Abstract

Background

It is suggested that in patients with coronary artery diseases (CAD) and stroke, the use of ticagrelor and aspirin may perform better than clopidogrel and aspirin regarding the risk of thrombosis/embolism, including recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death, especially in those carrying CYP2C19 loss-of-function (LOF) alleles. Therefore, we conducted the present systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of clopidogrel and ticagrelor in CAD and stroke patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles (poor metabolizers of clopidogrel).

Methods

We performed the current systematic review and meta-analysis by searching for all eligible publications on PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to November 2024. A search strategy employing three primary keywords in conjunction with their corresponding Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: “Ticagrelor” AND “Clopidogrel” AND “CYP2C19” (PROSPERO ID CRD420251050533). We implemented the odds ratio (OR) as an effect estimate for the dichotomous variables. The analysis was done at 95% confidence intervals (CI), and the p-value was significant if it was less than or equal to 0.05.

Results

Using clopidogrel was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis/embolism compared with ticagrelor, showing OR = 1.78 (95%CI, 1.08, 2.95; p = 0.02). Also, clopidogrel led to an increased risk of stroke, whether when used in stroke or CAD patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles, compared with ticagrelor, with an overall OR = 1.43 (95%CI, 1.23, 1.66; p < 0.00001) and a higher rate of MI with OR = 1.53 (95%CI, 1.22, 1.92; p = 0.0003). No significant difference was observed between the two groups (clopidogrel and ticagrelor) in stroke or CAD patients with OR = 0.98 (95%CI, 0.79, 1.22; p = 0.87). Also, no significant difference was observed between both groups regarding the risk of minor bleeding in stroke or CAD patients with OR = 0.66 (95%CI, 0.42, 1.05; p = 0.08) and any types of bleeding (major or minor bleeding) with overall OR = 0.81 (95%CI, 0.54, 1.21; p = 0.3) and I2 = 88%, p < 0.00001.

Conclusion

The meta-analysis of the selected articles indicated a preference for ticagrelor over clopidogrel in patients with stroke or CAD possessing CYP2C19 LOF alleles. The reduced incidence of thrombosis/embolism and associated events, such as stroke and MI, was noted in individuals administered ticagrelor in comparison to those receiving clopidogrel. Bleeding remains a concern with ticagrelor; however, current studies indicate its safety since there are no significant changes in the risk of minor and major bleeding and ICH compared to clopidogrel.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00228-025-03860-4.

Keywords: Ticagrelor, Clopidogrel, CYP2C19, Loss-of-function, Stroke, Coronary

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is among the most prevalent fatal conditions globally [1]. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has diminished mortality from ACS. However, numerous complications, such as ischemic events associated with drug-eluting stents (DESs) and bleeding issues, particularly at access sites, pose significant challenges [2]. Post-PCI antiplatelet therapy is a crucial treatment approach for ACS patients [1, 2]. Dual antiplatelet therapy utilizing aspirin and clopidogrel is the established protocol for preventing stent thrombosis and enhancing clinical outcomes during PCI [3].

In patients experiencing an acute mild ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), the likelihood of a subsequent stroke occurring within 3 months of the initial incident is between 5 and 10% [4–6]. Dual antiplatelet therapy utilizing clopidogrel and aspirin has demonstrated superior efficacy compared to aspirin monotherapy in mitigating subsequent events in patients with minor stroke or TIA, as evidenced by the CHANCE (clopidogrel in high-risk patients with acute nondisabling cerebrovascular events) [7] and POINT (platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke) trials [8].

Clopidogrel is a prodrug that necessitates conversion into its active metabolite by hepatic cytochrome P450, primarily CYP2C19. Platelet responses to clopidogrel exhibit significant interindividual variability. High on-treatment platelet reactivity (HTPR) refers to patients exhibiting an insufficient response to clopidogrel therapy. In other words, despite receiving the standard dose of clopidogrel, a subset of patients (reported as 4–30% in various studies) does not achieve adequate platelet inhibition. This inadequate response results in persistently high platelet activity, which increases the risk of adverse cardiovascular events such as stent restenosis, stent thrombosis, and even clinical death. This results from CYP2C19 loss-of-function (LOF) alleles in these individuals [9, 10]. Numerous independent clinical studies have shown that individuals with HTPR face a heightened risk of stent thrombosis and other cardiac problems [11, 12]. Therefore, there is a therapeutic necessity to evaluate the effectiveness of antiplatelet medication and implement more potent ADP-receptor antagonists.

Ticagrelor, a reversible oral antagonist that directly inhibits the platelet P2Y12 receptor and does not necessitate metabolic activation for its antiplatelet activity, may produce comparable or superior levels of platelet aggregation inhibition compared to clopidogrel [13, 14]. Ticagrelor, in conjunction with aspirin, demonstrated superiority over aspirin monotherapy in decreasing the incidence of stroke or mortality in individuals with acute mild-to-moderate ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA [15]. In the PRINCE (platelet reactivity in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack) trial, patients with minor stroke or TIA receiving ticagrelor in conjunction with aspirin exhibited reduced platelet reactivity compared to those administered clopidogrel with aspirin, especially among carriers of the CYP2C19 LOF allele [16]. These results indicate that the combination of ticagrelor and aspirin may confer a reduced risk of subsequent stroke compared to the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients with mild stroke or TIA who possess CYP2C19 LOF alleles. Also, this suggests that in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), the use of ticagrelor and aspirin may perform better than clopidogrel and aspirin regarding the risk of thrombosis/embolism, including recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death, especially in those carrying the CYP2C19 LOF allele. Despite its clinical efficacy, ticagrelor therapy has some limitations, such as an increased risk of non-procedure-related bleeding [14], major bleeding events [17], dyspnea [18], and patient adherence issues either due to its twice-daily dosing regimen or these side effects, particularly in fragile patients [19].

Earlier evidence already hints that clopidogrel is sub-optimal in patients who carry CYP2C19 LOF alleles, yet important knowledge gaps remain. Three meta-analyses confined to CAD cohorts reported that replacing clopidogrel with an alternative P2Y12 inhibitor (prasugrel or ticagrelor) lowered the composite risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) by roughly 40–50%, driven mainly by fewer myocardial infarctions and cardiovascular deaths [20–22]. A large registry study reached a similar conclusion in routine practice [23]. However, those reviews pooled prasugrel and ticagrelor together, did not analyze stroke populations, and presented only relative risk

estimates, which are difficult to translate into bedside decisions. A very recent meta-analysis limited to genotyped PCI patients confirmed a 62% higher MACE risk when LOF carriers stayed on clopidogrel, but it still grouped the two alternative drugs and excluded stroke [24].

