Abstract

There is now accumulating evidence that the striatal complex in its two major components, the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens, contributes to spatial memory. However, the possibility that different striatal subregions might modulate specific aspects of spatial navigation has not been completely elucidated. Therefore, in this study, two different learning procedures were used to determine whether the two striatal components could be distinguished on the basis of their involvement in spatial learning using different frames of reference: allocentric and egocentric. The task used involved the detection of a spatial change in the configuration of four objects placed in an arena, after the mice had had the opportunity to experience the objects in a constant position for three previous sessions. In the first part of the study we investigated whether changes in the place where the animals were introduced into the arena during habituation and testing could induce a preferential use of an egocentric or an allocentric frame of reference. In the second part of the study we performed focal injections of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors' antagonist, AP-5, within the two subregions immediately after training. The results indicate that using the two behavioral procedures, the animals rely on an egocentric and an allocentric spatial frame of reference. Furthermore, they demonstrate that AP-5 (37.5, 75, and 150 ng/side) injections into the dorsal striatum selectively impaired consolidation of spatial information in the egocentric but not in the allocentric procedure. Intra-accumbens AP-5 administration, instead, impaired animals trained using both procedures.

The striatal complex is a structure located at the base of the fore-brain. From a functional point of view, it has been generally thought to be involved in the control of motor function (De Leonibus et al. 2001; Breysse et al. 2002) and motivational processes (Delgado et al. 2004; Di Chiara et al. 2004). For this reason, it has been commonly related to forms of learning that require the acquisition of a motor response or the ability to constitute associations between an instrumental response and a reward (Kelley et al. 1997; Hernandez et al. 2002; Andrzejewski et al. 2004). More recent studies, however, emphasized its role also in complex forms of learning and memory that require the flexible use of information. In particular it has been demonstrated that manipulations of this region induce deficits in a variety of learning tasks that require the processing of spatial information (Cools et al. 1993; Ploeger et al. 1994; Usiello et al. 1998; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Albertin et al. 2000; Roullet et al. 2001; De Leonibus et al. 2003b; Sargolini et al. 2003; Ragozzino and Choi 2004; Yin and Knowlton 2004). For example, pharmacological manipulations of the striatum have been proven to affect performance in the Morris water maze, in the radial maze, or in tasks of spatial displacement (Colombo et al. 1989; Sutherland and Rodriguez 1989; Ploeger et al. 1994; Shear et al. 1998; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Roullet et al. 2001; Sargolini et al. 2003; Yin and Knowlton 2004). Electrophysiological studies have consistently shown that in this region there are cells whose activity is driven by spatial information (Wiener 1993; Lavoie and Mizumori 1994; Shibata et al. 2001; Schmitzer-Torbert and Redish 2004; Mulder et al. 2005).

However, the striatum is not a homogeneous structure and can be differentiated both in terms of its intrinsic biochemical compartments (Sharp et al. 1986; Szele et al. 1991) and in terms of its connectivity, on the basis of the diverse afferent/efferent projections (Alexander et al. 1990; Joel and Weiner 1994, 2000; Adams et al. 2001; Herrero et al. 2002). This structural heterogeneity is paralleled by a functional diversity that has been demonstrated in several behavioral studies (Amalric and Koob 1987; Robbins et al. 1990; Reading et al. 1991; Maldonado-Irizarry and Kelley 1994; Devan and White 1999; Devan et al. 1999; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Burk and Mair 2001; Mair et al. 2002). In regard to spatial navigation, of particular interest are the differences between the two main components of the striatal complex, that is, the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens. In fact, while there is now substantial evidence of a role of both subregions in mediating spatial learning and memory (Potegal 1969; Whishaw et al. 1987; Sutherland and Rodriguez 1989; Packard and White 1990; Cools et al. 1993; Lavoie and Mizumori 1994; Maldonado-Irizarry and Kelley 1994; Ploeger et al. 1994; Devan et al. 1996, 1999; Gal et al. 1997; Setlow and McGaugh 1998, 1999; Devan and White 1999; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Roullet et al. 2001; Shibata et al. 2001; Ragozzino et al. 2002a,b; De Leonibus et al. 2003b; Sargolini et al. 2003; Mizumori et al. 2004; Palencia and Ragozzino 2004; Ragozzino and Choi 2004; Schmitzer-Torbert and Redish 2004; Yin and Knowlton 2004), the aspects of spatial information processing mediated by the two striatal components are still being debated.

Spatial learning leads to the constitution of an internal representation of the environment that allows navigation (Nadel and MacDonald 1980; Poucet 1993; Holscher 2003; Jacobs 2003). However, spatial navigation can be based on different sensory information and different coding systems. For example, if an allocentric frame of reference is used, coding of spatial information is independent of body position; conversely, egocentric spatial navigation requires the coding of information on the basis of body position (Poucet 1993; Moghaddam and Bures 1996). It has been demonstrated that these two frames of reference rely on distinct neural substrates as well as different sensory information (Kesner et al. 1989; Save et al. 1992, 2001; McDonald and White 1994; Devan et al. 1996; Save and Moghaddam 1996; de Bruin et al. 1997, 2001; Long and Kesner 1998).

On the basis of the distinct afferent projections to the nucleus accumbens and the dorsal striatum, it is conceivable that these two structures might contribute to the elaboration of a spatial representation on the basis of different frames of reference. This suggestion seems to be partially supported by behavioral evidence (Maldonado-Irizarry and Kelley 1994; Devan et al. 1996; de Bruin et al. 1997, 2001; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Mair et al. 2002). However, a direct comparison between them in spatial tasks requiring the use of allocentric or egocentric spatial representation has never been reported. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the effects of dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens manipulation in spatial memory consolidation, endeavoring to dissociate the two regions on the basis of the kind of coding system used. The task used was a modified version of the open-field object-place association task (Poucet 1989; Save et al. 1992; Roullet et al. 2001; De Leonibus et al. 2003b). In order to investigate the role of the two components of the striatum in processing different kinds of spatial information in this study, we altered the training procedure, varying the possibility of using self-centered spatial information to detect a spatial change (Thinus-Blanc et al 1992; De Leonibus et al. 2003b). By manipulating (Experiments 1 and 2) the place where the animal was introduced into the apparatus during habituation and testing, we assessed whether the constancy of the place of introduction into the arena could influence the spatial coding system used by the animals to discriminate the spatial change (Moghaddam and Bures 1996; De Leonibus et al. 2003b).

To compare the role of the two striatal regions in the consolidation of the different kinds of spatial information (Experiments 3-6), we administered focally different doses of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors' antagonist AP-5 immediately after the last habituation session, to animals always entering the arena from a constant location and to animals introduced from variable locations during training and testing. Then, 24 h after training, the mouse's ability to discriminate the spatial change was tested. NMDA receptors, indeed, are strongly present and have been shown to mediate memory consolidation in both regions (Packard and Teather 1997; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Roullet et al. 2001; De Leonibus et al. 2003a,b). The impact of such variables as rewards or behavior-related learning on task performance was minimized by using a kind of spatial task in which no explicit reward, no behavioral strategy, and no over-training were required. Furthermore, the time window chosen for pharmacological manipulation, which does not directly affect the animal while it is performing the task, should be particularly suitable for ruling out possible effects on behavioral or attentional processes.

Results

Experiment 1

All groups progressively reduced their locomotor activity over sessions in a similar way (Table 1) as indicated by a significant session effect (Session F3,72 = 131.906; p = 0.0001) but no other significant effect.

Table 1.

Experiments 1 and 2: Mean number of sector crossings (± SEM) during habituation sessions (S1 to S4) and mean duration of contacts (in seconds ± SEM) with the entire set of objects during habituation (S2-S4) and with the different Object Categories, displaced objects (DO), and nondisplaced objects (NDO), in the last session of habituation (S4), before the spatial change, and in the test session, after the object displacement (S5)

| Session

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locomotion

|

Habituation

|

S4

|

S5

|

|||||||||

| Experiment | Group (N) | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S2 | S3 | S4 | DO | NDO | DO | NDO |

| Experiment 1 | SP-SA (7) | 229 ± 24 | 145 ± 13 | 136 ± 16 | 97 ± 12 | 24.2 ± 2.0 | 13.8 ± 1.3 | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 5.9 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 0.8 |

| SP-DA (7) | 242 ± 20 | 154 ± 15 | 135 ± 11 | 117 ± 21 | 22.4 ± 1.7 | 12.9 ± 1.7 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 7.7 ± 1.6 | 13.9 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 0.6* | |

| DP-SA (7) | 263 ± 15 | 147 ± 4 | 120 ± 7 | 104 ± 8 | 21.2 ± 1.3 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.6 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 9.3 ± 0.9 | |

| DP-DA (7) | 244 ± 23 | 170 ± 18 | 154 ± 16 | 135 ± 15 | 21.7 ± 1.0 | 13.2 ± 0.9 | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 11.4 ± 1.0 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | |

| Experiment 2 | VP-SA (7) | 227 ± 17 | 129 ± 9 | 102 ± 7 | 96 ± 8 | 22.3 ± 0.3 | 12.8 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 1.1 |

| VP-DA (7) | 232 ± 31 | 156 ± 20 | 126 ± 19 | 107 ± 11 | 22.6 ± 1.2 | 11.6 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 8.1 ± 1.0 | 12.7 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.1* | |

Reactivity to the spatial change (S5) was always tested 24 h later S4. (*) p < 0.05 DO versus NDO within session and group. (SP-SA) Same Placement-Same Arrangement; (SP-DA) Same Placement-Different Arrangement; (DP-SA) Different Placement-Same Arrangement; (DP-DA) Different Placement-Different Arrangement; (VP-SA) Variable Placement-Same Arrangement; (VP-DA) Variable Placement-Different Arrangement.

