Abstract

Determining the dynamics of adsorbed liquids on nanoporous materials is crucial for a detailed understanding of interactions and processes on the solid-liquid interface in many materials and porous systems. Knowledge of the influence of the presence of paramagnetic species on the surface or within the porous matrices is essential for fundamental studies and industrial processes such as catalysts. Magnetic resonance methods, such as electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP), are powerful tools to address these questions and to quantify dynamics, electron-nuclear interaction features and their relation to the physical-chemical parameters of the system. This paper presents an NMR study of the dynamics of polar and nonpolar adsorbed liquids, represented by water, n-decane, deuterated water and nonane-d20, on the native silica surface as well as silica modified with vanadyl porphyrins. The analysis of the frequency dependence of the nuclear spin-lattice relaxation time is carried out by separating the intra- and intermolecular contributions, which were analyzed using reorientations mediated by translational displacements (RMTD) and force-free-hard-sphere (FFHS) models, respectively.

Keywords: NMR relaxation, Fast field cycling, Porous media, DNP, Porphyrins

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

A deep understanding of adsorbed liquids dynamics is critical to fundamental studies as well as to many industrial applications such as catalysis, filtrations, chromatography, etc. Silica is a widely used material, also as a model adsorbent for studying fundamental processes on the solid-liquid interface. The hydroxyl-rich and polar native surface of silica can be modified by adsorbing or chemically bonding different substances, changing the polarity and hydrophobicity of the former, which allows for modelling some natural processes, such as the ageing of rocks [1,2], when organic molecules similar to crude oil are deposited on the silica surface. Paramagnetic metal ions or organic radicals adsorbed on the silica surface can also serve as a spin probe of surface dynamics and specific interaction on the solid-liquid interface [[3], [4], [5]]. Materials based on vanadium on silica surfaces are widely used in industry as catalysts [6,7].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) provides a specific and precise tool to study the dynamics of complex systems through the determination of spin relaxation properties. The inter- and intramolecular spin interactions modulated by the characteristic molecular dynamics in the system are responsible for nuclear spin relaxation. Field cycling NMR [8] is a powerful technique to determine the frequency-dependent spin-lattice relaxation dispersion, usually known as NMR relaxation dispersion (NMRD), which is measured in a wide range of magnetic fields. NMRD provides the means to determine the spectral densities of the dynamical modes in a system under study and the further estimation of the corresponding correlation times. Theoretical models describing the molecular dynamics and the NMR relaxation properties of adsorbed liquids on the clean surface of porous media and in the presence of paramagnetic species have been described for several decades [[9], [10], [11]]. One of the models describing spin-lattice relaxation time frequency dependence of adsorbed liquids in the absence of a significant amount of paramagnetic impurities is reorientations mediated by translational displacements (RMTD). In the case of strong adsorption, the preferential orientation of adsorbed molecules in addition to translational diffusion along the surface leads to relaxation time dispersion reflecting the curvature of the pores at comparably low frequencies of MHz and below. The model as well predicts no significant dispersion in the case of weakly adsorbing species [9]. Thus, the RMTD dynamics is considered purely intramolecular by nature, which leads to similar dispersion for 1H and 2H species, e.g. H2O and D2O, allowing to distinguish intra- and intermolecular contributions to the NMR relaxation [12]. However, in the presence of dominating paramagnetic relaxation, e.g. due to the presence of metal ions, such as Fe3+ or Mn2+, relaxation dispersion is transformed and can be described by diffusion with respect to the surface containing paramagnetic ions, distinguishing between protic and aprotic liquids [[13], [14], [15]]. In contrast to RMTD, dynamics modulating electron-nuclear interactions are supposed to be intermolecular. Additionally, using more simple models, such as the force-free-hard-sphere model (FFHS) [16], to describe the diffusion of adsorbed liquids in the presence of paramagnetic species is well-known in the literature [17].

Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) is a well-known technique to increase the sensitivity of NMR measurements up to several orders of magnitude [18]. Apart from a tremendous gain in sensitivity and selectivity of NMR measurements, information about dynamics in the system using analysis of DNP data is available. The most common low-field DNP mechanisms, the Overhauser effect (OE) [19] and solid effect (SE) [20,21], in general, are related to DNP processes in low-viscous liquids and solids, respectively. The combination of OE and SE is common for viscous liquids [22,23] and systems characterized by a variety of phases [24,25]. Both DNP mechanisms also depend on nuclear and electron relaxation properties, which are, in general, related to the dynamics and corresponding processes in the system under study [26]. Thus the combination of NMRD and DNP [[27], [28], [29]] data allows for maintaining a more detailed and precise investigation of dynamics in complex systems.

