Abstract

Campylobacter is a major foodborne pathogen, commonly transmitted through poultry. The emergence of multidrug-resistant strains due to antibiotic overuse in poultry farming highlights the need for monitoring resistance patterns and exploring alternative control strategies, such as bacteriophage application. This study examined the antimicrobial resistance patterns in Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and Campylobacter coli (C. coli). Additionally, a novel lytic Campylobacter phage CC_R7 was isolated, characterized, and subjected to complete genomic analysis. The phage CC_R7 application was evaluated for biofilm removal under slaughterhouse conditions and as a biocontrol agent in chicken meat. The results showed that the resistance rate in C. coli was higher than in C. jejuni. The phage CC_R7 has a genome size of 180,566 bp, and no virulent gene was found. It has a broad host range, killing 60 % of C. coli and 27.2 % of C. jejuni tested strains with excellent adsorption, a short latent period of 40 min, and a high burst size of 119 virions. The phage remained stable across temperatures (4 °C–50 °C) and pH levels (4–10). Moreover, phage CC_R7 has the potential to inhibit biofilm formation and reduce Campylobacter contamination in chicken meat by 1.2 log/g. Therefore, Campylobacter phage CC_R7 has unique characteristics to combat multidrug-resistant Campylobacter strains and can be used as a feed additive for biocontrol in food.

Keywords: Bacteriophage, Campylobacter, Stability, Biofilm removal, Chicken meat

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

In China, antimicrobial resistance in C. coli and C. jejuni is increasing.

-

•

The Campylobacter phage CC_R7 is capable of lysing both C. coli and C. jejuni.

-

•

The Phage CC_R7 has significant genetic and biological potential to combat Campylobacter.

-

•

It effectively reduces biofilm formation and Campylobacter load in chicken meat.

1. Introduction

Campylobacter is a foodborne pathogen that causes campylobacteriosis. Domestic animals like sheep, goats, cattle, chickens, and pets are the main reservoirs of this bacterium (Sahin et al., 2017). The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies Campylobacter as a leading cause of diarrhea because of its resistance to multiple antibiotics (Olson et al., 2022). The Campylobacter genus consists of more than 20 species; however, Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and Campylobacter coli (C. coli) are the most common Campylobacter species that cause human gastrointestinal illnesses (Alam et al., 2006). Campylobacter is mainly transferred to humans by ingesting contaminated food, while poultry meat is the primary transmission source (50–80 %) (El-Saadony et al., 2023). Globally, Campylobacter infects 96 million people annually (Damtew et al., 2024), with the highest incidence reported in the Czech Republic (215 cases per 100,000 in 2019), followed by Australia (146.8 per 100,000 in 2016) and New Zealand (126.1 per 100,000 in 2019) (Liu et al., 2022). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that Campylobacter infection affects 1.5 million people annually in the United States (Al Hakeem et al., 2025). According to the European Union's One Health 2023 Zoonosis Report, campylobacteriosis was the leading cause of human zoonotic diseases, accounting for 148,181 cases, which represented over 58 % of all reported zoonotic diseases (Authority, E.F.S., Prevention, E.C.f.D., Control, 2024). In China, Campylobacter has been increasingly reported. A study conducted in Wenzhou between 2017 and 2019 showed a 10.5 % detection rate in diarrheal patients, the highest in 15 years (Zhang et al., 2020). A 2010 risk assessment estimated 118 cases per 100,000 people from poultry consumption. Recent outbreaks, including five foodborne incidents in schools in Wenzhou between 2021 and 2022, further highlight the growing threat of Campylobacter in China (Li et al., 2025). Recently, antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter has been increasing, threatening public health (Tang et al., 2021). It is reported that clinical isolates of Campylobacter from China exhibit strong resistance to various antibiotics, including quinolones and tetracycline (Gao et al., 2023).

Different methods, like adding organic acid to drinking water, cleaning the carcass, improving biosecurity, cleaning after slaughter, and reducing environmental exposure, have been researched to lower Campylobacter in the food supply. However, some of these methods are not very effective or are costly to implement (Umaraw et al., 2017). Recently, bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has focused on employing bacteriophages to manage multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria (Askoura et al., 2021). Bacteriophages are viruses that prey on bacteria, and the environmental richness of phages is exceptionally high, with an estimated total number of phages of approximately 1031 particles (Mushegian, 2020). Phages have many advantages over antimicrobials; they can kill specific pathogenic bacteria without disturbing the normal microflora and destroying bacterial biofilms, which play a vital role in bacterial virulence and persistence (Bolocan et al., 2019). In therapeutic applications, phages have been used to target and eradicate pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Schooley et al., 2017; Jault et al., 2019). In the food production sector, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved certain phage-based products as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS). The majority of approved phages targeting foodborne pathogens are aimed at Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) (FDA, 2019, 2022).

Campylobacter phages belong to the Myoviridae or Siphoviridae families (Javed et al., 2014). They have been divided into three groups according to the size of their genomes: group I, which is estimated to be 320 kb; group II, which is 180–190 kb; and group III, which is 130–140 kb (Sails et al., 1998). Group I Campylobacter phages haven't been studied much or used yet, but some group II phages, such as Campylobacter phage CP220, Campylobacter phage CPt10, and Campylobacter phage CP21, have been fully sequenced, while Campylobacter phage vB_CcoM-IBB_35 (IBB_35) is listed in GenBank with five different pieces (Timms et al., 2010; Carvalho et al., 2012; Hammerl et al., 2012). A notable characteristic of group II phages is their high propensity to infect C. jejuni and C. coli (Sails et al., 1998). The genome of Group II Campylobacter phages possesses genes encoding several components, including clamp loader, membrane proteins, T4-like tail proteins, transposases, and metabolic enzymes. Notably, they also harbor up to twelve proteins containing S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) domains, which are not found in group III phages (Hammerl et al., 2012). Furthermore, group II Campylobacter phages exhibited a certain degree of similarity to T4-type (Escherichia phage) phages at the protein level (Timms et al., 2010).

Studies have demonstrated that Campylobacter bacteriophages can effectively reduce Campylobacter on food items like broilers, chicken skin, and meat. However, limited data are available on the biological and genomic characterization of these phages, and so far, only one Campylobacter phage product (GRN 966) has been approved by the FDA (FDA, 2020; Ushanov et al., 2020). Therefore, to combat multidrug-resistant (MDR) Campylobacter in the food chain, a Campylobacter bacteriophage with a broad host range and well-characterized biological and genomic properties is needed to decrease the load of both C. coli and C. jejuni in food products and animals.

This study aimed to assess the antibiotic resistance profiles of C. coli and C. jejuni strains and to isolate a novel Campylobacter phage capable of combating MDR Campylobacter strains. The phage was thoroughly characterized, including its complete genomic sequence and lytic efficacy. Additionally, the application of phage for biofilm removal under slaughterhouse conditions and in chicken meat was tested to control Campylobacter contamination.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains isolation and antibiotic susceptibility test

A total of 120 strains of C. coli and 33 strains of C. jejuni were isolated from fecal samples collected at poultry farms in Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi Provinces of China from 2019 to 2022. Modified Skirrow agar (Hopebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to isolate Campylobacter (Butcher and Stintzi, 2017). Suspected Campylobacter colonies were grown in brucella broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD 21152 USA) and subjected to multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to confirm C. coli and C. jejuni (Denis et al., 1999). The Campylobacter isolates were grown on Columbia blood agar (Oxoid Ltd, Wade Road Basingstoke, Hants, RG24 8 PW, UK) supplemented with 5 % sheep blood (Hongquan Bio) at 42 °C under microaerobic conditions (5 % O2, 10 % CO2, and 85 % N2) for 24–48 h, then Campylobacter colony was grown in brucella broth and stored at −80 °C for further use. Nine antibiotics, including gentamycin (32 μg/mL), clindamycin (16 μg/mL), erythromycin (64 μg/mL), florfenicol (64 μg/mL), tetracycline (64 μg/mL), ciprofloxacin (64 μg/mL), azithromycin (64 μg/mL), nalidixic acid (64 μg/mL), and telithromycin (8 μg/mL), were tested to see how sensitive the isolated C. coli and C. jejuni strains. The antibiotic concentrations were chosen based on Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints for Campylobacter species. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by using the broth microdilution method according to CLSI (Azrad et al., 2018).

