Abstract

Drug-induced transcriptomic data are crucial for understanding molecular mechanisms of action (MOAs), predicting drug efficacy, and identifying off-target effects. However, their high dimensionality presents challenges for analysis and interpretation. Dimensionality reduction (DR) methods simplify such data, enabling efficient analysis and visualization. Despite their importance, few studies have evaluated the performance of DR methods specifically for drug-induced transcriptomic data. We tested the DR methods across four distinct experimental conditions using data from the Connectivity Map (CMap) dataset, which includes different cell lines, drugs, MOA, and drug dosages. t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), Pairwise Controlled Manifold Approximation (PaCMAP), and TRIMAP outperformed other methods in preserving both local and global biological structures, particularly in separating distinct drug responses and grouping drugs with similar molecular targets. However, most methods struggled with detecting subtle dose-dependent transcriptomic changes, where Spectral, Potential of Heat-diffusion for Affinity-based Trajectory Embedding (PHATE), and t-SNE showed stronger performance. Standard parameter settings limited the optimal performance of DR methods, highlighting the need for further exploration of hyperparameter optimization. Our study provides valuable insights into the strengths and limitations of various DR methods for analyzing drug-induced transcriptomic data. While t-SNE, UMAP, and PaCMAP are well-suited for studying discrete drug responses, further refinement is needed for detecting subtle dose-dependent changes. This study highlights the importance of selecting the DR method to accurately analyze drug-induced transcriptomic data.

Keywords: Dimension reduction, Drug-induced transcriptome, CMap data, RNA-seq analysis

Subject terms: Machine learning, Computer science

Introduction

Drug-induced transcriptomic data, which represent genome-wide expression profiles induced by drug treatments, are valuable in drug discovery research by revealing how drugs affect gene expression across various biological contexts. These data are especially useful in identifying molecular MOAs, assessing potential off-target effects, and predicting drug efficacy, all of which key factors in the early stages of drug development1,2. However, the high dimensionality of transcriptomic data, where each expression profile contains tens of thousands of gene expression measurements, presents significant challenges in data analysis and interpretation.

Dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques offer a powerful solution by transforming high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving biologically meaningful structure. This enables more efficient downstream analyses, including clustering, trajectory inference, and visualization. While DR methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) have been widely applied across transcriptomic and single-cell datasets3,4, systematic benchmarking of these tools in the context of drug-induced transcriptomic data remains limited. This gap is increasingly important to address given the growing volume of pharmacogenomic datasets generated across diverse experimental conditions. Recent initiatives have accelerated the production of large-scale transcriptomic profiles from both in vivo and in vitro drug perturbation studies5–8, dramatically expanding opportunities for understanding drug responses at the molecular level9,10. Among such resources, the Connectivity Map (CMap)7,8 stands out as the most comprehensive and widely utilized drug-induced transcriptome dataset. It comprises millions of gene expression profiles across hundreds of cell lines exposed to over 40,000 small molecules, encompassing a broad spectrum of doses and MOAs. CMap has been instrumental in predicting molecular MOAs, drug-target interactions, and identifying potential off-target effects11–16. Despite the availability of such expansive datasets, there is a lack of rigorous comparative studies evaluating which DR methods are most effective for preserving biologically relevant patterns in drug-induced transcriptomic data.

In this study, we addressed this gap by systematically evaluating 30 widely used DR methods for their ability to preserve drug-induced transcriptomic signatures in reduced-dimensional space. We tested these methods across four experimental conditions: different cell lines treated with the same drug, the same cell line treated with different drugs, the same cell line treated with drugs targeting different MOAs, and the same cell line treated with varying dosages of the same drug. By comparing the performance of these DR methods, we aimed to provide guidance on the most appropriate techniques for studying drug responses and interpreting high-dimensional transcriptomic data.

Results

Study overview

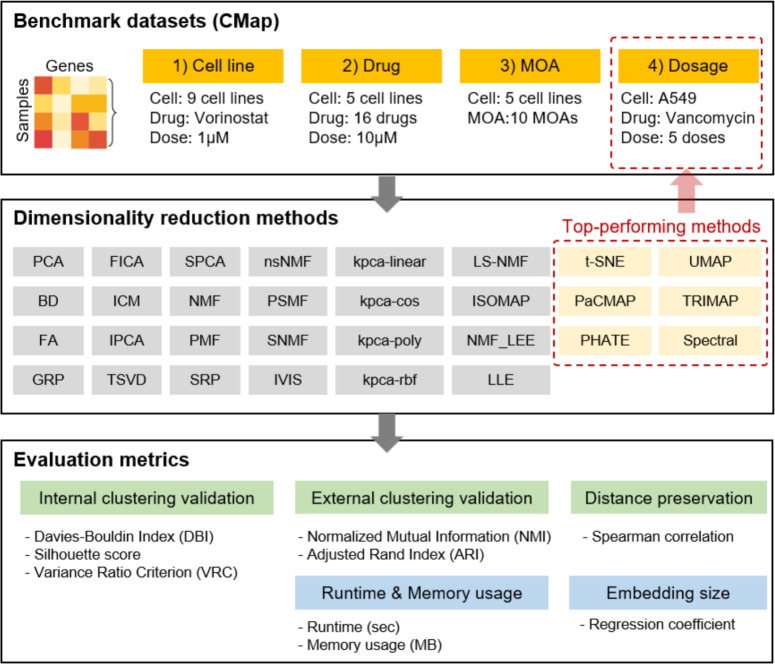

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of DR algorithms in preserving the unique biological signatures induced by drug perturbations within high-dimensional transcriptome data (Fig. 1). Nine cell lines with the largest number of high-quality profiles in the CMap dataset were selected: A549, HT29, PC3, A375, MCF7, HA1E, HCC515, HEPG2, and NPC. The benchmark dataset comprised 2,166 drug-induced transcriptomic change profiles, each represented as z-scores for 12,328 genes. DR performance was assessed under four benchmark conditions: (i) different cell lines treated with the same compound (n=152), (ii) a single cell line treated with multiple compounds (n=635), (iii) a single cell line treated with compounds targeting distinct MOAs (n=1,330), and (iv) a single cell line treated with the same compound at varying dosages (n=49) (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

The CMap drug-induced transcriptomic data were categorized into four benchmark sets. Various DR algorithms were evaluated using six performance metrics, including clustering validity and distance preservation. Additional assessments included sensitivity to embedding dimension, computational runtime, and memory usage.