In this paper, the NMRD and DNP of adsorbed water and alkanes in native silica and silica modified by vanadyl porphyrins are studied in order to reveal dynamical modes and corresponding correlation times. Distinguishing between intramolecular and intermolecular contribution to the relaxation is performed by measuring 2H NMRD of deuterated water and nonane-d20 in the silica samples. DNP data were used to estimate the possible contributions of different dynamics to the NMR relaxation processes.

2. Materials and methods

Relaxation dispersion measurements were carried out by using an fast field cycling (FFC) relaxometer (Spinmaster FFC2000, Stelar, Mede, Italy) at magnetic field strengths between 0.1 mT and 0.6 T. For detection, the probes were tuned to 16.7 MHz or 3.4 MHz for 1H and 2H target nuclei, respectively. The detection field was set at corresponding strengths of 392 mT and 525 mT for 1H and 2H nuclei, respectively.

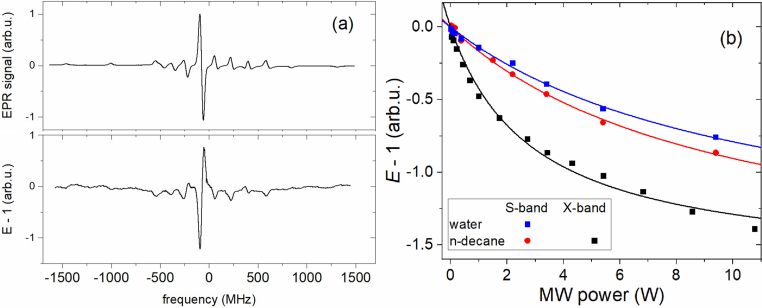

DNP spectra were measured using homebuilt X-band and S-band resonators operating at about 9.6 GHz and 2 GHz, respectively. The details of the experimental setup can be found in previous works [30,31].

Continuous wave (CW) EPR measurements, with the purpose of controlling the concentration of vanadyl in modified silica, were carried out by using a benchtop X-band (9.2–9.6 GHz) EPR spectrometer Magnettech 5000 (Magnettech, Freiberg Instruments, Freiberg, Germany). The vanadyl concentration in the modified silica samples was estimated at room temperature by comparison of the integrated intensities of EPR spectra and reference samples (powder of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, Mn2+ in MgO, a series of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine 1-oxyl solutions).

Vanadyl octaethylporphyrines 2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octaethyl-21H,23H-porphine vanadium (IV) oxide (VOOEP) (Sigma Aldrich, 95%) (see Fig. 1) was dissolved in benzene for 24 h in an ultrasonic bath at 310 K. The silica 7 nm nanoparticles (Sigma Aldrich) with a surface area of 380 m2/g were added to the VOOEP solution and stirred for 12 h. Centrifuged silica particles with adsorbed VOOEP were washed with n-heptane with further drying at 340 K and 10 mbar. The final concentration of VOOEP on the silica surface was estimated as 6.2 × 1019 spins/g, or 0.16 spins/nm2, using EPR. The pure silica was dried at 340 K and at a pressure of 10 mbar for 12 h. The liquids were added to silica powder at 0.6 mL/g for all liquids (H2O, D2O, n-decane, nonane-d20) without additional manipulations in order to obtain a homogeneous distribution of liquid in the sample.

Fig. 1.

2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octaethyl-21H,23H-porphine vanadium (IV) oxide (VOOEP).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion

The experimental NMRD, obtained for n-decane/nonane-d20 and water/D2O adsorbed in pure silica and silica modified with VOOEP, are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

1H (a) and 2H (b) NMRD (relaxation rate R1 as a function of Larmor frequency ν = ω/2π) of H2O/D2O and n-decane/nonane-d20 in silica without (“SA”) and with (“SA-VOOEP”) modification with VOOEP. The lines correspond to fits using equations (4) and (5).

The effect of modifying the silica surface with VOOEP on the 1H relaxation is different for water and n-decane. While n-decane exhibits an expected increasing 1H relaxation rate due to the presence of paramagnetic VOOEP on the silica surface, the water relaxation rate is reduced, which is especially pronounced at the low frequencies. The difference must be related to the dominating relaxation mechanism, which can be assigned either to the nuclear-nuclear or electron-nuclear interactions. In general, the relaxation rate, in that case, can be defined as a sum of intermolecular and intramolecular relaxation rates:

| (1) |

where the total intermolecular relaxation rate consists of both contributions from nuclear-nuclear and electron-nuclear Interactions. These relaxation rates can be expressed in terms of spectral density functions as follows [32]:

