Abstract

Introduction

Acupuncture is increasingly utilised in primary care to manage chronic musculoskeletal pain, supported by a growing body of evidence. This rising adoption has driven demand for clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). We summarised the characteristics of recent acupuncture CPGs for osteoarthritis, low back pain, neck pain, and shoulder pain, and critically appraised their methodological quality.

Methods

We searched nine databases to identify acupuncture CPGs published from January 2014 to November 2024. Eligible CPGs were required to be developed by guideline committees and to include evidence-informed recommendations linked to clearly defined levels of evidence. Two independent reviewers extracted CPG characteristics and assessed methodological quality using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument.

Results

Of the 1,999 records screened, 17 CPGs were included, encompassing 35 recommendations. Shoulder pain was the most addressed condition (n = 14), followed by low back pain (n = 11), osteoarthritis (n = 8), and neck pain (n = 2). Various types of acupuncture were considered, with manual acupuncture featuring in most (n = 26) recommendations. Overall, 60% of the recommendations supported the use of acupuncture, comprising 5.7% strong recommendations and 54.3% weak or conditional recommendations. In contrast, 22.9% of recommendations offered no explicit guidance, while 17.1% advised against its use. Methodological assessment classified 10 CPGs as high quality, while seven were of moderate quality.

Conclusions

Contradictions exist among the included CPGs regarding whether acupuncture should be recommended for routine practice, potentially reflecting differences in clinical and cultural contexts. Local CPGs should be developed using rigorous methodology, ensuring the involvement of local stakeholders. An AGREE II extension should be developed for the methodological quality assessment of acupuncture CPGs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-025-05070-y.

Keywords: Practice guideline, Acupuncture, Complementary therapies, Musculoskeletal pain, Systematic review

Introduction

According to the Global Burden of Disease 2021, musculoskeletal disorders, represented by rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, low back and neck pain, and gout, accounted for approximately 162 million disability-adjusted life years, ranking first among all Level 2 causes for years of healthy life lost due to disability in both sexes combined [1]. Chronic pain resulting from musculoskeletal disorders adversely effects individuals’ physical, psychological, and social wellbeing, while also imposing a substantial financial burden on countries and healthcare systems worldwide [2]. In the United States alone, chronic pain, including musculoskeletal pain, is estimated to cost at least USD 560 billion per year in direct healthcare expenses and productivity losses [3]. Given its impact, it is increasingly recognised as one of the public health priorities, necessitating a more comprehensive understanding and targeted policy responses [4, 5].

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is typically managed at the primary care level with a range of pharmacological and non-pharmacological options. Pharmacological approaches generally include non-opioid analgesics (e.g., paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, and adjuvant medications (e.g., antidepressants, muscle relaxants, corticosteroids) [6, 7]. Non-pharmacological interventions recommended in clinical practice encompass supervised exercise programmes, psychological therapies, electrical physical modalities (e.g., transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation), and acupuncture [6, 7]. Education provided by primary care practitioners is also essential in empowering individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain to effectively manage their condition, equipping them with relevant knowledge and skills to optimise clinical outcomes and quality of life [6, 7].

Acupuncture is practised and officially regulated in over 100 World Health Organization Member States, particularly in countries across Asia, as an intervention of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and some other practices of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) [8]. Decades of research have been dedicated to evaluating acupuncture’s effectiveness and adverse events to support its application in clinical practice for various conditions and disorders [9, 10]. A recent individual patient data meta-analysis of high-quality trials indicated that acupuncture has a clinically relevant and persistent effect in the management of osteoarthritis, chronic headache, shoulder pain, and non-specific musculoskeletal pain, when compared to no acupuncture or sham acupuncture [11]. The increased uptake of acupuncture in clinical practice and the accumulation of supporting evidence have led to a growing demand for clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) [12], with the aims to provide evidence-based recommendations on indications, treatment duration, relevant acupoints, and information on potential adverse events and contraindications.

A 2018 bibliometric analysis examined trends in acupuncture use and the conditions addressed within its included 1,311 CPGs published between 1991 and 2017 [13]. Similarly, a recent systematic review evaluated 133 acupuncture CPGs published from 2010 to 2020 [14], with 39 focused on musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders. However, neither of them critically appraised the level of evidence underpinning the recommendations in these CPGs. Instead, they provided either a narrative overview of publication characteristics [13, 14] or, at most, evaluated the CPGs methodological quality and addressed whether the CPG developers had conducted an assessment of evidence level in terms of “Yes” or “No” only [14]. This omission leaves an important gap, as it remains unclear whether the recommendations are sufficiently robust to inform clinical decision-making.

Therefore, it is important to critically appraise existing CPGs to understand how acupuncture is positioned in the field of chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions. Rigorous guideline appraisal can identify areas of consensus, highlight inconsistencies, and inform efforts to improve guideline development and implementation.

This systematic review aims to synthesise acupuncture CPGs for chronic musculoskeletal pain, focusing on their recommendations about pain relief, physical function improvement, and quality of life improvement. It also seeks to provide a standardised summary of the levels of evidence supporting these recommendations and their corresponding grades, along with a critical appraisal of the CPGs’ methodological quality.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review based on PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [15]. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024620086).

