Abstract

Naphtho[2,1-b]thiophene (NTH) is an asymmetric structural isomer of dibenzothiophene (DBT), and in addition to DBT derivatives, NTH derivatives can also be detected in diesel oil following hydrodesulfurization treatment. Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R was newly isolated from soil for its ability to grow in a medium with NTH as the sole source of sulfur, and growing cells of WU-K2R degraded 0.27 mM NTH within 7 days. WU-K2R could also grow in the medium with NTH sulfone, benzothiophene (BTH), 3-methyl-BTH, or 5-methyl-BTH as the sole source of sulfur but could not utilize DBT, DBT sulfone, or 4,6-dimethyl-DBT. On the other hand, WU-K2R did not utilize NTH or BTH as the sole source of carbon. By gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis, desulfurized NTH metabolites were identified as NTH sulfone, 2′-hydroxynaphthylethene, and naphtho[2,1-b]furan. Moreover, since desulfurized BTH metabolites were identified as BTH sulfone, benzo[c][1,2]oxathiin S-oxide, benzo[c][1,2]oxathiin S,S-dioxide, o-hydroxystyrene, 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)ethan-1-al, and benzofuran, it was concluded that WU-K2R desulfurized NTH and BTH through the sulfur-specific degradation pathways with the selective cleavage of carbon-sulfur bonds. Therefore, Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R, which could preferentially desulfurize asymmetric heterocyclic sulfur compounds such as NTH and BTH through the sulfur-specific degradation pathways, is a unique desulfurizing biocatalyst showing properties different from those of DBT-desulfurizing bacteria.

Sulfur oxides generated by combustion of fossil fuel lead to acid rain and air pollution. Therefore, today petroleum is treated by hydrodesulfurization (HDS) using metallic catalysts in the presence of hydrogen gas under extremely high temperature and pressure. Although HDS can remove various types of sulfur compounds, some types of heterocyclic sulfur compounds cannot be removed. Dibenzothiophene (DBT) is one such recalcitrant organosulfur compound and is widely recognized as a model target compound for deeper desulfurization, since DBT derivatives can be detected in diesel oil following HDS treatment. Therefore, the application of a biodesulfurization process using a DBT-desulfurizing microorganism following HDS, mainly for diesel oil, has attracted attention for achievement of deeper desulfurization (16, 20). Some mesophilic and thermophilic DBT-desulfurizing microorganisms have been isolated, for example, Rhodococcus sp. strain IGTS8 (1, 4, 21, 22), Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1 (8), R. erythropolis H-2 (17, 18), R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 (6), and Paenibacillus sp. strain A11-2, which desulfurizes DBT at 60°C (7, 11). We have also isolated Bacillus subtilis WU-S2B (9) and Mycobacterium phlei WU-F1 (2), which could desulfurize DBT and its derivatives over a wide temperature range of 20 to 50°C and at the highest level at 45 to 50°C. These bacteria desulfurize DBT through the sulfur-specific degradation pathway with the selective cleavage of carbon-sulfur (C-S) bonds without reducing the energy content (4, 21, 22).

Naphtho[2,1-b]thiophene (NTH) (see Fig. 3B), which includes a benzothiophene (BTH) (see Fig. 3A) structure, is an asymmetric structural isomer of DBT. Recently it has become apparent that in addition to DBT derivatives, NTH derivatives can also be detected in diesel oil following HDS treatment, although NTH derivatives are minor components in comparison with DBT derivatives (unpublished data). Therefore, NTH may also be a model target compound for deeper desulfurization. Kropp et al. (13) have reported that Pseudomonas sp. strain W1 could degrade NTH. However, this bacterium utilized NTH as the carbon source with reducing the energy content, and the sulfur atom was not removed from NTH during the degradation. On the other hand, we recently reported that M. phlei WU-F1, which possessed high desulfurizing ability toward DBT and its derivatives under high-temperature conditions, could also desulfurize NTH and 2-ethyl-NTH through the sulfur-specific degradation pathway (3). There is no other report related to NTH biodesulfurization through the sulfur-specific degradation pathway. Thus, for practical biodesulfurization, it may be useful to obtain microorganisms preferentially desulfurizing asymmetric heterocyclic sulfur compounds such as NTH and BTH.