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

where constant prefactors and are related to the number of spins, distances between interacting spins, and their gyromagnetic ratios. Additionally to equation (1), when the effects of surface in porous materials on NMR relaxation is considered, the presence of dominating fraction of the adsorbed molecules belonging to bulk is taken into account as a result of averaging out of both surface and bulk relaxation rates due to the self-diffusion:

| (4) |

where are relative weights of surface and bulk molecules [32,33]. While relaxation rate can be related to the several dynamics model, relaxation rate is considered as a constant contribution in the conventional FFC frequency range [8,32]. Similarly, the other relaxation contributions, which are characterized by the absence of relaxation dispersion in the frequency range of the FFC technique, are considered constant values, e.g. relaxation rates of bulk liquid or (see Table 1), in the whole available frequency range.

Table 1.

Fitting parameters for RMTD and FFHS models used to fit 1H and 2H NMRD using equation (5) for RMTD and equations (2), (3), (4)with spectral density function expressed with equation (7) for FFHS model.

| Sample | Water/D2O |

n-decane/nonane-d20 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | SA-VOOEP | SA | SA-VOOEP | |

| Intramolecular, RMTD | ||||

| , μs | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| , μs | 50 ± 6 | 48 ± 5 | 60 ± 9 | 40 ± 12 |

| , × 103/s2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.88 ± 0.1 | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.03 |

| , s−1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| Intermolecular, FFHS | ||||

| , μs | 10 ± 4 | 30 ± 20 | 20 ± 12 | 10 ± 8 |

| , × 105/s2 | 15.5 ± 3.2 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.4 |

| , s−1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | – |

| , ns | – | 0.09 ± 0.03 | – | 95 ± 22a |

| , × 109/s2 | – | 1.1 ± 0.3 | – | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

The value obtained with the fitting parameter of = 8.0 ± 1.8 ns in equation (9).

The analysis of 1H NMRD can be simplified with 2H NMRD assumed as purely intramolecular, i.e. the quadrupolar relaxation of the 2H nuclei is orders of magnitude larger than their dipolar counterpart. In contrast to the 1H relaxation rate, 2H NMRD for both liquids is similar, comparing data for pure silica and silica modified with VOOEP. This supports the abovementioned assumption that the relaxation of 2H can indeed be considered to be purely intramolecular [2,29,34], while most changes of 1H NMRD are related to changes in electron-nuclear and nuclear-nuclear intermolecular contributions to the relaxation. The mechanism dominating the relaxation of adsorbed liquids in porous media without paramagnetic species on the surface or matrix of the porous material is considered reorientations mediated by translational displacements, or RMTD [9,35]. If normal diffusion is considered along the surface, the Gaussian form well describes the probability density of molecular displacements, characterizing reorientations by the Fourier-transform equivalent of the surface curvature in terms of wavenumbers k. Assuming that all modes are equally weighted, the relaxation via RMTD is expressed as [35,36]:

| (5) |

With and . The prefactor is related to the residual dipole-dipole nuclear interactions in the case of 1H nuclei and quadrupolar interactions for 2H nuclei, which are averaged by local molecular reorientations, as well as diffusion processes. Thus, experimental NMRD is fitted by , where constant similarly to in equation (4) describes the relaxation components, which are characterized by the absence of dispersion in the available via FFC technique frequency window. The fitting parameters , and are presented in Table 1.

In this model, the can be considered as the correlation time related to adsorbed liquid molecular jumps between adsorption sites. On the other end, is associated with either the surface residence time or the finite size of the porous structure, indicating the largest curvature [9,35]. The fitting of data in Fig. 2b exhibits correlation times = 50 μs and = 2 μs for deuterated water and = 60 μs and = 50 ns for nonane-d20 in pure silica samples. The absence of a significant difference between 2H NMRD of the different liquids on native or modified silica surface proves the assumption about intramolecular interactions dominating 2H relaxation processes. Thus, the cut-off of dynamics modes corresponding to is similar for both liquids and related to the pore topology or size of silica, while value of nonane-d20 is almost two order magnitudes lower, which can be assigned to the weaker interaction of nonpolar nonane-d20 with a surface compared with the water molecule. Indeed, the presence of hydroxyl groups on the surface of silica particles, in addition to the polarity of water molecules, results in the more preferential orientation of water molecules compared to alkanes due to the strong hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups. However, n-decane and nonane-d20, which are characterized by similar molecular weight and approximately identical dynamics properties [37], are nonpolar liquids without direct evidence of the presence of hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups on the surface, while van-der-Waals forces remain as dominating interactions of the n-decane molecules with a silica surface. The interactions related to van-der-Waals forces are generally weaker than hydrogen bonds allowing n-decane to experience less preferential orientations on the silica surface. The latter will cause the shifting of the high-frequency cut-off to the observed value of = 50 ns. Additionally, the tenfold reduction of the hydroxyl groups concentration leads to decreasing of the NMRD slope and absolute value of R1 of n-decane down to one order of magnitude (data not shown). Thus, the relatively strong adsorption of n-decane and nonane-d20 on the silica surface can be explained by the interaction with the hydroxyl group without clear proof of the nature of its interaction. Additionally, the fitting parameters exhibit higher values in comparison to the values of relaxation rate of bulk liquids, which can be attributed to the additional dynamics of the adsorbed liquids faster than approximately 10 ns, which leads to the absence of NMRD in the available frequencies range of FFC technique.