All 30 DR methods (Tables 1 and 2) were evaluated using internal and external clustering validation metrics under conditions (i) through (iii). For benchmark conditions (ii) and (iii), independent datasets were constructed for five representative cell lines (A549, HT29, PC3, A375, and MCF7), selected based on the number of high-quality profiles and diversity of drug treatments. Based on consistent performance across these evaluations, six DR methods were identified as top-performing. The fourth benchmark condition, which focused on dose-dependent transcriptomic variation, was evaluated only for the A549 cell line using the six top-performing methods. Additional analyses were also conducted using A549 data, including assessments of performance across embedding dimensions (2, 4, 8, 16, and 32), pairwise distance preservation, computational runtime and memory usage, and two-dimensional visualizations for interpretability.

Table 1.

Linear DR Methods.

| Method | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis30 | PCA | PCA transforms correlated variables into an orthogonal basis of uncorrelated principal components, reducing dimensionality while capturing the most variance. |

| Bayesian Decomposition31 | BD | BD uses a Gibbs sampler to iteratively estimate the posterior distributions of NMF factors for better decomposition of non-negative data. |

| Factor Analysis32 | FA | FA uses a generative model with Gaussian latent variables to extract common variance and transform variables into single scores for analysis. |

| Gaussian Random Projection33 | GRP | GRP uses a matrix with normally distributed components to project data, preserving structure as per the Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma. |

| Fast ICA34 | FastICA | Fast ICA extracts statistically independent non-Gaussian signals from mixed data using negative entropy for efficient separation. |

| Iterated Conditional Modes31 | ICM | ICM is similar to BD but uses iterative conditional modes instead of random sampling in the Gibbs sampler for variable selection. |

| Incremental PCA35 | IPCA | IPCA is a mini-batch implementation of PCA that incrementally updates the transformation matrix with each new data batch. |

| Truncated SVD36 | TSVD | Contrary to PCA, TSVD does not center the data before computing the singular value decomposition. |

| Sparse PCA37 | SPCA | SPCA extends PCA by applying L1 norm constraints, such as lasso or elastic net, to produce principal components with sparse loadings for better interpretability. |

| Non-negative Matrix Factorization38,39 | NMF (NNSVD/LEE) | NMF is a specialized form of matrix factorization, particularly effective for dealing with data matrices that contain only non-negative elements. |

| Least squares NMF40 | LS-NMF | LS-NMF modifies NMF by using least squares optimization in the update rules instead of multiplicative updates, allowing for faster convergence. |

| Non-Smooth Nonnegative Matrix Factorization41 | nsNMF | nsNMF optimizes a clear cost function to represent sparseness through non-smoothness, producing localized patterns in basis and encoding vectors for better interpretability. |

| Sparse Random Projection42 | SRP | SRP uses a sparse matrix with elements drawn from a zero-inflated, centered uniform distribution. |

| Probabilistic non negative Matrix Factorization43 | PMF | PMF assumes the data follows a multinomial distribution and uses expectation maximization to determine latent features for users and items. |

| Probabilistic sparse MF44 | PSMF | PSMF introduces Gaussian noise and a sparsity constraint using Laplacian distribution to identify relevant latent features and manage long-tail items effectively. |

| Sparse Non-negative Matrix Factorization45 | SNMF | SNMF adds a sparsity constraint to the activation coefficients, improving the quality of basis functions. |

| Kernel PCA(linear)46 | kpca-linear | kpca-linear is a function that computes the dot product between two input vectors, representing a linear relationship in the feature space. |

This table summarizes various linear DR methods that transform high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional representations

Table 2.

Non-linear DR Methods.

| Method | Abbreviation | Global/local property | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isometric Mapping47 | ISOMAP | Global | ISOMAP extends MDS by mapping data to a lower-dimensional space using geodesic distances on a neighborhood graph. |

| Kernel PCA (with cosine, polynomial, and radial basis function transformation)46 | kpca-cos, poly, rbf | Global | k-pca exploits the complex spatial structure of high-dimensional features, allowing for better data representation in lower-dimensional spaces. |

| Pairwise Controlled Manifold Approximation17 | PaCMAP | Global, local | PaCMAP optimizes embeddings by controlling distances using neighbor, mid-near, and farther point pairs, providing efficient performance without parameter tuning. |

| Potential of Heat-diffusion for Affinity-based Trajectory Embedding26 | PHATE | Global, local | PHATE uses a heat diffusion model to preserve branching structures, embedding them in low-dimensional space via heat potentials. |

| Laplacian Eigenmaps29 | Spectral | Local | Laplacian Eigenmaps reconstructs the manifold in a lower-dimensional space by preserving distances between nearest neighbors on a weighted graph. |

| TriMap48 | TRIMAP | Global, local | TRIMAP uses triplet constraints to optimize embeddings by minimizing triplet loss, focusing on preserving relative distances between clusters. |

| Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection49 | UMAP | Global, local | UMAP uses Riemannian geometry and algebraic topology to construct a fuzzy topological representation of data for low-dimensional embeddings. |

| Locally Linear Embedding50 | LLE | Local | LLE reduces dimensionality by linearly reconstructing data in a lower-dimensional space, avoiding local minima during optimization. |

| t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding23 | t-SNE | Local | t-SNE minimizes KL divergence by modeling high-dimensional similarities with Gaussian distributions and low-dimensional similarities with Cauchy distributions. |

| ivis51 | IVIS | Global, local | IVIS uses Siamese Neural Networks for scalable embeddings and efficient integration of new data points through a parametric mapping function. |

This table presents non-linear DR methods, categorized by their ability to preserve global, local, or both types of data structures: global structure preserving techniques retain overall data properties, while local structure preserving techniques focus on maintaining local relationships. Some methods aim to preserve both global and local structures, offering a more comprehensive low-dimensional representation

Preserved biological similarity in representation space

To determine each DR method’s ability to maintain the structural quality of the reduced-dimensional space, we employed three well-established internal cluster validation metrics17: Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI)18, Silhouette score19, and Variance Ratio Criterion (VRC)20. These metrics quantify the extent to which each method preserves cluster compactness and separability based solely on the intrinsic geometry of the embedded data, without reference to external ground truth labels.

