Abstract

Fenton reactions are believed to play important roles in wood degradation by brown rot fungi. In this context, the effect of tropolone (2-hydroxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone), a metal chelator, on wood degradation by Poria placenta was investigated. Tropolone (50 μM) strongly inhibits fungal growth on malt agar, but this inhibition could be relieved by adding iron salts. With an experimental system containing two separate parts, one supplemented with tropolone (100 μM) and the other not, it was shown that the fungus is able to reallocate essential minerals from the area where they are available and also to grow in these conditions on malt-agar in the presence of tropolone. Nevertheless, even in the presence of an external source of metals, P. placenta is not able to attack pine blocks impregnated with tropolone (5 mM). This wood degradation inhibition is related to the presence of the tropolone hydroxyl group, as shown by the use of analogs (cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone and 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone). Furthermore, tropolone possesses both weak antioxidative and weak radical-scavenging properties and a strong affinity for ferric ion and is able to inhibit ferric iron reduction by catecholates, lowering the redox potential of the iron couple. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that tropolone inhibits wood degradation by P. placenta by chelating iron present in wood, thus avoiding initiation of the Fenton reaction. This study demonstrates that iron chelators such as tropolone could be also involved in novel and more environmentally benign preservative systems.

The use of traditional wood preservative chemicals is increasingly coming under scrutiny, as questions concerning the environmental acceptability of biocides in general become more prominent both socially and politically (18). There is a strong general desire to develop wood protection systems with improved environmental acceptability as alternatives to traditional methods (28, 29).

Brown rot caused by fungi is one of the most common and destructive types of decay in wooden structures in the northern hemisphere. These basidiomycetes are unusual in that they rapidly depolymerize cellulose in wood without removing the surrounding lignin that normally prevents microbial attack (10).

Mechanisms of brown rot action have been studied extensively, particularly with Gloeophyllum trabeum. Recent data suggest that this fungus uses an extracellular Fenton system (Fe2+ H2O2) to generate hydroxyl radicals, powerful oxidants that degrade wood (16, 20, 25, 32). Biochelators produced by wood-degrading fungi might function to mediate this reaction, reducing Fe(III) to Fe(II), the iron being found essentially in the ferric state in an aerobic environment (12, 25). Indeed, these chelators, like catechols, not only sequester metals, but are also known to possess reductive capabilities to reduce transition metal species. This capability would be important for the production of the reduced iron required to generate hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction.

Tropolone (2-hydroxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone) is an analog of hinokitiol, a naturally occurring terpene responsible for resistance to fungal decay and insect attack on heartwood of several cupressaceous trees (1, 19, 24). The metal-chelating properties of tropolone have been used in several experiments to create metal-limiting conditions (9, 27) or as an inhibitor of copper enzymes (8, 13).

In a previous study, we have shown that tropolone strongly inhibits the growth of several wood rot fungi on malt-agar, the antifungal activity of tropolone being quite similar to that of commercially available fungicides in current use as wood preservatives (4). In order to understand the effects of tropolone on P. placenta wood degradation, we tested in this study whether tropolone produced its effects by acting as a chelator, an antioxidant, a scavenger of chemical radicals, or some combination of these. Furthermore, we tested whether the observed tropolone inhibition of wood decay was due to an iron starvation of the fungus or to inhibition of a specific extracellular reaction involved in wood degradation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Commercially available products, including 4-tert-butylcatechol, 2,3-dihydrobenzoic acid, and tropolone, were purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.) or Lancaster (Morecambe, England).

Synthesis of tropolone and 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone.

Tropolone and 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone were synthesized as previously described (4, 26).

Organism.

The brown rot fungus used in this study was P. placenta strain FPRL 280 (4). Fungal stock cultures were maintained on malt-agar slants (Difco), which were kept at 4°C before use.

Growth inhibition.

Mycelia were grown in 10-cm petri dishes filled with 20 ml of malt-agar medium containing different concentrations of growth inhibitors, which were added aseptically from a filter-sterilized 1 M ethanolic solution. Plates were inoculated by placing a 10-mm-diameter plug cut from the edge of a starting colony growing on malt-agar medium. The cultures (two replicates for each experiment) were incubated for 15 days in a growth chamber at 25°C. Growth was evaluated every 2 or 3 days by measuring two perpendicular diameters of the colony and expressed as a percentage of the space available for growth, i.e., the diameter of the dish.

