ABSTRACT

Introduction

The locus coeruleus (LC) is a compact nucleus of noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem. Despite its relatively small size, the LC has widespread axonal connections and serves as the primary source of noradrenaline (NA) throughout the central nervous system. The LC‐NA system plays a critical role in regulating cognitive and physiological processes, and its dysfunction has been implicated in various neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Results

This narrative review explores the anatomy, neurochemistry, and function of the LC‐NA system in both the healthy and diseased brain. We first provide a detailed overview of LC connectivity, highlighting its afferent and efferent projections and their implications for brain‐wide noradrenaline modulation. Next, we discuss the neurochemical properties of noradrenaline, emphasizing its synthesis, release dynamics, and receptor interactions. The core of this review focuses on the functional roles of the LC‐NA system, systematically addressing each function first in the healthy brain and then discussing associated disorders. Specifically, we explore the role of LC‐NA signaling in attention and arousal, stress, emotion and pain, memory, motion, and neuroprotection, followed by discussions on psychiatric disorders, cognitive dysfunctions, and neurodegenerative diseases that arise from its dysregulation. Lastly, we examine the involvement of the LC in epilepsy, highlighting how alterations in noradrenaline signaling contribute to seizure susceptibility and propagation.

Conclusion

By integrating anatomical, neurochemical, and functional perspectives, this review provides a comprehensive understanding of the LC‐NA system's role in brain function and its relevance as a therapeutic target in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: epilepsy, locus coeruleus, neurological disorders, neurophysiology, noradrenaline

The locus coeruleus (LC) is a small brainstem nucleus that serves as the main source of noradrenaline for the central nervous system, influencing a wide range of cognitive and physiological processes. By integrating anatomical, neurochemical, and functional perspectives, this review provides a comprehensive understanding of the LC‐NA system's role in brain function and its relevance as a therapeutic target in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

1. Anatomy

The locus coeruleus (LC) is a compact nucleus of noradrenergic neurons situated bilaterally within the pontine brainstem, positioned ventrally to the cerebellum and adjacent to the fourth ventricle. The name locus coeruleus, meaning “blue spot” in Latin, reflects the pigmented appearance of its neuromelanin‐containing neurons. Despite its relatively small size, the LC comprises approximately 1500 neurons per nucleus in rodents and between 10,000 to 15,000 neurons in humans. These neurons exhibit extensive axonal arborization, serving as the principal source of noradrenaline (NA) throughout the central nervous system (CNS) [1, 2, 3].

The subcoeruleus (SubC), also known as the A7 noradrenergic cell group, is situated adjacent to but extending well beyond the boundaries of the LC. Located ventrally to the LC, SubC neurons are less densely packed and display a more diffuse distribution. In addition, dendritic processes from LC neurons extend into the pericoeruleus (peri‐LC) region, a peri‐nuclear structure that envelops the LC [4].

The cellular composition of the LC is heterogeneous. Noradrenergic neurons within the LC can be categorized into large multipolar neurons (~35 μm in diameter) and smaller fusiform neurons (~20 μm in diameter). These subtypes exhibit distinct distributions along the dorsoventral axis, with fusiform neurons predominantly localized in the dorsal LC and multipolar neurons concentrated in the ventral LC. Structurally, the dorsal and ventral subdivisions of the LC are separated by interposed cells of the medial vestibular nucleus [5].

Numerous studies have characterized the connectivity of the LC in rodents; however, direct investigations of LC projections in humans remain limited due to methodological constraints. The following sections will examine the afferent and efferent projections of the LC, with the majority of current knowledge derived from rodent tract‐tracing studies.

1.1. Afferent Projections

LC neurons receive extensive afferent projections from numerous brain regions, with retrograde rabies tracing studies identifying up to 111 distinct sources. These studies also reveal that individual LC‐NA neurons integrate signals from 9 to 15 different regions and that neurons projecting to functionally diverse targets generally receive similar afferent input. This organizational framework highlights the LC‐NA system's crucial role in integrating multimodal information and broadly modulating brain states and behavior [5, 6].

Among the key afferents is the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), the principal relay station of vagal sensory input, which influences the LC indirectly. The vagus nerve projects bilaterally to the NTS, but the LC receives the strongest projections from the unilateral NTS [7, 8]. These indirect projections occur via excitatory glutamatergic input from the nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi) and inhibitory GABAergic input from the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (PrH). Additionally, the LC is reciprocally connected, meaning it receives afferent input from and sends efferent input to the dorsal raphe nucleus, forming an important serotonergic regulatory circuit that modulates responses to afferent sensory signals. These three pathways are particularly relevant in the seizure‐suppressing effects of vagus nerve stimulation, an effect largely attributed to LC‐mediated NA release [9].

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) provides the most substantial excitatory input to the LC, with additional glutamatergic projections from the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices. These pathways establish a functional link between the LC‐NA system and higher‐order cognitive and affective processing. GABAergic interneurons within the peri‐LC region and the SubC form local inhibitory circuits that modulate LC activity. Through this inhibitory modulation, they regulate LC excitability and prevent excessive activation [4, 10, 11].

Afferent projections from regions involved in arousal and stress regulation also converge on the LC. Notably, corticotropin‐releasing hormone (CRH) projections from the PGi and Barrington's nucleus are thought to relay signals related to internal physiological stress, including visceral, parasympathetic, and neuroendocrine responses. In contrast, CRH projections from the central nucleus of the amygdala are primarily associated with psychological and emotional responses to stress, conveying information about environmental, external threats through cognitive and affective appraisal mechanisms [1, 12, 13, 14, 15].

In addition to its role in cognitive and autonomic regulation, the LC is deeply involved in pain modulation and antinociception. Excitatory input from the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG) plays a crucial role in opioid‐induced analgesia, in conjunction with projections from the medial rostral ventrolateral medulla. These inputs disinhibit LC‐NA neurons, thereby enhancing NA release in the spinal cord, a key mechanism underlying endogenous analgesic processes [16].

The extensive network of LC afferents underscores its function as a convergence hub for multiple physiological and behavioral regulatory systems. Excitatory inputs from structures such as the PGi and PAG allow the LC to respond dynamically to sensory and pain‐related stimuli, while inhibitory afferents from the PrH and peri‐LC counterbalance excitation to maintain homeostatic control. This intricate afferent connectivity enables the LC to modulate arousal, attention, autonomic function, and stress adaptation, reinforcing its central role in neurobehavioral regulation [1, 3, 9].

1.2. Efferent Projections

The LC exerts its extensive modulatory influence through widespread axonal projections that innervate nearly the entire CNS. Major targets include the neocortex, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, cerebellum, and spinal cord, reflecting the LC's role in regulating diverse neural functions. Many of these connections are reciprocal. In contrast, certain structures, including the striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and nucleus accumbens, receive little to no direct noradrenergic innervation [1, 2, 3, 5].

Although traditionally regarded as a functionally uniform system, recent evidence indicates a degree of topographical organization within LC efferent projections, with distinct neuronal populations targeting specific CNS regions. Differential projection patterns can be observed along the dorsal‐ventral axis. Dorsal LC neurons primarily project to forebrain structures, including the hippocampus and septum, while ventral LC neurons predominantly innervate the cerebellum and spinal cord. Amygdala‐ and cortex‐projecting neurons are interspersed throughout this axis, though dorsal LC neurons preferentially target the occipital cortex, whereas ventral LC neurons project mainly to the prefrontal cortex. Along the anterior–posterior axis, hypothalamus‐projecting neurons are located anteriorly, while thalamus‐projecting neurons are situated more posteriorly. This organization also extends to laterality, with cortical and hippocampal projections being predominantly ipsilateral (> 95%), whereas subcortical structures, such as the cerebellum and spinal cord, receive bilateral LC innervation [1, 5, 6].

Moreover, LC neurons frequently send collateral projections to multiple functionally related targets, suggesting a role in coordinating activity across interconnected regions. For instance, LC neurons projecting to the trigeminal somatosensory cortex often co‐innervate the trigeminal somatosensory thalamus, reinforcing modality‐specific processing. This implies that activation of a subset of LC neurons may simultaneously release NA in functionally linked circuits; thereby synchronizing activity within a particular sensory, cognitive, or motor domain.

Additionally, individual LC neurons exhibit divergent projections, with some neurons simultaneously innervating both the hippocampus and cortex or both the thalamus and spinal cord, further expanding the integrative capacity of the LC‐NA system [1, 17].

In summary, while the LC is defined by its extensive and diffuse noradrenergic projections, its complex topographical organization enables precise modulation of neural network dynamics. This structural framework supports the LC's essential role in regulating arousal, cognitive processes, sensorimotor functions, and adaptive behavioral responses [5, 6].

