Abstract

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cancer worldwide, accounting for 2.5 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths in 2022. Early identification of lung cancer through low-dose computed tomography screening is associated with improved outcomes. However, in areas where lung cancer screening (LCS) is currently offered, participation is generally low. LCS is expanding worldwide and is a rapidly evolving field. This comprehensive review aimed to synthesise existing literature on factors associated with LCS participation.

Methods

PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were searched for peer-reviewed articles. Systematic reviews published before 2021 were reviewed and synthesised, while a top-up systematic review of original research published from 2021 onward was conducted. Data on facilitators and barriers of LCS were extracted and analysed using the socio-ecological model and synthesised as an umbrella review of review articles and a systematic review of original research papers. Study quality was assessed by two independent reviewers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and the Joanna Briggs Institute appraisal tools.

Results

Over 110 million participants (N = 110,999,150) were included in seven reviews and 54 recent articles. Facilitators of LCS participation were at the organisational level (promotion of the program, trained staff, integration of LCS with other services, and supportive technology), healthcare provider level (information provision, clear screening recommendations, and positive patient relationships), and individual-level (experience with health services and awareness of cancer). Barriers were at the organisational level (reduced access, limited health insurance and inadequate workforce, communication, information resources, and technology to support the program), healthcare provider level (limited LCS skills and/or knowledge and training, sub-optimal referral processes, and insufficient awareness of health insurance coverage for screening costs ), and individual-level (low awareness of LCS and its cost coverage by health insurance, fear of being diagnosed with cancer, time constraints).

Conclusions

Governments and healthcare services providing LCS programs may maximise facilitators and address barriers to LCS participation by working collaboratively with other stakeholders (e.g., health insurance companies, technology specialists, researchers). A focus on upstream factors (organisation and healthcare provider levels) that drive systemic inequalities in LCS participation may have the most public health benefit.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-23808-8.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Screening, Barriers, Facilitators, Low-dose computed tomography, Systematic review, Umbrella review

Introduction

Lung cancer was the leading cancer worldwide in 2022, accounting for 2.5 million new cases (12.4% of all cancers) and 1.8 million deaths (18.7% of all cancer-related mortalities) [1]. The global burden of lung cancer is projected to have increased by over 85% from 2022, reaching 3.8 million cases and 3.2 million deaths in 2050 [2, 3]. Between 2010 and 2014, age-standardised five-year net survival after lung cancer diagnosis ranged from 10 to 19% in most countries worldwide. Relatively higher survival rates (20 − 33%) and modest improvements in five-year survival rates have been observed in high-income and some middle-income countries compared to low-income countries [4].

Smoking is the leading risk factor for lung cancer, accounting for 63.2% of lung cancer deaths globally in 2021 [5]. Other risks include occupational carcinogens like asbestos and silica [6]. Early detection of lung cancer, including screening, improves survival outcomes. Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) is effective for screening high-risk individuals [7–9]. Unlike population-based cancer screening programs—such as those for breast or cervical cancer [10], which often invite all individuals within a certain age group—LDCT-based lung cancer screening programs (LCSPs) are eligibility-based, targeting individuals at elevated risk, typically due to age and smoking history [7]. This targeted approach reflects the need to balance potential benefits with harms, such as false positives and overdiagnosis, which are more pronounced in low-risk populations. Consequently, LDCT screening programs must implement careful risk-based eligibility criteria and robust infrastructure to ensure informed decision-making and equitable access. As of August 2024, 11 countries, including the USA, Croatia, Czech Republic, Poland, South Korea, Taiwan, China, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, and the United Arab Emirates, have implemented LDCT-based LCSPs at national or regional levels [7]. These countries were identified using the Lung Cancer Policy Network’s interactive map, which highlights them as having implemented a national and/or regional organised LDCT screening Programs [7]. Such Programs are characterised by the systematic invitation of a defined target population, based on eligibility criteria, and are delivered through a standardised protocol that ensures equal access to information, services, and support [7].

However, among countries that have launched the program, participation in lung cancer screening (LCS) is low (generally below half of the eligible population). For example, sub-national LCS participation rates have ranged from 12.8% (2021–2022) [11] to 54.5% (2016–2018) in the USA [12], 40.2% (2013–2019) in China [13], and 40.3% (2021–2022) in Taiwan [14]. Using the framework of the socioecological model of health behaviour, participation in LCS may be understood as being driven by structural/organisational-level factors (e.g., healthcare system and program characteristics), healthcare provider/interpersonal factors (e.g., healthcare service and healthcare professional characteristics) and individual factors (personal characteristics, preferences, and behaviours) [15]. The evidence has suggested this is the case for LCS participation [16, 17]. For instance, the barriers to LCS include low awareness among individuals or healthcare providers, and healthcare systems providing limited access and inadequate resources to support LCSPs. Conversely, there are several factors related to increasing LCS participation, such as health education intervention, training efforts, and technological advancements [16, 17].

Growing evidence has elucidated the barriers and facilitators of LCS participation across settings and time periods [16, 17]. Some of this evidence has been consolidated through systematic reviews [16, 17]. However, with the rapid evolution, expansion, and diversification of LCSPs globally, there remains a critical need for a comprehensive and updated synthesis that captures emerging insights from both systematic reviews and recent primary studies [7]. Previous reviews have rarely applied an established framework to systematically structure the barriers and facilitators to lung cancer screening participation. Socioecological framework enables a comprehensive synthesis of factors operating at multiple levels—individual, healthcare provider, and system—making it particularly useful for understanding the complex and layered influences on screening participation [15]. Therefore, a comprehensive synthesis structured using such a framework—drawing from both existing systematic reviews and recent primary research from countries with national and/or regional LCSPs [7], whose lived experiences offer valuable insights—is needed to guide actionable and contextually informed strategies.

The current study aimed to synthesise the evidence regarding the barriers and facilitators of LCS participation presented in systematic reviews and recent original articles not included in these reviews. As several countries, such as Australia, are on the verge of implementing a LCSP designed to be inclusive of priority populations, including First Nations peoples [18], learning the lessons from existing programs is crucial. This study highlights key barriers and facilitators to inform equitable LCSPs, offering insights to enhance lung cancer prevention and outcomes globally.

Methods

Review protocol and questions

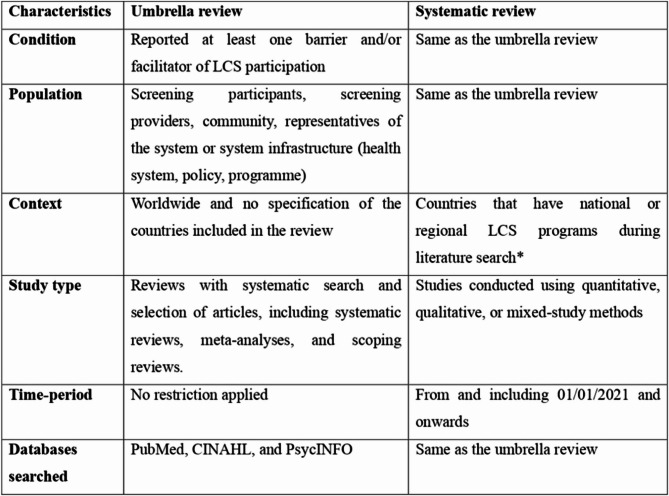

The review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. The review questions were formulated using the CoCoPoP (Condition-Context-Population), with LCS barriers and facilitators (Condition) at individual, provider, organisational, and community levels (Population) worldwide (Context) [20] (Fig. 1). The research questions this review aimed to address was: What are the barriers and facilitators associated with LCS?

Fig. 1.

Databases searched and inclusion criteria for the umbrella and systematic reviews *United States of America, Croatia, Czech Republic, Poland, South Korea, Taiwan, China, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, United Arab Emirates

In this review, ‘participation’ refers to individuals who engaged with LCS, typically following an offer or invitation, reflecting their active involvement in the screening program and encompassing the broader concept of taking part in LCS. This is distinct from broader terms such as ‘access’ (availability and ability to reach services) and ‘utilisation’ (general use of health services), which are components of, but not synonymous with, participation. Additionally, this review uses the term participation in a broad sense, whether related to initial uptake or continued participation throughout the full screening program.

