ABSTRACT

The KLHL gene family member KLHL5, which is a constituent factor of the RING E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, is expressed in various types of cancers and plays a role in cancer pathophysiology. In this study, we identified KLHL5 as a potential biomarker for predicting the prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) from 42 KLHL family genes using transcriptome profiles generated by RNA‐seq analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas colorectal adenocarcinoma (TCGA‐COAD). We further investigated the implication of KLHL5 in CRC using pathological examination and bioinformatics analyses. Clinicopathological analyses revealed that KLHL5 was more highly expressed in CRC than in adjacent normal mucosa, and its expression level increased concomitantly with the CRC stage (p < 0.05). KLHL5 expression was associated with poor prognostic factors such as depth of invasion (p < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion (p = 0.029), and lymph node metastasis (p = 0.025). Notably, KLHL5 exhibited heterogeneous expression within the tumor, with pronounced expression observed at the invasive front of the tumor (p < 0.0001). Through bioinformatics analyses, we determined that elevated KLHL5 expression in CRC is significantly associated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, analysis from the Gene Expression Omnibus database indicated that KLHL5 expression was more pronounced in the common molecular subtype (CMS) 4 CRC, which is characterized as highly advanced, and the overall and recurrence‐free survival rates were poor compared to other CMS groups. Our findings indicate that KLHL5 plays a pivotal role in the progression and development of CRC, and can be used as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for CRC treatment.

Keywords: adenocarcinoma, biomarkers, colorectal neoplasms, pathology, transcriptome

Bioinformatic analysis of 42 KLHL family genes identified KLHL5 as a potential prognostic biomarker for colorectal cancer (CRC), with higher expression in the common molecular subtype (CMS) 4 CRC, which is characterized by poorer overall and recurrence‐free survival rates compared to other CMS groups. KLHL5 immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 257 CRC cases, and KLHL5 expression was significantly associated with reduced overall survival.

Abbreviations

- BTB

broad‐complex, tramtrack, and bric‐abrac

- CMS

consensus molecular subtypes

- COAD

colorectal adenocarcinoma

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- Cul3

E3 ligase cullin 3

- IRS

semi‐quantitative immunoreactive score

- SPHK1

sphingosine kinase 1

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer‐related deaths worldwide according to GLOBOCAN 2020 [1] and is a leading cause of cancer‐related deaths in Japan. As for many other cancers, CRC biomarkers for detection and diagnostic and therapeutic methods for CRC have been developed. However, difficulties in controlling CRC remain.

Members of the KLHL gene family contain two evolutionarily conserved domains, including the kelch motif and broad‐complex, tramtrack, and bric‐abrac (BTB) domains, with a wide range of cellular activities, including cell cycle regulation, protein trafficking, signal transduction, DNA replication, transcription, protein quality control, circadian clock, and development [2]. The kelch domain generally occurs as a set of five to seven kelch tandem repeats that form a β‐propeller tertiary structure and is involved in actin kinetics by forming different types of binding sites. The BTB domain of Kelch proteins is a versatile protein–protein interaction motif that allows the formation of homodimers or heterodimers that mediate protein–protein interactions [3]. Several KLHL proteins bind to the E3 ligase cullin 3 (Cul3) and are known to be involved in ubiquitination, in which proteins are marked by ubiquitin, resulting in protein degradation via the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway [4]. In the Cul3/KLHL ubiquitin ligase complex, substrate recognition receptors and BTB domain‐containing proteins bind Cul3, while the Kelch domain mediates substrate recruitment.

Recently, ubiquitination, a post‐translational modification of proteins related to various vital phenomena, such as degradation or transportation of proteins, has been revealed to play a crucial role in managing cancer progression and is a potential target for cancer treatment [5]. We investigated the significance of ubiquitination machinery in cancer biology and identified several factors that compose the RING ubiquitin E3 protein complex as candidate targets for cancer treatment [6, 7, 8]. In a series of studies, we found that some KLHLs are expressed in cancer cell lines and are involved in cancer pathophysiology. We also revealed that the Cul3/KLHL ubiquitin ligase complex exerts a critical biological function in tumor progression by regulating the homeostasis of proteins that act as tumor drivers or suppressors [6, 7, 8].

In this study, we identified KLHL5 as a possible pivotal factor for CRC progression by performing an expressional narrow down of 42 KLHL family genes using a bioinformatic approach and investigated the expression and significance of KLHL5 in CRC clinical samples. In addition to the clinicopathological analyses of CRC samples, we employed several published datasets for bioinformatics analyses to evaluate the implications of KLHL5 in CRC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This study included 257 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of CRC at Nagoya City University Hospital from 2012 to 2022. Information about patient characteristics such as age, sex, site of CRC, histologic type, depth of invasion, and stage was obtained from hospital records and analyzed retrospectively. Histological classification of CRC was performed based on the typing scheme of the Japanese Classification of CRC. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Nagoya City University (no. 60‐18‐0105).

