Abstract

Background

Mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and pain, are prevalent among ambulatory patients. Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions have emerged as promising approaches to improving mental health outcomes. However, their comparative effectiveness remains unclear, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

Aim

This study compares the impact of Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions on mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, and pain) for ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A quasi-expremintal study with pre and post tests were conducted with 400 participants, who were recruited through purposive sampling and assigned to receive either Nurse-Led Education or Telehealth interventions over eight weeks. Depression, anxiety, and pain were measured using the PHQ-9, STAI, and VAS tools, respectively. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, independent t-tests, logistic regression, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), with anxiety examined as a potential mediator.

Results

Both the Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth Intervention groups showed significant improvements in mental health outcomes, including reductions in depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (STAI), and pain (VAS). The Nurse-Led Education group improved from 20.3 to 12.4 in PHQ-9, while the Telehealth group decreased from 21.8 to 15.2, both with p < 0.001. Pain scores also decreased significantly in both groups, with the Nurse-Led group improving from 18.9 to 9.3 and the Telehealth group from 31.3 to 18.5 (p < 0.001). Anxiety levels decreased in both groups (p < 0.001). Regression analysis indicated that Telehealth had a stronger association with improvements across all outcomes, with anxiety playing a significant mediating role in the Telehealth group. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) further demonstrated that Telehealth had a more pronounced effect on pain management and mental health outcomes, highlighting its potential for more robust results compared to Nurse-Led Education, though both interventions proved beneficial.

Conclusion

Telehealth interventions showed superior efficacy in managing depression and pain, potentially due to individualized care. Nurse-Led Education excelled in fostering peer support, which equally benefited anxiety management. These findings highlight the importance of tailored approaches in mental health care.

Clinical trial

No clinical trial.

Keywords: Nurse-led education, Telehealth, Mental health, Depression, Anxiety, Pain, Ambulatory patients, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Mental health is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of comprehensive healthcare, particularly for patients managing chronic conditions [1–5]. In ambulatory care settings, these patients frequently encounter unique challenges that can impact their mental well-being, including the stress of managing complex treatment regimens, the burden of frequent healthcare visits, and the psychological toll of living with ongoing health concerns [6–10]. Left unaddressed, these mental health challenges—such as anxiety, depression, and stress—can diminish patients’ quality of life and negatively affect their physical health outcomes [11, 12].

In Saudi Arabia, many studies have pointed to depression and anxiety affecting one-quarter to nearly one-half ambulatory patients, and the 25–45% range for the proportion in various populations and conditions [13, 14]. Mental disorders like depression and chronic stress not only cause emotional suffering but also bear consequences for one’s medical health. To start with, high stress is linked with down-regulated immune functioning, and depressive symptomatology has been found to routinely result in poor medication adherence, poor self-care, and poor chronic disorder outcomes [15].

With an evolving healthcare landscape and growing awareness of mental health’s significance, Saudi Arabia has prioritized integrating mental health support into various levels of care. However, determining the most effective models to deliver this support, particularly in ambulatory care, remains an ongoing challenge [15–18].

Two approaches have gained traction as promising interventions to support mental health in outpatient settings: nurse-led education and telehealth. Both interventions are adaptable to ambulatory care environments and offer unique advantages, though their comparative effectiveness in the Saudi Arabian context has yet to be fully explored [19–21].

Previous studies in diverse healthcare settings have demonstrated that both nurse-led and telehealth interventions effectively reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms, although their comparative effectiveness varies. A systematic review and metaanalysis of nurseled telepsychological interventions for postpartum depression found a significant reduction in depressive symptoms compared to usual care [21]. In trials comparing nurse-delivered and mental-health-professional–delivered telehealth CBT for chronic low back pain, both approaches produced similar improvements in depressive symptoms (no significant differences) [22]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of telehealth versus inperson treatment for depression found no meaningful differences in depression severity outcomes [23].

Nurse-led education involves direct, face-to-face engagement, where nurses act as both educators and patient advocates, delivering targeted support for mental health. This model capitalizes on the therapeutic relationship between nurses and patients, creating a safe and supportive environment for discussing mental health concerns. Through structured educational sessions, nurses guide patients in understanding mental health, teach coping strategies, and provide personalized advice for managing stress [24]. Given the cultural context of Saudi Arabia, where strong interpersonal bonds are often valued in healthcare settings, nurse-led education has the potential to build trust and foster patient engagement effectively [25].

Telehealth, by contrast, leverages digital platforms to extend mental health support remotely, offering a flexible and accessible solution that minimizes the need for in-person visits. Through video calls or phone consultations, patients can connect with healthcare providers from the comfort of their homes, reducing geographical and logistical barriers to accessing care. This approach has been particularly valuable in expanding access to healthcare services for patients in remote or underserved areas, aligning well with global trends toward healthcare digitization and addressing the needs of patients who prefer convenient and flexible access to support [26]. Furthermore, telehealth facilitates frequent contact with healthcare providers, enabling regular monitoring and immediate feedback on mental health concerns, which is essential for early intervention and sustained mental well-being [27]. In a post-pandemic world, the utility of telehealth has become even more evident, making it a feasible and scalable option for supporting mental health in ambulatory care settings [28].

Despite the potential of both interventions, key differences exist between them. Nurse-led education relies heavily on the interpersonal connection established through face-to-face interactions, emphasizing a supportive, trust-based relationship that can foster open discussions on mental health. This method may be especially beneficial in a cultural context where patients value personalized, relational care, and where direct support can be instrumental in reducing stigma around mental health issues [29]. Telehealth, on the other hand, maximizes accessibility and allows patients to receive guidance at their convenience. This model may be particularly appealing for patients with busy schedules or for those who may face cultural or social barriers to seeking mental health support in person. By providing real-time support remotely, telehealth can reach patients who might otherwise forgo mental health care, offering an accessible avenue for regular mental health monitoring and guidance [30].

While both interventions hold promise, the need for culturally tailored and context-specific solutions is critical in Saudi Arabia. The healthcare system in Saudi Arabia is rapidly evolving, embracing both innovative digital solutions and traditional care models that resonate with local values. By comparing nurse-led education and telehealth interventions, healthcare providers and policymakers can better understand how each model aligns with the needs of ambulatory patients, as well as which approaches may yield the most beneficial mental health outcomes in this unique healthcare setting. Through such insights, Saudi Arabia can advance mental health integration within ambulatory care, providing patients with flexible and culturally appropriate mental health support that enhances their overall health and quality of life.

Aim

To compare the impact of Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions on mental health outcomes (including depression, anxiety, and pain) for ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia.

Research questions

How do Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions compare in terms of their effectiveness in reducing depression mean scores among ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia?

What is the comparative effect of Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions on anxiety mean scores in ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia?

To what extent do Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions impact pain management in ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia?

What are the mediating effects of anxiety in the relationship between the type of intervention (Nurse-Led Education vs. Telehealth) and mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, pain) in ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia?

Hypotheses

H1: The Telehealth intervention will result in a greater reduction in mean depression scores (as measured by the PHQ-9) compared to the Nurse-Led Education intervention among ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia.

