Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), particularly in older adults aged 60 years and above, present significant therapeutic challenges due to poor prognosis and limited treatment options. Higher-risk MDS (HR-MDS), defined by the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System score of ⩾3.5, is characterized by increased myeloblasts, severe cytopenia, and a median survival of <2 years. The pathogenesis involves complex genetic mutations, cytogenetic abnormalities, and a dysregulated bone marrow microenvironment. Current standard therapies, such as hypomethylating agents and allogeneic stem cell transplantation, are often inadequate, especially in older patients with comorbidities and limited clinical trial eligibility. This review highlights emerging targeted therapies for older HR-MDS patients, focusing on small-molecule agents for their critical advantages like patient-friendly oral delivery, lower production barriers, improved access to intracellular targets, and flexible dosing strategies. Venetoclax, an oral B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) inhibitor, has shown promise in clinical trials but requires further validation. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) inhibitors, including ivosidenib and olutasidenib, have demonstrated efficacy and tolerability, while ongoing investigations explore other novel agents like IDH2 inhibitors and FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitors. By summarizing the latest advancements, this review emphasizes the importance of developing safe, effective, and personalized therapies to improve outcomes and quality of life for older patients with HR-MDS, with a focus on age-specific clinical trials.

Keywords: higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome, novel agents, older adults, precision medicine, targeted therapies

Plain language summary

New and emerging treatments for older adults aged 60 and above with high-risk blood disorders: current treatment options and challenges

For older adults aged 60 or above with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (HR-MDS), the prognosis remains challenging. These patients often face more severe disease and have limited treatment options due to age and other health issues. Standard treatments, such as stem cell transplants, are often not suitable for them, making it crucial to find safer and more effective therapies. Recent research has improved our understanding of the genetic and biological factors driving MDS, leading to the development of new small-molecule therapies that target specific aspects of the disease at the molecular level. These therapies are promising alternatives, particularly for older patients who cannot tolerate aggressive treatments. Drugs like IDH1/2 inhibitors, BCL-2 inhibitors (Venetoclax), and XPO1 inhibitors have shown positive results in trials, with some already approved or under review. Other drugs, including HDAC inhibitors, FLT3 inhibitors, and those targeting genes like TP53, ALK5, and NAE, have also shown promise in early-stage trials. Additionally, experimental treatments targeting the Hedgehog pathway and spliceosome are being studied. These new therapies are shifting the treatment approach towards more personalized care, tailored to each patient’s genetic makeup. However, long-term studies are still needed to confirm their safety and effectiveness. As the number of older adults with HR-MDS rises, it’s important to integrate these novel therapies into clinical practice. Continued research, particularly into personalized medicine, and the inclusion of more older patients in clinical trials, will be key to improving treatment outcomes and quality of life for this vulnerable group.

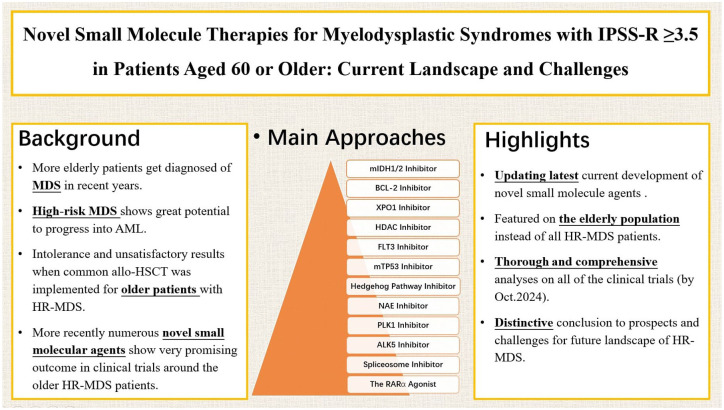

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) encompass a diverse array of clonal myeloid malignancies characterized by dysplastic hematopoiesis, ineffective blood cell production, and an increased propensity for progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The incidence of MDS escalates with age, with a median age of diagnosis around 70 years, predominantly affecting individuals aged 60 or older. 1 Older patients often present with more severe disease and face additional treatment challenges due to comorbidities and clinical complexities. Moreover, advanced age is increasingly associated with reduced tolerance to standard therapies, such as allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), making the elderly population a distinct and clinically significant subgroup in MDS management. 2 Risk assessment is pivotal in guiding MDS management, with models such as the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), the Revised IPSS (IPSS-R), and the recently developed molecular IPSS providing risk stratification to aid therapeutic decision-making. Higher-risk MDS (HR-MDS), classified by an IPSS-R score of ⩾3.5, corresponds to the intermediate, high, or very high-risk categories and accounts for approximately 43% of MDS cases. 3 This subgroup is associated with higher myeloblast counts, severe cytopenia, increased transfusion dependency, 4 and a median overall survival (mOS) of <2 years. Given the aging population and the projected increase in MDS cases, there is a pressing need for effective, well-tolerated treatment strategies tailored to older adults with HR-MDS.

The pathogenesis of MDS is complex, involving cytogenetic abnormalities, gene mutations, and dysregulation of the bone marrow microenvironment. Advances in next-generation sequencing have identified numerous gene mutations associated with MDS, enhancing our understanding of clonal disease evolution 5 and driving the development of molecularly targeted therapies. 6 Currently, treatment options for HR-MDS remain limited, primarily relying on hypomethylating agents (HMAs) such as azacitidine (AZA) and decitabine (DEC), along with allo-HSCT, which is curative in only a small subset of patients. The primary therapeutic goals for this population are to delay leukemic transformation, prolong survival, and improve quality of life. 7 However, response rates to HMAs remain suboptimal, with only 40%–50% of patients achieving a response, and complete remission (CR) occurring in just 10%–20% of cases. 8 Furthermore, resistance mechanisms remain poorly understood, and effective second-line treatments are lacking for patients who fail HMA therapy.

This review examines recent advances in HR-MDS treatment. In light of the distinct benefits of small-molecule agents such as oral bioavailability, cost-efficient manufacturing, enhanced target penetration, and adaptable clinical utility, we focus on novel agents within this class, while also exploring emerging combination therapies. The treatments above may alter the disease course, especially in older adults. We summarize clinical evidence on venetoclax-based regimens, as well as inhibitors targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), IDH2, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), the Hedgehog pathway, exportin 1 (XPO1), and other promising targets (Tables 1 and 2). By analyzing their mechanisms of action (Figure 1), clinical trial data, and therapeutic potential, this review underscores the transition toward molecularly driven, patient-specific treatment strategies aimed at improving outcomes for older patients with HR-MDS.

Table 1.

Results on novel targeted agents in elderly patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes.

| Target and pathway | Agent | Patient characteristics | Number of patients | Phase | Outcome | Safety | Trial number | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDH1 | IVO | R/R MDS | 19 | I | ORR: 83.3%, CR: 38.9%, mOS: 35.7m | Fatigue: 15.8%, diarrhea: 10.5%, differentiation syndromes: 10.5%, rash: 10.5%, dyspnea: 10.5%. | NCT02074839 | DiNardo et al. 10 |

| IVO | HR-MDS (AZA failure or untreated) and LR-MDS |

N = 48 Cohort A: n = 22 Cohort B: n = 23 Cohort C: n = 5 |

II | Cohort A: ORR: 63.6% (CR 21%, PR 7%), mDoR: 4.8 m, mOS: 8.9 m; Cohort B: ORR: 78.3% (CR 61%, PR 11%), mDoR: not reached, mOS: not reached; Cohort C: 2/3 patients achieved CR |

21 AEs in 9 patients, mainly differentiation syndrome | NCT03503409 | Caillet et al. 11 | |

| Olutasidenib ± AZA | R/R MDS | A (olutasidenib): 9 B (olutasidenib + AZA): 7 |

I/II | A: ORR: 33%, CR: 17%; B: ORR: 86%, CR: 57% |

A: thrombocytopenia: 28%, febrile neutropenia: 22%, anemia: 22%; B: thrombocytopenia: 41%, febrile neutropenia: 28%, neutropenia: 28%, anemia: 20% |

NCT02719574 | Watts et al. 14 | |

| IDH2 | ENA | R/R MDS | 17 | I/II | ORR: 53%, mDoR: 9.2 m, mOS: 16.9 m, EFS: 11.0 m | Diarrhea and nausea: 53%, indirect hyperbilirubinemia: 35%, pneumonia: 29%, thrombocytopenia: 24% | NCT01915498 | Stein et al. 15 |

| ENA | HR-MDS (HMA failure or untreated) | 26 | II | ORR: 42%, CR: 55%, mOS: 17.3 m | Thrombocytopenia: 19%, diarrhea: 15%, nausea: 15% | NCT03744390 | ||

| ENA ± AZA | R/R MDS | A (ENA): 20 B (ENA + AZA): 24 |

II | A: ORR: 35%, mOS: 20 m, median EFS: 6.5 m B: ORR: 74%, mOS: 26 m, median EFS: 11.7 m |

