Abstract

Epigenetic mechanisms restrict the expression of imprinted genes to one parental allele in diploid cells. At the Igf2r/Air imprinted cluster on mouse chromosome 17, paternal-specific expression of the Air noncoding RNA has been shown to silence three genes in cis: Igf2r, Slc22a2, and Slc22a3. By an unbiased mapping of DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS) in a 192-kb region flanking Igf2r and Air, we identified 21 DHS, of which nine mapped to evolutionarily conserved sequences. Based on the hypothesis that silencing effects of Air would be directed towards cis regulatory elements used to activate genes, DHS are potential key players in the control of imprinted expression. However, in this 192-kb region only the two DHS mapping to the Igf2r and Air promoters show parental specificity. The remaining 19 DHS were present on both parental alleles and, thus, have the potential to activate Igf2r on the maternal allele and Air on the paternal allele. The possibility that the Igf2r and Air promoters share the same cis-acting regulatory elements, albeit on opposite parental chromosomes, was supported by the similar expression profiles of Igf2r and Air in vivo. These results refine our understanding of the onset of imprinted silencing at this cluster and indicate the Air noncoding RNA may specifically target silencing to the Igf2r promoter.

Imprinted genes use epigenetic modifications to restrict gene expression to one of the two parental alleles present in a diploid cell. The cumulative analyses of different sets of imprinted genes in mice and humans indicate that imprinted and nonimprinted genes use similar epigenetic modifications to regulate transcription. Imprinted expression arises because at least one epigenetic feature is restricted to one of the two parental chromosomes (da Rocha and Ferguson-Smith 2004; Delaval and Feil 2004). The imprinting mechanism has an advantage as a model for epigenetic gene regulation in mammals, because it is cis-acting and thereby allows a direct comparison of the active and silent allele in the same nuclear environment. Although the imprinting mechanism is not yet fully understood, it is generally appreciated that allele-specific silencing arises through specific epigenetic modifications of the regulatory elements needed to activate a gene.

The Igf2r/Air imprinted cluster on mouse chromosome 17 contains four imprinted genes that span 513 kb (http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus). It displays the main features associated with imprinted genes, including a tendency to be clustered with at least one noncoding RNA (ncRNA) that shows reciprocal parental-specific expression (Sleutels and Barlow 2002; Verona et al. 2003). In this imprinted cluster, three protein-coding genes Igf2r, Slc22a2, and Slc22a3 show maternal-specific expression and the Air ncRNA shows paternal-specific expression (Fig. 1A). The remaining genes in this region Plg, Slc22a1, and Mas1 show restricted tissue-specific expression and are not imprinted (Fig. 1A). It is now becoming more appreciated that imprinted expression can vary in different tissues and in development. Igf2r is a widely expressed gene that is biparentally expressed in pre-implantation embryos but is maternally expressed in the post-implantation embryo, the placenta, and all adult stages except brain and germ cells, where it continues to be biparentally expressed (Barlow et al. 1991; Szabo and Mann 1995; Hu et al. 1999). The expression profile of the Slc22a2 and Slc22a3 genes is very different, as these genes show restricted tissue-specific and developmental expression. Both are repressed in pre- and post-implantation embryos but show maternal-specific expression in the placenta that switches to biparental expression before birth in Slc22a3 but continues until birth for Slc22a2 (Zwart et al. 2001a). Another characteristic feature of imprinted genes is that most are distinguished by a CpG island-type promoter that is associated with only 50% of nonimprinted mammalian genes. Little information is available on the transcriptional control of CpG island promoters of nonimprinted genes aside from the observations that they show an active chromatin conformation, normally lack DNA methylation, and are enriched in histone acetylation even when transcriptionally silent (Antequera 2003; Roh et al. 2005). The Air and Igf2r promoters, however, show DNA methylation of their respective silent parental alleles in embryos, placenta, and adults (Fig. 1A). The Air promoter is pre-emptively methylated during female gametogenesis and this is maintained on the maternal chromosome in diploid cells. Methylation of the Igf2r promoter is acquired on the paternal allele coincident with silencing in post-implantation embryos and is present in all tissues except brain, where the paternal Igf2r promoter is active (Stoger et al. 1993; Hu et al. 1999). The methylation mark on the maternal Air promoter constitutes the “imprint” for this gene cluster and the late acquisition of methylation on the paternal Igf2r promoter may act to maintain silencing in later developmental stages (Li et al. 1993).

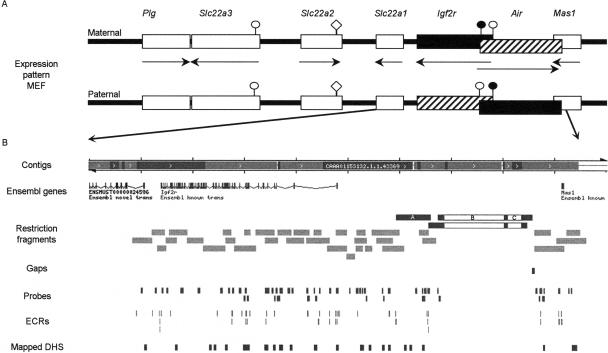

Figure 1.