In order to separate intra-from intermolecular contributions of the 1H relaxation, the following equation is used:

| (6) |

where is a prefactor related to the ratio of the intramolecular relaxation rates of 1H and 2H in bulk liquids [2]. While assuming dominating intramolecular contribution of deuteron relaxation, relaxation rates of bulk deuterated liquids are measured directly, the was calculated taking into account the measured R1 and literature data about the intramolecular relaxation contribution to the 1H relaxation of bulk water () and n-decane () [38]. Thus, the values of prefactor C in equation (6) are obtained equal to 0.07 and 0.29 for water and n-decane, respectively. The result of the corresponding calculations using equation (6) are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Intermolecular contribution to 1H NMRD of water and n-decane in silica with and without modification with VOOEP calculated using equation (6). The lines correspond to the fitting using equations (2), (3), (4) with spectral density function expressed with equation (7) related to the FFHS model.

The theory of RMTD dynamics was developed as intramolecular relaxation mechanisms and did not take any possible intermolecular interactions into account specifically. Indeed, similar to RMTD dynamics without reorientation though, can be the diffusion along the surface, which is interrupted by bulk diffusion when the molecule leaves the surface. In the same way, the relaxation due to the diffusion of molecules carrying nuclear spins and immobilized electron spins belonging to vanadyl porphyrin complexes can be described by using translational dynamics and assumptions of the FFHS model [16]. Further on, corresponding contributions to the relaxation rate are described by equations (2) and (3) with the spectral density function defined as [16,39,40]:

| (7) |

where and is a correlation time defined as:

| (8) |

with D1 and D2 as self-diffusion coefficients of the molecules carrying interacting spins, whereas d is the minimal distance of approach of interacting spins [16,41]. The latter can be calculated using the van der Waals radius of interacting molecules or functional groups containing interacting spins [42,43]. As it follows from equation (8), the translational dynamics and corresponding correlation time are related to mobility of both diffusing species if the two different molecules are considered interacting. Thus, if one molecule is immobilized or characterized by low diffusivity, e.g. as radicals on the surface [17] or polymer molecules [44], the dynamics is modulated by the mobility of the fastest molecule.

The NMRD of the intermolecular contribution of the relaxation rate of n-decane in silica modified with VOOEP exhibits a maximum relaxation rate dispersion at the frequency of about 500 kHz and can be attributed to the relaxation rate enhancement often observed in organic radicals, paramagnetic metal ions, and contrast agents solutions [15,[45], [46], [47], [48]]. This effect is especially pronounced when relaxation times of electron spins are comparable with correlation times of the dynamics modulating electron-nuclear interactions. The latter is taken as considering intermolecular interaction. Thus the effective correlation time can be derived from two characteristic times as . Note that the electron relaxation time is also frequency dependent, similar to the nuclear relaxation times. For the characteristic correlation time of dynamics modulating electron relaxation, the tumbling correlation time of the electron spin carrier molecule in the solution is considered. However, for paramagnetic species immobilized on the surface or inside the matrix of porous materials, the mechanisms of relaxation can be different. In the current contribution, we assume that the relaxation of the electron can still be expressed using the Lorentzian spectral density function usually applied for a model of a tumbling molecule carrying electron spin, which is a good approximation for many systems [[49], [50], [51]]:

| (9) |

where prefactor is related to the parameters of interacting electron spins and lattice, similar to nuclear spins in equations (2), (3) and (5). Thus, the effective correlation time is used in for equation (7) describing the spectral density function of the FFHS model.

Thus, in order to explain experimental data, the fitting of intermolecular 1H NMRD presented in Fig. 3 is carried out by using equations (2), (3), (4) with spectral density function defined in equation (7), describing a combination of translational dynamics related to interacting either nuclear-nuclear or electron-nuclear spins. The fitting parameters , and related to nuclear-nuclear intermolecular relaxation, as well as and , which are attributed to electron-nuclear interaction, are presented in Table 1.

