Abstract

Objective:

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a turning point in medical advancement. Despite the burgeoning research in this field, there exists a general lack of overview of where AI is being most utilized. This study reviews and describes techniques and trends of AI in the major medical specialties.

Method:

A literature search was conducted through PubMed in 2024 using two different search methods. Twenty-nine medical specialties were included, including all 24 major medical board specialties and five additional subspecialties.

Results:

There were 143,578 publications involving AI identified with most these (87%) published in the last ten years (124,206) and 52% (74,239) in the last two years. Radiology and Pathology publications were the largest cohorts, 18% (25,319) and 17% (23,828), respectively. Plastic Surgery (1,053), Hepatobiliary (662), and Allergy/Immunology (449) were the least published. There has been a 10,859% growth rate in annual publications across all medical specialties, with Ophthalmology and Preventative Medicine being the fastest-growing areas of research despite Radiology and Pathology being the most researched to date.

Conclusion:

This review underscores AI’s profound impact on medical research, highlighting its significant growth and utilization across various specialties. AI’s influence is most pronounced in Radiology and Pathology, but the substantial increase in publications in Ophthalmology and Preventative Medicine suggests new emerging areas of focus. The ongoing expansion of AI in medicine presents a promising horizon for addressing complex healthcare challenges, fostering a deeper and more comprehensive integration across all specialties.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Computer vision, Healthcare trends, Medical imaging, Multispecialty

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of machine learning into the field of healthcare is a promising technology that has the potential to address many of the less-nuanced tasks in medicine such as billing, transcription, scribing and encounter summaries.1,2 Artificial intelligence (AI) has been widely discussed in the last few years following the introduction of AI chatbots and other AI-assisted technologies to the public. In April of 2024, despite the rapid onset of AI-focused research and the introduction of AI-healthcare startups, only four of the 50 highlighted privately-held startups in Forbes AI50 were healthcare or medicine-focused technologies.3 This is juxtaposed with the increasing enthusiasm behind AI and medicine, which indicates a potential disconnect between the medical industry and medical academia.

There is an intense amount of data coming out regarding AI in healthcare. However, there is a lack of data regarding its utilization by medical specialties. This study intends to evaluate emerging AI trends across different medical specialties, review its application in the literature and assess the state of clinical, academic, and commercial implementation.

METHODS

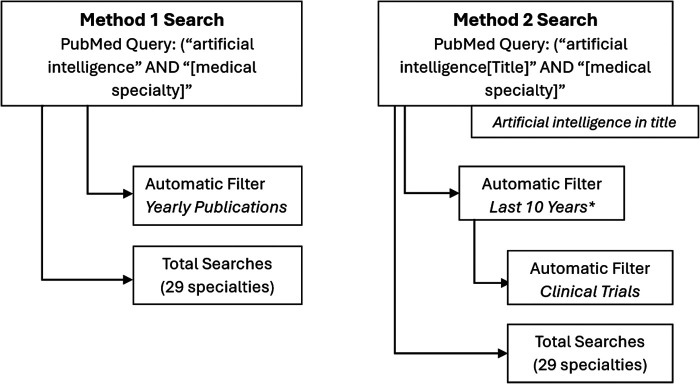

A literature search was undertaken through PubMed between March 2024 and April 2024. Publications were searched for application of AI in each medical specialty and searched under two independent groups. Group 1 included results with the following criterion: “Artificial intelligence AND [medical specialty],” where [medical specialty] refers to one of the 29 specialties queried listed in Table 1. The search reflects gross discussion of AI in the medical specialties. Group 2 included results yielded from the following criterion: “Artificial intelligence[Title] AND [medical specialty],” where the “[Title]” function serves to search for only publications with AI in the title of the article. Group 2 reflects publications where AI serves a functional role in the studies’ research and findings, allowing the application of a filter for trial-based research. Search results were limited to the past 10 years to keep clinically relevant trial data only. The full diagram of search criteria is outlined in Figure 1.

Table 1.

The Major Medical Specialties and Their Exact Terms Explored in the Literature Search

| Allergy and Immunology | Interventional Radiology | Pediatrics |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthesiology | Medical Genetics “OR” Genomics | Physical Rehabilitative Medicine |

| Colorectal Surgery | Neurology | Plastic Surgery |

| Dermatology | Neurosurgery | Preventative Medicine |

| Emergency Medicine | Nuclear Medicine | Psychiatry |

| Family Medicine | Obstetric “OR” Gynecology | Radiation Oncology |

| Gastroenterology | Ophthalmology | Radiology |

| General Surgery | Orthopedics | Thoracic Surgery |

| Hepatobiliary | Otolaryngology | Urology |

| Internal Medicine | Pathology |

Figure 1.

Design method for group 1 and group 2 searches. In group 1, upon analysis of year-to-year publication data, results were separated into 4 nonmutually exclusive groups, filtering for the last 2, 5, 10, and 20 years. In group 2, only yields in the last 10 years were included.

The raw data were collected as comma-separated value spreadsheets and stored in Microsoft Excel. Results are written as the number of publications in a 20-year period, ten year period and year-by-year period, as well as percent published and growth rate as a function of and cumulative growth as a function of .

Twenty-nine medical specialties were queried, using the 24 major American medical board specialties with the addition of four subspecialties we felt needed their own category such as Hepatobiliary, Gastroenterology, Radiation Oncology and Interventional Radiology. Additionally, the American Medical Board of Psychiatry and Neurology represents two closely-linked, separate specialties and were separated in search results. Obstetrics and gynecology included a unique OR function as follows: “Artificial intelligence AND (Obstetrics OR Gynecology)”. We calculated publication per 1,000 physicians per specialty using the American Board of Medical Specialties ABMS Board Certification Report to assess proportional AI utilization by specialty.4

RESULTS

Group 1 Literature Search

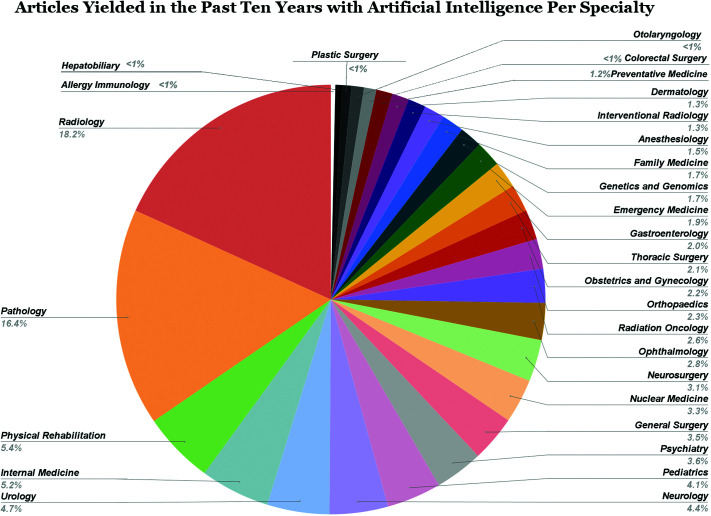

A total of 143,578 publications were yielded in group 1 searches since 1980. Approximately 87% (124,206) and 97% (139,690) of these publications were in the last ten years (2013–2023) and 20 years (2003–2023), respectively. Radiology and Pathology dominated medical research in AI, occupying the highest number of publications comprising 18% (25,319) and 17% (23,828) of total publications over a 20-year period (2003–2023) (Figure 2). Radiology has maintained being the most published specialty with AI, as in the last two years there were 14,228 publications which occupied 19% of results yielded between 2021 and 2023. This contrasts with Pathology which has experienced a decline in publication shareholder with 10,352 (14%), indicating a potential decline in AI utilization for Pathology. The third, fourth and fifth most published specialty over the past 20 years being Physical Rehabilitative Medicine (6%, 8,301), Internal Medicine (5%, 6,771), and Urology (5%, 6,435), which is very different compared to the past 2 years which were Internal Medicine (6%, 4,431), Neurology (5%, 3,565), and Pediatrics (5%, 3,383). The first, second, and third least published specialties in the last 20 years were Allergy Immunology (0.3%, 449), Hepatobiliary (0.5%, 662), and Plastic Surgery (0.8%, 1,053), which was in fact maintained for the past two years as well. The total number of publications over a 2-, 5-, 10-, and 20-year period are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Proportions of medical specialties with publications regarding AI.

