Abstract

Three different hydrophobins (Vmh1, Vmh2, and Vmh3) were isolated from monokaryotic and dikaryotic vegetative cultures of the edible fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Their corresponding genes have a number of introns different from those of other P. ostreatus hydrophobins previously described. Two genes (vmh1 and vmh2) were expressed only at the vegetative stage, whereas vmh3 expression was also found in the fruit bodies. Furthermore, the expression of the three hydrophobins varied significantly with culture time and nutritional conditions. The three genes were mapped in the genomic linkage map of P. ostreatus, and evidence is presented for the allelic nature of vmh2 and POH3 and for the different locations of the genes coding for the glycosylated hydrophobins Vmh3 and POH2. The glycosylated nature of Vmh3 and its expression during vegetative growth and in fruit bodies suggest that it should play a role in development similar to that proposed for SC3 in Schizophyllum commune.

Many hydrophobins have been described since SC1 and SC3 were found (16, 44), and their peculiar characteristics have beendescribed (15, 54). In the pathogenic fungus Cladosporium fulvum, six hydrophobin genes encode both class I (53) and class II (51) hydrophobins, and this seems to be the highest hydrophobin gene number in an individual fungus. At least four hydrophobin genes have been found in Schizophyllum commune, playing different roles during development (47): SC3 is expressed in monokaryons and dikaryons while the others are active only in dikaryons. For the edible mushroom Agaricus bisporus, various genes have also been identified coding for hydrophobins, ABH1/HypA and ABH2 in fruit bodies (12, 27) and ABH3 in vegetative mycelia (28), which probably perform different functions. Hydrophobin gene redundancy opens the question about their number and different physiological functions.

Gene disruption was used to verify the roles played by SC3 and SC4 in the formation of dikaryon aerial structures (47). The regulation of hydrophobin gene expression has been found to occur under the control of a complex set of factors, such as mating type in S. commune SC1 and SC3 (51) or nutrient availability and starvation in Neurospora crassa gene eas (9), Magnaporthe grisea MPG1 (26, 46), Trichoderma reesei hf1 and hfb2 (33), and C. fulvum HCF-1 to HCF-6 (43).

Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq. ex Fr) Kummer is a commercially important edible mushroom commonly known as the oyster mushroom. This fungus is industrially produced as human food, and it accounts for nearly a quarter of the world mushroom production (10). It is also used for the bioconversion of agricultural, industrial, and lignocellulose wastes (7, 37) as a source of enzymes and other chemicals for industrial and medical applications (18, 19, 30), as an agent for bioremediation (6), and as organic fertilizer (1). Several different P. ostreatus varieties are industrially produced. Commercial varieties florida and ostreatus differ in size, color, and temperature tolerance. Both varieties have been used in previous studies about the hydrophobins present in this fungus (4, 35). In this paper, we describe the purification of three new hydrophobins produced in the vegetative mycelium of P. ostreatus and analyze their genes and production in submerged culture under different nutritional conditions. The results indicate that P. ostreatus contains at least four different loci coding for vegetative-mycelium-specific hydrophobins whose expression is differentially regulated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

P. ostreatus var. florida (strain N001) (23, 36) and var. ostreatus (strain N007) were the dikaryotic strains used in this work. Basidiospores were collected, monokaryotic cultures were started, and mating types were determined as described elsewhere (23). Hybrid strain N015 was constructed by crossing a monokaryon derived from P. ostreatus N001 (MA005) with a compatible monokaryon derived from P. ostreatus N007 (MG001). Cultures of monokaryons or dikaryons were performed on solid Eger Medium (17) or in SMY (rich medium) (10 g of sucrose, 10 g of malt extract, 4 g of yeast extract, 1 liter of H2O; pH 5.6) (21) or minimal medium (MM) [0.05% (wt/vol) MgSO4, 0.005% (wt/vol) KH2PO4, 0.1% (wt/vol) K2HPO4, 0.15% (wt/vol) (NH4)2HPO4] for liquid cultures and were incubated at 24°C in the dark. Fruiting was induced by a cold shock (4°C, overnight) and subsequent incubation under photoperiod illumination (12 h of light, 12 h of darkness).

Hydrophobin purification and analysis.

Fruit body-specific and vegetative mycelium-specific hydrophobins were isolated according to the protocols described elsewhere (15). Hydrophobins were isolated from fruit bodies and vegetative mycelium homogenates as the fraction insoluble in a boiling solution containing 10 g of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) per liter in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Hydrophobins released into the medium in liquid cultures were aggregated by aeration and collected by centrifugation, and the subsequent extraction was performed as indicated above. The insoluble hydrophobin aggregates were dissociated by sonication in trifluoracetic acid at 0°C, and the acid was removed by flushing with nitrogen. Resuspension of trifluoracetic acid extracts in 60% of ethanol, dialysis, and lyophilization produced hydrophobins that could be analyzed by gel electrophoresis. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was done with 15% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels according to a method described by Laemmli (22). Proteins were revealed by using the silver staining method described by Merril (31). Protein molecular markers were obtained from Gibco BRL (Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom). Proteins were electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon P; Millipore Corporation) by the semidry transfer method (Multiphor II electrophoresis system; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). N-terminal sequencing and detection of carbohydrates were performed as described previously (36). For immunodetection of the proteins, the proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and detected by using an anti-SC3 antibody and a chemiluminescence system (Amersham).

