Abstract

Background

Glucocorticoid (GC) signaling plays a crucial role in immune regulation during critical illness, but cell-specific responses remain poorly understood. While previous studies have predominantly examined glucocorticoid receptor (GCR)-α and GCR-β, the roles of alternative isoforms (GCR-γ, GCR-P) and the downstream effectors GC-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) and dual-specific phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) across different immune cell populations in critical illness remain unexplored.

Methods

In this prospective, observational study, we enrolled 43 critically ill patients and 25 healthy controls. Longitudinal blood samples were collected at ICU admission (24–48 h) and days 4 (4d), 8 (8d), and 14 (14d). We quantified the mRNA expression of four GCR variants (GCR-α, GCR-β, GCR-γ, and GCR-P) and GC downstream targets (GILZ and DUSP1) in isolated polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) via RT‒PCR. Serum cortisol, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cytokines (interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10) were measured concurrently. Statistical analyses included mixed-effects modeling to assess temporal and cell-specific patterns.

Results

PMNs exhibited sustained downregulation of GCR-α, GCR-β, and GCR-γ, with preserved GILZ expression, while GCR-P remained stable. In PBMCs, GCR-α, GCR-β, GCR-γ, and GILZ levels showed no significant changes compared to controls, yet GCR-P was upregulated. DUSP1 was downregulated in PMNs and elevated in PBMCs. Negative correlations emerged between IL-6 and both GILZ and DUSP1. All expression patterns remained stable across time points in the subset of patients who completed the 2-week study despite dynamic ACTH changes and persistently elevated cortisol.

Conclusions

PMNs show reduced GCR-α/β/γ with preserved GILZ, while PBMCs maintain GCR-α/β/γ but upregulate GCR-P and DUSP1. These findings highlight divergent GC responsiveness between innate and adaptive immune cells, with implications for cortisol’s role in immune regulation during critical illness and may reflect cell-specific effects driven by changes in glucocorticoid receptor signaling.

Keywords: GCR isoforms, GILZ, DUSP1, Immune cells, GC sensitivity

Background

In critical illness, including trauma, sepsis, and major surgery, cortisol plays a vital role in maintaining homeostasis by regulating immune responses, promoting vascular repair, and controling balanced responses during stress and inflammation [1]. In addition to the levels of endogenous cortisol, the sensitivity of target tissues to cortisol is an important determinant of its activity. Glucocorticoid hormone signaling occurs mainly through glucocorticoid receptors (GCRs). These receptors exist in multiple isoforms generated through alternative splicing and post-translational modifications, with the most extensively studied being GCR-α and GCR-β [2]. GCR-α is the active isoform that binds to glucocorticoids (GCs) and regulates the transcription of anti-inflammatory genes, whereas GCR-β, which does not bind GCs, can inhibit GCR-α function by acting as a dominant-negative regulator [3–5]. In addition to GCR-α and GCR-β, other isoforms, including GCR-γ and GCR-P, which have been less characterized, have been described [6]. Importantly, these isoforms have not been studied in the context of critical illness.

The glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper gene (GILZ) is transcriptionally activated mainly by cortisol. It acts as a pivotal mediator of its anti-inflammatory effects by regulating the function of both adaptive and innate immune cells [7]. Dual-specific phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) is another central regulator of innate immunity whose expression can profoundly affect the outcome of inflammatory challenges [8] and is, at least in part, induced by GCs.

Polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), mainly neutrophils, respond rapidly to GCs, which affect their chemotaxis, apoptosis, and cytokine production. The sensitivity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to GCs also affects systemic inflammation [9]. In ICU patients, both PMNs and PBMCs show dynamic changes in GCR isoforms due to stress, inflammation, and steroid treatment [10]. Critically ill individuals often have increased GCR-β and reduced GCR-α activity, leading to glucocorticoid resistance (GR), a state in which immune cells become less responsive to steroid therapy [4, 5]. This resistance can lead to persistent production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in monocytes and impair apoptosis and the resolution of inflammation in neutrophils [11–13].

The biological effects of GCs depend not only on their circulating levels but also on their individual and tissue-specific sensitivity [10]. Variations in GC sensitivity between individuals and across tissues in the same individual are well documented in both health and disease [14]. In critical illness, altered GC sensitivity in immune cells can influence stress responses and treatment efficacy. Divergent findings on GC action in critical illness may stem not only from differences in study populations but also from variations in the specific immune cell types examined [15–17]. Most studies have reported generalized GC resistance, mainly in sepsis, on the basis of single-cell analyses [18–20]. Recently, Teblick et al. demonstrated cell-specific GC sensitivity in critically ill (mostly septic) patients, supporting leukocyte-specific rather than systemic resistance [16].

To explore this further, we characterized the cell type-specific expression patterns of the well-studied glucocorticoid receptor isoforms GCR-α and GCR-β and the less-studied GCR-γ and GCR-P, as well as the downstream GC targets (GILZ and DUSP1) in two distinct immune cell populations, PMNs and PBMCs, in critically ill patients. We additionally performed longitudinal measurements to capture cell-specific changes in glucocorticoid sensitivity over time and to explore whether neutrophils and monocytes may exhibit divergent and phase-dependent responses during acute and subacute critical illness. We focused on a patient population with no clinical indications for GC therapy who exhibited moderate inflammatory responses, as evidenced by the measured levels of interleukin (IL)−6 and IL-10, allowing us to assess GC sensitivity in the absence of confounding hyperinflammation.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, observational, single-center study conducted in the intensive care unit (ICU) of Evangelismos General Hospital, Athens, Greece, between February 2024 and October 2024. The unit is a general ICU admitting unselected critically ill patients, including trauma patients. The institutional ethics committee approved the study (444–28/09/2023). Informed consent was obtained from all patients’ legal surrogates prior to inclusion.

