Abstract

Background/Objectives

To assess the efficacy of conventional, skeletal and invisible orthodontic appliance for maxillary first molar distalization.

Methods

On February 14, 2023, an electronic search was conducted to review molar distalization using conventional, skeletal and invisible appliance, and two updated searches were conducted on August 31, 2023 and November 31,2024. After study selection, data extraction and risk of bias assessment, meta-analyses were performed for molar distalization, molar tipping, incisor movement, incisor tipping and mandibular plane angle change using random-effects model.

Results

55 studies fulfilled inclusion criteria, and 26 studies underwent meta-analysis. The clear aligner group demonstrated a significant reduction in upper molar distalization and tipping (2.33mm; 3.01°) compared to conventional appliance (3.29mm; 6.39°) and skeletal appliance (3.48mm; 5.84°) groups. Conventional appliance group experienced a significantly greater loss of anchorage (1.69mm; 3.99°) and a greater increase in mandibular plane angle (0.66°). Molar distalization after the eruption of the maxillary second molar may lead to greater loss of anchorage (1.76mm; 3.99°). 4-premolar-support group (4.09mm; 8.24°) appeared to produce more molar distalization and tipping than 2-premolar-support group (2.72mm; 4.90°). Buccal-miniscrew subgroup exhibited a smaller molar distalization(2.01mm) compared to palatal-miniscrew (3.81mm) and infrazygomatic-miniscrew subgroups(4.90mm).

Conclusions

The use of clear aligners resulted in a decrease in molar distal tipping but also led to a reduction in distalization, while the use of conventional appliances resulted in higher anchorage loss and a greater increase in mandibular plane angle. Distalization after the eruption of U7 may increase the risk of anchorage loss. 4-premolar-support anchorage improved the molar distalization, but also increased molar tipping in comparison to 2-premolar-support anchorage. Alternatively, palatal miniscrew support resulted in higher distal tipping but less incisor distal movement and tipping. However, additional RCTs or prospective studies are strongly recommended to provide further clinical evidence.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12903-025-06378-4.

Keywords: Molar distalization, Clear aligner, Skeletal anchorage, Conventional appliance

Introduction

The worldwide incidence rate of malocclusion was approximately 54%, with around one quarter of patients presenting with an Angle Class II malocclusion [1]. The selection of treatment was dependent on the patient's dental and osseous factors [2]. The following options may be considered: Firstly, correction with functional or mechanical appliances, depending on growth potential and patient compliance; Secondly, Orthodontic treatment involves the extraction of at least two healthy teeth, which poses difficulty for some patients to accept [3]; Thirdly, Class I occlusion can be achieved by distalizing the maxillary molars [4] with conventional, skeletal and invisible orthodontic appliances.

Conventional appliances used in clinical practice for molar distalization can be divided into two categories: extraoral appliances (such as headgear) and intraoral appliances (including repelling magnets, pendulum and pende-x, distal jet,jones jigs, lingual intra-arch Ni-Ti coil appliance and others). All these devices have demonstrated practical effectiveness, but also exhibit drawbacks. Molar distalization with conventional appliance is associated with several negative effects, including mesial tipping of the anterior teeth, increased overjet, mesial movement of the premolars [5–7]. Overall, these effects resulted in varying degrees of anchorage loss.

With the introduction of Professor Branemark’s theory of “osseointegration” [8] and the subsequent development and widespread use of implant techniques in 1965, various orthodontic support devices represented by miniscrews began to emerge in East Asia during the 1990 s [9, 10]. These devices gradually gained acceptance worldwide and were implemented in clinical practice. With their advantages of good biocompatibility, increased comfort, reduced damage and limitations, miniscrews can provide stable support during orthodontic tooth intrusion, retraction, extrusion and distalization. The application of miniscrews has opened new options for molar distal treatment, but has also presented new challenges such as root resorption, penetration of the maxillary sinus, miniscrew movement, pain and inflammation [11].

The clear aligner was introduced in 1997 and became commercially available in 1999, followed by subsequent rapid advancements [12]. It offers advantages including aesthetics, comfort and hygiene, and flexibility of removal and wear [13]. In recent years, clear aligner technology has evolved due to advancements in invisible orthodontic materials, improvements in attachments, and enhanced clinical skills, resulting in notable success in molar distalization. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of clear aligners for molar distalization [12]. However, despite optimal design and patient cooperation, challenges remain in adhering to the original treatment plan. Actual tooth movement in the clinical setting may not exactly match the program design [14]. While clear aligners have shown promise, a recent prospective study found that their accuracy in predicting tooth movement was only 50% [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate invisible orthodontic techniques for molar distalization.

Both traditional and invisible orthodontic techniques have their own pros and cons. However, due to the absence of research and clinical guidelines, doctors who provide treatment for molar distalization have to rely on their own clinical experience, expert opinion and limited evidence.

Several previous systematic reviews have examined comparisons of anchorage types for molar distalization [16, 17], distalization time [18] and the position of miniscrews [19]. Grec et al. [16] and Soheilifar et al. [17] demonstrated that skeletal anchorage enhances distalization efficiency while minimizing anterior anchorage loss. Bellini-Pereira et al. [18] found that non-compliance intraoral distalizers achieve distalization within 6–12 months, with skeletal anchorage providing more predictable outcomes. Bayome et al. [19] highlighted the critical role of miniscrew placement, with anterior palate positioning yielding optimal results. However, there are no relevant studies comparing conventional, skeletal and invisible orthodontic techniques for molar distalizaiton nor any studies focusing on changes in upper incisor position and mandibular planes after molar distalization. These two factors are closely related to the patient's facial shape, and orthodontists should pay attention to them during treatment. The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the available evidence and compare the efficacy of molar distalization in conventional, skeletal and invisible orthodontic appliances. This study aims to provide clinicians with a higher level of reference evidence to assist in the selection of appropriate appliances for the treatment of Angle Class II malocclusions.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol of this systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO with the number CRD42023423353 and is reported according to the PRISMA guideline [20, 21].

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

The following eligibility criteria were applied for the review:

Participants: Angle Class II malocclusion patients treated with conventional or invisible orthodontic techniques without extractions.

Intervention and comparators: Maxillary molar distalization with conventional, skeletal or invisible appliance.

Outcome: Studies with description of molar distalization, molar distal tipping, incisor mesial movement, incisor mesial tipping or change in mandibular plane angle.

Study design: Prospective or retrospective studies in human subjects, controlled clinical studies (randomized or nonrandomized studies) with or without untreated control.

Exclusion criteria

The following eligibility criteria were applied for the review:

Studies with fewer than 10 samples.

Case reports, review and abstract articles, and patient description articles.

Studies with insufficient description of the use of aligners for distal movement of molar.

Cases with effects on the temporomandibular joint or supplemented with surgery.

Studies of the use of extra-oral orthoses.

Studies without description of eruption of second molars.

Studies focusing on mandibular molar distalization

Information sources, search strategy and selection process

An electronic search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, Scopus and Embase until February 14, 2023, with limitations to the English language. Furthermore, the evaluators updated the search on August 31, 2023.

The search strategy was as follows:

-

A.

molar distalization or distalizer or distal molar movement or distal molar or distalization appliance or molar backwards

-

B.

traditional orthodontic appliance or intraoral appliance or fixed orthodontic appliance or removable orthodontic appliance or conventional anchorage or orthodontic bracket

-

C.

mini-implant or micro implant or microimplant or miniscrew or mini screw or skeletal anchorage or temporary anchorage devices or TADs

-

D.

clear appliance or clear aligner or Invisalign or invisible bracketless technique or invisible orthodontics

-

E.

A and (B or C or D)

An example search strategy in PubMed was as follows:

((molar distalization) OR(distalizer) OR(distal molar movement) OR(distal molar) OR(distalization appliance) OR(molar backwards)) AND(((traditional orthodontic appliance) OR(intraoral appliance) OR(fixed orthodontic appliance) OR(removable orthodontic appliance) OR(conventional anchorage) OR(orthodontic bracket)) OR((mini implant) OR(micro implant) OR (microimplant) OR(miniscrew) OR(mini screw) OR(skeletal anchorage) OR(temporary anchorage devices) OR(TADs)) OR((clear appliance) OR(clear aligner) OR(Invisalign) OR(invisible bracketless technique) OR(invisible orthodontics))).

The search strategy was modified for the databases as per the requirements.

Two evaluators (YC H and YF W) independently conducted a two-phase study selection process. Initially, after automatic machine and manual screening of duplicate articles, all retrieved articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts, and potentially irrelevant articles were excluded. Then the same evaluators thoroughly analyzed the remaining full-text articles and identified those that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In case some important information was missing or incomplete, the authors were contacted to provide additional the data.

The selection of the study, risk of bias assessment and extraction of data were performed in duplicate and independently by both evaluators. If a disagreement emerged between the two initial evaluators, another evaluator (YT L) engaged in discussion and negotiation to resolve the issue and reach a consensus conclusion. All evaluators had a minimum of three years of clinical experience in orthodontic practice, ensuring a high level of expertise in the subject matter.

Data collection and items

Two evaluators extracted following data: Type of study design, sample size, participants characteristics regarding age and gender, type of aligner used, type of anchorage, position of anchorage, method used to measure, amount of molar distalization, distalization time, molar distal tipping, incisor mesial movement, incisor mesial tipping and change in mandibular plane angle.

Study risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias (ROB) in the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in the study was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s ROB2 tool [22]. The domains assessed were: 1) randomization process, 2) deviations from intended interventions, 3) missing outcome data, 4) outcome measurement, and 5) selection of the reported result. For each included trials, the ROB2 for each domain was judged as ‘low risk’, ‘some concerns’, or ‘high risk’. Each RCT received an overall bias in terms of ‘low risk’, ‘some concerns’, or ‘high risk’. Those studies deemed as having ‘high risk’ of bias were excluded from the meta-analysis.

The risk of bias in the non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs) included in this study was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s ROBINS-I tool [23]. The tool assessed seven domains: 1. Bias due to confounding, 2. Bias in selection of participants into the study, 3. Bias in classification of interventions, 4. Bias due to deviations from intended interventions, 5. Bias due to missing data, 6. Bias in measurement of outcomes, 7. Bias in selection of the reported result. For each trial included, we assessed the ROBINS-I for each domain as ‘Low’, ‘Moderate’, ‘Serious’, ‘Critical’, or ‘No information’. Additionally, studies judged with serious ROBINS-I were excluded from the Meta-analysis.

