Abstract

Background

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) has emerged as a significant cardiovascular phenotype among individuals experiencing postacute COVID-19 syndrome, commonly referred to as long COVID.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to describe the experience of people reporting long COVID-associated POTS.

Methods

We collected data from individuals aged ≥18 years with self-reported long COVID who participated in the Yale Listen to Immune, Symptom and Treatment Experiences Now (LISTEN) cohort, an online observational study. The study included participants surveyed from May 2022 to July 2023. POTS status was determined by self-reported diagnosis of POTS. We compared the demographics, symptoms, associated conditions, and health status of people with and without self-reported POTS.

Results

Of the 578 individuals included, 167 (28.9%) reported new-onset POTS and 411 (71.1%) did not report POTS as one of their long COVID-associated conditions. Seventy-eight percent of participants with self-reported POTS were women (range, 18-74 years). Participants with self-reported POTS were younger, had more financial difficulties, more social isolation, more suicidal thoughts, worse health status measured by the EuroQoL visual analog scale, and reported higher rates of rapid heart rate after standing up, dizziness, palpitations, persistent chest pain, sudden chest pain, excessive fatigue, exercise intolerance, heat intolerance, brain fog, tinnitus, migraine, internal tremors, skin discoloration, and dry eyes, as well as new-onset myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and mast cell disorders.

Conclusions

Individuals with self-reported long COVID-associated POTS experienced substantial health burdens in various domains compared with those without self-reported POTS, highlighting the urgency for further research to understand the mechanism, characterize the physiological derangements, and target treatments so we can help these individuals.

Key words: COVID-19, long COVID, POTS

Central Illustration

Postacute COVID-19 syndrome, or long COVID, is estimated to affect 10 to 20% of people infected by SARS-COV-2.1, 2, 3 Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) has emerged as a significant cardiovascular phenotype among individuals experiencing long COVID.4 POTS is defined as a clinical syndrome usually characterized by: 1) frequent symptoms that occur with standing, such as lightheadedness, palpitations, tremulousness, generalized weakness, blurred vision, exercise intolerance, and fatigue; 2) a sustained increase in heart rate of ≥30 beats/min, often with a standing heart rate >120 beats/min, within 10 minutes of standing or in a tilt table test in adults; and 3) the absence of orthostatic hypotension.5,6 While these criteria are used clinically, it is important to note that in our study, POTS status was based on participants’ self-reported history of physician-diagnosed POTS rather than formal testing.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, POTS had been recognized as an established multisystemic autonomic disorder that affects the neurologic and cardiovascular systems, associated with significant functional impairment that often occurred after a viral illness.6,7 Patients with POTS experience increased heart rate when standing, which often results in a decreased ability to participate in education and limited capacity to work, leading to reduced income and significantly impaired quality of life.8

POTS as a phenotype of long COVID has not been comprehensively characterized. Some smaller studies have reported POTS as a common condition among patients with long COVID, with up to 61% of patients reporting symptoms suggestive of POTS.4,9, 10, 11 However, the lived experience of those individuals with self-reported long COVID-associated POTS is not clear. Specifically, we know little about how characteristics such as demographics, socioeconomic factors, health status, and daily living of individuals with self-reported long COVID-associated POTS differ from those of individuals without self-reported POTS.

This study aims to fill this gap by describing POTS in the context of long COVID by contrasting the symptoms, associated conditions, treatments, and health status of individuals who reported being diagnosed with POTS with those who did not in the Yale LISTEN (Listen to Immune, Symptom and Treatment Experiences Now) online observational study.

Methods

Study design

The LISTEN study is an online, decentralized, participant-centric, observational study. Study details have been published previously.12 The study included 2 parts: survey and electronic health record (EHR) data collection to characterize clinical phenotypes, and biospecimen analysis for immunophenotyping.

Study recruitment

The LISTEN study recruited participants from the Hugo Health Kindred community, an online group of people aged 18 years and older interested in contributing to COVID-19 research. Information about the community was spread by word-of-mouth and social media. It was open to people worldwide and without cost. People were invited to respond to surveys and connect their medical records for research.

Data

Demographic and socioeconomic survey items included age, gender, race and ethnicity, marital status, prepandemic employment and income, housing insecurity, and country of residence. Self-reported time of index SARS-CoV-2 infection was categorized as pre-Delta (before June 26, 2021), Delta (June 26-December 24, 2021), Omicron (December 25, 2021-June 25, 2022), and post-Omicron (after June 25, 2022), consistent with the times associated with dominant variants of SARS-CoV-2.13 SARS-CoV-2 infection severity was assessed by self-reported hospitalization history for COVID-related conditions.