Neutropenia: 40%, nausea: 36%, constipation: 32%, fatigue: 26% | NCT03383575 | DiNardo et al. 17 | |

| IDH1/IDH2 | HMPL-306 | R/R MDS, AML, CMML, and other myeloid neoplasm | 49 | I | The 100 mg QD cohort: CR: 33.3% The 150 mg QD cohort: CR: 36.0%, ORR: 40.0% The 200 mg QD cohort: CR: 14.3%, ORR: 14.3% The 250 mg QD cohort: CR: 42.9%, ORR: 42.9% |

TRAEs: 69.4% grade ⩾3 TRAEs: 26.5% |

NCT04272957 | Hu et al. 18 |

| BCL-2 | VEN ± AZA | R/R HR-MDS | 44 | Ib | ORR: 38.6%, CR: 6.8%, mOS: 12.6 m | Nausea: 47.7%, constipation: 45.5%, diarrhea: 38.6%, febrile neutropenia: 34.1%, thrombocytopenia: 31.8% | NCT02966782 | Zeidan et al. 30 |

| VEN + AZA | HR-MDS (treatment naïve) | 107 | Ib | ORR: 80.4%, CR: 29.9%, mOS: 26.0 m | Constipation: 53.3%, nausea: 49.5%, neutropenia: 48.6%, thrombocytopenia: 44.9% | NCT02942290 | Garcia et al. 31 | |

| VEN + AZA + Sabatolimab | HR-MDS (ineligible for HSCT) |

N = 20 Cohort 1: Sabatolimab (MBG453) 400 mg + AZA + VEN, n = 5 Cohort 2: Sabatolimab (MBG453) 800 mg + AZA + VEN, n = 15 |

II | CR: 6.7%, median EFS: 0.03 m | Cohort 1: neutropenia: 60%, thrombocytopenia: 60%, febrile neutropenia: 40% Cohort 2: neutropenia: 53.3%, thrombocytopenia: 46.67%, nausea: 40% |

NCT04812548 | ||

| APG-2575 + AZA | HR-MDS (R/R or treatment naïve) | 10 | Ib | ORR: 70%, CR: 60% | Not reported | NCT04501120 | Wang et al. 34 | |

| XPO1 | Selinexor | HR-MDS | 25 | II | ORR: 26%, mDoR: 6.3 m, mOS: 8.7 m | Nausea: 52%, anorexia: 38%, fatigue: 33% | NCT02228525 | Taylor et al. 35 |

| Eltanexor | HR-MDS | 20 | I/II | ORR: 53.3%, CR: 46.7%, mOS:9.86 m, mDoR: not reached | Nausea: 45%, diarrhea: 35%, decreased appetite: 35%, fatigue: 30%, neutropenia: 30% | NCT02649790 | Lee et al. 40 | |

| HDAC | Pracinostat ± AZA | R/R HR-MDS (failing HMAs or HSCT) | A (pracinostat): 44 B (pracinostat + AZA): 10 |

I | B: CR:60%, ORR:90%, 2-year DFS: 57%, OS: 56% | A: fatigue: 41%, nausea: 30%, anorexia: 23%, diarrhea: 16%, vomiting: 14% B: nausea: 100%, vomiting: 80%, fatigue: 60%, constipation: 50% |

NCT00741234 | Abaza et al. 44 |

| Pracinostat + AZA | HR-MDS | 51 | II | CR: 18%, mDoR: 12 m, mOS: 16 m, median EFS: 9 m | Thrombocytopenia: 49%, neutropenia: 45%, nausea: 69%, fatigue: 55%, constipation: 53% | NCT01873703 | ||

| Pracinostat + AZA | HR-MDS (HMA failure) | 64 | II | ORR: 33%, CR: 33%, mOS: 23.5 m | Neutrophil count decreased: 53%, nausea: 53%, constipation: 52%, anemia: 48%, fatigue: 45%, decreased appetite: 41% | NCT03151304 | Atallah et al. 46 | |

| FLT3 | Quizartinib + AZA | HR-MDS | 12 | I | ORR: 83%, R: 50%, mOS: 17.5 m | Fatigue: 67%, constipation: 67%, cough: 50%, insomnia: 50%, anorexia: 50%, arthralgia: 50%, diarrhea: 50% | NCT04493138 | Montalban-Bravo et al., 52 Flannery S and Bowie 53 |

| Quizartinib + AZA or cytarabine | R/R MDS | Phase I A (AZA): 5, B (cytarabine) 1; Phase II C (AZA): 35, D (cytarabine): 71 |

I/II | A: ORR: 40%; B: ORR: 100%; C: ORR: 77.1%; D: ORR: 59.4% | A: hypomagnesemia: 80%, hypocalcemia: 80%, hypokalemia: 80%, febrile neutropenia: 60%; B: anemia: 100%, febrile neutropenia: 100%, diarrhea: 100%, fatigue 100%; C: hypomagnesemia: 65.71%, hypokalemia: 62.86%, hypocalcemia: 57.14%, febrile neutropenia: 40%; D: pain: 50%, nausea: 43.75%, diarrhea: 40.63% | NCT01892371 | ||

| Quizartinib + chemotherapy | FLT3-ITD-positive AML | The quizartinib group: 268 The placebo group: 271 |

III | The quizartinib group: mOS:31.9 m, mCR: 54.9%, median EFS: 0.03 m The placebo group: mOS: 15.1 m, mCR: 55.4%, median EFS: 0.71 m |

The quizartinib group: Gastrointestinal disorders: 81.1%, infections and infestations: 77.0%, general disorders and administration site disorders: 66.8%, metabolism and nutrition disorders: 62.3% The placebo group: Gastrointestinal disorders: 78.0%, infections and infestations: 70.1%, general disorders and administration site disorders: 64.6%, skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders: 59.0% |

NCT02668653 | Erba et al. 51 | |

| TP53 | Eprenetapopt + AZA | HR-MDS (TP53-mutated) | 40 | Ib/II | ORR: 73%, CR: 50% | Nausea: 64%, vomiting: 45%, fatigue: 44%, constipation: 42%, dizziness: 36%, peripheral sensory neuropathy: 31% | NCT03072043 | Sallman et al. 62 |

| Eprenetapopt + AZA | HR-MDS (TP53-mutated) | 34 | II | ORR: 62%, CR: 47%, CR: 6%, mOS: 12.1 m | Febrile neutropenia: 37%, ataxia: 25%, cognitive impairment: 8%, acute confusion: 8% | NCT03588078 | Cluzeau et al. 60 | |

| Eprenetapopt + AZA | HR-MDS (TP53-mutated) | 78 | III | CR: 34.6% | Nausea 52.6%, constipation: 63.2%, neutrophil count decreased: 44.7%, anemia: 43.4%, febrile neutropenia: 40.8% | NCT03745716 | ||

| Emavusertib ± AZA/VEN | R/R HR-MDS | 49 | I/IIa | mCR: 57% | Grade 3 rhabdomyolysis A: in 300 mg BID: 4%, B: in 400 mg BID: 12%, C: in 500 mg BID: 33% |

NCT04278768 | Garcia-Manero et al. 57 | |

| APR-246 + AZA | TP53-mutated MDS/AML | 33 (14 AML and 19 MDS) | II | median relapse-free survival: 12.5 m, mOS: 20.6 m | Nausea: 60.61%, vomiting: 45.45%, platelet count decreased: 48.48%, anemia: 39.39%, pyrexia: 12.12%, hip fracture: 9.09%, febrile neutropenia: 6.06%, dyspnea: 6.06% | NCT03931291 | Mishra et al. 63 | |

| Hedgehog | Glasdegib + AZA | HR-MDS | 30 | Ib | ORR: 33.3%, CR: 13.3%, mDoR: 6.2 m, mOS: 15.8 m | Sepsis: 20.0%, diarrhea: 10.0%, hypotension: 10.0%, pneumonia: 10.0%, hyperglycemia: 10.0% | NCT02367456 | Sekeres et al. 67 |

| NEDD8-activating enzyme | Pevonedistat ± AZA | R/R HR-MDS | A:(pevonedistat 25 mg/m2): 3 B: (pevonedistat 44 mg/m2): 7 C: (Pevonedistat 10 mg/m2 + AZA 75 mg/m2): 3 D: (pevonedistat 20 mg/m2 + AZA 75 mg/m2): 10 |

I/Ib | B: ORR: 0%, C: ORR: 100%, D: ORR: 0% | A: febrile neutropenia: 66.7%, atrial fibrillation: 33.3%; B: febrile neutropenia: 57.1%, stomatitis: 57.1%, hypophosphatemia: 42.9%; C: anemia: 66.7%, constipation: 66.7%, injection site reaction: 66.7%; D: constipation: 70%, platelet count decreased: 50%, diarrhea: 40% | NCT02782468 | Handa et al. 76 |

| Pevonedistat + AZA | HR-MDS | 58 | II | ORR: 71%, CR: 45%, mOS: 21.8 m, EFS: 21.0 m | Pyrexia: 38%, cough: 38%, constipation: 36%, nausea: 24%, neutropenia: 34% | NCT02610777 | Sekeres et al. 77 | |

| Pevonedistat + AZA | HR-MDS | 161 | III | ORR: 24%, CR: 24%, median EFS: 19.2 m, mOS: 21.6 m | Anemia: 37%, constipation: 37%, neutropenia: 33%, nausea: 35%, thrombocytopenia: 33% | NCT03268954 | Ades et al. 78 | |

| Pevonedistat + AZA + VEN | HR-MDS | 6 | I/II | CR: 16.7%, SD: 16.7%, mDoR: 7.12 m | Hypophosphatemia: 15%, fatigue: 10%, increased ALT or AST: 10%, nausea or vomiting: 10% | NCT03862157 | Short et al. 79 | |

| SF3B1 | H3B-8800 | MDS, CMML, AML |

N = 84, 20 were HR-MDS Schedule 1: (5 days on/9 days off, range of doses studied 1–40 mg) 65 Schedule 2: (21 days on/7 days off, 7–20 mg) 19 |