H2: The Telehealth intervention will result in a greater reduction in mean anxiety scores (as measured by the STAI) compared to the Nurse-Led Education intervention among ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia.

H3: The Telehealth intervention will result in a greater reduction in mean pain scores (as measured by the VAS) compared to the Nurse-Led Education intervention among ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia.

H4: Anxiety will mediate the relationship between intervention type (Nurse-Led Education vs. Telehealth) and mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, and pain) among ambulatory patients in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Design

This study used a quasi expremeintal design using pre and post tests to evaluate the effectiveness of two mental health interventions—Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth Intervention. The interventions aimed to improve mental health outcomes, including anxiety and depression, through structured educational sessions. Both groups received identical content, with the primary difference being the delivery method. The study is classified as quasi-experimental because participants were not randomly assigned to intervention groups at the individual level. Instead, group allocation was based on practical and logistical considerations, such as availability and site capacity. This lack of randomization distinguishes it from a true experimental design and introduces potential for selection bias, which was mitigated through matching and baseline assessments. Quasi-experimental designs are widely used in applied health research when randomization is not feasible or ethical [31–33].

Setting

The study was conducted in a community healthcare setting, including outpatient clinics and hospital-based services located in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Participants were recruited from these settings and randomized to receive either the Nurse-Led Education intervention or the Telehealth Intervention. These institutions provided diverse patient populations, ensuring a comprehensive representation of ambulatory patients while minimizing selection bias. The inclusion of multiple healthcare facilities enhanced the external validity of the study and facilitated broader generalization of the findings to various community healthcare environments.

Sample size and sampling technique

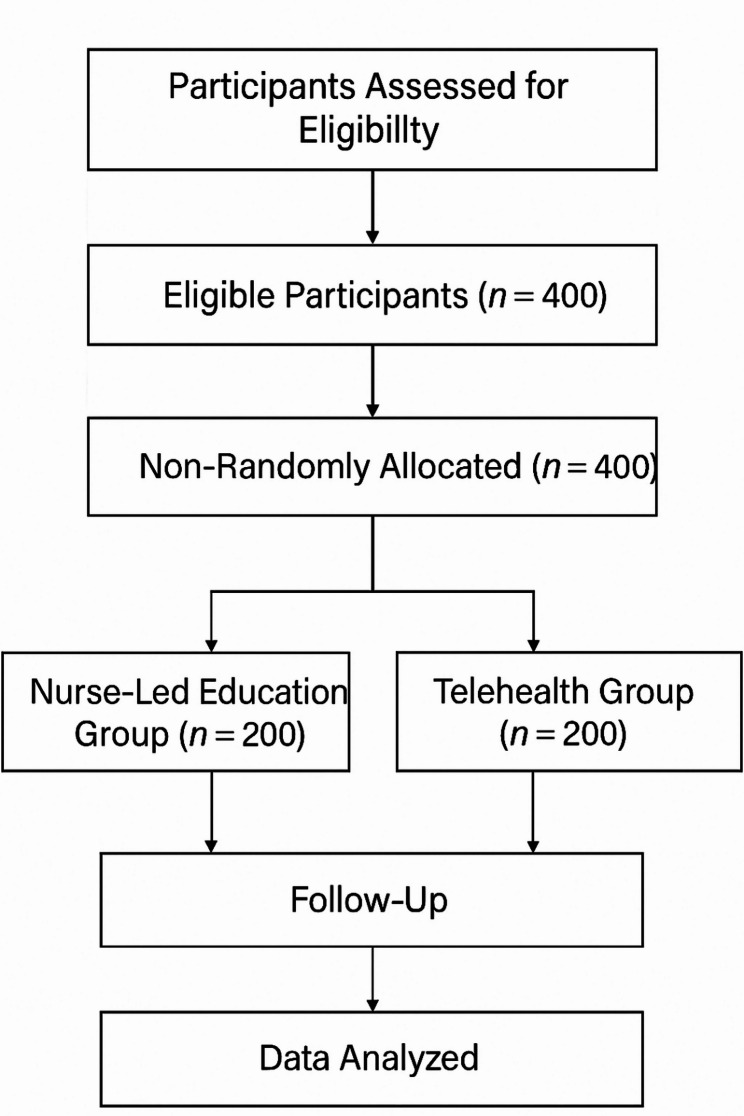

Sample size calculations using G*Power software ensured sufficient statistical power to detect meaningful differences between the two groups. With a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a significance level (α = 0.05), and statistical power (1 - β = 0.80), the initial calculation indicated a requirement of 64 participants per group, totaling 128 participants. To account for dropouts and non-responses, 20% was added, increasing the required number to 153 participants per group (306 total). An additional 30% adjustment for robust subgroup analyses and site variability resulted in a final target of 200 participants per group, or 400 participants overall. This ensures adequate power to detect statistically significant differences and supports exploratory analyses (Fig. 1). Participants were recruited using purposive sampling based on predefined eligibility criteria, and then allocated to intervention groups according to logistical feasibility and site availability. Baseline comparability between groups was assessed to minimize selection bias. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before randomization. Using computer-generated random allocation sequences, participants were assigned to either the Nurse-Led Education group or the Telehealth group, with allocation concealment maintained throughout the process. While participants were informed of their intervention allocation, they were blinded to the specific study hypotheses to mitigate bias. The study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement to ensure methodological rigor and transparency in reporting quasi-experimental research.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant selection, allocation, follow-up, and data analysis

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To participate in the study, individuals needed to meet certain eligibility requirements. First, participants were required to be adults aged between 18 and 65 years, ensuring the study focused on a specific age range for examining mental health interventions. This age group was selected to capture adults in the typical working-age range, who are often affected by mental health conditions like anxiety and depression. Additionally, participants had to have a diagnosis of moderate to severe anxiety or depression. This diagnosis was confirmed using well-established, standardized screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) for anxiety. These tools are validated instruments that reliably assess the severity of these conditions.

Another essential inclusion criterion was the ability to access a computer or smartphone with a stable internet connection. This was specifically required for participants in the Telehealth group, as the intervention would be delivered via online platforms. Ensuring that participants had the necessary technology was vital for maintaining consistent engagement with the intervention. Lastly, all participants had to be capable of providing informed consent, meaning they understood the study’s objectives, procedures, and any potential risks involved in participating.

Several exclusion criteria were set to safeguard participant well-being and ensure the integrity of the study’s results. Individuals with severe physical health conditions that could hinder their participation, such as life-threatening illnesses or uncontrolled chronic conditions, were excluded. This was to ensure that these physical health concerns would not interfere with the study’s interventions or data collection. Additionally, participants were excluded if they had severe cognitive impairment or a diagnosis of psychosis. This exclusion was made to ensure participants could understand and engage with the study’s assessments and interventions, as cognitive or psychotic disorders could impair this ability and confound study outcomes.

