Abstract

Background

This study assessed job satisfaction and dissatisfaction among Pennsylvania dental hygienists using the validated Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) to identify key workplace factors associated with job satisfaction, dissatisfaction, and workforce instability.

Methods

A cross-sectional quantitative survey was distributed in 2024 to licensed dental hygienists in Pennsylvania using convenience sampling at two professional events. Participants completed the JSS, a 36-item instrument covering nine workplace domains, via an anonymous Qualtrics survey. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize overall satisfaction levels, and chi-squared tests to assess relationships between JSS responses and demographic variables such as years of experience and work setting.

Results

Of 342 responses, 328 met the inclusion criteria. Respondents were predominantly female (98.5%) and aged 55 and older (52.7%) and worked primarily in private dental practices (71.6%). Although the respondents reported high satisfaction with intrinsic motivators, such as pride in work (mean score = 5.31) and relationships with coworkers (mean = 5.06), they reported significant dissatisfaction with income (60.4% disagreed that they were fairly paid), promotional opportunities (87.1% agreed there was little chance for promotion), and organizational support. Frequency of raises and perceived inequity in benefits varied significantly among work settings, as did supervisory support and workplace conflict.

Conclusion

Despite high professional pride and collegiality, dissatisfaction with income, limited advancement, and administrative barriers may contribute to instability in the broader workforce. Addressing systemic dissatisfaction while reinforcing drivers of satisfaction may help sustain a resilient dental hygiene workforce and support access to care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-13269-5.

Keywords: Dental hygienist, Healthcare workforce shortage, Pennsylvania, Job satisfaction, Job dissatisfaction

The United States is facing a critical shortage of dental healthcare workers, with workforce reductions having yet to recover following the covid-19 pandemic [1]. Pennsylvania in particular is experiencing an ongoing registered dental hygienist (RDH) workforce crisis [2]. Oral health is essential to overall health, and the shortage of RDHs limits access to oral care services. This shortage has had a domino effect of negative consequences, affecting not only patients and communities but dental facilities and the broader healthcare system [3]. The decline in dental healthcare workers combined with Pennsylvania’s specific challenges, including low wages relative to national averages, licensure and regulatory barriers, and workforce mobility limitations, is contributing to an ongoing RDH shortage, workplace difficulties, and ultimately, reduced access to oral health services [4].

Understanding satisfaction and dissatisfaction trends among Pennsylvania’s RDHs is essential for supporting workforce sustainability. National workforce shortages are intensified when systemic dissatisfaction reduces clinical hours or prompts career exits, leading to reduced access to preventive care, increased strain on the remaining providers, and higher operational costs. Despite rising wages and job availability, many RDHs remain dissatisfied, heightening the future instability of the workforce [5, 6]. This dissatisfaction stems from personal, professional, and workplace factors [7–9].

Although national studies have provided broad insights into RDH satisfaction, few have explored state-specific dynamics using validated, multidimensional tools [9–12]. Identifying drivers of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, such as supervision, communication, rewards, and working conditions, is necessary for designing interventions that promote workforce engagement [13]. Structured tools like the Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) offer a framework for such analyses [14].

Introduction

Pennsylvania’s regulatory and economic environment presents unique challenges, including lower-than-average pay, extra licensure requirements for local anesthesia, and limited expanded-function autonomy in comparison with other states [2, 15–18]. As of May 2023, Pennsylvania employed 7,750 dental hygienists with a median hourly wage of $37.02 and annual median wage of $77,010, as compared to the national median hourly wage of $43.21 and annual median wage of $89,890, based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data [15]. In a 2022 workforce study, the Pennsylvania Coalition for Oral Health [19] reported that Pennsylvania ranks 44 of 53 in annual salaries for dental hygienists.

