Abstract

Introduction

Menstrual inequity refers to the systematic and avoidable differences experienced by women and people who menstruate, based on having a menstrual cycle and menstruating. Given the paucity of prior research examining the impact of menstrual inequity on health, a scoping review was conducted to explore and map out the menstrual inequities and their association with health outcomes in women and people who menstruate within the published academic literature.

Methodology

Two searches were conducted in May 2022 and March 2024 in PubMed and Scopus. Academic literature published until December 2023 was included. Following the screening process, 74 articles published between 1990 and 2023 were included in the review. Results were then synthesised through narrative analysis and organised into nine categories.

Results

A range of both physical and emotional health outcomes were documented to be associated with menstrual inequity. Urinary tract infection, reproductive tract infection, and other genital discomforts (e.g. itching) were linked to certain menstrual discomforts (e.g. dysmenorrhea) as well as a lack of access to menstrual products, menstrual management facilities and/or menstrual information. The emotional health outcomes, especially anxiety, distress and depression, were salient and were shown to be related to menstrual stigma, the lack of menstrual information and the limited access to menstrual-related healthcare.

Conclusions

The majority of the included studies were focused on menstrual management, being one of the most addressed themes concerning menstruation, and the health outcomes were mainly reproductive tract infection and emotional/mental health. Expanding the range of health outcomes studied will strengthen research and inform policy. Further research is needed to better understand the complex association between menstrual inequities and other potential health outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12978-025-02103-0.

Keywords: Menstrual inequity, Menstruation, Social determinants of health, Health outcomes, Emotional health, Reproductive tract infections, Scoping review

Plain Language summary

Menstruation and the menstrual cycle are connected to the overall health of women and other people who menstruate. Menstrual inequity refers to the unfair situations and barriers that women and people who menstruate face because they menstruate. These include not having access to proper menstrual healthcare, menstrual education and knowledge, menstrual products, lacking services and facilities for menstrual management, experiencing menstrual stigma and discrimination, and the ability to fully participate in social, community, political and economic spheres. All these challenges can have an impact on their overall health. This study had the objective to explore these menstrual inequities and their association with health outcomes in women and people who menstruate in the published academic literature. We included information from 74 articles published until December 2023. The findings showed that menstrual inequity is linked to various health issues. For example, physical healthproblems, like urinary or reproductive tract infections, were often linked to difficulties managing menstruation. Moreover, emotional health issues like anxiety, distress, and depression were connected to experiences of menstrual stigma and discrimination, and having limited access to menstrual healthcare and education. This review also found that more research is needed about the relationship between menstrual inequity and health outcomes to fully understand how menstrual inequity affects women and people who menstruate. By doing so, researchers can provide better information to guide policies and improve health of women and people who menstruate.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12978-025-02103-0.

Resumen

Introducción

La inequidad menstrual se refiere a las diferencias sistemáticas y evitables que experimentan las mujeres y las personas que menstrúan, basadas en el hecho de tener un ciclo menstrual y menstruar. Dada la escasez de investigaciones previas que examinen el impacto de la inequidad menstrual en la salud, se llevó a cabo una revisión de alcance para explorar y mapear las inequidades menstruales y su asociación con los resultados de salud en mujeres y personas que menstrúan dentro de la literatura académica publicada.

Metodología

Se realizaron dos búsquedas en mayo de 2022 y marzo de 2024 en PubMed y Scopus. Se incluyó la literatura académica publicada hasta diciembre de 2023. Tras el proceso de cribado, se incluyeron en la revisión 74 artículos publicados entre 1990 y 2023. Los resultados se sintetizaron mediante un análisis narrativo y se organizaron en nueve categorías.

Resultados

Se documentaron una serie de resultados en salud, tanto físicos como emocionales, asociados a la inequidad menstrual. Las infecciones del tracto urinario, las infecciones del tracto reproductivo y otras molestias genitales (p. ej., picor) se relacionaron con ciertas molestias menstruales (p. ej., dismenorrea), así como con la falta de acceso a productos menstruales, instalaciones para la gestión menstrual y/o información menstrual. Los resultados de salud emocional, especialmente la ansiedad, la angustia y la depresión, se destacaron y se demostró que estaban relacionados con el estigma menstrual, la falta de información menstrual y el acceso limitado a la asistencia sanitaria relacionada con la menstruación.

Conclusiones

La mayoría de los estudios incluidos se centraron en el manejo menstrual, siendo uno de los temas más abordados en relación con la menstruación, y los resultados en salud principalmente reportados fueron las infecciones del tracto reproductivo y la salud emocional/mental. Ampliar la variedad de resultados en salud fortalecerá la investigación y orientará las potenciales políticas. Es necesario realizar investigaciones para comprender mejor la compleja relación entre las inequidades menstruales y otros posibles resultados en salud.

Palabras Clave: Inequidad menstrual, Menstruación, Determinantes Sociales de la Salud, Resultados en Salud, Salud emocional, Infecciones del Sistema Genital, Revisión de Alcance

Introduction

Menstruation, the menstrual cycle and how they are related to the overall health of women and people who menstruate (PWM) is a widely under-prioritized topic in both the academic, social and political field [1, 2]. This corresponds to a well-documented gender bias within health that continues to persist, manifesting itself, among other things, as an underrepresentation of women in health-related studies, misdiagnosis of women’s symptoms, the trivialization of women’s complaints, and discrimination in the awarding of research grants towards female researchers and research on women’s health [3]. This disregard of health conditions that disproportionately affect women is rooted in the all-encompassing tendency for society, its institutions, discourses and norms, to be centred around (white, cis-gendered, heterosexual, able-bodied) men and their needs, values and priorities, consequently prioritizing the male experience and marginalizing any other experience - such as menstruation [4, 5].

We understand menstrual inequities (MI) as a concept grounded in health equity and social inequities frameworks. Medina-Perucha et al., 2023 define MI as “the systematic and avoidable differences in the access to menstrual healthcare, education and knowledge, products, services and facilities for menstrual management, menstrual related experiences of stigma and discrimination, and social, community, political and economic participation based on having a menstrual cycle and menstruating” [6]. This umbrella term encompasses fundamental dimensions of MI, such as menstrual poverty (the struggle to afford menstrual products) [7] and menstrual management [8], menstrual healthcare, experiences of stigma and discrimination, and social, community, political and economic participation. These dimensions often intersect and overlap, maintaining and reinforcing health inequities for women and PWM. Framing these dimensions within the broader concept of MI allows for attending to how such inequities are a structural issue, rather than an individual one. Table 1 illustrates a conceptualisation of the relations between these concepts.

Table 1.

Relationship between menstrual inequity (MI) and its components

| Concept | Definition | Relationship with menstrual inequity |

|---|---|---|

| Access to menstrual healthcare | The access to timely diagnosis, treatment and care for menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders, including access to appropriate health services and resources, pain relief, and strategies for self-care [9]. | Menstrual inequity occurs when healthcare systems do not recognise and prioritise menstrual health. This can result in delayed, inaccurate diagnoses, unnecessary medicalisation, dismissal of symptoms, among other issues. Menstrual inequities do not, however, exist in isolation and also intersect with other types of (health) inequities such as race, class, gender etc. Moreover, there are barriers (e.g., economic, geographic) that limit the access to specialised menstrual healthcare for some women and PWM. |

| Access to menstrual products and menstrual poverty | The ability to obtain safe, effective, and affordable menstrual materials (e.g., cups, pads, tampons). Limited access to these products is known as “menstrual poverty”. We understand and classify menstrual poverty in three types: (1) not being able to afford menstrual products, (2) not being able to afford preferred products, and (3) having to prioritize menstrual products over other products or activities [1]. | Menstrual poverty is a material expression of menstrual inequity. Menstrual poverty not only highlights inequities related to menstruation and the menstrual cycle, but also reveals other inequities such as financial hardship and poverty. |

