Abstract

Fructosyltransferase (FTF) enzymes produce fructose polymers (fructans) from sucrose. Here, we report the isolation and characterization of an FTF-encoding gene from Lactobacillus reuteri strain 121. A C-terminally truncated version of the ftf gene was successfully expressed in Escherichia coli. When incubated with sucrose, the purified recombinant FTF enzyme produced large amounts of fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) with β-(2→1)-linked fructosyl units, plus a high-molecular-weight fructan polymer (>107) with β-(2→1) linkages (an inulin). FOS, but not inulin, was found in supernatants of L. reuteri strain 121 cultures grown on medium containing sucrose. Bacterial inulin production has been reported for only Streptococcus mutans strains. FOS production has been reported for a few bacterial strains. This paper reports the first-time isolation and molecular characterization of (i) a Lactobacillus ftf gene, (ii) an inulosucrase associated with a generally regarded as safe bacterium, (iii) an FTF enzyme synthesizing both a high molecular weight inulin and FOS, and (iv) an FTF protein containing a cell wall-anchoring LPXTG motif. The biological relevance and potential health benefits of an inulosucrase associated with an L. reuteri strain remain to be established.

Fructose polymers (fructans) are produced by a wide range of bacteria. Limited information about fructan synthesis by lactic acid bacteria is available. Most of the attention has been focused on oral streptococci because of their role in dental caries formation (4). Streptococci produce both fructans of the levan type (12, 15) with β-(2→6)-linked fructosyl units and fructans of the inulin type with β-(2→1)-linked fructosyl units. Streptococcus mutans JC-2 for instance produces a fructan consisting mainly of β-(2→1)-linked fructosyl units with 5% β-(2→6) branches (12, 32). The fructan produced by the S. mutans strain Ingbritt contains mainly β-(2→1)-linked fructosyl units (1). Previously, it was reported that Lactobacillus reuteri strain 121 cultivated on medium containing sucrose produces both a glucan and a fructan polymer (43). The fructan polymer is a linear levan, consisting of only β-(2→6)-linked fructosyl residues, with an estimated size of 150,000 (43).

The enzymes responsible for the synthesis of fructans are generally referred to as fructosyltransferases (FTFs) or, more specifically, levansucrase (in the case of levan synthesis) and inulosucrase (in the case of inulin synthesis). Inulosucrase (sucrose: 2,1-β-d-fructan 1-β-d fructosyltransferase, EC 2.4.1.9) catalyzes the following reaction: sucrose + (2,1-β-d-fructosyl)n → d-glucose + (2,1-β-d-fructosyl)n + 1

Bacterial inulosucrases have been described for only S. mutans (9, 32, 35). Levansucrase enzymes have been found in, for instance, Zymomonas mobilis (47), Erwinia amylovora (14), Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus (17), Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (40), and Bacillus subtilis (39, 40). Among lactic acid bacteria, levansucrase enzymes have been reported for Leuconostoc mesenteroides (31), Streptococcus salivarius (12, 15), and L. reuteri (44). Recently, purification of the levansucrase enzyme responsible for levan formation in L. reuteri strain 121 was reported (44).

The Lactobacillus polysaccharides are of special interest because they may also contribute to human health as prebiotics (7) or because of their antitumoral (11), antiulcer (27), immunomodulating (37), or cholesterol lowering (30) activity. Moreover, some strains (e.g., L. reuteri) have been designated as probiotics (7, 13, 16).

Here, we report the molecular characterization of a novel ftf gene from L. reuteri strain 121, including an analysis of the products synthesized from sucrose by the enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli. The enzyme is an inulosucrase, synthesizing both inulin fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) and a high-molecular-weight inulin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

L. reuteri strain 121 (TNO Nutrition and Food Research culture collection, Zeist, The Netherlands) was grown anaerobically at 37°C in MRS medium (10) or in modified MRS medium containing 50 g of sucrose liter−1 (MRS-S) instead of 20 g of glucose liter−1. Because phosphate and citrate interfered with high-pressure liquid chromatography, FOS production by L. reuteri was studied with cultures grown in modified MRSs medium in which phosphate was omitted and ammonium citrate was replaced by ammonium nitrate.

E. coli strains JM109 (Phabagen, Utrecht, The Netherlands) and Top10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) were used as hosts for cloning. E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (3) and, when appro-priate, supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin ml−1 for maintaining plasmids or with 0.02% (wt/vol) arabinose for induction of ftf gene expression. Agar plates were made by adding 1.5% (wt/vol) agar to the medium.

General molecular techniques.

L. reuteri chromosomal DNA was isolated according to the method of Verhasselt et al. (45) as modified by Nagy et al. (25). E. coli plasmid DNA was isolated with a Wizard Plus SV plasmid extraction kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). General procedures for cloning, DNA manipulations, and agarose gel electrophoresis were as described previously (34). Restriction endonuclease digestions and ligations with T4 DNA ligase were performed as recommended by the suppliers (GIBCO BRL Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands; New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, Mass.; Roche Biochemicals, Basel, Switzerland). DNA was amplified with PCR techniques (DNA Thermal Cycler 480; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) by using Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Biochemicals) for the standard PCRs and high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Roche Biochemicals) for inverse PCRs. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc. (Piscataway, N.Y.). DNA fragments were isolated from agarose gels by using a Qiagen (Chatsworth, Calif.) extraction kit, following the instructions of the supplier. E. coli transformations were performed by electroporation in 0.2-mm cuvettes with the Bio-Rad gene pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) at 2.5 kV, 25 μF, and 200 Ω following the instructions of the manufacturer.

For Southern hybridization studies, DNA was restricted, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred to a Hybond nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Probes were labeled with the DIG DNA random-primed labeling and detection kit (Roche Biochemicals) following the manufacturer's instructions. Stringent hybridizations were done at 62°C; nonstringent hybridizations were done at 45°C (followed by washing with 0.5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]-0.1 sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]).

Identification and nucleotide sequence analysis of the FTF gene.