FIG. 3.

Proposed pathways of BTH (A) and NTH (B) desulfurization by Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R. Compounds in brackets, that is, HPESi in panel A and 2-(2′-hydroxynaphthyl)ethen-1-sulfinate (HNESi) and 2-(2′-hydroxynaphthyl)ethan-1-al (HNEal) in panel B were not identified and are indicated as postulated metabolites. Ring numbering of BTH and NTH is also shown. The dotted arrow in panel A indicates that BFU might be produced via HPEal from BcOTO2 (see text).

In this paper, we describe the desulfurization of NTH and BTH by the newly isolated strain Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R. We examined the desulfurizing ability of WU-K2R toward heterocyclic sulfur compounds and found that WU-K2R could preferentially desulfurize asymmetric NTH and BTH. Moreover, we analyzed metabolites produced through NTH and BTH desulfurization by WU-K2R in order to propose sulfur-specific degradation pathways with selective cleavage of C-S bonds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and cultivation of NTH-desulfurizing microorganisms.

Isolation and cultivation were performed using MG medium, which is A medium (8) with some modifications as follows; 5.0 g of glucose, 1.0 g of NH4Cl, 2.0 g of KH2PO4, 4.0 g of K2HPO4, 0.2 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 10 ml of metal solution (9), and 1.0 ml of vitamin mixture (9) in 1,000 ml of distilled water (pH 7.0). The medium was supplemented with 0.27 mM (50 ppm) NTH or each heterocyclic sulfur compound, i.e., NTH sulfone (NTHO2), BTH, 3-methyl-BTH, 5-methyl-BTH, DBT, DBT sulfone (DBTO2), and 4,6-dimethyl-DBT, as the sole source of sulfur. To suspend heterocyclic sulfur compounds in the medium, 1% (vol/vol) ethanol or N,N-dimethylformamide was added. Cultivation was done at 30°C with reciprocal shaking at 240 strokes per min in test tubes (18 by 180 mm) containing 5 ml of the medium supplemented with NTH or each heterocyclic sulfur compound and ethanol or N,N-dimethylformamide. Single-colony isolation from turbid cultures was performed by plating appropriately diluted culture samples onto Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, composed of 10 g of Bacto Tryptone (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), 5 g of yeast extract (Difco), and 10 g of NaCl in 1,000 ml of distilled water (pH 7.0) supplemented with 15 g of Bacto Agar (Difco). Microorganisms isolated were stored in microtubes containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol at −80°C.

Analytical methods.

Cell growth was measured turbidimetrically at 660 nm. NTH, NTHO2, BTH, 3-methyl-BTH, 5-methyl-BTH, DBT, DBTO2, and 4,6-dimethyl-DBT were determined by using high-performance liquid chromatography (type LC-10A; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Puresil C18 column (Waters, Milford, Mass.). The mobile phase was acetonitrile-water (1:1, vol/vol) or acetonitrile-tetrahydrofuran-water (1:1:3, vol/vol/vol), and the flow rate was 1.0 ml/min. The culture broth (5 ml) was acidified to pH 2.0 with 6 M HCl and extracted with 4 ml of ethyl acetate. The extract was filtered through a 0.20-μm-pore-size polytetrafluoroethylene membrane filter (Advantec Toyo, Tokyo, Japan) for high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Compounds were detected spectrophotometrically at 254 nm, and the amounts of NTH and other heterocyclic sulfur compounds were calculated from standard calibration curves. The molecular structures of metabolites produced through NTH and BTH desulfurization were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (type 5890II; Hewlett-Packard, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) equipped with a 30-m type HP-5 column (Hewlett-Packard). The carrier gas was helium, and the flow rate was 1.0 ml/min. The injection temperature was maintained at 280°C. The oven temperature was programmed to start at 40°C, which was held for 3 min, and increase to a final temperature of 280°C at a rate of 10°C/min. The combined extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, evaporated, and redissolved in ethyl acetate for GC-MS analysis.