The demographic survey included 2 questions about health status; self-reported health status was assessed by the EuroQoL visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), using a visual sliding scale ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 means the worst and 100 means the best.14 The second question was also a visual sliding scale indicating the severity of long COVID symptoms when participants felt them the most, where 0 means trivial illness and 100 means unbearable illness (Supplemental Methods 1). The conditions and symptoms survey assessed prepandemic comorbidities, current conditions, and long COVID symptoms. All conditions, including myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and mast cell activation syndrome, were based on self-reported physician diagnoses without requiring EHR confirmation or documentation of specific diagnostic criteria. The survey contained separate questions asking about asthma and allergies to differentiate these conditions from mast cell disorders, but no further diagnostic details or criteria were collected (conditions assessed are detailed in Supplemental Methods 2 to 4). We collected detailed information on treatments used by participants through the survey. Reported treatments were grouped into 40 categories based on common pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions (Supplemental Table 5).15

Participants with long COVID were identified as those who replied “yes” to the question, “Do you think you have long COVID?” Additionally, within those reporting long COVID, participants with self-reported POTS were identified by having answered “yes” to the question, “Currently, have you ever been told by a doctor that you have any of the following?” One of the choices was “POTS.”

Statistical analysis

We described participant characteristics using percentages for categorical variables and median (IQR) for continuous variables. We compared participants with and without self-reported POTS on their demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, medical conditions, and long COVID symptoms. We used chi-square and Fisher exact tests to compare responses for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum test and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test for continuous variables. When comparing the 3 domains of prepandemic comorbidities, new-onset conditions, and long COVID symptoms between the 2 groups, we corrected for multiple testing using the Bonferroni method within each domain and reported adjusted P values. All tests were 2-sided. Any P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. By using the Bonferroni method, family-wise error rates were controlled at the level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were done in R version 4.3.1.

The LISTEN study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board on April 1, 2022. Participants were provided electronic consent forms. LISTEN conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines. H.M.K., a co-founder of Hugo Health, helped develop the Hugo Kindred platform and the Yale Conflict of Interest Committee oversaw his involvement in this work.

Results

Of the 858 individuals with self-reported long COVID who provided consent and enrolled in the LISTEN study between May 2022 and July 2023, 263 were excluded due to missing POTS status and another 17 were excluded due to prior history of self-reported POTS. After exclusions, 578 (67.4%) were included in the study cohort. Among these, 167 participants (28.9%) reported new-onset POTS as part of their long COVID, while 411 (71.1%) did not report POTS as one of their long COVID-associated conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

A total of 578 participants were in the analytical cohort after excluding those with incomplete conditions and symptoms survey, missing information about POTS status, and previous self-reported POTS diagnosis. LISTEN = Listen to Immune, Symptom and Treatment Experiences Now; POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Participants with self-reported POTS were younger, with a median age of 43 years (IQR: 35-51), compared with participants without self-reported POTS (47 years [IQR: 39-58]) (P < 0.001). Participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to be female (78% vs 71%; P = 0.01). The 2 groups had no differences in race and ethnicity, country of residence, prepandemic employment status, prepandemic household income, health insurance status, level of social support, and housing circumstances (Table 1). However, participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to report experiencing greater financial difficulties caused by the pandemic (19% vs 13%; P = 0.017) and social isolation (48% vs 35%; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics, Socioeconomic Characteristics, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection Characteristicsa

| Overall (N = 578) |

No Self-Reported POTS (n = 411) |

Self-Reported POTS (n = 167) |

P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), | 46 (37-56) | 47 (39-58) | 43 (35-51) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.010 | |||

| Female | 422 (73.0%) | 292 (71.0%) | 130 (78.0%) | |

| Male | 148 (26.0%) | 116 (28.0%) | 32 (19.0%) | |

| Nonbinary | 8 (1.4%) | 3 (0.7%) | 5 (3.0%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.965 | |||

| White | 496 (86.0%) | 353 (86.0%) | 143 (86.0%) | |

| Black | 12 (2.1%) | 9 (2.2%) | 3 (1.8%) | |

| Latino | 13 (2.2%) | 9 (2.2%) | 4 (2.4%) | |

| Asian | 17 (2.9%) | 13 (3.2%) | 4 (2.4%) | |

| Other | 40 (6.9%) | 27 (6.6%) | 13 (7.8%) | |

| Marital status | 0.025 | |||

| Married or civil union | 318 (59.0%) | 227 (59.0%) | 94 (57.0%) | |

| Divorced | 56 (10.0%) | 48 (13.0%) | 8 (5.0%) | |

| Separated | 9 (1.7%) | 5 (1.3%) | 4 (2.5%) | |

| Widowed | 8 (1.5%) | 6 (1.6%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Never married | 152 (28.0%) | 98 (26.0%) | 54 (34.0%) | |

