Abstract

Background

Medical educators operate in high-pressure environments where resilience is critical to their well-being and professional effectiveness. Studies exploring how medical educators conceptualise resilience is limited, particularly outside Western contexts. As such, research investigating culturally-sensitive conceptualisations of resilience in an Asian context is overdue. This study addresses this gap by exploring how medical educators in Hong Kong (HK) conceptualise resilience, attending to the cultural and professional nuances that shape these understandings.

Method

Twenty medical educators teaching medical students, trainees and/or physicians at HK’s two medical schools were recruited via email using maximum variation sampling. Semi-structured online interviews were conducted in English, audio- and video-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Researchers adopted a constructivist epistemology and employed a socio-ecological model to guide Reflexive Thematic Analysis of the transcripts.

Results

Medical educators predominantly conceptualised resilience as a dynamic process, though some also described it as an outcome of navigating adversity, and to a lesser extent, as an inherent trait. Notably, conceptualisations of resilience as a process and as an outcome often overlapped. Adversity was consistently identified as a fundamental component across definitions. Participants aligned their understandings of resilience closely with their professional roles and pervading sociocultural influences, emphasising relational and cultural dimensions. This holistic approach distinguished their perspectives from more individualised Western notions of resilience.

Conclusions

Traditional Western frameworks of resilience may not adequately capture its complexities in other cultural contexts. Echoing the socio-ecological model, participants’ conceptualisations were deeply intertwined with HK’s cultural values and socio-contextual dynamics. These findings underscore the need to broaden global understandings of resilience beyond Western paradigms. Importantly, our findings can inform the design of culturally-sensitive faculty development programmes aiming to support medical educator resilience in the future.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07834-z.

Keywords: Resilience, Medical education, Educators, Teachers, Conceptualisation, Asia, Culture, Socio-Ecological

Background

Resilience, a complex and much debated concept, has gained prominence within medical education due to the alarming rates of psychological distress and suicide reported among healthcare practitioners and students globally [1–6]. Fostering resilience within medical education is a promising avenue for mitigating psychological distress, with evidence suggesting that targeted training can successfully promote resilience among medical students [7]. In the existing literature, which is predominantly Western, resilience has typically been defined either as a personal trait, a process of positive adaptation, or an outcome reflecting successful coping or recovery [8–10]. These definitions often emphasise individualistic attributes such as emotional regulation and self-efficacy. However, more contemporary perspectives assert that resilience is not static but exists on a continuum, varying across multiple domains of life and changing over time depending on one’s interactions with the environment [11, 12]. Despite these developments, there remain wide discrepancies in how resilience is conceptualised across studies [13–17].

While much attention has been placed on developing the resilience of healthcare students and practitioners, there has been comparatively limited focus on the resilience of medical educators themselves. Medical educators juggle multiple roles including clinical and non-clinical responsibilities [18]. Studies have highlighted educators’ fears of burnout amid long work hours and the struggle to balance their professional and personal roles [16]. Resilience is essential for navigating endemic stress and professional obstacles but empirical research on resilience in medical educators remains limited, and hitherto predominantly confined to Western contexts [19–23].

There are universal (etic) and culture-specific (emic) aspects to resilience [24]. Universality is overrepresented in the current literature, with few studies including culture-specific aspects of resilience [25–27]. Championing a perspective shift, Ungar argues that resilience is culturally embedded, emphasising the need to examine it within specific cultural settings [27]. Accordingly, a growing body of literature warns that non-culturally sensitive definitions of resilience can lead to ineffective or even harmful interventions by ignoring local contexts, cultural values, and collective experiences of adversity, thereby limiting the potential for genuine resilience and well-being [26, 28, 29].

Broadly, East Asian cultures – including Chinese, Japanese, and local Hong Kong societies – tend to emphasise relational harmony, respect for hierarchical and generational structures, and a collectivist orientation [30–33]. Discussions around mental health and well-being may be less openly expressed, shaped by social norms that value emotional restraint and interdependence [33, 34]. Chinese values are historically rooted in Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, which originated between the 5th and 6th century BC [33, 35–37]. Confucianism and Taoism emerged in ancient China, while Buddhism originated in India and later spread to China where it was integrated into Chinese cultural and philosophical traditions [37]. These teachings urge acceptance of adversity and deeply influence ethical frameworks, through social duty (Confucianism), suffering (Buddhism), or natural harmony (Taoism) [35–38]. Recognising the traditional teachings of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism offers prudent cultural context for understanding resilience. Their enduring influence within Chinese culture and society continues to shape how individuals perceive and navigate hardship, making these philosophies pertinent to discussions of resilience [38].

Specifically, Hong Kong’s (HK) unique historical trajectory has shaped its cultural identity, from millennia under the Chinese Imperial system, through British Colonial rule (1842–1997) to its recent 1997 transition into a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China [39]. This sequenced blend of cultural influences, together with its traditional function as an interface between other parts of China and the West has made HK a microcosm of globalisation. Understanding and incorporating cultural sensitivity within research is critical to obtaining meaningful and inclusive insights, especially in socio-culturally dependent concepts such as resilience.

Our study explores how medical educators in HK conceptualise resilience, with a focus on uncovering the cultural nuances that shape these understandings. Accordingly, the specific questions guiding our research are as follows:

How do medical educators in HK conceptualise resilience?

What factors influence these conceptualisations of resilience?