Further on, correlation times (see Table 1) obtained by fitting experimental data are used to calculate diffusion coefficients of adsorbed liquids around the electron spin of vanadyl in a porphyrin complex. Water in silica exhibits diffusion coefficient D = 1 × 10−9 m2/s, calculated using equation (8) and minimal distance of approach of nuclear and electron spins d = 3 Å, which is approximately the sum of van der Waals radius of the water molecule and VO2+ containing an unpaired electron, with = 90 ps, while one of the diffusion coefficients was taken as zero for immobilized vanadyl complexes on the surface. It is about twice slower as diffusion in bulk water and in good agreement with the value of the diffusion coefficient of water on the silica surface reported in the literature [17]. The correlation time value of around 95 ns obtained from the fitting of experimental data of n-decane in modified silica in Fig. 3 exhibits slower dynamics in comparison with water, resulting in a calculated diffusion coefficient D = 2 × 10−12 m2/s with an assumed value of d = 3 Å. While the diffusion coefficients estimated from the correlation times FFHS model considering electron-nuclear interactions are in a reliable range of values, the values of correlation times of interacting nuclear spins related to the translational dynamics are several order magnitudes higher, i.e in the range of tens microseconds. Despite the acceptable fitting of experimental data with the FFHS model, that discrepancy reveals the limitation of the latter. In other words, the further interpretation of correlation times in a similar way as with the electron-nuclear interaction case is not valid anymore. It should be noted however that the values of are in the same range of values with related to the residence time of the molecules adsorbed on the silica surface (see Table 1). The appropriate development of the dynamics models used in the current contribution in order to reliably describe and quantify the experimental NMRD requires further detailed investigation, which is underway in our group at the moment.

3.2. Dynamic nuclear polarization

The different relaxation mechanisms caused by the presence of electron spins belonging to vanadyl porphyrin complexes were found to be responsible for several mechanisms of DNP via VO2+. The 1H DNP spectra of n-decane adsorbed on silica modified with VOOEP are presented in Fig. 4a. The broad DNP spectrum of about 3 GHz was found to be in good agreement with EPR spectra. The presence of the two positive and negative peaks on the DNP spectrum around zero offset frequency is related to the solid effect DNP mechanism [18,20,21]. Additionally, the different values of the DNP enhancement of SE peaks related to the central line of vanadyl, as well as a negative enhancement related to the sidelines of the vanadyl EPR spectrum, reflect the presence of the Overhauser effect [19,26,52]. Similar DNP spectra were observed for the benzene solution of asphaltenes containing vanadyl porphyrins, except that the central line corresponded to free radicals in the asphaltenes molecules [25]. The presence of both OE and SE DNP mechanisms, which are usually most effective in the two limiting cases of dynamics, i.e. low-viscosity liquids and solids, respectively, corresponds to the transitional dynamics, usually observed in the viscous liquids [22], polymer systems [53,54], anisotropic and heterogeneous systems [24,44].

Fig. 4.

(a) X-band CW EPR (top) and DNP spectrum (bottom) of n-decane in SA-VOOEP and (b) corresponding power dependencies of DNP enhancement of n-decane (X- and S-band) and water (S-band) in SA-VOOEP. The lines are the fitting using equation (13).

Power dependencies of the 1H DNP enhancement of n-decane at X- and S-band and for water at S-band were obtained for the central line of VOOEP EPR spectra with g = 1.98 (see Fig. 4) [25,55]. As for the 2H DNP enhancement of deuterated water and nonane-d20, no detectable enhancement was observed in the studied samples. The absence of 2H DNP enhancement is caused by the so-called differential solid [20,21] effect due to the broad EPR line dominating the nuclear Larmor frequency of deuterium. As for OE DNP, the undetectable 2H radical-induced relaxivity in both D2O and nonane-d20 cases results in a negligible leakage factor due to the mostly intramolecular nature of deuterium relaxation.

In order to correlate DNP data with the dynamics in the system, a three factors approach is used to describe the experimental data related to OE DNP [26,56]:

| (10) |

where , , and are coupling, leakage, and saturation factors, and and are the gyromagnetic ratios of electron and nuclear spins, respectively. The details of the theory related to the factors in equation (10) can be found in the literature [56]. The saturation factor s represents the efficiency of the microwave irradiation and, for a single, homogeneously broadened EPR line, is given as [57]:

| (11) |

where B1 is the magnetic field strength of the microwave field, and T1e and T2e are the corresponding electron relaxation times. The leakage factor f constitutes the paramagnetic relaxation contribution to the nuclear relaxation rate and defined as:

| (12) |

From the power dependency (see Fig. 4b) of the enhancement E(P), the limiting value of enhancement Emax extrapolated to infinite microwave irradiation power can be calculated by reference [58]:

| (13) |

The leakage factors were found from NMR relaxation data equal to 0.70 ± 0.03 and 0.60 ± 0.03, for n-decane at S- and X-band, respectively. A leakage factor of 0.37 ± 0.02 was found for water at S-band. Further on, the saturation factor s in equation (10) was considered as 1/8 due to the 7/2 spin of 51V.

