Abstract

Background

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), or tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT), is a locally aggressive soft tissue tumor primarily affecting the synovium of joints, particularly the knee. In PVNS, the synovial tissue thickens and becomes aggressive, leading to joint destruction, a process reminiscent of the tissue remodeling seen in autoimmune diseases. Despite being considered benign, PVNS often leads to severe joint damage and has a high recurrence rate following treatment. The underlying molecular mechanisms of PVNS remain poorly understood, necessitating further research to uncover its pathogenesis and identify potential therapeutic targets. This study aims to investigate the pathological mechanisms of PVNS, focusing on the role of metabolic pathways, immune cell infiltration, and osteoclast differentiation in the progression of the disease.

Methods

Synovial fluid samples from PVNS patients were subjected to high-throughput proteomic and metabolomic analyses. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) and metabolites were identified, and pathway enrichment analysis was performed. Western blot validation and two-way orthogonal partial least squares (O2PLS) analysis confirmed key findings and explored the relationships among identified biomarkers.

Results

A total of 156 DEPs and 62 differential metabolites were identified. The “Osteoclast differentiation signalling” and “Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) survival signalling” pathways were significantly upregulated in PVNS samples, with Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily Member 11 (TNFSF11), Cathepsin K (CTSK), Adhesion G Protein-Coupled Receptor E5 (ADGRE5), and NF-κB showing marked increases in expression. Metabolomic analysis revealed that “Linoleic acid metabolism” and “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” pathways were enhanced in PVNS, with metabolites such as 13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid and 13-OxoODE being highly expressed. Western blot validation confirmed the elevated levels of ADGRE5, TNFSF11, CTSK, and NF-κB, suggesting a link between enhanced energy metabolism, lipid oxidation, and osteoclast differentiation.

Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of metabolic adaptations and immune cell activity in the progression of PVNS. The findings suggest that targeting ADGRE5 and NF-κB could offer new therapeutic strategies for controlling disease progression and reducing joint destruction in PVNS patients. Further research is needed to elucidate this disease’s specific regulatory mechanisms and cell types.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04358-7.

Keywords: Pigmented villonodular synovitis, Osteoclast differentiation, Proteomics, Metabolomic

Background

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), also known as tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT), predominantly affects individuals aged 20 to 40 years, targeting synovial joints or tendon sheaths [1–3]. PVNS is a locally aggressive soft tissue tumor with poorly defined margins, most commonly found in weight-bearing joints, with the knee being the most frequently affected site (60–70%) [4]. It typically presents with monoarticular pain, swelling, brownish joint effusion, and stiffness, with the knee being the most commonly involved joint [5, 6]. Unlike the typically preserved joint space in other conditions, PVNS often leads to lytic lesions and cartilage destruction on both sides of the hip joint, particularly near the synovial regions [7, 8]. Surgical resection combined with radiotherapy remains the standard treatment approach [8–10]. However, the high recurrence rate (23–78%) poses a significant challenge in clinical practice [11, 12]. Until now, the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying PVNS pathogenesis have remained poorly understood [13]. Elucidating the pathological mechanisms of PVNS is crucial, as they may provide valuable insights for its diagnosis and treatment.

Over the years, various approaches have been employed to investigate the pathological changes associated with PVNS. Studies combining proteomics and RNA-seq analyses have revealed extensive immune cell infiltration and increased cytokine secretion in synovial tissues from PVNS patients [14, 15]. In PVNS, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) plays a significant role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), enhancing the migration and invasion of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs) and contributing to the progression of PVNS tissue invasion [3]. The release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) by FLSs can be triggered by several extracellular factors, such as inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 (IL-1)[13, 16]. PVNS patients exhibit elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which contribute to the inflammatory environment. This cytokine profile is commonly seen in autoimmune conditions, where an overactive immune response leads to tissue damage and chronic inflammation.

In PVNS, chronic synovial inflammation and aggressive bone erosion are hallmark features, driven by complex interactions between inflammatory cytokines, immune cell infiltration, and osteoclast activation[3, 14, 17]. While these inflammatory and erosive mechanisms have been extensively studied, accumulating evidence suggests that metabolic alterations also play a critical role in sustaining synovial hyperplasia and modulating the local microenvironment[18, 19].

Metabolism, which is tightly linked to nutrient availability and cellular demands, serves as a key interface between intrinsic cellular behavior and extrinsic inflammatory cues [20]. Like many tumorous conditions, PVNS appears to shift away from classical energy production pathways such as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), instead relying on alternative metabolic routes to support proliferation, inflammation, and tissue remodeling [20]. However, the specific metabolic alterations in PVNS remain poorly defined [21].

In the context of PVNS, integrating metabolomic analysis can illuminate previously unexplored metabolic disruptions, offering a more nuanced understanding of disease etiology [22]. This integration holds the potential to identify metabolic signatures that may serve as both diagnostic tools and therapeutic targets, thereby transforming the clinical management of PVNS and similar joint diseases [23]. Furthermore, leveraging multi-omics approaches that combine metabolomics with proteomics or genomics could unveil intricate regulatory networks, further accelerating the development of personalized treatment strategies [24].

In this study, we firstly integrated multi-omics strategies—incorporating metabolomics and proteomics—to comprehensively investigate synovial fluid in PVNS, a biological matrix accessible through minimally invasive procedures. Our integrative omics analysis identified aberrant osteoclast differentiation, dysregulation of Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling, and altered lipid metabolism as potential key contributors to PVNS pathogenesis. These findings are further validated using both synovial fluid and tissue samples, reinforcing the robustness and reliability of our results. Notably, adhesion G protein-coupled receptor E5 (ADGRE5) and NF-κB are closely associated with macrophage-to-osteoclast differentiation, highlighting their potential as therapeutic targets. Our findings suggest that adhesion G protein-coupled receptors (aGPCRs) may represent a novel class of targets for PVNS treatment.