Patients

Prior to enrollment, all consecutively admitted patients were screened for eligibility. The exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, pregnancy, brain death, malignancies, readmission or transfer from another ICU, contagious diseases (human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis), and oral intake of corticosteroids at an equivalent dosage of ≥ 1 mg/kg prednisone/day for a period of more than 1 month prior to ICU admission and the administration of steroids during the ICU stay (e.g., hydrocortisone for septic shock). Upon admission to the ICU, the following variables were recorded: age, sex, type of disease (medical, surgical, or trauma patients), and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II (APACHE II) and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores. The Sepsis-3 definitions were used to classify septic patients [21]. The durations of ICU stay and mortality (28-day and ICU mortality) were also recorded. Twenty-five age- and sex-matched healthy blood donors composed the control group and were used for comparisons.

Blood collection - Polymorphonuclear (PMN) and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation

Blood samples and clinical data were obtained within 48 h of ICU admission and at 3 additional time points. Two venous blood samples were drawn in blue-topped Vacutainers citrate tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) between 08.00 and 08.30 h at four time points: within 48 h following ICU admission (24–48 h, baseline) and on days 4 (4d), 8 (8d), and 14 (14d). Blood sampling was not performed if hydrocortisone was administered to the patients due to the development of septic shock, according to international guidelines [21]. Therefore, blood sampling was discontinued at hydrocortisone administration or if discharge or death occurred. In these cases, the patient was withdrawn from the study at that point, and no more samples were drawn. Two blood samples were also drawn from 25 healthy blood donors.

PMNs were isolated from peripheral blood as previously described in detail [22]. Briefly, blood was collected in citrate and allowed to sediment. The leukocyte-rich supernatant was collected, and any remaining erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock. PMNs were separated via gradient centrifugation on Histopaque (Sigma, Sigma‒Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA). PBMCs were isolated via Lymphosep separation medium (Biowest, Nuaillé, France) by banding the mononuclear cells above the medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated PMNs and PBMCs were resuspended in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction.

Total RNA extraction and quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the PMNs and PBMCs, the RNA was reverse transcribed, and a highly sensitive quantitative real-time PCR method was used to measure the mRNA expression of the NR3C1 gene variants, namely, GCR-α, GCR-β, GCR-γ, and GCR-P. The GCR downstream targets GILZ and DUSP1 were also quantified. Using the comparative CT method 2−DDCT [23] and healthy donor samples as calibrators, the relative quantification of the expression analysis of all blood samples from critically ill patients was carried out. The endogenous reference genes CYPA and GAPDH were used for gene expression normalization. Table 1 lists the sequences of the primers used.

Table 1.

Sequence of the primers used

| Gene | Sequence (5’−3’) | nt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYPA | F | 5’-GCTGGACCCAACACAAATGC-3’ | 20 |

| R | 5’-TTGCCAAACACCACATGCTT-3’ | 20 | |

| DUSP1 | F | 5’-CAACCACAAGGCAGACATCAGC-3’ | 22 |

| R | 5’-GTAAGCAAGGCAGATGGTGGCT-3’ | 22 | |

| GAPDH | F | 5’-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG-3’ | 19 |

| R | 5’-GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA-3’ | 22 | |

| GCR-α | F | 5’-CCTAAGGACGGTCTGAAGAGC-3’ | 21 |

| R | 5’-GCCAAGTCTTGGGCCTCTAT-3’ | 20 | |

| GCR-β | F | 5’-AACTGGCAGCGGTTTTATCAA-3’ | 21 |

| R | 5’-TGTGAGATGTGCTTTCTGGTTTAAA-3’ | 25 | |

| GCR-γ | F | 5’-TTCAAAAGAGCAGTGGAAGGTA-3’ | 22 |

| R | 5’-GGTAGGGGTGAGTTGTGGTAACG-3’ | 23 | |

| GCR-P | F | 5’-GGAGAAAAAGGCGCATCCTA-3’ | 20 |

| R | 5’-TGCTATGTTAACCAATCCCCAAT-3’ | 23 | |

| GILZ | F | 5’-GGACTTCACGTTTCGTGGACA-3’ | 21 |

| R | 5’-AATGCGGCCACGGATG-3’ | 16 |

CYPA, cyclophilin A; DUSP1, dual specificity protein phosphatase 1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GCR, glucocorticoid receptor; GILZ, glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper

Human serum

Blood sampling was performed as described in the section “Blood collection - Polymorphonuclear (PMN) and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation”. Blood samples were collected in red-topped Vacutainers tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and serum was prepared according to standard procedures.

Adrenocortical function

Cortisol was determined in patient serum samples drawn at all 4 time points via a chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) (morning normal values: 5–25 µg/dl). Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was measured via an immunochemiluminometric assay (ICMA) (normal values: 9–52 pg/ml). Both were measured on an Immulite 2000 system (Siemens Healthineers AG, Forchheim, Germany).

Measurement of cytokines

Interleukin (IL)−6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels were measured in patient sera drawn at all 4 time points via immunoassays purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA; detection limits for IL-6, 0.92 pg/ml; IL-10, 2 pg/ml; and TNF-α, 5 pg/ml), according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normality via the Shapiro–Wilk test and summarized as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or means ± standard deviations (SDs) as appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages. Two-group comparisons were performed with the Student’s t test or the nonparametric Mann‒Whitney test for skewed data. Kruskal‒Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used for comparisons of more than two groups. To analyze longitudinal changes in gene expression between PMNs and PBMCs while accounting for repeated measures within patients, we used a mixed-effects model with random intercepts for each subject, followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. Correlations were evaluated via Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify potential risk factors for ICU mortality. The examined variables entered in the analysis were the expression levels of the genes studied and the cytokine levels. All the aforementioned analyses were performed via GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 for MacOS (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA; www.graphpad.com). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

