Abstract

The abilities of four models to describe nitrogenase light-response curves were compared, using the heterocystous cyanobacterium Nodularia spumigena and a cyanobacterial bloom from the Baltic Sea as examples. All tested models gave a good fit of the data, and the rectangular hyperbola model is recommended for fitting nitrogenase-light response curves. This model describes an enzymatic process, while the others are empirical. It was possible to convert the process parameters between the four models and compare N2 fixation with photosynthesis. The physiological meanings of the process parameters are discussed and compared to those of photosynthesis.

Cyanobacteria are oxygenic photoautotrophic microorganisms, and many species are capable of diazotrophic growth, i.e., possess the ability to fix N2 (3). This property allows such organisms to form dense water blooms in N-depleted aquatic environments. Freshwater and brackish environments often develop blooms of heterocystous cyanobacteria (8). The heterocyst is a differentiated cell that is the site of N2 fixation in these organisms. It is devoid of the oxygenic photosystem II, and the anoxic interior of the heterocyst provides an environment in which the oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase is protected (14).

Because N2 fixation in heterocystous cyanobacteria is partly dependent on light, light-response curves have been recorded in a manner similar to those done for photosynthesis (10). N2 fixation in cyanobacteria is often measured either at ambient light or at a fixed light intensity in the laboratory considered to be saturating, i.e., resulting in maximum nitrogenase activity. In the former case, it is assumed that the measured nitrogenase activity represents the actual activity of the organisms in their natural environment. However, it would be more informative to measure potential N2 fixation rates at different irradiances that are not influenced by ambient light fluctuations. The mathematical formulation of the nitrogenase-versus-irradiance curve can then be used for the calculation of the actual rate of N2 fixation at any incident irradiance. Hence, it would be possible to calculate daily and water column-integrated rates of N2 fixation (12). Measurement and fitting of a light-response curve of nitrogenase activity not only provide the actual rate of N2 fixation at a given irradiance (11) but also give a variety of physiological parameters, e.g., light affinity coefficient, light saturation coefficient, maximum nitrogenase activity, and nitrogenase activity in the dark. These parameters can give information about the physiological status of the organism as well as its adaptation to different light regimens, in this case with respect to N2 fixation.

In photosynthesis research, the models of Webb et al. (15) and of Jassby and Platt (7) have been most commonly used. Both models describe the photosynthesis-versus-irradiance curves rather well, but since they yield different values for the photosynthesis parameters, the results cannot readily be compared. These models have also been applied to fit nitrogenase-versus-irradiance curves (6, 11, 12, 16) in order to calculate daily integrals of N2 fixation, which were then compared with daily integrals of photosynthesis (6, 11, 12). The Webb model has been modified to account for inhibition of nitrogenase activity at high irradiances by including an inhibition term β (11). However, it was subsequently demonstrated that in heterocystous cyanobacteria, inhibition of nitrogenase activity at high irradiances was an incubation artifact, and therefore no such term was needed (10).

In this study we tested the fit results of four different models for N2 fixation-versus-irradiance curves. The curves were recorded from laboratory cultures of Nodularia spumigena, a heterocystous cyanobacterium isolated from the Baltic Sea and from natural populations of heterocystous cyanobacteria, directly collected from that sea. The aim of this study was to arrive at a recommendation for a model that fits N2 fixation-versus-irradiance curves best and to propose a nomenclature of the parameters derived from these curves and to discuss their meaning in a physiological sense.

Measurements for 40 nitrogenase activity-versus-irradiance curves of natural populations of N2-fixing cyanobacteria were performed during a cruise on the Baltic Sea, 14 to 29 June 1999, on board the RV Valdivia. Samples were collected with a 100-μm-pore-size plankton net, towed vertically through the 0- to 10-m-deep water column and filtered on a GF-F glass-fiber filter (Whatman) (diameter, 47 mm). The filters were incubated at seawater temperature (12 to 15°C, depending on the location) in a temperature-controlled incubator for on-line measurements of N2 fixation (9). The phytoplankton in the samples was dominated by the N2-fixing, heterocystous cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon sp. and N. spumigena.

