This study aimed to assess how sleep quality affects mental health in adults.

The mean differences (MDs), along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated from the retrieved data using a continuous model with random- or fixed-effects. Approximately 54 papers, comprising a total of 10,196 adults and conducted between 1998 and 2024, were included in this meta-analysis.

Improving sleep significantly reduced depression (MD, -2.92; 95% CI, -3.61 to -2.24, P-value< 0.001) and anxiety (MD, -1.14; 95% CI, -1.32 to -0.97, P-value< 0.001) compared to standard care among adults. However, no significant difference was observed in stress (MD, -1.03; 95% CI, -2.31 to 0.25, P-value= 0.11) between improving sleep and standard care among adults.

Analysis showed that improving overall sleep quality significantly reduced depression and anxiety, though no significant difference was observed in stress compared to standard care among adults. However, considering that the majority of studies had limited sample sizes, the results warrant careful interpretation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-23709-w.

Keywords: Sleep quality, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Improving sleep, Standard care

Key points

1. Recent research indicates that individuals with mental health-related problems are more prone to certain sleep disorders.

2. Numerous clinical trials have assessed the effect of sleep-improving therapeutic approaches, including cognitive behavioral therapeutic interventions for insomnia, on mental health conditions like depressive disorders and anxiety.

3. Attempts have been made to investigate the impacts of these trials on mental health-related outcomes by meta-analyses; however, these studies were unable to draw firm conclusions about the causal link between sleep disorders and mental health-related outcomes.

4. This meta-analysis study revealed that enhancing the overall quality of sleep significantly lowered depression and anxiety.

5. However, the findings showed no significant difference in stress compared to standard care among adults.

6. There is a paucity of studies examining the benefits of sleep improvement on mental health outcomes within existing clinical and community health services. Thus, further clinical service intervention trials are needed to fully understand the efficacy and implementation of these strategies in routine care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-23709-w.

Introduction

Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent globally. Epidemiological studies indicate that nearly one-third of the entire population experiences insomnia symptoms, such as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep. In addition, between 4% and 26% report excessive daytime sleepiness, while 2–4% are diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [1]. A recent study with over 2000 individuals revealed that 32% experienced “general sleep disturbances” [2]. Based on an analysis from the literature, Chattu et al. revealed that public health professionals should enhance their awareness of the unfavorable consequences of sleep deprivation [2]. About 17% of adults experience mental health challenges of varying severity [3]. Nationally representative data analysis suggests that such problems are becoming increasingly common [4]. Therefore, both sleep disturbances and mental health represent major global public health concerns with substantial individual and societal impact [2, 5].

There is a well-established bidirectional link between sleep disruptions and mental health conditions [6]. It was once believed that mental health concerns caused sleep problems [7]; however, it is now recognized that insufficient sleep can also lead to the onset, recurrence [8], and persistence of mental health illnesses [9]. Understanding the magnitude of this correlation—and whether enhancing sleep can improve mental health outcomes—has significant clinical and public health implications. People with insomnia are significantly more likely to experience clinically severe anxiety and depression (10 and 17 times, respectively) [10]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of over twenty longitudinal cohort studies revealed that, compared to people who do not have trouble sleeping, those who suffer from insomnia are twice as likely to develop depression [6].

Studies demonstrate that sleep difficulties correlate with several mental health conditions, particularly highlighting the associations with anxiety, insomnia, and depression. In addition, inadequate sleep has been linked to eating disorders [11], posttraumatic stress disorder [12], and symptoms within the psychosis spectrum, such as hallucinations and delusions [13]. Moreover, research demonstrates that patients with mental health disorders are more likely to experience certain sleep abnormalities, including sleep apnea [14], circadian rhythm disruptions [15], restless leg syndrome [16], excessive daytime drowsiness [17], narcolepsy [18], sleepwalking, and nightmares [19].

Despite significant observational evidence, establishing causality in the sleep-mental health link remains difficult. Most present research used cross-sectional or longitudinal designs, which can identify connections but are unable to identify causal direction [20]. Cross-sectional research is unable to establish temporal sequence, but longitudinal studies, albeit being more robust, remain vulnerable to residual confounding and various biases [21]. Experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [7], improve causal inference by limiting the effects of confounding variables [8]. To determine if sleep problems have a causal effect on mental health, researchers must manipulate sleep and record subsequent mental health changes—a method consistent with interventionist theories of causality [22]. Numerous RCTs have assessed the impact of sleep-enhancement therapies, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), on mental wellness outcomes such as depression and anxiety. Meta-analyses have attempted to consolidate these findings [23].

Nevertheless, existing meta-analyses have numerous limitations. Initially, certain studies incorporate interventions that failed to enhance sleep, thereby precluding the evaluation of the association between sleep and mental wellness [24]. Secondly, many research studies focus mainly on short-term results measured right after the intervention, which limits understanding of long-term benefits and creates uncertainty about sustained effects. Third, the majority of reviews concentrate on CBT-I, primarily addressing depression, while neglecting other mental health outcomes and alternative therapies. Ultimately, there is a lack of comprehensive research on the factors that may influence the efficacy of sleep therapy for mental health across diverse populations, settings, and study designs.

