Abstract

Background

The ongoing medical crisis in Korea has severely impacted the operational environment of intensive care units (ICUs), posing significant challenges to quality care for critically ill patients. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of the ongoing crisis on ICUs.

Methods

A survey was conducted in July 2024 among intensivists in charge of ICUs at institutions accredited by the Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine for critical care. The survey compared data from January 2024 (pre-crisis) and June 2024 (post-crisis) on the number ICU beds, staffing composition, working hours, and the number and roles of nurse practitioners.

Results

Among the total of 71 participating ICUs, 22 experienced a reduction in the number of operational beds, with a median decrease of six beds per unit, totaling 127 beds across these ICUs. The numbers of residents and interns decreased from an average of 2.3 to 0.1 per ICU, and the average weekly working hours of intensivists increased from 62.3 to 78.8 hours. Nurse practitioners helped fill staffing gaps, with their numbers rising from 150 to 242 across ICUs, and their scope of practice expanded accordingly.

Conclusions

The medical crisis has led to major changes in the critical care system, including staffing shortages, increased workloads, and an expanded role for nurse practitioners. This is a critical moment to foster interest and engage in active discussions aimed at creating a sustainable and resilient ICU system.

Keywords: health workforce, intensive care units, nurse practitioners, surveys and questionnaires, workload

INTRODUCTION

The intensive care unit (ICU) is designated for patients in critical condition who require the highest level of medical care. The outcome of critically ill patients admitted to the ICU is influenced by several factors, and ICU personnel is the most important among personnel, equipment, facilities, and infrastructure [1-4]. Without the meticulous attention of ICU professionals, critically ill patients are at risk of sudden deterioration, which can result in mortality. The workload of intensivists responsible for such care is intense.

The longstanding issues of low ICU reimbursement rates, excessive workload, and lack of adequate protection against medical disputes in Korea have led to a significant shortage of intensivists. In the midst of this ongoing predicament, the 2024 South Korean medical crisis occurred. The policy called Essential Medical Package in South Korea represents a comprehensive policy initiative aimed at strengthening support for essential medical services. However, without a stated fundamental challenge—including inadequate medical reimbursement rates, unfair compensation despite the risk and excessive workload, and concerns regarding excessive burden of litigation—the government unilaterally implemented a sudden increase in medical school admission quota to double. This policy has precipitated a large-scale departure of resident physicians from hospitals, resulting in significant disruptions to the healthcare system. This impact has been particularly pronounced in ICUs, where medical infrastructure is essential and insufficient. This study aims to evaluate the effects of the ongoing South Korean medical crisis on critical care systems using data from the Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine (KSCCM) survey.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/) and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (No. S2024-1327-0002), and the requirement for informed consent from the study participants was waived.

An online survey was conducted by the KSCCM in July 2024 targeting each intensivist in charge of a domestic ICU of institutions accredited by the KSCCM for critical care. In cases where an institution had multiple ICUs, each was counted independently. The survey was conducted in June 2024, with January 2024 representing the pre-crisis period and July 2024 representing the post-crisis period.

The survey items were developed by a planning committee of the KSCCM and included changes in the number of ICU beds, staffing composition, working hours, the number of intensivists who resigned, as well as the number and role of nurse practitioners (Supplementary Material 1). In the survey, a specialist referred to a board-certified doctor, while an intensivist was defined as a board-certified doctor specializing in the care of critically ill patients. A full-time ICU physician was defined as a doctor working exclusively in the ICU. A nurse practitioner was defined as one who supports or performs medical tasks delegated by a physician or who holds an advanced practice nursing certification recognized by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, allowing them to perform high-level specialized tasks, education, research, and clinical support under physician supervision. Clinical practice nurses, advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants were collectively called nurse practitioners in this survey. All items in the survey were designated as mandatory. Six respondents provided invalid answers to the question “Working hours per week,” which were treated as missing values and excluded from the denominator for each item. The scope of work of the nurse practitioners is set as the denominator for cases where there is a survey response.

