Abstract

Psychosocial interventions for bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs) often recommend limiting caffeine intake, yet few studies have examined whether caffeine intake differentially affects mood and whether sleep disruption is a key mechanism underlying these effects. The goals of this study were to investigate concurrent and prospective relationships between caffeine intake, sleep, and mood symptoms among individuals with and without BSD and test a mechanism whereby caffeine intake prospectively predicts mood symptoms via its impact on sleep duration. Participants with and without BSD completed a 20-day ecological momentary assessment protocol, reporting daily caffeine consumption and mood symptoms via smartphone, and wearing wrist actigraphs to objectively measure sleep. Multilevel models revealed that on days when individuals consumed more caffeine than usual, they reported lower same-day depressive symptoms and higher same-day hypomanic symptoms, even after accounting for sleep duration. Multilevel mediation models indicated that caffeine intake was associated with increased next-day depressive symptoms, and this effect was partially mediated by shorter sleep duration. Caffeine intake also predicted higher next-day hypomanic symptoms indirectly through shorter sleep duration, though the direct effect of caffeine intake on hypomanic symptoms was not significant—consistent with full mediation. Diagnostic status did not moderate any of the findings. These findings suggest that caffeine has dynamic, time-dependent effects on mood, providing short-term mood benefits while contributing to next-day mood disruption through its impact on sleep duration. There was no evidence that caffeine intake has more deleterious mood effects for individuals with BSD relative to those without BSD.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, depression, caffeine, sleep, ecological momentary assessment, actigraphy

1. Introduction

Bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs) are mood disorders characterized by periods of depressed and elevated mood. With a lifetime prevalence rate of 6.4%, BSDs are associated with marked impairment and comorbidity (Judd & Akiskal, 2003). Indeed, individuals with BSD have reduced life expectancy due to both suicide and medical complications (Kessing et al., 2015). Sleep disturbances are recognized as a core feature of BSD (Gold & Sylvia, 2016), and it has been suggested that sleep deprivation (i.e., shorter overnight sleep duration) may increase risk for negative mental health outcomes (Harvey et al., 2009).

Current best practices indicate that a combination of medication and psychotherapy is most effective for improving the course of illness and preventing relapse during the maintenance phase of treatment (Parikh et al., 2015; Yatham et al., 2018). Although most treatments target the reduction and prevention of manic and depressive episodes, inter-episode mood symptoms also are impairing and tend to be more severe among individuals with a greater number of prior lifetime mood episodes (Perlis et al., 2006). During these inter-episode periods, psychosocial interventions for BSDs include psychoeducation about behaviors thought to decrease the likelihood of relapse, including the development of healthy lifestyle habits (Smith et al., 2010).

One such healthy lifestyle recommendation is reducing psychoactive stimulant usage, such as caffeine (Yatham et al., 2018). In the general population, moderate caffeine intake has been associated with a variety of positive health outcomes (Poole et al., 2017). As an adenosine receptor antagonist, caffeine may impact individuals with BSDs differentially (López-Cruz et al., 2018). For instance, caffeine can cause sleep disturbance, which is a core feature of BSD that has been linked to the onset of mood episodes (Colombo et al., 1999). Behaviorally, the effects of caffeine appear similar to symptoms of mania (e.g., pressured speech, increased energy, psychomotor disturbances). Moreover, several case reports found evidence that caffeine induced manic symptoms and even triggered the onset of BSD (Wang et al., 2015). However, there is a paucity of rigorous empirical research investigating the relationship between caffeine intake and mood symptoms among individuals with BSD.

A recent meta-analysis identified seventeen studies that examined the association between caffeine and mood symptoms in bipolar disorder, but almost all were case studies or cross-sectional studies (Frigerio et al., 2021). The authors stated that based on the available evidence, findings were inconclusive and suggested prospective studies may provide more insight into these relationships (Frigerio et al., 2021). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a particularly promising approach for studying the relationship between caffeine consumption and affect due to its ability to examine granular day-to-day associations in real time. Paired with actigraphy, these methods also can be used to test mechanistic pathways involving objectively measured sleep.

Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent among people with BSD, even among euthymic individuals. Indeed, individuals with remitted BSD (inter-episode) have longer sleep onset latency and greater sleep duration variability (Harvey et al., 2005; Millar et al., 2004), and poor sleep quality is a known predictor of negative mood states (Triantafillou et al., 2019). In addition, there are also differences in the sleep characteristics of euthymic individuals with BSD in that they tend to have longer total sleep time and time in bed (Ng et al., 2015), which is notable because an inverse relationship between sleep duration and next-day depressive symptoms has been observed (Titone et al., 2022). Taken together, it is important to consider whether potential associations between caffeine intake and mood in BSD may be influenced by sleep disturbances, insofar as increased caffeine consumption has been linked to longer sleep onset latency and reduced sleep duration (Clark & Landolt, 2017).