Figure 3.

Medical specialties and their respective gross number of publications regarding artificial intelligence in the last 20, 10, 5, and 2 years. Bar peaks represent cumulative publications over 20 years, with each bar section representing their own respective periods for publication. Dark blue (2021–2023), orange (2018–2020), green (2013–2017), and light blue (2003–2012).

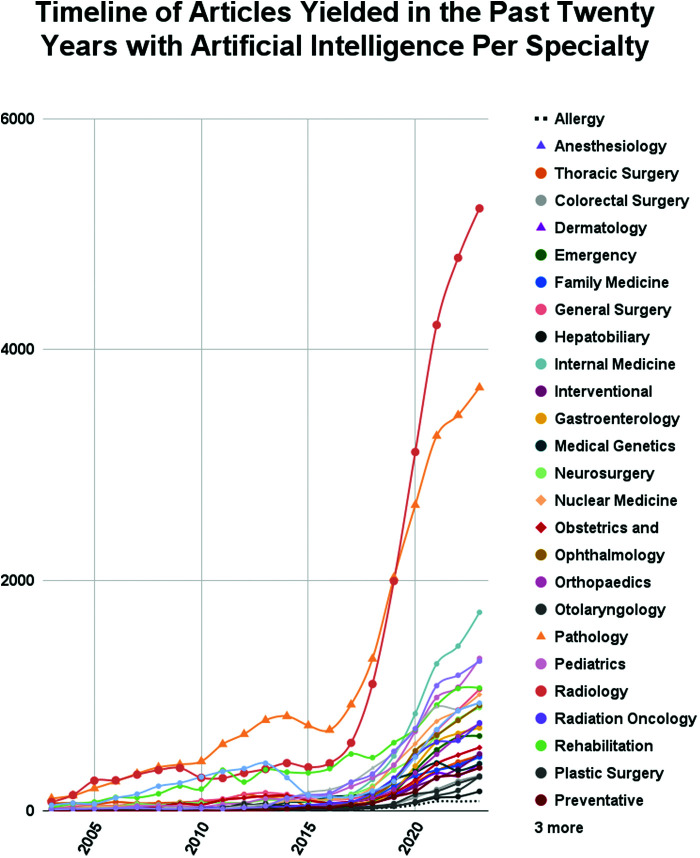

Growth rate was measured as an indicator of growing fields in AI and medicine. Despite Radiology and Pathology experiencing the biggest boom and largest shareholder of medical research in AI, the fastest growing fields were Ophthalmology, Preventative Medicine and Medical Genomics at 45,700%, 37,500%, and 20,500% growth rate, respectively, in the last 20 years. The last two years reflect a much different field, with Plastic Surgery, Interventional Radiology and Otolaryngology with the highest 2-year growth rate at 126%, 74%, and 72%, respectively. Growth rates, shareholder percentage and raw number of publications are shown in Table 2 for all medical specialties in group 1. Overall, the dominance of Radiology and Pathology in the last 20 years is clear, despite the rapid growth of some other specialties (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 2.

Total Publications, Percent Shareholder, and Growth Rate in 29 Medical Specialties over a 2-, 10-, and 20-Year Period

| Medical Specialty | 2-Year Period | 10-Year Period | 20-Year Period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sum | % Total | % Growth | Total Sum | % Total | % Growth | Total Sum | % Total | % Growth | |

| Allergy Immunology | 257 | 0.3% | 2% | 424 | 0.3% | 2,075% | 449 | 0.30% | 2,800% |

| Anesthesiology | 1,253 | 1.7% | 41% | 1,901 | 1.5% | 1,278% | 2,032 | 1.50% | 9,820% |

| Thoracic Surgery | 1,259 | 1.7% | 38% | 2,117 | 1.7% | 3,06% | 2,937 | 2.10% | 600% |

| Colorectal Surgery | 756 | 1.0% | 62% | 1,173 | 0.9% | 386% | 1,319 | 0.90% | 6,020% |

| Dermatology | 1,050 | 1.4% | 25% | 1,610 | 1.3% | 5,063% | 1,668 | 1.20% | 13,667% |

| Emergency Medicine | 1,823 | 2.5% | 23% | 2,575 | 2.1% | 6,420% | 2,644 | 1.90% | 10,767% |

| Family Medicine | 1,221 | 1.6% | 32% | 2,087 | 1.7% | 2,665% | 2,170 | 1.60% | 15,567% |

| General Surgery | 2,629 | 3.5% | 51% | 4,128 | 3.3% | 559% | 4,825 | 3.50% | 4,924% |

| Hepatobiliary | 415 | 0.6% | 47% | 623 | 0.5% | 1,047% | 662 | 0.50% | 17,100% |

| Internal Medicine | 4,431 | 6.0% | 35% | 6,496 | 5.2% | 3,213% | 6,771 | 4.80% | 15,564% |

| Interventional Radiology | 1,150 | 1.5% | 74% | 1,656 | 1.3% | 4,409% | 1,724 | 1.20% | 16,433% |

| Gastroenterology | 1,996 | 2.7% | 20% | 2,798 | 2.3% | 3,700% | 2,864 | 2.10% | 17,950% |

| Medical Genetics and Genomics | 1,183 | 1.6% | −1% | 2,405 | 1.9% | 1,321% | 2,499 | 1.80% | 20,500% |

| Neurosurgery | 2,344 | 3.2% | 39% | 3,905 | 3.1% | 835% | 4,456 | 3.20% | 3,354% |

| Nuclear Medicine | 2,658 | 3.6% | 30% | 4,310 | 3.5% | 1,705% | 4,694 | 3.40% | 6,640% |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 1,450 | 2.0% | 34% | 2,504 | 2.0% | 318% | 2,949 | 2.10% | 4,918% |

| Ophthalmology | 2,361 | 3.2% | 39% | 3,454 | 2.8% | 5,288% | 3,543 | 2.50% | 45,700% |

| Orthopaedics | 1,898 | 2.6% | 54% | 2,792 | 2.2% | 2,348% | 3,038 | 2.20% | 3,200% |

| Otolaryngology | 711 | 1.0% | 72% | 1,160 | 0.9% | 350% | 1,311 | 0.90% | 9,800% |

| Pathology | 10,352 | 13.9% | 13% | 20,333 | 16.4% | 365% | 23,828 | 17.10% | 3,206% |

| Pediatrics | 3,383 | 4.6% | 34% | 5,453 | 4.4% | 1,115% | 5,865 | 4.20% | 6,520% |

| Radiology | 14,228 | 19.2% | 24% | 22,608 | 18.2% | 1,331% | 25,319 | 18.10% | 6,347% |

| Radiation Oncology | 1,978 | 2.7% | 28% | 3,178 | 2.6% | 2,089% | 3,381 | 2.40% | 8,411% |

| Rehabilitation | 3,049 | 4.1% | 16% | 6,715 | 5.4% | 196% | 8,301 | 5.90% | 3,133% |

| Plastic Surgery | 617 | 0.8% | 126% | 868 | 0.7% | 766% | 1,053 | 0.80% | 7,475% |

| Preventative Medicine | 981 | 1.3% | 30% | 1,498 | 1.2% | 3,660% | 1,535 | 1.10% | 37,500% |

| Psychiatry | 2,728 | 3.7% | 4% | 5,091 | 4.1% | 1,497% | 5,363 | 3.80% | 7,750% |

| Neurology | 3,565 | 4.8% | 20% | 5,832 | 4.7% | 2,855% | 6,055 | 4.30% | 7,547% |

| Urology | 2,513 | 3.4% | 32% | 4,512 | 3.6% | 124% | 6,435 | 4.60% | 1,700% |

Figure 4.

