Abstract

Integrated information theory (IIT) offers an axiomatic framework based on phenomenological properties, allowing the quantification and characterization of consciousness through a measure known as Φ. According to IIT, Φ reflects the level of consciousness and is expected to decrease with loss of consciousness, although empirical data supporting this claim remain limited. In this study, we analyzed two functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) datasets acquired during anesthesia (propofol-induced) and natural sleep to determine whether Φ changes with the loss and recovery of consciousness. Our analysis was conducted using the fourth version of IIT. We constructed systems composed of five functional brain networks, computed transition probability matrices from fMRI time series data, and derived Φ values based on these matrices. As predicted by IIT, Φ decreased during anesthesia-induced loss of consciousness at both global and local levels. Similarly, Φ was locally reduced within a system centered on posterior brain regions during sleep-induced loss of consciousness. Considering functional networks as system units, we found that the integrated information (Φ) of the brain is linked to fluctuations in consciousness levels. These findings indicate a strong association between consciousness and integrated information within the large-scale functional networks.

Keywords: integrated information theory, fMRI, anesthesia, sleep

Introduction

How consciousness emerges has not been elucidated. However, theories of consciousness attempt to explain subjective experience in objective terms (Ellia et al. 2021). Integrated information theory (IIT) of consciousness constructs an axiomatic system from phenomenological properties of our mind (Oizumi et al. 2014, Tononi et al. 2016, Albantakis et al. 2023), allowing the formulation of both the quality and quantity of consciousness by means of a measure called Φ. Despite the theoretical advancements, the hypotheses derived from IIT have not been adequately validated in empirical studies.

The formulation of IIT considers five phenomenal properties (intrinsicality, information, integration, exclusion, and composition) and then expresses them as physical properties (Oizumi et al. 2014, Albantakis et al. 2023). IIT posits an explanatory identity between each experience and the corresponding cause-effect structure specified by the physical substrate. The Φ introduced by IIT is referred to as the integrated information measure and is applicable exclusively to discrete Markov systems. This measure is derived by calculating the information generated when a system transitions to a specific state from a repertoire of possible states. In addition to the integrated information of discrete systems, several researchers have proposed measures known as dynamic or empirical integrated information of continuous systems, including integrated stochastic interaction Φ˜ (Barrett and Seth 2011), decoder-based integrated information Φ* (Oizumi et al. 2016a), geometric integrated information ΦG (Oizumi et al. 2016b), and integrated information decomposition ΦR (Mediano et al. 2021), which are applicable to any stochastic systems (Mediano et al. 2018). According to Barrett and Seth (2011), the measures quantify the information that the current state contains about a past state, using the empirical or spontaneous distribution to account for a priori uncertainty about the past state. The measures can be estimated for actual data through empirical distributions, provided stationarity can be assumed. IIT predicts that these Φ measures, whether based on discrete or continuous systems, will be associated with transitions in consciousness.

Several questions remain, but our understanding of conscious phenomena has significantly improved through the utilization of neuroimaging tools (Nemirovsky et al. 2023). Among these tools, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) stands out, enabling the observation of cortical activity in both spatial and temporal domains (Snider and Edlow 2020). fMRI assesses activity through patterns of blood flow, specifically using blood oxygen level-dependent signals (Ogawa et al. 1990, Logothetis 2008). fMRI studies measure brain activity in response to stimuli and task loads, as well as spontaneous brain activity; the latter is commonly referred to as resting-state fMRI. Research utilizing resting-state fMRI has unveiled a set of resting-state networks, comprising synchronized collections of cortical regions that reflect the functional organization of the brain during periods of rest (Damoiseaux et al. 2006). Studies have reported on the brain as a system composed of resting-state networks and their interactions across various states of consciousness (Coppola et al. 2022a, 2022b, Nemirovsky et al. 2023, Onoda and Akama 2023, 2024, Luppi et al. 2024).

To apply IIT analysis (Oizumi et al. 2014, Albantakis et al. 2023) to fMRI data, three considerations should be taken into account: the granularity of the elements comprising the system, the number of elements, and the temporal scale. First, the elements comprising a system in IIT are posited as irreducible units, with neurons in the brain fitting this description (Oizumi et al. 2014). Generally, it is assumed that causality at the micro level, such as individual neurons, is complete, while causality at the macro level may not be established. However, a theoretical study proposes that causal power may exert greater influence at the macro than at the micro level (Hoel et al. 2016, Marshall et al. 2024). Consequently, research exploring systems incorporating neural population activity (Leung et al. 2021) or large-scale networks (Nemirovsky et al. 2023) as the elements can also make significant contributions to consciousness studies. Next, IIT analysis for a system with many elements is computationally infeasible. Hence, Nemirovsky et al. (2023) limited the number of elements in the system to five. They have selected five elements within each distinct functional network and found anesthesia-induced changes in Φ within the systems of some functional networks, suggesting that changes in Φ can be detected by appropriate elemental selections. However, Φ within a global system that comprises functional networks as elements has not yet been explored. Third, consciousness is constrained not only by space but also by temporal scales (Northoff and Huang 2017, Northoff and Lamme 2020). For example, an imaging study employing the meta-matrix approach explored the complexity of functional-structural dynamics in patients with impaired consciousness across various time scales (Coppola et al. 2022a). This indicates that the time scale of fMRI is applicable for capturing macro-scale complexity.

To investigate consciousness, an effective approach is to compare physiological characteristics within an individual during the awake state with two prominent nonpathological unconscious states: general anesthesia and natural sleep (Alkire et al. 2008, Guldenmund et al. 2017, Cofré et al. 2020, Zelmann et al. 2023). The above-described fMRI study using anesthesia demonstrates that the alterations in Φ closely correspond to shifts in the levels of consciousness within the executive control network (ECN) and dorsal attention network (DAN). These networks are responsible for higher-order cognitive functions (Nemirovsky et al. 2023). Furthermore, sleep studies have reported reductions in ΦG and Φ˜ of systems, including the ECN, during the transition from the awake state to stages 1 and 2 (Onoda and Akama 2023, 2024). It has also been reported that anesthesia reduces ΦR, especially in the default mode network (DMN) (Luppi et al. 2024).