Outcome measures

Distalization of upper first molar (U6).

Distal tipping of upper first molar (U6).

Anchorage loss of anterior teeth shown by mesial movement and mesial tipping of upper incisor (1st).

Change of mandibular plane angle.

All measurements were performed on dental casts, lateral cephalograms or CBCT scans. Means and standard deviations were obtained for all data. The 95% confidence interval and standard errors were calculated during meta-analysis.

Synthesis methods

Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager software (RevMan version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) by generic inverse variance approach. The random-effects method was used due to the high degree of heterogeneity and diversity in the forces applied and malocclusion severity across the studies analyzed. The random effects model was selected based on both clinical and statistical justifications [24].

Heterogeneity was assessed by inspecting the forest plot and computing Tau2, Chi2, and I2 statistics. Level of significance was set at 0.05.

Reporting bias assessment

When more than ten studies were identified, standard funnel plots or Egger’s test were planned to identify any publication bias.

Additional analyses

In order to evaluate the impact of specific study characteristics on the efficacy of molar distalization, subgroup analysis was performed regarding the eruption status of the second molar, amount of anchorage teeth, and position of mini-screws. If the minimum sample threshold of 5 studies was not reached, no subgroup analysis was performed. Sensitivity analysis was also carried out.

Results

Study selection

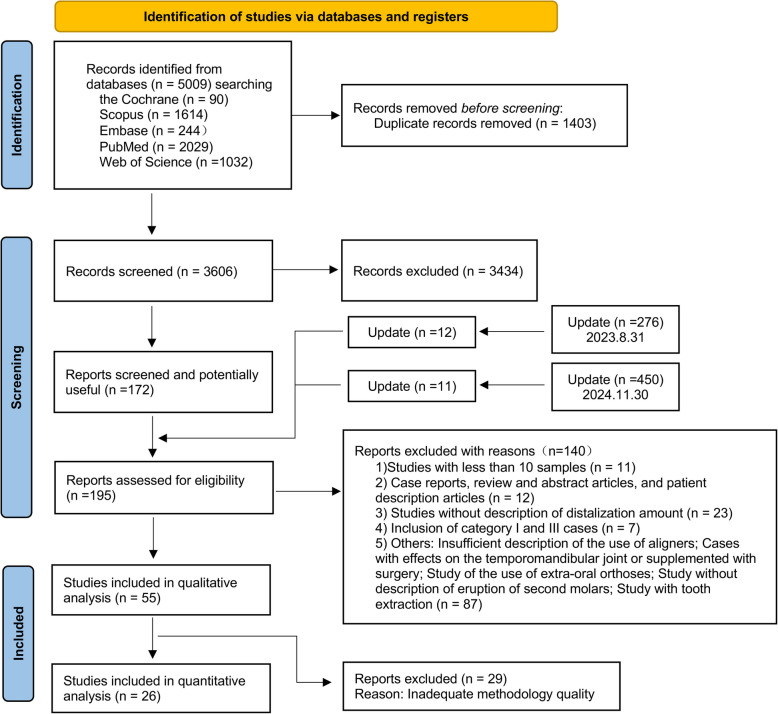

5009 studies were screened after completing the database searches. After eliminating duplicate articles and those articles that were considered clearly irrelevant after reading the titles and abstracts, 172 studies were initially included. Twelve studies were added in the first update search on 31 August 2023 and 11 documents were added in the second update search on 31 November 2024. By applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the 195 eligible studies, 55 studies were included in the qualitative analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the data extracted from the included studies: 4 RCTs, 15 prospective studies and 36 retrospective studies. A total of 1718 cases of molar distalization were included. 28 studies [4, 25–51] included 883 cases treated with conventional orthodontic appliances, using Nance buttons and 2 or 4 premolars as anchorage. 6 studies [52–57] treated with clear aligner appliances included 180 cases. And 25 studies [41, 46, 47, 50, 58–78] using skeletal orthodontic appliance included 655 cases, which strengthened the anchorage by utilizing 1 to 6 miniscrews. In all reviewed articles, anchorage had been placed in the palatal, buccal or infrazygomatic sides.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (7th, maxillary second molar; U6, maxillary first molar; U1, maxillary incisor; N/A, not applicable; M, male; F, female; RCT, randomized controlled trial; y, year; E, erupted; U, unerupted; m, month)

| Study | Type of study | Measuring Material | Appliance | Type of anchorage | Position of anchorage | Sample size | Age | 7th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Ghosh 1996 | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 26F 15M | F-12y5m±1y10m,M-12y5m±1y2m | 18E23U |

| 2.Byloff 1997(1) | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 9F 4M | 11y1m±1y9m | 4E9U |

| 3.Byloff 1997(2) | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 8F 12M | 13.11±1.1y | 8E12U |

| 4.Brickman 2000 | retrospective | Ceph | Jones Jig | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 46F 26M | F-14y1m±4y3m,M-13y4m±4y3m | 44E28U |

| 5.Bussick 2000 | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 56F 45M | F-12y1m(8y4m-16y5m)M-12y1m(8y3m-15y9m) | 44U,57E |

| 6.Bondemark LINC 2000 | retrospective | Ceph | Lingual intra-arch Ni-Ti coil | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 21F | 14.4±1.4y | E |

| Bondemark M 2000 | Magnet | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 21F | 13.9±1.94y | E | ||

| 7.Keles 2000 | retrospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Keles | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 5M | F-13.8y(11-15.8y),M-13.1y(10.8-15.1y) | E |

| 8.Torog˘lu 2001 | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 8F 8M | 155.5±18.6m | 12E4U |

| 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 4M | 157.7±8m | 8E6U | ||||

| 9.Bolla 2002 | retrospective | Ceph | Distal Jet | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 11F 9M | 12.6±2.3y | 9U11E |

| 10.Taner 2003 | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 3M | 10.64±1.42y | U |

| 11.Fortini 2004 | retrospective | Ceph | First Class | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 7F 10M | 13y4m(11y4m-17y2m) | 12E5U |

| 12.Kinzinger 2004 | retrospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 25F 11M | 12.05y | 18U18E |

| 13.Gelgor 2004 | prospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Intraosseous screw+Bilateral sectional arches | 1 miniscrew+2 premolars | palatal | 18F 7M | 13y9m | 22E3U |

| 14.Bondemark 2005 | RCT | Ceph | Lingual intra-arch Ni-Ti coil | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 10M | 11.4±1.37y | U |

| 15.Chiu DJ 2005 | retrospective | Ceph | Distal Jet | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 19F 13M | 12y3m±1.4m | 9U23E |

| Chiu P 2005 | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 19F 13M | 12y6m±1y1m | 9U23E | ||

| 16.Akin 2006 | prospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Segmented removable appliance | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 12F 16M | 11.8y | 15E13U |

| 17.Karlsson 2006 | retrospective | Ceph | Intra-arch NiTi coil | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 10M | 14.6±1.1y | E |

| 18.Gelgor 2007 | retrospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Intraosseous screw+Bilateral sectional arches | 1 miniscrew+2 premolars | palatal | 8F 12M | 11.6-15.1y | 18E2U |

| Intraosseous screw+Keles | 1 miniscrew+2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 11F 9M | 12.3-15.4y | 17E3U | |||

| 19.Polat-Ozsoy BAP 2008 | retrospective | Ceph | Bone-anchored pendulum | 2or1 miniscrews | palatal | 15F 7M | 13.61±2.01y | 3U19E |

| Polat-Ozsoy CP 2008 | Conventional pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 7M | 13.62±2.07y | 2U15E | ||

| 20.Oberti 2009 | prospective | Ceph | Dual-force distalizer | 2 miniscrews | palatal | 16 | 14.3y | U |

| 21.Kinzinger 2009 | retrospective | Ceph | Skeletonized distal jet | 2 miniscrews+2 premolars | palatal | 8F 2M | 12y1m | 4E6U |

| 22.Patel JJ 2009 | prospective | Ceph | Jones Jig | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 9F 11M | 13.17±1.52y | 17E3U |

| Patel P 2009 | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 12F 8M | 13.98±1.72y | E | ||

| 23.Papadopoulos 2010 | RCT | Ceph+Dental casts | First Class | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 7F 8M | 9.2y(7.6-10.8y) | U |

| 24.Nur 2012 | prospective | Ceph | Zygoma-Gear | 6 miniscrews+2 miniplates | infrazygomatic | 8F 7M | 15.87±1.09y | E |

| 25.Kaya BAP 2013 | retrospective | Ceph | Bone-anchored pendulum | 2 miniplates | palatal | 10F 5M | 14.3±1.6y | E |

| Kaya ZAS 2013 | Zygoma anchorage system | 6 miniscrews+2 miniplates | infrazygomatic | 10F 5M | 14.7±2.5y | E | ||

| 26.Bechtold 2M 2013 | prospective | Ceph | Slot edgewise appliances + Miniscrews | 2 miniscrews between 5th、6th | buccal intraradicular | 11F 1M | 23.58±6.92y | E |

| Bechtold 4M 2013 | Slot edgewise appliances + miniscrews | 4 miniscrews between 4th、5th、6th | buccal intraradicular | 11F 2M | 22.92±7.1y | E | ||

| 27.Burhan 2013 | RCT | Ceph | Frog | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 13F 12M | 14.5±1.7y | E |

| 28.Maino 2013 | retrospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Miniscrew implant supported distalization system | 4 miniscrews+2 premolars | palatal+buccal intraradicular | 15F 15M | 13.3±3.3y | 20E10U |

| 29.Sar MISD 2013 | prospective | Ceph | Miniscrew implant supproted distalization system | 2 miniscrews | palatal | 8F 6M | 14.8±3.6y | E |

| Sar BAP 2013 | Bone-anchored pendulum | 2 miniscrews+Nance button | palatal | 9F 5M | 14.5±1.3y | E | ||

| 30.Caprioglio SP 2014 | retrospective | Ceph | Segmented Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 11F 13M | 12.9±1.4y | E |

| Caprioglio QP 2014 | Quad Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 5F 6M | 13.2±1.2y | E | ||

| 31.Kook 2014 | retrospective | Ceph | Modified palatal anchorage plate | 3 miniscrews | palatal | 13F 7M | 22.9y(17.4-33y) | E |

| 32.Nienkemper 2014 | retrospective | Ceph | Beneslider | 2 miniscrews | palatal | 9F 5M | 11.5±1.5y | U |