In some experiments, 25 ml of agar medium was supplemented with various concentrations of FeCl3 or FeSO4 (0 to 100 μM). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Growth on separate areas.

Petri dishes were filled with 20 ml of malt-agar medium. One half of the medium was aseptically removed after solidification, and the empty space was filled with malt-agar medium supplemented with 100 μM tropolone. After solidification, a 0.5-cm-wide borderline band of the medium was aseptically removed, leading to two separate areas, one with and one without tropolone. Plates were inoculated by placing a 10-mm-diameter plug, cut from the edge of a starting colony growing on malt-agar medium, in the center of the agar devoid of tropolone. The cultures (two replicates for each experiment) were incubated for 50 days at 25°C. Growth was evaluated every 2 or 3 days by measuring the colonized surface of the tropolone-treated zone and expressed as a percentage of the space available for growth.

Chelator impregnation and wood block test.

Weighed (mi), oven-dried pine blocks (Pinus sylvestris) (15 by 20 by 50 mm, radial by tangential by longitudinal) were used for biological trials (5, 6). Four dried blocks were placed in a beaker inside a desiccator equipped with a two-way valve and subjected to a 4-mbar vacuum for 1 h. Blocks were then impregnated by suction and covered with 5 mM aqueous solutions of each compound dissolved in the minimal amount of ethanol, and the pressure was returned to the atmospheric level. After 3 h of soaking, the blocks were placed under air and dried at 80°C for 2 days. Treated (two replicates) and untreated (two replicates) blocks were placed in petri dishes on sterile culture medium (15 g of malt, 15 g of gelose, 1 liter of distilled water) previously exposed to P. placenta for 2 weeks. The incubation was carried out for 10 weeks at 25°C under 70% relative humidity. The blocks were then extricated from the mycelium, dried at 80°C for 2 days, and weighed (mf). The fungicidal efficiency of the treatment was estimated according to the weight loss (WL), calculated according to the following formula:

|

The tropolone concentration in pine wood was estimated by the difference between the tropolone concentration in the impregnation solution before and after the treatment. gas chromatography analysis were performed on a Fisons GC-8000 series instrument with a DB1 capillary column (J & W Scientific; length, 10 m; internal diameter, 0.32 mm; filter, 0.25 μm). The temperature program started at 50°C for 1 min, raised at 25°C/min to 150°C, and held at 150°C for 1 min. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas. The tropolone concentration was determined with phenol as the internal standard. The retention time was 2.01 and 3.22 min for phenol and tropolone, respectively.

Oxidation experiment.

The inhibition of oxygen uptake with methyl linoleate (LH) as the substrate was used (3, 10). L· free radicals are generated by the initiator AIBN (2,2′-azobis[2-methylpropionitrile]), and oxidation of methyl linoleate is a chain reaction propagated by the processes:

|

|

In the presence of an inhibitor having a labile hydrogen and called AH, chain carriers easily abstract an H atom from AH (called a chain-breaking antioxidant), giving an unreactive free radical A·:

|

and so inhibiting chain propagation. Oxidation was monitored by measuring the oxygen pressure for the reaction.

The solvent used throughout was 1-butanol. Oxidation of methyl linoleate (0.4 M) was performed in a closed borosilicate glass apparatus with 9 × 10−3 M AIBN as an initiator (11). The double-shell reactor was thermostated at 60°C by an external heating bath. Oxygen (154 Torr) was bubbled by a gas-tight oscillating pump with a magnetically coupled motor. A small condensor at 5°C was inserted in the gas circulation just after the reactor to ensure condensation of the solvent. The volumes of the liquid and gas phases were 4 ml and 100 ml, respectively. Oxygen uptake was monitored continuously with a pressure transducer (Viatron model 104). Tropolone or reference antioxidant concentrations were generally 5 × 10−4 M.

Radical-scavenging activity.

Methanolic solutions of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl free radical and tropolone or reference compounds were rapidly mixed in the rapid kinetic accessory SFA-11 (Hi-Tech Scientific, Salisbury, United Kingdom), so that their concentration was 100 μM (31). Absorbance was measured at 517 nm (a wavelength at which only 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl absorbs) for 30 min with a CaryWin UV spectrophotometer (Varian, Zug, Switzerland).

Reduction of Fe(III) by 4-tert-butylcatechol.