Thus the coupling factor is calculated using experimental OE DNP data and equation (10). On the other hand, DNP enhancement and coupling factor can also be estimated considering corresponding dynamics and the absence of scalar interactions, using the following equation [39]:

| (14) |

OE DNP data of water in modified silica exhibits a calculated coupling factor of 0.05 ± 0.01 for both S- and X-bands, which is similar to the coupling factor calculated using NRMD data. However, for n-decane, DNP data exhibits a coupling factor of 0.03 ± 0.01 at X-band while using the correlation time of n-decane = 95 ns obtained using NMRD data results in a negligibly low coupling factor and corresponding DNP enhancement below experimental error. Thus, in order to explain the presence of OE DNP of n-decane via VOOEP on the silica surface, the contribution of the additional dynamics with correlation times of around 1 ns must be considered. However, the reliable implementation of an additional component to the analysis of NMRD of n-decane requires additional independent data, such as NMRD, DNP and EPR temperature dependencies, as well as diffusion measurements, which are included in the upcoming study.

4. Conclusion

The 1H relaxation of water and n-decane in silica exhibits different ratios of intra- and intermolecular contributions to the relaxation dispersion. While 2H relaxation is considered as a pure intramolecular, the intermolecular contribution was evaluated as dominating for 1H water relaxation in comparison with a tenfold lower intermolecular relaxation rate of n-decane. The analysis of 2H NMRD of adsorbed liquids using the RMTD model shows a similar low-frequency relaxation related to pore topology, while high-frequency relaxation dispersion exhibits stronger adsorption for water in comparison with n-decane. Modifying the surface with vanadyl porphyrins has no effect on the 2H relaxation of both liquids, while 1H relaxation exhibits additional paramagnetic induced relaxivity with still dominating nuclear-nuclear intermolecular contribution for the water relaxation, which is reduced by modifying silica with VOOEP.

The DNP enhancements for both water and n-decane in modified silica exhibit similar behaviour, showing the simultaneous presence of SE and OE DNP as attributes of the presence of both slow and fast dynamics. The combined analysis of DNP and NMRD data showed that OE DNP enhancement is related to the fast dynamics of around 0.1–1 ns range.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bulat Gizatullin: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Carlos Mattea: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Siegfried Stapf: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

Siegfried Stapf is one of Guest Editors for this issue of MRL and was not involved in the editorial review or the decision to publish this article. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Acknowledgement

Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (STA 511/15–1 and −2) is gratefully acknowledged.

Biography

Bulat Gizatullin received an M.Sc. in Physics from the Kazan Federal University. The further post-graduate project at Kazan Federal University was devoted to the topic of NMR relaxation in porous media. He obtained the Ph.D. degree in Physics from the Technical University of Ilmenau, Germany. Currently, he is a postdoctoral fellow in the group of Prof. Stapf based at the Technical University of Ilmenau. The main interest fields include NMR and DNP in the complex systems.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Innovation Academy for Precision Measurement Science and Technology (APM), CAS.