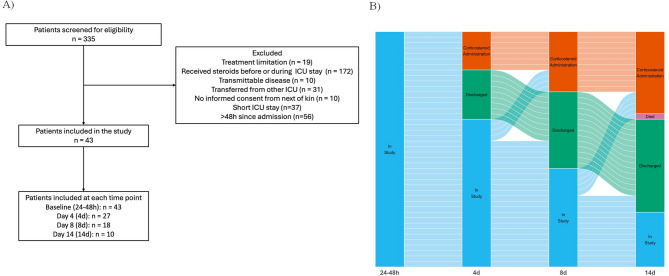

A total of 43 patients were included in the final study group. Demographic data, clinical characteristics at ICU admission, comorbidities, physiologic parameters, and laboratory findings are summarized in Table 2. ICU admission diagnosis included medical pathologies (decreased level of consciousness, infections, heat stroke, poisoning, acute pancreatitis, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke), surgery (post-operative abdominal and neurosurgery cases), and trauma, including traumatic brain injury. The study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics, laboratory values, and outcomes of the study population

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 58 (51–68) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 18 (41.9) |

| Type of Admission | |

| Medical, n (%) | 15 (34.9) |

| Surgical, n (%) | 16 (37.2) |

| Trauma, n (%) | 12 (27.9) |

| Sepsis on Admission | 2 (4.6) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 26.5 (25.3–28.8) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale on admission | 13.0 (6.5–15.0) |

| SOFA score | 7 (3 − 9) |

| APACHE II score | 12.0 (8.0–17.5) |

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 2 (4.7) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 13 (30.2) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 14 (32.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (7.0) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 3 (7.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 2 (4.6) |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 1 (2.3) |

| Hemodynamics | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 80 (70–93) |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 80 (75–89) |

| Vasopressor administration, n (%) | 27 (62.8) |

| Fluid balance, ml | 1500 (1045–2325) |

| Ventilation | |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 30 (69.8) |

| Inspired oxygen fraction (%) | 40 (35–50) |

| High-flow oxygen therapy, n (%) | 3 (7.0) |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 23 (19–25) |

| Arterial Blood Gases | |

| PaO₂, mmHg | 115 (90.5–129.5) |

| PaCO₂, mmHg | 37.0 (35.1–40.0) |

| pH | 7.35 (7.32–7.38) |

| Serum lactate, mmol/l | 1.2 (1.0–1.9) |

| Laboratory Values | |

| White blood cell count, cells/µl | 11,090 (8,965–15,975) |

| Platelet count, ×10³/µl | 205 (145–285) |

| Hematocrit, % | 32.9 (28.1–36.6) |

| INR | 1.08 (1.00–1.17) |

| APTT, seconds | 29.5 (27.4–34.2) |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 123 (99–156) |

| Urea, mg/dl | 26 (20–38) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| Sodium, mEq/l | 141 (138 − 145) |

| Potassium, mEq/l | 4.3 (4.0–4.5) |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.4 (3.0–3.9) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.46 (0.35–0.77) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/l | 24 (15–38) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/l | 29 (16–45) |

| Creatine phosphokinase, U/l | 169 (56–646) |

| Troponin, ng/l | 21 (8 − 100) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dl | 7.2 (2.05–16.15) |

| Procalcitonin, ng/ml | 0.29 (0.09–0.68) |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone, µIU/ml | 0.94 (0.48–2.14) |

| Cytokines on Admission | |

|

IL-6, pg/ml IL-10, pg/ml |

41.8 (19.5-119.3) 16.1 (13.4–26.4) |

| Outcomes | |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 6 (23.3) |

| ICU length of stay, days | 14.0 (7.0–33.5) |

| Days on mechanical ventilation | 10.0 (0.0–22.0) |

| ICU survival, n (%) | 34 (79.1) |

Data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges) or numbers (percentages), unless otherwise indicated. Variables with a normal distribution are presented as the means ± standard deviations. The level of TNF-α was below the detection limit in all patients. APACHE II = acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; ICU = intensive care unit; IL = interleukin; INR = international normalized ratio; PaO2 = partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2 = partial pressure of carbon dioxide; SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. A: A total of 335 patients were screened for eligibility. After applying the exclusion criteria, 43 patients were ultimately included in the study. Serial blood samples were collected at up to four time points during the ICU stay. B: Alluvial plot showing the decreasing number of samples at later time points reflecting patient discharge (N= 17), death (N= 1), or corticosteroid administration (N= 15). The alluvial plot was created using the ggplot2 and ggalluvial libraries of the R coding language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)

Adrenocortical function in critically ill patients

The changes in the endogenous baseline cortisol and ACTH levels during the 2-week study period are shown in Fig. 2A-B. The mean endogenous baseline cortisol concentration remained essentially high and unaltered (Fig. 2A; p = ns, by Kruskal‒Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test). At all time points studied, cortisol levels were above 10 µg/dl in the vast majority of patients. More specifically, 4/43 (9.3%, 24–48 h), 0/27 (0%, 4d), 2/18 (11.1%, 8d), and 1/10 (10%, 14d) had cortisol levels < 10 µg/dl. ACTH increased significantly at time points 2 and 3 compared with the baseline value (Fig. 2B; p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively, by Kruskal‒Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test).

Fig. 2.

Admission baseline cortisol (A) and ACTH (B) levels over the 14-day study period in critically ill patients. A-B: Cortisol (A) and ACTH (B) were measured in critically ill patients at four different time points: baseline (24–48 h) and on days 4 (4d), 8 (8d), and 14 (14d). Blood sampling was discontinued if hydrocortisone was administered or if death or discharge occurred. B: The horizontal line represents the normal cutoff value for critically ill patients (10 µg/dl), based on the criteria for critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) [45]. The data are presented as box plots: line in the middle, median value; lower and upper lines, 25th to 75th centiles; bullet points, outliers. B: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 from baseline values using Kruskal‒Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. ACTH = adrenocorticotropin

GCR-α, GCR-β, GCR-γ, and GCR-P mRNA expression in the PMNs of critically ill patients and healthy blood donors

Kruskal‒Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used to test for differences in gene expressions between healthy controls and the 4 time-points in critically ill patients, in both PMNs and PBMCs.

