoclast function. Schaller et al. demonstrated that inhibition of CLIC1 attenuated bone resorption and mitigated the onset of osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats [66], underscoring its significance in bone homeostasis.

In addition to the identification of novel genes potentially implicated in AD-associated bone loss, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed the involvement of sex-specific changes (Fig. 3). The observed changes in our study likely stem from the complex interplay between hormonal alteration with age and during the progression of the disease. Sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone are crucial in maintaining bone health [62] and cognitive function [63, 64]. Further studies employing gain- and loss-of-function approaches are needed to unravel the direct relationship between the sex-specific changes observed in our study. These strategies can provide insights into how specific genes, proteins, or signaling pathways influenced by hormonal changes contribute to bone health in AD.

This study delineates the manifestation of bone loss in male and female AD mice and identifies sex-dependent genetic determinants that govern pathological alterations in bone (Fig. 4). However, our study has certain limitations. Firstly, our analysis was restricted to RNA expression levels, omitting a direct assessment of protein expression and function within the bone tissue. This limitation poses a challenge in correlating changes in gene expression with actual protein function and activity, which are critical for understanding the full impact of these genes on bone health. Secondly, the complexity of AD, coupled with multiple comorbidities that exacerbate bone health deterioration, was not fully integrated into our bone transcriptome analysis. AD is often accompanied by systemic inflammation, hormonal imbalances, and nutritional deficiencies, all of which can significantly influence bone metabolism. The interplay between these factors and their combined effects on bone loss was not accounted for in this study, potentially limiting the comprehensiveness of our findings. Despite these limitations, our findings significantly contribute to understanding the genetic mechanisms behind AD-associated bone loss. Identifying new genes associated with bone loss offers opportunities for gene-specific therapeutic interventions, potentially restoring gene expressions and slowing bone loss progression in AD.

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram showing sex-specific alteration in signaling pathways in the bone transcriptome of APP/PS1 mice

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 The quantitative data of micro-CT measurement parameters of APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice bone analysis. (DOCX 17 KB)

Supplementary file2 Complete list of differentially expressed genes in bones of combined male and female APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice. (XLSX 33 KB)

Supplementary file3 Complete list of differentially expressed genes in bones of female APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice. (XLSX 66 KB)

Supplementary file4 Complete list of differentially expressed genes in bones of male APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice. (XLSX 79 KB)

Author contribution

Study concept and design: SF; drafting of the manuscript: MG, SF; microCT analysis: RZ, MAC; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation: SV, DMA, JC, RZ, MAC.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: MAC, FD, XYL, CMI, SF.