2.2. Immunohistochemical Staining

Tumors were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h. Formalin‐fixed and paraffin‐embedded sections (4 μm) were used for immunohistochemistry. Sections were stored dry until use for histological analysis. After deparaffinizing, heat slides in a microwave submerged in 10 mM citrate buffered until boiling is initiated; follow with 10 min at a sub‐boiling temperature (95°C–98°C). Cool slides on the bench top for 30 min. After pre‐incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity, sections were rinsed in PBS and blocked each section with 100 μL of preferred 10% Normal Goat Serum (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) for 10 min at room temperature. The primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4°C. KLHL5 was visualized immunohistochemically by the streptavidin‐biotin method using 1:500 rabbit anti‐KLHL5 polyclonal antibody (Sigma‐Aldrich, HPA013958). Sections were rinsed and incubated sequentially with secondary antibody (goat biotinylated anti‐rabbit IgG antibody) and with the streptavidin‐biotin‐peroxidase complex. Sections were then washed with PBS, incubated in diaminobenzidine solution containing 0.006% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and were then dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions (80%–100%). KLHL5 expression in CRC specimens was evaluated based on the semi‐quantitative immunoreactive score (IRS) by Remmele and Stegner previously reported [9]. We used IRS as the cutoff value defining the low expression group (IRS ≤ 4) and high expression group (IRS > 4) for the categorization of individual KLHL5 expressions. For objective evaluation, two independent researchers assessed the expression of KLHL5 using IRS blindly.

2.3. Antibody Absorption Test

The PrEST Antigen KLHL5 (Sigma) to anti‐KLHL monoclonal antibody mixture was made at a working dilution of 20:1 (molar ratio) and was pre‐incubated overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the pre‐absorbed antibody was incubated with tissue in place of the primary antibody alone. The staining pattern produced by the pre‐absorbed antibody was compared to that produced by the primary antibody.

2.4. Bioinformatical Analysis

Microarray data set of Skrzypczak [10] was assessed using the Oncomine Cancer Profiling Database (www.oncomine.org). Expression of KLHL5 in normal colon tissues and colon carcinoma tissues and statistics were obtained directly through the Oncomine 3.0 software. Microarray data sets of Jorissen [11] and Smith [12, 13] were assessed using PrognoScan database [14]. The average and variance of TCGA COAD cohorts were calculated by “average” function and “st.dev” function in Microsoft excel using TCGA expression data. The relationship between these gene expression and prognosis in patients with colon cancer were examined by PrognoScan database. Genome‐wide expression data of human CRC tissues were obtained from the TCGA and Gene Expression Omnibus sites (GSE13067, GSE13294, GSE14333, GSE17536, GSE2109, GSE33113, GSE35896, GSE37892, GSE39582) [12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. The clinical samples were classified into one of the four CMS groups by CMScaller R package v.2.0.1 for CMS following previous studies [20]. Tumor IMmune Estimation Resource (TIMER) analysis with COAD‐TCGA datasets was performed to estimate the infiltration of immune cells with KLHL5 and CUL3 expression [21]. Mutation analyses were performed by cBioportal using the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.2 (GraphPad Software) and R (3.3.3; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The Student's t‐test was used when two independent groups were compared, and one‐way ANOVA analyzed multiple comparisons between groups with Tukey's multiple comparisons tests. p‐values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Expressional Narrow Down of KLHL Family Genes by Bioinformatical Approach Using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (COAD) Cohorts

Transcriptome profiles generated by RNA‐seq analysis of TCGA‐COAD patients had the expression data of 42 KLHL family genes. We extracted the genes that were expressed above a certain level (Expressional mean > 1.0) in TCGA‐COAD cohorts, and varied among the patients (standard deviation > 0.7). Two genes (KLHL5 and KLHL35) were narrowed down by statistics of expressional profiles in TCGA‐COAD cohorts (Figure 1A). To explore the involvement of KLHL5 and KLHL35 in human CRC progression, several datasets were used to examine KLHL5 and KLHL35 expression in CRC to determine their prognostic value using the PrognoScan database. We found that high expression of KLHL5 was significantly correlated with poor disease‐free survival and overall survival in CRC patients (Figure 1B,C). On the other hand, low expression of KLHL35 correlated with poor prognosis (Data not shown). Since the increase of KLHL5 correlated with poor prognosis in CRC patients, we focused on KLHL5 expression and its significance in CRC. Recently, molecular classification of CRC based on gene signatures has been reported; the most robust classification is the consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) system [22]. We also analyzed KLHL5 expression among the CMS groups using TCGA‐COAD cohorts. In an analysis, the expression of KLHL5 varied among CMS types, and its expression in the adjacent normal tissues of CRC was significantly lower than that in CMS4 (Figure 1D), which is characterized by EMT‐related gene expression patterns and is associated with the worst overall prognosis and a higher rate of relapse after surgery [22].

FIGURE 1.

Identification of KLHL5 by bioinformatical approach using colorectal adenocarcinoma in the Cancer Genome Atlas. (A) Schema of narrowing down of KLHL family genes using TCGA‐COAD RNA‐seq data. Two KLHL family genes (KLHL5 and KLHL35) were extracted by transcriptome diversity approach using median and variation of gene expression. (B, C) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of disease‐free survival (B) and overall survival (C) for CRC patients with KLHL5 high and low expression were measured using PrognoScan. (D) Analysis of the correlation between KLHL5 expression and CMS in TCGA‐COAD RNA‐seq dataset. p‐values were calculated using the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Steel–Dwass post hoc test. *p < 0.05.