Overview of investigated region in the mouse chromosome 17 bA cluster. (A) The chromosome map spans 513 kb of mouse chromosome 17 band A and contains seven known transcripts (http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus) (Lyle et al. 2000). The expression pattern in mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) is shown for the maternal and paternal chromosome. Note that the 108-kb Air ncRNA overlaps the 5′ part of the Igf2r transcript by 30 kb and the 3′ part of the Mas1 transcript by 1 kb. Black boxes indicate expressed genes, striped boxes indicate imprinted silencing that affects one parental allele, white boxes indicate tissue-specific silencing that affects both alleles, arrows indicate transcriptional orientation. The Plg and Mas1 genes mark the known limits of this imprinted cluster. Note that Slc22a2 and Slc22a3 show imprinted expression in the embryonic placenta but are not expressed in MEFs. Parental-specific DNA methylation is present on the Igf2r and Air promoters. (Black circle) DNA-methylated CpG island promoter; (white circle) unmethylated CpG island promoter. Note that the Slc22a2 promoter is a weak CpG island (white diamond). (B) Modified ENSEMBL map (http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus), including custom tracks (available on request) of the region including the Slc22a1, Igf2r, Air, and Mas1 genes. (Contigs row) The ENSEMBL contig view is shown, where the continuous sequence coverage stops in the 5′ region of Mas1. Note that two restriction fragments end in this region and their sizes were predicted from AJ249895. (ENSEMBL genes row) The ENSEMBL genes of this area are indicated; note that in this build Slc22a1 is annotated as “Ensembl novel trans” and the Air ncRNA is not annotated. (Restriction fragments row) Three significant differences between the public mouse sequence (C57Bl6 strain) and the sequence of the mouse strains used here (129Sv and FVB) were detected in three restriction fragments (black boxes): A—A polymorphic BclI fragment that contains a 6-kb LINE insertion only in the 129Sv mouse strain (Supplemental Fig.1); B—a 29.5-kb and C—a 6.8-kb insertion, shown in an EcoRI and an EcoRV fragment, that were not detected in any genomic DNA (see Supplemental Fig.1) and are false insertions in the ENSEMBL sequence. The positions of all other tested restriction fragments are shown as light gray boxes. (Gaps row) The gaps in the region coverage; (Probes row) DNA blot probes used for the DHS assays; (ECRs row) location of evolutionarily conserved regions (see also Figs. 2 and 3); (DHS row) the position of the identified DHS. Note that the only gap in the coverage of the region consists of a 100% interspersed repeat sequence of 1.1 kb.

Clustering of imprinted genes implicates the action of long-range cis-acting regulatory elements in the silencing mechanism. This has been verified for the Igf2r/Air cluster, where a single imprint control element (ICE) that maps to Igf2r intron 2 has been shown to control allele-specific silencing of all imprinted genes in this 513-kb cluster (Zwart et al. 2001a). The Igf2r intron 2 ICE contains the Air ncRNA promoter (Lyle et al. 2000). Experiments that truncated the Air ncRNA from 108 kb to 3 kb have now shown that silencing of Igf2r, Slc22a2, and Slc22a3 requires the Air ncRNA (Sleutels et al. 2002). The details of the mechanism by which Air silences three genes in cis, whether it depends on transcription per se or on a functional role for the ncRNA, are not yet clear. Evidence has been presented that argues against a direct involvement of an RNAi-mediated silencing mechanism acting via the 30-kb transcription overlap between Igf2r and Air (Sleutels et al. 2003). However, the Igf2r/Air transcription overlap does allow the possibility that Air ncRNA transcription could interfere in some manner with regulatory elements needed for Igf2r expression on the paternal chromosome.

Our goal was to identify all regulatory elements that could control expression of Igf2r and Air and test for parental-specific regulation. Because of the lack of conservation of imprinted expression between the mouse and human Igf2r genes (Xu et al. 1993; Killian et al. 2001), we used an unbiased approach to map candidate transcriptional regulators in the mouse Igf2r/Air region using DHS assays. DHS assays identify short regions of approximately 200-400 bp that are sensitive to the action of nucleases because of nucleosome displacement or altered chromatin structure. These nuclease-sensitive regions are often the binding sites of transcription factors and are likely to be cis-acting regulatory elements, such as promoters and enhancers (Elgin 1988; McArthur et al. 2001). Many genes regulated in a tissue- or developmental-specific fashion show changes in DNase I sensitivity coincident with transcriptional induction (Stamatoyannopoulos et al. 1995), and several studies have demonstrated a functional correlation between DHS and transcription regulatory elements (Urnov 2003).

Here we mapped the parental-specific regulation of DHS in a 192-kb region flanking the Igf2r and Air genes and also correlated them to evolutionarily conserved regions (ECRs) in the mouse and human genome. In total, 21 DHS were identified, and nine were associated with an ECR. Surprisingly, only the DHS at the Igf2r and Air promoters show parental-specific behavior, while the remainder are present on both parental chromosomes. These data, supported by analysis of gene expression profiles in vivo, indicate that Igf2r and Air share the use of these putative regulatory elements, albeit on opposite parental chromosomes. These results refine our understanding of the onset of imprinted silencing at this cluster and indicate that the Air ncRNA may specifically target silencing to the Igf2r promoter.

Results

Comparison of available mouse genome sequences

Two mouse sequences containing the Igf2r/Air region are available: ENSEMBL m33 (Fig. 1B) derived from the C57Bl6 strain, and AJ249895 derived mostly from the 129Sv strain. ENSEMBL m33 currently annotates Slc22a1 as a “novel transcript,” and the sequence breaks in the 5′ part of Mas1 (Fig. 1B, http://www.ensembl.org). The 5′ part of Mas1 plus 205 kb of deleted sequence are present on the unlinked supercontig (NT_097166 ENSEMBL m33). Comparison of AJ249895 to ENSEMBL m33 reveals three significant differences: a 6-kb LINE insertion present in AJ249895 (bp54265-60542) but not in ENSEMBL m33, and 29.5-kb and 6.8-kb blocks of repetitive DNA present in ENSEMBL m33 (bp12230658-12260106, bp12261825-12268588) but not in AJ249895 (respectively A, B, C in “Restriction fragments” row in Fig. 1B). As these differences affect this study, we tested the sequence information in genomic DNA. Insertion A is present in 129Sv but not in C57Bl6 and FVB and is thus a strain polymorphism. Insertions B and C are not present in 129Sv, C57Bl6, or FVB DNA and are therefore false insertions into ENSEMBL m33 (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Identification of DHS and parental-specific regulation

DHS assays were performed on the 192-kb Igf2r/Air region in different mouse cell lines and organs. More than 29 different restriction fragments (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table 1), spanning from intron 1 of Slc22a1 to the first exon of Mas1, were investigated by hybridization of DNA blots with different probes. For some regions, additional fragments were investigated to fine map the identified DHS. The only gap in this coverage is 1.1 kb long and consists solely of interspersed repeats (ENSEMBL m33 bp 12273778-12274939, Gaps row in Fig. 1). Embryonic stem (ES) cells were used to represent the “inner cell mass” of the pre-implantation embryo and mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) to represent 13.5-days-postcoitus (dpc) embryo cells. Spleen and brain from wild-type mice were used to investigate adult mouse tissues. To test the parental origin of the identified DHS, MEFs were derived from 13.5-dpc embryos carrying the Thp deletion on the maternal allele (MEF-F, Thp/+) or on the paternal allele (MEF-B1, +/Thp). Note the maternal allele is written on the left side and the Thp deletion spans 6 Mbp, including the complete region shown in Figure 1A (Barlow et al. 1991).