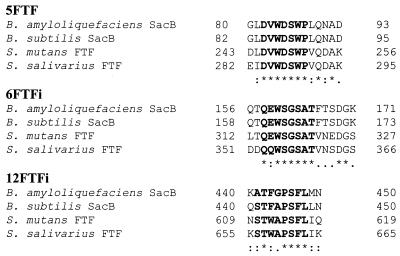

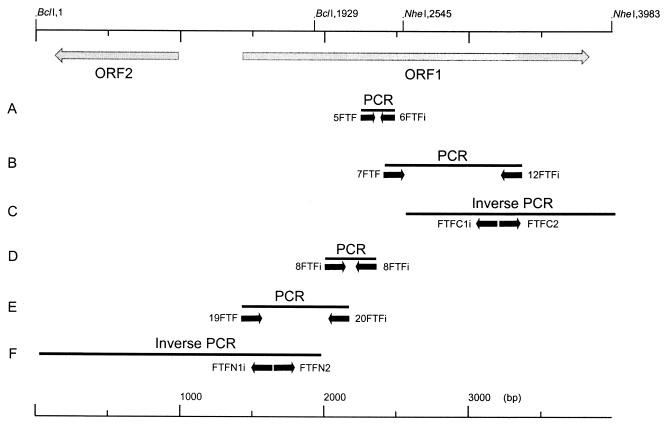

By using the degenerated primers 5FTF and 6FTFi, based on the conserved amino acid sequences of FTFs of gram-positive origin (Fig. 1), the chromosomal DNA of L. reuteri strain 121, and DNA polymerase, a PCR product of 234 bp was obtained (Fig. 2A). This fragment was cloned in E. coli strain JM109 by using the pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) vector and sequenced. Primer 7FTF (Table 1) was designed based on this fragment, and primer 12FTFi was based on the conserved amino acid sequences of the FTFs of gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 1). PCR with primers 7FTF and 12FTFi gave a product of 948 bp (Fig. 2B), which was cloned in pCR2.1 and sequenced. The 948-bp product was used to design primers FTFC1i (Table 1) and FTFC2 (Table 1) for inverse PCR purposes. L. reuteri DNA was cut with NheI, ligated, and used in a PCR with primers FTFC1i and FTFC2, generating a 1,438-bp fragment (Fig. 2C), which was cloned and sequenced.

FIG. 1.

Parts of an alignment of amino acid sequences from four bacterial FTFs. The amino acid sequences are from B. amyloliquefaciens SacB (X52988), B. subtilis SacB (X02730), S. mutans FTF (M18954), and S. salivarius FTF (L08445). Sequences in bold indicate the consensus sequences used to construct the degenerated primers 5FTF (5′-GAYGTNTGGGAYWSNTGGGCC-3′), 6FTFi (5′-GTNGCNSWNCCNSWCCAYTSYTG-3′), and 12FTFi (5′-ARRAANSWNGGNGCVMANGTNSW-3′). Sequences are according to International Union of Biochemistry group codes: N, any base; M, A or C; R, A or G; W, A or T; S, C or G; Y, C or T; K, G or T; B, not A; D, not C; H, not G; V, not T. An asterisk indicates a position with a fully conserved amino acid residue, a colon indicates a position with a fully conserved strong group, and a period indicates a position with a fully conserved weaker group The number of base pairs is indicated to the right.

FIG. 2.

Strategy used for the isolation of the ftf gene from L. reuteri strain 121 chromosomal DNA.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primera | Sequence (5′ to 3′)b | Use |

|---|---|---|

| 7FTF | GAATGTAGGTCCAATTTTTGGC | PCR |

| FTFC1i | GTGATACATTTCCATTATTATCAG | Inverse PCR |

| FTFC2 | CTATTACTACCAAACTTATGATCATG | Inverse PCR |

| 8FTFi | CCTGTCCGAACATCTTGAACTG | Inverse PCR |

| 20FTFi | CCGACCATCTTGTTTGATTAAC | PCR |

| 19FTF | TAYAAYGGNGTNGCNGARGTNAA | PCR |

| FTFN1i | GAGAGTGTAACGACTGCCCAATTTTTACCGC | Inverse PCR |

| FTFN2 | CTGCTAATGCAAATAGTGCTTCTTCTGCCGC | Inverse PCR |

| FTF1 | CCATGGCCATGGTAGAACGCAAGGAACATAAAAAAATG | pBAD |

| FTF2i | AGATCTAGATCTGTTAAATCGACGTTTGTTAATTTCTG | pBAD |

| FTF2iB | AGATCTAGATCTTTAGTTAAATCGACGTTTGTTAATTTCTG | pBAD |

| FTFrp2 | AGATCTAGATCTTTTTAATCCATAACCAATTAAG | pBAD |

| FTFrp2B | AGATCTAGATCTTTATTTTAATCCATAATTAAG | pBAD |

i and rp, reverse.

Degenerated bases are indicated according to IUB codes shown in the legend to Fig. 1. In the primer sequences, NcoI and BglII restriction sites are underlined and stop codons introduced are shown in bold.

The remaining 5′ fragment of the putative ftf gene was isolated by standard and inverse PCR techniques. The 234-bp fragment (Fig. 2A) was used to design primer 8FTFi (Table 1) for inverse PCR purposes. L. reuteri DNA was cut with several restriction enzymes and ligated. PCR with primers 7FTF and 8FTFi, with the ligation product as template, yielded in all cases a PCR product of approximately 400 bp which was cloned into pCR2.1 and sequenced (379 bp [Fig. 2D]). This revealed that primer 8FTFi had annealed aspecifically (from positions 1896 to 1917) as well as specifically (from positions 2275 to 2254). This fragment was used to design primer 20FTFi (Table 1). Based on 7 amino acids (YNGVAEV) from the N-terminal amino acid sequence (QVESNNYNGVAEVNTERQANGQI) of a levansucrase enzyme purified from L. reuteri strain 121 (44), a degenerated primer 19FTF (Table 1) was designed. PCR with primers 19FTF and 20FTFi gave a 754-bp PCR product (Fig. 2E) which was cloned into pCR2.1 and sequenced. Two inverse PCR primers, FTFN1i (Table 1) and FTFN2 (Table 1), were designed based on this fragment. Strain 121 DNA was cut with BclI, ligated, and used in a PCR with primers FTFN1i and FTFN2, yielding a 1,752-bp PCR product (Fig. 2F). Both DNA strands of the fragments comprising the entire contig were sequenced. In this way, the sequence of a 3,983-bp region of L. reuteri strain 121 genomic DNA that contained the ftf gene was obtained.

Construction of plasmids for expression of the ftf gene in E. coli.