| Menstrual related experiences of stigma and discrimination | Menstrual stigma and discrimination are the result of complex social notions manifesting as negative attitudes towards menstruation. Menstrual discrimination refers to marginalization, oppression, harassment or even microaggressions directed at individuals because they menstruate and have a menstrual cycle [10, 11]. | Menstrual stigma and discrimination are both an expression of and contributing factors to menstrual inequities. Menstrual stigma and discrimination have a wide range of negative consequences for women and PWM’s health, sexuality, wellbeing and social status. It furthermore upholds social and institutional barriers limiting access to resources, information, healthcare and supportive environments perpetuating social exclusion. |

| Access to menstrual management | The access to clean menstrual management is defined as access to materials to absorb and collect blood, that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of the menstruation, soap and water for washing the body as required and having access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials [12]. Other definitions also specify that menstrual management facilities are clean spaces, where water is available and include a bin and can be locked [1]. Many definitions are based on the use of ‘menstrual hygiene management (MHM)’ although we choose not to use the term ‘hygiene’ because of the connotations associating menstruation with a lack of cleanliness. | The lack of access to menstrual management reflects menstrual inequity, as insufficient possibilities to manage menstruation with dignity, which can affect health and social participation. Barriers that limit access to menstrual management are expressions of systems that reproduce a variety of inequities not limited to menstrual inequity (e.g., gender, class, territoriality). These structural inequities shape the material and social conditions that hinder safe and dignified menstrual management for women and PWM. |

| Access to menstrual education and knowledge | The access to accurate, timely, age-appropriate information about the menstrual cycle, menstruation, and changes experienced throughout the life-course, as well as related self-care and hygiene practices [9]. | A lack of access to menstrual education and knowledge directly contributes to menstrual inequity, as it limits (self-)knowledge about the body and menstruation-related processes. In some contexts, menstrual education has been provided incompletely or predominantly with a biomedical focus, leaving out important information on self-care and socio-cultural aspects of menstruating. This prevents a comprehensive understanding of the menstrual cycle. |

| Access to social, community, political, and economic participation | Being able to participate in all spheres of life refers to being able to decide whether and how to participate in the civil, cultural, economic, social, and political spheres, during all phases of the menstrual cycle, free from menstrual-related exclusion, restriction, discrimination, and/or violence [9]. | The access to social, community, political and economic participation are closely linked to other dimensions of menstrual inequity, such as access to adequate menstrual management, freedom from menstrual stigma and discrimination, and acquisition of menstrual education and information, among others. When women and PWM face barriers through lack of access to resources and education, or the presence of stigma and discrimination, their full participation cannot be realised. |

The concept of MI serves to draw attention towards how androcentric social structures (which prioritise cis male experiences and perspectives) systematically stigmatise menstruation [13]. Several frameworks have been applied within research to investigate systemic menstrual-related disparities, such as the menstrual justice framework [14] or the human rights framework [15]. Both approaches emphasize how political and economic structures are shaped by different axes of domination generating disadvantages, oppression and violations of the fundamental rights of women and PWM [14, 16, 17]. They do not, however, directly engage with how these systematic inequities affect the health of women and PWM.

The urgency of examining health outcomes linked to MI is alternatively underscored by the social determinants of health (SDH) framework. This framework highlights how the circumstances in which people are born, grow, work, and live significantly impact their health [18]. SDH thus include (but is not limited to) economic policies and systems, development agendas, cultural norms, social policies and political systems [18, 19]. SDH plays an important role in producing and upholding health inequities and have been argued to be even more determining of an individual’s health than healthcare or lifestyle choices [18, 20]. Reducing (menstrual) inequities thus requires systemic changes to the SDH, addressing social, economic, and environmental conditions.

Previous research on the health outcomes posed by MI have demonstrated the risk of bacterial infections [21], barriers in the access to adequate diagnosis (and treatment) of menstrual health-related conditions (e.g. endometriosis) [22], a negative impact on mental health [2], and misinformation regarding the menstrual cycle generating subsequent negative health outcomes such as psychological stress [23]. Menstrual experiences like endometriosis, menstruations perceived to be irregular, and menstruations characterized by heavy bleeding or pain, have been demonstrated to be associated with lower quality of life and wellbeing and higher rates of mental health diagnoses [2]. In a similar manner, the experience of menstrual poverty has been shown to be associated with depressive symptoms [24], anxiety, and reproductive and urinary tract infections [25]. Additionally, Holmes et al. (2021) have demonstrated how the normalisation of certain menstrual health issues, such as dysmenorrhea, further prevents women and PWM to seek and receive proper healthcare treatment [23]. Much of this investigation focuses on geographical contexts in the Global South1, but is mainly developed, conducted, and funded by researchers and institutions in the Global North1. The formulation of research questions, the definition of research subjects, and the theoretical frameworks in menstrual studies are thus often permeated by Western cultural notions, reinforcing predominant global power structures [26–28]. Despite largely being studied in the Global South it has been demonstrated that MI transcend geographical, cultural and socioeconomic status, and therefore are equally relevant in the Global North1 [6, 23, 29].

While previous literature reviews have been looking into how menstrual management, menstrual poverty and menstrual health literacy affect the (menstrual) health of women and PWM [21, 23, 30–32], little inquiry has so far been carried out to explore how MI, as an umbrella term, may impact the health of women and PWM [6]. The aim of this scoping review is to explore and map the components of MI and their association with health outcomes in women and PWM, as reported inthe published academic literature.

Methods

A scoping review of academic literature was carried out to identify original research articles on health outcomes and their association with MI. This study followed the PRISMA guidelines (see Additional file 1) [33] and was registered in Open Science Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/ZU73X).

Conceptual framework

This study adopts a critical feminist perspective, recognizing that systemic and structural patriarchal powers in society have an impact on health [34–36]. This approach implies using a social equity lens to conduct research that promotes collective freedom, justice, and equity [37]. Moreover, the SDH framework [38] was used to guide the identification of determinants implied in health outcomes related to menstrual experiences and health. This theoretical framework, in conjunction with the feminist perspective of the review, served as the guiding principle throughout the review process, particularly in the inductive identification of themes within the results. While the results will be presented descriptively for the purpose of facilitating comprehensibility, the structure of the analysis was informed by these frameworks.

The research has furthermore incorporated the practice of reflexivity, which included a critical examination of current approaches to MI in the literature [39]. Considering this, the research team conducted the study based on the following definitions:

Menstrual inequity: the systematic and avoidable differences in the access to menstrual healthcare, education and knowledge, products, services and facilities for menstrual management, menstrual related experiences of stigma and discrimination, and social, community, political and economic participation based on having a menstrual cycle and menstruating [6].

Health outcomes: any physical, psychological or emotional health-related symptom or condition. This is aligned with the WHO’s concept of health, defined as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [40]. This broad definition was necessary to reflect the wide variety of health implications related to the menstrual cycle and MI, including not only physical but mental and emotional health outcomes. We define emotional health based on a definition on emotional well-being as “an umbrella term for psychological concepts such as life satisfaction, life purpose, and positive emotions” [41].

Social determinants of health: the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life (e.g. economic policies and systems). The SDH have an important influence on health inequities [42, 43].

Given that SDH may influence menstrual experiences and related health outcomes [44], it is important to consider how MI are associated with health outcomes. This review is based on the perspective that health is a social issue and that social inequities determine health outcomes, which are distributed unequally across populations [7, 45]. Although the focus of the review is on inequities, the SDH framework is used to first understand how social inequities arise in relation to menstruation and menstrual health.

Searches

The search was conducted in two databases: PubMed and Scopus. The search was performed in May 2022 and updated in March 2024. This second search was conducted to include recently published articles. The search strategy included the following terms: “menstrual health and hygiene”, “menstrual hygiene management”, “menstrual management”, “menstrual health”, “menstrual poverty”, “period poverty”, “menstrual equit*”, “menstrual inequit*”, “menstrual product*”, “menstrual hygiene product*”, “menstrual education”, and “menstrual knowledge” (see Additional file 2). The search was conducted by GPD and LMP.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they were [1] original research articles of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods methodologies [2], published until December 2023 [3], in English or Spanish [4], considered at least one health outcome associated with one menstrual inequity dimension (e.g., menstrual poverty, menstrual education, etc.), and focused on [5] women and PWM. No restrictions for age or geographical areas were applied.

