Abstract

The production of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypothalamus) has increased worldwide; recently, it was farmed with Nile tilapia in polyculture farms. Polyculture systems and water temperature (25℃ and 33℃) could affect Edwardsiella tarda infection, antibiotic efficacy, and residues. Moribund fishes were collected from three Farms 1–3: Farm 1 (monoculture, Nile tilapia), Farm 2 (monoculture, striped catfish), and Farm 3 (polyculture). Four E. tarda, LAMSH1, and LAMAH2-4 were isolated, whereas LAMAH3 was isolated from both fish spp., where striped catfish were highly susceptible to infection. The obtained E. tarda, which was isolated from striped catfish, has a significantly lower LD50 than those retrieved from Nile tilapia, and co-infection occurred only in striped catfish on Farm 3. The infection was screened and confirmed by gyrB1 gene presence while detecting the cds1, pvsA, and qseC genes indicated virulence. All isolates were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and florfenicol but showed resistance to a high number of other antibiotics, resulting in high multi-drug resistant (MDR) indices exceeding 0.2, except for strain LAMAH4, which had an index of 0.18.

Analyses of farms water revealed high ammonia compounds total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), unionized ammonia (NH3), nitrite (NO2), and nitrate (NO3) in Farm 2 (monoculture, striped catfish), and the recorded significantly higher concentrations were 2.75, 0.29, 0.24, and 2.01 mg/L, respectively, which were compared with Farm 1 and Farm 3. In the indoor experiment, at high water temperatures (33 °C), Nile tilapia and striped catfish had a high mortality rate and re-isolation of E. tarda (10–20%) compared to those exposed to low water temperatures (25 °C). These observations were concurrent with low antibiotic residues in their hepatic tissues. Despite water temperature, Nile tilapia showed higher ciprofloxacin residues than striped catfish.

The study concluded that striped catfish are more susceptible to the bacteria E. tarda compared to Nile tilapia, particularly in polyculture farms, which resulted in a higher infection rate. Both Nile tilapia and striped catfish exposed to elevated water temperatures exhibited increased vulnerability to bacterial infections. Additionally, these fish showed a high re-isolation rate of E. tarda while having low ciprofloxacin residues in their hepatic tissues.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-04232-9.

Keywords: Pangasianodon hypothalamus, Oreochromis niloticus, Edwardsiella tarda, Antibiotic residue

Introduction

More than 156 million tons of fish products are supplied to the global market year-based, and aquaculture production covers about 46% of human consumption [1]. Within Africa, Egyptian production formed approximately 70% of aquaculture crops, with about 1.57 million tons in 2021 [2]. The Egyptian fish farms are mainly located in the northern Nile River delta, around and south of the freshwater lakes; local markets consume these productions with low exports. Kafrelsheikh governorate has the highest number of fish farms and hatcheries, making about half of national production [3].

Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) form about 67% of the Egyptian aquaculture harvest, mainly produced in semi-intensive earthen ponds (3 to 5 acres in area) and fed commercial ration (crude protein, 25%). In Egypt, fish farms depend on polyculture systems Nile tilapia, African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), thin lip mullet (Mugil capito), and gray mullet (Mugil cephalus) [4]. However, the expansion of fish production uses large amounts of formulated diets, wastes, and uneaten feed turned into free ammonia and phosphorus, especially in warm-water aquaculture [5]. Usually, the intensification of aquatic animal production is correlated with infectious disease outbreaks such as bacterial diseases, which raise the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [6, 7]. Edwardsiellosis is the most common disease in catfish farms, and it could infect both farmed and wild fish, causing high financial loss. Moreover, the causative agent is E. tarda, a highly pathogenic bacterium belonging to Enterobacteriaceae with a wide range of hosts and countries; many virulence genes increase its survivability and pathogenicity [8]. This bacterium is a Gram-negative bacillus and has five pathogenic species: E. tarda, E. ictaluri, E. piscicida, E. hoshinae, and E. tarda [9–11]. Edwardsiella isolates showed many phenotypic and interspecific diversity recovered from different countries and host kinds; therefore, rapid, accurate, and specific confirmation of the causative agents is a fundamental step for controlling disease and epizootiological investigations [12]. The infection of E. tarda has been found in C. gariepinus [13], P. pangasius [14], and Nile tilapia [15].

This study discusses the impact of introducing a new member to Egyptian aquaculture striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypothalamus), such as a rise of E. tarda infection in the polyculture of Nile tilapia and striped catfish. Caged Nile tilapia, which fed untreated marine fish offal, were infected with Vibrio parahaemolyticus, which usually prevailed in marine fish species [16]. Previous studies stated that the introduction of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) resulted in the occurrence of Lernaea cyprinacea infestation in freshwater fish in Egyptian farms and hatcheries [17, 18].

To combat Edwardsiellosis, veterinarians and fish farmers use different antibiotics with different doses and schedules; the abuse of antibiotics applications is a usual practice in low- and middle-income countries, resulting in antibiotic resistance requesting alternative antimicrobial agents [19–23]. Many Edwardsilla spp., which were recovered from various fish species, have developed high levels of resistance against a wide range of antibiotics [24], with a potential spread becoming a major concern for human health. Antibiotic withdrawal period mainly controlled by water temperature [25]. In this study, Nile tilapia and striped catfish were subjected to two different temperature degrees (25 °C and 33 °C), and antibiotic residues were determined after a challenge test and treatment with ciprofloxacin.

This work aims to isolate Edwardsiella tarda from Nile tilapia and striped catfish reared in polyculture and monoculture fish farms. Also, retrieved bacteria were identified and confirmed using molecular techniques. An experiment was conducted to investigate the impact of temperatures of rearing water on E. tarda infection rate and re-isolation rate as well as response to ciprofloxacin treatment and its residue in the liver tissues of Nile tilapia and striped catfish.