A culture of N. spumigena isolated from the Baltic Sea was obtained from P. K. Hayes (Bristol University, Bristol, United Kingdom). The organism was grown in a mixture of 1 part of artificial seawater medium (ASN3) and 2 parts of freshwater medium (BG11) (9). The medium did not contain a source of combined nitrogen. Batch cultures were grown at 20°C and continuous light (incident photon irradiance, 40 μmol m−2 s−1) in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks, containing 100 ml of medium, incubated in an orbital-shaking incubator (Sanyo Gallenkamp, Loughborough, United Kingdom) at 120 rpm. Nineteen light-response curves were recorded from samples taken from exponentially growing cultures.

Nitrogenase activity was measured by the acetylene reduction assay, using an on-line technique (10). The gas flow through the incubator was 1 liter h−1 and consisted of 0.036% CO2, 10% C2H2, 20% O2, and 70% N2. When anaerobic conditions were required, O2 was omitted and N2 was increased to 90%. Ethylene was measured using a gas chromatograph (Shimadzu GC-14A), equipped with a flame ionization detector and a 1-ml stainless steel sample loop. The temperatures of injector, detector, and oven were set at 90, 120, and 55°C, respectively. The carrier gas used was He (highest purity available) at a flow rate of 10 ml min−1. The supply rates of H2 and air for the flame ionization detector were 30 and 300 ml min−1, respectively. The column used was a 25-m-long wide-bore silica fused column (inner diameter, 0.53 mm) packed with Porapak U (Varian-Chrompack, Middelburg, The Netherlands).

The gas chromatograph was programmed to automatically inject every 4 min via the sample loop. After injection, the gas chromatograph sent a signal to a personal computer that triggered the change of a neutral density filter in a Leica slide projector with a 250-W halogen lamp, resulting in a change of irradiance in the measuring cell. A set of 10 neutral density filters (Balzers, Sint-Truiden, Belgium) was used, with sufficiently high attenuation to obtain good resolution at the low irradiance levels. This allowed automatic recording of light-response curves, increasing the photon irradiance exponentially from 0 to 1,600 μmol m−2 s−1. Light-response curves were always preceded by three injections in the dark at the start of the experiment. The light-response curve was recorded running from low to high irradiance. The total recording time of a light-response curve took 56 min.

Photosynthetically active radiation was measured by a quantum sensor (LiCor model 250), put in place of the measuring cell and covered by the glass window of the incubation cell.

After the N2 fixation rate was measured, the filters containing the samples were lyophilized and subsequently stored at −80°C until analysis. Chlorophyll a was extracted with 90% acetone in the dark and subsequently analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (10).

Light-response curves were fitted using four different models originating from photosynthesis research (Table 1). The respiration term Rd was replaced by Nd, denoting nitrogenase activity in the dark. The parameter Pm was replaced by Nm, indicating the maximum nitrogenase activity in the light, minus Nd. The light affinity coefficient α is the derivative of the curve at irradiances approaching zero. Models 1 and 2 were both derived from the Michaelis-Menten equation for enzyme kinetics. In model 1, Ik stands for the light saturation coefficient, which equals Nm/α, and replaces Km, a measure for the substrate affinity of an enzyme. Model 2 is the same as model 1, except that the two terms in the denominator are squared and the square root of the whole denominator is taken. Models 3 and 4 represent, respectively, the linear and quadratic approximation of the model that describes the rate of change of nitrogenase activity versus irradiance as a function of nitrogenase activity (2). In this study, the models did not include a term to describe photoinhibition of nitrogenase because this was not observed. In order to derive the total maximum nitrogenase activity, Nd must be added to Nm, resulting in the parameter Ntot.

TABLE 1.

Equations of the four models used to describe the nitrogenase-versus-irradiance relationship, their dimensionless NIk/Nm ratios, and the average N2 fixation coefficients at 20% O2 from cultured N. spumigena estimated by the different modelsa

| Model | Model equation | Reference | NIk/Nm | Nd | Nm | α | r2 | I1/2 formula | I1/2 value | Conversion factor Ik | Conversion factor α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