Study Aims

This investigation involved a secondary data analysis of an EMA study and aimed to investigate concurrent (same-day) and prospective (next day) relationships between caffeine consumption and mood symptoms (i.e., hypo/manic and depressive symptoms) among young adults with and without BSD. In line with prior research, we hypothesized that caffeine consumption would be negatively associated with depressive symptoms and positively associated with hypo/manic symptoms in main effects models. In light of the observation that caffeine may have a differential impact on individuals with BSD and contribute to mood destabilization, we also conducted moderation analyses to investigate whether the strength of the associations differed based on diagnostic status. We hypothesized that there would be a positive association between caffeine and depressive symptoms and a stronger positive association between caffeine and hypo/manic symptoms for individuals with BSD relative to those without BSD. A second aim was to evaluate a potential mechanism whereby sleep disturbances mediated the association between caffeine consumption and mood symptoms. Sleep onset latency and sleep duration were considered as potential mediators.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample was a subset of young adults (n=150) previously enrolled in a longitudinal study of the onset and course of BSD, the Teen Emotion and Motivation Study (TEAM; Alloy, Urošević, et al., 2012) Participants originally were screened for participation in TEAM using two self-report measures of trait reward sensitivity: the Behavioral Activation System subscale (BAS) of the Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System (BIS/BAS) Scales and Sensitivity to Reward (SR) subscale of the Sensitivity to Punishment/Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ; see below for details). To be eligible for TEAM, individuals had to have either moderate reward sensitivity (40-60th percentile on both subscales) or high reward sensitivity (85-99th percentile on both subscales), and no history of a lifetime BSD, manic or hypomanic episode, or psychosis, as determined by a structured diagnostic interview. In line with the reward hypersensitivity theory of BSD, empirical work has shown that individuals with high reward sensitivity are at increased risk for developing BSD compared to those with moderate reward sensitivity (Alloy et al., 2016; Alloy, Bender, et al., 2012). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Temple University (approval number 20655).

The present study used a two-group design based on diagnostic status at the start of the EMA study: individuals without BSD and individuals from the high-risk group who developed BSD while participating in Project TEAM. A random subset of previous Project TEAM participants was invited to complete this 20-day EMA study, with efforts taken to ensure approximately one-third was from each of the Project TEAM groups of interest: individuals diagnosed with BSD, individuals with moderate reward sensitivity, and individuals with reward hypersensitivity. For the purposes of this study, the moderate and high reward groups were combined. The current study took place several years (M = 2.85y, SD = 2.48y) after initial enrollment in Project TEAM, and at the time of the current study, participants were between the ages 18-27.

2.2. Procedure

For 20 days, participants reported depressive and manic symptoms three times daily via smartphone survey. Participants were prompted randomly within three four-hour blocks, once in the morning, in the afternoon, and in the evening. Caffeine consumption was reported at the end of each day via smartphone survey prompt. Participants also continuously wore a wrist actigraph to measure sleep.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Reward Sensitivity Measures

The Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System Scales (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994) and the Sensitivity to Punishment Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ; Torrubia et al., 2001) are two self-report measures of reward sensitivity. The BIS/BAS measures sensitivity to rewards (e.g., behavioral approach; BAS subscale) and punishments (behavioral inhibition; BIS subscale) and includes 20-items scored on a four-point Likert scale. The BAS had high internal consistency (α=0.80) in the Project TEAM sample and the initial validation (Carver & White, 1994). The SPSRQ is a 48-item measure with two subscales, sensitivity to punishments (SP) and rewards (SR). The SR scale’s internal consistency was α=.76.

2.3.2. Mood Symptom Measures

During the EMA period, depressive symptoms were assessed on a 1-4 Likert scale using four questions from the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a common self-report questionnaire (Beck et al., 1996). The BDI-II items selected for use in the EMA questionnaire were items 1, 2, 7, and 15, which assess low mood, hopelessness, low self-esteem, and loss of energy. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM) was used to assess manic symptoms (Altman et al., 1997). Participants answered five self-report questions on a 1-5 Likert scale. Responses from the three daily surveys were averaged to create a daily composite score of each type of symptoms.

2.3.3. Structured Diagnostic Interview

The expanded Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime (exp-SADS-L; Alloy et al., 2008; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978) was used to determine psychiatric diagnoses at baseline and regular six-month follow ups of Project TEAM (the umbrella study the participants were recruited from). This measure has strong interrater reliability (κ>.96; Alloy et al., 2008)

2.3.4. Sleep Parameters

Participants wore an Actiwatch Spectrum (Philips Healthcare, Bend, OR) on their nondominant wrist to measure sleep/wake parameters continuously and noninvasively. Data were reviewed and cleaned manually by trained individuals. Sleep duration and sleep onset latency were calculated using one-minute epochs with proprietary Actiware software (Titone et al., 2020, 2022). Actigraphy, a validated method for measuring sleep, has been correlated with sleep diaries and polysomnography in both clinical and healthy samples (Cole et al., 1992; Kaplan et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2015).

