Abstract

Introduction

Improving health, in particular of people in a disadvantaged socioeconomic position (SEP), requires multilevel health promotion programmes with community engagement. However, the impacts of such complex and challenging programmes are not yet clear. This study aims to show the impact of a participatory multilevel family health promotion programme in a low-income neighbourhood at intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy level.

Methods

A mixed-methods design was used to monitor and assess output and outcome realisation by parents and professionals from multiple sectors in a 4-year programme. Output realisation was monitored and reported half-yearly. Parents’ knowledge, parent and child health (behaviours), social support and perceived neighbourhood child friendliness were measured through a cohort study in three successive years.

Results

Changes found: Multiple activities were implemented, such as swimming lessons free of charge for children in low-income families. Parents’ assessment of neighbourhood child friendliness increased significantly as well as their knowledge about financial, social and healthy diet support, particularly among parents (n=13) who had been actively engaged in the programme. Social support decreased significantly. Municipal policies addressed more of the needs of people in a disadvantaged SEP, such as low-cost sports possibilities.

Conclusion

This study revealed multilevel impacts of the programme: health-enabling activities for low-income families were realised, used and sustained at the organisational and policy level, which focused on contributing to neighbourhood child friendliness (community level). The engaged stakeholders took steps on the long pathway towards improved parent and child health in a disadvantaged SEP (intrapersonal level). Constant stakeholder investment is needed at all levels in the community and at the national policy level.

Trial registration number

Netherlands Trial Register (NL7738) Marissa Traets

Keywords: Public Health, Community Health, Qualitative Research

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Improving the health of families in a disadvantaged socioeconomic position (SEP) requires multilevel health promotion programmes with community engagement; however, few publications report on the impact of such complex programmes.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Insight into the impact of a multilevel participatory health promotion programme on children, parents (including parents in a disadvantaged SEP and actively engaged parents), interpersonal support of parents, the neighbourhood, organisations and municipal policy

Insight into the way the evaluation of a programme can be described in terms of desired output and outcome changes, as formulated with parents in a disadvantaged SEP and professionals in policy and practice in multiple sectors

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Coordinated community action of parents in a disadvantaged SEP and professionals in municipal policy and practice in multiple sectors can benefit actively engaged parents (knowledge, use of health-enabling activities, support in finding paid and voluntary work), and can result in sustained health-enabling activities for families in a disadvantaged SEP.

Programme monitoring and the cohort study were time-intensive methods. Researchers, who want to assess the impact of a four-year multilevel participatory health promotion programme, best spend their time on monitoring and measuring outputs and initial outcomes with those actively involved.

Introduction

Worldwide, socioeconomic differences in health persist,1,4 meaning that the more socially and economically disadvantaged groups are, the poorer their health.5 In socio-ecological theory, health is viewed as a function of individuals and their environment.4 6 7 As health is influenced by factors at intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy levels,8,10 these factors need to be addressed comprehensively to promote health6 11 and enable people to increase control over, and improve, their health.12 Health promotion, therefore, should go beyond individual healthy lifestyles and address barriers to health and an infrastructure that can implement activities.13 14 This requires coordinated action from the whole community – the municipality, healthcare, social welfare, voluntary organisations and inhabitants.12 Understanding and influencing interacting factors4 in a specific community requires the engagement of all stakeholders,15 16 including people in a disadvantaged socioeconomic position (SEP).17 18

The impact of such community action at the the intrapersonal level (individual health and behaviours) is often evaluated, finding modest short-term effects,19,21 but little insight exists on the impact of such action on the other interpersonal, organisational, community and policy levels for improving the health of people in a disadvantaged SEP.15 22 23 Few publications report on the impact of participatory family health programmes.24

Our study investigated the impact of such a family health promotion plan, the TNW programme4 on the organisational, social and policy levels. The programme plan was developed with community stakeholders, including parents in a disadvantaged SEP.4 These insights as well as the way we evaluated such a complex multilevel programme can be of use in the development of future public health programmes.

Methods

Study context: the programme

The programme, Together Northern Wijchen (TNW, 2015–2019), was based in a relatively low-income neighbourhood in Wijchen Municipality, the Netherlands. Of this neighbourhood’s 14 935 inhabitants, 13% had a migrant background; 21% of 12 000 adults could be considered disadvantaged by low income and education (online supplemental appendix 1), and 400 of these adults in a disadvantaged position lived in a household with a child–the programme’s main target population.25 24% of the children of parents with a low income received professional psycho-social support.25 To prevent stigma, the programme publicly engaged all households with children.