Objectives

This evaluation sought to provide a reliable and precise assessment of how interventions that improve sleep quality affect mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress. We selected RCTs that reported improved sleep quality in the interventional group compared to controls, and then assessed mental health-related issues to objectively quantify this benefit. We did not limit cognitive behavioral therapy or mental wellness measures to depression or anxiety. Rather, we analyzed any sleep-related approach that led to a significant change in sleep quality compared to control subjects, and investigated how that difference influenced subsequent mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and stress.

To more effectively isolate the impact of sleep enhancement interventions, we excluded therapies that specifically targeted mental health issues, such as CBT designed to address depressive disorders. Acknowledging the potential for significant variability among studies, we employed moderation analyses to examine the impact of study characteristics and demographic factors on the outcomes. Our fundamental assertion was that therapies that significantly enhance sleep would ultimately lead to corresponding improvements in mental health.

Method

Design

The meta-analyses were conducted using a predefined epidemiological procedure [9]. Data was collected and analyzed using several databases, including PubMed, the Cochrane Library, OVID, Google Scholar, and Embase [11, 12, 25, 26].

All retrieved studies were combined into a single EndNote file. The initial screening procedure removed duplicate entries. Firstly, we reviewed the titles and abstracts and excluded ineligible records. Secondly, we continued screening and evaluated the full-text articles based on the inclusion criteria, incorporating eligible records into the review and dismissing ineligible ones, along with the rationale for their deletion. Two authors performed an independent review of the documents. These datasets were used to analyze the effects of sleep quality on adult mental health [27]. To assess the effect size of sleep quality, we used the following metrics: self-reported assessments of overall sleep quality, such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and measures of sleep duration and its impact on daily functioning, such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [27].

To measure the effect size of mental health outcomes, we examined the impact of improved sleep on specific issues, namely depression, anxiety, and stress, separately from other mental health outcomes. We measured how sleep affected each mental health issue reported at the latest follow-up time of the study. This technique provides a thorough assessment of the influence of improved sleep quality on mental status-related outcomes, necessitating the maintenance of any changes over an extended period [22, 23]. We pooled the effect sizes to derive a composite metric for mental health. In line with the assessment of sleep quality, we emphasized self-reported measures of mental health above measures rated by observers, as the personal perception of mental health issues is undoubtedly the most significant.

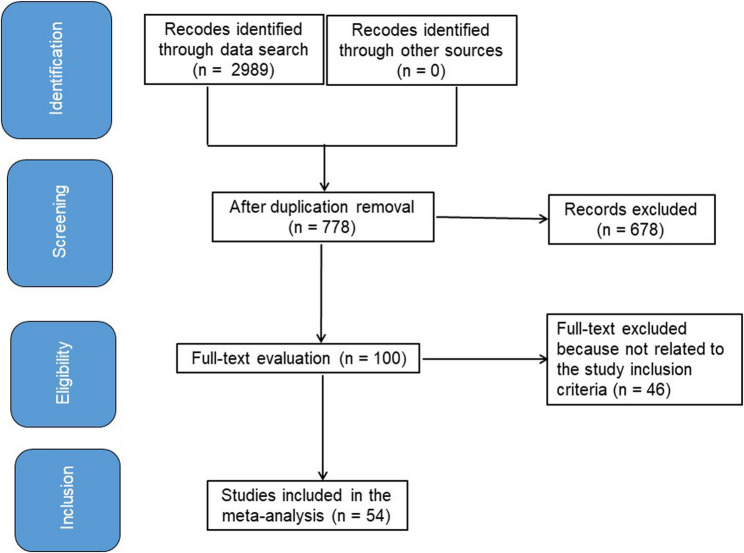

Data pooling

Recent research has shown that improving sleep produces several therapeutic benefits. This study investigated the primary outcomes based on the inclusion criteria. Language barriers were not considered during study selection and participant screening. There were no limitations regarding the number of participants eligible for inclusion. A total of 35 letters, reviews, and editorials were excluded from the analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the full study selection process.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the examination procedure

Eligibility of studies

The effects of the quality of sleep on adult mental wellness were being investigated. Only studies that discussed how the applied interventions affected the occurrence of various clinical outcomes were included in the conducted sensitivity analyses. Subgroup assessments were also carried out.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Figure 1 serves as an in-depth summary of the investigation. Upon fulfillment of the inclusion criteria, the literature was included in the study [9, 13, 14]:

The study was an RCT and controlled prospective.

Adults were the subjects under investigation.

Validly assess the independent contribution of changes in sleep on mental health outcomes among adult populations.

The study examined the impact of sleep quality on adult mental health [25].

We excluded non-comparative studies, studies with incomplete data reporting, and studies reporting different outcomes.

Study identification

The PICOS framework was used to guide the development of the search strategy [28], as follows: P (population) Adult; Improving sleep was I (intervention). C (comparison): included comparing sleep quality improvement to standard treatment [29]. O (outcome): mental health illnesses, such as depression, anxiety, and psychological stress; S (study design): the study design was not restricted. Using the keywords in Table 1, we conducted a thorough search of the relevant databases through April 2025. Appraisals were conducted on all publications contained in a software for reference management, including authors, titles, and abstracts. Furthermore, two authors review articles to identify relevant tests [11, 12, 15].

Table 1.