| 11F 12M | 13.7±1.8y | E | ||||||

| 33.Fontana 2015 | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum,Distal jet,Fast back, Compressed NiTi coil spring,Loca-system wires | 2-4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 25F 8M | F-23y1m±3m,M-28y3m±7m | E |

| 34.Sa’aed 2015 | retrospective | Ceph | Modified palatal anchorage plate | 3 miniscrews | palatal | 6F 18M | 12.42±1.69y | 16E8U |

| 35.Duran 2016 | prospective | Dental casts | Miniscrew-supported molar distalization appliance | 2 miniscrews | palatal | 9F 12M | 12.3-15.3y | E |

| 36.Ravera 2016 | prospective | Ceph | Clear aligner | anterior teeth+Mandibular arch | buccal intraradicular+palatal /N/A | 11F 9M | 29.73±6.89y | E |

| 37.Park 2017 | retrospective | Ceph | Modified C-palatal plate | 3 miniscrews | palatal | 16F 6M | 24.7±7.7y | E |

| 38.Kırcalı 2018 | prospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Mini-screw-anchored pendulum | 1 miniscrew+2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 7F 13M | 14.05±2.4y | E |

| 398.Lee MCPP 2018 | retrospective | Ceph | Modified C-palatal plate | 3 miniscrews | palatal | 22 | 21.9±6.6y | E |

| Lee BM 2018 | Buccal miniscrews supproted distalization system | 2 miniscrews between 5th、6th | buccal intraradicular | 18 | 24.2±6.8y | E | ||

| 40.Reis 2019 | prospective | Ceph | Distal Jet | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 17F 5M | 12.7±1.2y | E |

| 41.Abdelhady 2020 | prospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Buccal miniscrews supproted distalization system | 2 miniscrews between 5th、6th | buccal intraradicular | 11F | 12y4m(11-14y) | E |

| 42.Bechtold 2020 | retrospective | Ceph | Buccal miniscrews supproted distalization system | 2 miniscrews between 5th、6th | buccal intraradicular | 15F 4M | 24.9±5y | E |

| 43.Bozkaya HP 2020 | retrospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Hybrid pendulum | 1 miniscrew+2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 14F 8M | 14.3±2.43y | E |

| Bozkaya CP 2020 | Conventional Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 15F 6M | 14.6±3.39y | E | ||

| 44.Alfaifi MCP 2020 | retrospective | Ceph | Modified C-palatal plates | 3 miniscrews | palatal | 12F 9M | 11.7±1.3y | 11E31U |

| Alfaifi GMD 2020 | Ceph | Greenfield molar distalizer | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 12F 6M | 11.2±0.9y | 5E31U | |

| 45.Vilanova JJ 2020 | retrospective | Ceph | Jones Jig | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 14F 16M | 13.17±1.24y | 24E6U |

| Vilanova DJ 2020 | Distal Jet | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 17F 8M | 12.57±1.43y | 17E8U | ||

| Vilanova FC 2020 | First Class | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 10F 6M | 12.84±1.31y | 12E4U | ||

| 46.Serafin 2021 | retrospective | Ceph | Pendulum | 4 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 14F 10M | 12.1y(10.5-14.2y) | E |

| 47.Cui 2022 | retrospective | Ceph | Clear aligner | anterior teeth+Mandibular arch | N/A | 18 | 27.8±5.38y | E |

| 48.Longerich 2022 | prospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Beneslider | 2 miniscrews | palatal | 21F 16M | 12.3±1.67y | U |

| 11F 10M | 16±4.17y | E | ||||||

| 49.Rongo 2022 | retrospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Clear aligner | anterior teeth+Mandibular arch | N/A | 15F 5M | 27.9±7.5y | E |

| 50.Rosa 2022 | prospective | Ceph+Dental casts | Infrazygomatic crest anchorage system | 2 miniscrews | infrazygomatic | 14F 11M | 13.6±1.5y | E |

| 51.Anraki FC 2023 | prospective | Ceph | First Class | 2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 7F 3M | 13.31±1.35y | 3U7E |

| Anraki S1 2023 | Skeletally anchored type 1 First Class | 2 miniscrews+2 premolars | palatal | 4F 6M | 13.77±1.9y | 2U8E | ||

| Anraki S2 2023 | Skeletally anchored type 2 First Class | 2 miniscrews+2 premolars+Nance button | palatal | 7F 3M | 13.39±1.35y | 3U7E | ||

| 52.Raghis PP 2023 | RCT | Ceph | Palatal plate | 2 miniscrews+Nance button | palatal | 15F 5M | 18.8±2.8y | E |

| Raghis BM 2023 | Buccal miniscrews supproted distalization system | 2 miniscrews between 6th、7th | buccal intraradicular | 18F 2M | 21.1±3y | E | ||

| 53.Loberto 2023 | retrospective | 3D digital casts | Clear aligner | anterior teeth+Mandibular arch | N/A | 27F 22M | 14.9±6y | E |

| 54.Li 2023 | retrospective | laser-scanned casts | Clear aligner | anterior teeth+Mandibular arch/miniscrew | N/A/buccal intraradicular | 38F 5M | 28.15±6.94y | E |

| 55.Liu 2024 | retrospective | CBCT+Dental casts | Clear aligner | 2 miniscrews | buccal intraradicular | 15F 2M | 26.7±5.2y | E |

| anterior teeth+Mandibular arch/miniscrew | NA | 11F 2M | 30.4±9.4y | E |

| Study | Treatment time | U6 distalization | U6 distal tipping | U1 mesial movement | U1 mesial tipping | Mandibular plane angle change(SN-MP) | 列1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Ghosh 1996 | 6.21±1.44m | 3.37±2.1mm | 1.29±7.52° | N/A | 2.4±4.57° | N/A | |

| 2.Byloff 1997(1) | 16.6±7w | 3.39±1.25mm | 14.5±8.33° | 0.92±0.67mm | 1.71±1.48° | N/A | |

| 3.Byloff 1997(2) | 27.25±7.12w | 4.14±1.61mm | 7.27±1.76° | 1.54±0.88mm | 3.2±3.02° | N/A | |

| 4.Brickman 2000 | 6.35±2.75m | 2.51±1.99mm | 7.53±4.57° | N/A | 2.4±3.46° | N/A | |

| 5.Bussick 2000 | 7±2m | 5.7±1.9mm | 10.6±5.6° | 1.4±1.5mm | 3.6±8.4° | N/A | |

| 6.Bondemark LINC 2000 | 6.5±1.36m | 2.5±0.69mm | 2.2±2.53° | 1.5±0.92mm | 4.7±3.65° | 0.6±0.77° | |

| Bondemark M 2000 | 5.8±0.97m | 2.6±0.51mm | 8.8±2.82° | 1.9±0.64mm | 5.5±2.52° | 0.5±0.65° | |

| 7.Keles 2000 | 7.5m | 5.23±1.89mm | 1.15±6.46° | 4.7±2.15mm | 6.73±5.98° | 1.26±0.96° | |

| 8.Torog˘lu 2001 | 5.03±1m | 4.1±0.8mm | 13.4±4.6° | 4.1±1.6mm | 8.7±6.4° | N/A | |

| 5.7±0.5m | 5.9±2.3mm | 14.9±5.3° | 2.1±1.1mm | 3.6±3.5° | N/A | ||

| 9.Bolla 2002 | 5m(2-6m) | 3.2±1.4mm | 3.1±2.8° | N/A | 0.6±5.3° | N/A | |

| 10.Taner 2003 | 7.31±4.09m | 3.81±2.25mm | 11.77±11.14° | 2±1.54mm | 6.08±3.67° | N/A | |

| 11.Fortini 2004 | 72d(41-110d) | 4±1.5mm | 4.6±2.6° | 1.3±1.3mm | 2.6±1° | 0.5±0.9° | |

| 12.Kinzinger 2004 | 21.86w | 3.14±0.92mm | 3.07±4.02° | 1.33±0.85mm | 4.51±3.6° | N/A | |

| 13.Gelgor 2004 | 4.6m | 3.9±1.61mm | 8.7±4.8° | 0.48±0.62mm | 1±1.34° | 0.1±0.02° | |

| 14.Bondemark 2005 | 5.2±1m | 3±0.64mm | 2.9±1.92° | 0.8±0.88mm | 2±2.66° | 0.5±0.74° | |

| 15.Chiu DJ 2005 | 10±2m | 2.8±1.1mm | 5±3.6° | 3.7±1.7mm | 13.7±8° | N/A | |

| Chiu P 2005 | 7±2m | 6.1±1.8mm | 10.7±5.5° | 1.1±1.2mm | 3.1±4.1° | N/A | |

| 16.Akin 2006 | 4.57±1.29m | 3.98±0.95mm | 4.61±1.42° | 1.09±0.39mm | 1.27±0.55° | 0.59±0.81° | |

| 17.Karlsson 2006 | 6.5±0.83m | 2.2±0.84mm | 3±4.27° | 1.8±0.97mm | 3.9±3.17° | 0.5±1.08° | |

| 18.Gelgor 2007 | 4.6m | 3.95±1.68mm | 9,05±4.67° | 0.52±0.61mm | 1.08±1.46° | 0.13±0.51° | |

| 5.4m | 3.88±1.47mm | 0.75±0.72° | 0.1±0.16mm | 0.07±0.21° | -0.07±0.24° | ||

| 19.Polat-Ozsoy BAP 2008 | 6.8±1.7m | 4.8±1.8mm | 9.1±4.6° | -0.1±1.7mm | -1.7±2.9° | 0.8±1.4° | |

| Polat-Ozsoy CP 2008 | 5.1±0.9m | 2.7±1.7mm | 5.3±3.8° | 1.2±1.7mm | 0.9±2.4° | 0.6±1.1° | |

| 20.Oberti 2009 | 5m | 5.9±1.7mm | 5.6±3.7° | -0.53±0.76mm | -0.84±1.41° | N/A | |

| 21.Kinzinger 2009 | 6.7m | 3.92±0.53mm | 3±2.31° | 0.36±0.32mm | 0.64±0.75° | N/A | |

| 22.Patel JJ 2009 | 0.91±0.35y | 3.12±1.56mm | 9.54±4.21° | 1.11±1.86mm | 2.29±5.03° | 0.38±1.96° | |

| Patel P 2009 | 1.18±0.28y | 3.51±1.73mm | 10±4.04° | 1.47±1.63mm | 3.11±3.63° | 0.63±0.98° | |