Table 1 shows the mean values of objects exploration from Sessions 2 to 4 for all experimental groups. All groups showed a similar high level of objects exploration in Session 2, and a progressive reduction in the following sessions. Also in this case the ANOVA revealed only a significant effect of session (Session F2,48 = 225.808; p = 0.0001) (Table 1).

Table 1 shows the mean time of exploration of the two different Object Categories DO (displaced objects) and NDO (nondisplaced objects) for all experimental groups (Fig. 1) in the last habituation session (S4) and in the test session (S5) 24 h later. In the last session of habituation, all groups explored DO and NDO in a similar way. In the test session only the SP-DA (Same Placement-Different Arrangement) group explored DO significantly more than NDO (p = 0.0001). Figure 2A represents the re-exploration index, expressed as the mean time spent exploring each Object Category in S5 minus the mean time spent exploring the same Object Category in S4. The results clearly show that only the SP-DA group re-explored more DO than NDO. All other groups re-explored the two Object Categories for a similar amount of time. The statistical analysis of the re-exploration index revealed significant effects of the Arrangement (F1,24 = 9.035; p = 0.0061), of the Object Category (F1,24 = 5.845; p = 0.0236), and a significant interaction Object Category × Placement (F1,24 = 28.019; p = 0.0001), Object Category × Arrangement (F1,24 = 22.514; p = 0.0001), and Object Category × Placement × Arrangement (F1,24 = 33.001; p = 0.0001), but no significant effects of Placement or Arrangement × Placement interaction.

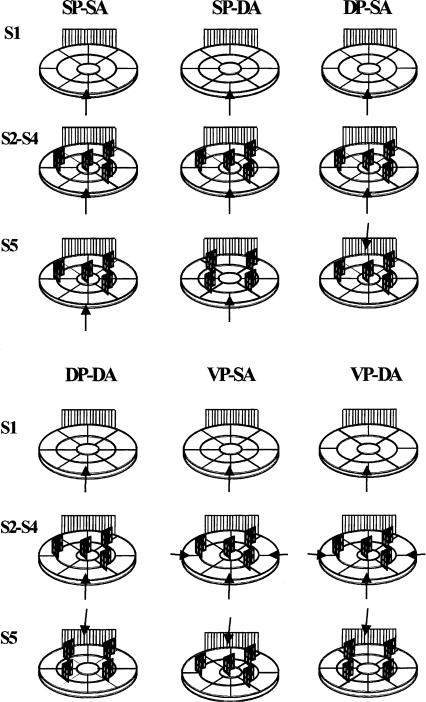

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the apparatus, the object positions, and the animal's point of introduction into the arena (black arrow) over successive sessions of habituation (S1-S4) and testing (S5) in the different experiments. (SP-SA) Same Placement-Same Arrangement; (SP-DA) Same Placement-Different Arrangement; (DP-SA) Different Placement-Different Arrangement; (DP-DA) Different Placement-Different Arrangement; (VP-SA) Variable Placement-Same Arrangement; (VP-DA) Variable Placement-Different Arrangement (see Materials and Methods for details).

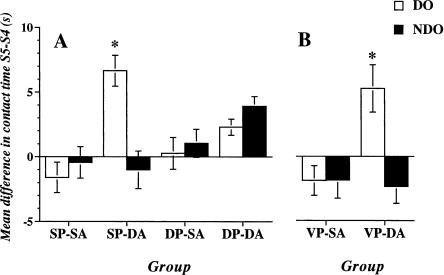

Figure 2.

Effect of the change of the animal's place of introduction into the open field on reactivity to spatial change. (A) Experiment 1: reactivity to a spatial change in mice in which the place of introduction into the arena was kept invariant during training on day 1. The groups differed on whether in the test session, 24 h later, the place of animal introduction was kept constant compared to training sessions, and if in the test session the object's arrangement was varied or left unchanged. (SP-SA) Same Placement-Same Arrangement; (SP-DA) Same Placement-Different Arrangement; (DP-SA) Different Placement-Different Arrangement; (DP-DA) Different Placement-Different Arrangement. (B) Experiment 2: reactivity to a spatial change in mice entering the arena, during training, always from a different quadrant. The group differed in whether in the test session the spatial arrangement of the objects was varied or left unchanged. (VP-SA) Variable Placement-Same Arrangement; (VP-DA) Variable Placement-Different Arrangement. The histograms illustrate the mean time (±SEM) spent exploring displaced (DO) and nondisplaced (NDO) objects in S5 minus the time spent exploring the same Object Category in S4. (*) p < 0.05 DO versus NDO same experimental group.

Experiment 2

Changing the animals' place of introduction during acquisition did not affect locomotor activity during the habituation sessions (Table 1). In fact, as in Experiment 1, the animals in both groups progressively decreased locomotor activity from Session 1 to Session 4, as confirmed by the ANOVA that revealed only a significant session effect (F3,36 = 58.899; p = 0.0001).

Changing the animals' place of introduction over sessions did not affect the ability of mice to become accustomed to the objects or objects' configuration from Sessions 2 to 4 (Table 1). As in the previous experiment, animals in both groups showed high levels of objects exploration in Session 2, which progressively decreased across sessions. Also in this case, ANOVA revealed only a significant effect of session (Session F2,24 = 373.967; p = 0.0001).

Table 1 shows the mean time spent by the animals of the different groups (Fig. 1) exploring the two different Object Categories (DO and NDO) in the last session of habituation (S4) and in the test session (S5). No major within-group difference was observed in DO and NDO exploration in S4. In S5, only the group Variable Placement-Different Arrangement (VP-DA), which was exposed to the change in the objects' configuration, explored DO significantly more than NDO (p = 0.0001). Figure 2B shows the re-exploration indexes of the two Object Categories (DO and NDO), expressed as mean time spent exploring each Object Category in S5 minus the mean time spent exploring the same Object Category in S4. The group Variable Placement-Same Arrangement (VP-SA) did not re-explore the two Object Categories in S5; on the contrary, the group VP-DA selectively re-explored DO, but not NDO. The statistical analysis on the re-exploration index revealed a significant effect of Object Category (F1,12 = 49.874; p = 0.0001) and a significant interaction between Object Category × Arrangement (F1,12 = 50,948; p = 0.0001) but no significant effect of the Arrangement.

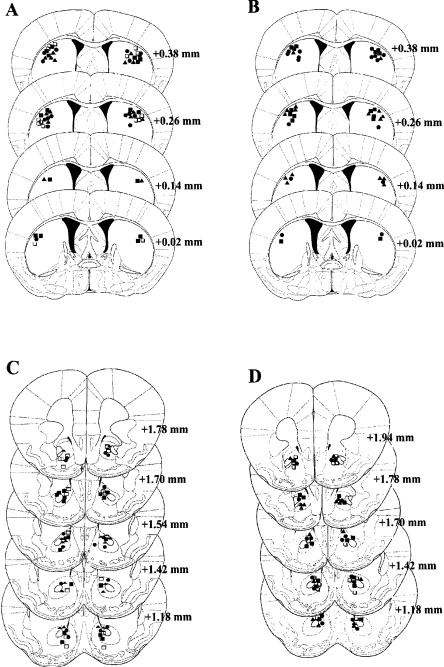

Histological verifications

Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the injector placements for Experiments 3-6, indicating the most ventral point for each injector track in the different groups. In Experiments 3 (Fig. 3A) and 4 (Fig. 3B), injector placements were located in the medio-lateral component of the dorsal striatum. No major difference in injector placement distribution was evident among groups in each experiment or between the two experiments. Histological analysis showed that the injector tracks in control and treated animals were evenly distributed also in Experiments 5 (Fig. 3C) and 6 (Fig. 3D). The majority of the tracks were localized in the core rather than in the shell of the nucleus accumbens. Only those animals displaying a correct injector placement were included in the statistical analysis.