Study design and eligibility

An umbrella review, which synthesises findings from multiple systematic reviews to provide a comprehensive and high-level overview of the evidence on a specific topic [21], was employed as a methodology to integrate existing systematic reviews reporting on barriers and facilitators to LCS [16]. In addition, a systematic review methodology was employed to synthesise evidence from original peer-reviewed journal articles that examined barriers and facilitators to LCS (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Unlike the umbrella review, the top-up systematic review was restricted to studies from countries listed on the Lung Cancer Policy Network’s interactive global map as having implemented a national and/or regional LCSP [7], based on our updated search in August 2024. We believe that insights from these countries are particularly valuable, as they reflect lived experiences with Program implementation. Accordingly, 11 countries—USA, Croatia, Czech Republic, Poland, South Korea, Taiwan, China, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, and the United Arab Emirates [7] —met this criterion and were included in the review.

Table 1.

The characteristics of previous reviews included for umbrella review, sorted by publication year

| Author (year) | Type of review | Databases/site searched | Number of studiesa | Study periodb | Country | Sample size | Quality score (n/11)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavers, 2022 [22] | Mixed methods scoping review | MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, ASSIA, Sociological Abstracts database, reference lists | 21 (Quantitative = 10, Qualitative = 8, Mixed = 3) | 2003–2020 | Australia (n = 1), UK (n = 5), USA (n = 15) | 13,825 individuals from general and high-risk populations | 8 |

| Huang, 2022 [23] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database, and WanFang Database, PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library | 69 quantitative | 2001–2018 | China (n = 58), Japan (n = 7), Korea (n = 4) | 368,216 Asian individuals from the general, and high-risk population groups | 11 |

| Kunitomo, 2022 [24] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CENTRAL and CINAHL | 9 quantitative | 2018–2020 | USA | 2,554,353 patients either referred to or eligible for LCS | 11 |

| Lin, 2022 [16] | Mixed methods systematic review | PubMed, Ovid, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database, Google Scholar, reference list searches | 36 (Quantitative = 25, Qualitative = 11) | 2006–2020 | China (n = 3), France (n = 1), Korea (n = 3), Pakistan (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), UK (n = 1), USA (n = 25), Australia (n = 1) | 1,575 HCPs, 45,364 individuals at risk of lung cancer (40–81 years old) | 10 |

| Sedani, 2022 [25] | Systematic review | MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PubMed, and Web of Science | 37 (Qualitative = 11, Quantitative = 21, Mixed = 5) | 2013–2019 | USA | 329 sites (system-level, n = 5), 2,229 HCPs (n = 19), and 2,023 participants (n = 13) | 9 |

| Sosa, 2021 [26] | Systematic review | PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL | 21 qualitative | 2015–2020 | USA | Studies examining socioeconomic and race based LCS outcomes, focusing on USA populations aged 45–80 years old who were current or former smokers | 10 |

| Fang, 2019 [27] | Integrative review | PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar | 10 (Quantitative = 4, Qualitative = 6) | 2013–2017 | USA (n = 10) | 1,194 current or former smokers | 7 |

HCP Healthcare provider, LCS lung cancer screening, UK United Kingdom, USA United States of America

aMixed study design was for articles that included both quantitative and qualitative study designs

bThe study period in years refers to the earliest and latest dates of publication of the original articles included in the review

cQuality appraisal score out of the 11 Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) criteria, with the higher score indicating a better quality review. For instance, 10 means it fulfilled 10 out of 11 criteria; the full details can be found in the supplementary material (Table S3A)

Table 2.

The characteristics of recent quantitative articles, sorted by publication year and author name

| ID | Country | Study period | Study design | Population | Sample size | LCS rate (%) | Quality score (n/5)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ellis, 2024 [28] | USA | 2013–2020 | Cross-sectional data collection during LDCT screening visit | Individuals aged 50 years and above and living in Highlands Oncology’s catchment area | 5,398 | Not reported | 5 |

| Nourmohammadi, 2024 [29] | USA | 2022 | Respondents for the Health Information National Trends Survey, which conducted either on paper or online options | Both LCS-ineligible and LCS-eligible individuals according to USPSTF | 1,559 | Not reported | 5 |

| Pan, 2024 [30] | China | 2022 | A cross-sectional survey included participants selected using stratified proportional sampling | Individuals aged 40–74 years and living for more than one year in Sichuan Province | 2,529 | 34.7 | 5 |

| Yi, 2024 [31] | USA | 2017–2022 | Retrospective analysis of EHR data for LCS | LCS eligible individuals who were able to calculate travel time from their home to the LCS facility | 2,287 | 68% among those with initial LDCT order | 5 |

| Zhang, 2024 [32] | China | 2022–2023 | A cross-sectional survey included participants selected using a convenience sampling method | Patients enrolled for the outpatient’s department at high risk for lung cancer at Lanzhou University Second Hospital | 577 | 24.6 | 3 |

| Barta, 2023 [33] | USA | 2014–2021 | Retrospective analysis of EHR | Individuals screened for LCS and live in Philadelphia | 11,222 | Not applicable | 5 |

| Carter-Bawa, 2023 [34] | USA | 2019–2020 | Cross-sectional study using self-reported data via Research Electronic Data Capture | Primary care pulmonary clinicians (nurses, physicians, and physician assistants) | 545 | Not applicable | 4 |

| Copeland, 2023 [35] | USA | 2019–2022 | Cross-sectional study using telephone interview data | Persons eligible for LCS according to 2013 USPSTF guidelines (55–80 years, 30 pack-year smoking history, current smoker or quit smoking within the last 15 years) | 243 | 27 | 5 |

| Doan, 2023 [36] | USA | 2017–2022 | Retrospective analysis of population-based administrative data | Persons claimed Medicare beneficiaries | 3,700,000 | 1.14 (2017–2019) | 5 |

| Gudina, 2023 [37] | USA | 2018–2020 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Persons aged 55–80 years and have > 30 pack-year smoking history (current smoker or quit smoking < 15 years) | 11,297 | 15.94 | 5 |

| Guo, 2023 [13] | China | 2013–2019 | Cross-sectional study using the population-based LCS program database | Persons aged 40–74 years with a family history of cancer and recommended for LDCT according to the Cancer Screening Program in Urban China risk score system | 55,428 | 40.16 | 5 |

| Hughes, 2023 [38] | USA | 2017 | Retrospective analysis of administrative database for medical claims | Persons eligible for LCS enrolment | 1,077,142 | 3.4 | 5 |

| Li, 2023[39] | USA | 2013–2020 | Retrospective analysis of EHR data | Individuals aged 55–80 years who had at least a 30 pack-year smoking history and smoking currently or quit in the past 15 years | 12,469 | Ranged 11.8% in 2016 to 29.3% in 2020 | 3 |

| Melikam, 2023 [40] | USA | 2019 | Retrospective analysis of EHR data and LCS sites address | Individuals eligible for LCS (aged 55–77 years, smoking currently or previously within 15 years, and had ≥ 30 pack-year smoking history) | 6930 | 20.7 | 5 |

| Navuluri, 2023 [41] | USA | 2013–2021 | Cross-sectional study | LCS-eligible veterans who were referred for screening at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System | 4,562 | 37.1% completion rate among those referred for screening | 5 |

| Peña, 2023 [42] | USA | 2021 | Quantitative analysis to measure the distance to LCS sites | All American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes who listed in the Federal Register as federally recognized and eligible for services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. | 554 | Not applicable | 4 |

| Simkin, 2023 [43] | Canada | 2022 | Spatial analysis to assess access to 36 screening sites | All current or former smokers aged 55 to 74, with ≤ 20 years of smoking history and have a six-year lung cancer risk of > 1.5% using the PLCOm2012 risk prediction tool. | 12,688 | Not reported | 5 |

| Steinberg, 2023 [44] | USA | 2017–2019 | Retrospective analysis of HER data | LCS eligible individuals | 24,356 | Not reported | 3 |