| 23.Papadopoulos 2010 | 4.01m | 4±1.90mm | 8.56±5.73° | 0.68±1.20mm | 2±3.91° | 1.05±2.52° | |

| 24.Nur 2012 | 5.21±0.96m | 4.36±2.15mm | 3.3±2.31° | 0.6±0.98mm | -1.33±0.97° | -0.23±1.16° | |

| 25.Kaya BAP 2013 | 8.1±4.2m | 3±1.7mm | 8.8±6.54° | 1.1±2.44mm | 2±5.29° | 0.5±0.93° | |

| Kaya ZAS 2013 | 9±2.4m | 5.27±1.53mm | 5.77±4.99° | -3.33±3.52mm | -5.4±6.51° | 1±1.4° | |

| 26.Bechtold 2M 2013 | 9.08±4.89m | 1.29±0.66mm | 3.19±4.61° | -1.83±1.23mm | -1.72±2.22° | -0.09±0.29° | |

| Bechtold 4M 2013 | 11.27±5.71m | 2.91±0.96mm | 1.55±1.32° | -2.41±1.8mm | -2.41±7.4° | -0.74±0.96° | |

| 27.Burhan 2013 | 7.44±1.3m | 5.51±2.56mm | 4.96±1.41° | 1.78±0.93mm | 1.4±0.63° | 1.58±1.38° | |

| 28.Maino 2013 | 8±2.05m | 4.14±2.8mm | 10.5±6.2° | N/A | 1.4±2.5° | N/A | |

| 29.Sar MISD 2013 | 10.2±2.4m | 2.81±2.7mm | 1.65±7.29° | 0.31±1.75mm | -1.38±3.08° | -0.08±2.72° | |

| Sar BAP 2013 | 8.2±4.3m | 2.93±1.74mm | 9±6.74° | 1.07±2.53mm | 1.96±5.49° | 0.43±0.92° | |

| 30.Caprioglio SP 2014 | 10±2m | 4±0.9mm | 9.6±1.6° | 1.7±0.7mm | 3.8±0.9° | 0.7±0.9° | |

| Caprioglio QP 2014 | 11±1m | 3.5±0.7mm | 4.6±1.1° | 2.1±0.9mm | 6.6±1.2° | 1.2±0.6° | |

| 31.Kook 2014 | 12.5m | 3.3±1.8mm | 3.42±5.79° | -2.99±2.73mm | -6.21±7.64° | N/A | |

| 32.Nienkemper 2014 | 7±2.5m | 4.3±1.6mm | 2.4±6.5° | N/A | -1.2±4.3° | N/A | |

| 7.7±3.3m | 4.1±2mm | 2.6±7.4° | N/A | -1.5±8° | N/A | ||

| 33.Fontana 2015 | 3y2m±6m | 2.9±0.6mm | 0.2±1.8° | 2.1±1.6mm | -5.8±3.9° | 1.7±0.5° | |

| 34.Sa’aed 2015 | 28±8.2m | 3.06±2.64mm | -1.53±4.8° | -3.32±3.87mm | -7.66±8.82° | N/A | |

| 35.Duran 2016 | 5.3±1.46m | 4.1±1.57mm | 11.02±5.32° | -0.59±0.37mm | -1.59±0.91° | N/A | |

| 36.Ravera 2016 | 24.3±4.2m | 2.03±1.86mm | 1.64±8.24° | -2.23±4.16mm | -2.87±5.94° | -0.45±2.04° | |

| 37.Park 2017 | 29.9±11.9m | 4.22±2mm | 3.85±3.11° | -3.18±3.19mm | -8.02±8.12° | N/A | |

| 38.Kırcalı 2018 | 0.7±0.3y | 4.2±0.8mm | 8.9±3.1° | 0.6±0.7mm | 0.3±1.6° | -0.3±0.6° | |

| 398.Lee MCPP 2018 | N/A | 4.22±1.25mm | 1.98±4.2° | -2.89±2.93mm | -4.42±5.39° | N/A | |

| Lee BM 2018 | N/A | 2±1.26mm | 7.21±5.22° | -2.48±2.72mm | -3.9±7.72° | N/A | |

| 40.Reis 2019 | 1.2±0.3y | 1.2±1.4mm | 2.4±5.2° | 2.4±1.7mm | 4.3±4.7° | 0±1.4° | |

| 41.Abdelhady 2020 | 4.9±1.5m | 4.09±0.92mm | 2.48±6.16° | -0.82±0.81mm | -5.36±1.45° | 0.45±0.85° | |

| 42.Bechtold 2020 | 30.6±12.2m | 4.2±2mm | -0.6±3.8° | -3.4±3.5mm | -3.9±5.1° | -0.5±4.3° | |

| 43.Bozkaya HP 2020 | 0.7±0.25y | 4.25±0.95mm | 9.09±3.33° | 0.5±0.67mm | 0.03±1.79° | -0.39±0.63° | |

| Bozkaya CP 2020 | 0.83±0.4y | 3.21±1.79mm | 9.86±6.97° | 2.38±1.59mm | 4.76±4.62° | 0.64±1.31° | |

| 44.Alfaifi MCP 2020 | 38.6±17.6m | 3.96±1.46mm | 1.86±1.94° | -3.77±1.46mm | -7.13±2.9° | N/A | |

| Alfaifi GMD 2020 | 35.9±15.3m | 2.85±0.87mm | 4.65±2.46° | -1.84±0.81mm | -4.69±5.62° | N/A | |

| 45.Vilanova JJ 2020 | 0.81±0.33y | 1.82±1.33mm | 7.73±4.28° | 2.09±1.88mm | 6.08±3.86° | 0.28±1.86° | |

| Vilanova DJ 2020 | 1.06±0.42y | 1.52±1.51mm | 2.14±5.09° | 2.56±2.24mm | 5.32±4.24° | 0.34±1.45° | |

| Vilanova FC 2020 | 0.69±0.22y | 2.48±0.93mm | 6.05±3.76° | 0.74±1.39mm | 5.1±2.63° | -0.51±1.34° | |

| 46.Serafin 2021 | 8±2m | 2.8±3.2mm | 8.2±8.1° | 1.5±2.8mm | 5±3.6° | 0.8±3° | |

| 47.Cui 2022 | N/A | 2.57±1.15mm | 3.43±2.71° | -1.4±0.25mm | -7.04±1.27° | 0.22±0.73° | |

| 48.Longerich 2022 | 18.5±9.28m | 3.67±1.3mm | -0.64±5.12° | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 20±10.3m | 3.36±0.93mm | 1.78±4.84° | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| 49.Rongo 2022 | 1.6±0.6y | 0.93±0.97mm | N/A | N/A | -1.1±8.1° | -0.47±1.9° | |

| 50.Rosa 2022 | 7.76±2.5m | 5.32±1.66mm | 11.29±5.31° | -4.7±2.63mm | -13.42±10.13° | 0.08±2.34° | |

| 51.Anraki FC 2023 | 6.92±1.69m | 3.1±0.64mm | 7.81±1.27° | 2.02±0.74mm | 4.7±2.12° | 0.28±1.9° | |

| Anraki S1 2023 | 6.28±1.44m | 3.42±0.6mm | 6.78±0.86° | 1.38±0.53mm | 2.82±1.05° | -0.24±2.66° | |

| Anraki S2 2023 | 7.86±2.22m | 3.27±0.62mm | 7.09±1.45° | 1.34±0.52mm | 2.63±1.29° | 0.04±1.23° | |

| 52.Raghis PP 2023 | 11.2±3.7m | 4.33±1.52mm | 3.1±4.58° | -4.95±3.35mm | -11.25±8.91° | -0.93±2.43° | |

| Raghis BM 2023 | 13.03±3.11m | 1.88±1.6mm | 2±4.74° | -3.9±3.14mm | -7.38±6.96° | 0.6±2.78° | |

| 53.Loberto 2023 | 5.5m | 2.4±3.2mm | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 54.Li 2023 | N/A | 0.88±0.83mm | 2.01±3.36° | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 55.Liu 2024 | 20.9m | 1.21±1.15mm | 1.85±5.12° | -1.2±2.21mm | -4.52±8.01° | N/A | |

| 22.2m | 1.4±0.86mm | 4.1±2.53° | -1.99±1.59mm | -7.44±6.91° | N/A |

The ICC scores for all three evaluated stages evaluated (study selection, data extraction, and ROB assessment) were 80.5%, 79.1% and 83.0%, indicating almost perfect agreement between the two reviewers.

Risk of bias in studies

The ROBINS-I and ROB2 tools were used. For retrospective and prospective studies, only one study [58] was classified as “Low” risk, 22 studies [25, 26, 34, 38–43, 46–48, 50, 52, 53, 63–65, 67, 70, 72, 73] as “Moderate” risk and 27 studies [27–30, 33, 35–37, 44, 45, 49, 51, 54–57, 59–62, 66, 68, 69, 71, 74–77] as “Serious” risk. And the risk of bias in RCTs was “low risk” in one study [31], “some concerns” in two studies [4, 78] and “high risk” in one study [32]. The summary of ROB for NRCT and RCT is presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment in NRCTs

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment in RCTs

Therefore, after excluding all studies with high risk of bias, 23 NRCTs [25, 26, 34, 38–43, 46–48, 50, 52, 53, 58, 63–65, 67, 70, 72, 73] and 3 RCTs [4, 31, 78] were considered appropriate for the quantitative analysis.

Results in individual studies

U6 distalization with conventional orthodontic appliance in 514 patients ranged from 1.52mm [48] to 6.1mm [38], with U6 distal tipping ranging from 2.2° [26] to 10.7° [38]. Incisor mesial movement varied from 0.74mm [48] to 3.7mm [38]. All studies reported a incisor mesial tipping from 0.6° [34] to 13.7° [38] and an increase in the mandibular plane angle ranging from 0.23° [48] to 1.58° [31].

In skeletal orthodontic appliance involving 283 patients,U6 distalization ranged from 1.29mm [65] to 5.27mm [64], with U6 distal tipping ranging from 1.55° [65] to 11.02° [58]. More than half of the studies reported incisor distal movement(−0.1mm [41] to −4.95mm [78]), while others reported incisor mesial movement(0.31mm [67] to 1.38mm [50]). Most studies reported incisor distal tipping from −1.33° [63] to −11.25° [78], while some reported mesial tipping(0.03° [46] to 2.82° [50]). Half of the studies reported a slight increase in the mandibular plane angle(0.04° [50] to 1° [64]) and the other half reported a slight decrease(−0.08° [67] to −0.93° [78]).