3.2. The Immunohistochemical Staining Analysis of KLHL5 in CRC

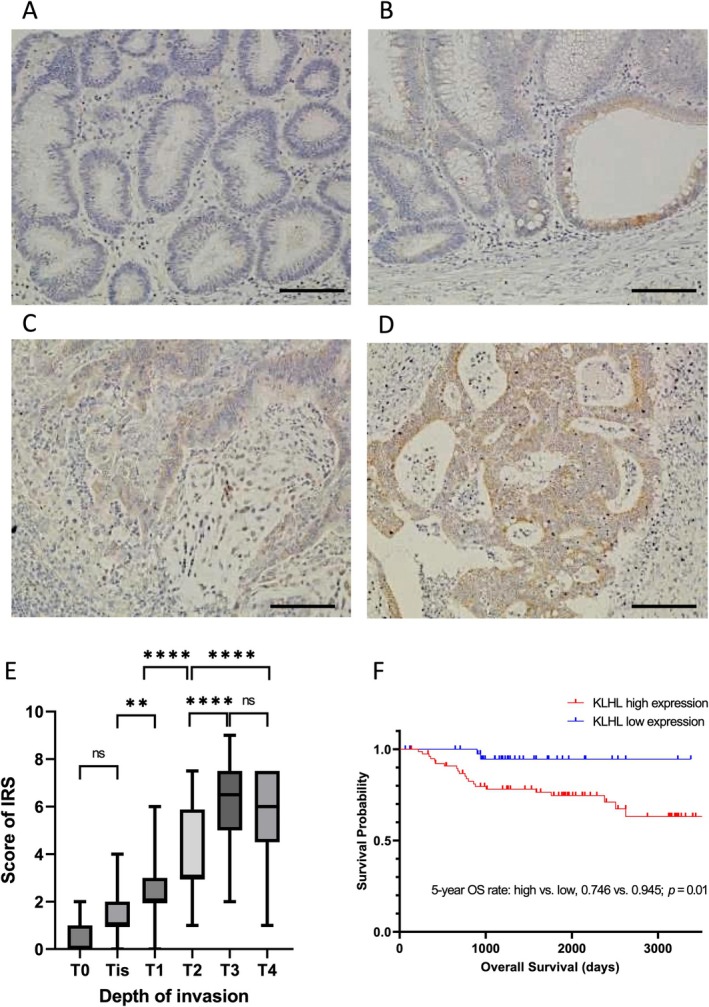

To identify the association between KLHL5 expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with colorectal neoplasm, we evaluated the expression of KLHL5 in 257 patients using immunohistochemical staining after determining the presence and specificity of the KLHL5 antibody in biological specimens using an antibody absorption test (Figure S1). A total of 257 patients were included, with a median age of 74 years (67–81), and 44.0% were female. Pathological diagnoses were reviewed from the pathology reports, including 36 (14.0%) adenomas, 31 (12.1%) non‐invasive CRCs, and 190 (73.9%) invasive CRC. CRC comprised differentiated adenocarcinoma (91.0%) and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (9.0%) (Table 1). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that KLHL5 was rarely expressed in normal mucosa and colorectal adenomas (Figure 2A). KLHL5 expression in CRC showed a trend of increasing according to the stage (Figure 2B–D). We quantified the expression of KLHL5 in colorectal neoplasms based on IRS [9] and evaluated the expression of KLHL5 at different stages of CRC. According to the expression analysis of KLHL5 using IRS, the expression of KLHL5 elevated, consistent with the CRC tumor stage (p < 0.01), but there was no significant difference between T3 and T4 (Figure 2E). To explore the prognostic value of KLHL5 in advanced CRC (T2–T4), we defined tumors with IRS > 4 as having high KLHL5 expression and tumors with IRS ≤ 4 as having low KLHL5 expression and analyzed their clinicopathological characteristics. We detected high KLHL5 expression in 63.8% (88/138) of CRC patients, and KLHL5 expression was significantly associated with several factors related to CRC progression, including the depth of invasion (p < 0.001), lymphovascular invasion (p = 0.029), and lymph node metastasis (p = 0.025). There were no significant differences in patient age, sex, or tumor location according to KLHL5 expression (Table 2). Furthermore, Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that KLHL5 expression was significantly associated with reduced overall survival (Figure 2F). We further examined whether KLHL5 expression predicted prognosis within specific pathological stages. In stage T2 CRC, high KLHL5 expression was associated with a worse overall survival (p = 0.047). No significant difference was found in T3‐stage patients (p = 0.615). In stage T4, there was no significant difference (p = 0.781), although an unexpected trend toward a better prognosis in KLHL5‐high patients was observed. However, in the combined cohort of T2–T4 cases, KLHL5‐high expression remained significantly associated with poorer overall survival (p = 0.01) (Figure S2). We also found that KLHL5 expression was heterogeneous and robust at the invasive sites of CRC specimens (Figure 3A–C). Therefore, we compared the expression of KLHL5 in the tumor center (central lesion) with the invasive site (lower lesion) of tumor tissues in advanced CRC (T2–T4) according to the IRS. The IRS score of the invasive tumor site was significantly higher than that of the tumor center in patients with advanced CRC (Figure 3D).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of colorectal cancer patients.