Materials & methods

Fish farms and samples collection

During the production season (April to November 2024), moribund Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypothalamus) were randomly collected from three fish farms encountered mortalities (10–50 deaths per day); the fish pond is earthen-pond about three acres in area and 1 m in depth. Farms 1–3 are designed as follows: Farm 1 has a monoculture with 25,000 Nile tilapia per acre, Farm 2 is a monoculture with 30,000 striped catfish per acre, and Farm 3 is a polyculture with 25,000 Nile tilapia and 10,000 striped catfish per acre. Fish farms are located at village Tolmpat 7 in north Egypt.

Fish samples were collected from Farm 1, Farm 2, and Farm 3. Each farm provided 60 Nile tilapia and 60 striped catfish. The collected fish were placed into aerated, clear plastic bags filled with water containing a tranquilizing agent, tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222, Syndel, Canada), at a concentration of 40 mg/L [26, 27]. The fish were immediately transported to the Animal Health Research Institute laboratory for further analysis.

Water samples analyses

At farm sites, water temperature and salinity were determined (YSI Environmental, EC300), dissolved oxygen (DO) (Aqualytic, OX24), and pH (Thermo Orion, 420 A). Three water samples, one from each pond, were parallelly collected with fish samples from each farm at a depth of 0.5 m of the fish pond using aseptic one-liter plastic bottles to avoid bacterial contamination. Then, the bottles were transported into the ice box and sent to the laboratory. At the laboratory, Animal Health Research Institute, water samples were examined for total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), unionized ammonia (NH3), nitrite (NO2), and nitrate (NO3) using UV/visible spectrophotometer, Thermo-Spectronic 300.

Microbiological examination of the bacterial isolates

The examination of fish samples was done to determine the occurrence of bacterial infections in farmed fish samples, following the recommendations of Woo and Bruno [28].

The preliminary isolation

Fish organs, brain, kidney, spleen, and liver were swabbed into tryptic soy broth (Difco, Detroit, USA) for 24 h at 30 °C. A loopful from each bacterial strain was re-cultured onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco, Detroit, USA) supplemented with 5% sheep blood for 24 h at 30 °C. The most prevailed bacterial colonies (similar size and shape) on TSA were harvested and re-cultivated onto selective media (Salmonella-Shigella agar) (Difco, Detroit, USA) phenotypic profiles of E. tarda were according to the instruction of Bergey [29]. Then, they were preserved in tryptic soy broth with an equal amount of glycerol solution (30%) at −80 °C. Further identification was performed with Gram-stain and API 20E (bio-Merieux) [30, 31].

Molecular identification

DNA of Edwardsiella spp were extracted and examined for gyrB1 gene and virulence genes: cds1 (chondroitinase), qseC sensor protein, and pvsA (vibrioferrin synthesis). The DNA extraction was done with the PathoGene-spin™ DNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). Then, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kits (Bioline, Meridian Life Science, UK) were used to replicate target sequences. The PCR products were run into agarose gel 1% to separate distinct bands using electrophoresis (Applichem, Germany, GmbH), and the bands were photographed using a gel documentation system (Alpha Innotech, Biometra). All primers and gene amplification used in this study are listed in (supplementary).

Sequence of bacterial DNA

Amount of 50 ng/µl the bacterial DNA was preserved (−20 ℃) for E. tarda gyrB1 sequencing, the amplicons (bands) were cut off the gel and purified (QIAquick extraction kits, Qiagen, Germany), the target gene was sequenced (Big Dye terminator v3.1 kit, Life Technologies, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the ABI 3730xl DNA-sequencer (Applied Biosystems™, USA). The raw sequences were manually edited (sequence alignment editor, BioEdit v. 7.2.5) [32] before being submitted to the GenBank database to access the accession numbers. The Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree was developed to display the results using the MEGA X program [33].

Antimicrobial sensitivity analyses

The method of disc diffusion was performed in triplicates to detect the sensitivity and resistance of the four E. tarda isolates to different antibiotics that are used in aquaculture, such as tetracycline (TE) 30 µg, ciprofloxacin (CIP) 5 µg, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT) 1.25/23.75 µg, erythromycin (E) 15 µg, florfenicol (F) 30 µg, gentamicin (GEN) 30 µg, amoxicillin 10 µg, kanamycin (K) 30 µg, cefotaxime (CTX) 30 µg, ampicillin (AMP) 10 µg, and streptomycin (S) 30 µg, All antibiotic discs obtained from Oxoid™. Isolates were enriched into TSB for 12 h, then cultured onto Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid™), and antimicrobial discs were organized on the plates. Disc antibiotic concentrations, the diameter of the inhibition zones was determined, and the results were interpreted according to the standards of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2010) as resistant, intermediate, and sensitive [34]. The multidrug resistance (MDR) of E. tarda strains was calculated using the following equation:

|

Where x is the number of antibiotics in which the isolates were resisted, and y is the tested antibiotics, MDR greater than 0.2 means that the strain is multi-resistant [35].

Lethal median dose and pathogenicity testing

The LD50 of the E. tarda strains was calculated using steps provided by Reed and Muench [36]. Four hundred Nile tilapia and four hundred striped catfish with a mean weight of (70.8 ± 0.3 g and 92 ± 1.1 g, respectively) were purchased from a private fish hatchery hatchery in Kafrelsheikh governorate tranquilized with MS-222 at a concentration of 40 mg/L of transporting water. Each E. tarda isolates serial tenfold dilutions (24 h-old culture); 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, and 1010 CFU/mL. The bacterial counts were adjusted using McFarland standard and re-cultivated on TSA to ensure the accuracy of the count. A 100 µl suspension of each dilution was injected intraperitoneally into ten Nile tilapia and ten striped catfish. Mortalities were observed for fourteen successive days post-challenge.