In total, 21 DHS were identified and are indicated by vertical arrows numbered 1-21 in Figure 2. Closely spaced DHS were combined under one name (i.e., DHS 6, 9, 12, 13, and 19). The DHS can be broadly grouped into weak and strong DHS, depending on the strength of the hybridizing band in the DNA blot, although some variation between the cell types was seen. Thirteen DHS (2, 6-9, 11-13, and 15-19) are visible as strong DNase I-specific bands on the DNA blots (marked by horizontal arrows in Fig. 2). Eight DHS are in the weak DHS group (DHS 1, 3-5, 10, 14, 20, and 21) (marked by asterisks in Fig. 2). DHS21 shows an unusual pattern and was only detectable on a large 14.2-kb EcoRI fragment but not on smaller fragments (data not shown), indicating that this DHS represents a longer region with increased nuclease sensitivity (wide arrow in Fig. 2B at 237 kb). It is notable that seven of the 21 DHS (4, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 19) map directly to, or at least to the borders of, interspersed repeats.

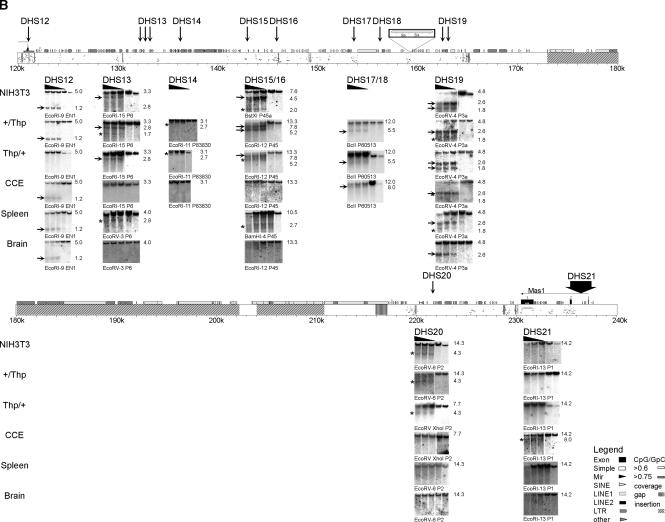

Figure 2.

DHS map of the Igf2r/Air cluster. All identified DHS were shown at their correct position within the genomic organization of the investigated region. Because of its length, this region is presented in two parts. (A) The region from Slc22a1 to the Igf2r promoter; (B) the region from the Igf2r promoter to Mas1. Note that blots from DHS12 at the Igf2r promoter are shown in A (BglII fragments) and B (EcoRI fragments) to show the overlap between the two maps. The PipMaker plot (Schwartz et al. 2000) above the DNA blots shows the position and transcriptional orientation of genes by numbered exons (black boxes) and horizontal arrows on top of the sequence, together with the gene name. Symbols indicating positions of repeats identified by RepeatMasker (A.F.A. Smit, R. Hubley and P. Green, unpubl.) and CpG islands are shown (see legend). Evolutionary conservation to the human sequence between 50% and 100% is shown below by short horizontal bars in the PipMaker plot. ECRs defined as >70% identity over >50 bp, excluding exons and interspersed repeats are indicated by gray vertical bars within the PipMaker plot. Sequences not investigated for DHS, as well as erroneously assembled sequence insertions (Supplemental Fig.1), are indicated by hatched boxes. The strain 129Sv specific LINE insertion (Supplemental Fig.1) is indicated by a white box above the PipMaker plot in B; numbers in this box refer to sequence AJ249895. Note that the 12-kb BclI fragment shown for DHS17 and DHS18 in B is created by this LINE insertion, as the ENSEMBL m33 sequence predicts a 19-kb BclI fragment (see Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1). The mapped positions of identified DHS are indicated by vertical arrows together with the name of the DHS with closely related DHS combined under one name. For each identified DHS, a representative set of DNA blots is shown from MEF cell lines [NIH3T3 wild type (+/+), MEF-B1: paternal Thp deletion (+/Thp), MEF-F: maternal Thp deletion (Thp/+)], from CCE embryonic stem cells, and from spleen and brain of an adult FVB mouse. DNase I concentrations are indicated by a black triangle above the blot; the two lanes on the right side of each blot contain nuclei treated only with incubation buffer at 0°C and 37°C. The enzyme used for restriction digests and the hybridization probe are indicated for each blot (location of used restriction fragments and probes are listed in Supplemental Table 1). The DHS were visible on DNA blots as additional bands to the expected restriction fragment in lanes with DNase I treated DNA. The NIH3T3 blot of DHS8 shows an exception where two restriction fragments were visible in all lanes, which is likely due to a cell line-specific polymorphism. Strong DHS bands are indicated by horizontal arrows and weak ones by asterisks on the left of each DNA blot. The sizes of the shown fragments are indicated on the right in kilobase pairs.

Parental-specific regulation of DHS

In total, 21 DHS were identified in various cell lines and tissues, with three located at promoter regions: DHS1 (Slc22a1), DHS9 (Air), and DHS12 (Igf2r). Whereas DHS1 at the Slc22a1 promoter is present on both parental alleles, DHS9 at the Air promoter is present on the unmethylated paternal allele (Thp/+) but not on the methylated maternal allele (+/Thp) in MEFs. DHS12 at the Igf2r promoter shows the reciprocal pattern and is present only on the unmethylated maternal allele but not on the methylated paternal allele. DHS9 and DHS12 are the only parental-specific DHS in this 192-kb region; the remaining 19 DHS are equally present on the maternal and paternal chromosome (Fig. 2).

Developmental regulation of DHS in the Ig2r/Air region

Both DHS9 at the Air promoter and DHS12 at the Igf2r promoter contain multiple DHS that show a tissue-specific or developmental stage-specific pattern. In the case of DHS9, multiple weak DHS are visible in ES cells and in brain. This pattern changes in embryo and spleen, where the 1-kb DHS-specific fragment increases in strength, compared with other fragments. In the case of DHS12, only one strong DHS is visible in ES cells, whereas in embryonic fibroblasts, a second, weaker DHS is visible but only with some restriction enzymes (cf. DHS12 on a BglII fragment in Fig. 2A and DHS12 on an EcoRI fragment in Fig. 2B). Three DHS (2, 17, and 21) are specific to ES cells. Of the remaining 15 DHS that lie outside of the three promoters, 11 are absent in ES cells but present in MEFs (DHS 3, 5-8, 13-16, 18, and 20) and may therefore be regulated in development. Three are present both in ES cells and MEFs (DHS4, 10, and 19) and may be constitutively present during mouse development. DHS11 was only detectable in the MEF-F (+/Thp) cell line and might therefore be specific for this cell line. Twelve DHS were investigated in the adult spleen and brain. Of these, six DHS (1, 7, 9, 12, 13, 16, and 19) were detected in spleen, whereas only four DHS (1, 9, 12, and 19) were found in brain, indicating a tissue-specific regulation.