Four primer sets were designed for expression of the ftf gene in E. coli. (i) A full-length ftf sequence (nucleotides 1432 to 3825) with a C-terminal myc epitope and polyhistidine (poly-His) tag (InuHis) was generated with primers FTF1 (Table 1) and FTF2i (Table 1). (ii) A full-length ftf sequence (Inu) was generated with primers FTF1 and FTF2iB (Table 1). (iii) A truncated ftf sequence (nucleotides 1432 to 3525) encoding an FTF C terminally truncated from amino acid 699 onwards with a C-terminal myc epitope and poly-His tag (InuΔ699His) was generated with primers FTF1 and FTFrp2 (Table 1). (iv) A truncated ftf sequence encoding an FTF C terminally truncated from amino acid 699 onwards (InuΔ699) was generated with primers FTF1 and FTFrp2B (Table 1). Primer FTF1 introduces a mutation in the ftf sequence, changing the second (leucine) codon into a valine codon, necessary for introduction of the NcoI restriction site. PCR with L. reuteri genomic DNA (approximately 1 μg), Pwo DNA polymerase, and the primer sets yielded the ftf gene derivatives flanked by the NcoI and BglII restriction sites. The PCR products were cut with NcoI and BglII and ligated into the expression vector pBAD/myc-His C (Invitrogen) downstream of the inducible arabinose promoter and in frame upstream of a myc epitope and a poly-His tag. The resulting constructs were transformed to E. coli Top10 and used to study FTF expression. Correct construction of the plasmids containing the four ftf gene derivatives was confirmed by sequence analysis of both DNA strands of the inserts.

FTF purification.

Cells of E. coli Top10 harboring the ftf gene (InuHis and InuΔ699His constructs) were grown overnight in 400 ml of LB medium with 0.02% arabinose to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.9. The pellets were washed with 50 ml of binding buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4 or NaH2PO4; pH 8.0) containing 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, centrifuged, and resuspended in binding buffer containing 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Cells were broken by ultrasonication (7 × 10 s at 6 μ with 20-s intervals), followed by centrifugation for 30 min at 10,000 × g. The resulting cell extracts (CEs) were used in enzyme assays, or in the case of InuΔ699His, for nickel affinity purification. A bed volume of 600 μl of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Qiagen) was used to bind protein from 11.6 ml of CE (3.0 mg of protein ml−1). The resin was washed with 6 ml of demineralized water and 3 ml of binding buffer prior to applying CE. CE was added to the washed Ni-NTA agarose, and the tubes were gently shaken at 4°C for 1 h. After washing with 3 ml of binding buffer, the bound protein was eluted from the affinity resin with 3 ml of binding buffer containing 200 mM imidazole and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The eluted fractions were dialyzed against a phosphate solution (5 mM, pH 8) and stored at 4°C. The dialyzed Ni-NTA elution fractions (3 ml; 2.0 mg of protein ml−1) were adjusted to a volume of 5 ml in a Tris buffer (20 mM, pH 8.0). An anion-exchange column (Resource-Q; 1-ml column volume; flow rate, 1 ml min−1; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was equilibrated with a Tris buffer (20 mM, pH 8.0; buffer A) and the sample (5 ml) was loaded on the column. After eluting the column with Tris buffer (20 mM, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl; buffer B), fractions were collected from 20% buffer B to 80% buffer B and screened for FTF activity (glucose release from sucrose; see below). Positive fractions were checked with SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (22) by using a mini-PROTEAN II slab gel system (Bio-Rad), and fractions showing only the FTF protein band were pooled (11.7 ml; 0.038 mg of protein ml−1), dialyzed overnight against a sodium acetate (NaAc) buffer (20 mM, pH 5.4), and stored at 4°C for further analysis.

Biochemical characterization of the recombinant FTF enzyme. (i) N-terminal amino acid sequencing.

Protein (approximately 10 μg) was run on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore Inc., Bedford, Mass.) by Western blotting (34). After staining the PVDF membrane with Coomassie brilliant blue (34), the corresponding bands were cut from the PVDF membrane and subjected to amino acid sequence determination (Nucleic Acids Protein Sequences Unit, Biotechnology Laboratory, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) by using standard pulsed-liquid Edman chemistry on a Procise protein sequencing system (model 494; Applied Biosystems).

(ii) Sucrase enzyme activity assays.

Sucrose conversion by FTF yields glucose (and fructose, which is partly built into the fructan polymer) in a 1/1 molar ratio to the amount of sucrose used. The amount of glucose released allows determination of the overall enzyme activity (total amount of sucrose converted). Glucose was measured as described previously (44). FTF enzyme activity was measured in NaAc buffer (25 mM, pH 5.4) with 250 mM sucrose and 1 mM CaCl2. Preliminary experiments showed that the recombinant FTF enzyme had the highest glucose-releasing activity from sucrose at 50°C. Therefore, specific activity measurements were done at 50°C. One unit of enzyme is defined as the release of 1 μmol of glucose per min.

(iii) SDS-PAGE activity staining.

In order to measure enzyme activity in SDS-PAGE gels, periodic acid-Schiff reagent staining (PAS) (21) was done. Protein (approximately 1 μg) was run on SDS-PAGE gels, followed by washing in a preincubation buffer (25 mM NaAc [pH 5.4] 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100) and overnight incubation in preincubation buffer with 50 mM sucrose or 50 mM raffinose. The gels were washed 30 min in a 12.5% trifluoroacetic acid solution in demineralized water and incubated for 50 min in a 1% periodic acid-3% hydrogen acetate buffer. The periodic acid was washed away carefully with demineralized water, after which the gels were stained with Schiff reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.), yielding purple spots where fructan polymer was produced.

Characterization of fructan and FOS.