Fe(II) production was determined by the ferrozine assay (30). The test was performed in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.8) containing ferrozine (10 mM), FeCl3 (0.2 mM), and various concentrations of tropolone from 0 to 1.2 mM. The mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and the reaction was initiated by addition of 4-tert-butylcatechol (1 mM). Fe(II) complex formation was measured by spectrophotometry at 562 nm after 15 min with a CaryWin UV spectrophotometer (Varian, Zug, Switzerland). The blank was the reaction mixture without 4-tert-butylcatechol. The same experimental procedure was also performed with 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid.

RESULTS

Effects of iron solution on tropolone growth inhibition.

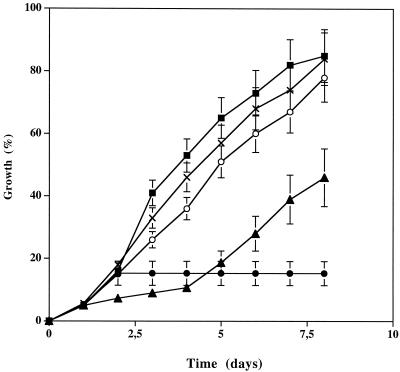

Growth of P. placenta was monitored on malt-agar medium containing tropolone (100 μM) and various FeCl3 concentrations (25, 50, and 100 μM) (Fig. 1). At these concentrations, ferric ions have no effect on fungal growth (data not shown). As we reported previously (4), tropolone at this concentration strongly inhibited P. placenta growth. Tropolone growth inhibition was partially removed with 25 and 50 μM FeCl3 and completely suppressed with 100 μM, suggesting that tropolone strongly reduces the availability of iron (or other metals) present initially as traces in the medium, leading to inhibition of fungal growth. The same result was obtained when Fe(SO4)3 was added at the same concentrations.

FIG. 1.

Effects of ferric ion on P. placenta growth inhibition by tropolone. Growth of P. placenta was followed for 8 days in malt-agar plates supplemented with • 100 μM tropolone; 100 μM tropolone and ▴ 25 μM FeCl3; ○ 50 μM FeCl3; and ▪ 100 μM FeCl3; X, control without any addition. Each point is the mean ± t standard deviation (SD), indicated by an error bar, for four different cultures.

Metal reallocation.

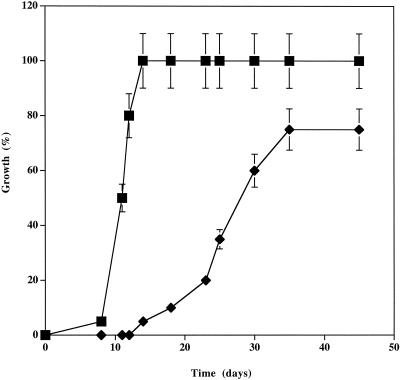

The inoculum was placed in the tropolone-free area, and the colonization area was measured as a function of time in the second area supplemented or not with 100 μM tropolone (Fig. 2). P. placenta was able to colonize malt-agar medium supplemented with 100 μM tropolone when the inoculation was performed on a separate tropolone-free area. Nevertheless, the growth rate observed (0.8 cm2 per day) and the colonized area were clearly reduced when the inhibitor was present, in comparison with control experiments performed without added tropolone (4.5 cm2 per day). Despite these differences, the results suggest that the fungus is able to overcome the inhibitory effects of tropolone under the conditions tested.

FIG. 2.

Effects of external metal sources on P. placenta growth inhibition by tropolone. Petri dishes were filled with malt-agar medium in order to obtain two separate areas. The first part did not contain tropolone and was inoculated. The second part of the petri dish was supplemented ♦ or not ▪ with 50 μM tropolone. The fungal colonization of the second part was monitored for 45 days. Each point is the mean ± standard deviation for six different cultures.

With the same experimental system (i.e., two split areas in a petri dish, one corresponding to the inoculum, the other containing the wood block), pine blocks treated or not with 5 mM tropolone solution were subjected to P. placenta attack. The iron concentration of the pine wood used in these experiments was of 0.31 μmol/g, measured by atomic absorption spectrometry. The tropolone concentration in pine wood after treatment was estimated at about 6 μmol/g. This treatment strongly inhibited growth of P. placenta on pine blocks because no colonization was observed in the 5 mM treatment and no weight loss was detected. At the same time, about 25% of mass loss was measured in the untreated pine blocks, which were wholly colonized.

Importance of tropolone hydroxyl group in wood protection.