Chemicals.

BTH (with a purity exceeding 97%) and DBT (98%) were purchased from Tokyo Kasei (Tokyo, Japan). 3-Methyl-BTH (95%) and 5-methyl-BTH (96%) were purchased from Lancaster (Windham, N.H.). DBTO2 (97%) was purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, Wis.). Benzofuran (BFU) (95%) was purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). NTH (99%), NTHO2 (90%), 4,6-dimethyl-DBT (99%), and naphtho[2,1-b]furan (NFU) (99%) were kindly supplied by the laboratory of the Japan Cooperation Center, Petroleum (Shizuoka, Japan). The purity of NTHO2 was slightly low, but no sulfur compound except for NTHO2 was detected in the reagent. All other reagents were of analytical grade and commercially available.

RESULTS

Identification of an NTH-desulfurizing bacterium, WU-K2R.

To isolate NTH-desulfurizing microorganisms, approximately 1,000 samples of soil, waste water, and oil sludge in Japan were collected as sources of microorganisms. A small amount of each sample was suspended in distilled water at an appropriate concentration, and 0.2 ml of this suspension was inoculated into a test tube containing 5 ml of MG medium with NTH and cultivated at 30°C for 3 to 5 days. Aliquots of some turbid cultures were then transferred into fresh medium. After five subcultivations, the culture broth was appropriately diluted with distilled water and spread onto LB medium agar plates. After cultivation at 30°C for 3 to 5 days, colonies formed on the plates were again inoculated into liquid MG medium with NTH. By means of repeated cultivation in liquid MG medium and single-colony isolation on LB medium agar plates, strains showing an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of more than 1.0 in MG medium with NTH within 7 days were selected. Among the strains, one bacterium (WU-K2R) derived from soil, which showed stable growth in the medium with NTH as the sole source of sulfur, was chosen for further studies.

WU-K2R was a rod-shaped bacterium with dimensions of 0.5 to 1.0 μm by 1.5 to 2.0 μm. This strain was gram positive, catalase positive, and oxidase negative and did not form spores. Further taxonomical identification of WU-K2R was performed by the National Collection of Industrial and Marine Bacteria Japan Ltd. (Shizuoka, Japan), and the 16S ribosomal DNA sequence of WU-K2R was found to have 99.9% identity to those of Rhodococcus sp. strain DSM43943 (accession number X80616), Rhodococcus opacus 1CP (accession number Y11893), and Rhodococcus koreensis (accession number AF124343). From these results, WU-K2R was tentatively identified as a Rhodococcus sp.

Growth characteristics of Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R.

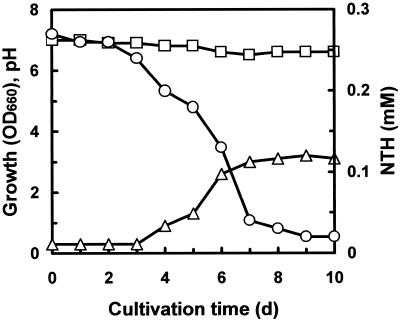

Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R grew in MG medium with NTH as the sole source of sulfur. The time course of NTH degradation by growing cells of Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R is shown in Fig. 1, and WU-K2R degraded 0.27 mM NTH within 7 days. On the other hand, it was confirmed that WU-K2R did not utilize NTH or BTH as the sole source of carbon or of carbon and sulfur (data not shown). Moreover, WU-K2R did not grow with NFU or BFU as the sole source of carbon; WU-K2R did not grow even in MG medium including 5 g of glucose per liter with Na2SO4 and 0.25 g of NFU or BFU per liter, indicating that these compounds were toxic to this bacterium for growth.

FIG. 1.

Time course of NTH degradation by growing cells of Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R. WU-K2R was cultivated in MG medium with 0.27 mM NTH as the sole source of sulfur and 1% (vol/vol) N,N-dimethylformamide. Symbols: ▵, growth (OD660); □, pH; ○, NTH.

Desulfurization of heterocyclic sulfur compounds.