Figure 2.

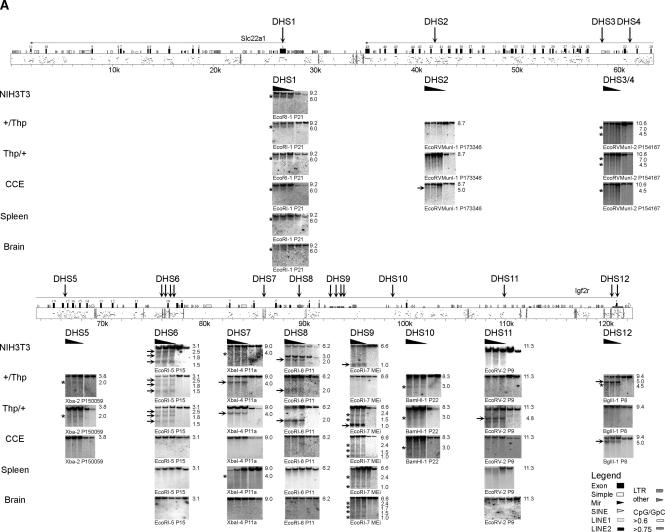

ECRs

Comparative genomics approaches to identify ECRs have proven useful in the detection of regulatory elements. We therefore investigated the 21 mapped DHS from the 192-kb Igf2r/Air region for correlation to ECRs. We used the PipMaker and VISTA programs to determine the conservation of 221 kb from ENSEMBL m33 (this including the 36.2-kb repeat-rich inserted sequences shown in Fig. 1B) to the human ENSEMBL hg35 orthologous sequence that contains the MAS1, IGF2R, and SLC22A1 genes and spans 281 kb (Mayor et al. 2000; Schwartz et al. 2000). ECRs were identified by applying criteria of >70% identity over >100 bp without gaps (Pennacchio and Rubin 2001) and excluding exons and interspersed repeats identified by RepeatMasker (A.F.A. Smit, R. Hubley and P. Green, unpubl.). Using these stringencies, only seven ECRs were identified over the whole region of which only one ECR (clustered gray bars at 76 kb in Fig. 2A) coincided with a DHS (DHS6), whereas all the others, including the highest-conserved ECR (86% 143 nt at 117 kb in Fig. 2A), were not associated with a DHS. Lowering the stringency for ECRs to 70% identity over 50 bp without gaps resulted in 43 discrete ECRs (gray bars in Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 2) that were closely clustered in some regions and so were further grouped into 17 main ECRs (Fig. 1B). The reduced stringency scan correlated three other DHS (7, 12, and 16), in addition to DHS6, with an ECR. The Igf2r promoter DHS12 maps to an ECR, but the Air promoter DHS9 does not. Five other DHS (5, 8, 13, 19, and 20) were located within 2 kb of the closest ECR, whereas the remaining 12 DHS were located further than 2 kb from the nearest ECR. The correlation between DHS and evolutionary conservation is summarized in Figure 3. The nine DHS that are closely linked to ECRs also map to a peak in the conservation landscape as defined by VISTA, with the exception of the ECR related to DHS13 (at 130 kb in Fig. 2B), which was only identified by PipMaker.

Figure 3.

Overview of DHS and evolutionary conservation. The position and regulation of the 21 DHS identified in the 192-kb Mas1-Slc22a1 interval are shown relative to mouse-human evolutionarily conserved regions (ECRs). (A) Numbered vertical arrows indicate the position of all identified DHS relative to the gene map and ECRs; “X” indicates regulated DHS absent in the tested sample; a blank space indicates the sample was not tested. For each cell line (ES, MEF) and organ (spleen, brain), all identified DHS were shown on one line. Open arrows represent single or multiple DHS at regions free of interspersed repeats but >2 kb distant from ECRs (DHS 1-2, 4, 9-10, 17-18, 21); black arrows mark DHS located at an interspersed repeat (DHS 3, 8, 11, 13-15, 19); shaded arrows show repeat-free DHS located within 2 kb of an ECR (DHS5-7, 12, 16, 20). The parental-specific DHS12 at the Igf2r promoter and DHS9 at the Air promoter are marked by an asterisk. Note that DHS11 is most likely a cell line-specific DHS. The lack of DHS between DHS19 and DHS20 is due to incorrect sequence insertions presented in Figure 1. (B) The positions and transcriptional orientation of the genes are indicated by horizontal arrows; solid circles at the start of the arrow indicate CpG island promoters; the Mas1 promoter has not yet been identified. Below the gene map, ECRs, selected from the PipMaker output (defined in Fig. 2), are indicated by filled circles. Gray circles indicate PipMaker ECRs associated with a DHS that were also shown below as conservation peaks in the output of the VISTA program (Mayor et al. 2000). Black circles indicate PipMaker ECRs not shown in the VISTA output. The VISTA plots in the bottom panel display the percent identity of the human and mouse genomic sequence relative to the mouse sequence but only values above 50% are shown. Conserved exons are indicated by black shading and the conservation peaks, corresponding to the PipMaker ECRs, in gray. The location of the Igf2r and Air promoter are indicated with arrows; note that the Air promoter lacks sequence conservation.