2.3.5. Caffeine Consumption

Each night, participants were asked to report how many cups of coffee, caffeinated sodas, teas, and energy drinks they had consumed that day. Participants were oriented as to what constituted a standard caffeinated beverage (e.g., 8 oz cup of coffee = 1 drink).

2.4. Data Analysis

All EMA surveys with non-missing data on relevant study variables were included in the analysis. Listwise deletion was used to remove observations with insufficient data. A series of multilevel models were estimated to examine cross-sectional (same-day) and prospective (next-day) relationships between caffeine consumption and mood symptoms (both level 1 variables). A model building approach was used in which a random intercept, random slope, and an AR1 autoregressive parameter were tested sequentially. Fit indices were compared to identify the best model fit. The models including a random intercept, slope, and autoregressive parameter were deemed most appropriate because they had the smallest Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

In preliminary analyses, sleep duration, but not sleep onset latency, was associated with caffeine, and therefore, only sleep duration was tested as a covariate and mediator in the following analyses. In the first set of analyses, the focal predictor, caffeine consumption, was separated into its between-person (level 2) and within-person (level 1) components. Interaction models introduced a cross-level interaction and evaluated whether BSD risk group served as a moderator, at both the within- and between-person levels. Step 1 models controlled for sex, age, and race; in step 2 models, past-night sleep duration was added as a covariate, and step 3 included the cross-level interaction term.

In the second set of analyses, multilevel mediation models were used to examine the pathway from caffeine consumption to subsequent mood symptoms via sleep duration. Models were estimated using the “mediation” package in R, and follow-up tests of interaction effects used the MLMed macro for SPSS to determine whether indirect effects differed by BSD diagnostic group. Separate models were conducted for depressive and hypomanic symptoms as outcome variables. Analyses were conducted using the default mediation and MLMed settings, which uses restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation to handle missing data and to provide unbiased parameter estimates. Predictor variables (caffeine intake and sleep duration) were lagged by one unit such that caffeine intake on day 0 predicted changes in sleep duration for the night between days 0 and 1, which in turn, predicted mood symptoms on day 1 (full mediation). Bootstrapped confidence intervals (default setting: 10,000 resamples) were used to test the significance of indirect effects. Moderation effects were assessed using cross-level interaction terms with the level 2 diagnostic status variable. Data are available from the senior author (LBA) upon reasonable request.

3. Results

There was a total of 150 participants: 106 without BSD and 44 with BSD, Mage = 21.90y, SDage = 2.15y. The sample was 59.33% female and 59% non-Hispanic White, 23% non-Hispanic Black, 9% Asian, 5% Hispanic, 3% Multiracial, and 1% Other.