| Stahl, 2023 [45] | USA | 2019–2021 | Retrospective analysis of the administrative database from LCS programs accredited by the ACR | Participants who took LCS by LDCT or chest Computed Tomography | 2,075 (1218 pre-COVID-19 lockdown and 857 during lockdown) | 37.4 pre-COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and 16.5 during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown | 4 |

| Wu, 2023 [14] | Taiwan | 2021–2022 | Cross-sectional study using the primary data collected in tertiary referral medical centre | Persons aged 50–80 years and had health checkups in LDCT screening hospitals or were admitted for diagnostic lung procedures (surgical or non-surgical) for the first time | 518 (334 health checkup groups, 184 diagnostic lung procedure groups) | 40.3 (25.1 among health checkup group and 67.9 among diagnostic lung procedure group) | 3 |

| Leng, 2022 [46] | USA | 2016–2018 | Cross-sectional study using health facility-based survey | Primary healthcare providers | 83 | Not applicable | 3 |

| Lewis, 2022 [47] | USA | 2011–2018 | Retrospective analysis of health facility-based data from Veterans Affairs Medical Centres | Veterans screened at Veterans Affairs Medical Centres | 27,746 veterans screened in 8 Veterans Affairs Medical Centres | Not applicable | 5 |

| Li, 2022 [48] | China | 2020 | Cross-sectional study using population-based survey | Community residents, healthcare workers and medical institutions | 35,692 residents, 6,350 healthcare workers and 81 medical institutions | Not reported | 5 |

| Little, 2022 [49] | USA | 2018 | Website review of informational sites from Google internet search | Unique websites providing information about LCS | 257 | Not applicable | Can’t tell |

| Liu, 2022 [11] | USA | 2021–2022 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Persons who participated in the BRFSS survey | 96,078 | 12.8 | 5 |

| Lopez, 2022 [12] | USA | 2016–2018 | Retrospective analysis of hospital-based (academic hospital) data from EHR | People living with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) | 22 | 54.5 among those referred for LCS | 3 |

| Núñez, 2022 [50] | USA | 2013–2021 | Retrospective analysis of population-based data from EHR | Veterans eligible for LCS and registered by physicians for LCS reminders | 43,257 | 68 among those offered LCS | 5 |

| Oshiro, 2022 [51] | USA | 2015–2019 | Retrospective analysis of the population-based data from EHR | Persons aged 55–79 years who have 30 packs-year smoking history (current smoker or quit smoking within the last 15 years), have not been diagnosed with cancer, or survived five years and above after diagnosis/treatment of any lung cancer | 1,030 | Not reported | 5 |

| Rustagi, 2022 [52] | USA | 2017–2020 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Persons aged 50–79 years with 30 + packs-year smoking (current smokers, or quitting smoking within the last 15 years) | 1,433 | 17 | 4 |

| Sahar, 2022 [53] | USA | 2013–2018 (census data) & 2020 (LCS facility data) | Geospatial analysis of LCS coverage by area | Persons aged 50–80 years who were eligible for LCS | 100,133,060 | Not reported | 5 |

| Sun, 2022 [54] | USA | 2017–2019 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Persons at high risk for lung cancer | 11,163 | Baseline rate: 11.1 for men and 18.2% for women | 4 |

| Zgodic, 2022 [55] | USA | 2018–2019 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Persons eligible for LCS according to the 2013 USPSTF guidelines, aged 55–80 years and with a 30 + pack-year smoking history (current smokers or quit within the past 15 years) | 7,825 | 17.54 | 5 |

| Advani, 2021 [56] | USA | 2017–2019 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Participants aged 55–80 years who had a 30-pack-year smoking history and currently smoked or had quit smoking within the past 15 years | 11,214 | 16.3 | 5 |

| Alban, 2021 [57] | USA | 2010–2017 | Website review of informational videos from YouTube | Unique videos published in the English language | 123 | Not applicable | Can’t tell |

| Boudreau, 2021 [58] | USA | 2013–2019 | Retrospective analysis using population-based data from linked LCS national administrative data | Veterans aged 55–80 years | 2,666,766 | 2.7 | 5 |

| Gerber, 2021 [59] | USA | 2017–2019 | Retrospective analysis of Hospital-based data from EHR | Healthcare providers delivering LCS programs | 194 adult primary care physicians | Median LDCT order by 183 medical providers was 4 | 5 |

| Gupta, 2021 [60] | USA | 2016–2019 | Quasi-experimental study using the administrative data from ACR Lung Cancer Registry | States that adopted Medicaid and states that did not adopt Medicaid | 48(31 = Medicaid adopted states, 17 = Medicaid not adopted states) | 57.6 among Medicaid-adopted states and 50.3 among Medicaid non-adopted states | 5 |

| Hasson, 2021 [61] | USA | 2013–2017 | Retrospective analysis of health rankings reports at the County level | Healthcare providers delivering LCS programs | LCS programs in New Hampshire and Vermont | Not applicable | 5 |

| Hochheimer, 2021 [62] | USA | 2012–2016 | Randomised controlled trial using data from EHR in 45 primary care health services | Patients aged 55–80 years who were smokers at the time of data collection | 14,218 patients | LCS rate increased by 2.8–5.6 after screening guidelines changed | 5 |

| Li, 2021 [63] | USA | 2015–2017 | Cross-sectional study using health facility-based chart reviews | LCS-eligible patients according to the 2013 USPSTF guidelines | 1,355 | 29.8% | 5 |

| Marcondes, 2021 [64] | USA | 2019–2020 | Interrupted time series using health facility-based data from EHR | Persons aged 55–80 years without a LDCT in the past year who currently smoke or quit smoking within the prior 15 years | 10,697 | Not reported | 5 |

| Nishi, 2021 [65] | USA | 2018 | Cross-sectional study using health facility-based data from primary surveys | Persons who underwent LCS in the past 12 months before the survey | 266 | Not applicable | 3 |

| Poghosyan, 2021 [66] | USA | 2017 | Cross-sectional study using population-based data from BRFSS | Persons aged 55–74 years with a lifetime smoke of ≥ 100 cigarettes or current smokers | 2,640 | 16.0 | 5 |

| Sahar, 2021 [67] | USA | 2012–2016 | Geospatial analysis using linked data from geocoded distance and BRFSS | Persons aged 55–79 years | 3,592 geocoded unique locations | Not applicable | 4 |

ACR American College of Radiology, BRFSS Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, EHR electronic health records, LDC Low-Dose Computed Tomography, LCS lung cancer screening, USA United States of America, USPSTF the United States Preventive Services Task Force

aQuality appraisal score out of the 5 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) criteria, with the higher score indicating a better quality article. For instance, 4 means it fulfilled 4 out of 5 criteria; the full details can be found in the supplementary material (Table S3B)

Table 3.

The characteristics of recent qualitative articles, sorted by publication year and author name

| ID | Country | Study period | Study design | Population | Sample size | Quality score (n/5)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, 2023 [68] | USA | 2019–2020 | Thematic analysis using interview data | American Indian and Alaska Native patients aged 45-79 years with current or previous smoking history and healthcare providers working in Minnesota Urban Indigenous Community clinics | Nine healthcare providers for key informant interviews and 15 patients in four focus groups. | 5 |

| Gomes, 2023 [69] | USA | 2020 | Thematic analysis using interview data | Professionals working in rural primary healthcare (clinicians or administrative staff) and patients eligible for LCS (aged 50–80 years and current or previous cigarette smokers) | 9 clinicians, 12 clinical staff, 5 administrators and 12 patients | 5 |

| Abubaker-Sharif, 2022 [70] | USA | Not reported | Direct content analysis using key informant interview data | Primary care physicians working in large medical settings that provide LCS | 16 (7 community and family medicine professional and 9 internal medicine) | 5 |

| Leng, 2022 [71] | USA | Not reported | Inductive analysis using interview data | Chinese-serving healthcare providers | 13 | 5 |

| Leng, 2022 [72] | USA | 2018 | Inductive analysis from grounded theory using interview data | Chinese immigrant men aged 21–80 years who drive livery and are current smokers or quit smoking <15 years. | 39 in five focus group discussions | 5 |

| Martinez, 2022 [73] | USA | 2019-2020 | Grounded theory analysis using interview, EHR, and administrative data | Patients and healthcare providers providing LCS | 10 providers and 30 patients | 5 |

| Allen, 2021 [74] | USA | 2017-2018 | Implementation Research analysis usingkey informant interview data | Healthcare providers, patient navigators, regional staff, and project managers working in federally-qualified health centres | 46 interviews | 5 |

| Sayani, 2021 [75] | Canada | 2019-2020 | Thematic analysis using interview data | Persons aged 55-74 years who smoked daily over the past 20 years | 18 (8 screened and 10 declined screening) | 5 |

| Wang, 2021 [76] | USA | 2018-2019 | Exploratory and content analysis of hospital-based data from EHR | Patients who received LCS orders after alerts via the clinical decision support system | 2,248 | 5 |

| Watson, 2021 [77] | USA | 2016-2018 | Case study of LCS implementation using key informant interview and document review data | Persons aged 55-77 years with a smoking history of 30-pack-year (current smokers or quit over the last 15 years) | 320 (263 in site A and 57 in site B)b | Can’t tell |