Experimental infection, antibiotic treatment, and antibiotic residues

One hundred and forty healthy Nile tilapia and one hundred and forty striped catfish with a mean weight of (70.8 ± 0.3 g and 92 ± 1.1 g, respectively) were purchased from a private fish hatchery and transported to the wet laboratory at Animal Health Research Institute, Kafrelsheikh. Fishes were subdivided equally into two groups (120 individuals for each fish species) and acclimated in 24 glass aquaria 40 × 40 × 50 cm (10 fish/aquarium) at two different water temperatures, 25℃ and 33℃. Twenty Nile tilapia and twenty striped catfish were kept as controls.

To examine the pathogenicity of E. tarda, 30 fish (Nile tilapia and striped catfish) were intraperitoneally injected with 0.1 mL of E. tarda solution containing LD50 of LAMSH1 and LAMAH2-4 strains obtained from this study, the bacteria dose was adjusted to LD50 using the McFarland scale in phosphate buffer saline and re-cultivated in TSA for the accuracy of the bacterial number. Also, a negative control group was formed by injecting ten fish with pure normal saline (0.65 mg/L), according to Boijink et al. [25]. Each dead fish was counted for 14 days if E. tarda was re-isolated and confirmed using PCR following the scheme in the above Sect. (2.3.2.). The mortality rates (MR) were estimated using the following equation:

|

Antibiotic treatment and residues: Fish were treated with ciprofloxacin (Cip) the trade name is ciprofar (500 mg) manufactured by Pharco pharmaceuticals (Batch No.: 21515/2012), Amirya-Alexandria, Egypt.

Commercial feed (pellets) was soaked in water and then blended with 5% (w/w) gelatin (Nutri-B-Gel, produced by Canal Aqua Cure, Port-Said, Egypt) and mixed into a paste. The Cip was added at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w./day [37], past was allowed to dry, then cut into 2 mm-thick pellets. Fish feeds were offered once a day for 10 successive days at a rate of 1% of fish b.w.

Water parameters: temperature was 25℃ and 33℃ in the two groups aquaria, while values of water salinity, DO, and pH were remained at 0.5 g/L, 5.45 mg/L, and 7.3, respectively, during the experimental period. Ammonia compounds remained below 0.2 mg/L by replacing one third of aquaria water with clean dechlorinated tap water (with the same water temperature).

The residues of Cip were detected in the hepatic tissues using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Briefly, tissues were thawed and homogenized (IKA-WERKE ULTRA-TURRAX), adding 25 ml of acetonitrile. Samples were centrifuged (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810 R) at 6000×g for 10 min. The extraction liquid was separated into a flask at 40 °C until it was almost dried using N2 gas, then filtrated into a disposable syringe (0.45 μm filter) and directly injected into the HPLC [38].

Statistical analyses

The impacts of E. tarda on Nile tilapia and striped catfish survivability, bacterial re-isolation, and antibiotic residues were statistically determined by comparing the means of the obtained data using one-way ANOVA test, SPSS software version 22. P-values of the collected data determined using Duncan’s various range, if P≤ 0.05 they were statistically significant. Results showed as mean±standard error (SE).

Results

In Table 1, the infection rate E. tarda infection rate in Farm 3 (polyculture: Nile tilapia and striped catfish) was 35/60 and 60/60, respectively, while it was 5/60 and 20/60 in monoculture farms Nile tilapia (Farm 1) and striped catfish (Farm 2), respectively, regardless of bacterial strain. The strain LAMSH1 was only isolated from striped catfish (Farm 3); meanwhile, LAMAH3 was only isolated from fish on Farm 3, moribund Nile tilapia 35/60 and striped catfish 40/60, while LAMAH4 and LAMAH2 were isolated from both Farm 1 and Farm 2. From the obtained LD50, striped catfish were more vulnerable to infection as lower LD50 values caused high mortality compared to Nile tilapia. Also, co-infection occurred in striped catfish in polyculture Farm 3.

Table 1.

Number of naturally infected fish, virulence genes, and median lethal doses of E. tarda strains

| Items | Fish no. | LAMSH1 | LAMAH2 | LAMAH3 | LAMAH4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gyrB1 | gyrB1, cds1, pvsA | gyrB1, cds1, qseC | gyrB1, qseC | ||

| Farm 1 Nile tilapia | 60 | - | - | - | 5 |

| Farm 2 Striped catfish | 60 | - | 20 | - | - |

| Farm 3 polyculture | 60 + 60 | 60 | - | 35*&40** | - |

| LD50 (CFU/mL) Nile tilapia | 3.37 × 105 | 3.1 × 105 | 2.95 × 105 | 3.09 × 105 | |

| LD50 (CFU/mL) Striped cat fish | 0.7 × 105 | 2.82 × 104 | 1.78 × 104 | 3.81 × 104 | |

Farm polyculture, fish population formed of Nile tilapia and striped catfish. LD50, median lethal dose. cds1, chondroitinase, pvsA; vibrioferrin synthesis, and qseC, sensor protein

*Nile tilapia

**striped catfish

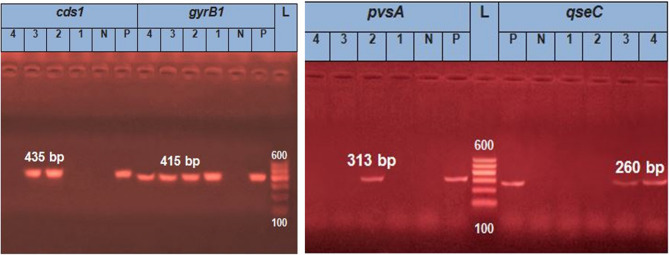

In Fig. 1; Table 1, different patterns of gyrB1 and virulence genes cds1, pvsA, and qseC were detected in the four isolates. The strain LAMSH1 did not harbor the three virulent genes under investigation, and co-infected striped catfish with LAMAH3 harbored cds1 and qseC. Meanwhile, LAMAH3 was the only isolated strain from Nile tilapia (monoculture) and contained qseC, cds1, while pvsA was recorded only in LAMAH2, which was isolated from striped catfish (monoculture).