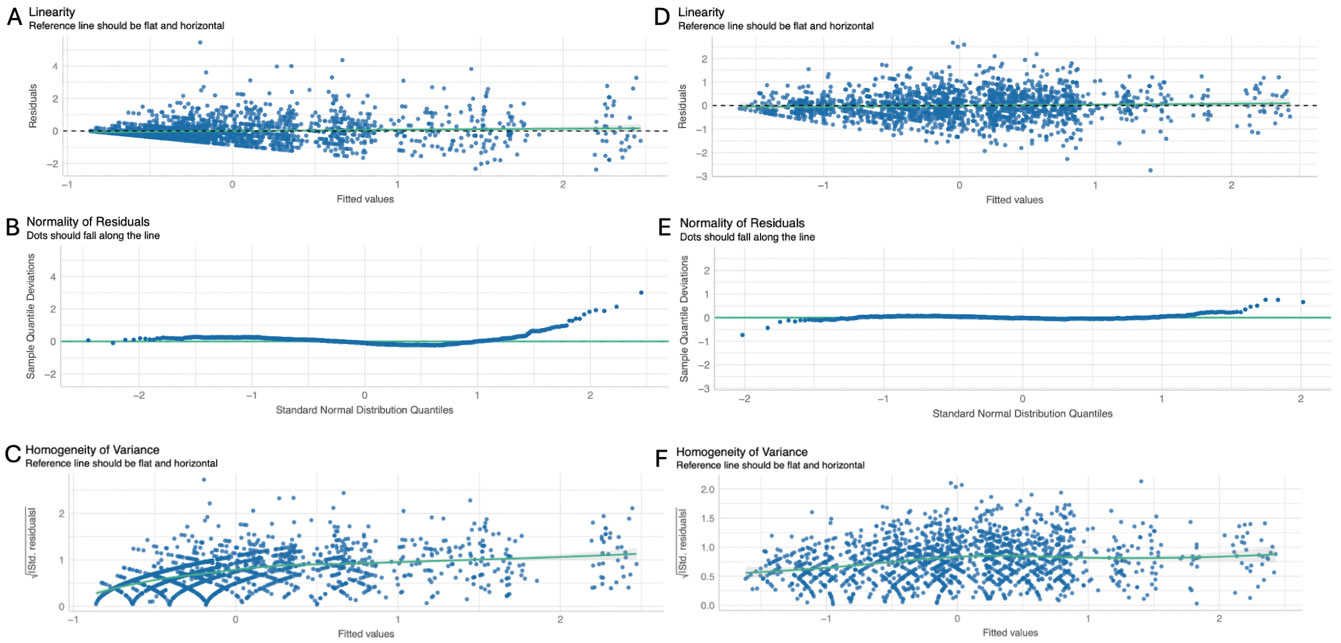

A total of 7,176 observations were recorded across the 20-day protocol nested among 150 participants. On average, each participant contributed data on 15.95 days (SD=4.89; range=1-20). Each day of valid data had an average of approximately 2.67 observations (SD=.38; range=1-3). Only 128 participants completed the actigraphy portion of the study, and thus, the analyses that included sleep (including mediation models) had a sample size of 128, with an average of 14.23 observations per person. Multilevel modeling assumptions were tested for models with either depressive or hypomanic symptoms as the dependent variable; in both cases, the data demonstrated linearity, homoscedasticity of variances, and an approximately normal distribution of residuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multilevel modeling assumptions for models using depressive (A-C) and hypomanic (D-F) symptoms.

Participants reported drinking 4.59 (SD=1.58, range=0-9.2) caffeinated beverages a day on average. Stratified by group, average caffeine consumption was 4.53 (SD=1.65) for those without BSD, and 4.73 (SD=1.42) for those with BSD. The difference was not statistically significant, χ2(1, 149) =0.48, p=0.49. Mean daily hypomanic symptom scores were 2.09 (SD=.50, daily range=1-3.55, observation range=1-5) and mean daily depressive symptom scores were 1.32 (SD=.26, daily range=1-2.24, observation range=1-4).

The cross-sectional and prospective associations between caffeine consumption and depressive symptoms are shown in Table 1. In cross-sectional analyses, before considering the effects of past-night sleep duration (Step 1), there was a significant within-person main effect of caffeine intake on depression (β =−.01, 95% CI=[−.02, .001] , p=.042) such that caffeine intake was associated with fewer concurrent depressive symptoms. This association remained significant after accounting for the effects of past-night sleep in Step 2 (β =−.01, 95% CI=[−.03, −.01], p=.018). The interaction term was introduced in Step 3, and results of this analysis suggested that BSD diagnosis did not moderate the strength of the relationship between caffeine intake and same-day depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Cross-sectional and prospective associations between caffeine consumption and depressive symptoms

| Concurrent | Prospective | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |||||||||||||

| Level 1 | β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | β | ||

| Caffeine (within-person) | −.01 | −.02 –<.001 | .042 | −.01 | −.03 – −.01 | .018 | −.01 | −.03 –.003 | .135 | .01 | <.001 –.02 | .032 | .01 | <.001-.02 | .061 | .01 | −.01 –.02 | .242 |

| Caffeine*BSD | −.01 | −.04 – .02 | .429 | .01 | −.02 –.03 | .526 | ||||||||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine (between-person) | .04 | −.002 – .08 | .064 | .03 | −.01 – .08 | .152 | .03 | −.02–.08 | .249 | .04 | −.003 – .08 | .067 | .03 | −.01 – .08 | .129 | .03 | −.02 – .08 | .238 |

| BSD | .13 | .04 – .22 | .005 | .11 | .01 – .22 | .039 | .11 | .01–.22 | .039 | .12 | .03-.21 | .009 | .11 | .01-.22 | .039 | .11 | .01 –22 | .039 |

| Past-Night Sleep Duration | −.02 | −.03 – −.004 | .009 | −.02 | −.03– −.005 | .009 | −.01 | −.03 –<.001 | .060 | −.01 | −.03– .001 | .060 | ||||||

| Caffeine*BSD | .01 | −.10–.12 | .799 | .02 | −.09–.13 | .739 | ||||||||||||

| Variance Components | ||||||||||||||||||

| Individual | .07* | .07* | .07* | .07* | .07* | .08* | ||||||||||||

| Time Slope | .01a | .01a | .01a | .01a | .01a | .01a | ||||||||||||

| Observation | .07 | .07 | .07 | .07 | .07 | .07 | ||||||||||||

| AR(1) Rho Parameter | .14b | .13b | .13b | .13b | .13b | .13b | ||||||||||||

| Participants | 150 | 128 | 128 | 149 | 128 | 128 | ||||||||||||

| Observations | 2392 | 1823 | 1823 | 2280 | 1822 | 1822 | ||||||||||||

Notes: Significant findings are bolded. *p<.05, ap<.05 according to a multiparameter deviance test; bp<.05 according to a single-parameter deviance test. BSD = bipolar spectrum disorders; All analyses control for sex, age, and race; Caffeine and sleep duration were z-standardized.