The ranking of the DR methods showed high concordance across the three metrics (Cell: Kendall’s W=0.94,  , MOA: Kendall’s W=0.93,

, MOA: Kendall’s W=0.93,  , Drug: Kendall’s W=0.91,

, Drug: Kendall’s W=0.91,  ), indicating a general agreement in their performance evaluation. Notably, DBI consistently yielded higher scores across all methods compared to the other metrics, whereas VRC tended to assign lower scores, suggesting potential overestimation or underestimation (Fig. 2A ). Silhouette scores, which fell between DBI and VRC scores, offered a more balanced assessment. Among the evaluated methods, PaCMAP, TRIMAP, t-SNE, and UMAP consistently ranked in the top five across the datasets. UMAP and t-SNE, in particular, achieved high scores and rankings, reaffirming their utility in transcriptome analysis. In contrast PCA, despite its simplicity and widespread application, performed relatively poorly in preserving biological similarity of the profiles.

), indicating a general agreement in their performance evaluation. Notably, DBI consistently yielded higher scores across all methods compared to the other metrics, whereas VRC tended to assign lower scores, suggesting potential overestimation or underestimation (Fig. 2A ). Silhouette scores, which fell between DBI and VRC scores, offered a more balanced assessment. Among the evaluated methods, PaCMAP, TRIMAP, t-SNE, and UMAP consistently ranked in the top five across the datasets. UMAP and t-SNE, in particular, achieved high scores and rankings, reaffirming their utility in transcriptome analysis. In contrast PCA, despite its simplicity and widespread application, performed relatively poorly in preserving biological similarity of the profiles.

Figure 2.

Performance evaluation of 30 DR methods using internal and external cluster validation metrics across three distinct benchmark set.(A) Normalized scores for internal validation metrics (DBI, Sil, and VRC) for 30 DR methods (columns) across three experimental condition datasets (rows). Scores were min-max normalized for each dataset. DR methods are ranked based on the average of the three metrics within each dataset. (B) Scores for external validation metrics (ARI and NMI) across the for 30 DR methods (columns) across datasets (rows). DR methods are ranked by the average of these two metrics within each dataset. (C) A comparison of Sil and NMI scores of individual DR methods across dataset. DR methods that achieved the highest rankings in both scores are highlighted within the red box in the upper right corner.

To better understand the observed variability in DR performance across experimental conditions, it is necessary to consider the underlying algorithmic principles that govern each method. DR techniques are grounded in different mathematical formulations and optimization criteria, which in turn affect how they represent biological relationships in lower-dimensional space. For example, t-SNE minimizes the Kullback-Leibler divergence between high- and low-dimensional pairwise similarities, with a strong emphasis on preserving local neighborhoods. This feature makes it particularly effective for capturing local cluster structures, as commonly observed in single-cell transcriptomic data. UMAP applies a cross-entropy loss to balance local and limited global structure, offering improved global coherence compared to t-SNE. Methods such as PaCMAP and TRIMAP incorporate additional distance-based constraints, such as mid-neighbor pairs or triplets, which enhance their ability to preserve both local detail and long-range relationships. PHATE models diffusion-based geometry to reflect manifold continuity, making it well-suited for datasets with gradual biological transitions. In contrast, PCA reduces dimensionality by identifying directions of maximal variance, which aids in global structure preservation and interpretability, but may obscure finer local differences. These differences in algorithmic design explain, in part, the differential performance of DR methods across diverse biological contexts.

Performance of clustering after dimensionality reduction

We next evaluated the concordance between sample labels and clusters defined through unsupervised clustering in the reduced embedding space produced by DR methods. Five clustering algorithms–hierarchical clustering, k-means, k-medoids, HDBSCAN, affinity propagation–were applied to embeddings generated by the top five DR methods. Clustering accuracy was measured using normalized mutual information (NMI) and adjusted rand index (ARI), with the sample labels serving as the ground truth (i.e., cell lines, MOAs, or drugs for each dataset). These external validation metrics evaluate how well the clustering results align with the ground truth labels, by quantifying intra-label similarity (i.e., profiles within the same experimental condition) and inter-label differences (i.e., profiles from distinct experimental conditions). Hierarchical clustering consistently outperformed other methods across both NMI and ARI (Supplementary Fig. 1). Using hierarchical clustering, we further evaluated the clustering accuracy after DR. Overall, the NMI and ARI scores showed a high degree of concordance (Cell: Kendall’s W=0.99, P=0.0013, MOA: Kendall’s W=0.98, P=0.0015, Drug: Kendall’s W=0.97, P=0.0016) (Fig. 2B ). In addition, a moderately strong linear correlation was observed between NMI and silhoutte scores (Cell: r=0.95,  ; Kendall’s W=0.97, P=0.002 , MOA: r=0.91,

; Kendall’s W=0.97, P=0.002 , MOA: r=0.91,  ; Kendall’s W=0.95, P=0.002 , Drug: r=0.89,

; Kendall’s W=0.95, P=0.002 , Drug: r=0.89,  ; Kendall’s W=0.94, P=0.003 ) (Fig. 2C ), suggesting that the internal and external cluster validation metrics provided consistent performance assessments. Although slight fluctuations were observed in the rankings between internal and external validation metrics, the top 10 DR methods remained consistent across both types of metrics.

; Kendall’s W=0.94, P=0.003 ) (Fig. 2C ), suggesting that the internal and external cluster validation metrics provided consistent performance assessments. Although slight fluctuations were observed in the rankings between internal and external validation metrics, the top 10 DR methods remained consistent across both types of metrics.

