Abstract

The evolutionarily conserved p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade is an integral part of the response to a variety of environmental stresses. Here we show that the Caenorhabditis elegans PMK-1 p38 MAPK pathway regulates the oxidative stress response via the CNC transcription factor SKN-1. In response to oxidative stress, PMK-1 phosphorylates SKN-1, leading to its accumulation in intestine nuclei, where SKN-1 activates transcription of gcs-1, a phase II detoxification enzyme gene. These results delineate the C. elegans p38 MAPK signaling pathway leading to the nucleus that responds to oxidative stress.

Keywords: C. elegans, oxidative stress, p38 MAP kinase, SKN-1

Oxidative stress contributes to the etiology of various degenerative diseases such as ischemia and the process of aging. In vertebrates, a major mechanism of oxidative stress defense is orchestrated by the two NF-E2-related factors Nrf1 and Nrf2, which belong to the Cap-N-Collar (CNC) family of transcription factors (Hayes and McMahon 2001; Motohashi and Yamamoto 2004; Xu et al. 2005). Nrf proteins induce expression of a battery of phase II detoxification enzymes. Nrf proteins accumulate in cell nuclei in response to oxidative stress. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the SKN-1 protein is required for oxidative stress resistance (An and Blackwell 2003). SKN-1 is distantly related to the Nrf proteins and induces phase II detoxification gene transcription. Oxidative stress induces SKN-1 to accumulate in intestinal nuclei. This oxidative stress response thus appears to be widely conserved.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways serve as transducers of extracellular stimuli that allow cellular adaptation to changes in the environment. The p38 MAPKs are an evolutionary conserved subfamily of MAPKs that play an important role in adaptation, homeostasis, and specialized stress responses. Studies in vertebrate cell culture systems implicate the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in the response of cells to a variety of stresses and inflammatory cytokines at the cellular level (Chang and Karin 2001; Kyriakis and Avruch 2001; Johnson and Lapadat 2002). However, there has been relatively little research into the role of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in stress response in whole animals. In this study, we have taken a genetic approach to define the role of the p38 MAPK pathway in the C. elegans oxidative stress response, as a model system for stress-induced signal transduction.

Results and Discussion

The C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway is involved in the oxidative stress response

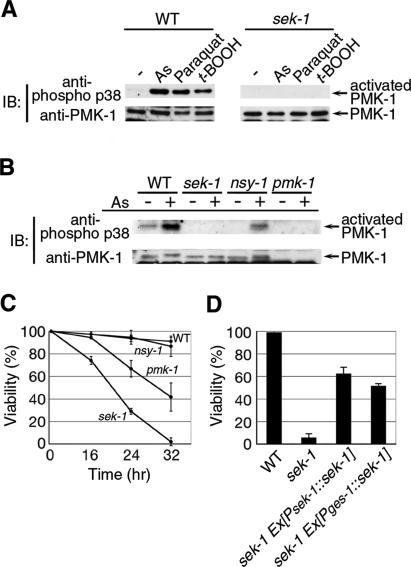

Mammalian p38 is activated in response to stress stimuli (Chang and Karin 2001; Kyriakis and Avruch 2001; Johnson and Lapadat 2002). Thus, we first investigated whether oxidative stress activates p38 MAPK in C. elegans. Western blot analysis using an anti-phospho p38 antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated, activated form of p38 MAPK (Kim et al. 2002) revealed that p38 MAPK was activated by treatment with sodium arsenite, paraquat, and t-butyl peroxide, with arsenite being the most potent (Fig. 1A). Animals harboring the pmk-1 deletion mutation exhibited diminished levels of PMK-1 protein and arsenite-induced p38 MAPK activation (Fig. 1B). This indicates that oxidative stress activates PMK-1 in C. elegans.

Figure 1.