The FTF enzyme had an optimum temperature of 50°C for the release of glucose from sucrose. L. reuteri strain 121, however, showed optimal growth at 37°C. The reaction products of FTF were determined following incubations at the physiological temperature of strain 121 (37°C). Fructan and FOS synthesis was studied in CEs of E. coli cells with InuHis (96 U liter−1) and with the purified InuΔ699His (83 U liter−1). FTF protein was incubated for 17 h at 37°C in 250 ml of NaAc buffer (25 mM, pH 5.4) containing 90 g of sucrose liter−1 and 1 mM CaCl2. Polymeric fructan material was precipitated with 2 volumes of 96% ethanol followed by a 10-min centrifugation at 10,000 × g. The pellet was resuspended in demineralized water for 16 h at 4°C, after which it was dialyzed against demineralized water. Subsequently, polymer was precipitated as described above and freeze-dried for further analysis. Inulin and FOS synthesis was also studied in cultures of L. reuteri strain 121 grown overnight in modified MRS-S medium. For anion-exchange chromatography (Dionex, Sunnyvale, Calif.), samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g and diluted 200 times in a 100% dimethyl sulfoxide solution. An inulin digest (with a degree of polymerization of 1 to 20), 1-kestose (8 mg liter−1), or nystose (6 mg liter−1; Fluka Chemie, Milwaukee, Wis.) was used as a standard. Separation was achieved with a CarboPac PA1 anion-exchange column (250 by 4 mm; Dionex) coupled to a CarboPac PA1 guard column (Dionex). The following gradient was used: eluent B at 5% (0 min), 35% (10 min), 45% (20 min), 65% (50 min), 100% (54 to 60 min), and 5% (61 to 65 min). Eluent A was sodium hydroxide (0.1 M) and eluent B was NaAc (0.6 M) in sodium hydroxide (0.1 M). Detection was done with an ED40 electrochemical detector (Dionex) with an Au working electrode and an Ag-AgCl reference electrode with a sensitivity of 300 nC. The pulse program used was as follows: +0.1 V (0 to 0.4 s), +0.7 V (0.41 to 0.60 s), and −0.1 V (0.61 to 1.00 s). Data were integrated by using the Turbochrom (Applied Biosystems) data integration system. For cation-exchange chromatography, samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g and diluted five times in demineralized water. A cation-exchange column in the calcium form (at 85°C; particle size, 15 to 20 μm; column size, 250 by 10 mm; 0.4 ml min−1; BCX4, Benson Polymeric, Reno, Nev.) with a mobile phase of calcium-EDTA in demineralized water (100 ppm) was used. Detection was done by using a model 830 refractive index (RI) detector (Jasco International Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 40°C. The amounts of FOS, glucose, fructose, and sucrose were estimated by comparing the RI signals with those of glucose reference solutions. Methylation analysis of fructan was performed by permethylation with methyl iodide and solid sodium hydroxide in methyl sulfoxide. After hydrolysis with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (2 h, 120°C), the partially methylated monosaccharides were reduced with NaBD4. After neutralization, removal of boric acid by coevaporation with methanol, and acetylation with acetic acid anhydride (3 h, 120°C), the mixtures of partially methylated alditol acetates obtained were analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography on a CP-Sil 43 CB column (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and by gas-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry on DB-1 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) (19, 20). The molecular weight of the polymer was determined by high-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC) coupled on-line with a multiangle laser light scattering (MALLS) and differential RI detection (Schambeck SDF, Bad Honnef, Germany). The HPSEC system consisted of an isocratic pump, an injection valve, a guard column, and a set of two size exclusion chromatography columns in a series (a Shodex SB806MHQ column [Showa Denko, K.K., Kawasaki, Japan] and a TSK gel 6000PW column [Thomson, Clearbrook, Vancouver, Canada]). A DAWN-DSP-F (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, Calif.) laser photometer HeNe (λ = 623.8 nm) equipped with a K5 flow cell and thermostatted by a Peltier heating system, was used as a MALLS detector. Samples were filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore Inc.), and the injection volume was 220 μl. Na2SO4 (0.1 M) was used as the eluent at a flow rate of 0.8 ml min−1. Pullulan and dextran samples with Mw ranging from 40 to 2,000 were used as standards. Determinations were performed in duplicate.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank nucleotide accession number for the L. reuteri strain 121 gene encoding the inulosucrase enzyme and its flanking regions is AF459437.

RESULTS

Isolation and nucleotide sequence analysis of the L. reuteri strain 121 ftf gene.

PCR with degenerated primers, based on conserved amino acid sequences deduced from the alignment of a number of FTFs of gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 1), with the chromosomal DNA of L. reuteri strain 121 as template, yielded a single amplicon of 234 bp (Fig. 2A). Sequence analysis confirmed its ftf identity. With (inverse) PCR techniques, we obtained a large part of the ftf open reading frame (ORF), including its 3′ end (Fig. 2B and C). The 5′ of the ftf ORF was isolated in a PCR step with a degenerated primer based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified strain 121 levansucrase protein (44) (Fig. 2E). In total, a DNA fragment of 3,983 bp was sequenced. This fragment contained an ORF (ORF1) of 2,370 bp (starting at 1,432 bp), encoding a putative FTF, and an ORF of 852 bp (ORF2), located upstream of, and divergently transcribed from, ORF1. To our surprise, we could not locate the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the strain 121 levansucrase protein in the ORF1-deduced amino acid sequence. The degenerated primer used had misannealed, nevertheless yielding an amplicon. ORF1 did not encode the strain 121 levansucrase protein. Southern hybridization under nonstringent conditions with the 234 bp (Fig. 2A) and the 1,438-bp (Fig. 2C) PCR fragment and L. reuteri chromosomal DNA revealed only one hybridizing fragment.

No clear promoter and Shine-Dalgarno sequences that meet the consensus sequences could be identified in the DNA sequence upstream of ORF1. Two putative start codons were present in ORF1: (i) an ATG codon located at position 1432 (ii) and an ATG codon located at position 1459. The ATG codon at position 1459 had an imperfect Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AAGGAA) 13 bp upstream. The consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence is AGGAGG, which was found, for instance, for the acyl coenzyme A hydrolase from L. reuteri (AY082385). According to the consensus promoter sequences described for lactobacilli (29), the consensus sequence for −35 is TTGCTG and the consensus sequence for −10 is AATAAT, although the −10 sequence can vary among species. An imperfect promoter sequence could be identified (173 bp from the ATG codon at position 1432) with putative −35 and −10 sequences (TTGATG and TTACAA, with a spacing of 19 nucleotides). Starting at position 1432, the putative protein (798 amino acids) had a deduced molecular weight of 86,778 and a pI of 4.62. Starting at position 1459, the putative protein (789 amino acids) had a deduced molecular weight of 85,598 and a pI of 4.51.

Amino acid sequence alignments and specific features of the strain 121 FTF.