| Employed prepandemic | 465 (86.0%) | 325 (85.0%) | 140 (88.0%) | 0.332 |

| Prepandemic annual household income ($) | 0.250 | |||

| 75,000 or more | 379 (70.0%) | 261 (68.0%) | 118 (74.0%) | |

| 50,000-<75,000 | 50 (9.2%) | 35 (9.1%) | 15 (9.4%) | |

| 35,000-<50,000 | 38 (7.0%) | 26 (6.8%) | 12 (7.5%) | |

| 10,000-<35,000 | 29 (5.4%) | 24 (6.3%) | 5 (3.1%) | |

| <10,000 | 8 (1.5%) | 5 (1.3%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 38 (7.0%) | 32 (8.4%) | 6 (3.8%) | |

| Index SARS-CoV-2 infection time period | 0.134 | |||

| Pre-Delta | 207 (41.0%) | 134 (37.0%) | 73 (49.0%) | |

| Delta | 62 (12.0%) | 46 (13.0%) | 16 (11.0%) | |

| Omicron | 150 (30.0%) | 111 (31.0%) | 39 (26.0%) | |

| Post-Omicron | 89 (18.0%) | 67 (19.0%) | 22 (15.0%) | |

| Hospitalized for COVID-related conditions | 52 (9.0%) | 36 (8.8%) | 16 (9.6%) | 0.754 |

| Financial difficulties caused by the pandemic | 0.017 | |||

| Not at all | 174 (32.0%) | 138 (36.0%) | 36 (23.0%) | |

| A little | 201 (37.0%) | 136 (36.0%) | 65 (41.0%) | |

| Very much | 82 (15.0%) | 51 (13.0%) | 31 (19.0%) | |

| Quite a bit | 85 (16.0%) | 58 (15.0%) | 27 (17.0%) | |

| Do not have health insurance | 19 (3.3%) | 15 (3.6%) | 4 (2.4%) | 0.443 |

| Social support (someone around to help you if you need it) | 0.917 | |||

| Never | 28 (5.2%) | 21 (5.5%) | 7 (4.4%) | |

| Rarely | 46 (8.5%) | 32 (8.3%) | 14 (8.8%) | |

| Sometimes | 104 (19.0%) | 71 (18.0%) | 33 (21.0%) | |

| Usually | 200 (37.0%) | 140 (36.0%) | 60 (38.0%) | |

| Always | 135 (30.0%) | 120 (31.0%) | 45 (28.0%) | |

| Social isolation (how often do you feel isolated from others?) | <0.001 | |||

| Hardly ever or never | 109 (20.0%) | 94 (25.0%) | 15 (9.5%) | |

| Some of the time | 220 (41.0%) | 153 (40.0%) | 67 (42.0%) | |

| Often | 211 (39.0%) | 135 (35.0%) | 76 (48.0%) | |

| Housing | 0.126 | |||

| I do not have a steady place to live | 5 (0.9%) | 4 (1.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| I have a place to live today, but I am worried about losing it in the future | 60 (11.0%) | 36 (9.4%) | 24 (15.0%) | |

| I have a steady place to live | 478 (88.0%) | 344 (90.0%) | 134 (84.0%) |

Values are median (IQR) or n (%).

POTS = postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Numbers may not sum to total due to missing data, and percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fisher exact test; Pearson's chi-squared test.

Prepandemic comorbidities

Among all participants with self-reported long COVID, the most common prepandemic comorbidities were anxiety disorders (31%), depressive disorders (29%), and gastrointestinal issues (25%), including irritable bowel syndrome and acid reflux. Of note, 9.2% of participants reported prepandemic autoimmune conditions (lupus and scleroderma). After Bonferroni correction, participants with and without self-reported POTS were not significantly different in any self-reported prepandemic comorbidities (Supplemental Table 1).

SARS-COV-2 infection characteristics

Overall, the most common period for index SARS-CoV-2 infection in this cohort was during the pre-Delta wave before June 26, 2021 (41%), and 9% of participants were hospitalized due to COVID-related conditions (Supplemental Figure 1). Participants with and without self-reported POTS were not different in index SARS-CoV-2 infection time or hospitalizations due to COVID-related conditions (Table 1).

Health status

Participants with self-reported POTS reported worse health status measured by EQ-VAS compared with those without self-reported POTS (median: 40 points [IQR: 30-55] vs 50 points [IQR: 35-68]; P < 0.001). When asked to rate their symptom severity on their worst days, participants with self-reported POTS reported greater symptom severity compared with those without self-reported POTS (median: 81 points [IQR: 74-90] vs 78 points [IQR: 61-85]; P < 0.001) (Table 2). In both groups, the period of the index SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with EQ-VAS scores (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2.