The collected data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS version 27.0 software (IBM Corp.), with a significance level set at P<0.05 for all statistical tests. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the survey results, presenting frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with standard deviations for continuous variables. Differences in period were analyzed using the independent t-test.

RESULTS

Demographic and Characteristics of Participating ICUs

A total of 71 physicians in charge of an ICU participated: 37 medical ICUs, 19 surgical ICUs, and 15 mixed ICUs. The coronary care unit (n=2), emergency ICU (n=4), neurological ICU (n=4), and pediatric ICU (n=2) were classified as medical ICUs, while the cardiothoracic ICU (n=2), neurosurgical ICU (n=1), and trauma ICU (n=2) were classified as surgical ICUs. A total of 49 ICUs from tertiary hospitals and 22 ICUs from general hospitals were included. In Korea, tertiary hospitals are distinguished from general hospitals by having at least 20 medical departments with specialized doctors; providing training for medical specialists; meeting specific criteria for staffing, facilities, and equipment; maintaining a required patient composition for various disease groups; specializing in high-complexity medical procedures for severe illnesses; and being designated as such following an evaluation by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

The specialties of the participants were internal medicine (n=26), critical care (n=20), and general surgery (n=14) in descending order (Table 1). Due to the medical crisis, 22 ICUs experienced a reduction in the number of operational beds, with a median decrease of six beds per unit, totaling 127 beds across these ICUs. Forty-five ICUs maintained their number of operational beds. An increase in operational beds was observed in only four ICUs, with a total of 15 additional beds, averaging 3.8 beds per unit.

Table 1.

Demographic and structural characteristics of participating ICUs

| Parameter | No. of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of the participants’ ICU | Medical | 37 |

| Surgical | 19 | |

| Mixed | 15 | |

| Region of the participants’ hospital | Seoul | 29 |

| Gyeonggi, Incheon | 20 | |

| Gyeongsang | 12 | |

| Chungcheong | 5 | |

| Gangwon | 3 | |

| Jeolla | 2 | |

| Type of the participants’ hospital | Tertiary | 49 |

| General | 22 | |

| Specialty of participants | Internal medicine | 26 |

| Critical care medicine | 20 | |

| Surgery | 14 | |

| Cardiothoracic surgery | 2 | |

| Neurology | 2 | |

| Pediatrics | 2 | |

| Emergency medicine | 2 | |

| Family medicine | 1 | |

| Neurosurgery | 1 | |

| Traumatology | 1 | |

ICU: intensive care unit.

Change in the Staffing Composition of Full-Time ICU Physicians

When comparing the composition of full-time ICU physicians before and after the crisis, the overall median number significantly decreased from 5.0 to 3.1 (Table 2). The median number of residents and interns decreased from 2.3 to 0.1 (Figure 1). Regarding the composition of ICU physicians on in-house night duty, intensivists accounted for 46.9% in tertiary hospitals and 60.0% in general hospitals before the crisis. After the crisis, the proportion of intensivists with in-house night duty increased to 93.0% in a total of 30 ICUs, and specialists were directly covering night hours in 66 of the 71 ICUs (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the situation before and after the medical crisis

| Parameter | Before the medical crisis (as of Jan 2024) | After the medical crisis (as of Jun 2024) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of full-time ICU physicians | 5.0±3.8 | 3.1±2.3 | <0.001 |

| No. of in-house night duty for intensivists per month | 2.9±4.2 | 6.3±3.5 | <0.001 |

| Working hours of intensivists per week | 62.3±21.4 | 78.8±21.0 | <0.001 |

| Total no. of nurse practitioners per ICU | 2.1±3.3 | 3.5±4.0 | 0.034 |

Values are presented as median±standard deviation.

ICU: intensive care unit.

Figure 1.

Changes in staffing composition of full-time intensive care units (ICUs). Full-time ICU physicians decreased in number after the medical crisis.

Figure 2.