Expression patterns of Igf2r and Air

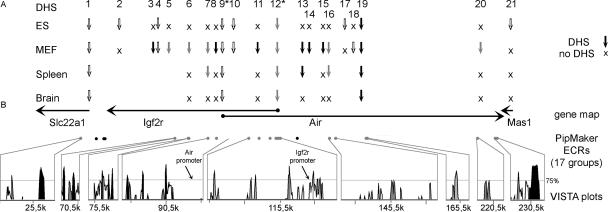

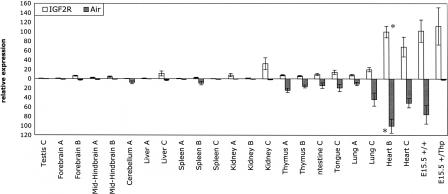

The finding that all DHS outside of the Igf2r/Air promoter regions were present on both parental alleles (Fig. 2) indicated the possibility that Igf2r and Air share these putative regulatory elements, albeit on opposite parental chromosomes. Sharing of the same cis-regulatory elements by two promoters would predict a similar expression pattern and expression levels of Igf2r and Air. To test this, we investigated the relative mRNA levels of Igf2r and Air in different mouse tissues and embryo by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 4). Three broad categories of expression (high, medium, and low) were identified that were similar for both Igf2r and Air. Embryo and adult heart expressed the highest levels of both Igf2r and Air. Adult thymus, intestine, tongue, and lung express medium levels of both Igf2r and Air. The remaining tissues tested (adult testes, forebrain, mid-hindbrain, cerebellum, liver, spleen, kidney) express low levels of both Igf2r and Air. In general, although there is some discordance in tissues in the low expression category (liver sample C, spleen sample B, kidney samples A and C), it can be seen that tissues that express high, medium, or low levels of Igf2r similarly express high, medium, or low levels of Air.

Figure 4.

Relative expression levels of Igf2r and Air. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Igf2r and Air expression. Total RNA from organs of four different adult male C57Bl6/CBA mice (sample C was obtained by pooling organs of two individuals) and 15.5-dpc embryos was reverse transcribed and analyzed for Air (shaded bars) and Igf2r (open bars) expression by qPCR using Taqman probes. Expression data were normalized to Cyclophilin A mRNA, and Igf2r and Air expression in the heart of sample B was set to 100 (marked by an asterisk). The numbers on the x-axis indicate the relative amounts of Igf2r and Air in different tissues but do not make a comparison between Igf2r and Air (see Supplemental Table 2 for the data used). The standard deviation representing three technical replicates for each sample is indicated. (E15.5 +/+) Wild-type embryo at 15.5 dpc. The E15.5 +/Thp embryo littermate that has a paternal deletion of the proximal Igf2r/Air imprinted cluster (Barlow et al. 1991) was used as a control for background levels of Air RNA.

Discussion

This study used an unbiased approach to investigate 192 kb of mouse chromosome 17, including two imprinted genes (Igf2r and Air) and part of two nonimprinted flanking genes (Mas1 and Slc22a1) for DHS. The limits of this map were chosen from transgene experiments that indicated that the major regulatory elements for Igf2r and Air expression and for genomic imprinting are located in this region (Wutz et al. 1997; Sleutels and Barlow 2001; Zwart et al. 2001b). Nuclease-sensitive regions have frequently been reported to be sites of ubiquitous and tissue-specific transcription factor binding and are therefore likely to be regulatory elements, such as enhancers, insulators, or repressors (Urnov 2003). We identified 21 DHS in different mouse developmental stages and tissues. Three sites are located at the promoters, whereas 18 sites lie outside the promoters and are candidate cis-regulatory regions for the Igf2r and Air promoters (see overview Fig. 3). A bioinformatic analysis was used to test whether the identified DHS are conserved between human and mouse. It revealed that only 9/21 were associated with ECRs; of these, only four DHS lie within an ECR. However, five DHS map within 2 kb of the closest ECR, which may constitute a relatively short distance in chromatin of 8-13 nucleosomes, depending on the length of the linker DNA. This short distance raises the possibility that proteins bound to DNA at an ECR may cause chromatin alterations in distant nucleosomes. All 21 DHS were tested for parental-specific regulation and only the two DHS located at the Igf2r and Air promoters showed parental-specific behavior. The remaining 19 DHS were equally present on the maternal and the paternal allele and, thus, have the potential to activate Igf2r on the maternal allele and Air on the paternal allele. These results indicate that Igf2r and Air could share the use of the same putative cis-acting regulatory elements, albeit on opposite parental chromosomes. This conclusion is supported by the similar tissue expression profile of the Igf2r and Air genes in embryonic and adult mouse tissues.

Evolutionary conservation versus unbiased approaches

The approach of using cross species conservation to predict regulatory regions has been successful for many genes in diverse organisms (Wasserman and Sandelin 2004). Four genomic regions have been investigated recently in comparable detail to the one presented here: the mouse beta globin locus (19 DHS in 170 kb) (Hardison et al. 1997; Bulger et al. 2003); the mouse Sprr locus (16 DHS in 260 kb) (Martin et al. 2004); the mouse imprinted Igf2/H19 locus (26 DHS in 130 kb) (Koide et al. 1994); and the human imprinted SNRPN locus (eight DHS in 150 kb) (Schweizer et al. 1999). The beta globin and Sprr studies also demonstrated a discordance between DHS and ECRs. In the Sprr cluster, 6/16 DHS mapped directly to ECRs (Martin et al. 2004). In the beta globin study, 11/19 DHS map directly to ECRs, including eight located at the locus control region (LCR). For the imprinted Igf2/H19 locus, complete data are not available on the conservation of all mapped DHS, but some DHS have been linked to conserved sequences (Koide et al. 1994; Ainscough et al. 2000; Ishihara et al. 2000).

The 192-kb region analyzed here contained 21 DHS and 17 grouped ECRs. Of the 21 DHS identified, six DHS with unique sequences were located at or within 2 kb of an ECR; eight with unique sequences were clearly unlinked to an ECR while the remaining seven DHS are repetitive sequences and would have been excluded from comparative genome screens. Allowing the caveats that some DHS used rarely in development may not have been identified or that some ECRs identified here would not survive comparison with multiple distant mammalian genomes, these results identify discordance between DHS and ECRs in this region, which is also seen in the studies cited above. The discordance in the Igf2r/Air region may reflect the lack of conservation of genomic imprinting between the mouse and human Igf2r genes. The human IGF2R gene shows a polymorphic type of imprinted expression that is limited to embryonic stages, whereas adult tissues have been reported to show only biparental expression (Xu et al. 1993; Killian et al. 2001). This contrasts to the maintenance of imprinted Igf2r expression in most tissues of the mouse embryo and adult (Braidotti et al. 2004). Alternatively, it may be that some types of regulatory element are not conserved in evolution. It has been reported that CpG island promoters are more tolerant of sequence changes than other regulatory elements are (Antequera 2003). If other regulatory elements also show a rapid divergence in evolution this adds support for the use of unbiased approaches in their identification.