Fig. 1.

DNA bands on electrophoresis gel of Edwardsiella tarda gyrB1 and virulence genes: cds1; chondroitinase, pvsA; vibrioferrin synthesis, and qseC; sensor protein. P, positive, N; negative, L; ladder, E. tarda strains 1; LAMSH1, 2; LAMAH2, 3; LAMAH3, 4; LAMAH4

Four E. tarda strains LAMSH1 and LAMAH2-4, were sequenced for gyrB1 and submitted in the NCBI under accessions numbers PQ839250, PQ839251, PQ867513, and PQ867512, respectively. In Fig. 2, the phylogenetic tree revealed that LAMAH2 and LAMAH3 were genetically related, whereas LAMSH1 and LAMAH4 were also near and harbor low virulence genes with low LD50 values.

Fig. 2.

Sequences of gyrB1 gene of the four E. tarda isolates

In Table 2, the four isolates of E. tarda were examined for antibiotic sensitivity. All strains were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and florfenicol. Also, it was noticed that strains were resistant to high numbers of antibiotics, and the MDR indices of LAMSH1, LAMAH2, and LAMAH3 were greater than 0.2 and were 0.55, 0.27, and 0.55, respectively, whereas LAMAH4 was 0.18 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Antibiogram of the isolated Edwardsiella tarda strains

| No. | Bacteria Strain (N = 4) | S (%) | IM (%) | R (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tetracycline (TE) 30 µg | - | - |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2-4 |

| 2 |

Trimethoprim (SXT) 1.25 µg Sulfamethoxazole 23.75 µg |

- | - |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2-4 |

| 3 | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) 5 µg |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2-4 |

- | - |

| 4 | Florfenicol (F) 30 µg |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2-4 |

- | - |

| 5 | Erythromycin (E) 15 µg | LAMAH 2,4 |

LAMSH1 LAMAH3 |

- |

| 6 | Gentamycin (GEN) 30 µg | - | LAMAH2,4 |

LAMSH1 LAMAH3 |

| 7 | Amoxicillin (AML) 30 µg | - |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2-4 |

- |

| 8 | Ampicillin (AMP) 10 µg | - |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2-4 |

- |

| 9 | Kanamycin (K) 30 µg | - | LAMAH2,4 |

LAMSH1 LAMAH3 |

| 10 | Cefotaxime (CTX) 30 µg | - | LAMAH2,4 |

LAMSH1 LAMAH3 |

| 11 | Streptomycin (S) 30 µg | - | LAMAH4 |

LAMSH1 LAMAH2,3 |

S Sensitive, IM Intermediate, R Resistant

Table 3.

Data on multidrug resistant index of E. tarda strains

| No. | Bacteria Strain | Antibiotics resistant | MDR index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LAMSH1 | TE, SXT, S, GEN, K, CTX | 0.55 |

| 2 | LAMAH2 | TE, SXT, S | 0.27 |

| 3 | LAMAH3 | TE, SXT, S, GEN, K, CTX | 0.55 |

| 4 | LAMAH4 | TE, SXT | 0.18 |

MDR Multidrug resistant genes, TE Tetracycline, CIP Ciprofloxacin, SXT trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, S Streptomycin, GEN Gentamycin, K Kanamycin and, CTX Cefotaxime

From Table 4, it was clear that there were no statistical differences in water physical parameters temperature, pH, and DO between farms under investigation. The water of fish farms was brackish, where salinity was significantly lower in Farm 2 (1,27 g/L) compared to the water of Farm 2 (1,97 g/L) and Farm 3 (1,93 g/L); however, these values were.

Table 4.

Water analyses of the investigated fish farms

| Items | Temp ℃ | pH | DO mg/L | Salinity g/L | TAN mg/L | NH3 mg/L | NO2mg/L | NO3 mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Farm 1 Monoculture Nile tilapia |

25.73 ± 0.23 |

8.03 ± 0.12 |

4.7 ± 0.15 |

1.27B ± 0.07 |

0.52C ± 0.01 |

0.034B ± 0.008 |

0.04B ± 0.01 |

0.43B ± 0.2 |

|

Farm 2 monoculture striped catfish |

25.57 ± 0.23 |

8.24 ± 0.14 |

4.89 ± 0.35 |

1.97A ± 0.07 |

2.75A ± 0.12 |

0.29A ± 0.09 |

0.24A ± 0.01 |

2.01A ± 0.38 |

|

Farm 3 Polyculture |

25.87 ± 0.2 |

8.4 ± 0.09 |

4.68 ± 0.52 |

1.93A ± 0.08 |

1.65B ± 0.1 |

0.183AB ± 0.05 |

0.05B ± 0.02 |

0.52B ± 0.2 |

Different letter in the same column indicates significant difference at P ≤ 0.05

Temp water temperature, pH Hydrogen ion, DO Dissolved oxygen, TAN Total ammonia, NH3 unionized ammonia, NO2 Nitrite, and NO3 nitrate

Water chemical analyses revealed that ammonia compounds TAN, NH3, NO2, and NO3 in Farm 2 (monoculture, striped catfish) were significantly higher at 2.75, 0.29, 0.24, and 2.01 mg/L, respectively, compared with Farm 1 (monoculture, Nile tilapia) and polyculture Farm 3.

Nile tilapia (Table 5) and striped catfish (Table 6) were challenged with four E. tarda isolates in two different water temperatures, 25 °C and 33 °C, with the obtained LD50. Then, fish were treated with sensitive antibiotic ciprofloxacin and re-isolation of E. tarda attempts and antibiotic residues were performed.

Table 5.