2.2. Bacteriophage isolation, purification, and propagation

A total of 48 fecal samples from poultry farms in Hubei province were collected and transported to the National Reference Laboratory of Veterinary Drug Residues, Huazhong Agricultural University. The Campylobacter phage was isolated as described previously with slight modifications (Gencay et al., 2016). Briefly, 3 g of a poultry feces sample was mixed in 10 mL SM buffer (Phygene, 50 mM Tris HCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 100 mM NaCl, gelatin 0.01 %, pH 7.5) and kept overnight in a shaker at 4 °C. Next, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane (Merck Millipore Ltd). The obtained filtrate was mixed with an equal amount of 2 × brucella broth for enrichment, and 100 μL of each Campylobacter isolate was added to the filtered sample (Supplementary File 1, Table S1). The sample was incubated at 42 °C overnight and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min; the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. In the next step, mixed 400 μL freshly cultured indicator strain C. coli (99-2) with 4 mL NZCYM broth (Sangon Biotech) containing 0.5 % agar (Biofroxx). Then, poured the mixture gently on the top of the NZCYM-agar (1.2 % agar) plate, and dried it. Subsequently, spot 10 μL of the enriched sample and incubated at 42 °C under microaerobic conditions for 24–48 h. The formation of plaques was observed. After confirming the inhibition zone, the single plaque was picked up using a 200 μL pipette tip and resuspended in a 500 μL SM buffer. Each single plaque was purified 3 times on an NZCYM double agar plate by plaque assay (Townsend et al., 2021). Phage was propagated by the complete lysate plate method, according to Bonilla et al. (2016). Phage titer was determined by plaque assay and stored at 4 °C for further experiments.

2.3. Phage purification by cesium chloride density gradient

For purification of phage, 100 mL phage lysate was centrifuged at 200,000×g for 2 h in Optima XPN-100 (Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 2 mL SM buffer. Next, the phage suspension was purified by cesium chloride (CsCl) density gradient (Tao et al., 2016). Phage band was collected and dialyzed in dialysis buffer I (10 mM Tris HCL 1.211g, 20 mM NaCl 11.7g, 50 mM Mgcl2 1.0165, water 1 L, pH 7.5) for 5 h and in dialysis buffer II (10 mM Tris HCL 1.211g, 20 mM NaCl 2.925g, 50 mM Mgcl2 1.0165, water 1 L, pH = 7.5) overnight. The purified phage was collected in a glass vial, and after measuring the titer, the phage was stored at −80 °C for further use.

2.4. Electron microscopic examination

A 10 μL cesium chloride-purified phage sample (∼109 PFU/mL) was absorbed on a copper grid and negatively stained with phosphotungstic acid (2 %, pH 7.0) for 15 s (Wang et al., 2020). After that, the phage morphology was examined by using transmission electron microscopy (HITACHI H-7650, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV.

2.5. Phage DNA extraction, sequencing, de novo assembly, and annotation

Phage DNA was extracted by using a commercially available phage DNA extraction kit (Norgen Biotek Corp. Phage DNA isolation kit), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The China National Gene Bank (CNGB) conducted genomic DNA library preparation and whole genome sequencing. Briefly, a 300 bp DNA fragment library was prepared using the MGIEasy DNA Library prep kit (V1.0) and sequenced using a sequencer (DNBSEQ-T7; MGITech, China). Subsequently, the raw reads obtained post-sequencing were inspected with FastQC v 0.12.1 (Andrews, 2010), revealing 3,456,734 read pairs with an average length of 150 bp. The reads were further processed with Fastp v 0.23.2 (Chen et al., 2018) with default settings for quality control, adapter trimming, and quality filtering. To simplify the de novo assembly process and avoid unnecessary complexities, the filtered raw reads were randomly sub-sampled using seqtk (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk) to ensure coverage of 100X (Rihtman et al., 2016). The sub-sampled reads were then de novo assembled using Unicycler v 0.5.0 (Wick et al., 2017), resulting in 2 contigs (151,711 bp and 28,016 bp). The gap between the 2 contigs was filled by PCR (Supplementary File 1, Table S2), resulting in a single contig. The obtained single contig was circularized by a closure PCR (https://cpt.tamu.edu/training-material/topics/de-novo-assembly/tutorials/genome-close-reopen/tutorial.html) (Supplementary File 1, Table S3), resulting in 180,566 bp, and re-opened starting from the terminase protein (Ye et al., 2006).

Further, DNA Master v5.23.6 (a freely available tool) was used for sequence analysis and annotation (Pope and Jacobs-Sera, 2018). Where Glimmer and GeneMark were used for Open reading frame (ORF) prediction (Besemer and Borodovsky, 2005; Delcher et al., 2007). Aragon and tRNA scan were used to predict tRNAs (Lowe and Eddy, 1997; Laslett and Canback, 2004). The putative functional assignment for each ORF was conducted by analyzing the corresponding amino acid sequence from the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI), conserved domain database (CDD), BLASTp, and HHpred using the default parameters (McGinnis and Madden, 2004; Söding et al., 2005; Marchler-Bauer et al., 2010). The whole genomic sequence of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 was submitted to GenBank, and the accession number PQ092953 was assigned.

2.6. Phage taxonomic classification and genome comparison

The major capsid protein and terminase protein of Campylobacter phage CC_R7, along with other similar protein sequences searched in BLASTp hits, were used for phylogenetic analysis. The ClustalW (Thompson et al., 2003) was used to build multiple sequence alignments (MSAs), which served as input for creating a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree in IQ-TREE v2.3.5 (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/). The tree was constructed with 1000 rapid bootstrap replications (Hoang et al., 2018). The genomic nucleotide sequence similarity of phage CC_R7 to other sequenced phages was determined using a heatmap generated with the VIRDIC tool (https://viridic.icbm.de). The comparative genomic analysis of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 with other Campylobacter phages (CP220, CP20, CP21), the BLASTn top hits, was conducted using BLASTn in Easyfig v.2.2.3 (Sullivan et al., 2011).

2.7. Phage adsorption and one-step growth curve

The phage adsorption assay was performed as previously described with slight modifications (Rattanachaikunsopon and Phumkhachorn, 2006). Briefly, phage lysate (2.62 × 107 PFU/mL) was infected with the host or indicator strain C. coli (99-2) at Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) 0.1 and incubated at 42 °C while shaking. The samples were taken at 5-min intervals up to 25 min, centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. Unabsorbed bacteriophage was determined by measuring the titer of the filtrate using the double agar plate method. For a one-step growth curve, 2 mL bacterial host solution containing 108 CFU/mL was mixed with a 2 mL bacteriophage suspension containing 108 PFU/mL. The mixture was then incubated at 42 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, the combination underwent centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The resulting pellet was then dissolved in 10 mL of preheated (42 °C) brucella broth and placed in an incubator at 42 °C. After this, 100 μL of the sample was taken every 10–120 min, and the titer was determined by plaque assay.