1 | 0.50 | 13.9 ± 11.2 | 23.1 ± 21.4 | 1.57 ± 1.39 | 0.97 ± 0.04 |  |

Ik1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 |  |

13 | 0.71 | 14.4 ± 11.4 | 20.6 ± 18.9 | 0.80 ± 0.73 | 0.96 ± 0.04 |  |

0.57735Ik2 | 1.732052 | 0.57735 |

| 3 |  |

15 | 0.63 | 14.4 ± 11.3 | 20.6 ± 18.9 | 0.94 ± 0.87 | 0.96 ± 0.04 |  |

0.69314Ik3 | 1.442695 | 0.693147 |

| 4 |  |

7 | 0.76 | 14.6 ± 11.4 | 20.0 ± 18.3 | 0.70 ± 0.64 | 0.96 ± 0.04 |  |

0.54931Ik4 | 1.820479 | 0.54306 |

The N2 fixation coefficients (means ± standard deviations; n = 19) at 20% O2 from cultured N. spumigena estimated by the four models are shown. Nd (micromoles of C2H4 per milligram of chlorophyll a per hour) is the nitrogenase activity measured in the dark, Nm (micromoles of C2H4 per milligram of chlorophyll a per hour) is the nitrogenase activity at saturating irradiances minus Nd, and α [micromoles of C2H4 per milligram of chlorophyll a per hour (micromoles of photons per square meter per second)−1] is the light affinity coefficient for nitrogenase activity. I1/2 is the irradiance at which 0.5 of the maximum nitrogenase activity is obtained, and Ik is the light saturation parameter. Note that these parameters are equal in model 1. Values of Ik and α obtained from one model can be converted to the models, assuming that the estimates of Nm by all models were approximately equal. The quality of the fit is given by r2. Standard deviations are given for four parameters and result from differences in chlorophyll-normalized nitrogenase activity. The average errors from the fit of the light-response curve were 6, 7, and 22% of the estimated values for the parameters Nd, Nm, and α, respectively.

Fitting of the different models to the measured light-response curves was done with Microcal Origin 6.0 (Microcal Software Inc.) by nonlinear least-squares fitting using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. The program estimates the parameters and their errors as well as the r2 value. The latter was used as an indicator of fit quality of the fitted line through the measured points.

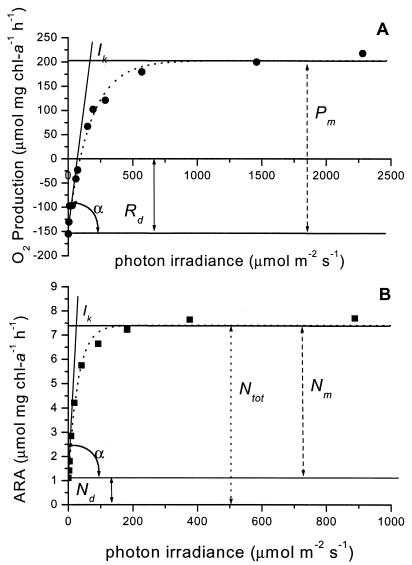

Nitrogenase activity-versus-irradiance curves showed a similar response to light as photosynthesis (Fig. 1), except that N2 fixation also takes place in the dark and hence a positive term, Nd, had to be included, while respiration in a photosynthesis curve results in O2 uptake in the dark (Rd). Fitting nitrogenase-versus-light-response curves (at 20% O2) with the rectangular hyperbola (model 1 [Table 1]) gave activity in the dark representing 34% ± 9.8% (n = 40) and 43% ± 11.6% (n = 19) of the total maximum activity measured with saturating light in natural field populations and laboratory cultures of N. spumigena, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Photosynthesis (O2 evolution) (A) and nitrogenase acetylene reduction (ARA) (B) light-response curves for N. spumigena. Both curves were fitted with the model proposed by Webb et al. (15). The parameters fitted by this model are indicated (Pm or Nm, Rd or Nd, and α) as well as the parameters Ik and Ntot. chl-a, chlorophyll a.

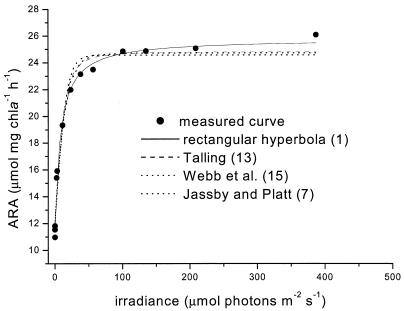

The shape of the fitted light-response curve differed slightly, depending on the model used (Fig. 2). When r2 for the whole curve was taken as a measure for the quality of the fit (Table 1), the differences that were found between the models were not significant (analysis of variance [ANOVA], P > 0.05).

FIG. 2.

The fit results of the four different models, given in Table 1, to a measured light-response curve of nitrogenase activity (acetylene reduction assay [ARA]). chla, chlorophyll a.