Funding

This publication is based upon work supported in part by the National Institutes of Health NIA00059 (SF), S10-OD025177, AG036675 (National Institute on Aging-AG036675 S.F, C.I), and R01AG062655 (F.D.) and from the Alzheimer’s Association (SAGA23-1142437 to FD). The abovementioned funding did not lead to any conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no other conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript. F.D declares that he is an Associate Editor of Geroscience.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dziechciaz M, Filip R. Biological psychological and social determinants of old age: bio-psycho-social aspects of human aging. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2014;21(4):835–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahjoob M, Stochaj U. Curcumin nanoformulations to combat aging-related diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;69:101364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudnicka E, et al. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020;139:6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschi C, et al. The continuum of aging and age-related diseases: common mechanisms but different rates. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(1):59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan S, Barve KH, Kumar MS. Recent advancements in pathogenesis, diagnostics and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2020;18(11):1106–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jost BC, Grossberg GT. The natural history of Alzheimer’s disease: a brain bank study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(11):1248–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang XX, et al. The epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease modifiable risk factors and prevention. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(3):313–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heun R, et al. Alzheimer’s disease and co-morbidity: increased prevalence and possible risk factors of excess mortality in a naturalistic 7-year follow-up. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert CC, et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: are they sicker? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salari N, et al. Global prevalence of osteoporosis among the world older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karaguzel G, Holick MF. Diagnosis and treatment of osteopenia. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11(4):237–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YH, Lo RY. Alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;29(3):138–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dengler-Crish CM, Elefteriou F. Shared mechanisms: osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease? Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(5):1317–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharpure M, et al. Alterations in Alzheimer’s disease microglia transcriptome might be involved in bone pathophysiology. Neurobiol Dis. 2024;191:106404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitaura H, Marahleh A, Ohori F, Noguchi T, Nara Y, Pramusita A, Kinjo R, Ma J, Kanou K, Mizoguchi I. Role of the interaction of tumor necrosis factor-α and tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 in bone-related cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1481. 10.3390/ijms23031481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Iantomasi T, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoporosis: molecular mechanisms involved and the relationship with microRNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Larsson L, et al. Sarcopenia: aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):427–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehsel K, Christl J. Comorbidity of osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease: is; AKT; -ing on cellular glucose uptake the missing link? Ageing Res Rev. 2022;76:101592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sangani R, et al. Regulation of vitamin C transporter in the type 1 diabetic mouse bone and bone marrow. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013;95(3):298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vyavahare S, et al. Inhibiting microRNA-141-3p improves musculoskeletal health in aged mice. Aging Dis. 2023;14(6):2303–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang JH, et al. Medical comorbidity in Alzheimer’s disease: a nested case-control study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(2):773–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang HG, et al. Bone mineral loss and cognitive impairment: the PRESENT project. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(41):e12755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, et al. Attenuation of Alzheimer’s brain pathology in 5XFAD mice by PTH(1–34), a peptide of parathyroid hormone. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ll JE, et al. Degradation of bone quality in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2022;37(12):2548–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alkhouli MF, et al. Exercise and resveratrol increase fracture resistance in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen JF, et al. Androgens and androgen receptor actions on bone health and disease: from androgen deficiency to androgen therapy. Cells. 2019;8(11):1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, et al. Unexpected role of matrix Gla protein in osteoclasts: inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gao H, et al. Bone marrow adipoq(+) cell population controls bone mass via sclerostin in mice. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Napoli N, et al. Genetic polymorphism at Val80 (rs700518) of the CYP19A1 gene is associated with aromatase inhibitor associated bone loss in women with ER + breast cancer. Bone. 2013;55(2):309–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Fracture risk in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(6):614–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou BN, Zhang Q, Li M. Alzheimer’s disease and its associated risk of bone fractures: a narrative review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1190762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luckhaus C, et al. Blood biomarkers of osteoporosis in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2009;116(7):905–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodman I. Osteoporosis: linking osteoporosis with Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(11):638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia WF, et al. Swedish mutant APP suppresses osteoblast differentiation and causes osteoporotic deficit, which are ameliorated by N-acetyl-L-cysteine. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(10):2122–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davy A, Aubin J, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 forward and reverse signaling are required during mouse development. Genes Dev. 2004;18(5):572–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arthur A, et al. The osteoprogenitor-specific loss of ephrinB1 results in an osteoporotic phenotype affecting the balance between bone formation and resorption. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, et al. eIF2alpha signaling regulates autophagy of osteoblasts and the development of osteoclasts in OVX mice. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(12):921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck B. Neuropeptide Y in normal eating and in genetic and dietary-induced obesity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1471):1159–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis DB, et al. Osteoporosis induced in mice by overproduction of interleukin 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(24):11618–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin Q, et al. IL4/IL4R signaling promotes the osteolysis in metastatic bone of CRC through regulating the proliferation of osteoclast precursors. Mol Med. 2021;27(1):152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta A, et al. Identification of the type II Na(+)-Pi cotransporter (Npt2) in the osteoclast and the skeletal phenotype of Npt2-/- mice. Bone. 2001;29(5):467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, et al. Mining potential drug targets for osteoporosis based on CeRNA network. Orthop Surg. 2023;15(5):1333–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao P, et al. In vivo genome-wide expression study on human circulating B cells suggests a novel ESR1 and MAPK3 network for postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(5):644–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang J, et al. The hedgehog signalling pathway in bone formation. Int J Oral Sci. 2015;7(2):73–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuwahara ST, et al. On the horizon: hedgehog signaling to heal broken bones. Bone Res. 2022;10(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koga K, et al. Novel link between estrogen receptor alpha and hedgehog pathway in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(2A):731–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLaughlin PJ, et al. Lack of fibulin-3 causes early aging and herniation, but not macular degeneration in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(24):3059–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z, et al. EFEMP1 as a potential biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of osteosarcoma. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:5264265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeon JT, Choi SW, Kim SH. Arginase 1 is a negative regulator of osteoclast differentiation. Amino Acids. 2016;48(2):559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klawitter J, et al. A relative L-arginine deficiency contributes to endothelial dysfunction across the stages of the menopausal transition. Physiol Rep. 2017;5(17):e13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irie N, et al. Bidirectional signaling through ephrinA2-EphA2 enhances osteoclastogenesis and suppresses osteoblastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(21):14637–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiao T, et al. Targeting EphA2 in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zelinski DP, et al. Estrogen and Myc negatively regulate expression of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85(4):714–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abu-Amer Y. NF-kappaB signaling and bone resorption. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(9):2377–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu J, et al. IRX1 hypomethylation promotes osteosarcoma metastasis via induction of CXCL14/NF-kappaB signaling. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):1839–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madan B, et al. Bone loss from Wnt inhibition mitigated by concurrent alendronate therapy. Bone Res. 2018;6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canalis E. Wnt signalling in osteoporosis: mechanisms and novel therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(10):575–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iyer S, et al. Elevation of the unfolded protein response increases RANKL expression. FASEB Bioadv. 2020;2(4):207–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim HN, et al. Osteocyte RANKL is required for cortical bone loss with age and is induced by senescence. JCI Insight. 2020;5(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Ahn SH, et al. Free fatty acid receptor 4 (GPR120) stimulates bone formation and suppresses bone resorption in the presence of elevated n-3 fatty acid levels. Endocrinology. 2016;157(7):2621–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang W, et al. Overexpression of HSPA1A enhances the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Catalano A, et al. Multiple fractures and impaired bone metabolism in Wolfram syndrome: a case report. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2017;14(2):254–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu HY, et al. Regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) in males and the associations of serum AMH with the disorders of male fertility. Asian J Androl. 2019;21(2):109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim JH, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone negatively regulates osteoclast differentiation by suppressing the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand pathway. J Bone Metab. 2021;28(3):223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaller S, et al. The chloride channel inhibitor NS3736 [corrected] prevents bone resorption in ovariectomized rats without changing bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(7):1144–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 The quantitative data of micro-CT measurement parameters of APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice bone analysis. (DOCX 17 KB)

Supplementary file2 Complete list of differentially expressed genes in bones of combined male and female APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice. (XLSX 33 KB)

Supplementary file3 Complete list of differentially expressed genes in bones of female APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice. (XLSX 66 KB)

Supplementary file4 Complete list of differentially expressed genes in bones of male APP/PS1 mice and wildtype mice. (XLSX 79 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.