Our findings could inform the development of tailored, multifaceted interventions to foster resilience within this community of practice. Strengthening resilience among medical educators has the potential to enhance educator well-being and the quality of healthcare education. Thus, by examining resilience within an East Asian cultural framework, our study contributes a novel perspective to global discussions on resilience in medical education, offering insights applicable beyond HK.

Method

This qualitative study was part of a larger multi-phased mixed-methods research project investigating resilience among medical educators in HK. Approval was granted by the research ethics committees of the University of Hong Kong and the Chinese University of Hong Kong. We followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guideline (see Additional File 1, eTable 1) [40].

Study design and setting

This qualitative study was conducted within the context of HK’s medical education system which follows a British-influenced model. It comprises a six-year undergraduate Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery programme, followed by a one-year internship and then six years of postgraduate specialist training overseen by the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. HK’s position at the intersection of Eastern and Western cultural influences and the high-pressure academic environment provided a unique backdrop for exploring how resilience may be understood and manifested in medical education. This phase of the study aimed to capture medical educator conceptualisations of resilience through in-depth, semi-structured interviews.

Participants

Eligible subjects were medical educators from the University of Hong Kong and the Chinese University of Hong Kong, involved in teaching medical students, trainees, and/or physicians. From among eligible medical educators, maximum variation sampling based on sociodemographic background, profession, and medical education experience was used to recruit participants via email to be involved in semi-structured interviews. They completed an anonymous online sociodemographic questionnaire (Additional File 1, eMethod 1) developed using Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com).

Conceptual Framework

This study was grounded in a socio-ecological framework, wherein resilience was viewed as a dynamic process shaped by the continuous interaction between individuals and their environments [28]. The socio-ecological model provided a lens to examine how medical educators navigated and interpreted resilience within both personal and professional spheres. Throughout data collection, analysis, and interpretation, the socio-ecological framework guided our understanding of resilience as a multifaceted construct influenced by individual experiences, interpersonal relationships, institutional demands, and cultural values. During analysis, this perspective helped the research team remain attentive to how these different levels of influence manifested in participants’ narratives.

Data collection

Semi-structured, one-to-one Zoom interviews (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, California) were conducted by the principal investigator in English between June 2021 and April 2022 (interview guide in Additional File 1, eMethod 2). As an academic physician with a master’s in medical education, her research interests centre on the resilience and well-being of healthcare professionals (further details in Additional File 1, eMethod 2). Interviews lasted 24 min 44 s on average and were recorded in audio and video formats. Recordings were transcribed verbatim, proofread, and anonymised. Data collection was concluded when no new themes were identified, and subsequent interviews yielded no additional conceptual insights. This approach aligned with the principle of information power, whereby sample adequacy was determined by the richness and relevance of the data in relation to our study’s research questions [41].

Theoretical approach and data analysis

Our team included researchers from diverse cultural and multidisciplinary backgrounds including medical education, clinical medicine, biomedical and health sciences, and psychology. We used the socio-ecological model as our conceptual framework [28]. This model assisted in identifying context-specific factors, which were typically overlooked in research. Guided by a constructivist epistemological perspective, we employed an inductive Reflexive Thematic Analysis (TA) approach [42]. In this study, we used the term “conceptualisations” to refer to the varied ways participants understood and articulated the concept of resilience, which aligned with the exploratory nature of reflexive TA. A review of the literature was performed prior to conducting the analysis to sensitise the research team to the subtle concepts that could be present in the data. Drawing from Braun and Clarke [42], the analysis involved six main phases: familiarisation with the data; coding; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes; and writing up.

Transcripts were analysed by five researchers using NVivo software version 12 (Lumivero, Denver, Colorado) from December 2023 to February 2024. All transcripts were read twice by all researchers, with notes taken. An initial framework of themes and sub-themes was developed through team discussion. Review of the first framework iteration occurred individually followed by team discussion. Codes were adjusted iteratively by team consensus. Initial thematic categories were re-examined for significance in addressing the research questions and assessed for accurate representation of participants’ responses. Analysis was reflexive, involving continual critical reflection on the researchers’ subjective interpretations. To enact this reflexivity, the research team engaged in regular group debriefing sessions, collaboratively examining and discussing individual perspectives on the data plus analyses. During this process, we developed themes that were guided by our shared and evolving understanding of resilience as a socio-ecological concept. Emergent themes were refined iteratively until the final themes were agreed upon by all researchers and named to reflect their core narrative.

Results

Participant characteristics

Twenty medical educators (50% male; 50% female) participated, of whom 10 (50%) had medical degrees. Professional backgrounds also included biomedical sciences, nursing, and pharmacy. Most participants were ethnically Chinese (85%), employed full-time (85%), and between 30 and 49 years old (60%). Some had been working as medical educators for 5–9 years (30%). For more details on participant sociodemographics, please see Additional File 1, eTable 2.