2. Neurochemistry

2.1. Noradrenaline and Adrenergic Receptors

Noradrenaline (NA) is the primary neurotransmitter utilized by the LC efferent pathway. NA synthesis starts with the enzymatic conversion of the amino acid tyrosine into L‐dihydroxyphenylalanine (L‐DOPA) by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate‐limiting step in catecholamine synthesis. L‐DOPA is subsequently decarboxylated to dopamine by DOPA decarboxylase (DDC). Once synthesized, dopamine is transported into synaptic vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT), where it undergoes conversion to NA by dopamine β‐hydroxylase (DBH) inside the vesicles. The actions of NA in the synaptic cleft are terminated primarily through reuptake by the selective NA transporter (NAT), followed by enzymatic degradation via monoamine oxidase A (MOA‐A) or catechol‐O‐methyltransferase (COMT) (Figure 1) [3].

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of noradrenaline (NA) transmission. Tyrosine is converted to L‐DOPA by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which is then decarboxylated by DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) to form dopamine (DA). DA is transported into synaptic vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT), where dopamine β‐hydroxylase (DBH) converts it to NA. Upon stimulation, NA is released into the synaptic cleft and binds postsynaptically to the α1, α2 or β adrenergic receptors coupled to different G‐proteins, Gq, Gi, Gs, respectively. This mediates downstream signaling pathways involving phospholipase C (PLC) and adenylyl cyclase (AC). Released NA can also bind to presynaptic autoreceptors to inhibit further release. NA is cleared from the synaptic cleft via reuptake or degraded by catechol‐O‐methyltransferase (COMT) and monoamine oxidase A (MAO‐A).

NA interacts with three distinct families of G‐protein‐coupled adrenergic receptors (ARs): α1‐, α2‐, and β‐adrenergic receptors (β1–β3), each comprising multiple subtypes. In general, α1‐ARs are linked to Gq proteins, α2‐ARs couple to Gi proteins, and β‐ARs are associated with Gs proteins (Figure 1). The physiological effects of NA are dictated by the specific AR subtype, the local concentration of NA, and whether the receptor is pre‐ or postsynaptically localized [3, 18].

The α1‐ARs are present postsynaptically and activate the Gq, phospholipase C (PLC), inositol triphosphate (IP3), protein kinase C (PKC) pathway, generally exerting an excitatory effect. They are highly expressed in the thalamus and neocortex, where they modulate both neuronal and interneuron activity. Their presence on interneurons suggests they can also enhance inhibitory transmission by increasing GABAergic firing [18, 19].

The α2‐ARs are located pre‐ and postsynaptically and couple to Gi proteins, inhibiting adenylyl cyclase (AC), activating K+ currents, and suppressing presynaptic calcium channels, leading to reduced excitability and neurotransmitter release. Notably, α2‐ARs have the highest affinity for NA, allowing them to respond even at low NA concentrations [19]. These receptors also function as autoreceptors on noradrenergic neurons, regulating their activity at multiple levels, both locally within the LC and distally in its projection areas. Locally, NA released from LC neurons binds to α2‐ARs located on the somata and dendrites of LC neurons, initiating a Gi‐mediated signaling cascade that activates K+ channels, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization and decreased neuronal firing. This serves as a negative feedback mechanism to limit excessive LC activity during periods of heightened NA release, such as stress. Disruption of this autoregulatory pathway may lead to persistent LC hyperactivity, a feature implicated in disorders such as epilepsy and attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In projection areas, α2‐ARs expressed at noradrenergic axon terminals inhibit NA release by reducing Ca2+ influx through presynaptic voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels, thereby modulating synaptic transmission locally [20, 21, 22, 23].

β‐ARs are found postsynaptically and are linked to Gs proteins, stimulating AC and increasing cAMP, which enhances synaptic excitability and plasticity. They are expressed in both cortical and subcortical neurons, including GABAergic inhibitory interneurons located in regions such as the PFC, hippocampus, and amygdala [24, 25, 26]. Unlike α2‐ARs, β‐ARs have the lowest affinity for NA, requiring high NA release for activation [19, 27].

Noradrenergic transmission in the CNS exhibits a unique mode of neurotransmitter release. While classical neurotransmission predominantly involves synaptic release, a significant proportion of NA is discharged into the extracellular space, acting through volume transmission.

Anatomical studies reveal that only approximately 20% of noradrenergic varicosities form conventional synaptic contacts with neurons; whereas the majority preferentially interface with astrocytic processes and release NA into the extracellular environment [28, 29].

Volume transmission operates in parallel with synaptic transmission, allowing NA to diffuse across broader extracellular spaces and influence neuronal and glial populations. Astrocytes, which express ARs, play a critical role in mediating the effects of NA. Activation of α1‐ARs in astrocytes elicits robust intracellular calcium transients, whereas β‐AR stimulation enhances cAMP formation [28, 30]. Furthermore, activation of α1‐ARs has been found to enhance GABA release across multiple brain regions, while also promoting glutamate uptake by astrocytes. In contrast, β‐AR activation increases astrocytic GABA uptake, leading to a reduction in inhibitory GABAergic signaling. Astrocytes are therefore in a key position to modulate many of the effects of NA on neurons and interneurons [28, 31].

2.2. Neuropeptides and Dopamine

The LC is primarily recognized for its noradrenergic neurons, yet these neurons also co‐express various neuropeptides, including galanin, neuropeptide Y (NPY), vasopressin, somatostatin, enkephalin, neurotensin, and CRH. Approximately 80% of LC neurons co‐express galanin alongside NA, whereas NPY is present in a smaller subset (~20%). These neuropeptide‐containing efferents exhibit topographic organization, with galanin‐positive neurons predominantly localized in the dorsal and central LC regions, while NPY‐positive neurons are restricted to the dorsal LC. Functionally, galanin and NPY modulate LC activity by exerting inhibitory effects through the GAL1 and Y2 receptors on LC neurons, respectively, thereby contributing to stress resilience [1, 5, 32, 33]. Vasopressin exerts bidirectional effects on LC neuron excitability through vasopressin 1b receptors, which are expressed on both noradrenergic and non‐noradrenergic neurons, whereas vasopressin 1a receptors are limited to noradrenergic cells [34]. Somatostatin, enkephalin, and neurotensin are each found in subpopulations of LC neurons and have been shown to modulate neuronal activity, primarily through inhibitory mechanisms, although neurotensin can elicit both excitatory and inhibitory effects depending on the neuronal subtype [35, 36]. Enkephalin, in particular, mediates opioid‐dependent inhibition of LC firing, thereby influencing stress and pain processing [37, 38]. CRH is primarily delivered to the LC via afferent projections and enhances LC activity during stress, contributing to heightened arousal and anxiety‐like behaviors [15]. However, in contrast to galanin and NPY, detailed quantitative data on the proportion of LC neurons co‐expressing somatostatin, enkephalin, neurotensin, and CRH, as well as their precise topographic distribution within the nucleus, remain limited.

In addition to NA, LC neurons also release dopamine (DA), which has been detected in cortical and hippocampal projections. Activation of the LC leads to the simultaneous release of DA and NA in the cerebral cortex, suggesting that a portion of cortical DA originates from noradrenergic terminals rather than solely from midbrain dopaminergic neurons. The temporal dynamics of DA and NA release indicate distinct yet interrelated regulatory mechanisms, with α2‐ARs playing a crucial role in modulating their extracellular levels. Agonists of the α2‐AR, such as clonidine, suppress the release of both neurotransmitters, whereas antagonists like idazoxan enhance their availability [39]. Recent evidence further demonstrates that DA released in the dorsal hippocampus originates specifically from LC‐NA neurons rather than the ventral tegmental area (VTA). This LC‐derived DA signal is critical for selective attention and spatial learning, underscoring the broader cognitive implications of LC neurotransmission and its role in neuromodulation [40].

3. Physiology and Function

3.1. Techniques to Study LC Physiology and Function

Investigating the physiology and function of the LC presents challenges due to its small size and location deep in the brainstem. However, a combination of invasive and non‐invasive methodologies has been developed to study its structure and function in both rodents and humans.

Electrophysiological recordings have been fundamental in characterizing the activity of LC neurons in rodent models. Traditional techniques, including extracellular recordings with chronically implanted electrodes and in vitro slice recordings, have enabled the measurement of local field potentials and membrane dynamics within the LC. However, due to the LC's compact anatomical structure, these methods have typically allowed the insertion of only a single electrode, limiting recordings to multi‐unit activity or, at best, a small number of simultaneously recorded single units [41]. Recent advancements in high‐density silicon probe technology have significantly expanded the capabilities of electrophysiological investigations. These probes facilitate large‐scale, high‐resolution recordings from multiple LC neurons simultaneously, enabling detailed analysis of both tonic and phasic firing patterns, as well as the synchronous activity of distinct neuronal ensembles. This has provided critical insights into the spatial and functional organization of the LC and its role in neuromodulatory processes [41, 42, 43].