For clear aligner, only two studies with a total of 38 patients were included in the quantitative analysis. U6 distalization was 2.03mm [52] and 2.57mm [53]. U6 distal tipping was 1.64° [52]and 3.43° [53]. Incisor distal movement was −1.4mm [53] and −2.23mm [52], and distal tipping was −2.87° [52] to −7.04° [53]. For the mandibular plane angle, one study [53] reported a slight increase of 0.22°and another [52] reported a decrease of −0.45°.

Results of syntheses

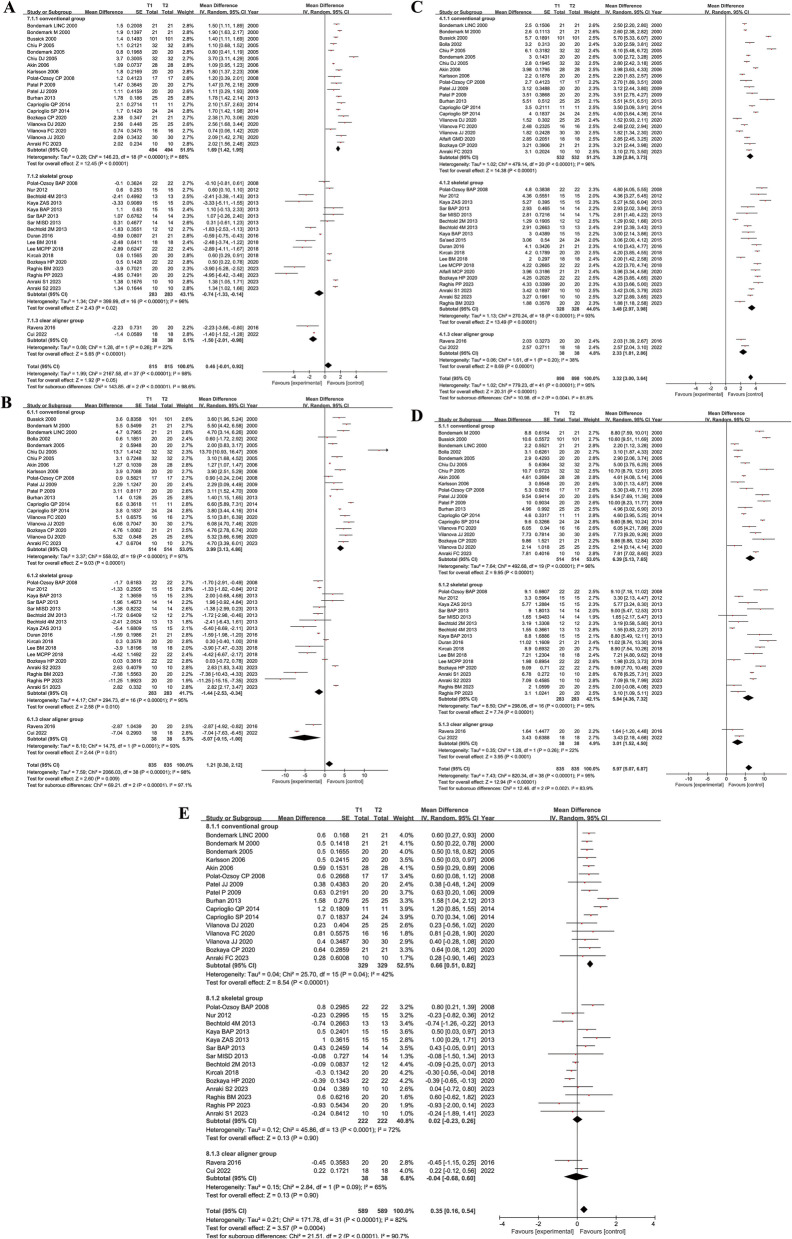

Figure 2 demonstrate the summary data of U6 distalization, U6 distal tipping, incisor mesial tipping, incisor mesial movement and changes in mandibular plane angle for the 3 groups of conventional orthodontic appliance, skeletal orthodontic appliance and clear aligner. The figures provide a weighted mean estimate (last row within each subgroup) and the aggregate P value for each orthodontic appliance. The mean difference, standard error and 95% confidence intervals are displayed for each group.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for molar distalization effect with conventional appliance, skeletal appliance and clear aligner. A incisor mesial movement; B incisor mesial tipping; C U6 distalization; D U6 tipping; E mandibular plane angle change (SN-MP). (+): incisor mesial movement, incisor mesial tipping, U6 distal movement, U6 distal tipping or increase in mandibular plane angle. (-): incisor distal movement, incisor distal tipping, U6 mesial movement, U6 mesial tipping or decrease in mandibular plane angle

High heterogeneity(I2=95%) and significant differences(P=.004) in the amount of U6 distalization were found among conventional(3.29mm; 95% confidence intervals [CI], [2.84, 3.73]; P<.00001; I2=96%), skeletal(3.48mm; 95% CI, [2.97, 3.98]; P<.00001; I2=93%), and clear aligner appliances(2.33mm; 95%CI, [1.81, 2.86]; P=.20; I2=38%). U6 distal tipping demonstrated a statistically significant reduction(P=.002) in the clear aligner group(3.01°; 95%CI, [1.52, 4.50]; P=0.26; I2=22%) compared to other groups, although 2 studies [47, 70] were excluded because the measurements were taken after the second orthodontic phase.

In terms of incisal mesial tipping, high heterogeneity(I2=98%) and significant differences(P<.00001) were found between 3 groups. The incisors showed a mesial tipping in the conventional appliance group (3.99°; 95%CI, [3.13, 4.86]; P<.00001; I2=97%) and a small amount of distal tipping in the skeletal appliance group (−1.44°; 95%CI, [−2.53, −0.34]; P<.00001; I2=95%), and more distal tipping in the clear aligner group(−5.07°; 95%CI, [−9.15, −1.00]; P=.0001; I2=93%). As for incisal mesial movement, the conventional appliance group (1.69mm; 95%CI, [1.42, 1.95]; P<.00001; I2=88%) was significantly different(P<.00001) from the other two groups, which showed mesial movement, while the other two groups showed incisal distal movement.

Mandibular plane angle change, was more increased, significantly(P<.0001), in the conventional appliance group (0.66°; 95%CI, [0.51, 0.82]; P=.04; I2=42%) than in the others.

Figure 3 demonstrates the comparison of the 2-premolar-supported and 4-premolar-supported appliance in 5 areas. U6 distalization (2-premolar-supported VS 4-premolar-supported: 2.72mm VS 4.09mm; P=.007; I2=96%) and U6 distal tipping (4.90°VS 8.24°; P=.005, I2=96%)were significantly different between the two groups. However, incisor mesial tipping (4.40° VS 3.63°; P=.48; I2=97%), incisor mesial movement (1.72mm VS 1.67mm; P=.85; I2=88%) and mandibular plane angle changes (0.53° VS 0.82°; P=.07; I2=42%) were not significantly different between the two groups.

Fig. 3.

2-premolar support VS 4-premolar support anchorage in conventional appliance group

Figure 4 presents a comparison between the eruptive and non-eruptive groups of U7. The differences in U6 distalization (U7-erupted VS U7-unerupted: 3.63mm VS 3.89mm; P=.72; I2=96%), U6 distal tipping (6.35° VS 5.67°; P=.69; I2=97%) and mandibular plane angle changes (0.77° VS 0.50°; P =.18; I2=64%) were not significant between the two groups. Incisor mesial tipping (3.99° VS 2.00°; P=.02; I2=96%) and movement (1.76mm VS 1.1mm; P=.03; I2=70%) were significantly higher in the U7-erupted group than in the U7-unerupted group.

Fig. 4.

U7-erupted VS U7-unerupted subgroups in conventional appliance group

The comparison of buccal, palatal and infrazygomatic miniscrews is shown in Fig. 5. The infrazygomatic miniscrew group had a significantly greater amount (4.9mm; P<.00001; I2=94%) of U6 distalization than the buccal group (2.01mm) and palatal group (3.81mm). The palatal miniscrew group had a significantly higher amount of molar tipping (7.03°; P=.01; I2=95%) and a significantly smaller amount of U1 distal movement (−0.06mm; P<.0001; I2=96%), compared to the other groups. However, there was high heterogeneity (I2=95%) but no significant difference (P=.10) between the buccal-miniscrew group (−3.74°; 95%CI, [−6.52, −0.96]; P=.008; I2=75%), the palatal-miniscrew group (−0.6°; 95%CI, [−2.00, 0.81]; P<.00001; I2=96%), and the infrazygomatic-miniscrew group (−3.03°; 95%CI, [−6.96, 0.91]; P=.02; I2=83%) in incisor mesial tipping. There was also no significant difference (P=.61, I2=72%) between the three subgroups in mandibular plane angle changes, although the buccal subgroup (−0.22°; 95%CI, [−0.78, 0.34]; P=.03; I2=71%) showed a decreasing trend, the palatal (0.04°; 95%CI, [−0.31,0.39]; P=.0003; I2=73%) and the infrazygomatic (0.37°; 95%CI, [−0.84,1.57]; P=.009; I2=85%) subgroups showed an increasing trend.

Fig. 5.

Buccal-miniscrew VS palatal-miniscrew VS infrazygomatic-miniscrew anchorage in skeletal appliance group

Reporting biases and Sensitivity analysis

Table 4 demonstrates the results of the Egger’s test for each synthesis, most of which were not significant (P>.05), indicating no significant reporting bias. However, the P value of the test results of incisal mesial movement and tipping in the conventional group was <.05, so further tests were needed to verify the stability of the results.

Table 4.

Egger’s test for each synthesis

| Group | Subgroup | P |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional group | 1 st movement | 0.041* |

| 1 st tipping | 0.004* | |

| Molar distalization | 0.361 | |

| Molar tipping | 0.629 | |

| SN-MP | 0.923 | |

| Skeletal group | 1 st movement | 0.292 |

| 1 st tipping | 0.253 | |

| Molar distalization | 0.658 | |

| Molar tipping | 0.292 | |

| SN-MP | 0.350 |

Therefore,"Trim and Fill"analysis was performed on both results. The results before and after the analysis were significant (P<.001), indicating that the results were stable, but may have underestimated the amount of anchorage loss.