I | CR: 0% | Schedule 1: diarrhea: 42%, nausea: 28%, fatigue: 17%, vomiting: 14% Schedule 2: diarrhea: 42%, vomiting: 21%, QTcF prolongation: 16%, nausea: 16%, dysgeusia: 11%, fatigue: 11%, and hypophosphatemia: 11% |

NCT02841540 | Steensma et al. 85 |

AEs, adverse events; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AZA, azacitidine; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; CR, complete response; DFS, disease-free survival; EFS, event-free survival; ENA, enasidenib; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HMAs, hypomethylating agents; HR, higher risk; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IDH1/2, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2; ITD, internal tandem duplication; IVO, ivosidenib; m, months; mCR, marrow CR; mDoR, median duration of response; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; mOS, median overall survival; N, number; NEDD8, neural precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 8; ORR, overall response rate; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; PR, partial response; QTcF, corrected QT interval; Ref, references; R/R, relapsed/refractory; SD, stable disease; SFS3B1, splicing Factor 3b subunit 1; TP53, tumor protein 53; TRAE, treatment-related AE; VEN, venetoclax; XPO1, exportin 1.

Table 2.

Novel targeted agents in ongoing clinical trials in elderly patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes.

| Target and pathway | Agent | Patient characteristics | Phase | Trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDH1 | IVO | HMAs naïve MDS | III | NCT06465953 |

| IVO + CPX-351 | HR-MDS | II | NCT04493164 | |

| IVO + Induction therapy and consolidation therapy | MDS-EB-2 | III | NCT03839771 | |

| IVO + VEN ± AZA | HR-MDS | Ib/II | NCT03471260 | |

| IDH2 | ENA + Induction therapy and consolidation therapy | MDS-EB-2 | III | NCT03839771 |

| BCL-2 | VEN + AZA | HR-MDS | III | NCT04401748 |

| VEN + AZA | HR-MDS (HMAs naïve or R/R) | I/II | NCT04160052 | |

| VEN + AZA tablets | HR-MDS (HMAs naïve, ineligible for HSCT) | I/II | NCT05782127 | |

| APG-2575 + AZA | Newly diagnosed HR-MDS | III | NCT06641414 | |

| XPO1 | Selinexor | HR-MDS after allo-SCT | I | NCT02485535 |

| Eltanexor + Decitabine-cedazuridine | HR-MDS | I/II | NCT05918055 | |

| Eltanexor + VEN | R/R MDS | I | NCT06399640 | |

| FLT3 | Quizartinib + Cladribine + Idarubicin + Cytarabine | HR-MDS | I/II | NCT04047641 |

| Quizartinib + Decitabine + VEN | HR-MDS | I/II | NCT03661307 | |

| Gilteritinib + ASTX727 + VEN | R/R HR-MDS (FLT3-mutated) | I/II | NCT05010122 | |

| Midostaurin + Decitabine | HR-MDS | II | NCT04097470 | |

| Luxeptinib | HR-MDS | I | NCT04477291 | |

| TP53 | Eprenetapopt + AZA | R/R HR-MDS (TP53-mutated) | I | NCT04638309 |

| APG-115 ± AZA or cytarabine | R/R MDS or AML | Ib | NCT04275518 | |

| RARα | Tamibarotene | HR-MDS | III | NCT04797780 |

| Tamibarotene ± Daratumumab/AZA | R/R HR-MDS | II | NCT02807558 | |

| Telomerase | Imetelstat | HR-MDS (HMA failure) | II | NCT05583552 |

allo-SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AZA, azacitidine; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; EB-2, excess blasts-2; ENA, enasidenib; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; HMAs, hypomethylating agents; HR, higher risk; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IDH1/2, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2; IVO, ivosidenib; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; RARα, the retinoic acid receptor alpha; R/R, relapsed/refractory; TP53, tumor protein 53; VEN, venetoclax; XPO1, exportin 1.

Figure 1.

An illustration depicting the mechanism and targets of novel drugs in older patients with HR-MDS.

AKT, protein kinase B; Bak, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer; Bax, Bcl-2 associated X protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HR, higher risk; IDH1/2, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2; IRAK4, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTP53, mutated tumor protein 53; MyD88, myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NAE, NEDD8-activating enzyme; NEDD8, neural precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 8; RA, retinoic acid; RARα, retinoic acid receptor alpha; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TLR, toll-like receptors; XPO1, exportin 1.

Mutated IDH1/2 inhibitor

IDH is an enzyme that plays a crucial role in essential cellular functions, including energy production, DNA modification, and adaptation to hypoxia. In cases of AML/MDS, mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 can result in the formation of an oncometabolite, (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate, which promotes leukemogenesis by inhibiting normal cellular differentiation. Moreover, these recurrent IDH mutations are found in approximately 20% of adult AML patients and 5% of adults with MDS. 9

Ivosidenib

Ivosidenib (AG-120, IVO), a novel targeted IDH1 inhibitor, has demonstrated efficiency in older patients with HR-MDS. In a phase I dose-escalation and expansion trial (NCT02074839), 12 patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) MDS (median age 72.5 years) carrying mutated IDH1 genes received a monotherapy of IVO. 10 Notably, 75% of patients achieved an overall response, with a median duration of response (mDoR) of 21.4 months, and there were no observed dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) or adverse events (AEs). Plus, nine patients (75%) achieved transfusion independence within 56 days of treatment. As a result of these findings, IVO has received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of IDH1-mutant R/R MDS, making it the first approved targeted therapy for this patient group. The study is ongoing for further evaluating its long-term clinical activity, tolerability and safety.

Caillet et al. investigated the efficacy and safety of IVO in IDH1-mutated MDS through the IDIOME phase II trial (NCT03503409). 11 The final results of the study published in 2024 showed that between March 2019 and February 2023, 48 patients with a median age of 76.5 years were enrolled across three cohorts: R/R HR-MDS (cohort A, n = 22), newly diagnosed HR-MDS (cohort B, n = 23), and erythropoietin-failed low-risk (LR-) MDS (cohort C, n = 3). In cohort A, IVO monotherapy achieved 63.6% overall response rate (ORR) after three cycles (21% CR and 7% partial response (PR)) with mDoR of 4.8 months and mOS of 8.9 months. The 12-month OS rate was 15.2%. In cohort B, the results demonstrated superior outcomes with 78.3% ORR (61% CR and 11% PR). Only three patients with AZA added to IVO without additional response. With median follow-up of 25.2 months, mOS and mDoR remained unreached, with 12-month OS of 91.3%. Five patients were successfully bridged to transplantation. In cohort C, two patients achieved CR (1 after 3 cycles and 1 after 9 cycles), with one patient maintaining CR through 20 cycles. IVO showed a favorable safety profile with 21 treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) in nine patients, primarily differentiation syndrome, which proved reversible in all cases. These findings demonstrate the significant efficacy and well-tolerance of IVO monotherapy across all IDH1-mutated MDS subtypes, with particularly promising results in treatment-naïve HR-MDS patients. The researchers concluded that IVO monotherapy represents a valuable first-line option for this population, including HSCT candidates, combining meaningful clinical responses with manageable toxicity.

Olutasidenib

Olutasidenib (FT-2102) is a novel, selective, and oral small-molecule inhibitor targeting on mutated IDH1. Although both olutasidenib and IVO are recognized as IDH1 inhibitors, they have not been directly compared in patients with MDS. Notably, studies in AML population comparing olutasidenib and IVO (albeit in different trials) have shown a substantially longer median duration of CR/CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh) with olutasidenib (25.9 months) 12 compared to IVO (8.2 months). 13 Consequently, the perspective has emerged that olutasidenib may exhibit superior potency, although additional research is essential to determine if the observed duration of response will translate into clinical benefit for patient. Focused on olutasidenib in MDS, preliminary results from a phase I/II trial (NCT02719574) assessed olutasidenib both as a standalone treatment and in combination with AZA in older patients with high or very high-risk MDS. 14 Patients were divided into two cohorts: monotherapy (nine patients, median age 72 years) and combination therapy (seven patients, median age 67 years). The monotherapy cohort showed an ORR of 33% and CR of 17%, while the combination group achieved an ORR of 86% and CR of 57%. The mDoR was not reached in either cohort (monotherapy: 95% confidence interval (CI): 6.7–not reached; combination: 12.8–not reached). In this first-in-human study, the initial findings above indicated encouraging clinical activity with both olutasidenib monotherapy and combination therapy. AEs were comparable across both groups, with AZA exerting minimal impact on the frequency or severity degree of MDS. However, the small sample size of the study necessitates further research to validate these outcomes. Furthermore, refining patient recruitment strategies is recommended to mitigate potential bias from the open-label design of the trial.