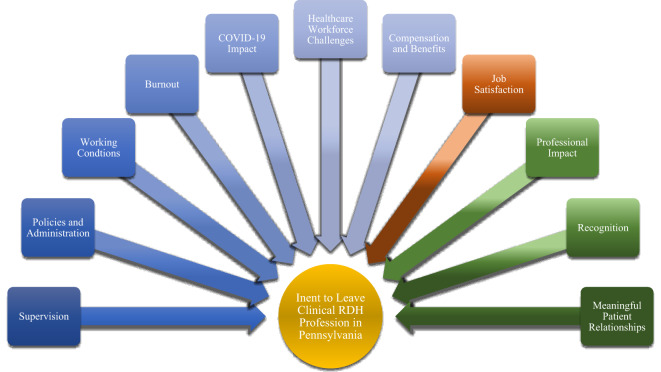

A conceptual model was developed, based on the literature review and common themes in job satisfaction research, particularly as informed by Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory. The model illustrates how facets of satisfaction and dissatisfaction interact with systemic, organizational, and personal variables (Fig. 1). The color groupings represent variable types: red for the independent variable (job satisfaction), yellow for the dependent variable (intent to leave), green for moderating factors like professional impact, and blue for mediating factors such as supervision, compensation (pay and benefits), and burnout. The aim was to analyze these patterns to generate useful insights for employers, policymakers, and professional organizations. In this sample, strengthening workplace satisfaction while addressing areas of dissatisfaction may support a more resilient, engaged dental hygiene workforce in Pennsylvania.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Model of Factors in Intent to Leave the Clinical RDH Profession in Pennsylvania. Conceptual model illustrating hypothesized relationships between job satisfaction (independent variable), intent to leave clinical dental hygiene practice in Pennsylvania (dependent variable), including potential moderating and mediating variables. Independent variable (IV; red): job satisfaction. Dependent variable (DV; yellow): intent to leave the clinical RDH profession in Pennsylvania. Moderating variables (green): professional impact, recognition, meaningful patient relationships. Mediating variables (blue): supervision, policies, and administration, working conditions, burnout, impact of COVID-19, healthcare workforce challenges, pay, and benefits

Purpose. This study assesses the current state of job satisfaction among RDHs in Pennsylvania using the JSS framework and identifies key workplace factors in systemic dissatisfaction and workforce strain.

Methods

Research design and ethics approval

This study employed the validated Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) developed by Spector [14] to measure job satisfaction and dissatisfaction across nine workplace domains [20]. The JSS offers a multidimensional framework for analyzing how work environment factors contribute to satisfaction among dental hygienists and identifying specific drivers of engagement and workforce stability.

This descriptive, cross-sectional, quantitative survey study assesses job satisfaction and dissatisfaction among licensed clinical dental hygienists practicing in Pennsylvania. The study protocol received exemption from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine Institutional Review Board (Protocol #32 − 016), waiving the need for a consent to participate, however participants were provided with a document outlining the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and confidentiality measures, and they indicated their understanding in order to gain access to the survey. Survey responses were collected anonymously via Qualtrics, including answers to demographic questions on licensure status, age, gender, marital status, race, education, zip code, experience, and practice setting (Appendix A).

Survey instrument

Data were collected using the validated 36-item Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) developed by Spector [14], which measures attitudes across nine facets of job satisfaction: pay, promotion, supervision, fringe benefits, contingent rewards, operating procedures, relationships with coworkers, nature of work, and communication [20]. Responses were given on a six-point Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (6). The JSS is a validated instrument that correlates with established measures like the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire and the Job Descriptive Index.

Recruitment and sampling

Participants were recruited at the 2024 Pennsylvania Dental Hygienists’ Association (PDHA) Annual Session and the 2024 Greater Delaware Valley Dental Health Conference. A total of 378 attendees were present at the PDHA Annual Session and 286 attended the Greater Delaware Valley Dental Health Conference, resulting in a combined survey response rate of 51.5%. Eligibility required licensure in Pennsylvania and current or recent (within three years) clinical practice. Dental hygiene students and individuals unlicensed in Pennsylvania or retired for more than three years were excluded.

Although the professional conference recruitment captured a broad demographic, reliance on association attendees introduced a potential self-selection bias. Additional recruitment through stakeholder organizations was used to broaden the diversity of participants.

Data collection procedures

Conference attendees were provided with a survey link and access instructions during the event. The survey remained open for responses for four weeks following the conferences. The survey was administered through Qualtrics, a secure, encrypted web platform that ensures participants’ confidentiality and prevents the collection of identifiable information. The survey remained open for four weeks and no incentives were offered. Qualtrics features such as mobile accessibility, multilingual support, and automated data validation were used to enhance data quality.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and JSS domain scores. Chi-squared tests were used to examine the associations between satisfaction scores and demographic variables such as years of experience and practice setting. Analyses were conducted within Qualtrics, using its statistics and data-visualization capabilities to ensure reliability and minimize data-entry errors.