Methods

Patients and clinical samples

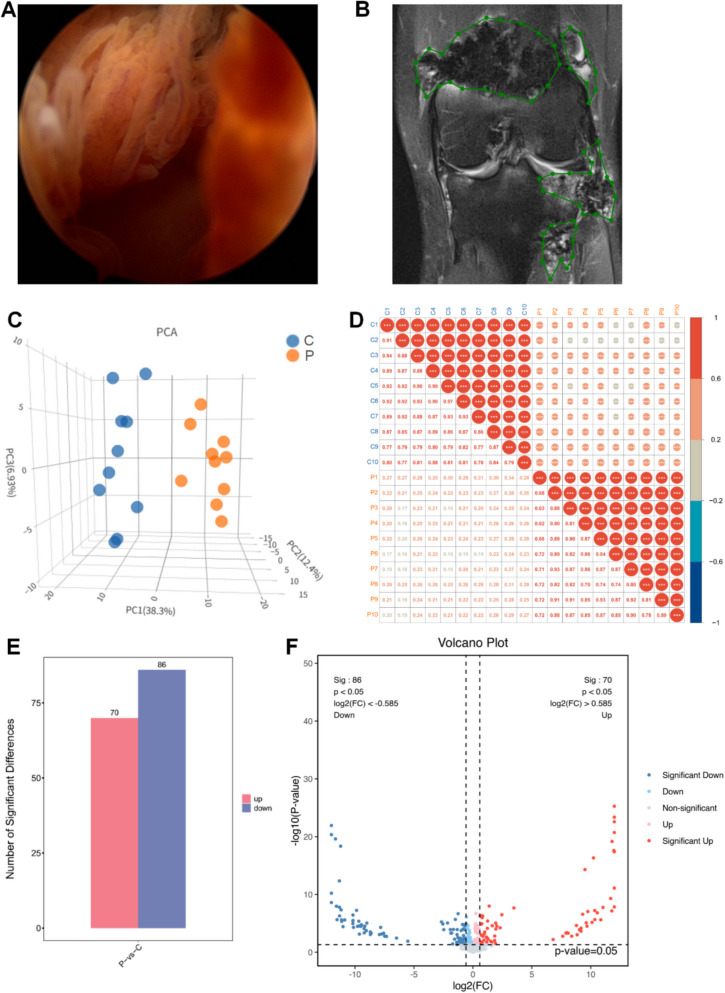

This study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (No. 125 2020-(921)). The baseline characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1. Arthroscopic images showed red-brown synovial tissue in PVNS patients, which was markedly hyperplastic compared to the control group due to hemosiderin deposition (Fig. 1A). MRI revealed that the synovial tissue in PVNS patients displayed high signal intensity in the fat-saturated proton density sequence (Fig. 1B). The knee joints of PVNS patients exhibited severe joint swelling and cartilage erosion (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| P (PVNS group) | C (control group) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 10 | |

| Age (years) | 36.10 ± 11.26 | 40.10 ± 12.11 | |

| Male, gender | 2 (20%) | 2(20%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.86 ± 2.885 | 22.60 ± 2.382 | ns |

| Swollen joints | 80% | 20% | |

| Arthrohydrops | 80% | 20% | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L, < 5) | 5.751 ± 3.947 | 1.915 ± 1.053 | 0.0137 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L, > 0.9) | 1.043 ± 0.2906 | 1.374 ± 0.2473 | 0.0134 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L, < 0.40) | 2.879 ± 1.091 | 2.512 ± 0.7149 | ns |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) (2.8–5.7) | 4.602 ± 0.6257 | 4.274 ± 0.8119 | ns |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) (0.29–1.83) | 2.216 ± 1.303 | 1.151 ± 0.7565 | 0.0383 |

| ESR (< 21) | 28.10 ± 18.42 | 8.400 ± 5.481 | 0.0082 |

| WBC (3.5–9.5) | 7.046 ± 2.785 | 5.388 ± 0.9940 | ns |

| MO# (0.1–0.6) | 0.429 ± 0.2166 | 0.3590 ± 0.1136 | ns |

| LY (1.1–3.2) | 1.743 ± 0.5651 | 1.997 ± 0.3764 | ns |

Fig. 1.

Proteomics of differential protein expression. A Arthroscopic observation of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). B MRI Features of PVNS (the green box indicates the PVNS lesion tissue). C Principal component analysis (3D PCA) plot based on protein expression data. The first three principal components explain 38.3%, 12.4%, and 6.93% of the total variance, respectively. Samples were colored by group. D Sample correlation analysis: in the upper triangle (above the diagonal), red indicates positive correlations, blue indicates negative correlations, and the size of the circles represents the magnitude of the correlation coefficients. The numerical values in the lower triangle (below the diagonal) display the correlation coefficients, with colors differentiating between positive and negative correlations. The different colors of the sample labels indicate different groups. E Statistical plot of differential proteins. F Volcano plot of differential generation proteins in joint fluid; red represents metabolites up-regulated in group T compared to group N, blue represents down-regulated

Biological samples: We enrolled ten patients with knee PVNS who were admitted to our hospital between December 1, 2019, and May 30, 2020, and met the inclusion criteria. We retrospectively analyzed these patients’ clinical characteristics, imaging changes, and arthroscopic findings. The PVNS group specimens were obtained from patients diagnosed with knee PVNS through postoperative pathological examination, while the control group specimens were obtained from patients with meniscus or ligament injuries. Patients with infections, autoimmune diseases, and metabolic disorders were excluded. Synovial fluid from both groups was collected during arthroscopy, centrifuged, and stored in liquid nitrogen, then transported and frozen at − 80 °C for future use. General clinical and demographic data for the PVNS group (P) and the relative control group (C) are shown in Table 1. Patients with PVNS undergo arthroscopic synovectomy to remove the affected synovial tissue. For meniscus injuries, the treatment is based on the severity of the damage, with options including meniscus repair or meniscectomy. Ligament injuries are treated according to the severity, with options for ligament repair or reconstruction surgery. Among the 10 PVNS patients (mean age = 36.10 ± 11.26 years), 2 (20%) were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) (23.86 ± 2.885 vs. 22.60 ± 2.382 kg/m2, p > 0.05), C-reactive protein (CRP) (mg/L, 5.751 ± 3.947 vs. 1.915 ± 1.053; p = 0.0137), triglycerides (TG) (mmol/L, 2.216 ± 1.303 vs. 1.151 ± 0.7565; p = 0.0383), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (28.10 ± 18.42 vs. 8.400 ± 5.481; p = 0.0082) were higher in the PVNS group than in the control group. Serum biochemical parameters, including white blood cell count (WBC), high/low-density lipoprotein (HDL/LDL), total cholesterol (TC), absolute monocyte count (MO#), and absolute lymphocyte count (LY#), were measured using an automated serum biochemical analyser.

Proteomics

Sample preparation and protein extraction: synovial fluid samples (40 μL each) were mixed with 250 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing a protease inhibitor (Roche, 4,693,132,001) to prevent protein degradation. Proteins were denatured by adding 250 μL of ST buffer (2% SDS, 100 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 7.6), followed by centrifugation at 8000 × g for 1 min. The supernatant was collected, boiled for 5 min, and sonicated to ensure complete protein solubilization. After a second centrifugation (8000 × g, 15 min), the supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Protein digestion and peptide preparation: proteins were reduced with 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT) at 56 °C for 1 h and alkylated with 20 mmol/L iodoacetamide (IAA) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The solution was buffer-exchanged into 50 mmol/L ammonium bicarbonate using a FASP column (PALL, OD010C34) and digested overnight with trypsin at 37 °C (enzyme-to-protein ratio, 1:50). The resulting peptides were quantified using a fluorometric peptide assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23,275).

High-pH Reverse Phase Fractionation: Equal amounts of peptides from all enzymatically digested samples were pooled and fractionated using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system with a mobile phase at pH 10. Separation was performed using an Agilent Zorbax Extend-C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 5 μm) with UV detection at 210 nm and 280 nm. The mobile phases consisted of the following: mobile phase A: ACN-H₂O (2:98, v/v); mobile phase B: ACN-H₂O (90:10, v/v); both mobile phases were adjusted to pH 10 with ammonium hydroxide.