Timeline of medical specialties and the number of publications regarding AI per year between 2003 and 2023.

Group 2 Literature Search

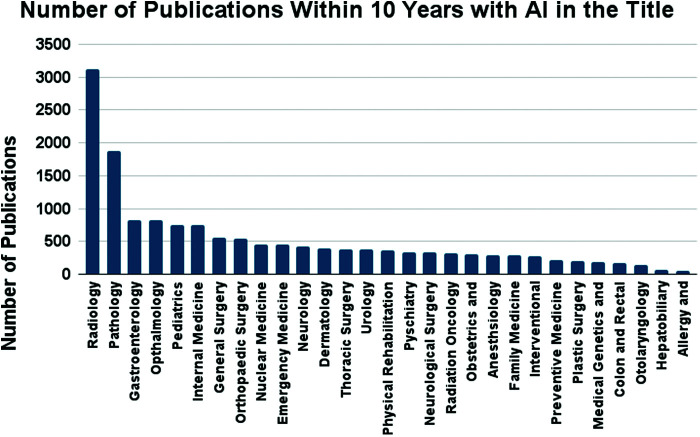

A total of 15,236 articles were yielded in group 2 searches since 2013. Radiology and Pathology consisted of 21% (3,124) and 12% (1,876) of this search, which required “artificial intelligence” to be in the title of the article. Four fields were tied for third most populous at 5% each in total publications, Gastroenterology (826), Ophthalmology (825), Pediatrics (748), and Internal Medicine (746). The first, second and third least published specialties in the last 10 years were Allergy/Immunology (0.3%, 52), Hepatobiliary (0.5%, 70), and Otolaryngology (1%, 147). There is a notable disconnect between the two groups in regard to one specialty in particular: Preventative Medicine. Despite ranking third most researched in terms of publications in group 1, Preventative Medicine ranked poorly in the group 2 searches as the 23rd most published. Additionally, despite the effort to screen papers between 2013 and 2023, 3 specialties had all of their publications in a period more recent than 2013. They were Allergy/Immunology (2016–2023), Colorectal Surgery (2016–2023), Hepatobiliary (2016–2023), and Interventional Radiology (2015–2023) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Medical specialties and their respective number of publications with “artificial intelligence” in the title.

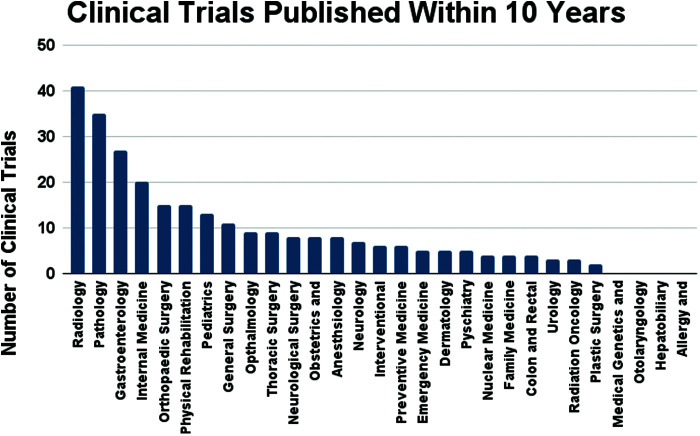

Group 2 results were further selected for clinical trial specific data, in which search parameters included a “clinical trial” or “randomized controlled trial” filter in PubMed. Despite the large number of results, only 1.7% (273) of group 2’s results were found to be clinical trials. Radiology and Pathology maintained their two highest positions at 41 and 35 published research articles, followed by Gastroenterology (27) and Internal medicine (20) (Figure 6). All were published within the last ten years per search parameters.

Figure 6.

Medical specialties and their respective number of clinical trials with “artificial intelligence” in the title.

In an attempt to better represent the data, we normalized publications in group 1, group 2, and group 2 Trial total publication yields to the number of publications in each specialty per 1,000 physicians per the American Board of Medical Specialties Board Certification Report. Interestingly, Nuclear Medicine and Medical Genomics and Genetics dominated both searches, with only the clinical trial data resembling the non-normalized data (see Supplementary Figures S2–S5 for normalized specialty rankings).

A brief sample of some notable and trending topics and AI utilizations were reviewed in each specialty (Table 3). Overall, Radiology and Pathology proved to be the most researched and attractive fields. Therefore, we will highlight some key components and technologies to the research surveyed in radiology and pathology.

Table 3.

Summary of Notable Topics in Each Medical Specialty

| Medical Specialty | Summary of Current Topics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Allergy and Immunology | LLMs are useful in providing clinical summaries with limited diagnostic and evidence based assistance. | 76 |

| Anesthesiology | Analysis of depth of anesthesia, signals for alertness/awakeness, discrimination of awake vs coma, alert system for organ failure and sepsis, identification of pain using whole brain scan analysis, nociception identification skin conductance. | 77 |

| Cardiothoracics | CADD using CT, ECC, Coronary Angiography, Echocardiogram to address acute coronary care involving acute coronary occlusions and disease, dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, pulmonary emboli, aortic and coronary stenosis, cardiac amyloidosis. | 8 |

| Colorectal Surgery | Neural network classifying colorectal relapse based on genetic markers. CP-ANN detection of colorectal mutations. Polyp and adenoma deep learning detection during colonoscopy, classification of lesions using virtual staining technique. | 78 |

| Dermatology | CNN usage of comparable or increased accuracy/sensitivity of classification of skin lesions from dermoscopic and non dermoscopic test images. CADD dermatoflouroscopy may provide more information than traditional dermatoscopic photography for melanoma detection. DL comparable or superior classification and triage of melanoma. Assistance of nonderm primary care assessment of lesions. Ensuring equitable data mining and buttressing against worsening health-care disparities in underrepresented groups using model abstention. Increasing accessibility by improving teledermatology standards using AI. | 79 |

| Emergency Medicine | MLP prediction of emergency hyperglycemic crises. Selection of patients for mechanical thrombectomy following large vessel occlusion. Morphological analysis of plaque in occlusions, diagnosis of large vessel occlusions. Faster triage in stroke patients. Detection of acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction. (OMIAI). | 9,11,13,80 |

| Family Medicine (Primary Care) | Limited LLM applications but potential utility when responding to particularly negative EHR messages which contribute to burnout. Continuous AI-EHR alert system for high risk of adverse outcome or health effect. Assist in administrative loads leading to burnout (scheduling, billing, documentation, referrals, literature). | 2,58,59 |

| Hepatobiliary | AI-based prediction models of inflammatory and immune gene signatures in hepatocellular carcinoma. Deep learning analysis of video capsule endoscopy, improving identification of small-bowel ulcers, polyps, bleeding, lymphangiectasia, follicular hyperplasia, lesions, diverticula and inflammation. Faster processing and speed of analysis. Improved prediction of acute pancreatitis in ANN models with fewer input parameters. CADD using endoscopic ultrasonography imaging to identify and classify pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Real-time augmented reality using AI-segmented CT images superimposed during pancreatectomy. | 10,42,81 |

| Internal Medicine | There are over 200 ML based medical devices approved in the United States for the purpose of monitoring/managing internal disease such as diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea. CADD of diabetic retinopathy without an ophthalmologist. Artificial intelligence-assisted body composition risk assessment for TAVI using muscle/fat density. Hypertensive and cardiovascular disease prediction using lifestyle, biochemical and body examination parameters. | 82–84 |

| Gastroenterology | CNN and SVM detection and classification of neoplasia from upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in Barrett's esophagus. Prediction of H. pylori from conventional endoscopy footage. Delineation between noncancerous and cancerous areas from NBI, BLI and UGI images. Gastric bleeding risk prediction. Premalignancy, polyp and helminth during colonoscopy. Inflammatory bowel disease prediction using genomic data. CNN grading of ulcerative colitis and site-specific inflammation from colonoscopy. Prognostic algorithms for acute gastric bleeding. | 10,15,17,18 |