Results

The survey received 342 responses, and 328 participants met eligibility criteria based on licensure status and recent clinical activity. Of these, 94.8% (n = 311) were currently licensed and 5.2% (n = 17) had retired or placed their licenses on inactive status within the past three years. The inclusion of recently retired RDHs captured perspectives shaped by post-covid-19 workforce attrition trends. The majority of respondents (79.0%, n = 259) were actively providing clinical care at the time of the survey.

Respondents represented a broad range of ages, were predominantly female: 98.5% (n = 323), married 73.8% (n = 242) and White or Caucasian: 95.8% (n = 319). Most respondents (58.5%; n = 192) held an associate’s degree, though bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees were represented. In terms of employment, 53.9% (n = 174) worked full-time, 30.2% (n = 99) worked part-time, and the majority of respondents identified their primary work settings as private dental practice: 71.6% (n = 235). The sample reflected a diverse range of experiences, with nearly half of respondents (45.1%; n = 148) reporting more than 30 years of experience in the field, followed by 20–30 years (26.2%; n = 86).

The demographic information collected from survey participants is comprehensively presented in Table 1, providing a detailed overview of the sample characteristics that are essential for contextualizing the study’s findings. The bolded values in each category indicate the most frequently selected response option.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Variable | Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| License Status | Currently licensed | 311 | 94.80% |

| Inactive or retired (last 3 years) | 17 | 5.20% | |

| Clinical Setting | Yes | 259 | 79.00% |

| No | 69 | 21.00% | |

| Age Group | Under 25 | 5 | 1.50% |

| 25–34 | 25 | 7.60% | |

| 35–44 | 55 | 16.80% | |

| 45–54 | 69 | 21.00% | |

| 55–64 | 87 | 26.50% | |

| 65 and over | 86 | 26.20% | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Gender | Male | 2 | 0.60% |

| Female | 323 | 98.50% | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 0.90% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 242 | 73.80% |

| Living with a partner | 16 | 4.90% | |

| Widowed | 16 | 4.90% | |

| Divorced or separated | 27 | 8.20% | |

| Never been married | 25 | 7.60% | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 0.60% | |

| Race | White or Caucasian | 319 | 95.80% |

| Multiple Answers Allowed | Black or African American | 4 | 1.20% |

| American Indian, Native American, or Alaska Native | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Asian | 2 | 0.60% | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Other | 4 | 1.20% | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 0.90% | |

| Education Level | Associate’s degree | 192 | 58.50% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 90 | 27.40% | |

| Master’s degree | 39 | 11.90% | |

| Doctorate | 6 | 1.80% | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.30% | |

| Experience | Less than 1 year | 1 | 0.30% |

| 1–3 years | 11 | 3.40% | |

| 4–6 years | 14 | 4.30% | |

| 7–10 years | 8 | 2.40% | |

| 10–20 years | 58 | 17.70% | |

| 20–30 years | 86 | 26.20% | |

| More than 30 years | 148 | 45.10% | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 0.60% | |

| Employment Status | Full-time | 174 | 53.90% |

| Part-time | 99 | 30.20% | |

| Temporary/contract | 19 | 5.80% | |

| Unemployed | 5 | 1.50% | |

| Retired | 29 | 8.80% | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 0.60% | |

| Primary Work Setting | Private Dental Practice | 235 | 71.60% |

| Public health facility | 6 | 1.80% | |

| Educational institution | 17 | 5.20% | |

| Dental support organization | 22 | 6.70% | |

| Other | 31 | 9.50% | |

| Government setting | 4 | 1.20% | |

| Federally qualified health center | 11 | 3.20% | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 3.40% |