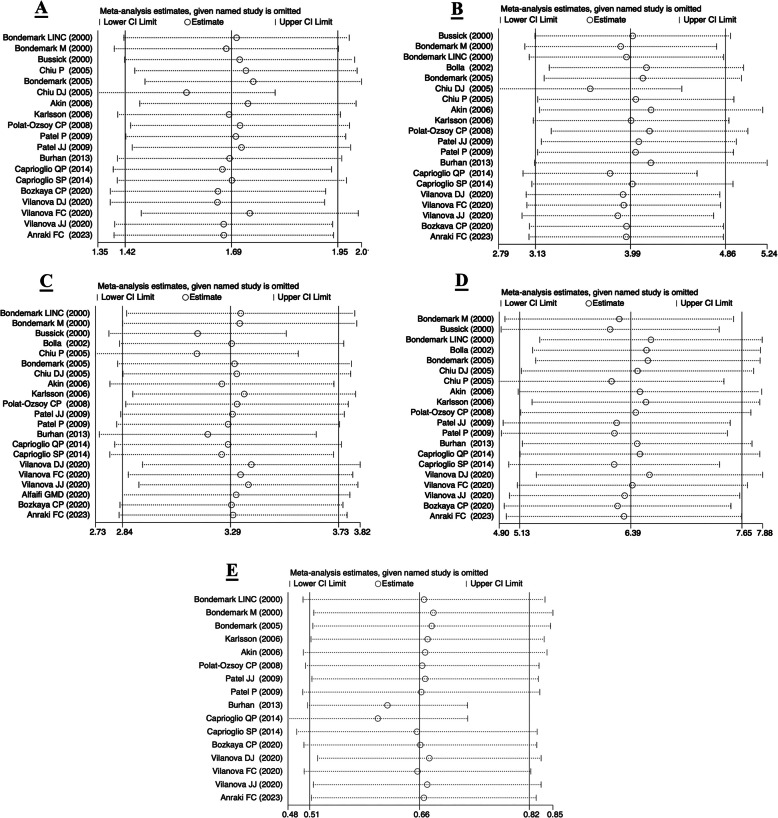

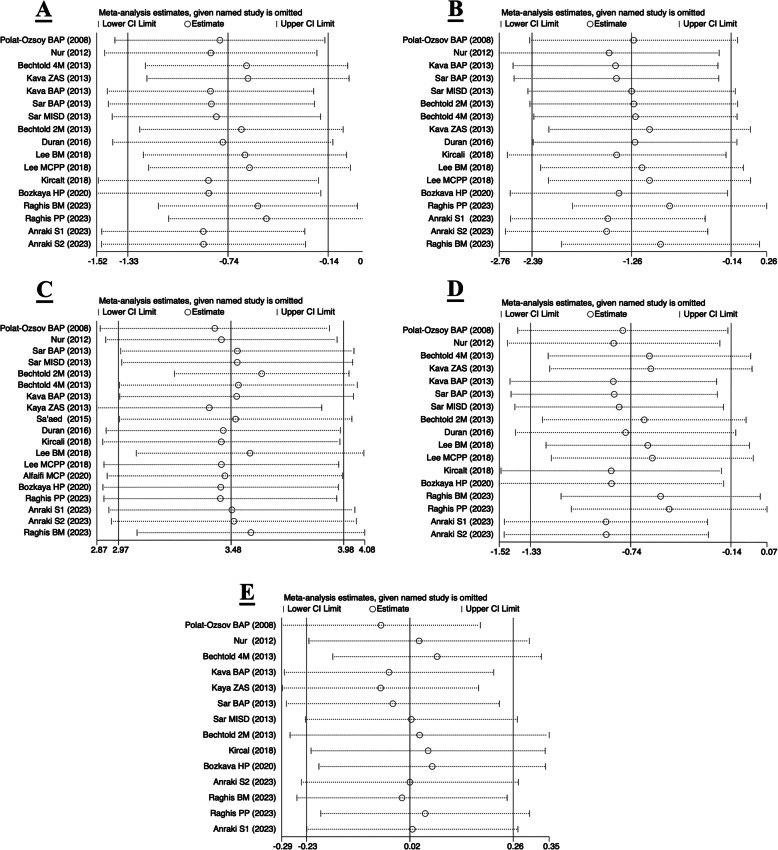

The results of the sensitivity analysis for each group are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The comparison showed that the results did not change significantly after excluding any of the studies, indicating that the results of the original meta-analysis were relatively stable.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the conventional group. A incisor mesial movement; B incisor mesial tipping; C U6 distaliation; D U6 tipping; E mandibular plane angle change (SN-MP)

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis of the skeletal group. A incisor mesial movement; B incisor mesial tipping; C U6 distaliation; D U6 tipping; E mandibular plane angle change (SN-MP)

Discussion

In recent years, an increasing number of patients have expressed the need for non-extraction orthodontic treatment [79]. Consequently, maxillary molar distalization has gained significant attention as a viable treatment option for patients with Angle Class II malocclusion, as it reduces the need for extractions in orthodontic treatment. Various orthodontic appliances and designs have been introduced to avoid the disadvantages associated with traditional methods. With the rise of invisible orthodontics in recent years, its application in molar distalization has also been explored. This study evaluates the efficacy of molar distalization based on the type of orthodontic appliance, amount of anchored teeth, the eruption status of the maxillary second molar, and the position of the miniscrews.

Quality of the studies in this review

The quality of evidence in this study was systematically assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration's ROB 2 tool for RCTs and the ROBINS-I tool for NRCTs. The majority of RCTs were evaluated as having"low"or"some concerns"regarding bias, while NRCTs exhibited a moderate risk of bias, primarily due to confounding variables and measurement of outcomes. To ensure the reliability and validity of the findings, only studies with low to moderate risk of bias were included in the quantitative analysis, thereby increasing the credibility of the results. Futhermore,to validate the robustness of the findings, a publication bias evaluation and sensitivity analysis were conducted. The results indicated no significant publication bias, and the pooled results were found to be robust and reliable. Despite these methodological strengths, the findings highlight the need for additional high-quality RCTs to futher strengthen the evidence base for molar distalization techniques, ensuring that future clinical guidelines and practice recommendations are grounded in the most reliable and comprehensive evidence.

U6 distalization

The meta-analysis revealed that there was no significant difference between the conventional (3.29mm) and skeletal groups (3.48mm) in the amount of U6 distalization, but the invisible appliance group had significantly less distal movement (2.33mm). A previous meta-analysis in 2019 found similar results: with no significant difference in the amount of molar distalization using skeletal (5.35mm) and conventional (4.25mm) anchorage devices [17]. However, Fudalej [80] and Grec [16] concluded that the skeletal group produced more molar distal movement, compared to the conventional group, which is in contrary to our findings. These discrepancies may arise from methodological heterogeneity across studies, including types of studies included and variations in anchorage design.

For instance, the studies included by Fudalej and Grec did not directly compare skeletal group with conventional group, but rather compared each method with untreated control patients, which may have increased possible bias. In contrast, the study included by Soheilifar directly compared the two groups, concluding that both can be successful in molar distalization. Futhermore, differences in anchorage design may contribute to outcome variability. Grec's study did not include patients using buccal miniscrew, while Fudalej’s study included only two cases using buccal miniscrew. In contrast, approximately 20% of the patients included in skeletal group of this study used buccal miniscrew.These findings highlight the necessity for standardized protocols in evaluating molar distalization efficacy across different anchorage systems. Further research is required to better understand the factors contributing to these differences and to establish standardized evaluation criteria for orthodontic anchorage devices.

The results of the subgroup analysis performed within the conventional and skeletal groups were as follows: (i) there was no significant difference (P=.72) in the U6 distalization before and after the eruption of the second molar; (ii) the 4-premolar-support subgroup (3.29mm) might have a greater distal distance than the 2-premolar-support subgroup (2.72mm), which might be related to the fact that the 4 premolars are stronger anchorage for transmitting forces to the molars; (iii) buccal-miniscrew subgroup had a smaller distal distance (2.01mm) than palatal-miniscrew (3.81mm) and infrazygomatic-miniscrew subgroups (4.90mm), which is different from the results of a study by Ceratti [81] (buccal-3.23mm, palatal-3.74mm, zygomatic-3.68mm), but similar to the reviews by Bayome [19] (buccal-2.75mm, palatal-4.07mm, infrazgomatic-4.17mm) and Raghis [82] (buccal-2.44mm, palatal-4mm). A possible explanation is that the restriction of the distance between the buccal miniscrews and the roots may limit the molar distalization.

U6 tipping

Molar distal tipping is a common outcome of molar distalization treatment. No significant differences were found between the conventional appliance (6.39°) and skeletal appliance (5.84°) groups, consistent with the findings of Soheilifar et al. [78]. However, the clear aligner (3.01°) group demonstrated a significant reduction in distal tipping compared to both of these groups. This may be related to the fact that (i) the clear aligner wraps around the molar, exposing it to a mesial tipping force while moving it distally, and (ii) the clear aligner had a significantly longer treatment time, which may have corrected distal tipping in subsequent treatments.

Distal tipping was significantly greater in the palatal-miniscrew subgroup (7.03°), compared to the buccal-miniscrew (3.34°) and infrazygomatic-miniscrew (4.27°) subgroups. This may be due to the fact that many of the appliances [41, 46, 64, 67, 72] used in the palatal subgroup have pendulum arms, which results in a distal tipping because the force is applied to the clinical crowns away from the center of resistance [83]. The 4-premolar-support subgroup had a greater molar tipping than the 2-premolar-support subgroup, which may also be related to that the 4-premolar-support subgroup was better at transmitting the antagonistic forces to the molars. When comparing the distal tipping between the two subgroups before and after the eruption of U7, no significant differences were found (P=.69). This observation aligns with previous findings by Bussick [25], Muse [84], Ghosh and Nanda [27], as well as Karlsson [40], who state that distalization of the maxillary first molars are not dependent on the stage of eruption of the second molar. However, these results contrast with Kinzinger's study [37], which demonstrated greater U6 tipping following molar distalization in the U7 non-erupted group. Notably, Kinzinger's patient sample with erupted U7 and extracted U8 was limited, potentially increasing the likelihood of such outcomes. Futhermore, studies by Longerich [76], Park [85] and Nienkemper [69] on the application of skeletal anchorage for molar distalisation similarly indicated that the eruption status of U7 did not significantly influence U6 tipping post-distalisation. However, well-designed randomized controlled trials may still be necessary to further investigate the potential influence of U7 eruption status and clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Loss of anchorage (Incisor mesial movement and tipping)

There is no standardization regarding the evaluation of anchorage loss. Grec et al. [16] chose the mean of changes in premolar position to determine anchorage loss because they believed that anchorage loss could be underestimated by crowding of the anterior teeth. In the present study, however, incisal mesial movement and tipping were chosen as the criteria for assessing loss of anchorage. For an aesthetic reason——changes in the anterior teeth may affect the soft tissue facial shape of the patient, the mesial movement and tipping of the anterior teeth may increase the patient’s protuberance. Therefore, we chose this criterion for its greater clinical value.

