Abstract

Background

The Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan documents the value of a collaborative provider workforce trained in the provision of hepatitis treatment and prevention to facilitate the United States’ 2030 viral hepatitis elimination efforts.

Aims

This study aims to characterize the amount and type of viral hepatitis education topics provided to Doctor of Medicine students during the preclinical phase of medical school.

Methods

Investigators developed a 19-item Qualtrics survey and sent survey links to curricula content experts at 157 accredited medical colleges/schools in April–May 2023, and allotted 28 days for survey completion. Survey questions assessed the type, amount, and topics of viral hepatitis instruction provided to Doctor of Medicine students, and the hepatitis instructors’ training/experience. We used descriptive statistics for analysis.

Results

51 medical institutions across 22 jurisdictions responded; 90% of programs presented hepatitis education as a required part of the curriculum. All education topic respondents confirmed that their institutions provided instruction on viral hepatitis epidemiology, diagnostics, and HBV vaccination. Screening and linkage to care for HBV, HCV, and HDV were included in 69%, 78%, and 33% of curricula, respectively, while 11% of curricula discussed national efforts to eliminate hepatitis by 2030.

Conclusions

Survey results show similarities, variability, and gaps in topics devoted to viral hepatitis education across United States medicine curricula. Most programs required hepatitis education in their curricula, many discussed HBV and HCV screening, and few discussed hepatitis elimination. To support national viral hepatitis elimination efforts, ideally, all medical schools should provide education on (1) screening, (2) linkage to care, and (3) national elimination strategies to better equip all future physicians to work toward viral hepatitis elimination.

Keywords: Physician, Hepatitis elimination, College of medicine, Curriculum, Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

Introduction

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a global target to eliminate hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. The initiative addresses hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E, with a particular focus on hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to their substantial contribution to global morbidity and mortality [1]. The WHO has emphasized interventions to assist with hepatitis elimination progress, such as HBV vaccination, enhanced blood safety protocols, expansion of testing and antiviral therapies, and training healthcare staff and investing in training for health workers at all levels [2].

Further WHO guidance on HCV elimination strategies offers suggestions for “task sharing through delivery of HCV testing, care and treatment by appropriately trained non-specialist doctors and nurses” [3].

The 2021–2025 Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan aims to eliminate viral hepatitis in the United States by 2030 through prevention, testing, and treatment strategies while emphasizing partnerships with professional societies, academic institutions, and accrediting bodies to integrate viral hepatitis prevention and care in the curriculum of healthcare professionals and paraprofessionals [4]. Healthcare providers, particularly physicians, are central to the success of hepatitis elimination efforts, given their role in diagnosis, disease management, vaccination, and patient education.

A 2019 call-to-action from international professional organizations, including the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, emphasized the need for comprehensive, targeted training to equip future physicians with the skills necessary for hepatitis elimination efforts [5]. Despite the critical role of physicians, current United States medical school curricula lack standardized requirements for hepatitis-specific education. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), which accredits medical schools in the United States, does not mandate specific disease-state curricular content [6].

This study aims to characterize the amount and type of viral hepatitis education topics provided to Doctor of Medicine students during the preclinical phase of medical school.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study of medical school curricular content experts. Our team of investigators reviewed relevant literature on medical curricula surveys and developed a survey tool with Qualtrics software. Eight physicians and pharmacists with experience in medical education, hepatitis management, and survey creation pilot-tested the survey and offered feedback. We designed the electronic survey to take approximately 5–10 minutes to complete to avoid survey abandonment. The final questionnaire consisted of 19 items. The first question was “Are you able to provide information about your College or School of Medicine’s viral hepatitis education for the 2022–2023 academic year (e.g., specific hepatitis topics and number of hours within the preclinical curriculum)?” Respondents who answered “No” were routed to the end of the survey, where they could provide contact information for a colleague with the relevant expertise. Respondents who answered “Yes” received subsequent survey questions, which consisted of three questions about institutional characteristics of school size, program length, and state; four questions about the scope of hepatitis education (requirement, delivery method of lecture versus discussion format, and hours); five questions about hepatitis A-E content; and six questions about the hepatitis instructor's characteristics.

We obtained a list of 157 LCME-accredited medical colleges from their website as of March 30, 2023 and reviewed each college’s website to obtain names and email addresses of each institution’s curricular experts with listed positions within the college’s curriculum or medical education department. We used Qualtrics to email all 157 LCME-accredited medical colleges the initial questionnaire links in April and May 2023 and sent reminders throughout the 28-day completion window. We used Excel and Qualtrics to analyze data and used descriptive statistics used to summarize categorical and continuous variables.