Eligibility criteria

We included CPGs focusing on the use of acupuncture for three of the most prevalent chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions—osteoarthritis, low back pain, and neck pain [1]—as well as shoulder pain, another frequently encountered musculoskeletal pain in primary care [16]. Regardless of the publication language, eligible CPGs should be developed by guideline development committees or equivalent bodies and to provide detailed information on systematic literature search and evidence-informed recommendations linked to clearly defined levels of evidence. Those recommendations should focus on clinical outcomes including pain alleviation, as well as improvements in physical function and quality of life. No restrictions were applied regarding the applicable populations, types of acupuncture (e.g., manual acupuncture, electro-acupuncture) or intervention comparators (e.g., placebo, anti-inflammatory agents). For updated versions of CPGs, only the most recent publications were included.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched for eligible CPGs published between January 2014 and November 2024 across nine electronic databases, including Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Trip Medical Database, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Database, Guidelines International Network, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, WanFang, SinoMed, and Database of Chinese Sci-Tech Periodicals. In addition, we performed a hand search of the reference lists of excluded conference abstracts. All records were imported into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/) (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), where title and abstract screening, as well as full-text assessment, were conducted by two reviewers (LH, CNTL) independently. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by a third reviewer (RWSS).

Data extraction

A reviewer extracted three levels of information from each CPG, which were subsequently validated by another reviewer. CPG-level information included the first author, publication year, publication type (report or journal article), publishing organisation, country of origin, funding source, CPG type (acupuncture-specific, CAM, or comprehensive), and the chronic musculoskeletal pain addressed. Intervention-level information comprised the type of acupuncture, selection of acupoints, duration of treatment, potential adverse events, applicable populations, and the healthcare settings in which the interventions should be delivered. Recommendation-level information involved clinical outcome(s) and effectiveness summaries, the assessment system adopted for formulating recommendations and rating quality of evidence, the reported strength of recommendation, the reported level of evidence, and comparator(s) of the recommendation.

Evaluation of levels of evidence and grades of recommendations

The included CPGs employed various assessment systems to evaluate and report the quality of the evidence underpinning their recommendations and the rigour of the recommendations themselves. To address this variability, we adopted a standardised approach proposed by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) to assess the levels of evidence and grades of recommendations within the CPGs [17, 18].

Specifically, the level of evidence supporting a recommendation was rated based on the “Hierarchy of Evidence”, with systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials representing the highest level (i.e., Level 1) of evidence, while expert opinions without explicit critical appraisal are considered the lowest level (i.e., Level 5) [17, 18]. A minus sign (“-”) was used to indicate instances where an effect estimate had a wide confidence interval or a systematic review exhibited high heterogeneity, signifying a lack of conclusive evidence. In other words, a systematic review with high heterogeneity would be rated at Level 1-. The grade of a recommendation was determined by the level(s) of supporting evidence and the consistency of that evidence [17, 18]. Grade “A” recommendations are those supported by consistent Level 1 evidence, whereas Grade “D” recommendations are based on Level 5 evidence or evidence of any level that is troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive. The evaluation process was conducted independently by two reviewers (LH, CNTL), with any disagreements resolved through discussion.

Assessment of guideline methodological quality

We used the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument to assess the methodological quality of each included CPG [19]. The AGREE II instrument comprises 23 key items, organised within six domains, applicable to various disease areas and stages across the healthcare continuum. These six domains are: (i) scope and purpose; (ii) stakeholder involvement; (iii) rigour of development; (iv) clarity of presentation; (v) applicability; and (vi) editorial independence. Each key item was rated independently by two reviewers (LH, CNTL) on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Domain scores were calculated by summing the scores of the key items within each domain across two reviewers and then scaling this total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain [19]. For example, if one reviewer strongly agreed with all three key items in the domain “scope and purpose” (7 points * 3 items = 21 points), while the other reviewer provided neutral ratings (4 points * 3 items = 12 points), the score for this domain would be calculated as 75% ((33 [total obtain score] – 6 [minimum possible score]/(42 [maximum possible score] – 6 [minimum possible score]) * 100%). Upon completing the 23 items, the reviewers were required to provide two overall assessments of each CPG in terms of its overall quality (on a 7-point Likert scale) and whether to recommend the use of the CPG (Yes/Yes, with modifications/No). The overall quality score was calculated using the same approach applied for domain score calculation.

As there are no established cut-off scores for the domains or overall quality, we classified domain and overall scores below 50.0% as indicative of low quality, scores between 50.0% and 80.0% as moderate quality, and scores above 80.0% as high quality [14].

Data analysis

All extracted information and assessment results were appropriately tabulated and summarised narratively. No quantitative data synthesis was performed.