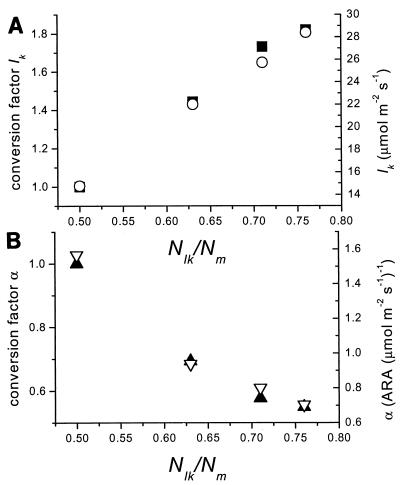

All models estimated the parameters Nm, Nd, and α. The fit results between the different models did not result in different values for nitrogenase activity in the dark, and hence, the value of Nd was estimated independently of the models used. The models also estimated approximately the same Nm, with the exception of the rectangular hyperbola, which gave a higher value for this parameter. Nevertheless, Nm values estimated by the models were not significantly different (ANOVA, P > 0.05). The models gave significantly different values for α (ANOVA, P < 0.05) (Table 1), which were consistent for all measured curves and were related to the shapes of the modeled curves. The ratio of the nitrogenase activity at irradiance Ik and Nm ( /Nm) was taken as an indicator for the shape of the curve. There was a good correlation between the model used (expressed as

/Nm) was taken as an indicator for the shape of the curve. There was a good correlation between the model used (expressed as  /Nmax) and the estimated value of Ik (fitted with linear regression; r2 = 0.99, n = 4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A) and with α (fitted with the inverse of a linear regression 1/(ax + b); r2 = 0.99, n = 4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3B). It was therefore possible to convert Ik and α values in the models. In order to quantify the relationship between the model and the α and Ik parameters, it was assumed that the different models fitted the points equally well and therefore should give approximately the same values for Nd and Nm. Because of similarity of fit quality for the different models, it was also assumed that the light intensity at which the light-dependent part of nitrogenase activity reached 0.5 Nm (I1/2) was equal for all models. The relationship of I1/2 to Ik then can be derived for each model (Table 1) resulting in factors allowing the conversion of Ik values derived from one model to the Ik value of any of the other models. When Ik and α values from one model were converted to another model, they differed by less than 15% from the derived values obtained directly using the fit routine of that model. The similarity in trend between the average fitted α and Ik values versus

/Nmax) and the estimated value of Ik (fitted with linear regression; r2 = 0.99, n = 4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A) and with α (fitted with the inverse of a linear regression 1/(ax + b); r2 = 0.99, n = 4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3B). It was therefore possible to convert Ik and α values in the models. In order to quantify the relationship between the model and the α and Ik parameters, it was assumed that the different models fitted the points equally well and therefore should give approximately the same values for Nd and Nm. Because of similarity of fit quality for the different models, it was also assumed that the light intensity at which the light-dependent part of nitrogenase activity reached 0.5 Nm (I1/2) was equal for all models. The relationship of I1/2 to Ik then can be derived for each model (Table 1) resulting in factors allowing the conversion of Ik values derived from one model to the Ik value of any of the other models. When Ik and α values from one model were converted to another model, they differed by less than 15% from the derived values obtained directly using the fit routine of that model. The similarity in trend between the average fitted α and Ik values versus  /Nm compared to the calculated conversion factors is striking, underscoring that our assumptions were correct (Fig. 3). This is not the case for photosynthesis-versus-irradiance curves (5). However, now that we have shown that the α and Ik values found for N2 fixation can be converted to the model used for fitting the photosynthesis curves, both processes can be compared.

/Nm compared to the calculated conversion factors is striking, underscoring that our assumptions were correct (Fig. 3). This is not the case for photosynthesis-versus-irradiance curves (5). However, now that we have shown that the α and Ik values found for N2 fixation can be converted to the model used for fitting the photosynthesis curves, both processes can be compared.

FIG. 3.

The average Ik (A) (open circles) and α (B) (open triangles) values from batch cultures of N. spumigena (n = 19) as well as the conversion factors (left y axes) for Ik (closed squares) (A) and α (closed triangles) (B) (see Table 1) plotted against the theoretical  /Nm ratio. This ratio is used to specify the different models for fitting the nitrogenase light-response curves (acetylene reduction assay [ARA]).

/Nm ratio. This ratio is used to specify the different models for fitting the nitrogenase light-response curves (acetylene reduction assay [ARA]).

