Abstract

This study aims to explore the mechanism of artemisinin in treating osteoarthritis (OA) through bioinformatics and network pharmacology. The targets of artemisinin were obtained from databases such as TCMSP, and the disease targets of OA were screened from OMIM, TTD, DisGeNET, and GEO databases. The predicted targets of artemisinin were intersected with OA disease targets to obtain drug-disease common targets, which were visualized using a Venn diagram. Gene ontology (GO) analysis and KEGG functional analysis was performed on the 68 common target genes, and protein interaction network analysis was conducted to analyze their interaction relationships. The key genes were identified using the Cytohubba algorithm, followed by molecular docking with AutoDockTools 1.5.7 software and PyMOL software. Through database screening, 464 targets of artemisinin were identified, and 1654 OA target genes were screened from databases and GEO chip databases. The intersection of drug targets and disease targets yielded 68 drug-disease common targets. GO and KEGG analysis showed that these common target genes are mainly involved in oxidative stress response, bone formation, response to bacterial molecules, response to lipopolysaccharide, response to hypoxia, response to xenobiotic stimuli. Their molecular functions include regulation of transcription factor binding, ubiquitin-protein ligase activity, cytokine receptor binding. These common targets are enriched in 36 signaling pathways, including MAPK signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, NF-Kappa B signaling pathway, which are key regulatory pathways in the development of OA. Through protein interaction analysis and Cytohubba algorithm, 10 key genes were obtained. Furthermore, the top 5 key genes (BCL-2, IL-6, CASP3, HIF1A, TNF) were molecular-docked with artemisinin, and the results showed that these molecules could form stable binding through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction. Artemisinin may exert drug efficacy through multi-target and multi-pathway synergism in the treatment of OA. This study provides an effective theoretical basis for the treatment of OA with artemisinin.

Keywords: artemisinin, bioinformatics, molecular docking, network pharmacology, osteoarthritis

1. Introduction

osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic degenerative joint disease characterized by degeneration and injury of articular cartilage, often accompanied by joint pain and stiffness, which seriously affects patients’ quality of life.[1] With the aging of the global population and the aggravation of obesity, the incidence and disability rate of OA have increased year by year, and it has become one of the important public health problems facing the world.[2] Despite extensive research, the exact pathogenesis of OA has not been fully elucidated, thus hindering the development of effective treatments.[3]

Artemisinin, as an active ingredient extracted from the Chinese herb Artemisia annua L., has been widely used in anti-malaria treatment and has shown a wide range of biological activities. Recent studies have shown that artemisinin and its derivatives have also shown significant efficacy in the treatment of OA in osteoarthritis. Studies have shown that artemisinin can inhibit OA progression and cartilage degradation through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and inhibit inflammatory response by reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory factors such as interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).[4] It is suggested that Piezo1 plays a key role in the occurrence and progression of OA, and artemisinin can inhibit the activation of Piezo1, thereby alleviating the disease of OA.[5] In addition, artemisinin has also been shown to activate mitochondrial autophagy by reducing TNFSF11 expression and inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in cartilage, thus alleviating OA.[6] Artemisinin derivatives have also been shown to treat OA. For example, artesunate alleviates anterior cruciate ligament-induced osteoarthritis by inhibiting osteoclast generation, abnormal angiogenesis, and inhibiting inflammation.[7] The above studies have found possible related targets and pathways of artemisinin in the treatment of osteoarthritis through preliminary basic studies, but the current studies are still lacking, and the revealed targets and pathways are limited. The treatment of diseases by traditional Chinese medicine is often through multi-target and multi-pathway, and more studies are needed to confirm the regulatory mechanism of artemisinin treatment of OA from a comprehensive and multi-angle.

In recent years, with the development of bioinformatics, network pharmacology[8] and molecular docking technology,[9] researchers have begun to explore the application of these emerging technologies in disease treatment, with a view to discovering new mechanisms of action and therapeutic targets. The application of artemisinin in the treatment of OA provides a new perspective on the mechanism of action. Using network pharmacology and bioinformatics techniques, researchers were able to predict potential targets for artemisinin and reveal possible pathways of action through network analysis. Molecular docking technology provides an important theoretical basis for drug development and disease treatment by predicting the interactions between small molecules and targets. This study intends to use bioinformatics and pharmacological methods to predict the key action targets and pathways of artemisinin, and conduct molecular docking verification between artemisinin and key core proteins, in order to further reveal the mechanism of action of artemisinin in the treatment of OA, with a view to providing new treatment options for OA patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Artemisinin target screening

Using “artemisinin” as the keyword, targets related to artemisinin were identified through databases such as TCMSP (https://www.tcmsp-e.com/#/home), HERB (http://herb.ac.cn/), ChEMBL (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/), STITCH (http://stitch.embl.de), BindingDB (https://www.bindingdb.org/), DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/), PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), DGIdb (https://dgidb.org/), and TCMID (http://www.megabionet.org/tcmid/ the TCMID database is currently not available online, but it was accessible at the time of our study). The HERB database was used to retrieve “related gene targets” and “differentially expressed genes” modules. For ChEMBL database, a confidence threshold of 90% was set for activity screening. The UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) was utilized to standardize the gene names of the identified targets.