Results

Study selection

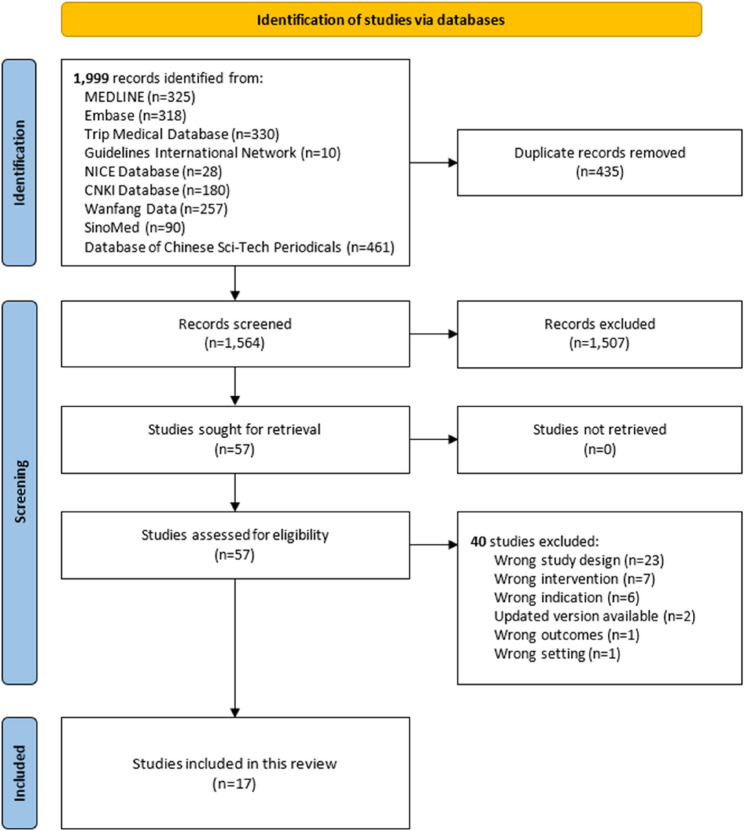

The literature search identified 1,999 records. After deduplication, 1,564 records were screened by title and abstract, and 57 full-text documents were assessed. Finally, 17 eligible CPGs focusing on chronic musculoskeletal pain management involving acupuncture were included. Figure 1 illustrates the literature selection process.

Fig. 1.

Flow of literature search and selection

Characteristics of the included clinical practice guidelines

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included CPGs. These 17 CPGs were published between 2017 and 2023, with nine (52.9%) appearing in peer-reviewed journals. The United States contributed the highest number of CPGs (n = 6; 35.3%), followed by Canada, the People’s Republic of China, and the United Kingdom, each producing two. All of them were funded by professional organisations, governments, or government-funded projects. Most (n = 14; 82.4%) were comprehensive CPGs, addressing interventions from more than one medical practice (e.g., conventional medicine, TCM), while two (11.8%) focused exclusively on TCM and one (5.9%) on traditional Korean medicine. Eight (47.1%) CPGs focused on the management of chronic low back pain and conditions contributing to low back pain, such as lumbar spinal stenosis and lumbar radiculopathy. Six (35.3%) CPGs addressed the management of hip and/or knee osteoarthritis, or osteoarthritis in general. Two (11.8%) CPGs each focused on the management of chronic neck pain (including cervical radiculopathy) and shoulder pain (including frozen shoulder) with acupuncture.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 17 included clinical practice guidelines

| First author | Title | Year | Type of publication | Organisation | Country of origin | Funding source | Type of CPG | Chronic musculoskeletal pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Qin | Traditional Chinese medicine for frozen shoulder: An evidence-based guideline | 2023 | Journal article | Not published by particular organisations | People’s Republic of China | The National Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation Team Project; The Chinese Medicine Evidence-based Capacity Improvement Project | CAM (Traditional Chinese medicine) | Frozen shoulder |

| 2. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons management of osteoarthritis of the knee (non-arthroplasty) evidence-based clinical practice guideline | 2021 | Report | The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons | United States | The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons | Comprehensive | Knee osteoarthritis |

| 3. Shirado | Formulation of Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) clinical practice guideline for the management of low back pain - The revised 2019 edition | 2022 | Journal article | The Japanese Orthopaedic Association | Japan | The Japanese Orthopaedic Association; The Japanese Society of Lumbar Spine Disorders | Comprehensive | Low back pain |

| 4. The North American Spine Society | Evidence-based clinical guidelines for multidisciplinary spine care: Diagnosis & treatment of low back pain | 2020 | Report | The North American Spine Society | United States | The North American Spine Society | Comprehensive | Low back pain |

| 5. Bussières | Non-surgical interventions for lumbar spinal stenosis leading to neurogenic claudication: A clinical practice guideline | 2021 | Journal Article | The Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative; The Bone and Joint Canada; The International Taskforce on Diagnosis and Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis | Canada | The Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation | Comprehensive | Lumbar spinal stenosis |

| 6. The Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense Evidence-Based Practice Work Group | VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain | 2022 | Report | VA and DoD Evidence-Based Practice Work Group | United States | The VA Evidence Based Practice, Office of Quality and Patient Safety | Comprehensive | Low back pain |

| 7. Kjaer | National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset neck pain or cervical radiculopathy | 2017 | Journal Article | The Danish Health Authority | Denmark | The Danish Finance Act | Comprehensive | Cervical radiculopathy |

| 8. Stochkendahl | National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy | 2017 | Journal Article | The Danish Health Authority | Denmark | The Danish Finance Act | Comprehensive | Lumbar radiculopathy |