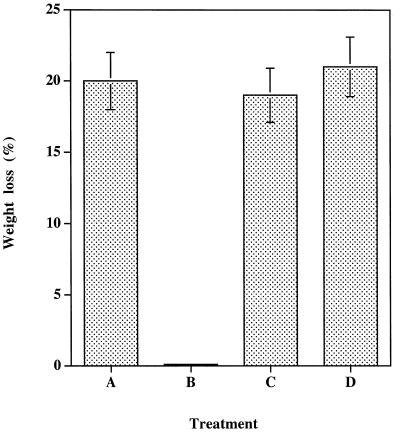

P. placenta attack was monitored on pine sapwood blocks impregnated with either 5 mM tropolone (2-hydroxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone), cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone (tropone) (5 mM), or 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone (5 mM). About 20% mass loss was measured in untreated pine blocks or cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone- (5 mM) and 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone- (5 mM) impregnated pine blocks incubated in the presence of the fungus for 10 weeks (Fig. 3). However, treatment with 5 mM tropolone completely inhibited the growth of P. placenta, as demonstrated by the low weight loss observed. The 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone and cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone solutions also had no effect at this concentration. These results confirm the importance of the hydroxyl group of tropolone, since when it is replaced by a methoxy group, the derivative is inactive as a wood preservative.

FIG. 3.

Effects of tropolone and tropolone analogs on P. placenta wood degradation. Pine sapwood blocks were subjected to P. placenta degradation after different treatments: A, none; B, impregnated with 5 mM tropolone; C, impregnated with 5 mM cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone; or D, impregnated with 5 mM 2-methoxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trienone. Each point is the mean ± standard deviation for four different cultures.

Tropolone as antioxidant.

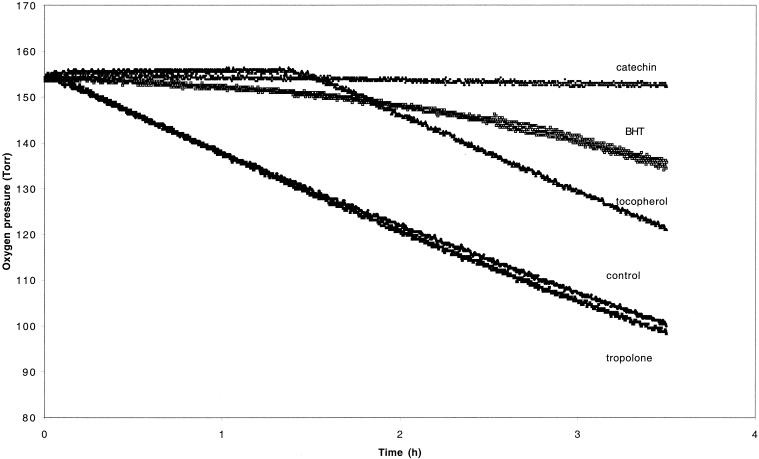

Since wood degradation by brown rot fungi is believed to be associated with the production of free radicals, the antioxidant activity of tropolone was tested and compared to that of compounds known for their antioxidant properties, i.e., α-tocopherol, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol, and (+)-catechin. As shown in Fig. 4, oxidation of methyl linoleate was strongly inhibited by the reference compounds at a concentration of 5 × 10−4 M, but was only weakly inhibited by tropolone at the same concentration. Thus, the wood protection induced by tropolone cannot be explained by its very weak antioxidant properties.

FIG. 4.

Antioxidant properties of tropolone. Oxidation of methyl linoleate (0.4 M) induced by AIBN (9 × 10−3 M) was followed by measuring oxygen pressure in the presence of either 5 mM tropolone, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT), (+)-catechin, α-tocopherol, or no addition at 60°C. The reaction was inhibited in the presence of antioxidant molecules, e.g., 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol, (+)-catechin, and α-tocopherol used as positive controls.

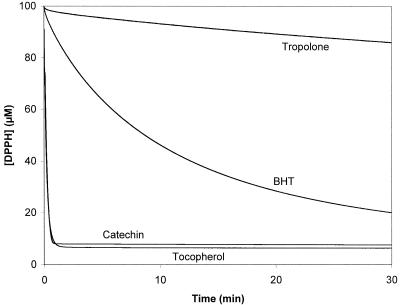

On the other hand, we tested the antiradical activity of tropolone by the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl method. As shown in Fig. 5, only 14% of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl reacted with tropolone after 30 min, whereas more than 90% reacted with tocopherol and catechin and 80% with 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol. These results demonstrated that tropolone is a poor radical scavenger. They were in good agreement with data previously reported which suggest that the scavenging activity of β-thujaplicin against active oxygen species was due to suppression of hydroxy radical formation, such as the Fenton reaction, by the formation of β-thujaplicin-Fe complex (2, 33).