3. Identification of OA targets

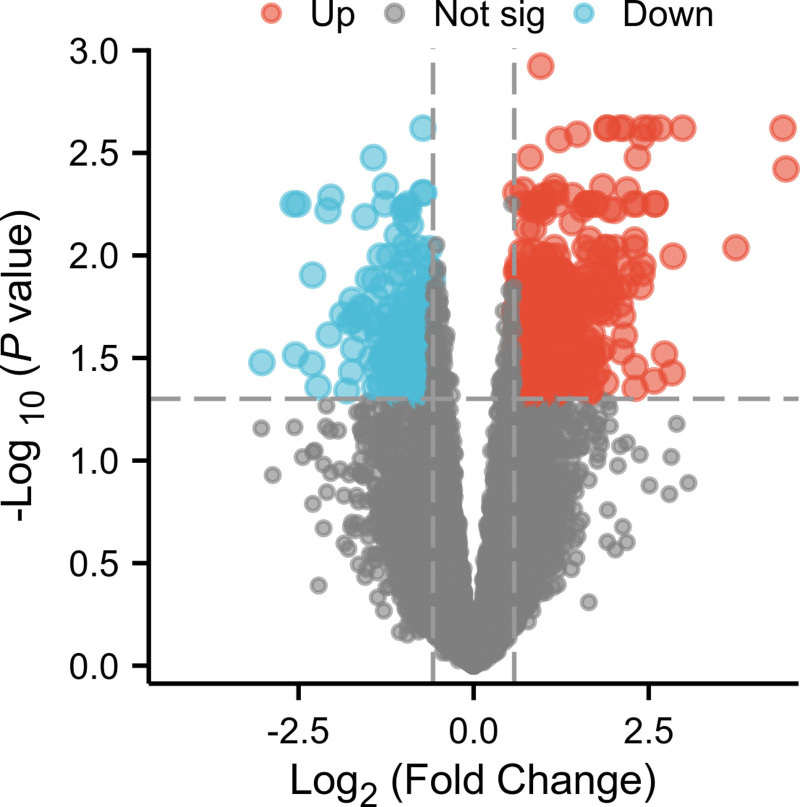

To identify disease targets for osteoarthritis (OA), a comprehensive search was conducted using the keywords “ostearthritic” and “osteoarthritis” across multiple databases including OMIM (https://omim.org/), TTD (https://db.idrblab.net/ttd/), DisGENET (https://www.disgenet.org/), and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/). For GeneCards, entries with a score of 1 or higher were selected. Subsequently, the results were standardized to gene names using the UniProt database, and duplicate gene entries were removed. The raw data of microarray dataset GSE55457, which includes 10 samples of OA synovial tissue and 10 samples of normal synovial tissue, was downloaded from the GEO database. After data normalization using the normalizeBetweenArrays function, differential expression analysis was performed using R limma with a threshold of |logFC| > 0.58 and P < .05 to select differentially expressed genes, followed by the creation of a volcano plot. The disease targets obtained from the 4 databases and the differentially expressed genes from the GEO database were combined to identify the disease targets for OA.

4. Screening for common drug-disease targets

Utilizing the “VennDiagram” package in R programming language, the predicted targets of artemisinin were intersected with the disease targets of OA. A Venn diagram was generated to obtain the common targets between the drug and the disease.

5. Gene enrichment analysis

The common targets obtained from the previous step were subjected to gene ontology (GO) analysis using R programming language to determine biological processes (BP), cellular components, and molecular functions (MF). Additionally, KEGG functional enrichment analysis was conducted with a correction threshold of P < .05 and q < 0.03. The results were visualized in the form of a bubble chart.

6. Constructing protein interaction networks and topological analysis

Input the drug-disease common targets into the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/), using a minimum interaction score > 0.4 as the screening criterion to obtain protein-protein interaction networks. Export the results as a tsv file and import it into Cytoscape 3.9.0 software to construct interaction network graphs. The color depth of each node represents the degree of connectivity of that node. Use the cytohubba plugin to screen for key genes based on the maximum modularity centrality (MCC) algorithm and obtain the top 5 critical genes.

7. Molecular docking

The top 5 targets with the highest degree values were selected based on PPI network. Extract the corresponding proteins from the RCSBPDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) and store them as PDB files. In the Pubchem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), the Pubchem ID and 3-dimensional chemical structure of artemisinin were found and saved as a mol2 file. Then, we used AutoDockTools 1.5.7 software to remove water, add hydrogens, truncate the ligand and receptor, and saved them as pdbqt files, then docked the ligand and receptor with AutoDockTools 1.5.7, analyzed the binding activity between artemisinin and the targets based on the docking results. The results showing negative values indicated that the common targets of OA have binding activity with artemisinin, in which smaller binding energies indicating stronger activity and better docking effects. Furthermore, the results were exported as PDBQT files and then converted to PDB files through OpenBabelGUI. Finally, the docking results were analyzed and visualized using PyMOL software.