2.8. Host range, thermal, and pH stability

The host range was determined by spot assay (Akmal et al., 2023). A total of 56 Campylobacter isolates were checked (Supplementary File 1, Table S4). The stability of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 was assessed at different temperatures and pH levels. Briefly, phage suspension (107 PFU/mL) was incubated at various temperatures, including 4 °C, 30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C. After incubation, the phage titer was determined at 0 min, 30 min, and 60 min. Phage stability against different pH levels (2–12) was determined by preparing solutions at the respective pH with Tris–chloride. Phage lysate (107 PFU/mL) was added to different pH solutions and incubated at 37 °C. Samples were taken after 1 h, and the titer was determined by plaque assay.

2.9. Bacterial cell lytic assay (liquid medium)

To determine the bacterial cell lytic activity of phage in a liquid medium, the host C. coli (99-2) was grown in brucella broth at 42 °C for 24 h to attain 1 × 108 CFU/mL. Then, 100 μL of bacteria and 100 μL of phage were added to a 100-well Honeycomb sterile microplate for bioscreen (Oy Growth Curves Ab Ltd) to attain MOI 0.1, 0.001, and 0.0001. In positive control, 200 μL of bacteria was added, and a blank well was used as a negative control. The plate was placed in a fully automatic growth curve analyzer (Bioscreen C, Oy Growth Curves Ab Ltd) at 42 °C, 220 rpm, and the OD 600 value was measured at 0 min and after every 30 min up to 24 h.

2.10. Effect of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 on biofilm eradication

The biofilm assay was performed by mimicking slaughterhouse conditions as described previously with slight modifications (Araújo et al., 2022). Given that the slaughter process comprises varying ambient temperature conditions, the biofilm formation was evaluated at 10 °C and 42 °C under microaerobic conditions. Chicken juice was prepared by taking 1 kg of chicken meat and 500 mL sterile saline solution and placing them in a sterile bag. The carcass fluid was collected and centrifuged at 12000 g for 15 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter membrane. The host C. coli (99–2) was grown in brucella broth supplemented with 10 % chicken juice. 100 μL of phage suspension and 100 μL of host were mixed in a 96-well plate at MOI 100 and 10. In the control group, SM buffer was added, and plates were then incubated at 10 °C and 42 °C under microaerobic conditions. The crystal violet staining method was used to measure the formation of biofilm. Briefly, culture media were removed, and wells were washed 3 times with sterile Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After washing, methanol was added for 15 min, followed by air-drying. Stained with crystal violet (0.1 %) and 33 % glacial acetic acid was used for elution, with absorbance measured at OD value 595 nm (O'Toole, 2011).

2.11. Campylobacter phage CC_R7 application on chicken meat

Raw breast chicken meat was purchased from the supermarket in Wuhan, China. Chicken meat was sprayed with 70 % ethanol and washed with sterilized water for decontamination. The meat was cut into (2 cm × 2 cm) and put in UV light for 1 h on each side. Absence of Campylobacter was confirmed by homogenizing 1g of chicken in 10 mL PBS, and spreading 100 μL of this homogenate on a Columbia blood agar plate and observing the growth of Campylobacter colonies. After that, the meat surface was artificially contaminated with 100 μL of the host Campylobacter suspension (108 CFU/mL) and incubated at room temperature for 1h to allow the bacterial cells to attach to the meat surface. Next, 100 μL purified phage suspension (2 × 109 PFU/mL) was added to the surface of contaminated meat pieces and incubated at 4 °C. SM buffer was added to the control instead of the phage. After 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, the sample was withdrawn and homogenized with PBS, and the homogenate was 10-fold serially diluted with PBS for viable count.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22 (IBM, US). The infection dynamics tests were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software. A significance level of p < 0.05 was employed for all statistical analyses. Each experiment was repeated three times, and data represent Mean ± standard error (Mean ± SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility

153 Campylobacter isolates were included in this study. Of these, 120 (78.4 %) were C. coli and 33 (21.5 %) were C. jejuni (Table 1).

Table 1.

The prevalence of Campylobacter.

| Category | Isolates Count | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Samples | 1120 | |

| Total Campylobacter | 153 | 13.3 % |

| C. coli | 120 | 10.7 % |

| C. jejuni | 33 | 2.9 % |

C. coli: Campylobacter coli, C. jejuni: Campylobacter jejuni.

The antibiotic susceptibility test revealed that among the C. coli isolates, tetracycline has the highest rate of resistance (91.6 %), followed by nalidixic acid (90.8 %), ciprofloxacin (84.16 %), azithromycin (75.8 %), gentamycin (75 %), clarithromycin (65.8 %), erythromycin (38.3 %), telithromycin (29.1 %) and florfenicol (16.6 %). In contrast, ciprofloxacin (78.7 %) exhibited the highest resistance rate among the C. jejuni isolates. Nalidixic acid and tetracycline both had 75.75 % resistance compared to gentamycin (48.48 %), clarithromycin (27.27 %), azithromycin (10 %), erythromycin (6.1 %), and florfenicol (6.06 %). All C. jejuni isolates were sensitive to telithromycin. About 95 % (114/120) of C. coli and 85 % (28/33) of C. jejuni were multidrug-resistant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of C. coli and C. jejuni.

| Antibiotics |

C. coli (n = 120) Total (% resistance) |

C. jejuni (n = 33) Total (% resistance) |

|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 101 (84.16 %) | 26 (78.7 %) |

| Nalidixic Acid | 109 (90.8 %) | 25 (75.75 %) |

| Gentamycin | 90 (75 %) | 16 (48.48 %) |

| Tetracycline | 110 (91.6 %) | 25 (75.75 %) |

| Clarithromycin | 79 (65.8 %) | 9 (27.27 %) |

| Erythromycin | 46 (38.3 %) | 2 (6.1 %) |

| Azithromycin | 91 (75.8 %) | 3 (10 %) |

| Telithromycin | 35 (29.1 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Florfenicol | 20 (16.6 %) | 2 (6.06 %) |

| Multidrug-resistant | 114 (95 %) | 28 (85 %) |

C. coli: Campylobacter coli, C. jejuni: Campylobacter jejuni.

3.2. Phage isolation and morphology

A fecal sample collected from Hubei province confirmed the presence of lytic bacteriophage in a plaque assay. This Campylobacter phage, named CC_R7, showed a clear plaque morphology on a double agar plate measuring 1–2 mm (Fig. 1A). The transmission electron microscopic examination of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 (Fig. 1. B) revealed that it belongs to the Myoviridae family with an isometric head (diameter: 97.4 nm ± 5.66 nm) and a long contractile tail (length: 126.8 nm ± 3.2 nm).

Fig. 1.

Morphology of CC_R7. (A) Plaque morphology of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 on the double agar plate. (B) Transmission electron microscope image of Campylobacter phage CC_R7. The phage belongs to the Myoviridae family with an icosahedral head and a long contractile tail. The diameter of the head was about 97.4 nm (±5.66 nm), and the tail length was approximately 126.8 nm (±3.2 nm).