Compared with healthy controls (HCs), critically ill patients presented decreased GCR-α mRNA expression at the first three time points, returning to control levels by 14d (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.50 (0.26–0.77), p < 0.001; 4d, median (IQR): 0.31 (0.17–0.66), p < 0.0001; 8d, median (IQR): 0.30 (0.15–0.83), p < 0.001; 14d, median (IQR): 0.75 (0.20–1.20), p = ns; all p values vs. HC median (IQR): 1.00 (0.77–1.36); Fig. 3A). Similarly, the GCR-β mRNA expression levels were lower than those in the controls. Specifically, critically ill patients presented decreased expression of GCR-β at time points 24–48 h and 14d, whereas time points 4d and 8d did not show any change in expression (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.20 (0.04–0.49), p < 0.001; 4d, median (IQR): 0.34 (0.14–0.91), p = ns; 8d, median (IQR): 0.46 (0.10–0.79), p = ns; 14d, median (IQR): 0.17 (0.02–0.33), p < 0.05; all p values vs. HC median (IQR): 1.00 (0.31–1.47); Fig. 3B). With respect to the two other isoforms of GCR studied, GCR-γ presented the same expression pattern, i.e., decreased mRNA levels in patients compared with controls (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.51 (0.29–0.85), p < 0.05; 4d, median (IQR): 0.36 (0.25–0.68), p < 0.0001; 8d, median (IQR): 0.40 (0.34–0.51), p < 0.01; 14d, median (IQR): 0.36 (0.29–0.59), p < 0.01; all p values vs. HC median (IQR): 1.00 (0.71–1.36); Fig. 3C). The GCR-P isoform displayed a different expression pattern; no significant differences were found at any time point compared with controls (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.66 (0.40–1.10); 4d, median (IQR): 0.67 (0.47–1.29); 8d, median (IQR): 0.90 (0.32–1.64); 14d, median (IQR): 1.55 (0.55–2.02); all p = ns vs. HC median (IQR): 1.01 (0.75–1.93); Fig. 3D). While we observed significant differences in GCR isoform expression between patients and healthy controls, analysis revealed no statistically significant changes in the expression of any GCR isoform across time points within the patient cohort.

Fig. 3.

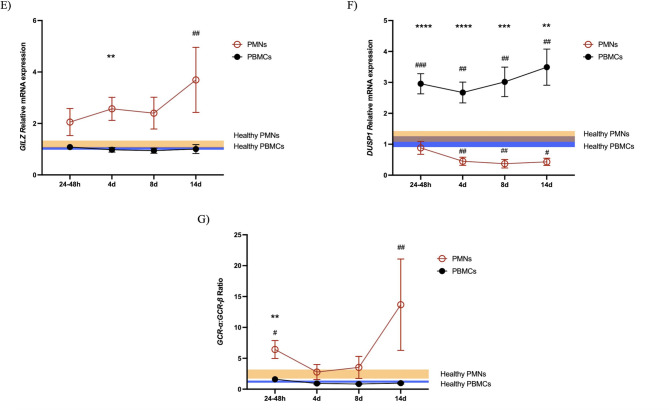

Relative mRNA expression of all genes studied in the PMNs and PBMCs of critically ill patients. The relative expression of GCR-α (A), GCR-β (B), GCR-γ (C), GCR-P (D), GILZ (E), DUSP1 (F), and GCR-α:GCR-β (G) was measured in 43 critically ill patients at four different time points: on ICU admission (24–48 h; N = 43) and on days 4 (4d; N = 27), 8 (8d; N = 18) and 14 (14d; N = 10). Blood sampling was discontinued if hydrocortisone was administered or if death or discharge occurred. The data are presented as connected column means with standard errors of the means (SEMs). Comparisons against the healthy control group were performed for each cell type via Kruskal‒Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. The two cell types were compared via mixed effects analysis followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. The blue area represents the expression in the PMNs of healthy controls (mean ± SEM), and the orange area represents the expression in the PBMCs of healthy controls (mean ± SEM). The brown area results from their overlap

GCR-targeted gene mRNA expression in the PMNs of critically ill patients and healthy blood donors

Compared with healthy controls, critically ill patients presented with high-normal GILZ expression levels, reaching significance at time point 14d (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.98 (0.37–2.26), p = ns; 4d, median (IQR): 2.02 (0.51–4.60), p = ns; 8d, median (IQR): 1.64 (0.65–3.27), p = ns; 14d, median (IQR): 1.94 (1.12–5.88), p < 0.05; all p values vs. HC median (IQR): 1.00 (0.81–1.55); Fig. 3E). On the other hand, DUSP1, which is also at least partially induced by GCs, was downregulated in the PMNs of critically ill patients from 4d to 14d compared with those of controls (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.39 (0.19–1.13), p = ns; 4d, median (IQR): 0.21 (0.10–0.56), p < 0.01; 8d, median (IQR): 0.20 (0.10–0.35, p < 0.01; 14d, median (IQR): 0.31 (0.15–0.68), p < 0.05; all p values vs. HC median (IQR): 1.00 (0.31–1.73); Fig. 3F). GILZ and DUSP1 expression was maintained at constant levels across all measured time points in the patients.