| Medical Genetics and Genomics | Construction of deep learning models which predict immunotherapy outcomes based on genomic, epigenetic and transcriptomic data. Construction of genomic signatures based on these parameters to stratify risk in patients. Development of increased sensitivity and awareness to new biosignatures (chemokines, cell stemness, angiogenesis, DNA methylation) using DL genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics. | 85 |

| Neurosurgery | Identification of patients' intra/peri-operative outcomes such as risk for CSF leak, hemorrhage or ischemia during/after endosurgery. ML 3D auto segmentation of spine and AI-recommended placement for spinal fusion instrument placement (rods, plates, screws). Neuro-ICU ML assistance in managing large intensive uneven patient datasets. Smartphone AI application to increase patients adherence to postoperative antiplatelet therapy. | 24,25,86 |

| Nuclear Medicine | Detection of pathology, monitoring and planning of treatment pathways and management/analysis of radiomic features and meta-data. | 87,88 |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | CNN prediction of cervical, endometrial, uterine and ovarian diagnosis, survival and lymph node metastasis. Cardiotocography and uterine electrical signal analysis to detect episodic changes, preterm labor and general monitoring of labor. NN development of a noninvasive test for ovarian cancer using circulating miRNA. | 20,89 |

| Ophthalmology | CNN detection of more-than-mild diabetic retinopathy from fundus photography and macular edema from optical coherence tomography. Meibography analysis and classification of dry eye. Keratoconus staging and classification. ML at adjuncts for visual field detection of preperimetric glaucoma up to 4 years in advance of clinical diagnosis. Refractive error detection smartphone app. | 22,23 |

| Orthopedic Surgery | Fracture, ACL/PCL, osteoarthritis, site infections and optimal injection point detection and prediction. Clinical outcome prediction following total joint arthroplasty. CADD of disc pathology utilizing CNN labeled and segmented MRI images with 97% accuracy. Musculoskeletal biomechanical applications of testing stress, load and gait for both disease affected tissues and patient specific data. | 14,90 |

| Otolaryngology | Potential in ML detection of laryngeal cancer, benign mucosal disease and vocal cord paralysis. | 19 |

| Pathology | Synthesis of histopathological and DNA/transcriptional-level features (-omics) under the direction of AI can offer more specific subclassifications of malignancies. CADD of histopathological data aids diagnosis by reducing variability and pathologist workload. | 31–33,91 |

| Pediatrics | CNN analysis and identification of dental caries, ectopic eruptions, plaque and forensic age estimation. One development of an AI pediatric diagnostic framework which was comparable to physician diagnosis. Limited image-based deep learning CADD of IBD and/or colorectal cancer screenings. Radiomics. | 65,92–94 |

| Physical Rehabilitation | Robot assisted exoskeleton for the purpose of walking and rehabilitation.Restoration of limb movement utilizing ANN intracortical brain-computer interface. | 95 |

| Plastic Surgery | ML assessment for risk of microvascular flap failure, seroma, infection, lymphedema, capsular contraction and postoperative persistent pain in breast, head/neck, back and extremity reconstructive surgery. AI quantification of esthetic outcomes from facial recognition and skin analysis to improve patient awareness of outcomes and evidence-based surgery. | 96,97 |

| Preventative Medicine | Total AI integration with big data for the assessment of risk in all fields for disease using multilevel multifactorial risk detection including disease progression, risk of suicide and comorbid progression from treatment (toxicity, failure). ML integrated wearable devices for the purpose of monitoring internal diseases. AI-assisted health program on workers with head/shoulder, neck and back pain and stiffness to improve symptoms. | 75,98–100 |

| Psychiatry | Multiple publicly available LLM chat/therapy bots exist to decrease loneliness and offer similarly judgment-free and emotional wellness coping strategies. Prediction of PTSD using predeployment blood sample data. Potential AI monitoring of smartphone, Fitbit and social media information to detect psychiatric relapse. | 24,101–103 |

| Neurology | MDD pharmacogenomic ML generation and identification of SNP-linked treatment outcomes. AI driven prognostication of the structure and function of proteins, their interprotein interactions and drug-protein interactions. AI identification of neuroprogression in psychiatric illnesses using ML analysis of fMRI neuroimaging. AI discrimination of late-onset AD versus traditional aging using MRI data. DL decoding, classification, detection and identification of mental visual imagery from neuroimaging during sleep and activity. | 56,63,104,105 |

| Radiology | CNN/DL detection, identification, classification and diagnosis of cancer utilizing radiographic imaging (MRI, CT, PET, fMRI) in colorectal, cardiothoracic, neurological, genitourinary, hepatobiliary and all other internal subspecialties. Real-time augmented reality using 3D-reconstruction of AI-generated imagery for intraoperative improvement of tumor and anatomy visualization. | 5,7,62 |

| Radiation Oncology and Interventional Radiology | Automated segmentation of OAR delineation for radiotherapy dosimetry. Improved contouring accuracy using CNN-based automatic contouring. Reduced reliance on subjective clinical physics and development of voxel-by-voxel optimal dosimetry utilizing individual patient data. Prediction of radiation induced toxicity. Deep learning real time adaptive radiotherapy using image reconstruction and motion estimation. AI-assisted robotic navigation of catheterization, alongside augmented reality for intraprocedural visualization from radiographic information. AI-analysis of radiomics, genomics and transcriptomic information could better improve selection for interventional radiology. | 28,62,64,106 |

| General Surgery | CNN recreation of augmented reality for intraoperative enhancement of features of interest. Preoperative risk assessment, intraoperative monitoring and event detection/prediction and postoperative morbidity and mortality prediction. Infancy of truly autonomous AI-controlled robotic surgeries. AI-enhanced and generative interactive simulation for surgical education. | 25,57,81,97,97,107 |

| Thoracic Surgery | CAD of lung nodules and differentiating on malignancy and classification using CT, MRI, and nuclear medicine. AI classification and identification of lung adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma using quantitative histopathology images. Pulmonary function test analysis, pattern recognition and diagnosis by AI. Real time classification of anatomy during laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy. | 12,107,108 |

| Urology | Prediction, classification, staging, and/or diagnosis of prostate biopsy, urine cytology, urinary continence, stone free status and risks in renal failure, mortality, and recurrence. AI analysis of surgeon performance to predict patient outcomes in radical prostatectomy. AI identified gene signature identification of bladder cancer progression. Urolithiasis identification, composition and time-to-passage prediction. | 21,109 |

LLM, limited-language model; CT, computer tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; CP-ANN, computer programmed artificial neural metwork; CADD, computer assisted detection and diagnosis; MLP, machine learning program; AI, artificial intelligence; HER, electronic health record; ANN, artificial neural network; ML, machine learning; CNNL, convolutional neural network; SVM, support vector machines; NBI, narrow band imaging; BLI, blue light imaging; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; DL, deep learning; CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; NN, neural networks; ACL-PCL, anterior cruciate ligament-posterior cruciate ligament; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; IBD, irritable bowel disease; MDD, major depressive disorder; SNP, small nucleotide peptides; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PET, positron emission tomography; OAR, organs at risk.

AI Applications in Radiology

Medical imaging encompasses the broader spectrum of radiological applications in multispecialties. There are 3 major components of medical imaging in which AI is most applied to: acute, chronic and prognostic tasks. The premise of computer vision-based AI platforms in medical imaging is the usage of computer-aided detection techniques in recognizing patterns in visual information followed by analyses and generating conclusions based on such data. Computer vision’s automated image processing/segmentation and prognostic optimization takes advantage of Computer-Aided Detection and Diagnosis (CADD) systems which is the major field for AI based computer vision analysis of medical imaging to make decisions and diagnoses.5,6 The specific tasks CADD AI engages in are classifying images and assigning labels, describing and outlining notable structures, categorizing whole parts of the image and segmenting specific structures and making discrete labels.7

CADD has been employed in both triaging acute disease and diagnosing chronic disease. Emergency triaging of acute disease using CADD AI with imaging includes, but is not limited to, acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary emboli, coronary stenosis, acute appendicitis, acute pancreatitis, acute intracranial hemorrhage/stroke, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, acute internal injury, bowel obstruction and acute gastrointestinal bleeds.8–16 Specific applications are further delineated in Table 2.