The primary aim of this study was to validate predictions made by IIT (Tononi et al. 2016) using fMRI data acquired during anesthesia and sleep. IIT posits that hierarchically organized grid-like cortical structures, such as those found in the posterior cortex, are suited for integrating information (Grasso et al. 2021). Grasso et al. (2021) indicated that subjective properties of experience can be accounted for by the cause-effect structure specified by the grid-like structures with lateral and recurrent connections, but not by the map-like structures without lateral connections. If the properties of Φ are maintained at the macro level (Hoel et al. 2016, Marshall et al. 2024), the Φ of systems constructed from fMRI data of the posterior cortex should show the consciousness-dependent changes. We hypothesized that Φ would decrease during sleep or anesthesia-induced loss of consciousness at the global and local systems. Additionally, we expected higher Φ values during REM sleep relative to deep non-REM sleep because higher Φ and conscious experience can be supported by intrinsic brain interactions even in the absence of sensory inputs and motor outputs. To achieve these, we constructed Markov systems using global or local functional networks as elements and calculated the integrated information Φ (Albantakis et al. 2023) as the metric. Recently, it has been demonstrated that not only each functional network but also the synergy between specific functional networks (e.g. DMN and ECN) is involved in the emergence of consciousness (Luppi et al. 2024). Therefore, we decided to examine the Φ in both systems within functional networks and between the networks. The selections of elements in systems were made with reference to the neural mechanisms implied by major theories of consciousness (Lamme 2003, Koch et al. 2016, Mashour et al. 2020).

Materials and methods

Anesthesia dataset

The anesthesia dataset (Kandeepan et al. 2020, Nemirovsky et al. 2023) utilized in this study is available at Openneuro.org (ds003171). The data were collected from 17 healthy volunteers (13 males and 4 females) with an average age of 24.0 ± 5.0 years. All subjects were right-handed and had no prior history of neurological disorders. Ethical approval for the study was secured from the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board and the Psychology Research Ethics Board of Western University (REB #104755).

Details of anesthesia administration and MRI measurements can be found in the supplementary document. In short, subjects experienced four states while receiving propofol: (i) Awake: Propofol had not been administered, and subjects were fully alert and communicative; (ii) Mild sedation: Propofol infusion began at this phase with a target effect-site concentration of 0.6 μg/ml. Subjects exhibited increased calmness and slower responses to verbal communication, ceased spontaneous conversation, became sluggish in speech, and only responded to loud commands; (iii) Deep sedation: The target effect-site concentration was incrementally increased by 0.3 μg/ml. Subjects no longer responded to verbal commands or engaged in conversation; (iv) Recovery: Propofol administration was terminated. Approximately 11 min later, the subjects showed clear and prompt responses to verbal commands. The fMRI measurements were performed with a repetition time (TR) of 2000 ms and maximally lasted for 512 s in each stage.

Sleep dataset

The sleep dataset included multimodal data comprising fMRI, electroencephalography (EEG), and video recordings of eye movements, all of which were concurrently collected during the sleep sessions of 17 healthy subjects (comprising 14 males and 3 females, with a mean age of 25.8 ± 3.3 years) conducted within an MRI scanner. Each subject participated in two separate experimental sessions, each separated by an interval of more than 2 weeks. The research protocol adhered to the ethical guidelines and was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, Japan. All subjects provided written informed consent before the data acquisition.

Subjects with regular sleep–wake cycles underwent simultaneous fMRI and EEG during sleep, following strict preparation protocols including scanner noise acclimation and 24-h abstinence from alcohol and caffeine. The acquired data were subjected to comprehensive preprocessing, including artifact removal and sleep stage classification using machine learning techniques. All sleep stages (Wake, N1, N2, N3, and REM) were incorporated into the final analysis after excluding three subjects due to data quality issues. As with the anesthesia dataset, detailed procedures and specifications for MRI/EEG measurements of the sleep dataset are available in the supplementary document. The fMRI measurements were performed with a TR of 2500 ms, and the maximum duration was 10240 s (2.84 h) per session. This was repeated as necessary until subjects reached full wakefulness or reported discomfort.

Analysis summary

Figure 1 illustrates the analysis flow employed in this study. The preprocessed fMRI data were first parcellated into 7 or 17 independent functional network elements based on Yeo’s atlas (Yeo et al. 2011). From these elements, time series data for five elements were selected for each system and binarized. The binarized data were used to compute a transition probability matrix (TPM), which is the probability of transitioning from one state to another. Based on the TPM, the integrated information (Φ) of each state was computed. Finally, based on the state of the individual and the session at each time point, we determined Φ and compared the value between the levels of consciousness (sleep stages and sedation levels).

Figure 1.

(a) Analysis flow. The fMRI data were preprocessed and divided into regions based on Yeo’s atlases. Five elements were selected from the time series, and Φ was calculated for the system. Based on the binarized time series, a TPM for the states of the elements was computed. Consequently, integrated information (Φ) was calculated for each state, and the Φ values for the different levels of consciousness were compared. (b) Spatial distributions of five elements within each system of intra-network and inter-network levels. The same number or color in a distribution map indicates that the regions are included in the same element. ECN, executive control network; DAN, dorsal attention network; VAN, ventral attention network; SMN, somatomotor network; LN, limbic network; DMN, default mode network; VN, visual network.

Parcellation

The preprocessed data were parcellated into 7 or 17 elements defined by Yeo et al. (2011), which provided atlases based on a data-driven analysis of resting-state fMRI data. The 7-network atlas, consisting of the visual network (VN), somatomotor network (SMN), DAN, ventral attention network (VAN), limbic network (LN), ECN, and DMN, was used for global-level analysis. Furthermore, an additional 7-network split atlas, which divides the voxels constituting each network, was used for intra-network level analysis. In this atlas, each functional network was further divided into clusters by a k-means algorithm for the spatial coordinates of the voxels within the network, in line with Nemirovsky et al. (2023). The voxels originally associated with each functional network were respectively grouped into five clusters. The 17-network atlas developed by Yeo et al. (2011) comprises networks that include two VN subcomponents, two SMN subcomponents, two DAN subcomponents, two VAN subcomponents, one temporoparietal network (TPN), two LN subcomponents, three ECN subcomponents, and three DMN subcomponents. This atlas was subsequently used for inter-network level analysis. The time series of voxels constituting each functional network or subcomponent were extracted and averaged.