The PMK-1 pathway regulated by stress response. (A,B) Activation of PMK-1 by oxidative stress. Animals were treated with oxidative stress agents. Extracts prepared from each animal were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-phospho p38 and anti-PMK-1. (t-BOOH) t-butyl peroxide. (C,D) Stress sensitivity in mutants. (C) Animals were scored for survival following exposure to sodium arsenite (5 mM) in M9 buffer for the indicated times. (D) Wild-type (N2) and sek-1 mutant animals harboring control vector or transgene as an extrachromosomal array were scored for survival after they had been placed in M9 containing sodium arsenite (5 mM) for 24 h.

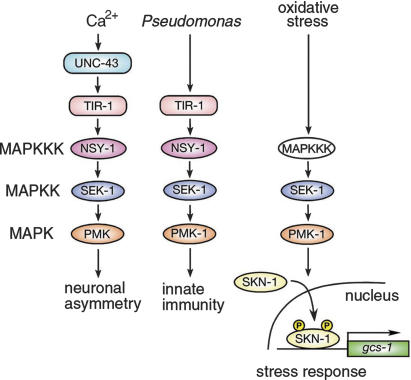

We have recently shown that the C. elegans p38 MAPK is regulated by SEK-1 MAPKK and NSY-1 MAPKKK (Sagasti et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2002; Tanaka-Hino et al. 2002). The NSY-1–SEK-1–p38 pathway determines asymmetric cell fate decision during neuronal development (Sagasti et al. 2001; Tanaka-Hino et al. 2002) and mediates the nematode defense against pathogens (Kim et al. 2002). UNC-43, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, acts upstream of NSY-1 in the former pathway (Sagasti et al. 2001) but is not involved in the innate immunity pathway (Kim et al. 2002). Therefore, we next asked whether arsenite-induced PMK-1 activation is mediated by the NSY-1–SEK-1 pathway. Wild-type, sek-1, and nsy-1 mutant animals were treated with arsenite and examined for PMK-1 activation. Significantly, we found that activation of PMK-1 in response to arsenite was markedly reduced in sek-1 mutants compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 1B). The sek-1 mutation was also defective in PMK-1 activation by paraquat and t-butyl peroxide (Fig. 1A). These findings indicate that SEK-1 MAPKK is an essential upstream activator of PMK-1 in response to oxidative stress. In contrast, activation of PMK-1 in response to arsenite was partially reduced in nsy-1 mutants (Fig. 1B), suggesting that redundant signaling molecules, probably other MAPKKK members, may also participate in the process. Furthermore, the unc-43 loss-of-function mutation was found to have no effect on arsenite-induced PMK-1 activation (data not shown). These results suggest that the upstream components of SEK-1 that mediate stress-dependent activation of PMK-1 are different from the upstream components mediating neuronal asymmetric development and innate immunity.

We next asked whether the SEK-1–PMK-1 pathway is in fact important in protecting the nematode against oxidative stress. We found that the sek-1 mutant animals were hypersensitive to arsenite, whereas the nsy-1 mutants displayed the same sensitivity as wild type to arsenite (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the sek-1 mutant animals were dramatically sensitive to paraquat and t-butyl peroxide (data not shown). Thus, there is a close correlation between the strength of PMK-1 activation and the sensitivity of the animal to oxidative stress. However, pmk-1 mutants were partially sensitive to arsenite (Fig. 1C). Although C. elegans has two p38 MAPK orthologs, pmk-1 and pmk-2 (Berman et al. 2001), RNAi to inhibit pmk-2 expression did not enhance the arsenite sensitivity of pmk-1 mutants (data not shown). It is at present unclear which MAPKs function redundantly with PMK-1 in the stress response pathway.