The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–10 min: 2% B (isocratic); 10–10.01 min: 2–5% B; 10.01–37 min: 5–20% B (linear gradient); 37–48 min: 20–40% B (linear gradient); 48–48.01 min: 40–90% B; 48.01–58 min: 90% B (isocratic); 58–58.01 min: 90–2% B; 58.01–63 min: 2% B (re-equilibration). Fractions were collected at 1-min intervals starting from the 10th minute into 10 consecutive tubes (1 → 10 in a cyclic manner), vacuum freeze-dried, and stored at − 80 °C until mass spectrometry analysis.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS): prior to LC–MS/MS analysis, fractionated peptides were reconstituted and spiked with iRT peptides (1:10 ratio) as internal standards. Peptides were analyzed using a high-resolution mass spectrometer (Q Exactive HF-X, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following parameters: scan range: 350–1250 m/z; isolation window: 26 m/z; fragmentation: higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD); resolution: 60,000 (MS1), 15,000 (MS2).

Data processing and bioinformatics analysis: raw spectra were matched against a UniProt human protein database using Spectronaut Pulsar software (Biognosys). Data-independent acquisition (DIA) processing included retention time alignment, peak extraction, and library-based quantification. Missing values were imputed using the k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm, and proteins missing in > 50% of samples or with a coefficient of variation (CV) > 30% were excluded.

Differential protein expression was assessed using one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Multivariate analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), were performed to evaluate sample clustering and discriminatory features. Functional enrichment analysis was conducted using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Protein–protein interaction networks were constructed using STRING (v11.5) and visualized in Cytoscape (v3.9.1).

Metabolomics

Fifty microliters of synovial fluid from each sample were mixed with 250 μL of isotope-labeled methanol, vortexed, and incubated at − 20 °C for 20 min. After ultrasonic extraction on ice for 15 min, samples were centrifuged at 13,300 rpm (4 °C, 15 min). The supernatant (200 μL) was collected, vacuum-dried at 30 °C for 2 h, and reconstituted in 0.1 mL of HILIC reconstitution solution. Following sonication, vortexing, and centrifugation, 80 μL of the supernatant was transferred to an LC–MS vial for analysis using an ACQUITY UPLC system coupled to an AB TripleTOF 5600 high-resolution mass spectrometer. For quality control (QC), 20 μL of supernatant from each sample was pooled, aliquoted, and analyzed alongside experimental samples.

Raw data were processed using Progenesis QI (Waters) for peak alignment, annotation, and filtering (retention score ≥ 35, intensity > 1000). After median normalization and missing value imputation (KNN algorithm), PCA assessed data quality. Differential metabolites were identified by t-test (p < 0.05) and OPLS-DA (variable importance in projection (VIP) ≥ 1). Pathway analysis was performed via MetaboAnalyst 4.0 using the KEGG database.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

A total of 376 proteins and 20 samples were analyzed. Proteins with low expression variability (standard deviation ≤ 0.5) were filtered out, leaving 208 proteins and 20 samples for further analysis. A weighted co-expression network model was constructed using a power value of 22, and the remaining 208 proteins were divided into three modules. Data analysis and visualization were performed using the WGCNA package in R, and data visualization was performed using R and Python. The Pearson correlation algorithm calculates the correlation coefficient and p-value between module characteristic proteins and traits. Modules with an absolute correlation coefficient ≥ 0.3 and a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant. For each considerable module, the correlation between module gene expression and trait gene significance (GS) was calculated, and the correlation between module gene expression and Eigengene was analyzed to construct a module-trait correlation analysis.

Integrated omics analysis

Orthogonal partial least squares (O2PLS) analysis was employed to integrate the proteomics data and metabolomics data. O2PLS is a multivariate data integration technique that decomposes the variation in two datasets into joint, dataset-specific, and noise components, enabling the identification of correlations between the datasets while accounting for their intrinsic structure [61].

Prior to analysis, the data were centered around zero and scaled. To determine the optimal number of components, cross-validation was performed using the “crossval_o2m_adjR2()” function, which adjusts for cross-validation in O2PLS analysis. This process yielded values for “n” (number of joint components), “nx” (number of transcriptome-specific components), and “ny” (number of metabolite-specific components). In this study, “n = 3,” “nx = 0,” and “ny = 1” were selected to best fit the omics data to the O2PLS model.

In the O2PLS model, the joint components capture the covariance between the proteins and metabolite data, while the dataset-specific components capture the variation unique to each dataset. The loading values for each variable (gene or metabolite) on the joint components indicate their relative importance in determining the joint variation. Variables with high loading values on the same joint component are strongly correlated. Therefore, by examining the variables with high loading values on the joint components, it is possible to identify groups of proteins and metabolites that are related, potentially reflecting underlying biological processes or pathways.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay

Synovial tissue and synovial fluid samples were retrieved from − 80 °C storage. Synovial tissue was homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors). After homogenization or lysis, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, P0009). Reaction setup: blank: 0.1 mL of homogenization buffer, lysis buffer, or PBS. Standard curve: 0.1 mL of serial dilutions of MDA standard (provided in the kit). Samples: 0.1 mL of tissue or synovial fluid supernatant. To each tube, 0.2 mL of MDA detection working solution (Beyotime, S0131S) was added. Samples were mixed thoroughly and heated at 100 °C for 15 min using one of the following methods: Post-incubation processing: samples were cooled to room temperature and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. Two hundred microliters of supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at 532 nm using a microplate reader. A reference wavelength of 450 nm was used for dual-wavelength correction. Quantification: For synovial fluid, MDA concentration (μM) was calculated directly from the standard curve. For tissue samples, MDA content was normalized to total protein (μmol/mg protein). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate (n = 3).

Western blot

Western blotting was performed as described previously [25]. Briefly, synovial samples were lysed and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 25 min at four °C, and the supernatant was collected as the tissue protein solution. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA kit. The primary antibodies used were TNFSF11 (1:1000, ABcloal, A2550); CTSK (1:500, ABcloal, A5871); ADGRE5 (1:2000, ABcloal, A22218); NF-κB (1:1000, ABcloal, A2547); and β-Tubulin (1:1000, ABcloal, AC008). Immunoblots were visualized using BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime, Beijing, China), and protein bands were photographed and stored using the Tanon 2500R gel imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ 1.39 V software (n = 3).

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was employed. For multiple group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For proteomic and metabolomic differential expression analyses, all statistical computations were performed in R (version 4.41). Differential expression was conducted using the limma package (or other applicable packages), and raw p-values were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Features with FDR-adjusted p < 0.05 and absolute fold change ≥ 2 were considered significantly altered.

Multivariate statistical analyses, including PCA and O2PLS, were performed using the mixOmics R package. In the O2PLS modeling, variables with VIP scores > 1.0 were considered key contributors to group separation. All data visualization and preprocessing steps were conducted in R using standard packages such as ggplot2 and pheatmap.