Element selection

Due to constraints in computational resources and analysis time, the maximum number of analyzable elements in our IIT analysis was limited to five. This was consistent with the approaches by previous studies that conducted similar analyses of fMRI data (Nemirovsky et al. 2023). The element selections in the current study were hierarchical at the global, intra-network, and local inter-network levels. Both the intra-network and inter-network levels were considered subordinate to the global level, and no hierarchical relationship was assumed within the intra- and inter-network levels. The analyses at the global network level utilized the 7-network atlas. For the 7-network atlas, element selection was systematic, and all possible sets of elements were utilized. For each set, Φ was computed (described below), and the mean Φ value across the set was calculated. At the intra-network level, we used five clusters obtained from each of the seven networks as the elements. Their approximate distribution is shown in Fig. 1b.

We also included the local integration of information between networks as part of our analysis. Due to constraints in computational resources, we could not consider all combinations of functional networks at the local level; therefore, we carefully selected the systems to be analyzed by utilizing several theories of consciousness. At the inter-network level, we focused on four specific patterns of elements using the 17-network atlas. Set 1 (frontal set) was based on global neuronal workspace theory (GNWT), which assumes that a subset of cortical pyramidal neurons characterized by long-range excitatory axons, notably concentrated in prefrontal regions, establishes a horizontal neuronal workspace that connects various specialized, automated, and nonconscious processing systems (Dehaene and Changeux 2011). Hence, we selected elements spanning the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (Fig. 1b). For set 2 (balanced set), we selected the core components of the ECN, VAN, DMN, DAN, and the hippocampus (a subcomponent of the DMN) as the five elements. The hippocampus was included as an element because its activity is detected during the REM stage (Miyauchi et al. 2009), which is characterized by a higher frequency of dreaming. For set 3 (parietal set), IIT attributes phenomenological consciousness to the posterior cortex that spans occipital, temporal, and parietal regions (Koch et al. 2016, Boly et al. 2017). We selected the core and subcomponent of DMN, the posterior components of ECN and DAN, and TPN as five elements. For set 4 (occipital set), recurrent processing theory (RPT) posits that the recurrent processing involving the feedforward and feedback mechanisms is essential for consciousness and local processing in the sensory regions is sufficient for conscious experience (Lamme 2003). Therefore, we selected five components mainly spanning the occipital and temporal cortex (the central and peripheral VNs, the subcomponent of DMN (hippocampus), TPN, and the posterior component of DAN).

The following IIT analysis was applied to each set with five time series.

Binarized time series

To align the sampling frequencies (TR) in the two datasets, the time series data were resampled at 0.4 Hz or 0.5 Hz (corresponding to a TR of 2.5 s or 2.0 s, respectively) before the binarization. Subsequent analyses calculating Φ were conducted separately for each sampling frequency, and the corresponding Φ was averaged before the statistical analysis. The time series of each element was standardized with respect to its mean and standard deviation. Elements with a positive z-score for a particular time point were assigned 1 (above-baseline activity), and those with a negative z-score were assigned 0 (below-baseline activity). In this context, state refers to a combination of element values (1 or 0) within a system.

Transition probability matrix

In a system where each element assumes a binary value, a TPM is essential for quantifying the level of integrated information. The TPM represents the probability of transitioning from one state to another, including self-transitions, in a subsequent time point.

States were assigned an index according to little-endian rules, and the number of transitions was used to create a 32 × 32 square matrix. For example, if the transition from the state [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] (little-endian index = 1) to the state [0, 1, 0, 0, 0] (little-endian index = 2) occurred 15 times, the values in row 1 and column 2 were set to 15. To normalize the matrix, each row was divided by the number of times the state corresponding to its index appeared in the time series and transitioned to another state. If 100 transitions occurred from state 1 to other states in the time series, the row was normalized and the probability of the system transitioning from state 1 to state 2 was set to 0.15.

The lengths of time series for each subject and condition in the datasets were relatively small, considering the 32 possible states of the system. Therefore, the time series of the baseline condition for all subjects were concatenated. The TPM of each element set was calculated from the concatenated time series. State transitions were counted if the data at t and t + 1 were from the same subject (and the same session in the sleep dataset). The number of state transitions used to calculate the TPM was 3 418 (0.4 Hz) and 2 735 (0.5 Hz) in the anesthesia dataset and 15 368 (0.4 Hz) and 12 294 (0.5 Hz) in the sleep dataset.

Integrated information Φ

The calculation of Φ in this study was performed based on IIT version 4 (Albantakis et al. 2023) using the PyPhi toolbox (Mayner et al. 2018). A brief outline is provided below. In IIT version 4.0, the information structure called the Φ-structure corresponds to the quality of consciousness and is composed of distinctions and relations within the system’s composition (structured experience). Distinctions represent cause–effect states specified over subsets of units (or elements in this paper), captured by TPM. Relations reflect how the cause–effect power of these distinctions is interconnected. Both distinctions and relations are characterized by their integrated information. The sum of the Φ values of distinctions and relations—referred to as structure integrated information Φ, or “big Φ”—corresponds to the quantity of consciousness (Albantakis et al. 2023). The Φ reported in this paper reflects the big Φ. Φ was calculated for all 32 states and assigned to each time point based on the state of the system. For the anesthesia dataset, the mean Φ in each sedation stage of individuals was calculated. In the sleep dataset, the assigned Φ time series was averaged in 30-s epochs with no overlap, corresponding to the sleep stage ratings. Then, the mean Φ in each sleep stage of the measurement session was calculated.

Statistical analysis

The mean Φ of each stage for both datasets was normalized by dividing it by the grand mean for each control condition (wake stage). In addition, the mean Φ was averaged across the original and resampled data (0.4 Hz and 0.5 Hz). A linear mixed model analysis was applied to the Φ calculated for each element set of the two datasets. The dependent variable was the Φ for each stage of the subjects in the anesthesia dataset and for each stage of the measurement session in the sleep dataset. For each analysis for the anesthesia and sleep datasets, the sedation or sleep stage was included as a fixed factor, with the subject as a random factor. For the sleep dataset, the measurement session was also treated as a random factor. The post hoc tests were corrected for multiple testing by Holm’s method. These analyses were conducted using JASP version 0.18 (jasp-stats.org).