Enasidenib

IDH2 mutations are present in around 5% of MDS patients, leading to DNA and histone hypermethylation and blocking hemopoietic differentiation.

Enasidenib (AG-221, ENA), a mutated IDH2 inhibitor, can induce responses in patients with mutated IDH2 R/R MDS. In a multicenter, open-label, phase I/II trial (AG221-C-001, NCT01915498), 17 patients (median age 67 years) were treated with ENA. Among them, 18% relapsed after allo-HSCT, 59% had undergone at least two prior therapies, and 76% had prior HMAs exposure. The ORR was 53%, with a mDoR of 9.2 months. The mOS was 16.9 months, and the event-free survival (EFS) was 11.0 months. Diarrhea and nausea were the most common treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), with no treatment-related death reported. Despite these promising results, the small sample size and challenges of the study in monitoring allele frequency changes limit conclusions. 15 ENA is well-tolerated and is regarded as an off-label option in HR-MDS patients failing HMAs monotherapy or in combination therapy for frontline treatment. 16 A larger phase II study (NCT03383575) is ongoing, evaluating the use of ENA alone in IDH2-mutated HR-MDS patients who have not responded to HMAs and in combination with AZA for newly diagnosed IDH2-mutated HR-MDS patients. In the combination arm, 24 patients (median age 73 years) met the eligibility criteria, with ORR reaching 74% and a composite CR (CR + marrow CR (mCR)) rate of 70%. The median time to achieve the best response was 1.3 months, with an mOS of 26 months (range: 14–not evaluable), the mDoR is 32 months (95% CI: 20–not reached), and the median EFS was 11.7 months (95% CI: 6.5–not reached). While in the monotherapy arm, 20 qualified patients (median age 73 years) demonstrated an ORR of 35%, with a CR in 22%. The median time to initial response was 27 days, with the best response occurring at 4.6 months. The mOS was 20 months (range: 11–not reached), and the EFS was 6.5 months (95% CI: 5.4–21.4). The results firstly highlight the potential of ENA, both as a standalone therapy and in combination with AZA, for treating older IDH2-mutated HR-MDS patients, demonstrating promising safety and efficiency profiles. Neutropenia (40%), nausea (36%), constipation (32%), and fatigue (26%) were the most common TRAEs tested in the treating process. Additionally, challenges such as small population and limited predictive power from IPSS-R still persist. Notably, patients with ASXL1 mutations who received ENA monotherapy showed poorer survival, warranting further investigation. 17

Other mutated IDH1/2 inhibitors

A number of other new inhibitors targeting mutated IDH1/2 are under investigation for their potential in treating AML and MDS.

HMPL-306, a dual IDH1/2 inhibitor, has demonstrated significant therapeutic promise in IDH-mutated myeloid malignancies. In a multicenter phase I trial (NCT04272957), 49 patients (median age 63 years) with R/R myeloid leukemia or neoplasms were enrolled to assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of HMPL-306 across six dose-escalation cohorts followed by dose expansion. 18 Among them, the 250 mg QD cohort achieved an ORR of 42.9% in seven patients, with three achieved CR, leading to a recommended phase Ⅱ dose of 250 mg QD (Cycle 1), transitioning to 150 mg QD (Cycle 2) for optimized safety and sustained efficacy. As a compelling therapeutic candidate for patients with IDH-mutated HR-MDS and other myeloid malignancies, HMPL-306 offered the potential to address critical unmet needs in R/R cases. The ongoing dose-expansion studies (NCT04272957) will further validate its clinical utility and explore combination strategies. Additionally, a similar open-label phase I trial (NCT04764474) is evaluating the safety and efficacy of HMPL-306 in advanced or R/R AML, with results pending. 19 Moreover, the potential in the dual IDH1/2 inhibitors to overcome isoform switching, a resistance mechanism to both IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors has been observed in myeloid malignancies. 20 Isoform switching between mutant IDH1 and IDH2 represents a clinically significant mechanism of acquired resistance. Dual IDH1/2 inhibitors, by simultaneously targeting both mutant enzymes, have demonstrated the capacity to suppress oncogenic 2-hydroxyglutarate generation and overcome resistance mediated by enzyme isoform exchange. Preclinical models and emerging clinical data suggest that combinatorial blockade of IDH1 and IDH2 effectively abrogates isoform-switched enzymes, providing a compelling rationale for dual inhibition strategies to prevent or reverse resistance in myeloid malignancies harboring IDH mutations.

IDH305, a small-molecule inhibitor targeting mutated IDH1-R132 mutation, has shown promising anti-tumor activity in a phase I study (NCT02381886) with patients who had AML/MDS, gliomas, and other solid tumors. However, hepatotoxicity was noted, leading to the termination of three further subsequent clinical trials (NCT02987010, NCT02977689, NCT02826642) prior to enrollment, leaving its development uncertain. 21

LY3410738 is a selective covalent inhibitor of mutated IDH1-R132, designed to retain efficacy against second-site IDH mutations. 22 Currently, an open-label, global phase I trial is evaluating oral LY3410738 in R/R mutated IDH myeloid malignancies.

Developed independently by Wang et al., 23 SH1573 is an innovative mutated IDH2 inhibitor that has shown safety and efficacy in preclinical studies, leading to its clinical trial approval (CTR20200247) for AML. Future studies will explore its potential for MDS treatment.

In summary, while these IDH1/2 inhibitors offer promising avenues for treating AML and MDS, further clinical trials are needed to confirm their efficacy and determine their specific roles in HR-MDS therapy.

BCL-2 inhibitor

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) is an anti-apoptotic protein that can disrupt the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, contributing to the progression of MDS, particularly in advanced stages. 24 Consequently, targeting BCL-2 to stimulate apoptosis has become a promising therapeutic strategy for MDS treatment. 25

Venetoclax

Venetoclax is a powerful, selectively oral small-molecule BCL-2 inhibitor that induces apoptosis by binding to the BCL-2 homology 3-binding site. It was approved regularly in 2020 for treating newly diagnosed AML in adults aged 75 and above, in combination with AZA, DEC, or low-dose cytarabine (LDAC).26,27 The combination of HMAs and venetoclax has emerged as the de facto standard treatment for elderly or unfit patients with AML following the pivotal VIALE-A trial. 26 This phase III study demonstrated that in previously untreated AML patients ineligible for standard induction therapy due to advanced age (75 years or older), comorbidities, or both, AZA plus venetoclax significantly improved OS (14.7 months vs 9.6 months, p < 0.001) and composite CR (66.4% vs 28.3%, p < 0.001) compared to AZA monotherapy. Notably, responses were rapid, with 43.4% of patients achieving CR before cycle 2, and durable (mDoR of 17.5 months). The efficacy was observed across genomic subgroups, including those with adverse cytogenetic profiles. Both HR-MDS and AML demonstrate significant BCL-2 overexpression, which correlates with reduced apoptosis and poor clinical outcomes. The studies confirm BCL-2 as a critical therapeutic target in both diseases, with inhibitors effectively reducing blast counts and targeting leukemia-initiating cells in both conditions. Notably, BCL-2 inhibition represents a promising therapeutic approach for patients unable to tolerate intensive chemotherapy, providing a strong theoretical basis for BCL-2-targeted therapy across the MDS-AML disease spectrum.28,29 In light of the biological continuum between HR-MDS and AML, along with the limited responses of HMAs monotherapy in HR-MDS, these results suggest that adding venetoclax to HMA regimens may benefit HR-MDS patients, potentially improving response rates and survival outcomes.

A phase Ib multicenter trial (NCT02966782) evaluated venetoclax monotherapy versus combination therapy in patients with an average age of 74 years. Due to the limited efficacy, monotherapy was discontinued, but escalating doses of venetoclax (100–400 mg daily for 14 days in 28-day cycle) combined with AZA produced promising outcomes. In 44 patients with HMA failure, the combination therapy yielded a clinical response rate of up to 77%, with an mOS of 12.6 months. In addition, safety profiles were consistent with known venetoclax-related AEs, with no new toxicities identified. 30 Furthermore, researchers published the latest results about an ongoing open-label, multicenter, phase Ib study (NCT02942290) in March of 2025, demonstrated that 107 patients with a median age of 68 years were treated with the recommended phase II dose (venetoclax 400 mg for 14 days/28-day cycle with AZA 75 mg/m2 for 7 days/cycle). 31 The combination demonstrated robust efficacy with a CR rate of 29.9% and mCR of 50.5%, yielding an 80.4% modified ORR. Median time to CR was 2.8 months, with a median CR duration of 16.6 months. The mOS reached 26.0 months, with 1-year and 2-year survival rates of 71.2% and 51.3%, respectively. Among 59 patients with baseline transfusion dependence, 40.7% achieved transfusion independence. Moreover, 43% of patients proceeded to stem cell transplantation, higher than historical rates. The safety profile aligned with known effects of both agents, with key AEs including constipation (53.3%), nausea (49.5%), neutropenia (48.6%), and thrombocytopenia (44.9%). Additionally, it is mentioned that a phase III study VERONA (NCT04401748) is ongoing to confirm the survival benefit of this promising combination in newly diagnosed HR-MDS patients.