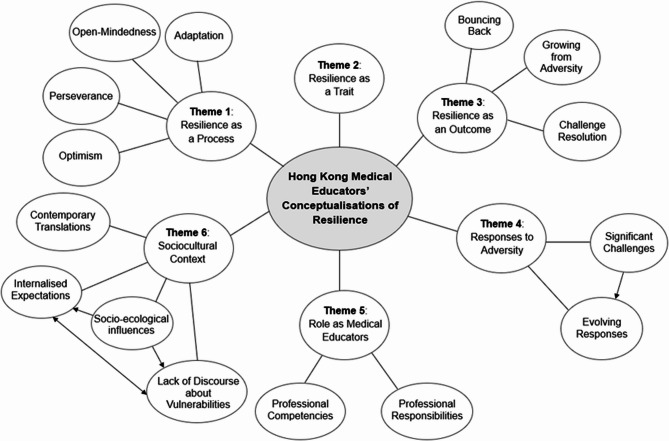

HK medical educators primarily considered resilience to be a dynamic process that interacted with adversities within their unique professional and sociocultural context. Six interrelated themes and their sub-themes (Fig. 1) were identified, as outlined in Table 1. Rather than viewing these themes as discrete categories, participants often described resilience in ways that overlapped, reflecting its multifaceted nature. Medical educators conceptualised resilience as: (1) a process; (2) a trait; (3) an outcome; (4) a response to adversity; (5) a characteristic inherent within their roles as medical educators and; (6) as shaped by their sociocultural context. Interested readers may view the detailed thematic codebooks in Additional File 1, eTables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.

Fig. 1.

Concept map of qualitative interview themes and sub-themes related to how twenty medical educators in Hong Kong conceptualised resilience (2021-2022)

Table 1.

Qualitative interview themes, sub-themes, and exemplar quotations of twenty Hong Kong medical educators’ conceptualisations of resilience (2021–2022)

| Theme and Sub-themes | Exemplar Quotations |

|---|---|

|

Resilience as a Process This includes sub-themes such as adaptation, perseverance, optimism, and open-mindedness. |

(Q1) How can I adapt to the changes? (Participant 11) (Q2) We’ve got to maintain in a stressful environment… (Participant 13) (Q3) A lifelong journey and lifelong learning and growing in resilience through different experiences in our lives, most of which we do not have control over, but what we do have control over is how we respond to it. (Participant 1) (Q4) And so that appreciation that we need to be resilient to recognise that what may have worked in the past, may not work now. (Participant 12) (Q5) With great optimism that we all can overcome this ah, adversity with the, with resilience. (Participant 19) |

|

Resilience as a Trait This includes traits that people have. |

(Q6) We of course we are all different, and there are certain personalities, that will actually allow us to be more resilient than others and ah things that you will never be able to learn just in built. (Participant 8) |

|

Resilience as an Outcome This includes sub-themes of bouncing back, growing from adversity, and challenge resolution. |

(Q7) I see it as just the ability to face challenges and to overcome it, bounce back quickly when faced with challenges. (Participant 12) (Q8) To be able to grow, or even be strengthened through challenges and pressures. (Participant 1) (Q9) So, resilience is the ability to overcome ah… missteps or overcome mistakes um and be able to focus on original goals or intentions, plans, ah regardless of how bumpy the road is. (Participant 7) |

|

Responses to Adversity This includes two sub-themes: significant challenges and evolving responses. |

(Q10) Especially in the valleys, in the darker times, when there are perhaps multiple pressures or we’re low in energy and physically not the best. (Participant 1) (Q11) It’s not just against any unforeseeable condition or crisis basically become part of daily um…. living. (Participant 13) (Q12) If we’re not able to gauge our own level of well-being, if we’re not able to gauge our own needs, and also the things that are actually unhelpful. um… If we’re unable to set boundaries, whether it be time boundaries, work boundaries, relational boundaries and then these things can all…I think can all significantly hinder our ability to develop resilience. (Participant 1) (Q13) I think, you know, and maybe you you’re sort of master I don’t know, um, life or challenges as such, and sort of you build your style. (Participant 18) |

|

Roles as Medical Educators This includes sub-themes of professional responsibilities and professional competencies. |

(Q14) Resilience is basically is just getting what…um… we can do, right, to um in a way, we can do to fulfil the learning outcome. (Participant 13) (Q15) You can continue to function or make decision in a, in a sort of desirable, sort of managing the risk, as well as delivering the teaching necessary for your students. (Participant 18) (Q16) I mean life has to go on. Medical education has to go on; and we need to make sure these trained healthcare professionals are competent. (Participant 5) |

|

Sociocultural Context This includes sub-themes of contemporary translations, socio-ecological influences, internalised expectations, and lack of discourse about vulnerabilities. |

(Q17) I think, from a Chinese point of view, probably, we… we… have received a lot of thinking from Taoism or Confucianism. (Participant 2) (Q18) I agree, it seems that resilience is not, is more like a Western concept to me. (Participant 10) (Q19) But when I looked those translations… they don’t quite 100% translate all the meanings and connotations associated with the word resilience. (Participant 1) (Q20) I think every generation develops its own ways of dealing with things. But I grew up in and I’ve seen turbulent times in different environment. So it’s really honing down on what are your values and what you think are important and what you need to hold on to in order to be a good teacher? (Participant 14) (Q21) Parents they always point out the ah, the children the negative side and tell them to do things, not to do this, not to do that. Rather than in a way, positive reinforcement. (Participant 13) (Q22) In Western countries they think that resilience is kind of ability, that is, we have to try and to, we have to try acquire this kind of ability, but for Chinese, I have a sense that people think that. Even though you, you can…. you should have this kind of responsibility to overcome all the challenges. Ah… is not something additional but it’s your responsibility, I guess. (Participant 2) (Q23) I feel like maybe Chinese are not as good at expressing our stress. I don’t know like we, we tend to hold it to ourselves, and if we discuss ah, stress or, or adapting to stress, um, maybe we will be seen as a bit incompetent or inadequate. (Participant 5) |

Resilience as a process

HK medical educators predominantly understood resilience to be a dynamic, ongoing process, characterised by a proactive, flexible, and variable approach to challenges. This theme highlighted resilience as a multifaceted phenomenon that developed and transformed in response to challenges. Participant 11 succinctly encapsulated this view by framing resilience as a continuous question: “how can I adapt to the changes?”. This reflected the sub-theme adaptation, where resilience was seen as the ability to adjust to shifting circumstances. Similarly, perseverance emerged as a key component of this process, with Participant 13 describing resilience as “to maintain in a stressful environment”, emphasising the enduring commitment to overcoming difficulties.