GCR-α, GCR-β, GCR-γ, and GCR-P mRNA expression in the PBMCs of critically ill patients and healthy blood donors

Compared with healthy controls (HCs), critically ill patients presented similar GCR-α mRNA expression at all time points (24–48 h, median (IQR): 1.17 (0.79–1.69); 4d, median (IQR): 0.90 (0.69–1.26); 8d, median (IQR): 0.94 (0.52–1.26); 14d, median (IQR): 0.86 (0.67–1.26); all p = ns vs. HC median (IQR): 1.08 (0.82–1.18); Fig. 3A). Similarly, the GCR-β and GCR-γ mRNA expression levels did not differ from those of the controls (GCR-β: 24–48 h, median (IQR): 1.01 (0.65–1.43); 4d, median (IQR): 1.30 (0.71–1.80); 8d, median (IQR): 1.07 (0.81–1.76); 14d, median (IQR): 0.99 (0.73–1.47); all p = ns vs. HC median (IQR): 1.27 (0.50–1.80); Fig. 3B; GCR-γ: 24–48 h, median (IQR): 1.24 (0.88–1.79); 4d, median (IQR): 1.09 (0.83–1.50); 8d, median (IQR): 1.03 (0.59–1.32); 14d, median (IQR): 0.92 (0.73–1.41); all p = ns vs. HC median (IQR): 1.01 (0.84–1.24); Fig. 3C). With respect to the GCR-P, its levels increased at all time points studied compared with those of HCs (24–48 h, median (IQR): 4.50 (2.27–6.37), p < 0.0001; 4d, median (IQR): 3.52 (1.72–5.10), p < 0.001; 8d, median (IQR): 3.57 (1.71–5.16), p < 0.01; 14d, median (IQR): 2.85 (1.81–5.57), p < 0.05 vs. HC median (IQR): 0.85 (0.60–2.22); Fig. 3D). In addition to these different expression patterns, the expression of GCR-P, as the other isoforms, remained stable throughout the observation period.

GCR-targeted gene mRNA expression in the PBMCs of critically ill patients and healthy blood donors

Compared with healthy controls, critically ill patients did not show differences in GILZ expression at any time point studied (24–48 h, median (IQR): 0.91 (0.64–1.55); 4d, median (IQR): 0.93 (0.65–1.19); 8d, median (IQR): 0.87 (0.60–1.08); 14d, median (IQR): 0.79 (0.53–1.30); all p = ns vs. HC median (IQR): 1.06 (0.79–1.21); Fig. 3E). On the other hand, DUSP1 was upregulated in the PBMCs of critically ill patients at all time points compared with those of controls (24–48 h, median (IQR): 2.47 (1.63–3.87), p < 0.001; 4d, median (IQR): 2.33 (1.17–4.23), p < 0.01; 8d, median (IQR): 2.25 (1.46–5.16, p < 0.01; 14d, median (IQR): 3.44 (1.76–5.01), p < 0.001; all p values vs. HC median (IQR): 0.95 (0.61–2.12); Fig. 3F). GILZ and DUSP1 did not significantly change over time in patients.

Differences in gene expression patterns between PMNs and PBMCs from critically ill patients

We subsequently investigated differences in gene expression patterns between PMNs and PBMCs to gain further insight into cell specificity. Analysis was performed using the mixed effects model followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison tests. Compared with PMN cells, PBMCs expressed higher levels of all the GCR isoforms studied, namely, GCR-α, GCR-β, GCR-γ, and GCR-P (Fig. 3A-D). Interestingly, GILZ seemed to be expressed at higher levels in the PMNs of critically ill patients (Fig. 3E), whereas DUSP1 was expressed at higher levels in the PBMCs (Fig. 3F). Another interesting finding from these comparisons was that the GCR-α:GCR-β ratio in the PMNs was greater than that in the PBMCs at ICU admission (Fig. 3G).

Cytokine expression and correlations in critically ill patients

The cytokine levels at ICU admission are presented in Table 2. Notably, the TNF-α concentration was below the detection limit in all patients. We then explored the correlations of IL-6 and IL-10 with the genes studied. In both cell lines, IL-6 levels were negatively correlated with GILZ and DUSP1 expression, whereas we found no correlation with the GCR variants. Specifically, in PMNs, the levels of IL-6 at admission were negatively correlated with GILZ (r= −0.47, p = 0.002) and DUSP1 (r= −0.51, p = 0.001) levels. IL-10 correlated negatively with GILZ (r= −0.34, p = 0.034) but tended to negatively correlate with DUSP1 without reaching statistical significance (r= −0.30, p = 0.054). In PBMCs, IL-6 correlated negatively with GILZ (r= −0.48, p = 0.001) and DUSP1 (r=−0.35, p = 0.022). We also explored the correlations between cortisol and ACTH levels and the expression of the studied genes. No correlation was found in the PMNs. In PBMCs, cortisol tended to have a weak negative correlation with GCR-α (r= −0.29, p = 0.056), while ACTH positively correlated with GILZ expression (r = 0.45, p = 0.0023).

Patients were subsequently categorized into survivors and non-survivors, and t-tests were performed to seek differences between the two groups; no differences were observed in cytokine levels or gene expression levels on ICU admission in either cell population studied. Moreover, multiple logistic regression analysis using ICU mortality as a binary outcome revealed that ICU admission cytokine levels and expression of the genes studied were not associated with ICU mortality.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the expression patterns of GCR isoforms and downstream target genes in PMNs and PBMCs, as well as the levels of endogenous ACTH and cortisol in critically ill patients over a two-week period. Notably, the measured parameters, except for ACTH, which increased at later time points, remained stable across the acute and subacute phases (up to 14 days). Despite persistently elevated endogenous cortisol levels and dynamic ACTH changes, patients exhibited a sustained downregulation of GCR-α, GCR-β, and GCR-γ (but not GCR-P) in PMNs. Conversely, in PBMCs, GCR-α, GCR-β, and GCR-γ levels showed no temporal variation and remained comparable to those in healthy controls, whereas GCR-P was consistently upregulated. Glucocorticoid-induced genes such as GILZ and DUSP1 correlated negatively with the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-10 on ICU admission and demonstrated cell-specific alterations (GILZ was elevated in PMNs, and DUSP1 was upregulated in PBMCs), with stable expression patterns over time. These findings suggest that critical illness induces complex, cell-specific, yet temporally stable adaptations in glucocorticoid signaling pathways, with potential implications for immune regulation.