Isolation, separation, and hybridization of DNA and RNA.

DNA was purified from 2 g of mycelium growing on liquid SMY by using the protocol described by Dellaporta et al. (13) with minor modifications (23). Total RNA was extracted using the procedure described by Wessels et al. (52). Southern and Northern blottings were prepared as described by Sambrook et al. (40). Hybridizations were performed at 65°C as described by Church and Gilbert (11) under high-stringency conditions.

cDNA synthesis and DNA sequencing.

cDNA from total vegetative mycelia mRNAs was synthesized using a 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit for reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR (Boehringer Mannheim), and a 5′/3′ RACE kit (Boehringer Mannheim) was used to determine the mRNA 5′end sequence. The fragments were cloned in pGEM-T vectors (Promega).

Genomic sequences were obtained by PCR using genomic DNA as template and specific oligonucleotides flanking the start and stop codons of the corresponding cDNA sequences (Tables 1 and 2). Hence, these genomic sequences include the gene exons and introns but not the 5′ and 3′ transcribed but untranslated regions present in the gene. PCR was carried out in a volume of 25 μl, and the cycling program started with a 4-min denaturation step at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min of annealing at 55°C, 1 min of extension at 72°C, and 1 min denaturation at 94°C. Double-stranded DNA fragments were sequenced in both directions with the T7 DNA polymersase kit from Pharmacia using the dideoxy chain termination method (41).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of cDNA PCR primer oligonucleotides used in this work

| cDNA | Oligonucleotide

|

Sequencea

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type | ||

| vmh1 | PFH2 | Degenerate | ACNGAYACNCCNWSNTGCWSNACNGG |

| PFH2.m1.1 | RACE | ATAGGGATACATCCTAAAGT | |

| PFH2.m1.2 | RACE | GTCATGCCAACCAAAGCAG | |

| vmh2 | PFH4 | Degenerate | TGYACNGARGCNGTNAA |

| PFH2.m5.1 | RACE | CAGCGACAATAAGACCGTTG | |

| PFH2.m5.2 | RACE | ACGGTGATAGGCGAGCACG | |

| vmh3 | PFH4.1 | RACE | AATGTTGACGAGACCATTG |

| PFH4.2 | RACE | CGGTAATATCACCGATCTT | |

All sequences are written 5′→3′. Degeneration code: N, A, C, G, or T; R, A or G; Y, C or T; S, C or G; W, A or T.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of PCR primer oligonucleotides used in this worka

| Gene | 5′ Gene-specific oligonucleotide | 3′ Gene-specific oligonucleotide |

|---|---|---|

| vmh1 | ATGCTCTTCAAACAAGCC | TCAGAGATTGATATTGATAG |

| vmh2 | ATGTTCTCCCGAGTTATCT | TCACAGGCCGATATTGA |

| vmh3 | ATGTTCTTCCAAACTACCAT | TTACAAGGCAACGTTGATG |

All sequences are written 5′→3′. The start and stop codons are underlined.

Chromosome-sized DNA preparations, PFGE separation of chromosomes, and linkage analysis.

Isolation of genomic DNA for chromosome separation by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as previously described (45). PFGE conditions were optimized for the separation of P. ostreatus chromosomes (23). For the genetic linkage mapping, a population consisting of haploid progeny of 80 monokaryons derived from P. ostreatus N001 was used (25). The analysis of linkage was performed following the methods described by Ritter et al. (38) and by Ritter and Salamini (39) using the MAPRF program (20; available upon request).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The genomic sequences of the vmh1, vmh2, and vmh3 alleles described in this paper have been deposited in the EMBL and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AJ420969 to AJ420974.

RESULTS

Vegetative-mycelium-specific hydrophobins and their genes.

The hydrophobins produced by the vegetative mycelium of P. ostreatus var. florida cultures carried out in SMY medium were extracted from monokaryons and dikaryons. A single 9-kDa protein band was obtained from monokaryons whereas two bands (9 and 17 kDa) were found in extracts from dikaryotic cultures (Fig. 1A). N-terminal sequencing yielded two sequences whose cysteine patterns corresponded to that of the hydrophobin protein family (49) (9-kDa protein present in monokaryons, TDTPSCSTGSLQCCSSVQAA; 17-kDa protein, TDSRRCTEAVKKCCNSS).

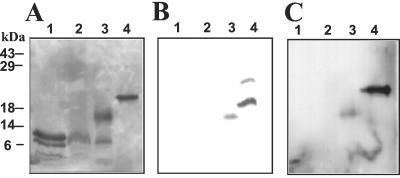

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of hydrophobins purified from P. ostreatus var. florida fruit bodies (lanes 1), monokaryotic vegetative mycelium (lanes 2), and dikaryotic vegetative mycelium (lanes 3) and SC3 hydrophobin purified from S. commune (lanes 4). (A) Silver staining; (B) staining with Schiff reagent; (C) immunoreaction with antibodies raised against S. commune hydrophobin SC3.