HER Electronic health records, LCS Lung cancer screening, USA United States of America, USPSTF The United States Preventive Services Task Force

aQuality appraisal score out of the 5 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) criteria, with the higher score indicating a better-quality article. For instance, 4 means it fulfilled 4 out of 5 criteria; the full details can be found in the supplementary material (Table S3B)

bSite A was in a rural area within a state that had Medicaid expansion. Site B was in a large, urban area in a state without Medicaid expansion

The study scope was limited to peer-reviewed articles published in English. For the umbrella review, we included reviews examining barriers and/or facilitators to lung cancer screening participation. For the top-up systematic review, we included primary qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies that reported on factors influencing LCS participation. Books, protocols, commentaries, editorial letters, reports, conference abstracts, and mass-media publications were excluded.

Article search and screening

PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases were systematically searched on June 12, 2023, and again on August 1, 2024, to capture recent relevant publications (Tables 1, 2 and 3). As the umbrella review included reviews of original articles published up to and including December 31, 2020, the systematic review included articles published between January 1, 2021, and August 1, 2024.

The search terms were developed by reviewing relevant publications and through discussion with the research team [16, 26, 78–88]. Titles and abstracts were searched for the following key terms: (“lung cancer screening” OR “low dose computed tomography”) OR ((“lung neoplasms”) AND (“early detection of cancer” OR “screening”)) AND “systematic review” OR “meta-analysis” for the umbrella review and countries that had national or regional LCSPs at the time (“United States” OR “Croatia” OR “Czech Republic” OR “Poland” OR “Republic of Korea” OR “Taiwan” OR “China” OR “Canada” OR “United Arab Emirates”) [7]. Consistent search terms were used across the databases. An example search using the PubMed database is provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary 1 − Table S1).

Articles were imported into the Endnote software for duplicate removal before being exported to Rayyan software for title, abstract, and full-text screening by two independent reviewers using pre-defined eligibility criteria [89]. Any disagreements during screening were resolved by discussion and/or adjudication by a third author when necessary. The data extracted comprised the article’s characteristics (e.g., publication, study period, study design, and sample size), study setting (e.g., source population or country of the study), and key findings (e.g., barriers and facilitators of LCS).

Data synthesis and quality appraisal

The barriers and facilitators of LCS were summarised using the socioecological model, which has been widely utilised in health research, including LCS, and considers the importance of individual or beyond-individual characteristics. These include interpersonal factors, i.e. healthcare providers or other connections with family, relatives, or friends, and organisational-level factors, i.e., hospitals, screening programs, and cultural context of the community or residential area [15, 16, 27].

The Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tool for umbrella review was used to appraise the articles included in the umbrella review according to 11 criteria, including the review question, eligibility criteria, search strategy, databases, publication quality, bias assessment, and data-driven conclusion [90]. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), with options for appraising both qualitative and quantitative articles, was used to evaluate and appraise the original articles included in the systematic review [91]. The tool includes two eligibility assessment checklists (research question clarity and appropriateness of the collected data for addressing the question) and five criteria each for quantitative sampling strategy appropriateness, sample representativeness, nonresponse bias, measurement, and analysis methodology appropriateness) and qualitative the study design appropriateness’, data collection adequacy, analysis, data-driven finding, and result interpretation) research [91].

To assess the extent of overlap among reviews included in the umbrella review, citation matrices were constructed with individual primary studies represented in rows and systematic reviews in columns. The degree of overlap was quantified using the corrected covered area (CCA) [92, 93].

|

In this approach, N denotes the total number of publications, including duplicates, r represents the count of unique studies (rows), and c refers to the number of reviews (columns).

The CCA scores were categorised to interpret the degree of overlap: a score below 5 indicated slight overlap, scores between 6 and 10 represented moderate overlap, scores ranging from 11 to 15 signified a high level of overlap, and scores exceeding 15 reflected a very high degree of overlap [92, 93].

Results

Study characteristics and LCS participation

Over 110 million participants (110,999,150) were included across seven reviews (n = 2,988,779) (Table 1, Fig. 2A) and 54 recent and original research articles (n = 108,010,371) (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 2B). Over half (n = 4) of the review articles included 20–40 original studies, published between 2001 and 2020. Over half (58%) of the original articles in the six reviews and nearly nine-tenths (87%) in the top-up systemic review were conducted in the USA (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection: A previous reviews for the umbrella review B recent articles for systematic review LCS = Lung Cancer Screening

The corrected covered area was calculated to be 3.23%, indicating minimal overlap among individual primary studies across the reviews included in the umbrella review.

Facilitators of LCS

Facilitators at the organizational, healthcare provider, or interpersonal, and individual levels enhance LCS participation. At the organisational-level (promotion of the program, trained staff, integration of LCS with other services, and supportive technology), healthcare provider level (information provision, clear screening recommendations, interest in training, and positive patient relationships), and individual level (experience with health services and awareness of cancer). The section below presents the facilitators of LCS (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

The barriers and facilitators of lung cancer screening: A Facilitators B Barriers. EHR = Electronic Health Records, HCP = Healthcare Provider, LCS = Lung cancer screening

Organisational or policy-level facilitators

System readiness and embedding technology

System readiness facilitates LCS participation. This involves resource allocation, dedicated staff, established screening workflows, decision aids, streamlined referral processes, template for screening referral and documentation, concise guideline summaries in a suitable format, insurance codes, leadership support, staff engagement, and nursing navigators involvement [16, 23, 25, 50, 70, 74, 77]. Screening rates were higher in programs providing transportation to LDCT locations or covering transportation costs [25], one study noted a 43% increase in intention to participate when individuals had convenient access to the cancer screening unit [16]. Facilities with breathing centres (specialised units for managing respiratory health and conditions) and those meeting high standards, like the US National Lung Cancer Screening Test standard saw better participation rates (OR 1.48, 95% CI: 0.92–2.38) [23]. Integrating LCS with routine visits, such as wellness or acute care visits, improved participation rates [73]. Health systems with supportive and knowledgeable leaders who actively engage, and train staff also reported higher screening participation [16, 25, 74] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

According to findings from a previous review [16] and recent articles [44, 46, 62, 69, 74], the use of technology-assisted LCS ─ such as Electronic Health records (EHRs), notification systems, and reminders ─ has been shown to substantially enhance LCS rates [46, 62]. 65% of US healthcare providers indicated that EHRs provided hints about screening eligibility [74] and positively influenced their likelihood to refer patients for LCS [46]. Specifically, services that used EHRs prompts compared to those without were more likely to identify eligible patients for LCS (adjusted odds ratio (aOR); 1.59, 95% CI: 1.38–1.82), refer to LDCT (aOR 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.07), and complete LDCT criteria documentation (aOR 1.19, 95% CI: 1.15–1.23) [44] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Health education and advertisement

Individuals who were referred for LCS or had it, recommended, or endorsed by healthcare providers, family, or other organisations, such as professional associations, increased screening participation [22, 25]. US community health workers played a key role in raising awareness and referring individuals to LCS [72].