Figure 3.

Sketch of coronal sections from animals in the four experiments. Each symbol represents an injector placement. The numbers indicate the anteroposterior coordinate relative to bregma according to Franklin and Paxinos (1997). (A) Injector placements in Experiment 3; (B) injector placements in Experiment 4; (C) injector placements in Experiment 5; (D) injector placements in Experiment 6. The symbols indicate mice administered (▪) saline; (□) AP-5, 37.5 ng; (▴) AP-5, 75 ng; (•) AP-5, 150 ng.

Experiment 3: Effects of intra-striatal AP-5 administration on discrimination of a spatial change in mice introduced into the open field always from the same quadrant

The four groups showed similar levels of locomotor activity and a similar reduction over sessions before saline or AP-5 injections (data not shown). Table 2 shows the mean time of objects exploration in the three sessions of habituation before treatment. Mice in all groups showed a similar level of objects exploration in S2, and all showed a decrease in the time spent in contact with the objects over the session. The one-way ANOVA for repeated measures revealed only a significant session effect but no other significant effect for either locomotion (Session F3,84 = 159.288; p = 0.0001) or habituation (Session F2,56 = 296.935; p = 0.0001).

Table 2.

Experiment 3, 4, 5, and 6: Mean duration of contacts (in seconds ± SEM) with the entire set of objects during habituation (S2-S4) and with the different Object Categories, displaced objects (DO), and nondisplaced objects (NDO), in the last session of habituation (S4), before the spatial change, and in the test session, after the object displacement (S5)

| Session

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habituation

|

S4

|

S5

|

||||||

| Experiment | Treatment (N) | S2 | S3 | S4 | DO | NDO | DO | NDO |

| Experiment 3 | Saline (8) | 21.3 ± 1.5 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 7.6 ± 0.7* |

| Dorsal striatum | 37.5 ng AP-5 (8) | 21.6 ± 1.1 | 11.2 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 12.5 ± 1.0 | 8.7 ± 1.0* |

| 75 ng AP-5 (8) | 21.8 ± 1.6 | 11.1 ± 1.7 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 11.5 ± 2.0 | 12.0 ± 1.9Φ | |

| SP-DA | 150 ng AP-5 (8) | 19.9 ± 2.3 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 9.8 ± 1.1Φ | 10.3 ± 1.4Φ |

| Experiment 4 | Saline (8) | 20.6 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 11.8 ± 1.9 | 7.8 ± 1.1* |

| Dorsal striatum | 75 ng AP-5 (8) | 18.8 ± 1.3 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 12.4 ± 0.9 | 8.4 ± 1.1* |

| VP-DA | 150 ng AP-5 (8) | 20.3 ± 0.9 | 10.8 ± 0.9 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 1.0* |

| Experiment 5 | Saline (8) | 22.5 ± 1.8 | 10.1 ± 1.0 | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 13.4 ± 2.3 | 7.2 ± 1.0* |

| Nucleus accumbens | 37.5 ng AP-5 (8) | 24.7 ± 1.7 | 13.7 ± 2.5 | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 12.9 ± 2.4 | 7.7 ± 1.5* |

| 75 ng AP-5 (8) | 22.7 ± 0.9 | 11.6 ± 2.0 | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 12.5 ± 1.9 | 11.1 ± 1.7 | |

| SP-DA | 150 ng AP-5 (8) | 22.2 ± 1.2 | 11.1 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 1.1 | 11.7 ± 1.4 | 13.5 ± 2.2Φ |

| Experiment 6 | Saline (8) | 20.4 ± 0.7 | 9.6 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 13.5 ± 0.9 | 8.3 ± 1.0* |

| Nucleus accumbens | 37.5 ng AP-5 (8) | 18.5 ± 1.4 | 10.5 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 9.2 ± 1.0Φ | 6.1 ± 0.8* |

| 75 ng AP-5 (8) | 20.0 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 1.0Φ | 7.2 ± 0.7 | |

| VP-DA | 150 ng AP-5 (8) | 19.0 ± 0.9 | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 7.0 ± 0.9Φ | 6.9 ± 0.7 |

The drug treatment was always performed immediately after Session 4. Reactivity to the spatial change (S5) was always tested 24 h later S4. (*) p < 0.05 DO versus NDO within session and group. (Φ) p < 0.05 AP-5 versus saline within the same Object Category in S5. (SP-DA) Same Placement-Different Arrangement; (VP-DA) Variable Placement-Different Arrangement.

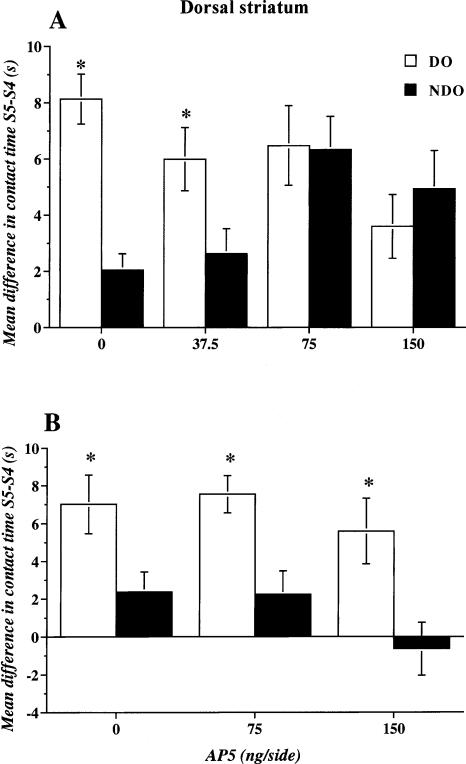

The mean time of exploration of the two Object Categories, DO and NDO, before (S4) and after (S5) the spatial change, is shown in Table 2. DO exploration did not differ from NDO exploration in S4 in any of the experimental groups. After the spatial change, in S5 only animals with saline or the lowest dose of AP-5 (37.5 ng) administered in the striatum explored DO more than NDO. The mice administered with the two highest doses of AP-5 in S5 spent more time in contact with the nondisplaced objects than control mice. Compared to controls, the group of animals injected with 150 ng/side also showed reduced time spent in contact with the displaced objects. This is confirmed by the analysis of the re-exploration index (Fig. 4A). The mice administered with the two highest doses of AP-5 showed a similar level of re-exploration as the two Object Categories in S5. In particular in both cases, compared to saline control, an increase in the time spent re-exploring the NDO Object Category was observed. The ANOVA of the re-exploration index revealed a significant effect of the Object Category (F1,28 = 23.285; p = 0.0001) and a significant interaction between the two factors (F3,28 = 15.063; p = 0.0001), but no significant effect of treatment.

Figure 4.

Reactivity to spatial change of mice administered immediately post-training with saline or different doses of the NMDA competitive antagonist AP-5 (37.5, 75, 150 ng/side) within the dorsal striatum. (A) Experiment 3: effects in mice entering the arena during training and testing always from the same quadrant (Same Placement-Different Arrangement procedure). (B) Experiment 4: effects in mice entering the arena during training and testing, always from a different quadrant (Variable Placement-Different Arrangement procedure). The histograms represent the mean time (±SEM) spent exploring displaced (DO) and nondisplaced (NDO) objects in S5 minus the time spent exploring the same Object Category in S4. (*) p < 0.05 DO versus NDO same drug treatment.

Experiment 4: Effects of intra-striatal AP-5 administration on the discrimination of a spatial change in mice introduced into the open field always from a different quadrant

Before treatment, locomotor activity progressively decreased over sessions (S1 to S4) in all groups (data not shown). Statistical analysis revealed only a significant effect of session (Session F2,63 = 117.780; p = 0.0001). Table 2 shows the mean values of objects exploration in the three sessions of habituation before intra-striatal administration of AP-5 or saline. The variable of place of introduction of the animals into the open field did not affect the ability of mice to become accustomed to the objects. No major intra-group difference was observed in the exploration of the objects in S2, and animals in all groups progressively reduced the time spent in contact with the objects over sessions. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed only a significant effect of session (F2,42 = 250.136; p = 0.0001).

Table 2 shows the mean values for the time spent exploring the two Object Categories (DO and NDO) before (S4) and after (S5) the spatial change in mice introduced into the open field from a different quadrant each session. In S4, all groups explored DO and NDO for the same length of time. Then, 24 h later, saline-injected mice explored the DO category more than the NDO, as was found with the VP-DA group in Experiment 2. Intrastriatal administration of AP-5 did not alter the time spent in contact with the two Object Categories in S5 and like control mice, both groups explored DO more than NDO. Figure 4B shows the re-exploration index for the two Object Categories in mice administered with saline or AP-5 within the striatum. Saline control re-explored DO more than NDO, and AP-5 did not alter the behavior of the animals at either of the two doses. The one-way ANOVA for repeated measures revealed a significant effect of Object Category (F1,21 = 145.279; p = 0.0001), but no significant effects of Treatment or Treatment × Object Category interaction.