Results

Anesthesia dataset

Figure 2 shows the Φ values across the sedation stages in the anesthesia dataset. In some systems, the Φ values are commonly aligned with the sedation stages, decreasing during mild and deep sedation and increasing during recovery. At the global level, the Φ indicated a significant effect of sedation (F(3,48) = 7.20, P < .001), and the post hoc test revealed that the Φ was lower during the mild and deep sedation stages than during the wake and recovery stages (Ps < .05).

Figure 2.

Box plots illustrating the distribution of Φ across the sedation stages in the anesthesia dataset. (a) Global functional network level. (b–h) Intra-network levels in the ECN, DAN, VAN, SMN, LN, DMN, and VN, respectively. (i–l) Inter-network levels in frontal, balanced, parietal, and occipital regions, respectively. W, M, D, and R represent wake, mild sedation, deep sedation, and recovery, respectively. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with the bold horizontal lines indicating the median and the dashed lines indicating the mean. Horizontal lines above the plots denote significant differences from post hoc tests (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, all corrected by Holm’s method for multiple comparisons).

At the intra-network level, the Φ for the ECN, SMN, LN, and VN reflected no significant effect of sedation (Fs(3,48) < 2.27, n.s.). Conversely, the DAN Φ indicated a significant effect of sedation (F(3,48) = 4.25, P = .010), and the post hoc test revealed that the Φ was lower during the deep sedation and recovery stages than during the wake stage (Ps < .05). The VAN Φ reflected a significant effect of sedation (F(3,48) = 6.06, P < .001), decreasing significantly during the mild and deep sedation stages relative to during the wake stage (Ps < .05) and increasing during the recovery stage after the deep sedation (P < .05). Similarly, the Φ for DMN also showed an effect of sedation (F(3,48) = 5.16, P = .004). The Φ was lower for the deep sedation than for the wake stage (P < .05) and higher for the recovery stage than for the deep sedation stage (P < .05).

At the inter-network level, the Φ of the frontal set reflected a strong effect of the sedation stage (F(3,48) = 8.13, P < .001). The post hoc test revealed a decrease in Φ during the mild sedation, followed by a return to baseline levels during recovery (Ps < .05). Similarly, the Φ of the balanced set, which mainly consisted of the core elements in the major functional networks, also reflected an effect of the sedation stage (F(3,48) = 5.75, P = .002). The post hoc tests for the Φ of this system showed its decrease during the deep sedation stage relative to the wake stage (P < .001) and return during the recovery stage (P < .05). On the contrary, none of the Φ values in the parietal and occipital sets reflected any effects of the sedation stage (Fs(3,48) < 1.72, n.s.).

Sleep dataset

Figure 3 presents the Φ values corresponding to each sleep stage. Changes in Φ across the sleep stages were observed in several systems, and these differed from the systems showing changes during the sedation stages in the anesthesia dataset. First, the global system of the functional network exhibited no significant effects of the sleep stage (F(4, 22.1) = 1.42, n.s.). Next, in the intra-network level, the Φ of the ECN, VAN, LN, and DMN did not show any strong effects of the sleep stage (Fs < 2.84, Ps > .039), and the post hoc test revealed that there were no significant differences between the Φ of the sleep stages. Other networks showed main effects of the sleep stage (Fs > 4.00, Ps < .013). In detail, the Φ in DAN was reduced in the N1 and REM stages compared to the wake stage (Ps < .05), and the Φ in VN showed a reduction in the REM stage compared to the wake and N3 stages (Ps < .05). Conversely, in SMN, the Φ was particularly reduced in the N2 and N3 compared to the wake and N1 stages (Ps < .05) and was increased in the REM stage compared to the N2 stage (P = .015).

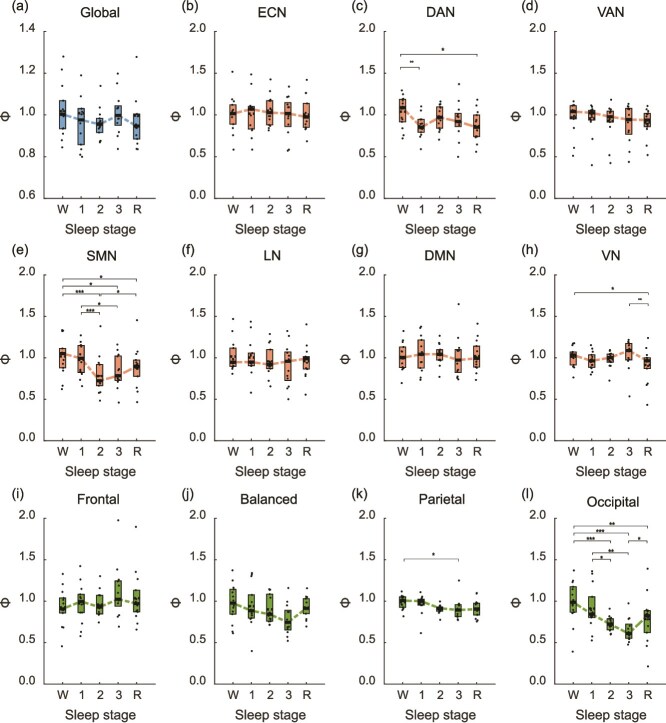

Figure 3.

Box plots illustrating the distribution of Φ across the sleep stage in the sleep dataset. (a) Global functional network level. (b–h) Intra-network levels in the ECN, DAN, VAN, SMN, LN, DMN, and VN, respectively. (i–l) Inter-network levels in frontal, balanced, parietal, and occipital regions, respectively. W, 1, 2, 3, and R denote each sleep stage (wake, N1, N2, N3, and REM, respectively). The boxes represent the IQR, with the bold horizontal lines indicating the median and the dashed lines indicating the mean. Horizontal lines above the plots denote significant differences from post hoc tests (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, all corrected by Holm’s method for multiple comparisons).

For the inter-network level, no changes were observed in the frontal and balanced sets with respect to the sleep stages (Fs < 2.65, n.s.), while the parietal and occipital sets demonstrated significant effects of the sleep stage (Fs > 4.25, Ps < 0.01). In the parietal set, the Φ was reduced during the N2 stage relative to the wake stage (P = .029). Lastly, a gradual decrease in Φ was observed in the occipital set as the sleep deepened (Ps < .05), and the Φ increased during the REM stage compared to the N3 stage (P = .035).