Advertising to promote and raise awareness of LCS generally and LCS programs specifically also increased participation [28, 35, 70, 72]. For example, 15.5% of individuals in the USA cited mail advertisements for attending LCS [35]. Advertising LCS programs, which inherently includes raising awareness about LDCT, combined with providing free screening in the USA increased screening volume from an average of 4.6 patients per month during the fee-based period (10 months) to 66.0 patients per month during the free period using targeted advertisements (billboards, TV and radio, interviews, direct mailings, newspapers) and primary care outreach (10 months) [28]. Healthcare providers highlighted the value of promoting LCS through social media (presenting case studies in the news), EHRs, patient waiting rooms, or community settings [70].

Cultural acceptance, trust, and discussion

Cultural acceptance of LCS and strong family values were identified as key facilitators of LCS participation [16], alongside positive experiences with staff and appointments, and trust in the healthcare providers [16, 22]. US participants highlighted the importance of cultural safety in LCS, including supporting family decision-making by communicating with and providing information to eligible individuals that enable family discussions, for example, by sending a letter (“You send a letter, his family also reads it.his family members will encourage him to go”) [72]. Most participants expressed a preference for healthcare providers who share a similar cultural background and speak their language. For providers who do not, they emphasize the need for interpretation services, particularly when dialects differ [72].

Healthcare provider-patient or interpersonal-level facilitators

Positive communication and recommendations

Higher LCS participation was noted among individuals who received LCS recommendations or information from healthcare providers or community members [16, 29, 32, 35, 50, 55, 75]. For example, a review documented that individuals recommended for screening by healthcare providers were 2.6 times more likely to participate [16]. Common motivators for LCS participation in the USA included recommendations from Community Health Advisors (68.9%), friends (27.6%), family (15.5%), doctors (3.4%), or others (5.2%) [35]. In Canada, supportive, collaborative relationships with healthcare providers were linked to higher LCS participation [75]. In China, 62.4% of individuals reported being counselled for screening by their doctors [32] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Knowledge, perception, and experience

Healthcare providers were more likely to refer and screen patients if they trusted the scientific evidence supporting LCS guidelines and believed LCS to be cost-effective and beneficial [25]. LCS implementation was greater among providers who felt confident discussing its pros and cons with patients [16, 25], had adequate time for counselling the screening process and outcome [25] and could utilize EHRs for screening and referral [25] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Individual-level facilitators

Awareness and trust in LCS

Awareness of LCS and insurance cost coverage and knowledge of the benefits of screening were associated with higher participation in a review conducted in the USA [25]. Those who perceived the benefits of LCS to outweigh associated risks, trusted the accuracy of LDCT, and viewed LDCT as convenient, were more likely to participate [22, 25]. For example, in the USA, individuals perceiving a benefit from LCS were twice as likely to participate (P = 0.01). Most participants in this study felt the benefits outweighed the risks, with some patients (< 50%) raising concerns about screening effectiveness [22].

Chronic disease, cancer, and healthcare system experience

Experience with chronic disease and cancer and regular interactions with the healthcare system was associated with increased participation in LCS programs, potentially due to higher levels of awareness of the benefits of screening, the procedures involved, and clinical pathways. Individuals with existing chronic medical conditions (referred to as comorbidity) had up to a twofold LCS participation rate. For example, the LCS rate was higher among eligible individuals in the USA with ≥ 3 comorbidities compared to those without comorbidities (aOR 95% CI: 2.38 (1.48–3.83)) [52]. Additionally, eligible Americans who rated their general health as poor (aOR: 1.68 (1.35–2.10)) or fair (aOR: 1.35 (1.12–1.62)) had higher participation rates than those who rated their health as excellent, very good, or good [55] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2B, Fig. 3A).

Individuals with a close relative or friend diagnosed with cancer have better LCS participation [13, 16, 25, 35]. In China, LCS rates increased with the number of family members with cancer: one (aOR 95% CI: 1.88 (1.80–1.96)), two (2.65 (2.51–2.79)), three (2.83 (2.64–3.04)), and four or more (3.46 (3.15–3.79)) [13]. In the USA, 19% of individuals reported that knowing someone with cancer influenced their decision to participate in LCS [35].

LCS participation rates are higher in individuals who receive regular health check-ups or have visited health facilities [16, 50, 55, 62, 75]. Those who routinely underwent health check-ups were 2.9 times more likely to participate in LCS [16]. Each additional health facility visit was associated with a 10% increase in LCS participation (aOR; 95%CI: 1.10 (1.07–1.13)) [62].

Prioritising health and perceived susceptibility

Individuals were motivated to undergo screening by wanting to seek reassurance of good lung health, maintain a health-conscious mindset, monitor their health, and reduce worries about lung cancer. Some wanted to ‘see the state of their lungs’ to evaluate lifestyle changes or consider smoking cessation [16, 22]. Moreover, in the USA, LCS participation was 63% higher among individuals who perceived themselves as susceptible to lung cancer than those who did not [16].

Barriers to lung cancer screening

LCS participation is influenced by factors at the organizational, healthcare provider or interpersonal and individual levels. At the organisational-level (reduced service access, limited health insurance and inadequate workforce, communication, information resources, and technology to support the program), healthcare provider level (limited LCS knowledge and training, sub-optimal referral processes, limited knowledge about the cost coverage by health insurance, and time limitations), and individual level (low awareness about LCS and its cost coverage by health insurance, fear of being diagnosed with cancer or the screening process, doubts about effectiveness, low interest, and time constraints). See supplementary 1 − Table S2A and Fig. 3B for further details.

Organisational or policy-level barriers

Infrastructure and access

Previous reviews [16, 27] and recent articles [68, 71–73, 77] highlight the limited infrastructure for LCS. Key challenges include low system readiness, insufficient health information technology (including a lack of EHRs or restricted ability to use electronic records to determine LCS eligibility (i.e., smoking pack-years), and send communications including invitations, reminders, and results notifications), decision aids, training materials, and limited scientific evidence supporting the LCSPs [16, 25, 71, 73, 77]. High staff turnover, shortage of multidisciplinary teams or trained personnel, absence of dedicated screening counsellors, and limited leadership support were also reported as barriers to access and therefore participation in LCS programs [16, 25, 74, 77]. Barriers in the USA included insufficient resources, such as patient educational materials, patient transportation, physical space, and supportive care throughout screening [68, 72]. Additionally, aspects of LDCT, such as the large, cylindrical shape of the machine and the perceived invasiveness of the procedure, were thought to induce anxiety or fear of tight or enclosed spaces (claustrophobia) representing test-related barriers that influence LCS participation [16, 46, 68, 69, 71, 73] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Geographic access also impacts LCS participation, with lower screening rates in rural compared with urban areas, as reported in both reviews [16, 22, 27] and recent articles [30, 31, 33, 38, 42, 43, 48, 50, 53, 55, 61, 62, 69]. In the USA, rural (aOR; 0.12, 95% CI: 0.04–0.37) and sub-urban (aOR 0.56, 95% CI: 0.31–0.99) facilities had lower LCS rates than urban centres [62]. In China, top-ranked facilities were more likely to offer LCS, reflecting disparities with respect to infrastructure and workforce [48].

Financial difficulty and health insurance

The reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [11, 37, 38, 50, 52, 55, 62, 63, 66, 68, 71, 74, 75] identified limited health insurance and financial barriers to LCS. Challenges include health insurance policies that do not cover screening costs, delayed reimbursements, low payments, lack of coverage for follow-up screening, and complex authorisation processes such as lack of automatic approval. Claim errors often delay healthcare provider reimbursement [25, 74]. In a previous review, 25 − 33% of individuals cited lack of insurance as a main reason for not screening [27]. In the USA, LCS rates were 0.43 times lower among uninsured compared to insured individuals (aOR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.26–0.70) [55], while uninsured Chinese individuals were 0.23 times lower compared to those insured (aOR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10–0.53)) [11].