Health Status and Symptom Severity

| Overall (N = 578) |

No Self-Reported POTS (n = 411) |

Self-Reported POTS (n = 167) |

P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EuroQoL visual analog scaleb | 49 (31-61) | 50 (35-68) | 40 (30-55) | <0.001 |

| Symptom severity on worst daysc | 79 (68-88) | 78 (61-85) | 81 (74-90) | <0.001 |

Values are median (IQR).

Abbreviation as in Table 1.

Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson's chi-squared test.

(0-100), 100 means best.

(0-100), 100 means unbearable.

New-onset conditions

A greater proportion of participants with self-reported POTS reported new-onset autoimmune diseases, specifically lupus and scleroderma (11% vs 3.9%; Bonferroni-adjusted P = 0.049). Other conditions more commonly reported among participants with self-reported POTS included new-onset ME/CFS (37% vs 7.3%; Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.001), gastrointestinal issues (28% vs 12%; Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.001), migraines (21% vs 6.3%; Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.001), neurologic conditions (seizures, dementia, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, neuropathy, and small fiber neuropathy) (20% vs 8.3%; Bonferroni-adjusted P = 0.001), mast cell disorders (16% vs 2.4%; Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.001), and arthritis (13% vs 5.1%; Bonferroni-adjusted P = 0.028). Participants with self-reported POTS reported higher rates of newly identified Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (6.6% vs 0.5%; Bonferroni-adjusted P = 0.001). There was no significant difference in new-onset coronary artery disease or cardiomyopathies (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Frequencies of New-Onset Conditions in Individuals With vs Without Self-Reported POTS

Participants with self-reported long COVID and self-reported POTS were more likely to report several new-onset conditions including ME/CFS and MCAS compared with participants with self-reported long COVID without self-reported POTS. ∗Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05 ∗∗Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.01 ∗∗∗Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.001. MCAS = mast cell activation syndrome; ME/CFS = myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; other abbreviation as in Figure 1.

Long COVID symptoms

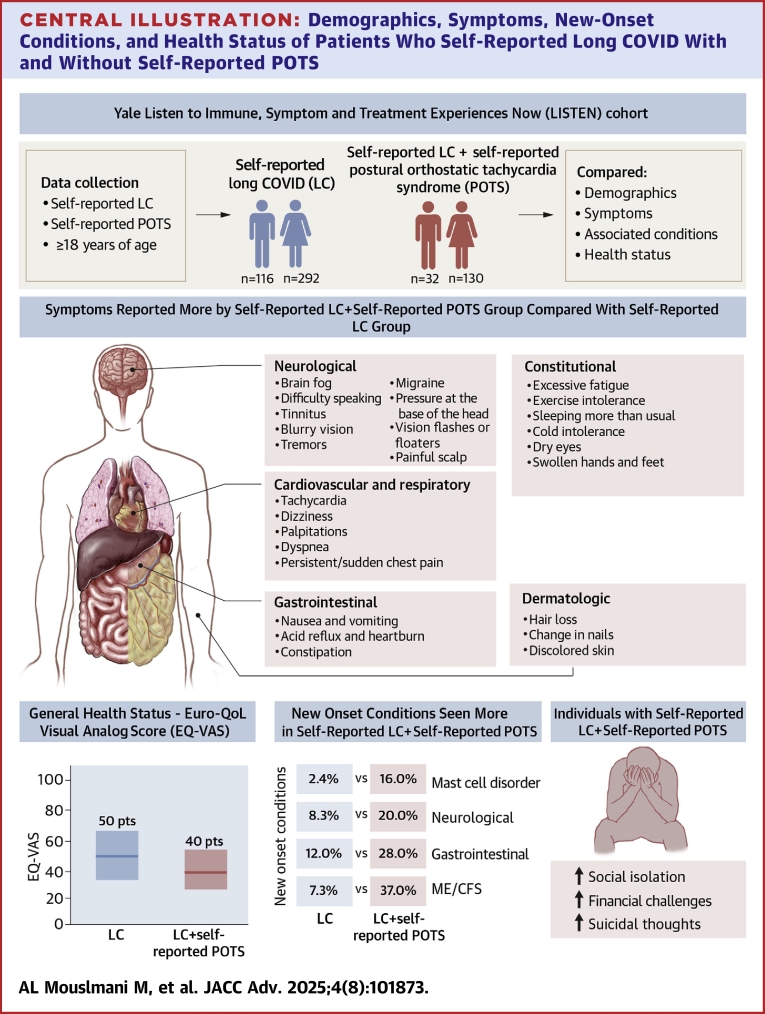

Among constitutional and generalized symptoms, participants with self-reported POTS had significantly higher rates of excessive fatigue (98% vs 84%), exercise intolerance (97% vs 72%), heat intolerance (72% vs 41%), sleeping more than usual (59% vs 36%), cold intolerance (50% vs 24%), dry eyes (42% vs 23%), and swollen hands or feet (29% vs 15%) compared with those without self-reported POTS (Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05 for each) (Supplemental Table 4, Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