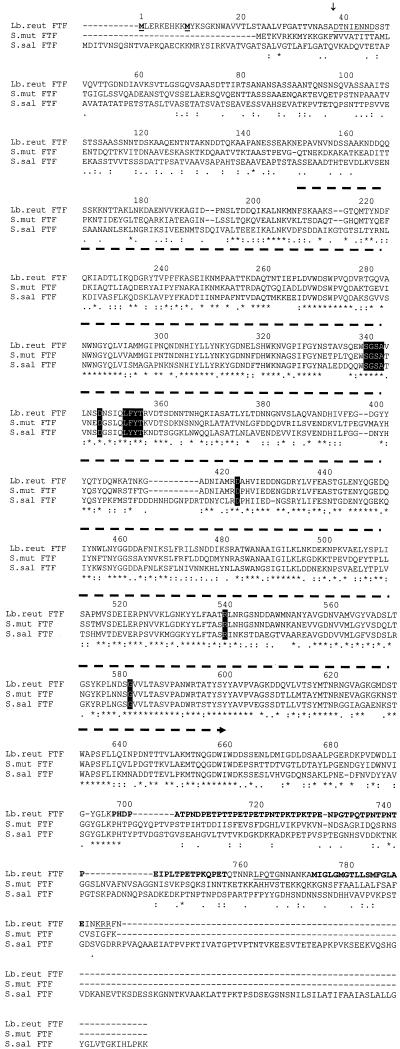

Blast searches with the deduced ORF1 amino acid sequence revealed the highest degrees of similarity with S. mutans FTF (P11701; 58% identity and 73% similarity in 686 amino acids) and S. salivarius FTF (Q55242; 49% identity and 67% similarity in 756 amino acids). In the deduced ORF1 sequence, a core region of 436 amino acids could be identified as belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 68 of the levansucrases and invertases (Fig. 3) (43% identity and 56% similarity in amino acid residues 210 to 661) (Pfam02435) (http://pfam.wustl.edu/). Family 68 was identified based on alignments between several FTFs and invertases. As of yet, no common structure could be assigned to the family 68 enzymes. An alignment of the deduced ORF1 amino acid sequence with streptococcal FTFs is shown in Fig. 3. This alignment revealed a very limited degree of similarity in the N-terminal amino acid sequences of the FTFs. Very limited information is available on the role of specific amino acids or regions in the catalytic mechanism of bacterial FTFs (Fig. 3). Based on literature, conserved amino acids found to be involved in catalysis were all present in the strain 121 FTF sequence (Fig. 3). A putative signal peptidase cleavage site (26) was present between amino acids ASA and DT (Fig. 3). The C terminus of the deduced ORF1 amino acid sequence contained a 20-fold repeat of the motif PXX, an LPXTG motif, and a hydrophobic stretch of amino acids, and the protein is terminated by 3 positively charged amino acids (Fig. 3). Also present in the S. salivarius FTF was a proline-rich region. Alignment of the proline-rich regions of both FTFs did not yield significant similarities (results not shown). A dendrogram (Fig. 4) constructed on the basis of the alignments of the deduced ORF1 amino acid sequences with some bacterial FTFs revealed that L. reuteri strain 121 FTF is most closely related to FTFs from gram-positive bacteria, in particular, with streptococcal FTFs. Lower degrees of similarity were observed with FTFs from gram-negative bacteria. FTFs of gram-positive bacteria form a separate group from the FTFs of gram-negative bacteria.

FIG. 3.

Multiple sequence alignments of bacterial FTFs. Alignments were made with ClustalW, version 1.74 (41), by using a gap opening penalty of 30 and a gap extension penalty of 0.5. FTF amino acid sequences are from L. reuteri strain 121 (Lb.reut FTF; the ORF1-deduced amino acid sequence from 1,432 to 3,825 bp), S. mutans (S.mut FTF; M18954), and S. salivarius (S.sal FTF; L08445). An asterisk indicates a position with a fully conserved amino acid residue, a colon indicates a position with a fully conserved strong group (STA, NEQK, NHQK, NDEQ, QHRK, MILV, MILF, HY, FYW), and a period indicates a position with a fully conserved weaker group (CSA, ATV, SAG, STNK, STPA, SGND, SNDEQK, NDEQHK, NEQHRK, FVLIM, HFY). Amino acid groups are according to the Pam250 residue weight matrix (2). Key amino acids D349 (38), D424 (6), R541 (8), and G583 (28) and regions with strong homologies among FTFs and invertases (at positions 341 and 354) (36) are shown by letters in boxes. Two N-terminal amino acids (at positions 1 and 10) are underlined and in boldface. The N-terminal amino acid sequence determined from the recombinant FTF is underlined starting at position 39. A signal peptidase cleavage site (between positions 38 and 39) is indicated with an arrow above the sequence. The core region belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 68 (residues 210 to 661) is indicated with a dashed arrow above the sequence. Other features for the strain 121 FTF are a putative spacer region with 20 times the amino acid motif PXX (in bold at positions 699 to 758), a cell wall-anchoring LPXTG motif (underlined at position 764), a hydrophobic stretch of amino acids (in bold at positions 776 to 791), and three positively charged amino acids KRR (underlined at position 794).

FIG. 4.

A dendrogram of bacterial FTFs. Alignments were made with ClustalW, version 1.74 (41), by using a gap opening penalty of 30 and a gap extension penalty of 0.5. Dendrogram construction was done with TreeCon, version 1.3b (42), by using the neighbor-joining method with no correction for distance estimation. The length of the bar indicates 10% difference at the amino acid level. Bootstrap values were all 100% (100 samples). FTFs from gram-positive (G+) bacteria are L. reuteri strain 121 FTF (this work), S. mutans FTF (M18954), S. salivarius FTF (L08445), and B. subtilis SacB (X02730). FTFs from gram-negative (G−) bacteria are G. diazotrophicus LsdA (L41732), Z. mobilis SacB (L33402), and E. amylovora Lsc (X75079).

Blast searches with the deduced amino acid sequence of ORF2 revealed high similarity (41 to 57%) to several members of the uncharacterized protein family UPF0028 (Pfam01173). Similarities were also found with a protein with unknown function from Pastereurella multocida (AAK02722; 39% identity and 60% similarity in 273 amino acids) and with a predicted phosphoesterase from Clostridium acetobutylicum (AAK80379; 34% identity and 54% similarity in 279 amino acids).

Expression of the ftf gene in E. coli and recombinant FTF purification.

Analysis of ORF1 showed that it contained two putative translation start codons. No data were available on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the mature FTF protein. We decided to express ORF1 in E. coli starting from the start codon at position 1432. In total, four ftf derivatives were constructed for expression studies in E. coli. A full-length Inu construct did not yield any transformants. Transformants were obtained with the InuHis construct. Extracts of E. coli Top10 cells containing the InuHis construct clearly possessed sucrose-hydrolyzing activity (1,050 U liter−1). SDS-PAGE of CEs showed the InuHis protein to be present as a smear (results not shown). Furthermore, the protein could not be purified with nickel column purification and antibodies against the poly-His tag could not detect the His tag. Because expression and cloning problems were encountered with the full-length FTF, an FTF variant was constructed with C-terminal truncation from the PXX amino acid residues onwards. Expression of the two truncated ftf derivatives (InuΔ699 and InuΔ699His) in E. coli yielded protein present on SDS-PAGE gels as intense bands, which did not appear to be smeared, at an Mr of about 85,000 and clear FTF activities in E. coli CEs (both at about 1,600 U liter−1). The InuΔ699His protein was purified to homogeneity in two chromatography steps (Table 2). From SDS-PAGE, the Mr of InuΔ699His was estimated to be 84,000 (results not shown). The N-terminal sequence of InuΔ699His was determined as DTNIEN(N)(D) (with ambiguous residues shown between parentheses). These amino acids corresponded to the deduced FTF amino acid sequence following the predicted signal peptidase cleavage site (Fig. 3).