Change in the proportion of intensivists performing in-house night duty. The proportion of intensivists with in-house night duty increased from 50.7% to 93.0% in a total of 30 intensive care units (ICUs) after the medical crisis.

Number of In-House Night Duty Shifts for Intensivists per Month

The number of in-house night duties for intensivists per month also increased, with an overall significant increase of 3.4 times per month, resulting in 6.3 times as of June 2024 (Table 2, Figure 3). Night shifts in tertiary hospitals increased from 2.2 to 6.2 times, and general hospitals increased from 4.7 to 6.4 times.

Figure 3.

Change in the number of in-house night duties for intensivists per month. The number of in-house night duties for intensivists per month of specialists also increased due to the medical crisis. ICU: intensive care unit.

Working Hours of Intensivists per Week

The median weekly working hours of intensivists significantly increased by 16.5 hours from 62.3 hours before the crisis to 78.8 hours after the crisis (Table 2). When weekly working hours were divided into 10-hour groups, the number of intensivists working more than 80 hours per week increased after the crisis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Change in the working hours of intensivists per week. The weekly working hours of intensivists also increased, with an increased number of intensivists working more than 80 hours.

Number of Intensivists Who Resigned

The number of intensivists who resigned from 71 ICUs as 11 (7.4%) as of January 2024 (n=149). However, the survey did not include whether these 11 had stopped working as intensivists or had moved to other institutions to continue working as intensivists.

Expansion of the Number and Role of Nurse Practitioners

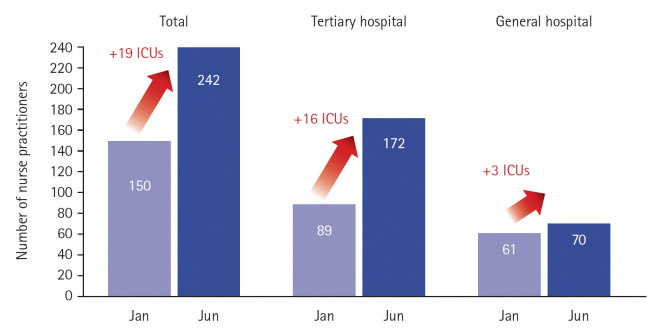

The number of ICUs with nurse practitioners has also increased due to the shortage of residents and interns. The number of ICUs with nurse practitioners increased from 40 ICUs in January to 59 ICUs in June 2024 (Figure 5). The median number of nurse practitioners per ICU increased (Table 3), and the overall number of nurse practitioners in the 71 ICUs also increased from 150 to 242 due to the crisis.

Figure 5.

Increase of the number of intensive care units (ICUs) with nurse practitioners. The number of nurse practitioners and number of ICUs with nurse practitioners has also increased.

Table 3.

Changes in the scope of work of the nurse practitioners before and after medical crisis

| Variable | Performs independently |

Assists in performing |

Does not perform |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Blood sampling via arterial line | 27 (65.9) | 40 (70.2) | 6 (14.6) | 8 (14.0) | 8 (19.5) | 9 (15.8) |

| Arterial puncture or line insertion | 10 (25.0) | 21 (37.5) | 9 (22.5) | 16.0 (28.6) | 21 (52.5) | 19 (33.9) |

| Central line insertion | 0 | 0 | 9 (22.5) | 16 (28.6) | 21 (52.5) | 19 (33.9) |

| PICC insertion | 2 (5.0) | 2 (3.6) | 14 (25.0) | 23 (41.8) | 28 (70.0) | 30 (54.5) |

| Central line removal | 12 (30.8) | 36 (63.2) | 9 (23.1) | 13 (22.8) | 18 (46.2) | 8 (14.0) |

| Intubation | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 19 (47.5) | 29 (51.8) | 20 (50.0) | 27 (48.2) |

| Extubation | 2 (5.0) | 7 (12.5) | 17 (42.5) | 27 (48.2) | 21 (52.5) | 22 (39.3) |

| CPR | 5 (12.5) | 13 (22.8) | 31 (77.5) | 40 (70.2) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (7.0) |