Diagnosis of chronic disease using CADD in imaging includes polyp, lesion and adenoma detection, classification and analysis during colonoscopy or small capsule endoscopy, identification of ulcers, bleeding, lymphangiectasia.17,18 It further includes classification and grading of ulcerative colitis and bowel inflammation, detection of benign/premalignant/malignant neoplasia during upper gastrointestinal endoscopies and Barrett esophagus and H. pylori identification from endoscopic footage.10,17,18 CADD of pulmonary, laryngeal, esophageal, sinusoidal, cervical, endometrial, uterine, ovarian, prostate and genitourinary lesions and lymph node metastasis are additional known uses.19–21 Detection of subretinal fluid, macular edema, diabetic retinopathy from optical coherence tomography and fundus photography are hallmarks in ophthalmic imaging as well.22,23 CADD of neuroprogression in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease, brain metastases, trauma and cord pathology can be employed.24–26 Further analysis includes CADD of fractures, tears, rheumatoid and osteoarthritis, fibrosis and site infections.25–27

Radiographic segmentation is a crucial step in determining diagnosis or deciding specific therapy. AI automates the process of auto segmentation of spinal imaging for recommended injection/instrument placement or radiotherapy dosimetry/positioning.5,26,28 Findings can be integrated into electronic health record systems for automatic flagging, enhancing the integration of CADD systems in clinic.2,29

AI Applications in Pathology

Carrying forward the premise of CADD systems into pathology, the technology is similarly purposeful in diagnostics, automated processing/segmentation and prognostic enhancements. Furthermore, virtual staining and the simulation of histopathological staining (immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, hematoxylin and eosin) partnered with machine-learning automated diagnosis offer faster, more efficient and less costly methods for pathological analysis.30 CADD of unique features in histological imaging and data provides diagnostic support to both pathologists and medical researchers.31–34

Quantitative capabilities of cell counts, density and structure identification are key features to CADD in Pathology.35,36 Classification, staging, grading, structural segmentation, feature identification of sampled tissue are all focal points of research in CADD in Pathology.32,37–40 Analysis of cellular matrix, cytoplasmic material, membranous components, nuclear features and chromatin structures are additional areas of focus in CADD. Additionally, the tumor microenvironment for biomarker expression such as cellular receptors and matrix proteins is another key strategy being employed to enhance current practices in pathology research particularly.41,42

Additional usages of AI in medical pathology offer the potential to improve standardization tools for pathological grading. There lies variability in grading, which can lead to downstream candidacy determination issues in a variety of disease and treatment.43,44 AI has been offered as a tool to standardize these variations, offering improved diagnostic and prognostic grading/scoring tools.33,45–47 In this endeavor to improve identification and scoring comes the offer to better predict prognosis and response to treatment. AI has been used to predict therapeutic success using molecular and cellular data.40,48–50

AI Applications in Medical Industry

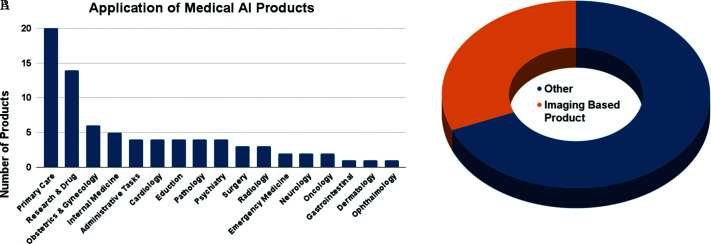

In order to assess the weight of AI utilization outside of medical academia and instead on current applications on the market, we conducted a survey of 80 med-tech products using AI using the Google search engine. In it, we collected the specialty associated with the product, the general application of the product, the technique of AI utilized and whether the product fell into medical-imaging or not. Radiology/Pathology comprised 1/3 of the total medical AI publications in the last 20 years. Similarly, 31% of the products surveyed were CADD products for medical imaging. Despite this similarity, this percentage is much less than expected given the already understood depth of mostly imaging-based AI applications in the other medical specialties (Cardiology, Gastroenterology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Orthopedics, and Emergency Medicine). Interestingly, primary care was the most used application of AI (25%) when separated by specialty, followed by research and drug discovery (18%), internal medicine (6%), yet 31% of the total was imaging based technology in a multitude of specialties (Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cardiology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedics, Cardiology, Neurology, and unspecified Radiology applications) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

AI utilization in the medical industry after surveying 80 medical AI products. (A) Number of products per specialty or specific utilization. Primary care includes a variety of applications from internet triaging to wearable medical devices to monitor patient at-home. (B) Proportion of products utilizing computer vision in the medical imaging space, including live intra-operative and endoscopic technology.

DISCUSSION

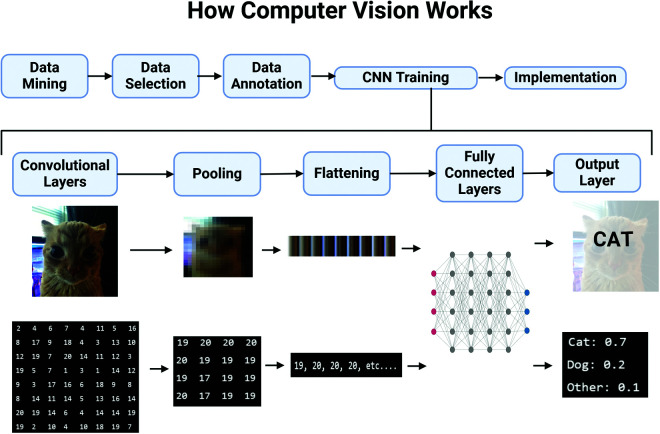

AI has been an exciting and controversial discussion representing a major landmark in medical sciences. Untapped and largely misunderstood, there is potential to revolutionize all fields of medicine, patient care, medical administration and treatment discovery. This study demonstrated that current applications are largely of an imaging-based domain. Computer vision is the field of AI which incorporates image-processing techniques to achieve decision-making algorithms. CADD is the specific application of convolutional neural networks (CNN) and computer vision into a clinical and diagnostic setting. The general process can be described in six steps which are edited and optimized by the CNN itself.5,51 In order to help visualize this process, a graphic was generated highlighting an example of converting an image of a cat into a probabilistic decision by the AI (Figure 8; see Appendix 1 for full explanation).

Figure 8.

Demonstration of how computer vision AI technology works using the perspective of what the AI “sees” and what that would look like to humans. See Appendix 1 for full details. Created in BioRender. Popover J (2025) https://BioRender.com/d99s727.

Radiology and Pathology dominate, but fields like Cardiothoracics, Gastroenterology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Orthopedics, and Emergency Medicine also show high AI engagement. All of these fit in the computer-vision side of AI in medical research. Genomics, Nuclear Medicine, and Preventative Medicine are still developing, and despite them taking advantage of machine learning, their popularity compared to vision-based AI underscores this dichotomy observed between imaging and nonimaging AI utilization in medical literature. Despite that, upon proportionally normalizing publication data by number of physicians in each specialty, Genomics and Nuclear Medicine emerged as front runners, highlighting a nuanced field where these specialties are disproportionately involved in research. We hypothesize on a couple of explanations below, however these all remain significantly understudied and serve as potential avenues for exploration.