Some hydrophobins previously isolated from other fungi have been reported to be glysosylated (3). In order to determine whether this was the case with the hydrophobins purified from P. ostreatus vegetative mycelium, the SDS-PAGE-resolved proteins were blotted onto a PVDF membrane and stained with the Schiff reagent. A positive glycosylation signal was detected only in the 17-kDa protein (Fig. 1B). The sugar moiety involved in the glycosylation was studied using antibodies raised against the mature glycosylated hydrophobin SC3 from S. commune (3). A clear signal with the 17-kDa protein was observed (Fig. 1C), suggesting a glycosylation with sugars similar to those present in SC3, as the sequence of the two proteins had low similarity (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison between hydrophobin genes and alleles

| Gene or allele | % Sequence identitya

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vmh1-1 | vmh1-2 | vmh2-1 | vmh2-2 | POH3 | vmh3-1 | vmh3-2 | POH2 | SC3 | |

| vmh1-1 | 84 | 45 | 43 | 46 | 45 | 45 | 47 | 38 | |

| vmh1-2 | 82 | 42 | 40 | 43 | 38 | 38 | 43 | 39 | |

| vmh2-1 | 9 | 8 | 88 | 79 | 37 | 37 | 51 | 46 | |

| vmh2-2 | 7 | 8 | 94 | 79 | 36 | 36 | 45 | 44 | |

| POH3 | 20 | 19 | 76 | 76 | 41 | 41 | 52 | 48 | |

| vmh3-1 | 58 | 46 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 99 | 37 | 33 | |

| vmh3-2 | 57 | 46 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 99 | 37 | 33 | |

| POH2 | 19 | 19 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 8 | 8 | 47 | |

| SC3 | 29 | 29 | 35 | 33 | 35 | 31 | 29 | 39 | |

Values above the diagonal are the percents identity at the amino acid level, and values below the diagonal are the percents identity at the nucleotide level. Bold numbers highlight similarity values greater than 50%.

In order to determine the complete amino acid sequences of the hydrophobins detected, total RNA purified from monokaryotic and dikaryotic vegetative cultures was used separately as template for the synthesis of their corresponding cDNAs by using degenerate oligonucleotides coding for the N-terminal sequences (oligonucleotides PFH2 and PFH4 based on the sequences for the 9- and 17-kDa proteins, respectively; Table 1) and oligo(dT) as primers. The 5′ untranslated ends of the mRNAs were PCR amplified using oligonucleotides based on the cDNA sequences previously obtained as primers (RNA amplification of cDNA ends [RACE] oligonucleotides; Table 1). In the case of the experiment performed using RNA purified from monokaryons, two different individuals (M001 and M005) that differed in their mating types were used. For both monokaryons, RT-PCR yielded a single DNA band of ca. 450 bp that contained two different sequences in monokaryon M001 and another different one in monokaryon M005. The comparison of the nucleotide sequences revealed that two of them (deriving one from each of the monokaryons) were alleles of the same locus, whereas the third corresponded to another different gene. In the case of the experiment performed using mRNA from dikaryons as template, a single band was amplified that yielded only one type of sequence different from those previously amplified. All the sequences amplified in this experiment coded for proteins containing the eight conserved cysteine clusters spaced as previously described for fungal hydrophobins (51). In summary, transcripts of two different genes were identified in monokaryons (genes called vmh1 and vmh2) and a third one in the dikaryon (gene vmh3). In one case, the two alleles present in var. florida were detected (vmh2-1 and vmh2-2) (Table 3). The analysis of the sequences of the different genes was completed by determining the positions of introns within the coding sequences by means of a PCR amplification carried out on genomic DNA using as primers oligonucleotides covering the start and stop codons of each hydrophobin gene (Table 2). Table 4 summarizes the characteristics of the different hydrophobin genes and their products. The three genes coded for relatively small proteins that contained regions compatible with the signal peptides required for entering the export pathway.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of P. ostreatus var. florida vegetative-mycelium-specific hydrophobin genes and proteinsa

| Gene | 5′ UTR Position | Length (nt) of:

|

3′ UTR Position | Poly (A) signal Position | No. of amino acid residues | Molecular mass (kDa) | Signal peptide | Isoelectric point | Hydropathy index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Exons | Introns | |||||||||

| vmh1-1 | 33 | 351 | 266, 38, 47, | 53, 53 | 90 | 21 (AACAAA) | 116 | 11.67 | 28 | 4.78 | 0.64 |

| vmh1-2 | 351 | 266, 38, 47, | 55, 55, | 116 | 11.80 | 28 | 4.85 | 0.64 | |||

| vmh2-1 | 336 | 129, 76, 83, 48, | 56, 51, 53 | 119 | 20 (AATATA) | 111 | 11.22 | 24 | 5.77 | 0.83 | |

| vmh2-2 | 336 | 129, 76, 83, 48, | 56, 52, 53 | 111 | 11.20 | 24 | 5.77 | 0.78 | |||

| vmh3-1 | 80 | 327 | 242, 38, 47, | 53, 72 | 129 | 55 (AATAAT) | 108 | 11.15 | 23 | 7.48 | 0.11 |

| vmh3-2 | 327 | 242, 38, 47, | 52, 72 | 108 | 11.15 | 23 | 5.21 | 0.11 | |||

UTR, untranslated region; ORF, open reading frame; nt, nucleotide.

Expression of vegetative mycelium hydrophobin genes.