| Emergency medication administration | 12 (30.0) | 21 (36.8) | 20 (50.0) | 30 (52.6) | 8 (20.0) | 6 (10.5) |

| Delegated prescription | 8 (20.5) | 22 (38.6) | 14 (35.9) | 22 (38.6) | 17 (43.6) | 13 (22.8) |

| Drafting or revising a medical record | 8 (20.0) | 14 (25.5) | 8 (20.0) | 17 (30.9) | 24 (60.0) | 24 (4.6) |

| Issue of various medical fees | 9 (22.5) | 19 (34.5) | 11 (27.5) | 11 (20.0) | 20 (50.0) | 25 (45.5) |

| Surgical site dressing | 13 (32.5) | 29 (50.9) | 13 (32.5) | 13 (22.8) | 14 (35.0) | 15 (26.3) |

| Tracheostomy site dressing | 20 (50.0) | 40 (70.2) | 9 (22.5) | 8 (14.0) | 11 (27.5) | 9 (15.8) |

| Tracheostomy tube change or removal | 2 (5.0) | 10 (17.9) | 13 (32.5) | 22 (39.3) | 25 (62.5) | 24 (42.9) |

| Vacuum-assisted dressing | 15 (37.5) | 26 (47.3) | 17 (42.5) | 19 (34.5) | 8 (20.0) | 10 (18.2) |

| Skin suture using stapler | 2 (5.0) | 3 (5.5) | 11 (27.5) | 15 (27.3) | 27 (67.5) | 37 (67.3) |

| Determining whether to stitch out | 3 (7.5) | 8 (14.5) | 8 (20.0) | 12 (21.8) | 29 (72.5) | 35 (63.6) |

| Levin tube insertion | 13 (32.5) | 37 (64.9) | 9 (22.5) | 10 (17.5) | 18 (45.0) | 10 (17.5) |

| CSF tapping | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 7 (17.5) | 14 (25.0) | 32 (80.0) | 42 (75.0) |

| Ascites tapping | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 6 (15.0) | 12 (21.4) | 33 (82.5) | 44 (78.6) |

| Trans-tracheal aspiration | 18 (45.0) | 31 (55.4) | 9 (22.5) | 8 (14.3) | 13 (32.5) | 17 (30.4) |

| Cast or splint application | 1 (2.5) | 3 (5.5) | 8 (20.0) | 11 (20.0) | 31 (77.5) | 41 (74.5) |

Values are presented as number (%), with the percentages in parentheses indicating the proportion of each item based on the total number of respondents.

PICC: peripherally inserted central line; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid.

The scope of the work of nurse practitioners has also changed since the crisis. When comparing the work performed by nurse practitioners in each ICU before and after the crisis, the independently performed procedures that showed the largest increase in frequency were central line removal, Levin tube insertion, and tracheostomy cannula dressing. Among procedures to assist doctors, the most common were peripherally inserted central line insertion, central line insertion, and drafting or revising a medical record (Table 2).

Expert Recommendations for Optimizing the Working Environment for Intensivists

Suggestions from the survey participants to improve ICU operations can be categorized into financial, working conditions, and staffing aspects. Participants emphasized increasing reimbursement fees for ICU-related procedures and management performed by intensivists and suggested that procedures performed in the ICU should have distinct billing and coding systems. To enhance working conditions, recommendations included direct compensation for intensivists, objective salary criteria, increasing on-call fees, enforcing labor laws for overtime and night shifts, limiting continuous working hours, implementing legal safety measures, and introducing tele-monitoring. Expanding and better supporting ICU nurse practitioners through guidelines, education, and financial incentives was also suggested. Additional recommendations included reporting fraudulent fee claims and requesting the KSCCM to strengthen the political influence of academic societies and host academic events online.

DISCUSSION

It is well-established that the presence of an intensivist is one of the most important factors determining the quality of care in the ICU [4-9]. A formal intensivist certification system was established in 2009 in Korea, and has shown progress in operation of ICUs in Korea [4]. Continuous 24/7 coverage has been associated with improved processes of care, greater family satisfaction, and closer supervision of trainees [10,11]. There has traditionally been a heavy burden on residents to provide 24-hour intensive care in Korea.