Experiment 5: Effects of intra-accumbens AP-5 administration on discrimination of a spatial change in mice introduced into the open field always from the same quadrant

On day 1, before drug treatment, animals from all groups reduced locomotor activity (data not shown) and objects exploration (Table 2) in a similar way across habituation sessions (S2-S4). Statistical analysis of locomotor activity revealed a significant effect of session (F3,84 = 146.840; p = 0.0001). Likewise, the statistical analysis of habituation revealed only a significant effect of session (Session F2,56 = 187.336; p = 0.0001).

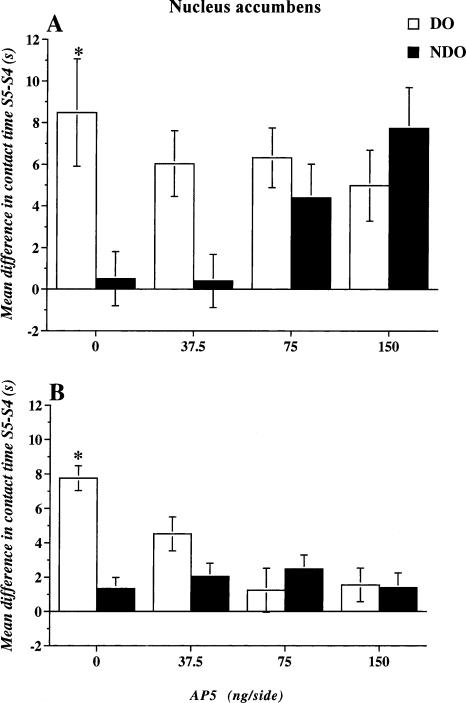

Mean values of time spent by the animals exploring the two Object Categories in Session 4, as reported in Table 2, indicate that, before the spatial change, animals assigned to the different groups did not show any preference for either Object Category. Then, 24 h later, in S5, after the spatial change, only mice focally injected immediately after the last session of habituation with saline or low-dose AP-5 (37.5 ng) explored DO more than NDO. Conversely, the groups with the two highest doses of AP-5, 75 and 150 ng administered within the nucleus accumbens in S5, showed a comparable level of exploration of the two Object Categories (Table 2).

Figure 5A shows the re-exploration index for the different Object Categories in S5 after intra-accumbens administration of saline or different doses of AP-5. Only the mice injected with saline immediately after the last habituation session (S4), 24 h later showed a significant difference between DO and NDO in the test session (S5). All other groups re-explored the two Object Categories for a similar length of time. Interestingly, this effect was due to a dose-dependent increase in the re-exploration of NDO rather than a decrease in DO. The ANOVA revealed no significant effect of treatment, but significant effects of Object Category (F1,28 = 10.858; p = 0.0001) and a significant interaction between the two factors (F3,28 = 5.845; p = 0.003).

Figure 5.

Reactivity to spatial change of mice administered immediately post-training with saline or different doses of the NMDA competitive antagonist AP-5 (37.5, 75, 150 ng/side) within the nucleus accumbens. (A) Experiment 3: effects in mice entering the arena, during training and testing, always from the same quadrant (Same Placement-Different Arrangement procedure). (B) Experiment 4: effects in mice entering the arena during training and testing, always from a different quadrant (Variable Placement-Different Arrangement procedure). The histograms represent the mean time (±SEM) spent exploring displaced (DO) and nondisplaced (NDO) objects in S5 minus the time spent exploring the same Object Category in S4. (*) p < 0.05 DO versus NDO same drug treatment.

Experiment 6: Effects of intra-accumbens AP-5 administration on discrimination of a spatial change in mice introduced into the open field always from a different quadrant

All groups of mice tested in this experiment progressively reduced locomotor activity across habituation sessions (data not shown). The one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of session (F3,84 = 53.882; p = 0.0001), but no significant treatment effect, or interaction between the two factors. Table 2 illustrates the mean time of exploration of the objects during the three sessions of habituation (from S2 to S4), before drug treatment. Like the other experiments, all groups had high levels of objects exploration in S2 that progressively decreased over sessions. The one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed only a significant effect of session (F2,56 = 403.622; p = 0.0001).

Table 2 shows the mean time of objects exploration for the two different Object Categories, in the last session of habituation before saline or AP-5 intra-accumbens administration and 24 h later in S5, when the mice were subjected to the spatial change. In Session 4, all groups explored the two Object Categories for a similar length of time. In S5, only mice injected with saline and 37.5 ng of AP-5 explored significantly more DO than NDO, while animals injected with the two highest doses of the NMDA antagonist explored the two Object Categories for a similar length of time. Unlike what was observed in Experiment 5, in this case the lack of selectivity in the exploration of the two Object Categories was due to a dose-dependent decrease in the exploration of DO.

Figure 5B shows the effect of intra-accumbens administration of saline or AP-5 on the re-exploration index of the two Object Categories of mice introduced into the open field always from different quadrants during habituation on day 1 and tested 24 h later. Saline administered animals re-explored displaced objects more than nondisplaced objects, while all other groups re-explored the two Object Categories for a similar length of time. ANOVA revealed significant effects of Treatment (F3,28 = 3.375; p = 0.0322), Objects Category (F1,28 = 17.300; p = 0.0003), and also of Object Category × Treatment interaction (F3,28 = 12.626; p = 0.0001).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of the NMDA receptors located within the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens in the consolidation of different kinds of spatial information. In the first two experiments, we demonstrated that, in a task requiring the detection of a configurational change, mice constantly introduced into the arena from the same quadrant during habituation did not discriminate the spatial change if in the test session they were introduced into the arena from a different location. On the contrary, if the animals were introduced into the arena always from a different quadrant during habituation, their ability to discriminate the spatial change was not altered in the test session when they were introduced from a new position. These results indicate that, by using the two behavioral procedures, the animals rely, respectively, on an egocentric and an allocentric spatial frame of reference.

By blocking the NMDA receptors within the dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens, we found an involvement of both components of the striatum in the discrimination of a configurational change in the objects' disposition. Furthermore, we demonstrated a partial dissociation between the two components of the striatum, indicating that the dorsal striatum might play a role in the consolidation of spatial information only when the relevance of the self-centered spatial information needed to solve the task increases. Conversely, the activation of the NMDA receptors within the nucleus accumbens was necessary for the consolidation of spatial information, independently of the frame of reference used.

Role of the point of animal introduction into the arena in determining the spatial coding system used for spatial discrimination

The purpose of the first two experiments was to implement two different behavioral procedures to encourage the animals to use different kinds of spatial information. Behavioral and electrophysiological data suggest that the subject's place of introduction into the environment can induce the preferential use of an egocentric or an allocentric coding system (Whishaw et al. 1987; Sharp et al. 1990; Moghaddam and Bures 1996; Holdstock et al. 2000; De Leonibus et al. 2003b; Gaffan et al. 2003). Accordingly we found (Experiment 1) that animals subjected to the spatial change from the same position as during habituation (SP-DA group) selectively reacted to the spatial change, exploring far more DO than NDO. The selective re-exploration of displaced objects is generally interpreted as the animal's ability to use the internal spatial representation of the objects' configuration acquired during training to discriminate the change (Thinus-Blanc et al. 1992; Roullet et al. 2001; De Leonibus et al. 2003b). Indeed, when no changes occur, as for the Same Placement-Same Arrangement (SP-SA) group, in the test session animals continue to reduce object exploration compared with the last session of habituation. These results are in agreement with previous observations carried out with animals tested in similar tasks (Save et al. 1992; Thinus-Blanc et al. 1992; Roullet et al. 2001; De Leonibus et al. 2003b). It should be noted, however, that in these studies the animal could generally rely on two different kinds of change, object displacement and configurational change. Using four identical objects, we expanded these observations to demonstrate that mice are able to selectively react to a purely configurational change.

Unlike the Same Position-Different Arrangement group (SP-DA), animals exposed to spatial change from a different location vis-à-vis the one experienced during habituation (Different Placement-Different Arrangement [DP-DA] group) were not able to discriminate the change; indeed, they re-explored the two Object Categories for a similar length of time. This finding confirms previous results obtained in hamsters and demonstrates that the ability to discriminate the spatial change depends on the consistency in the animal's place of introduction during habituation and testing (Thinus-Blanc et al. 1992). Thus, it could be inferred that introducing the animals into the arena from a fixed location induces the preferential use of an egocentric frame of reference.