The growth of Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R on each heterocyclic sulfur compound was examined. As shown in Table 1, WU-K2R showed growth in MG medium with NTHO2, as well as NTH, as the sole source of sulfur and degraded 97% of 0.27 mM NTHO2 within 5 days. Moreover, WU-K2R could grow with BTH, 3-methyl-BTH, and 5-methyl-BTH. Since BTH, 3-methyl-BTH, and 5-methyl-BTH are volatile, test tubes were tightly sealed to restrict admission of air. Under these conditions, growth occurred with BTH only and none was observed with the methylated BTHs (data not shown). However, WU-K2R could grow with the alkylated compounds when silicone caps which freely admitted air were used (Table 1). When NTH and BTH were simultaneously provided for WU-K2R, the bacterium degraded 9 and 59% of each substrate at 0.27 mM, respectively, within 5 days. On the other hand, WU-K2R did not utilize DBT, DBTO2, or 4,6-dimethyl-DBT as the sole source of sulfur.

TABLE 1.

Degradation of heterocyclic sulfur compounds by growing cells of Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2Ra

| Sulfur source | Growth (OD660)b | Degradation (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No substrate | 0.0 | |

| NTH | 4.3 | 80 |

| NTHO2 | 2.3 | 97 |

| BTH | 2.0 | 57 |

| 3-Methyl-BTH | 0.3 | NDc |

| 5-Methyl-BTH | 1.0 | ND |

| DBT | 0.1 | 0 |

| DBTO2 | 0.1 | 0 |

| 4,6-Dimethyl-DBT | 0.1 | 0 |

WU-K2R was cultivated in MG medium with a 0.27 mM concentration of each heterocyclic sulfur compound as the sole source of sulfur and 1% (vol/vol) ethanol.

The OD660s of 0.1 were due to insoluble DBT, DBTO2, or 4,6-dimethyl-DBT itself in the medium but were not due to the growth of WU-K2R; no growth of WU-K2R was confirmed by microscopic observation.

ND, not determined.

NTH- and BTH-desulfurizing pathways.

Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R was cultivated to the end of exponential growth phase in MG medium with NTH or BTH as the sole source of sulfur, and each culture broth was extracted with ethyl acetate. First, the extract containing metabolites produced through NTH desulfurization was analyzed by GC-MS. As shown in Fig. 2, three compounds were detected as metabolites, in addition to NTH (M+, m/z = 184) (Fig. 2A). One metabolite was identified as NTHO2 (M+, m/z = 216) (Fig. 2B), since its GC-MS spectrum was identical to that of authentic NTHO2. The other metabolites were considered to include no sulfur atom in their molecular structures. One was identified as 2′-hydroxynaphthylethene (HNE) (M+, m/z =170) (Fig. 2C). The fragment ion at m/z = 141 corresponds to loss of the vinyl group from the molecular ion. The other was identified as NFU (M+, m/z =168) (Fig. 2D), since its GC-MS spectrum was identical to that of authentic NFU.

FIG. 2.

GC-MS analysis of desulfurized NTH metabolites produced by Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R. (A) NTH; (B) NTHO2; (C) HNE; (D) NFU.

The extract containing metabolites produced through BTH desulfurization was also analyzed by GC-MS. As shown in Table 2, six compounds were detected as metabolites in addition to BTH (M+, m/z = 134). These six metabolites were identified as BTH sulfone (BTHO2) (M+, m/z = 166), benzo[c][1,2]oxathiin S-oxide (BcOTO) (M+, m/z = 166), benzo[c][1,2]oxathiin S,S-dioxide (BcOTO2) (M+, m/z = 182), o-hydroxystyrene (M+, m/z = 120), 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)ethan-1-al (HPEal) (M+, m/z = 136), and BFU (M+, m/z = 118), since the GC-MS spectra of these metabolites were identical to those reported by other researchers who analyzed desulfurized BTH metabolites in detail (5, 12).

TABLE 2.