FIG. 5.

Antiradical properties of tropolone. The consumption of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (100 μM) for its reaction with either tropolone, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT), (+)-catechin, or α-tocopherol at 100 μM, the latter three being used as positive controls.

Tropolone as iron chelator.

Since iron is believed to play an essential role in wood degradation by brown rot fungi (14), we investigated iron-tropolone interactions. A mixture of ferric ion (0.7 mM) and tropolone (21 mM) led instantaneously to the formation of an orange-red precipitate. A precipitate was also obtained when tropolone (21 mM) was mixed with ferrous ion (0.7 mM). Thermogravimetric analysis indicated that the precipitates obtained involve three equivalents of tropolone for one equivalent of ferric ion [Fe(trop)3] and two equivalents of tropolone for one equivalent of ferrous ion [Fe(trop)2] (data not shown). Furthermore, the solubility constants (pKs) of Fe(trop)3 and Fe(trop)2 were estimated by pH metric methods to be 30 and 13.5, respectively (C. Rapin, unpublished results).

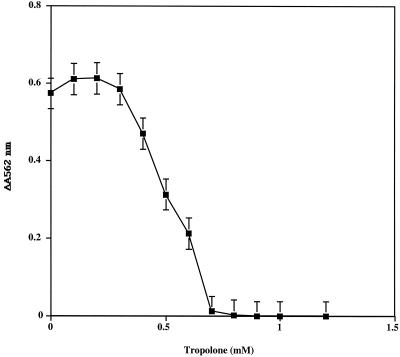

Inhibition of Fe(III) reduction.

Since catecholate siderophores are involved in the first steps of wood degradation by brown rot fungi (16), we investigated the effects of tropolone on Fe(III) reduction by catecholate. Figure 6 shows that reduction of Fe(III) occurred in the presence of 4-tert-butylcatechol. This reduction has also been observed in the presence of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (data not shown) (25). The production of an Fe(II)-ferrozine complex was strongly inhibited in the presence of tropolone, since no complex formation was observed when 0.7 mM tropolone was added to the system. When the accumulation of Fe(II)-ferrozine complex was followed with 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid, the same pattern of inhibition by tropolone was observed (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Reduction of Fe(III) by 4-tert-butylcatechol in the presence of tropolone. Fe(III) (0.2 mM) reduction by 4-tert-butylcatechol (1 mM) was measured by monitoring the absorbance of Fe(II)-ferrozine complex at 562 nm. Each point is the mean ± standard deviation for four different experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that tropolone inhibits the growth of P. placenta on malt-agar, but this inhibition could be relieved by adding iron salts. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that P. placenta growth inhibition is the result of tropolone metal chelation, leading to limitation of available iron (or other essential minerals). Although P. placenta, like other wood rot fungi, synthesizes extracellular iron-binding compounds (14, 22, 23), it is not able to overcome this inhibition, demonstrating the high affinity of tropolone for iron. Similar microbe-inhibitory effects of tropolone have been reported previously on the growth of Tuber borchii (27), Listeria monocytogenes (9), Aureobasidium pullulans, Penicillium glabrum, and Trichoderma harzianum (17). Nevertheless, P. placenta is able to overcome the inhibitory effects of tropolone on malt-agar medium when colonization started from a tropolone-free area.

These data, correlated with tropolone inhibition of P. placenta growth, suggest that the fungus is able to mobilize iron (or other essential minerals) and to transport it to areas of high tropolone concentration. It is well known that fungi are able to reallocate nutrients between different parts of their mycelium (5, 7, 21). However, descriptions of the translocation of essential minerals are not as detailed as they are for N, S, and P, and the biochemical mechanisms remain largely unknown. The model developed in this study with tropolone and P. placenta could be useful for studying such phenomena.

Interestingly, P. placenta is not able to degrade tropolone-treated wood even when colonization is started from tropolone-free areas. This phenomenon could also be related to the wood degradation mechanisms rather than to metabolism inhibition, since the fungus seems to be able to reallocate essential minerals and to grow in the presence of tropolone. In this study, we also demonstrated that wood protection induced by tropolone could not be explained by its very weak antioxidant properties. Since the presence of the tropolone hydroxyl group is important, the chelating properties of this compound are probably involved in the observed wood degradation inhibition.