Another crucial aspect of this process-oriented view was optimism during adversity. Participant 19 expressed confidence in overcoming challenges: “with great optimism that we all can overcome this adversity”. This positive outlook was often accompanied by the sub-theme open-mindedness, where medical educators recognised that while they may not be able to control external events, they could control their responses. As Participant 1 reflected: “different experiences in our lives, most of which we do not have control over, but what we do have control over is how we respond to it”.

These perspectives suggested that resilience was not a fixed state but an evolving process, influenced by both external circumstances and internal attitudes. However, this process-based conceptualisation did not exclude other interpretations, such as viewing resilience as an inherent trait. This divergence suggested that personal experiences and cultural narratives could influence whether resilience was seen as something developed by an individual over time or something they were born with.

Resilience as a trait

While many educators described resilience as a process, a subset viewed it as an innate, stable characteristic. This theme presented resilience as a personal trait that individuals either possessed or lacked, suggesting limited potential for development. Participant 8 articulated this perspective, stating: “we are all different, and there are certain personalities that will actually allow us to be more resilient than others and things that you will never be able to learn, just in-built”. This view implied that resilience was an intrinsic quality, influenced by one’s personality, rather than something cultivated over time. While some educators saw resilience as an innate trait—unchanging and in-built—others described it as a malleable process shaped by ongoing challenges. Interestingly, these seemingly opposing views often coexisted within the same narratives, suggesting that resilience might be both a foundational characteristic and something that evolves through experience.

Resilience as an outcome

Resilience was also conceptualised by HK medical educators as an outcome, reflecting the observable effects, changes, or developments that occurred after facing adversity. This theme encompassed notions of bouncing back, growing from adversity, and challenge resolution. However, educators’ descriptions of resilience as an outcome often overlapped with process-based definitions, blurring the lines between resilience as an end state and resilience as an ongoing journey.

Resilience was often synonymous with the sub-theme bouncing back, portraying a swift recovery from adversity. Participant 12 described resilience as “the ability to face challenges and to overcome it, bounce back quickly when faced with challenges”. This definition emphasised resilience as a measurable result—returning to a previous state of stability or normalcy after adversity. However, even within this seemingly straightforward outcome-based view, the notion of resilience as a process was implicit. The act of ‘facing’ challenges and ‘overcoming’ them suggested an active, ongoing effort rather than a passive return to form. Thus, while ‘bouncing back’ appeared to be an end result, it also reflected the adaptive processes that enabled recovery.

In addition to recovery, many educators framed resilience as growing from adversity, highlighting not just the ability to return to a previous state, but to emerge stronger or more capable. Participant 1 articulated this by describing resilience as being “able to grow or even be strengthened through challenges and pressures”. This view situated resilience as both an outcome and a developmental process. Growth was seen as the cumulative result of engaging with adversity, suggesting that resilience was not a static endpoint but an evolving capacity shaped by successive life experiences. Here, the process of learning and adapting through challenges directly contributed to the outcome of personal and professional growth.

The sub-theme challenge resolution further illustrated this overlap between process and outcome. Participant 7 defined resilience as “the ability to overcome… missteps or mistakes”, framing it as a future-focused capacity that enabled individuals to move forward despite adversity. This perspective treated resilience as a practical skill—successfully resolving difficulties—but the resolution itself was the product of underlying processes such as reflection, learning, and adaptation. The resolution of one challenge often equipped educators with strategies and insights to navigate future adversities, reinforcing resilience as an iterative process rather than a finite result.

This interplay between process and outcome was evident in how educators described their personal experiences with resilience. While bouncing back could signify a quick recovery, the mechanisms that facilitated recovery—such as perseverance, optimism, and adaptability—were inherently process-driven. Similarly, growing from adversity reflected the idea that resilience was not just about returning to a baseline but about transformation and continuous development, indicating that outcomes were shaped by the processes that preceded them. In sum, outcome-oriented terms were deeply intertwined with process-based elements. Resilience was rarely seen as a singular, static endpoint; instead, outcomes such as recovery, growth, and resolution were framed as the cumulative effects of dynamic, ongoing processes. Thus, resilience was best understood not as a binary state of having ‘achieved’ or ‘not achieved’ an outcome, but as a continuous interplay between enduring challenges and the personal development that resulted from them.

Responses to adversity

Adversity was consistently identified as the catalyst for resilience, emphasising that resilience did not exist in a vacuum but arose in response to significant challenges. Medical educators highlighted various forms of adversity, from professional pressures to personal struggles, which shaped their understanding of resilience. Participant 1 reflected on the emotional and physical toll of adversity: “the valleys, in the darker times, when there are perhaps multiple pressures or we’re low in energy and physically not the best”. Interestingly, most medical educators focused on significant life-altering challenges, rather than routine daily stressors in their accounts of resilience. Only one participant, Participant 13, mentioned everyday difficulties, stating: “it’s not just against unforeseeable condition or crisis basically become part of daily…living”.