| 9. Choi | Evidence Based (GRADE Approach) Korean Medicine clinical practice guidelines of manual acupuncture for the treatment of shoulder pain | 2017 | Journal Article | The Society of Korean Medicine Rehabilitation | South Korea | The Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine | CAM (Traditional Korean medicine) | Shoulder pain |

| 10. The Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense Evidence-Based Practice Work Group | VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the non-surgical management of hip & knee osteoarthritis | 2020 | Report | VA and DoD Evidence-Based Practice Work Group | United States | The VA Evidence Based Practice, Office of Quality and Patient Safety | Comprehensive | Hip osteoarthritis; knee osteoarthritis |

| 11. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and management | 2020 | Report | The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | United Kingdom | The UK Department of Health and Social Care | Comprehensive | Low back pain |

| 12. Luo | Acupuncture for treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A clinical practice guideline | 2023 | Journal Article | Not published by particular organisations | People’s Republic of China | The National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars; The Sichuan Provincial Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Special Project; The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes; The Innovation Team and Talents Cultivation Program of National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine | CAM (Traditional Chinese medicine) | Knee osteoarthritis |

| 13. Korownyk | PEER simplified chronic pain guideline: Management of chronic low back, osteoarthritic, and neuropathic pain in primary care | 2022 | Journal Article | The College of Family Physicians of Canada | Canada | The College of Family Physicians of Canada; The Ontario College of Family Physicians; The Alberta College of Family Physicians; The Saskatchewan College of Family Physicians | Comprehensive | Low back pain |

| 14. Qaseem | Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians | 2017 | Journal Article | The American College of Physicians | United States | The American College of Physicians | Comprehensive | Low back pain |

| 15. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | Osteoarthritis in over 16s: Diagnosis and management | 2022 | Report | The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | United Kingdom | The UK Department of Health and Social Care | Comprehensive | Osteoarthritis |

| 16. Blanpied | Neck pain: Revision 2017 clinical practice guidelines | 2017 | Report | The American Physical Therapy Association | United States | The American Physical Therapy Association | Comprehensive | Neck Pain |

| 17. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis | 2018 | Report | The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | Australia | The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | Comprehensive | Hip osteoarthritis; knee osteoarthritis |

CAM Complementary & alternative medicine, CPG Clinical practice guideline, DoD Department of Defense, VA Veterans Affairs

Details of acupuncture interventions

Table 2 and Table S1, Supplementary File, present the details of the acupuncture interventions examined in the included CPGs. A total of 35 clinical recommendations were identified across 17 CPGs. Of these, 14 (40.0%) on shoulder pain, 11 (31.4%) focused on low back pain, eight (22.9%) on osteoarthritis, and two (5.7%) on neck pain. Manual or traditional acupuncture was the most frequently discussed intervention type, featured in 26 (74.3%) recommendations, followed by electro-acupuncture (n = 10; 28.6%), laser acupuncture (n = 4; 11.4%), dry needling (n = 4; 11.4%), warm needle acupuncture (n = 3; 8.6%), and fire needle (n = 2; 5.7%). Nine (25.7%) recommendations involved performing manual acupuncture on specific acupoints (e.g., Ashi points) or with specific needle manipulation techniques (e.g., deep needle insertion). Five (14.3%) recommendations combined acupuncture with physical therapy, self-exercise, or other modalities such as therapeutic ultrasound.

Table 2.

Details of the interventions examined in the clinical practice guidelines

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Chronic musculoskeletal pain | |

| Shoulder pain | 14 (40.0) |

| Low back pain | 11 (31.4) |

| Knee osteoarthritis | 5 (14.3) |

| Hip osteoarthritis | 2 (5.7) |

| Osteoarthritis (not specified) | 1 (2.9) |

| Neck pain | 2 (5.7) |

| Type of acupuncture | |

| Manual or traditional acupuncture | 26 (74.3) |

| Electro-acupuncture | 10 (28.6) |

| Laser acupuncture | 4 (11.4) |

| Dry needling | 4 (11.4) |

| Warm needle | 3 (8.6) |

| Fire needle | 2 (5.7) |

| Specified acupoint selection | |

| Yes | 9 (25.7) |

| No | 26 (74.3) |

| Provided instructions on acupuncture administration | |

| Yes | 7 (20.0) |

| No | 28 (80.0) |

| Provided information on adverse events or harms | |

| Yes | 14 (40.0) |

| No | 21 (60.0) |

| Provided information on applicable patient population | |

| Yes | 35 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) |

| Professionals for administering acupuncture | |

| All clinicians | 12 (34.3) |

| Traditional & complementary medicine practitioners only | 11 (31.4) |

| Medical doctors or specialists only | 2 (5.7) |

| Not specified or not applicable | 10 (28.6) |

| Settings for administering acupuncture | |

| Traditional & complementary medicine settings | 11 (31.4) |

| Any settings or all levels of care | 9 (25.7) |

| Primary care settings | 3 (8.6) |

| Not specified | 12 (34.3) |

Twenty-three (65.7%) recommendations lacked details on acupoint selection or implementation specifics, such as patient positioning or intervention duration. In addition, 21 (60.0%) recommendations did not provide information on adverse events or potential harms associated with the interventions. While all clinical recommendations identified the populations for whom the interventions were intended, fewer specified the professionals responsible for administering the interventions (n = 25; 71.4%) or the settings in which they should be performed (n = 23; 65.7%).