Interestingly, in Experiment 2, both groups, although introduced from a different quadrant each session during habituation, reduced locomotor activity and object exploration—a pattern similar to that observed when the animals were consistently introduced from a constant location. This confirms that changing the animal's place of introduction during habituation does not affect the animal's ability to adapt to the objects and the arena (De Leonibus et al. 2003b). Not surprisingly, the VP-SA group, which in the test session 24 h later was subjected to the same objects' configuration, showed a negative re-exploration index; in other words, the animals continued to be habituated to the objects. On the other hand, the group VP-DA re-explored the displaced objects far more than the nondisplaced objects. This result confirms and extends previous observations (De Leonibus et al. 2003b), demonstrating that experiencing the change of spatial configuration from a new starting quadrant does not per se impair the ability to discriminate it.

Therefore, in Experiment 1 we demonstrated that mice always introduced into the open field from the same location during training selectively re-explore the displaced objects only if they experience the change from the same quadrant. On the other hand, the discrimination of the spatial change seems independent of the animal's actual position in the test session if it always experiences the open field from different locations during training (Experiment 2). The DP-DA and VP-DA groups were both subjected to a spatial change from a new quadrant relative to the one from which they experienced the open field during habituation. They differed only in the way they were introduced into the open field during the training sessions and thus in the way they acquired the information relative to the objects' configuration. However, only the mice of the VP-DA group were able to selectively re-explore the displaced objects. These results strongly point to the use of two different frames of reference in the animals trained using the two procedures. Furthermore, they suggest that self-centered information might play a more substantial role in spatial discrimination only when the place of introduction of the animals is kept constant during training (De Leonibus et al. 2003b).

Effects of post-training dorsal striatal and nucleus accumbens NMDA receptors' blockade on spatial discrimination in an egocentric and in an allocentric task

Focal administration of the NMDA receptors' antagonist AP-5 within the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens impaired the ability of mice to react to the spatial change. However, this impairment was not observed in all experiments. In particular, focal injections within the dorsal striatum induced a deficit in the ability to discriminate a change in the spatial configuration of the objects only if the animals were always introduced into the open field from a constant location during habituation and testing. In fact, in Experiment 3, mice administered with the two highest doses of AP-5 immediately after the last session of habituation, 24 h later re-explored DO and NDO for a similar length of time. Instead, when the place of introduction of the animals was varied over sessions, intra-striatal AP-5 administration immediately after the last session of habituation did not alter the exploration pattern of the animals. Indeed, in Experiment 4, mice injected with AP-5 re-explored DO more than NDO in S5, like saline controls, thus indicating that they were still able to discriminate the spatial change.

Interestingly, intra-accumbens administration of AP-5 impaired spatial change discrimination in animals experiencing the object configuration always from the same quadrant, as well as in mice experiencing it always from a different quadrant in the three sessions of habituation. AP-5-administered animals, in fact, in both experiments re-explored the two Object Categories for a similar length of time, without showing any kind of selectivity in the exploration. Therefore, unlike what was observed after intradorsal striatum AP-5 injections, nucleus accumbens NMDA receptors' blockade induced a spatial memory impairment independently of the frame of reference used to solve the task.

A possible interpretation of the results obtained after intra-accumbens administration of the NMDA antagonist is that the two behavioral procedures require the same kind of spatial information to be processed. This interpretation, however, would contradict the results obtained after intra-striatal administration in the two procedures as well as in the behavioral study, indicating that the selective re-exploration of DO is differentially sensitive to the animal's position inside the arena. Furthermore, intra-accumbens injections of AP-5 induced two different responses in mice trained using the two procedures. In the variable place of introduction procedure, AP-5-treated animals decreased the time spent in contact with the displaced objects. On the contrary, when a constant place of introduction was used, AP-5 treated animals re-explored both Object Categories for a similar length of time.

As already noted, in the egocentric procedure, AP-5 administration induced a renewal of exploration of both Object Categories, and this effect was independent of the site (dorsal striatum or nucleus accumbens) of injection. These results suggest a possible spread of the drug between the two striatal subregions. However, we chose an injection volume of 0.1 μL per side, which should reduce the probability of drug diffusion. Furthermore, if the drug diffusion could account for this finding, a similar impairment should have been observed after drug administration in the two regions even when the mice were trained with the allocentric procedure, which was not the case.

Therefore, in our opinion, three main conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, they suggest a role of the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens in the consolidation of spatial information. This would be in agreement with previous observations demonstrating an involvement of the dorsal striatum (Colombo et al. 1989; Devan et al. 1996, 1999; Devan and White 1999; De Leonibus et al. 2003b) and the nucleus accumbens (Sutherland and Rodriguez 1989; Maldonado-Irizarry and Kelley 1994; Ploeger et al. 1994; Setlow and McGaugh 1998; Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Albertin et al. 2000; Sargolini et al. 2003) in processing spatial information. Second, they provide evidence of a partial dissociation between the two components of the striatum in processing information acquired through the two different frames of reference. Finally, they support the view that both in the ventral and in the dorsal striatum the activation of the NMDA receptors during the post-trial period is critical in consolidating this information. It should be mentioned that on the basis of the present results we cannot exclude that the deficits observed are possibly due to proactive drug effects on the test day. However, a selective role of NMDA receptors located within the dorsal and ventral striatum in spatial memory consolidation would be consistent with previous studies demonstrating that immediate, but not 2 h, post-training administration of AP-5 within these structures impairs performance in spatial learning tasks 24 h later (Packard and Teather 1997; Roullet et al. 2001).

Role of dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens in spatial memory consolidation

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a full dissociation between dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens in allocentric spatial memory in the same task. Indeed, very few studies in the literature directly compare the effects of dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens manipulation in spatial information processing (Smith-Roe et al. 1999; Mair et al. 2002). Nevertheless, the present findings confirm previous results reported in the literature. Lesions or pharmacological manipulation of the dorsal striatum have actually generally been found to be ineffective in impairing spatial memory in tasks requiring the processing of allocentric information, such as the Morris water maze (Packard and Teather 1997), the cross maze (Packard 1999), or a task similar to the one used in the present study (De Leonibus et al. 2003b). On the contrary, deficits in the processing of allocentric spatial information after nucleus accumbens manipulation have been demonstrated in the radial maze (Gal et al. 1997; Smith-Roe et al. 1999), in a spatial version of the hole board (Maldonado-Irizarry and Kelley 1994), or in the Morris water maze (Sutherland and Rodriguez 1989; Setlow and McGaugh 1998; Sargolini et al. 2003).

The second interesting observation that emerges from this study is the lack of dissociation between dorsal and ventral striatum in the consolidation of spatial information acquired through an egocentric frame of reference. From the neuroanatomical point of view, the dorsal striatum receives convergent inputs from several associative regions of the cortex, but also from the motor and primary sensory cortex (Divac et al. 1977; McGeer et al. 1977; Donoghue and Herkenham 1986). Furthermore, projections from the vestibular system have been demonstrated to this component of the striatum (Carelli and West 1991; Lai et al. 2000). The nucleus accumbens, instead, receives afferent inputs from the pre-frontal cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala and thalamic nuclei (Zahm and Brog 1992; Brog et al. 1993). This pattern of afferentation provides the neuranatomical substrate needed to explain the involvement of both regions in the processing of egocentric information. In fact, on the one hand, vestibular, motor, and kinesthetic information has been demonstrated to be essential for an egocentric coding of space (Potegal et al. 1971; Potegal 1972; Bures et al. 1997; Whishaw et al. 1997, 2001). On the other hand, behavioral studies have demonstrated that the prefrontal cortex plays a pivotal role in spatial navigation based on an egocentric frame of reference (Kesner et al. 1989; Save and Moghaddam 1996; de Bruin et al. 1997, 2001; Save et al. 2001).

An interesting issue raised by this result is whether the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens accomplish different operations and the kind of interaction between the two regions in egocentric spatial coding. The different afferent projections to the two structures make it conceivable that distinct information is relayed to the two structures. The fact that vestibular and sensory-motor information are conveyed to the dorsal, but not to the ventral striatum, places the former in an ideal position for the processing of sensory information necessary for elemental egocentric representations (Atallah et al. 2004). Conversely, the inputs from the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex to the ventral striatum would provide this structure with highly processed spatial representations, independently of the kind of information needed to elaborate them. This would be consistent with the present data demonstrating a role of the nucleus accumbens in both egocentric and allocentric spatial memory. In this frame-work, it could be further speculated that the nucleus accumbens is recruited when possible different spatial information/strategies can be used in order to select the most appropriate one. The hypothesis would explain the contradictory results present in the literature relative to an involvement of the two striatal components in spatial learning and memory depending on the spatial task used.

