Abstract

Background

Site-specific recombination (SSR) systems are essential tools for conditional genetic manipulation and are valued for their efficacy and user friendliness. However, the development of novel SSR strategies is urgently needed. This study aimed to identify a split Dre protein configuration that can self-activate.

Results

By exploiting the homology between Dre and Cre, we designed a strategy to split the Dre protein at specific amino acid residues and systematically pair the resulting peptide fragments. Among these combinations, the N191/192C pair exhibited detectable recombinase activity when mediating recombination between episomal rox sites in 293T cells, whereas the other pairs presented minimal recombinase activity. Subsequent experiments revealed that the N191/192C combination efficiently mediated site-specific recombination at the integrated rox sites, without the need for auxiliary protein fusions, and demonstrated recombinase activity that is at least equivalent to that of the intact Dre protein. Interestingly, while fusion with the intein peptide increased the activity of N60/61C pair, it had a deleterious effect on the N191/192C pair. The N191/192C combination also displayed robust recombinase activity in both the murine 4T1 cell line and E. coli bacteria. Finally, our experiments demonstrated that there was no detectable cross-complementation between the split Dre and split Cre proteins.

Conclusions

The N191/192C split Dre protein and the intein-fused N60/61C split Dre protein can effectively mediate recombination of the integrated rox sites without the need for external signals such as light or chemical compounds. Split Dre and Cre proteins can be used together in the same cell without interfering with each other. These findings introduce new tools and strategies for gene editing and the generation of transgenic animals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13036-025-00551-7.

Keywords: Dre, Site-specific recombination, Protein fragment complementation

Background

DNA site-specific recombination (SSR) systems are effective and easy to use in conditional genetic modifications. They are widely used in synthetic biology, conditional knockout or knock-in, inversion and transposition mutagenesis of DNA, and labeling of cell lineages [1]. Many recombinases, such as Cre, VCre, SCre, Flp, phiC31, Dre, Nigri and Vika [2–9], are well established. New types of recombinase are being identified or developed [10].

However, the application of site-specific recombinases is still subject to some technical limitations. First, the nonspecific expression of genes encoding recombinases leads to off-target recombination in other cell types [11]. Secondly, if the gene driving recombinase expression manifests transient expression in germ cells, the mice that were designed for conditional gene knockout unexpectedly become subject to systemic gene knockout [12–14]. We and other researchers have also reported off-target recombination in non-Treg cells and germline recombination in the Foxp3YFP-Cre mouse line [15, 16]. Third, the overexpression of recombinases can be toxic to cells, potentially causing cell death or inhibiting growth [17, 18].

To achieve enhanced temporal and spatial control of DNA recombination in target cells, numerous strategies have been devised. Some researchers have developed chemical- and light-inducible genetic systems to precisely control the timing and specificity of genetic modifications [19, 20]. Another approach involves the use of dual recombinase systems, which can offer a relatively high degree of control over recombination events [21]. For instance, the combination of Cre and Dre recombinases has been employed to achieve more precise cell lineage tracing and functional studies in vivo [22–24]. One innovative strategy involves the use of split recombinases, where the enzyme is divided into two parts that only become active upon reassembly, thereby increasing specificity and control. This approach has been successfully applied to enhance the precision of genetic manipulations and minimize off-target effects [25–27]. However, these strategies are insufficient to meet al.l requirements, particularly when a cell needs to be specifically labeled by three or more proteins. For example, there is a lack of unambiguous markers to distinguish between tTreg cells and pTreg cells [28]. When investigating gene function in one of these cell types in vivo, the combination of split Cre and Dre is not adequate. Moreover, when tracking multiple cell types within the same organism simultaneously, additional manipulative techniques are required. Therefore, the development of additional strategies utilizing recombinases is essential.

Like Cre, Dre recombinase is a highly efficient site-specific recombinase that targets a 32-base pair sequence named rox [7]. It has been pivotal in advancing the development of sophisticated genetic tools designed for precise cell labeling and manipulation [22, 23]. Furthermore, photoactivatable Dre recombinase has been engineered by splitting the enzyme into two parts, each fused to a distinct photoresponsive protein, enabling spatiotemporal control of gene expression in mouse tissues upon light exposure [29, 30]. Despite these advancements, a version of the split-Dre recombinase that can autonomously activate remains to be developed. In this study, we present an innovative strategy involving the cleavage of Dre recombinase between G191 and D192. This cleavage yields two peptides that are competent for fragment complementation activity in both mammalian cells and E. coli, without the necessity for heterodimerizing peptides.

Methods

Primers, plasmids, bacterial strains, and cell lines

A detailed list of the primers utilized in the present study can be found in Table S1. A collection of plasmids essential for our experiments was procured from Hunan Fenghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China. These included pEGFP-N1, pCAG-Cre: GFP, pUC19, pACYC177, pcDNA™3.1/myc-His A, pSPAX2, pMD2.G, pLVX-IRES-Puro, pLVX-IRES-mCherry, and pLVX-IRES-BFP. Notably, the plasmid pUC57-intein, which contains the sequences of intein, was synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., China. Additionally, we used the following Addgene plasmids as generous gifts from Pawel Pelczar [21]: pCAG-NLS-HA-Dre (Addgene plasmid # 51272), pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen (Addgene plasmid # 51274), and pCAG-loxPSTOPloxP-ZsGreen (Addgene plasmid # 51269). The E. coli strain DH5α was utilized as a general cloning host for molecular cloning and β-galactosidase activity assays. The human embryonic kidney cell line 293T was used to evaluate the recombinase activity of Dre and Cre, as well as for virus packaging. 4T1 mouse mammary carcinoma cells were used to assess the recombinase activity of Dre and Cre.