The expression of vmh1, vmh2, and vmh3 in fruit bodies and dikaryotic and monokaryotic mycelia was studied by Northern blot analysis. Two different monokaryons with complementary mating genotypes were analyzed, and no expression differences were found (data not shown). The expression of the three genes was studied in 8- to 10-day-old monokaryotic and dikaryotic cultures carried out in SMY and in P. ostreatus fruit bodies. Expression of vmh1 and vmh2 was detected only in vegetative mycelia, whereas vmh3 signal was observed in both vegetative and fruit bodies (Fig. 2). The hybridization signal intensity was slightly weaker in vmh1 than in vmh2 or vmh3 in monokaryons and dikaryons cultured under these conditions

FIG. 2.

Northern analysis showing vmh1, vmh2, and vmh3 expression at different development stages. Total RNA was purified from fruit bodies (lane 1), dikaryotic vegetative mycelium of monokaryon M001 (lane 2), and vegetative mycelium of monokaryons M001 (lane 3) and M005 (lane 4). Shown are hybridization using vmh1 cDNA (A), vmh2 cDNA (B), vmh3 cDNA (C), and RNA amount shown as ethidium bromide fluorescence (D). All the cDNA probes corresponded to the mature proteins (i.e., without leader peptide).

To study the dependence of hydrophobin expression on nutrient availability in submerged cultures, total RNA was purified from 8- to 10-day-old dikaryotic vegetative cultures performed in SMY and in minimal medium subjected to severe carbon source limitation. Under all tested conditions vmh2 was equally expressed, whereas vmh1 expression was higher in medium limited in carbon source than in complete media, and vmh3 expression was only detected in complete medium. These results were similar when the cultures were carried out in darkness or in dark/light conditions (data not shown).

Finally, the evolution of hydrophobin expression in mycelia growing on SMY was studied using RNA samples taken at various culture times (5, 7, 10, 15, and 20 days) (Fig. 3). Expression of the three hydrophobin genes was detected from the beginning of the experiment, although the levels of vmh1 and vmh2 expression became undetectable at longer culture times and vmh3 was expressed, albeit at a low level, in 20-day-old cultures.

FIG. 3.

Northern analysis showing time course of vmh1, vmh2, and vmh3 expression. Total RNA was purified from dikaryotic mycelia growing after 5 days (lane 1), 7 days (lane 2), 10 days (lane 3), 15 days (lane 4), and 20 days (lane 5) of vegetative growth. Shown are hybridizations with vmh1 cDNA (A), vmh2 cDNA (B), vmh3 cDNA (C), and P. ostreatus 5.8S rRNA as a control (D). All the cDNA probes corresponded to the mature proteins (i.e., without leader peptide).

A time course analysis of hydrophobin production and secretion was performed using liquid cultures of dikaryotic vegetative mycelium. The secreted hydrophobins were separately collected from mycelial cell walls and the culture filtrates after 5, 10, 15, and 20 days of cultivation. Two protein bands of 9 and 17 kDa could be detected in the cell wall extracts at all the points of the experiment (data not shown). This result was different when the culture filtrates were studied. In this case, only the 9-kDa protein band, corresponding to Vmh1 and Vmh2, was observed in all the samples whereas the 17-kDa protein (Vmh3) was detected after only 10 days of incubation (Fig. 4). The amount of hydrophobin released into the liquid medium increased as a function of culture time until a maximum was reached at 10 days (20.9 mg per 500 ml of culture) and a decrease was observed at 20 days of culture (15.4 mg per 500 ml).

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE of hydrophobins secreted to the medium by the dikaryotic mycelium of P. ostreatus N001 after 5 (lane 1), 10 (lane 2), 15 (lane 3), and 20 (lane 4) days of submerged culture.

The time course of hydrophobin secretion was also studied for cultures of monokaryons (protoclons PC9 and PC15) (23), although their slower growing rate made it necessary to reduce the number of time points under study. Hence, hydrophobins were extracted after 5 or 10 days (protoclon PC9) or 10 days (protoclon PC15) of culture. In all the cases, the 9-kDa protein band (Vmh1 and Vmh2) was detected and no Vmh3 could be detected under these conditions (data not shown).

Allelism analysis.

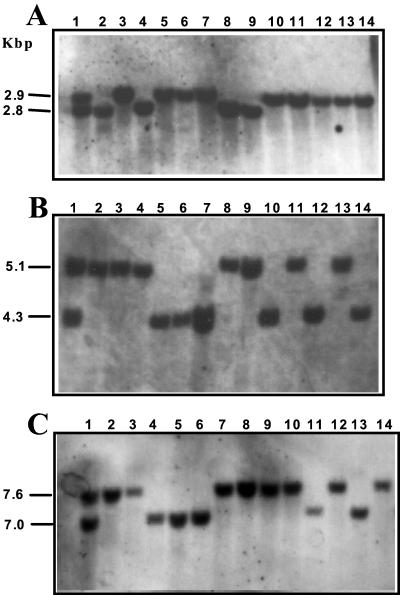

The hydrophobin genes described above were mapped on the genetic linkage map of P. ostreatus var. florida by using the procedure described by Larraya et al. (25). Figure 5 shows that segregation of vmh1, vmh2, and vmh3 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) alleles in a set of monokaryons analyzed using probes corresponding to their respective mature proteins revealed three single-copy unlinked genes. Linkage analysis as well as the hybridization of the three probes on PFGE-separated P. ostreatus chromosomes mapped vmh1 to chromosome I, vmh2 to chromosome XI, and vmh3 to chromosome X (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

RFLP analysis of vmh1, vmh2, and vmh3 genes. Shown are XhoI digestions (A and B) and EcoRI digestion (C) of DNA purified from dikaryotic strain N001 (lane 1) and from 13 monokaryons derived from it (lanes 2 to 14). DNA was probed with vmh1 cDNA (A), vmh2 cDNA (B), and vmh3 cDNA (C). All the cDNA probes corresponded to the mature proteins (i.e., without leader peptide).