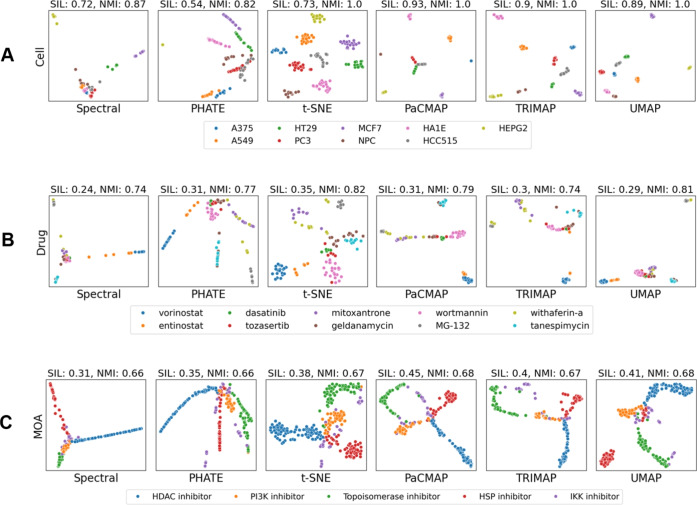

Interpreting visualizations of dimensionality reduction outcomes

To further interpret the performance of the DR methods, we visualized two-dimensional (2D) embeddings generated by the top six DR methods−PaCMAP, TRIMAP, UMAP, t-SNE, Spectral, and PHATE−across three distinct benchmark datasets (Supplemntary Fig. 2). Notably, UMAP, PaCMAP, t-SNE, and TRIMAP excelled at segregating different cell lines into distinct clusters, indicating that they effectively captured the cell-type-specific transcriptomic responses to drug treatments (Fig. 3A ). Beyond cell line separation, UMAP, t-SNE, and PaCMAP also performed well in differentiating drug-specific transcriptomic responses, though some overlap occurred between drugs with similar molecular targets, such as geldanamycin and tanespimycin (both targeting heat shock proteins) and vorinostat and entinostat (both targeting histone deacetylase) (Fig. 3B ). However, for datasets labeled by drug’s MOA, DR methods showed less consistency, with NMI scores below 0.7 (Supplementary Fig. 3). This reduced performance can be attributed to the substantial overlap observed in certain MOA classes, such as inhibitory Kappa B Kinase  (IKK) inhibitors (Fig. 3C ). This overlap is likely due to the broad influence of IKK inhibitors on multiple biological pathways, particularly those related to cytokine production and inflammatory responses. Consequently, IKK inhibitors share transcriptomic signatures with drugs targeting other pathways, making them less distinct and harder to differentiate in the reduced space. In contrast, cells treated with drugs, including histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, heat shock protein (HSP) inhibitors, and topoisomerase inhibitors, formed more distinct and cohesive clusters across all six methods. While UMAP and t-SNE were able to separate cells treated with drugs targeting different MOAs into cohesive clusters, other methods tended to arrange these cells along linear trajectories, which resulted in weaker internal cohesion within clusters.

(IKK) inhibitors (Fig. 3C ). This overlap is likely due to the broad influence of IKK inhibitors on multiple biological pathways, particularly those related to cytokine production and inflammatory responses. Consequently, IKK inhibitors share transcriptomic signatures with drugs targeting other pathways, making them less distinct and harder to differentiate in the reduced space. In contrast, cells treated with drugs, including histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, heat shock protein (HSP) inhibitors, and topoisomerase inhibitors, formed more distinct and cohesive clusters across all six methods. While UMAP and t-SNE were able to separate cells treated with drugs targeting different MOAs into cohesive clusters, other methods tended to arrange these cells along linear trajectories, which resulted in weaker internal cohesion within clusters.

Fig. 3.

Two-dimensional (2D) visualizations of reduced dimensional space derived by the top six DR methods for three distinct experimental condition datasets involving different cell lines (A), drugs (B), or MOAs (C). For each plot, Sil and NMI scores are displayed in the upper corner. The legends on the right indicate the biological labels of the samples in each dataset.

Overall, UMAP, t-SNE, followed by TRIMAP, and PaCMAP, consistently formed well-defined clusters, providing a good balance between preserving both local neighborhood structures and broader global relationships. These methods are particularly well-suited for datasets with clear biological categories, such as distinct cell lines or drug-specific responses. PHATE and Spectral, on the other hand, produced more linear or trajectory-like visualizations, which would better suit datasets representing continuous transitions, such as those found in dose-response or time-series experiments.

Our findings are in agreement with previous comparative studies, including the work by Huang et al. (2022)21, which systematically evaluated the visual outputs of major DR algorithms. In that study, UMAP was found to effectively preserve local neighborhood structures but sometimes failed to maintain global relationships, leading to merged or ambiguous cluster boundaries. Similarly, t-SNE exhibited strong performance in forming tight local clusters but was limited in representing the overall data topology. TRIMAP provided a compromise by preserving both local and global patterns, though its embeddings occasionally produced diffuse clusters with less visual clarity. PHATE excelled in representing continuous or transitional biological processes, but its emphasis on smooth trajectories often resulted in blurred boundaries between compact clusters, consistent with its diffusion-based formulation22. Notably, Spectral revealed linear or gradient-like arrangements of samples, highlighting their potential utility in visualizing expression changes across biological gradients, such as temporal or dose-dependent responses22. Collectively, these results emphasize that the choice of DR method should be aligned not only with clustering accuracy but also with the interpretability of the reduced-dimensional space in the context of specific biological questions.

Effect of dimension reduction on distance preservation

We next focused on how well DR methods preserved pairwise distances in the original high-dimensional space. To quantify this, we calculated the Spearman correlation coefficient of pairwise distances for all samples before and after DR. A high correlation indicates that the DR method effectively retains relative sample distances, thus maintaining the integrity of the original data structure in the reduced-dimensional space. Among the top six DR methods, t-SNE demonstrated the overall highest Spearman correlation for all three datasets, suggesting superior retention of both inter-sample and inter-cluster relationships (Fig. 4). TRIMAP, PaCMAP, and PHATE also performed well in preserving pairwise distances of datasets involving various drugs. By contrast, UMAP, despite strong local performance, showed relatively weaker global correlations, indicating potential limitations in representing broader data structures.

Fig. 4.

Spearman correlation coefficient values of pairwise distances between samples in the original and reduced-dimensional space for the top six DR methods across datasets. High correlation values indicate a strong preservation of the original data structure in the reduced-dimensional space, reflecting the effectiveness of each DR method in maintaining both local and global relationships between samples.

This analysis reflects each algorithm’s intrinsic emphasis on maintaining global or local relationships. Methods such as t-SNE and TRIMAP incorporate ranking-based loss functions or triplet constraints that prioritize the relative positioning of samples in the low-dimensional space. These design features contribute to their strong performance in retaining the pairwise distances, as supported by high Spearman correlation scores. Consistent with our results, previous benchmarks (e.g., Huang et al. 202221) have also highlighted t-SNE’s capability in conserving inter-sample relationships. PaCMAP and TRIMAP similarly maintained topological continuity by integrating mid- and long-range distance constraints into their optimization routines.

Effect of embedding size on clustering accuracy

In DR, the embedding size is often set to 2 for easy of visualization in two-dimensionality space. However, the optimal embedding size may vary depending on the specific research objectives, and the impact of embedding size on clustering accuracy is not always straightforward23. To roughly examine how embedding size influences clustering accuracy, we assessed NMI scores across five different embedding sizes (2, 4, 8, 16, and 32) for 30 DR methods. This analysis revealed fluctuations in clustering accuracy as the embedding size increased (Supplementary Fig. 4). Based on these trends, we categorized the DR methods into three groups: i) increasing, ii) stable, and iii) decreasing groups, according to the relationship between embedding size and NMI scores as determined by regression analysis. Notably, five of the top six methods exhibited stable performance across all embedding sizes (Fig. 5), suggesting their robustness and flexibility in maintaining clustering accuracy regardless of dimensionality. In contrast, two methods, Spectral and t-SNE, showed a marked decrease in clustering accuracy as embedding size increased. Specifically, t-SNE consistently performed best at the smallest embedding size (2) across all datasets, highlighting its strength in low-dimensional representations.