Culture and growth conditions

The Escherichia coli strain DH5α was cultured in Luria broth (LB) media and on LB agar plates at 37 °C. For plasmid maintenance, the growth medium was supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/ml) and/or kanamycin (25 µg/ml) as specified in the experimental procedures. In addition, 293T cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). 4T1 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). Both cell lines were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

DNA constructs

pLVX-IRES-Puro-roxEGFP(rox) vector construction

The EGFP cassette, flanked by two opposing rox sequences, was PCR-amplified from pEGFP-N1 via primers (rox)-F and (rox)-R. The products were subsequently cloned and inserted into pLVX-IRES-Puro at the XhoI and BamHI sites via the Seamless Cloning Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

pcDNA™3.1/myc-His a vectors for Dre and Cre genes and variants

We constructed pcDNA™3.1/myc-His A vectors containing Dre and Cre genes and their variants via PCR amplification from pCAG-NLS-HA-Dre and pCAG-Cre plasmids, respectively. The primers used are listed below, and the products were subsequently cloned and inserted into pcDNA™ 3.1/myc-His A at the EcoRI and XbaI sites.

Dre Gene Variants: Dre-F and Dre-R (Dre gene, Nc), Dre-F and Dre60-R (N60), Dre-F and Dre157-R (N157), Dre-F and Dre191-R (N191), Dre-F and Dre233-R (N233), Dre-F and Dre245-R (N245), Dre-F and Dre282-R (N282), 61Dre-F and Dre-R (61C), 158Dre-F and Dre-R (158C), 192Dre-F and Dre-R (192C), 234Dre-F and Dre-R (234C), 246Dre-F and Dre-R (246C), 283Dre-F and Dre-R (283C).

Cre Gene Variants: Cre-F and Cre-R (Cre gene, Nc), Cre-F and Cre59-R (N59), Cre-F and Cre190-R (N190), 60Cre-F and Cre-R (60C), 191Cre-F and Cre-R (191C).

The pLVX-IRES vectors with the Dre gene and variants

pLVX-IRES-mCherry and pLVX-IRES-BFP vectors containing the Dre gene and its derivatives were constructed via PCR amplification from pCAG-NLS-HA-Dre. The primers used were as follows, and the products were subsequently cloned and inserted into the respective vectors at the EcoRI and XbaI sites.

pLVX-IRES-mCherry: Dre-F and Dre-R (Dre gene, NC), NLSDre-F and Dre-R (NNC), NLSDre-F and DreNLS-R (NNCN), NLSDre-F and Dre60-R (NN60), NLSDre-F and Dre191-R (NN191).

pLVX-IRES-BFP: 61Dre-F and Dre-R (61C), 61Dre-F and DreNLS-R (61CN), 192Dre-F and Dre-R (192C), 192Dre-F and DreNLS-R (192CN).

pLVX-IRES vectors with Dre variants and intein

We constructed pLVX-IRES-mCherry and pLVX-IRES-BFP vectors with Dre variants fused to intein via seamless cloning. The primers used for the Dre and intein fragments are detailed below, and the products were subsequently cloned and inserted into the respective vectors at the EcoRI and XbaI sites.

NN60nI: S-NLSDre-F and Nintein-Dre60-R (Dre), Dre60-Nintein-F and S-Nintein-R (intein).

NN191nI: S-NLSDre-F and Nintein-Dre191-R (Dre), Dre191-Nintein-F and S-Nintein-R (intein).

Ic61C: Cintein-61Dre-F and S-Dre-R (Dre), S-Cintein-F and 61Dre-Cintein-R (intein).

Ic192C: Cintein-192Dre-F and S-Dre-R (Dre), S-Cintein-F and 192Dre-Cintein-R (intein).

Ic61CN: Cintein-61Dre-F and S-NLSDre-R (Dre), S-Cintein-F and 61Dre-Cintein-R (intein).

Ic192CN: Cintein-192Dre-F and S-NLSDre-R (Dre), S-Cintein-F and 192Dre-Cintein-R (intein).

pUC19 vectors with Dre variants

pUC19 vectors incorporating Dre variants were generated via seamless cloning. The primers used for amplification were as follows, and the products were cloned and inserted into pUC19 at the BamHI and EcoRI sites.

Dre gene (nc): p19-Dre-F and p19-Dre-R.

N60-61C: p19-Dre-F and p19-Dre60-R (N-terminal), p19-61Dre-F and p19-Dre-R (C-terminal).

N191-192C: p19-Dre-F and p19-Dre191-R (N-terminal), p19-192Dre-F and p19-Dre-R (C-terminal).

pACYC177-roxLacZα(rox) vector construction

The LacZα cassette, flanked by two opposing rox sequences, was PCR-amplified from pUC19 via (rox)LacZ-F and (rox)LacZ-R. The products were subsequently cloned and inserted into pACYC177 at the PstI site via the Seamless Cloning Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China).

Cell line generation

Lentivirus for EGFP expression was generated by co-transfecting 293T cells with the plasmids pLVX-IRES-Puro-roxEGFP(rox), psPAX, and pMD2.G at a ratio of 4:3:1. Stable cell lines expressing the reverse EGFP gene were established in 293T and 4T1 cells via lentiviral-mediated transduction. Following transduction, cells were selected for stable integration through puromycin (6 µg/ml) selection for three weeks to ensure long-term expression of the transduced gene.

Flow cytometry analysis of EGFP/ZsGreen-expressing 293T or 4T1 cells

Single-cell suspensions of transfected 293T and 4T1 cells were prepared and washed once with PBS. The samples were analyzed using a BD LSRFortessa™ flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo (BD, v10.8.1). The percentage of EGFP/ZsGreen-expressing cells was compared by concatenating the samples of live transfected cells.