Experimental nile tilapia challenged against isolated E. Tarda. (n = 30)

| Water temperature | 27 °C | 25 °C | 33 °C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nile tilapia | LD50 | MR (%) | RI (%) | AR (µg) | MR (%) | RI (%) | AR (µg) | ||||

| UT | T | UT | T | UT | T | UT | T | ||||

| Control | Saline 0.65% | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LAMSH1 | 3.37 × 105 | 30 | 10 | 60 | 20 | 7.04 | 40 | 20 | 80 | 30 | 6.6 |

| LAMAH2 | 3.1 × 105 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 30 | 7.3 | 60 | 30 | 70 | 50 | 6.73 |

| LAMAH3 | 2.95 × 105 | 50 | 20 | 70 | 30 | 7.15 | 60 | 40 | 80 | 50 | 6.55 |

| LAMAH4 | 3.09 × 105 | 30 | 20 | 60 | 30 | 7.24 | 40 | 30 | 70 | 40 | 6.4 |

LD50 median lethal dose, MR Mortality rate, RI Re-isolation, AR Antibiotic residues, UT Untreated, T Treated with antibiotic

Table 6.

Experimental striped catfish challenged against isolated E. tarda. (n = 10)

| Water temperature | 27 °C | 25 °C | 33 °C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Striped catfish | LD50 | MR (%) | RI (%) | AR (µg) | MR (%) | RI (%) | AR (µg) | ||||

| UT | T | UT | T | UT | T | UT | T | ||||

| Control | Saline 0.65% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| LAMSH1 | 0.7 × 105 | 50 | 40 | 80 | 70 | 6.3 | 50 | 40 | 80 | 60 | 5.08 |

| LAMAH2 | 2.82 × 104 | 70 | 50 | 90 | 90 | 6.16 | 80 | 60 | 100 | 90 | 5.1 |

| LAMAH3 | 1.78 × 104 | 70 | 50 | 100 | 80 | 6.09 | 80 | 60 | 100 | 90 | 5.2 |

| LAMAH4 | 3.81 × 104 | 60 | 40 | 90 | 70 | 6.2 | 80 | 60 | 100 | 80 | 5.32 |

LD50 median lethal dose, MR Mortality rate, RI Re-isolation, AR Antibiotic residues, UT Untreated, T Treated with antibiotic

At a high temperature (33 °C) water, Nile tilapia showed a higher MR% and RI%, about 10–20%, over those at a low water temperature (25 °C) concurrently with low antibiotic residues in their hepatic tissues. Striped catfish showed similar findings as Nile tilapia except for the strain LAMSH1 differences of water temperature did not affect the MR; however, the re-isolation rate was increased by 10% over lower temperatures (25 °C). Regardless of fish spp, antibiotic residues were decreased in the hepatic tissues of those exposed to a high temperature of 33 °C; Nile tilapia showed higher ciprofloxacin residues than striped catfish regardless of water temperature.

Discussion

In this work, four E. tarda were isolated and identified in three monoculture and polyculture fish farms, experienced mortalities of about 10–50 deaths daily with a high isolation rate Nile tilapia (35/60) and striped catfish (60/60). Edwardseilla spp. occurred in a wide range of aquatic animals, mainly those exposed to high water temperatures and an overload of organic matter [39]. In addition, susceptible fish may infected with E. tarda via gills, skin, or oral route [40]; for example, striped catfish experienced Edwardsiellosis among several diseases’ challenges and infections outbreaks as many freshwater fishes [41, 42], the Edwardsiellosis/emphysematous putrefactive disease is a septicaemic recorded in some fish farms associated with mass mortality in various populations and ages of striped catfish; the disease is usually observed in tilapia, carp, eel, catfish, mullet, and flounder [41, 43].

Different phenotypic variations and interspecific diversity between E. tarda isolates were retrieved from different fish species, so disease control and epidemiological investigations need rapid and validated detection of the isolates [12, 44]. In this study, the identification of E. tarda isolates was confirmed by the presence of gyrB1 and virulence genes cds1, pvsA, and qseC; also, the isolates harbored different virulence gene patterns. Previous studies stated that E. tarda possesses several virulence-related and toxin secretion system-related genes such as gyrB1, edwI, cds1, qseC, and pvsA through which bacterium could survive within macrophages and detoxifying organs (liver and the kidney) as well as it could infect a wide range of aquatic animals [45]. In this work, the obtained LD50 indicated that striped catfish were more vulnerable to E. tarda infection, possessing low LD50 values. Interestingly, healthy striped catfish were intramuscularly injected with a sub-lethal dose of 1.77 × 107 cells E. tarda/fish showed Edwardsiellosis signs while MR% reached 42% at 48 h post-injection [46].

In this work, the isolated E. tarda were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and florfenicol but were resistant to many antibiotics. Also, MDR was higher than 0.2, indicating a multi-drug-resistant bacteria. Accordingly, in polyculture systems, Zhang et al. [47] found that antibiotic-resistance bacteria (ARB) prevailed in the fish gut, mucosal skin, and gill filaments in farms of hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus♂), Gracilaria bailinae, and Litopenaeus vannamei with different stocking combinations, researchers suggested that differences in antibiotic resistance were derived by polyculture system cause changes in bacterial communities. Conversely, findings were claimed by Huang et al. [48], who claimed that ARB is more prevalent in fish reared in monoculture farms than those in integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA) systems. In contrast to our findings, Yuan et al. [49] stated that ARB was more isolated from bullfrog ponds than polyculture ponds due to the more frequent use of antimicrobial treatments with seven categories of commonly used antibiotics (e.g., aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, sulfonamides, tetracyclines). Besides aquaculture systems, other factors control the abundance of ARG; the hospital sewage water in a polluted duckweed farm and ARG had the same resistance pattern determined of wastewater as high strains numbers of antibiotic resistance Aeromonas were recovered [50].