The 2024 medical crisis revealed the underlying vulnerabilities of Korea’s critical care healthcare system, which had been barely sustained. This situation highlighted the absence of essential medical services, which has since emerged as a growing socio-medical issue. According to this survey, the medical crisis caused a drastic reduction in ICU personnel and a significant increase in intensivists' workloads. Average weekly working hours and in-house night duties increased substantially. As a countermeasure, the number and roles of nurse practitioners were expanded. These findings suggest that the ongoing crisis is being managed by overburdening intensivists and expansion of nurse practitioners. According to the 2023 Critical Care Adequacy Evaluation conducted by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, a single intensivist is responsible for managing an average of 22 patients [12]. However, the investigation took place when residents were still working, suggesting that the workload among intensivists has increased even further during this ongoing crisis.

Despite difficult situations driven by political issues, ICU treatment must continue to maximize effective and safe patient care. There is a known correlation between ICU physician staffing models and patient safety [7]. Since ICU staffing models are myriad and based on several factors including local culture and resources [13], there is a need for discussion and policy research on the following: intensivist-patient ratios; total number of intensivist shifts per month; intensivist ICU presence versus call from home; number of night and weekend shifts per month, and other attending physician non-ICU clinical responsibilities during ICU shifts according to domestic ICU size, type, and teaching hospital status under the leadership of the KSCCM.

In Korea, particularly in ICUs, nurse practitioners had not been allowed to perform tasks equivalent to those of physicians. However, with the enactment of the Nursing Act in August 2024, they are now permitted to carry out such tasks under supervision and guidance. Nurse practitioners have been reported to positively impact adherence to clinical guidelines, increase revenue generation, reduce hospital and ICU length of stays, and decrease complication rates [14-16], although there is a low level of evidence, with only two randomized control trials. To mitigate the potential adverse effects of the rapid expansion of their numbers and roles, the KSCCM should support the development of an educational curriculum specifically for ICU nurse practitioners. At the hospital level, the establishment of nurse-driven protocols also could be beneficial in enhancing patient care and ensuring effective integration of nurse practitioners into the ICU team. Additionally, there are alternatives such as using less resource-intensive strategies like standardized protocols and use of telemedicine [17]. Additionally, public and physician education on the appropriate use of ICU beds [10] also might be helpful in the current workforce shortage.

There were possible responses in our survey to increase or create reimbursement fees related to ICU management and to offer this as fair compensation for the risk and heavy workload of intensivists. As pointed out in previous studies, suggestions to increase and maintain the intensivist workforce will only be effective if the work-life balance, work satisfaction, and compensation deficiencies are addressed [17].

The present study has several limitations. First, this survey was conducted through voluntary participation, and the results do not represent every ICU in Korea. Second, the reasons intensivists resigned their positions were not included in the survey. Third, this study did not incorporate an objective evaluation of the quality associated with the roles of nurse practitioners. Fourth, since this study is based on a questionnaire, the results could have been affected by respondents' subjective judgment.

In conclusion, the absence of essential healthcare services, particularly in the context of infections and social disasters, poses a fundamental threat to the integrity of healthcare systems. Ensuring the resilience of these services must be a priority. Korea’s critical care system, which has yet to improve since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, has been further strained by the recent medical crisis, exposing persistent structural vulnerabilities. This represents one of the most significant challenges to the country’s healthcare system, despite its longstanding reputation for medical excellence. Now is a critical moment to foster interest and engage in active discussions aimed at creating a sustainable and resilient ICU system.

KEY MESSAGES

▪ Significant changes in intensive care units (ICUs) staffing and workload were observed as the medical crisis led to a drastic reduction in ICU personnel and an increased workload for intensivists; average weekly working hours for intensivists increased significantly (by 16.5 hours), and the number of in-house night duties increased (by 3.4 times per month).