Recombinase activity assay for Dre, Cre and their derivatives

Plasmids encoding Dre, Cre, and their derivatives, at a concentration of 0.5 µg/24well, were transfected into 293T or 4T1 cells utilizing the jetPRIME® reagent (Polyplus). Following transfection, the proportion of cells expressing fluorescent proteins was assessed by flow cytometry at designated time intervals. The fluorescence intensity within transfected 293T cells was quantified using the Spark multimode microplate reader (Tecan). Additionally, representative images were acquired through an Olympus CKX53 inverted microscope equipped with a DP22 camera and CellSens software.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (P0013B; Beyotime Biotechnology, China) to extract total protein. The lysates were subsequently homogenized and centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4 °C for 15 min to remove cellular debris. The supernatants were collected for further analysis. The samples were analyzed by western blotting using the standard procedures [31]. The targeted protein was detected by immunoblot with the following primary antibodies: anti-Dre (NBP3-11868; Novus Biologicals, CO, USA) and anti-β-Tubulin (TA-10; ZSGB-Bio, China), which served as a loading control. ECL western blotting detection reagents (PK1003; Proteintech, China) were used to visualize the protein bands, and the images were captured using a Tanon 5500 Chemiluminescent Imaging System.

β-galactosidase activity assay

The β-galactosidase activity of the Escherichia coli strain DH5α harboring the plasmids described in the text was determined according to the protocol of the β-Galactosidase Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China), with slight modifications. Active bacterial proteins were extracted from 0.2 mL of bacterial cultures via BeyoLytic™ Bacterial Active Protein Extraction Reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). The samples were incubated with the β-galactosidase detection reagent for a period of 4 h. The samples were subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min in a microcentrifuge to pellet the cell debris. The absorbance of the supernatant at 420 nm (A420) was then measured to quantify the β-galactosidase activity, with a blank control prepared from the parental strain without a plasmid used to account for background absorbance. For β-galactosidase activity assays on LB plates, X-Gal was added.

Results

Identification of constitutively active split Dre protein combinations in 293T cells

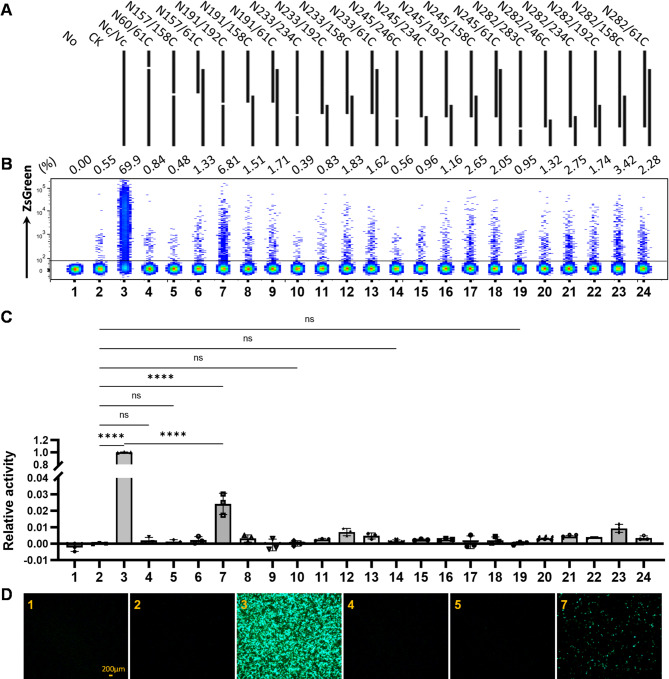

Dre is a protein that shares 40% sequence similarity with Cre (Figure S1). The predicted protein structures of Dre and Cre, as determined by AlphaFold [32], are also highly similar (Figure S1). To develop a split Dre protein pair that exhibits recombinase activity without light or chemical induction, we selected split sites based on previously reported Cre split schemes that retain recombinase activity [25, 33–35]. Through homologous sequence alignment, we chose to split Dre after the 157th, 191st, 233rd, 245th, and 282nd amino acids (Figure S1). Additionally, the split pair after the 60th amino acid of Dre was selected as a negative control, as Dre split at this site lacks recombinase activity [29]. Consequently, we obtained the N-terminal fragments: N60, N157, N191, N233, N245, and N282; and the C-terminal fragments: 61C, 158C, 192C, 234C, 246C, and 283C (Fig. 1A). Each encoding sequence of these fragments was individually cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1/Myc-HisA. Specifically, a stop codon was introduced at the terminal end of the coding sequence for the N-terminal fragment. Conversely, an ATG start codon was incorporated at the initial end of the coding sequence for the C-terminal fragment.

Fig. 1.

Recombinase activity of split-Dre pairs in 293T cells. (A) Schematic illustration of the co-transfection strategy for split-Dre pairs with the pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen plasmid in 293T cells. No, no plasmid transfection; CK, pcDNA™3.1/myc-His A; Nc/Vc, full-length Dre and pcDNA™3.1/myc-His A. In each sample, the three plasmids were transfected into 293T cells at a mass ratio of 1:1:1. (B) Proportion of ZsGreen-positive cells among live cells, determined by flow cytometry 48 h post-transfection. (C) Quantification of fluorescence intensity in all cells, measured using a microplate reader 48 h post-transfection. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. Statistical significance: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. (D) Fluorescence microscopy images of selected samples, captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope 48 h post-transfection

After the split Dre fragments were cloned and inserted into the vector, we paired complementary or overlapping N-terminal and C-terminal fragments (Fig. 1A) and co-transfected them with the pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen plasmid, which contains rox sites in the same orientation and prevents ZsGreen expression in the absence of recombination, into 293T cells. The fluorescence intensity and proportion of green fluorescent protein-expressing cells were assessed 48 h post-transfection.

The results indicated that intact Dre enabled green fluorescent protein expression in approximately 70% of the cells. In contrast, all split Dre combinations resulted in green fluorescent protein expression in fewer than 10% of the cells. This suggests that the recombinase activity of the split Dre combinations in mediating recombination between episomal rox sites is significantly reduced compared with that of intact Dre. Notably, the N191/192C combination exhibited some recombinase activity, enabling 7% of the cells to express green fluorescent protein (Fig. 1B), with significant differences in fluorescence intensity compared with that of the controls (Fig. 1C), and green fluorescence was observable under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 1D; Supplementary Figure S2). However, other combinations involving N191 or 192C did not exhibit recombinase activity, suggesting that these fragments cannot complement each other and are inactive individually.