Database search strategy for inclusion of examinations

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| Google Scholar |

#1 “adult” OR “depression” #2 “stress” OR “improving sleep” OR"“anxiety” OR “standard care” #3 #1 AND #2 |

| Embase |

#1 ‘adult’/exp OR ‘depression’/exp OR ‘anxiety’ #2 ‘stress’/exp OR ‘improving sleep’/exp OR ‘standard care’ #3 #1 AND #2 |

| Cochrane library |

#1 (adult): ti, ab, kw (depression): ti, ab, kw (anxiety): ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) #2 (stress): ti, ab, kw OR (improving sleep): ti, ab, kw OR(standard care): ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) #3 #1 AND #2 |

| Pubmed |

#1 “adult“[MeSH] OR “depression“[MeSH] OR “anxiety” [All Fields] #2 “stress“[MeSH Terms] OR “improving sleep“[MeSH] OR “standard care “[All Fields] #3 #1 AND #2 |

| OVID |

#1 “adult“[All Fields] OR “depression” [All Fields] OR “anxiety” [All Fields] #2 “stress“[All fields] OR “improving sleep“[All Fields] or “standard care“[All Fields] #3 #1 AND #2 |

Screening of studies and data collection

Each study was documented in a standardized format, including key elements. Criteria employed to reduce the data included the authors’ surname, the date of the study, country of execution, the target population, the overall number of subjects, clinical and therapeutic features, demographic details, and qualitative and quantitative assessment methods [30]. Two authors examined the potential for bias in the research and the standards of methodologies employed in the papers selected for supplemental analysis. The two authors performed impartial evaluations of the methodologies employed for each examination [31].

In addition, we also extracted statistical data for effect size calculation, information concerning the characteristics of the analyzed studies such as the publication status, and study attributes (e.g., the target and control groups, duration of follow-up), and the approach investigated (e.g., type of intervention, mode of application) was also recorded.

Statistical analysis

The mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined using a continuous model with random- or fixed-effects [16]. The calculated I2 index ranges from 0 to 100 and is represented as a percentage. Elevated I2 levels indicate greater heterogeneity, whereas diminished I2 values reflect reduced heterogeneity [17]. If I2 was 50% or more, we applied the random effect; if not, the fixed effect was chosen [18, 31]. Bias was determined using Egger’s statistical tests for quantitative analysis, deemed present if P-value > 0.05 using a two-tailed method [32, 33]. Graphs and statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4. 31.

Results

Upon reviewing 2989 relevant papers, 54 studies published between 1998 and 2024 were deemed eligible and included in this analysis [19–24, 27–73].

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics of these studies, which involved approximately 10,196 participants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies

| Study | Country | Total | Improving sleep | Standard care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCurry, 1998 [19] | USA | 21 | 7 | 14 |