| Clinical characteristics | n = 257 |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median [IQR] | 74 [67–81] |

| Sex | |

| Female | 113 (44.0%) |

| Male | 144 (56.0%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Left‐sided | 138 (53.7%) |

| Right‐sided | 119 (46.3%) |

| Histological type | |

| Differentiated | 201 (78.2%) |

| Undifferentiated | 20 (7.8%) |

| Dysplasia | 36 (14.0%) |

| Depth of invasion | |

| pT0 | 36 (14.0%) |

| pTis | 31 (12.1%) |

| pT1 | 52 (20.2%) |

| pT2 | 48 (18.7%) |

| pT3 | 39 (15.2%) |

| pT4 | 51 (19.8%) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 149 (58.0%) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 67 (26.1%) |

| Distant metastasis | 27 (10.5%) |

| Pathological stage | |

| pStage 2 ≥ | 187 (72.8%) |

| pStage 3 ≤ | 70 (27.2%) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

FIGURE 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of KLHL5 in clinical samples and the quantification of KLHL5 expression in each stage of CRC. (A–D) Representative immunohistochemical images of KLHL5 staining in adenoma (A), T0 stage CRC (B), T1 stage CRC (C), and T2 stage CRC (D). Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) KLHL5 expression was quantified according to IRS in each stage of CRC (T1–T4). ns, not significant; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. (F) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival times, according to the expression level of KLHL5 in the advanced CRC (T2–T4).

TABLE 2.

KLHL5 expression levels and characteristics in colorectal cancer patients.

| IRS high (> 4) (n = 88) | IRS low (≤ 4) (n = 50) | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median [IQR] | 72 [64–78] | 74 [68–81] | 0.119 a |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 45 (51.1%) | 23 (46.0%) | 0.687 b |

| Male | 43 (48.9%) | 27 (54.0%) | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Left‐sided | 53 (60.2%) | 25 (50.0%) | 0.324 b |

| Right‐sided | 35 (39.8%) | 25 (50.0%) | |

| Histological type | |||

| Differentiated | 78 (88.6%) | 42 (84.0%) | 0.607 b |

| Undifferentiated | 10 (11.4%) | 8 (16.0%) | |

| Depth of invasion | |||

| pT2 | 14 (15.9%) | 34 (68.0%) | < 0.001 b |

| pT3 ≤ | 74 (84.1%) | 16 (32.0%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 84 (95.5%) | 42 (84.0%) | 0.029 c |

| Lymph node metastasis | 47 (53.4%) | 16 (32.0%) | 0.025 b |

| Distant metastasis | 22 (25.0%) | 5 (10.0%) | 0.056 b |

| Pathological stage | |||

| pStage 2 ≥ | 41 (46.6%) | 31 (62.0%) | 0.118 b |

| pStage 3 ≤ | 47 (53.4%) | 19 (38.0%) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; IRS, immunoreactive score; mos, months.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Chi‐squared test.

Fisher's exact test.

FIGURE 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of KLHL5 in the advanced CRC. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of KLHL5 in the advanced CRC. Scale bar, 1.0 mm. The magnified image of the central lesion of CRC (B) and the lower lesion of CRC (C). The boxes indicate the location of the magnified images. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Quantification of KLHL5 expression in the central lesion of the tumor and the lower lesion of the tumor. ****p < 0.0001.

3.3. Database Analyses of KLHL5 in CRC

To validate the expression of KLHL5 in human CRC, we performed database analysis. The Oncomine database was used to search for KLHL5 mRNA expression in colorectal neoplasms and normal tissues. Our analysis indicated that KLHL5 mRNA expression in CRC was significantly higher than that in normal tissues (Figure 4A) and that KLHL5 mRNA expression in CRC was also higher than that in colorectal adenoma (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we analyzed KLHL5 expression in normal mucosa, adenomas, and carcinomas from CRC patients who had both carcinoma and adenomatous lesions using immunohistochemical staining. KLHL5 was virtually undetectable in normal mucosa, whereas its expression was significantly increased in adenomas (p < 0.05). Importantly, expression levels in adenomas were still significantly lower than those in carcinomas (p < 0.0001), indicating progressive upregulation of KLHL5 from pre‐malignant to malignant stages (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Bioinformatic analyses of KLHL5 expression in CRC. (A, B) Expression levels of KLHL5 in normal colon and colorectal neoplastic tissues were analyzed using the Oncomine Cancer Profiling Database. (C) Immunoreactive score (IRS) of KLHL5 expression in matched tissue samples (adenoma and carcinoma) from patients with CRC. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Next, we compared KLHL5 expression among the CMS groups using transcriptome data of human CRC tissues. Notably, in six out of nine transcriptome datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus, the expression level of KLHL5 in CMS4 was significantly higher than that in the CMS1, CMS2, and CMS3 groups (Figure 5A,D–FH,I), and KLHL5 expression in CMS4 was partially higher than that in other CMS groups in the two datasets (Figure 5C,G). CMS4 cancer is highly advanced, and the overall and recurrence‐free survival rates are poor. The elevated expression of KLHL5 in CMS4 revealed by the dataset analysis, which implies KLHL5 is involved in the progression of CRC, is consistent with findings from the clinicopathological study of immunohistochemical staining and database analysis using PrognoScan and Oncomine.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of the correlation KLHL5 expression and CMS. (A‐I) The boxes represent the 25th, 50th (median), and 75th percentiles of KLHL5 mRNA expression. p‐values were calculated using the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Steel‐Dwass post hoc test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

We examined the relationships between CTNNB1 and CCNE1 mutations and KLHL5 expression. Most of the patients with a CTNNB1 mutation were not correlated with KLHL5 expression; however, KLHL5 expression KLHL5 tend to be higher in multiple patients that had several mutations in CTNNB1 (Figure S3A). Also, we performed the analysis with the CCNE1 mutation showing that there is no correlation with KLHL5 expression (Figure S3B). These results suggested that KLHL5 expression was not correlated with Wnt signaling and the cell cycle in the CRC patients. Additionally, we investigated the mutation status of KLHL5 in the TCGA‐COAD cohort. Several missense mutations were identified, but no hotspot mutation sites were observed (Figure S4A). Furthermore, there was no correlation between KLHL5 expression and mutational status (Figure S4B), suggesting that changes in KLHL5 expression are unlikely to be driven by genetic alterations in the gene itself.