In parallel, pupillometry, the measurement of pupil diameter over time, has emerged as a powerful, non‐invasive proxy for LC activity in both humans and animal models. While pupil size has traditionally been associated with the autonomic response to light, it is now recognized as a sensitive marker of arousal, cognitive effort, and noradrenergic activity [44].

The LC modulates pupil diameter via projections to brain regions such as the Edinger‐Westphal nucleus and sympathetic circuits controlling the dilator pupillae muscle. Phasic bursts of LC activity in response to salient or novel stimuli typically evoke transient pupil dilations; whereas tonic LC activity correlates with baseline pupil diameter [44, 45]. Importantly, aberrant pupil dynamics have been linked to several neurological conditions, including Alzheimer's disease and autism spectrum disorder, underscoring the clinical value of pupillometry for assessing LC function [46, 47].

The development of neuromodulation techniques such as optogenetics and chemogenetics has enabled precise, cell‐type‐specific manipulation of LC neurons in rodents. Optogenetics allows for millisecond‐scale activation or inhibition of LC activity via light‐sensitive ion channels or pumps, while chemogenetics utilizes engineered receptors selectively activated by pharmacologically inert ligands [48, 49]. By targeting these tools to noradrenergic neurons using specific promoters, researchers can modulate LC activity to study its effects on behavior, arousal, and cognition [50]. These techniques also facilitate anatomical tracing of LC projections through the use of retrograde labeling methods [51].

Complementary to these approaches, fiber photometry combined with genetically encoded sensors has become a widely used method for monitoring dynamic changes in LC activity and NA release in vivo in rodents. This technique involves the use of fluorescent sensors that exhibit conformational changes and consequent fluorescence shifts upon ligand binding [52, 53]. Calcium indicators such as the GCaMP family are commonly used to monitor LC neuronal activity, with fluorescence increasing upon Ca2+ binding to calmodulin [54]. To measure NA release directly, sensors such as GRABNE2m and nLight provide sub‐second resolution, enabling real‐time monitoring of NA dynamics [55, 56]. These sensing technologies are often used in combination with optogenetic or chemogenetic modulation to establish causal relationships between LC activity and behavioral or physiological outcomes.

In human studies, non‐invasive imaging modalities have been developed to assess the LC's structure and function. Neuromelanin‐sensitive magnetic resonance imaging (NM‐MRI) exploits the paramagnetic properties of neuromelanin, a pigment highly concentrated in LC neurons, giving rise to its designation as the “blue spot,” to visualize the LC in vivo. NM‐MRI signal intensity correlates with LC neuron density in postmortem analyses and has been used to study age‐related decline and degeneration in disorders such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease [57, 58]. Functional MRI (fMRI) further enables the investigation of LC activity through blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) signals during cognitive and emotional tasks. Despite the challenges posed by the LC's small size and deep brain location, advances in imaging resolution and analysis have facilitated the reliable detection of LC‐related activation [59]. When combined with pupillometry, fMRI provides a powerful, multimodal framework for studying the LC's role in attention, arousal, and other cognitive processes [46, 60].

Finally, postmortem histological analyses remain the gold standard for assessing LC morphology and pathology. These methods allow direct visualization of LC neurons, their neuromelanin content, and associated neuropathological features in various disease states [58].

In summary, a diverse array of invasive and non‐invasive methodologies, ranging from electrophysiology and fiber photometry to neuromodulation, pupillometry, and advanced imaging, has greatly expanded our understanding of the structural and functional properties of the LC in both animal models and humans.

3.2. Activity of LC Neurons

LC neurons exhibit two distinct patterns of activity: tonic and phasic firing. Tonic activity is characterized by a slow, highly regular spontaneous firing rate, typically ranging from 0 to 5 Hz, with broad action potential waveforms (1–2 ms). This activity varies across sleep–wake states, increasing during wakefulness, decreasing during slow‐wave sleep, and becoming nearly silent during rapid‐eye movement (REM) sleep, highlighting the LC's role in regulating arousal and the sleep–wake cycle. Elevated tonic activity is associated with exploratory behavior, heightened stress, and increased distractibility [1, 12].

In contrast, phasic activity consists of brief bursts of firing at 10–15 Hz, followed by a suppression period lasting 300–700 ms due to autoinhibition. This activity pattern can be internally triggered by decision completion or externally evoked by unexpected, intense, or salient stimuli, such as noxious stimuli. Phasic firing facilitates a task‐specific state of focused attention, enhancing cognitive engagement in response to significant environmental cues [1].

Phasic discharge is modulated by tonic activity levels, following an inverse‐U relationship. Phasic responses are attenuated at both low and high tonic firing rates, suggesting that optimal behavioral performance occurs at intermediate levels of tonic activity [27]. This relationship is particularly significant given that extracellular NA release is linearly correlated with tonic discharge rates. Small shifts in LC firing patterns can therefore produce substantial changes in NA efflux. For example, prolonged burst‐like LC stimulation induces greater NA release than tonic stimulation [61]. This effect was further confirmed using a GRABNE1m biosensor in the hippocampus, which demonstrated that a 15 Hz burst stimulation elicited a higher NA release compared to tonic 3 Hz stimulation [62]. Similarly, neuropeptide co‐localization studies indicate that the release of galanin and neurotensin occurs exclusively during phasic, but not tonic, activity [1].

Electrophysiological studies suggest that LC‐NA fibers are primarily thin, unmyelinated axons, as reflected by their slow conduction velocities (0.2–0.86 m/s). Additionally, conduction velocity decreases with prolonged activity, with a maximal transmission efficiency observed at 20 Hz [63].

Historically, multi‐unit recordings and slice electrophysiology suggested that LC neurons fire in a highly synchronized manner, resulting in global NA release [1]. However, recent findings by Totah et al. challenge this assumption, revealing that LC neurons do not fire as a fully synchronized unit, but rather as dynamic ensembles. While small groups of LC neurons exhibit brief, spatially restricted synchrony, this coordination does not extend beyond neuron pairs. Cross‐correlogram analysis identified synchrony peaks at 10–70 ms delays, likely driven by shared synaptic inputs from extra‐LC sources and lateral inhibition within the LC [41].

At a broader timescale (2–10 s), LC neurons exhibit in‐phase and out‐of‐phase oscillations, meaning that some neurons within an ensemble fire synchronously to release NA to their target regions, while others remain suppressed. Given that individual LC neurons often project to single forebrain regions, this results in a spatiotemporal segregation of NA release, where some brain areas receive high NA levels, while others experience simultaneous suppression. These findings suggest that, rather than acting as a homogenous unit, LC neurons function as coordinated but selective ensembles, dynamically regulating NA distribution across different brain regions to optimize cognitive and behavioral outcomes [41].

3.3. The LC‐NA System in the Healthy and Diseased Brain

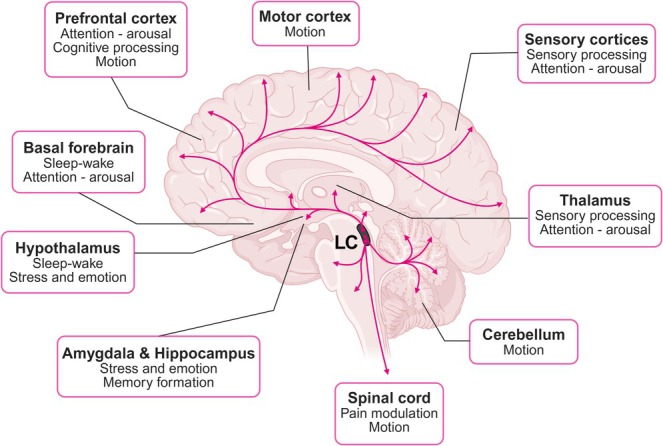

The LC, as the principal source of NA in the brain, has extensive influence throughout the CNS and plays a crucial role in various cognitive and behavioral processes (Figure 2). Alterations in the LC‐NA system can consequently contribute to a range of pathological conditions and disorders. The following section will first examine the function of the LC‐NA system in the healthy brain; followed by an exploration of neurological disorders associated with its dysfunction.

FIGURE 2.

The LC sends widespread projections to numerous brain regions, each associated with specific functions. These include the prefrontal cortex, involved in attention, cognitive processing, and motion; the motor cortex, which regulates voluntary movement; and the sensory cortices, responsible for processing sensory input and mediating arousal. The thalamus also receives input from the LC and contributes to sensory processing and alertness. Projections to the basal forebrain and hypothalamus support sleep–wake regulation and stress responses. The amygdala and hippocampus, which mediate emotional processing and memory formation, are also targets of LC innervation. Additionally, the LC sends projections to the cerebellum, which coordinates movement, and to the spinal cord, where it modulates pain and motor control. The pathways highlighted in the figure demonstrate the LC's widespread influence across brain systems and behavioral functions.