Other financial barriers to LCS participation include difficulty covering medical expenses, concerns about additional (non-medical) costs (e.g., transportation), and potential treatment costs if diagnosed with cancer. LCS rates were 0.52 times lower among individuals who were unable to afford care in the past year than those without such financial challenges (aOR 0.52, 95% CI: 0.39–0.70) [55].

Inadequate communication and mistrust

The reviews [16, 25] and recent articles [49, 62] identified low LCS participation rates in individuals facing communication and language barriers that made navigating the screening procedure difficult. A USA study found that only 3% (7/257) of LCS websites provided information in languages other than English [49]. Medical institutions and news sources providing LCS information often focused on screening benefits (85%) and lacked key details, such as eligibility criteria (38%), associated risks (36%), and screening process information (27%) [57].

Mistrust in the health system also contributes to low LCS participation, as identified in previous reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [68, 75]. Mistrust generally refers to a lack of confidence that develops over time due to systemic issues or a perceived lack of cultural safety, whereas distrust implies a more active suspicion or belief that the health system may cause harm. Both sentiments can lead individuals to avoid preventive services such as LDCT screening [94]. Distrust—stemming from negative experiences or loss was particularly impactful among minority populations [16, 22, 27]. In Canada, individuals cited the judgment or insensitivity of healthcare providers as a barrier to LCS [75].

Regulation and policy

LCS rates were significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with declines observed during lockdowns [45] or seasonal infection peaks [36, 64]. In the USA, the LCS rate dropped by 29.6% during the lockdown, from 37.4% (pre-pandemic) to 16.5% (pandemic, P < 0.001) [45]. Post-March 2020, LCS rates fell by 0.54 times compared with pre-pandemic levels (Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) 0.54, 95% CI: 0.33–0.89) [64] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Regulatory barriers to LCS include requirements for separate appointments for screening decisions, mandatory paperwork, restrictions allowing only pulmonologists to order screenings, and insurance prerequisites like prior authorisation [16, 25]. The lack of reassurance about screening outcomes and the absence of immediate intervention guarantees for lung cancer or incidental findings further reduce participation [25].

Multiple and evolving LCS guidelines and eligibility criteria complicate the screening process. Screening reporting metrics were also often inconsistent [69, 70]. Over half (52%) of US primary care providers reported the “vague” screening criteria challenged their practice [46], such as conflicting age limits from USPSTF and Medicare (88 vs. 77 years, respectively) [46]. Calculating smoking pack years was also seen as complex [46].

Previous reviews [14, 23] and recent articles [15, 23, 29, 69, 72] noted a lack of organisational culture to make LCS routine, with some patients not recalling being offered to screen [16, 69]. A USA review found that more than half of high-risk smokers were not recommended for LCS [27].

Community belief and stigma

Community-level social, cultural, and religious beliefs (e.g., viewing lung cancer as untreatable or believing that screening cannot help or “provide a new pair of lungs”), along with low collective acceptance of LCS and widespread lung cancer stigma (e.g., blame, social isolation, shame, mistreatment) are reported barriers to participation [16, 22, 25, 27, 69, 71] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Healthcare provider-patient or interpersonal-level barriers

Awareness, perception, and experience

Healthcare providers’ limited awareness and experience of LCS have been documented in reviews [16, 25, 27] and recent articles [34, 41, 46, 48, 68, 71, 73, 74]. Some providers doubted the LCS evidence base, including the benefits, and were concerned about high false-positive rates, unnecessary radiation exposure, and psychological stress [34, 73]. Many providers lacked awareness of lung cancer risk factors and screening protocols [27, 34, 68], including how to identify and refer eligible patients, the location of LDCT facilities, and screening guidelines [16, 27, 34]. Limited familiarity with patient needs, documentation, referral process technology, and handling positive screening cases was also noted [16, 25, 34, 69, 73]. Some were uncertain about responsibility for patient follow-ups, abnormal results, and coordinating treatment if screened individuals were diagnosed with lung cancer [70].

Providers also had limited knowledge regarding the funding for LCS, including how screening costs are covered by insurance, the proper coding and billing of LCS appointments, and the specifics of screening guidelines [16, 25, 46, 74]. In the USA, health professionals have limited knowledge about LCSP guidelines, with 26% of primary healthcare providers unaware of LDCT, and inconsistencies with the United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines led to a discordant screening rate of 1.9%, with physicians often referring ineligible patients with a family history of lung cancer [46, 60, 76]. Screening practices vary widely, with some providers never recommending or referring patients for LCS, while others routinely offer it [27, 69].

Time constraints and limited motivation

Previous reviews [25, 27] and recent articles [68, 69, 72, 74] highlight the time constraints on healthcare providers when discussing the screening process, suggesting screening programs do not allocate enough time to parallels that are required to identify and refer eligible individuals [27, 68, 69, 74]. Healthcare providers reported limited time for tasks such as identifying, referring, screening, notifying results, counselling, and managing competing priorities [25, 27]. Difficulties coordinating the screening process, lack of market-competitive reimbursement from the government and/or organization, and income loss due to patient no-shows lead to low motivation to offer LCS [69]. Scheduling appointments is further complicated by the need for frequent, long-term patient contact [16, 25, 71] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Individual-level barriers

Awareness, belief, and psychological factors

Previous reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [29, 32, 48, 69, 70, 72, 73] reported that low awareness about lung cancer and screening remains a significant barrier. Many individuals lack knowledge about lung cancer, its risk factors, and the specifics of LCS (e.g., the process, locations, and insurance coverage). This leaves individuals uninformed, or confused about LCS, with some unable to describe the screening process [22, 27, 29, 68, 72]. For example, in a 2022 study, only 22.9% of Chinese respondents were aware of early lung cancer detection via LDCT [48]. Similarly, migrant Chinese livery drivers in the USA had never heard of LCS, nor were they aware of insurance coverage for it [72]. Negative attitudes toward LCS and doubts about its benefits also represent barriers [22, 27, 69]. Factors such as low interest, perceived inconvenience, and skepticism about LCS effectiveness led some to resist participation [22, 25, 69]. Individuals who feel healthy, lack symptoms, or do not perceive themselves at risk are more likely to dismiss screening as unnecessary [22, 25]. Additionally, LCS participation was 0.24 times lower among those with fatalistic beliefs (e.g., not wanting to know cancer status, P = 0.002) [16]. As one participant noted, “If God wants me to go, I’ll go” [69].

Both previous reviews [16, 27] and recent articles [32, 46, 68, 69, 73] identify that psychological factors like stress, anxiety, and fear of screening or cancer diagnosis further hinder participation. Concerns include false positives, radiation exposure, results waiting times, and the implications of incidental findings, such as follow-up tests or treatments [16, 32, 46, 68, 69, 71, 73]. In one review, 33% of individuals cited fear of diagnosis or radiation as reasons for avoiding screening (OR = 0.10, P < 0.001) [27] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Time constraints and competing issues

Reviews [16, 22, 25, 27] and recent articles [32, 43, 68, 71, 72] identified a lack of time, scheduling conflicts, competing priorities, and caregiving responsibilities as barriers to LCS. Participants talked about the time it took for different stages of the screening, such as travel time and time to complete the scan, and talked about the difficulty and cost of trying to fit this around work [27, 32, 43, 68, 71, 72] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2A, Fig. 3B).

Other and unclear findings

The reviews and recent articles found inconsistent relationships between LCS and factors such as individuals’ age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking, education, and healthcare providers’ characteristics, including age, specialty, race/ethnicity, and year of service (Supplementary 1 − Table S2C). Some studies found that LCS rates increase with age [13, 14, 16, 23, 31, 40, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66], while others showed a decrease [38] or no significant relationship [11, 12, 37]. Most studies found no significant LCS differences between the sexes [11, 12, 27, 37, 51, 55, 63], though some indicated lower participation among women [38, 62, 66] or men [13].

One previous review [16] and some recent articles [27, 31, 37, 38, 41, 50, 66] reported generally lower LCS participation among minority races/ethnicities. However, other recent studies found that these differences were often not statistically significant [11, 12, 51, 52, 55, 62, 63] and previous reviews reached no conclusive findings on this issue [24, 26, 27]. Higher educational achievement was related to increased LCS participation in most of the previous reviews [16, 25, 26] and recent articles [13, 55, 66], though some found no significant variation by education [11, 37, 52].