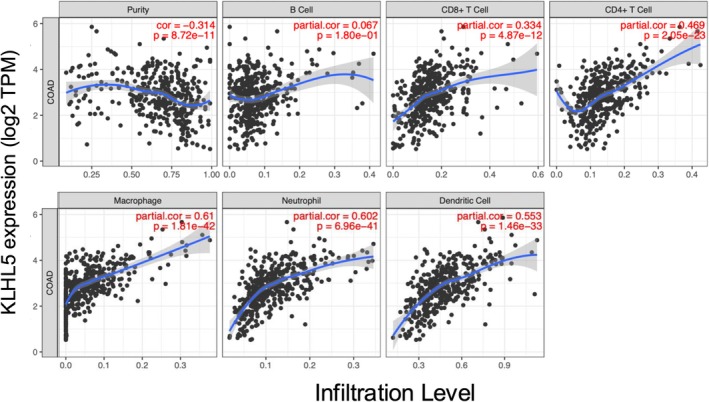

We examined the infiltration of immune cells with KLHL5 expression in the CRC patients. As a result, KLHL5 expression significantly correlated with the infiltration of macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (Figure 6). On the other hand, CUL3 expression did not correlate to the infiltration of immune cells (Figure S5). Our analysis suggested that KLHL5 expression has the potential to be a marker of lymphocyte infiltration into tumors.

FIGURE 6.

Immune cell infiltration with KLHL5 expression in the CRC patients. Estimation of Immune cell infiltration by TIMER algorithms with KLHL5 expression. Infiltrations of B cell, CD8+ T cell, CD4+ T cell, Macrophage, Neutrophil, and Dendritic cell were estimated. The purity‐corrected partial Spearman's rho value and statistical significance are shown in red.

4. Discussion

In this study, we used bioinformatics analysis to identify KLHL5 from 42 KLHL family genes as a candidate factor accounting for the progression of CRC and found that its expression was significantly higher in invasive CRC lesions through immunohistochemical staining. Furthermore, bioinformatic analyses demonstrated that KLHL5 expression was significantly associated with poor prognosis of CRC, and KLHL5 expression was higher in the specific molecular classifications of CRC, the CMS4 group, characterized by stromal infiltration, TGF‐β activation, angiogenesis [22], and worse overall and relapse‐free survival [23]. These results indicated the potential clinical impact of KLHL5 as a biomarker and target for CRC treatment.

KLHL family proteins serve as adaptors for CUL3‐based E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes, guiding proteins for degradation, and imbalances can lead to oncogenic accumulation and tumor progression [2]. They also influence key cancer‐related pathways with members such as KLHL20 [24], promoting tumor invasion, and KLHL6 mutations linked to lymphoid malignancies [25]. These genes undergo various genetic alterations in cancer, driving tumorigenesis or influencing prognosis. Their central role in protein homeostasis positions them as potential therapeutic targets, and beyond degradation, they impact processes such as transcription suppression [26], which influences cancer cell growth. Intriguingly, while some KLHL proteins may foster oncogenesis, others act as tumor suppressors, highlighting their diverse and context‐dependent roles in cancer biology [27]. In this study, we identified KLHL5, based on its differential expression levels and variation between CRC patients in TCGA‐COAD cohorts, as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target.

KLHL5 is a member of the Kelch‐like family of proteins and is involved in various cellular processes such as signal transduction, protein degradation, and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. The specific function of KLHL5 in cancer cells is not well understood; however, previous reports have demonstrated its overexpression in various cancers, including breast, lung, and liver cancers, and KLHL5 is associated with more aggressive forms of cancer [28]. Schleifer et al. have previously reported that KLHL5 knockdown attenuated renal cell carcinoma and ovarian carcinoma cells' proliferation and viability [29]. They also showed that KLHL5 knockdown sensitized cancer cells to anticancer drugs, including cell cycle inhibitors and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors. These results imply that KLHL5 regulates the signaling pathways that promote cancer development and progression. KLHL5 is an adaptor protein of Cul3; therefore, exploring Cul3/KLHL5 ubiquitin ligase substrates is important to elucidate the mechanism by which KLHL5 is involved in CRC progression. Sphingosine kinase 1 (SPHK1) has been identified as a substrate for Cul3/KLHL5 ubiquitin ligase [30]. SPHK1 is upregulated in some cancers and contributes to cancer cell survival, proliferation, and migration, promoting angiogenesis by catalyzing the formation of sphingosine 1‐phosphate [31]. Additional studies are required to determine whether SPHK1 is a key molecule in regulating CRC progression by KLHL5.