3.3. Genomic analysis of Campylobacter phage CC_R7

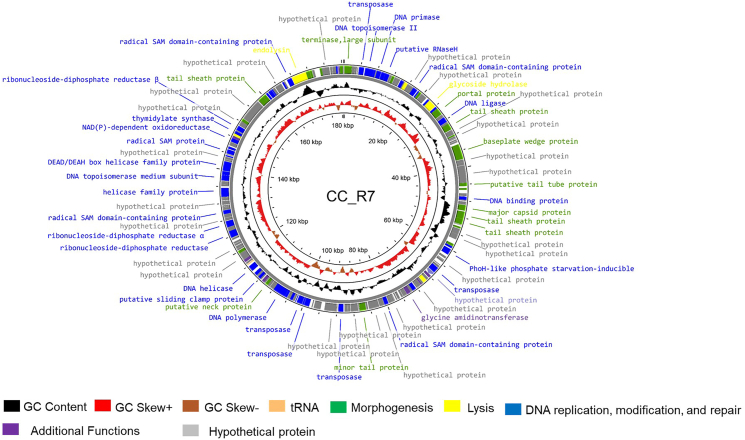

The genomic analysis of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 confirmed a double-stranded DNA linear genome of 180,566 bp with a GC content of 27.8 %. The BLASTn results of the Campylobacter phage CC_R7 (PQ092953) nucleotide sequence showed that it has the highest similarity with the Campylobacter group II phages CP220 (Total score: 2.153e+05, Query cover: 83 %, Identity: 93.84 %). DNA Master (v5.23.6) predicted 200 ORFs and 2 tRNAs in the genome, with a coding capacity of 87.06 %. Among the predicted ORFs, 164 were on the positive strand, and 36 were on the negative strand. Of 200 ORFs, 87 (43.5 %) were assigned putative functions, whereas 113 ORFs (56.5 %) were not subjected to functional annotation. The genome contains three possible start codons. 175 ORFs use ATG, 16 ORFs use TTG, and 9 ORFs use GTG as a starting codon. Furthermore, phage carries two neighbouring tRNA genes: tRNA-Ile (GAT), specific for isoleucine amino acid, and tRNA-Tyr (GTA), specialized for the amino acid tyrosine.

A thorough examination of the recognized roles of various ORFs (Fig. 2) indicated the existence of several functional modules in the Campylobacter phage CC_R7, including those specific for morphogenesis, DNA modification, replication and repair, lysis, additional functions, and hypothetical proteins (Supplementary File 2, Detailed ORF annotation).

Fig. 2.

Genomic map of Campylobacter phage CC_R7. The products produced by ORFs are colour-coded according to their expected functions. The green colour is used to represent products that are involved in morphogenesis. Yellow is used to describe proteins that are involved in lysis. Blue is used to represent enzymatic proteins that are involved in DNA replication, modification, and repair. Purple is used to represent proteins with additional functions. Grey is used to represent hypothetical proteins. This map was created using Proksee.

3.3.1. Morphogenesis proteins

The morphogenesis module commenced with the large terminase protein and proteins involved in forming various head structures, including the major capsid protein, putative head completion protein, DNA end protector, and prohead protein protease. The tail protein included minor tail protein, baseplate protein, portal protein, and five genes encoding tail sheath protein, three genes encoding baseplate wedge subunit, two genes encoding tail tube protein, major tail protein, neck protein, and baseplate tube cap.

3.3.2. Lysis proteins

The lysis proteins include glycoside hydrolase, polysaccharide deacetylase, UDP-glucose dehydrogenase, endolysin, a baseplate hub subunit, and a tail lysozyme, which is associated with the tail lysozyme and is responsible for the partial breakdown of the bacterial cell wall, allowing for phage DNA injection (Kanamaru et al., 2005).

3.3.3. DNA replication, modification, and repair

The phage genome harbors numerous enzymatic proteins that play crucial roles in DNA replication, modification, and repair. These include DNA polymerase, DNA topoisomerase II, DNA primase, DNA helicase, SSB, DNA binding protein, sliding clamp loader large subunit, clamp loader small unit, RNaseH, DEAD/DEAH box helicase family protein, and PD-(D/E)XK nuclease family protein. This indicates that the phage relies on its machinery for replication. In addition to this, like other Group II phages, CC_R7 contains nine transposase genes, suggesting a high potential for causing deletions or genomic rearrangements. Moreover, as other Group II phages have radical SAM proteins, CC_R7 also has five radical SAM proteins. The Radical SAM superfamily comprises a wide range of enzymes with a common core structural fold and utilizes S-adenosylmethionine to produce organic radicals. Radical SAM enzymes catalyze reactions, including oxidation, reduction, methylation, methylthiolation, sulfurylation, and complicated rearrangement reactions (Farrar and Jarrett, 2007). Additionally, the genome has a 7-carboxy-7-deazaguanine synthase enzyme that shields the phage DNA from being targeted by the host's restriction enzymes (Hutinet et al., 2019). Phage CC_R7 has a multitude of genes that are implicated in nucleotide metabolism. The former includes aerobic and anaerobic ribonucleotide-diphosphate reductase genes, ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase 1 subunit 1 ALPHA, ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase subunit beta, thymidylate kinase, thymidine kinase, GTP cyclohydrolase I, and PhoH-like starvation inducible. As Campylobacter is microaerophilic, it may be inferred that phage CC_R7 possesses a repertoire of enzymes for synthesizing nucleotides in aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

The hypothetical protein module and additional functions modules are present in the remaining genome. No genes linked with lysogenicity, virulence, drug resistance, integrase, and pathogenicity were discovered, showing that phage CC_R7 was genetically safe. (Supplementary File 1. Table S5 summarizes the comparative properties of phage CC_R7 with those of other Campylobacter group II phages).

The phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3) of CC_R7 based on major capsid protein (Fig. 3A), and terminase protein (Fig. 3B) placed it closer to Campylobacter group II Phages (CP21, CP220, CPt10, and CcoM-IBB 35), which belong to the genus Firehammervirus.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of CC_R7. (A) Neighbor-joining tree was constructed using the amino acid sequences of the major capsid protein (protein ID: XLL17448) and the (B) terminase large subunit (protein ID: XLL17397) of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 and similar protein sequences from other phages. The phylogenetic tree is accurately depicted, with branch lengths corresponding to the evolutionary distances utilized for its estimation. A bootstrap analysis was conducted using 1000 replicates. The terminal ends of branches are designated as "protein accession number followed by phage name." The evolutionary studies were performed using IQ-TREE v2.3.5.

Furthermore, nucleotide-based intergenomic similarities as calculated with VIRDIC showed its clustering with other phages from the genus Firehammervirus, with the highest similarity (79.3 %) with the phage Campylobacter phage CP220, and Campylobacter phage CJLB-14 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

VIRDIC analysis of CC_R7. A heat map compares the entire genome of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 with 13 additional members belonging to the Caudoviricetes group. The heat map (similarity-based) was created using the VIRIDIC service, with a species differentiation threshold set at 95 %.

The genomic comparison of Campylobacter phage CP220 (FN667788), Campylobacter phage CC_R7 (PQ092953), Campylobacter phage CP20 (MK408758), and Campylobacter phage CP21 (NC019507) by Easyfig (Fig. 5) revealed that these bacteriophages have greater symmetry and gene organization. The average nucleotide identity between CC_R7 and CP220 was calculated to be 91.71 %. Similarly, the average nucleotide identity between CC_R7 and CP20 was determined to be 91.34 %, and between CC_R7 and CP21, it was found to be 90.95 %.

Fig. 5.

Pairwise nucleotide sequence comparison of Campylobacter phage CP220 (FN667788), Campylobacter phage CC_R7 (PQ092953), Campylobacter phage CP20 (MK408758), and Campylobacter phage CP21 (NC019507) using tBLASTn. The genomes are represented proportionally, with the scale bar indicating a length of 5000 bp. Arrows are used to denote the direction of transcription for each ORF. The products produced by ORFs are categorized and color-coded according to their projected functions, following the provided legend. The grey boxes indicate areas of genomic similarity, with the color gradient reflecting their level of identity.