References

- 1.Shikhov I., Li R., Arns C.H. Relaxation and relaxation exchange NMR to characterise asphaltene adsorption and wettability dynamics in siliceous systems. Fuel. 2018;220:692–705. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gizatullin B., Mattea C., Shikhov I., Arns C., Stapf S. Modeling molecular interactions with wetting and non-wetting rock surfaces by combining electron paramagnetic resonance and NMR relaxometry. Langmuir. 2022;38:11033–11053. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c01681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaera F. Surface chemistry at the liquid/solid interface. Surf. Sci. 2011;605:1141–1145. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaera F. Probing liquid/solid interfaces at the molecular level. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2920–2986. doi: 10.1021/cr2002068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gladden L.F., Mitchell J. Measuring adsorption, diffusion and flow in chemical engineering: applications of magnetic resonance to porous media. New J. Phys. 2011;13 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weckhuysen B.M., Keller D.E. Chemistry, spectroscopy and the role of supported vanadium oxides in heterogeneous catalysis. Catal. Today. 2003;78:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luca V., MacLachlan D.J., Bramley R. Electron paramagnetic resonance and electron spin echo study of supported and unsupported vanadium oxides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999;1:2597–2606. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimmich R., Anoardo E. Field-cycling NMR relaxometry. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2004;44:257–320. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stapf S., Kimmich R., Seitter R. Proton and deuteron field-cycling NMR relaxometry of liquids in porous glasses: evidence for Lévy-walk statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995;75:2855–2858. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stapf S., Kimmich R., Seitter R.O., Maklakov A.I., Skirda V.D. Proton and deuteron field-cycling NMR relaxometry of liquids confined in porous glasses. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1996;115:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zavada T., Kimmich R., Grandjean J., Kobelkov A. Field-cycling NMR relaxometry of water in synthetic saponites: Lévy walks on finite planar surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:6977–6981. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flamig M., Becher M., Hofmann M., Korber T., Kresse B., Privalov A.F., Willner L., Kruk D., Fujara F., Rössler E.A. Perspectives of deuteron field-cycling NMR relaxometry for probing molecular dynamics in soft matter. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:7754–7766. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b05109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godefroy S., Korb J.P., Fleury M., Bryant R.G. Surface nuclear magnetic relaxation and dynamics of water and oil in macroporous media. Phys. Rev. E - Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2001;64 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.021605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korb J.P. Nuclear magnetic relaxation of liquids in porous media. New J. Phys. 2011;13 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korb J.P. Multiscale nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion of complex liquids in bulk and confinement. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2018;104:12–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang L.-P., Freed J.H. Dynamic effects of pair correlation functions on spin relaxation by translational diffusion in liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 1975;63:4017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrader A.M., Monroe J.I., Sheil R., Dobbs H.A., Keller T.J., Li Y., Jain S., Shell M.S., Israelachvili J.N., Han S. Surface chemical heterogeneity modulates silica surface hydration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:2890–2895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1722263115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaelis V.K., Griffin R.G., Corzilius B., Vega S. Handbook of High Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization, 1 ed. Wiley. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overhauser A.W. Polarization of nuclei in metals. Phys. Rev. A. 1953;92:411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abragam A., Goldman M. Principles of dynamic nuclear polarisation. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1978;41:395–467. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenckebach W.T. The solid effect. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2008;34:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gizatullin B., Mattea C., Stapf S. Molecular dynamics in ionic liquid/radical systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2021;125:4850–4862. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leblond J., Uebersfeld J., Korringa J. Study of the liquid-state dynamics by means of magnetic resonance and dynamic polarization. Phys. Rev. A. 1971;4:1532–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuzhelev A.A., Dai D., Denysenkov V., Prisner T.F. Solid-like dynamic nuclear polarization observed in the fluid phase of lipid bilayers at 9.4 T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:1164–1168. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gizatullin B., Gafurov M., Murzakhanov F., Vakhin A., Mattea C., Stapf S. Molecular dynamics and proton hyperpolarization via synthetic and crude oil porphyrin complexes in solid and solution states. Langmuir. 2021;37:6783–6791. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.1c00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller-Warmuth W., Meise-Gresch K. Molecular motions and interactions as studied by dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) in free radical solutions. Adv. Magn. Opt. Reson. 1983;11:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofer P., Parigi G., Luchinat C., Carl P., Guthausen G., Reese M., Carlomagno T., Griesinger C., Bennati M. Field dependent dynamic nuclear polarization with radicals in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3254–3255. doi: 10.1021/ja0783207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu G., Levien M., Karschin N., Parigi G., Luchinat C., Bennati M. One-thousand-fold enhancement of high field liquid nuclear magnetic resonance signals at room temperature. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:676–680. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gizatullin B., Mattea C., Stapf S. Field-cycling NMR and DNP - a friendship with benefits. J. Magn. Reson. 2021;322 doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2020.106851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neudert O., Raich H.P., Mattea C., Stapf S., Munnemann K. An Alderman-grant resonator for S-band dynamic nuclear polarization. J. Magn. Reson. 