Demographics, Symptoms, New-Onset Conditions, and Health Status of Patients Who Self-Reported Long COVID With and Without Self-Reported POTS

Compared with long COVID patients without self-reported POTS, those with self-reported POTS were more likely to be female, reported a greater number of persistent symptoms, experienced worse overall health status, and had higher rates of new-onset conditions. Notably, a lower EQ-VAS score indicates worse overall health status, and new-onset conditions refer to those that first appeared after March 2020. EQ-VAS = EuroQol visual analog scale; LC = long COVID; other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Among neurological symptoms, participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to have brain fog (94% vs 81%), difficulty speaking properly (65% vs 38%), tinnitus (56% vs 39%), loss or decrease in quality of vision or blurry vision (54% vs 36%), tremors or shakiness (50% vs 30%), internal tremors or vibration (50% vs 32%), migraine (47% vs 23%), pressure at the base of the head (47% vs 29%), floaters or flashes of light in vision (40% vs 21%), and painful scalp (21% vs 10%) compared with those without self-reported POTS (Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05 for each) (Supplemental Table 4, Central Illustration).

Among cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms, participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to have tachycardia or rapid heart rate after standing up (83% vs 34%), dizziness (78% vs 50%), palpitations (77% vs 45%), shortness of breath or difficulty breathing (69% vs 52%), tachycardia or rapid heart rate at rest (62% vs 33%), persistent chest pain or pressure (48% vs 26%), sharp or sudden chest pain (43% vs 22%), and costochondritis (pain on the cartilage that connects a rib to the breastbone) (35% vs 19%) compared with those without self-reported POTS (Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05 for each) (Supplemental Table 4, Central Illustration).

Among dermatologic symptoms, participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to have hair loss (50% vs 33%), change in nails (white spots, brittleness, change in moons) (31% vs 15%), and discoloration of the skin (30% vs 11%) compared with those without self-reported POTS (Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05 for each) (Supplemental Table 4, Central Illustration).

Among gastrointestinal symptoms, participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to have nausea and vomiting (45% vs 26%), acid reflux or heartburn (40% vs 25%), and constipation (37% vs 19%) compared with those without self-reported POTS (Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05 for each) (Supplemental Table 4, Central Illustration).

Among mental health symptoms, participants with self-reported POTS were more likely to have suicidal thoughts (24% vs 12%) compared with those without self-reported POTS (Bonferroni-adjusted P < 0.05) (Supplemental Table 4, Central Illustration).

Treatments

Participants with self-reported POTS reported using a wide range of treatments. Compared with participants without self-reported POTS, they were more likely to use nonpharmacological agents (90% vs 82%), vitamins and supplements (90% vs 81%), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (77% vs 68%), beta-blockers (47% vs 15%), and antihypotensive treatments such as midodrine (13% vs 1%) (P value <0.05 for each). Additionally, a greater proportion of participants with self-reported POTS reported using H1 and H2 antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, antidepressants, and opioid antagonists (P < 0.05 for each) (Supplemental Table 6).

Discussion

In our cross-sectional decentralized registry of individuals with self-reported long COVID, self-reported POTS was a common condition, reported by nearly one-third of all participants. Those with self-reported POTS were younger and more predominantly female compared with participants without self-reported POTS. Participants with self-reported POTS reported significantly higher rates of associated conditions such as ME/CFS, gastrointestinal issues, neurologic conditions, mast cell disorders, and arthritis. Participants with self-reported POTS also reported higher rates of constitutional/generalized, neurologic, cardiovascular/respiratory, gastrointestinal, and dermatologic long COVID symptoms. Importantly, participants with self-reported POTS had worse health status and higher rates of financial difficulties and social isolation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first direct comparison of the characteristics of patients with self-reported long COVID with and without self-reported POTS. Previous studies have compared individuals with POTS to individuals with long COVID or controls.16, 17, 18, 19 An important finding in our study was that in a predominantly young female population of individuals with self-reported long COVID, those with self-reported POTS were even younger and more predominantly female compared with participants without self-reported POTS. Previous case reports and case series reported POTS after COVID-19 infection mostly in females with median ages of 36 and 40 years, compared with our POTS cohort with a median age of 43 years.20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Although our study relied solely on self-reported data without confirmation of POTS diagnosis via EHR or clinical testing, the prevalence of self-reported POTS in our cohort aligns with estimates from prior studies that used objective diagnostic tests.25, 26, 27 The decentralized design of the LISTEN study, conducted entirely online during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, allowed for the inclusion of participants from diverse geographic and socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as people with limited health care access. However, objective testing to confirm POTS diagnosis is needed.