3.4. Phage adsorption assay and one-step growth curve

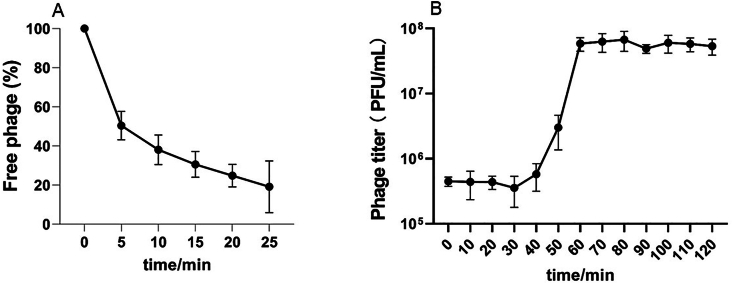

The Campylobacter phage CC_R7 was efficient in binding to its host Campylobacter strain. The decrease in free phage percentage in the supernatant after 5 and 10 min was about 50 % and 35 %, respectively, and continued to decrease until 25 min of incubation. The maximum adsorption was during the first 5 min, i.e., 50 % (Fig. 6A). The one-step growth curve experiment was performed to define the infection cycle of CC_R7, which showed that CC_R7 had a latent period of 40 ± 5 min and a burst size of roughly 119 ± 10 phages per infected cell (Fig. 6B). These findings strengthen the possibility that CC_R7 would be a helpful candidate for practical applications.

Fig. 6.

Adsorption assay and one-step growth curve. (A) Shows the rate at which Campylobacter phage CC_R7 adsorbs to its host. Phages were added to the bacterial suspension at an MOI of 0.1. The percentage of non-adsorbed/free phages was computed at the specified time points. The reported data are the average of three independent experiments, with error bars indicating the standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Single-step growth curve study. Plaque-forming units (PFU) were measured at different intervals after infection with C. coli (99-2). The latent period is 40 ± 5 min, and the burst size is 119 ± 10 phages per infected cell. The bars represent SEM.

3.5. Host range, thermal, and pH stability

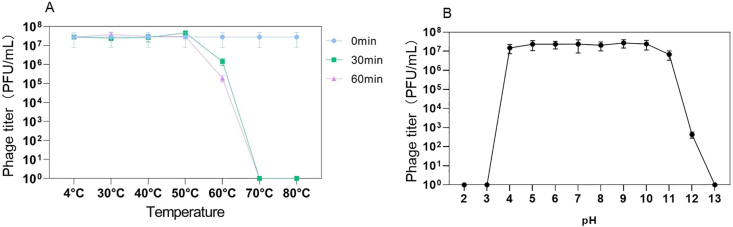

The host range analysis showed that phage CC_R7 lysed 60 % (21/34) C. coli and 27.3 % (6/22) C. jejuni. The strongest lytic spectrum was observed in C. coli isolates isolated from Hubei. The host range of phage CC_R7, with varying degrees of lytic activity across different geographical regions is described in Supplementary File 1, Table S4. The Campylobacter phage CC_R7 is relatively stable at 50 °C. There was no significant change in titer from temperature 4 °C–50 °C. At 60 °C after 30 and 60 min, the titer decreases by 1 log and 2 log, respectively. At 70 °C, the phage was not detectable after 30 or 60 min (Fig. 7A). The Campylobacter phage CC_R7 is stable in a wide pH range from 4 to 11. In a highly acidic environment at pH 3, all phage particles lost infectivity. Similarly, in the highly basic environment at pH 12, the phage titer decreased sharply, and at pH 13, all phages were dead (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Thermal and pH stability. (A) Effect of temperature on the stability of Campylobacter phage CC_R7. The experiments were conducted three times, and the phage concentrations were reported as the average ± standard deviation. (B) Effect of pH on the stability of Campylobacter phage CC_R7.

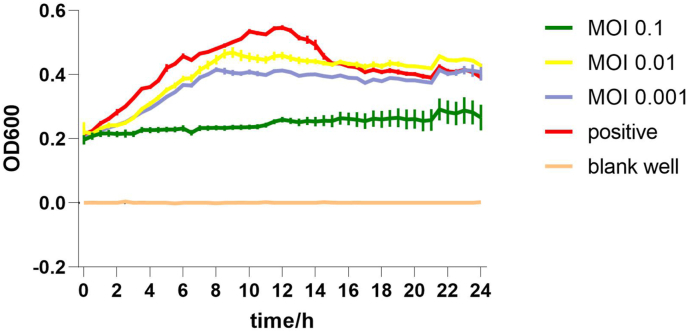

3.6. Bacterial cell lytic assay

The lytic activity of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 in a liquid medium against its host bacteria at different MOIs is shown in Fig. 8. The maximum activity against bacteria is shown at MOI 0.1. The OD 600 value of positive control (without phage) and phage-treated (MOI 0.1) after 12 h reached 0.5 and 0.22, respectively. The host bacteria exhibited regrowth 21 h after infection, most likely attributed to the presence of spontaneous mutations (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Bacterial cell lytic assay. The Campylobacter phage CC_R7 inhibits the growth of the host bacteria, C. coli (99-2). Phage was used at different MOIs. The positive control used SM buffer instead of phage. To detect Campylobacter growth, the OD 600 nm was measured. Results are presented as means ± SEM.

3.7. Effect of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 on biofilm eradication

The biofilm formation under different treatments was evaluated, as shown in Fig. 9. The control group (Campylobacter only) exhibited the highest biofilm formation, indicating robust biofilm development under microaerobic conditions at 42 °C (Fig. 9A). In contrast, the addition of phage CC_R7 at a MOI of 100 resulted in a significant reduction in biofilm formation, demonstrating that phage at this concentration was effective in eradicating the biofilm. Similarly, the phage treatment at MOI 10 also led to a reduction in biofilm formation, but this effect was less pronounced than at MOI 100. Similarly, at 10 °C (Fig. 9B), the control group exhibited higher biofilm formation as compared to the phage treatment groups.

Fig. 9.

Effect of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 on biofilm eradication at different temperatures. (A) at 42 °C, (B) at 10 °C, (C) Effect of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 on the viability of host bacteria C. coli (99-2) on chicken meat. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Compared to the control group, ∗p < 0.05, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Different superscripts show statistically significant differences at p < 0.05.

3.8. Campylobacter phage CC_R7 application on chicken meat

The efficacy of the Campylobacter phage CC_R7 in eradicating or substantially reducing bacterial contamination on refrigerated (4 °C) retail chicken meat was assessed. The quantification of Campylobacter in the treated meat samples compared to the control samples was performed. A statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference was seen between the control and treated samples at 6, 12, and 24 h. The bacterial population in phage-treated chicken meat samples decreased by 1.2 logs CFU/g after 24 h (Fig. 9C).

4. Discussion

Campylobacter is one of the major foodborne pathogens on a global scale (Man, 2011). Poultry meat is widely recognized as a significant source of Campylobacter transmission (Shami et al., 2024). The irrational use of antibiotics in the poultry industry leads to the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter (Barbol and Alsayeqh, 2024). It has increasingly become a significant public health concern in China and worldwide (Bai et al., 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to adopt enhanced management and preventative methods to regulate infections caused by MDR Campylobacter spp. effectively (Taha-Abdelaziz et al., 2023). To improve food safety and public health, Campylobacter phages can be used as a substitute for antibiotics to control foodborne Campylobacter pathogens (Chinivasagam et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, this study aimed to assess the antibiotic susceptibility of C. coli and C. jejuni strains from China. Additionally, the study aimed to isolate a novel lytic Campylobacter phage CC_R7 with a broad host range and to analyze its complete genomic sequence, characterization, and application in chicken meat processing. In this study, 153 Campylobacter strains were isolated from chicken feces. The prevalence of C. coli in chicken (78.4 %) was higher than that of C. jejuni (21.5 %). The antibiotic resistance rate in C. coli was higher than that observed in C. jejuni isolates from poultry. Moreover, these findings highlight a notably higher prevalence of MDR in both C. coli (95 %) and C. jejuni (85 %) (Tang et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2023).