TABLE 2.

Purification of InuΔ699His enzyme from E. coli cells

| Purification step | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U protein mg−1) | Purification (n-fold) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lysate | 631 | 18.0 | 1 | 100 |

| Ni-NTAa | 538 | 88.3 | 4.9 | 85 |

| Resource-Q | 46.0 | 103.7 | 5.8 | 7 |

Nickel resin chromatography purification step.

Basic recombinant FTF enzymatic properties.

The InuΔ699His enzyme showed the highest level of activity at 50°C and pH 5 to 5.5 (measured as glucose release from sucrose in the presence of 1 mM calcium chloride). At 37°C, 50% ± 0.4% enzyme activity was observed (in the presence of 1 mM calcium chloride). In the absence of calcium chloride, the enzyme activity decreased to 79% ± 0.6%.

Analysis of products synthesized from sucrose by L. reuteri wild-type and the recombinant FTF.

Upon incubation with sucrose, the InuΔ699His protein produced both FOS and fructan. After 17 h of incubation with 90 g of sucrose liter−1, 16.5 g of the sucrose liter−1 was consumed and 5.1 g of FOS liter−1 and 0.8 g of fructan liter−1 were synthesized. Furthermore, 2.6 g of fructose liter−1 and 6.0 g of glucose liter−1 were produced from sucrose. Similar amounts of polymer and FOS were produced by CEs of arabinose-induced E. coli with the full-length FTF (InuHis), which might indicate that the C-terminal truncation of FTF does not have a significant effect on product formation. Anion-exchange chromatography (Dionex) (Fig. 5) revealed that the FOS produced were 1-kestose (a β-(2→1) fructosyl unit linked to the fructosyl of sucrose; observed at 6.5 min) and nystose [a β-(2→1) fructosyl unit linked to the terminal fructosyl of 1-kestose; observed at 8.0 min]. In Fig. 5, the large peaks in panels A and B at 5.2 to 6.0 min represent sucrose. Cation-exchange chromatography showed that the majority of FOS was 1-kestose (95%, wt/vol) and a minor amount was nystose (5%, wt/vol). Methylation analysis of the polymer revealed the presence of 93% 3,4,6-tri-O-methylfructose units [β-(2,1) linkages] and 7% 3,4-di-O-methylfructose units [β-(1,2,6)-linked branch points]. HPSEC-MALLS analysis of the in vitro-produced fructan polymer indicated that it was of high molecular weight (>107). In view of the production of inulin polymer by the recombinant FTF, we designated the L. reuteri strain 121 FTF Inu and the corresponding gene inu.

FIG. 5.

Dionex analysis of the FOS synthesized by recombinant InuΔ699His. (A) Analysis of InuΔ699His products; (B) analysis of InuΔ699His products spiked with 1-kestose (6.5 min) and nystose (8.0 min); (C) 1-kestose (6.5 min) and nystose (8.0 min). x axis, retention time (min); y axis, detector response (nA).

As shown previously, L. reuteri culture supernatants incubated with sucrose produced a single fructan (7 g liter−1) with β-(2→6)-linked fructosyl units only (a levan) with an average molecular weight of 150 (43). Searching for Inu activity in L. reuteri strain 121, we analyzed the fructan products of strain 121 grown on medium containing sucrose. In the present study, we observed that L. reuteri incubated with sucrose also produced approximately 10 g of FOS liter−1. These FOS consisted of 1-kestose (95%) and of nystose (5%). Previous experiments have shown that the strain 121 levansucrase protein produces a levan polymer that is not PAS stainable (43). The recombinant InuΔ699His protein produced an inulin polymer that was PAS stainable (results not shown) on SDS-PAGE gels. However, no PAS-stainable polymeric bands were observed with L. reuteri strain 121 cells, CEs, and fractionated cell wall material. Also, incubations of the same fractions in a buffer containing sucrose did not yield inulin polymer.

DISCUSSION

This paper reports the isolation and characterization of the first Lactobacillus (L. reuteri) gene (inu) encoding an FTF (Inu), producing in E. coli a high-molecular-weight inulin with β-(2→1) glycosidic bonds only and inulin FOS (mainly consisting of 1-kestose). FOS production was also observed with L. reuteri strain 121 cells, but no inulin formation was detected. In another work, we have raised antibodies in rabbits against the purified recombinant Inu protein (unpublished results). Unfortunately, no specific immunostaining was observed with L. reuteri cells, culture supernatants, or cell wall material. In these studies, we observed a high background response. Very likely, the rabbits used to raise antibodies contained endogenous lactobacilli. Northern blot hybridization experiments with a probe comprising the region in inu corresponding to the family 68 core region did not reveal the presence of inu mRNA. In summary, FOS synthesis was observed in L. reuteri culture supernatants but the inulin type of fructan produced by the recombinant Inu was not observed in L. reuteri strain 121. Possible explanations for this clear discrepancy are that (i) the inu gene is silent in L. reuteri or not expressed under the growth conditions tested, (ii) the Inu enzyme synthesizes FOS only under the conditions tested in its natural host, (iii) the inulin polymer already has been degraded at the time of harvesting of the cultures (no evidence, however, has been found for the presence of inulin-degrading activities in L. reuteri strain 121 supernatants), or (iv) Inu has activities in E. coli CEs other than those in L. reuteri strain 121. InuHis protein produced in E. coli showed smearing on SDS-PAGE gels, and the His tag could not be detected. These observations may suggest that in E. coli, the InuHis protein is in fact truncated at its C terminus. At present, we cannot exclude the possibility that the products synthesized by the L. reuteri Inu protein are different from the products synthesized by the recombinant InuHis protein.

In the process of cloning the inu gene from L. reuteri strain 121, a PCR step was performed with a specific primer based on the (incomplete) inu sequence (20FTFi) and a degenerate primer based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of a previously purified levansucrase protein from L. reuteri strain 121. Misannealing of the degenerate primer (19FTF) yielded an amplicon overlapping with the inu DNA sequence. This PCR was done at 50°C with a proofreading DNA polymerase. The calculated melting temperature of the DNA sequence to which the primer 19FTF annealed (5′-TAAACGTTTAGCAAAAAGGTAAA-3′) was 36°C (based on the following formula: melting temperature = 2×AT + 4×CG + 4). This result might be explained by a misannealing of the primer at the start of the PCR. A “hot start” involving separation of the DNA polymerase from the PCR mixture at temperatures lower than 90°C ensures that no misannealing takes place (5). Conceivably, no PCR product had been obtained when such a hot start had been used in the PCR involving primers 19FTF and 20FTFi.