In prospective analyses in Table 1, there also was a significant association between within-person caffeine consumption and next-day depressive symptoms, although the direction of this effect was opposite to that of the concurrent association. Caffeine intake was predictive of increased next-day depressive symptoms in this model (β=.01, 95% CI [<.001-.02], p<.01). However, this effect was not significant after controlling for sleep duration. There also was no evidence that BSD diagnostic group status moderated either the within- or between-person effects.

Table 2 shows results from models evaluating relationships between caffeine intake and hypomanic symptoms. An increase in within-person caffeine consumption was associated with higher same-day hypomanic symptoms in both unadjusted (β=.03, 95% CI=[.01-.04], p<.002) and adjusted (β=.04, 95% CI=[.02-.06], p<.001) models. The directionality of this finding was reversed when examining prospective relationships: in Step 1, caffeine intake was significantly associated with a decrease in next-day hypomanic symptoms at the within-person level (B=−.02, 95% CI=[−.04- −.004], p=.017). However, this association was not significant when considering the effects of sleep duration in Step 2. BSD diagnostic status did not moderate any associations.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional and prospective associations between caffeine consumption and hypomanic symptoms

| Concurrent | Prospective | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |||||||||||||

| Level 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine (within-person) | .03 | .01–.04 | <.001 | .04 | .02–.06 | <.001 | .03 | .01–.06 | .002 | −.02 | −.04–−.004 | .017 | −.01 | −.03 – .003 | .096 | −.02 | −.04 –.003 | .085 |

| Caffeine*BSD | .02 | −.02 –.05 | .388 | .01 | −.03 –.05 | .528 | ||||||||||||

| Level 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Caffeine (between-person) | −.07 | −.15 – .01 | .089 | −.06 | −.15–.02 | .121 | −.04 | −.13–.05 | .379 | −.07 | −.15–.01 | .110 | −.04 | −.12 – .04 | .311 | −.01 | −.10–.08 | .848 |

| BSD | .11 | −.07–.28 | .227 | .12 | −.06–.31 | .195 | .12 | −.07–.31 | .217 | .11 | −.07 – .28 | .219 | .14 | −.05 – .33 | .158 | .13 | −.06 – .32 | .18 |

| Past-Night Sleep Duration | −.02 | −.04–<.001 | .048 | −.02 | −.04 –<.001 | .053 | −.02 | −.04– −.01 | .016 | −.02 | −.04 – −.01 | .017 | ||||||

| Caffeine*BSD | −.11 | −.30–.08 | .265 | −.15 | −.35 – .04 | .125 | ||||||||||||

| Variance Components | ||||||||||||||||||

| Individual | .19* | .17* | .17 | .21 | .18 | .18 | ||||||||||||

| Time Slope | <.01a | <.01a | <.01a | <.01a | <.01a | <.01a | ||||||||||||

| Observation | .15 | .15 | .15 | .14 | .14 | .14 | ||||||||||||

| AR(1) Rho Parameter | .13b | .11b | .11b | .13b | .10b | .10b | ||||||||||||

| Participants | 2392 | 1823 | 1823 | 2280 | 1822 | 1822 | ||||||||||||

| Observations | 150 | 128 | 128 | 149 | 128 | 128 | ||||||||||||

Notes: Significant findings are bolded. *p<.05, ap<.05 according to a multiparameter deviance test; bp<.05 according to a single-parameter deviance test. BSD = bipolar spectrum disorders; All analyses control for sex, age, and race; Caffeine and sleep duration were z-standardized.

Next, a test of multilevel mediation was conducted with caffeine intake as the focal predictor, sleep duration as a mediator, and next-day depressive symptoms as the dependent variable (Figure 2). In the mediation model, caffeine intake was a significant predictor of next-day depressive symptoms (B= .06, SE= .03, p= .022), while sleep duration was not (B= −.03, SE= .02, p= .087). The path from caffeine intake to sleep duration was significant (B = −.09, SE = .03, p=.002) such that increased caffeine consumption was associated with shorter sleep duration that night. The indirect effect of caffeine intake predicting next-day depressive symptoms via sleep duration was significant (B = .003, p =.020). Multilevel moderated mediation analysis tested for group differences in the indirect effect on the path between sleep duration and depressive symptoms by BSD group; the index of moderated mediation was not significant (−.034, 95% CI −.118, .017).

Figure 2.

Mediation analysis with bootstrapping evaluating the effect of caffeine intake leading to prospective depressive symptoms via sleep duration.