The hypersensitivity of sek-1 mutant animals to arsenite could be significantly suppressed by reintroduction of the wild-type sek-1 gene as an extrachromosomal transgene (Fig. 1D). In C. elegans, oxidative stress regulates gene expression in the intestine (An and Blackwell 2003). To test whether expression of sek-1 in the intestine is sufficient to rescue arsenite hypersensitivity, we expressed sek-1 under the control of the intestine-specific ges-1 promoter (Egan et al. 1995). When a plasmid containing the Pges-1::sek-1 transgene was introduced as an extrachromosomal array into sek-1 mutant animals, we found that arsenite hypersensitivity was partially rescued (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that SEK-1 function in the intestine is necessary, but not sufficient for the protection of animals against oxidative stress.

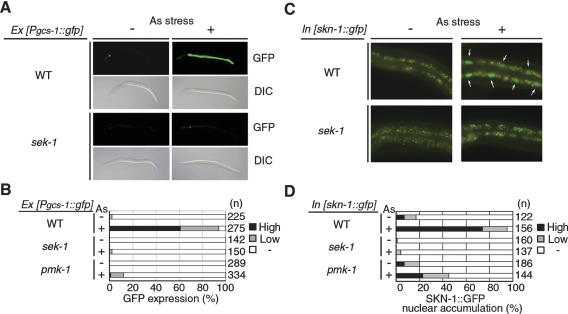

In C. elegans, oxidative stress induces expression in the intestine of gcs-1, a gene encoding the phase II detoxification enzyme, γ-glutamine cysteine synthase heavy chain (An and Blackwell 2003). To determine whether stress-dependent gcs-1 gene activation in the intestine is mediated by the p38 MAPK pathway, we generated a strain containing a gcs-1 promoter::GFP (green fluorescent protein) transgene: Pgcs-1::gfp (An and Blackwell 2003). When raised in the absence of arsenite, Pgcs-1::gfp animals exhibited little GFP expression in the intestine (Fig. 2A,B). However, intestinal GFP expression dramatically increased in Pgcs-1::gfp animals following exposure to arsenite. In contrast, in sek-1 and pmk-1 mutants, the induction of Pgcs-1::gfp in intestine was dramatically lower (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, in the sek-1 background, gcs-1 induction in the intestine in response to paraquat and t-butyl peroxide was also impaired (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results suggest that oxidative stress leads to the induction of gcs-1 transcription in the intestine through the activation of the p38 MAPK signaling cascade.

Figure 2.

Stress-induced gcs-1 expression and SKN-1 localization. (A,B) Effect of the PMK-1 pathway on stress-induced gcs-1 expression. Animals harboring the Pgcs-1::gfp transgene as an extrachromosomal array were treated with sodium arsenite (5 mM) for 1 h. These animals were then transferred to NGM plates and incubated for 3 h. Nomarski (DIC) and fluorescent (GFP) views are shown in A. (B) Percentages of animals in each expression category are listed. Low refers to animals in which intestinal GFP was present at high levels anteriorly and posteriorly, but was not detected in between. High indicates that a GFP was present at high levels throughout most of the intestine. (C,D) Effect of the PMK-1 pathway on stress-induced SKN-1 localization. Animals integrated with the skn-1::gfp transgene were treated with sodium arsenite (5 mM) for 1 h. Fluorescent views are shown in C. Accumulation of SKN-1::GFP in intestinal cell nuclei is indicated by arrows. (D) Percentages of animals in each expression category are listed. Low refers to animals in which SKN-1::GFP was barely detectable in intestinal nuclei. High indicates that a strong SKN-1::GFP signal was present in all intestinal nuclei.

p38 MAPK pathway regulates the nuclear localization of SKN-1 in response to oxidative stress