Fig. 5.

The impact of embedding size on clustering accuracy for the top six DR methods. The NMI scores for the top six DR methods across five embedding sizes (2, 4, 8, 16, and 32) are displayed for three datasets. These DR methods are categorized into stable and decreasing groups based on the relationship between embedding size and NMI scores, as determined by regression analysis.

Evaluation of DR methods for capturing dose-dependent transcriptomic changes

Lastly, we assessed the ability of DR methods to capture subtle differences in cellular responses that arise from dose-dependent effects. Detecting these variations is critical in drug development research, as both drug efficacy and toxicity are closely linked to drug concentration. However, distinguishing gene expression profiles across different dosages poses a significant challenge, as drugs often induce gradual and nuanced changes in gene expression across concentrations24. To address this, we applied the DR methods to datasets where the same cell lines treated with the same drugs at varying dosages, specifically within their therapeutic range25.

As a case study, we selected vancomycin, a drug known for its a narrow therapeutic range, to assess how well the methods could capture dose-dependent therapeutic effects. Across all methods, we found that most methods struggled to capture dose-dependent differences, with lower silhouette and NMI scores compared to other experimental conditions (Fig. 6A ). This result reflects the inherent difficulty in capturing the subtle, dose-dependent transcriptomic variations. SPECTRAL, PHATE and t-SNE showed relatively strong performance in generating dose-dependent trajectories in reduced space, while PaCMAP, TRIMAP, and UMAP successfully distinguished high and low doses but performed poorly at intermediate doses (Fig. 6B ).

Fig. 6.

The performance of the top six DR methods for differentiating drug dosages. (A) Bar plots depicting three evaluation metrics (Silhouette, NMI, and Spearman correlation) for the six DR methods applied to vancomycin-induced transcriptome data across varying dosages. (B) Two-dimensional visualizations of the reduced-dimensional space after applying the top six DR methods. For each plot, the Sil and NMI score are displayed in the upper corner. The legends on the right indicate the treatment concentration ( M) of the samples.

M) of the samples.

PHATE, which models diffusion-based transitions, proved particularly effective in representing these smooth progressions, aligning with previous findings that demonstrated its superiority in capturing developmental or pseudotemporal trajectories (Moon et al. 201926). However, consistent with earlier reports22, PHATE’s embeddings also tended to produce diffuse clusters in scenarios where sharp group separation is required. Methods such as PaCMAP, TRIMAP, and UMAP more clearly distinguished high and low dosages, but exhibited limitations in resolving intermediate concentrations, where gene expression profiles overlap.

Performance summary

Across the four benchmark datasets, we observed that the performance of DR methods varied depending on the underlying biological context (Fig. 7). t-SNE consistently yielded strong results in datasets requiring fine local resolution, particularly in the drug-labeled dataset, where drugs with similar MOAs often form overlapping expression profiles. Its emphasis on local neighborhood preservation appears advantageous in distinguishing subtle pairwise differences among related compounds. Conversely, in the MOA-labeled dataset, where the goal is to separate mechanistically distinct drug classes, UMAP, PaCMAP, and TRIMAP showed superior performance. These methods more effectively preserve global structure, enabling clearer separation of dissimilar groups in reduced-dimensional space. SPECTRAL and PHATE excelled in continuous, gradual transitions but struggled with discrete clustering tasks. In addition to performance, we also compared the computational efficiency of the top-performing methods under standardized settings (Supplementary Table 2 and 3). UMAP required the longest runtime, whereas PHATE and Spectral showed relatively fast computation times, which is an important consideration for practical applications involving large-scale datasets.

Fig. 7.

Overall performance of the six DR methods using three evaluation metrics (Sil, NMI, and Spearman) across four distinct benchmark datasets (Cell, Drug, MOA, and Dose). Methods are sorted from highest to lowest based on their performance for each metric, with darker colors representing better scores.

To further assess method-specific robustness, we examined the sensitivity of t-SNE and UMAP to their key hyperparameters. These two methods were selected as representative non-linear DR algorithms known to be particularly sensitive to parameter tuning27. Performance was evaluated by varying perplexity and learning rate (t-SNE) and the number of neighbors and minimum distance (UMAP). While performance varied with parameter values, improvements over default settings were modest (Supplementary Fig.s 5 and 6), indicating that the use of default configurations provides a reasonable baseline for comparative evaluation. In addition, the computational efficiency of the top-performing DR methods was evaluated using the drug-labeled dataset under standardized settings (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3; Supplementary Fig. 7). UMAP exhibited relatively high runtime across embedding dimensions, while PHATE showed the highest memory usage. In contrast, Spectral, TRIMAP, and PaCMAP were generally efficient in both runtime and memory consumption.

Our observations are in line with findings from previous comparative studies, including those by Huang et al. (2022)21 and Moon et al. (2019)26, which have highlighted the characteristic strengths and limitations of different DR algorithms when applied to biological data. Huang et al.,21 reported that traditional methods such as t-SNE and UMAP demonstrated strong clustering performance but were sensitive to hyperparameter settings, such as perplexity and the number of neighbors. In contrast, newer approaches including PaCMAP and TRIMAP were found to produce more stable embeddings across diverse datasets, with improved consistency in preserving both local and global structures. Notably, PaCMAP was relatively robust to parameter variation, consistently maintaining reliable performance across experimental settings. Moon et al.26 emphasized PHATE’s strength in preserving continuous transitions, particularly in single-cell datasets with underlying developmental or temporal trajectories. In our study, we observed similar trends across various drug-induced transcriptomic scenarios, reinforcing the view that no single DR method is universally optimal. Rather, the suitability of a method depends heavily on the biological context and the analytical objective–whether the task emphasizes discrete cluster separation, topological integrity, or trajectory continuity. Collectively, our results support a task-specific and context-aware approach to DR method selection, allowing researchers to match algorithmic properties with the structure of their data and the nature of their biological questions.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically evaluated 30 DR methods for their ability to preserve drug-induced transcriptomic signatures present in high-dimensional data in reduced space. By applying these methods across four distinct experimental conditions-different cell lines, various drugs, MOAs, and drug dosages-we presented performance comparisons that inform the selection and application of the most appropriate DR method for studying drug responses. This evaluation is particularly important as drug-induced transcriptomic data can reveal significant information about MOA, drug efficacy, and potential off-target effects. Despite the importance of DR in omics data analysis, few studies have focused on how well DR methods perform in this context.

