Major depressive disorder (MDD) remains a pressing public health concern, especially when onset occurs during adolescence, a period marked by profound changes in neural networks. Improving early diagnostics and treatment for early-onset MDD is particularly important since it is often associated with a more severe disease course. Currently, MDD is diagnosed through clinical evaluation supported by standardized scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. However, diagnosing MDD in adolescents is particularly challenging due to overlapping symptomatology originating from natural developmental changes. Thus, the development of objective biomarkers, particularly blood-based ones, would represent a significant advance in adolescent mental health care.

Peripheral Biomarkers for Psychiatric Disorders

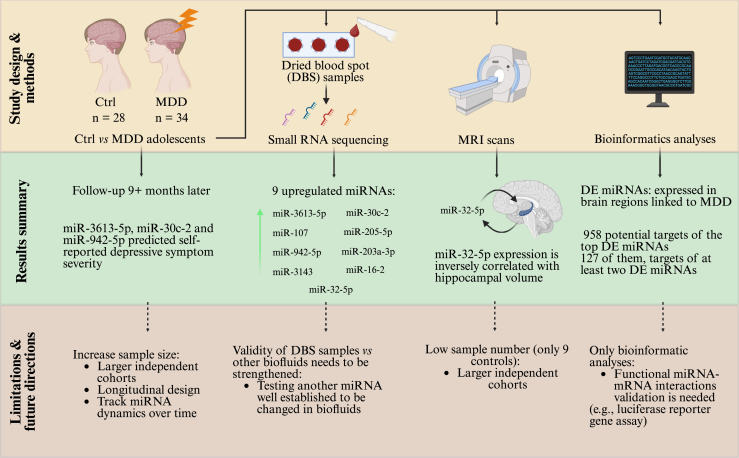

Recent studies have uncovered the functional relevance of microRNAs (miRNAs), small noncoding RNAs involved in messenger RNA (mRNA) expression, as potential players in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. The peripheral expression of miRNAs has been shown to correlate well with their expression in the central nervous system (1), positioning them as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of brain disorders. Adding to this growing field, Morgunova et al. (2) recently published a study in Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science in which they explored whether adolescent patients with MDD display aberrant changes in the expression of peripheral miRNAs and whether this correlates with structural brain changes detected by brain imaging. Using dried blood spot (DBS) samples, Morgunova et al. (2) identified 9 upregulated miRNAs (or their precursor) in adolescents with MDD compared with healthy control participants: miR-3613-5p, miR-30c-2, miR-107, miR-205-5p, miR-942-5p, miR-203a-3p, miR-3143, miR-16-2, and miR-32-5p. Notably, the expression levels of miR-3613-5p, miR-30c-2, and miR-942-5p predicted self-reported depressive symptom severity at a follow-up examination 9+ months later, underscoring their prognostic potential. Intriguingly, some of the identified upregulated miRNAs have previously been implicated in brain function or in neurological or psychiatric conditions. For example, miR-3613-5p was shown to be upregulated in epilepsy (3), miR-30c was shown to be dysregulated in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (4) and Parkinson’s disease (5), and miR-942-5p was upregulated in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (6). Furthermore, a recent study proposed that miR-203a-3p is a key regulator of lifespan in mice (7). Finally, miR-16-2 was shown to target the serotonin transporter and is altered in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum samples of adult patients with MDD and in response to chronic antidepressant treatment (8). These studies reinforce that the findings described in the study by Morgunova et al. (2) are consistent with the literature and could reflect changes in miRNA expression occurring in the brain of adolescents with MDD.

One particularly noteworthy finding in the Morgunova et al. (2) study was the inverse correlation between miR-32-5p levels and the volume of the hippocampus, a brain area consistently implicated in depression. This finding is consistent with prior reports implicating hippocampal atrophy in depression and supports the notion that variations in circulating miRNAs may serve as both biomarkers and biopathogenic effectors.

After identifying the top dysregulated miRNAs in adolescents with MDD, Morgunova et al. (2) followed up with bioinformatics predictions of the potential miRNA targets. Thereby, they identified 127 shared gene targets among the top differentially expressed miRNAs, enriched in neurodevelopmental and cognitive function pathways, providing a systems-level understanding of how peripheral signals may mirror central nervous system dysfunction. For example, the authors describe genes such as EPHA7 and ERBB4, implicated in neuronal maturation and depression, respectively, to be potential targets of the identified miRNAs, reinforcing their biological relevance. As the authors used peripheral miRNA expression patterns to obtain a hint about potential changes in the brain, these bioinformatic analyses could be misleading regarding what is really happening in the neurons. This is one of the critique points to this study—the lack of functional validation of these miRNA targets. While bioinformatics predictions offer valuable hypotheses, experimental confirmation of miRNA-mRNA interactions, ideally in relevant neural cell types or animal models, is required to strengthen causal inferences. For example, these validation experiments could include luciferase reporter gene assays to assess whether a specific miRNA candidate can indeed reduce the expression of its predicted target genes in a neuronal background (e.g., in primary neuronal cultures). Once validated, miRNA-target interactions from the Morgunova et al. (2) study could be used as potential therapeutic targets for MDD in adolescents in future studies.