In addition to the genes described in this paper, two other vegetative-mycelium-specific hydrophobins (POH2 and POH3) have been described for P. ostreatus var. ostreatus (4). In order to determine their map positions, probes corresponding to them were used for mapping as described above. POH3 cosegregated with vmh2, suggesting that they were alleles of the same gene. The probe corresponding to POH2 mapped to chromosome VII at the position defined by markers P91400 and P91500 (25) (data not shown).

To further confirm the allelic nature of vmh2 and POH3, an allelism test was performed as follows: compatible monokaryons from P. ostreatus var. florida (N001) and P. ostreatus var. ostreatus (N007) were mated to construct a new hybrid dikaryon (N015). Genomic DNA from dikaryon N015 and from 24 monokaryons randomly selected among its progeny was purified, digested, blotted, and analyzed with probes corresponding to vmh2 and POH3. Both probes lighted up the same RFLP bands on XhoI digestions of genomic DNA (data not shown). This analysis revealed that the RFLP allele provided by N007 had a size of 6.6 kbp and that provided by N001 was the 5.1 kbp that was previously observed in the segregation of N001 progeny (Fig. 5).

In the course of the experiments aimed to map vmh2-POH3, an additional DNA band was observed when probes containing the complete vmh2 cDNA sequence were used (Fig. 6). In Southern experiments carried out on PFGE-separated chromosomes of P. ostreatus N001 using the probe for the complete cDNA sequence of vmh2, a weak hybridization signal was observed on chromosome II besides the vmh2 strong signal on chromosome XI (data not shown). This gene was not studied further.

FIG. 6.

RFLP analysis of vmh2 and POH3 alleles. XhoI digestion of DNA purified from dikaryotic strain N001 (lane 1) and from 10 monokaryons derived from it (lanes 2 to 11) were probed with a cDNA sequence corresponding to the vmh2 gene (leader peptide plus mature protein). Identical results were obtained with the POH3 probe.

The expression of POH2 and POH3 genes in P. ostreatus N001 (var. florida) was studied using Northern blot analysis containing RNA purified from fruit bodies and dikaryotic and monokaryotic vegetative mycelia. POH3 expression was found in monokaryotic and dikaryotic vegetative mycelia and was not detected in fruit bodies. On the contrary, no POH2 expression was found in any of the var. florida samples studied (data no shown).

DISCUSSION

The family of genes coding for hydrophobins in the edible mushroom P. ostreatus is larger and more complex than expected. This suggests that the function of these proteins should not be merely structural but regulated by time or developmental stage. In fact, fruit body-specific hydrophobin Fbh1 is not expressed during vegetative growth and its expression is spatially regulated in the fruit body (36). Five different hydrophobins have been isolated from vegetative mycelia: Vmh1, Vmh2, and Vmh3 from P. ostreatus var. florida (this paper) and POH2 and POH3 from var. ostreatus (4). In this work, we investigated their primary structures and expression with the aim of contributing to the understanding of their different functions.

The genes coding for vegetative mycelium hydrophobins in P. ostreatus are single copy and show very little (if any) cross-hybridization in Southern experiments. The comparison of their nucleotide sequences (Table 3) suggests that they diverged a long time ago, although the differences between similarity scores at nucleotide and amino acid levels indicate that the these proteins' primary structures should be subjected to a considerable selective pressure that limits sequence drift.

The structure of hydrophobin genes suggests that they have suffered a process of intron losses and gains in the course of the evolution (Fig. 7). The genomic sequences of other hydrophobin genes have been described for other fungi, and the numbers and positions of their introns is rather conserved. Two introns have been identified in the genes coding for vegetative-mycelium-specific hydrophobins Le.hyd2 from Lentinula edodes (34) and CoH1 and CoH2 from Coprinus cinereus (5), whereas three introns have been reported for fruit body-specific hydrophobin genes fbh1 and POH1 from P. ostreatus (4) (M. Peñas, unpublished data), SC1 and SC4 from S. commune (50), Aa-Pri2 from Agrocybe agerita (42), Le.hyd1 from L. edodes (34), and fvh1 from Flammulina velutipes (2). In P. ostreatus, however, genes with two and three introns are expressed in vegetative mycelium and in fruit body. Moreover, comparison of P. ostreatus hydrophobin genes reveals the importance of the last intron and exon that are highly conserved in all of them, whereas the positions of the other introns vary in the different genes.

FIG. 7.

Schematic representation of the structures of the vegetative mycelium hydrophobin genes from of P. ostreatus. ▨, peptide signals; gray boxes, exons; _, introns; ▮, cysteines.