3.3.1. Attention and Arousal

The LC‐NA system plays a pivotal role in regulating arousal, behavioral state, attention, and sensory processing through its widespread projections to the basal forebrain and thalamocortical structures. By modulating activity in the thalamic nuclei and sensory cortices, the LC influences both the gating and tuning of sensory inputs, thereby optimizing information processing. NA promotes a tonic, single‐spike firing mode in thalamocortical neurons, which is essential for the acute processing of sensory information and the effective relay of relevant stimuli to higher‐order cortical areas [1, 12, 64]. The LC also modulates attention through its distinct phasic‐tonic activity patterns. Phasic bursts of NA enhance task‐relevant focus and improve cognitive performance, whereas elevated tonic firing is associated with increased distractibility and exploratory behavior. This dynamic balance between focused and flexible attention is critical for adaptive behavior and cognitive flexibility. NA facilitates selective information processing by amplifying responses to relevant stimuli, while suppressing background noise and irrelevant inputs, thereby increasing the signal‐to‐noise ratio. This mechanism enables organisms to efficiently detect, process, and respond to critical environmental cues, ultimately supporting survival and goal‐directed behavior [3, 65].

Moreover, the LC‐NA system is intricately linked to sleep–wake regulation through its extensive connections with key sleep–wake nuclei, including the basal forebrain, hypothalamus (orexinergic neurons), reticular formation, and preoptic area. Electrophysiological studies in rodents, cats, and monkeys have demonstrated that LC activity decreases progressively from wakefulness (~3 Hz) to quiet resting states (~1 Hz) and becomes nearly silent during REM sleep [66].

Additionally, the LC plays a crucial role in sleep‐to‐wake transitions, with bursts of activity occurring just before spontaneous or sensory‐evoked awakenings [67]. Optogenetic studies further support this role, showing that LC photoactivation increases the probability of awakening in response to auditory stimuli, while photoinhibition reduces this likelihood [68]. Furthermore, the LC receives indirect input from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the central pacemaker of circadian rhythms. Tonic LC activity follows a circadian pattern, exhibiting higher discharge rates during the active phase compared to the inactive phase. This suggests that the LC itself is subject to circadian regulation and may, in turn, contribute to the rhythmic control of sleep–wake states and arousal [69].

Aberrant attentional processing, likely driven by dysregulated LC activity, is a hallmark of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research suggests that in ADHD, LC neurons exhibit excessive tonic firing, leading to reduced phasic activation, which is essential for sustaining focused attention. This altered firing pattern results in difficulty transitioning between attentional states, contributing to impulsivity and distractibility.

Similarly, studies in children with ASD have revealed attenuated habituation to repetitive stimuli and reduced phasic LC activity, indexed by diminished pupil‐linked phasic arousal responses, further implicating LC dysregulation in atypical attentional control mechanisms. Both findings suggest that an imbalance between tonic and phasic LC activity impairs attentional focus and cognitive flexibility. Notably, pharmacological treatments for ADHD, including stimulants and the α2‐adrenergic agonist clonidine, function by reducing tonic LC activity, thereby promoting phasic responsiveness and enhancing attentional performance [47, 65, 70].

Aberrant LC activity is further implicated in sleep disorders such as narcolepsy and insomnia. In narcolepsy, the loss of wakefulness‐promoting orexin neurons disrupts LC firing, contributing to excessive daytime sleepiness. Conversely, insomnia is associated with LC overactivity, likely driven by increased orexin signaling or reduced preoptic neuron function, leading to hyperarousal and impaired sleep initiation [71, 72].

3.3.2. Stress, Emotion and Pain

The LC is activated by a range of endogenous and exogenous stressors, including nociceptive stimuli, pro‐inflammatory cytokines, and psychological stress. The amygdala, a critical structure in emotional processing and fear regulation, maintains reciprocal connections with the LC. Exposure to a stressor induces amygdala activation and CRH release, which increases tonic LC firing while suppressing phasic activity, ultimately promoting a state of hypervigilance. Heightened LC activity leads to increased NA release, particularly affecting α₁‐ARs in the amygdala, thereby amplifying anxiety states. In addition, LC projections to the hippocampus enhance the consolidation of emotionally salient memories, further reinforcing stress‐related responses [73, 74].

Given its central role in stress, emotion, and anxiety regulation, the LC has been extensively studied in psychiatric disorders such as post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). PTSD is characterized by heightened reactivity to unexpected stimuli, a phenomenon partially attributed to excessive phasic LC discharge. This increased NA activity leads to hyperexcitability in limbic structures involved in emotion regulation, particularly the amygdala. MDD has been linked to dysregulation of the LC‐NA system. Genetic and pharmacological studies indicate that enhancing LC function confers resilience to stress‐induced depressive behaviors, whereas NA depletion exacerbates depressive symptoms. These findings underscore the importance of the LC‐NA system as a promising therapeutic target for stress‐related disorders. The clinical efficacy of noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) in treating depression and the attenuation of PTSD symptoms with propranolol, a β‐adrenergic receptor antagonist, further support its relevance in psychiatric treatment strategies [75, 76].

The LC also plays a pivotal role in pain modulation through its descending projections to the spinal cord, which are integral to the endogenous analgesic system. These projections inhibit nociceptive transmission, thereby modulating pain perception. However, sustained pain stimuli can induce neuroplastic adaptations within the LC‐spinal axis, diminishing the inhibitory effects of NA on nociceptive processing and facilitating the transition from acute to chronic pain [77].

3.3.3. Memory

The LC‐NA system plays a pivotal role in modulating memory processes, particularly within the hippocampus, a region essential for learning and memory. Upon encountering novel or arousing stimuli, the LC becomes activated, releasing NA into the hippocampus. This release enhances synaptic plasticity mechanisms such as long‐term potentiation (LTP) and long‐term depression (LTD), which are fundamental for encoding and consolidating new information. Furthermore, NA facilitates the consolidation of long‐term memories by inducing epigenetic modifications that regulate gene expression associated with synaptic strength and endurance of memory storage [78, 79].

Projections from the LC to the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus play a critical role in the integration of distinct memory traces, while not directly influencing initial memory formation. This effect is mediated, in part, by dopamine co‐released from LC noradrenergic terminals, highlighting a neuromodulatory interaction that facilitates memory linking [80]. The LC‐NA system also influences the retrieval of both recent and remote memories. Studies have shown that the activity level of the LC can modulate memory retrieval, with certain frequencies of LC stimulation impairing or enhancing the retrieval process. For instance, stimulation of the LC at 20 or 100 Hz before memory retrieval can disrupt the recall of recently acquired reference memories, an effect mediated by β‐adrenergic receptors [81].

LC degeneration is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and among the earliest cell populations affected by tau pathology. Postmortem studies show ~55% LC neuron loss in AD patients, contributing to cognitive decline by impairing memory, disrupting brain metabolism and blood flow, and compromising amyloid‐β clearance and neuroinflammatory regulation. As an early pathological feature, LC degeneration is a biomarker of disease progression, closely linked to memory loss, attentional deficits, and impaired task execution [82, 83, 84].

3.3.4. Motion

LC projections extend to multiple brain regions involved in movement, including the motor cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and spinal cord. NA regulates dopamine release in the striatum and influences the activity of the subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus, all of which are crucial for initiating, coordinating, and controlling movement. Additionally, LC projections to the PFC have been shown to play a vital role in maintaining posture and mobility. NA also contributes to motor function by regulating spinal cord excitability, affecting reflex activity and locomotor responses, which is particularly important for adapting movement to dynamic environmental conditions [2, 85, 86].

Parkinson's disease (PD) is primarily characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. However, increasing evidence indicates that LC degeneration occurs early in the disease process, preceding the loss of dopaminergic neurons. The depletion of noradrenergic input to the motor cortex and spinal cord diminishes motor flexibility and responsiveness to external stimuli, exacerbating difficulties in movement initiation and execution [87, 88].

The LC‐NA system is also essential for postural control and adaptive gait regulation. Its degeneration in PD has been associated with a higher risk of falls and freezing of gait, both of which are common and debilitating motor symptoms in the advanced stages of the disease. Pharmacological interventions, such as α2‐AR antagonists, have been suggested to enhance LC activity in a primate model of PD, potentially alleviating motor impairments and augmenting the efficacy of co‐administered L‐DOPA [87, 88, 89].