Some studies found LDCT orders were higher among healthcare providers [25, 59] aged 40–49 years (P = 0.03), of Asian race/ethnicity (P = 0.02), and with internal medicine specialty (P = 0.002). However, other studies found no significant differences in LCS ordering by provider age, race/ethnicity, specialty, or graduation year [59, 62] (Supplementary 1 − Table S2C).

Age

Both previous reviews [16, 23, 27] and recent articles [11–14, 31, 37, 38, 40, 41, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66] have found an inconsistent relationships between age and LCS. Some studies found an increasing rate of LCS as age increased [13, 14, 16, 23, 31, 40, 50, 52, 62, 63, 66], while others found decreasing rate of LCS [38, 41] or no significant relationships [11, 12, 37]. For instance, a review by Huang and colleagues revealed that increasing age was related to an increase in LCS rate, with individuals aged ≥ 50 years had 1.94 times higher LCS rate than individuals aged < 50 years (OR, 95% CI; 1.94(1.52–2.49)) [23]. Compared to Chinese individuals aged 40–44 years, LCS rate was higher in those aged 45–49 years (aOR, 95% CI; 1.09(1.02–1.17)), 50–54 years (1.18(1.10–1.27)), 55–59 years (1.24(1.15–1.33)), 60–64 years (1.28(1.19–1.37)) or 65–69 years (1.30(1.20–1.40)) [13]. In USA, the proportion of LCS was higher among individuals aged 65–79 years (19.2%) than those aged 55–64 years (15.2%p = 0.04) [52].

Race

A previous review [16] and recent articles [27, 31, 37, 38, 41, 50, 66] and found that LCS participation was lower in minority races/ethnicities, while the difference was not significant in most of the recent articles [11, 12, 51, 52, 55, 62, 63] and no conclusive results have been reported in the previous reviews [24, 26, 27]. For example, a previous meta-analysis of five studies found that among eligible individuals, LCS rates were 57% lower among Black people compared to White people (OR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.25–0.74). However, in four studies, LCS completion rates after referral did not significantly differ between Black and White individuals (OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.74–1.19) [24]. Similarly, the LCS rate was 0.52 times lower among Black Americans (aOR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.28–0.96) than Whites [66]. LCS rate among individuals with Medicare insurance plans in the USA was lower in other race/ethnicity cohorts (1.7%) or non-Hispanic Black people (2.2%) compared to non-Hispanic Whites (3.7%) [38]. Despite lower rates of LCS observed among non-Whites, the variation was not significant (aOR 95%CI: 0.83(0.66–1.05)) [55].

Sex

Most of the previous reviews [16, 23, 27] as well as recent articles [11–13, 37, 38, 51, 55, 62, 63, 66] found inconsistent relationships between sex and LCS, with the majority of studies finding the lack of differences between men and women [11, 12, 27, 37, 51, 55, 63]. A lower rate of screening participation among women was found in some studies [38, 62, 66], whereas other studies found a lower screening participation among men [13] or no significant variations [11, 12, 27, 37, 51, 55, 63]. For instance, the LCS rate was 59% higher among Chinese women (aOR 95%CI: (1.59, 1.47–1.72)) than among men [13]. In the USA, the screening rate of men was 27% higher than women [62]. In the previous review, LCS rate did not differ between females and males, both in the total population (OR 95% CI: 1.18 (0.96–1.44)) or high-risk population group (OR 95% CI: 0.68 (0.42–1.10)); however, females have 32% times (OR 95% CI: 1.32 (1.15–1.52)) more LCS participation rate in the general population group (excluding high-risk group) [23].

Education

Higher educational achievement was related to increased LCS participation in most of the previous reviews [16, 25, 26] and recent articles [13, 55, 66], while some studies found a decreasing rate of screening among individuals with higher educational achievement [55] or no significant difference by educational status [11, 37, 52]. For instance, the LCS rate was 28% higher among Chinese individuals who completed undergraduate or above educational level (aOR 95%CI: 1.28(1.20–1.36)) compared to primary school or below educational attainment [13]. Individuals who attended college in North America have about two times higher LCS rates (aOR:1.84, 95% CI; 1.07–3.15) compared to those who completed high school or below [66]. Nevertheless, the LCS rate was higher among USA individuals who completed high school or less (aOR 95%CI: 1.25(1.07–1.46)) than those who completed college or higher education [55].

Smoking

There is a lack of consistency regarding the relationship between smoking and LCS participation. Some recent articles found a variation in LCS participation across smoking status [13, 41, 50, 66], while previous reviews [23, 25, 27] and some recent articles did not find variations by smoking status [37, 40, 63]; an inconsistent finding also reported by a previous review [16]. For example, in China, compared to never-smokers, screening participation was higher among former smokers (aOR 95%CI: 1.18(1.06–1.32)), while it was lower among current smokers (0.89(0.82–0.97)) [13]. In USA, the LCS rate was about twofold among individuals who attempted to quit smoking (aOR 95%CI: 1.77 (1.17–2.67)) [66]. In the previous review, smoking as a barrier was reported by two included studies, while one included study reported that smoking was related to increased LCS participation [16].

Characteristics of healthcare providers

There is inconsistent evidence regarding the variation of LCS by healthcare providers characteristics [25, 59, 62]. Ordering of LCS service varied by the characteristics of healthcare providers, such as age (p = 0.03), race (p = 0.02) and medical speciality (p = 0.002). For instance, total LDCT orders were higher among healthcare providers [25, 59] aged 40–49 years (32%), Asian race (32%), and with internal medicine speciality (40%). However, LDCT ordering was not varied across healthcare providers’ gender (p = 0.24), professional degree type (p = 0.12) or the status of having international graduate (p = 0.07) [59]. Another study also found a lack of variations of LCS ordering by the healthcare providers’ age, speciality, year of graduation and race/ethnicity [62].

Quality appraisal of included studies and reviews

Four reviews fulfilled 10 or more of 11 JBI critical appraisal criteria, with two of these achieving full scores (Supplementary 1 − Table S3). All reviews presented clear research questions and inclusion criteria, and identified study gaps; however, some lacked clear search strategies, appraisal criteria, and publication bias assessment. According to the MMAT, 38 recent articles met all criteria, while 13 had one or more “no” or “can’t tell” scores, and three were ineligible for detailed appraisal. Low scores were primarily because of non-representative sample sizes, uncertain sampling strategies, and high non-response rates (Supplementary 2).

Discussion

This review synthesised systematic reviews and recent articles, providing comprehensive evidence on barriers and facilitators to LCS participation. Facilitators included organisational-level (program promotion, trained staff, integration of LCS with other services, and supportive technology), healthcare provider-level (information provision, clear recommendations, positive patient relationships), and individual-level (health services experience, cancer awareness). Barriers included organisational-level (limited access, health insurance, workforce, communication, information resources, technology), healthcare provider level (limited LCS skills and/or knowledge and training, sub-optimal referral processes, and insufficient awareness of health insurance), and individual-level (low awareness of LCS and its cost coverage by health insurance, fear of being diagnosed with cancer, time constraints). The barriers and facilitators align with those in other cancer screening programs (e.g., colorectal, breast, cervical) [10, 78, 95–97], highlighting the importance of incorporating country-specific evidence and insights from other cancer screening programs to improve LCS efforts.

This review highlights the importance of addressing the broader structural and social determinants that underpin barriers to LCS. Unlike other cancer screening programs that are population-based, LCS is eligibility-based, primarily targeting long-term smokers—many of whom experience compounded disadvantage due to socioeconomic hardship, lower educational attainment, and limited healthcare access [98–100]. Smoking addiction is deeply socially patterned, with higher prevalence among individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, including those affected by unemployment, housing insecurity, and intergenerational trauma [99, 101]. These high-risk populations are also more likely to encounter social stigma, both internalised and systemic, which can further discourage engagement with preventive services such as LCS [102–104]. Additionally, understanding the interplay of stigma, cultural exclusion, and structural inequities is critical for explaining why those at greatest risk for lung cancer are often least likely to participate in screening [105]. These compounding barriers not only undermine the equity of screening programs but may also exacerbate disparities in lung cancer outcomes. As such, efforts to improve LCS participation must go beyond education and awareness campaigns. They must explicitly address social context by embedding screening within culturally safe and community-driven services, fostering trust with underserved populations, and confronting the structural forces—such as poverty and discrimination—that limit access to care for those most in need [106, 107].