Our findings contribute to the growing literature on long COVID by providing a granular look at the demographic and clinical differences within distinct long COVID phenotypes, including POTS. Rather than representing a more severe form of long COVID, POTS is likely a distinct phenotype with etiologies that differ from other manifestations, such as chronic fatigue syndrome. This distinction has important implications for treatment and prognosis, as there are specific therapies available for POTS that may mitigate its impact compared with other long COVID conditions. Further investigations into the clinical course and prognosis following long COVID are warranted to better understand the underlying mechanisms and why certain demographics, such as younger females, may be more susceptible to developing POTS.

Participants reporting POTS had higher rates of symptoms across multiple autonomic domains, including orthostatic symptoms (tachycardia and dizziness), vasomotor symptoms (skin discoloration), and secretomotor symptoms (dry eyes) compared with participants who self-reported long COVID without POTS.28, 29, 30 POTS is a heterogeneous syndrome with a wide spectrum of phenotypes and symptoms, as described by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement.31 While orthostatic intolerance symptoms, such as postural tachycardia and dizziness, are common in POTS, they are not universally present in all cases. Variability in symptom prevalence may reflect differences in patient populations, diagnostic criteria, and the timing of symptom assessment. Our findings based on self-reporting are consistent with prior studies reporting an association between long COVID and dysautonomia confirmed on objective autonomic testing.4,16,17,23,32, 33, 34 The use of POTS-specific questionnaires, such as the Malmo POTS Symptom Score or Vanderbilt Orthostatic Symptom Score, or a general autonomic dysfunction tool like Composite Autonomic Symptom Score-31, would have allowed for a more comprehensive characterization of autonomic dysfunction in our cohort. Future studies incorporating these tools are warranted to enhance the understanding of the continuum of autonomic dysfunction in the long COVID population.

Participants with self-reported POTS also reported significantly higher rates of associated conditions such as ME/CFS, gastrointestinal issues, neurologic conditions, mast cell disorders, arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis), gout, lupus, and fibromyalgia. A retrospective study comparing patients with long COVID with patients with ME/CFS via questionnaire found that both groups reported the same frequency of fatigue, myalgia, cognitive dysfunction, and postexertional malaise.35 Our findings add to the hypothesized associations between ME/CFS and long COVID, often discussed together due to overlapping symptomatology and infectious etiopathogenesis.12,35, 36, 37

Despite trying numerous treatments, individuals with self-reported POTS reported worse outcomes, including lower health status measured by EQ-VAS, greater financial difficulties, and increased social isolation compared with those without self-reported POTS. This highlights the unmet needs of this population, as existing treatments may not fully address the complexities of self-reported long COVID-associated POTS. The RECOVER AUTONOMIC study, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) initiative, is evaluating potential therapies for autonomic dysfunction in long COVID such as intravenous immunoglobulin and ivabradine, as well as nonpharmacological treatments such as diet changes and compression belts.38 Future studies should continue to explore treatments to alleviate symptoms and improve the quality of life for this vulnerable group.

Public health and clinical implications

Early diagnosis and management of POTS presenting as long COVID symptoms are crucial, as they can optimize health care resource utilization and improve patient outcomes. Current treatment strategies for POTS include a combination of lifestyle and pharmacologic therapies such as ivabradine and beta-blockers which, when instituted early in the disease course, may prevent progression to a more severe phenotype of POTS characterized by significant functional impairment.5, 6, 7,31,39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 There are also many ongoing clinical trials focused on patients with long COVID-related POTS.38 Clinicians are urged to maintain a high level of suspicion and refer long COVID patients with symptoms of POTS for thorough evaluation. This underscores the importance of increased awareness, proactive clinical strategies, and ongoing research efforts to address POTS effectively within the context of long COVID.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the study population comprised a convenience sample recruited through online platforms, which may not be representative of the general U.S. population. Additionally, the observed prevalence of certain conditions, such as dementia, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease in individuals reporting POTS may reflect the broader long COVID population rather than the classic POTS demographic. However, this study offers insights into the characteristics of individuals within this community with and without self-reported POTS.

Recruitment bias is possible due to the heightened consumer health literacy surrounding autonomic dysfunction on social media, potentially leading to preferential self-selection of individuals with autonomic symptomology into the study. Moreover, many enrolled participants did not complete their conditions and symptoms surveys, possibly due to the effort involved or low functional status, introducing potential participation bias.