Immunohistochemical staining showed that KLHL5 was expressed in CRC, and its expression increased with tumor progression (Figure 2E). KLHL5 expression in advanced CRC significantly correlated with overall survival (Figure 2F). These results indicated that KLHL5 is a valuable prognostic marker for CRC. Moreover, KLHL5 expression was heterogeneous and more robustly expressed in invasive lesions than in the central layer of the tumor (Figure 3D). The invasive front of CRC is a crucial region for investigating its pathophysiology. Tumor budding in this region has been reported to be linked to patient prognosis [32], and molecular changes at the invasive front are known to affect tumor budding and patient outcomes [33, 34]. The importance of stromal components at the invasive front in CRC prognosis has also been reported [35]. Although the mechanisms underlying KLHL5 function in the invasive region were not sufficiently clarified in this study, our data imply that KLHL5 has an impact on the biological behavior of CRC at invasive sites that promote CRC progression.

Using bioinformatics analyses, previous studies have demonstrated that KLHL5 expression is related to clinical outcomes in several types of cancers, including gastric cancer and CRC [28]. They focused on the implication of KLHL5 in gastric cancer and indicated that its expression is significantly correlated with the patient node stage, infiltration, and expression of multiple immune marker sets. We evaluated the significance of KLHL5 in CRC using bioinformatic analysis and obtained similar results to their analyses that KLHL5 is involved in the poor prognosis of CRC (Figure 1B,C). Additionally, we investigated the association between KLHL5 and consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) of CRC using bioinformatics analysis. CMS is a classification system that categorizes CRC tumors based on their gene expression profile [22]. There are four CMS subtypes: CMS1 (immune), CMS2 (canonical), CMS3 (metabolic), and CMS4 (mesenchymal). Each subtype exhibits distinct molecular and clinical characteristics. In the current study, KLHL5 expression in CMS4 was significantly higher than that in normal colorectal tissue using TCGA database analysis (Figure 1D), and six of the nine database analyses showed that KLHL5 was significantly highly expressed in CMS4 compared with other subtypes (Figure 5). There are several possible reasons for these inconsistent results, including the sample volume, different data collection methods, diversified molecular functions, and intertumoral heterogeneity. However, our results indicate a strong connection between CMS4 and KLHL5. In a clinical setting, patients with CMS4 CRC often have the worst prognosis among the four subtypes. This subtype is generally associated with advanced disease, higher tumor grade, and greater likelihood of distant metastases at the time of diagnosis. These characteristics of CMS4 were observed in CRC with high KLHL5 expression in our pathological examination, which also supports a connection between KLHL5 and CMS4. Biologically, CMS4 tumors exhibit a high level of matrix remodeling, indicative of an invasive phenotype, with activated TGF‐β signaling, stromal infiltration, and heightened angiogenesis compared to other groups [22, 36]. Given their stromal‐rich profile and links to angiogenesis and inflammation, targeted therapies, such as angiogenesis inhibitors or those targeting the tumor microenvironment, may offer promising treatment options for CMS4 tumors. While our immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated a clear upregulation of KLHL5 from normal mucosa to adenoma and carcinoma, the increase observed in the TCGA‐COAD dataset, particularly in the CMS4 subtype, was relatively modest. This discrepancy may be attributed to tumor heterogeneity, variable tumor purity, and the high stromal content characteristic of CMS4 tumors [23, 37], all of which can influence bulk RNA‐seq signals. Despite this, the consistent trend across multiple datasets and validation by protein‐level analysis in clinical specimens supports the conclusion that KLHL5 is upregulated during colorectal tumor progression. Moreover, KLHL5 expression was enriched in CMS4, a subtype associated with mesenchymal features, stromal infiltration, and poor clinical outcomes. Although the mechanisms underlying KLHL5 upregulation in CMS4 remain unclear, its selective expression pattern suggests a potential role in the aggressive biology of this subtype. Additional research is necessary to determine whether KLHL5 actively drives CMS4‐related tumor behavior or simply reflects the molecular profile of this subtype.

We also explored the relationship between KLHL5 expression and key genetic alterations commonly observed in CRC. Although a subset of patients with multiple CTNNB1 mutations showed slightly elevated KLHL5 expression, no consistent correlation was observed between KLHL5 and mutations in either CTNNB1 or CCNE1, which are genes associated with Wnt signaling and cell cycle pathways, respectively. These findings suggest that KLHL5 expression is regulated independently of these canonical oncogenic pathways. Furthermore, we identified several missense mutations in KLHL5; however, no hotspot mutations were found, and KLHL5 expression did not correlate with its mutational status. These findings support the notion that KLHL5 expression is not driven by common oncogenic mutations in CRC and may be regulated by other transcriptional or tumor microenvironmental factors.

In this study, immunohistochemical staining and bioinformatics analyses revealed clinicopathological characteristics of CRC expressing KLHL5; in brief, the involvement of KLHL5 in CRC development and progression. Although our data collectively indicate the oncogenic involvement of KLHL5 in CRC, the exact mechanism by which KLHL5 contributes to the development and progression of CRC is not yet fully understood. Further studies are needed to determine the clinical utility of KLHL5 as a biomarker and target for CRC treatment; however, our data provide the potential clinical significance of KLHL5 in CRC.

Author Contributions

Konomu Uno: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Hirotada Nishie: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing. Hiromi Hiyoshi: formal analysis, investigation. Kyosuke Habu: writing – review and editing. Jun Nakayama: formal analysis, investigation, writing – review and editing. Sota Tate: writing – review and editing. Tomohisa Sakaue: writing – review and editing. Eiji Kubota: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – review and editing. Mamoru Tanaka: writing – review and editing. Takaya Shimura: writing – review and editing. Hiromi Kataoka: supervision, writing – review and editing. Takashi Joh: resources, supervision, writing – review and editing. Shigeki Higashiyama: supervision, writing – review and editing.