Among the 30 DR methods tested, PaCMAP, TRIMAP, UMAP, t-SNE, Spectral, and PHATE demonstrated superior performance in preserving both intra-label cohesion (grouping samples within the same experimental condition) and inter-label separation (separating samples from different conditions) in reduced-dimensional space. In particular, UMAP, PaCMAP, t-SNE, and TRIMAP excelled in clustering cell lines, with NMI and ARI scores of 1. The ability to distinguish cell-type-specific drug response signatures is important for studying drug efficacy and toxicity, which often depend on unique cellular contexts.

In addition to preserving local relationships (e.g., clustering similar samples), maintaining the pairwise distances of the data is also important for understanding the broader behavior of drugs. Pairwise distance refers to how well the reduced space reflects the original distances between samples. Among the top-performing six DR methods, t-SNE effectively projected the relative pairwise distances between drug-treated samples into the reduced embedding space, as indicated by its high Spearman correlation values. For instance, t-SNE separated cells treated with different drugs while grouping drugs with similar targets, such as geldanamycin and tanespimycin (both targeting heat shock proteins) and vorinostat and entinostat (both targeting histone deacetylase). This capacity to cluster drugs with shared targets emphasizes the utility of t-SNE in predicting potential molecular targets or MOA of unknown compounds.

Identifying dose-dependent transcriptional changes is another key aspect for understanding drug responses, as small variations in dosage can significantly impact both the efficacy and safety of a drug. This is especially important for drugs with a narrow therapeutic range, such as vancomycin, which require careful dosage monitoring in clinical settings to avoid adverse effects. The therapeutic range refers to the dosage window between the minimum effective dose and the dose at which adverse effects occur. Drugs with a wide therapeutic range are generally safer, as there is more flexibility in dosing before toxicity becomes a concern. However, for drugs with a narrow therapeutic range–such as vancomycin, warfarin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and methotrexate–precise dosing is critical, as the difference between an effective and toxic dose is minimal. In our study, we specifically explored how well DR methods capture subtle, dose-dependent transcriptomic changes using datasets in which A549 cell lines were treated with vancomycin at varying dosages within its therapeutic range. While the top-performing DR methods excelled in distinguishing different cell lines or different drug treatments, most struggled to detect the more nuanced gene expression differences associated with varying drug dosages. Differentiating between dosage levels is particularly challenging for DR methods, as the transcriptional changes are often subtle and gradual across concentrations, unlike the more distinct differences observed between cell lines or drug treatments. Spectral, PHATE, and t-SNE showed relatively strong performance in generating dose-dependent trajectories in the reduced embedding space. On the other hand, PaCMAP, TRIMAP, and UMAP were better at distinguishing between high and low dosages but struggled with intermediate dosages, where the gene expression profiles tended to overlap more significantly. This evaluation provides insights into which DR methods are most suitable for discerning fine-grained transcriptomic differences across a range of drug dosages, helping pharmacological studies where dose-dependent effects play a critical role in determining drug safety and efficacy.

This study has several limitations. First, the benchmark was constructed using a limited set of cell lines and compounds, and detailed analyses were restricted to the A549 cell line. The results may not generalize to other biological contexts. Second, all transcriptomic profiles were derived from the CMap level 5 z-score data, which are generated using the L1000 assay8. As this platform infers the expression of most genes from a subset of landmark transcripts, results may differ when applied to datasets produced by full-transcriptome platforms such as RNA-seq or microarrays. Third, all DR methods were evaluated using default hyperparameter settings. This allowed for standardized comparison, but may underestimate the performance of methods sensitive to parameter tuning, such as t-SNE and UMAP27. Another limitation of this study is that it focused exclusively on conventional DR methods. Recent advances in deep learning have introduced DR techniques based on autoencoders, variational autoencoders (VAEs), and generative adversarial networks (GANs), which can capture complex nonlinear patterns beyond the capacity of traditional methods. However, these approaches typically require large datasets, intensive computation, and careful tuning, which may limit their application in exploratory transcriptomic analysis. Given the practical efficiency and interpretability of conventional DR methods, this study was designed to provide a standardized baseline evaluation. Future work will be needed to assess how deep learning-based DR methods compare under similar benchmark conditions.

Methods

Compound-induced transcriptome data and processing

Connectivity Map data were obtained from the Clue.io platform (https://clue.io/data/CMap2020). In this study, we used compound-treated profiles (trt-cp) in moderated Z-score data (also known as ’level 5 data’). We further processed the data to retain samples of good quality (qc_pass  1, cc_q75

1, cc_q75  0.2, pct_self_rank_q25

0.2, pct_self_rank_q25  0.05, and nsample

0.05, and nsample  3) from the total of 205,034 profiles. Our final dataset consisted of 26,938 high-quality samples. Each sample contained expression measurements for 12,328 genes.

3) from the total of 205,034 profiles. Our final dataset consisted of 26,938 high-quality samples. Each sample contained expression measurements for 12,328 genes.

To evaluate 30 DR methods, we constructed distinct experimental benchmark datasets from the large dataset by applying constraints focused on specific factors; (i) different cell lines treated with the same drug (n=152), (ii) the same cell line treated with different drugs (n=635), (iii) the same cell line treated with drugs that have different MOA (n=1,330), and (iv) the same cell line treated with the same drug at varying dosages (n=49). To simplify the evaluation of the DR methods, we limited the sample information to include only the relevant factors. Each dataset was curated by selecting the combination with the largest number of samples while keeping all other factors constant (cell line, drug, MOA or dosage).(Supplementary Table 1)

Dimensionality reduction methods

All data analyses were performed using Python version 3.10.12. For implementing DR methods, we utilized various Python packages: built-in functions from scikit-learn version 1.5.2 for FA, ISOMAP, KernelPCA, NMF, TSVD, SPCA, SRP, FICA, GRP, PCA, IPCA, LDA, LLE, Spectral Embedding, and t-SNE; nimfa version 1.4.0 for SNMF, PSMF, PMF, nsNMF, NMF, LSNMF, ICM, and BD; phate package version 1.0.11 for PHATE; umap-learn version 0.5.6 for UMAP; trimap package version 1.1.4 for TRIMAP; pacmap package version 0.7.3 for PaCMAP; and ivis package version 2.0.11 for IVIS. Unless otherwise specified, all hyperparameters for the DR methods were set to their default values. The maximum number of iterations was fixed at 1,000 to ensure convergence across methods. The embedding size for all methods was set to 2, unless explicitly noted