Previous studies on the expression of GCR-α and GCR-β in critically ill patients have yielded variable results, depending largely on the admission diagnosis, septic status, and cell type studied, highlighting the existence of population- and cell-specific variation. Most studies in critically ill patients report decreased GCR-α in PMNs across different etiologies [16, 17, 24]. The regulation of GCR-β in PMNs varies and is undetectable in some critically ill populations [16] or shows biphasic changes [24]. Studies in PBMCs show distinct regulatory patterns. Most reports describe downregulated GCR-α [16, 18–20, 25] or unaltered expression [26] with concurrent GCR-β upregulation [18–20, 25], considered dysfunctional GCR-α-mediated glucocorticoid action, described as glucocorticoid resistance. Only one study reported undetectable levels of GCR-β, in which GILZ was elevated [16].

In our study, we observed downregulation of GCR-α and GCR-β expression in PMNs, which was not mirrored by GILZ expression; instead, GILZ showed consistently high-normal levels across all time points, suggesting preserved glucocorticoid responsiveness despite reduced receptor levels. This may be explained by the high-normal ratio of active GCR-α to inactive GCR-β isoforms, a known marker of glucocorticoid sensitivity [27]. In contrast to the changes we observed in PMNs, the expression patterns in PBMCs were significantly different; GCR-α and GCR-β levels remained unchanged compared with those in healthy controls. Unlike PMNs, where a high-normal GCR-α:GCR-β ratio seemed to sustain glucocorticoid sensitivity (high-normal GILZ) despite receptor downregulation, PBMCs showed no such shift (normal GCR-α:GCR-β ratio and normal GILZ). Our observation of high-normal GILZ in the PMNs of a low-inflammation population contrasts with the reported GILZ suppression observed in hyperinflammatory states [16]; however, our previous work in brain injury patients revealed late GILZ upregulation [17].

In addition to the well-characterized GCR-α and GCR-β, other alternative isoforms, including GCR-γ and GCR-P, have not been studied in critical illness. GCR-γ is ubiquitously expressed [28, 29]. Few, but not all [30] studies, have linked altered GCR-γ expression to the GC response, acting mainly as a dominant-negative regulator and potentially contributing to the GC resistance commonly observed in chronic inflammatory diseases [29, 31]. The GCR-P receptor isoform was first identified in glucocorticoid-resistant multiple myeloma cells [32–34]. Unlike classical glucocorticoid receptors, GCR-P cannot bind GCs and has been shown to modulate GCR-α transcriptional activity in a cell type-specific manner [6]. Early studies in hematologic malignancies associated elevated GCR-P expression with glucocorticoid resistance [32–34], while later work demonstrated that it could enhance GCR-α activity in primary myeloma patient cells and transfected cell lines [35].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the expression of these two isoforms in critically ill patients. We found that in critically ill patients’ PMNs, the expression of GCR-γ was lower than that in controls, whereas there was no difference in the expression of GCR-P. In PBMCs, patients and healthy controls presented similar expression levels of GCR-γ, whereas GCR-P expression was increased in patients. Comparisons between the two cell populations from critically ill patients revealed that PBMCs presented higher expression of GCR-γ and GCR-P than PMNs. Our study provides the first evidence of GCR-P regulation in critical illness, revealing its selective upregulation in PBMCs and lack of downregulation, unlike the other glucocorticoid receptors, in PMNs. This differential expression pattern may contribute to the distinct glucocorticoid response profiles between these cell populations. How the expression of these isoforms modulates GC function remains to be explored in future studies.

In addition to GILZ, glucocorticoids exert anti-inflammatory effects in part by inducing DUSP1 [8, 36, 37]. DUSP1 was first described as an immediate early gene induced by heat shock and oxidative stress [38]. Subsequent studies have shown that DUSP1 is strongly induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and IL-10, among others [39–42]. In preclinical models of infection and sepsis, research on DUSP1 has predominantly investigated its regulation of macrophage function, establishing its essential role in mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of GCs in vivo [41, 42]. However, no clinical studies have examined the relationship between DUSP1 and GCR isoform expression across immune cell subsets.

In the present study, we found that, in critically ill patients’ PMNs, the expression of DUSP1 was lower than that in controls, whereas in PBMCs, DUSP1 expression was upregulated in patients. A comparison of the two cell populations from critically ill patients revealed much greater expression in PBMCs.

In PMNs, GILZ was high-normal with a simultaneous reduction of DUSP1. In PBMCs, GILZ levels remained normal; however, DUSP1 levels were significantly increased. These findings indicate that glucocorticoid responsiveness is not uniform across target genes, even within the same cell type. The preserved upregulation of GCR-P in PBMCs, in contrast with the generalized receptor downregulation observed in PMNs, could theoretically contribute to their distinct glucocorticoid response profile; however, the biological functions of this isoform remain largely undefined. We cannot rule out that the isolated increase in DUSP1 may instead reflect cytokine (e.g., IL-10)-mediated induction, underscoring how anti-inflammatory responses in PBMCs can bypass classical glucocorticoid pathways.

Our study also sought to establish whether these cell-specific alterations in glucocorticoid signaling in PMNs and PBMCs are maintained through the acute and subacute phases of critical illness. The absence of temporal variation in glucocorticoid sensitivity markers may reflect either early and persistent reprogramming of glucocorticoid signaling pathways that remain throughout the disease course or the presence of robust functional glucocorticoid signaling homeostasis despite systemic inflammatory changes. The dynamic gene expression patterns in PMNs and PBMCs across acute and subacute phases of critical illness suggest cell-type-specific adaptations in glucocorticoid sensitivity and immune regulation. Time-dependent differences in GCR expression and signaling may reflect the body’s struggle to balance inflammatory and immunosuppressive responses during severe illness.