The study also excluded individuals currently undergoing other concurrent mental health treatments or interventions, such as psychotherapy or psychiatric medications, to avoid confounding effects on the outcomes of the intervention being studied. Finally, individuals with unstable mental health conditions or those who had recently been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons were excluded. The exclusion of these participants was to ensure that the study did not inadvertently interfere with the management of more severe mental health issues and to reduce the risk of exacerbating symptoms during participation in the study.

Measure tools

Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was developed by Kroenke et al. [34] to measure depression severity. It comprised nine items aligned with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for depression and was used to assess the frequency of symptoms experienced by individuals over the preceding two weeks. Each item is scored from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 27. Scores are interpreted as follows: 0–4 (minimal), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (moderately severe), and 20–27 (severe depression). Higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms. With its strong validity and reliability, the PHQ-9 has become a widely used instrument in clinical practice and research settings for diagnosing and monitoring depression. Internal consistency coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.89 underscore its reliability, making it an invaluable tool for assessing changes in depression severity over time and informing treatment decisions [34]. In this study, the total mean score derived from the PHQ-9 assessments served as a key outcome measure, enabling the comparison of depression severity between intervention groups and guiding the development of tailored treatment plans.

Visual analog scale (VAS)

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS), introduced by Huskisson [35] as a tool for pain measurement, has evolved into a versatile instrument widely utilised in clinical assessment and research. Initially devised for pain assessment, the VAS has expanded its application to encompass subjective experiences such as mood and overall well-being. It comprises a 10-centimetre line anchored by verbal descriptors at each end, enabling patients to indicate their symptom intensity by marking a point along the line. The VAS has demonstrated good validity in assessing subjective experiences, contributing to its widespread adoption in clinical settings. Moreover, with a reliability coefficient of 0.88, the VAS consistently measures subjective experiences over time and across different contexts, enhancing its credibility and utility in clinical practice and research. In clinical research and practice, the total mean score derived from the VAS served as a pivotal indicator of overall symptom severity or well-being across various domains. By aggregating individual scores, researchers and healthcare providers gain insight into the average intensity of symptoms experienced by patients within a given population, enabling comparisons between groups or individuals. Furthermore, changes in the total mean score pre- and post-intervention offer valuable insights into the effectiveness of treatments or interventions to improve patient outcomes [35].

State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI)

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a tool developed to evaluate anxiety levels, as detailed in Spielberger, et al. [36]. It delineates between state anxiety, reflecting current feelings, and trait anxiety, representing a general tendency to experience anxiety. The STAI’s effectiveness in assessing anxiety levels is supported by its good validity and high reliability, with internal consistency coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.95. In clinical and research contexts, total mean scores derived from the STAI are crucial indicators of overall anxiety severity across state and trait domains. Each subscale (State and Trait) consists of 20 items, with total scores ranging from 20 to 80, where higher scores indicate greater anxiety (Spielberger et al., 1983). Scores above 40 are generally considered to reflect moderate to high anxiety, and a reduction of 10 points or more is often regarded as clinically meaningful in intervention studies [37].

By aggregating individual scores from each scale, practitioners and researchers gain insight into the average intensity of anxiety experienced within a population, enabling comparisons between groups or individuals and providing a concise summary of anxiety symptom burden. Moreover, changes in total mean scores pre- and post-intervention offer valuable insights into treatment effectiveness, aiding in refining anxiety management strategies. Data collection was conducted by trained research assistants who were not involved in delivering the interventions. However, blinding was not feasible, and assessors were aware of group assignments during data collection.

Intervention design and implementation

Both the Nurse-Led Education and the Telehealth programs were designed to improve mental health outcomes related to anxiety and depression. Each intervention focused on equipping participants with coping strategies, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques, stress management skills, and mental health education. Notably, both interventions followed the same session structure to ensure consistency and comparable outcomes. Each program consisted of 8 sessions held once per week over a total duration of 8 weeks, with each session lasting 60 min. The standardized structure of the sessions was as follows ( Table 1):

Table 1.

Weekly intervention sessions with corresponding therapeutic objectives and techniques

| Week | Session Theme | Therapeutic Techniques Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Mental Health and Coping | Psychoeducation on mental health; discussion of personal stressors; introduction to coping models |

| 2 | Stress Management Techniques | Breathing exercises; progressive muscle relaxation; identifying stress triggers |

| 3 | CBT Techniques | ABC model (Activating event, Belief, Consequence); cognitive restructuring |

| 4 | Challenging Negative Thoughts | Thought record exercises; guided questioning; reframing automatic negative thoughts |

| 5 | Building Resilience and Self-Efficacy | Goal setting; positive self-talk; solution-focused strategies |

| 6 | Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques | Mindfulness breathing; body scan meditation; guided imagery |

| 7 | Managing Anxiety and Depression | Behavioral activation; emotion regulation strategies; mood monitoring |

| 8 | Maintaining Mental Health Post-Intervention | Relapse prevention planning; review of learned strategies; development of personal wellness plan |

Nurse-Led Education

The Nurse-Led Education program was delivered in a group format with a maximum of 10 participants per session. This setup promoted peer support, shared experiences, and interactive discussions. The sessions were designed to provide individualized attention while benefiting from the collective insights of the group. The group dynamic was central to fostering a supportive environment for participants to engage actively in discussions and learning.

Telehealth intervention

The Telehealth program offered the same content as the group intervention but was delivered in an individualized format through secure, HIPAA-compliant platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams. It was conducted over 8 weeks, with one 60-minute session per week, mirroring the schedule of the Nurse-Led Education program. This format allowed nurses to tailor the sessions to each participant’s unique needs, providing personalized feedback and adjusting the content based on individual progress.

Nurse training and consistency across interventions

The same team of nurses facilitated both interventions, ensuring a consistent approach and quality of delivery. These nurses underwent standardized training to gain expertise in CBT techniques, stress management, mindfulness, and patient engagement. The training emphasized adaptability, enabling the nurses to effectively deliver content in both group and individual settings while maintaining alignment with the standardized curriculum. This dual-format intervention strategy ensured flexibility while maintaining uniformity in the core content and goals, enabling a comprehensive approach to improving mental health outcomes for participants.

Ethical issues and approval

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for approval on an ethics committee opinion Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (approval number: SCBR-260/2024) prior to its commencement. Administrative approval was also obtained from the participating healthcare facilities before data collection began. The study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits were explained to participants, and informed consent was obtained before their involvement. Confidentiality was ensured through strict privacy measures, and data collection was conducted in compliance with relevant regulations and ethical standards. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. The research team maintained transparency and integrity throughout the study, upholding ethical principles to ensure trust in the research process.

Data analysis

In this study, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was used for various statistical analyses, including descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies), independent t-tests to compare the means between the Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth Intervention groups, and logistic regression to identify predictors of mental health outcomes (PHQ-9, VAS, and STAI scores). Mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro (Version 4.0) by Andrew Hayes to explore the indirect effects of anxiety on the relationship between the intervention and mental health outcomes. Additionally, Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) version 28, was used to perform Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to assess the direct and indirect effects between variables. Specifically, Multi-Group SEM was conducted to compare the pathways in the Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth Intervention groups, and to examine the mediating role of anxiety on the outcomes of interest. These advanced statistical methods facilitated a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the interventions, mediators, and mental health outcomes.