Job satisfaction survey (JSS) findings

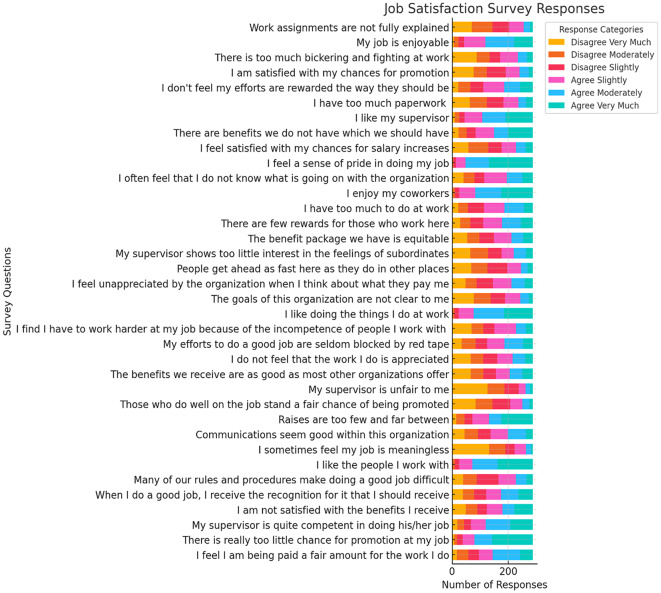

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the distribution of responses provides insight into key satisfaction and dissatisfaction trends across various workplace factors. Job satisfaction survey results are comprehensively detailed in Appendix B, which provides a complete breakdown of participants’ responses.

Fig. 2.

Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) Response Distribution

Discussion

The distribution signifies an experienced workforce, with a substantial portion (52.7%) age 55 or older, indicating a risk of retirement-driven attrition for the profession. The lack of racial diversity reflects national workforce trends and may indicate limited representation within the dental hygiene profession. The data suggest that personal life stability, particularly in marriage, is a relevant factor in career satisfaction and retention. This high percentage of veteran professionals suggests that retirement-related workforce gaps could further intensify the dental hygiene shortage in Pennsylvania. The findings show that the large majority of RDHs work in private practices, but alternative employment settings are emerging, particularly within corporate and educational roles. Traditional career ladders are limited in private practices. While some practices may offer lead hygienist or managerial roles, and some hygienists become practice owners in partnerships with dentists, formal advancement pathways are uncommon.

Consistently with national trends [9], pay and benefits emerged as a major source of dissatisfaction, with more than 66% of respondents agreeing that raises were too infrequent. Career advancement was also a significant concern, reflected by a high mean score (5.01) for “There is really too little chance for promotion,” corroborating reports of stagnant growth in the field [6]. Limitations on promotional opportunities continue to undermine long-term engagement. Organizational policies, communication gaps, and bureaucratic barriers were frequent sources of dissatisfaction among survey respondents, and are consistent with broader professional patterns [12]. Respondents frequently expressed frustration with internal rules impeding effective work. These findings suggest that among respondents, salary is a concern, however, improved wages alone may not reduce turnover unless coupled with opportunities for career growth.

Conversely, coworker relationships were a key satisfaction factor. High scores for statements like “I like the people I work with” align with previous research showing collegiality buffers against dissatisfaction [21]. Supervisory support was also generally perceived positive, though varying by setting, consistently with findings by Al Zamel et al. [22], highlighting the impact of leadership on job satisfaction. Strengthening communication with supervisors could further enhance morale.

These results align with Herzberg’s two-factor theory [23], suggesting that while intrinsic motivators like pride in work are strong among surveyed RDHs, dissatisfaction with external factors such as pay, benefits, promotion, and policies remains a concern. This pattern of high intrinsic satisfaction coupled with low extrinsic satisfaction is characteristic of Herzberg’s framework. It typically predicts high job commitment, as employees derive fulfillment from the nature of their work, yet it also results in frequent dissatisfaction due to unmet expectations regarding external rewards. Addressing both dimensions may be critical to improving RDHs’ workforce satisfaction. However, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to determine causal relationships, and the findings should be interpreted within the context of the survey sample.

Pay and benefits. Survey results indicated significant dissatisfaction with pay among Pennsylvania RDHs, with 60.4% (n = 198) disagreeing that they were fairly paid. This aligns with Herzberg’s two-factor theory of motivation [23], in which classifies salary as an external, or “hygiene” factor that prevents dissatisfaction but does not inherently increase job fulfillment. While pay remains a concern, the findings suggest that improved wages alone may not reduce turnover unless coupled with meaningful career growth opportunities.

The mean score for the item “I feel I am being paid a fair amount for the work I do” was 4.06, with 39.6% (n = 130) agreeing slightly, moderately, or very much that they were fairly compensated. Perceptions of pay fairness vary among work settings, highlighting differences in pay and benefit satisfaction between private dental practices, public health facilities, DSOs, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), educational institutions, and government settings. By comparison, DentalPost’s reported in its annual salary survey that 29% of RDHs nationwide expressed dissatisfaction with their pay, indicating that Pennsylvania hygienists experienced greater dissatisfaction than the national average [24].