Results

Differential protein expression analysis

PCA was performed based on normalized protein expression data. The first three principal components explained approximately 60% of the total variance (PC1: 38.3%, PC2: 12.4%, PC3: 6.93%). Despite the moderate cumulative variance, clear separation between sample groups was observed, indicating distinct proteomic profiles (Fig. 1C). PCA highlighted the spatial distribution of samples within the same group. Sample correlation analysis of reliable proteins showed that the grouping and reproducibility of samples met the required standards (Fig. 1D). In the PVNS group, 156 DEPs were identified compared to the Control group, with 70 proteins upregulated and 86 downregulated (Fig. 1E, Additional file 2: Table S1.). The volcano plot directly visualized the significant differences in protein expression between the PVNS and Control groups (Fig. 1F). A hierarchical clustering heatmap demonstrated the consistency of changes in DEPs between the groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

GO/KEGG enrichment analysis of differential proteins to characterize their functions

To gain deeper insights into the biological functions of DEPs, GO enrichment analysis was performed, covering biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions (Fig. 2A). DEPs were significantly associated with GO terms related to the inflammatory response, pattern recognition receptors on the cell surface, and proteolysis involved in protein catabolic processes, suggesting a close connection between inflammation and metabolic processes in PVNS. Additionally, metabolic profiling of synovial fluid identified changes in related metabolites and their relationship with proteins. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis further clarified the association of DEPs in PVNS joint synovial fluid, with significant enrichment in the “Osteoclast differentiation” and “NF-κB signalling pathway” (Fig. 2B). Among the upregulated differential proteins are: TNFSF11, CD14, Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (LBP), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (VCAM1), and BLNK. Wikipathways enrichment analysis also indicated significant pathways such as “Osteoclast signalling” and “NF-κB survival signalling” (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). PPI analysis of upregulated DEPs revealed substantial correlations among TNFSF11, CTSK, and ADGRE5. The upregulated differential proteins included are: TNFSF11, which is involved in the transformation of monocytes into osteoclasts and is an important pathway for bone destruction; LBP activates the NF-κB/ Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway through Toll like receptor 4 (TLR4), thereby inducing inflammatory factors and TNFSF11. The VCAM1 adhesion molecule promotes the infiltration of immune cells (such as monocytes) into the synovial tissue, thereby amplifying the inflammatory response. BLNK is mainly expressed in B cells and serves as a crucial bridge in the signal transduction of B cell receptors, regulating the activation of inflammatory cells. ADGRE5 is located at the intersection of inflammation initiation, immune regulation, and osteoclast activation. It can be regarded as a core “hub molecule” and forms a signaling axis amplifying inflammation and bone destruction together with TNFSF11, CD14/LBP, and VCAM1. It is a potential therapeutic target (Fig. 2C, Additional file 1: Fig. S3A, B, Fig. S4). NF-κB is one of the most core transcription factors in inflammation and immune regulation. It has a close upstream–downstream relationship with ADGRE5, TNFSF11, CD14, LBP, VCAM1, BLNK, and GPCR, forming an interconnected inflammatory-immune-bone destruction network. It is particularly important in joint diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and PVNS. Enrichment and protein interaction network analyses indicated a close relationship between the NF-κB signaling pathway and ADGRE5 in macrophage differentiation.

Fig. 2.

Gene Ontology/Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (GO/KEGG) enrichment analysis of differential proteins to characterize their function. A GO enrichment analysis of elevated expression top 30 (screening of 10 GO entries corresponding to the number of proteins more significant than 1 in each of the three classifications, sorted by the -log10Pvalue of each entry in descending order), where the x-coordinate is the name of the GO entry and the y-coordinate is the -log10Pvalue. B Comparison of differentially expressed proteins and all proteins at the KEGG Level 2 level. Distribution comparison graph. The horizontal axis is the ratio (%) of proteins annotated to each Level 2 metabolic pathway (differential proteins) to the total number of all proteins annotated to the KEGG pathway (differential proteins), the vertical axis indicates the name of the Level 2 pathway, and the number to the right of the column represents the number of differentially expressed proteins annotated to that Level 2 pathway. C Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) protein interaction network, select this species/related species (blast e-value: 1e − 10) in the STRING database to analyze the differential proteins and obtain the interaction relationship of the differential proteins

Gene co-expression network analysis to explore the relationship between gene modules and disease phenotypes

A weighted co-expression network model was constructed based on selected efficacy values, resulting in 376 proteins divided into two modules (Fig. 3A). The clustering heatmap of all proteins and the protein lists associated with each WGCNA module revealed that proteins in the blue module were positively correlated with phenotypes such as ESR, WBC, and CRP (Fig. 3B, C). Analysis of the blue module’s gene expression showed increased expression in the PVNS group, while the control group’s blue gene module was significantly decreased (Fig. 3D). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the DEPs revealed that the blue module’s characteristic proteins were mainly enriched in “Osteoclast differentiation” (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), which was positively correlated with clinical phenotypes in PVNS patients, including elevated CRP, ESR, and WBC levels. The core gene analysis of the module examined the top 50 proteins with the highest connectivity in the blue module, illustrating the relationships between these proteins. It also shows a close connection between TNFSF11, CTSK, and ADGRE5 (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). This suggests that changes in osteoclast differentiation-related regulatory proteins contribute to disease progression in PVNS.

Fig. 3.

Gene co-expression network analysis looks for co-expressed gene modules and explores the association between gene networks and disease phenotypes. A Heat map of all gene clustering. Based on the selected power values, a weighted co-expression network model was finally built to classify the 208 genes into three modules. B Trait module association heat map (absolute value of correlation coefficient greater than or equal to 0.3 and p-value less than 0.05 is the threshold to filter the modules associated with each trait). C Based on the weighted gene co-expression network analysis module classification results, clustered heatmaps were used to display the expression information of genes within each module. D Blue module characteristic gene histogram

Metabolomic analysis of synovial fluid in PVNS and control groups

In the quality control (QC) assessment of the metabolomics data, 90% of the metabolites in QC samples exhibited a coefficient of variation (CV) below 20%, indicating good analytical reproducibility (Fig. 4A). The PLS-DA model demonstrated good predictive ability for differences between the two groups (Fig. 4B). A volcano plot visualized the differential metabolites across all samples (Fig. 4C). Using VIP values more significant than one and a significance threshold of P < 0.05, 62 differential metabolites were identified (Additional file 2: Table S2.). Hierarchical clustering based on VIP values visualized the relationship between PVNS and control groups and the differential expression of metabolites among samples (Fig. 4D). KEGG enrichment analysis of differential metabolites indicated significant enrichment in pathways such as “Linoleic acid metabolism” and “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” (Fig. 4E). The differentially upregulated metabolites in these two signaling pathways are: C06427 (alpha-Linolenic acid), C03242 (Dihomo-gamma-linolenate), C16525 (Icosadienoic acid), C04717 (13(S)-HPODE), and C14765 (13-OxoODE). The above linoleic acid-derived metabolites—including alpha-Linolenic acid, 13(S)-HPODE, 9(S)-HpODE, 13-OxoODE, and 9/13-HODE—are classified as oxidized lipid mediators generated through lipoxygenase (LOX)-mediated pathways. These molecules play key roles in regulating inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular signaling. In PVNS, they may contribute to disease progression by activating macrophages and enhancing inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB, thereby promoting synovial hyperplasia and aggressive local inflammation. Changes in lipid metabolites are identified as significant alterations in PVNS, contributing to accelerated disease progression and promoting monocyte differentiation into osteoclasts, leading to joint damage at the disease site.

Fig. 4.