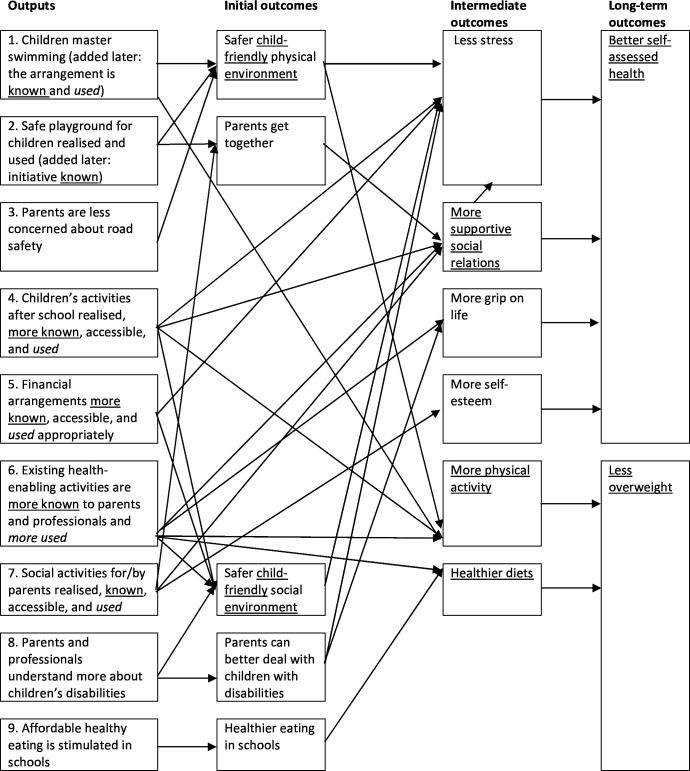

All stakeholders, neighbourhood parents, professionals and researchers jointly developed the TNW programme with the aim of improving the health of disadvantaged families.4 In an iterative participatory process26 in 6 months, funded by the private Dutch foundation Fund NutsOhra (FNO), they developed an intervention logic that visualises the hypothesised pathways of outputs to desired outcomes.11 27 28 The intervention logic integrated epidemiological data, literature and the priorities of parents in a disadvantaged SEP, professionals and FNO, as well as the changes (outputs) in which stakeholders were willing to invest4 (figure 1). After the first 6 months, FNO granted funding for another 42 months, in which activities were developed, implemented and evaluated (figure 2). A participatory approach was applied, as this is known as a practical approach to investigate problems among diverse stakeholder groups where asymmetries of skills and power may exist. As such, it provides a valuable approach for meaningful and equal participation in programmes and research.29 The programme staff, skilled facilitators (GW and social worker), tried to ensure all voices were heard30 in meetings. A board of policy and management professionals provided advice each half-year. A description of involved parents and professionals is provided in online supplemental appendix 2.

Figure 1. Intervention logic: hypothesised pathways to desired outcomes4 Underlined=measured in a cohort study. Italics=monitored.

Figure 2. Time path community-based participatory activities (48 months). The focus of this study in grey boxes: programme monitoring (♦ = analysed documents) and cohort study. SEP, socioeconomic position.

Patient and public involvement

Parents and professionals were actively engaged in the developing and implementing of the programme through a participatory action approach. They also informed us which activities to include in the monitoring of activity use. Although no patient and public involvement was applied in the design and data gathering of this particular study, the results were shared in graphically designed factsheets and discussed with the collaborating parents and professionals in workgroups, in advisory board meetings and in the programme’s end meeting. In the end meeting, both researchers and parents presented programme results.

Study design

This mixed methods study has a convergent design—parallel-databases variant.31 For a more comprehensive understanding, programme impacts were assessed with qualitative programme monitoring and a quantitative cohort study.31 32 Data were collected and analysed separately, and subsequently the two sets of results were synthesised and compared in the discussion31 through several meetings with the team of authors.

Programme monitoring

Programme monitoring enables programme stakeholders’ learning, and accountability needs to be met33 and might explain changes in outputs and outcomes. Monitoring activities included (1) monitoring output realisation and (2) monitoring the use of activities by parents and children as planned outputs.

Output realisation means realised activities, such as affordable swimming lessons, to achieve the desired output, for example, that children master swimming. Output realisation was monitored by GW’s updating workplans and her written progress reports, half-yearly, based on observations and reflections in workgroup meetings. Meeting participants gave informed consent to reporting without their names. To monitor planned outputs, a researcher (PP) annually asked seven activity providers of 22 health-enabling activities about the number of users. Providers were included if they were willing to report the use of activities, activities were accessible to people with a low income and open for new participants, and activities were intended to be provided long term. Activity providers gave informed consent. Finally, the documents marked with a diamond in figure 2 were analysed on realised planned and unplanned outputs. The results are summarised in box 1.

Cohort study

To measure changes in outputs and outcomes over time34 the cohort study consisted of three questionnaires with parents in the second, third and last programme year.

Study population: Cohort inclusion criteria in 2017 were as follows: parent/carer in a household with a child between 4 and 13 years of age and living in the neighbourhood. The latter measurement included respondents who had moved away from the area but had lived there for more than 1.5 years and participated in the 2017 questionnaire. The six interviewers deployed several complementary strategies for parent recruitment: letters to 1251 parents through school, letters and personal visits to 364 home addresses, a Facebook (paid) campaign (invitation, 4962 views), a personal approach via adult literacy education and refugee work. In all 3 years, the cohort invitees were informed that participation is voluntary and that their personal data would be safely stored. Contact information of an independent researcher was provided for complaints. Answering questions on children under 16 only required permission of the parent (personal data protection law, 2000). All respondents gave informed consent to participate.

In 2018 and 2019, the interviewers invited the 2017 parent respondents to participate by phone, e-mail and some additionally by Facebook messenger or home visits. Recruitment periods were 8–10 weeks in March/April/May of 2017, 2018 and 2019. Parents who completed the questionnaire received €10 cash in 2017 and again in 2019 for each completed questionnaire. Interested parents received information on health-enabling activities in 2018.

Data collection: The questionnaires contained validated questions from the existing Municipal Health Service (MHS) Monitor, complemented by questions added by our stakeholders, based on the intervention logic (figure 1). In 2017, outcome-related variables were measured: neighbourhood child friendliness, supportive social relations, physical activity, healthy diet, self-assessed health and weight. In 2018, the output variable, parents’ knowledge of activities, was measured. In 2019, the questionnaire contained both 2017 and 2018 questions. Parents answered questions on the child whose birthday was closest to the response date in 2017 and in 2019 on the same child.

The Radboudumc surveys programme (ELGsurveys) was used to build the questionnaires. Where possible, the MHS Monitor’s validated questions were used, and, if necessary, new questions (not validated) were added. The questionnaire was pretested with six parents in 2017 and three in 2018. Interviewers received a half-day’s training and an interviewer handbook compiled specifically for the questionnaires.35

Parents could choose to respond online or face-to-face to an interviewer with a tablet (2017 and 2019) and by telephone (2018), thus enabling the inclusion of parents with low (computer) literacy. Online respondents received a link to the questionnaire by e-mail. The face-to-face interview took around 45 min and the telephone interview about 10 minutes (only on knowledge of activities).