3.3.5. Neuroprotection

NA has well‐documented anti‐inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. By activating β‐ARs on astrocytes and microglia, NA suppresses the nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) signaling pathway, a key regulator of pro‐inflammatory cytokine production. Additionally, β‐AR activation on macrophages and lymphocytes leads to the inhibition of the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α), interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), and interleukin‐8 (IL‐8), while simultaneously increasing anti‐inflammatory cytokine levels [90, 91].

NA also facilitates neuroprotection by promoting cellular survival pathways and stimulating the release of brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [92, 93]. Furthermore, β2‐AR agonists have been shown to counteract α‐synuclein‐induced inflammatory pathways, which play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease [90, 94, 95].

NA also plays a crucial role in multiple sclerosis (MS) by modulating neuroinflammation and immune responses. Research has shown that MS patients and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) models exhibit reduced NA levels and LC damage, suggesting that enhancing NA signaling may offer therapeutic benefits. Increasing central NA levels has been found to reduce disease severity in EAE, likely through its immunomodulatory effects, including the suppression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐17 and IFN‐γ [96, 97, 98]. Dysregulation of adrenergic pathways in MS is also associated with fatigue and depression, highlighting a role for the LC‐NA system in symptom management [99].

4. Locus Coeruleus in Epilepsy

The LC‐NA system exhibits widespread projections throughout the brain, with particularly dense innervation in regions highly susceptible to hyperexcitability and integral to seizure regulation, including the hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala. NA in epilepsy and other neurological disorders has extensively been investigated through pharmacological, lesioning, stimulation, and genetic studies, offering critical insights into its role in seizures and epilepsy [18, 100].

Initial research on the relationship between NA and epilepsy involved LC lesioning studies. Using the neurotoxins 6‐OHDA (6‐hydroxydopamine) or DSP‐4 (N‐(2‐chloroethyl)‐N‐ethyl‐2‐bromobenzylamine hydrochloride), which preferentially destroy LC neurons, has demonstrated that animals with a compromised noradrenergic system exhibit increased susceptibility to seizures induced by various convulsant paradigms, including pentylenetetrazol (PTZ), electroconvulsive shock, and amygdala and hippocampal kindling [100, 101, 102, 103]. Kindling models of epilepsy induce progressive seizure development in response to repeated, initially subconvulsant electrical or chemical stimuli, serving as a model for focal and secondary generalized seizures [104]. Transplantation of fetal LC tissue has furthermore been demonstrated to reverse the heightened seizure susceptibility observed in animals with 6‐OHDA‐induced LC lesions, reinforcing the importance of noradrenergic signaling in seizure modulation [105].

In addition to lesioning studies, investigations involving LC stimulation have provided further evidence of its anticonvulsant effects. Electrical stimulation of the LC has been shown to suppress seizures induced by PTZ and amygdala kindling, suggesting that activation of the LC‐NA system can exert protective effects against hyperexcitability [106, 107]. This anticonvulsant role is further supported by the seizure‐suppressing effects of VNS. We and others demonstrated a strong correlation between enhanced NA transmission and the anticonvulsant properties of VNS [108, 109]. Notably, we identified the α₂‐AR as a critical mediator of VNS‐induced suppression of pilocarpine‐induced limbic seizures, emphasizing the importance of noradrenergic mechanisms in this therapeutic intervention [109].

Collectively, these studies provide compelling evidence that activation of the LC plays a critical role in modulating seizure susceptibility, propagation, and duration. This suggests that the LC undergoes a compensatory moderate activation during seizures and that the loss of LC neurons may contribute to epileptogenesis, the pathological transition from a healthy to an epileptic brain. Supporting this, a study demonstrated that DSP‐4‐induced LC lesioning converted sporadic bicuculline‐induced seizures into self‐sustaining status epilepticus [110]. Additionally, genetically epilepsy‐prone rats (GEPR), which display heightened susceptibility to audiogenic seizures, exhibit deficits in NA content, reduced activity of NA‐synthesizing enzymes, and impaired NA reuptake. Pharmacological restoration of noradrenergic transmission through NA administration, NA reuptake inhibitors, or adrenergic receptor agonists has been shown to ameliorate seizure susceptibility in these animals [100, 111, 112].

Several studies have furthermore demonstrated increased LC activity following various seizure paradigms, as evidenced by elevated expression of Fos, a marker of neuronal activation, along with upregulation of TH and NAT expression [113, 114]. Moreover, heightened multi‐unit activity in the LC has been observed during seizures induced by electrical stimulation of the amygdala [115]. These findings are consistent with our work, which showed that hippocampal seizures differentially modulate LC neuronal activity, eliciting both excitatory and inhibitory responses, while consistently producing a time‐locked increase in NA release within the hippocampus [43]. In contrast, a recent study in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy associated with impaired consciousness reported a reduction in LC multi‐unit activity during electrically evoked hippocampal seizures [116]. The relationship between this reduced neuronal activity and NA release in the hippocampus remains to be elucidated.

In contrast to the previously described anticonvulsant effects of the LC‐NA system, NA release can also exert proconvulsive effects under certain conditions [18, 117]. Evidence from animal and human studies suggests that tricyclic antidepressants may have proconvulsant properties [117]. For instance, in rats, the NA reuptake inhibitors imipramine and desipramine induce spikes and spike–wave complexes by increasing the basal levels of NA in the brain. Chronic administration was associated with proconvulsant effects [118, 119].

The dual effects of NA on seizure activity are not necessarily mutually exclusive but may depend on NA concentration, the activation and expression patterns of AR subtypes, and their specific localization. Activation of α1‐ARs on interneurons and astrocytes enhances GABAergic transmission, leading to circuit inhibition and seizure suppression [18, 28]. Notably, mice with constitutively active α1A‐ARs in hippocampal CA1 interneurons exhibit resistance to seizures, whereas knockout models for this receptor subtype display spontaneous epileptiform activity. This protective effect is attributed to α1A‐AR‐mediated depolarization of GABAergic interneurons, coupled with the release of somatostatin, which collectively enhance inhibitory tone within the CA1 hippocampal circuitry [120, 121]. In contrast, excessive activation of the α1B‐AR subtype has been implicated in proconvulsant outcomes. Mice overexpressing α1B‐ARs exhibit spontaneous seizures, whereas α1B‐AR knockout models demonstrate resistance to chemically induced seizures, such as those triggered by pilocarpine or kainic acid. This proconvulsant effect may be mediated by α1B‐AR‐induced neuronal excitotoxicity, potentially via enhanced recruitment and activation of glutamatergic NMDA receptors, leading to neuronal death and increased seizure susceptibility [122, 123].

The role of α2‐ARs in seizure modulation is more complex due to their function as autoreceptors. Their blockade or activation alters LC activity, with anticonvulsant effects primarily mediated through activation of postsynaptic receptors, whereas presynaptic autoreceptor activation reduces NA release and may contribute to proconvulsant effects [100, 117].

β‐ARs, activated by high NA concentrations as seen during seizures, have been associated with both anti‐ and proconvulsant outcomes [18]. For example, the β‐AR antagonist propranolol inhibits the reduction of penicillin‐induced hippocampal seizures following LC stimulation, indicating an anticonvulsant role of the β‐AR [124]. Propranolol has also been shown to increase seizure threshold in lidocaine‐induced seizures, suggesting a proconvulsant effect of the β‐AR [124, 125]. Extensive evidence highlights the role of β‐ARs in regulating brain excitability, particularly in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG). NA enhances DG granule cell excitability and potentiates the population spike amplitude in perforant‐path evoked potentials [126, 127, 128, 129]. Given that hyperexcitability predisposes the brain to seizures, β‐AR activation is largely associated with proconvulsant effects. Additionally, NA facilitates hippocampal synaptic plasticity, including long‐term potentiation (LTP) and long‐term depression (LTD) in the DG through β‐AR activation [130]. These processes are implicated in kindling and suggest that excessive NA release during seizures, coupled with β‐AR activation, may enhance seizure susceptibility and promote epileptic network formation.

Overall, existing research underscores the pivotal role of the LC‐NA system in epilepsy. NA influences seizure susceptibility, hippocampal excitability, and synaptic plasticity through its interaction with various AR subtypes, making it a critical target for epilepsy treatment [18]. While lesioning and stimulation studies highlight the LC's anticonvulsant role, pharmacological evidence also suggests a potential seizure‐enhancing effect of NA. This indicates that both deficient and excessive NA transmission can increase seizure risk, whether through loss of protective inhibitory mechanisms or excessive activation of excitatory pathways. This leads to an overarching conclusion supported by extensive experimental data, namely that the relationship between noradrenergic transmission and seizure control follows an inverted U‐shaped curve. At low NA levels, the brain lacks sufficient inhibitory tone, increasing susceptibility to seizures. Conversely, at high levels, excessive NA can promote hyperexcitability and network plasticity that facilitate seizure propagation. Moderate levels of NA activity therefore appear to exert the strongest anticonvulsant effects, striking a crucial balance between excitation and inhibition [100, 117].