Building on the outcomes of the previous trials, several Phase II clinical trials (NCT05782127, NCT04812548) and phase III clinical trials (NCT04160052) are underway, continuing to explore venetoclax combined with AZA in elderly HR-MDS patients. Meanwhile, key areas for further research include determining the optimal dose ratio, minimizing the impact on drug resistance, 32 and mitigating AEs. With larger populations and ongoing research, these trials are expected to offer more definitive insights into the potential of venetoclax in HR-MDS therapy.

APG-2575

APG-2575 (lisaftoclax), a highly potent and selective orally bioavailable BCL-2 homology mimetic targeting BCL-2, 33 has recently shown promise in treating HR-MDS. In a phase Ib trial (NCT04501120) assessing the safety and pharmacokinetics of APG-2575 combined with AZA, 10 evaluable HR-MDS patients achieved an ORR of 70% and, with 60% achieving CR or mCR. These results suggest encouraging clinical efficacy for the combination therapy. 34 Furthermore, an ongoing pivotal phase III trial (GLORA-4, NCT06641414) has been approved by the Center for Drug Evaluation of China National Medical Products Administration to assess the efficacy of APG-2575 combined with AZA in newly diagnosed HR-MDS patients, offering a potentially significant treatment advance for this patient population.

XPO1 inhibitor

Selinexor

XPO1 (exportin-1), a nuclear export receptor, is crucial for exporting key proteins involved in tumor suppression and oncogenesis like tumor protein 53 (TP53), NF-κB, and RNA splicing components. 35 The overexpression of XPO1 is commonly observed in hematologic malignancies, including MDS and AML, and is linked to poor prognosis. 36

Selinexor (KPT-330), an oral, first-in-class selective XPO1 inhibitor, has shown promising responses in treating HR-MDS. A single-center, single-arm phase II trial (NCT02228525) was conducted to assess the activity and safety of selinexor monotherapy in HR-MDS patients. 35 The study enrolled 25 patients (median age 77 years), with 23 being evaluable. Most patients had previous exposure to AZA or DEC (median 13 prior cycles). The trial reported an ORR of 26% and stable disease in 52%, with a mDoR of 6.3 months. In the full cohort, the mOS was 8.5 months, with a 1-year survival rate of 28%. Among the 23 assessable patients, the mOS was 8.7 months (range: 7.2–15.0) with a 30% surviving probability of 1 year. The most frequent grade 3 or 4 AEs were thrombocytopenia and hyponatremia, with no serious TRAEs or deaths were occurred. This completed study was the first to demonstrate the efficacy of selinexor monotherapy in R/R MDS, which suggested that selinexor might offer a better option than supportive care alone for HR-MDS patients. Ongoing studies, such as a phase Ib trial (NCT02530476), are exploring selinexor alongside additional agents, such as FLT3 inhibitors, to further enhance its therapeutic potential in hematologic malignancies. 36 However, more research is required on this basis for exploring a likely solution for HR-MDS. A study conducted by Guo et al. 37 firstly revealed that selinexor combined with AZA synergistically inhibited MDS cell proliferation, induced apoptosis, and enhanced P53 function. To sum up, these findings highlight selinexor as a promising option for treating HR-MDS, whether as monotherapy or combined with other agents, warranting further clinical investigation in older patients.

Eltanexor

Eltanexor (KPT-8602), a second-generation oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export, has low penetrance into the central nervous system and has demonstrated good tolerability. 38 Recent designated as an orphan drug for MDS, it has shown promising results in clinical trials. 39 In a phase I/II trial (NCT02649790), 40 20 patients (median age 77 years) with HR-MDS refractory to HMAs were evaluated for safety and efficacy, and 19 out of 20 were considered high and HR-MDS by IPSS. Among the 15 patients assessable for efficacy, the ORR was 53.3%, consisting of seven patients who reached mCR and another patient exhibiting improvement in hematologic status. Additionally, three patients attained transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks. The mOS was 9.86 months, and no DLTs were reported. The most frequently reported TRAEs included nausea, diarrhea, and decreased appetite. Therefore, eltanexor demonstrates encouraging efficacy as a promising single agent with a positive safety record and survival benefit, positioning it as a potential treatment choice for HR-MDS. Plus, a now-recruiting phase I/II trial (NCT05918055) is investigating eltanexor with inqovi (DEC-cedazuridine) in patients with HR-MDS unresponsive to prior treatment. Additionally, a new phase I trial (NCT06399640) is assessing the safety and optimal dosage of eltanexor in conjunction with venetoclax for R/R MDS patients. The studies above highlight the potential of eltanexor as an emerging treatment for HR-MDS, with further trials anticipated to validate its efficacy.

HDAC inhibitors

The excessive presence of histone deacetylase (HDAC), a set of enzymes that regulates gene expression by controlling histone acetylation, contributes to the epigenetic changes involved in MDS pathogenesis.41,42 HDAC inhibitors (HADCi) have been investigated as potential treatments for MDS. Valproic acid, an anticonvulsant, was the first identified HADCi in MDS patients around 20 years ago. 43 However, single-agent valproic acid or its combination with other drugs like all-trans retinoic acid showed limited efficacy in HR-MDS. Pracinostat (SB939), a potent oral class Ⅰ pan-HDACi, has demonstrated moderate activity in early trials. In a phase I study (NCT00741234), pracinostat (60 mg, 3 day/week) combined with AZA achieved a 90% ORR in HR-MDS. 44 Nonetheless, a phase II double-blind study of pracinostat and AZA in treatment-naïve intermediate-2 or high-risk MDS patients (median age 69 years) reported higher treatment discontinuation due to AEs, particularly grade 3 fatigue and gastrointestinal side effects (63% in the pracinostat group vs 32% with placebo). 45 While the follow-up two-stage study (NCT03151304) using a lower dose of pracinostat met its two endpoint, showing a ⩽10% discontinuation rate and a ⩾ 20% ORR, demonstrating improved tolerability. 46 Mechanistically speaking, the combination of AZA and HDACi holds promise for improving outcomes in HR-MDS. 41 While preclinical studies suggested that HDACi could synergistically enhance the effects of HMAs, these theoretical advantages have not consistently translated to improved patient outcomes. The PRIMULA phase III trial (NCT03151408) provides a particularly instructive example of this translational gap. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study evaluated the efficacy and safety of pracinostat, an oral pan-HADCi, in combination with AZA in newly diagnosed AML patients unfit for standard induction chemotherapy. 47 Despite promising phase II results, the PRIMULA trial was terminated prematurely after interim analysis revealed no survival benefit with the addition of pracinostat to AZA (mOS: 9.95 months in both arms, p = 0.8275). Moreover, the pracinostat arm demonstrated a concerning trend toward higher early mortality, particularly between days 31 and 60 post-randomization, with more deaths attributed to AEs (26.9% vs 18.9%) compared to the control arm. These findings underscore the significant challenges in developing effective HDACi-based therapies for AML, suggesting that further investigation into specific molecular contexts where HDACi may prove beneficial, optimal dosing strategies to mitigate toxicity, and more selective targeting approaches may be necessary before HDACi can realize their theoretical potential in AML treatment. Additionally, multiple randomized clinical trials of other HDACi such as vorinostat, panobinostat, and entinostat have demonstrated disappointing outcomes. The North American Intergroup Study SWOG S1117 showed that AZA plus vorinostat yielded lower response rates (27% vs 38%) compared to AZA monotherapy and failed to improve survival metrics in HR-MDS and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia patients. 48 Similarly, a phase Ib/IIb multicenter study of panobinostat plus AZA revealed no significant improvement in 1-year OS (60% vs 70%) or time to progression despite marginally higher composite complete response rate (CRR), while demonstrating increased toxicity with more grade 3/4 AEs (97.4% vs 81.0%) and on-treatment deaths. 49 The E1905 trial showed that AZA plus entinostat was associated with significantly lower response rates than AZA monotherapy (17% vs 46%) and shorter mOS (6 months vs 13 months), with excessive treatment discontinuation due to toxicity. 50 These consistent findings across multiple HDACi agents highlight the need to temper expectations for this combinatorial approach. To conclude, a series of trials and research indicated that some challenges and problems were manifested from the outcome toward the treatment of HDACi combined with AZA. These findings temper the expectations for future developments in HDACi treatment of HR-MDS. We suggest that future research should focus on refining patient selections using predictive biomarkers and optimizing HDACi dosing regimens to potentially identify specific contexts where HDACi-AZA therapy might benefit elderly HR-MDS patients. Through these refined approaches, it remains possible that specific contexts may exist where HDACi could provide clinical benefit, though expectations should remain appropriately cautious pending robust clinical evidence.