8. Results

8.1. The drug-disease common targets of artemisinin and OA

From the database, 485 gene targets affected by artemisinin were screened, including 15 from TCMSP, 388 from HERB, 19 from chEMbl, 10 from STITCH, 7 from BindingDB, 1 from Drugbank, 36 from Pubchem, and 9 from DGIdb. After removing duplicates, a total of 464 target genes were obtained. Through keyword retrieval and GEO dataset analysis, a total of 1719 disease targets for osteoarthritis were screened, including 35 from OMIM, 26 from TTD, 30 from DisGENET, 1628 from Genecards, and 607 from GSE55457 (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, a total of 1654 target genes for osteoarthritis were obtained. The intersection of drug targets and disease targets yielded 68 drug-disease common targets (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The differentially expressed genes in the GSE55457 dataset was illustrated by volcano plot. Upregulated genes were indicated in red and downregulated genes in blue, and genes with no significant difference in expression were shown in gray.

Figure 2.

The artemisinin-osteoarthritis network was depicted and a total of 68 common targets were identified.

9. GO analysis and KEGG pathway analysis

The 68 common target genes were subjected to GO analysis and KEGG functional analysis, with the results outputted in the form of a bubble plot. The size of the bubbles represented the number of differential genes under each term, and the color of bubbles indicated the adjusted P-value. The GO analysis revealed that these common target genes were primarily involved in BP such as glandular formation, oxidative stress response, ossification, response to bacterial molecules, response to lipopolysaccharides, cellular response to chemical stress, response to hypoxia, and response to xenobiotic stimuli. They were mainly located in membrane microdomains, membrane rafts, transcription regulatory complexes, and vesicles. Their MF were predominantly concentrated on binding related to DNA-binding transcription activation, DNA-binding transcription factors, RNA polymerase II transcription factors that specifically bind DNA, ubiquitination protein ligases, cytokine receptors, glycosaminoglycans, and carboxylic acids (Fig. 3). KEGG pathway analysis identified that these common targets were enriched in 36 signaling pathways. Figure 4 illustrates the top 20 of these pathways, including key regulatory pathways such as the MAPK signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, and NF-Kappa B signaling pathway, which were almost involved in the occurrence and development of OA. Figure 5 shows the 36 signaling pathways and the key target genes involved in these pathways, among which MAPK1, RELA, NFKB1, IKBKB, CHUK, NRFBIA, TNF, FOS, IL-6, and others genes participated in more than 10 pathways.

Figure 3.

Bubble chart of GO analysis for disease-drug common target (top 10). GO = gene ontology.

Figure 4.

Bubble chart of KEGG analysis of disease-drug common target (top 20).

Figure 5.

Network diagrams of signal pathways enriched by common targets and their corresponding targets determined by KEGG enrichment analysis. The signal pathways were represented by diamond nodes, and the targets are represented by rectangular nodes. The darker the color of the rectangular node indicated the target in node involved in more signaling pathways.

10. Construction of protein interaction network and analysis of the key genes

The above common targets were imported into string database to analyze the existing protein interactions and the Cytoscape software was used to construct the interaction network. The obtained interaction network consisted of 64 nodes and 423 edges. The color of the node represents the degree of connectivity of the protein, that is, the more proteins interact with it, that is, the more connections, the darker the node color (Fig. 6). The key genes in the top 10 were calculated using Cytohubba algorithm, which were BCL-2, IL-6, CASP3, HIF1A, TNF, TP53, NFKB1, MMP9, FOS, and MYC, and their interaction networks were shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Drug-disease common target genes interaction network diagrams, the darker the node color represents the greater the number of interacting proteins.

Figure 7.

Key genes in drug-disease common targets were obtained using Cytohubba plugin MCC algorithm. The darker the node color, the higher the gene ranking. MCC = maximum modularity centrality.

11. Molecular docking verification

In this study, we used AutoDockTools 1.5.7 software to systematically docking the top 5 targets (BCL-2, IL-6, CASP3, HIF1A, TNF) with artemisinin in the PPI network screening value. Docking results showed that all the observed binding energies were lower than minus 5 kcal/mol (Fig. 8A), indicating a high affinity between the target proteins and artemisinin. Further analysis showed that hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic action played a key role in the formation of the complex. Artemisinin had stable interactions with BCL-2 amino acid residues ALA108, LEU96, PHE63, TYR67, SP70, and MET74 through hydrophobic action. Artemisinin bound stably to IL-6 amino acid residues SER176, GLU172, PHE74, MET67, and LYS66 through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic action. Artemisinin bound to PHE256, TRP206, and TYR204 amino acid residues of CASP3 through hydrophobic action. It bound to LYS46, THR74, PHE62, ALA73 amino acid residues of HIF1A through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic action. Stable binding with TNF amino acid residues ASN137, CYS77, THR79, and LYS90 were formed through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic action. These interactions could effectively anchor small molecules to protein sites and were a key step in their role in the treatment of OA.