Iron, hydrogen peroxide, and biochelators such as catecholate compounds are believed to play essential roles in wood degradation by brown rot fungi. Iron is probably present in wood in its insoluble, oxidized form (32). In the model described by Goodell and coauthors, oxalate lowers the pH of the decay environment and sequesters iron from cellulose. At the appropriate pH, iron is sequestered from this complex by biochelators (catecholates) and is reduced to Fe(II), allowing the Fenton reaction to proceed in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Maximal degradation in this system occurs at approximately pH 4 (16, 32). The oxidation of catecholates by Fe3+ is thermodynamically possible between pH 6 and pH 1.

The E-pH diagram calculated from constants determined in this study shows that iron sequestration by tropolone thermodynamically inhibits this reaction. Indeed, for instance, at pH 5, the redox potential of Fe(Trop)3/Fe2+ couple is about 0 mV, while that of the Fe(OH)3/Fe2+ couple is about 700 mV. In the same conditions, the redox potential of the 4-tert-butyl-o-benzoquinone/4-tert-butylcatechol couple chosen as the catecholate example is about 600 mV (15). Complex formation between tropolone and Fe3+ strongly lowers the redox potential of the iron couple, thermodynamically preventing its reaction with potential reductants such as catecholates. This is consistent with our experimental results showing that the presence of tropolone strongly inhibits Fe3+ reduction by either 4-tert-butylcatechol or 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (Fig. 6).

All the data presented in this study are consistent with the model proposed by Goodell and coworkers, showing indirectly the importance of iron in wood degradation by brown rot fungi.

Since the Fenton reaction is important for the initial attack by brown rot fungi, it follows that breakdown of polymeric material should be inhibited by a chelating agent that is unable to reduce the Fe(III) complex to Fe(II) under physiological conditions (this is the case with tropolone) or in which the Fe(II) complex has a negligible rate constant for HO. formation. Furthermore, in this study, we demonstrated that putative metal translocation occurring in the fungus is not able to overcome tropolone effects on wood degradation, this property being important for the use of tropolone as a wood preservative. Taking into account the essential role of iron in wood degradation by brown rot fungi, iron chelators such as tropolone could also be involved in novel and more environmentally benign preservative systems. Nevertheless, further work, particularly in the field, will be necessary to determine the applicability of this method.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, A. B., T. C. Scheffer, and C. G. Duncan. 1962. On the decay retardant properties of some tropolones. Science 137:859-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arima, Y., A. Hatanaka, S. Tsukihara, K. Fujimoto, K. Fukuda, and H. Sakurai. 1997. Scavenging activities of α-. β-, γ-thujaplicins against active oxygen species. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 45:1881-1886. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barclay, L. C. R., C. E. Edwards, and M. R. Vinqvist. 1999. Media effect on antioxidant activities of phenols and catechols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:6226-6231. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baya, M., P. Souylounganga, E. Gelhaye, and P. Gerardin. 2001. Fungicidal activity of β-thujaplicin analogues. Pest Manag. Sci. 57:833-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boddy, L. 1999. Saprophotic cord-forming fungi: meeting the challenge of heterogeneous environments. Mycologia 91:13-32. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravery, A. F. 1978. A miniaturised wood-block test for the rapid evaluation of wood preservation fungicides. IRG special seminar on screening techniques for potential wood preservative chemicals. IRG document no. IRG/WP/2113, paper 8. International Research Group in Wood Preservation, Stockholm, Sweden.