Reasons for exclusion were: [1] not focused on menstruation-related SDH [2], publications not including primary data and certain study designs (protocols, evaluations, intervention/pilot studies, conference papers, guidelines, case studies, theoretical framework or questionnaire development studies, editorials, commentaries, viewpoints, systematic literature reviews or meta-analyses, and other review designs) [3], not include any mention or exploration of a relation between one menstrual inequity dimension (e.g., menstrual poverty, menstrual education, etc.) and health outcomes [4], unavailable full-text, and [5] studies not published in English or Spanish. Studies focusing solely on menstrual experiences without a reference to health consequences were not included. This allowed us to map a broad range of evidence, including descriptive studies, while staying aligned with the aim.

Screening process

A total of 4,009 articles were included in the screening process. The screening process consisted of three phases: Phase (I) Title and abstract screening, after deleting duplicates (n = 2,863); Phase (II) Full-text screening (n = 465); Phase (III) Review of full-text screening (n = 96). The screening process was conducted between May and December 2022, and between March and April 2024 (once the search was updated). At the end 74 articles were included in the review. GPD and LMP performed the whole screening process; AGE performed the full-text screening and the review of full-text screening; ASH and ABH collaborated in the full-text screening of some studies. In all screening phases, some articles were triangulated by the members of the research team. The researchers met regularly to discuss and triangulate the screening process and to resolve any disagreements in the inclusion and exclusion of articles. When consensus was not reached, a third reviewer was introduced to make the final decision. This collaborative and reflective approach ensured consistency and transparency in decision-making, in line with good practice recommended for exploratory reviews. The Rayyan software [46] was used to facilitate the screening process. See Fig. 1 for more details on the screening process.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart of study screening process. *Several studies were excluded for multiple reasons, so the sum of these is not equivalent to the total of excluded articles

Data extraction

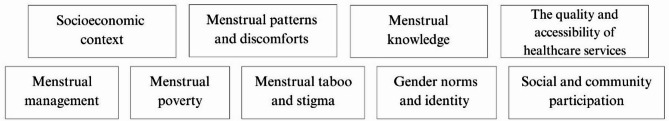

Data of the 74 articles were extracted and included in an Excel sheet by AGE, GPD, ASH, ABH, and LMP (February-October 2023), and by AGE, GPD, and ABH (April-May 2024). Data extraction included publication and methodological characteristics (authors, title, year of publication, geographical and period context, objective, methods, study population characteristics, sample, area of study), relevant findings (health outcomes, SDH and the association between health outcomes and SDH), and quality evaluations (see Table 2). The studies were classified according to different categories, which were constructed based on the definitions of MI and the SDH framework. These categories comprised: [1] socioeconomic context [2], menstrual patterns and discomforts [3], menstrual knowledge [4], the quality and accessibility of healthcare services [5], menstrual management [6], menstrual poverty [7], menstrual taboo and stigma [8], gender norms and identity, and [9] social and community participation (see Fig. 2). 22 articles were excluded at the data extraction stage, as they did not focus on health outcomes, or they did not include associations between health outcomes and menstruation-related SDH. The results were summarised according to the categories.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of included studies (n = 74)

| Reference | Country of data collection | Methodology and design | Study population | Age of participants | Sample size | Area of study | Health outcome(s) | Quality score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camas-Castillo et al., 2023 | Brazil (Campinas, São Paulo) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult and adult women | 18-49y | n = 415 | Menstrual management | Psychological quality of life | 17/22 |

| Ssemata et al., 2023 | Uganda (Wakiso and Kalungu districts) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews, focus group discussions) | Adolescents and young adult students (girls and boys) | 15-24y | n = 274 (in-depth interviews), n = 600 (26 focus groups) | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Shame, fear, feeling uncomfortable | 18/20 |

| Marí-Klose et al., 2023 | Spain (Barcelona) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult and adult women | 15-34y | n = 647 | Menstrual poverty | Poor mental health | 22/22 |

| Schmitt et al., 2023 | United States (all territories) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Young adult women | 18-25y | n = 25 | Menstrual poverty | Feeling vulnerable, anxiety | 17/20 |

| Borg et al., 2023 | Uganda (Mukono District) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult and adult women | 18-45y | n = 499 | Menstrual management | Urogenital symptoms | 22/22 |

| Babbar et al., 2023 | India (not specified) | Qualitative (secondary analysis of qualitative data from an online survey) | Young adult and adult women | 18-49y | n = 140 | Menstrual poverty | Concern | 15/20 |

| Getahun et al., 2023 | Ethiopia (Dilla) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Young adult women | Mean age 21.55y (± SD = 1.191) | n = 20 | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services | Fears of become addicted to menstrual pain medication, concern | 16/20 |

| Mohammed et al., 2023 | United States and United Kingdom (not specified) | Qualitative (critical approach to transcribed data) | Adolescent girls | 13-19y | n = 15 | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services | Uncertainty | 17/20 |

| Boden et al., 2023 | United States (St. Louis, Missouri) | Qualitative (content analysis) | Adult women | 19-65y | n = 32 | Menstrual management, Menstrual poverty, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Discomfort, anxiety, embarrassment, fatigue, moodiness | 19/20 |

| ElBanna et al., 2023 | United States (St. Louis, Missouri) | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Adult women | 18-50y | n = 15 | Menstrual management | Pain, embarrassment, feelings of dehumanization, (di)stress | 18/20 |

| Choudhary et al., 2023 | India (New Delhi) | Qualitative (interviews) | Young adult and adult women | 18-40y | n = 20 | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Stress, frustration, anger, embarrassment, humiliation, shame, worry and concern. | 11/20 |

| Betsu et al., 2023 | Ethiopia (rural Tigray) | Qualitative (interviews, focus groups) | Adolescent girls | 13-18y | n = 79 | Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Menstrual anxiety, self-confidence, feeling uncomfortable | 14/20 |

| Varshney & Kimport, 2023 | United States (not specified) | Qualitative (narrative analysis) | Adolescents, young adult and adult women | 9-39y | n = 32 | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services, Social and community participation | Emotional anxiety, anxiety of feeling alone | 12/20 |

| Chan et al., 2023 | United States (all territories) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Young adult and adult women | 21-50y | n = 32 | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services | Health consequences being on the wrong medication, medical trauma | 18/20 |

| Sadique et al., 2023 | Pakistan (Sindh province) | Qualitative (interviews, discussion groups) | Adolescents and adult women | Not specified | Not specified | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Feeling uncomfortable, rashes, itching, vaginal infections, urinary tract infections, embarrassment, discomfort, shyness, afraid being teased by men | 13/20 |

| Hennegan et al., 2022 | Uganda (Mukono District) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult and adult women | 18-45y | n = 600 | Menstrual management, Social and community participation | Urinary tract infections, discomfort | 22/22 |

| Winter et al., 2022 | Kenya (Mathare informal settlement, Nairobi) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Young adult and adult women | 18-55y | n = 55 | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Embarrassment, concern, shame, fears of harassment, fears of contracting infections, frustration | 18/20 |

| Adib-Rad et al., 2022 | Iran (not specified) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult women | 18-20y | n = 340 | Socioeconomic context | Psychological distress | 17/22 |

| Cherenack & Sikkema, 2022 | Tanzania (not specified) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 13-21y | n = 701 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual knowledge | Reproductive tract infections | 21/22 |

| Alshdaifat et al., 2022 | Jordan (all territories) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult women | Mean age 21.6y (± SD = 2.2) | n = 594 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts | Stress | 17/22 |

| Mariappen et al., 2022 | Malaysia (Klang Valley) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescent girls | 13-18y | n = 1,050 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual management | Quality of life | 16/22 |

| Buitrago-García et al., 2022 | Burkina Faso (Kossi Province) | Qualitative** (photo-elicitation) | Adolescents and young adult women | 12-28y | n = 56 (focus groups), n = 30 individual interviews | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Discomfort, concern, shame, feeling unsafe, fear, humiliation. | 15/20 |