A typical secretion signal peptide (26) is present in the N terminus of the Inu protein, with a possible initiation from either translation start codons at positions 1432 and 1459. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified recombinant InuΔ699His protein corresponded to the amino acid sequence following the predicted signal peptidase cleavage site in the deduced Inu sequence. The lack of FTF activity (glucose release from sucrose) in arabinose-induced E. coli (harboring the inu gene) culture supernatants (results not shown) indicates that the recombinant InuΔ699His protein is not secreted by E. coli. N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of the E. coli purified InuΔ699His protein shows that E. coli does cleave the signal sequence from the Inu protein, and thus that the E. coli protein export machinery recognizes the signal sequence. A similar observation was done for the S. salivarius FTF (38). Most likely the Inu protein is present either in the cell membrane, or in the periplasmic space of the E. coli cells.

A cell wall-anchoring motif reported for various gram-positive cell wall-associated proteins (24) was present at the C terminus of the deduced Inu amino acid sequence. It consisted of a 20 times repeat of the amino acids PXX, an LPXTG motif, a hydrophobic domain, and was ended by three positively charged amino acids (Fig. 3). This is the first report of this motif for an FTF enzyme. A model for proteins bearing this cell wall-anchoring motif has been proposed (23). In this model, the stretch of hydrophobic residues acts as a membrane spanning region with the positively charged amino acid residues directed towards the cytosol and the N-terminal part of the protein directed outwards of the cell spaced by a proline-glycine and/or threonine-serine rich region (in the case of Inu the PXX repeats). The LPXTG motif is proteolytically cleaved between the threonine and the glycine residues by a sortase enzyme resulting in a protein covalently linked to the peptidoglycan layer. Major problems arose when attempting to introduce and express the full-length Inu (no transformants) and InuHis (protein smears on gel) constructs in E. coli. Introduction and expression in E. coli of the InuΔ699 and InuΔ699His contructs were straightforward. Apparently the C-terminal region of Inu is problematic for the E. coli protein expression machinery.

The products of Inu incubated with its substrate sucrose were mainly 1-kestose and an inulin of high molecular weight. High-molecular-weight inulin production was reported before only in S. mutans sp. (9, 12, 32). The inulin polymers produced by these streptococci, however, contain β-(2→6) branches (5%). Exclusive production of 1-kestose has been reported for Aspergillus niger (18). Plant FTFs are known to synthesize 1-kestose as primer for the production of inulin polymers (46). The combined production of 1-kestose and a levan polymer has been reported for the G. diazotrophicus levansucrase enzyme (17). The combination of the production of 1-kestose and levan is remarkable, because levan polymers consist of β-(2→6)-linked fructosyl units, while 1-kestose consists of a β-(2→1) fructosyl unit coupled to sucrose. The production of 1-kestose by Inu is the first elongation step in the polymerization reaction. The large amounts of FOS formed under the incubation conditions used thus may represent aborted polymerization attempts of the Inu enzyme.

The deduced amino acid sequence of the Inu protein of the generally regarded as safe bacterium L. reuteri shows highest homology to FTFs from streptococcal origin. Streptococci are well-studied inhabitants of the oral cavity, with fructan synthesized from sucrose most likely contributing to the cariogenicity of dental plaque formation (33). L. reuteri strains, in contrast, are residents of the mammalian gut system. It will be interesting to study the in situ functional properties of L. reuteri strain 121 and the fructans produced and their possible roles in the probiotic properties attributed to L. reuteri strains (11, 30).

Previously, we reported the presence of a levansucrase in L. reuteri strain 121 (43, 44). Here we report the isolation and characterization of a novel inulosucrase-encoding gene from L. reuteri strain 121. Southern hybridization studies under non-stringent conditions with two probes against the inulosucrase gene and strain 121 chromosomal DNA revealed one hybridizing band. The N-terminal sequence as well as the internal amino acid sequences determined for the purified levansucrase from L. reuteri strain 121 (44) could not be identified in the deduced strain 121 inulosucrase sequence. L. reuteri strain 121 thus contains both a levansucrase gene and an inulosucrase gene. Apparently, these two ftf genes are significantly different not only in products formed, but also in amino acid sequence.

Future work will involve (i) a detailed biochemical characterization of the recombinant Inu enzyme and (ii) inu gene expression studies in L. reuteri strain 121. This will enable a more detailed investigation of the catalytic mechanism of FTF enzymes producing inulin polymers, and analysis of the Inu activities and products in L. reuteri itself. The biological relevance and potential health benefits of an inulosucrase associated with a L. reuteri strain remain to be established.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jos van der Vossen, Egbert Smit, Koen Venema, and Dick van den Berg for their contributions to the isolation of the inu gene, Isabel Capron for the determination of the molecular weights of the fructans, Elly Faber for methylation analyses, and Gert-Jan Euverink for support in E. coli expression studies.

This project was partly financed by the EET programme of the Dutch government (project number KT 97029), by TNO Nutrition and Food Research, and by the University of Groningen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aduse-Opoku, J., M. L. Gilpin, and R. R. Russell. 1989. Genetic and antigenic comparison of Streptococcus mutans fructosyltransferase and glucan-binding protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 50:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., B. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 4.Balakrishnan, M., R. S. Simmonds, and J. R. Tagg. 2000. Dental caries is a preventable infectious disease. Aust. Dent. J. 45:235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassam, B. J., and G. Caetano-Anolles. 1993. Automated “hot start” PCR using mineral oil and paraffin wax. BioTechniques 14:30-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batista, F. R., L. Hernández, J. R. Fernandez, J. Arrieta, C. Menéndez, R. Gomez, Y. Tambara, and T. Pons. 1999. Substitution of Asp-309 by Asn in the Arg-Asp-Pro (RDP) motif of Acetobacter diazotrophicus levansucrase affects sucrose hydrolysis, but not enzyme specificity. Biochem. J. 337:503-506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casas, I. A., F. W. Edens, and W. J. Dobrogosz. 1988. Lactobacillus reuteri: an effective probiotic for poultry and other animals, p. 475-518. In S. Salminen and A. Von Wright (ed.), Lactic acid bacteria: microbiological and functional aspects. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 8.Chambert, R., and M. F. Petit-Glatron. 1991. Polymerase and hydrolase activities of Bacillus subtilis levansucrase can be separately modulated by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem. J. 279:35-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrigan, A. J., and J. F. Robyt. 1979. Nature of the fructan of Streptococcus mutans OMZ 176. Infect. Immun. 26:387-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Man, J. C., M. Rogosa, and M. E. Sharpe. 1960. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 23:130-135. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Roos, N. M., and M. B. Katan. 2000. Effects of probiotic bacteria on diarrhea, lipid metabolism, and carcinogenesis: a review of papers published between 1988 and 1998. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71:405-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebisu, S., K. Kato, S. Kotani, and A. Misaki. 1975. Structural differences in fructans elaborated by Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus salivarius. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 78:879-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson, G. R., C. L. Willis, and J. Van Loo. 1994. Non-digestible oligosaccharides and bifidobacteria—implications for health. Int. Sugar J. 96:381-387. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross, M., G. Geier, K. Rudolph, and K. Geider. 1992. Levan and levansucrase synthesized by the fireblight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 40:371-381. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock, R. A., K. Marshall, and H. Weigel. 1976. Structure of the levan elaborated by Streptococcus salivarius strain 51: an application of chemical-ionisation mass-spectrometry. Carbohydr. Res. 49:351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Havenaar, R., and J. H. J. Huis in't Veld. 1992. Probiotics: a general view. In B. J. B. Wood (ed.), The lactic acid bacteria in health and disease. Elsevier, New York, N.Y.