Our study has several strengths, including longitudinal analysis of immune gene expression in two cell types, namely, PMNs and PBMCs, measurement of multiple GCR isoforms, downstream targets, cytokine levels, and the inclusion of a low inflammatory population, excluding patients receiving corticosteroids. However, residual heterogeneity in the underlying conditions of critically ill patients may confound our findings. Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the expression of the GCR isoforms, GILZ, and DUSP1 was measured at the mRNA level only and may not reflect functional protein levels or activity, limiting our ability to draw mechanistic conclusions. Second, PBMCs represent a heterogeneous cell population, and gene expression changes cannot be attributed to specific immune subsets. We also only measured total cortisol. Free cortisol, which is technically demanding to measure, mirrors better cortisol availability [43] and may be important in understanding the lack of changes in GCR isoforms over time and the changes in downstream targets in PBMCs and PMNs. Nevertheless, in critical illness, tissue cortisol levels have been shown to correlate to a moderate degree with both total and free cortisol [44]. Finally, our cohort had a relatively small sample size, yet comparable to similar studies on GCR expression in critically ill patients, and an under-represented sepsis rate on ICU admission. Future studies should validate these findings in larger cohorts with higher sepsis prevalence to ensure broader applicability.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that critical illness triggers distinct GC responses, with PMNs and PBMCs exhibiting distinct patterns of receptor isoform expression and downstream target gene activation. Notably, in PMNs, GCR-α, GCR-β, and GCR-γ expression was downregulated, but it remained largely unchanged in PBMCs. However, PMNs sustained GILZ levels, whereas DUSP1 decreased, and PBMCs displayed a shift in GC signaling toward elevated DUSP1 without altered GILZ levels.

These cell-specific responses seem to remain stable over time in the subset of patients who completed the study and may reflect intrinsic differences in their glucocorticoid receptor signaling networks, modulating their inflammatory response.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the “Stavros Niarchos Foundation” (NSL and AGV).

Abbreviations

- APACHE II

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II

- CYPA

Cyclophilin A

- DUSP1

Dual specificity protein phosphatase 1

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GC

Glucocorticoid

- GCR

Glucocorticoid receptor

- GILZ

Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper

- GR

Glucocorticoid resistance

- IL

Interleukin

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cel

- PMN

Polymorphonuclear cell

- SOFA

Sequential organ failure assessment

Author contributions

GP, NSL, and CK conducted the experiments and drafted the manuscript. VI, AH, and EB collected and processed the samples and recorded patient data. KAP, MT, AGP, and AK provided valuable input to the study design. CSV supervised patient enrollment, data collection, and recording. CSV and DAV edited the manuscript and provided valuable input to the study design. AGV and ID designed and supervised the study; supervised patient enrollment, data collection, and recording; and edited the manuscript. All the authors have agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The current research received no external funding.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research ethics committee of “Evangelismos” Hospital approved the study (444–28/09/2023). Informed written consent was obtained from all patients’ legal surrogates prior to inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

G. Poupouzas and NS Lotsios contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Alice G Vassiliou, Email: alvass75@gmail.com.

Ioanna Dimopoulou, Email: idimo@otenet.gr.

References

- 1.Meduri GU. Glucocorticoid receptor alpha: origins and functions of the master regulator of homeostatic corrections in health and critical illness. Explor Endocr Metab Dis. 2025;2:101426 .