Results

Table 2: The demographic characteristics of the Nurse-Led Education group (n = 200) and the Telehealth Intervention group (n = 200) reveal notable differences. The mean age in the Nurse-Led Education group was 45 ± 10 years, slightly older than the Telehealth group at 43 ± 9 years. Gender distribution showed a higher proportion of females in both groups, with 60% in the Nurse-Led group and 65% in the Telehealth group. Educational levels were higher in the Telehealth group, with 40% having a high level of education compared to 30% in the Nurse-Led group. Employment status revealed 75% employment in the Telehealth group versus 70% in the Nurse-Led group. Additionally, income levels showed that 70% of participants in the Telehealth group reported insufficient income, compared to 60% in the Nurse-Led group. Previous awareness of evidence-based interventions was higher in the Telehealth group (25%) than in the Nurse-Led group (15%).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics in Nurse-Led education group (n = 200) and telehealth intervention group (n = 200)

| Characteristics | Nurse-Led Education Group (n = 200) | Telehealth Intervention Group (n = 200) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 45 ± 10 | 43 ± 9 |

|

Gender Male Female |

80 (40%) 120 (60%) |

70 (35%) 130 (75%) |

|

Educational level Low Moderate High |

40 (20%) 100 (50%) 60 (30%) |

30 (15%) 90 (45%) 80 (40%) |

|

Employment Status Employed Unemployed |

140 (70%) 60 (30%) |

150 (75%) 50 (25%) |

|

Income Enough Not enough |

80 (40%) 120 (60%) |

60 (30%) 140 (70%) |

|

Previous Evidence-Based Nurse-Led Education Vs Telehealth Interventions Awareness Yes No |

30 (15%) 170 (85%) |

50 (25%) 150 (75%) |

N.B. Educational levels defined as low (≤ 8 years), moderate (9–12 years), high (≥ 13 years); income categorized as enough (meets living wage) or not enough (below living wage); mental health status includes anxiety and depression; previous awareness indicates prior knowledge of interventions

The results in Table 3 demonstrate significant improvements in the PHQ-9 scores for both the Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth Intervention groups following the intervention. In the Nurse-Led Education group, the mean score decreased from 20.3 ± 4.7 pre-intervention to 12.4 ± 3.2 post-intervention, with a highly significant difference (p < 0.001). Similarly, the Telehealth Intervention group showed a reduction in the mean score from 21.8 ± 5.2 to 15.2 ± 4.1, also with a significant p-value (p < 0.001). These findings suggest that both interventions had a positive impact on reducing depressive symptoms in patients, with the Telehealth group showing a slightly higher pre-intervention score, but both groups benefiting equally from the interventions.

Table 3.

Patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores in Nurse-Led education and telehealth intervention groups (Pre and post intervention)

| Intervention Group | Pre-Intervention PHQ-9 Score (Mean ± SD) | Post-Intervention PHQ-9 Score (Mean ± SD) | Test Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse-Led Education | 20.3 ± 4.7 | 12.4 ± 3.2 | 3.82 | < 0.001 |

| Telehealth Intervention | 21.8 ± 5.2 | 15.2 ± 4.1 | 4.19 | < 0.001 |

Table 4 highlights the significant reduction in pain scores as measured by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) in both intervention groups. The Nurse-Led Education group experienced a notable decrease in mean VAS scores from 18.9 ± 15.2 pre-intervention to 9.3 ± 5.1 post-intervention, with a test value of 11.6 and p-value < 0.001. The Telehealth Intervention group also showed improvement, with mean scores dropping from 31.3 ± 6.08 to 18.5 ± 4.3, achieving a similar significant result (p < 0.001). These findings underscore the effectiveness of both interventions in managing pain, with Telehealth showing higher pre-intervention pain scores but similar post-intervention outcomes, demonstrating the efficacy of both approaches.

Table 4.

Visual analog scale (VAS) scores in Nurse-Led education and telehealth intervention groups (Pre and post intervention)

| Intervention Group | Pre-Intervention VAS Score (Mean ± SD) | Post-Intervention VAS Score (Mean ± SD) | Test Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse-Led Education | 18.9 ± 15.2 | 9.3 ± 5.1 | 11.6 | < 0.001 |

| Telehealth Intervention | 31.3 ± 6.08 | 18.5 ± 4.3 | 12.7 | < 0.001 |

According to Table 5, both Nurse-Led Education and Telehealth interventions led to significant reductions in anxiety levels, as measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The Nurse-Led Education group’s mean STAI score decreased from 52.3 ± 5.2 pre-intervention to 42.3 ± 4.5 post-intervention (p < 0.001), while the Telehealth Intervention group’s score reduced from 51.8 ± 5.0 to 45.4 ± 4.1 (p < 0.001). These findings indicate that both interventions were highly effective in reducing anxiety levels, with a slight difference in the pre-intervention scores. However, both groups achieved similar post-intervention improvements, emphasizing the potential for both intervention types in managing anxiety.

Table 5.

Anxiety (STAI) scores in Nurse-Led education and telehealth intervention groups (Pre and post intervention)

| Intervention Group | Pre-Intervention STAI Score (Mean ± SD) | Post-Intervention STAI Score (Mean ± SD) | Test Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse-Led Education | 52.3 ± 5.2 | 42.3 ± 4.5 | 9.7 | < 0.001 |

| Telehealth Intervention | 51.8 ± 5.0 | 45.4 ± 4.1 | 9.9 | < 0.001 |

Table 6 presents a regression analysis of several predictors for changes in the PHQ-9, VAS, and STAI scores. Notably, the Telehealth intervention was significantly associated with improvements across all outcomes, with coefficients of 0.75 for PHQ-9, 0.91 for VAS, and 0.88 for STAI, all of which were statistically significant (p-values < 0.05). The education level (moderate) and unemployment status were also significant predictors, with coefficients indicating that moderate education and being unemployed were associated with better outcomes across all measures. However, income and previous awareness had no significant impact on these outcomes, suggesting that factors such as intervention type and education level may play more critical roles in improving mental health, pain, and anxiety outcomes.

Table 6.

Predictors of changes in PHQ-9, VAS, and STAI scores

| Predictor Variable | PHQ-9 Coefficient | PHQ-9 Odds Ratio | P-Value | VAS Coefficient | VAS Odds Ratio | P-Value | STAI Coefficient | STAI Odds Ratio | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (Telehealth) | 0.75 | 2.12 | 0.004 | 0.91 | 2.49 | 0.002 | 0.88 | 2.41 | 0.001 |

| Education (Moderate) | 0.45 | 1.57 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 1.65 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 1.49 | 0.03 |

| Employment (Unemployed) | 0.63 | 1.88 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 2.05 | 0.007 | 0.65 | 1.92 | 0.009 |

| Income (Not Enough) | 0.28 | 1.32 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 1.42 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 1.38 | 0.16 |

| Previous Awareness (No) | 0.52 | 1.68 | 0.02 | 0.58 | 1.79 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 1.73 | 0.00 |

The mediation analysis results in Table 7 show that anxiety served as a significant mediator in the relationship between the intervention and outcomes. For the Telehealth intervention, anxiety had a significant indirect effect on the reduction of PHQ-9 scores (coefficient = -0.18, p < 0.001), suggesting that the reduction in anxiety contributed to improvements in depressive symptoms. Similarly, anxiety mediated the relationship between the intervention and VAS and STAI scores. The total effect of Telehealth on PHQ-9, VAS, and STAI scores was also significant (p < 0.001 for all), highlighting the key role of anxiety reduction in enhancing overall outcomes. The moderate education group also showed some mediation effects, but to a lesser extent, particularly in reducing PHQ-9 scores.