In both animals and humans, a functional dissociation among neural structures in terms of coding of egocentric and allocentric spatial information has been suggested (Kesner et al. 1989; Poucet 1993; Packard 1999; Holdstock et al. 2000). The effects observed using the two procedures after nucleus accumbens manipulation, on the contrary, indicate a lack of segregation within this structure. However, it should be noted that, on a biochemical basis, the nucleus accumbens has been distinguished into a lateral and a medial component, respectively, core and shell, that have been demonstrated to differ also in their input-output connectivity (Zahm and Brog 1992; Brog et al. 1993). This distinction is paralleled by functional differences that liken the core of the accumbens to the dorsal striatum while the shell has been suggested to be related to more limbic functions (Zahm and Brog 1992; Kelley et al. 1997). Furthermore, although only a few studies have compared the effects of core and shell manipulations in spatial learning and memory, differences between the two components have been reported (Maldonado-Irizarry and Kelley 1994; Smith-Roe et al. 1999). Likewise, most of the studies reporting an involvement of the dorsal striatum in spatial memory suggest a functional segregation between the dorsomedial and the lateral components referring to the dorsomedial compartment as the one mediating spatial functions (McDonald and White 1994), while our injection sites were mainly located in the lateral striatum. In the present study, most of the injections were aimed at the core of the nucleus accumbens and at the dorso-lateral striatum; however, despite the low volume of injection, it is difficult to completely exclude a spread of the drug to the shell or the medial striatum. Therefore, it should be verified whether a more subtle distinction than the ones analyzed in this study within the accumbens and in general within the striatal complex could underlie the processing of different kinds of information.

In conclusion, the present findings, on the one hand, point to a distinction between the dorsal and ventral striatum in the processing of allocentric spatial information; on the other hand, they demonstrate a functional similarity between the two striatal components in the consolidation of egocentric spatial information. Therefore, taken as a whole, they suggest a complex array of interactions among the different regions of the striatal complex, depending on the kind of information.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The subjects used in the present study were CD1 outbred male mice from Charles River (Como, Italy). Upon arrival they were housed in groups of 12 in standard breeding cages (42 × 26 × 21.8 cm), placed in a rearing room at a constant temperature (22° ± 1°C), and maintained on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle starting at 7:30 a.m., with food and water available ad libitum. At the time of the experiment, they were ∼8-9 wk old and their weights ranged from 30 to 35 g.

Every possible effort was made to minimize animal suffering, and all procedures were in strict accordance with European Community laws and regulations on the use of animals in research and NIH guidelines on animal care.

Surgery

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of chloral hydrate (500 mg/kg; Fluka) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments) with mouse adapter and lateral ear bars. The mice were bilaterally implanted with 7-mm-long bilateral stainless steel cannulae 2 mm dorsal to the dorsal striatum or the nucleus accumbens. The stereotaxic coordinates used were AP = +0.4 mm; L = ±2.5 mm, DV = -1.0 mm; and AP = +1.6 mm, L = ±1 mm, DV = -2.2 mm relative to bregma, respectively, for the dorsal striatum and the nucleus accumbens, according to the atlas of Franklin and Paxinos (1997). Guide cannulae were secured in place with dental cement. Mice were then allowed to recover for 5-7 d in groups of four in standard breeding cages (25 × 20 × 14 cm).

Apparatus and behavioral procedure

The apparatus was the same for all the experiments (Fig. 1). It consisted of a circular open field, 60 cm in diameter, with a 30-cm-high wall made of plastic material, and the floor was divided into 19 sectors by black lines. A conspicuous striped pattern 30 cm wide and 30 cm high (alternating 1.5-cm-wide vertical white and black bars) was attached to the wall of the open field. The open field was placed in a soundproof cubicle (1.10 × 1.10 m and 2 m high) and surrounded by several distal cues (a video camera, a darkened window, several shelves located on two of the walls, a light, an extension cord with multiple plugs, etc.). The apparatus was illuminated by a red light (80 W) located on the ceiling. A video camera, above the open field, was connected to a video recorder and a monitor. Four identical objects were simultaneously present in the open field. The object consisted of a black angle iron on a transparent base with four holes for each side (diameter 5 cm, 7 cm high).

The mice were always tested during the light period (between 09:00 and 17:00). Mice were individually subjected to five sessions lasting 6 min each, distributed over two consecutive days. On the first day (exploration phase), mice were subjected to four consecutive sessions at 3-min intervals during which they were returned to a waiting cage located inside the test room. During the first session, mice were placed in the empty open field to allow them to familiarize themselves with the apparatus. During Sessions 2 to 4, the four objects were placed inside the open field as shown in Figure 1. After the last session of the exploration phase, the animals were returned to their home cage and left undisturbed until the next day. Then, 24 h later, the mice were again placed in the arena and subjected to the test session (Session 5).

Drugs and focal administration procedure

The doses of the NMDA antagonist used were chosen on the basis of preliminary experiments as well as of previous studies demonstrating the efficacy of the same doses in impairing spatial memory consolidation (Roullet et al. 2001; De Leonibus et al. 2003b). D-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP-5; RBI, USA) was dissolved in saline solution; control mice were injected with the same volume of saline. The doses of AP-5 used in this study were 37.5, 75, and 150 ng per side. In Experiment 4, only the two highest doses were used.

Mice were always injected immediately after Session 4 in the dorsal striatum or nucleus accumbens with either saline or AP-5. A 9-mm-long injector connected with polyethylene tubing to a 1.0-μL Hamilton syringe was lowered into the guide cannula. A volume of 0.1 μL of drug or saline was then infused on one side and then the other. Each infusion lasted for 1 min and was followed by 1 min of diffusion time with the injector left in place. After the injections, animals were returned to their home cage and left undisturbed until the next day.

Data collection

Data collection was performed using video recordings and ad hoc Macintosh software by an observer blind to the treatment. In all sessions, locomotor activity was recorded by counting the number of sector crossings. From Sessions 2 to 5, object exploration was evaluated on the basis of the mean time spent by the animals in contact with the different objects. A contact was defined as the snout of the subject actually touching an object. In Sessions 4 and 5, the exploration time was considered as the mean time of exploration for the two Object Categories: displaced (DO) and nondisplaced (NDO) objects. The animals' ability to selectively react to the spatial change was analyzed by calculating the mean time of exploration of each Object Category in Session 5 minus the mean time of exploration of the same Object Category in Session 4—re-exploration index (DO [S5] - DO [S4] = DO and NDO [S5] - NDO [S4] = NDO) (Roullet et al. 2001).

Experimental groups

Experiment 1

Animals were randomly distributed among four groups. During the training phase (S2-S4), animals were always introduced into the open field from the same quadrant, and all groups were subjected to the same objects' configuration. The groups differed according to whether the place of animal introduction was kept constant in the test session compared to training sessions and if in the test session the objects' configuration was varied or left unchanged. In particular, animals of group 1, Same Placement-Same Arrangement group (SP-SA, n = 7), in the test session were introduced into the arena from the same position and exposed to the same objects' configuration as during habituation. Animals of group 2, the Same Placement-Different Arrangement group (SP-DA, n = 7) were introduced from the same location in the test session as in the habituation phase but were subjected to a different objects' configuration. Animals of group 3, the Different Placement-Same Arrangement group (DP-SA, n = 7), were exposed to the same objects' configuration in the test session but from a different location. Finally, animals of group 4, the Different Placement-Different Arrangement group (DP-DA, n = 7), were subjected to the spatial change from a different place of introduction in the test session (Fig. 1).

Experiment 2

Animals were always introduced from a different quadrant in all sessions, during both training and testing. The groups differed according to whether, in the test session 24 h after training, objects' configuration was varied or left unchanged. In particular, the mice of group 1, the Variable Placement-Same Arrangement group (VP-SA, n = 7), were subjected to the same spatial configuration of the objects in the test session. The mice of group 2, the Variable Placement-Different Arrangement group (VP-DA, n = 7), were exposed to a different objects' arrangement in the test session (S5) (Fig. 1).

Experiment 3

Mice were always introduced into the arena from the same quadrant (Same Placement-Different Arrangement/SA-DA procedure) in all five sessions; immediately after Session 4, saline or three doses of AP-5 were injected into the dorsal striatum and the mice were tested 24 h later.

Experiment 4

Mice were introduced into the arena from a different quadrant in each session (Variable Placement-Different Arrangement/VP-DA procedure); immediately after the last habituation session, saline or two different doses of AP-5 were injected into the dorsal striatum.

Experiment 5

Animals were always introduced into the open field from the same quadrant (Same Placement-Different Arrangement/SA-DA procedure) and immediately after training, saline or three doses of AP-5 were injected focally into the nucleus accumbens.

Experiment 6

Immediate post-training injections of saline or three doses of AP-5 were made into the nucleus accumbens of mice entering the arena from a different quadrant each session (Variable Placement-Different Arrangement/VP-DA procedure).