- 2.Hollenberg SM, Weinberger C, Ong ES, Cerelli G, Oro A, Lebo R, et al. Primary structure and expression of a functional human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA. Nature. 1985;318(6047):635–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamberger CM, Bamberger AM, de Castro M, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor beta, a potential endogenous inhibitor of glucocorticoid action in humans. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(6):2435–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kino T, Manoli I, Kelkar S, Wang Y, Su YA, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) beta has intrinsic, GRalpha-independent transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381(4):671–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kino T, Su YA, Chrousos GP. Human glucocorticoid receptor isoform beta: recent understanding of its potential implications in physiology and pathophysiology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(21):3435–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lockett J, Inder WJ, Clifton VL. The glucocorticoid receptor: isoforms, functions, and contribution to glucocorticoid sensitivity. Endocr Rev. 2024;45(4):593–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayroldi E, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ): a new important mediator of glucocorticoid action. FASEB J. 2009;23(11):3649–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joanny E, Ding Q, Gong L, Kong P, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Anti-inflammatory effects of selective glucocorticoid receptor modulators are partially dependent on up-regulation of dual specificity phosphatase 1. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(4b):1124–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke SA, Eng PC, Comninos AN, Lazarus K, Choudhury S, Tsang C, et al. Current challenges and future directions in the assessment of glucocorticoid status. Endocr Rev. 2024;45(6):795–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meduri GU, Chrousos GP. General adaptation in critical illness: glucocorticoid receptor-alpha master regulator of homeostatic corrections. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torrego A, Pujols L, Roca-Ferrer J, Mullol J, Xaubet A, Picado C. Glucocorticoid receptor isoforms alpha and beta in in vitro cytokine-induced glucocorticoid insensitivity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):420–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McColl A, Michlewska S, Dransfield I, Rossi AG. Effects of glucocorticoids on apoptosis and clearance of apoptotic cells. Sci World J. 2007;7:1165–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Kebir D, Filep JG. Role of neutrophil apoptosis in the resolution of inflammation. Sci World J. 2010;10:1731–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quax RA, Manenschijn L, Koper JW, Hazes JM, Lamberts SW, van Rossum EF, et al. Glucocorticoid sensitivity in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(11):670–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassiliou AG, Athanasiou N, Keskinidou C, Jahaj E, Tsipilis S, Zacharis A, et al. Increased glucocorticoid receptor alpha expression and signaling in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(12):2131–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Téblick A, Van Dyck L, Van Aerde N, Van der Perre S, Pauwels L, Derese I, et al. Impact of duration of critical illness and level of systemic glucocorticoid availability on tissue-specific glucocorticoid receptor expression and actions: a prospective, observational, cross-sectional human and two translational mouse studies. EBioMedicine. 2022;80:104057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotsios NS, Vrettou CS, Poupouzas G, Chalioti A, Keskinidou C, Pratikaki M, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor response and glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper expression in neutrophils of critically ill patients with traumatic and non-traumatic brain injury. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15: 1414785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerrero J, Gatica HA, Rodriguez M, Estay R, Goecke IA. Septic serum induces glucocorticoid resistance and modifies the expression of glucocorticoid isoforms receptors: a prospective cohort study and in vitro experimental assay. Crit Care. 2013;17(3): R107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ledderose C, Mohnle P, Limbeck E, Schutz S, Weis F, Rink J, et al. Corticosteroid resistance in sepsis is influenced by microRNA-124–induced downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor-alpha. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(10):2745–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molijn GJ, Koper JW, van Uffelen CJ, de Jong FH, Brinkmann AO, Bruining HA, et al. Temperature-induced down-regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in peripheral blood mononuclear leucocyte in patients with sepsis or septic shock. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;43(2):197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vassiliou AG, Floros G, Jahaj E, Stamogiannos G, Gennimata S, Vassiliadi DA, et al. Decreased glucocorticoid receptor expression during critical illness. Eur J Clin Invest. 2019;49(4): e13073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vassiliou AG, Stamogiannos G, Jahaj E, Botoula E, Floros G, Vassiliadi DA, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of glucocorticoid receptor alpha/beta expression and signalling, adrenocortical function and cytokines in critically ill steroid-free patients. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2020;501: 110656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Xie M, Yu Y, Tang Z, Hang C, Li C. Leukocyte glucocorticoid receptor expression and related transcriptomic gene signatures during early sepsis. Clin Immunol. 2021;223: 108660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sigal GA, Maria DA, Katayama ML, Wajchenberg BL, Brentani MM. Glucocorticoid receptors in mononuclear cells of patients with sepsis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25(2):245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goecke A, Guerrero J. Glucocorticoid receptor beta in acute and chronic inflammatory conditions: clinical implications. Immunobiology. 2006;211(1–2):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivers C, Levy A, Hancock J, Lightman S, Norman M. Insertion of an amino acid in the DNA-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor as a result of alternative splicing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(11):4283–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beger C, Gerdes K, Lauten M, Tissing WJ, Fernandez-Munoz I, Schrappe M, et al. Expression and structural analysis of glucocorticoid receptor isoform gamma in human leukaemia cells using an isoform-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction approach. Br J Haematol. 2003;122(2):245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang Y, Song MM, Liu SY, Ma LL. Relationship between expression of glucocorticoid receptor isoforms and glucocorticoid resistance in immune thrombocytopenia. Hematology. 2016;21(7):440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taniguchi Y, Iwasaki Y, Tsugita M, Nishiyama M, Taguchi T, Okazaki M, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor-beta and receptor-gamma exert dominant negative effect on gene repression but not on gene induction. Endocrinology. 2010;151(7):3204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krett NL, Pillay S, Moalli PA, Greipp PR, Rosen ST. A variant glucocorticoid receptor messenger RNA is expressed in multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Res. 1995;55(13):2727–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moalli PA, Pillay S, Krett NL, Rosen ST. Alternatively spliced glucocorticoid receptor messenger RNAs in glucocorticoid-resistant human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 1993;53(17):3877–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moalli PA, Pillay S, Weiner D, Leikin R, Rosen ST. A mechanism of resistance to glucocorticoids in multiple myeloma: transient expression of a truncated glucocorticoid receptor mRNA. Blood. 1992;79(1):213–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Lange P, Segeren CM, Koper JW, Wiemer E, Sonneveld P, Brinkmann AO, et al. Expression in hematological malignancies of a glucocorticoid receptor splice variant that augments glucocorticoid receptor-mediated effects in transfected cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(10):3937–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abraham SM, Clark AR. Dual-specificity phosphatase 1: a critical regulator of innate immune responses. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 6):1018–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abraham SM, Lawrence T, Kleiman A, Warden P, Medghalchi M, Tuckermann J, et al. Antiinflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of dual specificity phosphatase 1. J Exp Med. 2006;203(8):1883–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horita H, Wada K, Rivas MV, Hara E, Jarvis ED. The dusp1 immediate early gene is regulated by natural stimuli predominantly in sensory input neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(14):2873–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammer M, Mages J, Dietrich H, Schmitz F, Striebel F, Murray PJ, et al. Control of dual-specificity phosphatase-1 expression in activated macrophages by IL-10. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(10):2991–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smallie T, Ross EA, Ammit AJ, Cunliffe HE, Tang T, Rosner DR, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 1 and tristetraprolin cooperate to regulate macrophage responses to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2015;195(1):277–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lang R, Raffi FAM. Dual-specificity phosphatases in immunity and infection: an update. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11):2710. 10.3390/ijms20112710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoppstädter J, Ammit AJ. Role of dual-specificity phosphatase 1 in glucocorticoid-driven anti-inflammatory responses. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.le Roux CW, Chapman GA, Kong WM, Dhillo WS, Jones J, Alaghband-Zadeh J. Free cortisol index is better than serum total cortisol in determining hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal status in patients undergoing surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2045–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vassiliadi DA, Ilias I, Tzanela M, Nikitas N, Theodorakopoulou M, Kopterides P, et al. Interstitial cortisol obtained by microdialysis in mechanically ventilated septic patients: correlations with total and free serum cortisol. J Crit Care. 2013;28(2):158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marik PE, Pastores SM, Annane D, Meduri GU, Sprung CL, Arlt W, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critically ill adult patients: consensus statements from an international task force by the American college of critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1937–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.