Mathematically, the photosynthesis parameters Pm, Rd, Ik, and α equal, respectively, Nm, Nd, Ik, and α for N2 fixation. However, the physiological meanings of these parameters are not the same. Pm represents the maximum attainable gross rate of photosynthesis at saturating light. Net photosynthesis equals Pm + Rd (Rd is negative), but it should be taken into account that Rd (respiration in the dark) might differ with irradiance. It is important to note that respiration in the heterocyst continues in the light in order to keep the O2 levels low within the heterocyst and that therefore Nd must be subtracted from the measured nitrogenase activity in the light in order to obtain the activity that is supported by light-mediated ATP generation. Hence, the sum of Nm + Nd, which we denote as Ntot, represents the maximum attainable rate of N2 fixation. In photosynthesis, α and Ik are parameters that mainly give information on the number and size of the photosynthetic reaction centers, while in nitrogenase activity, these parameters are also influenced by the ATP demand of nitrogenase, e.g., the amount of active nitrogenase complexes and the availability of the other substrates of this complex. The α and Ik parameters are sometimes used as indicators of photoacclimation in photosynthesis, in which a lower Ik or a higher α indicate acclimation to lower growth irradiances (5). The same appears to be true for N2 fixation (4)

The great advantage of Ik is that it is independent of the units used to express N2 fixation or photosynthesis. It can therefore be used for comparison of light acclimation of both processes. It does not make a difference which technique was used for determining the light-response curves for N2 fixation (e.g., 15N2 fixation or C2H2 reduction) or how the activities are expressed (e.g., as protein, chlorophyll, carbon, cell number etc.), as long as the same model is used to derive the parameters. The same is true for the Nm/Nd and Ntot/Nd ratios. This is convenient, because N2 fixation rates are usually expressed as biomass, which includes vegetative cells that do not fix N2. Hence, biomass-independent parameters of N2 fixation are superior when describing physiological processes in the heterocyst.

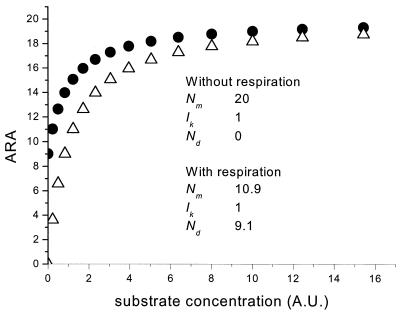

Henley (5) concluded that the models of Jassby and Platt (7) or Webb et al. (15) give the best fit for photosynthesis-versus-irradiance curves. While the fit quality of the different models for nitrogenase-versus-irradiance curves is equal, we propose to use the rectangular hyperbola. The rationale for this choice is that the rectangular hyperbola originates from enzyme kinetics, while the other models are empirical. Nitrogenase-versus-irradiance curves represent in fact the activity of the enzyme in dependence of its limiting substrate (ATP), which is described by the Michaelis-Menten model. Because we assume a linear relationship for ATP production per photon, light-response curves as shown here can be regarded as ATP production versus enzyme activity. Under dark anaerobic incubation conditions, no ATP would be generated and hence nitrogenase activity would be zero (Nd = 0). When light-response curves of nitrogenase activity were measured at air saturation levels of O2, respiration provided considerable amounts of ATP covering a significant part of the demand of nitrogenase (34 and 43% for natural communities and cultured N. spumigena, respectively; see above). The Nd/Ntot ratio determines where the light-dependent part of the curve starts, which has some influence on the tangent of the curve (α) (Fig. 4). Other factors that influence the tangent are the amount of nitrogenase and the quantum efficiency. It is unlikely that these factors change during the recording of the light-response curve. The kinetics of nitrogenase with respect to its limiting substrate ATP are independent of the way ATP is generated (oxidative phosphorylation or photophosphorylation), which means that the affinity of nitrogenase (Ik) (equals Km in Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics) will not change, as long as other substrates for nitrogenase (i.e., reducing equivalents) remain in excess at saturating ATP levels. Theoretically, Ik does not change when Nd changes as long as Ntot remains constant (Fig. 4). This was tested experimentally by removing O2 from the gas flow after the light-response curves were finished in the N. spumigena incubations. Thereafter, the light-response curves were repeated under anaerobic conditions, which resulted in Nd = 0 without affecting Ntot (mostly, Ntot changed less than 10%). However, Nm and α increased with decreasing respiratory ATP production (decreasing O2). These observations agree with the predictions and indicated that the assumptions made were valid. Hence, when Ik and Ntot do not change in response to variation of O2, the conclusion must be that at saturating irradiances, nitrogenase activity is not limited by any of its substrates (ATP or reducing equivalents). Interestingly, when field samples were incubated under decreased O2 levels, changes in Ik and Ntot were frequently observed. In these cases, probably another substrate was limiting for nitrogenase under saturating irradiances. Hence, a combination of light-response curves at different oxygen concentrations gives important information on the physiological condition of the N2-fixing cyanobacteria in the environment.