Most of the amino acid substitutions observed between the two alleles of the same gene correspond to conservative changes of apolar amino acids that cause nearly null effects in the predicted physicochemical properties of the proteins. The only exception to this is the substitution K64E (Vmh3-1 versus Vmh3-2) that produces a dramatic effect on the predicted isoelectric point (Table 4). Moreover, this is the unique amino acid change found in this otherwise highly conserved protein. The effect of this mutation, however, can be seen as more conservative, taking into account the polar nature of both amino acids and the overall low hydropathy index of Vmh3 proteins.

Analysis of glycosylation of the vegetative mycelium hydrophobins demonstrated that Vmh3 is the only one glycosylated in P. ostreatus var. florida. Hydrophobin glycosylation has also been reported to occur in SC3 from S. commune (3) and, more interestingly, in vegetative mycelium hydrophobin POH2 from P. ostreatus var. ostreatus (4). POH2 and SC3 hydrophobins contain a threonine-rich region at the N terminus of the mature protein that can be involved in O glycosylation (4, 14). No threonine- or serine-rich regions, however, are present in Vmh3, suggesting that the glycosylation site in this case should be different. A putative site for glycosylation in this protein can be the asparagine residue at position 37 that is predicted to be a possible substrate for N glycosylation (N-Xaa-S/T) (8). Irrespective of the glycosylation site, the sugar moieties added to the mature hydrophobin protein should be similar in Vmh3 and SC3, as antibodies raised against this last one were able to inmunodetect the hydrophobins from P. ostreatus var. florida and amino acid sequence similarity between the two proteins is low enough to discard the peptidic moiety as basis for this immunoreaction.

The redundancy of genes coding for vegetative mycelial hydrophobins could suggest that they should play different roles during the growth and differentiation. Three hydrophobin genes were expressed in both monokaryotic and dikaryotic cultures of P. ostreatus var. florida (vmh1, vmh2/POH3, and vmh3), and POH2 expression was not detected under our working conditions. Two of them (vmh1 and vmh2/POH3) are specific to vegetative mycelium, whereas vmh3 expression also occurs in fruit bodies. Northern experiments performed using a cDNA corresponding to mature Vmh2 as probe (Fig. 2 and 3) revealed a positive expression signal under all culture conditions tested, whereas expression of vmh1 and vmh3 varied according to nutrient availability. Currently, it is not possible to rule out the contribution of the gene identified as a 4.0-kbp band in Fig. 6 to the vmh2/POH3 expression signal; however, the lack of cross-hybridization between the different cDNAs (Fig. 5) and the lack of secondary genomic sequences hybridizing to the vmh2 probe corresponding to the mature protein suggest that this gene could be the principal contributor to the vmh2/POH3 expression signal. The expression level of hydrophobin genes decays with culture time. This decay is more pronounced in the case of vmh1 and vmh2, as vmh3 expression is detected in aged cultures. Hydrophobin secretion timing during culture provides additional information about the different roles of these proteins. In these experiments, Vmh1 and Vmh2 could not be resolved because of technical reasons. In the experiments performed with monokaryons, the Vmh1/Vmh2 fraction was recovered from the cell walls at different culture times whereas Vmh3 was not observed despite its mRNA being detected under these conditions. In dikaryotic cultures, the Vmh1/Vmh2 fraction was detected throughout the culture time, both as cell wall-associated protein, and released to the medium. Vmh3, however, was detected throughout the culture in cell wall extracts, but it could be mainly recovered from the culture medium at a specific time when the aerial development became prominent (day 10).

In this context, the function of Vmh3 seems to be similar to that of SC3: the promotion of aerial growth. As Vmh3 is also expressed in monokaryon that will not develop fruit body, the role of Vmh3 in fruit body formation should not be as specific as the role of Fbh1, a protein that is detected only in this developmental stage. This is also the case for S. commune SC3, whose expression is detected in both dikaryons and monokaryons (47). Finally, it should be kept in mind that this pattern of hydrophobin expression in submerged cultures can differ from solid fermentation processess as metabolism under these two culture conditions also differs (29, 32, 48).

All these data support that expression of the three hydrophobins genes is under the control of different regulatory elements and have contrasting developmental roles necessary for fulfill the life cycle of the fungus.

In this study, P. ostreatus var. ostreatus hydrophobin POH2 was genetically mapped to a distal position in chromosome VII. All the other P. ostreatus hydrophobins have been previously mapped (25) to various chromosomes: Vmh1 to chromosome I, Vmh3 to chromosome X, and Fbh1 and Vmh2/POH3 to chromosome XI. In a recent paper, Larraya et al. (24) mapped some genetic factors controlling monokaryotic and dikaryotic growth rate (QTLs) in P. ostreatus N001. It is noteworthy that all P. ostreatus hydrophobins map close to growth rate QTLs or are involved in digenic interactions related to growth rate variations (24). The structural role of fungal hydrophobins make it easy to speculate about the basis for this finding. The QTL analysis approach reveals genomic regions involved in the control of a quantitative character (such as growth rate); hence, the molecular relationship between the different hydrophobins and growth rate variation merits a further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research project BIO99-0278 of the Comisión Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología and by Funds of the Universidad Pública de Navarra (Pamplona, Spain).