Ethics Statement

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: The Research Ethics Board of Nagoya City University (no. 60‐18‐0105) approved this study.

Consent

The opt‐out method was applied to obtain consent for this study by displaying it on the homepage of Nagoya City University Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

Shigeki Higashiyama is Associate Editor of Cancer Science. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. KLHL5 antibody absorption test.

Figure S2. Stage‐specific survival analysis based on KLHL5 expression in CRC patients.

Figure S3. Mutation profiles of CTNNB1 and CCNE1 with KLHL5 expression in the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.

Figure S4. Mutation profiles of KLHL5 in the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.

Figure S5. Immune cell infiltration with CUL3 expression in the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mrs. Yukimi Ito from Nagoya City University for her technical assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI grant number 17K09357).

References

- 1. Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R. L., et al., “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71, no. 3 (2021): 209–249, 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dhanoa B. S., Cogliati T., Satish A. G., Bruford E. A., and Friedman J. S., “Update on the Kelch‐Like (KLHL) Gene Family,” Human Genomics 7, no. 1 (2013): 13, 10.1186/1479-7364-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams J., Kelso R., and Cooley L., “The Kelch Repeat Superfamily of Proteins: Propellers of Cell Function,” Trends in Cell Biology 10, no. 1 (2000): 17–24, 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01673-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang P., Song J., and Ye D., “CRL3s: The BTB‐CUL3‐RING E3 Ubiquitin Ligases,” Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1217 (2020): 211–223, 10.1007/978-981-15-1025-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deng L., Meng T., Chen L., Wei W., and Wang P., “The Role of Ubiquitination in Tumorigenesis and Targeted Drug Discovery,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 5, no. 1 (2020): 11, 10.1038/s41392-020-0107-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maekawa M., Hiyoshi H., Nakayama J., et al., “Cullin‐3/KCTD10 Complex Is Essential for K27‐Polyubiquitination of EIF3D in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 516, no. 4 (2019): 1116–1122, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maekawa M., Tanigawa K., Sakaue T., et al., “Cullin‐3 and Its Adaptor Protein ANKFY1 Determine the Surface Level of Integrin β1 in Endothelial Cells,” Biology Open 6, no. 11 (2017): 1707–1719, 10.1242/bio.029579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakaue T., Fujisaki A., Nakayama H., et al., “Neddylated Cullin 3 Is Required for Vascular Endothelial‐Cadherin‐Mediated Endothelial Barrier Function,” Cancer Science 108, no. 2 (2017): 208–215, 10.1111/cas.13133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Remmele W. and Stegner H. E., “Recommendation for Uniform Definition of an Immunoreactive Score (IRS) for Immunohistochemical Estrogen Receptor Detection (ER‐ICA) in Breast Cancer Tissue,” Pathologe 8, no. 3 (1987): 138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skrzypczak M., Goryca K., Rubel T., et al., “Modeling Oncogenic Signaling in Colon Tumors by Multidirectional Analyses of Microarray Data Directed for Maximization of Analytical Reliability,” PLoS One 5, no. 10 (2010): 13091, 10.1371/journal.pone.0013091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jorissen R. N., Gibbs P., Christie M., et al., “Metastasis‐Associated Gene Expression Changes Predict Poor Outcomes in Patients With Dukes Stage B and C Colorectal Cancer,” Clinical Cancer Research 15, no. 24 (2009): 7642–7651, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith J. J., Deane N. G., Wu F., et al., “Experimentally Derived Metastasis Gene Expression Profile Predicts Recurrence and Death in Patients With Colon Cancer,” Gastroenterology 138, no. 3 (2010): 958–968, 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freeman T. J., Smith J. J., Chen X., et al., “Smad4‐Mediated Signaling Inhibits Intestinal Neoplasia by Inhibiting Expression of Beta‐Catenin,” Gastroenterology 142, no. 3 (2012): 562–571.e562, 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mizuno H., Kitada K., Nakai K., and Sarai A., “PrognoScan: A New Database for Meta‐Analysis of the Prognostic Value of Genes,” BMC Medical Genomics 2 (2009): 18, 10.1186/1755-8794-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jorissen R. N., Lipton L., Gibbs P., et al., “DNA Copy‐Number Alterations Underlie Gene Expression Differences Between Microsatellite Stable and Unstable Colorectal Cancers,” Clinical Cancer Research 14, no. 24 (2008): 8061–8069, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Sousa E. M. F., Colak S., Buikhuisen J., et al., “Methylation of Cancer‐Stem‐Cell‐Associated Wnt Target Genes Predicts Poor Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer Patients,” Cell Stem Cell 9, no. 5 (2011): 476–485, 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schlicker A., Beran G., Chresta C. M., et al., “Subtypes of Primary Colorectal Tumors Correlate With Response to Targeted Treatment in Colorectal Cell Lines,” BMC Medical Genomics 5 (2012): 66, 10.1186/1755-8794-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laibe S., Lagarde A., Ferrari A., et al., “A Seven‐Gene Signature Aggregates a Subgroup of Stage II Colon Cancers With Stage III,” OMICS 16, no. 10 (2012): 560–565, 10.1089/omi.2012.