DHS mapping to interspersed repeats

In addition to the accepted concept of regulatory elements residing in unique noncoding sequences, our results show that 7/21 DHS in this region lie in interspersed repeats. The best example is DHS19, a strong, ubiquitous DHS present in all tested material that mapped to a region containing LTR/ERV (long terminal repeats/endogenous retrovirus) and simple repeats (position 163 kb in Fig. 2) (A.F.A. Smit, R. Hubley and P. Green, unpubl.). Interspersed repeats have been suggested to function as cis-acting transcription regulators in some circumstances. For example, the mouse beta globin LCR was shown to express an intergenic transcript from an LTR-ERV9 promoter, which is responsible for local chromatin remodeling (Pi et al. 2004). In addition, SINE repeats have been reported to contain DHS at the imprinted Igf2/H19 region and at the nonimprinted Sprr locus (Moore et al. 1997; Martin et al. 2004). Mammals are unique in that the majority of genes are interspersed with high-copy repeats. Although the impact of these “interspersed” repeats on gene expression is not yet clear, it is possible that bioinformatic prediction of regulatory elements that omit repetitive DNA may miss some information.

CpG island promoter DHS regulated by DNA methylation

DHS9 associated with the Air promoter was only found on the paternal chromosome that expresses Air, whereas DHS12 associated with the Igf2r promoter was only found on the maternal chromosome that expresses Igf2r. Thus, these two DHS show parental-specific regulation that correlates the presence of the DHS with the expressed parental allele. However, the presence of a DHS may not reflect the expression status of these promoters, as the Air promoter DHS9 is also present in a slightly modified form in ES cells, which do not express Air (Braidotti et al. 2004). ES cells carry the maternal-specific DNA methylation imprint on the Air promoter (Stoger et al. 1993), which indicates that the presence of the DHS on the paternal allele likely correlates with the absence of DNA methylation. Regulation of constitutive DHS by DNA methylation may be a common feature of imprinted genes and ICEs, as similar results were found at the H19 DMD and the Prader-Willi/Angelman ICE (Khosla et al. 1999; Perk et al. 2002) and the mouse U2af1-rs1 and the Nespas/Gnasxl promoters (Feil et al. 1997; Coombes et al. 2003). CpG island promoters have been suggested to create open chromatin by default and to constitutively bind ubiquitous transcription factors in the absence of gene expression (Antequera 2003). Although DNase I hypersensitivity has not previously been systematically investigated in CpG island promoters, our results indicate that constitutive DHS may be an additional feature of these promoters.

A model for transcriptional regulation of Igf2r and Air

The demonstration that all nonpromoter DHS are present on both parental alleles together with the in vivo expression profile of Igf2r and Air supports a model whereby Igf2r and Air share the same cis-acting transcription regulators, albeit on opposite parental chromosomes. The model we propose is that, on the maternal chromosome, multiple cis-acting regulatory elements drive Igf2r expression while the Air promoter is silent. In contrast, on the paternal chromosome, the same cis-acting regulatory elements drive Air expression and the Igf2r promoter is silent. The behavior of the maternal chromosome appears straightforward, as the Air promoter is pre-emptively silenced by a DNA methylation imprint acquired in the oocyte. The sequence of events on the paternal chromosome is not yet clear, as the paternal Igf2r promoter is initially expressed in pre-implantation embryos and ES cells (Szabo and Mann 1995). Because Air expression is needed to silence Igf2r in cis on the paternal chromosome (Sleutels et al. 2000), we suggest that imprinted expression of Igf2r coincides with expression of Air as cells differentiate. The existence of a 30-kb transcription overlap between Igf2r and Air (Fig. 1A) allows the possibility that Air ncRNA transcription could interfere in some manner with specific regulatory elements, such as enhancers, that are needed for Igf2r expression on the paternal chromosome. The data presented here, however, do not support this possibility as all DHS outside the Igf2r/Air promoters are present on both parental alleles. The only regulated DHS on the paternal chromosome lies at the Igf2r promoter. This indicates that the silencing action of the Air noncoding RNA may be specifically directed to the Igf2r promoter.

Methods

Quantitative PCR expression analysis

Total RNA from organs of 4 different adult male C57BL6 mice (ABC) was purified from frozen tissue using RNAwiz (Ambion). Sample C was obtained by pooling organs of two individual mice. RNA samples were treated with DNA-free (Ambion) to remove DNA. Reverse transcription of 1 μg of RNA was performed by using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (MBI Fermentas) and oligo hexamer primers. For quantitative PCR of the cDNA, Taqman universal MasterMix (Applied Biosystems) was used. The final concentration of primers was 900 nM, with 200 nM probe concentration in 25-μL reaction volume. The ABI PRISM 7000 detection machine was used for quantitative PCR. All steps were performed as described in the Applied Biosystems protocol with a cycle number of 40 and annealing temperature of 60°C. Quantification of RNA was achieved by the standard curve method using serial dilutions of cosmid COS4L (Air) or cDNA (adult mouse heart, Igf2r, and Cyclophilin A). Relative quantification and statistics were performed as described (Applied Biosystems); Cyclophilin A was used for normalization. The amount of Igf2r and Air in the heart of mouse B was used as a calibrator and set to 100.

Probes and primers

For qPCR of Air, the Taqman probe Air middle (FAM-TACAAGTGATTATTAACTCCACGCCAGCCTCA-TAMRA) and primers Air TQF (5′-GACCAGTTCCGCCCGTTT-3′) and Air TQR (5′-GCAAGACCACAAAATATTGAAAAGAC-3′) were used. For qPCR of Igf2r, the Taqman probe Igf2r ex48 (FAM-CCAAGACTAGGCAAGGACGGGCAAGA-TAMRA) and primers Igf2r-Tg fwd (5′TCCTACAAGTACTCAAAGGTCAGCAA-3′) and Igf2r-Tg rev (5′CGCCTTGGTGGTGATATGG-3′) were used. For qPCR of Cyclophillin A, the Taqman probe (5′-FAM-TCGTGGATCTGACGTGCCGCC-TAMRA-3′) and primers (Fwd: 5′-AGGGTTCCTCCTTTCACAGAATT-3′) and Rev: 5′-GTGCCATTATGGCGTGTAAAGT-3′) were used.