In this work, water examination revealed high TAN, NH3, NO2, and NO3 levels, mainly in Farm 2 (monoculture, striped catfish), suggesting a role in bacterial distribution and prevalence. Similar results with different fish species, Zheng et al. [51] experimented on different farm system models; four different fish: black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus), largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco), and pearl mussel (Hyriopsis cumingii) each in a separate pond, every pond was stocked with three of Chinese carps (silver, bighead, and gibel) in fish polyculture or mussel, it was noticed that the bacterial diversity and distribution using 16 S rDNA in the ponds was statistically correlated with ammonia compounds, claiming that aquaculture mode is a factor regulating the microbial community at the genus level. Similar to the results of high ammonia compounds in monoculture striped catfish, largemouth bass and yellow catfish pond had higher water ammonia, nitrite, TN, and TP levels than the pearl mussel pond [52, 53]. In this context, the water exchange rate and accumulation of organic matter could play a role in the prevalence of virulent bacteria that facilitate the formation of a bacterial biofilm as one form of organic soiling on the surface, which could protect bacteria from disinfectants [54–56].

In the indoor experiment, Nile tilapia and striped catfish maintained at a high water temperature of 33 °C showed high MR% and RI%. Accordingly, in the summer season, climate change correlated with alterations in bacterial communities in water, whereas the feed habitat of fish changes, resulting in increasing the abundance of potential pathogens (e.g., the genera Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Shewanella) in fish guts and increase nitrogen wastes in the pond which cause stressful environment to crucian carp [57, 58]. The low ciprofloxacin residues in the hepatic tissues of Nile tilapia and striped catfish, which reared at the high-water temperature of 33 °C in contrast with low water temperature (25 °C), could be explained by the fact that the clearance of antibiotics from fish tissues depends on water temperature and fish metabolism as high temperature accelerates metabolic processes in poikilothermic animals [59]. Accordingly, Salte and Liestol [60] noticed that sulfonamides elimination from muscular tissues of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) was controlled by water temperature and salt concentrations, suggesting a withdrawal time of 60 days and 100 days at water temperature over 10 °C and 7–10 °C, respectively, while low clearance of antibiotic in low water temperature could be due to the downregulation of metabolic rate. From the results obtained, consumers who received the ciprofloxacin-treated Nile tilapia or striped catfish were subjected to considerable amounts of antibiotics. Ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin could resist biodegradation [61], and even wastewater treatment cannot eliminate it [62]. Moreover, ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin can accumulate in aquatic animals and were identified in several fish kinds [63]. Similarly, in a previous study, ciprofloxacin in water was 70 ng/L accumulated in the fish at a concentration of 7.5 × 10−6 µg/g, whereas humans consumed 113 g of fish containing this level, the contents of the human intestinal had a concentration of 2 × 10−6 µg/mL suggesting that ciprofloxacin residues are unlikely to be problematic, however resulted in intestinal dysbiosis and antibiotic resistance [64].

In this experiment, the causative agent of fish deaths was confirmed based on the RI of the E. tarda isolates rather than recording the clinical and post-mortem signs. Previous studies confirmed that hemorrhagic bacterial diseases have similar clinical and post-mortem signs in addition to Edwardsiella spp. share many phenotypic characters [12, 13, 15].

Future studies could spotlight the effect of polluted water (heavy metals and pesticides) on bacterial DNA mutation, decreased antibiotic efficacy, and the impacts of polyculture on fish immunity that made fish more vulnerable to bacterial infection.

Conclusion

Polyculture striped catfish and Nile tilapia were associated with a high rate of E. tarda isolation. Striped catfish were more susceptible to Edwadsiellosis with low LD50 values. The monoculture striped catfish was associated with the high ammonia compound in the water. All isolated strains were sensitive to florfenicol and ciprofloxacin with different patterns of virulence-related genes. From the experimental trial, a highwater temperature of 33 °C increases the infection and re-isolation rates with low ciprofloxacin residues in the hepatic tissue regardless of fish kind.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Authors’ contributions

All authors equally contributed to this work. All authors analysed and interpreted the data regarding gene expression and enzymes. All authors performed the experimental study and were major contributors to writing the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The above described methodology was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Animal Health Research Institute and European Union directive 2010/63UE, and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). This paper does not contain any studies with human participants by any of the authors. No specific permissions were required for access to the artificial pond in wet laboratory Animal Health Research Institute, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt. The field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lamiaa A. Okasha, Email: lamiaa.okasha3525@gmail.com

Ahmed H. Sherif, Email: ahsherif77@yahoo.com

References

- 1.FAO, food and drug organization. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020, sustainability in action. 2020.

- 2.FAO, food and drug organization. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation, FAO. 2022. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9df19f53-b931-4d04-acd3-58a71c6b1a5b/content/cc0461en.html.