FIG. 4.

Two theoretical nitrogenase activity-versus-irradiance curves (acetylene reduction assay [ARA]) generated with a Michaelis-Menten equation. The curve of open triangles is the curve at anoxic conditions when only light-mediated ATP generation occurs. The curve of the closed circles represents the situation that ATP originates both from oxidative phosphorylation and photophosphorylation (respiration and photosynthesis). The parameters Nm, Nd, and α were fitted by the rectangular hyperbola model. Ntot (Nm + Nd) was the same in both curves. The parameter Ik was calculated by Nm/α. Both curves gave the same Ik, but Nm and α were different. The substrate concentration is given in arbitrary units (A.U.).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the European Commission Environment RTD contract ENV4-CT97-0571 and the Dutch Science Foundation (STW) contract NNS44.3404.

Footnotes

Publication no. 3009 of NIOO-CEMO.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baly, E. C. C. 1935. The kinetics of photosynthesis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 117:218-239. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalker, B. E. 1980. Modeling light saturation curves for photosynthesis: an exponential function. J. Theor. Biol. 84:205-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fay, P. 1992. Oxygen relations of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 56:340-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallon, J. R., A. M. Evans, D. A. Jones, P. Albertano, R. Congestri, B. Bergman, K. Gundersen, K. M. Orcutt, K. von Bröckel, P. Fritsche, M. Meyerhöfer, K. Nachtigall, U. Ohlendieck, S. te Lintel Hekkert, K. Sivonen, S. Repka, L. J. Stal, and M. Staal. 2002. Maximum rates of N2 fixation and primary production are out of phase in a developing cyanobacterial bloom in the Baltic Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:1514-1521. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henley, W. J. 1993. Measurement and interpretation of photosynthetic light-response curves in algae in the context of photoinhibition and diel changes. J. Phycol. 29:729-739. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hood, R. R., N. R. Bates, D. G. Capone, and D. B. Olson. 2001. Modeling the effect of nitrogen fixation on carbon and nitrogen fluxes at BATS. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 48:1609-1648. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jassby, A. D., and T. Platt. 1976. Mathematical formulation of the relationship between photosynthesis and light for phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 21:540-547. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paerl, H. W. 1988. Nuisance phytoplankton blooms in coastal, estuarine, and inland waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33:823-847. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rippka, R., and R. Y. Stanier. 1978. The effects of anaerobiosis on nitrogenase synthesis and heterocyst development by nostocacean cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 105:83-94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staal, M., S. te Lintel-Hekkert, F. Harren, and L. J. Stal. 2001. Nitrogenase activity in cyanobacteria measured by the acetylene reduction assay: a comparison between batch incubation and on-line monitoring. Environ. Microbiol. 3:343-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stal, L. J., and A. E. Walsby. 1998. The daily integral of nitrogen fixation by planktonic cyanobacteria in the Baltic Sea. New Phytol. 139:665-671. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stal, L. J., and A. E. Walsby. 2000. Photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation in a cyanobacterial bloom in the Baltic Sea. Eur. J. Phycol. 35:97-108. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talling, J. F. 1957. Photosynthetic characteristics of some freshwater plankton diatoms in relation to underwater radiation. New Phytol. 56:29-50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsby, A. E. 1985. The permeability of heterocysts to the gases nitrogen and oxygen. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 226:345-366. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb, W. L., M. Newton, and D. Starr. 1974. Carbon dioxide exchange of Alnus rubra: a mathematical model. Oecologica 17:281-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuckermann, H., M. Staal, L. J. Stal, J. Reuss, S. te Lintel Hekkert, F. Harren, and D. Parker. 1997. On-line monitoring of nitrogenase activity in cyanobacteria by sensitive laser photoacoustic detection of ethylene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4243-4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]