| Savard, 2005 [20] | Canada | 57 | 27 | 30 |

| Chen, 2009 [21] | China | 128 | 62 | 66 |

| Wagley, 2009 [34] | USA | 34 | 24 | 10 |

| Yeung, 2011 [35] | China | 52 | 26 | 26 |

| Germain, 2012 [22] | USA | 35 | 17 | 18 |

| Jansson-Fröjmark, 2012 [23] | Danermark | 32 | 17 | 15 |

| Jernelöv, 2012 [24] | Sweden | 87 | 44 | 43 |

| Jungquist, 2012 [36] | USA | 20 | 15 | 5 |

| Katofsky, 2012 [37] | Germany | 80 | 41 | 39 |

| Lancee, 2013 [38] | Netherlands | 262 | 129 | 133 |

| Lichstein, 2013 [39] | USA | 47 | 24 | 23 |

| Raskind, 2013 [40] | USA | 67 | 32 | 35 |

| Espie, 2014 [27] | UK | 109 | 55 | 54 |

| Garland, 2014 [41] | Canada | 111 | 47 | 64 |

| Irwin, 2014 [42] | USA | 75 | 50 | 25 |

| Martínez, 2014 [28] | Spain | 59 | 30 | 29 |

| Ashworth, 2015 [29] | Australia | 36 | 18 | 18 |

| Casault, 2015 [43] | Canada | 38 | 20 | 18 |

| Falloon, 2015 [30] | New Zealand | 93 | 43 | 50 |

| Kaldo, 2015 [31] | Sweden | 148 | 73 | 75 |

| Norell-Clarke, 2015 [44] | Sweden | 64 | 32 | 32 |

| Park, 2015 [32] | Korea | 24 | 12 | 12 |

| Bergdahl, 2016 [33] | Sweden | 45 | 22 | 23 |

| Cape, 2016 [45] | UK | 192 | 92 | 100 |

| Chang a, 2016 [46] | China | 72 | 35 | 37 |

| Chang b, 2016 [47] | China | 84 | 43 | 41 |

| Christensen, 2016 [48] | Australia | 504 | 280 | 224 |

| Blom, 2017 [49] | Sweden | 37 | 20 | 17 |

| Freeman, 2017 [50] | UK | 3755 | 1891 | 1864 |

| Nguyen, 2017 [51] | Australia | 15 | 9 | 6 |

| Chung, 2018 [52] | China | 128 | 96 | 32 |

| Sadler, 2018 [53] | Australia | 47 | 24 | 23 |

| Schiller, 2018 [54] | Sweden | 51 | 25 | 26 |

| Wen, 2018 [55] | China | 89 | 43 | 46 |

| Zhu, 2018 [56] | China | 49 | 37 | 12 |

| Espie, 2019 [57] | UK | 1711 | 853 | 858 |

| Kalmbach, 2019 [58] | USA | 83 | 42 | 41 |

| McCrae, 2019 [59] | USA | 50 | 27 | 23 |

| Nguyen, 2019 [60] | Australia | 24 | 13 | 11 |

| Peoples, 2019 [61] | USA | 67 | 32 | 35 |

| Sato, 2019 [62] | Japan | 23 | 11 | 12 |

| Ham, 2020 [63] | Korea | 44 | 24 | 20 |

| Kyle, 2020 [64] | UK | 410 | 205 | 205 |

| Lee, 2020 [65] | Korea | 98 | 49 | 49 |

| Song, 2020 [66] | Korea | 25 | 12 | 13 |

| Zhang, 2020 [67] | China | 96 | 48 | 48 |

| Chao, 2021 [68] | USA | 85 | 39 | 46 |

| Hwang, 2022 [69] | Korea | 126 | 63 | 63 |

| Vollert, 2023 [70] | USA | 214 | 82 | 132 |

| Asplund, 2023 [71] | Sweden | 69 | 35 | 34 |

| Xiang, 2024 [72] | USA | 68 | 35 | 33 |

| Elder a, 2024 [73] | UK | 56 | 27 | 29 |

| Elder b, 2024 [73] | China | 200 | 100 | 100 |

| Total | 10,196 | 5159 | 5037 |

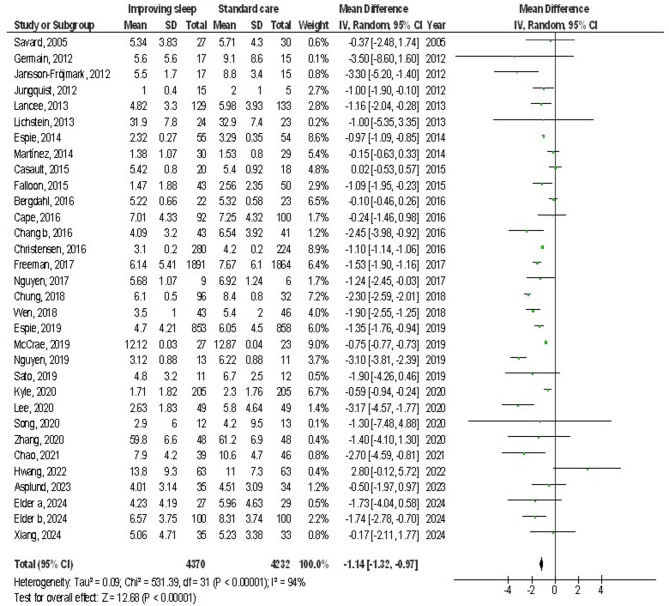

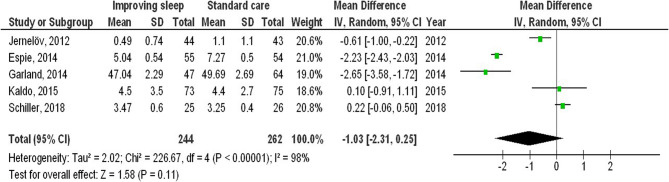

Improving sleep, as indicated by the validated questionnaire scores, was associated with significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms (MD, −2.92; 95% CI: −3.61 to −2.24, P-value < 0.001) with high levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 99%), and anxiety symptoms (MD, −1.14; 95% CI: −1.32 to −0.97, P-value < 0.001) with moderate levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 50%) compared to standard care among adults, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. However, no significant difference was detected in stress (MD, −1.03; 95% CI: −2.31-0.25, P-value = 0.11) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 98%) between improved sleep quality and standard care among adults, as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

The effect’s forest plot of the improvement in sleep on depression compared to standard care among adults

Fig. 3.

The effect’s forest plot of the improvement in sleep on anxiety compared to standard care among adults

Fig. 4.

The effect’s forest plot of the improvement in sleep on stress compared to standard care among adults

The quantitative results of the Egger regression test and the graphical examination of the effect’s funnel plot indicated no evidence of bias (p = 0.86), as illustrated in Figs. 5, 6 and 7. The majority of relevant examinations were revealed to have inadequate practical quality and exhibited bias in their selective reporting.

Fig. 5.

The effect’s funnel plot of the improvement in sleep on depression compared to standard care among adults

Fig. 6.

The effect’s funnel plot of the improvement in sleep on anxiety compared to standard care among adults

Fig. 7.

The effect’s funnel plot of the improvement in sleep on stress compared to standard care among adults

Discussion

For the current meta-analysis, 54 studies published between 1998 and 2024 were included; these studies involved 10,196 participants [19–24, 27–73].

The data analyzed revealed that improved sleep quality scores in validated questionnaires resulted in significantly lower levels of depression and anxiety symptoms in adults compared to standard care. There was no significant change in stress levels between improved sleep scores and conventional adult care. However, considering that the majority of the research used a small sample size (40 studies used sample sizes of less than 100 people), the results should be interpreted with caution.