This study found that despite the robust output of AI related projects, only 1.7% (273) of the ∼15,000 papers with AI in the title were found to be clinical trials per the database’s autofilter for “randomized-controlled trials” and “clinical trials.” This polarity contributes to an emerging perspective of a more underwhelming perspective of AI utilization. This gap provides a framework for future exploration that combines clinical review with industry analysis and real-world implementation trends. One of the reasons for this dichotomy could lie in the retrospective and redundant nature of computer vision medical AI. Data collection and AI training can pose great difficulty, however there exists no shortage of colossal databases online for radiological/pathological CNN training.52–55 In conjunction with open-access AI architectures, computer vision studies often present a game of mix-and-match where each and every combination of dataset-annotators-CNN-medical specialty-tissue/imaging models are tested. Additionally, there lies great skepticism in implementing these techniques into a clinical setting due to the litany of concerns surrounding transparency, medical ethics and preclinical demonstrations—which are discussed later. This could make AI clinical trials much harder to implement and gain approval in comparison to retrospective “test-runs.”

This study examined the extensive utilization of AI in the medical specialties and provides a brief overview of some notable task-specific utilization. The potential for managing acute and chronic disease, optimizing therapeutic strategies and enhancing therapeutic and disease prognosis is great. Currently AI stands suitable in identifying visual information and some correlational predictive modeling. AI can consider nonlinear relationships and modify its own filters, weights and algorithm architecture which may reduce the variability between diagnosis and disease management/treatment. Through the integration of qualitative patient-specific health, behavioral, and demographic data with precision-based fields such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and radiomics along with traditional imaging and laboratory data into large scale, multileveled AI systems, the insurmountable heterogeneity of disease and patient care can be addressed as evidenced here.2,4,5,28,30,56–65

This concept of “big data” has fueled the conversation on AI in healthcare, with disputing cases for greater collection of data to fuel AI research, with some arguing the opposite—that the overload of excess and unorganized data can create certain risks such as overfitting, over generalizability, poor specificity to realistic clinical data and underrepresentation for certain racial, ethnic or socioeconomic minorities.62,66–71 Additionally, more data may be more problematic, as AIs which have been trained on data for one task, fare worse than if they were to be trained on data specific for the task for which they are accomplishing.72

Overgeneralization of one population is a concern in cases of repurposed datasets, as it can mask a clinic’s true patient population representing entirely different sets of demographics based on location and service offered. Having specific and representative datasets to the task at hand can mitigate these risks. Other risks include the “black box” phenomena, which is the idea that AI makes decisions, conclusions and self-optimizes in a way that is veiled and unobservable to the developer and the clinician.64,73 Similarly, this process can also be seen in even the human contributors to the studies, with specifics to training not being explicit in methodology.14 A proposed solution is the embracing of “explainable” machine learning, whereby it is a crucial component to have an AI capable of informing its user on how it makes its decisions/optimizations.73–75

Limitations of this study lie in the redundancy of research and the sheer mass of papers examined. Group 1 gives a sound overview of the AI discussion in research, but lacks clarity to what extent AI is truly represented in these articles, given the sheer mass yielded and no qualitative assessment was undertaken. Despite this, results between the groups are comparable suggesting this is a limited concern. When looking at specialties, we attempted to normalize data to the proportion of board certified diplomates in the United States, which could conversely distort the data as the articles screened were multinational in nature. Another drawback is an overlap of articles found between searches of two or more specialties. This could contribute to inflated findings of publication data if the same article of “Artificial intelligence and radiomics in pediatric molecular imaging” is found in both radiology, pediatric and radiation oncology results.65 A strong and robust meta-analysis looking into the specificity of clinical trial data and qualitatively sorting clinically relevant AI findings is necessary and would improve upon this birds-eye view examination. We have demonstrated a sound proxy for AI utilization but would recommend adding additional search criteria including “computational model,” “deep learning,” and “machine learning” to give greater specificity to the type of AI being leveraged. Additionally, given that most data has been published within the last 2 years, we recommend keeping literature searches limited to more recently as we have accomplished a 20-year perspective on AI trends in medicine. Finally, in order to better understand the differences between academia and industry, research at the intersection of human behavior and AI implementation may prove useful to better understand and guide AI integration.

CONCLUSION

Radiology and Pathology dominate current research, which leaves much room to be filled with the other medical specialties. Applications can take inspiration from the brevity of research in Radiology and Pathology but have great potential outside visual machine learning, including app and home device development, patient compliance and behavioral tracking, predictive risk modeling, workflow/treatment plan optimization and incorporation of genomic, transcriptomic and other biochemical markers for disease. AI in the med-tech market matches the boom in medical imaging applications that is observed in academia, yet the major participants in machine learning lie also in primary care and drug discovery. Currently, there are limited commercial instances of AI utilization benefiting clinics and a notable lack of AI based clinical trials. This suggests that innovation will move outside the status quo of clinical trials. More research needs to be understood on the marriage between clinical science and AI, and the pitfalls associated with it. Physicians, educators and leaders alike need to arm themselves with robust and intimate understanding of AI in order to make better decisions with AI and understand its potential and shortcomings.

Appendix 1 (Figure 8 explained in detail):

First, data is uploaded to the learning algorithm which is pre-annotated/manipulated for the CNN to “learn” what – for example – a cat looks like (features, shapes, edges, colors). There are a great many strategies through which learning takes place, however these are out-of-scope50. Secondly, the convolutional layers take a new image and convert each pixel or region of pixels to a specific value using filters – or “kernels”. These kernels are responsible for transducing visualinformation to 2-dimensional numerical sets and, similar to human eyes, are a critical area of optimization during training.

In order to simplify this complex dataset, a technique called pooling is utilized. One can imagine this is the equivalent to zooming out of an image of a cat allowing only the most pertinent and obvious features to be visible. The CNN will then recognize these prominent features, such as the edges between two objects, the colors/shadows of a certain area and the shapes of structures and recalculate a 2-dimensional set of values to represent this newly simplified “blurry” picture.

This convolutional-to-pooling process can occur multiple times and is a target for adjustment and training. When optimizing, the AI will learn what algorithm to use in order to achieve the most accurate representation of the original dataset, while improving the recognizability of the new dataset. The next technique involves the reorganization of 2-dimensional data into a 1- dimensional set of numbers in a process called “flattening”. Imagine the blurry and pixelated photo of the cat being deconstructed into long strings and layed out in order. The numbers here are not changed, only reorganized.

The fifth and most crucial step in the CNN is the neural network itself. At this point, you may have multiple “starter neurons” receiving input information in the form of these long strings created during flattening. Each neuron is connected to each and every neuron in the next “layer” so to speak, similar to the brain. At each layer of neurons a more complex interpretation of the data would result and this deconstructed image would look more like a list of features such as “feline eyes, pointed ears, orange fur”. The final step provides a distribution of potential identifications with an associated probability to determine the most accurate outcome – being a cat.

Created in BioRender. Popover, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/d99s727

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: none.

Disclosure: JLP, SW, JF, GC, CK, AI, and MA have no disclosures. PT - receives funding from Intuitive Surgical for the Florida Surgical Specialists Enhanced General Surgery.

Fellowship: Advanced Laparoscopic and Robotic Foregut, Hernia, and Colorectal Fellowship.

Funding sources: none.

Contributor Information

Jesse L. Popover, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey)

Spencer P. Wallace, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey)

Jeremie Feldman, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey); American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine, Cupecoy, Sint Maarten. (Dr. Feldman).

George Chastain, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey).

Chris Kalathia, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey).

Adnan Imam, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey); Cardiovascular Division, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. (Dr. Imam).

Majd Almasri, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey).

Paul G. Toomey, Florida Surgical Specialists, Bradenton, Florida, USA. (Drs. Popover, Wallace, Feldman, Chastain, Kalathia, Imam, Almasri, and Toomey).

References:

- 1.Malik P, Pathania M, Rathaur VK, Amisha. Overview of artificial intelligence in medicine. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(7):2328–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkomar A, Oren E, Chen K, et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. Npj Digit Med. 2018;1(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai K. 2024. The Forbes AI-50 list. Forbes. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/lists/ai50/. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Board of Medical Specialties. 2023. ABMS Board Certification Report 2022-2023. https://www.abms.org/abms-board-certification-report/.