- 17.Hernández, L., J. Arrieta, C. Menéndez, R. Vazquez, A. Coego, V. Suarez, G. Selman, M. F. Petit-Glatron, and R. Chambert. 1995. Isolation and enzymic properties of levansucrase secreted by Acetobacter diazotrophicus SRT4, a bacterium associated with sugar cane. Biochem. J. 309:113-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hidaka, H., M. Hirayama, and N. Sumi. 1988. A fructooligosaccharide-producing enzyme from Aspergillus niger ATCC 20611. Agric. Biol. Chem. 52:1181-1187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansson, P. E., L. Kenne, H. Liedgren, B. Lindberg, and L. Lönngren. 1976. A practical guide to the methylation analysis of carbohydrates. Chem. Commun. (J. Chem. Soc. Sect. D) 8:1-74. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamerling, J. P., and J. F. G. Vliegenthart. 1989. Mass spectrometry, p. 176-263. In A. M. Lawsen (ed.), Clinical biochemistry: principles, methods, applications. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany.

- 21.Kapitany, R. A., and E. J. Zebrowski. 1973. A high resolution PAS stain for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 56:361-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leenhouts, K., G. Buist, and J. Kok. 1999. Anchoring of proteins to lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 76:367-376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mesnage, S., E. Tosi-Couture, and A. Fouet. 1999. Production and cell surface anchoring of functional fusions between the SLH motifs of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer proteins and the Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Mol. Microbiol. 31:927-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagy, I., G. Schoofs, F. Compernolle, P. Proost, J. Vanderleyden, and R. De Mot. 1995. Degradation of the thiocarbamate herbicide EPTC (S-ethyl dipropylcarbamothioate) and biosafening by Rhodococcus sp. strain NI86/21 involve an inducible cytochrome P-450 system and aldehyde dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 177:676-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. Von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oda, M., H. Hasegawa, S. Komatsu, M. Kambe, and F. Tsuchiya. 1983. Antitumour polysaccharide from Lactobacillus sp. Agric. Biol. Chem. 47:1623. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petit-Glatron, M. F., I. Monteil, F. Benyahia, and R. Chambert. 1990. Bacillus subtilis levansucrase: amino acid substitutions at one site affect secretion efficiency and refolding kinetics mediated by metals. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2063-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pouwels, P. H., and R. J. Leer. 1993. Genetics of lactobacilli: plasmids and gene expression. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 64:85-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberfroid, M. R. 1993. Dietary fiber, inulin, and oligofructose: a review comparing their physiological effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 33:103-148. (Erratum, 33:553, 1993.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robyt, J. F., and T. F. Walseth. 1979. Production, purification, and properties of dextransucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-512F. Carbohydr. Res. 68:95-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosell, K. G., and D. Birkhed. 1974. An inulin-like fructan produced by Streptococcus mutans strain JC2. Acta Chem. Scand. B28:589. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Rozen, R., G. Bachrach, M. Bronshteyn, I. Gedalia, and D. Steinberg. 2001. The role of fructans on dental biofilm formation by Streptococcus sobrinus, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus gordonii and Actinomyces viscosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 195:205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Sato, S., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 1986. Isolation and characterization of a fructosyltransferase gene from Streptococcus mutans GS-5. Infect. Immun. 52:166-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato, Y., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 1988. Sequence analysis of the Streptococcus mutans scrB gene. Infect. Immun. 56:1956-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiffrin, E. J., F. Rochat, H. Link-Amster, J. M. Aeschlimann, and A. Donnet-Hughes. 1995. Immunomodulation of human blood cells following the ingestion of lactic acid bacteria. J. Dairy Sci. 78:491-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song, D. D., and N. A. Jacques. 1999. Mutation of aspartic acid residues in the fructosyltransferase of Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975. Biochem. J. 344:259-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinmetz, M., D. Le Coq, S. Aymerich, G. Gonzy-Treboul, and P. Gay. 1985. The DNA sequence of the gene for the secreted Bacillus subtilis enzyme levansucrase and its genetic control sites. Mol. Gen. Genet. 200:220-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang, L. B., R. Lenstra, T. B. Borchert, and V. Nagarajan. 1990. Isolation and characterization of levansucrase encoding gene from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Gene 96:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van de Peer, Y., and R. De Wachter. 1994. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput. Applic. Biosci. 10:569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Geel-Schutten, G. H., E. J. Faber, E. Smit, K. Bonting, M. R. Smith, B. Ten Brink, J. P. Kamerling, J. F. G. Vliegenthart, and L. Dijkhuizen. 1999. Biochemical and structural characterization of the glucan and fructan exopolysaccharides synthesized by the Lactobacillus reuteri wild-type strain and by mutant strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3008-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Hijum, S. A. F. T., K. Bonting, M. J. E. C. van der Maarel, and L. Dijkhuizen. 2001. Purification of a novel fructosyltransferase from Lactobacillus reuteri strain 121 and characterization of the levan produced. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:323-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verhasselt, P., F. Poncelet, K. Vits, A. Van Gool, and J. Vanderleyden. 1989. Cloning and expression of a Clostridium acetobutylicum alpha-amylase gene in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 50:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vijn, I., and S. Smeekens. 1999. Fructan: more than a reserve carbohydrate? Plant Physiol. 120:351-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yanase, H., M. Iwata, R. Nakahigashi, K. Kita, N. Kato, and K. Tonomura. 1992. Purification, crystallization and properties of the extracellular levansucrase from Zymomonas mobilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 56:1335-1337. [Google Scholar]