Evaluation metrics

All evaluation metrics were calculated using built-in functions from the scikit-learn library, which include NMI, ARI, DBI, Sil, and VRC

Adjusted Rand Index(ARI)28: The Rand Index (RI) is a metric used to measure the similarity between two clustering results, where one serves as the ground truth, and the other is the clustering result to be evaluated. The RI is calculated by comparing all pairs of samples and counting those that are consistently placed either in the same or different clusters in both the ground truth and the predicted clustering. ARI improves upon the RI by adjusting for the chance grouping of elements, ensuring a more robust evaluation. ARI values range from -1 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect agreement between the two clustering.

The formula for ARI is:

where:

N: The number of data points in a given data set.

: The number of data points of the class label

: The number of data points of the class label  assigned to cluster

assigned to cluster  in partition P.

in partition P. : The number of data points in cluster

: The number of data points in cluster  in partition P.

in partition P. : The number of data points in class

: The number of data points in class  .

.P(): The predicted clustering

: The true clustering

: The true clustering

Normalized Mutual Information (NMI)29: NMI is also used to quantify the similarity between the clustering result and the true labels by measuring the mutual dependence between the two. It is based on the concept of mutual information, which captures how much knowing one variable reduces uncertainty about the other. The NMI is computed as the mutual information between the predicted and true clusters, normalized by the average of their entropies. This normalization ensures that the NMI value falls between 0 and 1, 1 indicates perfect agreement between the clusters.

The formula for NMI is:

where:

I(): Mutual information metric.

H(): Entropy metric.

P(): The predicted clustering

: The true clustering

: The true clustering

Dabies Bouldin Index (DBI)18: DBI is a metric used to evaluate how well cluster are formed. Clustering quality can be evaluated by assessing the average similarity of each cluster to its most similar neighboring cluster. It measures how well the clusters are separated and how compact they are. DBI is calculated by comparing the ratio of within-cluster dispersion to between-cluster separation for each cluster, and then averaging these ratios across all clusters.

The formula for DBI is:

where:

: The distance between vectors which are chosen as characteristic of clusters i and j.

: The distance between vectors which are chosen as characteristic of clusters i and j. : The dispersions of clusters i and j.

: The dispersions of clusters i and j.n: The number of clusters.

Variance Ration Criterion (VRC)20: VRC, also known as the Calinski-Harabasz score, evaluates the quality of clustering by comparing the dispersion between clusters to the dispersion within clusters. It is defined as the ratio of the between-group sum of squares (BGSS) to the within-group sum of squares (WGSS), adjusted for the number of clusters and data points.

The formula for VRC is:

|

where:

N: The number of data points in a given data set.

n: The number of clusters.

Silhouette score (Sil)19: Sil measures the quality of clustering by evaluating how similar each data point is to its own cluster compared to other clusters. It is calculated as the mean silhouette coefficient across the dataset, with values ranging between -1 and 1. A high silhouette score indicates that points are well-matched to their own cluster and poorly matched to neighboring clusters, which signifies better clustering. In contrast, negative values suggest that the points may be misclassified.

The formula for silhouette score is:

where:

: The average dissimilarity of

: The average dissimilarity of  to all other objects of cluster

to all other objects of cluster  .

. : The average dissimilarity from

: The average dissimilarity from  to all objects in cluster

to all objects in cluster  for

for  .

. : An individual data point within the dataset

: An individual data point within the dataset

Pairwise distance Spearman correlation

To assess how well the pairwise distances of the data was preserved after DR, we calculated the all pairwise Euclidean distances between data points in both the original and reduced-dimensional spaces. Spearman correlation coefficients were then computed between these distances to quantify the preservation of the embedding structure. A higher correlation score indicates better preservation of the original data’s global relationships in the reduced space, as described by17. These distance calculations and correlation analyses were performed using the built-in functions from version 1.13.1 of the SciPy library

Clustering performance evaluation

To evaluate the clustering accuracy of each DR method, we applied five commonly used clustering algorithms to the data projected into the reduced-dimensional space by the top five DR methods, using benchmark dataset 2 (n=120). The clustering algorithms tested were hierarchical clustering, k-means, k-medoids, HDBSCAN, and Affinity Propagation (AP). Hierarchical clustering, k-means, k-medoids, and AP were implemented using the built-in functions from the scikit-learn library, while HDBSCAN was implemented using version 0.8.38 of the hdbscan library. All clustering algorithms were run with default hyperparameter settings. For the clustering algorithms that require specifying the number of clusters (hierarchical, k-means, k-medoids, and AP), this parameter was set to 10, corresponding to the number of biological labels (representing 10 drug classes) in the dataset.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Data Curation, Validation, and Writing-Original Draft, Y.K.; Investigation and Writing-Original Draft, S.P.; Conceptualization, Supervision, and Writing-Review and Editing, H.L. and S.P.

Funding

This work has been supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. 2021R1C1C100711111, 2021R1C1C1003988, RS-2024-00432867 and RS-2024-00440285) supported by Grant number KSN1722122 from the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code to perform the analysis and generate the output reports is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/sysbiolab-ysk/Systematic-evaluation_DR).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Soyoung Park, Email: soyoung@pusan.ac.kr.

Haeseung Lee, Email: haeseung@pusan.ac.kr.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-12021-7.