When asked about raises, participants showed higher dissatisfaction. The item “Raises are too few and far between” received a mean score of 4.47. A majority, 66.8% (n = 219) agreed that opportunities for raises were inadequate, highlighting this as a significant concern across various work settings.

Among respondents in this sample, a statistically significant but weak relationship was observed between the perception that “The benefits we receive are as good as most other organizations offer” and the primary work setting of the respondent (p =.0118, Cramér’s V = 0.187), indicating a moderate statistical significance with practical implications for organizational policy. These findings indicate notable differences in how benefits are perceived in various work environments. Respondents in FQHCs and educational institutions exhibited the highest levels of agreement, with 45.5% and 40.0%, respectively, strongly agreeing that the benefits they received were comparable to those offered by other organizations. This suggests that these settings are regarded as offering competitive or comprehensive benefits, likely due to the structured benefits packages commonly associated with government-supported and academic institutions.

Respondents from private dental practices reported higher dissatisfaction with benefits, with 27.1% strongly disagreeing and 15.9% moderately disagreeing that their benefits matched those of other organizations. This suggests that benefits in private settings are often viewed as inadequate in comparison to those of larger organizations or public institutions. DSO respondents displayed polarized views: 22.7% strongly disagreed, but 27.3% moderately agreed, suggesting variability in corporate benefits, likely due to organizational policies or geographic disparities. By contrast, government-employed RDHs reported the highest satisfaction, with 50.0% strongly agreeing that their benefits were competitive.

FQHCs and educational institutions also showed strong satisfaction, with 36.4% and 40.0% respectively strongly agreeing that their benefits were equitable. Private practices and DSOs, however, exhibited divided perceptions, reflecting inconsistency in benefits across corporate and private settings. Government respondents, though fewer, consistently reported higher satisfaction, likely due to standardized benefits structures. The “other” employment category showed mixed views, with notable disagreement and moderate agreement. A chi-squared test confirmed a statistically significant relationship between perceived benefits equity and primary work setting (p =.0118, Cramér’s V = 0.187).

Regarding raise frequency, DSOs expressed the highest dissatisfaction, with 63.6% strongly agreeing that their raises were too infrequent. Public health facilities also showed concern, with 66.6% of respondents agreeing either slightly or strongly. Private practices revealed mixed views: 39.6% strongly agreed, 16.9% moderately agreed, and 21.7% slightly agreed about raises being insufficient. FQHCs reflected moderate dissatisfaction, while educational and government settings displayed polarized perspectives. The “other” category also indicated diverse opinions regarding raise frequency.

Promotional opportunities. Promotional opportunities constituted a major area of dissatisfaction among respondents. The item “There is really too little chance for promotion on my job” received a mean score of 5.01, the highest among all items. A substantial 87.1% of respondents (n = 286) agreed slightly, moderately, or very much that promotional opportunities were too limited, while only 12.8% (n = 42) expressed disagreement. This reflects a widespread perception of poor advancement opportunities in the profession.

The analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship between the perception that “There is really too little chance for promotion on my job” and the primary work settings of dental hygienists, with a p-value of 0.0042 (very clearly significant) and a medium effect size of 0.195 (Cramér’s V). This indicates that perceptions of promotional opportunities vary meaningfully among work environments.

Respondents in FQHCs and DSOs expressed the highest levels of agreement with the above statement. In FQHCs, 72.7% of respondents agreed “very much,” and in DSOs, 54.5% agreed “very much.” These results highlight widespread dissatisfaction with promotional opportunities in these organizational settings, potentially due to more rigid structures or limited career advancement pathways.

Participants from private dental practices also showed strong agreement with the statement, with 52.7% agreeing “very much” and 22.2% agreeing “moderately,” indicating that lack of advancement is a significant concern in smaller practices. Similarly, respondents from public health facilities demonstrated substantial agreement, with 50.0% agreeing “very much” and 33.3% “moderately,” reflecting perceived limitations to growth opportunities in this setting.

In educational institutions, 40.0% of respondents agreed “very much,” but the responses were more evenly distributed across other levels of agreement and disagreement. This suggests a mix of experiences, potentially depending on the institution’s structure or the roles occupied by respondents. Those from government settings, on the other hand, exhibited greater variability, with 50.0% agreeing “moderately” but only 25.0% agreeing “very much,” reflecting a slightly more optimistic view of promotional opportunities than in other settings.