| Deriba et al., 2022 | Ethiopia (North Shewa Zone) | Qualitative** (in-depths interviews) | Adolescent girls | 13-19y | n = 12 | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual management | Concern, fear | 16/20 |

| Ní Chéileachair et al., 2022 | Ireland (all provinces and Northern Ireland) | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Adult women | ≥ 18y | n = 21 | Social and community participation | Feeling guilty, fears of discrimination | 19/20 |

| Boyers et al., 2022 | United Kingdom (England) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews, focus group discussions) | Adult women | ≥ 18y | n = 32 | Menstrual taboo and stigma | Shame, anxiety | 18/20 |

| Daniels et al., 2022 | Cambodia (2 rural provinces) | Mixed-methods (quantitative: cross-sectional; qualitative: structured interviews, focus group discussions) | Adolescent girls | ≥ 14y | n = 75 (structured interviews), n = 55 (focus group) | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Fear, shyness, discomfort, social anxiety | 18/20 |

| Swe et al., 2022 | Myanmar (Magway Region) | Mixed-methods (quantitative: cross-sectional; qualitative: structured interviews, focus group discussions) | Adolescent girls | 11-16y | n = 421 (quantitative study); n = 10 interviews, n = 10 focus groups (qualitative study) | Menstrual taboo and stigma | Shyness, embarrassment, fear, distress | 16/20 |

| McGregor & Unsworth, 2022 | Australia (urban areas, not specified) | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Young adult and adult women | 16-70y | n = 6 | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Confidence issues, concerns, embarrassment, awkwardness, frustration, comfortability | 15/20 |

| Schmitt et al., 2022 | United States (Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Adolescent girls | 15-19y | n = 12 | Menstrual knowledge | Distress | 17/20 |

| Ames & Yon, 2022 | Peru (Huancavelica, Lima, Loreto, and Ucayli regions) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Adolescent girls | 10-17y | n = 277 | Menstrual taboo and stigma | Fear of being ridiculed, discomfort, shame | 14/20 |

| Asumah et al., 2022 | Ghana (West Gonja, Savannah Region) | Qualitative (exploratory study) | Adolescent girls | 13-19y | n = 18 | Menstrual management | Discomfort and illness | 9/20 |

| Wilbur et al., 2022 | Vanuatu (Torba and Sanma Provinces) | Mixed-methods (quantitative: case-control; qualitative: in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, Photovoice) | Adolescents, young adult and adult menstruators | 10-45y | n = 164 (menstruators with disabilities), n = 169 (menstruators without disabilities) | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Pain, fear, shame | 18/20 |

| Gouvernet et al., 2022 | France (not specified) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adult women | 18-50y | n = 890 | Menstrual poverty | Depression and anxiety | 22/22 |

| Sommer et al., 2022 | United States (not specified) | Quantitative (cohort) | Adult women | > 18y | n = 1,496 | Menstrual poverty, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Stress | 19/22 |

| Shah et al., 2022 | Gambia (rural Kiang districts) | Mixed-methods (two cross-sectional surveys; focus group discussions, in-depth interviews, menstrual diaries, and school WASH facility observations) | Adolescents and young adult women | 11-25y (quantitative study); mean age 15.7–17.5 (qualitative study) | n = 561 (quantitative study); n = 155 (qualitative study) | Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Embarrassment, shame, urinary tract infection symptoms |

22/22 (quantitative) 19/20 (qualitative) |

| Trant et al., 2022 | United States (not specified) | Qualitative** (semi-structured interviews) | Adolescents and young adult women | 13-24y | n = 10 | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Feeling overwhelmed and scared with menstruation, fear, worry, shame. | 15/20 |

| Sharma et al., 2022 | India (Punjab) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 15-25y | n = 2673 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts | Stress | 20/22 |

| Fernández-Martínez et al., 2022 | Spain (Andalusia region) | Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Young adult women | Mean age 22.72y (± SD = 3,46) | n = 33 | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services | Fear of medication side-effects, fear of developing dependence and tolerance of pain medication, fear of downplaying the severity of pain | 18/20 |

| Tanton et al., 2021 | Uganda (Entebbe sub-district) | Quantitative (cohort) | Adolescents and young adult women | 12-20y | n = 232 | Socioeconomic context, Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Anxiety | 16/22 |

| Lane et al., 2021 | United States (New York City) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | NB/trans, young adult, adult population | 17-32y | n = 10 | Gender norms and identity | Anxiety, unsafety | 17/20 |

| Bali et al., 2021 | India (urban slum of Madhya Pradesh) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 10-19y | n = 393 | Menstrual management | Anaemia | 18/22 |

| Gruer et al., 2021 | United States (New York City) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews) | Homeless adult women | 18-62y | n = 22 | Menstrual poverty | Shame, humiliation, experiences of sexual harassment | 18/20 |

| Wilbur et al., 2021 | Nepal (Kavrepalanchok district) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews, observation, PhotoVoice and ranking) | Adolescents and young people with disability | 15-24y | n = 20 | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual management | Feeling uncomfortable, stress, worry, humiliation, concern | 18/20 |

| Cardoso et al., 2021 | United States (not specified) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult women | 18-24y | n = 471 | Menstrual poverty | Depression | 20/22 |

| Nabwera et al., 2021 | The Gambia (rural Kiang districts) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 15-21y | n = 358 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual management | Depression, urinary tract infections, reproductive tract infections | 21/22 |

| Briggs, 2021 | United Kingdom (Stoke-on-Trent) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews, focus group discussions) | Adolescent girls | ≥ 16y | Not specified | Menstrual poverty, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Worry, anxiety, unhappiness, embarrassment | 10/20 |

| Li et al., 2020 | Australia (Melbourne) | Qualitative (in-depth semi-structured interviews) | Adolescent girls | Mean age 14.8y, range 12–18 | n = 30 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Embarrassment, distress, frustration, self-consciousness, school stress. | 19/20 |

| Kim & Choi, 2020 | South Korea (Seoul and Incheon) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult and adult women | Mean age 21y, range 17–32 | n = 383 | Menstrual management | Genitourinary infections | 22/22 |

| Hennegan & Sol, 2020 | Bangladesh (Northern Bangladesh) | Quantitative (cross-sectional data from a cluster randomised controlled trial) | Adolescent girls | Mean age 11.84y, range 10–16 | n = 1,359 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Gender norms and identity | Confidence to manage menstruation | 20/22 |

| Frank, 2020 | United States (Midwest, not specified) | Qualitative (virtual ethnographic approach) | NB/trans, young adult population | Mean age 22y, range 18–29 | n = 19 | The quality and accessibility of healthcare services | Dysphoric feelings, feeling unsafe | 16/20 |

| Ademas et al., 2020 | Ethiopia (Dessie City) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents, young adult and adult women | 16-49y | n = 602 | Menstrual management | Reproductive tract infections | 20/22 |

| Borjigen et al., 2019 | China (Changsha city) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescent girls | 11-14y | n = 1,349 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual management | Psychological stress | 15/22 |

| Gundi & Subramanyam, 2019 | India (Nashik district) | Mixed-methods (qualitative: semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions; quantitative: cross-sectional survey) | Adolescents (girls and boys) | 13-19y | n = 1,421 (quantitative study); n = 56 (qualitative study) | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Menstrual illnesses (itching, dryness, excess discharge), feeling lonely, feeling uncomfortable |