- 7.Cairney, J. W. G. 1992. Translocation of solutes in ectomycorrhizal and saprophitic rhizomorphs. Mycol. Res. 96:135-141. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claudia, E., T. Ulrike, and K. L. Ericksson. 1996. The lignolytic system of the white rot fungus Pycnoporus cinnabarinnus: purification and characterization of the laccase. App. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1151-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulanges, V., P. Andre, and D. Vidon. 1998. Effect of siderophores, catecholamines, and catechol compounds on Listeria spp. gowth in iron-complexed medium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 249:526-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowling, E. B. 1961. Comparative biochemistry of the decay of sweet-gum by white- and brown rot fungi. USDA Tech. Bull. 1258. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Eloualja, H., D. Perrin, and R. Martin. 1995. Influence of β-carotene on the induced oxidation of ethyl linoleate. New. J. Chem. 19:1187-1198. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enoki, A., H. Tanaka, and G. Fuse. 1989. Relationship between degradation of wood and production of H2O2-producing and one-electron oxidase by brown rot fungi. Wood Sci. Technol. 23:1-12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espin, J. C., and H. J. Wichers. 1999. Slow-binding inhibition of mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) tyrosinase isoforms by tropolone. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 47:2638-2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekete, F. A., V. Chandhoke, and J. Jellison. 1989. Iron-binding compounds produced by wood-decaying basidiomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:2720-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golabi, S. M., and D. Nematollahi. 1997. Electrochemical study of 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid and 4-tert-butylcatechol in the presence of 4-hydroxycoumarin. Application to the electro-organic synthesis of coumestan derivatives. J. Electroanal. Chem. 430:141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodell, B., J. Jellison, J. Liu, G. Daniel, A. Paszczynski, F. Fekete, S. Krishnamurthy, L. Lu, and G. Xu. 1997. Low molecular weight chelators and phenolic compounds isolated from wood decay fungi and their role in the fungal biodeterioration of wood. J. Biotechnol. 53:133-162. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gros, B. M., and B. Kunz. 1998. Fungitoxicity of chemical analogs with heatwood toxins. Curr. Microbiol. 37:67-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hingston, J. A., C. D. Collins, R. J. Murphy, and J. N. Lester. 2001. Leaching of chromated copper arsenate wood preservatives: a review. Environ. Pollut. 111:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inamori, Y., Y. Sakagami, Y. Morita, M. Shibata, M. Sugiura, Y. Kumeda, T. Okabe, H. Tsujibo, and N. Ishida. 2000. Antifungal activity of hinokitiol-related compounds on wood-rotting fungi and their insecticidal activities. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 8:995-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerem, Z., K. A. Jensen, and K. E. Hammel. 1999. Biodegradative mechanism of the brown rot basidiomycete Gloeophyllum trabeum: evidence for an extracellular hydroquinone-driven Fenton reaction. FEBS Lett. 446:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindahl, B., R. Finlay, and S. Olsson. 2001. Simultaneous, bidirectional translocation of 32P and 33P between wood blocks connected by mycelial cords of hypholoma fasciculare. New Phytol. 150:189-194. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milagres, A. M. F., A. Machuca, and D. Napoleao. 1999. Detection of siderophore production from several fungi and bacteria by a modification of chrome azurol S (CAS) agar plate assay. J. Microbiol. Methods 37:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neidlands, J. B. 1995. Siderophores: structure and function of microbial iron transport compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26723-26726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohira, T., F. Terauchi, and M. Yatagai. 1994. Tropolones extracted from the wood of western red cedar by supercritical carbon dioxide. Holzforschung 48:308-312. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parra, C., J. Rodriguez, J. Baeza, J. Freer, and N. Duran. 1998. Iron-Binding catechols oxidating lignin and chlorolignin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 251:399-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietra, F. 1973. Seven-membered conjugated carbo- and heterocyclic compounds and their homoconjugated analogs and metal complexes. Synthesis, biosynthesis, structure, and reactivity. Chem. Rev. 73:293-364. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poma, A., G. Pacioni, S. Colafarina, and M. Miranda. 1999. Effect of tyrosinase inhibitors on Tuber borchii mycelium growth in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pourbaix, M., and N. Zoubon. 1974. Iron, p. 307-321. In Atlas of electrochemical equilibria in aqueous solutions. National Association of Corrosion Engineers, Houston, Tex.

- 29.Schultz, T. P., and D. D. Nicholas. 2000. Naturally durable heartwood: evidence for the proposed dual defensive function of the extractives. Phytochemistry 54:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stookey, L. L. 1970. Ferrozine: a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal. Chem. 42:779-782. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, M., Y. Jin, and C.-T. Ho. 1999. Evaluation of resveratrol derivatives as potential antioxidants and identification of a reaction product of resveratrol and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryhydrazyl radical. J. Agric. Food Chem. 47:3974-3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu, G., and B. Goodell. 2001. Mechanisms of wood degradation by brown rot fungi: chelator-mediated cellulose degradation and binding of iron by cellulose. J. Biotechnol. 87:43-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi, T., K. Fujita, and K. Sakai. 1999. Biological activity of extracts from Cupressus lusitanica cell culture. J. Wood Sci. 45:170-173. [Google Scholar]