Table 7.

Mediation analysis results for intervention effects on PHQ-9, VAS, and STAI scores (Using anxiety as the Mediator)

| Predictor Variable | Mediator (Anxiety) Coefficient | Outcome (PHQ-9) Coefficient | Indirect Effect (Anxiety → PHQ-9) | P-Value for Indirect Effect | Total Effect (Intervention → Outcome) | P-Value for Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (Telehealth) | 0.35 | -0.52 | -0.18 | < 0.001 | -0.75 | < 0.001 |

| Education (Moderate) | 0.30 | -0.45 | -0.13 | 0.02 | -0.45 | 0.03 |

In Table 8, the multi-group Structural Equation Model (SEM) reveals that both interventions produced significant effects on the outcomes, with some differences between groups. The Nurse-Led Education group showed slightly smaller effects on PHQ-9, VAS, and STAI scores compared to the Telehealth group, although the differences between groups were not always statistically significant. Specifically, the effect of the intervention on VAS scores was significantly stronger in the Telehealth group (coefficient = -0.65) compared to the Nurse-Led Education group (coefficient = -0.43), with a p-value of 0.05. Anxiety served as a significant mediator in both groups, with the Telehealth group showing a stronger mediation effect for PHQ-9 and VAS outcomes (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that Telehealth may offer more robust effects in managing pain and mental health symptoms, although both interventions proved beneficial across all outcomes.

Table 8.

Multi-Group structural equation model (SEM) for Nurse-Led education and telehealth intervention groups

| Path | Nurse-Led Education (Coefficient) | Telehealth Intervention (Coefficient) | Difference Between Groups (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention → PHQ-9 | -0.55 | -0.72 | 0.12 |

| Intervention → VAS | -0.43 | -0.65 | 0.05 |

| Intervention → STAI | -0.39 | -0.60 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety → PHQ-9 (Mediator) | -0.32 | -0.45 | 0.04 |

| Anxiety → VAS (Mediator) | -0.29 | -0.41 | 0.02 |

| Anxiety → STAI (Mediator) | -0.26 | -0.38 | 0.01 |

Discussion

The demographic data demonstrate a well-matched distribution between the intervention groups, ensuring a robust foundation for comparing outcomes. Both groups were predominantly female, aligning with broader population trends in studies involving these health issues.The slight differences in education levels and prior awareness suggest potential influences on how participants engaged with the interventions, which could impact their outcomes. However, these differences did not significantly skew the comparability of the groups. This balance supports the reliability of attributing observed differences in outcomes to the intervention type rather than baseline disparities.

Both Telehealth and Nurse-Led Education significantly reduced depression symptoms, with Telehealth showing a greater reduction. This could be attributed to the personalized and accessible nature of Telehealth, which provides ongoing support and flexibility for patients. This finding was highly supported by Fortney, et al. [38], concluded that better results in the care for depression may be obtained by hiring an off-site telemedicine-based collaborative care team rather than using practice-based collaborative care with staff members who are available locally. The metanalysis conducted by Luo, et al. [39] demonstated that patients who get electronic cognitive behavioral treatment report less severe symptoms of depression than those who receive face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy. The results are not conclusive, though, because of things like the possibility of bias, the wide range of outcomes, and the lack of obvious variations in the approaches’ global functionality.Since technology is so widely available, electronic cognitive behavioral therapy ought to be seen as a good choice, especially if it fits the preferences of both the patient and the therapist to address a range of medical demands.

In the same context; other study showed that Telehealth is the most effective method for addressing depression among veterans. Even with greater upfront expenditures, telemedicine results in equivalent quality-adjusted life years to in-person care and reduced health usage costs after a year. According to this, telehealth is a cost-effective substitute for in-person therapy and can save a substantial amount of money by lowering the need for healthcare services after the intervention [40]. Furthermore, Milosevic et al. [41] found that group cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) via videoconference is a very promising and successful substitute for in-person CBT for anxiety and related illnesses. According to Walton et al. [42], Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) administered via telehealth may be a useful substitute for in-person sessions, with comparable attendance rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. This demonstrates how telehealth, especially in poor locations, might expand access to DBT. The study also shows that telehealth has no detrimental effect on attendance rates, which suggests that it can be a useful therapy option.

Furthermore, Giovanetti et al. [43] found that video-based teletherapy could be a practical and successful substitute for in-person services in lowering depressed symptoms. A greater understanding of the access constraints associated with each delivery medium and more study on the efficacy of telehealth in clinically depressed samples can aid the field in identifying which patients will benefit most from each intervention method. According to Scott et al. [44], real-time telemedicine is a good substitute for in-person therapy for patients with major depressive illness. With the exception of a little improvement in depression at nine months after telemedicine treatment, there were no appreciable changes in the degree of depression, treatment satisfaction, or therapeutic alliance between telehealth and in-person care. In order to further prove the effectiveness of telehealth, the study recommends more trials with longer follow-up, carried out in a wider range of settings, and with younger patients, even though the results are encouraging.

Other studies such as; Greenwood, et al. [45], found that there is not enough evidence to support the idea that telehealth psychotherapy differs from in-person psychotherapy in terms of effectively treating less common mental health conditions and physical conditions that require psychological support. Likewise, Krzyzaniak et al. [46] reported Telehealth-delivered treatment seems to be just as beneficial as in-person therapy in terms of outcomes pertaining to anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depressive symptom intensity, function, working alliance, and satisfaction. Furthermore, Scott et al. [23] found no distinctions between telemedicine and in-person treatment for the severity of depression caused by posttraumatic stress disorder. In a similar vein, Lalor et al. [47] reported that all forms of short psychological interventions, including telehealth and in-person sessions, equally decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms at the conclusion of therapy. The effectiveness and service user dropout rates of the various intervention modalities did not differ significantly. Furthermore, Stiles-Shields et al. [48] found that determinants of treatment results for depression using cognitive behavioral therapy are comparable in both in-person and telephone settings.