Author Contributions

Sielke Caestecker: conceptualization, investigation, funding acquisition, writing – original draft, visualization. Emma Lescrauwaet: writing – review and editing. Paul Boon: writing – review and editing. Evelien Carrette: writing – review and editing. Robrecht Raedt: writing – review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. Kristl Vonck: writing – review and editing, supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Caestecker S., Lescrauwaet E., Boon P., Carrette E., Raedt R., and Vonck K., “The Locus Coeruleus—Noradrenergic System in the Healthy and Diseased Brain: A Narrative Review,” European Journal of Neurology 32, no. 9 (2025): e70337, 10.1111/ene.70337.

Funding: The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by research grants from the Flemish Research Foundation (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, FWO) [11M6422N] and the Queen Elisabeth Medical Foundation (GSKE).

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1. Berridge C. W. and Waterhouse B. D., “The Locus Coeruleus‐Noradrenergic System: Modulation of Behavioral State and State‐Dependent Cognitive Processes,” Brain Research Reviews 42 (2003): 33–84, 10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benarroch E. E., Locus Coeruleus (Springer Verlag, 2018), 10.1007/s00441-017-2649-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benarroch E. E., “The Locus Ceruleus Norepinephrine System: Functional Organization and Potential Clinical Significance,” Neurology 73, no. 20 (2009): 1699–1704, 10.1212/WNL.0B013E3181C2937C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vreven A., Aston‐Jones G., Pickering A. E., Poe G. R., Waterhouse B., and Totah N. K., “In Search of the Locus Coeruleus: Guidelines for Identifying Anatomical Boundaries and Electrophysiological Properties of the Blue Spot in Mice, Fish, Finches, and Beyond,” Journal of Neurophysiology 132, no. 1 (2024): 226–239, 10.1152/JN.00193.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schwarz L. A. and Luo L., “Organization of the Locus Coeruleus‐Norepinephrine System,” Current Biology 25, no. 21 (2015): R1051–R1056, 10.1016/J.CUB.2015.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chandler D. J., Jensen P., McCal J. G., Pickering A. E., Schwarz L. A., and Totah N. K., “Redefining Noradrenergic Neuromodulation of Behavior: Impacts of a Modular Locus Coeruleus Architecture,” Journal of Neuroscience 39, no. 42 (2019): 8239, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1164-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henry T. R., “Therapeutic Mechanisms of Vagus Nerve Stimulation,” Neurology 59, no. 4 (2002): 3–14, 10.1212/WNL.59.6_SUPPL_4.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forstenpointner J., Maallo A. M. S., Elman I., et al., “The Solitary Nucleus Connectivity to Key Autonomic Regions in Humans,” European Journal of Neuroscience 56, no. 2 (2022): 3938–3966, 10.1111/EJN.15691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aston‐Jones G., Shipley M. T., Chouvet G., et al., “Afferent Regulation of Locus Coeruleus Neurons: Anatomy, Physiology and Pharmacology,” Progress in Brain Research 88 (1991): 47–75, 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aston‐Jones G., Zhu Y., and Card J. P., “Numerous GABAergic Afferents to Locus Ceruleus in the Pericerulear Dendritic Zone: Possible Interneuronal Pool,” Journal of Neuroscience 24, no. 9 (2004): 2313–2321, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5339-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jodo E., Chiang C., and Aston‐Jones G., “Potent Excitatory Influence of Prefrontal Cortex Activity on Noradrenergic Locus Coeruleus Neurons,” Neuroscience 83, no. 1 (1998): 63–79, 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berridge C. W., “Noradrenergic Modulation of Arousal,” Brain Research Reviews 58, no. 1 (2008): 1–17, 10.1016/J.BRAINRESREV.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valentino R. J., Sheng C., Yan Z., and Aston‐Jones G., “Evidence for Divergent Projections to the Brain Noradrenergic System and the Spinal Parasympathetic System From Barrington's Nucleus,” Brain Research 732, no. 1–2 (1996): 1–15, 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00482-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Bockstaele E. J. and Aston‐Jones G., “Integration in the Ventral Medulla and Coordination of Sympathetic, Pain and Arousal Functions,” Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 17, no. 1–2 (1995): 153–165, 10.3109/10641969509087062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCall J. G., al‐Hasani R., Siuda E. R., et al., “CRH Engagement of the Locus Coeruleus Noradrenergic System Mediates Stress‐Induced Anxiety,” Neuron 87, no. 3 (2015): 605–620, 10.1016/J.NEURON.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lubejko S. T., Livrizzi G., Buczynski S. A., et al., “Inputs to the Locus Coeruleus From the Periaqueductal Gray and Rostroventral Medulla Shape Opioid‐Mediated Descending Pain Modulation,” Science Advances 10, no. 17 (2024), 10.1126/SCIADV.ADJ9581/SUPPL_FILE/SCIADV.ADJ9581_DATA_S1.ZIP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chandler D. J., “Evidence for a Specialized Role of the Locus Coeruleus Noradrenergic System in Cortical Circuitries and Behavioral Operations,” Brain Research 1641 (2016): 197–206, 10.1016/J.BRAINRES.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghasemi M. and Mehranfard N., Mechanisms Underlying Anticonvulsant and Proconvulsant Actions of Norepinephrine (Elsevier, 2018), 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ramos B. P. and Arnsten A. F. T., “Adrenergic Pharmacology and Cognition: Focus on the Prefrontal Cortex,” Pharmacology & Therapeutics 113, no. 3 (2007): 523–536, 10.1016/J.PHARMTHERA.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szabadi E., “Functional Neuroanatomy of the Central Noradrenergic System,” Journal of Psychopharmacology 27 (2013): 659–693, 10.1177/0269881113490326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang H. P., Zhu F. P., Chen X. W., Xu Z. Q. D., Zhang C. X., and Zhou Z., “Physiology of Quantal Norepinephrine Release From Somatodendritic Sites of Neurons in Locus Coeruleus,” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 5 (2012): 20793, 10.3389/FNMOL.2012.00029/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Starke K., “Presynaptic Autoreceptors in the Third Decade: Focus on α2‐Adrenoceptors,” Journal of Neurochemistry 78, no. 4 (2001): 685–693, 10.1046/J.1471-4159.2001.00484.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams J. T., Henderson G., and North R. A., “Characterization of α2‐Adrenoceptors Which Increase Potassium Conductance in Rat Locus Coeruleus Neurones,” Neuroscience 14, no. 1 (1985): 95–101, 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu Y., Liang X., Ren W. W., and Li B. M., “Expression of β1‐ and β2‐Adrenoceptors in Different Subtypes of Interneurons in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex of Mice,” Neuroscience 257 (2014): 149–157, 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cox D. J., Racca C., and LeBeau F. E. N., “β‐Adrenergic Receptors Are Differentially Expressed in Distinct Interneuron Subtypes in the Rat Hippocampus,” Journal of Comparative Neurology 509, no. 6 (2008): 551–565, 10.1002/CNE.21758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buffalari D. M. and Grace A. A., “Noradrenergic Modulation of Basolateral Amygdala Neuronal Activity: Opposing Influences of α‐2 and β Receptor Activation,” Journal of Neuroscience 27, no. 45 (2007): 12358–12366, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2007-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Atzori M., Cuevas‐Olguin R., Esquivel‐Rendon E., et al., “Locus Ceruleus Norepinephrine Release: A Central Regulator of CNS Spatio‐Temporal Activation?,” Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 8, no. AUG (2016): 25, 10.3389/fnsyn.2016.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wahis J. and Holt M. G., “Astrocytes, Noradrenaline, α1‐Adrenoreceptors, and Neuromodulation: Evidence and Unanswered Questions,” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 15 (2021): 645691, 10.3389/FNCEL.2021.645691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fuxe K., Agnati L. F., Marcoli M., and Borroto‐Escuela D. O., “Volume Transmission in Central Dopamine and Noradrenaline Neurons and Its Astroglial Targets,” Neurochemical Research 40, no. 12 (2015): 2600–2614, 10.1007/S11064-015-1574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laureys G., Clinckers R., Gerlo S., et al., “Astrocytic Beta(2)‐Adrenergic Receptors: From Physiology to Pathology,” Progress in Neurobiology 91, no. 3 (2010): 189–199, 10.1016/J.PNEUROBIO.