To determine whether the N191/192C combination mediates inversion reactions via rox site recombination more efficiently than deletion reactions, we co-transfected 293T cells with the N191/192C combination and two plasmids. One plasmid was pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen, which contains direct repeat rox sequences and expresses ZsGreen only upon rox site recombination. The other plasmid was pLVX-IRES-Puro-roxEGFP(rox), containing inverted repeat rox sequences and expressing EGFP only upon rox site inversion (Figure S3A). Forty-eight hours after transfection, we measured the proportion of cells expressing green fluorescence in each sample. The results revealed that the N191/192C combination exhibited significantly lower activity than the intact Dre protein in mediating both deletion and inversion reactions via episomal rox site recombination, with an activity level of approximately 10% of that of the intact Dre protein (Supplementary Figure S3). This suggests that the N191/192C combination does not significantly differ in efficiency from the intact Dre recombinase when mediating episomal rox site recombination, regardless of whether it is a deletion or inversion reaction. However, both efficiencies are significantly lower than that of the intact Dre protein.

Efficient site-specific recombination is mediated by split Dre proteins in rox site-stable 293T cells

To simulate the physiological process of Dre-mediated recombination at the rox site in genomic DNA, we generated a stable 293T cell line containing the integrated rox site via lentiviral construction. Previously, we observed significant leakage expression of ZsGreen when the pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen plasmid was transiently transfected into 293T cells, despite the presence of a transcriptional terminator upstream of the ZsGreen gene. Given that this leakage expression would severely confound the interpretation of our results, we constructed the stable cell line using plasmid pLVX-IRES-Puro-roxEGFP(rox) (Supplementary Figure S3A).

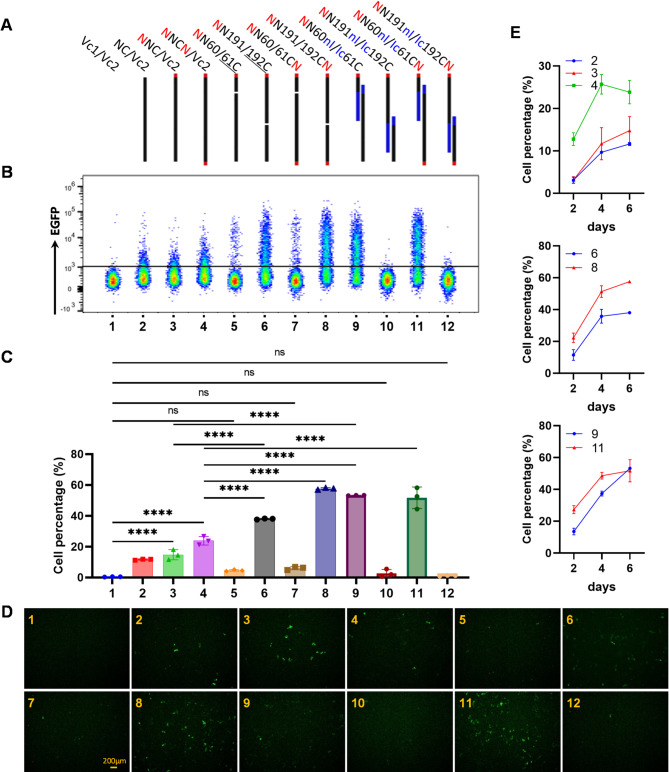

To account for transfection efficiency and ensure co-localization of N-terminal and C-terminal fragments within the same cell, we cloned the N-terminal fragment into a plasmid expressing the mCherry fluorescent protein and the C-terminal fragment into a plasmid expressing BFP. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on cells coexpressing red and blue fluorescence. Additionally, to facilitate nuclear entry and recombined the rox sequence, we added a nuclear localization signal (NLS) to the N-terminal fragment and assessed the impact of the NLS on the C-terminal fragment (Fig. 2A). Additionally, to enhance the nuclear localization and recombination efficiency of the integrated rox sites, we introduced a nuclear localization signal (NLS) at the N-terminus of the N-terminal fragment and at the C-terminus of the C-terminal fragment of Dre recombinase. Subsequently, we assessed the impact of these modifications on the overall recombination activity (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Recombinase activity of split-Dre pairs in 293T cells stably expressing an inverse EGFP gene flanked by two opposing rox sequences. (A) Schematic representation of the split-Dre constructs and their pairing strategy. Vc1, pLVX-IRES-mCherry; Vc2, pLVX-IRES-BFP; NC, pLVX-IRES-mCherry-Dre; red N, nuclear localization signal (NLS); blue nl, N-terminal Intein; blue lc, C-terminal Intein. (B) Proportion of EGFP-positive cells determined by flow cytometry 6 days post-transfection. Sample 1 was gated on live cells; samples 2, 3, and 4 were gated on mCherry+ cells; other samples were gated on mCherry+ BFP+ cells. (C) Statistical analysis of the cell proportions shown in panel B. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments, with statistical significance indicated as follows: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. (D) Fluorescence microscopy images of selected samples captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope 6 days post-transfection. (E) Statistical analysis of the proportions of EGFP-expressing cells at different time points post-transfection under selected conditions

Six days post-co-transfection of the split Dre expression plasmids into rox site-stable 293T cells, we assessed the proportion of EGFP-expressing cells. Consistent with the initial screen, the N60/61C combination lacked recombinase activity. Interestingly, the N191/192C combination, regardless of the presence of the NLS on 192C, resulted in higher recombinase activity than the intact Dre did (Fig. 2B, C, D). These findings suggest that the N191/192C split combination can effectively mediate recombination at the integrated rox site without the need for additional fusion proteins.