Although the survey contained separate questions about allergies, asthma, and mast cell activation syndrome, these conditions may still be reported inconsistently by participants due to the lack of specific diagnostic criteria collected in the study. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was reported by participants based on self-reported physician diagnoses, as captured by a single survey question that combined Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with hypermobility (“Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [hypermobile joints]”). No further diagnostic details or criteria, such as those outlined by the 2017 Ehlers-Danlos Society, were collected.44 This lack of diagnostic specificity limits the ability to differentiate these conditions and underscores the need for caution in interpreting findings related to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Additionally, the reliance on self-reported physician diagnoses of long COVID and POTS, without requiring clinical diagnoses made by a physician with diagnostic verification, is a limitation of our study. Patients reporting new-onset POTS as a long COVID-associated condition did not need to have evidence provided from 10-minute stand or tilt table testing. This approach may have led to overestimation, underestimation, or misclassification of POTS cases. However, this limitation reflects the broad scope of the LISTEN study, which aimed to capture the lived experience of long COVID across multiple conditions rather than focusing in detail on specific diagnostic criteria. Further studies to validate the correlations between self-reported and physician-diagnosed cases are warranted.

Conclusions

In our study of individuals with self-reported long COVID, self-reported POTS was prevalent, affecting nearly one-third of participants, with a preponderance of young females. Those with self-reported POTS reported higher rates of associated conditions and experienced more severe symptoms across multiple domains compared with those without self-reported POTS. Importantly, individuals with self-reported POTS exhibited worse health status, financial difficulties, social isolation, and increased likelihood of suicidal thoughts, highlighting the need to understand the mechanism, better characterize physiological derangements, and develop targeted interventions for this subgroup.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE AND PATIENT CARE: Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for POTS as a complication of long COVID and promptly refer patients with indicative symptoms for further testing and symptomatic treatment options.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Individuals with long COVID-associated POTS face significant physical, psychological, and social challenges, emphasizing the need for increased awareness, proactive support, and ongoing research. Multidisciplinary team-based care is crucial for improving outcomes and addressing the burdens of long COVID.

Funding support and author disclosures

This project was partly supported by funds from Fred Cohen and Carolyn Klebanoff, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Collaborative COVID-19 Initiative, and by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR001863 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the authors' responsibility and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr Iwasaki co-founded RIGImmune, Xanadu Bio, and PanV and is a member of the Board of Directors of Roche Holding Ltd and Genentech. Dr Peixoto has received research grants from Reata, Bayer, and Boehringer; has also received consulting fees from Regeneron, CinCor, and DiaMedica; and Data and Safety Monitoring Board honoraria from KBP Biosciences and Ablative Solutions. In the past 3 years, Dr Krumholz has received options from Element Science and Identifeye and payments from F-Prime for advisory roles; has co-founded and held equity in Hugo Health, Refactor Health, and ENSIGHT-AI; and has been associated with research contracts through Yale University from Janssen, Kenvue, Novartis, and Pfizer. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental figures, tables, and methods, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Post COVID-19 condition (long COVID) https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition

- 2.Ballering A.V., van Zon S.K.R., Olde Hartman T.C., Rosmalen J.G.M., Lifelines Corona Research Initiative Persistence of somatic symptoms after COVID-19 in The Netherlands: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):452–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01214-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hastie C.E., Lowe D.J., McAuley A., et al. True prevalence of long-COVID in a nationwide, population cohort study. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7892. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43661-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedorowski A., Sutton R. Autonomic dysfunction and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(5):281–282. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00842-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheldon R.S., Grubb B.P., Olshansky B., et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12(6):e41–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryarly M., Phillips L.T., Fu Q., Vernino S., Levine B.D. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(10):1207–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zadourian A., Doherty T.A., Swiatkiewicz I., Taub P.R. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: prevalence, pathophysiology, and management. Drugs. 2018;78(10):983–994. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0931-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernino S., Bourne K.M., Stiles L.E., et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health Expert Consensus Meeting - Part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021;235 doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbate G., De Iulio B., Thomas G., et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome after Covid-19: a systematic review of therapeutic interventions. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2023;82(1):23–31. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000001432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goerlich E., Chung T.H., Hong G.H., et al. Cardiovascular effects of the post-COVID-19 condition. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 2024;3(2):118–129. doi: 10.1038/s44161-023-00414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ormiston C.K., Świątkiewicz I., Taub P.R. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome as a sequela of COVID-19. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19(11):1880–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2022.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou T., Sawano M., Arun A.S., et al. Internal tremors and vibrations in long COVID: a cross-sectional study. Am J Med. 2025;138(6):1010–1018.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottlieb M., Wang R.C., Yu H., et al. Severe fatigue and persistent symptoms at 3 months following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections during the pre-delta, delta, and omicron time periods: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(11):1930–1941. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabin R., de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawano M., Wu Y., Shah R.M., et al. Long COVID characteristics and experience: a descriptive study from the Yale LISTEN research cohort. Am J Med. 2025;138(4):712–720.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seeley M.C., Gallagher C., Ong E., et al. High incidence of autonomic dysfunction and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in patients with long COVID: implications for management and health care planning. Am J Med. 2025;138(2):354–361.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung T.H., Azar A. Autonomic nerve involvement in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 syndrome (PASC) J Clin Med. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.3390/jcm12010073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novak P., Giannetti M.P., Weller E., et al. Network autonomic analysis of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(12):6627–6638. doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigo S., Urechie V., Diedrich A., Okamoto L.E., Biaggioni I., Shibao C.A. Impaired parasympathetic function in long-COVID postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome - a case-control study. Bioelectron Med. 2023;9(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s42234-023-00121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amekran Y., Damoun N., El Hangouche A.J. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and post-acute COVID-19. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2022;2022(1-2) doi: 10.21542/gcsp.2022.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson M., Ståhlberg M., Runold M., et al. Long-haul post-COVID-19 symptoms presenting as a variant of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Swedish experience. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3(4):573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanjwal K., Jamal S., Kichloo A., Grubb B.P. New-onset postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome following coronavirus disease 2019 infection. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2020;11(11):4302–4304. doi: 10.19102/icrm.2020.111102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blitshteyn S., Whitelaw S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients. Immunol Res. 2021;69(2):205–211. doi: 10.1007/s12026-021-09185-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shouman K., Vanichkachorn G., Cheshire W.P., et al. Autonomic dysfunction following COVID-19 infection: an early experience. Clin Auton Res. 2021;31(3):385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10286-021-00803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedorowski A., Fanciulli A., Raj S.R., Sheldon R., Shibao C.A., Sutton R. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a major health-care burden. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21(6):379–395. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eastin E.F., Machnik J.V., Larsen N.W., et al. Evaluating long-term autonomic dysfunction and functional impacts of long COVID: a follow-up study. medRxiv. 2024 doi: 10.1101/2024.10.11.24315277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hira R., Baker J.R., Siddiqui T., et al. Objective hemodynamic cardiovascular autonomic abnormalities in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39(6):767–775. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein D.S., Cheshire W.P. The autonomic medical history. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27(4):223–233. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0425-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim M.J., Farrell J. Orthostatic hypotension: a practical approach. Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(1):39–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sletten D.M., Suarez G.A., Low P.A., Mandrekar J., Singer W. COMPASS 31: a refined and abbreviated composite autonomic symptom score. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raj S.R., Guzman J.C., Harvey P., et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(3):357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stella A., Furlanis G., Frezza N., Valentinotti R., Ajcevic M., Manganotti P. Autonomic dysfunction in post-COVID patients with and without neurological symptoms: a prospective multidomain observational study. J Neurol. 2022;269(2):587–596. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10735-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Silva F.S., Bonifácio L.P., Bellissimo-Rodrigues F., et al. Investigating autonomic nervous system dysfunction among patients with post-COVID condition and prolonged cardiovascular symptoms. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1216452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsen N.W., Stiles L.E., Shaik R., et al. Characterization of autonomic symptom burden in long COVID: a global survey of 2,314 adults. Frontiers Neurol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1012668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Retornaz F., Rebaudet S., Stavris C., Jammes Y. Long-term neuromuscular consequences of SARS-Cov-2 and their similarities with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: results of the retrospective CoLGEM study. J Transl Med. 2022;20:429. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03638-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong T.L., Weitzer D.J. Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)-a systemic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57(5):418. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choutka J., Jansari V., Hornig M., Iwasaki A. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nat Med. 2022;28(5):911–923. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.RECOVER Clinical Trials | AUTONOMIC. Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery. https://trials.recovercovid.org/autonomic

- 39.Raj S.R., Sheldon R.S. Higher quality evidence to guide our management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(7):872–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taub P.R., Zadourian A., Lo H.C., Ormiston C.K., Golshan S., Hsu J.C. Randomized trial of ivabradine in patients with hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(7):861–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raj S.R., Black B.K., Biaggioni I., et al. Propranolol decreases tachycardia and improves symptoms in the postural tachycardia syndrome: less is more. Circulation. 2009;120(9):725–734. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacob G., Diedrich L., Sato K., et al. Vagal and sympathetic function in neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):1087–1096. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moon J., Kim D.Y., Lee W.J., et al. Efficacy of propranolol, bisoprolol, and pyridostigmine for postural tachycardia syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(3):785–795. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0612-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malfait F., Francomano C., Byers P., et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017;175(1):8–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.