Due to a lack of primary research, it is premature to draw definitive conclusions regarding other mental health disorders (for example, suicidal ideation within the psychotic spectrum, post-traumatic stress disorder, and burnout). A significant dose-response relationship was seen between alterations in sleep quality and subsequent enhancements in mental health, indicating that greater improvements in sleep correlate with more substantial benefits in mental health [74]. The effects persisted even after adjustments, despite some indication of publication bias [75]. When considered as a whole, the results highlight the connection between improved sleep and better mental health, indicating a strong relationship between sleep deprivation and mental health issues. The current research provides credence to the notion that sleep hygiene benefits people of all backgrounds and demographics [76]. Regardless of concurrent mental and/or physical health issues, higher sleep quality had a medium-sized and statistically significant beneficial effect on composite mental health. Given the difficulties in providing healthcare linked to multi-morbidity [77], as well as the tendency for mental and physical health issues to co-occur [78], which seems to be on the rise [79]. According to the results of this study, it is crucial that the benefits of getting more sleep for mental health also apply to people with co-occurring medical conditions. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that getting more sleep can improve physical health outcomes like exhaustion [80], chronic pain [81], and general health-related quality of life [82]. It may also lower medical expenses. Offering a digital cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to primary care patients, for instance, was linked to significant cost savings [83]. Cost savings resulting from sleep-related interventions have also been documented in individuals with co-occurring mental health conditions, such as depression [84]. This implies that enhancing sleep may be beneficial for many mental health conditions, expanding the potential effects of sleep treatments in healthcare settings. Lastly, there is mounting evidence that sleep disruptions are a predictor of future mental health issues. In patients at elevated risk of psychosis, inadequately short duration and more erratic sleep have been associated with increased severity of delusions and hallucinations. Implementing early therapies that enhance sleep may mitigate the chance of developing significant mental health issues. The recent study discovered that enhancing sleep markedly benefits future mental wellness among individuals with non-clinical experiences. Mild-to-moderate mental health concerns may eventually lead to more serious diagnoses [85]. Enhancing sleep may be one strategy that can be used in conjunction with other strategies to reduce the risk of transition. There are various advantages to the current review. Firstly, it offers a thorough and current search and investigation of RCTs investigating the impact of better sleep on a range of future mental health-related outcomes. In fact, this meta-analysis represents one of the biggest studies to date that assesses the impact of better sleep on mental health. Second, the purpose of the meta-analysis was to examine the causal relationship between sleep and mental health (i.e., only RCTs were included, successful sleep quality improvement was necessary, there was a temporal lag between measures, etc.). Although the general method has been utilized in other domains, to our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to employ it in the subject of sleep and mental health [86]. Initially, only a small number of studies investigated the long-term benefits of enhanced sleep. Extended follow-up studies usually revealed reduced effects (though statistically significant); this is most likely owing to the drugs’ fading impact on sleep quality over time [87].

As a result, it’s critical that sleep-quality programs that aim to enhance mental health continue to have positive impacts. Secondly, this evaluation included several outcomes for which few primary studies were available. Therefore, the conclusions we can draw for mental health outcomes other than depression and anxiety are more constrained in the absence of further studies reporting these outcomes. Third, although the objective of this study was to encompass a broad spectrum of sleep disorders, much of the research is based on cognitive behavioral therapy interventions for insomnia. This may be due to the predominant focus of earlier studies on the correlation between insomnia and mental health [88]. This may be due to t. However, it is conceivable that certain studies not explicitly focused on insomnia were omitted due to our prioritization of sleep quality. The concept of improvement differs among sleep disorders and may not consider sleep quality. For instance, daytime drowsiness is a crucial finding in sleep apnea studies, and sleep timing plays a significant role in circadian rhythm disorders. Future studies should examine how treating particular sleep disorders affects mental health by defining improvements in terms of outcomes unique to those sleep disorders. The current evaluation identified a number of topics requiring further investigation in the future, both theoretically and in terms of the application of research findings. First, future research should examine the longer-term effects of improving sleep on mental health, since the primary studies measured mental health on average about 20.5 weeks post-intervention, and the effect of improved sleep on mental health significantly decreased over time. Second, most of the RCTs in the current study were at high risk or had uncertain risk of bias, which is not unusual. Consequently, we need more research with a lower risk of methodological bias, in addition to examining the long-term effects of better sleep on a variety of mental health issues beyond anxiety and depression. Lastly, while the current research indicates a causal relationship between sleep and mental health, the precise mechanisms by which sleep influences mental health remain unclear. Whether and how people control their emotions (e.g., in response to unfavorable outcomes) is one possible mechanism. In fact, research indicates that insufficient sleep can worsen the effects of unfavorable life events [89], lessen the positive effects of favorable events [90], and be linked to a higher frequency of emotion control techniques that may be harmful to mental health [91]. Thus, while experimental findings showed that induced sleep deprivation is negatively linked to worse emotional regulation [92], changes in sleep patterns showed a prospective association with changes in aspects of emotional regulation [92], even though we are not aware of RCTs examining the impact of improved sleep quality on emotional regulation. Contemporary theories of emotion regulation, like the action control viewpoint, propose that managing emotions involves three stages. The first step involves recognizing the need for regulation, choosing the approach and scope of regulation, and putting a regulatory plan into action [93]. These theories are based on studies on how people control their behavior. We suggest that any or all the activities implicated in efficiently regulating emotions could be negatively impacted by poor sleep quality, which could help to explain the connection between inadequate sleep and mental wellness. In order to clarify the pathways by which increases in sleep improve mental health, future studies using assessments of emotional regulation features (e.g., the Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale [88]) with longitudinal and experimental designs are recommended. Evidence regarding the impact of sleep on mental health also supports recommendations for regular screening of sleep disorders and their treatment in terms of practice and implementation. The Mental Health Foundation and the Royal Society for Public Health both advise that basic health care education include knowledge of and proficiency in diagnosing sleep disorders [94]. Not much progress has been made thus far despite this and the increasing amount of data [95]. This might be due to the lack of adequate understanding of the significance of sleeping habits [75], inadequate training and expertise in identifying and treating sleep issues [96], and a lack of time and resources [75]. Therefore, investigating the obstacles and enablers to conducting sleep assessments and providing efficient therapies in particular care settings—from the viewpoints of patients and clinicians—might be a lucrative next step. The current study also brought to light the paucity of studies examining the impact of sleep enhancement on mental health outcomes in “real-world” contexts, such as within already available clinical and community health services. While some researchers are making significant progress in this area [76], further clinical service intervention trials are obviously needed to fully understand the efficacy and use of these strategies in normal care.