In light of the growing problem of antibiotic resistance, phage therapy can be a potent tool against multidrug-resistant (MDR) food-borne infections like Campylobacter (Olson et al., 2022). Therefore, phage CC_R7 was isolated, which has a broad host range, lyses 60 % of C. coli and 22 % of C. jejuni of strains tested, surpassing the effectiveness of group II Campylobacter phage CP21 (Jäckel et al., 2015). Transmission electron microscopy analysis showed that CC_R7 belongs to the Myoviridae family with an isometric head and long contractile tail. The diameter of the head was 97.4 nm ± 5.66, and the length of the tail was 126.8 nm ± 3.2 nm. Therefore, it is consistent with Campylobacter phage group II (tail size 110–142 nm), which differs from group III phages (tail size 98–100 nm) in that it has a longer tail (Javed et al., 2014). The genome of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 (PQ092953) comprises 180,566 bp, placing it into the Campylobacter phage group II. According to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, genus-level classification requires at least 70 % nucleotide identity across the whole genome, while species-level classification requires 95 % genome sequence identity (Adriaenssens and Brister, 2017). Phage CC_R7 could be included in the genus Firehammervirus because it shares the highest degree of similarity and genome organization with the Campylobacter phage CP220 as shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5. The CC_R7 genome shared <95 % identity with Campylobacter phage CP220 (93.84 %) at the nucleotide level, as determined by BLASTn; therefore, CC_R7 may represent a new species in the genus Firehammervirus. The phage CC_R7 has a GC content of 27.8 %, which is lower than that of the host bacterium Campylobacter spp. (31 %), and approximately the same as that of other group II sequenced phages (CP220, CPt10, and CP21) (Timms et al., 2010; Jäckel et al., 2015). The phage CC_R7 primarily uses ATG as the primary initiation codon (87.5 %), consistent with the overall genetic makeup of bacterial and phage genomes reported in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) (Belin, 1979; Villegas and Kropinski, 2008). Furthermore, CC_R7 contains tRNA genes for isoleucine (tRNA-Ile, GAT) and tyrosine (tRNA-Tyr, GTA), which sets it apart from previously sequenced group II Campylobacter phages (CP220, CPt10, and IBB_35) which have tRNAs for arginine (Arg) and tyrosine (Tyr) and phage (CP21) which has tRNAs for arginine (Arg) and proline (Pro). The presence of tRNA-Ile (GAT) in CC_R7 indicates that it has specifically evolved to improve translation in host conditions where isoleucine codons are common. This adaptation likely enhances the synthesis of viral proteins, replication efficiency, and infectivity for particular bacterial hosts (Jäckel et al., 2015). The sequence data obtained from CC_R7 provides information about the presence of morphogenesis proteins and a range of genes related to DNA replication, modification, and repair, lysis, and additional functions. At the protein level, most predicted CC_R7 products have over 90 % similarity to CP220 proteins. Furthermore, certain proteins have more than 20 % similarity with T4 bacteriophage (Escherichia phage T4, accession no. AF158101) proteins (supplementary File 1, Table S6) (Miller et al., 2003). Furthermore, CC_R7 does not contain any genes related to pathogenicity or virulence, making it genetically safe to use.

After the genomic analysis, phage CC_R7 underwent further categorization based on adsorption assay, burst size, phage stability, and lytic activity. The adsorption assay of CC_R7 showed good penetration power to host bacteria. The maximum (50 %) adsorption was during the first 5 min, showing its ability to effectively penetrate the host bacteria (Al-Mohammadi et al., 2022). Bacteriophage multiplication is demonstrated by its one-step growth curve, and optimizing phage fitness is linked to an ideal latent time, balancing it to enhance burst size. CC_R7 has a latent period of 40 min, which is shorter than that of phages phiCcoIBB35 (52.5 min), phiCcoIBB12 (82.5 min), and phiCcoIBB37 (67.5 min). The burst size of CC_R7 was 119 phages/infected bacteria, which is higher than that of phages phiCcoIBB35 (24 virions), phiCcoIBB12 (22 virions), and phiCcoIBB37 (9 virions) (Carvalho et al., 2010). In the food sector, it is preferable for bacteriophages utilized for biocontrol purposes to have large burst sizes and short latent periods (Kim et al., 2020). These findings provide evidence that bacteriophage CC_R7 has the potential to be a suitable candidate for practical applications.

Bacteriophages are specific to the receptors on the surface of host cells (Taslem Mourosi et al., 2022). Phage CC_R7 showed varying lytic activity across different regions of China, with the highest lytic activity observed in C. coli from Hubei. In Hubei, 9 out of 13 C. coli isolates were lysed (7 strongly, 2 weakly). In Hunan, 8 out of 13 C. coli isolates were lysed (5 strongly, 3 weakly), and in Jiangxi, 4 out of 8 were lysed (2 strongly, 2 weakly). For C. jejuni, 4 out of 10 isolates were lysed in Hubei (2 strongly, 2 weakly), while only weak lysis was observed in Hunan (1/7) and Jiangxi (1/5). These differences in lytic activity may be due to variations in the surface receptors of the bacteria, bacterial defense mechanisms, and regional genetic diversity (Holtappels et al., 2023).

Assessing the stability of bacteriophages at different temperatures and pH levels is crucial in determining their suitability for phage therapy applications (Ly-Chatain, 2014). This study showed that phage CC_R7 exhibited stability within the temperature range of 4 °C–50 °C. This feature allows the application of CC_R7 under different temperature conditions (Thung et al., 2020). Conversely, pH stability experiments demonstrated that the phage titer remained stable throughout a pH range of 4–10, showing its potential to work under different pH conditions (El-Shibiny et al., 2009).

Furthermore, the lytic potential of the phage CC_R7 against Campylobacter species was assessed at various MOIs. The viability of Campylobacter spp. infected with CC_R7 showed a substantial decrease compared to the untreated control. The most potent suppression of Campylobacter spp. occurred when the bacterial host was exposed to MOI 0.1. However, the observed re-growth of the host bacteria at 21 h after infection is probably caused by phage resistance due to spontaneous mutations; however, occurring at slower rate compared to previous research (Hwang et al., 2009).

To date, only one Campylobacter phage-based product (GRN 966) has received FDA approval for use in the meat industry, highlighting the need for further research to develop and approve additional phage-based interventions with a broader host range (FDA, 2020). Expanding the repertoire of well-characterized phage therapeutics could enhance their efficacy and applicability in controlling Campylobacter. In application, the phage CC_R7 showed a potential anti-biofilm activity against Campylobacter under slaughterhouse conditions, and the efficacy of phage CC_R7 was assessed in eradicating or substantially reducing bacterial contaminations on refrigerated (4 °C) retail chicken meat. In our result, the phage CC_R7 decreased the bacterial load by 1.2 logs on artificially contaminated chicken meat pieces at MOI (10). The CC_R7 treatment effectively stopped Campylobacter from growing at low temperatures, showing that the phage worked well against foodborne germs in cold conditions (Firlieyanti et al., 2016; Thung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024).