To close these gaps, we conducted the present systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the efficacy and safety outcomes of clopidogrel and ticagrelor in CAD and stroke patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles and poor metabolizers of clopidogrel. We isolated ticagrelor (the agent most often recommended for switching), included both CAD and stroke cohorts of CYP2C19 LOF carriers, and calculated absolute measures such as the number needed to treat. To our knowledge, no previous analysis has combined all three of these elements.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards [25], searching for all eligible publications on PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to November 2024. According to each database, a search strategy employing three primary keywords in conjunction with their corresponding Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms—”Ticagrelor” AND “Clopidogrel” AND “CYP2C19″—was initiated. The protocol of the systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO with registration number CRD420251050533.

Eligibility criteria and screening

After the search, articles were imported into Rayyan to streamline the filtering process [26]. The initial screening was conducted independently by two pairs of authors (YA and YN and GB and IA), who reviewed titles, abstracts, and full-text articles to determine study eligibility. Any discrepancies were resolved by the senior author (MHEM). The study examined a group of patients with coronary artery disease or stroke who were poor metabolizers due to CYP2C19 LOF alleles, utilizing clopidogrel as the intervention and ticagrelor as the comparator while assessing various efficacy and safety outcomes: thrombosis/embolism, stroke, MI, minor or major bleeding, all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The design specifications emphasized observational studies (cohort and case–control) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) without imposing a restriction based on language (foreign language studies were translated by a professional translator) or sample size. We excluded case reports, reviews, and grey literature, such as unpublished theses, conference proceedings, government reports, white papers, and technical reports.

Data extraction

The baseline characteristics of the studies, including research design, gender, age, sample size, and population, were extracted by two pairs of authors (YA and YN and GB and IA) using Microsoft Excel sheets. Any discrepancies were resolved by the senior author (MaE). Outcome data were also collected, encompassing events of thrombosis/embolism, stroke, MI, minor or major bleeding, all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, ICH, and MACE.

Quality assessment

Two authors performed a risk of bias evaluation (MoE and MHEM), and any discrepancies were referred to the senior author (MA) for resolution. We employed various assessment instruments in alignment with the study design. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), which allocates a star value from 0 to 9 for each study, was employed to evaluate the quality of observational studies. All questions may be awarded one or zero stars, except for comparison questions, which may get a maximum of two stars. A study rated 0–3 stars is categorized as low quality; 4–6 stars signify intermediate quality, while 7–9 stars represent excellent quality [27]. We employed the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (Rob-2) for RCTs, comprising five areas, each accompanied by a series of inquiries. The results are subsequently incorporated into a visual representation to ascertain one of three levels of bias: low risk, moderate concern, or severe hazard. A study is deemed to possess a low overall risk of bias if all five domains demonstrate a low risk. The study has potential bias issues if any domain presents difficulties. If any domain shows a substantial risk of bias or numerous domains present problems, the study is classified as having a high risk of bias [28].

Statistical analysis

Review Manager software version 5.4 was used for the statistical analysis, including subgroup analysis [29]. We implemented the odds ratio (OR) as an effect estimate for the dichotomous variables. Heterogeneity was measured using I2, and it was deemed significant if the p-value was less than or equal to 0.05. The fixed effect model was used for non-significant heterogeneity, and the random effect model was used for significant heterogeneity among the included outcomes. We calculated the Number Needed to Treat [NNT = 1/Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR)] for significant outcomes. We performed sensitivity analyses to determine the robustness of the effect size by removing one study at a time to check the strength of the evidence and ensure the overall results were not altered. The analysis was done at 95% confidence intervals (CI), and the p-value was significant if it was less than or equal to 0.05. Finally, if at least ten studies were reported in the outcome, the asymmetry analysis was performed to determine the publication bias by visual inspection of the funnel plot of the studies, and Egger’s test confirmed the results [30].

Results

Literature searching and screening

The conducted search strategy yielded 619 (224 from PubMed, 212 from Scopus, and 183 from Web of Science) entries, of which 352 were classified as duplicates. After evaluating the titles and abstracts of the remaining 267 papers, 245 were excluded (108 of different designs, including case reports, reviews, and grey literature, such as unpublished theses, conference proceedings, government reports, white papers, and technical reports, and 137 irrelevant articles including different comparisons and different populations), and 22 satisfied the criteria for an exhaustive evaluation of the full text. In conclusion, 17 publications were deemed suitable for inclusion in the final systematic review [16, 31–46] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of searching and screening processes

Baseline characteristics

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, 11 cohort studies and six RCTs were included, which compared the use of clopidogrel against ticagrelor in patients with poor metabolism of clopidogrel due to CYP2C19 LOF alleles. These studies were conducted in CAD patients (13 studies), whether stable CAD or ACS, and patients with minor stroke or TIA. The mean (SD) age of patients ranged from 59.61 (9.58) to 72.44 (5.1) years old. Baseline characteristics of the included studies are fully illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies

| Study ID | Population | Design | Sample size, N | Age, mean (SD) | Male, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | |||

| Cavallari (2018) | CAD | Cohort | 1276 | 539 | 62.7 (11.7) | 62.5 (11.4) | 150 (67.5) | 237 (68.9) |

| Chen (2017) | CAD | Cohort | 46 | 57 | 59.61 (9.6) | 60.8 (9.2) | 29 (63) | 34 (59.6) |

| Dong (2016) | CAD | Cohort | 102 | 64 | 67 (12) | 67 (15) | 80 (78.4) | 52 (81.2) |

| Hu (2024) | CAD | Cohort | 240 | 60 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lee (2018) | CAD | Cohort | 1193† | 63.3 (12.0) | NR | NR | ||

| Lee (2021) | CAD | Cohort | 3342 | 64 (12) | 60 (11) | 308 (65) | 683 (73) | |

| Liu (2024) | Stroke | Cohort | 284 | 88 | 65.6 (9.3) | 67.2 (10.2) | 241 (85) | 71 (80) |

| Wallentin (2010) | CAD | RCT | 5137 | 5148 | 62.5 (11.0) | 62.5 (10.9) | NR | NR |

| Wang (2019) | Stroke | RCT | 339 | 336 | 60.5 (9.0) | 61.1 (8.5) | 249 (73.5) | 245 (72.9) |

| Wang (2021) | Stroke | RCT | 3207 | 3205 | 64.2 (10.5) | 64.3 (10.4) | 2127 (66.3) | 2115 (66) |

| Wang (2024) | CAD | Cohort | 243 | 302 | NR | NR | 78 (63.9) | 61 (80.3) |

| Xi (2020) | CAD | Cohort | 977 | 359 | 60.6 (9.7) | 58.3 (10.0) | 729 (74.6) | 281 (78.3) |

| Xiong (2015) | CAD | RCT | 112 | 112 | 67 (9) | 66 (8) | 71 (87) | 70 (86) |

| Yang (2020) | Stroke | RCT | 190 | 197 | 60 (9) | 61.3 (9) | 137 (72.1) | 140 (71) |

| Yu (2017) | CAD | Cohort | 724 | 247 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Zhang (2016) | CAD | RCT | 90 | 91 | 71.7 (9.2) | 68.8 (9.6) | 49 (54.4) | 42 (46.2) |

| Zhang (2024) | CAD | Cohort | 2056 | 695 | 72.4 (5.1) | 69.73 (3.42) | 1182 (57.5) | 442 (63.6) |