The meta-analysis had several limitations: Assortment bias may have occurred due to the exclusion of certain papers intended for inclusion. However, all excluded studies failed to meet the requisite criteria for the analysis. Nonetheless, data on factors such as ethnicity, age, and gender were essential to ascertain their influence on outcomes. In addition, a high level of heterogeneity was observed between outcomes. The potential sources of heterogeneity might include the differences in the studies’ populations, differences in the types and durations of sleep interventions, and the use of various tools to assess sleep quality, depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. We note that methodological differences may have influenced impact sizes and contributed to the diversity observed in our research. The objective of the study was to elucidate the effect of sleep quality on adult mental health. The use of imprecise or insufficient data from prior research likely exacerbated bias. The individual’s age, gender, ethnicity, and nutritional status were the primary variables that likely contributed to discrimination. Unreported studies and inadequate data may have unintentionally altered values. Contemporary theories of emotion regulation, like the action control viewpoint, propose that managing emotions involves three stages. The first step involves recognizing the need for regulation, choosing the approach and scope of regulation, and putting a regulatory plan into action.

Conclusions

The data showed that improving sleep led to significantly lower depression and anxiety symptoms compared to standard care among adults. Nevertheless, no significant difference in stress levels was observed between the sleep improvement and standard care groups. Though given that most of the studies comprised a minor sample size (40 studies utilizing sample sizes lower than 100 subjects), their values warrant careful consideration.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

X.M., Z.L., and T.Z.: Concept and methodology, X.M., Z.L. and T.Z.: software, T.Z.: data curation, Z.L.,and T.Z.: validation and visualization, Z.L. and T.Z.: writing initial draft, Z.L., and T.Z.: review of writing, T.Z.: supervision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. We confirm that the work is original; the work has not been, and will not be published, in whole, or in part, in any other journal; and all the authors have agreed to the contents of the manuscript in its submitted form.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

On request, the corresponding author is required to provide access to the meta-analysis database.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1. Ohayon MM. Epidemiological overview of sleep disorders in the general population. Sleep Med Res. 2011;2(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chattu VK, Manzar MD, Kumary S, et al. The global problem of insufficient sleep and its serious public health implications. Healthcare. 2019;7(1):1. 10.3390/healthcare7010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bebbington PE, McManus S. Revisiting the one in four: the prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the population of England 2000–2014. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;216(1):55–7. 10.1192/bjp.2019.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale L, Troxel W, Buysse DJ. Sleep health: an opportunity for public health to address health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:81–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1):10–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohrer JM. Thinking clearly about correlations and causation: graphical causal models for observational data. Adv Methods Practices Psychol Sci. 2018;1(1):27–42. 10.1177/2515245917745629. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright N. Hunting causes and using them: approaches in philosophy and economics. Cambridge University Press; 2007.

- 9.Emad M, Osama H, Rabea H, et al. Dual compared with triple antithrombotics treatment effect on ischemia and bleeding in atrial fibrillation following percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;1(2):77–87. 10.61466/ijcmr1020010.

- 10.Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia, depression, and anxiety. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1457–64. 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amin MA. A meta-analysis of the eosinophil counts in the small intestine and colon of children without Obvious Gastrointestinal disease. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;1(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaaban MEA, Mohamed AIM. Determining the efficacy of N-acetyl cysteine in treatment of pneumonia in COVID-19 hospitalized patients: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;1(2):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osama H, Saeed H, Nicola M, et al. Neuraxial anesthesia compared to general anesthesia in subjects with hip fracture surgery: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;1(2):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Y. Effect of resident participation in ophthalmic surgery on wound dehiscence: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Med Res. 2024;2(2).