Next, we compared the prenormalized Φ values in the baseline (wake stage) between the systems (Fig. 4). This analysis aimed to test the expectation that systems corresponding to complex structures would exhibit higher Φ. In both datasets, each system exhibited diverse Φ values, and the patterns differed between the anesthesia and sleep datasets. In the anesthesia dataset, the VAN showed the highest Φ, followed by the SMN, LN, DMN, and VN with high Φ values. Conversely, in the sleep dataset, Φ values were observed to be roughly grouped into three levels. The systems that robustly showed the highest Φ were the VN and frontal set. Conversely, the global set and ECN showed low Φ values. The other systems were at intermediate levels. No relationship was found in which systems with higher Φ at baseline exhibited changes in Φ depending on the level of consciousness.

Figure 4.

Φ of baseline in the anesthesia and sleep datasets. ECN, executive control network; DAN, dorsal attention network; VAN, ventral attention network; SMN, somatomotor network; LN, limbic network; DMN, default mode network; VN, visual network.

Discussion

This study explored alterations in integrated information (Φ) across functional networks during anesthesia and sleep. Initially, we hypothesized that consciousness-related changes in Φ would be observed at the global level in both datasets. However, since such changes were not observed in the sleep dataset, we also examined Φ in local systems. In the anesthesia dataset, Φ at the global level, as well as in the VAN, DMN, and frontal systems, was correlated with transitions in consciousness levels. In contrast, in the sleep dataset, only Φ in the occipital system showed a strong association with consciousness level. These results are consistent with the predictions of IIT and suggest that the loss of consciousness induced by anesthesia and sleep involves different neural mechanisms.

In exploring consciousness, IIT has become a key viewpoint. Rooted in phenomenology, IIT uses the Φ metric to describe the quality of conscious experience and measure the level of consciousness of a system (Tononi 2004, Tononi et al. 2016). The application of Φ to neuroimaging data has progressed (Nemirovsky et al. 2023), but the current literature is largely theoretical, and empirical applications of the latest IIT version (4.0) are lacking (Albantakis et al. 2023). In the present study, we examined changes in Φ based on IIT 4.0 and found that those within global or local systems were correlated to the level of consciousness; it decreased while transitioning from wakefulness to sedation or deep sleep, followed by an increase during recovery or REM. This indicates that the global or local systems generate information that cannot be reduced to individual elements, and this diminishes with the loss of consciousness. While IIT originally emphasizes the relationship between consciousness and integrated information at the micro-level systems composed of irreducible elements like neurons (Tononi et al. 2016), our findings indicate that, even at the macro level involving large-scale functional networks, integrated information remains strongly associated with consciousness.

Nemirovsky et al. (2023) applied the previous version of Φ (IIT 3.0) to individual functional networks using the same anesthesia dataset that we utilized. The effects of anesthesia varied across the functional networks, and the anesthesia-related pattern was most clearly observed in the ECN and DAN. Taken together with our findings, this suggests that integrated information is generated both within and between individual functional networks. Supporting this, a study utilizing LFPs of the fly brain also reported a reduction in Φ under anesthesia, irrespective of the physical distance between the elements (channels) constituting the system (Leung et al. 2021). Changes in Φ associated with consciousness may occur at any hierarchical level of the brain, and a theoretical study shows that Φ at the macro level can be larger than Φ at the micro level (Hoel et al. 2016). Another fMRI approach using energy landscape or macroscale gradients argues that the high-dimensional complexity and efficient hierarchical processing support consciousness (Galadí et al. 2021, Huang et al. 2023, Li et al. 2023). Since the IIT asserts that the physical substrate of consciousness is a set of elements at a particular spatiotemporal granularity (Tononi et al. 2016), it is necessary to verify Φ at a hierarchically defined granularity. Such analysis can contribute to elucidating the nested structure of consciousness (Northoff and Huang 2017, Northoff and Lamme 2020).

This study can also be seen as manipulating granularity through the use of multiple atlases (global level, Yeo’s 7-networks; intra-network level, 7-network split; inter-network atlas, 17-networks atlases). In the sleep dataset, the systems of the global and intra-network levels did not demonstrate changes in Φ corresponding to the sleep stages. However, the inter-network system in the posterior cortex showed the sleep stage-dependent changes in Φ (Fig. 3l). These results suggest that the granularity of the global level is too coarse, or the sleep stage-dependent changes in Φ are localized, relatively small, and obscured by averaging. In contrast, the systems of the multiple levels showed the sedation-dependent changes in Φ in the anesthesia dataset. Anesthesia inhibits information integration at higher levels of the hierarchy of the global brain functional network and may lead to a deeper loss of consciousness than sleep. The mechanisms of sleep and anesthesia-induced loss of consciousness differ at various levels (Bonhomme et al. 2011, Mashour and Pal 2012). The level of hierarchy at which the change in Φ occurs due to loss of consciousness during sleep and anesthesia may be rigorously determined by manipulating the granularity of the system more precisely.

Our results provide evidence that the neural dynamics during loss of consciousness due to anesthesia and sleep are different, despite the neurobiological and molecular similarity (Jung and Kim 2022). This important finding is strongly supported by research using intracranial EEG in patients with epilepsy (Zelmann et al. 2023). In their study, Zelmann et al. (2023) measured the spatiotemporal complexity (perturbational complexity index, Casali et al. 2013) in response to direct electrical stimulation. This complexity was generally reduced during both propofol anesthesia and sleep; however, considering the relative distribution, the complexity in the prefrontal cortex was markedly reduced during anesthesia, while such changes were not observed during sleep. In line with this finding, a research using functional gradient mapping approaches has shown that the effects of propofol on functional connectivity are prominent in associative areas rather than in sensory or motor areas (Huang et al. 2024). In addition, a study examining the cross-coupling of alpha and delta waves has reported that the posterior cortex is first affected by loss of consciousness caused by propofol and that the effect extends to the anterior cortex as anesthesia deepens (Stephen et al. 2020). These studies show that the effects of propofol are quite extensive in the brain. In contrast, sleep is a spatiotemporally localized phenomenon (Song and Tagliazucchi 2020). When an individual is in deep non-REM sleep, specific regions of the brain exhibit wake-like activity, accompanied by conscious experiences related to local activation (Siclari et al. 2017).