This study also underscores the importance of strengthening health education and awareness campaigns to improve the knowledge and attitudes of individuals and healthcare providers about LCS [108–110]. Providing tailored LCS health education and awareness campaigns through digital and non-digital media has been associated with higher screening participation [108–110]. Effective strategies include educational videos, discussions during individual or community meetings, dissemination of LCS information via community bulletin boards, brochures, or social media, and using mail/email reminders. For healthcare providers, interactive group learning, webinars, online educational materials led by clinical champions, and professional or social platforms yielded positive outcomes [108–110]. For instance, weekly LCS appointments increased significantly after digital campaigns (17.4 to 26.2). Individuals responded better on Google (click-through rates increased from 1.8 to 5.9%) or Facebook (0.8% vs. 2.6%), and healthcare providers on LinkedIn (1.1% vs. 0.3%) or X (0.2% vs. 0.3%) [109]. Another study reported a 49% increase in cancer screenings, including LCS, following social media and mobile health interventions [108]. While digital dissemination of educational materials holds promise for increasing LCS participation, it is essential to recognise that without addressing structural barriers, such as digital exclusion, language diversity, and limited culturally relevant content—these interventions may inadvertently widen existing disparities [49, 57].

This review highlights the critical need for strategies to mitigate health insurance and financial-related barriers to LCS. Collaborations with governmental and non-profit organizations to establish, expand, and sustain financial assistance programs can significantly enhance LCS participation by covering associated costs, including transportation and opportunity costs incurred during screening participation [110, 111]. Additionally, strengthening partnerships between healthcare systems and insurance providers to support policy reforms is essential. These reforms should ensure comprehensive screening cost coverage, equitable and competitive reimbursement rates, and streamline authorization processes through automated systems, thereby promoting more efficient and accessible LCS services [25, 74].

LCSP initiatives are primarily limited to high-income countries, likely due to insufficient health insurance coverage in low-income countries. Expanding universal health coverage through a human rights approach is, therefore, essential to enhance global LCS access. Lessons from low-income countries, such as Rwanda, which has achieved significant universal health coverage, could inform these efforts [112]. Universal health coverage expansion aligns with the Sustainable Development Goal Target 3.8, highlighting its potential positive impact on LCS coverage worldwide if equitably implemented [113, 114]. Additionally, to improve LCS access, resources such as technology, a trained workforce, and infrastructure funding are critical. Access to LCSPs in rural areas, in particular, could be improved by using mobile screening programs and expanding healthcare funding that supports the expansion of infrastructure in these regions; for example, mobile LDCT screening in the USA has improved participation rates [110, 115].

This review also indicates that individuals with health service visiting experience have better screening participation [73, 77]; thus, integrating LCS with other routine medical services, such as annual checkups and visits to breathing centres, could further increase participation [73, 77, 110]. Ensuring adequate, culturally diverse staff, providing sufficient health education materials, integrating technology for referrals and follow-ups, and dedicating ample time to screening are vital for delivering personalized LCS, ultimately improving screening participation and lung cancer outcomes [110, 115].

Caution is needed when interpreting these results globally, as the included studies were primarily from high-income or upper-middle-income countries with advanced infrastructure, particularly the USA. Outside of the USA, more research from jurisdictions with LCS programs or where the implementation of such programs is planned is warranted to identify place-specific facilitators and enablers of participation, particularly for priority populations who may experience unique challenges to accessing health services, such as cancer screening services. Improved routine data collection, including the integration of cancer registries and screening registries and supportive legislation, is also required to ensure evidence-based decisions regarding the design and implementation of LCS programs can be determined [116–118]. Additionally, this review synthesizes insights from previous systematic reviews and recent studies, providing comprehensive evidence on the barriers and facilitators affecting LCS, an expanding and evolving program. As some countries plan to initiate LCS programs (e.g., Australia’s launch is scheduled for 2025), this review’s findings from this review are invaluable for guiding both the launch and adaptation of screening services. By leveraging these insights, countries can proactively address potential barriers, capitalize on identified opportunities, and optimise the effectiveness of their LCSPs.

Conclusion

This review identified multiple barriers and facilitators of LCS participation at the individual, healthcare provider, and organisational levels. Leveraging facilitators such as tailored health education and awareness campaigns through various platforms is required to improve knowledge and attitudes towards LCS services. Expanding universal health coverage and strengthening partnerships between health systems and insurance companies are essential to address health insurance and financial challenges. Providing LCS through mobile screening programs, ensuring a trained workforce, offering information resources, integrating supportive technology, and allocating sufficient time for screening procedures are also critical to increasing LCS participation and ultimately, enhancing lung cancer outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Table S1: Search query in the PubMed databases for lung cancer screening worldwide conducted using both an umbrella review and a systematic review. Table S2A: The barriers to lung cancer screening participation. Table S2B: The facilitators for lung cancer screening participation. Table S2C: Inconsistent relationships between various factors and lung cancer screening participation. Table S3: The critical appraisal results for reviews included in the umbrella review

Supplementary Material 2. Quality appraisal articles included in the top-up systematic review using a Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) appraisal tool

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Tsegaw Amare Baykeda, Ken Carter, and Jesse Chen for their support during the article screening as second reviewers and Thomas Andrade for his assistance in designing Figure 3. We extend our thanks to NHMRC for funding this project.

Abbreviations

- aOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- EHRs

Electronic Health Records

- LCS

Lung Cancer Screening

- LCSPs

Lung Cancer Screening Programs

- LDCT

Low Dose Computed Tomography

- HCPs

Healthcare Providers

Authors' contributions

SAB and HMB were responsible for conceptualisation, methodology development, article searches, data extraction, data synthesis, manuscript drafting, and revision. GG and AD contributed to the conceptualisation, interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

GG was supported by the NHMRC Investigator Grant (#2034453). This study was undertaken under the auspices of the Centre of Research Excellence in Targeted Approaches to Improve Cancer Services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians (TACTICS, #1153027). The funders had no direct or indirect involvement in the study’s design, data analysis, interpretation, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

All data reported in this study were extracted from publicly available published articles. All pertinent information from the included articles has been included within the main manuscript and supplementary materials.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable due to aggregated data having been extracted from publicly available and published peer-reviewed journal articles.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sewunet Admasu Belachew and Habtamu Mellie Bizuayehu are joint first authors.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today (version 1.1). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2024. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today. Accessed 4 June 2024.

- 3.Sharma R. Mapping of global, regional and national incidence, mortality and mortality-to-incidence ratio of lung cancer in 2020 and 2050. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27(4):665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Niksic M, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X, Man J, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, He Q, et al. Temporal trends of the lung cancer mortality attributable to smoking from 1990 to 2017: a global, regional and national analysis. Lung Cancer. 2021;152:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Mi M, Zhu N, Yuan Z, Ding Y, Zhao Y, et al. Global burden of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer attributable to occupational carcinogens in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Ann Med. 2023;55(1): 2206672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lung Cancer Policy Network. 2024. Interactive map of lung cancer screening (second edition). Available from: www.lungcancerpolicynetwork.com/interactive-map/. Cited on 01 July 2024.

- 8.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Heuvelmans MA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for lung cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(10):962–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azar D, Murphy M, Fishman A, Sewell L, Barnes M, Proposch A. Barriers and facilitators to participation in breast, bowel and cervical cancer screening in rural Victoria: a qualitative study. Health Promot J Austr. 2022;33(1):272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Pan IWE, Tak HJ, Vlahos I, Volk R, Shih Y-CT. Assessment of uptake appropriateness of computed tomography for lung Cancer screening according to patients meeting eligibility criteria of the US preventive services task force. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2243163–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]