- 15.Zangeneh MM, Zangeneh A. Prevalence of wound infection following right anterolateral thoracotomy and median sternotomy for resection of benign atrial masses that induce heart failure, arrhythmia, or thromboembolic events: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;2(1):27–33. 10.61466/ijcmr2010004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. 10.1136/bmj. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A, Das A, Majumder K, et al. Obesity is independently associated with increased risk of hepatocellular Cancer–related mortality. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(9):874–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikhbahaei S, Trahan TJ, Xiao J, et al. FDG-PET/CT and MRI for evaluation of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Oncologist. 2016;21(8):931–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, et al. Successful behavioral treatment for reported sleep problems in elderly caregivers of dementia patients: a controlled study. Journals Gerontol Ser B: Psychol Sci Social Sci. 1998;53(2):P122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H, et al. Randomized study on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia secondary to breast cancer, part I: sleep and psychological effects. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6083–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen K-M, Chen M-H, Chao H-C, et al. Sleep quality, depression state, and health status of older adults after silver yoga exercises: cluster randomized trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(2):154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Germain A, Richardson R, Moul DE, et al. Placebo-controlled comparison of Prazosin and cognitive-behavioral treatments for sleep disturbances in US military veterans. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(2):89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansson-Fröjmark M, Linton SJ, Flink IK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia co-morbid with hearing impairment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19:224–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jernelöv S, Lekander M, Blom K, et al. Efficacy of a behavioral self-help treatment with or without therapist guidance for co-morbid and primary insomnia-a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundaresan A. Wound complications frequency in minor technique gastrectomy compared to open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;1(3):100–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh RK. A meta-analysis of the impact on gastrectomy versus endoscopic submucosal dissection for early stomach cancer. Int J Clin Med Res. 2023;1(3):88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espie CA, Kyle SD, Miller CB, et al. Attribution, cognition and psychopathology in persistent insomnia disorder: outcome and mediation analysis from a randomized placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioural therapy. Sleep Med. 2014;15(8):913–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martínez MP, Miró E, Sánchez AI, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and sleep hygiene in fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2014;37:683–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashworth DK, Sletten TL, Junge M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: an effective treatment for comorbid insomnia and depression. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):11–123. 10.1037/cou0000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falloon K, Elley CR, Fernando A, et al. Simplified sleep restriction for insomnia in general practice: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(637):e508–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaldo V, Jernelöv S, Blom K, et al. Guided internet cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia compared to a control treatment–a randomized trial. Behav Res Ther. 2015;71:90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SD, Yu SH. The effects of nordic and general walking on depression disorder patients’ depression, sleep, and body composition. J Phys Therapy Sci. 2015;27(8):2481–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergdahl L, Broman J-E, Berman AH et al. Auricular acupuncture and cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a randomised controlled study. Sleep Disorders. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Wagley JN. Efficacy of a brief intervention for insomnia among psychiatric outpatients, in College of humanities and sciences. Virginia Commonwealth University; 2009. p. 49.