GC-MS analysis of desulfurized BTH metabolites produced by Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R

| Metabolite | Fragment ions (m/z) |

|---|---|

| BTH | 134 (M+), 89, 67, 63 |

| BTHO2 | 137, 109, 166 (M+), 63, 76, 118, 89 |

| BcOTO | 118, 89, 166 (M+), 63 |

| BcOTO2 | 89, 118, 182 (M+), 63 |

| o-Hydroxystyrene | 91, 120 (M+), 69, 66 |

| HPEal | 107, 136 (M+), 77, 51, 89, 63 |

| BFU | 118 (M+), 89, 63 |

On the other hand, desulfurized NTH and BTH metabolites were not detected when WU-K2R was cultivated in MG medium with Na2SO4 instead of NTH or BTH as the sole source of sulfur (data not shown). Based on the deduced structures of these metabolites and BTH-desulfurizing pathways previously reported (5, 12), the pathways for NTH and BTH desulfurization by WU-K2R shown in Fig. 3 were proposed. It was concluded that WU-K2R desulfurized NTH and BTH through sulfur-specific degradation pathways with selective cleavage of C-S bonds.

DISCUSSION

In addition to symmetric DBT derivatives, asymmetric heterocyclic sulfur compounds such as NTH and BTH derivatives can also be detected in diesel oil following HDS treatment. Some microorganisms showing BTH-desulfurizing ability have been isolated, for example, Gordonia sp. strain 213E (5), Rhodococcus sp. strain T09 (15), and Paenibacillus sp. strain A11-2 (12). These bacteria desulfurize BTH through sulfur-specific degradation pathways. Gordonia sp. strain 213E and Rhodococcus sp. strain T09 could desulfurize BTH but not DBT. On the other hand, Paenibacillus sp. strain A11-2 could also desulfurize DBT in addition to BTH, since this bacterium was isolated for its ability to grow in a medium with DBT as the sole source of sulfur. However, it is interesting that the DBT-desulfurizing bacterium R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 could desulfurize alkylated BTH but not BTH (10). On the other hand, for NTH biodesulfurization through the sulfur-specific degradation pathway, there is no report except for our recent publication (3). In that paper, we reported that M. phlei WU-F1, which possessed high desulfurizing ability toward DBT and its derivatives under high-temperature conditions, could also desulfurize NTH and 2-ethyl-NTH through the sulfur-specific degradation pathway (3). However, as described below, the NTH-desulfurizing pathways of M. phlei WU-F1 and Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R (shown in this paper) are considered to be different.

In this paper, we have described the isolation of the NTH-desulfurizing bacterium Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R and characterization of desulfurization patterns for NTH and BTH. The 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of WU-K2R and, surprisingly, Rhodococcus sp. strain T09 (desulfurizing BTH [15]) were found to show 99.9% identity to that of Rhodococcus sp. strain DSM43943 (accession number X80616), but strain T09 was confirmed to show no NTH-desulfurizing ability in a medium with NTH as the sole source of sulfur, in which WU-K2R showed the ability (data not shown). Therefore, Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R is concluded to be a different type of desulfurizing bacterium than strain T09.

As shown in Table 1, Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R degraded 80% of 0.27 mM NTH within 5 days, and WU-K2R showed much higher NTH-desulfurizing activity than M. phlei WU-F1, since WU-F1 degraded only 39% of 0.27 mM NTH within 5 days (3). WU-K2R exhibited faster growth and a higher NTH degradation rate in the presence of ethanol (Table 1) than in the presence of dimethylformamide (Fig. 1). This might be related to the fact that WU-K2R could utilize ethanol but not dimethylformamide as the sole source of carbon (data not shown). WU-K2R also degraded NTHO2, suggesting that this bacterium desulfurized NTH via NTHO2, as shown in Fig. 3B. Moreover, WU-K2R could grow with BTH, 3-methyl-BTH, and 5-methyl-BTH when silicone caps which freely admitted air were used (Table 1), but with tightly sealed caps restricting admission of air, growth occurred with BTH only and none was observed for the methylated BTHs (data not shown). These results suggest that WU-K2R might require more O2 to utilize the alkylated compounds.