CAD coronary artery disease, RCT randomized controlled trial, NR not reported, SD standard deviation

†Among these, 233 patients were CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers (IM/PM); of these, 68 received clopidogrel, and 165 received ticagrelor or prasugrel

The most commonly used dose for clopidogrel was 75 mg once daily, except for one study, which was 150 mg once daily, while that of ticagrelor was 90 mg twice daily. The evaluation time of the outcomes or the follow-up period ranged from 1 to 12 months (most common) and 3 or 6 months in other studies. All the patients in the included studies had CYP2C19 with at least one LOF allele *2 or *3. Different treatments were used with the antiplatelets, including proton pump inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and statins. The patients in all the studies had comorbid conditions that increased the severity of the cases, such as previous stroke, myocardial infarction, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and dyslipidemia. Reasons for antiplatelets were the prevention of thrombosis after PCI or recurrent stroke after stroke or TIA. Types of CAD included ACS, such as ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and angina, in addition to stable CAD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics of the included studies

| Study ID | Dose | Time of evaluation of outcomes | CYP2C19 alleles | Co-treatment | Severity of the disease | Reason for antiplatelet | Type of CAD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | Clopidogrel | Ticagrelor | |

| Cavallari (2018) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | Aspirin, PPI, Statins, ARB, ACEi, B-blocker, Anticoagulants | Comorbidities include atrial fibrillation, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke | After PCI | STEMI, NSTEMI, UA, stable CAD | ||||||

| Chen (2017) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | At least 1 CYP2C19*2 | Aspirin, PPI, ARB, ACEi, B-blocker, CCB | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia | After PCI | Not specified | ||||||

| Dong (2016) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 1 month | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | NR | NR | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia | After PCI | Acute coronary syndrome | |||||

| Hu (2024) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | NR | NR | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia | After PCI | Not specified | |||||

| Lee (2018) | NR | NR | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | Aspirin, ARB, ACEi, B-blocker, Anticoagulants | Comorbidities include atrial fibrillation, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke | After PCI | STEMI, NSTEMI, UA, stable CAD | ||||||

| Lee (2021) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | Aspirin, PPI, Statins, ARB, ACEi, B-blocker, Anticoagulants | Comorbidities include atrial fibrillation, heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke | After PCI | STEMI, NSTEMI, UA, stable CAD | ||||||

| Liu (2024) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 6 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | NR | NR | Comorbidities include intracranial arterial stenting, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, kidney insufficiency, pulmonary infections | Ischemic stroke patients with cerebral artery stenting | NA | |||||

| Wallentin (2010) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | PPI, statins, aspirin | Comorbidities include diabetes, smoking | Acute coronary syndrome with PCI or not | Acute coronary syndrome | ||||||

| Wang (2019) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | PPI, statins, aspirin | Comorbidities include atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke | For platelet reactivity in minor stroke or transient ischemic attack | NA | ||||||

| Wang (2021) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | Aspirin | Comorbidities include myocardial infarction, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke | Secondary prevention of stroke after stroke or transient ischemic attack | NA | ||||||

| Wang (2024) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | PPI, statins, aspirin | Comorbidities include acute coronary syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke | After off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting | Not specified | ||||||

| Xi (2020) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | Two CYP2C19 LOF Alleles | Aspirin | Comorbidities include atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, myocardial infarction | After PCI | STEMI, NSTEMI, UA, stable CAD | ||||||

| Xiong (2015) | 150 mg daily | 90 mg twice daily | 1 month | CYP2C19*2 homozygotes† | Aspirin | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia | Acute coronary syndrome | Acute coronary syndrome | ||||||

| Yang (2020) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 3 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | PPI, statins, aspirin | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic stroke, coronary artery disease | For platelet reactivity in minor stroke or transient ischemic attack | NA | ||||||

| Yu (2017) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | Aspirin, PPI, Statins, ARB, ACEi, B-blocker, CCB | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, cerebral infarction | After PCI | Not specified | ||||||

| Zhang (2016) | 75 mg once daily | 90 mg twice daily | 6 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | PPI, statins, aspirin | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia | After PCI | Acute coronary syndrome | ||||||

| Zhang (2024) | NR | NR | 12 months | CYP2C19 with at least 1 of LOF alleles *2 or *3 | Aspirin, PPI, Statins, ARB, ACEi, B-blocker, CCB, Diuretics | Comorbidities include diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, myocardial infarction | After PCI | Acute coronary syndrome | ||||||

LOF loss of function, ACEi angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, PPI proton pump inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, CCB calcium channel blocker, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, STEMI ST-elevated myocardial infarction, NSTEMI non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction, UA unstable angina, CAD coronary artery disease, NA not applicable, NR not reported

†No deviation from the expected proportions of genotypes in the selected population predicted by the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for polymorphisms

Quality and risk of bias assessment

According to NOS, the 11 cohort studies were rated high quality, as shown in Table 3. Regarding RCTs, the Rob-2 used for risk of bias assessment showed that all the included RCTs were deemed to have a low risk of bias across all the domains (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Quality assessment of cohort studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale tool

| Study name | The level of representation of the affected cohort (★) | Identification of the unexposed cohort (★) | Determination of exposure (★) | Evidence that the outcome of interest was absent at the commencement of the research (★) | Comparison of cohorts based on design or assessment (max★★) | Was the follow-up duration sufficient for consequences to manifest? (★) | Evaluation of results (★) | Assessment of cohort follow-up sufficiency (★) | Quality level† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavallari (2018) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Chen (2017) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Dong (2016) | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Hu (2024) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | - | ★ | ★ | High |

| Lee (2018) | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Lee (2021) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Liu (2024) | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Wang (2024) | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★★ | - | ★ | ★ | High |

| Xi (2020) | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Yu (2017) | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

| Zhang (2024) | ★ | - | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | High |

†A study rated 0–3 stars is categorized as low quality; 4–6 stars signify intermediate quality, while 7–9 stars represent excellent quality