Data analysis

Parents’ assessment of the neighbourhood’s child-friendliness was chosen as a primary outcome measure as this initial outcome (comprising a safer child-friendly social and physical environment) related to seven of the nine planned outputs in the intervention logic. The sample size calculation was based on a 0.5-point change in parents’ assessment (10-point scale). With α set at 0.05 (two-tailed), a power of 0.80 and a SD of 1.5 (assumed), a total number of 73 parent respondents were needed (G*Power). Assuming a 50% dropout rate,35 the aim was to include 146 parents. The advisory board considered a 0.5 point change a relevant outcome. This means an effect size of 0.33, in between a small and medium effect size according to Cohen’s definition.36

SPSS Statistics V. 22 was used for analysis. A Levene’s test in 2017 showed homogeneity of variance in the online and the oral respondents’ datasets (p=0.477, α=0.05): the data-collection method did not influence results. Various tests (parametric paired two-tailed t-test, non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test, McNemar test, and Cochran’s Q exact test) were used to analyse the statistical significance of output and outcome variable changes over the years in our (sub)samples.

The online supplemental table presents the characteristics of parents who completed the questionnaire in 2017 and at least one of the follow-up measurements. Of the 124 parents who completed the questionnaire in 2017, 14 parents’ data were excluded because they completed only the 2017 questionnaire, did not want to participate again, moved, could not be contacted or did not answer all questions online. Output-related (table 1) and outcome-related variables (table 2) were analysed for all participating parents, for parents in a low SEP, and for active parents, ie, parents who engaged actively in one or more programme workgroups. Results for active parents were analysed separately, as they likely had more exposure to the programme than other neighbourhood parents. STROBE cohort reporting guidelines were used.37

Table 1. Parents’ knowledge of health-enabling activities, arrangements and organisations.

| Health-enabling activities in the neighbourhood, below the outputs as described in the intervention logic | % parents that know the activity | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Children master swimming (planned output 1) | ||||

| Municipal arrangement for free swimming lessons for children from low-income families | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 63 | 81 | 0.002 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 82 | 82 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 92 | 100 | 1.000 | |

| Safe playground for children (0–12 years) realised and used (planned output 2) | ||||

| Weijkpark Foundation | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 60 | 54 | 0.286 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 53 | 53 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 92 | 92 | 1.000 | |

| Children’s activities after school realised, more known, and accessible (planned output 4) | ||||

| SNA’s child activities in the community centre | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 69 | 74 | 0.458 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 53 | 71 | 0.453 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 77 | 92 | 0.625 | |

| Financial arrangements more known and accessible (planned output 5) | ||||

| Administration and forms support team for adults | ||||

| All parents (n=96) | 12 | 23 | 44 | 0.000 |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 12 | 35 | 41 | 0.050 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 8 | 54 | 46 | 0.011 |

| Municipal child arrangement for, eg, sports lessons/clothing or computer | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 80 | 88 | 0.189 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 94 | 94 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 92 | 100 | 1.000 | |

| Overview of financial arrangements on municipal website | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 31 | 57 | 64 | 0.000 |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 53 | 82 | 77 | 0.093 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 54 | 100 | 85 | 0.033 |

| Municipal adult arrangement for, eg, sports/social activities | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 46 | 50 | 0.678 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 77 | 77 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 69 | 85 | 0.500 | |

| Vincentius (church-related) financial support | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 26 | 41 | 0.003 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 35 | 53 | 0.250 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 69 | 62 | 1.000 | |

| Support for informal care providers | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 44 | 46 | 0.839 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 53 | 53 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 46 | 85 | 0.063 | |

| Existing health-enabling activities more known to parents and professionals (planned output 6) | ||||

| Walk-in social team | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 50 | 72 | 0.001 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 82 | 82 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 77 | 85 | 1.000 | |

| Programme Facebook page | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 41 | 45 | 0.556 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 59 | 53 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 85 | 100 | 0.500 | |

| The possibility for parent and child to engage in sport simultaneously | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 43 | 46 | 0.728 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 41 | 41 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 92 | 85 | 1.000 | |

| Dietician advice for adults (3 hours/year, free if out-of-pocket costs max. reached) | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 25 | 38 | 0.037 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 18 | 53 | 0.070 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 8 | 54 | 0.031 | |

| Dietician advice for children (3 hours/year free from out-of-pocket costs) | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 7 | 32 | 0.000 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 6 | 47 | 0.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 8 | 62 | 0.016 | |

| Combined lifestyle (healthy diet, physical activity, behaviour change) support for healthy weight for children | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 13 | 22 | 0.152 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 12 | 25 | 0.219 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 15 | 46 | 0.219 | |

| Website: advice for a healthy upbringing | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 10 | 20 | 0.035 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 12 | 35 | 0.125 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 23 | 39 | 0.500 | |

| Website: healthy agreements with your child | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 9 | 17 | 0.167 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 6 | 24 | 0.250 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 15 | 39 | 0.250 | |

| Facebook page on affordable healthy eating in Wijchen | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 16 | 29 | 0.002 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 24 | 35 | 0.500 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 62 | 92 | 0.125 | |

| Social activities for/by parents realised, known, and accessible (planned output 7) | ||||

| Social eating activities for adults in community centres | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 61 | 65 | 0.541 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 71 | 71 | 1.000 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 92 | 92 | 1.000 | |

| Parents and professionals understand more about children’s disabilities (planned output 8) | ||||

| Autism workgroup WAUW | ||||

| All parents (n=97) | 37 | 45 | 0.096 | |

| In a low SEP (n=17) | 24 | 41 | 0.375 | |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 62 | 62 | 1.000 | |

Statistically significant differences<0.05 bold.

Cohort study results of all parents and subgroups in a low SEP and active in workgroup(s).

SEP, socioeconomic position.