Incisor mesial movement and tipping were significantly less in the clear aligner group(−1.5mm; −5.07°) and the skeletal appliance group(−0.74mm; −1.44°) than in the conventional appliance group(1.69mm; 3.99°), where incisors tended to move and tilt distally. Similar results were found in the studies of Grec et al. [16]and Soheilifar et al. [17] — the skeletal group had less loss of anchorage than the conventional group.

After eruption of the maxillary second molar(1.76mm; 3.99°), the conventional appliance set appeared to produce more significant mesial movement and tipping of the incisors compared to the pre-eruption group(1.10mm; 2.00°). Similar to Kinzinger et al. [37], they found that when the U6 and U7 were moved distally simultaneously, the loss of anchorage increased. A possible explanation was that when U7 erupted, the resistance to distal movement of the molar crown increased, but the orthodontic force was mainly applied to the crown, resulting in a greater loss of anchorage. There was no significant difference between the 4-premolar-support and 2-premolar-support subgroups in terms of anchorage loss. For all palatal-miniscrew devices(−0.06mm; −0.6°), distal movement and tipping were significantly less than for the buccal-miniscrew(−2.52mm; −3.74°) and infrazygomatic-miniscrew(−1.27mm; −3.03°) devices. This may be related to the use of indirect skeletal anchorage in some studies [46, 50, 64, 67, 72] in the palatal subgroup. The reaction forces produced by movement on the anterior teeth or nance buttons, resulting in mesial movement of the anterior teeth due to the lack of osseointegration and bone elasticity or the reduced stiffness of the metal ligature wire [86–88].

Mandibular plane angle changes

There was a tendency for the mandibular plane angle to increase in the conventional appliance group(0.66°) compared to the skeletal appliance group(0.02°) and the clear aligner group(−0.04°). The extrusion of the maxillary molars, together the distal movement of the maxillary molars into the wedge, may be responsible for the increase in vertical facial dimension [6, 25]. The “bite effect” of the clear aligner [56, 89, 90] and the vertical depression component of the skeletal anchorage [91] may provide better control of the stability of the mandibular plane by preventing molar extrusion. No differences were found when comparing the buccal-miniscrew, palatal-miniscrew and infrazygomatic-miniscrew subgroups, the U7 erupted and U7 unerupted subgroups and the 2-premolar-support and 4-premolar-support subgroups.

Clinical implications

This study provides valuable insights for clinicians in selecting and optimizing orthodontic appliances for molar distalization. Conventional, skeletal, and invisible appliances were effective for molar distalization, albeit with distinct performance characteristics. Clear aligners showed minimal molar molar distalization but also reduced anchorage loss, while traditional appliances exhibited the greatest anchorage loss. To mitigate this, the use of miniscrews is recommended, particularly in cases with limited anterior anchorage. Notably, the positioning of miniscrews significantly influenced treatment efficacy; for instance, placement in the infrazygomatic region enhanced molar distalization, whereas palatal placement minimized anchorage loss.

Our study also revealed that traditional appliances anchored with four premolars achieved greater molar distalization and tipping compared to two premolars, although no significant differences were observed in anchorage loss or mandibular plane angle changes. Furthermore, treatment timing relative to molar eruption is critical. Distalizing molars after the eruption of the maxillary second molar may result in greater anterior anchorage loss without significantly improving molar distalization or tipping.

These findings underscore the importance of considering individual patient characteristics, compliance, and treatment preferences when selecting appliances. Clinicians should strategically plan miniscrew placement based on specific anchoring requirements and balance distalization efficacy with anchorage stability. Regular monitoring and adjustments of anchorage systems are essential to ensure optimal treatment outcomes. By integrating patient characteristics, appliance selection, anchorage design, and treatment timing, clinicians can develop more personalized and efficient orthodontic treatment plans.

Limitations and future dierections

This study has several limitations. First, the heterogeneity in this meta-analysis was judged to be high. This may be attributed to differences in the severity of the patient's Class II malocclusion, variations in appliance design, differences in the position of the anchorage and the value of the applied force, different study designs, different patient ages, different measurements and differences in the developmental stage of the molars. Despite efforts to mitigate these issues through subgroup analyses based on study type(Supplementary Figure 1), patient age(Supplementary Figure 2), measurement methodology(Supplementary Figure 3), miniscrew position, second molar eruption status, and the number of anchorage teeth, the heterogeneity persisted across subgroups.Such variability underscores the challenge of achieving uniformity in clinical studies, particularly in orthodontics, where treatment protocols are often tailored to individual patient needs. While standardized sample characteristics and treatment designs would enhance comparability, the practical difficulties in recruiting homogeneous patient cohorts and the inherent uniqueness of orthodontic treatments render this objective particularly demanding. Consequently, controlling for heterogeneity in clinical trials remains a significant challenge, highlighting the imperative need for more rigorous standardization and confounding control in future investigations. Additionally, meta-analysis of single-arm studies may be questioned due to potential bias and diversity in study design [92]. These issues may interfere with effect estimates, so the results should be interpreted with caution.

Futhermore, only three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this systematic review, and the majority of the studies were prospective or retrospective, which may limit the robustness of the findings. Although the included studies provided valuable insights into the comparative efficacy of conventional, skeletal, and invisible orthodontic techniques, the risk of bias assessment revealed that only a small proportion of studies were deemed to be at low risk of bias. This issue was particularly evident in the clear aligner group, which included only two moderate-risk publications, potentially reducing the representativeness of the sample.

Another limitation is the applicability of the findings, which is primarily limited to non-extraction treatments for Angle Class II malocclusion patients. The study population predominantly consisted of adolescents and young adults, which may restrict the generalization of the results to other age groups or demographics. While the consistent distalization effects observed across different orthodontic appliances suggest reasonable applicability to similar clinical scenarios, broader generalization remains challenging.

To address these limitations, future research should prioritize the implementation of standardized methodologies, rigorous control of confounding variables, and the conduct of well-designed RCTs with larger, more diverse sample populations. Expanding the demographic scope to include varied age groups and ethnic backgrounds would enhance the generalizability of findings. Futhermore, Subgroup analyses based on factors such as second molar eruption status, number of anchored teeth, and miniscrew positions could provide further clarity for clinical applications. The adoption of standardized reporting and measurement techniques is also essential to improve the feasibility and reliability of meta-analyses. By addressing these methodological challenges, future research can yield more reliable and widely applicable evidence to guide clinical practice.

Conclusions

Based on the low to moderate quality evidence assessed by the available GRADE, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The amount of molar distalization and molar tipping was significantly less in the clear aligner group than in the conventional appliance and skeletal appliance groups. The conventional appliance group had a significantly greater loss of anchorage than the skeletal appliance and clear aligner groups. There was a tendency for the mandibular plane angle to increase in the conventional appliance group compared to the skeletal appliance group and the clear aligner group.

Molar distalization after eruption of the maxillary second molar may produce greater loss of anchorage when conventional appliances were used, but does not produce a more significant amount of molar distalization, distal tipping or change in mandibular plane angle.

When using conventional appliances, the 4-premolar-support group appeared to produce more molar distal movement and tipping than the 2-premolar-support group, but no significant differences were observed in anchorage loss and mandibular plane angle changes.

When comparing the miniscrew positions, the buccal-miniscrew subgroup had the smallest amount of U6 distalization, while the palatal-miniscrew subgroup had the largest amount of U6 distal tipping and the smallest amount of incisor distal movement and tipping.

Further well-designed, high-quality RCTs or prospective studies are needed to provide more qualitative evidence and more robust results for efficacy of conventional and invisible orthodontic techniques for molar distalization.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Subgroup analysis of study type in conventional and skeletal appliance groups.

Supplementary Material 2. Subgroup analysis of patient age in conventional and skeletal appliance groups.