Details of clinical recommendations

Comparators of recommendations and clinical effectiveness of interventions

Table 3 and Table S2, Supplementary File, provide details of the 35 clinical recommendations discussed in the included CPGs. Thirty-eight (80.0%) explicitly mentioned the comparators used in their supporting evidence, with sham acupuncture being the most reported. Other comparators included alternative types of acupuncture that were not the primary interventions or sham interventions, usual care or no treatment, anti-inflammatory or analgesic agents, and physical therapy or orthopaedic treatments. Acupuncture demonstrated significant benefits for pain relief in osteoarthritis, low back pain, neck pain, and shoulder pain across 16 (45.8%) recommendations, with varying effect sizes and durations. Similarly, they showed significant effects on functional improvement for all four conditions in 16 (45.8%) recommendations, while superior effects on quality of life improvement were observed only for low back pain and osteoarthritis in three (8.6%) recommendations.

Table 3.

Details of the 35 clinical recommendations discussed in the clinical practice guidelines

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Comparators | |

| Sham acupuncture | 12 (34.3) |

| Other types of (sham) acupuncture | 11 (31.5) |

| Usual care or no treatment | 10 (28.6) |

| Anti-inflammatory or analgesic agents/injections | 3 (8.6) |

| Exercise, physical therapy, or orthopaedic treatments | 3 (8.6) |

| Not specified | 7 (20.0) |

| Significantly positive clinical effectiveness | |

| Pain relief | 16 (45.8) |

| Functional improvement | 16 (45.8) |

| Quality of life improvement | 3 (8.6) |

| Assessment system | |

| GRADE approach | 18 (51.5) |

| Good Practice Point grading system | 11 (31.5) |

| North American Spine Society Levels of Evidence | 4 (11.5) |

| American College of Physicians Grading System | 1 (2.9) |

| Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence | 1 (2.9) |

| Reported direction of the recommendation | |

| Recommended or suggested for | 21 (60.0) |

| Recommended or suggested against | 6 (17.2) |

| Did not make recommendations | 8 (22.9) |

| Reported quality of evidence* | |

| High | 4 (11.5) |

| Moderate | 8 (22.9) |

| Low | 10 (28.6) |

| Very low | 10 (28.6) |

| Not reported or not applicable | 3 (8.6) |

| Standardised levels of evidence† | |

| Level 1 | 3 (8.6) |

| Level 1- | 16 (45.8) |

| Level 2 | 3 (8.6) |

| Level 2- | 2 (5.8) |

| Level 3 | 0 (0) |

| Level 4 | 0 (0) |

| Level 5 | 11 (31.5) |

| Standardised grades of recommendations† | |

| Grade A | 3 (8.6) |

| Grade B | 3 (8.6) |

| Grade C | 5 (14.3) |

| Grade D | 24 (68.6) |

CEBM Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, GRADE Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

*When a recommendation was supported by multiple pieces of evidence of varying quality, the lowest quality level was used

†Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence framework was adopted to standardise the levels of evidence and grades of recommendations of clinical recommendations

Reported direction and strength of recommendations

More than half (n = 18; 51.5%) of the clinical recommendations were formulated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach [Table 3 and Table S2, Supplementary File]. Eleven (31.5%) recommendations from a single CPG were generated using the “Good Practice Point” 5-point grading system developed by its authors. Three other CPGs, respectively, utilised the North American Spine Society Levels of Evidence, the American College of Physicians Grading System, and the Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence for formulating their recommendations.

Among the 35 clinical recommendations, 21 (60.0%) advised or suggested the use or consideration of acupuncture for managing shoulder pain (n = 13; 37.1%), low back pain (n = 4; 11.4%), neck pain (n = 2; 5.7%), and knee osteoarthritis (n = 2; 5.7%). However, only two of the 21 recommendations were strong recommendations, focused on shoulder pain. Eight (22.9%) clinical recommendations did not make explicit suggestions, while six (17.1%) advised against the use of acupuncture. The negative recommendations conflicted with the positive ones, opposing the use of acupuncture for low back pain (n = 2; 5.7%), neck pain (n = 1; 2.9%), general osteoarthritis (n = 1; 2.9%), knee osteoarthritis (n = 1; 2.9%), and hip osteoarthritis (n = 1; 2.9%). Regarding the reported quality of evidence, only four (11.5%) recommendations were based exclusively on the highest quality evidence, whereas 20 (57.2%) were supported entirely or partially by low- or very low-quality evidence.

Standardised levels of evidence and grades of recommendations

In terms of the level of evidence for the clinical recommendations, evaluated using the Oxford CEBM approach, only three (8.6%) were classified at Level 1, the highest level [Table 3 and Table S2, Supplementary File]. Eighteen (51.6%) recommendations were rated as Level 1- or Level 2- due to the heterogeneity of the supporting systematic reviews or the heterogeneity of the supporting trials with a high risk of bias, respectively. A total of 11 (31.5%) recommendations were rated at Level 5, primarily due to the inclusion of poor-quality observational studies or reliance solely on clinical opinion. Regarding the grade of recommendation, three (8.6%) clinical recommendations were classified as Grade “A” based on their Level 1 evidence. In contrast, the majority (n = 24; 68.6%) were rated Grade “D” due to heterogeneity or Level 5 evidence.