Meta-analysis

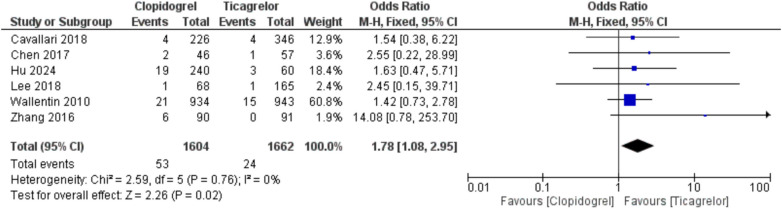

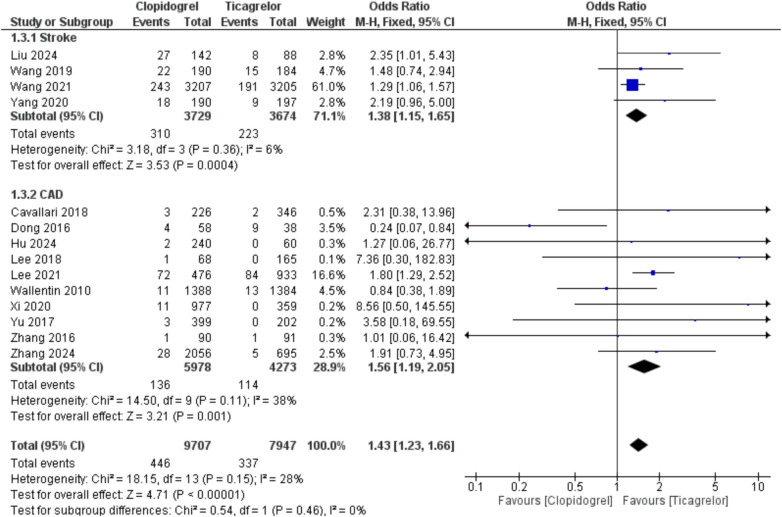

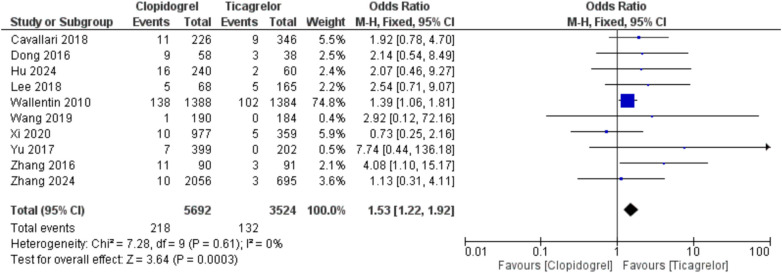

Using clopidogrel was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis/embolism compared with ticagrelor, showing OR = 1.78 (95%CI, 1.08, 2.95; p = 0.02) and I2 = 0% [AAR = 1%, NNT = 100, with uncertainty in 95% CI]. Also, clopidogrel led to an increased risk of stroke, whether when used in stroke or CAD patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles, compared with ticagrelor, with overall OR = 1.43 (95%CI, 1.23, 1.66; p < 0.00001) and I2 = 28%, p = 0.15 [AAR = 2%, NNT = 50]. Moreover, clopidogrel was associated with a higher rate of MI with OR = 1.53 (95%CI, 1.22, 1.92; p = 0.0003) and I2 = 0% [AAR = 2%, NNT = 50] (Fig. 2, 3, and 4). Therefore, ticagrelor is safer than clopidogrel in patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles in terms of the risk of thrombosis-related events. Regarding the risk of major bleeding, no significant difference was observed between the two groups (clopidogrel and ticagrelor) in stroke or CAD patients with OR = 0.98 (95%CI, 0.79, 1.22; p = 0.87) and I2 = 0% (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Comparison between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the risk of thrombosis/embolism among stroke or coronary artery disease patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele using odds ratio

Fig. 3.

Comparison between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the risk of stroke among stroke and coronary artery disease patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele using odds ratio

Fig. 4.

Comparison between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the risk of myocardial infarction among stroke and coronary artery disease patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele using odds ratio

Fig. 5.

Comparison between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the risk of major bleeding among stroke and coronary artery disease patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele using odds ratio

Also, no significant difference was observed between both groups regarding the risk of minor bleeding in stroke or CAD patients with OR = 0.66 (95%CI, 0.42, 1.05; p = 0.08) and I2 = 79%, p < 0.0001. Moreover, no significant differences were observed regarding any types of bleeding (major or minor bleeding) in stroke or CAD patients with overall OR = 0.81 (95%CI, 0.54; 1.21, p = 0.3) and I2 = 88%, p < 0.00001. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed between both groups regarding ICH in stroke patients with OR = 1.24 (95%CI, 0.56, 2.76; p = 0.59) and I2 = 0% (Supplementary Figs. 2–4).

Regarding the risk of mortality, no significant difference was observed between both groups regarding all-cause mortality and cardiac mortality, showing OR = 1.09 (95%CI, 0.76, 1.54; p = 0.65) and I2 = 0%, and OR = 1.1 (95%CI, 0.73, 1.64; p = 0.65) and I2 = 5%, p = 0.39 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Comparison between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the risk of all-cause mortality (top) and cardiac mortality (bottom) among stroke and coronary artery disease patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele using odds ratio

Clopidogrel showed an increased risk of occurrence of MACE compared with ticagrelor with OR = 1.98 (95%CI, 1.29, 3.04; p = 0.002) and I2 = 70%, p = 0.0009 [AAR = 7%, NNT = 14] (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Publication bias

Egger’s regression intercepts did not suggest significant small-study effects for stroke with intercept = 0.357 (95%CI, − 0.33, 1.07; p = 0.296), MI with intercept = 0.668 (95%CI, − 0.25, 1.58; p = 0.153), or major bleeding with intercept = 0.340 (95%CI, − 0.504, 1.89; p = 0.430). However, there was evidence of publication bias for any bleeding with intercept = 2.31 (95%CI, 1.32, 3.30; p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Discussion

Summary of findings

Among CYP2C19 LOF allele carriers with stroke or coronary artery disease, ticagrelor demonstrated superior efficacy to clopidogrel by significantly lowering thrombotic risks, namely thrombosis/embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction. Clopidogrel was associated with a 7% absolute increase in MACE risk with OR = 1.98 (95%CI, 1.29, 3.04; p = 0.002), corresponding to an NNT of 14 to prevent one additional event. Safety profiles were comparable: there were no significant differences in minor bleeding, major bleeding, or intracranial hemorrhage between the two agents. All-cause mortality also did not differ. These findings support using ticagrelor over clopidogrel in CYP2C19 LOF carriers, underscoring the value of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy.