Finally, a second test of multilevel mediation was conducted with caffeine intake as the focal predictor, sleep duration as a mediator, and next-day hypomanic symptoms as the dependent variable (Figure 3. In the mediation model, sleep duration was a significant predictor of next-day hypomanic symptoms (B= −.04, SE= .02, p= .021) while caffeine intake was not significant (B= −.04, SE= .02, p= .060). As above, the path from caffeine intake to sleep duration was significant (B = −.09, SE = .03, p=.002). The indirect effect of caffeine intake predicting next-day hypomanic symptoms via sleep duration was significant (B = .004, p <.001). Multilevel moderated mediation analysis tested for group differences in the indirect effect on the path between sleep duration and hypomanic symptoms by BSD group; the index of moderated mediation was not significant (.040, 95% CI −.018, .131).

Figure 3.

Mediation analysis with bootstrapping evaluating the effect of caffeine intake leading to prospective hypomanic symptoms via sleep duration.

4. Discussion

These findings add to the limited extant literature on caffeine use in bipolar spectrum disorders by evaluating the day-to-day associations between caffeine consumption, sleep duration, and mood symptoms and testing the mechanistic hypothesis that caffeine leads to mood symptoms through its effect on sleep duration. There are three main findings from this investigation: 1) caffeine intake was concurrently associated with fewer same-day depressive symptoms and more same-day hypomanic symptoms, 2) shorter sleep duration partially mediated the longitudinal association between caffeine intake and more next-day depressive symptoms, while shorter sleep duration fully mediated the relationship between caffeine intake and next-day hypomanic symptoms, and 3) the associations between caffeine intake and mood symptoms were similar among individuals with BSD relative to those without BSD. The hypothesis that caffeine may be particularly mood destabilizing for individuals with BSD, at least in the short term, is not supported by these results. However, sleep duration appears to be an important pathway through which caffeine impacts mood.

Across all models, we found no evidence of between-person associations between caffeine intake and mood symptoms. In other words, the results did not suggest that people who consume more or less caffeine overall experience higher or lower mood symptoms. However, we did observe small but significant within-person associations at the same-day level. Examining the concurrent unadjusted models (i.e., Step 1), an increase in caffeine relative to an individual’s mean was related to lower depressive symptoms and more hypomanic symptoms that same day. These cross-sectional effects remained robust when controlling for past-night’s sleep duration in Step 2. These findings are consistent with literature suggesting moderate caffeine usage (i.e., less than 6 cups per day) is associated with less depressive symptoms (Lara, 2010) and meta-analytic findings indicating that an 8 oz increase in coffee intake is linked to a 4% decreased risk of depression (Torabynasab et al., 2023). The positive association between caffeine and hypomanic symptoms was consistent with our hypotheses, likely reflecting overlap between the stimulant effects of caffeine (e.g., increased energy) and features of hypomania. Neither the between-person nor within-person interaction terms emerged as significant, suggesting BSD diagnostic status does not significantly impact the strength of any association.

A different pattern of results emerged when examining longitudinal (next-day) associations. Interestingly, in unadjusted models that did not account for sleep duration, caffeine was linked to higher depressive symptoms and lower hypomanic symptoms the next day. However, neither finding remained significant once sleep duration was introduced as a covariate in Step 2. Taken together, it could be possible that caffeine does not impact mood above and beyond the effects of sleep duration.

The interrelationship between caffeine, sleep, and mood was explored more thoroughly through mediation analysis (see Figures 2 and 3). As shown in Figure 2, both the direct effect of caffeine on depressive symptoms and the indirect effect via sleep duration were significant, indicating that shorter sleep duration partially mediated the relationship between caffeine intake and depressive symptoms. When considered alongside the cross-sectional results, it appears that caffeine may offer short-term mood benefits (potentially through increased energy or motivation), but there was a delayed consequence reflected in more next-day depressive symptoms, which only were partially accounted for by reduced sleep duration. This finding was relatively unexpected considering research has found caffeine use is protective against depression and tends to be linked to positive health outcomes in the general population (Poole et al., 2017). The positive association between caffeine consumption and next-day depressive symptoms may be due in part to the nature of the sample, which is enriched for BSD and oversampled for reward hypersensitivity. Consuming caffeine may be a form of self-medication for low mood or anhedonia as it impacts neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine (Solinas et al., 2002). Caffeine also may exacerbate affective dysregulation through next-day fatigue or irritability, especially in sensitive populations such as individuals with mental health difficulties. Further, reward hypersensitivity has been associated with greater caffeine consumption (Penolazzi et al., 2012). It is possible caffeine is used as a tool during goal-striving periods, although this has not been directly evaluated and more research is needed.

As shown in Figure 3, the direct effect of caffeine on next-day hypomanic symptoms was not significant while the indirect effect via sleep duration was significant, suggesting the influence of caffeine on hypomanic symptoms is fully mediated by its impact on sleep duration. Caffeine intake was not directly associated with next-day hypomanic symptoms, rather caffeine decreased sleep duration, and decreased sleep duration increased hypomanic symptoms. This finding speaks to the importance of sufficient sleep length in the management of mood symptoms, particularly in the context of BSD (Gruber et al., 2011).