Statistics

Experiment 1

Locomotor activity, habituation, DO-NDO exploration in S4 and S5, and the re-exploration index were analyzed using a two-way, repeated measures ANOVA with Placement (two levels: Same Placement, Different Placement) and Arrangement (two levels: Same Arrangement, Different Arrangement) as between-groups factors. The repeated measures were Session (four levels: Session 1, Session 2, Session 3, Session 4) for locomotor activity, Session (three levels: Session 2, Session 3, Session 4) for habituation, Session (two levels: Session 4 and Session 5), and Object Category (two levels: DO and NDO) to compare DO and NDO exploration in the last session of habituation (S4) and in the test session (S5), and Object Category (two levels: DO and NDO) for the re-exploration index.

Experiment 2

Locomotor activity, habituation, DO-NDO exploration in S4 and S5, and re-exploration index were analyzed using a one-way, repeated measures ANOVA with Arrangement (two levels: Same Arrangement, Different Arrangement) as between-groups factor. The repeated measures were Session (four levels: Session 1, Session 2, Session 3, Session 4) for locomotor activity, Session (three levels: Session 2, Session 3, Session 4) for habituation, Session (two levels: Session 4 and Session 5), and Object Category (two levels: DO and NDO) to compare DO and NDO exploration in the last session of habituation (S4) and in the test session (S5), and Object Category (two levels: DO and NDO) for the re-exploration index.

Experiments 3-6

For the experiments in which focal administration was performed, locomotor activity was analyzed using a one-way, repeated measures ANOVA with Treatment (Experiments 3, 5, and 6, four levels: Saline, 37.5 ng, 75 ng, 150 ng; Experiment 4, three levels: Saline, 75 ng, 150 ng) as between-groups factor, and Session (four levels: Session 1, Session 2, Session 3, Session 4) as repeated measures. Habituation was analyzed through a one-way, repeated measures ANOVA with Treatment (Experiments 3, 5, and 6, four levels: Saline, 37.5 ng, 75 ng, 150 ng; Experiment 4, three levels: Saline, 75 ng, 150 ng) as between-groups factor, and Session (three levels: Session 2, Session 3, Session 4) as repeated measures.

Finally, one-way repeated measures ANOVA, with Treatment (Experiments 3, 5, and 6, four levels: Saline, 37.5 ng, 75 ng, 150 ng; Experiment 4, three levels: Saline, 75 ng, 150 ng) as between-groups factor, and Session (two levels: Session 4 and Session 5) and Object Category (two levels: DO and NDO) as repeated measures, was used to analyze absolute values of Object Categories exploration in S4 and in S5. The re-exploration index was analyzed using one-way, repeated measures ANOVA with Treatment (Experiments 3, 5, and 6, four levels: Saline, 37.5 ng, 75 ng, 150 ng; Experiment 4, three levels: Saline, 75 ng, 150 ng) as between-groups factor, and Object Category (two levels: DO and NDO) as repeated measures. Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc analysis was used when appropriate. Group differences were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Histological analysis

At the completion of testing, all mice injected with drugs were sacrificed using an overdose of chloral hydrate, and the brains were removed and stored in 10% formaldehyde. The brains were cut into 60-μm sections with a microtome, and injector placements were determined by examination of serial coronal sections stained with Cresyl Violet.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by research grants from MIUR (PRIN and FIRB funds to A.O. and A.M.), from A.S.I. to A.O. and A.M., and from “La Sapienza” University of Rome to A.O. The authors thank Tullio Riosa and Genesio Ricci for their technical assistance and Agu Pert for his useful suggestions on a previous version of the manuscript.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.learnmem.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/lm.94805.