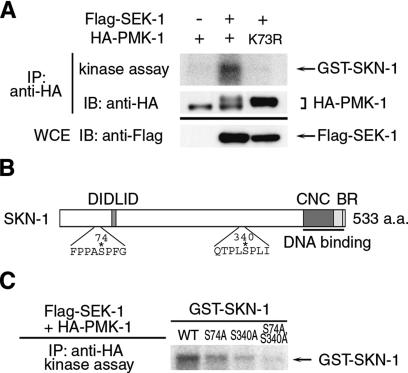

The induction of gcs-1 expression in the intestine in response to oxidative stress is mediated by the transcription factor SKN-1 (An and Blackwell 2003). This raised the possibility that SKN-1 may be a downstream target of the p38 MAPK stress response pathway in C. elegans. To examine this possibility, we tested SKN-1 as a PMK-1 substrate. We produced a GST–SKN-1 fusion protein in bacteria and tested its ability to be phosphorylated in vitro. HEK293 cells were transfected with a mammalian expression vector encoding an HA-tagged PMK-1. HA-PMK-1 was then immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and tested for in vitro phosphorylation of GST–SKN-1. HA-PMK-1 exhibited a basal kinase activity and failed to phosphorylate GST–SKN-1 (Fig. 3A, lane 1). Coexpression of HA-PMK-1 with SEK-1 in HEK293 cells induces phosphorylation of the coexpressed PMK-1, resulting in strong activation of PMK-1 (Tanaka-Hino et al. 2002). When this activated PMK-1 was tested in the in vitro kinase assay, it was found to efficiently phosphorylate GST–SKN-1 (Fig. 3A, lane 2). SKN-1 phosphorylation by PMK-1 required the presence of active PMK-1 in the immune complex, since a kinase-inactive form of PMK-1, coexpressed with SEK-1, was unable to phosphorylate the SKN-1 protein (Fig. 3A, lane 3). These results suggest that SKN-1 functions as a direct target of the PMK-1. The primary amino acid sequences of SKN-1 contain potential MAPK phosphorylation sites at Ser-74 and Ser-340 (Fig. 3B). To determine whether PMK-1 phosphorylates SKN-1 at these residues, we tested mutants of SKN-1 in which either or both residues were substituted with Ala. The S74A and the S340A mutants were weakly phosphorylated by PMK-1, while the S74, 340A mutant was not phosphorylated at all (Fig. 3C). Thus, PMK-1 directly phosphorylates SKN-1 at Ser-74 and Ser-340.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation of SKN-1. (A,C) Phosphorylation of SKN-1 by PMK-1. HEK293 cells were transfected with control vector (-), HA-PMK-1, HA-PMK-1(K73R), and Flag-SEK-1 as indicated. Complexes immunoprecipitated with anti-HA were used for in vitro kinase reactions with GST–SKN-1. The amounts of immunoprecipitated HA-PMK-1 were determined with anti-HA. Expression of Flag-SEK-1 was determined by immunoblotting with anti-Flag in whole-cell extracts (WCEs). (B) Amino acid sequence of SKN-1 containing the putative MAPK phosphorylation sites. The phosphorylation sites are indicated by asterisks. (CNC) Cap-N-Collar domain; (BR) basic region.

It is known that oxidative stress induces SKN-1 to be relocalized from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in C. elegans (An and Blackwell 2003). We determined whether arsenite stress could also induce nuclear localization of SKN-1 in the intestine, using a transgene in which GFP is fused to the C terminus of full-length SKN-1 (An and Blackwell 2003). In larvae and young adults, SKN-1::GFP was usually absent in intestinal nuclei. After exposure to arsenite, elevated levels of SKN-1::GFP appeared in intestinal cell nuclei in a high percentage of animals (Fig. 2C,D). To address whether the nuclear translocation of SKN-1::GFP could be regulated by the p38 MAPK pathway, we examined the effect of the sek-1 and pmk-1 mutations on the SKN-1 localization. Arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation of SKN-1::GFP was drastically decreased in sek-1 and pmk-1 mutants (Fig. 2C,D), indicating that relocalization following arsenite stress involves the PMK-1 pathway. Nuclear localization of SKN-1 is regulated through constitutive and stress-inducible mechanisms in the ASI chemosensory neurons and intestine, respectively (An and Blackwell 2003). The sek-1 mutant exhibited no change in the location or the intensity of SKN-1::GFP in the ASI neurons (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, the PMK-1 pathway is required for an inducible response in one tissue but not for constitutive regulation of SKN-1 in a different context. Taken together, these results suggest that oxidative stress activates the PMK-1 pathway and promotes nuclear accumulation of SKN-1 in the intestine, leading to activation of stress-induced genes such as gcs-1.