17/22 (quantitative) 18/20 (qualitative) |

| Muralidharan, 2019 | India (RG Nagar, Dharavi, central Mumbai) | Qualitative (focus group discussions, in-depth interviews) | Adolescents and young adult women | 15-24y | n = 26 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts, Menstrual knowledge, The quality and accessibility of healthcare services, Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Stress, concern, discomfort, embarrassment, security, comfort, genital discomfort, uncomfortable | 15/20 |

| Torondel et al., 2018 | India (Odisha) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult and adult women | 18-45y | n = 588 | Menstrual management | Reproductive tract infections | 21/22 |

| Lahme et al., 2018 | Zambia (Mongu District, Western Province) | Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Adolescents and young adult women | 13-20y | n = 51 | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual poverty, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Humiliation, (di)stress | 16/20 |

| Amatya et al., 2018 | Nepal (Far-Western) | Qualitative** (interviews, focus group discussion, observation) | Adolescents and young adult women | 10-19y | n = 7 | Social and community participation | Psychological problems (loneliness, lack of interest, sleep difficulties, etc.), general problems (headache, diarrhea, etc.), environmental problems (snake bite, insect bite). These are problems related to Chhaupadi | 15/22 |

| Van Leeuwen & Torondel, 2018 | Greece (Ritsona) | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions) | Young adult and adult women | 18-50y | n = 30 | Menstrual management, Menstrual poverty | Genital discomforts (itching), heavy bleeding, irregular periods, shame, concerns, anxiety, social exclusion | 16/20 |

| Girod et al., 2017 | Kenya (Nairobi) | Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Girl students (not specified) | Not specified, scholar age | 6–11 girls for each of 6 focus groups | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Gender norms and identity | Fear of urogenital tract infections, gonorrhoea, infertility, fear and anxiety of being raped and harassed, stress | 15/20 |

| Mathiyalagen et al., 2017 | India (Puducherry) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescent girls | 12-18y | n = 242 | Menstrual management | Itching and pustules over genitalia | 13/22 |

| Schmitt et al., 2017 | Myanmar (Rakhine State) and Lebanon (Tripoli, Beirut and the Bekaa Valley) | Qualitative (focus group discussions) | Displaced (in humanitarian settings) adolescents, young adult and adult women | 14-49y | n = 39 (participatory mapping); n = 117 (women aged 19-49y), n = 39 (girls aged 14-18y) | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual management | Genital discomforts, anxiety, feeling uncomfortable, feeling unsafe | 15/20 |

| Hennegan et al., 2017 | Uganda (Kamuli district) | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Adolescent girls | 12-17y | n = 27 | Menstrual knowledge, Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Genital discomfort (itching, irritation, abnormal discharge, burning sensation), fear, anxiety, stress, abdominal pain, embarrassment, feel confident | 17/20 |

| Hennegan et al., 2016 | Uganda (Kamuli district) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 10-19y | n = 435 | Menstrual management | Genital discomfort (skin irritation/rashes in pelvic area, itching or burning sensation, white or green discharge, concerns about odour), fear of soiling, menstrual pain, embarrassment, shame, insecurity, difficulties to concentrate in school | 17/22 |

| Mishra et al., 2016 | India (West Bengal) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 10-19y | n = 715 (325 rural and 390 urban areas) | Menstrual management | Gynaecological problems (burning sensation during urination, increased frequency of urination, difficulty in controlling urine, leakage of urine and itching around genitalia) | 16/22 |

| Malhotra et al., 2016 | India (Uttar Pradesh) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 10-19y | n = 1,800 | Socioeconomic context | Attitudes or feelings of impurity during menstruation | 16/22 |

| Anand et al., 2015 | India (28 states and 6 union territories, not specified) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 15-49y | n = 577,758 | Menstrual management | Reproductive tract infections, vaginal discharge | 17/22 |

| Ranabhat et al., 2015 | Nepal (Kailali and Bardiya districts) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 15-49y | n = 672 | Menstrual management, Social and community participation | Reproductive health problems (reproductive tract infections, burning micturition, abnormal discharge, itching in genitalia, pain and foul-smelling menstruation) | 20/22 |

| Das et al., 2015 | India (Odisha) | Quantitative (case-control) | Young adult and adult women | 18-45y | n = 486 (228 symptomatic cases and 258 asymptomatic controls) | Menstrual management | Inflammation, reproductive tract infections, urinary tract infections, genital discomforts (e.g. vaginal discharge). | 20/22 |

| Parker et al., 2014 | Uganda (Katakwi district) | Qualitative (interviews, focus group discussions) | Adolescents and young adult women | 9-20y | n = 765 (focus groups); n = 17 (interviews) | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma | Shame, embarrassment | 17/20 |

| Crichton et al., 2013 | Kenya (Nairobi) | Qualitative (in-depth interviews, focus group discussions) | Adolescents and adult women | 12-17y, adult women not specified | n = 87 (girls) and n = 69 (women) | Menstrual management, Menstrual poverty, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Discomfort, genital discomforts (e.g. dampness, itching, irritation, rashes), concern, anxiety, embarrassment, fear of being stigmatized, low mood, emotional distress, physical discomfort | 18/20 |

| Yamamoto et al., 2009 | Japan (Fukoka) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Young adult women | 18-25y | n = 221 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts | Stress | 19/22 |

| Chen & Chen, 2005 | Taiwan (Tainan County) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Adolescents and young adult women | 15-20y | n = 198 | Socioeconomic context | Menstrual distress | 14/22 |

| Khanna et al., 2005 | India (Rajasthan) | Mixed-methods (qualitative: focus group discussion, interviews; quantitative: survey) | Adolescents and young adult women | 13-19y | n = 730 | Menstrual management, Menstrual taboo and stigma, Social and community participation | Reproductive tract infections, embarrassment, social exclusion | 13/22 |

| Warner & Bancroft, 1990 | United Kingdom (not specified) | Quantitative (cross-sectional) | Not specified, assumed adult women | Not specified | n = 5,457 | Menstrual patterns and discomforts | Premenstrual syndrome, stress | 11/22 |

*: quality score was assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields [14]. 22 items were scored for quantitative studies and 20 for qualitative studies. **: Buitrago-García et al., 2022, Deriba et al., 2022, Trant et al., 2022 and Amatya et al., 2018 used a mixed-methods design, although the cross-sectional analyses were not included for this review. Other studies’ methods may only reflect the techniques that were analysed for this review

Fig. 2.

Categories of menstrual inequities that guided the analysis

Study quality assessment

The Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields [47] was used to assess the quality of the included studies. Quantitative and qualitative studies were assessed separately, following the guide’s checklists. Mixed-methods studies were evaluated using both quantitative and qualitative checklists, if both quantitative and qualitative data were extracted. Each item was scored as follows (yes: 2; partially: 1; no: 0; not applicable) and calculated over the maximum number of points (22 for quantitative studies and 20 for qualitative studies). Table 2 displays the final score for each article.

Data synthesis and narrative analysis

The data from the 74 included articles were synthesised and organised into the identified categories. AGE, GPD, ABH, and LMP conducted the synthesis and narrative analysis; ASH and CJA collaborated in the narrative analysis. Narrative analysis is suitable to investigate the similarities and differences of findings of different studies, as well as to explore patterns in the data [48, 49]. Data are collected and presented using a textual approach to ‘tell the story’ of the findings from included studies [50], which in our study were grouped into the previously mentioned categories. The analysis process included reviewing, integrating and summarising the data extracted from articles in each category. This process was triangulated by all researchers in regular meetings, by reading the synthesis and narrative analysis of each category, making comments and resolving any doubts or disagreements between the researchers. The final analysis was unified by AGE and GPD.

Results

Study and sample characteristics

A total of 74 articles were included (see Table 2). 51 (69%) were published between 2023 − 2020 [51–101], 16 (22%) between 2019 − 2015 [102–118], three (4%) between 2014 − 2010 [119, 120], three (4%) between 2009 − 2005 [121–123], and lastly one (1%) in 1990 [124]. 35 (47%) used qualitative methods [52–57, 59, 65, 67, 68, 71, 73–75, 78, 82, 84, 87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 96, 98–101, 104, 111, 113, 115, 116, 118–120]; 30 (41%) quantitative methods [51, 60–64, 77, 78, 81, 83, 85, 86, 89, 90, 93, 94, 97, 102, 105–110, 112, 117, 121, 122, 124], and nine (12%) were mixed-methods studies [66, 69, 70, 76, 79, 80, 103, 114, 123]. Most studies included girls and women from menarche to before menopause. Other studies focused on non-binary and trans individuals [84, 95], refugees [115, 118], people with disabilities [71, 76, 88], and people experiencing homelessness [87, 100].