5. Conclusion

The global rise of AMR Campylobacter in poultry meat is a major public health concern, with C. coli being more common and resistant to multiple drugs compared to C. jejuni. Researchers are exploring different strategies to address the issue of resistant Campylobacter contamination, such as phage therapy. The Campylobacter phage CC_R7 isolated in this study was successfully purified, and it has demonstrated significant lytic activity and stability. Genomic study indicates that phage CC_R7 has no genes linked to pathogenicity or resistance. The phage CC_R7 has shown potential in reducing Campylobacter levels in chicken meat, suggesting its usefulness as a biocontrol agent and offering an alternative to chemical bactericides. However, this study warrants further in-depth molecular typing or serotyping of the Campylobacter strains to better understand the host range of phage CC_R7, and in vivo analysis for the proper incorporation of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 as a potential biocontrol agent to control Campylobacter in the food chain.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Muhammad Shahzad Rafiq: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft. Jie Chen, Muhammad Akmal, Dongxin Ma: Visualization, Writing—review & editing. Ali Asif, Junhao Wang: Data Curation. Yufeng Gu, Shuaifeng Gu: Writing—review & editing. Pan Tao: Methodology. Haihong Hao: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Data

The annotated complete genome sequence of Campylobacter phage CC_R7 reported herein is available at GenBank under accession PQ092953.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC) of China grant U23A20241/32172914, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities grant 2662025PY032, and the earmarked fund for CARS-41.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Dr. Siyun Wang

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2025.101182.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Adriaenssens E.M., Brister J.R. How to name and classify your phage: an informal guide. Viruses. 2017;9:70. doi: 10.3390/v9040070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmal M., Araki K., Nishiki I., Yoshida T. Isolation and complete genome sequencing of NS-I, a lytic bacteriophage infecting fish pathogenic strains of Nocardia seriolae. PHAGE. 2023;4:151–158. doi: 10.1089/phage.2023.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohammadi A.-R., El-Didamony G., Abd El Moneem M.S., Elshorbagy I.M., Askora A., Enan G. Isolation and characterization of lytic bacteriophages specific for Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Zoonotic Diseases. 2022;2:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Al Hakeem W.G., Oladeinde A., Li X., Cho S., Kassem I.I., Rothrock Jr M.J. Campylobacter diversity along the Farm‐to‐Fork continuum of pastured poultry flocks in the Southeastern United States. Zoonoses and Public Health. 2025;72:55–64. doi: 10.1111/zph.13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam K., Lastovica A.J., Le Roux E., Hossain M.A., Islam M.N., Sen S.K., Sur G.C., Nair G.B., Sack D.A. Clinical characteristics and serotype distribution of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from diarrhoeic patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Cape Town, South Africa. Bangladesh J. Microbiol. 2006;23:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. Cambridge; United Kingdom: 2010. FastQC: a Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo P.M., Batista E., Fernandes M.H., Fernandes M.J., Gama L.T., Fraqueza M.J. Assessment of biofilm formation by Campylobacter spp. isolates mimicking poultry slaughterhouse conditions. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askoura M., Saed N., Enan G., Askora A. Characterization of polyvalent bacteriophages targeting multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia with enhanced anti-biofilm activity. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021;57:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Authority, E.F.S., Prevention, E.C.f.D., Control The European union one health 2023 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024;22 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2024.9106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrad M., Tkhawkho L., Isakovich N., Nitzan O., Peretz A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli: comparison between Etest and a broth dilution method. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2018;17:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12941-018-0275-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J., Chen Z., Luo K., Zeng F., Qu X., Zhang H., Chen K., Lin Q., He H., Liao M. Highly prevalent multidrug-resistant Campylobacter spp. isolated from a yellow-feathered broiler slaughterhouse in South China. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.682741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbol B.I., Alsayeqh A.F. Use of polyphenols for the control of chicken meat borne zoonotic Campylobacter jejuni serotypes O1/44, O2, and O4 complex. Pak. Vet. J. 2024;44:978–987. [Google Scholar]

- Belin D. Bacteriophage T4 r IIB protein synthesis with a temperature-sensitive mutation in the r IIB initiation codon. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG. 1979;171:35–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00274012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer J., Borodovsky M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W451–W454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolocan A.S., Upadrasta A., de Almeida Bettio P.H., Clooney A.G., Draper L.A., Ross R.P., Hill C. Evaluation of phage therapy in the context of Enterococcus faecalis and its associated diseases. Viruses. 2019;11:366. doi: 10.3390/v11040366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla N., Rojas M.I., Cruz G.N.F., Hung S.-H., Rohwer F., Barr J.J. Phage on tap–a quick and efficient protocol for the preparation of bacteriophage laboratory stocks. PeerJ. 2016;4 doi: 10.7717/peerj.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher J., Stintzi A. Springer; 2017. Campylobacter jejuni. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C.M., Gannon B.W., Halfhide D.E., Santos S.B., Hayes C.M., Roe J.M., Azeredo J. The in vivo efficacy of two administration routes of a phage cocktail to reduce numbers of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in chickens. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho C.M., Kropinski A.M., Lingohr E.J., Santos S.B., King J., Azeredo J. The genome and proteome of a Campylobacter coli bacteriophage vB_CcoM-IBB_35 reveal unusual features. Virol. J. 2012;9:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinivasagam H.N., Estella W., Maddock L., Mayer D.G., Weyand C., Connerton P.L., Connerton I.F. Bacteriophages to control Campylobacter in commercially farmed broiler chickens, in Australia. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:632. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damtew Y.T., Tong M., Varghese B.M., Anikeeva O., Hansen A., Dear K., Driscoll T., Zhang Y., Capon T., Bi P. The impact of temperature on non-typhoidal Salmonella and Campylobacter infections: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. EBioMedicine. 2024;109 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher A.L., Bratke K.A., Powers E.C., Salzberg S.L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis M., Soumet C., Rivoal K., Ermel G., Blivet D., Salvat G., Colin P. Development of am‐PCR assay for simultaneous identification of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999;29:406–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1999.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Saadony M.T., Saad A.M., Yang T., Salem H.M., Korma S.A., Ahmed A.E., Mosa W.F., Abd El-Mageed T.A., Selim S., Al Jaouni S.K. Avian campylobacteriosis, prevalence, sources, hazards, antibiotic resistance, poultry meat contamination and control measures: a comprehensive review. Poult. Sci. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shibiny A., Scott A., Timms A., Metawea Y., Connerton P., Connerton I. Application of a group II Campylobacter bacteriophage to reduce strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli colonizing broiler chickens. J. Food Protect. 2009;72:733–740. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar C.E., Jarrett J.T. Radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) superfamily. eLS. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- FDA . 2019. Preparation Containing Bacterial Phages Specific to shiga-toxin Producing Escherichia Coli: GRN No. 834. [Google Scholar]

- FDA . 2020. Preparations Containing Three to Eight Bacteriophages Specific to Campylobacter jejuni GRN No. 966. [Google Scholar]

- FDA . 2022. Preparations Containing Six Bacteriophages (Phage) Specific to Salmonella Enterica: GRN No. 1070. [Google Scholar]