Interpretation of findings

Antiplatelet medication is consistently administered to individuals following a mild stroke or TIA to avert stroke recurrence and other thrombotic incidents. The prognosis of small stroke or TIA is highly diverse and is affected by the presence and intensity of prognostic variables. Extensive epidemiological and clinical investigations have revealed risk variables linked to adverse clinical outcomes in patients with stroke or TIA, including advanced age, tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and peripheral artery disease [47–51]. Moreover, these risk factors may affect the choice of antiplatelet medication. The POPular AGE study [52] demonstrated that in individuals aged 70 years or older with NSTEMI, clopidogrel was a preferable alternative to ticagrelor. A meta-analysis of randomized studies [53] indicated that among smokers, individuals treated with clopidogrel experienced superior therapeutic benefits in mitigating cardiovascular events compared to those administered ticagrelor. The PLATO trial [14] showed that in patients with ACS, with or without ST-segment elevation, ticagrelor significantly decreased the occurrence of cardiovascular death compared to clopidogrel. The Clopidogrel vs. Aspirin in individuals at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) research [54] indicated that the absolute advantage of clopidogrel over aspirin for subsequent combined vascular events was enhanced in individuals with a history of diabetes or ischemic events.

Ticagrelor may serve as a clinically beneficial alternative antiplatelet agent for stroke patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles, in whom clopidogrel’s efficacy may be diminished [55], particularly within East Asian populations where both stroke recurrence and the prevalence of CYP2C19 LOF alleles are elevated [56]. Nonetheless, the clinical utility of pharmacogenomics-informed antiplatelet medication selection is constrained by the accessibility of quick CYP2C19 genotyping methodologies and toolkits, and the cost-effectiveness of a genotype-guided approach requires more examination. Nonetheless, disagreement exists concerning the safety of ticagrelor and its effects on long-term prognosis. The application of ticagrelor in clinical practice is often limited by several variables, including adverse medication reactions (such as dyspnea, ventricular pauses of > 3 s, and increased blood creatinine and uric acid levels), advanced age, impaired liver and kidney function, and patient non-compliance [57]. Most patients preferred a combination of clopidogrel and aspirin for antiplatelet treatment.

It was indicated [58] that CYP2C19 genetic testing could assist patients undergoing PCI in selecting the most effective antiplatelet therapy, perhaps decreasing the incidence of MACE. Additionally, post hoc analysis of the CHANCE study [59] indicated that the efficacy of clopidogrel in Chinese patients with mild stroke or TIA was contingent upon both CYP2C19 genotype and risk profile. CYP2C19 LOF carriers do not derive advantages from dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin; nevertheless, high-risk LOF carriers experience substantial benefits.

Current guidelines advocate for the administration of a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor in conjunction with aspirin as the foundational treatment for ACS patients post-PCI, significantly reducing ischemic episodes in individuals with DESs [60]. The PLATO research [14] indicated that ticagrelor therapy significantly decreased thrombotic events, such as vascular mortality, MI, and stroke, in patients with ACS without elevating severe bleeding rates compared to clopidogrel. Consequently, current guidelines promote ticagrelor over clopidogrel. The validity of ticagrelor therapy benefits for various populations of ACS patients post-PCI remains contentious. An observational trial conducted in Sweden indicated that ticagrelor therapy was not superior to clopidogrel in unselected ACS patients following PCI, exhibiting heightened bleeding risks and similar ischemic events [61]. The variance observed in the PLATO trial was attributed to the distinct characteristics of the recruited patients, which included a higher percentage of PCI, an increased number of elderly individuals, and perhaps diminished compliance with ticagrelor in real-world scenarios [61]. East Asian populations have relative resistance to ischemic events but increased susceptibility to bleeding hazards compared to Caucasian populations [62]. Numerous studies have concentrated on the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor therapy in East Asian patients. The TICAKOREA study, focusing on East Asian/Korean ACS patients, showed that standard-dose ticagrelor was associated with heightened clinically significant bleeding without advantages in decreasing ischemic episodes compared to clopidogrel [63]. The TALOS-AMI RCT [64] demonstrated that unguided de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy from ticagrelor to clopidogrel diminished bleeding risks while maintaining equivalent ischemic events in stable MI patients in Korea. An additional observational study [65] examining Chinese ACS patients following PCI indicated that ticagrelor elevated BARC Type 2 bleeding compared to clopidogrel. The POPular Genetics trial [66] revealed that a CYP2C19 genotype-guided approach for P2Y12 receptor inhibitors (CYP2C19 LOF carriers received ticagrelor or prasugrel, while noncarriers received clopidogrel) resulted in diminished bleeding risks without an elevation in thrombotic events compared to the ticagrelor or prasugrel treatment group. The TAILOR-PCI trial [67] showed that ticagrelor treatment did not significantly alter the rates of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis, or severe recurrent ischemia in CYP2C19 LOF carriers with ACS and stable CAD compared to standard clopidogrel therapy. However, its recent prespecified investigation indicated that ticagrelor medication markedly diminished cumulative ischemic events without elevating bleeding at 12 months post-PCI compared to clopidogrel treatment in CYP2C19 LOF carriers [68]. Parcha et al. [69] conducted a Bayesian reanalysis of the TAILOR-PCI trial, revealing a 99.9% posterior probability that the risk ratio for MACE is less than 1 in patients receiving genotype-guided P2Y12 inhibitor therapy post-PCI, utilizing informative priors from four prior clinical trials. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Galli et al. [58] demonstrated that the guided selection of antiplatelet therapy through platelet function or genetic testing in patients undergoing PCI enhanced efficacy outcomes, including MACE and specific endpoints, while significantly reducing minor bleeding. Consequently, customized antiplatelet medication that incorporates genetic and platelet function testing, alongside clinical features and procedural variables of patients, may provide a potential strategy to enhance safety and efficacy outcomes in individuals following PCI.

In addition to the CYP2C19 genotype, additional genetic variants, such as ABCB1, which encodes the P-glycoprotein efflux transporter and influences clopidogrel absorption, may affect the response to clopidogrel medication [70], although contradictory findings have been reported [71]. Consequently, integrating data from diverse genetic variants may enhance the customization of antiplatelet therapies for specific individuals. The potential impact of variant alleles of ABCB1 on ticagrelor responsiveness is still debated and requires additional investigation [32, 72]. Additional factors, including clinical comorbidities, medication adherence, and coronary anatomical and procedural characteristics, are also linked to ischemia and bleeding events in ACS patients receiving PCI. The aging process correlates with diminished cytochrome P450 levels and renal function, alongside increased comorbidities, resulting in more intricate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics than those of younger individuals [73, 74]. Zhang et al. [43] suggested that clopidogrel may be more suitable for elderly ACS patients with CYP2C19 LOF mutations undergoing PCI than ticagrelor due to fewer clinically significant bleeding events and similar ischemic risks. The customized selection of P2Y12 receptor inhibitors requires the incorporation of CYP2C19 genotypes, platelet function assessments, and clinical risk factors to enhance results for older patients with elevated bleeding and ischemic risks post-PCI. Integrating additional genetic polymorphism assessments, such as ABCB1, may improve the efficacy and safety of antiplatelet medication in the future; however, further clinical data is required.