Articles were classified in nine categories (one article could be classified in more than one category). Six (8%) articles were included in the “socioeconomic context” category [60, 62, 81, 83, 107, 122]; 9 (12%) on “menstrual patterns and discomforts” category [61, 62, 64, 90, 92, 102, 111, 121, 124]; 13 (18%) on ”menstrual knowledge” category [61, 66, 69, 72, 76, 80, 83, 102, 104, 111, 113, 116, 118]; eight (11%) on “the quality and accessibility of healthcare services” category [52, 55, 56, 82, 95, 98, 99, 111]; 36 (49%) on “menstrual management” category [51, 53, 57–59, 64–66, 69, 71, 75, 76, 85, 86, 88, 90, 93, 94, 97, 100–102, 104–106, 108–112, 115, 117–120, 123]; 12 (16%) on ”menstrual poverty” category [63, 74, 77, 78, 87, 89, 91, 96, 100, 113, 115, 120]; 26 (35%) on ”menstrual taboo and stigma” category [52–54, 57, 59, 65, 68–71, 73, 78–80, 83, 91, 92, 94, 100, 103, 104, 111, 116, 119, 120, 123]; four (5%) on ”gender norms and identity” category [84, 94, 95, 116]; and 15 (20%) on “social and community participation” category [54, 55, 58, 67, 69, 79, 92, 100, 104, 109, 111, 113, 114, 120, 123].

20 (27%) studies were conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa [52, 54, 58, 59, 61, 65, 66, 75, 79, 83, 85, 90, 97, 98, 104, 105, 113, 116, 119]; 18 (24%) in South Asia [53, 57, 81, 86, 88, 94, 96, 103, 106–112, 114, 117, 123]; 12 (16%) in North America (all of them in the United States (US)) [55, 56, 72, 74, 78, 80, 84, 87, 89, 95, 100, 101]; 10 (14%) in the East Asia–Pacific Region [64, 69–71, 76, 92, 93, 102, 121, 122]; eight (11%) in Europe [63, 67, 68, 77, 82, 91, 115, 124]; two (3%) in North Africa–Middle East Region [60, 62]; and two (3%) in Latin America–Caribbean Region [51, 73]. Two studies (3%) were carried out across different regions [99, 118].

More than half of the studies were conducted in the Global South (48 studies, 65%), while 26 were carried out in the Global North (35%). The affiliations of the first, corresponding and last authors were from institutions in the Global North in 44 publications (59%) [53, 55, 56, 59, 61, 63, 65, 67–69, 71, 72, 74, 76–80, 82–85, 87–95, 99–101, 104, 105, 109, 115, 116, 118, 119, 121, 122, 124], in 20 (42%) cases by institutions in the Global South [51, 57, 60, 62, 66, 73, 81, 86, 96–98, 102, 103, 106–108, 111, 113, 117, 123], and in 10 (38%) cases institutions from both The Global South and Global North [52, 54, 58, 64, 70, 75, 110, 112, 114, 120]. Of the studies conducted in the Global South, 27 (56%) were affiliated with at least one institution in the Global North [52–54, 58, 59, 61, 65, 69, 70, 75, 76, 79, 83, 85, 88, 90, 94, 104, 105, 109, 110, 112, 114, 116, 118, 120], whereas none of the studies conducted in the Global North were affiliated with an institution in the Global South. The three countries that were mostly affiliated with the studies were the US (21 studies, 28%) [53–56, 59, 61, 65, 69, 72, 78, 80, 84, 87, 89, 94, 95, 100, 101, 114, 116], England (17 studies, 23%) [52, 68, 75, 76, 79, 83, 88, 90, 91, 104, 105, 110, 112, 115, 118–120] and India (12 studies, 16%) [81, 86, 96, 103, 106–108, 110–112, 117, 123]. Of the funding institutions, 36 (49%) were located in the Global North [52–56, 58, 59, 61, 65, 68–70, 72, 74, 76, 78–80, 83–85, 87–90, 92, 94, 104, 105, 107, 110, 112, 116, 118, 120, 121], eight (11%) in the Global South [51, 66, 73, 81, 97, 98, 102, 106], and only one (1%) study was funded by institutions in both the Global North and Global South [109]. 15 (20%) publications declared not having received any financial support [57, 60, 63, 64, 67, 77, 86, 91, 96, 99, 103, 111, 113, 114, 117] and in 14 (20%) cases it was not possible to determine whether there had been any funding for the study [62, 71, 75, 82, 93, 95, 100, 101, 108, 115, 119, 122–124]. The funding institutions were mainly placed in the US (16 studies, 21%) [53–55, 58, 59, 61, 69, 72, 78, 85, 87–89, 94, 116], England (12 studies, 16%) [52, 68, 79, 83, 84, 90, 104, 105, 110, 112, 118, 120] and Australia (4 studies, 5%) [70, 76, 85, 92]. 17 studies (23%) were financed by public institutions, organizations or foundations [51, 55, 65, 66, 68, 76, 79, 81, 90, 92, 97, 98, 102, 104–106, 120], 10 (14%) by private ones [56, 58, 61, 69, 72, 80, 84, 87, 88, 107], while four studies (5%) received funding from both private and public institutions [74, 78, 85, 116]. 24 studies (50%) conducted in the Global South were funded by institutions in the Global North [52–54, 58, 59, 61, 65, 69, 70, 76, 79, 83, 85, 88, 90, 94, 104, 105, 109, 110, 112, 116, 118, 120], while none of the studies in the Global North were funded by institutions in the Global South. See Table 3 for further details.

Table 3.

Main characteristics of authorship, affiliations and funding of included studies (n = 74)

| 1st author, year of publication | Data collection country | Affiliation (1st author) | Affiliation (Corresponding author) | Affiliation (last author) | Affiliation Country | Funding | Funding country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camas-Castillo et al., 2023 | Brazil (Campinas, São Paulo) | Public university | Public university | Public university | Brazil | A public institution and a public foundation | Brazil |

| Ssemata et al., 2023 | Uganda | Public university research institute. | Public university research institute. | Public university | Uganda & Engand | Three public institutions and an independent foundation | United Kingdom |

| Marí-Klose et al., 2023 | Spain (Barcelona) | Public university | Public university | Public university | Spain | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Schmitt et al., 2023 | United States | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Two private foundations and a public institution | United States |

| Borg et al., 2023 | Uganda (Mukono District) | Private non-university research institute | Private non-university research institute | Private non-university research institute | Australia |

Private foundation. One of the authors is furthermore financed by a public institution and a private foundation |

United states & Australia |

| Babbar et al., 2023 | India | Private university | Private university | Private university | India | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Getahun et al., 2023 | Ethiopia | Public university | Public university | Public university | Ethiopia | Public university | Ethiopia |

| Mohammed et al., 2023 | United States, United Kingdom | Public university | Public university | Public University | Canada | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Boden et al., 2023 | United States | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | This information could not be found | - |

| ElBanna et al., 2023 | United States | Non-profit healthcare organisation | Non-profit healthcare organisation | Private university | United States | This information could not be found | - |

| Choudhary et al., 2023 | India (New Delhi) | Public university | Public university | Public university | United States | Independent federal agency | United States |

| Betsu et al., 2023 | Ethiopia (rural Tigray) | Public university | Public university | Private university | Ethiopia & United States | Not-for-profit organization | United States |

| Varshney et al., 2023 | Not specified | Private university | Private university | Public university | United States | Public university | United States |

| Chan et al., 2023 | United States | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Funded in part by the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast (RISE) through support from an anonymous foundation | United States |

| Sadique et al., 2023 | Pakistan | Public university | Public university | Unspecified | Pakistan | The author(s) reported no funding. | - |

| Hennegan et al., 2022 | Uganda | Private non-university research institute | Private non-university research institute | Public university | Australia & Uganda | Two private foundations | United States & Sweden |