Figure 8.

Molecular docking results. The binding enegeres (kcal/mol) of key targets and artemisinin were showed in bar chart (A). The binding sites (B–F).

12. Discussion

In this study, we delved into the multifaceted mechanism of artemisinin in treating OA by integrating bioinformatics, network pharmacology, and molecular docking approaches. Compared to prior studies on artemisinin’s antimalarial effects, this study innovatively explores its therapeutic mechanism in OA through a multi-omics approach. The identification of 68 drug-disease common targets and their enrichment in key OA-related signaling pathways represents a significant advancement. Our molecular docking verification of the top 5 targets (BCL-2, IL-6, CASP3, HIF1A, TNF) reveals novel binding modes not previously reported in the context of OA treatment. These findings suggest that artemisinin’s multi-target synergistic action in OA therapy differs fundamentally from its single-target antimalarial mechanism. This represents the first comprehensive mechanistic study of artemisinin in OA, offering a novel therapeutic perspective that extends beyond its traditional application.

The identification of 464 artemisinin targets and 1654 OA-related genes underscored the complexity of the molecular landscape involved in OA pathology and the broad action spectrum of artemisinin. The 68 common targets which were identified through intersection analysis represented a convergence point where artemisinin’s therapeutic effects may be exerted, highlighting its potential as a disease-modifying agent in OA. GO and KEGG analyses of the common target genes shed light on the BP and pathways that artemisinin may influence in OA. The enrichment in oxidative stress response, bone formation, and response to bacterial molecules suggests that artemisinin could modulate the inflammatory and degenerative aspects of OA. Oxidative stress is a pivotal mechanism implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of osteoarthritis, and numerous pharmacological agents and therapeutic technologies have been developed to mitigate osteoarthritis by targeting the inhibition of oxidative stress.[10,11] Synchronously, current researches indicated that artemisinin can attenuate the symptom of these diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,[12] chronic bacterial prostatitis,[13] retinal damage,[14] malaria,[15] oral squamous cell carcinoma,[16] and Parkinson disease[17] by inhibiting oxidative stress pathways. Our study is a newly supplementary study, which elucidated a regulatory mechanism that artemisinin treated OA specifically by inhibiting the oxidative stress pathway. In OA patients, the osteogenic differentiation function of osteoblasts were suppressed, which diminished their capacity to repair cartilage damage. Research demonstrated that under hypoxic or/and inflammatory conditions, 40 μM dose of artemisinin could significantly reverse the inhibitory effects of hypoxia and inflammation on the survival of dental pulp stem cells, reduce the rate of apoptosis and restore the osteogenic differentiation of these cells.[18] Furthermore, our study identified that artemisinin-OA common target genes involved in osteogenic differentiation, suggesting that artemisinin may reverse the compromised osteogenic differentiation ability, thereby laying the foundation for elucidating its therapeutic value in the treatment of OA. The involvement of these genes in signaling pathways such as MAPK, NF-κB, PI3K-Akt, and TNF is particularly noteworthy, as they are well-established in the regulation of inflammation, cell survival, bone resorption and immune responses – key factors in OA pathogenesis. As a derivative of artemisinin, dihydroartemisinin could mitigate the formation of osteoclasts and the resorption of bone by suppressing the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, thereby ameliorating OA.[19] Therapeutic agents that target the PI3K pathway could ameliorate OA triggered by inflammation through the modulation of macrophage polarization and the attenuation of inflammatory signaling cascades.[20] This aligns with the growing body of evidences which have suggested that multi-target drugs are more effective in treating complex diseases like OA that involving multiple dysregulated pathways.[21–23]

The protein-protein interaction network analysis, coupled with the Cytohubba algorithm, allowed us to pinpoint 10 key genes that may serve as the hub genes of the artemisinin-OA interaction network. This approach not only revealed the potential central players in the therapeutic mechanism of artemisinin but also highlighted the complexity of the signaling networks involved in OA. The top 5 genes – BCL-2, IL-6, CASP3, HIF1A, and TNF – are known to be critical in regulating apoptosis, inflammation, hypoxia, and immune responses, respectively, which are all central to OA progression.