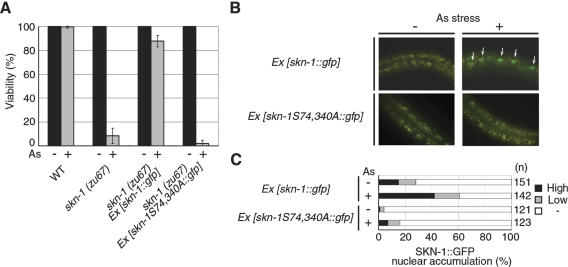

We next investigated the role of skn-1 in arsenite resistance in C. elegans. skn-1(zu67) homozygotes produce normal numbers of offspring with normal timing, and as young adults, these mutants are not obviously distinguishable in morphology from wild type (An and Blackwell 2003). However, the skn-1(zu67) mutant animals exhibited markedly decreased survival in the presence of arsenite (Fig. 4A), indicating that the skn-1 gene is required for resistance to arsenite stress. The hypersensitivity of skn-1 mutant animals to arsenite could be significantly rescued by reintroduction of the wild-type skn-1 gene as an extrachromosomal transgene (Fig. 4A). To address the biological importance of PMK-1 phosphorylation, we introduced into skn-1 mutant animals a GFP fusion to the skn-1(S74, 340A) mutant. Whereas the wild-type form of SKN-1 was found predominantly in the nucleus in animals exposed to arsenite, SKN-1(S74, 340A)::GFP was found exclusively in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4B,C). Furthermore, skn-1(zu67) mutant animals bearing the skn-1(S74, 340A) gene exhibited enhanced sensitivity to arsenite (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that SKN-1 phosphorylation on two Ser residues by PMK-1 is a crucial aspect of skn-1 gene function and a pivotal point of regulation.

Figure 4.

Effects of SKN-1 phosphorylation. (A) Effect of the skn-1(S74, 340A) mutation on arsenate sensitivity. skn-1(zu67) mutant animals with control vector or transgene as an extrachromosomal array were scored for survival after they had been placed in M9 containing sodium arsenate (3 mM) for 24 h. (B,C) Effect of the skn-1 mutation on stress-induced SKN-1 localization. Wild-type (N2) or sek-1 mutant animals harboring the skn-1::gfp transgene as an extrachromosomal array were treated with sodium arsenate (5 mM) for 1 h. Fluorescent views are shown in B. Accumulation of SKN-1::GFP in intestinal cell nuclei is indicated by arrows. (C) Percentages of animals in each expression category are listed.

We next asked whether oxidative stress increases the total protein levels of SKN-1 and whether PMK-1-dependent phosphorylation of SKN-1 is involved in its protein stability. We analyzed the SKN-1::GFP proteins in wild-type animals carrying the skn-1::gfp transgene as an extrachromosomal array by immunoblotting before and after arsenite treatment. Arsenite treatment increased the levels of SKN-1::GFP proteins (Supplementary Fig. S3). This arsenite-induced accumulation of SKN-1::GFP was still observed in sek-1 mutants carrying the skn-1::gfp transgene, indicating that the PMK-1 pathway does not regulate the protein stability of SKN-1.