Table 2. Outcomes as described in the intervention logic.

| Cohort study variables, structured below the programme objectives as described in the intervention logic | 2017 | 2019 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Safer child-friendly physical and social environment (initial objective)

| |||

| Child friendliness of the neighbourhood mean assessment (10-point scale) | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 7.2 (1.4) | 7.6 (1.5) | 0.003 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 7.3 (1.3) | 7.4 (2.1) | 0.159 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 6.4 (1.8) | 6.6 (1.9) | 0.109 |

| More supportive social relations (intermediate objective) | |||

| Parents receiving a listening ear of another adult often or regularly | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 72% | 68% | 0.556 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 63% | 53% | 0.727 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 57% | 50% | 1.000 |

| Parents being asked by another adult to join an activity often or regularly | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 69% | 56% | 0.026 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 42% | 42% | 1.000 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 57% | 43% | 0.625 |

| Parents (totally) agreeing that people in the neighbourhood accept them as they are | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 75% | 75% | 1.000 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 58% | 37% | 0.125 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 64% | 64% | 1.000 |

| People in the neighbourhood accept my child as it is, parent-assessed (10-point scale, totally disagree–totally agree) | |||

| All parents (n=103) | 8.5 (1.5) | 8.4 (1.7) | 0.458 |

| In a low SEP (n=18) | 8.6 (1.3) | 8.6 (1.8) | 0.615 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 8.3 (2.6) | 7.6 (2.6) | 0.291 |

| I can talk with other adults about difficult situations with my child (10-point scale, totally disagree–totally agree) | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 8.4 (1.7) | 8.1 (2.0) | 0.072 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 7.8 (2.3) | 7.3 (2.6) | 0.408 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 9.1 (1.1) | 7.4 (3.0) | 0.028 |

| More physical activity (intermediate objective) | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 75% | 81% | 0.307 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 53% | 68% | 0.453 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 50% | 64% | 0.625 |

| Parents that do not engage in sport | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 52% | 50% | 0.839 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 79% | 74% | 1.000 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 57% | 64% | 1.000 |

| Parents that attain the Dutch healthy physical activity norm | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 37% | 42% | 0.327 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 16% | 21% | 1.000 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 43% | 43% | 1.000 |

| Healthier diets (intermediate objective) | |||

| Parents that eat fruit everyday | |||

| All parents (n=102) | 36% | 33% | 0.664 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 37% | 26% | 0.625 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 62% | 39% | 0.250 |

| Children that eat fruit everyday | |||

| All children (n=103) | 52% | 48% | 0.302 |

| In a low SEP (n=18) | 44% | 56% | 0.500 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 71% | 79% | 1.000 |

| Parents that eat vegetables everyday | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 43% | 38% | 0.345 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 21% | 37% | 0.375 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 71% | 43% | 0.125 |

| Children that eat vegetables everyday | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 40% | 39% | 1.000 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 16% | 42% | 0.063 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 57% | 64% | 1.000 |

| Parents that eat breakfast every day | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 83% | 86% | 0.549 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 58% | 74% | 0.250 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 71% | 79% | 1.000 |

| Children that eat breakfast everyday | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 94% | 92% | 0.727 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 90% | 95% | 1.000 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 93% | 100% | 1.000 |

| Parents that eat a hot meal everyday | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 92% | 88% | 0.267 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 90% | 90% | 1.000 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 93% | 93% | 1.000 |

| Children that drink sweet drinks everyday | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 64% | 57% | 0.201 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 58% | 47% | 0.625 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 71% | 57% | 0.500 |

| Better self-assessed health (long-term objective) | |||

| Parent health, mean self-assessment (10-point scale) | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 7.5 (1.2) | 7.7 (1.1) | 0.137 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 6.5 (1.7) | 7.1 (1.2) | 0.351 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 7.1 (0.7) | 7.3 (1.2) | 0.725 |

| Child health, mean parent assessment (10-point scale) | |||

| All parents (n=104) | 8.2 (1.3) | 8.4 (1.2) | 0.454 |

| In a low SEP (n=19) | 7.6 (1.7) | 8.4 (1.6) | 0.099 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=14) | 7.9 (1.6) | 7.7 (1.9) | 0.843 |

| Overweight (long-term objective) | |||

| Parents with (severe) overweight (BMI>25) | |||

| All parents (n=92) | 48% | 52% | 0.344 |

| In a low SEP (n=18) | 39% | 44% | 1.000 |

| Active in a workgroup (n=13) | 62% | 69% | 1.000 |

Statistically significant differences<0.05 bold. Values have been reported as mean (SD) or as %.

Cohort study results of all parents and subgroups in a low SEP and active in workgroup(s).

SEP, socioeconomic position.

Results

A total of 110 parents completed the questionnaire in 2017 and in either 2018 or 2019, or both years (online supplemental table). Of these, 104 were women, the mean age was 40 (SD 6.25), 100 were born in the Netherlands, 19% were in a low SEP in 2017 (operationalisation of a low, middle and high SEP is provided in online supplemental appendix 1), and 14 had been active in a programme workgroup. Of these 14 active parents, 5 were in a low SEP, 6 in a middle SEP and 3 in a high SEP in 2017.

Active parents and professionals from multiple organisations collaborated on output realisation (Box 1). They realised multiple activities enabling child health in the neighbourhood, such as free swimming lessons for children from low-income families (output 1) and a foundation for the development of a playground (output 2). They also realised communication and publicity on available financial support and a support team of trained volunteers to assist parents and other adults with administration and application forms for financial support. The number of monthly requests for this team’s support doubled during the programme period. The annual use of municipal financial support for child-activity participation increased from 67 children in the first year to 343 in the third (output 5).

Box 1. Outputs planned in July 2016 and outputs realised in 2019.

Planned output 1. In 2019, children in low-income families can obtain a basic certificate for swimming

Realised outputs

Active parents found charity funding for swimming lessons for three of their children (2016)

Municipality embeds free swimming lessons (for 6- to 11-year-old children) in their child arrangement, aided by a one-time national government subsidy to municipalities for opportunities for all children. From the start in 2017 to July 2019, 94 children from low-income families participated (ongoing in 2019)♥

Planned output 2. In 2019, at least one safe playground for children (0–12) is realised and used by parents and children

Realised outputs

Weijkpark Foundation for playground development established (May 2017, ongoing in 2019)♥

Publicity on Weijkpark Foundation and playground dream: 3D playground model revealed, own Facebook page, resident information flyer and evening, film, overview of low-cost family activities and articles in local free paper

Support for playground development from municipal policy advisor (funding, inspection and maintenance), province, welfare organisation (hours), other funders, residents and parents (2019)♥

Planned output 3. In 2019, road safety for children at three unsafe spots was improved according to parents

Realised outputs

Five unsafe road spots were identified by parents and advice for improvement was provided to the municipality (in 2017), which saw no substantiation for follow-up because no accidents were reported to the police and suggested changes did not align with policy

Other proposed road safety actions lacked support of parents, schools and other professionals

Planned output 4. In 2019, more families knew and used (social, sports, creative) after-school activities for children, and when needed, additional activities were developed

Realised outputs

Three children of active parents started participating in existing child activities in the community centre organised by the Social Neighbourhood Association (SNA).