Supervision. Most participants reported positive perceptions of their supervisors’ competence. “My supervisor is quite competent in doing his/her job,” received a mean score of 4.42, with 76.8% (n = 252) agreeing and 23.2% (n = 76) disagreeing, suggesting room for improvement in supervisory relationships. “My supervisor shows too little interest in the feelings of subordinates” had a lower mean score of 3.04, suggesting some dissatisfaction with interpersonal aspects of supervision, though it was less pronounced than in areas like pay, benefits, or promotion.

Coworker relationships. The statement “I like the people I work with” received one of the highest mean scores (5.06), with 90.9% (n = 298) of respondents agreeing to some extent. This reflects strong positive coworker relationships among RDHs, a factor that can mitigate dissatisfaction in other workplace areas.

Private dental practices and FQHCs reported similarly high levels of camaraderie, with more than 40% of respondents in each setting agreeing “very much” that they liked their coworkers. Public health facilities and DSOs showed the highest levels of strong agreement (50.0%), although a small minority in DSOs did report disagreement, indicating some variability. In educational institutions, 40.0% agreed “moderately” and 33.3% “very much,” showing generally positive coworker relationships. Government settings showed more mixed experiences, with 50.0% agreeing “moderately” but 25.0% disagreeing slightly or strongly.

A chi-squared test revealed a statistically significant relationship between perceptions of workplace conflict (“There is too much bickering and fighting at work”) and primary work setting (p =.0193, Cramér’s V = 0.183). Respondents from private practices and FQHCs reported lower perceptions of conflict, with high rates of disagreement that bickering was a problem. By contrast, DSOs and government settings reported higher agreement that interpersonal conflict was present. Public health facilities and educational institutions showed more polarized distributions, with both agreement and disagreement about workplace conflict being common.

Organizational environment. Perceptions of the organizational environment were divided. For “Communications seem good within this organization,” the mean score was 3.45, with 46.3% (n = 152) agreeing and 53.7% (n = 176) disagreeing. Similarly, “Many of our rules and procedures make doing a good job difficult” received a mean score of 3.28, with 53.7% (n = 176) agreeing that bureaucratic barriers interfered with their work.

The analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship between the perception that “There are benefits we do not have which we should have” and the primary work setting of dental hygienists, with a p-value of 0.0089 (very clearly significant) and a medium effect size of 0.189 (Cramér’s V). Respondents in dental support organizations were most likely to “agree very much” with this statement (45.5%), suggesting that professionals in these settings perceived a strong need for additional benefits. Conversely, respondents in government settings showed mixed responses, with a significant proportion (75%) agreeing “slightly” with the statement, which may reflect less urgent dissatisfaction with benefits than in other groups. Those in FQHCs had higher rates of disagreement, with 27.3% saying they “disagree very much” with that statement, indicating that employees in those settings already had more comprehensive benefits packages or perceived fewer gaps in the available benefits.

Educational institutions displayed polarized trends, with notable proportions of respondents both agreeing “very much” (20%) and disagreeing “very much” (26.7%), reflecting a diversity of perspectives on the benefits in academic environments. Similarly, participants in private dental practices showed a balanced distribution across all levels of agreement, with 32.9% agreeing “very much” but a significant proportion also disagreeing to varying extents. Finally, the “other” category showed some dissatisfaction, with 22.7% agreeing “moderately” and 18.2% agreeing “very much,” suggesting a wide variety of experiences and perceptions among respondents in unconventional or unspecified work settings.

A statistically significant relationship exists between the perception that “My supervisor is quite competent in doing his/her job” and the primary work settings of dental hygienists, with a p-value of 0.0127 (very clearly significant) and a medium effect size of 0.186 (Cramér’s V). These findings suggest that perceptions of supervisory competence vary significantly among work settings. In private dental practices, the majority of respondents expressed positive perceptions of their supervisors, with 34.3% agreeing “moderately” and 30.9% agreeing “very much.” This indicates that supervisors in these settings are generally regarded as competent, probably due to closer and more consistent professional relationships in smaller, practice-based environments. Respondents in DSO settings also showed relatively high agreement, with 27.3% agreeing “slightly” and 22.7% “very much,” although this group also displayed notable disagreement, reflecting mixed perceptions in these organizational structures.

By contrast, respondents from federally qualified health centers and public health facilities displayed more polarized distributions. In FQHCs, 27.3% disagreed “moderately,” reflecting dissatisfaction with supervisory competence, while another 27.3% agreed “moderately,” showing a split in perceptions. Respondents from public health facilities showed similar divergence, with 33.3% disagreeing “slightly” and equal proportions agreeing “moderately” or “very much.” These trends suggest variability in supervisor quality in publicly funded or governmental health organizations.