References

- 1.Iorio, F., Rittman, T., Ge, H., Menden, M. & Saez-Rodriguez, J. Transcriptional data: A new gateway to drug repositioning?. Drug Discov. Today18, 350–357 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon, O.-S., Kim, W., Cha, H.-J. & Lee, H. In silico drug repositioning: From large-scale transcriptome data to therapeutics. Arch. Pharmacal Res.42, 879–889 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang, Y. et al. Dimensionality reduction by umap reinforces sample heterogeneity analysis in bulk transcriptomic data. Cell Rep.36 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Vidman, L., Källberg, D. & Rydén, P. Cluster analysis on high dimensional rna-seq data with applications to cancer research-an evaluation study. PLoS ONE14, e0219102 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park, M. et al. Kore-map 1.0: Korean medicine omics resource extension map on transcriptome data of tonifying herbal medicine.. Sci. Data11, 974 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin, H. et al. Transcriptome profiling of aged-mice ovaries administered with individual ingredients of samul-tang. Sci. Data12, 81 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb, J. et al. The connectivity map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science313, 1929–1935 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subramanian, A. et al. A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell171, 1437–1452 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon, O.-S., Kim, W., Cha, H.-J. & Lee, H. In silico drug repositioning: from large-scale transcriptome data to therapeutics. Arch. Pharmacal. Res.42, 879–889 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, M. et al. Systems pharmacology approaches in herbal medicine research: a brief review. BMB Rep.55, 417 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iorio, F. et al. Discovery of drug mode of action and drug repositioning from transcriptional responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.107, 14621–14626 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, H., Kang, S. & Kim, W. Drug repositioning for cancer therapy based on large-scale drug-induced transcriptional signatures. PLoS ONE11, e0150460 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon, O.-S. et al. Connectivity map-based drug repositioning of bortezomib to reverse the metastatic effect of galnt14 in lung cancer. Oncogene39, 4567–4580 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon, J. et al. Trim24-rip3 axis perturbation accelerates osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Ann. Rheum. Dis.79, 1635–1643 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon, E.-J. et al. In silico discovery of 5’-modified 7-deoxy-7-ethynyl-4’-thioadenosine as a haspin inhibitor and its synergistic anticancer effect with the PLK1 inhibitor. ACS Cent. Sci.9, 1140–1149 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong, S.-K. et al. Large-scale pharmacogenomics based drug discovery for itgb3 dependent chemoresistance in mesenchymal lung cancer. Mol. Cancer17, 1–7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch, F. C., Sutton, G. J., Voineagu, I. & Vafaee, F. Supervised application of internal validation measures to benchmark dimensionality reduction methods in scrna-seq data. Brief. Bioinform.22, bbab304 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies, D. L. & Bouldin, D. W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intel. 224–227 (1979). [PubMed]

- 19.Rousseeuw, P. J. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math.20, 53–65 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caliński, T. & Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods3, 1–27 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, H., Wang, Y., Rudin, C. & Browne, E. P. Towards a comprehensive evaluation of dimension reduction methods for transcriptomic data visualization. Commun. Biol.5, 719 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanju, P. Advancing dimensionality reduction for enhanced visualization and clustering in single-cell transcriptomics. J. Anal. Sci. Technol.16, 7 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-sne. Journal of machine learning research9 (2008).

- 24.Wang, J. & Novick, S. Dose-l1000: unveiling the intricate landscape of compound-induced transcriptional changes. Bioinformatics39, btad683 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooney, L. et al. Overview of systematic reviews of therapeutic ranges: methodologies and recommendations for practice. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.17, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon, K. R. et al. Visualizing structure and transitions in high-dimensional biological data. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 1482–1492 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, Y., Huang, H., Rudin, C. & Shaposhnik, Y. Understanding how dimension reduction tools work: an empirical approach to deciphering t-sne, umap, trimap, and pacmap for data visualization. J. Mach. Learn. Res.22, 1–73 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubert, L. & Arabie, P. Comparing partitions. J. Classif.2, 193–218 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strehl, A. & Ghosh, J. Cluster ensembles–a knowledge reuse framework for combining multiple partitions. J. Mach. Learn. Res.3, 583–617 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson, K. Liii. on lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. London Edinburgh Dublin Philos. Magaz. J. Sci.2, 559–572 (1901). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt, M. N., Winther, O. & Hansen, L. K. Bayesian non-negative matrix factorization. In Independent Component Analysis and Signal Separation: 8th International Conference, ICA 2009, Paraty, Brazil, March 15–18, 2009. Proceedings 8 (ed. Schmidt, M. N.) 540–547 (Springer, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spearman, C. General intelligence objectively determined and measured. Am. J. Psychol. (1961).

- 33.Dasgupta, S. Experiments with random projection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3849 (2013).

- 34.Hyvärinen, A. & Oja, E. Independent component analysis: algorithms and applications. Neural Netw.13, 411–430 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross, D. A., Lim, J., Lin, R.-S. & Yang, M.-H. Incremental learning for robust visual tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vision77, 125–141 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halko, N., Martinsson, P.-G. & Tropp, J. A. Finding structure with randomness: Probabilistic algorithms for constructing approximate matrix decompositions. SIAM Rev.53, 217–288 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zou, H., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Sparse principal component analysis. J. Comput. Graph. Stat.15, 265–286 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cichocki, A. & Phan, A.-H. Fast local algorithms for large scale nonnegative matrix and tensor factorizations. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci.92, 708–721 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, D. D. & Seung, H. S. Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature401, 788–791 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin, C.-J. Projected gradient methods for nonnegative matrix factorization. Neural Comput.19, 2756–2779 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pascual-Montano, A., Carazo, J. M., Kochi, K., Lehmann, D. & Pascual-Marqui, R. D. Nonsmooth nonnegative matrix factorization (nsnmf). IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.28, 403–415 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li, P., Hastie, T. J. & Church, K. W. Very sparse random projections. In: Proc. 12th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, 287–296 (2006).

- 43.Laurberg, H., Christensen, M. G., Plumbley, M. D., Hansen, L. K. & Jensen, S. H. Theorems on positive data: On the uniqueness of nmf. Comput. Intell. Neurosci.2008, 764206 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mnih, A. & Salakhutdinov, R. R. Probabilistic matrix factorization. Advances in neural information processing systems20 (2007).

- 45.Kim, H. & Park, H. Sparse non-negative matrix factorizations via alternating non-negativity-constrained least squares for microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics23, 1495–1502 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schölkopf, B., Smola, A. & Müller, K.-R. Kernel principal component analysis. In International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ed. Schölkopf, B.) 583–588 (Springer, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tenenbaum, J. B., Silva, Vd. & Langford, J. C. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Science290, 2319–2323 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amid, E. & Warmuth, M. K. Trimap: Large-scale dimensionality reduction using triplets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.00204 (2019).

- 49.McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03426 (2018).

- 50.Roweis, S. T. & Saul, L. K. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction by locally linear embedding. Science290, 2323–2326 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szubert, B., Cole, J. E., Monaco, C. & Drozdov, I. Structure-preserving visualisation of high dimensional single-cell datasets. Sci. Rep.9, 8914 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The source code to perform the analysis and generate the output reports is publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/sysbiolab-ysk/Systematic-evaluation_DR).