On the other hand, WU-K2R did not utilize DBT, DBTO2, or 4,6-dimethyl-DBT as the sole source of sulfur. Therefore, WU-K2R is considered to preferentially desulfurize asymmetric heterocyclic sulfur compounds such as NTH and BTH rather than symmetric DBT derivatives.

BTH-desulfurizing bacteria reported by other researchers desulfurized BTH through the sulfur-specific degradation pathways (5, 12), in which BTH was first oxidized to BTHO2 via BTH sulfoxide. BTHO2 was then transformed to 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)ethen-1-sulfinate (HPESi), leading to BcOTO and BcOTO2 through dehydration. HPESi was finally desulfurized to HPEal, leading to BFU through dehydration, by Gordonia sp. strain 213E (5) and Rhodococcus sp. strain T09 (15), which could desulfurize BTH but not DBT. On the other hand, HPESi was finally desulfurized to o-hydroxystyrene by Paenibacillus sp. strain A11-2 (12), which could desulfurize both BTH and DBT. In the present study, it was confirmed that Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R desulfurized BTH through the sulfur-specific degradation pathway as shown in Fig. 3A. Moreover, since both BFU and o-hydroxystyrene were detected as metabolites with no sulfur atom (Table 2), WU-K2R is considered to possess two types of C-S bond cleavage reactions toward HPESi. In addition, BFU might be produced via HPEal from BcOTO2, as the case of DBT desulfurization, in which DBTO2 monooxygenase also recognizes dibenz[c,e][1,2]oxathiin S,S-dioxide as a substrate to produce 2,2′-dihydroxybiphenyl (19, 21). Similarly, since metabolites from NTH without sulfur were identified as NFU and HNE, it was confirmed that WU-K2R desulfurized NTH through the same pathway (or quite similar one) as that for BTH, as shown in Fig 3B. On the other hand, it was suggested that M. phlei WU-F1 (3) produced only the compounds corresponding to HNE and not those corresponding to NFU as metabolites from 2-ethyl-NTH without sulfur. Therefore, the NTH-desulfurizing pathway of WU-K2R is considered to be different from that of M. phlei WU-F1. In the NTH-desulfurizing pathway of WU-K2R, desulfurized NTH metabolites corresponding to desulfurized BTH metabolites such as BcOTO, BcOTO2, and HPEal were not detected by GC-MS analysis, and the total amount of desulfurized NTH metabolites detected was much lower than that of degraded NTH (data not shown). Although we do not have a clear explanation for this, it might be due to the lability of desulfurized NTH metabolites (3) or the existence of an additional degradation pathway(s) for NTH (14). However, since desulfurized NTH metabolites were not detected when WU-K2R was cultivated in MG medium with Na2SO4 instead of NTH as the sole source of sulfur (data not shown), these metabolites (Fig. 2) were derived from NTH, indicating that the pathway shown in Fig. 3B clearly contributes to NTH desulfurization by WU-K2R.