In educational institutions, the responses skewed positively, with 26.7% agreeing “very much” with the above statement and no respondents expressing strong disagreement. This reflects a generally favorable perception of supervisor competence in academic environments, where leaders may prioritize mentorship and professional development. In government settings, on the other hand, 75% agreed “moderately,” suggesting a strong consensus that supervisors are moderately competent, though sample size limitations in this group should be considered.

Recognition and appreciation. Participants reported moderate dissatisfaction regarding recognition and appreciation. For “When I do a good job, I receive the recognition for it that I should receive,” the mean score was 3.75, with 52.7% (173) agreeing and 47.3% (n = 155) disagreeing. Similarly, “I do not feel that the work I do is appreciated” had a lower mean score of 3.17, with 47.6% (n = 156) agreeing and 52.4% (n = 172) disagreeing.

Job enjoyment and pride. Despite concerns about pay, benefits, and promotion, respondents reported high levels of enjoyment and pride in their work. The statement “I like doing the things I do at work” received a mean score of 4.98, with 89.6% (n = 294) expressing agreement. The highest mean score across all items was for “I feel a sense of pride in doing my job,” which scored 5.31, with 94.2% (n = 309) indicating agreement.

The findings contribute to the body of knowledge on dental hygiene by providing a state-specific, validated analysis of job satisfaction using the JSS instrument. This study adds depth to discussions of workforce problems in dental hygiene by linking dissatisfaction with modifiable organizational and regulatory factors. This research also lays a foundation for longitudinal studies to track the evolving nature of satisfaction among RDHs and examine how systemic reforms influence professional engagement over time.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be considered in the interpretation of these findings. Although the JSS is a validated instrument, it was originally developed for general human service settings and may not fully capture dental hygiene-specific satisfaction factors. Recruitment bias may exist, as the participants were drawn primarily from professional conferences, potentially excluding RDHs who are not engaged in professional networks. This could have skewed the results toward more connected individuals, underrepresenting rural or underserved populations. The use of self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias, including social desirability and recall bias. Additionally, the high proportion of respondents aged 55 and older may skew results toward the perspectives of late-career RDHs. Sampling imbalances may also have affected the findings. Private practice and DSO settings may be overrepresented, and RDHs in rural, public health, education, and government roles may be underrepresented, limiting any insights into the full workforce. Future studies should incorporate randomized or stratified sampling to ensure broader representation.

The focus on Pennsylvania further limits generalizability, as the findings reflect the state’s unique regulatory environment, including its exclusion from the interstate licensure compact. The results may not directly apply to RDHs in states with different policies. In addition, only participants’ primary jobs were examined, which means any influence of secondary employment was overlooked. As a cross-sectional study, this research is limited to capturing a single time point and cannot establish causality. Longitudinal research could capture evolving satisfaction trends. This study did not employ multivariate statistical techniques such as regression modeling to assess the relative influence of intrinsic versus extrinsic factors on turnover intent. Future research should address this to capture the complexity of these relationships. Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights into the factors influencing RDHs’ job satisfaction in Pennsylvania and highlights areas in which future research can improve understanding and support of the workforce.

Conclusion

This study provides state-specific insights into the factors associated with job satisfaction and dissatisfaction among dental hygienists in Pennsylvania. Results from the JSS suggest that while intrinsic motivators, such as pride in work and relationships with patients, remain strong, substantial dissatisfaction persists regarding pay, benefits, limited opportunities for advancement, organizational communication, and administrative constraints. Consistent with Herzberg’s two-factor theory, the findings indicate that improving external factors like pay and policies may be necessary but insufficient alone. Sustaining intrinsic motivators like professional pride, recognition, and meaningful work is equally vital for long-term engagement.

Addressing dissatisfaction through equitable pay and benefit models, defined advancement ladders, supportive supervisory structures, and streamlined administrative systems may help stabilize the dental hygiene workforce. A coordinated, multi-dimensional strategy will likely be required to ensure workforce sustainability, protect access to preventative oral health services, and elevate the professional standing of dental hygienists within the broader healthcare system. Future research should incorporate longitudinal and multi-state comparisons to assess how policy reforms and workforce initiatives influence satisfaction trends over time and across diverse practice environments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the guidance and support of the doctoral dissertation committee members at the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine (LECOM) School of Health Services Administration: James A. Stikeleather, DBA, MBA (major professor), JoAnn Farrell Quinn, PhD, Elizabeth Kerns, DBA. Their mentorship and expertise contributed significantly to the development and completion of this research project.