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hansson E. and Rönnbäck L., “Regulation of Glutamate and GABA Transport by Adrenoceptors in Primary Astroglial Cell Cultures,” Life Sciences 44, no. 1 (1989): 27–34, 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Illes P., Finta E. P., and Nieber K., “Neuropeptide Y Potentiates via Y2‐Receptors the Inhibitory Effect of Noradrenaline in Rat Locus Coeruleus Neurones,” Naunyn‐Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 348, no. 5 (1993): 546–548, 10.1007/BF00173217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bai Y. F., Ma H. T., Liu L. N., et al., “Activation of Galanin Receptor 1 Inhibits Locus Coeruleus Neurons via GIRK Channels,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 503, no. 1 (2018): 79–85, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Campos‐Lira E., Kelly L., Seifi M., et al., “Dynamic Modulation of Mouse Locus Coeruleus Neurons by Vasopressin 1a and 1b Receptors,” Frontiers in Neuroscience 12 (2018): 421318, 10.3389/FNINS.2018.00919/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Olpe H.‐R. and Steinmann M., “Responses of Locus Coeruleus Neurons to Neuropeptides,” Progress in Brain Research 88 (1991): 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zitnik G. A., “Control of Arousal Through Neuropeptide Afferents of the Locus Coeruleus,” Brain Research 1641 (2016): 338–350, 10.1016/J.BRAINRES.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Valentino R. J. and Van Bockstaele E., “Opposing Regulation of the Locus Coeruleus by Corticotropin‐Releasing Factor and Opioids: Potential for Reciprocal Interactions Between Stress and Opioid Sensitivity,” Psychopharmacology 158, no. 4 (2001): 331–342, 10.1007/S002130000673/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tkaczynski J. A., Borodovitsyna O., and Chandler D. J., “Delta Opioid Receptors and Enkephalinergic Signaling Within Locus Coeruleus Promote Stress Resilience,” Brain Sciences 12, no. 7 (2022): 860, 10.3390/BRAINSCI12070860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Devoto P., Flore G., Saba P., Fà M., and Gessa G. L., “Stimulation of the Locus Coeruleus Elicits Noradrenaline and Dopamine Release in the Medial Prefrontal and Parietal Cortex,” Journal of Neurochemistry 92, no. 2 (2005): 368–374, 10.1111/J.1471-4159.2004.02866.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kempadoo K. A., Mosharov E. V., Choi S. J., Sulzer D., and Kandel E. R., “Dopamine Release From the Locus Coeruleus to the Dorsal Hippocampus Promotes Spatial Learning and Memory,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 51 (2016): 14835–14840, 10.1073/PNAS.1616515114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Totah N. K., Neves R. M., Panzeri S., Logothetis N. K., and Eschenko O., “The Locus Coeruleus Is a Complex and Differentiated Neuromodulatory System,” Neuron 99, no. 5 (2018): 1055–1068.e6, 10.1016/J.NEURON.2018.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Noei S., Zouridis I. S., Logothetis N. K., Panzeri S., and Totah N. K., “Distinct Ensembles in the Noradrenergic Locus Coeruleus Are Associated With Diverse Cortical States,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119, no. 18 (2022): e2116507119, 10.1073/PNAS.2116507119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Larsen L. E., Caestecker S., Stevens L., et al., “Hippocampal Seizures Differentially Modulate Locus Coeruleus Activity and Result in Consistent Time‐Locked Release of Noradrenaline in Rat Hippocampus,” Neurobiology of Disease 189 (2023): 106355, 10.1016/J.NBD.2023.106355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reimer J., McGinley M. J., Liu Y., et al., “Pupil Fluctuations Track Rapid Changes in Adrenergic and Cholinergic Activity in Cortex,” Nature Communications 7 (2016): 13289, 10.1038/NCOMMS13289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Privitera M., Ferrari K. D., von Ziegler L. M., et al., “A Complete Pupillometry Toolbox for Real‐Time Monitoring of Locus Coeruleus Activity in Rodents,” Nature Protocols 15, no. 8 (2020): 2301–2320, 10.1038/s41596-020-0324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu X., Hike D., Choi S., et al., “Identifying the Bioimaging Features of Alzheimer's Disease Based on Pupillary Light Response‐Driven Brain‐Wide fMRI in Awake Mice,” Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (2024): 9657, 10.1038/S41467-024-53878-Y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhao S., Liu Y., and Wei K., “Pupil‐Linked Arousal Response Reveals Aberrant Attention Regulation Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Journal of Neuroscience 42 (2022): 5427–5437, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0223-22.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boyden E. S., “Optogenetics: Using Light to Control the Brain,” Cerebrum 2011 (2011): 16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Armbruster B. N., Li X., Pausch M. H., Herlitze S., and Roth B. L., “Evolving the Lock to Fit the Key to Create a Family of G Protein‐Coupled Receptors Potently Activated by an Inert Ligand,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, no. 12 (2007): 5163–5168, 10.1073/PNAS.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hwang D. Y., Carlezon J. A., Isacson O., and Kim K. S., “A High‐Efficiency Synthetic Promoter That Drives Transgene Expression Selectively in Noradrenergic Neurons,” Human Gene Therapy 12, no. 14 (2001): 1731–1740, 10.1089/104303401750476230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li Y., Hickey L., Perrins R., et al., “Retrograde Optogenetic Characterization of the Pontospinal Module of the Locus Coeruleus With a Canine Adenoviral Vector,” Brain Research 1641 (2016): 274–290, 10.1016/J.BRAINRES.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang Y., Li B., and Li Y., “Genetically Encoded Sensors for the In Vivo Detection of Neurochemical Dynamics,” Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry 17, no. 1 (2024): 367–392, 10.1146/ANNUREV-ANCHEM-061522-044819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Simpson E. H., Akam T., Patriarchi T., et al., “Lights, Fiber, Action! A Primer on In Vivo Fiber Photometry,” Neuron 112 (2024): 718–739, 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang Y., Rózsa M., Liang Y., et al., “Fast and Sensitive GCaMP Calcium Indicators for Imaging Neural Populations,” Nature 615, no. 7954 (2023): 884–891, 10.1038/S41586-023-05828-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Feng J., Dong H., Lischinsky J. E., et al., “Monitoring Norepinephrine Release In Vivo Using Next‐Generation GRABNE Sensors,” Neuron 112, no. 12 (2024): 1930–1942.e6, 10.1016/J.NEURON.2024.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kagiampaki Z., Rohner V., Kiss C., et al., “Sensitive Multicolor Indicators for Monitoring Norepinephrine In Vivo,” Nature Methods 20 (2023): 1426–1436, 10.1038/s41592-023-01959-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sasaki M., Shibata E., Tohyama K., et al., “Neuromelanin Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Locus Ceruleus and Substantia Nigra in Parkinson's Disease,” Neuroreport 17, no. 11 (2006): 1215–1218, 10.1097/01.WNR.0000227984.84927.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Beardmore R., Hou R., Darekar A., Holmes C., and Boche D., “The Locus Coeruleus in Aging and Alzheimer's Disease: A Postmortem and Brain Imaging Review,” Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 83, no. 1 (2021): 5–22, 10.3233/JAD-210191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Turker H. B., Riley E., Luh W. M., Colcombe S. J., and Swallow K. M., “Estimates of Locus Coeruleus Function With Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Are Influenced by Localization Approaches and the Use of Multi‐Echo Data,” NeuroImage 236 (2021): 118047, 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2021.118047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murphy P. R., O'Connell R. G., O'Sullivan M., Robertson I. H., and Balsters J. H., “Pupil Diameter Covaries With BOLD Activity in Human Locus Coeruleus,” Human Brain Mapping 35, no. 8 (2014): 4140–4154, 10.1002/HBM.22466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Berridge C. W. and Abercrombie E. D., “Relationship Between Locus Coeruleus Discharge Rates and Rates of Norepinephrine Release Within Neocortex as Assessed by In Vivo Microdialysis,” Neuroscience 93, no. 4 (1999): 1263–1270, 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Grimm C., Duss S. N., Privitera M., et al., “Tonic and Burst‐Like Locus Coeruleus Stimulation Distinctly Shift Network Activity Across the Cortical Hierarchy,” Nature Neuroscience 27 (2024): 2167–2177, 10.1038/S41593-024-01755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Aston‐Jones G., Segal M., and Bloom F. E., “Brain Aminergic Axons Exhibit Marked Variability in Conduction Velocity,” Brain Research 195, no. 1 (1980): 215–222, 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90880-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sara S. J. and Bouret S., “Orienting and Reorienting: The Locus Coeruleus Mediates Cognition Through Arousal,” Neuron 76, no. 1 (2012): 130–141, 10.1016/J.NEURON.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Aston‐Jones G., Rajkowski J., and Cohen J., “Role of Locus Coeruleus in Attention and Behavioral Flexibility,” Biological Psychiatry 46, no. 9 (1999): 1309–1320, 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Foote S. L., Aston‐Jones G., and Bloom F. E., “Impulse Activity of Locus Coeruleus Neurons in Awake Rats and Monkeys Is a Function of Sensory Stimulation and Arousal,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 77, no. 5 (1980): 3033–3037, 10.1073/PNAS.