Clinical implications

U.S. and European regulators have formally recognized the impact of CYP2C19 LOF alleles on clopidogrel efficacy. The FDA’s 2022 label for Plavix carries a Boxed Warning stating that “genetic variations in CYP2C19 can impair conversion of clopidogrel to its active metabolite,” and that “tests are available to identify individuals who are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers; consider the use of an alternative P2Y₁₂ inhibitor in these patients” [75]. Likewise, the EMA’s summaries of product characteristics for clopidogrel note under “Pharmacogenetics” that “in poor CYP2C19 metabolizers, clopidogrel at recommended doses forms less active metabolite and has reduced antiplatelet effect.”

Recent guidance from the American Heart Association (AHA), as outlined by Pereira et al. [76], reinforces the clinical significance of CYP2C19 genetic testing in patients receiving oral P2Y12 inhibitors, especially clopidogrel. The statement emphasizes that patients with CYP2C19 LOF alleles treated with clopidogrel are at increased risk for adverse ischemic outcomes and recommends genotype-guided therapy, preferably using ticagrelor or prasugrel in LOF carriers. Pereira et al. [76] also highlighted implementation barriers to routine genetic testing, such as result turnaround time, clinician education, cost-effectiveness, and integration with electronic health records. Addressing these issues is crucial for translating evidence into widespread practice. They advocate for either rapid or preemptive testing to facilitate timely decision-making, which could significantly improve outcomes in patients undergoing PCI or with ACS.

Routine CYP2C19 genotyping is now practicable in many clinical settings. On-site point-of-care assays such as the Spartan RX device yield a median of 2 h (range, 0.5–13.5 h) post-sample, enabling same-day therapeutic decisions [77]. Cost analyses in a community-pharmacy setting estimate net genotyping costs of approximately €43 per patient, which may be offset by reduced adverse events and medication optimization [78]. The RAPID-GENE trial further demonstrated that bedside genotyping of CYP2C19*2 carriers can be completed within 1 h, guiding prasugrel therapy to lower on-treatment platelet reactivity effectively [78]. In light of these data, and consistent with CPIC and AHA/ESC consensus statements advocating genotype-guided P2Y₁₂ inhibitor selection [76], we recommend the following:

For CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers, prescribe prasugrel or ticagrelor to mitigate thrombotic risk.

For extensive or rapid metabolizers, clopidogrel remains a safe, cost-effective option.

It is also important to highlight that adherence was not systematically assessed in the included studies, so we cannot directly account for it in our meta-analysis. In controlled trials such as PLATO [14], treatment discontinuation rates at 12 months were similar for ticagrelor (≈21%) and clopidogrel (≈24%). However, real-world data indicate that twice-daily regimens generally achieve 10–20% lower adherence than once-daily dosing [79–81]. Therefore, in routine practice, poorer adherence to ticagrelor’s twice-daily schedule could attenuate its effectiveness relative to clopidogrel and may have influenced the observed outcomes [19].

Limitations

Among the limitations of this meta-analysis is the predominance of observational studies, which inherently introduce bias. Key factors remain inadequately addressed in the literature, including variability in CYP2C19 allele definitions, clopidogrel dosing strategies, and the cost-effectiveness of genotyping. Most outcomes were reported at approximately 12 months, with only a handful at 1, 3, or 6 months, precluding subgroup analyses by follow-up interval or other study characteristics (Table 2). We could only conduct indication-specific analyses for stroke versus CAD, where outcome definitions overlapped.

Additionally, although stratification by heterozygous versus homozygous CYP2C19 LOF carriers would be ideal, only two of the 17 included studies (Xiong 2015 [*2 homozygotes only] and Xi 2020 [two LOF alleles]) provided genotype-specific outcomes. No trial reported outcomes for heterozygotes alone. Consequently, we were unable to conduct subgroup meta-analyses by genotype.

Finally, despite sensitivity analyses, heterogeneity remained high for MACE (I2 = 70%), minor bleeding (I2 = 79%), and any bleeding (I2 = 88%). This reflects irreducible study-level differences: follow-up ranged from 1 to 3 months (e.g., Dong 2016; Xiong 2015; Yang 2020) to 12 months in most trials; antiplatelet dosing was largely uniform (clopidogrel 75 mg vs. ticagrelor 90 mg BID), aside from Xiong (2015) (clopidogrel 150 mg) and two studies lacking dose data; CYP2C19 definitions varied from “ ≥ 1 LOF allele” to “two LOF alleles” or *2 homozygotes; concomitant therapies (aspirin, PPIs, statins) were inconsistently reported; and patient cohorts mixed post-PCI/ACS and cerebrovascular populations. Moreover, Egger’s test detected small-study effects for any bleeding (intercept = 2.31; 95% CI, 1.32–3.30; p < 0.001), suggesting publication bias. Consequently, results should be interpreted cautiously, especially those with high heterogeneity or bias risk.

Conclusion

Among CYP2C19 LOF allele carriers with stroke or coronary artery disease, ticagrelor consistently outperformed clopidogrel—reducing thrombosis/embolism, stroke, and MI without increasing minor or major bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, or mortality—and clopidogrel users faced a 7% higher MACE rate (NNT = 14). To build on these findings, future studies should employ prospective, genotype-guided randomized designs with harmonized allele panels and dosing regimens; systematically monitor adherence; extend follow-up; distinguish ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke outcomes; conduct cost-effectiveness analyses of point-of-care genotyping; and include diverse, real-world populations to enhance generalizability.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Mohamed Abouzid is a participant of STER Internationalization of Doctoral Schools Program from NAWA Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange No. PPI/STE/2020/1/00014/DEC/02.

Author contribution

MaE, MHEM, and MoE: conceptualization and methodology. YA, YN, GB, and IA: investigation and data curation. MHEM: formal analysis. MaE, MHEM, and MoE: Writing—Original Draft. RMW: Supervision. MHEM: Project administration. MA: Writing—Review & Editing. All authors read and approved the final content.