To increase the recombinase activity of the fragment combinations, we employed intein-mediated ligation to connect the split Dre (Fig. 2A). This approach enables the N60/61C combination, which lacks recombinase activity, to exhibit activity that surpasses that of intact Dre. Unexpectedly, the N191/192C combination, which was originally active, lost its activity when it was fused with the intein (Fig. 2B, C, D).

Furthermore, the addition of an NLS to the C-terminus of Dre increased the efficiency of recombination at the integrated rox sites within the genomic DNA, regardless of whether Dre was intact or split (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Figure S4).

To elucidate whether the observed differences in activity among various combinations were attributable to disparities in protein expression levels, we utilized Western Blot (WB) technology to quantify the expression levels of Dre protein across different combinations. Specifically, we were able to detect the expression level of the C-terminal fragment of Dre protein. The results indicated that the expression level of Dre protein in samples transfected with the N191/192C plasmid was significantly lower than that in samples transfected with the full-length Dre plasmid (Supplementary Figure S5). However, in the N191/192C split combination linked with an intein, the expression level of Dre protein was comparable to that in the full-length Dre samples. These findings suggest that the N191/192C split combination itself is capable of effectively mediating recombination at the rox site. Conversely, the incorporation of an intein appears to compromise the recombinase activity.

Split Dre proteins mediate efficient site-specific recombination in mouse cell lines

Considering the cell specificity and potential application of split Dre proteins in transgenic mice, we assessed the recombinase activity of split Dre combinations in the mouse cell line 4T1 via a stable 4T1 cell line containing the rox site (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Recombinase activity of split-Dre pairs in 4T1 cells stably expressing an inverse EGFP gene flanked by two opposing rox sequences. (A) Schematic representation of the pairing strategy for split-Dre. No, 4T1 cells that do not express the EGFP gene; CK, 4T1 cells expressing the inverse EGFP gene; Vc2, pLVX-IRES-BFP; red N, nuclear localization signal (NLS); blue nl, N-terminal Intein; blue lc, C-terminal Intein. (B) Proportion of EGFP-positive cells determined by flow cytometry 6 days post-transfection. Samples 1 and 2 were gated on live cells; sample 3 was gated on mCherry+ cells; other samples were gated on mCherry+ BFP+ cells. (C) Statistical analysis of the cell proportions shown in panel B. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments, with statistical significance indicated as follows: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. (D) Fluorescence microscopy images of selected samples captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope 6 days post-transfection

The results were largely consistent with those in 293T cells, with the N60/61C combination lacking recombinase activity and the intact Dre enabling nearly 100% of cells to undergo rox site recombination. The N191/192C split combination also facilitated nearly 100% recombination at the rox site. The N60/61C combination fused with intein exhibited almost the same recombinase activity (Fig. 3B, C, D). These results indicate that the N191/192C split combination and the N60/61C combination fused with intein can effectively mediate site-specific recombination at the integrated rox sites in mouse cells, with the N191/192C combination showing greater activity.

Split Dre proteins mediate efficient site-specific recombination in prokaryotic E. coli cells

To confirm the recombinase activity of the most effective split Dre combination, N191/192C, in prokaryotic cells, we constructed a pACYC177-roxLacZα(rox) plasmid by inserting the LacZα coding sequence flanked by two oppositely oriented rox sequences at the PstI site in the prokaryotic plasmid pACYC177 (Fig. 4A). In this plasmid, the inserted LacZα coding sequence is in the opposite direction to the promoter and disrupts the ampicillin resistance gene in the original plasmid. The split Dre fragment-encoding sequences were subsequently cloned and inserted into the pUC19 plasmid, which can coexist with pACYC177 in E. coli. A Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) sequence was added to the front of each Dre fragment encoding a sequence to ensure normal expression, and the insertion of each Dre fragment disrupted the expression of the LacZα-encoding gene in the original pUC19 plasmid (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Recombinase activity of split-Dre pairs in Escherichia coli (E. coli). (A) Schematic representation of the plasmid construction strategy for expressing Dre and its derivatives in E. coli. SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence. (B) β-galactosidase activity exhibited by Dre and its derivatives alone on LB agar plates. CK, pLVX-IRES-Puro; Vc3, pUC19; Amp, ampicillin. (C) β-galactosidase activity exhibited by co-transformation of Dre and its derivatives with pACYC177-roxLacZα (rox) into E. coli. Amp, ampicillin; Ka, kanamycin. (D) Statistical results of β-galactosidase activity for the transformants shown in panel C. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from more than three independent experiments, with statistical significance indicated as follows: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001

After co-transfecting the plasmids containing split Dre fragments with the pACYC177-roxLacZα(rox) plasmid into E. coli, β-galactosidase activity assays revealed that the N191/192C split combination exhibited recombinase activity comparable to that of intact Dre, whereas the N60/61C combination lacked activity (Fig. 4C, D). These results demonstrate that the N191/192C split combination can effectively mediate site-specific recombination in prokaryotic cells.