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study has notable strengths: it is one of the first to prospectively examine the relationship between caffeine usage, sleep duration, and mood symptoms in individuals with BSD, and the large sample size combined with repeated sampling techniques facilitated within-person and between-person analyses. We also used an objective indicator of sleep, actigraphy, and advanced statistical approaches (multilevel moderated mediation) to test a rigorous mechanistic model in which caffeine impacts mood through its effects on sleep. There are several limitations: mood symptoms and caffeine intake were measured subjectively via self-report, although prior work has found that self-report and salivary caffeine concentrations are significantly correlated, increasing our confidence in the findings (Addicott et al., 2009). Relatedly, tea, coffee, soda, and energy drinks have varying caffeine content, which was not explicitly measured in this study. However, given our emphasis on the within-person effects in which an individual is being compared to their own average, the between-person differences in reporting accuracy are less of a concern. Caffeine intake only was measured once per day, so we cannot draw any conclusions about the timing of caffeine consumption (i.e., whether evening caffeine consumption is more prevalent among certain groups, and whether the timing, and not quantity, contributes to sleep or mood disturbance). Although many important confounders were included in our models (e.g., sex, age, race, sleep duration), smoking, alcohol, and drug use were not measured daily, and thus, could not be included as time-varying covariates.

Overall, we found that caffeine consumption is related to depressive and hypomanic symptoms, and sleep duration appears to be an important pathway through which these associations operate. Associations between caffeine and mood were not stronger among individuals with BSD. This investigation represents an important first step in clarifying the temporal dynamics of caffeine, sleep, and mood among individuals with BSD.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the young adults who participated in this study.

Declaration of interest:

This study was supported in part by the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship to Rachel Walsh and by National Institute of Mental Health R01 grants MH077908, MH102310, and MH126911 to Lauren B. Alloy. Namni Goel was supported in part by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) grants NNX14AN49G and 80NSSC20K0243 and National Institutes of Health grant R01DK117488.