FLT3 inhibitors

Quizartinib

FLT3 mutations, a known resistance mechanism to HMAs, are present in up to 19% of patients at HMA failure. Quizartinib, a strong and specific FLT3 inhibitor, has exhibited clinically meaningful survival benefits in combination with chemotherapy for patients with FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD)-positive AML through the phase III QuANTUM-First trial (NCT02668653). Key outcomes included a prolonged mOS (31.9 months vs 15.1 months; hazard ratio (HR) 0.78), a 55% CR rate for a median duration of 38.6 months, and reduced relapse risk. Based on these findings, the drug received regulatory approval from FDA in July 2023 for newly diagnosed FLT3-ITD-positive AML in adults. 51 Its ability to target FLT3-ITD mutations and suppress measurable residual disease underscores its potential in HR-MDS, particularly for subsets harboring FLT3 aberrations. Additionally, considering the favorable safety profile and efficacy of quizartinib in older AML patients (up to 75 years), its applicability in elderly population with HR-MDS merits further exploration and validation. In a phase I trial (NCT04493138), 12 participants (median age 73 years, 7 of them harbored FLT3-ITD mutations) suffering from R/R MDS were enrolled to investigate the therapeutic effect of quizartinib combined with AZA. Of these patients with FLT3-ITD mutations, six fell into the intermediate, high, and very high-risk categories by IPSS-R, and none had prior FLT3 inhibitor exposure. All older patients with FLT3-ITD mutations responded (ORR: 100%) with a CR of 14%. Mutation clearance was achieved in 57% (4/7) of patients with FLT3-ITD mutations, while the rest experienced a decrease in allele burden. The mOS and leukemia-free survival were not reached (95% CI: not calculatable), with a median relapse-free survival of 14.6 months. Based on these data, quizartinib demonstrated promising safety and efficiency in these older MDS patients, with response rates exceeding those seen with AZA monotherapy and other FLT3 inhibitors.52,53 TEAEs were common, including fatigue (67%), constipation (67%), cough (50%), insomnia (50%), anorexia (50%), arthralgia (50%), and diarrhea (50%). The results above supported further investigation through ongoing phase II research to confirm the role of quizartinib in treating FLT3-mutated MDS in older adults.

Other FLT3 inhibitors

The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family encompasses a set of serine/threonine kinases (IRAK1-4) that play a role in inflammatory reactions mediated by the interleukin-1 receptor and toll-like receptors. 54 Recently, in about 50% cases of MDS cases with U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1 gene (U2AF1) or splicing factor 3b subunit 1 (SF3B1) mutations, an overexpression of the oncogenic long isoform (IRAK4-L) has been linked to disease progression by promoting chronic inflammation in the bone marrow microenvironment and correlates with a poorer prognosis.55,56 CA-4948 (emavusertib), a groundbreaking oral agent that simultaneously targeting both FLT3 and IRAK4, has shown favorable tolerability and efficiency in elderly patients with heavily pretreated AML and HR-MDS in an ongoing phase I/IIa trial (NCT04278768). Patients received CA-4948 monotherapy (200–500 mg BID, RP2D: 300 mg BID) or in conjunction with AZA or venetoclax. 57 Among the seven HR-MDS patients carrying spliceosome mutations, 57% achieved mCR. In contrast, only 1 of 29 patients lacking spliceosome mutations reached CR, with two achieved partial remission. 57 Additionally, CA-4948 demonstrated good tolerability without DLTs, making it a promising candidate for combination therapy in elderly HR-MDS patients. Currently, further research is required to confirm its safety and effectiveness. Future studies should focus on optimizing trial designs to confirm these encouraging preliminary results.

While only a limited number of trials (NCT05010122, NCT04097470) centered on the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors like gilteritinib, midostaurin, and sorafenib in HR-MDS, the ongoing investigations into IRAK4-targeted strategies highlight the need for expanding therapeutic options for this challenging population.

Mutated TP53 inhibitor

Eprenetapopt (APR-246)

In higher-risk elderly MDS patients, TP53 mutations are present in 2%–10% of cases.58–60 Among all the somatic mutations found in MDS, TP53 mutations link to the worst prognosis, including a 2-year OS rate of only 12.8%, 61 rapid resistance to HMAs, chemotherapy, and frequent transformation to AML. Eprenetapopt (APR-246), a prodrug that purportedly reactivates mutant p53 function and disrupts the cellular redox equilibrium, has shown mixed clinical outcomes in targeting these cancer vulnerabilities. In combination with AZA, eprenetapopt yielded positive tolerability and remission rates in two parallel phase II clinical trials in older HR-MDS patients with TP53 mutations. Within the study (NCT03072043), a response rate of 73% was observed among patients (median age 66 years) who responded, including 50% who reached CR and 58% showing a cytogenetic response, resulting in an mOS of 10.4 months. 62 In a separate investigation (NCT03588078) with a median age of 74 years, an ORR of 62% was documented, featuring 47% CR and an mDoR of 12.1 months. 60 Common neurologic side effects, such as dizziness and peripheral neuropathy, were reversible with drug discontinuation in these two studies. However, a phase III randomized trial (NCT03745716) combining eprenetapopt with AZA did not achieve its primary goal of a specific CR rate, despite the combination therapy arm saw a 53% increase in the rate of CR. Furthermore, the phase II post-transplant maintenance trial (NCT03931291) evaluating eprenetapopt in conjunction with AZA in patients with TP53-mutated MDS/AML reported a median relapse-free survival of 12.5 months and an OS of 20.6 months, 63 though these outcomes appear comparable to historical transplant data in TP53-mutant AML in a multicenter retrospective analysis, with the median EFS of 12.4 months and the mOS of 24.5 months. 64 Notably, the mechanism of eprenetapopt remains debated. Eprenetapopt was initially characterized as a mutant p53 reactivator by restoring its tumor-suppressing wild-type structure, while emerging evidence suggests that the effects of eprenetapopt may derive from p53-independent mechanisms. Specifically, it depletes glutathione, disrupting cellular antioxidant defenses of the tumor and triggering ferroptosis (an iron-dependent cell death pathway). 65 Moreover, the developmental landscape of TP53-targeted therapies faces setbacks, with both APR-548 and the CD47 inhibitor magrolimab halting clinical development. APR-548, previously under investigation for myeloid malignancies (NCT04638309), was discontinued due to insufficient efficacy in early-phase trials. Similarly, the phase III ENHANCE-3 trial (NCT05079230) of magrolimab for MDS/AML was terminated in 2024 owing to futility and elevated mortality risks linked to infections and respiratory failure. These discontinuations underscore the challenges in targeting TP53-driven pathways and highlight the need for novel therapeutic strategies. Fang et al. demonstrated in their 2021 study that APG-115, a potent oral mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) inhibitor, disrupts MDM2-P53 interaction in HR-MDS where MDM2 is frequently overexpressed, therefore restoring the function of P53. This restoration of P53 function induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, thereby reactivating the tumor-suppressing function. The researchers found enhanced efficacy when APG-115 was combined with HMAs through complementary DNA damage signaling and DNMT1 inhibition. 66 Additionally, in their paper, Fang et al. referenced a phase Ib, open-label (NCT04275518) trial, which evaluates APG-115 alone and in combination with AZA or cytarabine in R/R HR-MDS and AML patients. While still recruiting, the trial aims to investigate the safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic profiles of APG-115 as monotherapy or combination therapy.

Despite initial promise, TP53-targeted therapies face significant challenges, with eprenetapopt showing mixed efficacy, mechanistic uncertainties between p53 reactivation and ferroptosis induction, and recent discontinuations of APR-548 and magrolimab due to efficacy/safety concerns, underscoring the complexity of effectively targeting TP53-driven pathways in myeloid malignancies.

Hedgehog pathway inhibitor

Glasdegib

Glasdegib (PF-04449913) is an inhibitor targeting the Hedgehog pathway, which is crucial in embryogenesis and whose aberrations are linked to leukemia stem cells. In a phase Ib multicenter, open-label trial (NCT02367456) combining glasdegib and AZA in elderly individuals with newly diagnosed HR-MDS as well as the other hematological tumors, safety, and efficacy were evaluated. 67 Two cohorts were included: a lead-in safety (LIS) cohort (n = 12) and an MDS cohort (n = 30). The median ages were 72 and 74 years, with median treatment duration of 2.7 and 4.7 months, respectively. Glasdegib exposure lasted for a median of 3.5 and 5 cycles in the LIS and MDS cohorts. In the LIS cohort, 16.7% achieved mCR, while the MDS cohort had an ORR of 33.3% and an mCR of 15.7%. Four patients achieved CR, exhibiting a median time to response of 0.6 months and the mDoR and the mOS of 6.2 and 15.8 months, respectively. The most frequently reported non-hematologic TEAEs (⩾10%) included sepsis, diarrhea, hypotension, pneumonia, and hyperglycemia, with grade 3/4 AEs in 66.7% of the LIS cohort. Despite these, glasdegib was well-tolerated, suggesting further studies of glasdegib combined with AZA for patients with HR-MDS may be warranted. An another multicenter, open-label, phase Ib/II trial (NCT01546038) combining glasdegib with LDAC in AML and HR-MDS patients showed a survival benefit, with a reduced HR compared to LDAC alone. 68 In this phase III clinical trial, 5 out of 69 subjects had HR-MDS. The study demonstrated that MDS patients achieved a CRR of 40% (80% CI: 11.9–68.1), with an mOS of 13.0 months (80% CI: 11.0–15.6). This combination therapy was then mainly studied in a phase III BRIGHT AML 1019 trial (NCT03416179) in 2023 with the aim of evaluating the efficacy and safety of glasdegib combined with other chemotherapy. 69 However, this research did not include the HR-MDS patients, and it was mostly focused on the treatment for untreated AML. Moreover, the study failed to meet the primary efficacy endpoint and pointed out that the combination therapy based on the glasdegib showed no significant improvement of OS in untreated AML patients. Apart from the combination therapy, a single-center, open-label, two-stage phase II trial of glasdegib monotherapy in older patients with refractory MDS indicated that while single-agent activity was limited, it was well-tolerated, and patients achieving standard deviation showed a prolonged survival. 70 These findings highlight the potential for combination therapies involving glasdegib and even monotherapy. Glasdegib was granted orphan drug designation by the US FDA for AML in June 2017 and for MDS in October 2017, followed by approval in 2018 for use with LDAC in newly diagnosed AML patients who are aged 75 years and older, or who are not candidates for intensive induction chemotherapy. 71 In conclusion, glasdegib manifests promise as a treatment for MDS and AML, particularly in combination therapies. While some trials have included older HR-MDS patients, additional research is essential to elucidate its specific function and outcomes within this population.