The sub-theme evolving responses built upon significant challenges, underscoring how resilience was developed through accumulated experiences and self-awareness. Participant 12 expressed the importance of self-reflection in resilience: “our ability to develop resilience”, depended on understanding our own “well-being”, “needs”, and “boundaries”. This view suggested that resilience was a learned response, refined over time. Participant 18 highlighted how life experiences contributed to resilience, stating: “you’re sort of a master of…life or challenges as such, and…build your own style”. This emphasised the cumulative nature of resilience, where each challenge strengthened one’s capacity to face future adversities. These reflections revealed that adversity was not merely an external challenge but a transformative force, shaping resilience across personal and professional domains.

Roles as medical educators

For HK medical educators, resilience was deeply intertwined with their professional identities and responsibilities. The demands of their roles often necessitated resilience, both in fulfilling educational obligations and maintaining professional standards. The sub-theme professional responsibilities highlighted how resilience was linked to the duty of educating future healthcare professionals. Participant 13 described resilience as “just getting what… we can do right to… fulfil the learning outcome”, emphasising the commitment to student success despite challenges. Similarly, Participant 18 noted that resilience involved “delivering the teaching necessary for your students”, framing it as a professional obligation. In addition to responsibilities, professional competencies were seen as integral to resilience. Participant 5 stressed the importance of perseverance in medical education: “I mean life has to go on. Medical education has to go on; and we need to make sure these trained healthcare professionals are competent”. This underscored how resilience was not just a personal attribute but a professional necessity, ensuring the continuity and quality of healthcare education. These findings suggested that for HK medical educators, resilience was about upholding professional standards and contributing to the broader healthcare system.

Sociocultural context

HK medical educators’ understanding of resilience was profoundly shaped by their sociocultural environment. Cultural norms, societal expectations, and traditional values influenced how resilience was conceptualised and practised. The sub-theme contemporary translations revealed tensions between Western conceptualisations and traditional Chinese frameworks of resilience, presenting challenges in defining resilience. Participant 10 noted, “it seems that resilience is…more like a Western concept to me”, while Participant 1 observed that Chinese translations of ‘resilience’ “don’t quite 100% translate all the meanings and connotations associated with the word”. This reflected a cultural dissonance, where Western individualistic notions of resilience clashed with collectivist values rooted in traditional Chinese philosophies of “Taoism” and “Confucianism”, as proposed by Participant 2. The dual perception of resilience as both a Western concept and also one grounded in traditional Chinese philosophies highlighted the tension between global and local frameworks in HK medical education. This tension reflected broader shifts in HK’s medical education system, where Western pedagogical models were found to intersect with deeply ingrained cultural values, influencing how educators approached their roles and personal development.

Socio-ecological influences further shaped resilience interpretations. Parenting styles, for example, were frequently cited. Participant 13 remarked, “parents, they always point out the…negative side and tell [children] to do things, not to do this, not to do that. Rather than…positive reinforcement”. Environmental factors were mentioned by Participant 14: “every generation develops its own ways of dealing with things. But…I’ve seen turbulent times in different environment”. This suggested that upbringing could influence how individuals developed and expressed resilience.

Socio-ecological circumstances set the context for the prevalent sub-themes internalised expectations and lack of discourse about vulnerabilities. HK-based medical educators felt pressured to conceal vulnerabilities and uphold traditional Chinese societal norms to appear resilient. Participant 2 reflected on societal pressure: “for Chinese …you should have this kind of responsibility to overcome all the challenges”. Expectations were perpetuated by the discouragement of discussion about vulnerabilities, and vice versa, upholding traditional stigmas around struggling in the face of adversity. Participant 5 noted: “I feel like maybe Chinese are not as good at expressing our stress…we tend to hold it to ourselves, and if we discuss ah, stress or, adapting to stress, maybe we will be seen as a bit incompetent or inadequate”. These insights revealed a cultural stigma around vulnerability, where resilience was equated with stoicism and emotional restraint. Sociocultural factors not only influenced how resilience was defined but also how it was embodied in both personal and professional contexts.

Summary of findings

HK medical educators conceptualised resilience as a multifaceted and dynamic construct shaped by personal attributes, professional roles, and sociocultural influences. The six themes identified were presented as distinct categories, however these themes were deeply interconnected. Resilience as a process often led to observable outcomes, while personal traits influenced how individuals engaged with adversity. Professional roles necessitated resilience, but these roles were themselves shaped by sociocultural expectations and norms. Overall, resilience was seen as a dynamic interplay between personal characteristics, professional demands, and cultural norms, emphasising its complex, context-dependent nature.

Discussion

HK medical educators conceptualised resilience as a dynamic process that evolved over time whereby an individual applied contextually and culturally meaningful resources to navigate adversity. Resilience was seen not only as an evolving capability but also as a product of overcoming adversity, highlighting its cyclical nature—where each challenge strengthened future resilience. Medical educators strongly identified with their professional roles, closely aligning their conceptualisations of resilience with their responsibilities as medical educators. Participants noted the nuanced sociocultural dimensions of resilience, highlighting the inadequacy of applying Western frameworks without considering local cultural contexts.