- 35.Yeung W-F, Chung K-F, Tso K-C, et al. Electroacupuncture for residual insomnia associated with major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2011;34(6):807–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jungquist CR, Tra Y, Smith MT, Pigeon WR, Matteson-Rusby S, Xia Y, Perlis ML. The durability of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Disord. 2012;2012:679648. 10.1155/2012/679648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Katofsky I, Backhaus J, Junghanns K, et al. Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral self-help program for patients with primary insomnia in general practice–a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2012;13(5):463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lancee J, van den Bout J, Sorbi MJ, et al. Motivational support provided via email improves the effectiveness of internet-delivered self-help treatment for insomnia: a randomized trial. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(12):797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lichstein KL, Nau SD, Wilson NM, et al. Psychological treatment of hypnotic-dependent insomnia in a primarily older adult sample. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(12):787–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of Prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garland SN, Carlson LE, Stephens AJ, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia comorbid with cancer: a randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):449–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. Tai Chi for late life insomnia and inflammatory risk: a randomized controlled comparative efficacy trial. Sleep. 2014;37(9):1543–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casault L, Savard J, Ivers H, et al. A randomized-controlled trial of an early minimal cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia comorbid with cancer. Behav Res Ther. 2015;67:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norell-Clarke A, Jansson-Fröjmark M, Tillfors M, et al. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: effects on sleep and depressive symptomatology in a sample with comorbidity. Behav Res Ther. 2015;74:80–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cape J, Leibowitz J, Whittington C, et al. Group cognitive behavioural treatment for insomnia in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2016;46(5):1015–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang SM, Chen CH. Effects of an intervention with drinking chamomile tea on sleep quality and depression in sleep disturbed postnatal women: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(2):306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang Y-L, Chiou A-F, Cheng S-M, et al. Tailored educational supportive care programme on sleep quality and psychological distress in patients with heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;61:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Gosling JA, et al. Effectiveness of an online insomnia program (SHUTi) for prevention of depressive episodes (the goodnight Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(4):333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blom K, Jernelöv S, Rück C, et al. Three-year follow-up comparing cognitive behavioral therapy for depression to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, for patients with both diagnoses. Sleep. 2017;40(8):zsx108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman D, Sheaves B, Goodwin GM, et al. The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): a randomised controlled trial with mediation analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(10):749–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen S, McKay A, Wong D, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy to treat sleep disturbance and fatigue after traumatic brain injury: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(8):1508–17. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung K-F, Yeung W-F, Yu BY-M, et al. Acupuncture with or without combined auricular acupuncture for insomnia: a randomised, waitlist-controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2018;36(1):2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadler P, McLaren S, Klein B, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for older adults with insomnia and depression: a randomized controlled trial in community mental health services. Sleep. 2018;41(8):zsy104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiller H, Söderström M, Lekander M, et al. A randomized controlled intervention of workplace-based group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91:413–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wen X, Wu Q, Liu J, et al. Randomized single-blind multicenter trial comparing the effects of standard and augmented acupuncture protocols on sleep quality and depressive symptoms in patients with depression. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23(4):375–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu D, Dai G, Xu D, et al. Long-term effects of Tai Chi intervention on sleep and mental health of female individuals with dependence on amphetamine-type stimulants. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Espie CA, Emsley R, Kyle SD, et al. Effect of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalmbach DA, Cheng P, Arnedt JT, et al. Treating insomnia improves depression, maladaptive thinking, and hyperarousal in postmenopausal women: comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI), sleep restriction therapy, and sleep hygiene education. Sleep Med. 2019;55:124–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCrae CS, Williams J, Roditi D, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatments for insomnia and pain in adults with comorbid chronic insomnia and fibromyalgia: clinical outcomes from the SPIN randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2019;42(3):zsy234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nguyen S, Wong D, McKay A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for post-stroke fatigue and sleep disturbance: a pilot randomised controlled trial with blind assessment. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2019;29(5):723–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peoples AR, Garland SN, Pigeon WR, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia reduces depression in cancer survivors. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(1):129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sato D, Yoshinaga N, Nagai E, et al. Effectiveness of internet-delivered computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with insomnia who remain symptomatic following pharmacotherapy: randomized controlled exploratory trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4):e12686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ham OK, Lee BG, Choi E, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral treatment for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. West J Nurs Res. 2020;42(12):1104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kyle SD, Hurry ME, Emsley R, et al. The effects of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on cognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2020;43(9):zsaa034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee B, Kim B-K, Kim H-J, et al. Efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture for insomnia disorder: a multicenter, randomized, assessor-blinded, controlled trial. Nat Sci Sleep. 2020;12:1145–59. 10.2147/NSS.S281231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Song ML, Park KM, Motamedi GK, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in restless legs syndrome patients. Sleep Med. 2020;74:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang L, Tang Y, Hui R, et al. The effects of active acupuncture and placebo acupuncture on insomnia patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(10):1201–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chao LL, Kanady JC, Crocker N, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in veterans with Gulf war illness: results from a randomized controlled trial. Life Sci. 2021;279:119147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hwang H, Kim SM, Netterstrøm B, et al. The efficacy of a smartphone-based app on stress reduction: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e28703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vollert B, Müller L, Jacobi C, et al. Effectiveness of an App-Based short intervention to improve sleep: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health. 2023;10(1):e39052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Asplund RP, Carvallo F, Christensson H, et al. Learning how to recover from stress: results from an internet-based randomized controlled pilot trial. Internet Interventions. 2023;34:100681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiang X, Kayser J, Turner S, et al. Layperson-Supported, Web-Delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in older adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e53001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Elder GJ, Santhi N, Robson AR, et al. An online behavioral self-help intervention rapidly improves acute insomnia severity and subjective mood during the Coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a stratified randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2024;47(6):zsae059. 10.1093/sleep/zsae059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Scott AJ, Webb TL, Martyn-St M, James, et al. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meaklim H, Jackson ML, Bartlett D, et al. Sleep education for healthcare providers: addressing deficient sleep in Australia and new Zealand. Sleep Health. 2020;6(5):636–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stott R, Pimm J, Emsley R, et al. Does adjunctive digital CBT for insomnia improve clinical outcomes in an improving access to psychological therapies service? Behav Res Ther. 2021;144:p103922. 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen H, Manolova G, Daskalopoulou C, et al. Prevalence of Multimorbidity in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Comorbidity. 2019;9:2235042X19870934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Gabalawy R, Mackenzie CS, Shooshtari S, et al. Comorbid physical health conditions and anxiety disorders: a population-based exploration of prevalence and health outcomes among older adults. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(6):556–64. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sartorious N. Comorbidity of mental and physical diseases: a main challenge for medicine of the 21st century. Shanghai Archives Psychiatry. 2013;25(2):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Espie CA, Fleming L, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized controlled clinical effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy compared with treatment as usual for persistent insomnia in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(28):4651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Selvanathan J, Pham C, Nagappa M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain– A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101460. 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kyle SD, Morgan K, Espie CA. Insomnia and health-related quality of life. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(1):69–82. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sampson C, Bell E, Cole A, et al. Digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia and primary care costs in England: an interrupted time series analysis. BJGP Open. 2022;6(2):BJGPO.2021.0146. 10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Watanabe N, Furukawa TA, Shimodera S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with depression: analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(6):335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness–persistence–impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(2):249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van der Zweerde T, Bisdounis L, Kyle SD, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A meta-analysis of long-term effects in controlled studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;48:101208. 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Leary K, Bylsma LM, Rottenberg J. Why might poor sleep quality lead to depression? A role for emotion regulation. Cogn Emot. 2017;31(8):1698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zohar D, Tzischinsky O, Epstein R, et al. The effects of sleep loss on medical residents’ emotional reactions to work events: a Cognitive-Energy model. Sleep. 2005;28(1):47–54. 10.1093/sleep/28.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang J, Lau EYY, Hsiao JH-w. Using emotion regulation strategies after sleep deprivation: ERP and behavioral findings. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2019;19:283–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vandekerckhove M, Wang Y-l. Emotion, emotion regulation and sleep: an intimate relationship. AIMS Neurosci. 2018;5(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Webb TL, Schweiger Gallo I, Miles E, et al. Effective regulation of affect: an action control perspective on emotion regulation. Eur Rev Social Psychol. 2012;23(1):143–86. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alamir YA, Zullig KJ, Kristjansson AL, et al. A theoretical model of college students’ sleep quality and health-related quality of life. J Behav Med. 2022;45:925–34. 10.1007/s10865-022-00348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Freeman D, Sheaves B, Waite F, et al. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):628–37. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.O’Sullivan M, Rahim M, Hall C. The prevalence and management of poor sleep quality in a secondary care mental health population. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(02):111–6. 10.5664/jcsm.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

On request, the corresponding author is required to provide access to the meta-analysis database.