Metabolomic analysis of synovial fluid in the knee joint of patients with pigmented villonodular synovitis and control group. A Distribution of the coefficient of variation in QC samples. A total of 90% of metabolites showed a CV less than 20%, indicating high analytical reproducibility in the metabolomics dataset. B Partial least squares-discriminant analysis PLS-DA is a supervised discriminant statistical method. C A volcanic map can be used to visualize the p value and fold change value. The red origin represents the significantly up-regulated differential metabolites in the experimental group, the blue origin represents the significantly down-regulated differential metabolites, and the gray point represents the insignificant differential metabolites. D Differential metabolite heat map, visualization of differential metabolite expression based on VIP values (horizontal coordinates indicate sample names, vertical coordinates indicate differential metabolites.). E Bubble plots showing the enrichment of differentially altered pathways

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis was used to identify co-expressed metabolite modules and explore the association between metabolite networks and disease phenotypes

A weighted co-expression network model was constructed based on the selected efficacy values, and 54 metabolites were divided into two modules (Fig. 5A). The clustering heatmap of all metabolites and the list of metabolites related to each WGCNA module showed that the metabolites in the turquoise module were positively correlated with phenotypes such as ESR, WBC, and CRP (Fig. 5B, C). The gene expression analysis of the blue module showed that the expression in the PVNS group increased, while the blue gene module in the control group significantly decreased (Fig. 5D). The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the differential metabolites showed that the characteristic proteins of the turquoise module were mainly enriched in “Linoleic acid metabolism” and “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” (Additional file 1: Fig. S7), which was positively correlated with the clinical phenotypes of PVNS patients, including elevated CRP, ESR, and WBC levels. The core metabolite analysis of this module examined the top 50 most connected metabolites in the blue module, illustrating the relationships between these metabolites. It also showed that changes in 13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid and 13-OxoODE joint metabolites contributed to the disease progression of PVNS (Additional file 1: Fig. S8). Therefore, these oxidized lipid mediators not only drive local inflammation in PVNS but may also correlate positively with systemic inflammatory indicators such as CRP, ESR, and WBC, reflecting the extent of immune activation and disease severity.

Fig. 5.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was used to identify co-expressed metabolite modules and explore the association between metabolite networks and disease phenotypes. A Clustering heatmap of all metabolites. Based on the selected power value, a weighted co-expression network model was constructed, classifying 54 differential metabolites into two modules. B Heatmap of trait-module associations (modules with an absolute correlation coefficient ≥ 0.3 and p-value < 0.05 were considered significantly associated with clinical traits). C Clustered heatmaps showing the expression profiles of metabolites within each module, based on the WGCNA classification. D Bar plot of the characteristic metabolites in the turquoise module

Interaction between proteomics and metabolomics

O2PLS loadings from metabolomic analysis showed a significant correlation between two differential metabolites (13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid, 13-OxoODE) and proteins involved in the “Linoleic acid metabolism” pathway (Fig. 6A). O2PLS loadings from the proteomic analysis indicated a strong correlation between proteins (TNFSF11, CTSK, ADGRE5) involved in the “Osteoclast differentiation” pathway (Fig. 6B). The top 30 loading elements indicated a high correlation between metabolomics and proteomics in the third quadrant, showing that 13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid, 13-OxoODE, and TNFSF11, CTSK, ADGRE5 were strongly positively correlated (Fig. 6C). Thus, metabolites related to “Linoleic acid metabolism” impact macrophage differentiation into osteoclasts, suggesting further exploration of related differential proteins for validation.

Fig. 6.

Two-way orthogonal partial least squares (O2PLS) analysis explores the relationship between proteomics and metabolomics. A O2PLS loading plot for proteomics. B O2PLS loading plot for metabolomics. C The correlation loading plot for proteomics and metabolomics indicates the strength of the association between the two omics, with the absolute value of the loading representing the strength of the correlation. A more significant absolute value suggests a stronger association between the differential protein and the differential metabolite

Validation of proteins and oxidized substances involved in macrophage differentiation into osteoclasts

Metabolomics revealed significant differences in lipid metabolites (13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid, 13-OxoODE) among differential metabolites (Fig. 7A, Additional file 1: Fig. S9). Synovial tissue validation experiments confirmed increased MDA content in PVNS compared to the control group (Fig. 7B). Western blot analysis of TNFSF11, CTSK, ADGRE5, and NF-κB showed significantly higher protein expression in the PVNS group compared to the control group (Fig. 7C, D). Synovial fluid MDA content was consistent with metabolomic and synovial tissue results, with significantly higher levels in the PVNS group than in the control group (Additional file 1: Fig. S10). The increased oxidized lipid substances activate GPCR, further regulating TNFSF11 and CTSK, exacerbating synovial cartilage damage. This validation provides clues to the pathological process of PVNS.

Fig. 7.

Validation of synovial lipid peroxidation and key proteins in related pathways. A Expression of 13-OxoODE in joint fluid in each group (n = 10). B The concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) in each group’s synovial membrane (n = 3 per group). Comparison between PVNS and control group. C The expressions of Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily Member 11 (TNFSF11), Cathepsin K (CTSK), adhesion G protein-coupled receptor E5 (ADGRE5), and Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) were evaluated by western blotting. D Quantification of TNFSF11, CTSK, ADGRE5, and NF-κB expressions (n = 4, all the data are expressed as means ± SD, two-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s post hoc test was applied)

Discussion

PVNS is an aggressive soft tissue tumor that is considered benign in terms of cellular proliferation. Despite the clinical and radiological differences, both forms of PVNS share similar histological characteristics, including histiocytic proliferation and hemosiderin deposition within the synovium [26]. The localized form typically manifests as a distinct intra-synovial mass, which can be locally invasive and tends to recur locally [27]. In contrast, the diffuse form of PVNS, which involves the entire synovium intra-articularly or extra-articularly, can gradually progress from a focal disease to a diffuse one, affecting bones, muscles, and tendons, leading to arthritis. The diffuse form is more aggressive and recurrent, often resulting in severe, widespread joint disease and deformity despite treatment attempts. Recurrence may present as repeated effusion, hemarthrosis, joint dissolution, the emergence of new palpable masses, or worsening pain with limited range of motion [11, 12, 28]. Previous studies have focused on the persistent proliferation of the synovium, with less emphasis on the analysis of synovial fluid [29]. In clinical practice, synovial fluid can be collected quickly and minimally invasively, providing a valuable adjunct for diagnosing patients [30, 31].

In this study, we performed high-throughput synovial fluid analysis from PVNS patients, including proteomics and metabolomics. A total of 156 DEPs and 62 differential metabolites were identified. Enrichment analysis revealed that “Osteoclast differentiation signalling” and “NF-κB survival signalling” play significant roles in PVNS progression, with notable increases in the expression of TNFSF11, CTSK, ADGRE5, and NF-κB in the lesional tissues of PVNS patients. By correlating these findings with patients’ clinical manifestations, WGCNA analysis showed that CRP, ESR, and WBC were positively correlated with the gene modules characterized by the blue module. Further analysis of the blue module proteins indicated an association with “Osteoclast differentiation signalling.” Darling et al. suggested that the pathogenic mechanism of PVNS-induced joint destruction might be mediated by proteolytic enzymes, mainly MMP-1 and MMP-3, expressed in synovial lining cells, with MMP-2 and MMP-9 expressed in synovial tissues undergoing progressive cartilage and bone destruction. The differentiation of osteoclasts leads to the secretion and activation of proteases, contributing to proteolytic activity within the lesional tissue[32, 33]. PPI analysis revealed strong interactions among TNFSF11, CTSK, and ADGRE5. Previous reports have indicated that NF-κB activation leads to cartilage destruction, but the initial regulatory mechanisms remain unclear[34, 35]. In this study, we screened and validated CRP, finding that ADGRE5 is closely related to NF-κB, TNFSF11, and CTSK. The role of ADGRE5 in cellular metabolism may complement its previously established role in cellular migration. ADGRE5 likely functions similarly in activated immune cells and cancer cells, both of which tend to glycolytic metabolism and exhibit enhanced migratory and proliferative capabilities. Our integrative analysis revealed significant alterations in the linoleic acid metabolism pathway in the synovial fluid of PVNS patients. Linoleic acid, an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and its oxidized derivatives (such as 9-HODE and 13-HODE) are known to modulate immune responses and cellular signaling. Recent studies have demonstrated that these metabolites can influence macrophage polarization and osteoclast differentiation—two key processes in PVNS pathogenesis [36–38].