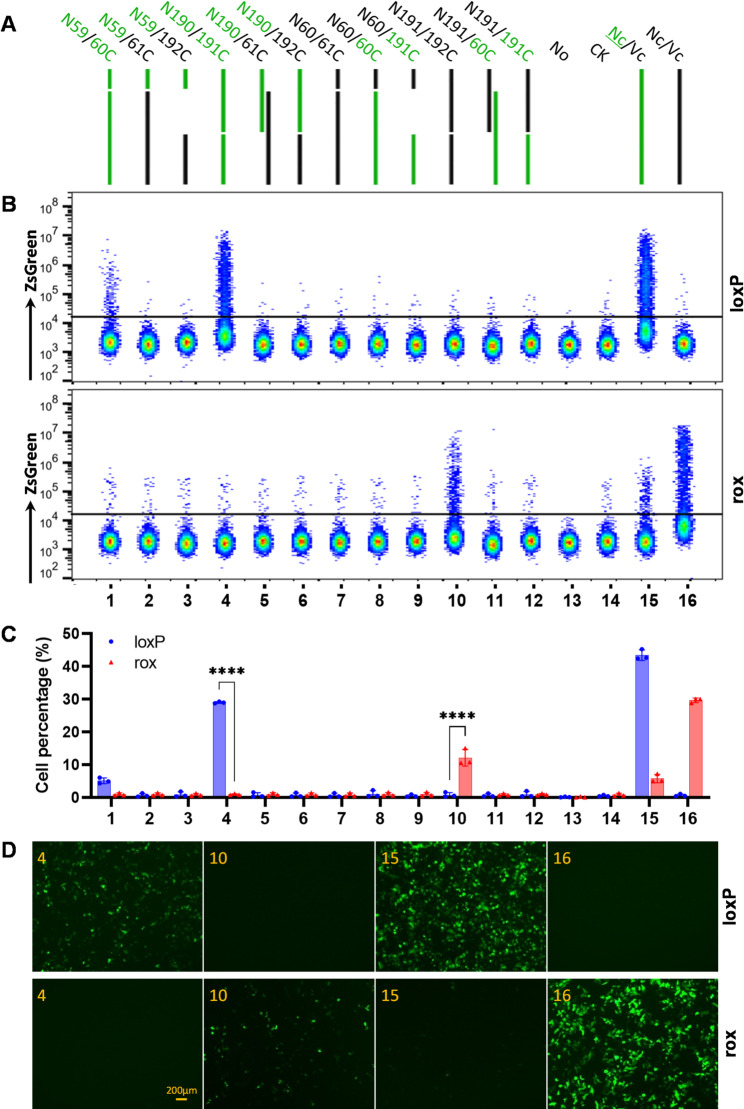

The split forms of Dre and Cre proteins demonstrate a clear absence of functional cross-complementation

Given the relatively high homology between Dre and Cre, we sought to investigate whether the split Dre protein and split Cre protein would exhibit cross-complementation when used concurrently. To this end, we performed pairwise cross-combinations of the split N191/192C and N60/61C combinations of Dre protein with the split Cre protein (Fig. 5A). These combinations were co-transfected with the pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen plasmid containing tandem rox sequences or the pCAG-loxPSTOPloxP-ZsGreen plasmid containing tandem loxP sequences into 293T cells. After 48 h, the proportion of ZsGreen-expressing cells in each sample was measured to assess their ability to cleave the loxP and rox sequences.

Fig. 5.

Recombinase activity conferred by the heterologous combination of split Dre and split Cre proteins. (A) Schematic illustration of the pairing strategy for split Dre and split Cre. No, no vector control; CK, pcDNA™3.1/myc-His A; Nc/Vc, full-length Dre or Cre with pcDNA™3.1/myc-His (A) Cre and its derivatives are indicated in green. In each sample, the pcDNA™3.1/myc-His A vectors containing the Dre or Cre genes and their variants, and the plasmids containing either the rox or lox sites, were co-transfected into 293T cells at a mass ratio of 2:2:1. (B) Proportion of ZsGreen-positive cells among live cells, as determined by flow cytometry 48 h post-transfection. The upper section represents combination groups co-transfected with pCAG-loxPSTOPloxP-ZsGreen into 293T cells, while the lower section represents combination groups co-transfected with pCAG-roxSTOProx-ZsGreen into 293T cells. (C) Statistical results of the proportion of ZsGreen-expressing cells as shown in panel (B) Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments, with statistical significance indicated as follows: ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. (D) Fluorescence microscopy images of selected samples captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope 48 h post-transfection

The results indicated that the split Cre protein combination N190/191C could mediate recombination at the loxP site, while the split Dre protein combination N191/192C could mediate recombination at the rox site. However, when these split Cre and Dre fragments were cross-combined, they failed to mediate recombination at either the loxP or rox site. Other combinations also failed to effectively mediate recombination at either the loxP or rox sites (Fig. 5B, C, D; Figure S6). This suggests that there is no cross-complementary effect between the split Dre protein (N191/192C) and the split Cre protein (N190/191C or N59/60C), allowing them to be used simultaneously in the same cell.

Discussion

In this study, we successfully developed a self-activating split Dre recombinase system, marking a significant advancement in the innovation of genetic manipulation tools. While previous studies have explored split Dre proteins, these studies have focused primarily on fusing Dre with other proteins to achieve recombinase activity under specific conditions [29, 30]. Our study, however, presents a novel split Dre recombinase system that operates without the need for light or chemical induction.

During the screening of split Dre protein combinations for recombinase activity, we referenced the split sites of Cre recombinase [25]. However, we discovered that not all split sites maintained the recombinase activity of Dre. For example, although the Cre enzyme retains high activity when split at positions 59/60 [36] and 244/245 [25], the Dre enzyme does not exhibit significant activity when split at these same positions. This finding highlights the substantial differences between Cre and Dre in terms of their protein fragment complementation sites.

The literature suggests that partial amino acid repeats between Cre protein fragments can increase recombinase activity [37, 38]. In our study, the N191/192C combination demonstrated recombinase activity, but its activity decreased when either N191 or 192C fragments were combined with other fragments containing repetitive amino acid sequences. This reduction in activity may indicate that additional amino acid sequences alter protein folding, thereby affecting the complementation of protein fragments.

An intriguing finding of our study is that the N191/192C combination exhibited lower activity in mediating recombination at episomal rox sites compared to the full-length Dre, but demonstrated higher activity in mediating recombination at the integrated rox sites. This discrepancy was not due to higher expression levels of Dre protein in the N191/192C combination during recombination at integrated rox sites. In fact, the expression level of Dre protein in the N191/192C combination was lower than that of full-length Dre. These results indicate that the N191/192C combination can efficiently exert recombinase activity, which could be further enhanced by increasing the expression level of Dre protein. The higher recombinase activity of the N191/192C combination compared to full-length Dre protein may be attributed to the smaller size of the split Dre fragments, which may facilitate their entry into the nucleus. Additionally, we observed that the recombinase activity of Dre fragments significantly increased when a nuclear localization signal (NLS) was added, underscoring the importance of the NLS in enabling the recombinase to enter the nucleus and function effectively.