Pain management outcomes reveal that Telehealth interventions yielded greater reductions in pain levels compared to Nurse-Led Education. This superior performance may stem from Telehealth’s ability to provide real-time feedback and adjustments based on patient-reported symptoms. This finding was highly agreed by Xiao & Han [49] and Tahsin et al. [50] have investigated the efficacy of telehealth therapies in enhancing subjective well-being, with encouraging findings. These studies offer important new information about the potential benefits of telehealth modalities for improving subjective well-being in a range of patient populations. According to Sánchez-Gutiérrez et al. [51], telemedicine and telelhealth PIs are a secure and practical choice for the clinical management of individuals with chronic illnesses. In order to evaluate the quality of life, morbidity, and mortality of chronic physical and mental diseases, future longitudinal studies are required. Additionally, Snoswell, et al. [52] demonstrated that telehealth can be equivalent or more clinically effective when compared to usual care regarding pain manangment or reduction. On the other hand; Bellanti, et al. [53] concluded that; based on evidence from 22 RCTs, the use of telehelth platforms, including video conference and telephone modalities, generally produces similar outcomes as face-to-face provision of psychotherapy and psychiatry services.

Both interventions demonstrated substantial reductions in anxiety levels, with comparable outcomes between the groups. Telehealth’s continuous access to support likely provides a sense of reassurance for patients, which could explain its effectiveness in anxiety management. The study conducted by Rabner, et al. [54] & Stubbings, et al. [55], concluded that findings support that Cogntive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) administered via telehealth is similarly efficacious as CBT administered in-person for youth with anxiety. In the same vein, Axelsson, et al. [56], demonstated that internet-delivered CBT appeared to be noninferior to face-to-face CBT for health anxiety, while incurring lower net societal costs.

The online treatment format has potential to increase access to evidence-based treatment for health anxiety. Additionally, Van der Merwe, et al. [57] revaled that, Telehealth holds promise for psychiatric assessments, especially when in-person evaluations are not feasible.Furthermore, Berryhill, et al. [58] & Krzyzaniak, et al. [46], indicated that there is some evidence of equivalence between telehealth through videoconferencing and face-to-face care for anxiety. According to Irvine et al. [59], the review found 15 research that examined the interactional features of telephone and in-person psychological therapy with regard to anxiety using contextual, comparative techniques. In terms of therapeutic connection, disclosure, empathy, attentiveness, or engagement, these research showed minimal differences between approaches. However, compared to in-person therapy sessions, telephone therapy sessions were noticeably shorter.

The logistic regression analysis highlights Telehealth as a stronger predictor of positive outcomes across all measures. Its higher odds ratios for depression, pain, and anxiety reflect its effectiveness in addressing a range of symptoms. The structured nature of Nurse-Led Education also shows predictive value, particularly in environments where digital tools are unavailable. However, the versatility and adaptability of Telehealth make it particularly effective in diverse healthcare settings, offering an edge in comprehensive symptom management. This aligns with findings from Horwitz et al. [60] found significant improvements in depression and anxiety using digital mental health interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness tools, demonstrating telehealth’s capability to support diverse mental health need.

Similarly, Gonsalves et al. [61] showed that telehealth significantly improved pain management, with patients reporting reduced pain scores and enhanced functionality. Additionally, the meta-analysis by Shore et al. [62] & Yang, et al. [63], emphasized Telehealth interventions significantly improved anxiety and depression levels in patients compared to traditional care interventions.

Anxiety reduction emerged as a significant mediator in the relationship between intervention type and outcomes, particularly in the Telehealth group, highlighting the interconnected nature of psychological and physical symptoms. Oliva [64] found similar mediation effects, where anxiety reductions improved both depression and pain outcomes. This was also observed in the Nurse-Led Education group, though to a lesser extent, emphasizing the critical role of addressing anxiety in both intervention types. The SEM analysis confirmed stronger mediation effects in the Telehealth group, underscoring its effectiveness in managing interconnected health challenges. This aligns with Waugh et al. [65], who highlighted Telehealth’s ability to provide continuous, personalized care that addresses both physical and psychological needs. While Nurse-Led Education also showed mediation effects, its impact was greatest in settings that fostered direct, trusting interactions.

Limitations of the study

A notable limitation of this study is the reliance on self-reported measures (PHQ-9, STAI, and VAS) for assessing mental health outcomes, which may introduce bias due to participants’ subjective interpretations or social desirability tendencies. Additionally, the study was conducted within specific healthcare settings in Saudi Arabia, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to broader populations or other cultural contexts. Another constraint was the requirement for participants in the Telehealth group to have access to reliable internet and devices, which may have excluded individuals with limited digital literacy or technological access.

Additionally, A unique aspect of this study is the complete retention of participants across both intervention groups, with no reported dropouts. While this may seem uncommon, several factors likely contributed: the short 8-week duration, high participant motivation due to mental health relevance, flexible scheduling (especially for Telehealth), and consistent nurse follow-up. Additionally, reminder messages and structured engagement strategies were employed to support participation. Nevertheless, the absence of attrition should be interpreted cautiously, and future studies with longer follow-up periods may better assess sustained engagement and potential dropout trends. Finally, although the study ensured consistency in intervention delivery, individual variations in nurse facilitation styles and participant engagement levels could have influenced the outcomes, warranting cautious interpretation of the results.

Conclusion

Both interventions proved effective, but Telehealth consistently outperformed Nurse-Led Education across several key outcomes, particularly in managing pain and depression. Its adaptability, accessibility, and ability to provide continuous support make it a versatile option for diverse populations. Nurse-Led Education remains a valuable approach, particularly for individuals preferring direct interaction or those in settings without digital access. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring interventions to patient preferences and needs, ensuring both physical and psychological symptoms are effectively addressed.

Implications of the study

The findings of this study have profound implications for nursing practice and health policy, especially in the realm of mental health care delivery and the integration of telehealth services. Nurses are uniquely positioned to act as front-line providers of mental health interventions, and this study emphasizes the importance of investing in their training and professional development. Comprehensive education in cognitive-behavioral techniques, patient engagement, and the effective use of telehealth technologies is essential for nurses to adapt to innovative care delivery models. By equipping nurses with these competencies, they can foster stronger therapeutic relationships and provide personalized care that meets patients’ individual needs.

The integration of telehealth interventions into mental health care frameworks has the potential to revolutionize service delivery. Telehealth eliminates many barriers associated with traditional group-based approaches, including geographic distance, transportation issues, and scheduling conflicts. It enables patients, especially those in rural or underserved areas, to access mental health services without the constraints of physical proximity to care centers. Moreover, the ability to participate in sessions from the comfort of their own homes can enhance privacy and reduce stigma, allowing patients to engage more fully and discuss sensitive issues with confidence.

From a policy perspective, there is a need to expand telehealth infrastructure to accommodate the growing demand for digital health solutions. This includes investments in secure, user-friendly platforms that protect patient confidentiality and meet regulatory standards. Policymakers must also address disparities in digital equity by ensuring access to necessary devices, internet connectivity, and digital literacy training for vulnerable populations. Bridging this digital divide is critical to ensuring that telehealth benefits are distributed equitably across different demographic and socioeconomic groups.

Additionally, health policy should focus on creating sustainable funding models to support telehealth services and the training of healthcare professionals. Financial incentives or reimbursements for telehealth consultations can encourage wider adoption of these services among providers and patients. Policies should also emphasize workforce development, ensuring that nurses and other healthcare providers receive ongoing training to keep pace with technological advancements and the evolving needs of mental health care.