The authors acknowledge to Sigga Asgeirsdóttir for the anti-SC3 antibodies and for the POH2 and POH3 cDNAs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdellah, M. M. F., M. F. Z. Emara, and T. F. Mohammady. 2000. Open field interplanting of oyster mushroom with cabbage and its effect on the subsequent eggplant crop. Ann. Hortic. Sci. Cairo 45:281-293. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando, A., A. Harada, K. Miura, and Y. Tamai. 2001. A gene encoding a hydrophobin, fvh1, is specifically expressed after the induction of fruiting in the edible mushroom Flammulina velutipes. Curr. Genet. 39:190-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asgeirsdóttir, S. A. 1994. Proteins involved in emergent growth of Schizophyllum commune. Ph.D. thesis. University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

- 4.Asgeirsdóttir, S. A., O. M. de Vries, and J. G. Wessels. 1998. Identification of three differentially expressed hydrophobins in Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom). Microbiology 144:2961-2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asgeirsdóttir, S. A., J. R. Halsall, and L. A. Casselton. 1997. Expression of two closely linked hydrophobin genes of Coprinus cinereus is monokaryon-specific and down-regulated by the oid-1 mutation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 22:54-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Axtell, C., C. G. Johnston, and J. A. Bumpus. 2000. Bioremediation of soil contaminated with explosives at the Naval Weapons Station Yorktown. Soil Sediment Contam. 9:537-548. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballero, M., E. Mascia, A. Rescigno, and E. S. di Teulada. 1990. Use of Pleurotus for transformation of polyphenols in waste waters from olive presses into proteins. Micol. Italiana 19:39-41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bause, E. 1983. Structural requirements of N-glycosylation of proteins. Studies with proline peptides as conformational probes. Biochem. J. 209:331-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell-Pedersen, D., J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros. 1996. Distinct cis-acting elements mediate clock, light, and developmental regulation of the Neurospora crassa eas (ccg-2) gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:513-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, R. 1996. Functional properties of edible mushrooms. Nutr. Rev. 54:91-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church, G. M., and W. Gilbert. 1984. Genomic sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:1991-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Groot, P. W., P. J. Schaap, A. S. Sonnenberg, J. Visser, and L. J. Van Griensven. 1996. The Agaricus bisporus hypA gene encodes a hydrophobin and specifically accumulates in peel tissue of mushroom caps during fruit body development. J. Mol. Biol. 257:1008-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellaporta, S. L., J. Wood, and J. B. Hicks. 1983. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant Mol. Biol. Reporter 1:19-21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vocht, M. L., K. Scholtmeijer, E. W. van der Vegte, O. M. de Vries, N. Sonveaux, H. A. Wosten, J. M. Ruysschaert, G. Hadziloannou, J. G. Wessels, and G. T. Robillard. 1998. Structural characterization of the hydrophobin SC3, as a monomer and after self-assembly at hydrophobic/hydrophilic interfaces. Biophys. J. 74:2059-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries, O. M. H., M. P. Fekkes, H. A. B. Wösten, and J. G. H. Wessels. 1993. Insoluble hydrophobin complexes in the walls of Schizophyllum commune and other filamentous fungi. Arch. Microbiol. 159:330-335. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dons, J. J. M., J. Springer, S. C. de Vries, and J. G. H. Wessels. 1984. Molecular cloning of a gene abundantly expressed during fruiting body initiation in Schizophyllum commune. J. Bacteriol. 157:802-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eger, G. 1976. Pleurotus ostreatus-breeding potential of a new cultivated mushroom. Theor. Appl. Genet. 47:155-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giardina, P., V. Aurilia, R. Cannio, L. Marzullo, A. Amoresano, R. Siciliano, P. Pucci, and G. Sannia. 1996. The gene, protein and glycan structures of laccase from Pleurotus ostreatus. Eur. J. Biochem. 235:508-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunde-Cimerman, N. 1999. Medicinal value of the genus Pleurotus (Fr.) P. Karst. (Agaricales s.l., Basidiomycetes). Intl. J. Med. Mushrooms 1:69-80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrán, A., L. Estioko, D. Becker, M. J. B. Rodríguez, W. Rohde, and E. Ritter. 2000. Linkage mapping and QTL analysis in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 101:292-300. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katayose, Y., K. Shishido, and M. Ohmasa. 1986. Cloning of Lentinus edodes mitochondrial DNA fragment capable of autonomous replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 138:1110-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larraya, L., M. M. Peñas, G. Pérez, C. Santos, E. Ritter, A. G. Pisabarro, and L. Ramírez. 1999. Identification of incompatibility alleles and characterisation of molecular markers genetically linked to the A incompatibility locus in the white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Curr. Genet. 34:486-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larraya, L. M., E. Idareta, D. Arana, E. Ritter, A. G. Pisabarro, and L. Ramírez. 2002. Quantitative trait loci controlling vegetative growth rate in the edible basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1109-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larraya, L. M., G. Perez, E. Ritter, A. G. Pisabarro, and L. Ramírez. 2000. Genetic linkage map of the edible basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5290-5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau, G., and J. E. Hamer. 1996. Regulatory genes controlling MPG1 expression and pathogenicity in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell 8:771-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lugones, L., J. S. Bosscher, K. Scholtmeyer, O. M. H. de Vries, and J. G. H. Wessels. 1996. An abundant hydrophobin (ABH1) forms hydrophobic rodlet layers in Agaricus bisporus. Microbiology 142:1321-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lugones, L. G., H. A. B. Wösten, and J. G. H. Wessels. 1998. A hydrophobin (ABH3) specifically secreted by vegetatively growing hyphae of Agaricus bisporus (common white button mushroom). Microbiology 144:2345-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez, M. J., B. Boeckle, S. Camarero, F. Guillén, and A. T. Martínez. 1996. MnP isoenzymes produced by two Pleurotus species in liquid culture and during wheat-straw solid state fermetation. ACS Symp. Ser. 655:183-196. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marzullo, L., R. Cannio, P. Giardina, M. T. Santini, and G. Sannia. 1995. Veratryl alcohol oxidase from Pleurotus ostreatus participates in lignin biodegradation and prevents polymerization of laccase-oxidized substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 270:3823-3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merril, C. R., D. Goldman, S. A. Sedman, and M. H. Ebert. 1981. Ultrasensitive stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels shows regional variation in cerebrospinal fluid proteins. Science 211:1437-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minjares-Carranco, A., G. Viniegra-González, B. A. Trejo-Aguilar, and G. Aguilar. 1997. Physiological comparison between pectinase-producing mutants of Aspergillus niger adapted either to solid-state fermentation or submerged fermentation. Enz. Microb. Technol. 21:25-31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakari-Setala, T., N. Aro, N. Kalkkinen, E. Alatalo, and M. Penttila. 1996. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the Trichoderma reesei hydrophobin HFBI. Eur. J. Biochem. 235:248-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng, W. L., T. P. Ng, and H. S. Kwan. 2000. Cloning and characterization of two hydrophobin genes differentially expressed during fruit body development in Lentinula edodes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peñas, M. M. 1999. Hidrofobinas asociadas a diferentes fases del desarrollo del hongo Pleurotus ostreatus. Ph.D thesis. Universidad Pública de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain.