Telomerase inhibitor

Imetelstat

Imetelstat (RYTELO™), a first-in-class telomerase inhibitor, has emerged as a novel therapeutic approach for LR-MDS, with promise being developed for future use in HR-MDS populations. As a 13-mer oligonucleotide covalently linked to a lipid moiety, imetelstat targets the RNA template of human telomerase and thereby inhibits telomere elongation in malignant clones. 72 This mechanism selectively induces apoptosis in dysplastic hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells while sparing normal counterparts, offering a unique disease-modifying potential distinct from HMAs or erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs).72,73 The IMerge phase I trial (NCT02598661) established the robust efficacy of imetelstat in transfusion-dependent, LR-MDS patients refractory to ESAs, with 39.8% of patients achieving ⩾8-week transfusion independence (median duration: 1.5 years). 74 Imetelstat was granted FDA approval in June 2024 for LR-MDS with heavy transfusion burden who are not responsive or have lost response to ESAs. The success of imetelstat in LR-MDS has spurred interest in its application for HR-MDS patients. Ongoing study, such as the phase II IMPress study (NCT05583552), aims to validate its potential in population with R/R HR-MDS/AML. In conclusion, the unique mechanism and disease-modifying potential of imetelstat position it as a cornerstone for future strategies in both low- and high-risk MDS. We believe that further advancements will be brought out, with further research centering on the imetelstat treatment in patients with HR-MDS being implemented.

NAE inhibitor

Pevonedistat

The activation of neuronal precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated protein-8 (NEDD8) by NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) is the key initial step in protein neddylation, a significant pathway in tumorigenesis. 75

Pevonedistat (MLN4924), a novel intravenously administered NAE inhibitor, is being studied as both a monotherapy and in conjunction with AZA for treating AML and MDS. In a phase I/Ib trial (NCT02782468) involving East Asian individuals with intermediate- to very high-risk AML or MDS, the combined treatment regimen achieved a 45% objective response rate, while the monotherapy group was ineffective. 76 A phase II randomized trial (NCT02610777) demonstrated that the combination of pevonedistat and AZA had promising clinical efficacy in HR-MDS patients, yielding clinically meaningful increases in OS (23.9 months vs 19.1 months, p = 0.24), improved EFS (20.2 months vs 14.8 months, p = 0.045), a nearly doubled CR rate (51.7% vs 26.7%), and an almost tripled the mDoR (34.6 months vs 13.1 months) compared to AZA alone, with comparable safety. The most common grade 3 or higher TEAEs were neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. 77 However, the larger, global, randomized phase III PANTHER study (NCT03268954) did not replicate these promising results, showing no significant improvement in EFS (19.2 months vs 15.6 months) 78 or OS (21.6 months vs 17.5 months) in HR-MDS. Despite this, pevonedistat remains a hopeful addition for combination therapy for its tolerable safety characteristics and its impact on various cellular regulatory pathways that are vital for cancer cell viability. In a phase I/II clinical trial (NCT03862157), the triple therapy of AZA, venetoclax, and pevonedistat demonstrated activity in elderly HR-MDS patients who had previously not responded to HMAs treatment, suggesting the potential role of Pevonedistat to enhance the venetoclax treatment regimen. 79

Spliceosome inhibitor

H3B-8800

In MDS, around 50% of patients harbor somatic mutations in spliceosome genes, 80 with the SF3B1 among the most frequently mutated ones. Research revealed that spliceosome mutations are not viable in a homozygous state, 81 and the presence of the wild-type gene allele is necessary for cell survival with splicing factor mutations. 82 Based on the rationale, spliceosome inhibitors like E7107 and H3B-8800 have been investigated as potential treatments for MDS characterized by splicing factor mutations. 83 Clinical studies of E7107 were halted due to its association with severe vision loss. 84 H3B-8800 (RVT-2001), an orally bioavailable small-molecule targeting the SF3b complex, underwent a phase I dose-escalation trial (NCT02841540) involving 84 participants, including 20 patients with HR-MDS and 88% with splicing mutations. 85 The study established a daily dose of 30 mg (5 days on, 9 days off) and 14 mg (21 days on, 7 days off) for future trials. The main AEs linked to SF3B1 treatment are acceptable, including diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, vomiting, and prolonged QT interval. The trial, however, failed to yield any CRs or PRs based on International Working Group criteria, suggesting further research on alternative dosing regimens is needed. Moreover, recent findings indicate that MDS patients with cohesion mutations (present in 11% of cases) 86 are more responsive to spliceosome-targeting drugs like H3B-8800 when combined with chemotherapy or poly ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors, offering a new avenue for treating MDS with cohesion mutations. 87

The RARα agonist

Tamibarotene

The retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) gene encodes RARα, a ligand-regulated nuclear receptor controlling myeloid differentiation. Overexpression of RARα prevents myeloid differentiation, promoting an immature proliferative state. Additionally, a super enhancer linked to RARα overexpression is found in 50% of MDS and 30% of non-acute promyelocytic leukemia AML cases. 88 Tamibarotene (SY-1425), a potent and highly selective oral RARα agonist, binds to unliganded RARα receptors, activating transcription, restoring myeloid differentiation, inhibiting blast cell proliferation, and promoting blast cell elimination in AML and MDS. This makes tamibarotene a novel approach for RARα-overexpression R/R AML or HR-MDS. In a phase II study (NCT02807558), tamibarotene combined with AZA was proven to be both well-tolerated and effective for elderly patients with RARα-positive AML, especially in low-blast count AML.88,89 These promising findings backed the ongoing phase III trial (NCT04797780) examining tamibarotene for HR-MDS patients with RARα overexpression. 90 In short, although data on tamibarotene in HR-MDS remains limited, its success in AML trials encourages future studies to pioneer understanding of their correlation and explore its potential in RARα-overexpressing MDS.

Conclusion

The prognosis of older adults aged 60 years or older with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (HR-MDS, IPSS-R score ⩾3.5) remains a significant clinical challenge, necessitating the development of more effective and less toxic therapeutic strategies. With deeper insights into the genetic and biological heterogeneity of MDS, novel small-molecule targeted therapies, which have unparalleled strengths like their oral administration feasibility and economical scalability, have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional treatments, particularly for patients who are ineligible for intensive therapies like allo-HSCT. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the evolving treatment landscape, summarizing the efficacy and limitations of these agents in the context of HR-MDS management. Our analysis highlights that both monotherapy and combination regimens involving IDH1/2 inhibitors, BCL-2 inhibitors (venetoclax), and XPO1 inhibitors have demonstrated favorable clinical outcomes, with some already approved or under FDA review for HR-MDS treatment. Additionally, HDAC, FLT3, TP53, and NAE inhibitors have yielded promising results in early-phase clinical trials, warranting further investigation to validate their feasibility and therapeutic potential. Furthermore, Hedgehog pathway inhibitors, spliceosome inhibitors, and even RARα agonists represent innovative approaches targeting the molecular complexity of HR-MDS, offering new possibilities for patients who are ineligible for allo-HSCT. While this review emphasizes the application of novel small-molecule targeted therapies in MDS, it is critical to acknowledge the concurrent development of several large-molecule agents, such as CD-47-targeted therapies (e.g., gentulizumab, AK117, IMM01, and SL-172154), which have entered active clinical evaluation and represent a promising therapeutic frontier. These findings underscore a paradigm shift toward molecularly informed treatment approaches that promise to revolutionize therapeutic algorithms for HR-MDS. As the prevalence of HR-MDS continues to rise within an aging demographic, the successful translation of these advances into clinical practice faces two critical imperatives: the systematic integration of novel therapeutic agents into standard care protocols and the expansion of clinical research to encompass a more representative elderly patient population.

In summary, advanced developments have been made in novel small-molecule therapies for HR-MDS, showing the promising future for elderly patients with HR-MDS who could not afford allo-HSCT. The continued refinement of precision medicine strategies grounded in the molecular characterization of HR-MDS holds the potential to meaningfully improve both survival outcomes and quality of life for this vulnerable high-risk population.