Incorporating telehealth into mental health services aligns with broader public health goals of improving accessibility, equity, and outcomes. The evidence presented in this study highlights the critical role nurses play in both traditional and telehealth-based mental health care delivery, further emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and robust support systems. Policymakers, educators, and healthcare leaders must work together to develop strategies that integrate telehealth seamlessly into mental health frameworks, ensuring that these innovations are both effective and sustainable in the long term.

Also, the reductions in depression and anxiety in both intervention groups have broader implications for physical health. Increased psychological well-being has been shown to positively impact physical health by boosting immune functioning, reducing inflammation, and resulting in better medication adherence and lifestyle choices. Such changes can also assist in enhanced control of chronic disease and decreased rates of hospitalization, particularly in outpatient settings where continuity of care is most crucial. Thus, incorporating brief, formalized mental health interventions like those examined in this research study could significantly enhance overall ambulatory care efficiency.

Recommendations

Based on the study findings, it is recommended that healthcare systems integrate telehealth into routine mental health care to enhance accessibility and personalization of services, particularly for individuals in remote or underserved areas. Policymakers should prioritize investments in digital infrastructure and ensure equitable access to technology, addressing barriers such as internet connectivity and digital literacy. Furthermore, nurse training programs should include modules on delivering telehealth interventions, emphasizing skills in virtual communication, privacy management, and adaptability to individual patient needs. Future research should explore the long-term sustainability and cost-effectiveness of telehealth interventions and investigate their impact across diverse populations and cultural settings. Additionally, hybrid models combining the strengths of group-based and telehealth formats could be developed and evaluated to optimize mental health outcomes while catering to varied patient preferences.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the ambulatory patients who participated in this study. We also extend our appreciation to the nursing staff and administrative teams in the participating healthcare facilities in Saudi Arabia for their support and cooperation during the data collection process.

Abbreviations

- AMOS

Analysis of Moment Structures

- CBT

Cognitive–Behavioural Therapy

- DBT

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SEM

Structural Equation Modelling

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- STAI

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory

- TREND

Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs

- VAS

Visual Analogue Scale

Author contributions

A.I. conducted data analyses, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. D.Z. contributed to the study design and data collection. A.I. also assisted with data interpretation and manuscript drafting. D.Z. provided critical revisions and contributed to the final approval of the manuscript. A.I. participated in the study design and coordination, while D.Z. supported data collection and analysis. R.S. contributed to refining the methodology and assisted in statistical validation. H.M. participated in the critical review of literature and supported the revision of the discussion section. F.H. contributed to editing the manuscript for clarity, helped align the manuscript with journal guidelines, and supported referencing and formatting.

Funding

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446). The authors grate fully acknowledge the approval and the support of this research study by the grant No. (NBU-FFR-2025.685-02) from the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for approval on an ethics committee opinion Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (approval number: SCBR-260/2024) prior to its commencement. All participants were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to their enrollment in the study. Furthernmore, all Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. The research team maintained transparency and integrity throughout the study, upholding ethical principles to ensure trust in the research process.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ateya Megahed Ibrahim, Email: ateyamegahed@yahoo.com.

Heba Ahmed Osman Mohamed, Email: heba.mohmmed@nbu.edu.sa.

References

- 1.Abdul S, Adeghe EP, Adegoke BO, Adegoke AA, Udedeh EH. Mental health management in healthcare organizations: challenges and strategies-a review. Int Med Sci Res J. 2024;4(5):585–605. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akram M. Mental health public policies. Clin Onco. 2024;7(12):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertolín-Guillén JM. Ideology, scientism and mental health. Psychiatry Behav Health. Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Science Excel. 2024;3(1):1–7.

- 4.Nyame P. Holistic healthcare: bridging the gap with primary mental health care. 2024.

- 5.Odilibe IP, Akomolafe O, Arowoogun JO, Anyanwu EC, Onwumere C, Ogugua JO. Mental health policies: a comparative review between the USA and African nations. Int Med Sci Res J. 2024;4(2):141–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn-Horst RY, Bourgeois FT. Mental Health–Related outpatient visits among adolescents and young adults, 2006–2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e241468–241468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhary A, Jasrotia A, Kumar A. Mental health: a stigma and neglected public health issue and time to break the barrier. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2024;11(3):1378. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain K, Kumar T. Advancing mental health care: integrating wellbeing through a patient-centric approach. opportunities and risks in AI for business development: volume 2. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. 2024. 213–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramírez Ramos LM. Health challenges in african countries: a focus on physical, mental, and emotional well-being. 2024.

- 10.Talib A, Ijaz A. Psychological Well-Being of caregivers of parents with mental illness: an exploratory study. Appl Psychol Rev. 2024;3(1).