Supplementary Material 3. Subgroup analysis of measurement methodology in conventional and skeletal appliance groups.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Y.H., Y.W. and Y.L.1 obtained and analyzed the data. Y.H. was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. X.S. and Y.L.2 have made substantial contributions to the design of the work and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yanfang Wang and Yutong Lu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lombardo G, Vena F, Negri P, Pagano S, Barilotti C, Paglia L, et al. Worldwide prevalence of malocclusion in the different stages of dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2020;21(2):115–22. 10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.02.05. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=32567942&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keim RG, Berkman C. Intra-arch maxillary molar distalization appliances for class ii correction. J Clin Orthod. 2004;38(9):505–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=15467169&query_hl=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janson G, Maria FRT, Barros SEC, de Freitas MR, Henriques JFC. Orthodontic treatment time in 2- and 4-premolar-extraction protocols. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5):666–71. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.12.026. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0889540606000126.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bondemark L, Karlsson I. Extraoral vs intraoral appliance for distal movement of maxillary first molars: a randomized controlled trial. Angle Orthod. 2005;75(5):699–706. Available from: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L41297030&from=export. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinzinger GSM, Eren M, Diedrich PR. Treatment effects of intraoral appliances with conventional anchorage designs for non-compliance maxillary molar distalization. A literature review. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30(6):558–71. 10.1093/ejo/cjn047. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/gvwXm28T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontana M, Cozzani M, Caprioglio A. Soft tissue, skeletal and dentoalveolar changes following conventional anchorage molar distalization therapy in class ii non-growing subjects: a multicentric retrospective study. Prog Orthod. 2012;13(1):30–41. 10.1016/j.pio.2011.07.002. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1723778511000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonarakis GS, Kiliaridis S. Maxillary molar distalization with noncompliance intramaxillary appliances in class ii malocclusion. A systematic review Angle Orthod. 2008;78(6):1133–40. 10.2319/101507-406.1. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/g1NqKsL6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branemark PI. Osseointegration and its experimental background. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;50(3):399–410. 10.1016/s0022-3913(83)80101-2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=6352924&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Kyung HM, Zhao WT, Yu WJ. Critical factors for the success of orthodontic mini-implants: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(3):284–91. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.08.017. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0889540608008603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanomi R. Mini-implant for orthodontic anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 1997;31(11):763–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=9511584&query_hl=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng SJ, Tseng IY, Lee JJ, Kok SH. A prospective study of the risk factors associated with failure of mini-implants used for orthodontic anchorage. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004;19(1):100–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=14982362&query_hl=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA, Bourauel C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner technique–regarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar distalization. Bmc Oral Health. 2014;14(1):68–74. 10.1186/1472-6831-14-68. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=24923279&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng M, Liu R, Ni Z, Yu Z. Efficiency, effectiveness and treatment stability of clear aligners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2017;20(3):127–33. 10.1111/ocr.12177. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=28547915&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koletsi D, Iliadi A, Eliades T. Predictability of rotational tooth movement with orthodontic aligners comparing software-based and achieved data: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Orthod. 2021;48(3):277–87. 10.1177/14653125211027266. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=34176358&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haouili N, Kravitz ND, Vaid NR, Ferguson DJ, Makki L. Has invisalign improved? A prospective follow-up study on the efficacy of tooth movement with invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158(3):420–5. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.12.015. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889540620303036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grec RHDC, Janson G, Branco NC, Moura-Grec PG, Patel MP, Castanha Henriques JF. Intraoral distalizer effects with conventional and skeletal anchorage: a meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143(5):602–15. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.11.024. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889540613000723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soheilifar S, Mohebi S, Ameli N. Maxillary molar distalization using conventional versus skeletal anchorage devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthod. 2019;17(3):415–24. 10.1016/j.ortho.2019.06.002. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1761722719300774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellini-Pereira SA, Pupulim DC, Aliaga-Del Castillo A, Henriques JFC, Janson G. Time of maxillary molar distalization with non-compliance intraoral distalizing appliances: a meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2019;41(6):652–60. 10.1093/ejo/cjz030. Available from: http://pku.summon.serialssolutions.com/2.0.0/link/0/eLvHCXMwtV1bb9MwFLa68QAvaNzHABkh8RJlS-xcHCQeqq4VQgWG6CTeIjtxRrY2rdoGAb-ec2InbUGTxgMvUZSLZdmfjs_1O4Rwduy5f8iEgOd-LKICzxeZREWQqzgJZa6iTPlaNdXSH8T4jI2G4fter6V03Tz7rxsPz2DrsZD2Hza_GxQewD1AAK4AArjeDAblrPEKzOQP7C-0_OnM0JjFwAxyH5oiTOONreaVazLMmzKCEt2-Tf1--21Tz7iw71emTHqm19KVltnkWje_VXkxRgRmcLXeSrHHAqGyKt0zvdRl0_TI-VJOv5dzp19f1KCadsK7XtRT0_vZ1MVLZ1Ar2Q3Uh3ldSPdUT52BBMFlg0r95SbRACsykK-2jX2YLAHH-tLnzX-y-ia3XSF-gjWBphj0WBvxHUSey5hNlLXy3RBrWRxvC-vIcOfacz8yfQ3-OlIM3Za-hDmPsstfng0j7TB3f_yUjs7H43Qy_Dp5jZzts7zM1m915darPXKLYd8ITBj4vGGy56AWtHS5CT-B8U_M6LsK0jVWT6P9TA7IXWu20L4B2D3S09V9cvsUU82wW-ADcoVAo_OCdkCjDdDoDtAoAo3uAo12QKNbQKMboL2hku7A7CE5Hw0ng3eubeThZtxjazeMClaAGSfAdo3y2NM84JmXCDBNRKyF0opnkuVMqVAoMMB9Bm-lYJnyhAzgEHpE9mFq-gmhYS59FcUqCrUK8lzIQnJPZFokKsdOCYfkVbt66cLwtaQmz4KnsMapWeND8rJd2BTEKcbIZKXn9SoFbZl56LOAbx6bFe_G4egrSQL29AZ_H5E7G4Q-I_vrZa2fk73FVf2iwcFvqaSo3w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayome M, Park JH, Bay C, Kook YA. Distalization of maxillary molars using temporary skeletal anchorage devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2021;24(1):103–12. 10.1111/ocr.12470. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ocr.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj. 2009;339(1):b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372(1):n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterne J, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2019;366(1):l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=31462531&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonathan AS, Miguel AH, Barnaby CR, Jelena S, Nancy DB, Meera V, et al. Robins-i: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Bmj. 2016;355(1):i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/355/bmj.i4919.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papageorgiou SN. Meta-analysis for orthodontists: part i – how to choose effect measure and statistical model. J Orthod. 2014;41(4):317–26. 10.1179/1465313314Y.0000000111. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/1465313314Y.0000000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bussick TJ, McNamara JA. Dentoalveolar and skeletal changes associated with the pendulum appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117(3):333–43. 10.1016/S0889-5406(00)70238-1. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/3hfqsl2J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bondemark L. A comparative analysis of distal maxillary molar movement produced by a new lingual intra-arch ni-ti coil appliance and a magnetic appliance. Eur J Orthod. 2000;22(6):683–95. 10.1093/ejo/22.6.683. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/h3TCncmv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh J, Nanda RS. Evaluation of an intraoral maxillary molar distalization technique. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110(6):639–46. 10.1016/S0889-5406(96)80041-2. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/TYNmDbwx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byloff FK, Darendeliler MA. Distal molar movement using the pendulum appliance. Part 1: clinical and radiological evaluation. Angle Orthod. 1997;67(4):249–60. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/8ZhJhsjN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byloff FK, Darendeliler MA, Clar E, Darendeliler A. Distal molar movement using the pendulum appliance. Part 2: the effects of maxillary molar root uprighting bends. Angle Orthod. 1997;67(4):261–70. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/cf8QK4jM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brickman CD, Sinha PK, Nanda RS. Evaluation of the jones jig appliance for distal molar movement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118(5):526–34. 10.1067/mod.2000.110332. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889540600389260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burhan AS. Combined treatment with headgear and the frog appliance for maxillary molar distalization: a randomized controlled trial. Korean J Orthod. 2013;43(2):101–9. 10.4041/kjod.2013.43.2.101. Available from: https://synapse.koreamed.org/x.php?id=10.4041/kjod.2013.43.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadopoulos MA, Melkos AB, Athanasiou AE. Noncompliance maxillary molar distalization with the first class appliance: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137(5):581–6. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.10.033. Available from: http://pku.summon.serialssolutions.com/2.0.0/link/0/eLvHCXMwnV1dS8MwFA26F33x-2M6JT_ASdr0K75NtyGiIqgvvoQ0SWG6dWPdQP313pu2CkMFfSspadPcm-SkPT2HEO6fsvbCnBACqreByLgOjE0BYvPAMs0CpZVnMmca8XSTXN_5_V54Ve0bi2--6DtmlnqGHVspNYnELI5anyjjhSKP3fMvyd2gFGVEHg_gkqjWHPr-Gj-tS4sT9QL8dMtQf_2vLd4gaxXgpJ0yQzbJks23yEoXSULo87ZNBrfjvCSWYwLQkXpFI6LpGx3hrpcaBJjD6m9Niq9tKWBG2h8AbKTOUpM6JIuVz2iHwtpnxqPBuzW0osEP4dCZg-yQx37v4eKyXRkwtHXA_VnbCJukGUr8scBArDTgLRULYVIv0YmyALYiPxVeplJPJ4nyQ8XSSHEoinUaa75LGvk4t_uE8lhoL4H9tkFFQgh7FkXK2BDQUcaEb5vkpO5-OSl1NmRNQHuWrv_QMVNgIfRfk8R1iGT9CylMeraoRmAhPVn4ksl7DD9G333H4BHUjD5rViCjBA8Swvb7LVuYChIH_myKrlCFlh2YDhMAYRFrElqniMRTyF3L7XheyJhzEQrGgybZK1Pn8wnRC8ADAH7w30YdktWazsC8FmnMpnN7RJYnL_NjNxg-AL59CYQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keles A, Sayinsu K. A new approach in maxillary molar distalization: intraoral bodily molar distalizer. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117(1):39–48. 10.1016/S0889-5406(00)70246-0. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/4qfWDmNT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolla E, Muratore F, Carano A, Bowman SJ. Evaluation of maxillary molar distalization with the distal jet: a comparison with other contemporary methods. Angle Orthod. 2002;72(5):481–94. 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072%3c0481:EOMMDW%3e2.0.CO;2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=12401059&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taner TU, Yukay F, Pehlivanoglu M, Cakirer B. A comparative analysis of maxillary tooth movement produced by cervical headgear and pend-x appliance. Angle Orthod. 2003;73(6):686–91. 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073%3c0686:ACAOMT%3e2.0.CO;2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=14719733&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortini A, Lupoli M, Giuntoli F, Franchi L. Dentoskeletal effects induced by rapid molar distalization with the first class appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;125(6):697–704. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.06.006. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/68gg1PCx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinzinger GSM, Fritz UB, Sander F, Diedrich PR. Efficiency of a pendulum appliance for molar distalization related to second and third molar eruption stage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;125(1):8–23. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.02.002. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/w7Dj4nYV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu PP, McNamara JA, Franchi L. A comparison of two intraoral molar distalization appliances: distal jet versus pendulum. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128(3):353–65. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.04.031. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889540605004270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akin E, Gurton AU, Sagdic D. Effects of a segmented removable appliance in molar distalization. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28(1):65–73. 10.1093/ejo/cji078. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=16436365&query_hl=1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlsson I, Bondemark L. Intraoral maxillary molar distalization: movement before and after eruption of second molars. Angle Orthod. 2006;76(6):923–9. 10.2319/110805-390. Available from: https://meridian.allenpress.com/angle-orthodontist/article/76/6/923/57847/Intraoral-Maxillary-Molar-DistalizationMovement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polat-Ozsoy Ö, Kırcelli BH, Arman-Özçırpıcı A, Pektaş ZÖ, Uçkan S. Pendulum appliances with 2 anchorage designs: conventional anchorage vs bone anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133(3):339. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.002. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S088954060701027X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel MP, Janson G, Henriques JFC, de Almeida RR, de Freitas MR, Pinzan A, et al. Comparative distalization effects of jones jig and pendulum appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(3):336–42. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.01.035. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889540608008329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caprioglio A, Cozzani M, Fontana M. Comparative evaluation of molar distalization therapy with erupted second molar: segmented versus quad pendulum appliance. Prog Orthod. 2014;15(1):49–58. 10.1186/s40510-014-0049-6. Available from: https://progressinorthodontics.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40510-014-0049-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]