Several previous studies measuring fMRI during sleep and anesthesia, as well as brain injury, have reported alterations in networks spanning the frontoparietal region associated with the loss of consciousness (Boveroux et al. 2010, Sämann et al. 2011, Jordan et al. 2013, Uehara et al. 2014, Watanabe et al. 2014, Huang et al. 2016, Martínez et al. 2020, Miao et al. 2023, Luppi et al. 2024). Furthermore, we have reported that the frontoparietal network is altered during sleep based on the measures of empirical integrated information (Onoda and Akama 2023, 2024). In addition, in the present study, the Φ in the frontal set also demonstrated changes linked to the sedation stage. These findings indicate that the decreased Φ of the ECN, or the system that includes the ECN, is associated with the loss of consciousness.

Luppi et al. have further developed the workspace of the GNWT and proposed the concept of a synergistic global workspace (Luppi et al. 2022, 2024). This workspace processes synergistic information that is available only when multiple pieces of information are considered together. It consists of gateway regions that collect synergistic information from specialized modules throughout the brain and broadcaster regions that integrate and widely distribute the information. The synergistic workspace is formed by the combination of the ECN and the DMN (Luppi et al. 2022), with the DMN corresponding to the gateway region and the ECN corresponding to the broadcaster region (Luppi et al. 2024). Almost all areas that showed consistent reductions in ΦR during loss of consciousness were contained in the global synergistic workspace (Luppi et al. 2024). This finding is consistent with the findings of the present study, which indicated variations in the integrated information Φ with the level of consciousness in the balanced set including the core components of the ECN and DMN (Fig. 2j).

Although GNWT and IIT are frequently discussed in opposition to each other, an alternative perspective views them as part of a broader theoretical family. Baars et al. (2021) suggest that the workspace responsible for the integration and broadcasting of information is dynamically structured within a more extensive thalamocortical system, rather than being a limited fixed area like the ECN. If the highly integrated products within this system are regarded as the substrate of consciousness, this view aligns with IIT and related theories (Baars et al. 2021). Integration and broadcasting can be evaluated based on graph theory (Wajnerman Paz 2022, Luppi et al. 2024); however, explicit criteria or procedures that distinctly separate the global workspace from the rest based on this evaluation are lacking. This stands in contrast to the complex in IIT, which possesses a mathematically unambiguous framework. If GNWT can establish a mathematical definition for theoretical constructs such as the global workspace, a rigorous comparison with IIT would become feasible. Despite the establishment of adversarial collaborations between proponents of these two theories (Melloni et al. 2023) and proposals for a comprehensive conceptual framework that encompasses both theories (Safron 2020), conducting rigorous comparisons remains a challenging endeavor.

Another important result in this study was the finding of changes in Φ of the occipital set depending on the level of consciousness, which was apparent in the sleep dataset (Fig. 3l). This result suggests that Φ in localized regions in the posterior cortex is associated with the level of consciousness during sleep, reinforcing IIT. In particular, Φ of the occipital set in the REM was higher than that in the N3 stage, suggesting that a relative enhancement of information integration occurs in the posterior cortex even in the absence of sensory and motor outputs. This is consistent with the findings of Miyauchi et al. (2009) that reported activity in areas including the visual cortex during REM sleep. The idea that a system restricted to sensory regions could contribute to the emergence of consciousness is also predicted by RPT. RPT emphasizes recurrent processing between elements, whereas IIT emphasizes integration among elements that cannot be reduced to recurrent processing. Proponents of the RPT argue that the recurrent processing in the sensory cortex is sufficient to mediate phenomenal and experiential features of consciousness (Lamme 2006, Hurme et al. 2017). RPT was introduced primarily to explain some findings on the transition from the unconscious to conscious vision (Lamme 2000). Feedforward activation in the VN is considered insufficient for conscious experience, and recurrent processing is required (Lamme et al. 1998, Fahrenfort et al. 2007, Ro 2010), indicating that recurrent processing is essential for the perceptual organization or combination of spatially distant features (Lamme 1995, Zipser et al. 1996). This perceptual organization and combination is considered sufficient for conscious experience because it accounts for the unity or wholeness, an important feature of conscious perception (Northoff and Lamme 2020). In this context, research that directly compares recurrent processing and integrated information in the posterior regions is warranted.

There are some limitations to this study. One limitation is that the number of elements in the system is still limited. The computational load increases exponentially with increasing number of elements. Due to the computational burden, only coarse selections can be performed. A solution to this includes the development of algorithms to reduce the computational load. On the contrary, consciousness may be supported by efficient hierarchical processing constrained along low-dimensional macroscale gradients (Huang et al. 2023, Li et al. 2023). As already mentioned, the internal causal power of the system may have a greater influence at the macro rather than at the micro level (Hoel et al. 2016). Therefore, the key issue may lie not in the number of elements but in how to select the most essential few. Another limitation is that the analysis in this study was based on discrete systems, even though the brain is a continuous dynamic system at the macro level. In addition to the several Φ proxy metrics being proposed (Oizumi et al. 2016a, 2016b, Mediano et al. 2021) in recent years, the integrated information has been naturally extended to continuous dynamic systems through the energy landscape (Esteban et al. 2018, Kalita et al. 2019). Research using these approaches should also be accelerated.

Conclusion

This study provides empirical evidence supporting IIT by demonstrating that the Φ decreases with the loss of consciousness during both anesthesia and natural sleep. Our results underscore the importance of integrated information at the macro level, reinforcing the notion that consciousness is sustained by the interaction of large-scale functional networks. Moreover, we found that the Φ decreases during anesthesia-induced unconsciousness at both global and local levels, while the reduction in Φ is more localized during sleep. This especially applies to the posterior brain regions, suggesting different processes of consciousness alteration between anesthesia and sleep.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Keiichi Onoda, Department of Psychology, Otemon Gakuin University, 2-1-15, Nishiai, Ibaraki, Osaka 567-8502, Japan.

Satoru Miyauchi, Department of Physiology, Kansai Medical University, 2-5-1, Shinmachi, Hirakata, Osaka 573-1010, Japan.