Methodological Considerations: Dried Blood Spots

While the roles of miRNAs as signaling molecules in cell-to-cell communication are still being characterized, their presence in peripheral fluids makes them suitable for noninvasive biomarker studies. Despite their potential to provide insights into individual vulnerability to MDD in adolescents (9), research on miRNAs as biomarkers in youth remains limited, highlighting the need for longitudinal studies to identify robust, age-specific miRNA signatures that predict or track the course of adolescent depression. miRNAs are thought to be stable in these biofluids, but the specific cell source or method of sample preparation and conservation could affect applications. When studying peripheral biomarkers, several laboratories make use of blood fractions, such as serum or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). In our laboratory, we routinely use PBMCs for this purpose. We recently published a research study in which we used PBMCs from healthy control participants at genetic or environmental increased risk for mood disorders and patients with mood disorders. We identified one specific miRNA, miR-708-5p, to be highly increased in the at-risk participants and particularly in patients with bipolar disorder (10). On the other hand, Morgunova et al. (2) used DBS samples in their study. The utilization of DBS samples offers many advantages compared with serum, plasma, or PBMCs. These include the ease of collection, the required small blood volumes, and the overall stability of the samples at room temperature, which makes transportation and storage easier. Furthermore, this method is cost-effective and practical for large-scale screenings, but an obvious concern is whether all the components in the dried blood are stable over the long term. For example, when analyzing miRNA expression in PBMCs, the samples are kept at −80 °C for several months and remain stable until they are thawed for RNA extraction. The lack of a controlled environment at room temperature in dried samples could cause instability in the tissue, thereby introducing variability in the final analysis. As a first quality control step, Morgunova et al. (2) directly compared miRNA levels obtained from DBS samples with those from conventional biofluids such as serum and plasma. Their initial results are encouraging but require further validations (e.g., testing other miRNA well established to be changed in biofluids in specific conditions), which are crucial for the use of this method in future biomarker research, especially in resource-limited settings.

Limitations and Future Directions

As acknowledged by the authors, one major limitation of the study is the use of a relatively small and demographically homogeneous patient cohort, which precludes drawing general conclusions. This is particularly true for the reported correlations between miRNA levels and neuroimaging phenotypes, where even a lower number of participants was available. Future research should prioritize replication in independent, larger, more diverse cohorts and integrate longitudinal designs to track miRNA dynamics over time and in response to treatment. Furthermore, while the study differentiates between medicated and unmedicated participants, potential pharmacodynamic effects on miRNA expression warrant deeper investigation. Refer to Figure 1 for a summary of the study design, methods, and results, together with its limitations and potential future directions.

Figure 1.

Summary of the study design, methods, and results of the Morgunova et al. (2) study, along with its limitations and potential future directions. Ctrl, control; DE, differentially expressed; MDD, major depressive disorder; miRNA, microRNA; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRNA, messenger RNA; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Conclusions

The Morgunova et al. (2) study marks a meaningful advance in adolescent depression research by illuminating the peripheral miRNA landscape. It supports the conceptual shift toward viewing miRNAs as not only passive biomarkers but also active participants in disease pathophysiology. Although the results should be regarded as preliminary due to the small size of the patient cohort, this research offers compelling evidence that specific circulating miRNAs correlate with clinical symptoms and neuroanatomical measures, thereby setting the stage for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. As the psychiatry field moves toward precision medicine, the integration of miRNA profiling with clinical phenotypes, neuroimaging, and environmental data will be critical. In the future, developing objective miRNA-based biomarkers and establishing miRNA-targeted interventions may help transform the diagnosis and treatment of adolescent MDD, a disorder with long-lasting consequences for affected individuals.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, Switzerland (Grant Nos. 310030_205064 and IZSEZ0_229628 [to BRL and GS]).

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Torres-Berrío A., Nouel D., Cuesta S., Parise E.M., Restrepo-Lozano J.M., Larochelle P., et al. MiR-218: A molecular switch and potential biomarker of susceptibility to stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:951–964. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0421-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgunova A.O.T., O’Toole N., Abboud F., Coury S., Chen G.G., Teixeira M., et al. Peripheral microRNA signatures in adolescent depression. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2025;5 doi: 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2025.100505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan S., Zhang H., Xie W., Meng F., Zhang K., Jiang Y., et al. Altered microRNA profiles in plasma exosomes from mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:4136–4146. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satoh J.I., Kino Y., Niida S. MicroRNA-seq data analysis pipeline to identify blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease from public data. Biomark Insights. 2015;10:21–31. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S25132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallelunga A., Ragusa M., Di Mauro S., Iannitti T., Pilleri M., Biundo R., et al. Identification of circulating microRNAs for the differential diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:156. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nuzziello N., Craig F., Simone M., Consiglio A., Licciulli F., Margari L., et al. Integrated analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression profiles: An attempt to disentangle the complex interaction network in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Brain Sci. 2019;9:288. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9100288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee B.P., Burić I., George-Pandeth A., Flurkey K., Harrison D.E., Yuan R., et al. MicroRNAs miR-203-3p, miR-664-3p and miR-708-5p are associated with median strain lifespan in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep44620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musazzi L., Mingardi J., Ieraci A., Barbon A., Popoli M. Stress, microRNAs, and stress-related psychiatric disorders: An overview. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:4977–4994. doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-02139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgunova A., Teixeira M., Flores C. Perspective on adolescent psychiatric illness and emerging role of microRNAs as biomarkers of risk. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2024;49:E282–E288. doi: 10.1503/jpn.240072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilardi C., Martins H.C., Levone B.R., Bianco A.L., Bicker S., Germain P.L., et al. miR-708-5p is elevated in bipolar patients and can induce mood disorder-associated behavior in mice. EMBO Rep. 2025;26:2121–2145. doi: 10.1038/s44319-025-00410-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]