The number of registrations (not unique users) for the 15 child activities organised by SNA ranged from 55 in 2016 to 84 in 2017. According to SNA, the seeming increase in registrations over the years is caused by the familiar kids participating in more SNA activities. In 2018, sports clubs offered free sports activities, causing a lower number of 59 registrations for SNA activities that year.

14 children participated in a cupcake workshop (developed by programme, parent and SNA in 2019)♥

Planned output 5. In 2019, more parents knew and used arrangements for financial support and for grip on finances

Realised outputs

Administration and forms support team became available for adults (February 2017). Volunteers in the team were trained, and support for volunteers was embedded in the welfare organisation (ongoing in 2019)♥ Use increased from on average two to three monthly requests (February–November 2017) to five (2018–May 2019).

Municipal poverty policy includes workgroup suggestions on publicity (2017) and a 10% higher income norm for municipal financial support (2018).

Placemat with possibilities/support from MHS policy advisor for people with a small budget.

Information on municipal financial child arrangement included a free try-out sports activities booklet.

The number of children and adults living in low-income households using the municipal arrangements for social/sports participation increased from 67 and 330 in 2016 to 343 and 367, respectively, in 2018.

Getting-by-day information market by 23 organisations (35–40 visiting families). Spin-off: budget training (five participants) (ongoing in 2019).

Planned output 6. In 2019, more parents and professionals knew existing health-enabling activities, more professionals could guide to these activities, and more parents and children used these activities

Realised outputs

Overview of financially supportive and low-cost healthy family activities widely shared with parents (through primary schools) and professionals, eight articles on these activities in local free paper.

Inspiration meeting and factsheet for activity providers on reaching (low-income) families.

Planned output 7. In 2019, at least two additional regular social activities for and by parents were realised, known and used.

Realised outputs

A neighbourhood breakfast (monthly since March 2017, bimonthly since November 2018) visited by three to eight parents (including one to seven organising parents, at the start more than by the end as some parents conflicted) and visited by 9–30 (frail) elderly (2017, ongoing in 2019)♥

Weekly handcraft group parent leadership (since September 2016)♥, led by one parent, embedded in SNA activity programme and used by one other parent and four to seven elderly (2016, ongoing in 2019)

Social low-cost physical activity group embedded in lifestyle centre but stopped by lack of participants (six parents, 2019)

Parent became voluntary host at lifestyle centre (2018, ongoing in 2019)♥

Parents became buddies (four in 2018, five in 2019)

Programme workgroup and celebration meetings with parents (72 meetings in 2016–2017, 40 in 2018–2019). Parents received a volunteer fee of €4.50/hour /hour for participation

Programme Facebook page, friends in 2019: 27 parents and 108 others, eg, alderman

Planned output 8. In 2019, parents and other people in children’s environment were better able to deal with children with a (psychosocial) disability

Realised outputs

Parent initiative Workgroup Autism Wijchen (WAUW) (2015) became a foundation for an autism-friendly community, supported by social professionals on request (ongoing in 2019)♥

WAUW organises multiple activities for people dealing with autism themselves/in their social environment: a low-stimulus time slot at a yearly fair, a peer group for parents with a child with autism (five meetings/year), a pub evening for parents of adolescents with(out) autism, an informative Facebook page, family meet-up days, handout of a (national) report on ‘Appropriate education from an autism perspective’ to schools, social and care professionals (2015, ongoing in 2019)♥

Planned output 9. In 2019, at least two additional programme activities, aimed at healthier diet policy or healthy school environment, in at least two primary schools, have been organised

Revised output: In 2019, at least two additional programme activities have been organised aimed at affordable healthy eating

Realised outputs

Programme found insufficient support of parents and school professionals for additional healthy diet activities at primary schools, of professionals for a supermarket safari, of parents/toddlers for cooking with toddlers, and of managers and policy advisors for activities without parent support.

Facebook Page on affordable healthy eating in Wijchen, initiated in 2017, 103 friends in 2018 and 117 in 2019 (contact with dietician on continuing page management ongoing in 2019)

‘Cooking with teens’ (affordable) activity organised monthly and embedded in SNA activity programme (five teens in 2018–2019, ongoing in 2019)

Unplanned outputs

Based on this, MHS developed and implemented other co-creation activities with inhabitants and welfare workers: a support group with and for (former) adult literacy education students (2018, ongoing in 2019)♥ and a health programme in another region (2018–2022)

Municipal sports policy includes attention on sports possibilities for people with a low income (2018)

A parent started voluntary work as host after the example of her friend, lifestyle centre host (2019)

Parents’ workgroup experiences helped at least three parents build curriculum vitae and get jobs (2017–2019)

♥Activity ongoing in 2024, based on continued contacts with activity providers.

Active parents, the MHS, the Welfare Organisation and the Social Neighbourhood Association (SNA) also realised social activities: a weekly handcraft group, a bimonthly social neighbourhood breakfast, a monthly cooking workshop with teens, and parents became buddies and hosts of other inhabitants (output 7).

All realised outputs were supported by active parents as well as professionals, including managers and municipal policy advisors. These stakeholders did not support improved road safety and a healthier diet policy or school environment; consequently, these outputs (3 and 9) were not realised. Municipal policies addressed more of the needs of people in a disadvantaged SEP, such as free swimming lessons and low-cost sports possibilities, making health-enabling activities more accessible, as planned. Unplanned positive outputs included involved professionals’ and parents’ programme experiences supporting the development and uptake of new activities, such as a support group for (former) adult literacy education students and voluntary/paid work by active parents.

In the last programme year, compared with preceding programme years, significantly more parents knew about the swimming arrangement, the overview of financial arrangements on the municipal website, the support team for administration and application forms, church-related financial support, the walk-in social team, the dietician advice and related costs for children and adults, the Facebook page on affordable healthy eating in Wijchen and the website with advice for healthy upbringing (table 1).