Data Availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mahmoud Elsayed, Mostafa Hossam El Din Moawad and Mohammed Elkholy contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Han Y, Li Y (2022) Adherence to P2Y12 inhibitors in acute coronary syndrome after a percutaneous coronary intervention: what can we improve? Eur Heart J 43(24):2314–2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL et al (2021) 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 42(14):1289–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA et al (2016) 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 68(10):1082–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, Albers GW, Bornstein NM, Canhão P et al (2016) One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med 374(16):1533–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahjouei S, Sadighi A, Chaudhary D, Li J, Abedi V, Holland N et al (2021) A 5-decade analysis of incidence trends of ischemic stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 78(1):77–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Y, Elm JJ, Li H, Easton JD, Wang Y, Farrant M et al (2019) Outcomes associated with clopidogrel-aspirin use in minor stroke or transient ischemic attack: a pooled analysis of clopidogrel in high-risk patients with acute non-disabling cerebrovascular events (CHANCE) and platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trials. JAMA Neurol 76(12):1466–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C et al (2013) Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 369(1):11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Conwit RA, Elm JJ et al (2018) Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med 379(3):215–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mejin M, Tiong WN, Lai LY, Tiong LL, Bujang AM, Hwang SS et al (2013) CYP2C19 genotypes and their impact on clopidogrel responsiveness in percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Clin Pharm 35(4):621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi X, Lin J, Zhou Q, Wu L, Cheng W, Wang C (2016) Clopidogrel resistance increases rate of recurrent stroke and other vascular events in Chinese population. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 25(5):1222–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buonamici P, Marcucci R, Migliorini A, Gensini GF, Santini A, Paniccia R et al (2007) Impact of platelet reactivity after clopidogrel administration on drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 49(24):2312–2317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sibbing D, Braun S, Morath T, Mehilli J, Vogt W, Schömig A et al (2009) Platelet reactivity after clopidogrel treatment assessed with point-of-care analysis and early drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 53(10):849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storey RF, Husted S, Harrington RA, Heptinstall S, Wilcox RG, Peters G et al (2007) Inhibition of platelet aggregation by AZD6140, a reversible oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 50(19):1852–1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C et al (2009) Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 361(11):1045–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR, Himmelmann A, James S et al (2020) Ticagrelor and aspirin or aspirin alone in acute ischemic stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med 383(3):207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Chen W, Lin Y, Meng X, Chen G, Wang Z et al (2019) Ticagrelor plus aspirin versus clopidogrel plus aspirin for platelet reactivity in patients with minor stroke or transient ischaemic attack: open label, blinded endpoint, randomised controlled phase II trial. BMJ 365:l2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, Steg PG, Storey RF, Jensen EC et al (2015) Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 372(19):1791–1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storey RF, Becker RC, Harrington RA, Husted S, James SK, Cools F et al (2011) Characterization of dyspnoea in PLATO study patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel and its association with clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J 32(23):2945–2953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiocca L, Rossini R, Carioli G, Carobbio A, Piazza I, Collaku E, et al. (2022) Adherence of ticagrelor in real world patients with acute coronary syndrome: the AD-HOC study. IJC heart & vasculature. 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Biswas M, Kali MSK, Biswas TK, Ibrahim B (2020) Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events ofCYP2C19loss-of-function genotype guided prasugrel/ticagrelor vs clopidogrel therapy for acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. Platelets 32(5):591–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xy Sheng, Hj An, Yy He, Yf Ye, Jl Zhao, Li S (2022) High-dose clopidogrel versus ticagrelor in CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers after percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Pharm Therap 47(8):1112–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon HY, Lee N, Seong JM, Gwak HS (2020) Efficacy and safety of clopidogrel versus prasugrel and ticagrelor for coronary artery disease treatment in patients with CYP2C19 LoF alleles: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 86(8):1489–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira NL, Rihal C, Lennon R, Marcus G, Shrivastava S, Bell MR, et al. (2021) Effect of CYP2C19 genotype on ischemic outcomes during oral P2Y12 inhibitor therapy. JACC: Cardiovascular interventions 14(7):739–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Biswas M, Murad MA, Ershadian M, Kali MSK, Sukasem C (2025) Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in CYP2C19LoF genotype guided clopidogrel against alternative antiplatelets for CAD patients undergoing PCI: Meta‐analysis. Clinical and translational science. 18(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson N, Phillips M (2018) Rayyan for systematic reviews. J Electron Resour Librariansh 30(1):46–48 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells GA, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al. (2014) editors. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- 28.RoB 2: A revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials | Cochrane bias [Available from: https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Deeks JJ, Higgins JP (2010) Statistical algorithms in review manager 5. Statistical methods group of the Cochrane Collaboration. 1(11).