- 36.Peñas, M. M., S. A. Asgeirsdóttir, I. Lasa, F. A. Culiañez-Macià, A. G. Pisabarro, J. G. H. Wessels, and L. Ramírez. 1998. Identification, characterization, and in situ detection of a fruit-body-specific hydrophobin of Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4028-4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puniya, A. K., K. G. Shah, S. A. Hire, R. N. Ahire, M. P. Rathod, and R. S. Mali. 1996. Bioreactor for solid-state fermentation of agro-industrial wastes. Indian J. Microbiol. 36:177-178. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter, E., C. Gebhardt, and F. Salamini. 1990. Estimation of recombination frequencies and construction of RFLP linkage maps in plants from crosses between heterozygous parents. Genetics 125:645-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritter, E., and F. Salamini. 1996. The calculation of recombination frequencies in crosses of allogamous plant species with applications for linkage mapping. Genet. Res. 67:55-65. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santos, C., and J. Labarère. 1999. Aa-Pri2, a single-copy gene from Agrocybe aegerita, specifically expressed during fruiting initiation, encodes a hydrophobin with a leucine-zipper domain. Curr. Genet. 35:564-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segers, G. C., W. Hamada, R. P. Oliver, and P. D. Spanu. 1999. Isolation and characterisation of five different hydrophobin-encoding cDNAs from the fungal tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:644-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shuren, F. H. J., and J. G. H. Wessels. 1990. Two genes specifically expressed in fruiting dikaryons of Schizophyllum commune: homologies with a gene not regulated by mating-type genes. Gene 90:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonnenberg, A. M., P. W. J. d. Groot, P. J. Schaap, J. J. P. Baars, J. Visser, and L. L. J. L. D. van Griensven. 1996. Isolation of expressed sequence tags of Agaricus bisporus and their assignment to chromosomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4542-4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talbot, N. J., H. R. K. McCafferty, M. Ma, K. Moore, and J. E. Hamer. 1997. Nitrogen starvation of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea may act as an environmental cue for disease symptom expression. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 50:179-195. [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Wetter, M. A., H. A. Wösten, and J. G. Wessels. 2000. SC3 and SC4 hydrophobins have distinct roles in formation of aerial structures in dikaryons of Schizophyllum commune. Mol. Microbiol. 36:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Viniegra-González, G. 1997. Solid state fermentation: definition, characteristics, limitations and monitoring, p. 5-22. In S. Roussos, B. K. Lonsane, M. Raimbault, and G. Viniegra-González (ed.), Advances in solid-state fermentation. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordecht, The Netherlands.

- 49.Wessels, J. G. 1999. Fungi in their own right. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27:134-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wessels, J. G. H. 1992. Gene expression during fruiting in Schizophyllum commune. Mycol. Res. 96:609-620. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wessels, J. G. H. 1997. Hydrophobins: proteins that change the nature of fungal surface. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 38:1-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wessels, J. G. H., G. H. Mulder, and J. Springer. 1987. Expression of dikaryon-specific and non-specific mRNAs of Shizophyllum commune in relation to environmental conditions and fruiting. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:2557-2561. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whiteford, J. R., and P. D. Spanu. 2001. The hydrophobin HCf-1 of Cladosporium fulvum is required for efficient water-mediated dispersal of conidia. Fungal Genet. Biol. 32:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wösten, H. A. B., S. A. Asgeirsdottir, J. H. Krook, J. H. H. Drenth, and J. G. H. Wessels. 1994. The fungal hydrophobin Sc3p self-assembles at the surface of aerial hyphae as a protein membrane constituting the hydrophobic rodlet layer. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 63:122-129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]