Two of the Grade “A” recommendations were moderate positive suggestions for the use of laser acupuncture and manual acupuncture or electro-acupuncture for chronic low back pain. The remainder made neither positive or negative suggestions on the use of fire needle, electro-acupuncture, or warm needle for hip osteoarthritis.

Methodological quality of the included clinical practice guidelines

Table 4 summarises the results of the methodological quality appraisal for the 17 included CPGs. The CPGs generally demonstrated high methodological quality, with median scores of ≥ 80.0% across five of the six AGREE II domains. The exception was the “applicability” domain, which had a median score of 58.3%, indicating moderate quality. Within this domain, only four (23.5%) CPGs were rated as high quality, six (35.3%) as moderate quality, and the remainder as low quality. In contrast, a significant proportion of CPGs achieved high-quality ratings in the domains of “scope and purpose” (n = 14; 82.4%), “stakeholder involvement” (n = 11; 64.7%), “rigour of development” (n = 15; 88.2%), “clarity of presentation” (n = 14; 82.4%), and “editorial independence” (n = 11; 64.7%), with the remaining CPGs in these domains rated as moderate quality. In terms of overall quality, 10 (25.0%) of the included CPGs were rated as high quality, while the remainder were rated as moderate quality, with a median score of 87.5%. A total of six (35.3%) CPGs were recommended for use in their current form by both reviewers, while eight (47.1%) and three (17.6%) were deemed to require modifications before use by one and both reviewers, respectively.

Table 4.

Results of the methodological quality appraisal for the clinical practice guidelines

| Title | Year | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Domain 5 | Domain 6 | Overall quality | Recommendation of use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese medicine for frozen shoulder: An evidence-based guideline | 2023 | 100.0% | 66.7% | 92.7% | 100.0% | 58.3% | 75.0% | 91.7% | Yes = 0; Yes with modifications = 2 |

| American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons management of osteoarthritis of the knee (non-arthroplasty) evidence-based clinical practice guideline | 2021 | 100.0% | 66.7% | 94.8% | 100.0% | 81.3% | 100.0% | 83.3% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| Formulation of Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) clinical practice guideline for the management of low back pain - The revised 2019 edition | 2022 | 100.0% | 72.2% | 66.7% | 80.6% | 41.7% | 87.5% | 75.0% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| Evidence-based clinical guidelines for multidisciplinary spine care: Diagnosis & treatment of low back pain | 2020 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 95.8% | 55.6% | 66.7% | 75.0% | 91.7% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| Non-surgical interventions for lumbar spinal stenosis leading to neurogenic claudication: A clinical practice guideline | 2021 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 94.4% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | Yes = 2; Yes with modifications = 0 |

| VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain | 2022 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 88.5% | 100.0% | 87.5% | 87.5% | 91.7% | Yes = 2; Yes with modifications = 0 |

| National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset neck pain or cervical radiculopathy | 2017 | 83.3% | 83.3% | 88.5% | 97.2% | 37.5% | 100.0% | 75.0% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy | 2017 | 94.4% | 94.4% | 96.9% | 94.4% | 33.3% | 100.0% | 75.0% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| Evidence Based (GRADE Approach) Korean Medicine clinical practice guidelines of manual acupuncture for the treatment of shoulder pain | 2017 | 100.0% | 94.4% | 97.9% | 77.8% | 31.3% | 75.0% | 91.7% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the non-surgical management of hip & knee osteoarthritis | 2020 | 83.3% | 100.0% | 87.5% | 94.4% | 83.3% | 75.0% | 91.7% | Yes = 2; Yes with modifications = 0 |

| Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and management | 2020 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | Yes = 2; Yes with modifications = 0 |

| Acupuncture for treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A clinical practice guideline | 2023 | 88.9% | 88.9% | 83.3% | 94.4% | 58.3% | 100.0% | 75.0% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| PEER simplified chronic pain guideline: Management of chronic low back, osteoarthritic, and neuropathic pain in primary care | 2022 | 75.0% | 63.9% | 76.0% | 100.0% | 41.7% | 75.0% | 58.3% | Yes = 0; Yes with modifications = 2 |

| Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians | 2017 | 69.4% | 72.2% | 87.5% | 94.4% | 43.8% | 75.0% | 66.7% | Yes = 0; Yes with modifications = 2 |

| Osteoarthritis in over 16s: Diagnosis and management | 2022 | 100.0% | 66.7% | 84.4% | 66.7% | 35.4% | 87.5% | 75.0% | Yes = 1; Yes with modifications = 1 |

| Neck pain: Revision 2017 clinical practice guidelines | 2017 | 77.8% | 80.6% | 91.7% | 100.0% | 62.5% | 100.0% | 83.3% | Yes = 2; Yes with modifications = 0 |

| Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis | 2018 | 100.0% | 94.4% | 85.4% | 100.0% | 68.8% | 100.0% | 91.7% | Yes = 2; Yes with modifications = 0 |