- 3.Rossignoli CM, Manyise T, Shikuku KM, Nasr-Allah AM, Dompreh EB, Henriksson PJG, et al. Tilapia aquaculture systems in egypt: characteristics, sustainability outcomes and entry points for sustainable aquatic food systems. Aquaculture. 2023;577:739952. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaaban NA, Tawfik S, El-Tarras W, El-Sayed Ali T. Potential health risk assessment of some bioaccumulated metals in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultured in Kafr El-Shaikh farms. Egypt Environ Res. 2021;200:111358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai XJ, Ji WX, Han H, Dai YX, Wang Y. Growth, feed utilization, body composition and swimming performance of giant croaker, Nibea japonica Temminck and Schlegel, fed at different dietary protein and lipid levels. Aquac Nutr. 2013;19:928–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos L, Ramos F. Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: current knowledge and alternatives to tackle the problem. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enany M, Al-Gammal A, Hanora A, Shagar G, El Shaffy N. Sidr honey inhibitory effect on virulence genes of MRSA strains from animal and human origin. Suez Canal Veterinary Med J SCVMJ. 2015;20(2):23–30. 10.21608/scvmj.2015.64562. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SB, Aoki T, Jung TS. Pathogenesis of and strategies for preventing Edwardsiella tarda infection in fish. Vet Res. 2012;43(1):67. 10.1186/1297-9716-43-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abayneh T, Colquhoun DJ, Sørum H. Edwardsiella piscicida sp. nov., a novel species pathogenic to fish. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;114(3):644–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie HX, Lu JF, Zhou Y, Yi J, Yu XJ, Leung KY, Nie P. Identification and functional characterization of the novel Edwardsiella tarda effector Ese. J Infect Immun. 2015;83(4):1650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang W, Wang L, Zhang L, Qu J, Wang Q, Zhang Y. An invasive and low virulent Edwardsiella tarda esrB mutant promising as live attenuated vaccine in aquaculture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:1765–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinsley JW, Lyndon AR, Austin B. Antigenic and cross-protection studies of biotype 1 and biotype 2 isolates of Yersinia ruckeri in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum). J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111(1):8–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abraham TJ, Ritu R. Effects of dietary supplementation of Garlic extract on the resistance of Clarias gariepinus against Edwardsiella tarda infection. Iran J Fish Sci. 2015;14:719–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adikesavalu H, Paul P, Priyadarsani L, Banerjee S, Joardar SN, Abraham TJ. Edwardsiella tarda induces dynamic changes in immune effector activities and endocrine network of Pangasius pangasius (Hamilton, 1822). Aquaculture. 2016;462:24–9. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.04.033. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soto E, Griffin M, Arauz M, Riofrio A, Martinez A, Cabrejos ME. Edwardsiella ictaluri as the causative agent of mortality in cultured nile tilapia. J Aquat Anim Health. 2012;24(2):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherif AH, AbuLeila RH. Prevalence of some pathogenic bacteria in caged- nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) and their possible treatment. Jord J Biol Sci. 2022;15(2):239–47. 10.54319/jjbs/150211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fatma MM. Lernaeosis affecting hatchery reared common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Fries and a novel approach for its treatment. G J Fish Aquac Res. 2014;1(2):173–89. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Attia MM, Hanna MI, Ramadan RM. Evaluation of the immunological status of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio) infested with Lernaea cyprinacea. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish. 2022;26(4):1305–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bello-L´ opez JM, Cabrero-Martínez OA, Ib´a˜ nez-Cervantes G, Hern´andez-Cortez C, Pelcastre-Rodríguez LI, Gonzalez-Avila LU, Castro-Escarpulli G. Horizontal gene transfer and its association with antibiotic resistance in the genus Aeromonas spp. Microorganisms. 2019;7:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Yang QE, Zhou X, Wang FH, Muurinen J, Virta MP, et al. Antibiotic resistome in the livestock and aquaculture industries: status and solutions. Crit Rev En Viron Sci Technol. 2020;51:2159–96. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherif AH, Elshenawy AM, Attia AA, Salama SAA. Effect of aflatoxin B1 on farmed Cyprinus carpio in conjunction with bacterial infection. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish. 2021;25(2):465–85. 10.21608/EJABF.2021.164686. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherif AH, Khalil RH, Tanekhy M, Sabry NM, Harfoush MA, Elnagar MA. Lactobacillus plantarum ameliorates the immunological impacts of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (rutile) in Oreochromis niloticus. Aquac Res. 2022;53:3736–47. 10.1111/are.15877. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherif AH, Khalil RH, Talaat TS, Baromh MZ, Elnagar MA. Dietary nanocomposite of vitamin C and vitamin E enhanced the performance of nile tilapia. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15648. 10.1038/s41598-024-65507-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okasha LA, Abdellatif JI, Abd-Elmegeed OH, Sherif AH. Overview on the role of dietary Spirulina platensis on immune responses against edwardsiellosis among Oreochromis niloticus fish farms. BMC Vet Res. 2024;20(1):290. 10.1186/s12917-024-04131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boijink CDL, Brandão DA, Vargas ACD, Costa MMD, Renosto AV. Inoculação de Suspensão Bacteriana de Plesiomonas shigelloides Em jundiá, Rhamdia quelen (teleostei: pimelodidae). Ciênc Rural. 2001;31:497–501. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eldessouki EA, Salama SSA, Mohamed R, Sherif AH. Using nutraceutical to alleviate transportation stress in the Nile tilapia. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish. 2023;27(1):413–29. 10.21608/ejabf.2023.287741. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherif AH, Eldessouki EA, Sabry NM, Ali NG. The protective role of iodine and MS-222 against stress response and bacterial infections during nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) transportation. Aquac Int. 2023;401–16. 10.1007/s10499-022-00984-7.

- 28.Woo P, Bruno D. Diseases and disorders of finfish in cage culture. 2nd ed. Oxon: CABI Pub; 2014. pp. 159–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holt JG, Krieg NR, Sneath PHA, Staley JT, Williams ST. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology, Aeromonas. 9th ed. Wiley; 1994;150.

- 30.Buján N, Mohammed H, Balboa S, Romalde JL, Toranzo AE, Arias CR, Magariños B. Genetic studies to re-affiliate Edwardsiella tarda fish isolates to Edwardsiella piscicida and Edwardsiella anguillarum species. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2018;41(1):30–7. 10.1016/j.syapm.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buller NB. Bacteria from fish and other aquatic animals: a practical identification manual. Cambridge: CABI Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/N.T. Nuclic acids. Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, Pa, USA: Twentieth Informational Supplement M100-S20, CLSI; 2010.

- 35.Krumperman PH. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46(1):165–70. 10.1128/aem.46.1.165-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reed LJ, Muench H. Simple method of estimating 50% endpoint. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noga EJ. Fish Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 2nd Ed. Wiley-Blackwell. 2010;17:347–420.