- 11.David D, Lassell RK, Mazor M, Brody AA, Schulman-Green D. I have a Lotta sad Feelin’–Unaddressed mental health needs and self-support strategies in medicaid-funded assisted living. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023;24(6):833–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohls JK, König HH, Quirke E, Hajek A. Anxiety, depression and quality of life—a systematic review of evidence from longitudinal observational studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Khathami AD, Ogbeide DO. Prevalence of mental illness among Saudi adult primary-care patients in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2002;23(6):721–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AlHadi AN, Almutlaq MI, Almohawes MK, Shadid AM, Alangari AA. Prevalence and treatment preference of burnout, depression, and anxiety among mental health professionals in Saudi Arabia. J Nat Sci Med. 2022;5(1):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adroa Afiya B. Interconnection between depressive disorders and persistent diseases. Res Invention J Res Med Sci. 2024;3(1):45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alattar N, Felton A, Stickley T. Mental health and stigma in Saudi arabia: a scoping review. Mental Health Rev J. 2021;26(2):180–96. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alyousef SM, Alhamidi SA. Nursing student perspectives on improving mental health support services at university in Saudi Arabia–a qualitative study. J Mental Health. 2024;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Hawsawi T, Appleton J, Al-Adah R, Al‐Mutairy A, Sinclair P, Wilson A. Mental health recovery in a collectivist society: Saudi consumers, carers and nurses’ shared perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing; 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Uraif A. Developing healthcare infrastructure in Saudi Arabia using smart technologies: challenges and opportunities. Commun Netw. 2024;16(3):51–73. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Happell B, Furness T, Jacob A, Stimson A, Curtis J, Watkins A, et al. Nurse-led physical health interventions for people with mental illness: a scoping review of international literature. Issues in mental health nursing. 2023;44(6),458–473. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Luo T, Zhang Z, Li J, Li Y, Xiao W, Zhou Y, et al. Efficacy of Nurse-led telepsychological intervention for patients with postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alpha Psychiatry. 2024;25(3):304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Gannon J, Atkinson JH, Chircop-Rollick T, D’Andrea J, Garfin S, Patel S, et al. Rutledge, T. Telehealth therapy effects of nurses and mental health professionals from 2 randomized controlled trials for chronic back pain. The Clinical journal of pain. 2019;35(4):295–303. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Scott AM, Clark J, Greenwood H, Krzyzaniak N, Cardona M, Peiris R, et al. Telehealth v. face-to-face provision of care to patients with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine. 2022;52(14):2852–2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Pouresmail Z, Nabavi FH, Rassouli M. The development of practice standards for patient education in nurse-led clinics: a mixed-method study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alshammari M, Duff J, Guilhermino M. Barriers to nurse–patient communication in Saudi arabia: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Practitioners: JNP. 2021;17(2):218–21. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohannessian R, Scardoni A, Bellini L, Salvati S, Amerio A, Odone A. Telemedicine and mental health: coming of age? Eur J Pub Health. 2020;30(Supplement5):ckaa165–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyllon M, Barnes JB, Daukas K, Fair M, Nordberg SS. The impact of the Covid-19-Related transition to telehealth on visit adherence in mental health care: an interrupted time series study. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2022;49(3):453–62. 10.1007/s10488-021-01175-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emerson MR, Huber M, Mathews TL, Kupzyk K, Walsh M, Walker J. Improving integrated mental health care through an advanced practice registered nurse–led program: challenges and successes. Public Health Rep. 2023;138(1suppl):S22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ezeamii VC, Okobi OE, Wambai-Sani H, Perera GS, Zaynieva S, Okonkwo C. C, et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: how telemedicine is improving patient outcomes and expanding access to care. Cureus. 2024;16(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, Furuno JP, Zhu J, Peterson DE, Finkelstein J. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(1):16–23. 10.1197/jamia.M1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss CR, Roberts M, Florell M, Wood R, Johnson-Koenke R, Amura CR, et al. Best practices for telehealth in nurse-led care settings—a qualitative study. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2024;25(1):47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;304(7889):1127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speilberger CD, Gorsuch R, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(0 11):10–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Mouden SB, Mittal D, Hudson TJ, Schroeder GW, et al. Practice-based versus telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression in rural federally qualified health centers: a pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Focus. 2017;15(3):361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Luo C, Sanger N, Singhal N, Pattrick K, Shams I, Shahid H, et al. A comparison of electronically-delivered and face to face cognitive behavioural therapies in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Egede LE, Dismuke CE, Walker RJ, Acierno R, Frueh BC. Cost-Effectiveness of behavioral activation for depression in older adult veterans. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5):17m11888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milosevic I, Cameron DH, Milanovic M, McCabe RE, Rowa K. Face-to-face versus video teleconference group cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a preliminary comparison. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67(5):391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walton CJ, Gonzalez S, Cooney EB, Leigh L, Szwec S. Engagement over telehealth: comparing attendance between dialectical behaviour therapy delivered face-to-face and via telehealth for programs in Australia and new Zealand during the Covid-19 pandemic. Borderline Personality Disorder Emot Dysregulation. 2023;10(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giovanetti AK, Punt SE, Nelson EL, Ilardi SS. Teletherapy versus in-person psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Telemedicine e-Health. 2022;28(8):1077–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott AM, Bakhit M, Greenwood H, Cardona M, Clark J, Krzyzaniak N, et al. Real-time telehealth versus face-to-face management for patients with PTSD in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2022;83(4):41146. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Greenwood H, Krzyzaniak N, Peiris R, Clark J, Scott AM, Cardona M, et al. Telehealth versus face-to-face psychotherapy for less common mental health conditions: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mental Health. 2022;9(3):e31780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Krzyzaniak N, Greenwood H, Scott AM, Peiris R, Cardona M, Clark J, Glasziou P. The effectiveness of telehealth versus face-to face interventions for anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2024;30(2):250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lalor I, Costello C, O’Sullivan M, Rice C, Collins P. Brief psychological interventions in face-to-face and telehealth formats: a comparison of outcomes in a naturalistic setting. Mental Health Rev J. 2023;28(1):82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stiles-Shields C, Corden ME, Kwasny MJ, Schueller SM, Mohr DC. Predictors of outcome for telephone and face-to-face administered cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. Psychol Med. 2015;45(15):3205–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao Z, Han X. Evaluation of the effectiveness of telehealth chronic disease management system: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e44256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tahsin F, Bahr T, Shaw J, Shachak A, Gray CS. (2024). The relationship between treatment burden and the use of telehealth technologies among patients with chronic conditions: a scoping review. Health Policy Technol, 100855.

- 51.Sánchez-Gutiérrez C, Gil‐García E, Rivera‐Sequeiros A, López‐Millán JM. Effectiveness of telemedicine psychoeducational interventions for adults with non‐oncological chronic disease: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(5):1267–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snoswell CL, Chelberg G, De Guzman KR, Haydon HM, Thomas EE, Caffery LJ, Smith AC. The clinical effectiveness of telehealth: a systematic review of meta-analyses from 2010 to 2019.(vol 29, 669, 2023). Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2024;30(10):1667–1667. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Bellanti DM, Kelber MS, Workman DE, Beech EH, Belsher BE. Rapid review on the effectiveness of telehealth interventions for the treatment of behavioral health disorders. Mil Med. 2022;187(5–6):e577–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabner J, Norris LA, Olino TM, Kendall PC. A comparison of telehealth and in-person therapy for youth anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2024;1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Stubbings DR, Rees CS, Roberts LD, Kane RT. Comparing in-person to videoconference-based cognitive behavioral therapy for mood and anxiety disorders: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research. 2013 ;15(11):e258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Axelsson E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, Björkander D, Hedman-Lagerlöf M, Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Effect of internet vs face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for health anxiety: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(9):915–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van der Merwe M, Atkins T, Scott AM, Glasziou PP. Diagnostic assessment via live telehealth (Phone or Video) versus face-to-face for the diagnoses of psychiatric conditions: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2024;85(4):56942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berryhill MB, Halli-Tierney A, Culmer N, Williams N, Betancourt A, King M, Ruggles H. Videoconferencing psychological therapy and anxiety: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2019;36(1):53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irvine A, Drew P, Bower P, Brooks H, Gellatly J, Armitage CJ, et al. Are there interactional differences between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy? A systematic review of comparative studies. Journal of affective disorders. 2020;265:120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Horwitz AG, Mills ED, Sen S, Bohnert AS. Comparative effectiveness of three digital interventions for adults seeking psychiatric services: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2422115–2422115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonçalves RL, Junior WM, Batchelor J, Ribeiro ALP, Pagano AS, Reis ZSN, et al. Usability in telehealth systems for non-communicable diseases attention in primary care, from the COVID-19 pandemic onwards: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Shore JH, Yellowlees P, Caudill R, Johnston B, Turvey C, Mishkind M, et al. Best practices in videoconferencing-based telemental health April 2018. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2018;24(11):827–832. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Yang Y, Huang Y, Dong N, Zhang L, Zhang S. Effect of telehealth interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Telemed Telecare. 2024;30(7):1053–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oliva E. How integrated telemental health services produced clinically meaningful results for anxiety and depression. 2020.

- 65.Waugh M, Voyles D, Shore JH, Lippolis LC, Lyon COREY. Telehealth in an integrated care environment. In: Raney L, Lasky G, Scott J, editors. Integrating behavioral health and primary care. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017. p. 121-33

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.