- 5.Yamashita R, Nishio M, Do RKG, Togashi K. Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(4):611–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esteva A, Robicquet A, Ramsundar B, et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najjar R. Redefining radiology: a review of artificial intelligence integration in medical imaging. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(17):2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doolub G, Khurshid S, Theriault-Lauzier P, et al. Revolutionising acute cardiac care with artificial intelligence: opportunities and challenges. Can J Cardiol. 2024;40(10):1813–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman R, Meyers HP, Smith SW, et al. International evaluation of an artificial intelligence–powered electrocardiogram model detecting acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2024;5(2):123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kröner PT, Engels MM, Glicksberg BS, et al. Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology: a state-of-the-art review. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(40):6794–6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parvathy G, Kamaraj B, Sah B, et al. Emerging artificial intelligence-aided diagnosis and management methods for ischemic strokes and vascular occlusions: a comprehensive review. World Neurosurg X. 2024;22:100303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillis JM, Bizzo BC, Mercaldo S, et al. Evaluation of an artificial intelligence model for detection of pneumothorax and tension pneumothorax in chest radiographs. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2247172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issaiy M, Zarei D, Saghazadeh A. Artificial intelligence and acute appendicitis: a systematic review of diagnostic and prognostic models. World J Emerg Surg. 2023;18(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers TG, Ramkumar PN, Ricciardi BF, Urish KL, Kipper J, Ketonis C. Artificial intelligence and orthopaedics: an introduction for clinicians. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(9):830–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shung D, Simonov M, Gentry M, Au B, Laine L. Machine learning to predict outcomes in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(8):2078–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennani S, Regnard NE, Ventre J, et al. Using AI to improve radiologist performance in detection of abnormalities on chest radiographs. Radiology. 2023;309(3):e230860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro T, Mascarenhas M, Afonso J, et al. S1357 artificial intelligence and capsule endoscopy: automatic detection of small bowel lymphangiectasia and xanthomas using a convolutional neural network. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(1):S624–S625. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori Y, Kudo S, Mohmed HEN, et al. Artificial intelligence and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: current status and future perspective. Dig Endosc. 2019;31(4):378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HB, Song J, Park S, Lee YO. Classification of laryngeal diseases including laryngeal cancer, benign mucosal disease, and vocal cord paralysis by artificial intelligence using voice analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akazawa M, Hashimoto K. Artificial intelligence in gynecologic cancers: current status and future challenges – A systematic review. Artif Intell Med. 2021;120:102164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Checcucci E, Cacciamani GE, Amparore D, et al. ; Uro-technology and SoMe Working Group of the Young Academic Urologists Working Party of the European Association of Urology. Artificial intelligence and neural networks in urology: current clinical applications. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2020;72(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ting DSW, Pasquale LR, Peng L, et al. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(2):167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srivastava O, Tennant M, Grewal P, Rubin U, Seamone M. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in ophthalmology: a review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71(1):11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mwangi B, Wu MJ, Cao B, et al. Individualized prediction and clinical staging of bipolar disorders using neuroanatomical biomarkers. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1(2):186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noh SH, Cho PG, Kim KN, Kim SH, Shin DA. Artificial intelligence for neurosurgery: current state and future directions. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2023;66(2):113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martín-Noguerol T, Oñate Miranda M, Amrhein TJ, et al. The role of artificial intelligence in the assessment of the spine and spinal cord. Eur J Radiol. 2023;161:110726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoel B. Use of artificial intelligence in imaging in rheumatology – current status and future perspectives. RMD Open. 2020;6(1):e001063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Liu X, Xiao B, et al. Segmentation of organs-at-risk in cervical cancer CT images with a convolutional neural network. Phys Med. 2020;69:184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson FP, Shashaty M, Testani J, et al. Automated, electronic alerts for acute kidney injury: a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1966–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lykkegaard Andersen N, Brügmann A, Lelkaitis G, Nielsen S, Friis Lippert M, Vyberg M. Virtual double staining: a digital approach to immunohistochemical quantification of estrogen receptor protein in breast carcinoma specimens. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2018;26(9):620–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lancellotti C, Cancian P, Savevski V, et al. Artificial intelligence & tissue biomarkers: advantages, risks and perspectives for pathology. Cells. 2021;10(4):787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baxi V, Edwards R, Montalto M, Saha S. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence in translational medicine and clinical practice. Mod Pathol. 2022;35(1):23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakha EA, Toss M, Shiino S, et al. Current and future applications of artificial intelligence in pathology: a clinical perspective. J Clin Pathol. 2021;74(7):409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pantanowitz L, Quiroga-Garza GM, Bien L, et al. An artificial intelligence algorithm for prostate cancer diagnosis in whole slide images of core needle biopsies: a blinded clinical validation and deployment study. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(8):e407–e416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasuda Y, Tokunaga K, Koga T, et al. Computational analysis of morphological and molecular features in gastric cancer tissues. Cancer Med. 2020;9(6):2223–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sornapudi S, Stanley RJ, Stoecker WV, et al. Deep learning nuclei detection in digitized histology images by superpixels. J Pathol Inform. 2018;9(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nativ NI, Chen AI, Yarmush G, et al. Automated image analysis method for detecting and quantifying macrovesicular steatosis in hematoxylin and eosin–stained histology images of human livers. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(2):228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bui MM, Riben MW, Allison KH, et al. Quantitative image analysis of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 immunohistochemistry for breast cancer: guideline from the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143(10):1180–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahern TP, Beck AH, Rosner BA, et al. Continuous measurement of breast tumour hormone receptor expression: a comparison of two computational pathology platforms. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70(5):428–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali HR, Dariush A, Provenzano E, et al. Computational pathology of pre-treatment biopsies identifies lymphocyte density as a predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Courtiol P, Maussion C, Moarii M, et al. Deep learning-based classification of mesothelioma improves prediction of patient outcome. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1519–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng Q, Klein C, Caruso S, et al. Artificial intelligence predicts immune and inflammatory gene signatures directly from hepatocellular carcinoma histology. J Hepatol. 2022;77(1):116–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davison BA, Harrison SA, Cotter G, et al. Suboptimal reliability of liver biopsy evaluation has implications for randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol. 2020;73(6):1322–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le HD, Pflaum T, Labrenz J, et al. Interobserver reliability of the Nancy index for ulcerative colitis: an assessment of the practicability and ease of use in a single-centre real-world setting. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(3):389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganesan S, Madabhushi A, Basavanhally A, et al. Computerized histologic image-based risk score (IbRiS) classifier for ER+ breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24_Supplement):3046–3046. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pagès F, Mlecnik B, Marliot F, et al. International validation of the consensus immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet. 2018;391(10135):2128–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoque MZ, Keskinarkaus A, Nyberg P, Seppänen T. Stain normalization methods for histopathology image analysis: a comprehensive review and experimental comparison. Information Fusion. 2024;102:101997. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang F, Yao S, Li Z, et al. Predicting treatment response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in local advanced rectal cancer by biopsy digital pathology image features. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(2):e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wulczyn E, Steiner DF, Xu Z, et al. Deep learning-based survival prediction for multiple cancer types using histopathology images. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0233678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Janowczyk A, Zhou Y, et al. Prediction of recurrence in early stage non-small cell lung cancer using computer extracted nuclear features from digital H&E images. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Candemir S, Nguyen XV, Folio LR, Prevedello LM. Training strategies for radiology deep learning models in data-limited scenarios. Radiol Artif Intell. 2021;3(6):e210014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dolezal JM, Kochanny S, Dyer E, et al. Slideflow: deep learning for digital histopathology with real-time whole-slide visualization. BMC Bioinformatics. 2024;25(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy A, Knipe H, Chan B, et al. Imaging data sets (artificial intelligence). Radiopaedia.org; Accessed February 18, 2025. 10.53347/rID-68006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Sun K, Gao Y, Wang K, Yu G. Preparing data for artificial intelligence in pathology with clinical-grade performance. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(19):3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Russakovsky O, Deng J, Su H, et al. ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int J Comput Vis. 2015;115(3):211–252. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amaro Junior E. Artificial intelligence and big data in neurology. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022;80(5 suppl 1):342–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hashimoto DA, Rosman G, Rus D, Meireles OR. Artificial intelligence in surgery: promises and perils. Ann Surg. 2018;268(1):70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kueper JK, Emu M, Banbury M, et al. Artificial intelligence for family medicine research in Canada: current state and future directions: report of the CFPC AI working group. Can Fam Physician. 2024;70(3):161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baxter SL, Longhurst CA, Millen M, Sitapati AM, Tai-Seale M. Generative artificial intelligence responses to patient messages in the electronic health record: early lessons learned. JAMIA Open. 2024;7(2):ooae028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tse G, Lee Q, Chou OHI, et al. Healthcare big data in Hong Kong: development and implementation of artificial intelligence-enhanced predictive models for risk stratification. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49(1 Pt B):102168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong L, Shi W, Isgut M, et al. Integrating multi-omics data with EHR for precision medicine using advanced artificial intelligence. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2024;17:80–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bi WL, Hosny A, Schabath MB, et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(2):127–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin E, Lin CH, Lane HY. Precision psychiatry applications with pharmacogenomics: artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Z, Lin L, Wu C, Li C, Xu R, Sun Y. Artificial intelligence for assisting cancer diagnosis and treatment in the era of precision medicine. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41(11):1100–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wagner MW, Bilbily A, Beheshti M, Shammas A, Vali R. Artificial intelligence and radiomics in pediatric molecular imaging. Methods. 2021;188:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mutasa S, Sun S, Ha R. Understanding artificial intelligence based radiology studies: what is overfitting? Clin Imaging. 2020;65:96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hammond MEH, Stehlik J, Drakos SG, Kfoury AG. Bias in medicine. JACC: Basic Transl Sci. 2021;6(1):78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tizhoosh HR, Pantanowitz L. Artificial intelligence and digital pathology: challenges and opportunities. J Pathol Inform. 2018;9(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight — reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chin MH, Afsar-Manesh N, Bierman AS, et al. Guiding principles to address the impact of algorithm bias on racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2345050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo LN, Lee MS, Kassamali B, Mita C, Nambudiri VE. Bias in, bias out: underreporting and underrepresentation of diverse skin types in machine learning research for skin cancer detection—a scoping review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(1):157–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li K, Persaud D, Choudhary K, DeCost B, Greenwood M, Hattrick-Simpers J. Exploiting redundancy in large materials datasets for efficient machine learning with less data. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rudin C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat Mach Intell. 2019;1(5):206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.A S, R S. A systematic review of explainable artificial intelligence models and applications: recent developments and future trends. Decision Analytics Journal. 2023;7:100230. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gholi Zadeh Kharrat F, Gagne C, Lesage A, et al. Explainable artificial intelligence models for predicting risk of suicide using health administrative data in Quebec. PLoS One 2024;19(4):e0301117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goktas P, Karakaya G, Kalyoncu AF, Damadoglu E. Artificial intelligence chatbots in allergy and immunology practice: where have we been and where are we going? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(9):2697–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hashimoto DA, Witkowski E, Gao L, Meireles O, Rosman G. Artificial intelligence in anesthesiology: current techniques, clinical applications, and limitations. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(2):379–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitsala A, Tsalikidis C, Pitiakoudis M, Simopoulos C, Tsaroucha AK. Artificial intelligence in colorectal cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment. A new era. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(3):1581–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Young AT, Xiong M, Pfau J, Keiser MJ, Wei ML. Artificial intelligence in dermatology: a primer. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(8):1504–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hsu CC, Kao Y, Hsu CC, et al. Using artificial intelligence to predict adverse outcomes in emergency department patients with hyperglycemic crises in real time. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023;23(1):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okamoto T, Onda S, Yasuda J, Yanaga K, Suzuki N, Hattori A. Navigation surgery using an augmented reality for pancreatectomy. Dig Surg. 2015;32(2):117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muehlematter UJ, Daniore P, Vokinger KN. Approval of artificial intelligence and machine learning-based medical devices in the USA and Europe (2015–20): a comparative analysis. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(3):e195–e203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nomura A, Noguchi M, Kometani M, Furukawa K, Yoneda T. Artificial intelligence in current diabetes management and prediction. Curr Diab Rep. 2021;21(12):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsoi K, Yiu K, Lee H, et al. HOPE Asia Network. Applications of artificial intelligence for hypertension management. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23(3):568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prelaj A, Miskovic V, Zanitti M, et al. Artificial intelligence for predictive biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(1):29–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saigal K, Patel AB, Lucke-Wold B. Artificial intelligence and neurosurgery: tracking antiplatelet response patterns for endovascular intervention. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(10):1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nensa F, Demircioglu A, Rischpler C. Artificial intelligence in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 2019;60(Suppl 2):29S–37S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Papachristou K, Panagiotidis E, Makridou A, et al. Artificial intelligence in nuclear medicine physics and imaging. Hell J Nucl Med. 2023;26(1):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Elias KM, Fendler W, Stawiski K, et al. Diagnostic potential for a serum miRNA neural network for detection of ovarian cancer. elife. 2017;6:e28932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Galbusera F, Casaroli G, Bassani T. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in spine research. JOR Spine. 2019;2(1):e1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Niazi MKK, Parwani AV, Gurcan MN. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):e253–e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vishwanathaiah S, Fageeh HN, Khanagar SB, Maganur PC. Artificial intelligence its uses and application in pediatric dentistry: a review. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dhaliwal J, Walsh CM. Artificial intelligence in pediatric endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2023;33(2):291–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tao G, Yang S, Xu J, Wang L, Yang B. Global research trends and hotspots of artificial intelligence research in spinal cord neural injury and restoration—a bibliometrics and visualization analysis. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1361235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maita KC, Avila FR, Torres-Guzman RA, et al. The usefulness of artificial intelligence in breast reconstruction: a systematic review. Breast Cancer. 2024;31(4):562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barone M, De Bernardis R, Persichetti P. Artificial intelligence in plastic surgery: analysis of applications, perspectives, and psychological impact. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2025;49(5):1637–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yagi R, Goto S, Himeno Y, et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled prediction of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity from baseline electrocardiograms. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.El Sherbini A, Rosenson RS, Al Rifai M, et al. Artificial intelligence in preventive cardiology. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;84:76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Anan T, Kajiki S, Oka H, et al. Effects of an artificial intelligence-assisted health program on workers with neck/shoulder pain/stiffness and low back pain: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(9):e27535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pham KT, Nabizadeh A, Selek S. Artificial intelligence and chatbots in psychiatry. Psychiatr Q. 2022;93(1):249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Graham S, Depp C, Lee EE, et al. Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: an overview. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(11):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Alizadeh M, Tanwar M, Sarrami AH, Shahidi R, Singhal A, Sotoudeh H. Radiomics; a potential next “omics” in psychiatric disorders; an introduction. Psychiatry Investig. 2023;20(7):583–592. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sarkar C, Das B, Rawat VS, et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning technology driven modern drug discovery and development. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Takagi Y, Nishimoto S. High-resolution image reconstruction with latent diffusion models from human brain activity. 2022. 10.1101/2022.11.18.517004. [DOI]

- 106.Desai SB, Pareek A, Lungren MP. Current and emerging artificial intelligence applications for pediatric interventional radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 2022;52(11):2173–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen Z, Zhang Y, Yan Z, et al. Artificial intelligence assisted display in thoracic surgery: development and possibilities. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(12):6994–7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Etienne H, Hamdi S, Le Roux M, et al. Artificial intelligence in thoracic surgery: past, present, perspective and limits. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(157):200010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shah M, Naik N, Somani BK, Hameed BZ. Artificial intelligence (AI) in urology-current use and future directions: an iTRUE study. Turk J Urol. 2020;46(Supp 1):S27–S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]