The nuclear accumulation of SKN-1 in response to arsenite stress could be caused by decreased nuclear export or an increased import. To determine whether SKN-1 is regulated by a nuclear export mechanism, we perturbed nuclear export by targeting CRM-1, the C. elegans ortholog of a vertebrate exportin (Lo et al. 2004), using RNAi. Depletion of CRM-1 by RNAi in wild-type animals expressing SKN-1::GFP did not result in increased nuclear localization of SKN-1 in the absence of oxidative stress (J.H. An and T.K. Blackwell, unpubl.). Furthermore, treatment of sek-1 mutants expressing SKN-1::GFP with crm-1 RNAi did not induce nuclear accumulation of SKN-1 even in the presence of arsenite stress (data not shown). We next analyzed the nuclear localization of a SKN-1 protein to which the SV40 nuclear localization signal (NLS) had been added. Addition of the SV40 NLS to SKN-1::GFP failed to promote nuclear localization of SKN-1 in sek-1 mutants in response to arsenite stress (data not shown). These results suggest that PMK-1 phosphorylation of SKN-1 may not effect nuclear localization through the nuclear import/export machinery.

To gain insight into the mechanism(s) underlying the nuclear localization of SKN-1 in response to oxidative stress, we analyzed the subcellular distribution of SKN-1 in mammalian cells. When Flag-tagged SKN-1 was expressed in HeLa cells, SKN-1 was localized in the nucleus even in the absence of any stresses (Supplementary Fig. S4). This indicates that SKN-1 can be constitutively localized in the nucleus in mammalian cells. Taken together, these results raise the possibility that the cells in the intestine of C. elegans harbor an inhibitor that acts to sequester SKN-1 in the cytoplasm and that phosphorylation of SKN-1 by PMK-1 leads to the release of SKN-1 from this inhibitor and the nuclear accumulation of SKN-1. SKN-1 is distantly related to the Nrf proteins (Walker et al. 2000), which orchestrate the major oxidative stress response in vertebrates (Hayes and McMahon 2001). Interestingly, mammalian Nrf proteins are also regulated in response to oxidative stress by a cytoplasmic retention mechanism (Itoh et al. 1999). Our findings on the regulation of SKN-1 by PMK-1-mediated phosphorylation may reflect modes of p38 MAPK signaling conserved through the Nrf proteins.

The PMK-1 p38 MAPK pathway is further involved in asymmetric cell fate in neuronal development (Sagasti et al. 2001; Tanaka-Hino et al. 2002), the nematode defense to pathogens (Kim et al. 2002), and the stress response (Fig. 5). Most recently, it has been shown that the tir-1 gene encoding a highly conserved Toll/IL-1 resistance (TIR) domain protein is required for C. elegans resistance to microbial pathogens (Couillault et al. 2004; Liberati et al. 2004) and asymmetric cell fate decision during neuronal development (Chuang and Bargmann 2005). However, we found that the tir-1 deletion mutation had no effect on arsenite sensitivity (data not shown). These results suggest that the upstream MAPKKK components that mediate stress-dependent activation of PMK-1 are different from those that mediate neuronal asymmetric development and innate immunity. It is still unknown what components function downstream of PMK-1 in either innate immunity or neuronal asymmetric development. We show that phosphorylation of SKN-1 by PMK-1 induces nuclear translocation of this transcription factor and activation of gcs-1 gene expression in response to oxidative stress. Thus, the present findings suggest that SKN-1 is of central importance for this stress-resistance function of the C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway.

Figure 5.

The p38 MAPK pathways in C. elegans. See text for details.

Materials and methods

C. elegans strains

All strains were maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates at 20°C and fed with bacteria of the OP50 strain, as described by Brenner (1974). The alleles used in this study were N2 Bristol as the wild type, and sek-1(km4), nsy-1(ky400), pmk-1(km25), tir-1(ok1052), unc-43(n498), and skn-1(zu67).