Active parents’ (n=13) knowledge increased significantly on the municipal website’s overview of financial arrangements, the support team for administration and application forms, and the dietician advice and related costs for children and adults. Remarkably, in the last programme year, most activities were known among active parents; some activities were even known by all active parents.

A significant increase was also found in the number of parents in a low SEP (n=17) who indicated that they knew about the possibility for free dietary advice for children.

A significant increase over time was found on the primary outcome mean parent assessment of child-friendliness of the neighbourhood (10-point scale): from 7.2 to 7.6 (table 2). No significant improvements were found in supportive social relations, physical activity and healthy diets, self-assessed health, and parent and child overweight. A significant decrease was seen in the percentage of parents who indicated that they were often or regularly asked by another adult to join an activity.

No significant outcome improvements among active parents (n=14) were found. A significant decrease was seen in the extent to which active parents agreed (10-point scale) that they could talk with other adults about difficult situations with their child in the last two programme years. Remarkably, active parents scored higher on this item than all parents (9.1 vs 8.4) in the second programme year and lower than all parents (7.3 vs 8.1) in the last year.

No significant outcome changes were found for parents in a low SEP (n=19).

Discussion

This study aimed to show the impacts of a participatory family health promotion programme in a low-income neighbourhood at multiple levels through monitoring output realisation and the use of activities and through a cohort study consisting of three questionnaires with parents in three successive years. These combined methods resulted in expected and unexpected outputs and outcomes and were differentiated based on data from all parents, for parents in a low SEP and for parents who were active in programme workgroup(s), the active parents.

As expected, as part of the programme, several health-enabling community activities were realised by active parents and professionals’ joint efforts. Typically, these activities were affordable and accessible, enabled social contacts and aligned with what parents in a low SEP in this neighbourhood prioritised for reducing chronic stress.4 Consequently, parents got together in programme meetings. Support by active parents as well as professionals, including managers and municipal policy advisors, turned out to be of vital importance for the realised outputs. For the outputs that were not realised during implementation, this support appeared to be less than expected during programme planning due to multiple factors. Examples of programme outputs include 94 children participating in the free swimming lessons for children from low-income families and the doubling of requests to the administration and forms support team. These free swimming lessons and the administration support team became part of policy. Parents’ knowledge about activities for financial, social and healthy diet support in the neighbourhood increased significantly and was highest among the active parents. Overall, parents’ assessment of neighbourhood child friendliness increased significantly.

As also expected, there were no significant changes in long-term health outcomes on self-assessed health and overweight. Reaching these outcomes requires a longer period and probably a higher intensity of activities focused on health behaviours.38,41 To realise this, support by a comprehensive multisector policy strategy focused on people in a disadvantaged position is a prerequisite.42 Health equity is ultimately influenced by structural factors, including macroeconomic, social and public policies.43 44 In the studied programme, power, a social determinant of health (SDOH),45 was shared by planning programme outputs and outcomes with parents and professionals, by facilitating hearing their voices in workgroup meetings and by reflecting together to strengthen their capacity to reach and sustain desired changes. Many of the desired changes related to root causes of health inequities, and the people in the workgroups addressed various aspects of SDOH,43 45 46 such as accessibility of resources, physical environment, leisure opportunities and financial stability.

Significant unexpected decreases were found in parents’ assessment of social support from other adults. Over the three measurements, parents were less frequently asked by other adults to join an activity. We do not have an explanation for this decrease, and this would require further research, in dialogue with these parents. Also, there was a significant decrease in the number of active parents who talked with other adults about difficult situations related to their children. An explanation might be that the number of meetings chaired by programme staff also decreased: 72 in 2016–2017 to 40 in 2018–2019. In addition, later meetings were no longer chaired by programme staff, and a few parents came into conflict with one another, resulting in their withdrawal from meetings. A closer look at the data of active parents, related to this social support item, revealed: 2 of the 14 active parents assessed this seven points lower in 2019 compared with 2017 (explaining the SD of 3.0, see table 2). These two parents both conflicted with another parent in the active parents group, supporting our possible explanation. De Hernandez et al also report that interpersonal dynamics among women of a community group challenged sustaining this group.47 This supports the suggestion of De Groot et al for a facilitator to support a group of parents living in poverty to understand one another, as, in the words of one parent, ‘in a survival mode it is hard to bring up empathy for the other’.48

Other unplanned outputs included parents feeling supported by the programme in finding work and more health-enabling activities being developed in co-creation by inhabitants and professionals; this also led to an online handbook for health promotion professionals.49 Also, several activities were sustained and – at time of writing – still in place (Box 1), eg, the free swimming lessons and the playground that opened in 2021 as a result of organisational and municipal policy changes triggered by the programme.

This study found (statistically significant) changes in terms of outcomes and outputs at intrapersonal to local policy level. Our findings are in line with other community-based studies in which researchers collaborate with stakeholders: benefits for individuals, communities, organisations and policy development, as well as spin-off activities and programme extension.50 51 The community–academic partnership models of Zimmerman et al52 and Ortiz et al53 also include impact on the academic field and the university, but these impacts were not the focus of this study. Similar participatory, multilevel programmes will likely yield similar programme effects on multiple levels, though (sustained) activities will be context specific.

Strengths and limitations

This mixed-method study resulted in a comprehensive insight into (un)expected programme impacts on multiple levels. Programme monitoring provided insight into changes at organisational, community and municipal policy level, and the cohort study into changes at intrapersonal, interpersonal and community level.

Both the cohort study and programme monitoring consisted of self-reported data, which is inherently biased. Progress reports were written by the main author, reviewed by the advisory board, and sent to the funder, which might have led to a positive bias.

Although programme monitoring consisted of both reporting programme progress half-yearly and regularly interviewing activity providers, perhaps not all activities and policy changes have been listed. As the researchers still have regular contact with the activity providers, the results could be supplemented and updated continuously. In addition, monitoring made the results visible in small steps and at multiple levels, and this was meaningful and stimulating for stakeholders to continue investing.