While our study aimed to explore participants’ perspectives on resilience, situating these within broader theoretical frameworks would be essential. Our results resonated with both process- and outcome-oriented conceptualisations in the literature [6, 11, 16, 43]. However, the recognition of the broader context and cultural differences aligned our results most appropriately with the socio-ecological model of resilience [43]. This model acknowledged the complex interplay between individual, social, and environmental factors influencing resilience [28]. The dynamic, context-dependent interpretations offered by HK medical educators reflected this multisystemic perspective, underscoring that resilience was both personally cultivated and shaped by professional roles and sociocultural environments. This contextually sensitive definition of resilience was also reported in previous research examining resilience among physicians and nurses, supporting our focus on medical educators [44, 45].

Adversity was identified as a fundamental catalyst for resilience, echoing scholarly consensus [43]. However, one participant acknowledged the idiosyncratic nature of individuals’ responses to stressors and suggested that resilience was not limited to responses to major life events but also encompassed the ability to manage everyday stressors and routine challenges, aligning with broader conceptualisations in the literature [46]. This perspective was not widely reflected across the dataset, highlighting a point of divergence from the predominant view. Additionally, participants highlighted that those responses to adversity were not static but evolved over time through accumulated life experiences, self-awareness, and reflective practices. Thus, resilience was continually redefined across personal and professional contexts [44]. Participants supported this notion by conceptualising resilience within the context of medical education and their sociocultural environment.

Roles as medical educators

HK medical educators’ professional roles were integral to their resilience narratives, and they often viewed resilience as essential to fulfilling their educational responsibilities and maintaining professional standards. Unlike U.S. medical educators, who conceptualised resilience from an individualist perspective, HK medical educators often held more traditional collectivist views, incorporating community and professional responsibilities [47, 48]. This narrative, typical of Chinese and broader Asian cultures, merged personal and professional identities within an achievement-oriented culture [49]. The educators’ own professional identities may have served as a foundation for resilience conceptualisation, providing a framework for navigating challenges, upholding professional standards amidst adversity, and offering a sense of purpose [50–52]. Professional identity development was argued to have a reciprocal relationship with resilience, as educators drew upon their values and beliefs to persevere in fulfilling their responsibilities [51–53]. Ultimately, their professional identity served as a lens for interpreting setbacks as opportunities for growth and development, and the pursuit of professional goals served as a manifestation of their resilience [54]. How the culturally-sensitive relationship between professional identity and conceptualisations of resilience differs between medical educators and purely clinically-focused practitioners represents an intriguing area for further research.

Sociocultural context

The sociocultural context of HK played a pivotal role in shaping educators’ conceptualisations of resilience. HK medical educators used metaphors, such as bamboo or elastic bands, to capture resilience. While the term ‘resilience’ may not readily translate across cultures, examining the synonyms and metaphors used provided valuable insights. Participants noted that ideas and language about resilience stemmed from traditional belief systems, including Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, which emphasised accepting adversity, compared with the Western focus on controlling one’s circumstances [35, 36, 38, 55].

Research demonstrated parallels in how traditional non-Western belief systems could shape resilience conceptualisations. A study of resilience among Afghans revealed that participants derived hope from the acceptance of God’s will, and that the highly contextual structure of traditional communal family life could be a source both of strength and stress to individuals [56]. Similarly, traditional Chinese beliefs shaped the social, cultural, and environmental factors influencing resilience conceptualisations in HK. Deep-seated societal norms, such as parenting that emphasised adversity as character-building, frame failure as a growth opportunity rather than a setback [57, 58]. By encouraging children to face difficulties independently, parents instilled resilience as a fundamental value. Additionally, the relational orientation inherent in Chinese culture prioritised social and familial relationships over individual needs, promoting adherence to social expectations and conflict avoidance [59–61].

Such emphasis on familial harmony, rooted in traditional values, reinforces resilience expectations within the family unit [59, 61]. In HK’s East Asian culture, where social connectedness is highly valued, suppressing negative emotions to preserve harmony is promoted [62]. Participants noted that expressing negative feelings led to concerns about social perception and reputation, as echoed in the literature [63]. Fundamental differences between East Asian and Western cultures could present social tensions for East Asian medical educators teaching in Western settings. The implications of this on resilience and vulnerability to mental health issues has been demonstrated among Chinese university students and represents another interesting avenue for future research [64].

Our study demonstrated that even in HK’s unique confluence of Western and Chinese cultures, Western-centric perspectives on resilience did not always align with HK Chinese culture, reinforcing the need for cultural sensitivity despite growing globalisation. As the process of dealing with adversity has often been depicted as relational in Chinese culture, it is plausible that sociocultural circumstances may have had a significantly greater impact on conceptualisations of resilience here than in the West, making recognition of the dynamic cultural environment imperative [60].

Limitations

Our study was subject to several limitations. First, interviewing participants in English may have constrained the depth of language available to comprehend and articulate resilience. Although this limitation is inherent to studies conducted in a secondary language for the respondents, we sought to mitigate this language filter by remaining attentive to culturally nuanced expressions, including checking the meaning of Chinese metaphors and idioms referenced by participants during analysis to ensure contextual accuracy. Second, the sample may not have been fully representative as it consisted solely of tertiary institution-affiliated medical educators. Third, the analysis predominantly represented perspectives from the field of medicine, possibly overlooking experiences of other health professions educators. Lastly, we acknowledge that the multicultural composition of the research team, while enriching the reflexive process, may have influenced theme construction through our respective cultural lenses and interpretive positions.