The University of Illinois Chicago Institutional Review Board granted exemption for this survey study (Protocol #2023–0397) on April 7, 2023. All research was conducted in accordance with both the Declarations of Helsinki and Istanbul. The email with the questionnaire instructions to participants stated “Submission of the responses to the survey will be interpreted as consent to participate.”

Results

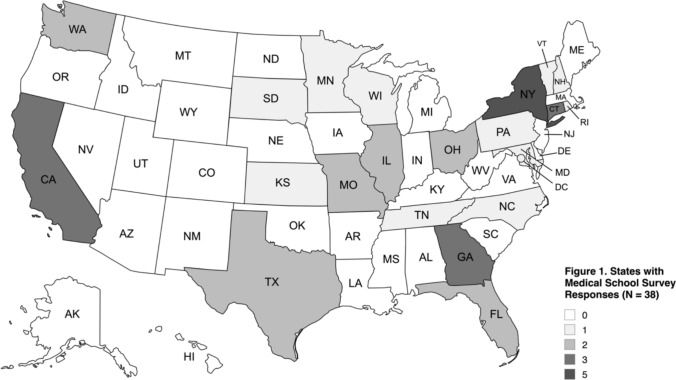

Of the 157 LCME-accredited medical schools contacted as of May 2023, 51 provided survey responses, yielding an initial response rate of 32%. Twelve respondents indicated they had insufficient knowledge of curricular content and subsequently did not receive subsequent survey questions. One participant only answered yes to the first question and abandoned the survey. The final response rate was 24% with 38 usable questionnaire responses for the analysis with participating schools spanning across 21 states and the District of Columbia (Fig. 1). Eighty-nine percent (34/38) completed all survey questions, and 4 institutions did not answer every question.

Fig. 1.

States with Medical School Survey Responses (N = 38)

All (36/36) education topic respondents confirmed that their institutions provided instruction on viral hepatitis epidemiology, diagnostics, and HBV vaccination. Screening and linkage to care for HBV, HCV, and HDV were included in 69%, 78%, and 33% of curricula, respectively (Table 1). Eleven percent of respondents stated their curricula discussed national efforts to eliminate hepatitis by 2030. Pharmacology content was covered 86%, 92%, 22%, and 31% of the time for HBV, HCV, HDV, and HEV, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Viral Hepatitis Education Topics and Average Hours

| Education Topic (n = 36) | n (%) of Institutions |

|---|---|

| Epidemiology | |

| HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV | 36 (100) |

| Serologies/Diagnostics | |

| HAV, HBV, HCV | 36 (100) |

| HDV | 27 (75) |

| HEV | 28 (78) |

| Hepatitis B Immune Globulin | 31 (86) |

| Pipeline Agents for Hepatitis Treatment | |

| HBV | 2 (6) |

| HDV | 1 (3) |

| National Efforts to Eliminate Hepatitis by 2030 | |

| HBV, HCV | 4 (11) |

| Drug–Drug Interaction Assessment | |

| HBV, HCV | 9 (25) |

| HIV Co-Infection | |

| HBV | 21 (58) |

| HCV | 20 (56) |

| HCV Donor ( +) / Recipient (−) Solid Organ Transplantation | 7 (19) |

| Screening and Linkage to Care | |

| HBV | 25 (69) |

| HCV | 28 (78) |

| HDV | 12 (33) |

| Pharmacology | |

| HBV | 31 (86) |

| HCV | 33 (92) |

| HDV | 8 (22) |

| HEV | 11 (31) |

| HAV Supportive Care | 21 (58) |

| Therapeutics | |

| HBV | 31 (86) |

| HCV | 26 (72) |

| HDV | 9 (25) |

| HEV* | 10 (28) |

*n = 35; one institution did not provide a response for HEV

HAV Hepatitis A Virus; HBV Hepatitis B Virus; HCV Hepatitis C Virus; HDV Hepatitis D Virus; HEV Hepatitis E Virus; HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Sixty-eight percent (23/34) of the institutions’ instructors were full-time clinical faculty (Table 2). Ninety-five percent (36/38) of participating programs identified as four-year institutions and 53% (20/38) were public institutions. Among 33 respondents, the average enrollment per class was 159 ± 61 students.

Table 2.