The Bcl-2 family of proteins plays a central role in regulating apoptosis and cell survival, with Bcl-2 itself exhibiting antiapoptotic effects. In the pathogenesis of OA, changes in Bcl-2 expression are closely associated with chondrocyte apoptosis, influencing disease progression. Karaliotas et al[24] found through quantitative analysis that in patients with OA, the mRNA expression level of BAX tends to increase, while the ratio of Bcl-2/BAX significantly decreases, suggesting that the imbalance in Bcl-2 family protein expression in OA may participate in the occurrence and development of the disease by affecting cellular apoptotic pathways. Given the key role of Bcl-2 in regulating chondrocyte apoptosis, therapeutic strategies targeting Bcl-2 may have potential therapeutic value for OA. He DS et al[25] discovered that in OA chondrocytes, upregulating Sirt1 expression can increase Bcl-2 expression and decrease Bax (Bcl-2-associated X protein) expression, thereby inhibiting chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage matrix degradation. In recent years, research showed that artemisinin and its derivatives not only have antimalarial effects but also exhibit antitumor and anti-inflammatory activities, with their regulatory effects on the Bcl-2 family proteins gaining increasing attention concurrently. Artemisinin could increase the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins and decrease the levels of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, triggering apoptosis in tumor cells.[26] Artemisinin may reduce cell apoptosis and oxidative stress by activating the ERK1/2/CREB/BCL-2 signaling pathway, protecting neuronal cells, and thus can be used for the treatment of ischemic stroke.[27] Researchers developed a series of Bcl-2 inhibitors that combine the basic structural elements of artemisinin, and these compounds show enhanced biochemical activity and high selectivity against Bcl-2.[28] This suggests that the structure of artemisinin can be used to develop new Bcl-2 inhibitors, which may have potential value for the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as OA. This study, through network pharmacology and molecular docking, identified Bcl-2 as a key target common to both artemisinin and OA, with artemisinin showing a high affinity for Bcl-2, capable of stable binding through hydrophobic interactions with protein sites of Bcl-2. Therefore, we hypothesize that artemisinin may play a role in the treatment of OA by regulating Bcl-2 family proteins, particularly by inhibiting Bcl-2 expression and promoting cell apoptosis. These studies provide a scientific basis for the potential application of artemisinin in OA, although the specific mechanisms of artemisinin in OA still require further clinical research and experimental validation.

IL-6 is an inflammatory mediator that is upregulated in OA, and artemisinin can exert anti-inflammatory effects in OA by regulating the expression of IL-6. One study showed that artemisinin can inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and MMP-13.[4] By suppressing the expression of these inflammatory mediators, artemisinin reduces the inflammatory response, thus potentially serving as effective treatment strategy for OA.[4] Zhao et al[29] found that artesunate, one of artemisinin derivative, can alleviate cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis by blocking the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby reducing the production of inflammatory factors such as IL-6. Another artemisinin derivative, DC32, inhibited synovial inflammation in OA through the regulation of the Nrf2/NF-κB signaling pathway, significantly suppressing the transcription of IL-6, IL-1β, CXCL12, and CX3CL1, and reducing the production of inflammatory factors.[30] Therefore, artemisinin and its derivatives can regulate the expression of inflammatory factors such as IL-6 through various mechanisms, thus playing an anti-inflammatory role in OA. Our study hinted that IL-6 is a key target of artemisinin treatment, and molecular docking results showed that artemisinin has a high affinity for IL-6, potentially exerting direct anti-inflammatory effects by acting on IL-6.

CASP3 is a critical executor of apoptosis and plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including OA. The activation of CASP3 is closely associated with the apoptosis of chondrocytes, which leads to the destruction of the cartilage matrix and exacerbates the progression of OA. Molecules or drugs can modulate the apoptotic process of chondrocytes by promoting or inhibiting the expression of CASP3. Vitexin, an active ingredient in hawthorn leaf extracts, inhibited the expression of CASP3 induced by IL-1β, thereby protecting chondrocytes from apoptosis.[31] LncRNA BLACAT1 regulated the expression of CASP3 by modulating the miR-149-5p/HMGCR axis, affecting chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation.[32] MiR-186 modulated the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, thereby affecting the activity of CASP3, which also reveals the mechanism of CASP3 in OA.[33] CASP3 also interacted with other signaling pathways, such as the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB pathways, to collectively influence the progression of OA. UBE2M promoted the activity of CASP3 through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby promoting chondrocyte apoptosis.[34] Study has further confirmed that the use of CASP3 inhibitors, such as Z-DEVD-FMK, can protect chondrocytes from apoptosis and slow the progression of OA.[35] Due to the role of CASP3 in OA, therapeutic strategies targeting CASP3 may provide new avenues for the treatment of OA. Artemisinin and its derivatives may target and regulate CASP3, playing a therapeutic role in various diseases, including lung cancer and ischemic stroke, as well as in OA. Artemisinin can induce apoptosis in the lung cancer cell line A549 by inducing the ROS-mediated amplification activation loop of caspase-9, -8, and -3.[36] Artemisinin activated the ERK1/2/CREB/BCL-2 signaling pathway, reduced apoptosis and oxidative stress in nerve cells, which can be used for the treatment of ischemic stroke.[37] Studies further found that artemisinin may work effectively in OA through a similar mechanism, by regulating CASP3 to reduce inflammation and cartilage destruction. Zhao [29] et al mentions that the artemisinin derivative Artesunate can inhibit the activation of CASP3 by blocking the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby reducing the production of inflammatory factors and alleviating cartilage destruction in OA. The artemisinin derivative DC32 inhibits synovial inflammation in OA by regulating the Nrf2/NF-κB signaling pathway and significantly suppressing the transcription of CASP3, reducing the production of inflammatory factors.[30] Our research suggests that CASP3 may be a principal molecular target for the therapeutic action of artemisinin. The molecular docking studies indicate that artemisinin forms a strong interaction with CASP3, likely through hydrophobic forces involving specific amino acid residues. This high affinity binding to CASP3 implies that artemisinin could be mediating its anti-inflammatory effects by directly targeting this enzyme.