References

- Addicott MA, Yang LL, Peiffer AM, & Laurienti PJ (2009). Methodological considerations for the quantification of self-reported caffeine use. Psychopharmacology, 203, 571–578. 10.1007/s00213-008-1403-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, Cogswell A, Grandin LD, Hughes ME, Iacoviello BM, Whitehouse WG, Urosevic S, Nusslock R, & Hogan ME (2008). Behavioral Approach System and Behavioral Inhibition System sensitivities and bipolar spectrum disorders: Prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 310–322. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Bender RE, Whitehouse WG, Wagner CA, Liu RT, Grant DA, Jager-Hyman S, Molz A, Choi JY, Harmon-Jones E, & Abramson LY (2012). High behavioral approach system (BAS) sensitivity, reward responsiveness, and goal-striving predict first onset of bipolar spectrum disorders: A prospective behavioral high-risk design. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 339–351. 10.1037/a0025877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Olino T, Freed RD, & Nusslock R (2016). Role of Reward Sensitivity and Processing in Major Depressive and Bipolar Spectrum Disorders. Behavior Therapy, 47, 600–621. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Urošević S, Abramson LY, Jager-Hyman S, Nusslock R, Whitehouse WG, & Hogan M (2012). Progression along the bipolar spectrum: A longitudinal study of predictors of conversion from bipolar spectrum conditions to bipolar I and II disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 16–27. 10.1037/a0023973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, & Davis JM (1997). The altman self-rating Mania scale. Biological Psychiatry, 42, 948–955. 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Benko CR, Farias AC, Farias LG, Pereira EF, Louzada FM, & Cordeiro ML (2011). Potential link between caffeine consumption and pediatric depression: A case-control study. BMC Pediatrics, 11. 10.1186/1471-2431-11-73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & White TL (1994). Behavioral Inhibition, Behavioral Activation, and Affective Responses to Impending Reward and Punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 319–333. 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I, & Landolt HP (2017). Coffee, caffeine, and sleep: A systematic review of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 31, 70–78. 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, & Gillin JC (1992). Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep, 15, 461–469. 10.1093/sleep/15.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo C, Benedetti F, Barbini B, Campori E, & Smeraldi E (1999). Rate of switch from depression into mania after therapeutic sleep deprivation in bipolar depression. Psychiatry Research, 86, 267–270. 10.1016/S0165-1781(99)00036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, & Spitzer RL (1978). A Diagnostic Interview: The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 837–844. 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio S, Strawbridge R, & Young AH (2021). The impact of caffeine consumption on clinical symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder: A systematic review. In Bipolar Disorders (Vol. 23, Issue 3, pp. 241–251). 10.1111/bdi.12990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold AK, & Sylvia LG (2016). The role of sleep in bipolar disorder. Nature and science of sleep, 8, 207–214. 10.2147/NSS.S85754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Miklowitz DJ, Harvey AG, Frank E, Kupfer D, Thase ME, Sachs GS, & Ketter TA (2011). Sleep matters: sleep functioning and course of illness in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 134(1-3), 416–420. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Schmidt DA, Scarnà A, Semler CN, & Goodwin GM (2005). Sleep-related functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, patients with insomnia, and subjects without sleep problems. American Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Talbot LS, & Gershon A (2009). Sleep Disturbance in Bipolar Disorder Across the Lifespan. Clinical psychology : a publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association, 16(2), 256–277. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01164.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, & Akiskal HS (2003). The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: Re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. Journal of Affective Disorders, 73, 123–131. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00332-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KA, Talbot LS, Gruber J, & Harvey AG (2012). Evaluating sleep in bipolar disorder: Comparison between actigraphy, polysomnography, and sleep diary. Bipolar Disorders, 14, 870–879. 10.1111/bdi.12021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing LV, Vradi E, & Andersen PK (2015). Life expectancy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 17, 543–548. 10.1111/bdi.12296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing LV, Hansen MG, Andersen PK, & Angst J (2004). The predictive effect of episodes on the risk of recurrence in depressive and bipolar disorders - A life-long perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109, 339–344. 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara DR (2010). Caffeine, mental health, and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD, 20 Suppl 1, S239–S248. 10.3233/JAD-2010-1378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leffa DT, Ferreira SG, Machado NJ, Souza CM, da Rosa F, de Carvalho C, Kincheski GC, Takahashi RN, Porciúncula LO, Souza DO, Cunha RA, & Pandolfo P (2019). Caffeine and cannabinoid receptors modulate impulsive behavior in an animal model of attentional deficit and hyperactivity disorder. European Journal of Neuroscience, 49, 1673–1683. 10.1111/ejn.14348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cruz L, Salamone JD, & Correa M (2018). Caffeine and selective adenosine receptor antagonists as new therapeutic tools for the motivational symptoms of depression. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A, Espie CA, & Scott J (2004). The sleep of remitted bipolar outpatients: A controlled naturalistic study using actigraphy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 80, 145–153. 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TH, Chung KF, Ho FYY, Yeung WF, Yung KP, & Lam TH (2015). Sleep-wake disturbance in interepisode bipolar disorder and high-risk individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 20, 46–58. 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh SV, Hawke LD, Velyvis V, Zaretsky A, Beaulieu S, Patelis-Siotis I, Macqueen G, Young LT, Yatham LN, & Cervantes P (2015). Combined treatment: Impact of optimal psychotherapy and medication in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 17, 86–96. 10.1111/bdi.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penolazzi B, Natale V, Leone L, & Russo PM (2012). Individual differences affecting caffeine intake. Analysis of consumption behaviours for different times of day and caffeine sources. Appetite, 58, 971–977. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, Marangell LB, Zhang H, Wisniewski SR, Ketter TA, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Gyulai L, Reilly-Harrington NA, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS, & Thase ME (2006). Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: Primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 217–224. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, & Parkes J (2017). Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 359, j5024. 10.1136/bmj.j5024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Jones I, & Simpson S (2010). Psychoeducation for bipolar disorder. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16, 147–154. 10.1192/apt.bp.108.006403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Ferré S, You ZB, Karcz-Kubicha M, Popoli P, & Goldberg SR (2002). Caffeine induces dopamine and glutamate release in the shell of the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 22(15), 6321–6324. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06321.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titone MK, Goel N, Ng TH, MacMullen LE, & Alloy LB (2022). Impulsivity and sleep and circadian rhythm disturbance predict next-day mood symptoms in a sample at high risk for or with recent-onset bipolar spectrum disorder: An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 298, 17–25. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titone MK, McArthur BA, Ng TH, Burke TA, McLaughlin LE, MacMullen LE, Goel N, & Alloy LB (2020). Sex and race influence objective and self-report sleep and circadian measures in emerging adults independently of risk for bipolar spectrum disorder. Scientific Reports, 10, 13731. 10.1038/s41598-020-70750-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torabynasab K, Shahinfar H, Payandeh N, & Jazayeri S (2023). Association between dietary caffeine, coffee, and tea consumption and depressive symptoms in adults: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Frontiers in nutrition, 10, 1051444. 10.3389/fnut.2023.1051444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Ávila C, Moltó J, & Caseras X (2001). The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 837–862. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00183-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafillou S, Saeb S, Lattie EG, Mohr DC, & Kording KP (2019). Relationship between sleep quality and mood: Ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Mental Health, 6. 10.2196/12613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HR, Woo YS, & Bahk WM (2015). Caffeine-induced psychiatric manifestations: A review. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 30, 179–182. 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, Sharma V, Goldstein BI, Rej S, Beaulieu S, Alda M, MacQueen G, Milev RV, Ravindran A, O’Donovan C, McIntosh D, Lam RW, Vazquez G, Kapczinski F, … Berk M (2018). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 20, 97–170. 10.1111/bdi.12609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]