- 38.Xu W, Zhu X, Wang X, Deng L, Zhang G. Residues of enrofloxacin, furazolidone and their metabolites in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture. 2006;254(1–4):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miniero Davies Y, Oliveira MG, Cunha M, Franco L, Santos SL,Moreno L, Saidenberg A. Edwardsiella tarda outbreak affecting fishes and aquatic birds in Brazil. Vet. Q. 2018: 38(1): 99–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling SHM, Wang XH, Lim TM, Leung KY. Green fluorescent protein -tagged Edwardsiella tarda reveals portal of entry in fish. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001; 194(2): 239–243. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb09476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh AK, Lakra WS. Culture of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus into india: impacts and present scenario. Pak J Biol Sci. 2012;15(1):19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shetty M, Maiti B, Venugopal MN, Karunasagar I. First isolation and characterization of Edwardsiella tarda from diseased striped catfish, Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage). J Fish Dis. 2014;37(3):265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohanty BR, Sahoo PK. Edwardsiellosis in fish: a brief review. J Bio Sci. 2007;32(3):1331–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Austin B, Austin DA. Miscellaneous pathogens. InBacterial Fish Pathogens. Springer Netherlands; 2012. pp. 413–441. 10.1007/978-94-007-4884-212.

- 45.Verjan CR, Augusto V, Xie X, Buthion V. Economic comparison between hospital at home and traditional hospitalization using a simulation-based approach. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2013;26(1/2):135–53. 10.1108/17410391311289596. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoque F, Pawar N, Pitale P, Dutta R, Sawant B, Chaudhari A, Sundaray JK. Pathogenesis and expression profile of selected immune genes to experimental Edwardsiella tarda infection in iridescent shark Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Aquac Rep. 2020;17:100371. 10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100371. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang M, Hou L, Zhu Y, Zhang C, Li W, Lai X, Yang J, Li S, Shu H. Composition and distribution of bacterial communities and antibiotic resistance genes in fish of four mariculture systems. Environmen Pollut. 2022;311:119934. 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang L, Xu YB, Xu JX, Ling JY, Chen JL, Zhou JL, Zheng L, Du QP. Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in Duck and fish production ponds with integrated or non-integrated mode. Chemosphere. 2017;168:1107–14. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan K, Wang X, Chen X, Zhao Z, Fang L, Chen B, Jiang J, Luan T, Chen B. Occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes in extracellular and intracellular DNA from sediments collected from two types of aquaculture farms. Chemosphere. 2019;234:520–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahman M, Huys G, Kühn I, Rahman M, Möllby R. Prevalence and transmission of antimicrobial resistance among Aeromonas populations from a duckweed aquaculture based hospital sewage water recycling system in bangladesh. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. Int J Gen Mol Microbiol. 2009;96:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng X, Tang J, Zhang C, Qin J, Wang Y. Bacterial composition, abundance and diversity in fish polyculture and mussel–fish integrated cultured ponds in China. Aquac Res. 2017;48:3950–61. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Wang WL, Qin JG, Wang XD, Zhu SB. Effects of integrated combination and quicklime supplementation on growth and Pearl yield of freshwater Pearl mussel, Hyriopsis cumingii (Lea, 1852). Aquac Res. 2009;40:1634–41. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang JY, Dai YX, Wang Y, Qin JG, Li YM. Improvement of fish and Pearl yields and nutrient utilization efficiency through fish-mussel integration and feed supplementation. Aquaculture. 2015;448:321–6. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohsumi T, Takenaka S, Wakamatsu R, Sakaue Y, Narisawa N, Senpuku H, Okiji T. Residual structure of Streptococcus mutans biofilm following complete disinfection favors secondary bacterial adhesion and biofilm re-development. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116647. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karkman A, Pärnänen K, Larsson DGJ. Fecal pollution can explain antibiotic resistance gene abundances in anthropogenically impacted environments. Nat Commun. 2019;10:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thongsamer T, Neamchan R, Blackburn A, Acharya K, Sutheeworapong S, Tirachulee B, et al. Environmental antimicrobial resistance is associated with faecal pollution in central thailand’s coastal aquaculture region. J Hazard Mater. 2021;416:125718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Infante-Villamil S, Huerlimann R, Jerry DR. Microbiome diversity and dysbiosis in aquaculture. Rev Aquac. 2021;13(2):1077–96. 10.1111/RAQ.12513. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li T, Li H, Gatesoupe FJ, She R, Lin Q, Yan X, Li J, Li X. Bacterial signatures of red-operculum disease in the gut of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Microb Ecol. 2017;74(3):510–21. 10.1007/S00248-017-0967-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kosoff RE, Chen CY, Wooster GA, Getchell RG, Clifford A, Craigmill AL, Bowser PR. Sulfadimethoxine and Ormetoprim residues in three species of fish after oral dosing in feed. J Aquat Anim Health. 2007;19(2):109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salte R, Liestol K. Drug withdrawal from farmed fish. Depletion of oxytetracycline, sulfadiazine, and Trimethoprim from muscular tissue of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). Acta Vet Scand. 1983;24:418–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Ahmad A, Daschner FD, Kummerer K. Biodegradability of cefotiam, ciprofloxacin, meropenem, penicillin G, and sulfamethoxazole and Inhibition of waste water bacteria. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1999;37:158–63. 10.1007/s002449900501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong C, Zhuo X, Guo Y. Occurrence and risk assessment of four typicalfluoroquinolone antibiotics in Raw and treated sewage and in receiving waters in Hangzhou. China J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:7303–9. 10.1021/jf2013937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guidi LR, Santos FA, Ribeiro ACSR, Fernandes C, Silva LHM, Gloria MBA. Quinolones and tetracyclines in aquaculture fish by a simple and rapid LC-MS/MS method. Food Chem. 2018;245:1232–8. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kum OK, Chan KM, Morningstar-Kywi N, MacKay JA, Haworth IS. Pharmacokinetic model of human exposure to Ciprofloxacin through consumption of fish. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2024;106:104359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.