Primary Hepatitis Instructor Characteristics

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary Hepatitis Position at Institution (n = 34) | |

| Physician, Full-Time Faculty | 23 (68) |

| Physician, Part-Time/Adjunct Faculty | 2 (6) |

| Research Scientist, Full-Time Faculty | 9 (26) |

| Board Certification (n = 34) | |

| No | 10 (29) |

| Yes | 22 (65) |

| Unsure | 2 (6) |

| Number of Board Certifications (n = 22) | |

| 1 | 10 (46) |

| 2 | 8 (36) |

| 3 | 4 (18) |

| Board Certification Specialties (n = 22)* | |

| Gastroenterology | 13 (34) |

| Internal Medicine | 15 (40) |

| Infectious Disease | 5 (13) |

| Transplant Hepatology | 5 (13) |

| Works in Hepatitis Clinical Setting (n = 34) | |

| No | 10 (29) |

| Yes | 23 (68) |

| Unsure | 1 (3) |

| Time Spent on Patient Care (For Instructors Who Work in a Clinical Setting) (n = 21)† | |

| < 20% | 5 (24) |

| 20–39% | 7 (33) |

| 40–59% | 5 (24) |

| 60–79% | 2 (10) |

| ≥ 80% | 2 (10) |

*12 respondents had multiple Board Certification Specialties

†2 respondents did not specify the amount of time spent on patient care

Ninety percent of programs presented hepatitis education as a required part of the curriculum. The average reported required lecture hours were 2.5 ± 1.2 (n = 32) and discussion hours were 2.5 ± 1.5 (n = 30) per program. Seventy-nine percent of institutions reported using a combination of lectures and discussions to deliver required viral hepatitis education during the preclinical phase; 10.5% exclusively used small group discussions, and 10.5% only used lectures. Table 3 presents the average enrollment and required viral hepatitis instruction hours and the CDC-reported acute and chronic HBV and HCV infections by jurisdiction in 2023 [7–10].

Table 3.

Respondent Schools’ Average Class Size and Required Viral Hepatitis Content and CDC-Reported Acute and Chronic Hepatitis Data by Jurisdiction [7–10]

| Jurisdiction (N = 22) | Number of Schools who Responded (N = 38) | Number of Students; Average ± SD | Number of Required Viral Hepatitis Lecture Hours; Average ± SD | Number of Required Viral Hepatitis Discussion Hours; Average ± SD | Acute HBV Rate per 100,000 in 2023 | Chronic HBV Rate per 100,000 in 2023 | Acute HCV Rate per 100000 in 2023 | Chronic HCV Rate per 100000 in 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 3 | 183 ± 3‡‡ | 1.67 ± 0.47 | 1.67 ± 0.47 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 24.5 |

| Connecticut | 3 | 103 ± 6.2 | 3.67 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 0** | 0.1 | NR | 0.1 | 17.2 |

| District of Columbia | 1 | 200 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 16.6 |

| Florida‡ | 2 | 200 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 10.1 | 6.3 | 37.1 |

| Georgia | 3 | 131.7 ± 16.5 | 2.33 ± 1.25 | 3.0 ± 1.0** | 1.1 | 18.4 | 0.7 | 40.4 |

| Illinois‡ | 2 | 300 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 16.8 |

| Kansas | 1 | 211 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 27.4 |

| Maryland | 1 | 120 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 8.8 | 1 | 27.2 |

| Minnesota | 1 | 240 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 4.7 | 0.9 | 16.5 |

| Missouri‡ | 2 | 140 | 2.0 | 1.0** | 0.3 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 55.6 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 92 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 11.6 |

| New York | 5 | 139.2 ± 33.3 | 1.67 ± 1.25* | 3.10 ± 1.56** | 0.3 | 13.0 | 1.9 | 20.5 |

| North Carolina | 1 | 190 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1 | 3.0 | 0.3 | NR |

| Ohio | 2 | 179.5 ± 4.5 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 44.3 |

| Pennsylvania | 1 | 275 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 0.3 | 6.8 | 1.3 | 38.4 |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 144 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 19.7 | 2.1 | 59 |

| South Dakota | 1 | 71 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 51.2 |

| Tennessee | 1 | 180 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 6.7 | 2.9 | 71.5 |

| Texas | 2 | 150 ± 90 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 0.3 | NR | 0.3 | NR |

| Vermont | 1 | 124 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 36.3 |

| Washington‡ | 2 | 80 | 0.0* | 4.50 ± 1.50 | 0.3 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 28.3 |

| Wisconsin | 1 | 265 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 18.3 |

‡ Indicates states where one school did not provide the number of average students, required viral hepatitis lecture, and required discussion hours

‡‡ Indicates state where one school did not provide the average number of students

*Indicates states where one responding school did not require viral hepatitis lecture hours

**Indicates states where one responding school did not require viral hepatitis discussion hours

NR Not Reportable. The disease or condition was not reportable by law, statute, or regulation in the reporting jurisdiction

Discussion

Data from this diverse, cross-sectional analysis demonstrate variability in the number of viral hepatitis instructional hours and delivery methods within medical curricula. Ninety percent of responding medical programs require viral hepatitis education, and the majority offer education on screening and linkage to care for HBV and HCV. However, only a small minority discussed national efforts to eliminate HBV and or HCV. A recent survey also reported variability across pharmacy schools’ hepatitis education [11]. Yet, published literature lacks consistent details on hepatitis education across healthcare providers.