Plasmid constructions

The skn-1::gfp plasmid was described previously (An and Blackwell 2003). The skn-1(S74, 340A)::gfp transgene variant was constructed from the skn-1::gfp transgene by the Quick Change method (Stratagene). To construct fusions of GST to SKN-1, skn-1 cDNA was subcloned into the pGEX3 vector. Mutated GST–SKN-1(S74A), GST–SKN-1(S340A), and GST–SKN-1(S74, 340A) were constructed from pGEX3-skn-1 by PCR. The Psek-1::sek-1::gfp plasmid was described previously (Tanaka-Hino et al. 2002). The ges-1 promoter, a fragment that containing 2.5 kb upstream of the initiation ATG, was constructed from genomic DNA by PCR and subcloned into the GFP vector pPD97.75 by SphI–SalI site (pPD95.75-Pges-1). For constructing Pges-1::sek-1::gfp, an XbaI–KpnI fragment of the sek-1 ORF from Psek-1::sek-1::gfp was subcloned into pPD95.75-Pges-1.

Transgenic analyses

Strains carrying the Psek-1::sek-1::gfp or Pges-1::sek-1::gfp transgene were generated by injecting DNA (50 ng/mL) with the rol-6 marker (pRF4) at 50 ng/mL into the gonads of young adult N2 animals as described (Mello et al. 1991). These extrachromosomal arrays were transferred to sek-1 animals by crossing. The skn-1::gfp-integrated animals and Pgcs-1::gfp extrachromosomal lines were described previously (An and Blackwell 2003). The skn-1::gfp extrachromosomal lines were generated by injecting DNA (2.5 ng/mL) with the rol-6 marker (50 ng/mL) into N2 animals. Some transgenes were transferred to sek-1, pmk-1, and skn-1 mutant animals by crossing.

Arsenite assays

To determine the activation of PMK-1 by arsenite stress, animals grown on normal NGM agar plates were transferred to 1.5-mL test tubes in M9 buffer. Worms were then incubated with M9 buffer or M9 buffer containing 3 or 5 mM sodium arsenite for 30 min at 20°C and subjected to immunoblotting. To assay for arsenite toxicity, well-fed young adults were picked and transferred to normal NGM agar plates or NGM agar plates containing 3 or 5 mM sodium arsenite. Worms were incubated at 20°C, and the number of surviving worms were counted at the indicated times. To investigate the effect of arsenite stress on gcs-1 promoter-driven GFP expression, N2, sek-1 and pmk-1 animals carrying the Pgcs-1::gfp transgene were treated with M9 buffer or M9 buffer containing 5 mM arsenite for 1 h at 20°C. These animals were then transferred to NGM plates and incubated for 3 h at 20°C. To investigate nuclear accumulation of SKN-1::GFP, animals carrying the skn-1::gfp transgene were treated with or without 5 mM arsenite in M9 buffer for 1 h at 20°C. These animals were then placed on 2% agarose plates on slide and immobilized by 0.5% phenoxypropanol, covered with a microscope slip, and observed by fluorescent microscopy (Carl Zeiss).

Immunoblotting

Animals were homogenized in a sample buffer (65 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 3% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 5% b-mercaptoethanol) for immunoblotting. Anti-phospho p38 monoclonal antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. We used a 1:500 dilution of anti-phospho p38 antibody and 1:1000 dilution of anti-PMK-1 antibody.

In vitro kinase assay

Transfection and immunoprecipitation using HEK293 cells were carried out as described previously (Kawasaki et al. 1999; Ninomiya-Tsuji et al. 1999). Bacterially expressed GST–SKN-1 was purified and used as a substrate for HA-PMK-1. For immunoprecipitaion, anti-HA antibody Y-11 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) was used. For immunoblotting, anti-HA antibody Y-11 and anti-Flag antibody M2 (Sigma) were used.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Coulson, A. Fire, Y. Kohara, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for materials. This work was supported by special grants for CREST and Advanced Research on Cancer from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of Japan (K.M. and N.H.) and by NIH grant GM62891 (T.K.B).

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1324805.