In conclusion, we confirmed that the newly isolated strain Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R could preferentially desulfurize asymmetric heterocyclic sulfur compounds such as NTH and BTH through sulfur-specific degradation pathways. Therefore, for practical biodesulfurization, WU-K2R may be a useful desulfurizing biocatalyst complementary to microorganisms showing desulfuring ability toward symmetric DBT derivatives. However, we still do not know the detailed reaction mechanisms and the enzymes related to the reaction steps. Therefore, we are investigating the enzymatic and genetic properties of this NTH-desulfurizing bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. strain WU-K2R.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Japan Cooperation Center, Petroleum (JCCP), subsidized by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (13650859) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Denome, S. A., C. Oldfield, L. J. Nash, and K. D. Young. 1994. Characterization of the desulfurization genes from Rhodococcus sp. strain IGTS8. J. Bacteriol. 176:6707-6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuya, T., K. Kirimura, K. Kino, and S. Usami. 2001. Thermophilic biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene and its derivatives by Mycobacterium phlei WU-F1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 204:129-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furuya, T., K. Kirimura, K. Kino, and S. Usami. 2001. Thermophilic biodesulfurization of naphthothiophene and 2-ethylnaphthothiophene by dibenzothiophene-desulfurizing bacterium, Mycobacterium phlei WU-F1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:237-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher, J. R., E. S. Olson, and D. C. Stanley. 1993. Microbial desulfurization of dibenzothiophene: a sulfur specific pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 107:31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert, S. C., J. Morton, S. Buchanan, C. Oldfield, and A. McRoberts. 1998. Isolation of a unique benzothiophene-desulphurizing bacterium, Gordona sp. strain 213E (NCIMB 40816), and characterization of the desulphurization pathway. Microbiology 144: 2545-2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii, Y., M. Kobayashi, J. Konishi, T. Onaka, K. Okumura, and M. Suzuki. 1998. Desulfurization of petroleum by the use of biotechnology. Nippon Kagaku Kaishi 1998:373-381. (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii, Y., J. Konishi, H. Okada, K. Hirasawa, T. Onaka, and M. Suzuki. 2000. Operon structure and functional analysis of the genes encoding thermophilic desulfurizing enzymes of Paenibacillus sp. A11-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izumi, Y., T. Ohshiro, H. Ogino, Y. Hine, and M. Shimao. 1994. Selective desulfurization of dibenzothiophene by Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:223-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirimura, K., T. Furuya, Y. Nishii, Y. Ishii, K. Kino, and S. Usami. 2001. Biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene and its derivatives through the selective cleavage of carbon-sulfur bonds by a moderately thermophilic bacterium Bacillus subtilis WU-S2B. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 91:262-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi, M., T. Onaka, Y. Ishii, J. Konishi, M. Takaki, H. Okada, Y. Ohta, K. Koizumi, and M. Suzuki. 2000. Desulfurization of alkylated forms of both dibenzothiophene and benzothiophene by a single bacterial strain. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konishi, J., Y. Ishii, T. Onaka, K. Okumura, and M. Suzuki. 1997. Thermophilic carbon-sulfur-bond-targeted biodesulfurization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3164-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konishi, J., T. Onaka, Y. Ishii, and M. Suzuki. 2000. Demonstration of the carbon-sulfur bond targeted desulfurization of benzothiophene by thermophilic Paenibacillus sp. strain A11-2 capable of desulfurizing dibenzothiophene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187:151-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kropp, K. G., J. T. Andersson, and P. M. Fedorak. 1997. Bacterial transformations of naphthothiophenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3463-3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kropp, K. G., and P. M. Fedorak. 1998. A review of the occurrence, toxicity, and biodegradation of condensed thiophenes found in petroleum. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:605-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsui, T., T. Onaka, Y. Tanaka, T. Tezuka, M. Suzuki, and R. Kurane. 2000. Alkylated benzothiophene desulfurization by Rhodococcus sp. strain T09. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:596-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monticello, D. J. 2000. Biodesulfurization and the upgrading of petroleum distillates. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:540-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohshiro, T., T. Hirata, and Y. Izumi. 1995. Microbial desulfurization of dibenzothiophene in the presence of hydrocarbon. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44:249-252. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohshiro, T., T. Hirata, and Y. Izumi. 1996. Desulfurization of dibenzothiophene derivatives by whole cells of Rhodococcus erythropolis H-2. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 142:65-70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohshiro, T., T. Kojima, K. Torii, H. Kawasoe, and Y. Izumi. 1999. Purification and characterization of dibenzothiophene (DBT) sulfone monooxygenase, an enzyme involved in DBT desulfurization, from Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 88:610-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohshiro, T., and Y. Izumi. 1999. Microbial desulfurization of organic sulfur compounds in petroleum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oldfield, C., O. Pogrebinsky, J. Simmonds, E. S. Olson, and C. F. Kulpa. 1997. Elucidation of the metabolic pathway for dibenzothiophene desulfurization by Rhodococcus sp. IGTS8 (ATCC53968). Microbiology 143:2961-2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson, E. S., D. C. Stanley, and J. R. Gallagher. 1993. Characterization of intermediates in the microbial desulfurization of dibenzothiophene. Energy Fuels 7:159-164. [Google Scholar]