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 315(7109):629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Pang M, Wu Y, Zhuang K, Zhang H et al (2016) High-dose clopidogrel versus ticagrelor for treatment of acute coronary syndromes after percutaneous coronary intervention in CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers: a prospective, randomized, open-label, single-centre trial. Acta Cardiol 71(3):309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF, Armstrong M, Barratt BJ, Horrow J et al (2010) Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet 376(9749):1320–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CR, Thomas CD, Beitelshees AL, Tuteja S, Empey PE, Lee JC et al (2021) Impact of the CYP2C19*17 allele on outcomes in patients receiving genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Pharmacol Ther 109(3):705–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavallari LH, Lee CR, Beitelshees AL, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Duarte JD, Voora D et al (2018) Multisite investigation of outcomes with implementation of CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 11(2):181–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen S, Zhang Y, Wang L, Geng Y, Gu J, Hao Q et al (2017) Effects of dual-dose clopidogrel, clopidogrel combined with tongxinluo capsule, and ticagrelor on patients with coronary heart disease and CYP2C19*2 gene mutation after percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). Med Sci Monit 23:3824–3830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CR, Sriramoju VB, Cervantes A, Howell LA, Varunok N, Madan S et al (2018) Clinical outcomes and sustainability of using CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Genom Precis Med 11(4):e002069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong R, Liu W, Chen L, Kang T, Ning S, Li J (2015) A randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of doubling dose clopidogrel versus ticagrelor for the treatment of acute coronary syndrome in patients with CYP2C19*2 homozygotes. Int J Clin Exp Med 8(8):13310–13316 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y, Chen W, Pan Y, Yan H, Meng X, Liu L et al (2020) Ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel in inhibiting platelet reactivity in patients with minor stroke or TIA. Front Neurol 11:534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu D, Ma L, Zhou J, Li L, Yan W, Yu X (2020) Influence of CYP2C19 genotype on antiplatelet treatment outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary heart disease. Exp Ther Med 19(5):3411–3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong P, Yang X, Bian S (2016) Genetic polymorphism of CYP2C19 and inhibitory effects of ticagrelor and clopidogrel towards post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) platelet aggregation in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Med Sci Monit 22:4929–4936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xi Z, Zhou Y, Zhao Y, Liu X, Liang J, Chai M et al (2020) Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with two CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 34(2):179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu C, Liu M, Yang X, Luo T, Wang J, Li G (2024) The efficacy and safety of aspirin-ticagrelor vs. aspirin-clopidogrel in ischemic stroke patients with cerebral artery stenting. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 239:108229. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Zhang D, Li P, Qiu M, Liang Z, He J, Li Y et al (2024) Net clinical benefit of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor in elderly patients carrying CYP2C19 loss-of-function variants with acute coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis 390:117395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu CY, Wang YL, Fan ZX, Sun XP, Wang S, Liu Z (2024) Effect of cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) gene polymorphism and clopidogrel reactivity on long term prognosis of patients with coronary heart disease after PCI. J Geriatr Cardiol 21(1):90–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Meng X, Wang A, Xie X, Pan Y, Johnston SC et al (2021) Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in CYP2C19 loss-of-function carriers with stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med 385(27):2520–2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z, Ma R, Li X, Li X, Xu Q, Yao Y et al (2024) Clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and ticagrelor in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 110(6):3450–3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diener HC, Ringleb PA, Savi P (2005) Clopidogrel for the secondary prevention of stroke. Expert Opin Pharmacother 6(5):755–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weimar C, Diener HC, Alberts MJ, Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW et al (2009) The Essen stroke risk score predicts recurrent cardiovascular events: a validation within the reduction of atherothrombosis for continued health (REACH) registry. Stroke 40(2):350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weimar C, Goertler M, Röther J, Ringelstein EB, Darius H, Nabavi DG et al (2008) Predictive value of the Essen stroke risk score and ankle brachial index in acute ischaemic stroke patients from 85 German stroke units. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79(12):1339–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishkanian AA, McCullough-Hicks ME, Appelboom G, Piazza MA, Hwang BY, Bruce SS et al (2011) Improving patient selection for endovascular treatment of acute cerebral ischemia: a review of the literature and an external validation of the Houston IAT and THRIVE predictive scoring systems. Neurosurg Focus 30(6):E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alvarez-Sabín J, Molina CA, Montaner J, Arenillas JF, Huertas R, Ribo M et al (2003) Effects of admission hyperglycemia on stroke outcome in reperfused tissue plasminogen activator–treated patients. Stroke 34(5):1235–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gimbel M, Qaderdan K, Willemsen L, Hermanides R, Bergmeijer T, de Vrey E et al (2020) Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): the randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 395(10233):1374–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gagne JJ, Bykov K, Choudhry NK, Toomey TJ, Connolly JG, Avorn J (2013) Effect of smoking on comparative efficacy of antiplatelet agents: systematic review, meta-analysis, and indirect comparison. BMJ 347:f5307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ringleb PA, Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Topol EJ, Hacke W (2004) Benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin is amplified in patients with a history of ischemic events. Stroke 35(2):528–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, Li H, Johnston SC, Lin Y et al (2016) Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA 316(1):70–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan Y, Chen W, Xu Y, Yi X, Han Y, Yang Q et al (2017) Genetic polymorphisms and clopidogrel efficacy for acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 135(1):21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis EM, Knezevich JT, Teply RM (2013) Advances in antiplatelet technologies to improve cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: a review of ticagrelor. Clin Pharmacol 5:67–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galli M, Benenati S, Capodanno D, Franchi F, Rollini F, D’Amario D et al (2021) Guided versus standard antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 397(10283):1470–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang ZX, Chen LH, Xiong R, He YN, Zhang Z, Zeng J et al (2020) Essen stroke risk score predicts carotid atherosclerosis in Chinese community populations. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 13:2115–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brilakis ES, Patel VG, Banerjee S (2013) Medical management after coronary stent implantation: a review. JAMA 310(2):189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Völz S, Petursson P, Odenstedt J, Ioanes D, Haraldsson I, Angerås O et al (2020) Ticagrelor is not superior to clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing PCI: a report from swedish coronary angiography and angioplasty registry. J Am Heart Assoc 9(14):e015990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levine GN, Jeong YH, Goto S, Anderson JL, Huo Y, Mega JL et al (2014) Expert consensus document: World Heart Federation expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol 11(10):597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park DW, Kwon O, Jang JS, Yun SC, Park H, Kang DY et al (2019) Clinically significant bleeding with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Korean patients with acute coronary syndromes intended for invasive management: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation 140(23):1865–1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim CJ, Park MW, Kim MC, Choo EH, Hwang BH, Lee KY et al (2021) Unguided de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TALOS-AMI): an investigator-initiated, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet 398(10308):1305–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun Y, Li C, Zhang L, Yu T, Ye H, Yu B et al (2019) Clinical outcomes after ticagrelor and clopidogrel in Chinese post-stented patients. Atherosclerosis 290:52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Claassens DMF, Vos GJA, Bergmeijer TO, Hermanides RS et al (2019) A genotype-guided strategy for oral P2Y(12) inhibitors in primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 381(17):1621–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pereira NL, Farkouh ME, So D, Lennon R, Geller N, Mathew V et al (2020) Effect of genotype-guided oral P2Y12 inhibitor selection vs conventional clopidogrel therapy on ischemic outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the TAILOR-PCI randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324(8):761–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ingraham BS, Farkouh ME, Lennon RJ, So D, Goodman SG, Geller N et al (2023) Genetic-guided oral P2Y(12) inhibitor selection and cumulative ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 16(7):816–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parcha V, Heindl BF, Li P, Kalra R, Limdi NA, Pereira NL et al (2021) Genotype-guided P2Y(12) inhibitor therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention: a Bayesian analysis. Circ Genom Precis Med 14(6):e003353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Méneveau N et al (2009) Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 360(4):363–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang L, Chen Y, Jin Y, Qu F, Li J, Ma C et al (2013) Genetic determinants of high on-treatment platelet reactivity in clopidogrel treated Chinese patients. Thromb Res 132(1):81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teng R (2015) Ticagrelor: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic profile: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet 54(11):1125–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trenaman SC, Bowles SK, Andrew MK, Goralski K (2021) The role of sex, age and genetic polymorphisms of CYP enzymes on the pharmacokinetics of anticholinergic drugs. Pharmacol Res Perspect 9(3):e00775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klotz U (2009) Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Drug Metab Rev 41(2):67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clopidogrel therapy and CYP2C19 genotype. In: Pratt VM, Scott SA, Pirmohamed M, Esquivel B, Kattman BL, Malheiro AJ, editors. (2012) Medical genetics summaries. Bethesda (MD).

- 76.Pereira NL, Cresci S, Angiolillo DJ, Batchelor W, Capers Q, Cavallari LH et al (2024) CYP2C19 Genetic testing for oral P2Y12 inhibitor therapy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 150(6):e129–e150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bergmeijer TO, Vos GJA, Claassens DMF, Janssen PWA, Harms R, der Heide Rv et al 2018 Feasibility and implementation of CYP2C19 genotyping in patients using antiplatelet therapy. Pharmacogenomics 19(7):621–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Levens AD, den Haan MC, Jukema JW, Heringa M, van den Hout WB, Moes DJAR, et al. (2023) Feasibility of community pharmacist-initiated and point-of-care CYP2C19 genotype-guided de-escalatioN OF ORAL P2Y12 inhibitors. Genes. 14(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353(5):487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laliberté F, Bookhart BK, Nelson WW, Lefebvre P, Schein JR, Rondeau-Leclaire J et al (2013) Impact of once-daily versus twice-daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic medications among patients with venous thromboembolism. The patient: patient-centered outcomes research 6(3):213–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weeda ER, Coleman CI, McHorney CA, Crivera C, Schein JR, Sobieraj DM (2016) Impact of once- or twice-daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic cardiovascular disease medications: a meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol 216:104–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.