References

- Adams, S., Kesner, R.P., and Ragozzino, M.E. 2001. Role of the medial and lateral caudate-putamen in mediating an auditory conditional response association. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 76: 106-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertin, S.V., Mulder, A.B., Tabuchi, E., Zugaro, M.B., and Wiener, S.I. 2000. Lesions of the medial shell of the nucleus accumbens impair rats in finding larger rewards, but spare reward-seeking behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 117: 173-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, G.E., Crutcher, M.D., and DeLong, M.R. 1990. Basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: Parallel substrates for motor, oculomotor, “prefrontal” and “limbic” functions. Prog. Brain Res. 85: 119-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amalric, M. and Koob, G.F. 1987. Depletion of dopamine in the caudate nucleus but not in nucleus accumbens impairs reaction-time performance in rats. J. Neurosci. 7: 2129-2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski, M.E., Sadeghian, K., and Kelley, A.E. 2004. Central amygdalar and dorsal striatal NMDA receptor involvement in instrumental learning and spontaneous behavior. Behav. Neurosci. 118: 715-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah, H.E., Frank, M.J., and O'Reilly, R.C. 2004. Hippocampus, cortex, and basal ganglia: Insights from computational models of complementary learning systems. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 82: 253-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breysse, N., Baunez, C., Spooren, W., Gasparini, F., and Amalric, M. 2002. Chronic but not acute treatment with a metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor antagonist reverses the akinetic deficits in a rat model of parkinsonism. J. Neurosci. 22: 5669-5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brog, J.S., Salyapongse, A., Deutch, A.Y., and Zahm, D.S. 1993. The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: Immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J. Comp Neurol. 338: 255-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bures, J., Fenton, A.A., Kaminsky, Y., and Zinyuk, L. 1997. Place cells and place navigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 343-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk, J.A. and Mair, R.G. 2001. Effects of dorsal and ventral striatal lesions on delayed matching trained with retractable levers. Behav. Brain Res. 122: 67-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli, R.M. and West, M.O. 1991. Representation of the body by single neurons in the dorsolateral striatum of the awake, unrestrained rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 309: 231-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, P.J., Davis, H.P., and Volpe, B.T. 1989. Allocentric spatial and tactile memory impairments in rats with dorsal caudate lesions are affected by preoperative behavioral training. Behav. Neurosci. 103: 1242-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools, A.R., Ellenbroek, B., Heeren, D., and Lubbers, L. 1993. Use of high and low responders to novelty in rat studies on the role of the ventral striatum in radial maze performance: Effects of intra-accumbens injections of sulpiride. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 71: 335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin, J.P., Swinkels, W.A., and de Brabander, J.M. 1997. Response learning of rats in a Morris water maze: Involvement of the medical prefrontal cortex. Behav. Brain Res. 85: 47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin, J.P., Moita, M.P., de Brabander, H.M., and Joosten, R.N. 2001. Place and response learning of rats in a Morris water maze: Differential effects of fimbria fornix and medial prefrontal cortex lesions. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 75: 164-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leonibus, E., Mele, A., Oliverio, A., and Pert, A. 2001. Locomotor activity induced by the non-competitive N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist, MK-801: Role of nucleus accumbens efferent pathways. Neuroscience 104: 105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leonibus, E., Costantini, V.J., Castellano, C., Ferretti, V., Oliverio, A., and Mele, A. 2003a. Distinct roles of the different ionotropic glutamate receptors within the nucleus accumbens in passive-avoidance learning and memory in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18: 2365-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leonibus, E., Lafenetre, P., Oliverio, A., and Mele, A. 2003b. Pharmacological evidence of the role of dorsal striatum in spatial memory consolidation in mice. Behav. Neurosci. 117: 685-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.R., Stenger, V.A., and Fiez, J.A. 2004. Motivation-dependent responses in the human caudate nucleus. Cereb. Cortex 14: 1022-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devan, B.D. and White, N.M. 1999. Parallel information processing in the dorsal striatum: Relation to hippocampal function. J. Neurosci. 19: 2789-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devan, B.D., Goad, E.H., and Petri, H.L. 1996. Dissociation of hippocampal and striatal contributions to spatial navigation in the water maze. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 66: 305-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devan, B.D., McDonald, R.J., and White, N.M. 1999. Effects of medial and lateral caudate-putamen lesions on place- and cue-guided behaviors in the water maze: Relation to thigmotaxis. Behav. Brain Res. 100: 5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara, G., Bassareo, V., Fenu, S., De Luca, M.A., Spina, L., Cadoni, C., Acquas, E., Carboni, E., Valentini, V., and Lecca, D. 2004. Dopamine and drug addiction: The nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology 47 Suppl 1: 227-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divac, I., Fonnum, F., and Storm-Mathisen, J. 1977. High affinity uptake of glutamate in terminals of corticostriatal axons. Nature 266: 377-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue, J.P. and Herkenham, M. 1986. Neostriatal projections from individual cortical fields conform to histochemically distinct striatal compartments in the rat. Brain Res. 365: 397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, B.J. and Paxinos, G. 1997. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Gaffan, E.A., Bannerman, D.M., and Healey, A.N. 2003. Learning associations between places and visual cues without learning to navigate: Neither fornix nor entorhinal cortex is required. Hippocampus 13: 445-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal, G., Joel, D., Gusak, O., Feldon, J., and Weiner, I. 1997. The effects of electrolytic lesion to the shell subterritory of the nucleus accumbens on delayed non-matching-to-sample and four-arm baited eight-arm radial-maze tasks. Behav. Neurosci. 111: 92-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, P.J., Sadeghian, K., and Kelley, A.E. 2002. Early consolidation of instrumental learning requires protein synthesis in the nucleus accumbens. Nat. Neurosci. 5: 1327-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.T., Barcia, C., and Navarro, J.M. 2002. Functional anatomy of thalamus and basal ganglia. Childs Nerv. Syst. 18: 386-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock, J.S., Mayes, A.R., Cezayirli, E., Isaac, C.L., Aggleton, J.P., and Roberts, N. 2000. A comparison of egocentric and allocentric spatial memory in a patient with selective hippocampal damage. Neuropsychologia 38: 410-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holscher, C. 2003. Time, space and hippocampal functions. Rev. Neurosci. 14: 253-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, L.F. 2003. The evolution of the cognitive map. Brain Behav. Evol. 62: 128-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel, D. and Weiner, I. 1994. The organization of the basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits: Open interconnected rather than closed segregated. Neuroscience 63: 363-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2000. The connections of the dopaminergic system with the striatum in rats and primates: An analysis with respect to the functional and compartmental organization of the striatum. Neuroscience 96: 451-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, A.E., Smith-Roe, S.L., and Holahan, M.R. 1997. Response-reinforcement learning is dependent on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 12174-12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner, R.P., Farnsworth, G., and DiMattia, B.V. 1989. Double dissociation of egocentric and allocentric space following medial prefrontal and parietal cortex lesions in the rat. Behav. Neurosci. 103: 956-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H., Tsumori, T., Shiroyama, T., Yokota, S., Nakano, K., and Yasui, Y. 2000. Morphological evidence for a vestibulo-thalamo-striatal pathway via the parafascicular nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 872: 208-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie, A.M. and Mizumori, S.J. 1994. Spatial, movement- and reward-sensitive discharge by medial ventral striatum neurons of rats. Brain Res. 638: 157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.M. and Kesner, R.P. 1998. Effects of hippocampal and parietal cortex lesions on memory for egocentric distance and spatial location information in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 112: 480-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair, R.G., Koch, J.K., Newman, J.B., Howard, J.R., and Burk, J.A. 2002. A double dissociation within striatum between serial reaction time and radial maze delayed nonmatching performance in rats. J. Neurosci. 22: 6756-6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Irizarry, C.S. and Kelley, A.E. 1994. Differential behavioral effects following microinjection of an NMDA antagonist into nucleus accumbens subregions. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 116: 65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.J. and White, N.M. 1994. Parallel information processing in the water maze: Evidence for independent memory systems involving dorsal striatum and hippocampus. Behav. Neural Biol. 61: 260-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer, P.L., McGeer, E.G., Scherer, U., and Singh, K. 1977. A glutamatergic corticostriatal path? Brain Res. 128: 369-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori, S.J., Yeshenko, O., Gill, K.M., and Davis, D.M. 2004. Parallel processing across neural systems: Implications for a multiple memory system hypothesis. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 82: 278-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, M. and Bures, J. 1996. Contribution of egocentric spatial memory to place navigation of rats in the Morris water maze. Behav. Brain Res. 78: 121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, A.B., Shibata, R., Trullier, O., and Wiener, S.I. 2005. Spatially selective reward site responses in tonically active neurons of the nucleus accumbens in behaving rats. Exp. Brain Res. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nadel, L. and MacDonald, L. 1980. Hippocampus: Cognitive map or working memory? Behav. Neural Biol. 29: 405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard, M.G. 1999. Glutamate infused posttraining into the hippocampus or caudate-putamen differentially strengthens place and response learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 12881-12886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard, M.G. and Teather, L.A. 1997. Double dissociation of hippocampal and dorsal-striatal memory systems by posttraining intracerebral injections of 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid. Behav. Neurosci. 111: 543-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard, M.G. and White, N.M. 1990. Lesions of the caudate nucleus selectively impair “reference memory” acquisition in the radial maze. Behav. Neural Biol. 53: 39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palencia, C.A. and Ragozzino, M.E. 2004. The influence of NMDA receptors in the dorsomedial striatum on response reversal learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 82: 81-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeger, G.E., Spruijt, B.M., and Cools, A.R. 1994. Spatial localization in the Morris water maze in rats: Acquisition is affected by intra-accumbens injections of the dopaminergic antagonist haloperidol. Behav. Neurosci. 108: 927-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potegal, M. 1969. Role of the caudate nucleus in spatial orientation of rats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 69: 756-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1972. The caudate nucleus egocentric localization system. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 32: 479-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potegal, M., Copack, P., de Jong, J., Krauthamer, G., and Gilman, S. 1971. Vestibular input to the caudate nucleus. Exp. Neurol. 32: 448-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poucet, B. 1989. Object exploration, habituation, and response to a spatial change in rats following septal or medial frontal cortical damage. Behav. Neurosci. 103: 1009-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1993. Spatial cognitive maps in animals: New hypotheses on their structure and neural mechanisms. Psychol. Rev. 100: 163-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino, M.E. and Choi, D. 2004. Dynamic changes in acetylcholine output in the medial striatum during place reversal learning. Learn. Mem. 11: 70-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino, M.E., Jih, J., and Tzavos, A. 2002a. Involvement of the dorsomedial striatum in behavioral flexibility: Role of muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Brain Res. 953: 205-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino, M.E., Ragozzino, K.E., Mizumori, S.J., and Kesner, R.P. 2002b. Role of the dorsomedial striatum in behavioral flexibility for response and visual cue discrimination learning. Behav. Neurosci. 116: 105-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading, P.J., Dunnett, S.B., and Robbins, T.W. 1991. Dissociable roles of the ventral, medial and lateral striatum on the acquisition and performance of a complex visual stimulus-response habit. Behav. Brain Res. 45: 147-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, T.W., Giardini, V., Jones, G.H., Reading, P., and Sahakian, B.J. 1990. Effects of dopamine depletion from the caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens septi on the acquisition and performance of a conditional discrimination task. Behav. Brain Res. 38: 243-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roullet, P., Sargolini, F., Oliverio, A., and Mele, A. 2001. NMDA and AMPA antagonist infusions into the ventral striatum impair different steps of spatial information processing in a nonassociative task in mice. J. Neurosci. 21: 2143-2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargolini, F., Florian, C., Oliverio, A., Mele, A., and Roullet, P. 2003. Differential involvement of NMDA and AMPA receptors within the nucleus accumbens in consolidation of information necessary for place navigation and guidance strategy of mice. Learn. Mem. 10: 285-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save, E. and Moghaddam, M. 1996. Effects of lesions of the associative parietal cortex on the acquisition and use of spatial memory in egocentric and allocentric navigation tasks in the rat. Behav. Neurosci. 110: 74-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save, E., Poucet, B., Foreman, N., and Buhot, M.C. 1992. Exploration and reactions to spatial and nonspatial changes in hooded rats following damage to parietal cortex or hippocampal formation. Behav. Neurosci. 106: 447-456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save, E., Guazzelli, A., and Poucet, B. 2001. Dissociation of the effects of bilateral lesions of the dorsal hippocampus and parietal cortex on path integration in the rat. Behav. Neurosci. 115: 1212-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitzer-Torbert, N. and Redish, A.D. 2004. Neuronal activity in the rodent dorsal striatum in sequential navigation: Separation of spatial and reward responses on the multiple T task. J. Neurophysiol. 91: 2259-2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow, B. and McGaugh, J.L. 1998. Sulpiride infused into the nucleus accumbens posttraining impairs memory of spatial water maze training. Behav. Neurosci. 112: 603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1999. Involvement of the posteroventral caudate-putamen in memory consolidation in the Morris water maze. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 71: 240-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, T., Zetterstrom, T., and Ungerstedt, U. 1986. An in vivo study of dopamine release and metabolism in rat brain regions using intracerebral dialysis. J. Neurochem. 47: 113-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, P.E., Kubie, J.L., and Muller, R.U. 1990. Firing properties of hippocampal neurons in a visually symmetrical environment: Contributions of multiple sensory cues and mnemonic processes. J. Neurosci. 10: 3093-3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear, D.A., Dong, J., Haik-Creguer, K.L., Bazzett, T.J., Albin, R.L., and Dunbar, G.L. 1998. Chronic administration of quinolinic acid in the rat striatum causes spatial learning deficits in a radial arm water maze task. Exp. Neurol. 150: 305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, R., Mulder, A.B., Trullier, O., and Wiener, S.I. 2001. Position sensitivity in phasically discharging nucleus accumbens neurons of rats alternating between tasks requiring complementary types of spatial cues. Neuroscience 108: 391-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]