References

- An J.H. and Blackwell, T.K. 2003. SKN-1 links C. elegans mesendodermal specification to a conserved oxidative stress response. Genes & Dev. 17: 1882-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman K., McKay, J., Avery, L., and Cobb, M. 2001. Isolation and characterization of pmk-(1–3): Three p38 homologs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell Biol. Res. Commun. 4: 337-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L. and Karin, M. 2001. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature 410: 37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C. and Bargmann, C.A. 2005. Toll-interleukin 1 repeat protein at the synapse specifies asymmetric odorant receptor expression via ASK1 MAPKKK signaling. Genes & Dev. 19: 270-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillault C., Pujol, N., Reboul, J., Sabatier, L., Guichou, J.F., Kohora, Y., and Ewbank, J.J. 2004. TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nature Immun. 5: 488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan C.R., Chung, M.A., Allen, F.L., Heschl, M.F., Van Buskirk, C.L., and McGhee, J.D. 1995. A Gut-to-pharynx/tail switch in embryonic expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans ges-1 gene centers on two GATA sequences. Dev. Biol. 170: 397-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J.D. and McMahon, M. 2001. Molecular basis for the contribution of the antioxidant responsive element to cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Lett. 174: 103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Wakabayashi, N., Katoh, Y., Ishii, T., Igarashi, K., Engel, J.D., and Yamamoto, M. 1999. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes & Dev. 13: 76-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G.L. and Lapadat, R. 2002. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK and p38 protein pathways. Science 298: 1911-1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki M., Hisamoto, N., Iino, Y., Yamamoto, M., Ninomiya-Tsuji, J., and Matsumoto, K. 1999. A Caenorhabditis elegans JNK signal transduction pathway regulates coordinated movement via type-D GABAergic motorneurons. EMBO J. 18: 3604-3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Feinbaum, R., Alloing, G., Emerson, F.E., Garsin, D.A., Inoue, H., Tanaka-Hino, M., Hisamoto, N., Matsumoto, K., Tan, M.W., et al. 2002. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science 297: 623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M. and Avruch, J. 2001. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. 81: 807-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati N.T., Fitzgerald, K.A., Kim, D.H., Feinbaum, R., Golenbock, D.T., and Ausubel, F.M. 2004. Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 101: 6593-6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo M.C., Gay, F., Odom, R., Shi, Y., and Lin, R. 2004. Phosphorylation of the β-catenin/MAPK complex promotes 14–3–3-mediated nuclear export of TCF/POP-1 in signal-responsive cells in C. elegans. Cell 117: 95-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C.C., Kramer, J.M., Stinchcomb, D., and Ambros, V. 1991. Efficient genetransfer in C. elegans: Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10: 3959-3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi H. and Yamamoto, M. 2004. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trend Mol. Med. 10: 549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Kishimoto, K., Hiyama, A., Inoue, J., Cao, Z., and Matsumoto, K. 1999. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-IkB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature 398: 252-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagasti A., Hisamoto, N., Hyodo, J., Tanaka-Hino, M., Matsumoto, K., and Bargmann, C.I. 2001. The CaMKII UNC-43 activates the MAPKKK NSY-1 to execute a lateral signaling decision required for asymmetric olfactory neuron fates. Cell 105: 221-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka-Hino M., Sagasti, A., Hisamoto, N., Kawasaki, M., Nakano, S., Ninomiya-Tsuji, J., Bargmann, C.I., and Matsumoto, K. 2002. SEK-1 MAPKK mediates Ca2+ signaling to determine neuronal asymmetric development in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Rep. 3: 56-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A.K., See, R., Batchelder, C., Kophengnavong, T., Gronniger, J.T., Shi, Y., and Blackwell, T.K. 2000. A conserved transcription motif suggesting functional parallels between Caenorhabditis elegans SKN-1 and Cap'n'Collar-related basic leucine zipper proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 22166-22171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Chen, L., Leung, L., Yen, T.S., Lee, C., and Chan, J.Y. 2005. Liver-specific inactivation of the Nrf1 gene in adult mouse leads to nonal-coholic steatohepatitis and hepatic neoplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102: 4120-4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]