To increase the recombinase activity of split Dre proteins, we experimented with using inteins to reconstitute the split Dre protein into a full-length enzyme [39, 40]. The results indicated that the N60/61C combination exhibited recombinase activity when fused with inteins, whereas the N191/192C combination lost its activity upon intein fusion. These findings suggest that the impact of intein fusion on protein conformation varies and that its effect on recombinase activity warrants further investigation.

Moreover, our study revealed no complementary effect between split Dre and split Cre proteins, suggesting the potential for using both split proteins simultaneously within the same cell. By employing up to four gene drivers to express the split Cre and Dre proteins, not only can precise knockout of the same target gene be achieved, but it can also be used to label different cells simultaneously, as well as other related applications. Earlier research has documented bidirectional, off-target recombination between Cre and Dre [41–43]. Consistent with these observations, our experiments revealed a low level of Cre-mediated recombination at rox sites (Fig. 5). However, the split-Cre N190/191C pair and the split-Dre N191/192C pair maintained strict cognate specificity, with each exclusively recombining its own target (loxP or rox) without detectable cross-reactivity. Nevertheless, this apparent fidelity does not preclude the possibility of cross-talk under different conditions. Consequently, downstream applications should either rigorously confirm specificity or employ more selective recombinases, such as VCre.

We validated the activity of the N191/192C split combination in both the 4T1 mouse cell line and prokaryotic cells, demonstrating its efficacy in mediating site-specific recombination across different cell types. However, further research is needed to verify the recombinase activity of split Dre proteins in vivo and explore their broader applications.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that both the Dre N191/192C split combination and the N60/61C split combination fused with the intein can effectively mediate site-specific recombination at the integrated rox sites. The split Cre and Dre proteins can be used simultaneously without interfering with each other, each accurately recognizing its own target sequence. These findings provide new tools for more precise cell labeling or gene expression manipulation and lay the foundation for the development of future gene editing technologies.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that the N191/192C split Dre protein and the intein-fused N60/61C split Dre protein effectively mediate site-specific recombination of the integrated rox sites without light or chemical compounds. These configurations exhibit robust recombinase activity across diverse cellular systems, including mammalian (293T and 4T1) and bacterial (E. coli) models. Notably, the absence of detectable cross-complementation between the split Dre and Cre proteins under the tested conditions indicates that they can coexist within the same cell without mutual interference. These novel tools provide enhanced precision for cell labeling and gene expression manipulation, thereby paving the way for future innovations in gene editing technology.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful for the invaluable feedback and contributions provided by our colleagues within the laboratory. Their insights have significantly enhanced the quality of our research. The technology described in this study has been filed for China patent application (Application No. 202310041209.1, Patent pending).

Author contributions

CX, SGZ and GQ conceived and designed the experiment. CX, JG, YZ, WY, RL, DY and YL performed the experiments. JG, YZ, WY, RL and DY performed statistical analyses. CX, JG and GQ drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Guangxi Science and Technology Program (NO. GuiKeAD23026143) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82360327 and 31900659).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The publication has been approved by all coauthors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chichu Xie and Jinfeng Gan contributed equally to this article.

Contributor Information

Chichu Xie, Email: xcc335@glmu.edu.cn.

Song Guo Zheng, Email: Zheng@osumc.edu.