Limitations of this study include its response rate as well as the exclusion of osteopathic curriculum. We cannot infer details of potential non-response bias from non-responders. Repeat outreach or incentives may improve response rates for email surveys. We sent multiple reminders throughout the survey timeframe; however, we did not offer financial or other incentives for questionnaire completion. Our survey timeframe occurred during the end of many schools’ academic year during which time educators have many competing demands for time, which may have negatively impacted our response rate. Respondents could have forwarded their questionnaire link to a colleague to assist with completion; this may have positively or negatively impacted survey completion. We relied on respondents to self-report data, and did not have IRB approval to reach out to institutions for clarification or to request course syllabi. We inquired about the inclusion of specific hepatitis topics, but not about the depth of coverage within those topics. Respondents may not have been entirely familiar with the institution’s instructional content as instructors may vary, administrators may not know the nuances of each course’s content, or specific teaching may differ from the blueprint or course syllabi. Hence, our data are only as accurate as the respondents’ dedication to providing accurate information in the questionnaire response. The findings are specific to the institutions who responded to our questionnaire, and we cannot confirm that they are generalizable to other institutions.

Stakeholders in elimination efforts could conjecture that perhaps a small proportion of medical school graduates would have awareness of the goals for and importance of viral hepatitis elimination if only 11% of future physicians from responding schools receive didactic education about HBV and HCV elimination; however, we are unaware of published data addressing outcomes on this specific viral hepatitis topic.

Professional training and education are cited as necessary components to assist with the elimination of HBV and HCV as global health threats [12]. Most high-income nations are not on target to eliminate HCV by 2030 [13]. Global progress has occurred, but strategies must address the staggering estimates of undiagnosed and untreated HBV and HCV [14, 15]. One WHO checklist component for the validation of an elimination implementation program includes “Hepatitis workforce training (in person/online training, curriculum and mentorship) is included in national health policies” [16]. Although WHO recommendations for training of healthcare providers are components of the viral hepatitis elimination blueprint, it does not delve into the specific details of medical school hepatitis education [2]. The Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination offers a comparison of HBV and HCV elimination efforts across nations [17]. We are unaware of nationwide comparisons for mandatory physician or other healthcare provider education strategies to assist with HBV and HCV elimination.

Published literature calls for viral hepatitis education for healthcare providers in the United States and abroad. A survey of physicians and nurse practitioners in Washington, DC reported that primary care providers needed additional training for them to engage in HCV treatment [18]. Publications documenting efforts for HCV elimination called for the incorporation of prevention and treatment education within healthcare curricula for specialists, family physicians, and paramedical staff in India [19]. Published data document medical student knowledge on vaccination for HBV and treatment for HBV and HCV internationally [20–23]. Providers must be trained in order to achieve viral hepatitis elimination.

The instructional variability that we discovered may stem from the absence of standardized requirements in medical school curricula. We recognize that requiring instructional content across institutions would be burdensome and difficult to implement with competing concerns for other diseases. Ideally, to support national viral hepatitis elimination efforts, all medical schools should provide education on (1) screening, (2) linkage to care, and (3) national elimination strategies. Without mandatory content inclusion, hepatology or education organizations could consider distributing a national call-to-action guidance document to all allopathic and osteopathic medical schools to encourage integration of these three key topics into viral hepatitis curricula. A collaborative intervention could equip all future physicians with background knowledge upon graduation and perhaps increase awareness to facilitate work toward viral hepatitis elimination.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all survey respondents for taking time to complete our survey and the individuals who assisted with pilot testing and survey tool feedback, including: Maja Kuharic, MPharm, Msc, PhD; Bernice Man, MD, MS; Anthony Martinez, MD, AAHIVS, FAASLD; Aileen Pham, PharmD; Kanya Shah, PharmD, MS, MBA; and Jessica Wagner, PharmD.

Abbreviations

- LCME

Liaison Committee on Medical Education

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author Contribution

MM led study conceptualization, investigation, and data curation. MM led and ZS, GM, AP, and AM assisted with methodology and formal analysis. MM and ZS wrote the main manuscript text and ZS prepared Fig. 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript, gave final approval of data, and are accountable for the work.