We also conducted metabolomic analysis, identifying the “Linoleic acid metabolism” and “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” pathways as significantly enhanced in PVNS samples, with differential metabolites such as 13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid and 13-OxoODE showing markedly increased expression. In PVNS, a locally aggressive inflammatory joint disease characterized by synovial hyperplasia and macrophage infiltration, linoleic acid-derived oxidized metabolites play critical roles in disease progression. These metabolites, generated through the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway, can activate key inflammatory signaling cascades including NF-κB, leading to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. The resulting inflammatory response promotes systemic acute-phase reactions, contributing to elevated clinical inflammatory markers. Specifically, IL-6 stimulates hepatic CRP synthesis, while widespread immune activation leads to increased ESR and WBC counts. The proliferation and differentiation at the disease site were further analyzed using O2PLS analysis, revealing close relationships among ADGRE5, TNFSF11, CTSK, 13-L-Hydroperoxylinoleic acid, and 13-OxoODE. We then performed Western blot validation, which confirmed significantly higher expression of ADGRE5, TNFSF11, CTSK, and NF-κB in the PVNS group compared to the control group. Additionally, MDA content in human synovial tissue was significantly higher in the PVNS group than in the control group. These findings suggest that enhanced energy metabolism leads to increased lipid oxidation, which further regulates the increased expression of ADGRE5 and NF-κB, exacerbating osteoclast differentiation, as evidenced by the enhanced expression of TNFSF11 and CTSK. Specifically, linoleic acid-derived oxylipins can promote M1-type macrophage polarization by activating NF-κB signaling pathways, thereby enhancing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. In the PVNS microenvironment, this polarization shift likely contributes to persistent synovial inflammation and tissue remodeling. In addition, these oxidized lipids have been implicated in promoting osteoclastogenesis through the TNFSF11/nuclear factor of activated T cell (NFATc1) axis and by activating MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathways, thereby enhancing bone-resorptive activity [39, 40].

In our O2PLS analysis, linoleic acid levels were positively correlated with the expression of osteoclast-related proteins such as CTSK, ACP5, suggesting a coordinated regulatory network between metabolism and bone degradation. This highlights a potential mechanism whereby metabolic reprogramming promotes both immune cell activation and bone erosion in PVNS. These findings support a model in which altered lipid metabolism contributes to disease progression through immunometabolic regulation. To further confirm this mechanism, functional assays—such as evaluating the effects of linoleic acid or its metabolites on macrophage phenotype and osteoclast differentiation in vitro—will be necessary, which may also provide a foundation for developing metabolism-targeted therapies in PVNS.

Although both PVNS and RA involve synovial inflammation and osteoclast-mediated bone destruction, their underlying mechanisms differ significantly. RA primarily relies on systemic immune activation and RANKL-driven osteoclastogenesis, whereas PVNS presents as a localized, tumor-like synovial proliferation enriched with macrophage-lineage cells [41, 42]. Cadherin-11, GRK2, and GPR4 are key pathogenic mediators in joint diseases, all converging on the NF-κB signaling pathway to drive inflammation and tissue remodeling. Cadherin-11 promotes PVNS progression through enhanced inflammatory responses, GRK2 regulates synovial inflammation and FLS proliferation in RA via the GRK2-TRAF2-TRIM47-NF-κB axis, and GPR4 facilitates cartilage degradation and synovial hyperplasia in osteoarthritis. Together, these molecules illustrate how dysregulated NF-κB signaling underlies diverse joint pathologies and highlight potential therapeutic targets across multiple arthritic conditions [13, 43, 44]. In our study, the ADGRE5–NF-κB axis emerged as a distinct pathway associated with osteoclast activation in PVNS, potentially independent of classical RANKL signaling. ADGRE5, a macrophage-specific adhesion GPCR rarely implicated in RA, was significantly upregulated in PVNS synovial fluid, along with enhanced metabolic activity. These findings suggest a PVNS-specific mechanism, whereby metabolic reprogramming and macrophage activation jointly drive osteoclast differentiation and joint destruction, underscoring the therapeutic relevance of targeting this axis in PVNS.

ADGRE5 has emerged as a potential therapeutic target in PVNS; however, its dual role in the tumor microenvironment warrants caution. In various cancers, ADGRE5 has been associated with both pro-inflammatory activity and immune suppression, depending on cellular context [45, 46]. In PVNS, our data suggest it contributes to macrophage activation and osteoclast differentiation, promoting local tissue destruction. Given the neoplastic features of PVNS, the complexity of ADGRE5 signaling must be carefully considered. Further studies using in vivo models are necessary to clarify its functional role and assess the safety and specificity of ADGRE5-targeted therapies.

Due to the lack of a suitable animal model, in vivo validation remains a challenge. However, we plan to use genetic or pharmacological modulation of ADGRE5 and NF-κB in mouse models to assess their effects on immune activation and bone destruction. Given the central role of ADGRE5 in PVNS pathogenesis, its therapeutic potential warrants consideration. Although no ADGRE5 inhibitors are currently approved, recent oncology studies have explored antibody-based and small-molecule strategies targeting ADGRE5, particularly in macrophage-enriched tumors such as glioblastoma and colorectal cancer [47, 48]. These preclinical efforts support the feasibility of ADGRE5-targeted therapy and provide a conceptual basis for its application in PVNS [49]. However, further validation in disease-relevant models is needed to assess efficacy and safety in this specific context.

Therefore, we conducted an integrated analysis of proteomics and metabolomics to refine the selection of biomarkers. A series of candidate molecular markers were subsequently validated by western blotting, among which TNFSF11, CTSK, ADGRE5, and NF-κB showed significant differences. Based on these results, we selected the ADGRE5 and NF-κB pathways as potential molecular targets for future investigation.