The number of survey respondents remained high; the 11% drop-out in the third measurement is low compared with other studies, eg, 35%.54 Many parents responded multiple times to the survey, thanks to the tailored, intensive and varying recruitment strategies. The personal Facebook messages, in particular, helped to find, invite and remind parents to respond.

The number of parent respondents in a low SEP, the main target population, did not meet the power calculation requirements to find a relevant change in the primary outcome, but the number of all parents did. Of all 110 respondents, only six were men. Parents in a low SEP were well represented (19% in the cohort study, 21% in the neighbourhood25). As all parents also included 14 active parents, and cohort respondents received information on activities on request, the findings on parents in the cohort study cannot be generalised to all parents in the neighbourhood.

Overall, this study showed statistically significant changes in outputs and outcomes. However, no doubt there are multiple confounding factors in this multilevel, multi-actor and multi-year programme. This study did not focus on all these factors, which is one of the reasons we did not analyse the associations of variables. For instance, the increased Dutch attention on child-friendly public spaces55 was likely an influencing factor, with the result that the number of parents who assessed their neighbourhood as very child-friendly increased in all municipalities in the region during the time of the study.56 However, specific programme activities like the free swimming lessons likely contributed to physical activity and social inclusion of children in low-income families. The statistically significant changes in (active) parents’ knowledge of activities are in line with the programme’s documented publicity efforts on these activities and with active parents’ programme exposure, thus seem to be programme impacts.

Implications and recommendations for policy and public health and future research

For municipal policy advisors and health promotion professionals, this research implies the relevance of supporting the realisation of health-enabling activities with people in a disadvantaged SEP as this resulted in community activities that were increasingly known and used, in particular by active parents. These parents are likely to have talked with people not directly exposed to activities, allowing knowledge to transfer.57 There was also a positive rippling of engaging parents actively, as they felt supported by the programme in finding paid and voluntary work.

This study also shows the importance of national policies in supporting municipal policies to provide accessible activities for families in a low SEP: with a one-time national government subsidy, free swimming lessons were provided and embedded in municipal policy. Constant stakeholder investment is needed at all levels in the community and at national policy level. Their continued support turned out to be of vital importance for the realisation of programme activities.

Recommendations for future research

This study showed that programme monitoring and a cohort study together gave a comprehensive understanding of the impact on multiple levels. However, as discussed above, these methods have their limitations. They were time-intensive and could not prove with certainty the relation between the programme activities (interventions) and the outcomes. Therefore, we have several suggestions for future researchers in the field to assess the impact of similar programmes. Outputs and initial outcomes should be analysed only for people actively involved in the interventions, and not drawn from a general survey. It would be good to use a prospective longitudinal cohort design, including all and only people involved in the interventions. In addition, (group) interviews with the involved community members can give more insight into stakeholders’ perspectives on the implementation process, for example, enabling factors of participatory learning and action.

Conclusions

This study found that a 4-year participatory family health programme was successful in realising changes on multiple levels. This programme focused on contributing to neighbourhood child friendliness (community level) by structural changes (on organisational and municipal policy level): activities embedded in organisational routines (playground, swimming lessons and administration support) and recognition of needs of families in a disadvantaged SEP in municipal policy (low-cost sports possibilities). In the long term, structural changes can result in changes on the intrapersonal level: health (behaviours). The realised impact was the result of community action by programme researchers, parents and professionals in multiple sectors. These stakeholders took steps on the long pathway towards improved parent and child health in a disadvantaged SEP, but stakeholders on all influencing levels, including national policy, need to continue investing.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank all parents, students and professionals in research, practice and policy that made this study possible. Special thanks to Sylvia Meijer and Gerard Molleman for connecting the programme initiator to the professional network in the community and Hans Bussink for connecting to parents in the community. We thank all continuing contacts for their updates. We thank FNO for the programme funding.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Fund NutsOhra (FNO) grant number 101566.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by Research ethics committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre. Filenumber 2017-3145 Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

References

- 1.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. Building of the global movement for health equity: from Santiago to Rio and beyond. Lancet. 2012;379:181–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenbach JP, Valverde JR, Artnik B, et al. Trends in health inequalities in 27 European countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:6440–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800028115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broeders DWJ, Das HD, Jennissen RPW, et al. Van verschil naar potentieel: een realistisch perspectief op de sociaaleconomische gezondheidsverschillen [from disparity to potential. a realistic perspective on socio-economic health inequalities WRR] 2018