Limitations

Despite the progress made, significant challenges remain. There was also a substantial proportion of newly investigational drugs (e.g., volasertib, rigosertib, and galunisertib) failing to progress beyond clinical trials due to their insufficient efficacy, the unmanageable toxicity profiles, and so on. Moreover, the long-term efficacy, safety, and resistance mechanisms of these novel agents lack further validation through large-scale, randomized controlled trials with extended follow-up, particularly in the older patient population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all those who provided support and encouragement, which facilitated the completion of this article. Additionally, the authors would like to appreciate the opportunities and efforts provided by the organization of 930.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Kehao Hou  https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1869-8420

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1869-8420

Xue Dong  https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5119-2599

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5119-2599

Wenyan Niu  https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0962-9715

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0962-9715

Contributor Information

Kehao Hou, Qingdao University Qingdao Medical College, Qingdao, Shandong, China.

Xue Dong, Qingdao University Qingdao Medical College, Qingdao, Shandong, China.

Wenyan Niu, Department of Hematology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, 16 Jiangsu Road, Qingdao, Shandong 266000, China.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (Approval Number: QYFYWZLL29279). The consent to participate is not applicable. As a review article synthesizing existing published literature, this study did not involve recruitment or direct participation of any human subjects.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Kehao Hou: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Xue Dong: Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Wenyan Niu: Methodology; Supervision; Validation.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during this study.

References

- 1. Cassanello G, Pasquale R, Barcellini W, et al. Novel therapies for unmet clinical needs in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14(19): 4941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weller J F, Lengerke C, Finke J, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients aged 60–79 years in Germany (1998–2018): a registry study. Haematologica 2024; 109(2): 431–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Santini V. Advances in myelodysplastic syndrome. Curr Opin Oncol 2021; 33(6): 681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kewan T, Stahl M, Bewersdorf JP, et al. Treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes for older patients: current state of science, challenges, and opportunities. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2024; 19(3): 138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saygin C, Carraway HE. Current and emerging strategies for management of myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Rev 2021; 48: 100791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hochman MJ, DeZern AE. SOHO state of the art updates and next questions: an update on higher risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2024; 24(9): 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jain AG, Ball S, Aguirre L, et al. Patterns of lower risk myelodysplastic syndrome progression: factors predicting progression to high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2024; 109(7): 2157–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brunner AM, Leitch HA, van de Loosdrecht AA, et al. Management of patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Cancer J 2022; 12(12): 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medeiros BC, Fathi AT, DiNardo CD, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations in myeloid malignancies. Leukemia 2017; 31(2): 272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiNardo CD, Roboz GJ, Watts JM, et al. Final phase 1 substudy results of ivosidenib for patients with mutant IDH1 relapsed/refractory myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood Adv 2024; 8(15): 4209–4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caillet A, Simonet-Boissard M, Forcade E, et al. IDALLO study: a retrospective multicenter study of the SFGM-TC evaluating the efficacy and safety of ivosidenib in relapsed IDH1-mutated AML after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. HemaSphere 2024; 8(3): e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Botton S, Fenaux P, Yee K, et al. Olutasidenib (FT-2102) induces durable complete remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory IDH1-mutated AML. Blood Adv 2023; 7(13): 3117–3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, et al. Durable remissions with ivosidenib in IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(25): 2386–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watts JM, Baer MR, Yang J, et al. Olutasidenib alone or with azacitidine in IDH1-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: phase 1 results of a phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2023; 10(1): e46–e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stein EM, Fathi AT, DiNardo CD, et al. Enasidenib in patients with mutant IDH2 myelodysplastic syndromes: a phase 1 subgroup analysis of the multicentre, AG221-C-001 tria. Lancet Haematol 2020; 7(4): e309–e319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohty R, Al Hamed R, Bazarbachi A, et al. Treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes in the era of precision medicine and immunomodulatory drugs: a focus on higher-risk disease. J Hematol Oncol 2022; 15(1): 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DiNardo CD, Venugopal S, Lachowiez C, et al. Targeted therapy with the mutant IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib for high-risk IDH2-mutant myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood Adv 2023; 7(11): 2378–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu L, Zhao W-L, Wu W, et al. P539: A phase 1 study of HMPL-306, a dual inhibitor of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 and 2, in Pts with relapsed/refractory myeloid hematological malignancies harboring IDH1 and/or 2 mutations. HemaSphere 2023; 7(S3): e86312d3. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doraiswamy A, Jayaprakash V, Kania M, et al. A phase 1, open-label, multicenter study of HMPL-306 in advanced hematological malignancies with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations. Blood 2021; 138: 4438. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harding JJ, Lowery MA, Shih AH, et al. Isoform switching as a mechanism of acquired resistance to mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase inhibition. Cancer Discov 2018; 8(12): 1540–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Megías-Vericat JE, Ballesta-López O, Barragán E, et al. IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML: current challenges and future prospects. Blood Lymphat Cancer 2019; 9: 19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stein E M, Konopleva M, Gilmour R, et al. A phase 1 study of LY3410738, a first-in-class covalent inhibitor of mutant IDH in advanced myeloid malignancies (trial in progress). Blood 2020; 136: 26. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Z, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. Preclinical efficacy against acute myeloid leukaemia of SH1573, a novel mutant IDH2 inhibitor approved for clinical trials in China. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021; 11(6): 1526–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blum S, Tsilimidos G, Bresser H, et al. Role of Bcl-2 inhibition in myelodysplastic syndromes. Int J Cancer 2023; 152(8): 1526–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuszczak B, Wrobel T, Wicherska-Pawlowska K, et al. The role of BCL-2 and PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndromes. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24(5): 4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2020; 383(7): 617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wei AH, Montesinos P, Ivanov V, et al. Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Blood 2020; 135(24): 2137–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tiribelli M, Michelutti A, Cavallin M, et al. BCL-2 expression in AML patients over 65 years: impact on outcomes across different therapeutic strategies. J Clin Med 2021; 10(21): 5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gorombei P, Guidez F, Ganesan S, et al. BCL-2 inhibitor ABT-737 effectively targets leukemia-initiating cells with differential regulation of relevant genes leading to extended survival in a NRAS/BCL-2 mouse model of high risk-myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22(19): 10658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeidan AM, Borate U, Pollyea DA, et al. A phase 1b study of venetoclax and azacitidine combination in patients with relapsed or refractory myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol 2023; 98(2): 272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garcia J S, Platzbecker U, Odenike O, et al. Efficacy and safety of venetoclax plus azacitidine for patients with treatment-naive high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2025; 145(11): 1126–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ong F, Kim K, Konopleva MY. Venetoclax resistance: mechanistic insights and future strategies. Cancer Drug Resist 2022; 5(2): 380–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deng J, Paulus A, Fang DD, et al. Lisaftoclax (APG-2575) is a novel BCL-2 inhibitor with robust antitumor activity in preclinical models of hematologic malignancy. Clin Cancer Res 2022; 28(24): 5455–5468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang H, Wei X, Jiang Q, et al. Safety and efficacy of lisaftoclax (APG-2575), a novel BCL-2 inhibitor (BCL-2i), in relapsed or refractory (R/R) or treatment-naïve (TN) patients (Pts) with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic SYNDROME (MDS), or other myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1): 2925. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taylor J, Mi X, Penson AV, et al. Safety and activity of selinexor in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or oligoblastic acute myeloid leukaemia refractory to hypomethylating agents: a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2020; 7(8): e566–e574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang W, Ly C, Ishizawa J, et al. Combinatorial targeting of XPO1 and FLT3 exerts synergistic anti-leukemia effects through induction of differentiation and apoptosis in FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemias: from concept to clinical trial. Haematologica 2018; 103(10): 1642–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guo Y, Liu Z, Duan L, et al. Selinexor synergizes with azacitidine to eliminate myelodysplastic syndrome cells through p53 nuclear accumulation. Invest New Drugs 2022; 40(4): 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chari A, Vogl DT, Gavriatopoulou M, et al. Oral selinexor-dexamethasone for triple-class refractory multiple myeloma. New Engl J Med 2019; 381(8): 727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chaudhry S, Beckedorff F, Jasdanwala SS, et al. Altered RNA export by SF3B1 mutants confers sensitivity to nuclear export inhibition. Leukemia 2024; 38: 1894–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee S, Mohan S, Knupp J, et al. Oral eltanexor treatment of patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome refractory to hypomethylating agents. J Hematol Oncol 2022; 15(1): 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Badar T, Atallah E. Do histone deacytelase inhibitors and azacitidine combination hold potential as an effective treatment for high/very-high risk myelodysplastic syndromes? Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021; 30(6): 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Quintas-Cardama A, Santos FP, Garcia-Manero G. Histone deacetylase inhibitors for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2011; 25(2): 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gottlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, et al. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J 2001; 20(24): 6969–6978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abaza YM, Kadia TM, Jabbour EJ, et al. Phase 1 dose escalation multicenter trial of pracinostat alone and in combination with azacitidine in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Cancer 2017; 123(24): 4851–4859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]