Guangying Qi, Email: qgy@glmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Tian X, Zhou B. Strategies for site-specific recombination with high efficiency and precise Spatiotemporal resolution. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sternberg N, Hamilton D. Bacteriophage P1 site-specific recombination. I. Recombination between LoxP sites. J Mol Biol. 1981;150(4):467–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimura Y, Ida-Tanaka M, Hiramaki T, Goto M, Kamisako T, Eto T, et al. Novel reporter and deleter mouse strains generated using vcre/vloxp and scre/sloxp systems, and their system specificity in mice. Transgenic Res. 2018;27(2):193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki E, Nakayama M. VCre/VloxP and scre/sloxp: new site-specific recombination systems for genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(8):e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews BJ, Proteau GA, Beatty LG, Sadowski PD. The FLP recombinase of the 2 micron circle DNA of yeast: interaction with its target sequences. Cell. 1985;40(4):795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhstoss S, Rao RN. Analysis of the integration function of the streptomycete bacteriophage phi C31. J Mol Biol. 1991;222(4):897–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anastassiadis K, Fu J, Patsch C, Hu S, Weidlich S, Duerschke K, et al. Dre recombinase, like cre, is a highly efficient site-specific recombinase in E. coli, mammalian cells and mice. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(9–10):508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karimova M, Splith V, Karpinski J, Pisabarro MT, Buchholz F. Discovery of nigri/nox and panto/pox site-specific recombinase systems facilitates advanced genome engineering. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karimova M, Abi-Ghanem J, Berger N, Surendranath V, Pisabarro MT, Buchholz F. Vika/vox, a novel efficient and specific Cre/loxP-like site-specific recombination system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(2):e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jelicic M, Schmitt LT, Paszkowski-Rogacz M, Walder A, Schubert N, Hoersten J, et al. Discovery and characterization of novel Cre-type tyrosine site-specific recombinases for advanced genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(10):5285–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu H, Cavendish JZ, Agmon A. Not all that glitters is gold: off-target recombination in the somatostatin-IRES-Cre mouse line labels a subset of fast-spiking interneurons. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liput DJ. Cre-Recombinase dependent germline deletion of a conditional allele in the Rgs9cre mouse line. Front Neural Circuits. 2018;12:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Wang O, Bi Y, Wang Y, Crawford H, Ji B. Ptf1a Promoter-Driven Cre expression during spermatogenesis causes germline recombination. Pancreas. 2022;51(1):90–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheldon C, Kessinger CW, Sun Y, Kontaridis MI, Ma Q, Hammoud SS, et al. Myh6 promoter-driven Cre recombinase excises floxed DNA fragments in a subset of male germline cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2023;175:62–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner-Eddy PD, Fischer LA, Costalonga M. Cre-loxP reporter mouse reveals stochastic activity of the Foxp3 promoter. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie C, Zhu F, Wang J, Zhang W, Bellanti JA, Li B et al. Off-Target deletion of conditional Dbc1 allele in the Foxp3(YFP-Cre) mouse line under specific setting. Cells. 2019;8(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Coppoolse ER, de Vroomen MJ, Roelofs D, Smit J, van Gennip F, Hersmus BJ, et al. Cre recombinase expression can result in phenotypic aberrations in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;51(2):263–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, Duan Q, Cui Y, Jones OD, Shao D, Zhang J et al. Cardiac-Specific expression of Cre recombinase leads to Age-Related cardiac dysfunction associated with Tumor-like growth of atrial cardiomyocyte and ventricular fibrosis and ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wu D, Huang Q, Orban PC, Levings MK. Ectopic germline recombination activity of the widely used Foxp3-YFP-Cre mouse: a case report. Immunology. 2020;159(2):231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian X, He L, Liu K, Pu W, Zhao H, Li Y, et al. Generation of a self-cleaved inducible Cre recombinase for efficient Temporal genetic manipulation. EMBO J. 2020;39(4):e102675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermann M, Stillhard P, Wildner H, Seruggia D, Kapp V, Sánchez-Iranzo H, et al. Binary recombinase systems for high-resolution conditional mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(6):3894–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He L, Li Y, Li Y, Pu W, Huang X, Tian X, et al. Enhancing the precision of genetic lineage tracing using dual recombinases. Nat Med. 2017;23(12):1488–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, He L, Li Y, Pu W, Zhang S, Han X, et al. Dual Cre and dre recombinases mediate synchronized lineage tracing and cell subset ablation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(6):101965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kouvaros S, Bizup B, Solis O, Kumar M, Ventriglia E, Curry FP, et al. A CRE/DRE dual recombinase Transgenic mouse reveals synaptic zinc-mediated thalamocortical neuromodulation. Sci Adv. 2023;9(23):eadf3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajaee M, Ow DW. A new location to split Cre recombinase for protein fragment complementation. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(11):1420–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin Q, Li R, Ow DW. Split-Cre mediated deletion of DNA no longer needed after site-specific integration in rice. Theor Appl Genet. 2022;135(7):2333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JS, Kolesnikov M, Peled-Hajaj S, Scheyltjens I, Xia Y, Trzebanski S, et al. A binary Cre Transgenic approach dissects microglia and CNS Border-Associated macrophages. Immunity. 2021;54(1):176–e190177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong Y, Yang C, Pan F. Post-Translational regulations of Foxp3 in Treg cells and their therapeutic applications. Front Immunol. 2021;12:626172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao S, Yuan P, Ouellette B, Zhou T, Mortrud M, Balaram P, et al. RecV recombinase system for in vivo targeted optogenomic modifications of single cells or cell populations. Nat Methods. 2020;17(4):422–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Zhang Q, Gu Y, Wu Y, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. Efficient photoactivatable dre recombinase for cell type-specific Spatiotemporal control of genome engineering in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(52):33426–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng WX, Zhu SL, Zhang BY, Shi YM, Feng XX, Liu F, et al. Smoothened regulates migration of Fibroblast-Like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis via activation of Rho GTPase signaling. Front Immunol. 2017;8:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varadi M, Bertoni D, Magana P, Paramval U, Pidruchna I, Radhakrishnan M, et al. AlphaFold protein structure database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(D1):D368–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Xu G, Liu B, Gu G. Cre reconstitution allows for DNA recombination selectively in dual-marker-expressing cells in Transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(19):e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han X, Han F, Ren X, Si J, Li C, Song H. Ssp DnaE split-intein mediated split-Cre reconstitution in tobacco. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult (PCTOC). 2013;113(3):529–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ge J, Wang L, Yang C, Ran L, Wen M, Fu X, et al. Intein-mediated Cre protein assembly for transgene excision in hybrid progeny of Transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35(10):2045–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang P, Chen T, Sakurai K, Han BX, He Z, Feng G, et al. Intersectional Cre driver lines generated using split-intein mediated split-Cre reconstitution. Sci Rep. 2012;2:497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seidi A, Mie M, Kobatake E. Novel recombination system using Cre recombinase alpha complementation. Biotechnol Lett. 2007;29(9):1315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casanova E, Lemberger T, Fehsenfeld S, Mantamadiotis T, Schütz G. Alpha complementation in the Cre recombinase enzyme. Genesis (New York NY: 2000). 2003;37(1):25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu H, Hu Z, Liu XQ. Protein trans-splicing by a split intein encoded in a split DnaE gene of synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(16):9226–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khoo ATT, Kim PJ, Kim HM, Je HS. Neural circuit analysis using a novel intersectional split intein-mediated split-Cre recombinase system. Mol Brain. 2020;13(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fenno LE, Ramakrishnan C, Kim YS, Evans KE, Lo M, Vesuna S, et al. Comprehensive Dual- and Triple-Feature intersectional Single-Vector delivery of diverse functional payloads to cells of behaving mammals. Neuron. 2020;107(5):836–e853811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madisen L, Garner AR, Shimaoka D, Chuong AS, Klapoetke NC, Li L, et al. Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron. 2015;85(5):942–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenno LE, Mattis J, Ramakrishnan C, Hyun M, Lee SY, He M, et al. Targeting cells with single vectors using multiple-feature boolean logic. Nat Methods. 2014;11(7):763–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.