▪ The increased number and expanded role of nurse practitioners, with a larger number performing independent procedures in the ICU, emphasize the need for enhanced training and integration into ICU teams.

▪ A call for sustainable ICU operations includes recommendations such as optimizing workloads, fair compensation, standardized protocols, and policy research on staffing models.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to sincerely thank the planning committee members of the Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine for their invaluable contributions to the design and execution of this survey. We also express our deep appreciation to the intensivists who participated in this survey, despite the challenging circumstances.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: YRC, BGK, SKH. Methodology: YRC, BGK, SKH. Formal analysis: YRC. Data curation: YRC, JHC, JC, TSH, BGK, EK, IKK, DHL, SKH. Visualization: YRC. Project administration: YRC, SKH. Funding acquisition: JHC, SKH. Writing – original draft: YRC. Writing – review & editing: YRC, JHC, JC, TSH, BGK, EK, IKK, DHL, SKH. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4266/acc.000575.

Survey items

REFERENCES

- 1.Cavallazzi R, Marik PE, Hirani A, Pachinburavan M, Vasu TS, Leiby BE. Association between time of admission to the ICU and mortality: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138:68–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weled BJ, Adzhigirey LA, Hodgman TM, Brilli RJ, Spevetz A, Kline AM, et al. Critical care delivery: the importance of process of care and ICU structure to improved outcomes: an update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force on Models of Critical Care. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1520–5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon JE, Roh DE, Kim YH. Effects of the presence of a pediatric intensivist on treatment in the pediatric intensive care unit. Acute Crit Care. 2020;35:87–92. doi: 10.4266/acc.2019.00752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Suh GY. Intensivist physician staffing in intensive care units. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2013;28:1–9. doi: 10.4266/kjccm.2013.28.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins TL, McGee WT, Steingrub JS, Rapoport J, Lemeshow S, Teres D. Early indicators of prolonged intensive care unit stay: impact of illness severity, physician staffing, and pre-intensive care unit length of stay. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:45–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rollins G. ICU care management by intensivists reduces mortality and length of stay. Rep Med Guidel Outcomes Res. 2002;13:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gajic O, Afessa B. Physician staffing models and patient safety in the ICU. Chest. 2009;135:1038–44. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;288:2151–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Kim JH, You KH, Han WH. Effects of closed- versus open-system intensive care units on mortality rates in patients with cancer requiring emergent surgical intervention for acute abdominal complications: a single-center retrospective study in Korea. Acute Crit Care. 2024;39:554–64. doi: 10.4266/acc.2024.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern NA, Pastores SM, Oropello JM, Kvetan V. Critical care medicine in the United States: addressing the intensivist shortage and image of the specialty. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2754–61. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a6fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, Jolly B. AMEE Guide No. 27: effective educational and clinical supervision. Med Teach. 2007;29:2–19. doi: 10.1080/01421590701210907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evaluation Operation Office of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service . 2023 Critical care adequacy evaluation. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pastores SM, Kvetan V, Coopersmith CM, Farmer JC, Sessler C, Christman JW, et al. Workforce, workload, and burnout among intensivists and advanced practice providers: a narrative review. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:550–7. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinpell RM, Ely EW, Grabenkort R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2888–97. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e318186ba8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapu AN, Kleinpell R, Pilon B. Quality and financial impact of adding nurse practitioners to inpatient care teams. J Nurs Adm. 2014;44:87–96. doi: 10.1097/nna.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillard JN, Szoke A, Hoff WS, Wainwright GA, Stehly CD, Toedter LJ. Utilization of PAs and NPs at a level I trauma center: effects on outcomes. JAAPA. 2011;24:34, 40-3. doi: 10.1097/01720610-201107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park CM, Chun HK, Lee DS, Jeon K, Suh GY, Jeong JC. Impact of a surgical intensivist on the clinical outcomes of patients admitted to a surgical intensive care unit. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;86:319–24. doi: 10.4174/astr.2014.86.6.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Survey items