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Aston‐Jones G. and Bloom F. E., “Activity of Norepinephrine‐Containing Locus Coeruleus Neurons in Behaving Rats Anticipates Fluctuations in the Sleep‐Waking Cycle,” Journal of Neuroscience 1, no. 8 (1981): 876–886, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hayat H., Regev N., Matosevich N., et al., “Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine Activity Mediates Sensory‐Evoked Awakenings From Sleep,” Science Advances 6, no. 15 (2020): eaaz4232, 10.1126/SCIADV.AAZ4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Aston‐Jones G., Chen S., Zhu Y., and Oshinsky M. L., “A Neural Circuit for Circadian Regulation of Arousal,” Nature Neuroscience 4, no. 7 (2001): 732–738, 10.1038/89522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Solanto M. V., “Neuropsychopharmacological Mechanisms of Stimulant Drug Action in Attention‐Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review and Integration,” Behavioural Brain Research 94, no. 1 (1998): 127–152, 10.1016/S0166-4328(97)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Taheri S., Zeitzer J. M., and Mignot E., “The Role of Hypocretins (Orexins) in Sleep Regulation and Narcolepsy,” Annual Review of Neuroscience 25 (2002): 283–313, 10.1146/ANNUREV.NEURO.25.112701.142826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Riemann D., Spiegelhalder K., Feige B., et al., “The Hyperarousal Model of Insomnia: A Review of the Concept and Its Evidence,” Sleep Medicine Reviews 14, no. 1 (2010): 19–31, 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. McCall J. G., Siuda E. R., Bhatti D. L., et al., “Locus Coeruleus to Basolateral Amygdala Noradrenergic Projections Promote Anxiety‐Like Behavior,” eLife 6 (2017): 18247, 10.7554/ELIFE.18247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Valentino R. J. and Van Bockstaele E., “Convergent Regulation of Locus Coeruleus Activity as an Adaptive Response to Stress,” European Journal of Pharmacology 583, no. 2–3 (2008): 194–203, 10.1016/J.EJPHAR.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Naegeli C., Zeffiro T., Piccirelli M., et al., “Locus Coeruleus Activity Mediates Hyperresponsiveness in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder,” Biological Psychiatry 83, no. 3 (2018): 254–262, 10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Moret C. and Briley M., “The Importance of Norepinephrine in Depression,” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 7, no. Suppl 1 (2011): 9–13, 10.2147/NDT.S19619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Suárez‐Pereira I., Llorca‐Torralba M., Bravo L., Camarena‐Delgado C., Soriano‐Mas C., and Berrocoso E., “The Role of the Locus Coeruleus in Pain and Associated Stress‐Related Disorders,” Biological Psychiatry 91, no. 9 (2022): 786–797, 10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2021.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hansen N., “The Longevity of Hippocampus‐Dependent Memory Is Orchestrated by the Locus Coeruleus‐Noradrenergic System,” Neural Plasticity 2017 (2017): 1–9, 10.1155/2017/2727602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Eschenko O., Mello‐Carpes P. B., and Hansen N., “New Insights Into the Role of the Locus Coeruleus‐Noradrenergic System in Memory and Perception Dysfunction,” Neural Plasticity 2017 (2017): 1–3, 10.1155/2017/4624171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chowdhury A., Luchetti A., Fernandes G., et al., “A Locus Coeruleus‐Dorsal CA1 Dopaminergic Circuit Modulates Memory Linking,” Neuron 110, no. 20 (2022): 3374–3388.e8, 10.1016/J.NEURON.2022.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Babushkina N. and Manahan‐Vaughan D., “The Modulation by the Locus Coeruleus of Recent and Remote Memory Retrieval Is Activity‐Dependent,” Hippocampus 35, no. 2 (2025): e70004, 10.1002/HIPO.70004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. James T., Kula B., Choi S., Khan S. S., Bekar L. K., and Smith N. A., “Locus Coeruleus in Memory Formation and Alzheimer's Disease,” European Journal of Neuroscience 54 (2021): 6948–6959, 10.1111/ejn.15045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kelly S. C., He B., Perez S. E., Ginsberg S. D., Mufson E. J., and Counts S. E., “Locus Coeruleus Cellular and Molecular Pathology During the Progression of Alzheimer's Disease,” Acta Neuropathologica Communications 5, no. 1 (2017): 8, 10.1186/S40478-017-0411-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Braak H., Thal D. R., Ghebremedhin E., and Del Tredici K., “Stages of the Pathologic Process in Alzheimer Disease: Age Categories From 1 to 100 Years,” Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 70, no. 11 (2011): 960–969, 10.1097/NEN.0B013E318232A379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bari B. A., Chokshi V., and Schmidt K., “Locus Coeruleus‐Norepinephrine: Basic Functions and Insights Into Parkinson's Disease,” Neural Regeneration Research 15, no. 6 (2019): 1006, 10.4103/1673-5374.270297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Budygin E., Grinevich V., Wang Z. M., et al., “Aging Disrupts Locus Coeruleus‐Driven Norepinephrine Transmission in the Prefrontal Cortex: Implications for Cognitive and Motor Decline,” Aging Cell 24, no. 1 (2025): e14342, 10.1111/ACEL.14342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhou W. and Chu H. Y., “Progressive Noradrenergic Degeneration and Motor Cortical Dysfunction in Parkinson's Disease,” Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 46, no. 4 (2024): 829–835, 10.1038/s41401-024-01428-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Brian Henry H. S., Fox D. P., Crossman A. R., and Brotchie J. M., “The 2‐Adrenergic Receptor Antagonist Idazoxan Reduces Dyskinesia and Enhances Anti‐Parkinsonian Actions of L‐Dopa in the MPTP‐Lesioned Primate Model of Parkinson's Disease,” Movement Disorders 14, no. 5 (1999): 744–753, 10.1002/1531-8257(199909)14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Grondin R., Tahar A. H., Doan V. D., Ladure P., and Bédard P. J., “Noradrenoceptor Antagonism With Idazoxan Improves L‐Dopa‐Induced Dyskinesias in MPTP Monkeys,” Naunyn‐Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 361, no. 2 (2000): 181–186, 10.1007/s002109900167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sampaio T. B., Schamne M. G., Santos J. R., Ferro M. M., Miyoshi E., and Prediger R. D., “Exploring Parkinson's Disease‐Associated Depression: Role of Inflammation on the Noradrenergic and Serotonergic Pathways,” Brain Sciences 14, no. 1 (2024): 100, 10.3390/BRAINSCI14010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pavlov V. A., Wang H., Czura C. J., Friedman S. G., and Tracey K. J., “The Cholinergic Anti‐Inflammatory Pathway: A Missing Link in Neuroimmunomodulation,” Molecular Medicine 9, no. 5–8 (2003): 125–134, 10.1007/bf03402177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Patel N. J., Chen M. J., and Russo‐Neustadt A. A., “Norepinephrine and Nitric Oxide Promote Cell Survival Signaling in Hippocampal Neurons,” European Journal of Pharmacology 633, no. 1–3 (2010): 1–9, 10.1016/J.EJPHAR.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Liu X., Ye K., and Weinshenker D., “Norepinephrine Protects Against Amyloid‐β Toxicity via TrkB,” Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 44, no. 1 (2015): 251–260, 10.3233/JAD-141062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Mittal S., Bjørnevik K., Im D. S., et al., “β2‐Adrenoreceptor Is a Regulator of the α‐Synuclein Gene Driving Risk of Parkinson's Disease,” Science 357, no. 6354 (2017): 891–898, 10.1126/SCIENCE.AAF3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Laureys G., Gerlo S., Spooren A., Demol F., De Keyser J., and Aerts J. L., “β2‐Adrenergic Agonists Modulate TNF‐α Induced Astrocytic Inflammatory Gene Expression and Brain Inflammatory Cell Populations,” Journal of Neuroinflammation 11 (2014): 21, 10.1186/1742-2094-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Simonini M. V., Polak P. E., Sharp A., McGuire S., Galea E., and Feinstein D. L., “Increasing CNS Noradrenaline Reduces EAE Severity,” Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 5, no. 2 (2010): 252–259, 10.1007/S11481-009-9182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Melnikov M., Rogovskii V., Sviridova A., Lopatina A., Pashenkov M., and Boyko A., “The Dual Role of the β2‐Adrenoreceptor in the Modulation of IL‐17 and IFN‐γ Production by T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 2 (2022): 668, 10.3390/IJMS23020668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Polak P. E., Kalinin S., and Feinstein D. L., “Locus Coeruleus Damage and Noradrenaline Reductions in Multiple Sclerosis and Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis,” Brain 134, no. 3 (2011): 665–677, 10.1093/BRAIN/AWQ362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]