DoD Department of Defense, VA Veterans Affairs

Discussion

Summary of findings

This study reviewed 17 CPGs with 35 clinical recommendations regarding the use of acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain, published between 2014 and 2024. Among these recommendations, the most frequently addressed condition was shoulder pain and frozen shoulder (40.0%), followed by low back pain and related conditions (31.4%), general, hip, or knee osteoarthritis (22.9%), and neck pain and related conditions (5.7%). Various types of acupuncture were considered, but manual acupuncture was the most discussed, featuring in 26 (74.3%) recommendations. 60% of the clinical recommendations suggested the use of acupuncture, while 22.9% did not make explicit suggestions, and 17.1% advised against its use. The grades of recommendations varied, with only 8.6% achieving the highest grade, while the majority (68.6%) received the lowest grade, indicating the lack of methodological rigour of their supporting evidence. According to the AGREE II appraisal, the 17 CPGs demonstrated high methodological quality, with median scores of ≥ 80.0% across five of the six domains, except for the “applicability” domain.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review synthesised acupuncture CPGs for chronic musculoskeletal pain published over the past decade (2014–2024), identified through nine international electronic databases without language restrictions. It extracted details of their clinical recommendations, provided a standardised summary of the levels of evidence supporting these recommendations and their corresponding grades using the Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence approach, and critically appraised the methodological quality of the CPGs using the AGREE II instrument.

This work has some limitations. First, information in the included publications was insufficient to allow a robust analysis of the factors influencing the direction of recommendations. Second, although we did not impose language restrictions in our inclusion criteria, our search was limited to major English and Chinese databases. This decision assumed that international publications from other countries, such as Japan and Korea, would include English abstracts indexed in these databases. However, this approach may have led to the omission of relevant guidelines published exclusively in other languages without English abstracts. While our search did identify and screen records in Japanese and Korean, none ultimately met our pre-defined eligibility criteria for inclusion. Third, while we have aimed to provide a standardised level for each piece of evidence and a consistent grade for each recommendation to support comparison across the included CPGs, we acknowledge that these may not fully capture the nuances of each guideline. We therefore encourage readers to also consider the strength of recommendations and quality of evidence as reported by the original developers when making decisions.

Implications

Acupuncture has been recommended for pain management by international and local authorities. However, our study revealed significant discrepancies and contradictions among existing acupuncture CPGs regarding the recommendations for the use of acupuncture in chronic musculoskeletal pain management. One reason for this may be that, in addition to clinical evidence on benefits and harms, guideline developers might also need to consider other factors such as the interventions’ acceptability, feasibility, costs, and the preferences of patients and practitioners. For instance, in regions where CAM is an integral part of mainstream medical practice (e.g., South Korea, the People’s Republic of China), guideline developers might be more inclined to consider acupuncture as a widely accepted and preferred intervention for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Considering the existing infrastructure—both in terms of clinical expertise and physical resources—acupuncture may be deemed feasible for all stakeholders within these communities. Additionally, implementation costs may be relatively low due to its extensive utilisation in these regions. These factors might have played an essential role in recommendation formulation, especially given the lack of high-quality evidence on the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture interventions, as shown in this review and in a recent cross-sectional methodological survey on acupuncture meta-analyses [20]. Therefore, before applying the clinical recommendations to practice, practitioners should evaluate the rationales behind such recommendations and ensure their applicability to their clinical and, more importantly, cultural circumstances [21]. Future studies should also assess the cost-effectiveness of these recommendations to support their implementation in real-world practice. Where appropriate, locally developed or adapted CPGs by committees consisting of local practitioners, field experts, policymakers, patients, and caregivers can better address context-specific factors such as regulatory environments, professional training, patient expectations, and healthcare infrastructure, These committees may utilise the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT framework [22, 23], which offers guidance on adopting existing recommendations from other CPGs, adapting them to developers’ own context, or creating new recommendations de novo.

Another noteworthy observation from this review is that a significant number (65.7%) of clinical recommendations for acupuncture did not provide practical details regarding the specific acupoints for the conditions, the required manipulation techniques and patient positioning, the duration of each treatment session, and the minimum number of sessions needed before reviewing the treatment plan. More importantly, the required frequencies and intensities for electro-acupuncture were not explicitly covered by almost all the recommendations. Without these details, the CPGs may provide little, if any, clinical guidance to practitioners and may, in turn, jeopardise their confidence in resorting to guidelines in general. Future research should focus on the implementation or practical aspect of acupuncture, in addition to its effectiveness and safety, to provide empirical evidence to support the development of CPGs that are more useful for routine practice.

This review synthesised all existing high-quality CPGs on acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain, restricting the scope to those developed by guideline development committees employing robust methodology, with the aim of maximising clinical relevance. Yet, these criteria likely excluded a substantial number of TCM-specific CPGs, which are often formulated through expert consensus without adhering to or reporting the formal methodologies typically used in modern evidence-based guideline development [24]. This raises an important question for researchers and practitioners: how should the balance between expert consensus and clinical evidence be weighted in TCM (and other forms of CAM), and more critically, how can the underlying ideological tensions between traditional and modern medical research be reconciled? Given the increasing familiarity of TCM practitioners with TCM-specific CPGs [24], particularly in light of the recent surge in relevant publications [25], addressing these considerations will be fundamental to advancing evidence-based practice in this field.