2014;242:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neudert O., Mattea C., Stapf S. A compact X-Band resonator for DNP-enhanced Fast-Field-Cycling NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2016;271:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimmich R. Springer-Verlag Berlin Hedelberg; 1997. NMR Tomography Diffusometry Relaxometry. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brownstein K.R., Tarr C.E. Spin-lattice relaxation in a system governed by diffusion. J. Magn. Reson. 1977;26:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen R.S., Stallworth P.E., Greenbaum S.G., Kleinberg R.L. Effects of hydrostatic pressure on proton and deuteron magnetic resonance of water in natural rock and Artificial porous media. J. Magn. Reson., Ser. A. 1994;110:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stapf S., Kimmich R., Niess J. Microstructure of porous media and field-cycling nuclear magnetic relaxation spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 1994;75:529–537. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silletta E.V., Velasco M.I., Gomez C.G., Strumia M.C., Stapf S., Mattea C., Monti G.A., Acosta R.H. Enhanced surface interaction of water confined in hierarchical porous polymers induced by hydrogen bonding. Langmuir. 2016;32:7427–7434. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freed D.E. Dependence on chain length of NMR relaxation times in mixtures of alkanes. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126 doi: 10.1063/1.2723734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singer P.M., Asthagiri D., Chapman W.G., Hirasaki G.J. Molecular dynamics simulations of NMR relaxation and diffusion of bulk hydrocarbons and water. J. Magn. Reson. 2017;277:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ravera E., Luchinat C., Parigi G. Basic facts and perspectives of Overhauser DNP NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2016;264:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levien M., Hiller M., Tkach I., Bennati M., Orlando T. Nitroxide derivatives for dynamic nuclear polarization in liquids: the role of rotational diffusion. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:1629–1635. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freed J.H. Dynamic effects of pair correlation functions on spin relaxation by translational diffusion in liquids. II. Finite jumps and independent T1 processes. J. Chem. Phys. 1978;68:4034–4037. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merunka D., Peric M. Continuous diffusion model for concentration dependence of nitroxide EPR parameters in normal and supercooled water. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:5259–5272. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peric I., Merunka D., Bales B.L., Peric M. Rotation of four small nitroxide probes in supercooled bulk water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:508–513. doi: 10.1021/jz302107x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gizatullin B., Mattea C., Stapf S. Hyperpolarization by DNP and molecular dynamics: eliminating the radical contribution in NMR relaxation studies. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:9963–9970. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b03246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawson D., Barge A., Terreno E., Parker D., Aime S., Botta M. Optimizing the high-field relaxivity by self-assembling of macrocyclic Gd(III) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:4910–4917. doi: 10.1039/c4dt02971b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vuong Q.L., Gossuin Y., Gillis P., Delangre S. New simulation approach using classical formalism to water nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersions in presence of superparamagnetic particles used as MRI contrast agents. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137 doi: 10.1063/1.4751442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kruk D., Korpala A., Kubica A., Kowalewski J., Rössler E.A., Moscicki J. 1H relaxation dispersion in solutions of nitroxide radicals: influence of electron spin relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138 doi: 10.1063/1.4795006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roch A., Muller R.N., Gillis P. Theory of proton relaxation induced by superparamagnetic particles. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:5403–5411. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du J.-L., Eaton G.R., Eaton S.S. Electron spin relaxation in vanadyl, copper(II), and silver(II) porphyrins in glassy solvents and doped solids. J. Magn. Reson., Ser. A. 1996;119:240–246. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biller J.R., Elajaili H., Meyer V., Rosen G.M., Eaton S.S., Eaton G.R. Electron spin-lattice relaxation mechanisms of rapidly-tumbling nitroxide radicals. J. Magn. Reson. 2013;236:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biller J.R., McPeak J.E., Eaton S.S., Eaton G.R. Measurement of T1e, T1N, T1HE, T2e, and T2HE by Pulse EPR at X-Band for Nitroxides at Concentrations Relevant to Solution DNP. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2018;49:1235–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parigi G., Ravera E., Bennati M., Luchinat C. Understanding overhauser dynamic nuclear polarisation through NMR relaxometry. Mol. Phys. 2018;117:888–897. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neudert O., Reh M., Spiess H.W., Münnemann K. X-band DNP hyperpolarization of viscous liquids and polymer melts. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015;36:885–889. doi: 10.1002/marc.201500036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neudert O., Mattea C., Stapf S. Molecular dynamics-based selectivity for fast-field-cycling relaxometry by overhauser and solid effect dynamic nuclear polarization. J. Magn. Reson. 2017;276:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biktagirov T.B., Gafurov M.R., Volodin M.A., Mamin G.V., Rodionov A.A., Izotov V.V., Vakhin A.V., Isakov D.R., Orlinskii S.B. Electron paramagnetic resonance study of rotational mobility of vanadyl porphyrin complexes in crude oil asphaltenes: probing the effect of thermal treatment of heavy oils. Energy Fuels. 2014;28:6683–6687. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hausser K.H., Stehlik D. Dynamics nuclear polarization in liquid, Adv. Magn. Reson. 1968:79–139. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4832-3116-7.50010-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abragam A. Oxford University Press; 1961. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neudert O., Mattea C., Spiess H.W., Stapf S., Münnemann K. A comparative study of 1H and 19F Overhauser DNP in fluorinated benzenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013;15:20717–20726. doi: 10.1039/c3cp52912f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]