- Firlieyanti A.S., Connerton P.L., Connerton I.F. Campylobacters and their bacteriophages from chicken liver: the prospect for phage biocontrol. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016;237:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Tu L., Chen M., Chen H., Zhang X., Zhuang Y., Luo J., Chen M. Erythromycin resistance of clinical Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in Shanghai, China. Front. Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1145581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gencay Y.E., Birk T., Sørensen M.C.H., Brøndsted L. Campylobacter Jejuni: Methods and Protocols. Springer; 2016. Methods for isolation, purification, and propagation of bacteriophages of Campylobacter jejuni; pp. 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerl J.A., Jäckel C., Reetz J., Hertwig S. The complete genome sequence of bacteriophage CP21 reveals modular shuffling in Campylobacter group II phages. Am Soc Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01252-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang D.T., Chernomor O., Von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q., Vinh L.S. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtappels D., Alfenas-Zerbini P., Koskella B. Drivers and consequences of bacteriophage host range. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023;47 doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuad038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutinet G., Kot W., Cui L., Hillebrand R., Balamkundu S., Gnanakalai S., Neelakandan R., Carstens A.B., Fa Lui C., Tremblay D. 7-Deazaguanine modifications protect phage DNA from host restriction systems. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5442. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13384-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S., Yun J., Kim K.P., Heu S., Lee S., Ryu S. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages specific for Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;53:559–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäckel C., Hammerl J.A., Reetz J., Kropinski A.M., Hertwig S. Campylobacter group II phage CP21 is the prototype of a new subgroup revealing a distinct modular genome organization and host specificity. BMC Genom. 2015;16:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1837-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jault P., Leclerc T., Jennes S., Pirnay J.P., Que Y.-A., Resch G., Rousseau A.F., Ravat F., Carsin H., Le Floch R. Efficacy and tolerability of a cocktail of bacteriophages to treat burn wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PhagoBurn): a randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019;19:35–45. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed M.A., Ackermann H.-W., Azeredo J., Carvalho C.M., Connerton I., Evoy S., Hammerl J.A., Hertwig S., Lavigne R., Singh A. A suggested classification for two groups of Campylobacter myoviruses. Arch. Virol. 2014;159:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaru S., Ishiwata Y., Suzuki T., Rossmann M.G., Arisaka F. Control of bacteriophage T4 tail lysozyme activity during the infection process. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Kim H.J., Jung S.J., Mizan M.F.R., Park S.H., Ha S.D. Characterization of Salmonella spp.‐specific bacteriophages and their biocontrol application in chicken breast meat. J. Food Sci. 2020;85:526–534. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett D., Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:11–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Cai H., Xu B., Dong Q., Jia K., Lin Z., Wang X., Liu Y., Qin X. Prevalence, antibiotic resistance, resistance and virulence determinants of Campylobacter jejuni in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. One Health. 2025 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2025.100990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Lee S.A., Xue J., Riordan S.M., Zhang L. Global epidemiology of campylobacteriosis and the impact of COVID-19. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.979055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly-Chatain M.H. The factors affecting effectiveness of treatment in phages therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:51. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man S.M. The clinical importance of emerging Campylobacter species. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;8:669–685. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., Lu S., Anderson J.B., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., DeWeese-Scott C., Fong J.H., Geer L.Y., Geer R.C., Gonzales N.R. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39:D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis S., Madden T.L. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W20–W25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E.S., Kutter E., Mosig G., Arisaka F., Kunisawa T., Rüger W. Bacteriophage T4 genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:86–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushegian A. Are there 1031 virus particles on earth, or more, or fewer? J. Bacteriol. 2020;202 doi: 10.1128/jb.00052-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole G.A. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2011;2437 doi: 10.3791/2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson E.G., Micciche A.C., Rothrock Jr M.J., Yang Y., Ricke S.C. Application of bacteriophages to limit Campylobacter in poultry production. Front. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.458721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope W.H., Jacobs-Sera D. Annotation of bacteriophage genome sequences using DNA Master: an overview. Bacteriophages: Methods Protoc. 2018;3:217–229. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7343-9_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattanachaikunsopon P., Phumkhachorn P. Enterica Serovar Typhi. Salmonella-Distribution, Adaptation, Control Measures and Molecular Technologies. 2006. Bacteriophage PPST1 isolated from hospital wastewater, a potential therapeutic agent against drug resistant Salmonella enterica subsp; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rihtman B., Meaden S., Clokie M.R., Koskella B., Millard A.D. Assessing Illumina technology for the high-throughput sequencing of bacteriophage genomes. PeerJ. 2016;4 doi: 10.7717/peerj.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin O., Yaeger M., Wu Z., Zhang Q. Campylobacter-associated diseases in animals. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 2017;5:21–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sails A., Wareing D., Bolton F., Fox A., Curry A. Characterisation of 16 Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli typing bacteriophages. J. Med. Microbiol. 1998;47:123–128. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-2-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooley R.T., Biswas B., Gill J.J., Hernandez-Morales A., Lancaster J., Lessor L., Barr J.J., Reed S.L., Rohwer F., Benler S. Development and use of personalized bacteriophage-based therapeutic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/aac.00954-00917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shami A., Abdallah M., Alruways M.W., Mostafa Y.S., Alamri S.A., Ahmed A.E., Al Ali A., Ali M.E. Comparative prevalence of virulence genes and antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from broilers, laying hens and farmers. Pak. Vet. J. 2024;44:200–204. [Google Scholar]

- Söding J., Biegert A., Lupas A.N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W244–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M.J., Petty N.K., Beatson S.A. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha-Abdelaziz K., Singh M., Sharif S., Sharma S., Kulkarni R.R., Alizadeh M., Yitbarek A., Helmy Y.A. Intervention strategies to control Campylobacter at different stages of the food chain. Microorganisms. 2023;11:113. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M., Zhou Q., Zhang X., Zhou S., Zhang J., Tang X., Lu J., Gao Y. Antibiotic resistance profiles and molecular mechanisms of Campylobacter from chicken and pig in China. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.592496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Yang R., Wu Q., Ding Y., Wang Z., Zhang J., Lei T., Wu S., Zhang F., Zhang W. First report of the optrA-carrying multidrug resistance genomic island in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from pigeon meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021;354 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2021.109320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao P., Mahalingam M., Rao V.B. Highly effective soluble and bacteriophage T4 nanoparticle plague vaccines against Yersinia pestis. Vaccine Design: Methods Protoc. 2016;1:499–518. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3387-7_28. Vaccines for Human Diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taslem Mourosi J., Awe A., Guo W., Batra H., Ganesh H., Wu X., Zhu J. Understanding bacteriophage tail fiber interaction with host surface receptor: the key “blueprint” for reprogramming phage host range. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232012146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Higgins D.G. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2003;2(3) doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0203s00. 1-2.3. 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thung T.Y., Lee E., Mahyudin N.A., Wan Mohamed Radzi C.W.J., Mazlan N., Tan C.W., Radu S. Partial characterization and in vitro evaluation of a lytic bacteriophage for biocontrol of Campylobacter jejuni in mutton and chicken meat. J. Food Saf. 2020;40 [Google Scholar]

- Timms A.R., Cambray-Young J., Scott A.E., Petty N.K., Connerton P.L., Clarke L., Seeger K., Quail M., Cummings N., Maskell D.J. Evidence for a lineage of virulent bacteriophages that target Campylobacter. BMC Genom. 2010;11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend E.M., Kelly L., Gannon L., Muscatt G., Dunstan R., Michniewski S., Sapkota H., Kiljunen S.J., Kolsi A., Skurnik M. Isolation and characterization of Klebsiella phages for phage therapy. Therapy, Applications, and Research. 2021;2:26–42. doi: 10.1089/phage.2020.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaraw P., Prajapati A., Verma A.K., Pathak V., Singh V. Control of campylobacter in poultry industry from farm to poultry processing unit: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;57:659–665. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.935847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushanov L., Lasareishvili B., Janashia I., Zautner A.E. Application of Campylobacter jejuni phages: challenges and perspectives. Animals. 2020;10:279. doi: 10.3390/ani10020279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas A., Kropinski A.M. An analysis of initiation codon utilization in the Domain Bacteria–concerns about the quality of bacterial genome annotation. Microbiology. 2008;154:2559–2661. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/021360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-w., Xi H.-y., Su J.-z., Cheng M.-j., Wang G., He D.-l., Cai R.-p., Wang Z.-j., Guan Y., Sun C.-j. 2020. Characterization and Genome Analysis of a Novel Escherichia coli Bacteriophage vB_EcoS_W011D. [Google Scholar]

- Wick R.R., Judd L.M., Gorrie C.L., Holt K.E. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., McGinnis S., Madden T.L. BLAST: improvements for better sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W6–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li Y., Shao Y., Hu Y., Lou H., Chen X., Wu Y., Mei L., Zhou B., Zhang X. Molecular characterization and antibiotic resistant profiles of Campylobacter species isolated from poultry and diarrheal patients in Southeastern China 2017–2019. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1244. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Tang M., Zhou Q., Lu J., Zhang H., Tang X., Ma L., Zhang J., Chen D., Gao Y. A broad host phage, CP6, for combating multidrug-resistant Campylobacter prevalent in poultry meat. Poult. Sci. 2024;103 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2024.103548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.