Abbreviations

- DSO

Dental Support Organization

- FQHC

Federally Qualified Health Center

- JSS

Job Satisfaction Survey

- PDHA

Pennsylvania Dental Hygienists’ Association

- RDH

Registered Dental Hygienist

Author contributions

L.S.B wrote the manuscript text, prepared all figures and the tables and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol received exemption from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine Institutional Review Board (Protocol #32 − 016). The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As part of the IRB-approved protocol, the requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the anonymous nature of the survey. However, all participants were provided an introductory information sheet outlining the study’s purpose, risks, and confidentiality protection and were required to indicate understanding and agreement before beginning the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Boynes S, Megally H, Clermont D, Nieto V, Hawkey H, Cothron A. The financial and policy impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on US dental care workers. San Antonio, TX: American Institute of Dental Public Health; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennsylvania Coalition for Oral Health. Access to Oral Health Workforce Report Part II. 2022.

- 3.Lee JS, Somerman MJ. The importance of oral health in comprehensive health care. JAMA. 2018;320(4):339–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ADA Health Policy Institute in collaboration with American Dental Assistants Association. AD, Hygienists’ Association DANB, and IgniteDA,. Dental workforce shortages: Data to navigate today’s labor market. 2022.

- 5.Dorji T. Systematic Review Protocol: Determining Factors Affecting Workforce Retention in Dentistry. Research Square. 2024.

- 6.Badal M, Patel LDB. Jared vineyard and Lisa laspina. Job satisfaction, burnout, and intention to leave among dental hygienists in clinical practice. J Dent Hyg. 2021;95(2):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop JL. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on job satisfaction of dental hygienists and their intention to leave practice. The Ohio State University; 2022.

- 8.Han OS. A qualitative research on emotional labor and stress in dental hygienists. J Korean Soc Dent Hyg. 2020;20(6):797–807. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malcolm N, Boyd L, Giblin-Scanlon L, Vineyard J. Occupational stressors of dental hygienists in the United States. Work. 2020;65(3):517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel BM, Boyd LD, Vineyard J, LaSpina L. Job satisfaction, burnout, and intention to leave among dental hygienists in clinical practice. Am Dent Hygienists’ Association. 2021;95(2):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Network for Oral Health Access. Community Health Center Workforce Survey: Analysis of 2023 Results. 2023.

- 12.Gu J-Y, Lim S-R, Lee S-Y. Effects of organizational culture of dental office and professional identity of dental hygienists on organizational commitment. J Dent Hygiene Sci. 2017;17(6):516–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee B, Lee C, Choi I, Kim J. Analyzing determinants of job satisfaction based on two-factor theory. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12557. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spector PE. Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: development of the job satisfaction survey. Am J Community Psychol. 1985;13(6):693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. 2023.

- 16.Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Bulletin: Dental hygiene scope of practice; local anesthesia; Title 49—Professional and vocational standards. State Board of Dentistry [49 Pa. Code Ch. 33]. Pennsylvania Code2009. p. 6982.

- 17.Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Code § 33.205b. Practice as a public health dental hygiene practitioner. 2009.

- 18.Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Use of lasers in the dental office - statement of policy. 1995.

- 19.Pennsylvania Coalition for Oral Health. Access to Oral Health Workforce Report Part I. 2022.

- 20.Spector PE. Job satisfaction survey. 1994.

- 21.Bercasio LV, Rowe DJ, Yansane A-I. Factors associated with burnout among dental hygienists in California. Am Dent Hygienists’ Association. 2020;94(6):40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Zamel LG, Lim Abdullah K, Chan CM, Piaw CY. Factors influencing nurses’ intention to leave and intention to stay: an integrative review. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2020;32(4):218–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herzberg F, Mausner B, Snyderman BB. The motivation to work: Transaction; 2011.

- 24.Hill A. 2024 Salary Survey Report: The State of the RDH Career 2024 [updated January 3. Available from: https://www.rdhmag.com/career-profession/compensation/article/14302418/dental-hygiene-salaries-in-2024-the-state-of-the-rdh-career

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.