Bioinformatic analysis

The human sequence used was chromosome 6, bp 160280000-160560724 NCBI35 release 30.35c update 22.3.2005; the mouse sequence was chromosome 17, bp 12057822-12297822 NCBI33 freeze May 2004 release 30.33f update 22.3.2005 (http://www.ensembl.org/). All positions in the PipMaker and VISTA plots (Figs. 2, 3 and Supplemental Fig. 2) and in Supplemental Table 1 are relative to the mouse sequence. Custom tracks for this mouse sequence as displayed in Figure 1B are available on request. Evolutionary conservation was studied using PipMaker (Schwartz et al. 2000) (http://pipmaker.bx.psu.edu/pipmaker/) with the “chaining” and the “high-sensitivity” options. All repeats were masked in the human and mouse sequences by RepeatMasker (A.F.A. Smit, R. Hubley and P. Green, unpubl., http://www.repeatmasker.org/) using the “slow” setting. ECRs were identified by using the “concise” output of PipMaker and by VISTA (Mayor et al. 2000) (http://www-gsd.lbl.gov/vista/) with defined parameters (window length 50 bp, conservation level 70%).

Cell lines and mice

CCE ES cells were provided by Erwin Wagner (IMP, Vienna, Austria). NIH3T3 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (cat. no. CRL-1658). Thp fibroblasts were prepared using a 3T3 protocol from 13.5-dpc FVB embryos, and mouse tissues were prepared from FVBN mice (Taconic, Ry, Denmark).

DNase I assay

Whole organs (spleen, brain) from adult 2- to 3-month-old mice were minced to 2-mm cubes and rendered to a single cell suspension in a Dounce homogenizer. Spleen and brain were used because of their rapid dispersal to single cells; organs with a large amount of connective tissue, such as kidney and heart, gave no result in the DNase I assay used here. Tissue culture cells (107-108 cells) were trypsinized into a single cell suspension. The preparation of nuclei and the DNase I digest were as described (Sambrook and Russell 2001). The DNase I (10 U/μL, RNase free, Roche) concentration ranges were: ES cells, 78-22 U/mL; MEF cells, 1000-90 U/mL; spleen, 330-90 U/mL; brain, 200-50 U/mL. The reaction was stopped by adding DNA lysis buffer (0.6 mg/mL Proteinase K, 1.25% SDS, 11 mM Tris, 44.4 mM NaCl, 49 mM EDTA) and incubating at 55°C overnight. DNA was extracted and restriction enzyme digested and analyzed by DNA blots using standard methods. Hybridization probes were amplified by PCR or gel purified from cosmid cloned DNA. Membranes were exposed to an imaging plate (FujiFilm) that was scanned (Typhoon 8600, Amersham Biosciences) and manipulated in Adobe Photoshop.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Regha Kakkad, Laura Spahn, Mathew Sloane, and Teiji Wada for reading the manuscript, to Christine Unger for technical assistance, and to Mathew Sloane for help with primer design. F.P. is supported by a grant from the Bm:bwk GEN-AU project, S.S. is supported by the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds (B.I.F.) PhD Scholarship Foundation for Basic Research in Biomedicine, K.W. is supported by the FWF Austrian Science Fund, and the laboratory is supported by the Austrian Academy of Sciences. D.B. is a member of the EU Framework 6 Network of Excellence “The Epigenome.”

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.3783805.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