- 4.Wink G, Fransen G, Huisman M, et al. ‘Improving Health through Reducing Stress’: Parents’ Priorities in the Participatory Development of a Multilevel Family Health Programme in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in The Netherlands. IJERPH. 2021;18:8145. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot M, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review. 2010 www.ucl.ac.uk/marmotreview Available. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Design and Nature. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, et al. An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novilla M, Barnes M, Cruz N, et al. Public health perspectives on the family: an ecological approach to promoting health in the family and community. Fam Community Health. 2006;29:28–42. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez ME, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, et al. Intervention Mapping: Theory- and Evidence-Based Health Promotion Program Planning: Perspective and Examples. Front Public Health. 2019;7:209. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golden SD, Earp JAL. Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of Health Education & Behavior Health Promotion Interventions. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:364–72. doi: 10.1177/1090198111418634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, et al. Planning Health Promotion Progams, an Intervention Mapping Approach. 3rd. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass a Wiley Imprint; 2011. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Ottawa charter for health promotion. Health Promot Int. 1986;1:405. doi: 10.1093/heapro/1.4.405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halladay JR, Donahue KE, Cené CW, et al. The association of health literacy and blood pressure reduction in a cohort of patients with hypertension: The heart healthy lenoir trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:542–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beenackers MA, Nusselder WJ, Oude Groeniger J.Reducing Health Inequalities: A Systematic Review of Promising and Effective Interventions [Het Terugdringen van Gezondheidsachterstanden: Een Systematisch Overzicht van Kansrijke En Effectieve Interventies] .Rotterdam: Erasmus MC; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid D, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research. 2013;1:1–526. doi: 10.3310/phr01040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilderink L, Bakker I, Schuit AJ, et al. A theoretical perspective on why socioeconomic health inequalities are persistent. Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, et al. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:129. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleland CL, Tully MA, Kee F, et al. The effectiveness of physical activity interventions in socio-economically disadvantaged communities: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2012;54:371–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijtzes AI, van de Gaar VM, van Grieken A, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve lifestyle behaviors among socially disadvantaged children in Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:240–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brand T, Pischke CR, Steenbock B, et al. What works in community-based interventions promoting physical activity and healthy eating? A review of reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2014;11:5866–88. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110605866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfenden L, Wyse R, Nichols M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of whole of community interventions to prevent excessive population weight gain. Prev Med. 2014;62:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman L, Baum F, Javanparast S, et al. Addressing social determinants of health inequities through settings: a rapid review. Health Promot Int. 2015;30 Suppl 2:ii126–43. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crandall A, Weiss-Laxer NS, Broadbent E, et al. The Family Health Scale: Reliability and Validity of a Short- and Long-Form. Front Public Health. 2020;8:587125. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.587125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuchler M, Rauscher M, Rangnow P, et al. Participatory Approaches in Family Health Promotion as an Opportunity for Health Behavior Change-A Rapid Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:8680. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MHS . Neighbourhood Monitor Data of the Municipal Health Service (MHS) Nijmegen: GGD Gelderland-Zuid; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:854–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vlaming R. In: Epidemiology in public health practice. Haveman-Nies A, Jansen S, van Oers H, et al., editors. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Academic Publishers; 2010. Construct a logic model; pp. 159–83. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghate D. Developing theories of change for social programmes: co-producing evidence-supported quality improvement. Palgrave Commun. 2018;4:1–13. doi: 10.1057/s41599-018-0139-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Reilly-de Brún M, de Brún T, O’Donnell CA, et al. Material practices for meaningful engagement: An analysis of participatory learning and action research techniques for data generation and analysis in a health research partnership. Health Expect. 2018;21:159–70. doi: 10.1111/hex.12598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai V, Potter R. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd; 2006. Doing development research.https://methods.sagepub.com/book/doing-development-research Available. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creswell J, Clark V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2011. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaur M. Application of Mixed Method Approach in Public Health Research. Indian J Community Med. 2016;41:93–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.173495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guijt I.Accountability and Learning. Capacity Development in Practice .London, UK: EarthScan; 2010277–91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett D, Noble H. What are cohort studies? Evid Based Nurs. 2019;22:95–6. doi: 10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coppens M. Together Northern Wijchen Interviewers Handbook Quantitative Data Collection. Nijmegen: Wageningen University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 1988. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elm E von, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ . 2007;335:806–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romon M, Lommez A, Tafflet M, et al. Downward trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight in the setting of 12-year school- and community-based programmes. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:1735–42. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008004278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronda G, Van Assema P, Ruland E, et al. The Dutch heart health community intervention “Hartslag Limburg”: results of an effect study at organizational level. Public Health. 2005;119:353–60. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuit AJ, Wendel-Vos GCW, Verschuren WMM, et al. Effect of 5-year community intervention Hartslag Limburg on cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mikkelsen BE, Novotny R, Gittelsohn J. Multi-Level, Multi-Component Approaches to Community Based Interventions for Healthy Living-A Three Case Comparison. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1–18.:1023. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13101023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geppert C, Muns S. Raising the minimum wage and social assistance – a panacea for the prosperity and well-being of the low-income group [verhoging van minimumloon en bijstand als wondermiddel voor welvaart en welbevinden van de lage inkomensgroep] 2023

- 43.Egede LE, Walker RJ, Williams JS. Addressing Structural Inequalities, Structural Racism, and Social Determinants of Health: a Vision for the Future. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:487–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-023-08426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health [social determinants of health discussion paper 2 (policy and practice)] 2010

- 45.Andress L, Hall T, Davis S, et al. Addressing power dynamics in community-engaged research partnerships. J Patient Rep Outcomes . 2020;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00191-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christensen Institute Social determinants of health. 2018. https://www.christenseninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Social-Determinants-of-Health-Table.png Available.

- 47.de Hernandez BU, Schuch JC, Sorensen J, et al. Sustaining CBPR Projects: Lessons Learned Developing Latina Community Groups. Collaborations. 2021;4:1–12. doi: 10.33596/coll.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Groot B, Nijland-Turel A, Waagen S, et al. Partnership with families in poverty at policy or programme level. TSG Tijdschr Gezondheidswet. 2021;99:128–31. doi: 10.1007/s12508-021-00307-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wink G, Broekhuisen N, Fransen G. Nijmegen: GGD Gelderland-Zuid (Municipal health service); 2021. Handboek de ronde van… samen met inwoners werken aan gezondheid in de wijk (handbook the round of…collaborating with inhabitants on community based health promotion)https://onderzoek.ggdgelderlandzuid.nl/handboek-de-ronde-van/de-ronde-van/ Available. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, et al. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:725. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90:311–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimmerman EB, Creighton GC, Miles C, et al. Assessing the Impacts and Ripple Effects of a Community-University Partnership: A Retrospective Roadmap. Mich J Community Serv Learn . 2019;25:62–76. doi: 10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0025.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ortiz K, Nash J, Shea L, et al. Partnerships, Processes, and Outcomes: A Health Equity-Focused Scoping Meta-Review of Community-Engaged Scholarship. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:177–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ng S-K, Scott R, Scuffham PA. Contactable Non-responders Show Different Characteristics Compared to Lost to Follow-Up Participants: Insights from an Australian Longitudinal Birth Cohort Study. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1472–84. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1946-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Network Child Friendly Cities, Ministry of Housing Spatial Planning, and the Environment. Kindvriendelijke projecten in de openbare ruimte [Child-friendly projects in public space] Alphen a/d Rijn. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 56.MHS . Neighbourhood Monitor Data of the Municipal Health Service (MHS) Nijmegen: GGD Gelderland-Zuid; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boulay M, Storey JD, Sood S. Indirect Exposure to a Family Planning Mass Media Campaign in Nepal. J Health Commun. 2002;7:379–99. doi: 10.1080/10810730290001774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.