This study has several limitations that warrant further consideration. First, although ADGRE5 and NF-κB were identified as potential key regulators in PVNS through integrated proteomic and metabolomic analyses, the validation was limited to protein expression in patient-derived samples, and the specific regulatory mechanisms and cellular interactions remain to be elucidated. Second, the precise cell types expressing ADGRE5—such as FLS or immune cell subsets—have not yet been clearly defined, which is critical for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. Third, the relatively small sample size (10 subjects per group), due to the rarity of PVNS and the difficulty of obtaining high-quality synovial fluid, may limit statistical power and increase the risk of overfitting in high-dimensional analyses such as metabolomics and WGCNA. Nonetheless, we minimized this risk by applying rigorous quality control, using stringent thresholds (e.g., fold change, VIP > 1.0, FDR-adjusted p < 0.05), and validating key findings through Western blotting. While formal power analysis is not directly applicable to unsupervised methods, post hoc evaluations suggest that the observed differences are biologically meaningful. Future studies with larger cohorts and advanced approaches such as single-cell RNA sequencing will be essential to validate our findings and further dissect the cellular and molecular mechanisms of PVNS.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that PVNS lesions are in a hypermetabolic, high-energy state involving FLS and immune cells, with altered metabolism linked to ADGRE5 and NF-κB signaling. This may drive osteoclast differentiation and joint destruction. Targeting these pathways could offer a promising strategy for therapeutic intervention in PVNS.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figures S1–S10. Fig S1 Heat map of cluster analysis of differential protein expression. Fig S2 Wikipathways Enrichment Analysis Top 20 Bar Plot. Fig. S3 TNFSF11 and CTSK expression in joint fluid of each group. Fig. S4 Expression of ADGRE5 in joint fluid in each group. Fig S5 KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in the blue module top20 (upregulated differences) bubble plots. Fig S6 The lines in the network diagram of represent the degree of connection between genes. Fig S7 KEGG enrichment analysis of characteristic metabolites in the turquoise module top20 bubble plots. Fig S8 The lines in the network diagram represent the degree of connection between metabolites. Fig S9 Expression of 7 13(S)-HPODE in joint fluid in each group.Fig S10 The concentration of MDA in each group's synovial fluidFig S10 The concentration of MDA in each group's synovial fluidFig S10 The concentration of MDA in each group's synovial fluid.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Original data of differentially expressed proteins after filtering. Table S2. Original data of differentially expressed metabolites after filtering.

Additional file 3: Original images of all western blots analyzed in the present study.

Acknowledgements

Thank Ge Liang, Lu Zhang, Yi Zhong and Wen Zheng (Metabolomics and Proteomics Technology Platform, West China Hospital, Sichuan University) for relative data acquisition and analysis.

Abbreviations

- PVNS

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

- TGCT

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor

- DEPs

Differentially expressed proteins

- O2PLS

Two-way orthogonal partial least squares

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-κB

- TNFSF11

Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily Member 11

- CTSK

Cathepsin K

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- FLSs

Fibroblast-like synoviocytes

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- IL-1

Interleukin-1

- VIP

Variable importance in projection

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- ADGRE5

Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor E5

- aGPCRs

Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors

- AGPCRs

Adhesion G protein-coupled

- BMI

Body mass index

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- TG

Triglycerides

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation Rate

- WBC

White blood cell

- HDL/LDL

High/low-density lipoprotein

- TC

Total cholesterol

- MO#

Monocyte count

- LY#

Lymphocyte count

- QC

Quality control

- CV

Coefficient of variation

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- BCA

Bicinchoninic acid

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- WGCNA

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

- GS

Gene significance

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

Authors’ contribution

WF, MG1 and BX collected the samples. WF and MG2 supervised the study and critically revised the manuscript. MG1 and LF analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the PVNS. GM1, MX and TX conducted verification experiments. MG1 and RY were a major contributor to writing the manuscript. WF, MG2 and JL conceived the project. YL participated in the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172508, 82372490); the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFJQ0041); the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence of West China Hospital Sichuan University (ZYJC21030).

Data availability

Proteomics data were deposited into the ProteomeXchange Consortium under accession number PXD067331 and are available at the following URL: https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD067331. Metabolomics data from this study were deposited into the MetaboLights repository under accession number MTBLS12866 and are available at the following URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS12866.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research at West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. 125 2020-(921)). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their involvement in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Minghao Ge, Runze Yang and Baojun Xu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yusheng Li, Email: liyusheng@csu.edu.cn.

Meng Gong, Email: gongmeng@scu.edu.cn.

Weili Fu, Email: foxwin2008@163.com.