Shigeyuki Kan, Research Organization of Science and Technology, Ritsumeikan University, 1-1-1, Noji-higashi, Kusatsu, Shiga 525-8577, Japan.

Hiroyuki Akama, School of Medicine, University of Toyama, 2630, Sugitani, Toyama 930-0152, Japan.

Author contributions

Keiichi Onoda (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing—original draft [lead]), Satoru Miyauchi (Supervision, Writing—review & editing [equal]), Shigeyuki Kan (Data curation, Writing—review & editing [equal]), and Hiroyuki Akama (Supervision, Writing—review & editing [equal])

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23K03022.

Data availability

The raw data of the anesthesia dataset used in this study are available on Openneuro.org (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds003171). The raw data of the sleep dataset are available upon request. The Φ data for the statistical analyses are available at https://github.com/onodak1/IIT4_analysis.

References

- Albantakis L, Barbosa L, Findlay G et al. Integrated information theory (IIT) 4.0: formulating the properties of phenomenal existence in physical terms. PLoS Comput Biol 2023;19:e1011465. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkire MT, Hudetz AG, Tononi G. Consciousness and anesthesia. Science 2008;322:876–80. 10.1126/science.1149213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baars BJ, Geld N, Kozma R. Global workspace theory (GWT) and prefrontal cortex: recent developments. Front Psychol 2021;12:749868. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.749868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AB, Seth AK. Practical measures of integrated information for time-series data. PLoS Comput Biol 2011;7:e1001052. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boly M, Massimini M, Tsuchiya N et al. Are the neural correlates of consciousness in the front or in the back of the cerebral cortex? Clinical and neuroimaging evidence. J Neurosci 2017;37:9603–13. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3218-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme V, Boveroux P, Vanhaudenhuyse A et al. Linking sleep and general anesthesia mechanisms: this is no walkover. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg 2011;62:161–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveroux P, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Bruno M-A et al. Breakdown of within- and between-network resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging connectivity during propofol-induced loss of consciousness. Anesthesiology 2010;113:1038–53. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f697f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali AG, Gosseries O, Rosanova M et al. A theoretically based index of consciousness independent of sensory processing and behavior. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:198ra105. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cofré R, Herzog R, Mediano PAM et al. Whole-brain models to explore altered states of consciousness from the bottom up. Brain Sci 2020;10:Article 9. 10.3390/brainsci10090626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola P, Allanson J, Naci L et al. The complexity of the stream of consciousness. Commun Biol 2022a;5:1173. 10.1038/s42003-022-04109-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola P, Spindler LRB, Luppi AI et al. Network dynamics scale with levels of awareness. NeuroImage 2022b;254:119128. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SARB, Barkhof F et al. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:13848–53. 10.1073/pnas.0601417103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Changeux J-P. Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron 2011;70:200–27. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellia F, Hendren J, Grasso M et al. Consciousness and the fallacy of misplaced objectivity. Neurosci Conscious 2021;7:1–12. 10.1093/nc/niab032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban FJ, Galadí JA, Langa JA et al. Informational structures: a dynamical system approach for integrated information. PLoS Comput Biol 2018;14:e1006154. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenfort JJ, Scholte HS, Lamme VA. Masking disrupts reentrant processing in human visual cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 2007;19:1488–97. 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.9.1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galadí JA, Silva Pereira S, Sanz Perl Y et al. Capturing the non-stationarity of whole-brain dynamics underlying human brain states. NeuroImage 2021;244:118551. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso M, Haun AM, Tononi G. Of maps and grids. Neurosci Conscious 2021;7:1–10. 10.1093/nc/niab022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldenmund P, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Sanders RD et al. Brain functional connectivity differentiates dexmedetomidine from propofol and natural sleep. Br J Anaesth 2017;119:674–84. 10.1093/bja/aex257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoel EP, Albantakis L, Marshall W et al. Can the macro beat the micro? Integrated information across spatiotemporal scales. Neurosci Conscious 2016;1–13. 10.1093/nc/niw012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Zhang J, Wu J et al. Decoupled temporal variability and signal synchronization of spontaneous brain activity in loss of consciousness: an fMRI study in anesthesia. NeuroImage 2016;124:693–703. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Mashour GA, Hudetz AG. Functional geometry of the cortex encodes dimensions of consciousness. Nat Commun 2023;14:72. 10.1038/s41467-022-35764-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Mashour GA, Hudetz AG. Propofol disrupts the functional core-matrix architecture of the thalamus in humans. Nat Commun 2024;15:7496. 10.1038/s41467-024-51837-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurme M, Koivisto M, Revonsuo A et al. Early processing in primary visual cortex is necessary for conscious and unconscious vision while late processing is necessary only for conscious vision in neurologically healthy humans. NeuroImage 2017;150:230–8. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan D, Ilg R, Riedl V et al. Simultaneous electroencephalographic and functional magnetic resonance imaging indicate impaired cortical top-down processing in association with anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 2013;119:1031–42. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a7ca92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Kim T. General anesthesia and sleep: like and unlike. Anesth Pain Med 2022;17:343–51. 10.17085/apm.22227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalita P, Langa JA, Soler-Toscano F. Informational structures and informational fields as a prototype for the description of postulates of the integrated information theory. Entropy 2019;21:493. 10.3390/e21050493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeepan S, Rudas J, Gomez F et al. Modeling an auditory stimulated brain under altered states of consciousness using the generalized Ising model. NeuroImage 2020;223:117367. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, Massimini M, Boly M et al. Neural correlates of consciousness: progress and problems. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016;17:307–21. 10.1038/nrn.2016.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme VA. The neurophysiology of figure-ground segregation in primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 1995;15:1605–15. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01605.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme VA. Neural mechanisms of visual awareness: a linking proposition. Brain and Mind 2000;1:385–406. 10.1023/A:1011569019782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme VA. Why visual attention and awareness are different. Trends Cogn Sci 2003;7:12–8. 10.1016/S1364-6613(02)00013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme VA. Towards a true neural stance on consciousness. Trends Cogn Sci 2006;10:494–501. 10.1016/j.tics.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme VA, Supèr H, Spekreijse H. Feedforward, horizontal, and feedback processing in the visual cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1998;8:529–35. 10.1016/S0959-4388(98)80042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung A, Cohen D, van Swinderen B et al. Integrated information structure collapses with anesthetic loss of conscious arousal in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Comput Biol 2021;17:e1008722. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Liu H, Lei X et al. Hierarchical fluctuation shapes a dynamic flow linked to states of consciousness. Nat Commun 2023;14:3238. 10.1038/s41467-023-38972-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 2008;453:869–78. 10.1038/nature06976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppi AI, Mediano PAM, Rosas FE et al. A synergistic core for human brain evolution and cognition. Nat Neurosci 2022;25:771–82. 10.1038/s41593-022-01070-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppi AI, Mediano PAM, Rosas FE et al. A synergistic workspace for human consciousness revealed by integrated information decomposition. eLife 2024;12:RP88173. 10.7554/eLife.88173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W, Findlay G, Albantakis L et al. Intrinsic units: identifying a system’s causal grain. bioRxiv 2024. 10.1101/2024.04.12.589163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez DE, Rudas J, Demertzi A et al. Reconfiguration of large-scale functional connectivity in patients with disorders of consciousness. Brain Behav 2020;10:e1476. 10.1002/brb3.1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashour GA, Pal D. Interfaces of sleep and anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2012;30:385–98. 10.1016/j.anclin.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashour GA, Roelfsema P, Changeux J-P et al. Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron 2020;105:776–98. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayner WGP, Marshall W, Albantakis L et al. PyPhi: a toolbox for integrated information theory. PLoS Comput Biol 2018;14:e1006343. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediano PAM, Seth AK, Barrett AB. Measuring integrated information: comparison of candidate measures in theory and simulation. Entropy 2018;21:17. 10.3390/e21010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediano PAM, Rosas FE, Luppi AI et al. Towards an extended taxonomy of information dynamics via integrated information decomposition. arXiv. 2021. 10.48550/arXiv.2109.13186 [DOI]