| Winter et al., 2022 | Kenya (Mathare informal settlement, Nairobi) | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | The first author is funded by a non-profit organization | United States |

| Adib-Rad et al., 2022 | Iran | Public university | Public university | Public university | Iran | The author(s) reported no funding. | - |

| Cherenack & Sikkema 2022 | Tanzania | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Private university | United States |

| Alshdaifat et al., 2022 | Jordan | Public university | Public university | Private university | Jordan | This information could not be found | - |

| Mariappen et al., 2022 | Malaysia | Public university | Public university | Public university affiliated hopistal | Malaysia & Australia | The author(s) reported no funding. | - |

| Buitrago-García et al., 2022 | Burkina Faso | Public university hospital | Public university hospital | Private university | Germany & United States | Public institution | Germany |

| Deriba et al., 2022 | Ethiopia | Public university | Public university | Public university | Ethiopia | Public university | Ethiopia |

| Ní Chéileachair et al., 2022 | Ireland | Public university | Public university | Public university | Ireland | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Boyers et al., 2022 | United Kingdom (England) | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Public institution | United Kingdom |

| Daniels et al., 2022 | Cambodia (2 rural provinces) | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Private Christian organisation | United States |

| Swe et al., 2022 | Myanmar (Magway Region) | Private non-university research institute | Private non-university research institute | Private non-university research institute | Myanmar & Australia | Two public institutions and two non-governmental organizations | Australia |

| McGregor & Unsworth, 2022 | Australia | Non-profit organisation | Public university | Public university | Australia | This information could not be found | - |

| Schmitt et al., 2022 | United States | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Two private foundations | United States |

| Ames & Yon, 2022 | Peru | Private university | Private university | Private university | Peru | Inter-governmental organisation |

Peru (UNICEF, Peru office) |

| Asumah et al., 2022 | Ghana | Public university | Public university | Private university hospital | Ghana & United Kingdom | This information could not be found | - |

| Wilbur et al., 2022 | Vanuatu | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Public institution | Australia |

| Gouvernet et al., 2022 | France | Public university | Public university | Public university | France | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Sommer et al., 2022 | United States | Private university | Private university | Public university | United States | Private foundation, public institution and a public university | United States |

| Shah et al., 2022 | Gambia | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Public institution | United Kingdom |

| Trant et al., 2022 | United States | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Private company | Italy |

| Sharma et al., 2022 | India (Punjab) | Public university | Public university | Public university | India | Public institution | India |

| Fernández-Martínez et al., 2022 | Spain | Public university | Public university | Public university | Spain | This information could not be found | - |

| Tanton et al., 2021 | Uganda | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Three public institutions and an independent charitable organization | United Kingdom |

| Lane et al., 2021 | United States | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Private foundation | United Kingdom |

| Bali et al., 2021 | India | Public university | Public university | Public university | India | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Gruer et al., 2021 | United States (New York City) | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | Two private foundations | United States |

| Wilbur et al., 2021 | Nepal | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Private foundation | United States |

| Cardoso et al., 2021 | United States | Private university | Public university | Public university | United States | Non-profit organization | United States |

| Nabwera et al., 2021 | Gambia | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Public institution | United Kingdom |

| Briggs, 2021 | United Kingdom | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Li et al., 2020 | Australia | Public university affiliated hospital | Public university affiliated hospital | Public university affiliated hospital | Australia | Two authors are funded by a public university, one author is funded by a public institution | Australia |

| Kim & Choi, 2020 | South Korea | Public university | Private university | Private university | South Korea | This information could not be found | - |

| Hennegan & Sol, 2020 | Bangladesh | Private university | Private university | Public university | United States & Netherlands | One public institution and a non-governmental organization. One author is furthermore funded by two private foundations | Sweden, United States, The Netherlands |

| Frank, 2020 | United States | Public university | Public university | Public university | United States | This information could not be found | - |

| Ademas et al., 2020 | Ethiopia (Dessie City) | Public university | Public university | Public university | Ethiopia | Public university | Ethiopoia |

| Borjigen et al., 2019 | China (Changsha city) | Public university | Public university hospital | Public university hospital | China | Two public institutions and a public university | China |

| Gundi & Subramanyam, 2019 | India (Nashik district) | Public university | Public university | Public university | India | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Muralidharan et al., 2019 | India (RG Nagar, Dharavi, central Mumbai) | Non-governmental organization | Non-governmental organization | Non-governmental organization | India | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Torondel et al., 2018 | India (Odisha) | Public university | Private university hospital | Private university hospital | India & England | A public institution and an inter-governmental organization | United Kingdom & Switzerland |

| Lahme et al., 2018 | Zambia (Mongu District, Western Province) | Unspecified | Unspecified | Public university | Zambia & South Africa | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Amatya et al., 2018 | Nepal (Far-Western) | Public university | Public university | Public university | Nepal & United States | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Van Leeuwen & Torondel, 2018 | Greece (Ritsona) | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | This information could not be found | - |

| Girod et al., 2017 | Kenya (Nairobi) | Private university | Private university | Private university | United States | A private university, a private foundation and a public institution | United States |

| Mathiyalagen et al., 2017 | India | Public university affiliated research institute | Public university affiliated research institute | Public university affiliated research institute | India | The author(s) reported no funding | - |

| Schmitt et al., 2017 | Myanmar (Rakhine State) and Lebanon (Tripoli, Beirut and the Bekaa Valley) | Private university | Private university | Private university | England | A non-profit organization, one independent charitable organization and a public institution | United Kingdom |

| Hennegan et al., 2017 | Uganda | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Public institution | United Kingdom |

| Hennegan et al., 2016 | Uganda (Kamuli discrict) | Public university | Public university | Public university | England | Public institution | United Kingdom |

| Mishra et al., 2016 | India (West Bengal) | Public university | Public university | Public university | India | Public institution | India |

| Malhotra et al., 2016 | India (Uttar Pradesh) | Inter-governmental organisation | Inter-governmental organisation | Inter-governmental organisation | India | Private company | - |

| Anand et al., 2015 | India | Public university | Public university | Public university | India | This information could not be found | - |

| Ranabhat et al., 2015 | Nepal | Private university | Private university | Public organisation | South Korea | A non-governmental organization and a public institution | Nepal & South Korea |

| Das et al., 2015 | India (Odisha) | Private university | Public university | Public university | India & England | A public institution and an inter-governmental organization | United Kingdom |

| Parker et al., 2014 | Uganda | Public university | Public university | Non-governmental organisation | England | This information could not be found | - |

| Crichton et al., 2013 | Kenya (Nairobi) | Public university | Public university | Non-governmental organisation | England & Kenya | Public institution | United Kingdom |

| Yamamoto et al., 2009 | Japan | Public university | Public university | Private university | Japan | Independent institution | Japan |

| Chen & Chen, 2005 | Taiwan | Private university | Private university | Private university | Taiwan | This information could not be found | - |

| Khanna et al., 2005 | India (Rajasthan) | Public university | Public university | Public university | India | This information could not be found | - |

| Warner & Bancroft, 1990 | United Kingdom | Public university | Public university | Public university | Scotland | This information could not be found | - |

Moreover, quotes illustrating some qualitative findings are presented in Table 4. The definition of terms and concepts used in included articles are available in Table 5. The relevant terms and concepts are indicated in italics throughout the Results section.

Table 4.