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marisa L., de Reynies A., Duval A., et al., “Gene Expression Classification of Colon Cancer Into Molecular Subtypes: Characterization, Validation, and Prognostic Value,” PLoS Medicine 10, no. 5 (2013): e1001453, 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eide P. W., Bruun J., Lothe R. A., and Sveen A., “CMScaller: An R Package for Consensus Molecular Subtyping of Colorectal Cancer Pre‐Clinical Models,” Scientific Reports 7, no. 1 (2017): 16618, 10.1038/s41598-017-16747-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li T., Fan J., Wang B., et al., “TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor‐Infiltrating Immune Cells,” Cancer Research 77, no. 21 (2017): e108–e110, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guinney J., Dienstmann R., Wang X., et al., “The Consensus Molecular Subtypes of Colorectal Cancer,” Nature Medicine 21, no. 11 (2015): 1350–1356, 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ten Hoorn S., de Back T. R., Sommeijer D. W., and Vermeulen L., “Clinical Value of Consensus Molecular Subtypes in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 114, no. 4 (2022): 503–516, 10.1093/jnci/djab106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan W. C., Lee Y. R., Huang S. F., et al., “A Cullin3‐KLHL20 Ubiquitin Ligase‐Dependent Pathway Targets PML to Potentiate HIF‐1 Signaling and Prostate Cancer Progression,” Cancer Cell 20, no. 2 (2011): 214–228, 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi J., Zhou N., and Busino L., “KLHL6 Is a Tumor Suppressor Gene in Diffuse Large B‐Cell Lymphoma,” Cell Cycle 18, no. 3 (2019): 249–256, 10.1080/15384101.2019.1568765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Melnick A., Ahmad K. F., Arai S., et al., “In‐Depth Mutational Analysis of the Promyelocytic Leukemia Zinc Finger BTB/POZ Domain Reveals Motifs and Residues Required for Biological and Transcriptional Functions,” Molecular and Cellular Biology 20, no. 17 (2000): 6550–6567, 10.1128/MCB.20.17.6550-6567.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ye G., Wang J., Yang W., Li J., Ye M., and Jin X., “The Roles of KLHL Family Members in Human Cancers,” American Journal of Cancer Research 12, no. 11 (2022): 5105–5139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu Q., Yin G., Lei J., Tian J., Lan A., and Liu S., “KLHL5 Is a Prognostic‐Related Biomarker and Correlated With Immune Infiltrates in Gastric Cancer,” Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 7 (2020): 599110, 10.3389/fmolb.2020.599110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schleifer R. J., Li S., Nechtman W., et al., “KLHL5 Knockdown Increases Cellular Sensitivity to Anticancer Drugs,” Oncotarget 9, no. 100 (2018): 37429–37438, 10.18632/oncotarget.26462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Powell J. A., Pitman M. R., Zebol J. R., et al., “Kelch‐Like Protein 5‐Mediated Ubiquitination of Lysine 183 Promotes Proteasomal Degradation of Sphingosine Kinase 1,” Biochemical Journal 476, no. 21 (2019): 3211–3226, 10.1042/BCJ20190245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pyne N. J., El Buri A., Adams D. R., and Pyne S., “Sphingosine 1‐Phosphate and Cancer,” Advances in Biological Regulation 68 (2018): 97–106, 10.1016/j.jbior.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koelzer V. H., Zlobec I., Berger M. D., et al., “Tumor Budding in Colorectal Cancer Revisited: Results of a Multicenter Interobserver Study,” Virchows Archiv 466, no. 5 (2015): 485–493, 10.1007/s00428-015-1740-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zlobec I., Bihl M. P., Foerster A., Rufle A., and Lugli A., “The Impact of CpG Island Methylator Phenotype and Microsatellite Instability on Tumour Budding in Colorectal Cancer,” Histopathology 61, no. 5 (2012): 777–787, 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamada N., Sugai T., Eizuka M., et al., “Tumor Budding at the Invasive Front of Colorectal Cancer May Not Be Associated With the Epithelial‐Mesenchymal Transition,” Human Pathology 60 (2017): 151–159, 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mesker W. E., Junggeburt J. M., Szuhai K., et al., “The Carcinoma‐Stromal Ratio of Colon Carcinoma Is an Independent Factor for Survival Compared to Lymph Node Status and Tumor Stage,” Cellular Oncology 29, no. 5 (2007): 387–398, 10.1155/2007/175276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Becht E., de Reynies A., Giraldo N. A., et al., “Immune and Stromal Classification of Colorectal Cancer Is Associated With Molecular Subtypes and Relevant for Precision Immunotherapy,” Clinical Cancer Research 22, no. 16 (2016): 4057–4066, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Calon A., Lonardo E., Berenguer‐Llergo A., et al., “Stromal Gene Expression Defines Poor‐Prognosis Subtypes in Colorectal Cancer,” Nature Genetics 47, no. 4 (2015): 320–329, 10.1038/ng.3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. KLHL5 antibody absorption test.

Figure S2. Stage‐specific survival analysis based on KLHL5 expression in CRC patients.

Figure S3. Mutation profiles of CTNNB1 and CCNE1 with KLHL5 expression in the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.

Figure S4. Mutation profiles of KLHL5 in the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.

Figure S5. Immune cell infiltration with CUL3 expression in the COAD‐TCGA cohorts.