Current research indicated that HIF1A was involved in the pathophysiological processes of OA development through participation in cartilage degradation, chondrocyte apoptosis, and inflammatory responses. The expression of HIF1A in chondrocytes is increased in OA patients and associated with cartilage degeneration. Studies found that HIF1A not only regulated cartilage formation at the genetic level by modulating SOX9 expression, but also involved in the regulation of autophagy and apoptosis. It protected articular cartilage by promoting chondrocyte phenotype, maintaining chondrocyte vitality, and supporting metabolic adaptation to hypoxic environments.[38] The activation of HIF1A was also associated with synovial inflammation.[39] Therefore, HIF1A plays a significant role in the occurrence and development of OA, involving multiple aspects such as cartilage degeneration, inflammatory responses, and cellular apoptosis, and may serve as a potential target for OA treatment. Preliminary therapeutic efficacy of artemisinin in tumors had been identified by affecting HIF1A activity.[40–42] Artemisinin and its derivatives showed significant potential in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, with the co-release of artemisinin and dexamethasone inhibiting the HIF-1α/NF-κB cascade, thereby regulating ROS scavenging and macrophage repolarization, significantly alleviating inflammatory cell infiltration and cartilage damage in arthritic rat models.[43] DHA, the dihydro derivative of artemisinin inhibits the expression of NLRP3 via the HIF-1α and JAK3/STAT3 signaling pathways, thereby alleviating inflammation and arthritis symptoms in collagen-induced arthritis mice.[44] Artemisinin-derived artesunate inhibited the expression of angiogenic factors in human rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by suppressing PI3 kinase/Akt activation, providing new evidence for the potential of artesunate as a low-cost drug in RA treatment.[45] Our research suggested that HIF1A may be one of the key targets of artemisinin action in OA, with molecular docking results preliminarily confirming the binding of artemisinin to HIF1A through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. In summary, artemisinin may have a potential impact on the treatment of osteoarthritis by regulating the activity and expression of HIF1A. However, definitive conclusions require further research for elucidation.

TNF-α is a crucial pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of OA. Studies have indicated that the expression of TNF-α was significantly increased in the synovial fluid and cartilage of OA patients and was closely associated with cartilage degradation and inflammatory responses.[46] Recent research found that artemisinin can inhibit the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β, reduce the release of inflammatory factors and thereby alleviate joint inflammation.[6] Through network pharmacology and molecular docking analysis, we discovered that artemisinin can bind to TNF-α, inhibiting the activity of TNF-α and playing a significant role in the treatment of OA. Future studies are urgently needed that focusing on further explore the specific mechanism and clinical application potential of artemisinin in inhibiting the progression of TNF-α-mediated OA.

Molecular docking, a computational technique widely employed in drug discovery, allows for the prediction of binding modes and affinities between small molecules and target proteins. In this study, molecular docking using AutoDockTools 1.5.7 provided valuable insights into the interactions between artemisinin and its potential targets in OA treatment. The docking results revealed that artemisinin exhibited strong binding affinities for all the top 5 targets (BCL-2, IL-6, CASP3, HIF1A, TNF) with binding energies lower than −5 kcal/mol. These findings suggest that artemisinin could potentially modulate the activity of these proteins, which are implicated in OA pathogenesis. However, it is important to note that molecular docking predictions, although powerful, require experimental validation to confirm their biological relevance. Therefore, our future work will focus on conducting in vitro and in vivo experiments to validate these key targets and the interactions with artemisinin.

13. Conclusion

In summary, artemisinin is a multi-target natural product, and its potential in OA treatment is gradually being recognized. However, this study has some limitations and future studies are needed to further explore the mechanism of action of artemisinin and validate its efficacy and safety through clinical trials, with a view to providing new treatment options for OA patients.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yifang Zhu.

Funding acquisition: Yifang Zhu.

Investigation: Qin Wang.

Methodology: Min Li.

Supervision: Wenjing Yu.

Writing – original draft: Dan Zhao.

Writing – review & editing: Yifang Zhu.