Quotes for qualitative studies classified by categories

| Categories | References | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Menstrual patterns and discomforts | Li et al., 2020 | “I have trouble sleeping when I’m on my period, ‘cause that’s just constantly there and constantly waking me up, so I have to go off to the toilet again” |

| Muralidharan, 2019 | “I think everyone is worried about their periods. But I think that those who do not get their periods at all are the most stressed… People are quick to misinterpret why a girl is not menstruating… they think she is pregnant” | |

| Menstrual knowledge | Deriba et al., 2022 | “I will never forget what I experienced during my first menses; while sitting and learning in class, I noticed that blood flowed from my organ. I was terrified, confused, and fell from the bench to the ground, where my friends carried me out of the class while other students teased me and older girls told me that it was normal even if I did not believe them” |

| Trant et al., 2022 |

“I was in the bathroom doing my business and I saw blood and I was scared.” She said, “I was crying because I didn’t know if I was dying or not” “I guess I was just nervous because I didn’t know like what it was going to do like if it was going to like bleed through my pants or anything, and I was asking my friends about it, and they weren’t that experienced either, so they were kind of telling me false information making me more scared, so” |

|

| Lahme et al., 2018 | ”I was scared and terrified as I did not know what was happening to me” | |

| Schmitt et al., 2022 | “I told my auntie that there was something wrong, I explained…my severe stomach-ache and the blood on the sheets and she asked me the question: ‘Didn’t nobody ever talk to you about your period?’ And my response was ‘no, I didn’t know what that was’… I was only in third grade at the time…” | |

| The quality and the accessibility to healthcare services | Ssemata et al., 2023 | “The nurse is always rude and tough on the girls. Even when you experience severe cramps and need medical attention, the nurse will always say you are pretending and in the end, you struggle with your pain and are not helped” |

| Getahun et al., 2023 | “When I wanted to go and consult my friends, they always told me that if I use treatment, I might become addicted, so I gave up going. I mean, I live in a rural area where there is no medical treatment, so I did not go” | |

| Mohammed et al., 2023 | “I went to the doctor and I said […] ‘I’m in agony’ so the doctors recommended that I go onto birth control […], so that I wasn’t going through agony all the time, but they still just condensed that down to being just heavy periods so it was never like a label’. They just sort of shoved me off, so I didn’t come back to the doctors” | |

| Chan et al., 2023 | “It’s a woman’s issue which already gets tossed aside and it’s a mental health issue which also gets tossed aside. It’s just- it’s a double whammy of bad luck and they just don’t want to take it seriously for whatever reason.… They just wanna think it’s either brain issue or it’s a reproductive system issue and they can’t seem to connect that it’s- they’re both. They’re tied into each other. And that the body is making the brain feel this way.” | |

| Fernández-Martínez et al., 2021 | “I think they won’t consider it important, if they ask me about my cycle, my pain, if I’m not in extreme pain they’ll ask me why I want an analysis or cytology test” | |

| Frank, 2020 | “You know even when you go to the doctors now it’s, like, the first thing they ask you is when was the first day of your last period always. And I’m always like, “Why do you need to know?” [..] Like, one time I didn’t take a shit for like two weeks I was just severely constipated and I went to the doctors and they were like, “Oh you’re PMS-ing,” and I’m like, “Okay, like, that doesn’t make me feel better. Can you just like give me something to, like, get this waste out of my body?” | |

| Muralidharan, 2019 | “I like lady doctors. I can talk to them openly about my body and not be embarrassed. I can talk about my chest area or my genitals and not be embarrassed. They can understand what the problem is because they are women, too.” | |

| Menstrual management – Use of menstrual products for menstrual management | Sadique et al., 2023 | “I used homemade pads but because of the flood all our houses got destroyed, and we didn’t have anything left. We were living beside the road, all clothes were soaked and floated away. I was forced to use leaves, which was very uncomfortable, and I even got rashes and itching on my vaginal and anal area. It’s after that I had a vaginal infection” |

| Daniels et al., 2022 | “The pads turn over for [the] sticker isn’t good. The pads are thin and short, [and there is] too much blood. Accidents happen especially when sleeping and playing” | |

| Wilbur et al., 2021 | “When I sit in the wheelchair the pads may fold or something like that might happen which makes me feel uneasy […]. It becomes very uncomfortable to sit. Unlike my sisters who keep moving around, I have to sit in a place continuously. I get angry then and it gets difficult” | |

| Van Leeuwen & Torondel, 2018 | “When I use cloth, when you walk you have a problem in the groin and it is very moist and you have problems and itching” | |

| Parker et al., 2014 | “We are embarrassed to transport rags to and from school. We have no bags to put them in” | |

| Menstrual management – Menstrual care and management practices | Asumah et al., 2022 | “When it enters the vagina, you would feel some unusual pain. I just use water to wash my vagina” |

| Menstrual management – Menstrual care and management spaces | ElBanna et al., 2023 |

“I was in an alley. I was by a dumpster.… I had soiled my clothes, and uh I was changing, and I see this person walking down… I was trying to hurry up before they got close to me, and it was a guy, and he kept trying to come close and thank God I did have a knife. You know, and once he saw that knife, he kinda went about his business but it made me think if I didn’t have that knife, what would a happened, you know. I remember him calling me, ‘Oh you bloody mess’” “I feel miserable. I don’t even feel like a person anymore, I just feel like I’m existing and I just keep trying to improve my life and trying to find a job and trying to find this and trying to find that and it’s just when you get your period, it’s hot outside and you’re dirty and you can’t take care of yourself, it’s dehumanizing you know” |

| Choudhary et al., 2023 |

“I feel bad. We have to think and plan even for bathing and drinking…It’s not a good feeling. I feel bad, at least during periods. In such a water situation, you can’t work freely” “When water is not there, dishes are not washed and when someone visits and asks me why I am not cleaning them, I feel ashamed. How will I clean the dishes when water is not there!” |

|

| Sadique et al., 2023 | “I use old clothes on my period. I have no access to a washroom; therefore I use flood water to clean the vagina and wash the menstrual clothes. I don’t have the place to make it dry due to rainy weather. I have to use the wet one again and again. I experience urinary tract infection and itching” | |

| Winter et al., 2022 | “There are gaps in the door. Sometimes you will find I am standing here and somebody is in the toilet. You feel like he or she is seeing what I am doing inside there” | |

| Buitrago-García et al., 2022 |

“You already feel disgusting on your period and you come into a toilet that is again dirty, you feel even more disgusted” “I’m on my period at school, I’m not safe to change, there is no kettle to put water in (…) and it is often dirty” “It’s a little hard to manage (your period) in the bathroom, you’re not safe there because someone can open the door at any time” |

|

| Deriba et al., 2022 | “Because the school property and the latrine area are unclean and there is no water, the toilet is always dirty and unpleasant, making it unsafe to use or change modes” | |

| Daniels et al., 2022 | “At school, I feel shy, lack clean water, toilet, soap, and sanitary pad during menstruation” | |

| Van Leeuwen & Torondel, 2018 |

“In the tent, if it’s very cold and you have your period, you’re going to feel bad and it’s not comfortable. If it’s hot, you are not going to feel comfortable” “There was a girl of 16 years who lived behind my tent. She was going to the toilet to change her pad. Just when she arrived, there were a lot of young men and she dropped her pad in front of them. She came back crying. I asked her what happened, and she told me the story. For many days, she did not leave her tent” |

|

| Crichton et al., 2013 |

“If you go to the toilet and see it on the floor or the toilet basin, it is not good. It messes your day when you see it. It is a private thing and not for all to see” “It is a problem because these houses are single rooms and the whole family is there including the father. It becomes hard for them to go and change [sanitary products] and then they also don’t have toilet facilities…Maybe they will wait until night when their family are asleep]” |

|

| Menstrual poverty | Schmitt et al., 2023 | “Sometimes I would have to buy the way cheaper brand of pads that were no good at all and didn’t really work for me and I was always messing up my clothes. And I didn’t feel good at all, and it was uncomfortable…” |

| Gruer et al., 2021 | “The humiliation is that you have to keep going back to them and asking them, and when you’re asking for, because they have police and security, so it’s not private. So you’re asking for it in front of NYPD and DHS security, and most of those are male staff” | |

| Briggs, 2021 |

“They’re asking friends to bring them in for them. If you ask the girls, that’s what they’ll say, that they do bring sanitary products in for their friends as well, which is also very demeaning isn’t it? Having to ask your friend to bring in sanitary products for you?” “Yeah, it does affect you mentally. I think when it’s affecting your everyday life and you can’t do what you want, it does bring you down” |

|

| Menstrual taboo and stigma | Ssemata et al., 2023 |