Moreover, to support the evaluation of the methodological quality of acupuncture CPGs, we propose the future development of an AGREE II extension tailored to TCM domain [26]. A key addition to the current instrument could be the availability and clarity of reporting on the diagnostic criteria for pattern (or syndrome) differentiation. As a fundamental aspect of TCM and certain other forms of CAM, pattern differentiation involves a comprehensive analysis of a patient’s clinical features to identify the location, cause, and nature of the disease (collectively as the “diagnostic pattern”) [8], aiming to guide the selection of appropriate treatment principles. The extension should also facilitate the critical appraisal of the associations between diagnostic patterns and corresponding treatment principles [26], as well as the location of each acupoint if the Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature is not adopted by the acupuncture CPGs [27].

To enhance the adoption of acupuncture CPGs for managing chronic musculoskeletal pain, future research may benefit from incorporating stakeholder interviews guided by established implementation science frameworks, such as the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [28]. The TDF includes 14 domains derived from 128 constructs across 33 theories in health and social psychology related to behaviour change. These domains provide a comprehensive lens through which to examine the behavioural determinants affecting CPG uptake at individual, organisational, and system levels. Building on this, the Behaviour Change Wheel can be applied to conduct a behavioural diagnosis, identifying specific targets for intervention to support the effective integration of CPGs into clinical practice [29].

Conclusions

Significant contradictions exist among recent CPGs on acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain, particularly regarding whether it should be recommended for routine practice, even for the same conditions. Considering the heterogeneity of clinical and cultural contexts, it may be beneficial to develop local CPGs using rigorous methodology, ensuring the involvement of local stakeholders and considering factors such as acceptability, feasibility, costs, and the preferences of both patients and practitioners. A more appropriate tool should also be developed for the rigorous assessment of the methodological quality of acupuncture CPGs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

LH: Methodology; data curation; investigation; formal analysis; visualisation; project administration; writing—original draft. CNTL: Investigation; formal analysis; writing—review and editing. HC, ECLY: Resources; validation; writing—review and editing. FPYL, YCC: Writing—review and editing. IXW, SYSW: Conceptualisation; writing—review and editing. RWSS: Conceptualisation; funding acquisition; supervision; writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Chinese Medicine Development Fund of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government (Reference number: 23B2/021A). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary File.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Metrics: Musculoskeletal disorders - Level 2 cause. 2024. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-musculoskeletal-disorders-level-2-disease. Accessed Nov 1 2024.

- 2.Mose S, Kent P, Smith A, Andersen JH, Christiansen DH. Trajectories of musculoskeletal healthcare utilization of people with chronic musculoskeletal pain–a population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2021. 10.2147/CLEP.S323903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the united States. J Pain. 2012;13(8):715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg DS, McGee SJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blyth FM, Van Der Windt DA, Croft PR. Chronic disabling pain: A significant public health problem. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(1):98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary (BNF): Pain, chronic. 2024. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/pain-chronic/. Accessed Nov 1 2024.

- 7.Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain - United states, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO international standard terminologies on traditional Chinese medicine. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu B, Chen B, Guo Y, Tian L. Acupuncture – a National heritage of China to the world: international clinical research advances from the past decade. Acupunct Herbal Med. 2021. 10.1097/HM9.0000000000000017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng GE, Rausch SM, Jones LW, et al. Complementary therapies and integrative medicine in lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):e420S-e36S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(5):455–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu L, Zhang Y, Tang X, et al. Evidence on acupuncture therapies is underused in clinical practice and health policy. BMJ. 2022;376:e067475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birch S, Lee MS, Alraek T, Kim TH. Overview of treatment guidelines and clinical practical guidelines that recommend the use of acupuncture: a bibliometric analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(8):752–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang X, Shi X, Zhao H, et al. Characteristics and quality of clinical practice guidelines addressing acupuncture interventions: a systematic survey of 133 guidelines and 433 acupuncture recommendations. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e058834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucas J, van Doorn P, Hegedus E, Lewis J, van der Windt D. A systematic review of the global prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence. (March 2009). 2024. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009. Accessed Nov 1 2024.

- 18.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho L, Ke FYT, Wong CHL, et al. Low methodological quality of systematic reviews on acupuncture: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dizon JM, Machingaidze S, Grimmer K. To adopt, to adapt, or to contextualise? The big question in clinical practice guideline development. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. Grade evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klugar M, Lotfi T, Darzi AJ, et al. Grade guidance 39: using GRADE-ADOLOPMENT to adopt, adapt or create contextualized recommendations from source guidelines and evidence syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;174:111494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Wang C, Shang H, Yang K, Norris SL. Clinical practice guidelines in China. BMJ. 2018;360:j5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Zhang C, Zha Q, et al. A national survey of Chinese medicine doctors and clinical practice guidelines in China. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie X, Wang Y, Li H. Agree II for TCM: tailored to evaluate methodological quality of TCM clinical practice guidelines. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1057920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Standard acupuncture nomenclature: a brief explanation of 361 classical acupuncture point names and their multilingual comparative list. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary File.