Abbreviations:

- Bax

- Bcl-2-associated X protein

- BP

- biological processes

- CC

- cellular components

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- GO

- gene ontology

- IL-1β

- interleukin 1β

- MCC

- maximum modularity centrality

- MF

- molecular functions

- OA

- osteoarthritis

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor α

This study was funded by Research program of Chengdu Health Commission (2023308, to YZ).

Ethical approval was not necessary for this study, which was confined to the analysis of publicly accessible, de-identified datasets. Compliance with the usage terms of the databases was maintained throughout the data access process. The research did not involve any handling of private or sensitive personal information.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

How to cite this article: Zhu Y, Li M, Wang Q, Yu W, Zhao D. Investigating the mechanism of artemisinin in treating osteoarthritis based on bioinformatics, network pharmacology, and molecular docking. Medicine 2025;104:35(e42281).

Contributor Information

Min Li, Email: 415289633@qq.com.

Qin Wang, Email: 314306221@qq.com.

Wenjing Yu, Email: 76933738@qq.com.

Dan Zhao, Email: 596443815@qq.com.

References

- [1].Zhou F, Han X, Wang L, et al. Associations of osteoclastogenesis and nerve growth in subchondral bone marrow lesions with clinical symptoms in knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Translat. 2021;32:69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lafont JE, Moustaghfir S, Durand AL, Mallein-Gerin F. The epigenetic players and the chromatin marks involved in the articular cartilage during osteoarthritis. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang H, Yuan T, Wang Y, et al. Osteoclasts and osteoarthritis: novel intervention targets and therapeutic potentials during aging. Aging Cell. 2024;23:e14092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhong G, Liang R, Yao J, et al. Artemisinin ameliorates osteoarthritis by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51:2575–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gan D, Tao C, Jin X, et al. Piezo1 activation accelerates osteoarthritis progression and the targeted therapy effect of artemisinin. J Adv Res. 2024;62:105–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li J, Jiang M, Yu Z, et al. Artemisinin relieves osteoarthritis by activating mitochondrial autophagy through reducing TNFSF11 expression and inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in cartilage. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022;27:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhao C, Liu Q, Wang K. Artesunate attenuates ACLT-induced osteoarthritis by suppressing osteoclastogenesis and aberrant angiogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liao JH, He Q, Huang ZW, et al. Network pharmacology-based strategy to investigate the mechanisms of artemisinin in treating primary Sjögren’s syndrome. BMC Immunol. 2024;25:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dai L, He Y, Zheng S, Tang J, Fu L, Zhao L. Uncovering the mechanisms of cinnamic acid treating diabetic nephropathy based on network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental validation [published online ahead of print February 9, 2024]. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. doi: 10.2174/0115734099286283240130115111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Erten F, Ozdemir O, Tokmak M, et al. Novel formulations ameliorate osteoarthritis in rats by inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12:7896–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li B, Jiang T, Wang J, et al. Cuprorivaite microspheres inhibit cuproptosis and oxidative stress in osteoarthritis via Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mater Today Bio. 2024;29:101300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ahmad T, Kadam P, Bhiyani G, et al. Artemisia pallens W. attenuates inflammation and oxidative stress in freund’s complete adjuvant-induced rheumatoid arthritis in wistar rats. Diseases. 2024;12:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li S, Li Y, Su X, et al. Dihydroartemisinin promoted bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell homing and suppressed inflammation and oxidative stress against prostate injury in chronic bacterial prostatitis mice model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:1829736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yan F, Wang H, Gao Y, Xu J, Zheng W. Artemisinin protects retinal neuronal cells against oxidative stress and restores rat retinal physiological function from light exposed damage. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:1713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pires CV, Cassandra D, Xu S, Laleu B, Burrows JN, Adams JH. Oxidative stress changes the effectiveness of artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. mBio. 2024;15:e0316923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shi S, Luo H, Ji Y, et al. Repurposing dihydroartemisinin to combat oral squamous cell carcinoma, associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2023;2023:9595201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yan J, Ma H, Lai X, et al. Artemisinin attenuated oxidative stress and apoptosis by inhibiting autophagy in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. J Biol Res (Thessalon). 2021;28:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hu HM, Mao MH, Hu YH, et al. Artemisinin protects DPSC from hypoxia and TNF-α mediated osteogenesis impairments through CA9 and Wnt signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2021;277:119471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ding D, Yan J, Feng G, Zhou Y, Ma L, Jin Q. Dihydroartemisinin attenuates osteoclast formation and bone resorption via inhibiting the NF‑κB, MAPK and NFATc1 signaling pathways and alleviates osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Med. 2022;49:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guo Y, Wang P, Hu B, Wang L, Zhang Y, Wang J. Kongensin A targeting PI3K attenuates inflammation-induced osteoarthritis by modulating macrophage polarization and alleviating inflammatory signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142:112948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hu H, Song X, Li Y, et al. Emodin protects knee joint cartilage in rats through anti-matrix degradation pathway: an in vitro and in vivo study. Life Sci. 2021;269:119001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ma T, Ma Y, Yu Y, et al. Emodin Attenuates the ECM degradation and oxidative stress of chondrocytes through the Nrf2/NQO1/HO-1 pathway to ameliorate rat osteoarthritis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:5581346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zou X, Xu H, Qian W. The role and current research status of resveratrol in the treatment of osteoarthritis and its mechanisms: a narrative review. Drug Metab Rev. 2024;56:399–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Karaliotas GI, Mavridis K, Scorilas A, Babis GC. Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression levels of BCL2 and BAX genes in human osteoarthritis and normal articular cartilage: an investigation into their differential expression. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:4514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].He DS, Hu XJ, Yan YQ, Liu H. Underlying mechanism of Sirt1 on apoptosis and extracellular matrix degradation of osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:845–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hu CJ, Zhou L, Cai Y. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis of cervical cancer cells via upregulation of RKIP and downregulation of bcl-2. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:279–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Peng T, Li S, Liu L, et al. Artemisinin attenuated ischemic stroke induced cell apoptosis through activation of ERK1/2/CREB/BCL-2 signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:4578–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liu X, Zhang Y, Huang W, et al. Development of high potent and selective Bcl-2 inhibitors bearing the structural elements of natural product artemisinin. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;159:149–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhao C, Zhao L, Zhou Y, Feng Y, Li N, Wang K. Artesunate ameliorates osteoarthritis cartilage damage by updating MTA1 expression and promoting the transcriptional activation of LXA4 to suppress the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2023;32:1324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li YN, Fan ML, Liu HQ, et al. Dihydroartemisinin derivative DC32 inhibits inflammatory response in osteoarthritic synovium through regulating Nrf2/NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;74:105701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xie CL, Li JL, Xue EX, et al. Vitexin alleviates ER-stress-activated apoptosis and the related inflammation in chondrocytes and inhibits the degeneration of cartilage in rats. Food Funct. 2018;9:5740–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xu C, Jiang T, Ni S, et al. FSTL1 promotes nitric oxide-induced chondrocyte apoptosis via activating the SAPK/JNK/caspase3 signaling pathway. Gene. 2020;732:144339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lin Z, Tian XY, Huang XX, He L-L, Xu F. microRNA-186 inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway via SPP1 inhibits chondrocyte apoptosis in mice with osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:6042–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ba C, Ni X, Yu J, Zou G, Zhu H. Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 M promotes apoptosis in osteoarthritis chondrocytes via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;529:970–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yassin AM, AbuBakr HO, Abdelgalil AI, Khattab MS, El-Behairy AM, Gouda EM. COL2A1 and Caspase-3 as promising biomarkers for osteoarthritis prognosis in an equus asinus model. Biomolecules. 2020;10:354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gao W, Xiao F, Wang X, Chen T. Artemisinin induces A549 cell apoptosis dominantly via a reactive oxygen species-mediated amplification activation loop among caspase-9, -8 and -3. Apoptosis. 2013;18:1201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jiang M, Wu Y, Qi L, et al. Dihydroartemisinin mediating PKM2-caspase-8/3-GSDME axis for pyroptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chem Biol Interact. 2021;350:109704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang FJ, Luo W, Lei GH. Role of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82:144–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Du MD, He KY, Fan SQ, et al. The mechanism by which cyperus rotundus ameliorates osteoarthritis: a work based on network pharmacology. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:7893–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sun G, Zhao S, Fan Z, et al. CHSY1 promotes CD8+ T cell exhaustion through activation of succinate metabolism pathway leading to colorectal cancer liver metastasis based on CRISPR/Cas9 screening. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yang F, Zhang J, Zhao Z, et al. Artemisinin suppresses aerobic glycolysis in thyroid cancer cells by downregulating HIF-1a, which is increased by the XIST/miR-93/HIF-1a pathway. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Riganti C, Doublier S, Viarisio D, et al. Artemisinin induces doxorubicin resistance in human colon cancer cells via calcium-dependent activation of HIF-1alpha and P-glycoprotein overexpression. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1054–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li Y, Liang Q, Zhou L, et al. An ROS-responsive artesunate prodrug nanosystem co-delivers dexamethasone for rheumatoid arthritis treatment through the HIF-1α/NF-κB cascade regulation of ROS scavenging and macrophage repolarization. Acta Biomater. 2022;152:406–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang M, Wu D, Xu J, et al. Suppression of NLRP3 Inflammasome by Dihydroarteannuin via the HIF-1α and JAK3/STAT3 signaling pathway contributes to attenuation of collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:884881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].He Y, Fan J, Lin H, et al. The anti-malaria agent artesunate inhibits expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in human rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chou CH, Jain V, Gibson J, et al. Synovial cell cross-talk with cartilage plays a major role in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]