References

- 1.Staals EL, Ferrari S, Donati DM, Palmerini E. Diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumour: current treatment concepts and future perspectives. Eur J Cancer. 2016;63:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin BP. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor and pigmented villonodular synovitis: a proposal for unification of these clinically distinct but histologically and genetically identical lesions. Skelet Radiol. 2007;36:267–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li T, Xiong Y, Li J, Tang X, Zhong Y, Tang Z, et al. Mapping and analysis of protein and gene profile identification of the important role of transforming growth factor beta in synovial invasion in patients with pigmented villonodular synovitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024. 10.1002/art.42946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cupp JS, Miller MA, Montgomery KD, Nielsen TO, O’Connell JX, Huntsman D, et al. Translocation and expression of CSF1 in pigmented villonodular synovitis, tenosynovial giant cell tumor, rheumatoid arthritis and other reactive synovitides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:970–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiocco U, Sfriso P, Lunardi F, Pagnin E, Oliviero F, Scagliori E, et al. Molecular pathways involved in synovial cell inflammation and tumoral proliferation in diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:780–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuß M, Hermanns B, Wirtz D. Rezidiv einer pigmentierten villo-nodulären Synovialitis (PVNS). Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2001;139:366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rovner J, Yaghoobian A, Gott M, Tindel N. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the zygoapophyseal joint: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:E656-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gounder MM, Thomas DM, Tap WD. Locally aggressive connective tissue tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernthal NM, Ishmael CR, Burke ZDC. Management of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS): an orthopedic surgeon’s perspective. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colman MW, Ye J, Weiss KR, Goodman MA, McGough RL. Does combined open and arthroscopic synovectomy for diffuse PVNS of the knee improve recurrence rates? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:883–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mollon B, Lee A, Busse JW, Griffin AM, Ferguson PC, Wunder JS, et al. The effect of surgical synovectomy and radiotherapy on the rate of recurrence of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee: an individual patient meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B:550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aurégan J-C, Klouche S, Bohu Y, Lefèvre N, Herman S, Hardy P. Treatment of Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis of the Knee. Arthroscopy: J Arthro Rel Surg. 2014;30:1327–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao C, Wu F, Niu X, Hu X, Cheng J, Zhang Y, et al. Cadherin-11 cooperates with inflammatory factors to promote the migration and invasion of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in pigmented villonodular synovitis. Theranostics. 2020;10:10573–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Lv J, Zhang H, Xie J, Dai H, Zhang X. Gene expression profiles analyzed using integrating RNA sequencing, and microarray reveals increased inflammatory response, proliferation, and osteoclastogenesis in pigmented villonodular synovitis. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 665442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West RB, Rubin BP, Miller MA, Subramanian S, Kaygusuz G, Montgomery K, et al. A landscape effect in tenosynovial giant-cell tumor from activation of CSF1 expression by a translocation in a minority of tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:690–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Németh T, Nagy G, Pap T. Synovial fibroblasts as potential drug targets in rheumatoid arthritis, where do we stand and where shall we go? Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:1055–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abed Alharbi W, Mohammed Alshareef H, Hennawi YB, Munshi AA, Khalid AA. Giant cell tumor in tarsal midfoot bones: a case report. Cureus. 2024;16: e56215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23:27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavlova NN, Zhu J, Thompson CB. The hallmarks of cancer metabolism: still emerging. Cell Metab. 2022;34:355–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muñoz-Pinedo C, El Mjiyad N, Ricci J-E. Cancer metabolism: current perspectives and future directions. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3: e248–e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson B, Bitensky L, Johnstone JJ, Catterall A, Chayen J. Metabolic alterations in human synovial lining cells in pigmented villonodular synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979;38:463–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan J, Han VX, Jones HF, Couttas TA, Jieu B, Leweke FM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid metabolomics in autistic regression reveals dysregulation of sphingolipids and decreased β-hydroxybutyrate. EBioMedicine. 2025;114: 105664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Li R, Qiu Z, Zhu K, Li R, Zhao S, et al. Prediction of Weight Loss and Regain Based on Multiomic and Phenotypic Features: Results From a Calorie-Restricted Feeding Trial. Diabetes Care. 2025;dc250728. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Miglino N, Toussaint NC, Ring A, Bonilla X, Tusup M, Gosztonyi B, et al. Feasibility of multiomics tumor profiling for guiding treatment of melanoma. Nat Med. 2025. 10.1038/s41591-025-03715-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge M-H, Tian H, Mao L, Li D-Y, Lin J-Q, Hu H-S, et al. Zinc attenuates ferroptosis and promotes functional recovery in contusion spinal cord injury by activating Nrf2/GPX4 defense pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27:1023–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao L, Li Y, Li T, Fu W, Chen G, Li Q, et al. What are the recurrence rates, complications, and functional outcomes after multiportal arthroscopic synovectomy for patients with knee diffuse-type tenosynovial giant-cell tumors? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2024;482:1218–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernthal NM, Healey JH, Palmerini E, Bauer S, Schreuder H, Leithner A, et al. A prospective real-world study of the diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumor patient journey: a 2-year observational analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2022;126:1520–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ijiri K, Tsuruga H, Sakakima H, Tomita K, Taniguchi N, Shimoonoda K, et al. Increased expression of humanin peptide in diffuse-type pigmented villonodular synovitis: implication of its mitochondrial abnormality. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang JS, Higgins JP, Kosy JD, Theodoropoulos J. Systematic arthroscopic treatment of diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis in the knee. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e1547-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swan A, Amer H, Dieppe P. The value of synovial fluid assays in the diagnosis of joint disease: a literature survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:493–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahendran SM, Oikonomopoulou K, Diamandis EP, Chandran V. Synovial fluid proteomics in the pursuit of arthritis mediators: an evolving field of novel biomarker discovery. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darling JM, Glimcher LH, Shortkroff S, Albano B, Gravallese EM. Expression of metalloproteinases in pigmented villonodular synovitis. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:825–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uchibori M, Nishida Y, Tabata I, Sugiura H, Nakashima H, Yamada Y, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in pigmented villonodular synovitis suggests their potential role for joint destruction. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:110–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou F, Mei J, Han X, Li H, Yang S, Wang M, et al. Kinsenoside attenuates osteoarthritis by repolarizing macrophages through inactivating NF-κB/MAPK signaling and protecting chondrocytes. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:973–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuang L, Wu J, Su N, Qi H, Chen H, Zhou S, et al. Fgfr3 deficiency enhances CXCL12-dependent chemotaxis of macrophages via upregulating CXCR7 and aggravates joint destruction in mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shan M, Zhang S, Luo Z, Deng S, Ran L, Zhou Q, et al. Itaconate promotes inflammatory responses in tissue-resident alveolar macrophages and exacerbates acute lung injury. Cell Metab. 2025;S1550–4131(25):00268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rong K, Wang D, Pu X, Zhang C, Zhang P, Cao X, et al. Inflammatory macrophage-derived itaconate inhibits DNA demethylase TET2 to prevent excessive osteoclast activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Bone Res. 2025;13: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kachler K, Andreev D, Thapa S, Royzman D, Gießl A, Karuppusamy S, et al. Acod1-mediated inhibition of aerobic glycolysis suppresses osteoclast differentiation and attenuates bone erosion in arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:1691–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abshirini M, Ilesanmi-Oyelere BL, Kruger MC. Potential modulatory mechanisms of action by long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on bone cell and chondrocyte metabolism. Prog Lipid Res. 2021;83: 101113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.You Y, Huo K, He L, Wang T, Zhao L, Li R, et al. GnIH secreted by green light exposure, regulates bone mass through the activation of Gpr147. Bone Res. 2025;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lesturgie-Talarek M, Gonzalez V, Beaudoin L, Sénot N, Miceli-Richard C, Allanore Y, et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025. 10.1002/art.43242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray S, McCall JL, Tian JB, Jeon J, Douglas A, Tyler K, et al. Targeting TRPC channels for control of arthritis-induced bone erosion. Sci Adv. 2025;11: eabm9843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han C, Jiang L, Wang W, Zuo S, Gu J, Chen L, et al. GRK2 activates TRAF2-NF-κB signalling to promote hyperproliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2025;15:1956–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li R, Guan Z, Bi S, Wang F, He L, Niu X, et al. The proton-activated G protein-coupled receptor GPR4 regulates the development of osteoarthritis via modulating CXCL12/CXCR7 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13: 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slepak TI, Guyot M, Walters W, Eichberg DG, Ivan ME. Dual role of the adhesion G-protein coupled receptor ADRGE5/CD97 in glioblastoma invasion and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2023;299: 105105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang H, Hou P, Wang X, Xiang A, Wu H, Qi W, et al. CD97 negatively regulates the innate immune response against RNA viruses by promoting RNF125-mediated RIG-I degradation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20:1457–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn HA, Orlandi C, Martemyanov KA. Beyond the ligand: extracellular and transcellular G protein-coupled receptor complexes in physiology and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2019;71:503–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsiao C-C, Wang W-C, Kuo W-L, Chen H-Y, Chen T-C, Hamann J, et al. CD97 inhibits cell migration in human fibrosarcoma cells by modulating TIMP-2/MT1- MMP/MMP-2 activity–role of GPS autoproteolysis and functional cooperation between the N- and C-terminal fragments. FEBS J. 2014;281:4878–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park GB, Kim D. Microrna-503-5p inhibits the CD97-mediated JAK2/STAT3 pathway in metastatic or paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2019;21:206–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figures S1–S10. Fig S1 Heat map of cluster analysis of differential protein expression. Fig S2 Wikipathways Enrichment Analysis Top 20 Bar Plot. Fig. S3 TNFSF11 and CTSK expression in joint fluid of each group. Fig. S4 Expression of ADGRE5 in joint fluid in each group. Fig S5 KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in the blue module top20 (upregulated differences) bubble plots. Fig S6 The lines in the network diagram of represent the degree of connection between genes. Fig S7 KEGG enrichment analysis of characteristic metabolites in the turquoise module top20 bubble plots. Fig S8 The lines in the network diagram represent the degree of connection between metabolites. Fig S9 Expression of 7 13(S)-HPODE in joint fluid in each group.Fig S10 The concentration of MDA in each group's synovial fluidFig S10 The concentration of MDA in each group's synovial fluidFig S10 The concentration of MDA in each group's synovial fluid.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Original data of differentially expressed proteins after filtering. Table S2. Original data of differentially expressed metabolites after filtering.

Additional file 3: Original images of all western blots analyzed in the present study.

Data Availability Statement

Proteomics data were deposited into the ProteomeXchange Consortium under accession number PXD067331 and are available at the following URL: https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD067331. Metabolomics data from this study were deposited into the MetaboLights repository under accession number MTBLS12866 and are available at the following URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS12866.