Funding

None.

Data Availability

Preliminary results of this study were presented as a poster at The Liver Meeting for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases on November 10, 2023 in Boston, MA. Individual survey respondent data will not be available. Investigators did not receive funding for this research.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

Authors of this presentation are affiliated with or had an affiliation with the University of Illinois Chicago and have no other disclosures concerning financial or personal relationships with commercial entities that may have a direct or indirect interest in this presentation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/29/2025

The typo in the city name was corrected.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis 2016–2021. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06. Accessed December 20, 2024.

- 2.Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030. World Health Organization. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053779. Published July 18, 2022. Accessed December 20, 2024.

- 3.Updated recommendations on simplified service delivery and diagnostics for hepatitis C infection. World Health Organization. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052697. Published June 24, 2022. Accessed December 20, 2024.

- 4.Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Website. Updated January 4, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2024.

- 5.Call-to-Action to Advance Progress Towards Viral Hepatitis Elimination: A Focus on Simplified Approaches to HCV Testing and Cure. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Available at https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/2019-HCVElimination-CallToAction-v2.pdf. Published November 10, 2019. Accessed December 20, 2024.

- 6.LCME – Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Updated November 1, 2024. Accessed December 20, 2024. Available at https://lcme.org/directory/accredited-u-s-programs/

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Figure 2.2. Rates of reported chronic hepatitis B, by jurisdiction — United States, 2023. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-surveillance-2023/hepatitis-b/figure-2-2.html. Accessed April 21, 2025.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Table 2.5. Number and rate of newly reported cases of chronic hepatitis B, by state or jurisdiction — United States, 2023. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-surveillance-2023/hepatitis-b/table-2-5.html. Accessed April 21, 2025.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Figure 3.2. Rates of reported chronic hepatitis C, by jurisdiction — United States, 2023. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-surveillance-2023/hepatitis-c/figure-3-2.html. Accessed April 21, 2025.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Table 3.5. Number and rate of newly reported cases of chronic hepatitis C, by state or jurisdiction — United States, 2023. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-surveillance-2023/hepatitis-c/table-3-5.html. Accessed April 21, 2025.

- 11.Martin MT, Pham AN, Wagner JS. A cross-sectional survey of viral hepatitis education within pharmacy curricula in the United States. Int J Clin Pharm. 2024;46:648–655. 10.1007/s11096-023-01691-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward JW, Hinman AR. What is Needed to Eliminate Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus as Global Health Threats. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamkrelidze I, Pawlotsky JM, Lazarus JV et al. Progress towards hepatitis C virus elimination in high-income countries: An updated analysis. Liver Int. 2021;41:456–463. 10.1111/liv.14779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui F, Blach S, Manzengo Mingiedi C et al. Global reporting of progress towards elimination of hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:332–342. 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleurence RL, Alter HJ, Collins FS, Ward JW. Global Elimination of Hepatitis C Virus. Annu Rev Med. 2025;76:29–41. 10.1146/annurev-med-050223-111239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Interim guidance for country validation of viral hepatitis elimination. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240028395. June 2021. Accessed April 23, 2025.

- 17.Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination. Available at https://www.globalhep.org/. Accessed April 23, 2025.

- 18.Doshi RK, Ruben M, Drezner K et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Related to Hepatitis C Screening and Treatment among Health Care Providers in Washington DC. J Community Health. 2020;45:785–794. 10.1007/s10900-020-00794-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhiman RK, Satsangi S, Grover GS, Puri P. Tackling the Hepatitis C Disease Burden in Punjab India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016;6:224–232. 10.1016/j.jceh.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prabhakar T, Kaushal K. Knowledge Dissemination for Elimination role of Academic Institutions in Eliminating Viral Hepatitis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2023;71:11–12. 10.59556/japi.71.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suilik HA, Alfaqeh O, Alshrouf A et al. Medical students’ knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding hepatitis B and C virus infections in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7:e70150. 10.1002/hsr2.70150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohamed OMI, Mohammedali HSH, Mohamed SNA et al. Knowledge, attitudes, practices, and vaccination coverage of medical students toward hepatitis B virus in North Sudan, 2023. PeerJ. 2025;13:e18339. 10.7717/peerj.18339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham TTH, Nguyen TTL, So S et al. Knowledge and Attitude Related to Hepatitis C among Medical Students in the Oral Direct Acting Antiviral Agents Era in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:12298. 10.3390/ijerph191912298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Preliminary results of this study were presented as a poster at The Liver Meeting for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases on November 10, 2023 in Boston, MA. Individual survey respondent data will not be available. Investigators did not receive funding for this research.