References

- Ainscough, J.F., John, R.M., Barton, S.C., and Surani, M.A. 2000. A skeletal muscle-specific mouse Igf2 repressor lies 40 kb downstream of the gene. Development 127: 3923-3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antequera, F. 2003. Structure, function and evolution of CpG island promoters. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60: 1647-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, D.P., Stoger, R., Herrmann, B.G., Saito, K., and Schweifer, N. 1991. The mouse insulin-like growth factor type-2 receptor is imprinted and closely linked to the Tme locus. Nature 349: 84-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, G., Baubec, T., Pauler, F., Seidl, C., Smrzka, O., Stricker, S., Yotova, I., and Barlow, D.P. 2004. The Air non-coding RNA—An imprinted cis-silencing transcript. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 69: (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bulger, M., Schubeler, D., Bender, M.A., Hamilton, J., Farrell, C.M., Hardison, R.C., and Groudine, M. 2003. A complex chromatin landscape revealed by patterns of nuclease sensitivity and histone modification within the mouse beta-globin locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 5234-5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes, C., Arnaud, P., Gordon, E., Dean, W., Coar, E.A., Williamson, C.M., Feil, R., Peters, J., and Kelsey, G. 2003. Epigenetic properties and identification of an imprint mark in the Nesp-Gnasxl domain of the mouse Gnas imprinted locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 5475-5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha, S.T. and Ferguson-Smith, A.C. 2004. Genomic imprinting. Curr. Biol. 14: R646-R649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaval, K. and Feil, R. 2004. Epigenetic regulation of mammalian genomic imprinting. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14: 188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin, S.C. 1988. The formation and function of DNase I hypersensitive sites in the process of gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 19259-19262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil, R., Boyano, M.D., Allen, N.D., and Kelsey, G. 1997. Parental chromosome-specific chromatin conformation in the imprinted U2af1-rs1 gene in the mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 20893-20900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison, R., Slightom, J.L., Gumucio, D.L., Goodman, M., Stojanovic, N., and Miller, W. 1997. Locus control regions of mammalian beta-globin gene clusters: Combining phylogenetic analyses and experimental results to gain functional insights. Gene 205: 73-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.F., Balaguru, K.A., Ivaturi, R.D., Oruganti, H., Li, T., Nguyen, B.T., Vu, T.H., and Hoffman, A.R. 1999. Lack of reciprocal genomic imprinting of sense and antisense RNA of mouse insulin-like growth factor II receptor in the central nervous system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 257: 604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, K., Hatano, N., Furuumi, H., Kato, R., Iwaki, T., Miura, K., Jinno, Y., and Sasaki, H. 2000. Comparative genomic sequencing identifies novel tissue-specific enhancers and sequence elements for methylation-sensitive factors implicated in Igf2/H19 imprinting. Genome Res. 10: 664-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla, S., Aitchison, A., Gregory, R., Allen, N.D., and Feil, R. 1999. Parental allele-specific chromatin configuration in a boundary-imprinting-control element upstream of the mouse H19 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 2556-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian, J.K., Nolan, C.M., Wylie, A.A., Li, T., Vu, T.H., Hoffman, A.R., and Jirtle, R.L. 2001. Divergent evolution in M6P/IGF2R imprinting from the Jurassic to the Quaternary. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10: 1721-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide, T., Ainscough, J., Wijgerde, M., and Surani, M.A. 1994. Comparative analysis of Igf-2/H19 imprinted domain: Identification of a highly conserved intergenic DNase I hypersensitive region. Genomics 24: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, E., Beard, C., and Jaenisch, R. 1993. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature 366: 362-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyle, R., Watanabe, D., te Vruchte, D., Lerchner, W., Smrzka, O.W., Wutz, A., Schageman, J., Hahner, L., Davies, C., and Barlow, D.P. 2000. The imprinted antisense RNA at the Igf2r locus overlaps but does not imprint Mas1. Nat. Genet. 25: 19-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, N., Patel, S., and Segre, J.A. 2004. Long-range comparison of human and mouse Sprr loci to identify conserved noncoding sequences involved in coordinate regulation. Genome Res. 14: 2430-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, C., Brudno, M., Schwartz, J.R., Poliakov, A., Rubin, E.M., Frazer, K.A., Pachter, L.S., and Dubchak, I. 2000. VISTA: Visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics 16: 1046-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, M., Gerum, S., and Stamatoyannopoulos, G. 2001. Quantification of DNaseI-sensitivity by real-time PCR: Quantitative analysis of DNaseI-hypersensitivity of the mouse beta-globin LCR. J. Mol. Biol. 313: 27-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T., Constancia, M., Zubair, M., Bailleul, B., Feil, R., Sasaki, H., and Reik, W. 1997. Multiple imprinted sense and antisense transcripts, differential methylation and tandem repeats in a putative imprinting control region upstream of mouse Igf2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 12509-12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchio, L.A. and Rubin, E.M. 2001. Genomic strategies to identify mammalian regulatory sequences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 100-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perk, J., Makedonski, K., Lande, L., Cedar, H., Razin, A., and Shemer, R. 2002. The imprinting mechanism of the Prader-Willi/Angelman regional control center. EMBO J. 21: 5807-5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi, W., Yang, Z., Wang, J., Ruan, L., Yu, X., Ling, J., Krantz, S., Isales, C., Conway, S.J., Lin, S., et al. 2004. The LTR enhancer of ERV-9 human endogenous retrovirus is active in oocytes and progenitor cells in transgenic zebrafish and humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 805-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T.Y., Cuddapah, S., and Zhao, D. 2005. Active chromatin domains are defined by acetylation islands revealed by genome-wide mapping. Genes & Dev. 19: 542-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J. and Russell, D.W. 2001. Molecular cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Schwartz, S., Zhang, Z., Frazer, K.A., Smit, A., Riemer, C., Bouck, J., Gibbs, R., Hardison, R., and Miller, W. 2000. PipMaker—A web server for aligning two genomic DNA sequences. Genome Res. 10: 577-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, J., Zynger, D., and Francke, U. 1999. In vivo nuclease hypersensitivity studies reveal multiple sites of parental origin-dependent differential chromatin conformation in the 150 kb SNRPN transcription unit. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8: 555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels, F. and Barlow, D.P. 2001. Investigation of elements sufficient to imprint the mouse Air promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 5008-5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels, F. and Barlow, D.P. 2002. The origins of genomic imprinting in mammals. Adv. Genet. 46: 119-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels, F., Barlow, D.P., and Lyle, R. 2000. The uniqueness of the imprinting mechanism. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10: 229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels, F., Zwart, R., and Barlow, D.P. 2002. The non-coding Air RNA is required for silencing autosomal imprinted genes. Nature 415: 810-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels, F., Tjon, G., Ludwig, T., and Barlow, D.P. 2003. Imprinted silencing of Slc22a2 and Slc22a3 does not need transcriptional overlap between Igf2r and Air. EMBO J. 22: 3696-3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A., Goodwin, A., Joyce, T., and Lowrey, C.H. 1995. NF-E2 and GATA binding motifs are required for the formation of DNase I hypersensitive site 4 of the human beta-globin locus control region. EMBO J. 14: 106-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoger, R., Kubicka, P., Liu, C.G., Kafri, T., Razin, A., Cedar, H., and Barlow, D.P. 1993. Maternal-specific methylation of the imprinted mouse Igf2r locus identifies the expressed locus as carrying the imprinting signal. Cell 73: 61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, P.E. and Mann, J.R. 1995. Allele-specific expression and total expression levels of imprinted genes during early mouse development: Implications for imprinting mechanisms. Genes & Dev. 9: 3097-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov, F.D. 2003. Chromatin remodeling as a guide to transcriptional regulatory networks in mammals. J. Cell. Biochem. 88: 684-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona, R.I., Mann, M.R., and Bartolomei, M.S. 2003. Genomic imprinting: Intricacies of epigenetic regulation in clusters. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 19: 237-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, W.W. and Sandelin, A. 2004. Applied bioinformatics for the identification of regulatory elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5: 276-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutz, A., Smrzka, O.W., Schweifer, N., Schellander, K., Wagner, E.F., and Barlow, D.P. 1997. Imprinted expression of the Igf2r gene depends on an intronic CpG island. Nature 389: 745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y., Goodyer, C.G., Deal, C., and Polychronakos, C. 1993. Functional polymorphism in the parental imprinting of the human IGF2R gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 197: 747-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart, R., Sleutels, F., Wutz, A., Schinkel, A.H., and Barlow, D.P. 2001a. Bidirectional action of the Igf2r imprint control element on upstream and downstream imprinted genes. Genes & Dev. 15: 2361-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart, R., Verhaagh, S., de Jong, J., Lyon, M., and Barlow, D.P. 2001b. Genetic analysis of the organic cation transporter genes Orct2/Slc22a2 and Orct3/Slc22a3 reduces the critical region for the t haplotype mutant t(w73) to 200 kb. Mamm. Genome 12: 734-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/; Human Genome Browser.

- http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/; Mouse Genome Browser.

- http://pipmaker.bx.psu.edu/pipmaker/; PipMaker.

- http://www-gsd.lbl.gov/vista/; VISTA.

- http://www.repeatmasker.org/; RepeatMasker, open-3.1.0.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.