Implications

Our study highlights the necessity for culturally sensitive approaches, emphasising linguistic and applicational nuances when designing interventions to support resilience in medical educators. Our findings point to the need for an adaptable and holistic framework of resilience – one that can accommodate and absorb culturally specific meanings, values, and expressions of resilience. Moreover, future research should recognise resilience not solely as an individual trait but as a dynamic, contextually embedded process shaped by communal elements such as family support, community networks, and spiritual or philosophical beliefs. By positioning resilience as a shared endeavour, such frameworks could integrate this important characteristic that is present, to varying degrees, in Western and HK conceptualisations of resilience [47]. Through promoting an adaptable and expanded understanding of resilience amidst globalisation within their community of practice, medical educators would be better equipped to appreciate the experiences and perspectives of resilience among their colleagues. Institutional leadership, administrators and faculty may draw upon our findings to create inclusive environments that foster resilience and well-being in medical educators of varying cultural backgrounds, with the aim of enhancing medical education practices and ultimately benefitting student learning.

Conclusions

Our investigation into how HK medical educators conceptualised resilience demonstrated a significant cultural gap in existing research. Despite limited studies on resilience in this population, our findings underscored the profound influence of culture on the context of being a medical educator. Whilst participants echoed the fundamental components of Western conceptualisations of resilience, their identities as medical educators within the sociocultural context of HK distinguished resilience definitions within this community of practice. Our findings offered critical determinants that could inform the successful design of culturally sensitive faculty development programmes that aim to cultivate resilience among medical educators in the future. Alignment with the socio-ecological model of resilience also highlighted the need for further exploration of resilience within diverse cultural contexts to inform targeted interventions supporting medical educators.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all medical educators who participated in the study from The University of Hong Kong and The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Other disclosures

C.R. Whitehead is the holder of the BMO Financial Group Chair in Health Professions Education Research at University Health Network.

Abbreviations

- HK

Hong Kong

- TA

Thematic Analysis

Authors’ contributions

L.C. obtained funding for the study. L.C., J.C., G.T., F.G., T.L., and S.W. were involved in the conceptualisation and design of the study. L.C., G.T., C.W., E.B., P.C., Z.T., S.Y., and C.W. were involved in the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data. L.C. and E.B. were responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors gave their final approval for this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by the Enhanced New Staff Start-up Research Grant at the University of Hong Kong (grant number: 204610401).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee for Non-clinical Faculties of the University of Hong Kong (ref: EA200136) and by the Joint CUHK-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (ref: 2021.079). The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which included obtaining informed consent from participants prior to them joining the study and assuring their anonymity.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cheng J, Kumar S, Nelson E, Harris T, Coverdale J. A national survey of medical student suicides. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):542–6. 10.1007/s40596-014-0075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, Dambrun M, Moustafa F, Mermillod M, Baker JS, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Navel V. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0226361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–73. 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howe A, Smajdor A, Stockl A. Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):349–56. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, Sen S. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373–83. 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience. The science of mastering life’s greatest challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shorbagi AI. Promoting resilience among medical students using the Wadi framework: a clinical teacher’s perspective. Front Med. 2024;11: 1488635. 10.3389/fmed.2024.1488635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayed N, Toner S, Priebe S. Conceptualizing resilience in adult mental health literature: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Psychol Psychother. 2019;92(3):299–341. 10.1111/papt.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stainton A, Chisholm K, Kaiser N, Rosen M, Upthegrove R, Ruhrmann S, Wood SJ. Resilience as a multimodal dynamic process. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(4):725–32. 10.1111/eip.12726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zautra AJ, Hall JS, Murray KE, the Resilience Solutions Group 1. Resilience: a new integrative approach to health and mental health research. Health Psychol Rev. 2008;2(1):41–64. 10.1080/17437190802298568. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim-Cohen J, Turkewitz R. Resilience and measured gene-environment interactions. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24(4):1297–306. 10.1017/S0954579412000715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM. Psychological resilience in OEF-OIF veterans: application of a novel classification approach and examination of demographic and psychosocial correlates. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(3):560–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aburn G, Gott M, Hoare K. What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(5):980–1000. 10.1111/jan.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzau VJ, Kirch D, Nasca T. Preventing a parallel pandemic - a national strategy to protect clinicians’ well-being. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):513–5. 10.1056/NEJMp2011027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung GM, Cowling BJ, Wu JT. From a sprint to a marathon in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e45. 10.1056/NEJMc2009790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–62. 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers D. Which educational interventions improve healthcare professionals’ resilience? Med Teach. 2016;38(12):1236–41. 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1210111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girod SC, Fassiotto M, Menorca R, Etzkowitz H, Wren SM. Reasons for faculty departures from an academic medical center: a survey and comparison across faculty lines. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):1–10. 10.1186/s12909-016-0830-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sethi A, Ajjawi R, McAleer S, Schofield S. Exploring the tensions of being and becoming a medical educator. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17: 62. 10.1186/s12909-017-0894-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan L, Dennis A. Resilience: a nationwide study of medical educators. MedEdPublish. 2019;8(1):20. 10.15694/mep.2019.000020.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Batting 300 is good: perspectives of faculty researchers and their mentors on rejection, resilience, and persistence in academic medical careers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):497–504. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285f3c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sood A, Prasad K, Schroeder D, Varkey P. Stress management and resilience training among department of medicine faculty: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(8):858–61. 10.1007/s11606-011-1640-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tusaie K, Dyer J. Resilience: a historical review of the construct. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18(1):3–10. 10.1097/00004650-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triandis HC, Suh EM. Cultural influences on personality. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53(1):133–60. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panter-Brick C. Culture and resilience: Next steps for theory and practice. InYouth resilience and culture: Commonalities and complexities Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014. p. 233–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5(1): 25338. 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ungar M. Cultural dimensions of resilience among adults. Handbook of adult resilience. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. p. 404–23.