- Melloni L, Mudrik L, Pitts M et al. An adversarial collaboration protocol for testing contrasting predictions of global neuronal workspace and integrated information theory. PLoS One 2023;18:e0268577. 10.1371/journal.pone.0268577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J, Tantawi M, Alizadeh M et al. Characteristic dynamic functional connectivity during sevoflurane-induced general anesthesia. Sci Rep 2023;13:21014. 10.1038/s41598-023-43832-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi S, Misaki M, Kan S et al. Human brain activity time-locked to rapid eye movements during REM sleep. Exp Brain Res 2009;192:657–67. 10.1007/s00221-008-1579-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemirovsky IE, Popiel NJM, Rudas J et al. An implementation of integrated information theory in resting-state fMRI. Commun Biol 2023;6:692. 10.1038/s42003-023-05063-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Huang Z. How do the brain’s time and space mediate consciousness and its different dimensions? Temporo-spatial theory of consciousness (TTC). Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017;80:630–45. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Lamme VA. Neural signs and mechanisms of consciousness: is there a potential convergence of theories of consciousness in sight? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020;118:568–87. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Lee TM, Kay AR et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990;87:9868–72. 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oizumi M, Albantakis L, Tononi G. From the phenomenology to the mechanisms of consciousness: integrated information theory 3.0. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10:e1003588. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oizumi M, Amari S, Yanagawa T et al. Measuring integrated information from the decoding perspective. PLoS Comput Biol 2016a;12:e1004654. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oizumi M, Tsuchiya N, Amari S. Unified framework for information integration based on information geometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016b;113:14817–22. 10.1073/pnas.1603583113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoda K, Akama H. Complex of global functional network as the core of consciousness. Neurosci Res 2023;190:67–77. 10.1016/j.neures.2022.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoda K, Akama H. Exploring complex and integrated information during sleep. Neurosci Conscious 2024;1. 10.1093/nc/niae029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro T. What can TMS tell us about visual awareness? Cortex 2010;46:110–3. 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safron A. An integrated world modeling theory (IWMT) of consciousness: combining integrated information and global neuronal workspace theories with the free energy principle and active inference framework; toward solving the hard problem and characterizing agentic causation. Front Artif Intell 2020;3:30. 10.3389/frai.2020.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sämann PG, Wehrle R, Hoehn D et al. Development of the brain’s default mode network from wakefulness to slow wave sleep. Cereb Cortex 2011;21:2082–93. 10.1093/cercor/bhq295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siclari F, Baird B, Perogamvros L et al. The neural correlates of dreaming. Nat Neurosci 2017;20:872–8. 10.1038/nn.4545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider SB, Edlow BL. MRI in disorders of consciousness. Curr Opin Neurol 2020;33:676–83. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Tagliazucchi E. Linking the nature and functions of sleep: insights from multimodal imaging of the sleeping brain. Curr Opin Physiol 2020;15:29–36. 10.1016/j.cophys.2019.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen EP, Hotan GC, Pierce ET et al. Broadband slow-wave modulation in posterior and anterior cortex tracks distinct states of propofol-induced unconsciousness. Sci Rep 2020;10:13701. 10.1038/s41598-020-68756-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G. An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC Neurosci 2004;5:42. 10.1186/1471-2202-5-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tononi G, Boly M, Massimini M et al. Integrated information theory: from consciousness to its physical substrate. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016;17:450–61. 10.1038/nrn.2016.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara T, Yamasaki T, Okamoto T et al. Efficiency of a “small-world” brain network depends on consciousness level: a resting-state FMRI study. Cereb Cortex 2014;24:1529–39. 10.1093/cercor/bht004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajnerman Paz A. The global neuronal workspace as a broadcasting network. Netw Neurosci 2022;6:1186–204. 10.1162/netn_a_00261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Kan S, Koike T et al. Network-dependent modulation of brain activity during sleep. NeuroImage 2014;98:1–10. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BTT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 2011;106:1125–65. 10.1152/jn.00338.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelmann R, Paulk AC, Tian F et al. Differential cortical network engagement during states of un/consciousness in humans. Neuron 2023;111:3479–3495.e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipser K, Lamme VA, Schiller PH. Contextual modulation in primary visual cortex. J Neurosci 1996;16:7376–89. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07376.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of the anesthesia dataset used in this study are available on Openneuro.org (https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds003171). The raw data of the sleep dataset are available upon request. The Φ data for the statistical analyses are available at https://github.com/onodak1/IIT4_analysis.