- 28.Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work. 2008;38(2):218–35. 10.1093/bjsw/bcl343. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Usher K, Jackson D, Walker R, Durkin J, Smallwood R, Robinson M, Sampson UN, Adams I, Porter C, Marriott R. Indigenous resilience in Australia: a scoping review using a reflective decolonizing collective dialogue. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 630601. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.630601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold T, Guthrie D, Wank D, editors. Social connections in china: institutions, culture, and the changing nature of Guanxi, vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

- 31.Hwang KK. Foundations of Chinese psychology: Confucian social relations. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo BC. Interdependent and relational tendencies among Asian clients: infusing collectivistic strategies into counselling. Guidance Counselling. 2004;19(4):158. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lei Y, Duan C, Shen K. Development and validation of the Chinese mental health value scale: a tool for culturally-informed psychological assessment. Front Psychol. 2025;16:1417443. 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1417443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao G. ‘Don’t take my word for it.’’—understanding Chinese speaking practices. Int J Intercult Relat. 1998;22(2):163–86. 10.1016/S0147-1767(98)00003-0. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng L. The work of laozi: truth and nature. 8th ed. Hong Kong: The World Book Co; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung CG, Wilhelm R, Wilhelm H. The I Ching or book of changes. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meulenbeld M, Confucianism. Daoism, buddhism, and Chinese popular religion. Oxf Res Encyclopedia Asian History. 2019 Nov;22. 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.126.

- 38.Xie Q, Wong DF. Culturally sensitive conceptualization of resilience: a multidimensional model of Chinese resilience. Transcult Psychiatry. 2021;58(3):323–34. 10.1177/1363461520951306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yip A. Hong Kong and china: one country, two systems, two identities. Glob Soc. 2015;3:20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60. 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013;18:12–23. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper AL, Brown JA, Rees CS, Leslie GD. Nurse resilience: a concept analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(4):553–75. 10.1111/inm.12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roslan NS, Yusoff MSB, Morgan K, Ab Razak A, Ahmad Shauki NI. What are the common themes of physician resilience? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):469. 10.3390/ijerph19010469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis MC, Luecken L, Lemery-Chalfant K. Resilience in common life: introduction to the special issue. J Pers. 2009;77(6):1637–44. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan L, Dennis AA. Resilience: insights from medical educators. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):384–9. 10.1111/tct.13058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Satterwhite AK, Luchner AF. Exploring the relationship among perceived resilience, dependency, and self-criticism: the role of culture and social support. N Am J Psychol. 2016;18(1):71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang S, Shu D, Yin H. Teaching, my passion; publishing, my pain: unpacking academics’ professional identity tensions through the lens of emotional resilience. Higher Educ. 2022;84(2):235–54. 10.1007/s10734-021-00765-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaasila R, Lutovac S, Komulainen J, Maikkola M. From fragmented toward relational academic teacher identity: the role of research-teaching nexus. High Educ (Dordr). 2021;82(3):583–98. 10.1007/s10734-020-00670-8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rabow MW, Remen RN, Parmelee DX, Inui TS. Professional formation: extending medicine’s lineage of service into the next century. Acad Med. 2010;85:310–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c887f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):701–6. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beckman H. The role of medical culture in the journey to resilience. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):710–2. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wald HS. Insights into professional identity formation in medicine: memoirs and poetry. Eur Leg Towar New Paradig. 2011;16(3):377–84. 10.1080/10848770.2011.57560. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2011;21(2):152–69. 10.1017/S0959259810000420. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eggerman M, Panter-Brick C. Suffering, hope and entrapment: resilience and cultural values in Afghanistan. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):71–83. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chan SM, Bowes J, Wyver S. Chinese parenting in Hong Kong: links among goals, beliefs and styles. Early Child Dev Care. 2009;179(7):849–62. 10.1080/03004430701536525. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fung J, Kim JJ, Jin J, Wu Q, Fang C, Lau AS. Perceived social change, parental control, and family relations: a comparison of Chinese families in Hong Kong, Mainland China, and the United States. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1671. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freedman M. The family in China, past and present. Pac Aff. 1961;34(4):323–36. 10.2307/2752626. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hwang KK, Chang J. Self-cultivation: culturally sensitive psychotherapies in Confucian societies. Couns Psychol. 2009;37(7):1010–32. 10.1177/0011000009339976. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strom RD, Strom SK, Xie Q. Parent expectations in China. Int J Sociol Fam. 1996;26(1):37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedlmeier W, Corapci F, Cole PM. Emotion socialization in cross-cultural perspective. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5(7):410–27. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00362.x. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soto JA, Perez CR, Kim YH, Lee EA, Minnick MR. Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European Americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion. 2011;11(6):1450. 10.1037/a0023340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao J, Chapman E, Houghton S. Key predictive factors in the mental health of Chinese university students at home and abroad. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23): 16103. 10.3390/ijerph192316103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.