Abstract

The distribution of endosymbiotic bacteria in different tissues of queens, males, and workers of the carpenter ant Camponotus floridanus was investigated by light and electron microscopy and by in situ hybridization. A large number of bacteria could be detected in bacteriocytes within the midguts of workers, young virgin queens, and males. Large amounts of bacteria were also found in the oocytes of workers and queens. In contrast, bacteria were not present in oocyte-associated cells or in the spermathecae of mature queens, although occasionally a small number of bacteria could be detected in the testis follicles of males. Interestingly, the number of bacteriocytes in mature queens was strongly reduced and the bacteriocytes contained only very few or no bacteria at all, although the endosymbionts were present in huge amounts in the ovaries of the same animals. During embryogenesis of the deposited egg, the bacteria were concentrated in a ring of endodermal tissue destined to become the midgut in later developmental stages. However, during larval development, bacteria could also be detected in other tissues although to a lesser extent. Only in the last-instar larvae were bacteria found exclusively in the midgut tissue within typical bacteriocytes. Tetracycline and rifampin efficiently cleansed C. floridanus workers of their symbionts and the bacteriocytes of these animals still remained empty several months after treatment had ceased. Despite the lack of their endosymbionts, these adult animals were able to survive without any obvious negative effect under normal cultivation conditions.

The genus Camponotus is classified in the subfamily Formicinae and contains about 1,000 species, which are ubiquitous in many terrestrial habitats (4, 11). In all Camponotus species investigated so far, intracellular bacteria are present within specialized cells of the midgut called bacteriocytes which are intercalated between the typical midgut enterocytes (12, 16, 17, 18). In contrast, in most other bacteriocyte symbioses including that of the close relative Formica fusca, the bacteriocytes form an organ-like structure termed a bacteriome, which is closely associated with the midgut (3, 6). The endosymbiotic bacteria of Camponotus species are gram-negative rods of variable length which apparently float freely in the cytoplasm of the host cells (18). The cytoplasmic location of the bacteria in Camponotus bacteriocytes distinguishes this symbiosis from other bacteriocyte symbioses in which the bacteria exist within membrane-surrounded compartments, the so-called symbiosomes (6, 14).

Phylogenetically, the endosymbionts of different Camponotus species are most closely related to each other, allowing their classification within a single genus which was recently named “Candidatus Blochmannia” (17). The members of this genus are most closely related to other endosymbiotic bacteria of insects such as Buchnera aphidicola of aphids, Wigglesworthia glossinidia of tsetse flies, and, more distantly, Carsonella ruddii of psyllids (2, 7, 8, 17, 20). Buchnera, Wigglesworthia, and “Candidatus Blochmannia” form a huge clade of symbiotic microorganisms related to the family of the Enterobacteriaceae within the γ subgroup of Proteobacteria. Interestingly, aphids, psyllids, and tsetse flies have very specialized diets such as plant sap or blood, which are poor in certain nutrients such as amino acids and vitamins essential to the animals. Accordingly, bacteriocyte symbioses are generally believed to have a nutritional basis in that the bacteria supply such essential metabolites to their host organisms (9). In fact, the recent determination of the genomic sequence of Buchnera sp. strain APS revealed that the bacteria have a markedly reduced genome but have retained anabolic pathways involved in the biosynthesis of essential compounds for the host animals such as essential amino acids. In contrast, anabolic pathways involved in the biosynthesis of nonessential metabolites are largely deleted from the Buchnera genome (19, 21). However, in the case of the Camponotus-“Candidatus Blochmannia” symbiosis, a nutritional basis is not obvious because these animals usually are not food specialists, although some species rely on homopteran honeydew and extrafloral nectaries during certain periods of the year. Thus, the biological function of bacteria belonging to “Candidatus Blochmannia” and a possible advantage of this symbiosis for the two partners remain unknown.

In general, transmission of endosymbiotic bacteria residing in bacteriocytes to the progeny of the insects occurs vertically. The long-lasting vertical transmission of the various endosymbionts, estimated in the range of 50 million to 250 million years, resulted in congruent phylogenetic trees of the symbiotic partners, demonstrating a long-lasting cospeciation of the bacteria and their host animals. Such a cospeciation of the bacteria and their host organisms is well documented in several cases including the Buchnera, Wigglesworthia, and “Candidatus Blochmannia” insect symbioses (2, 7, 8, 17, 20). However, little is known about the transmission process itself, and conflicting accounts exist in the literature. B. aphidicola bacteria are believed to invade eggs prior to oviposition via plasma bridges from nurse cells; alternatively, in viviparous aphid species, young embryos are somehow infected prior to birth (2). The secondary endosymbionts (Sodalis glossinidius) of tsetse flies apparently infect the oocytes via so-called milk glands, but nothing is known about the transmission route of the primary symbionts belonging to the genus Wigglesworthia (1).

In his pioneering work, Blochmann (3) noted that bacteria are present not only in the midgut but also in the ovaries of the ants, suggesting a maternal transmission of the endosymbionts to the next host generation. Recently, we were able to show that the bacteria present in the bacteriocytes of the midgut and in the oocytes of several Camponotus species are indeed identical, although they show some differences in their morphology (18). Investigations conducted in the early 20th century suggested that in C. ligniperdus and F. fusca, the upper part of the ovaries contain cells loaded with bacteria. These cells are associated with the oocytes, and it was assumed that the bacteria in these cells invade the premature oocytes at some developmental stage (6, 10, 13, 15). To gain further insight into the fate of the bacteria during the life span of their host animals, we investigated the distribution of the bacteria in various tissues of queens, workers, and males and during larval development by using light and electron microscopy and in situ hybridization techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ants.

The colonies of C. floridanus were collected in Ft Pierce, Fla. Ants were cultivated at constant temperature (25°C), 50% humidity, and a 12-h/12-h day/night rhythm. They were fed with honey water and cockroaches (Nauphoeta cinera) twice a week. Under these conditions, queens produce eggs throughout the year. To obtain males derived from workers, groups of young workers were isolated from their queenright colony. After 4 to 6 weeks, they started egg production. Queens produce males periodically (approximately once a year). The exact age of the various larvae is difficult to estimate. Accordingly, they were classified on the basis of their size into three different stages: larvae up to 2 mm, larvae between 2 and 4 mm, and larvae between 4 and 6.5 mm.

Microscopic techniques.

Midgut preparations were fixed in a solution of 4% buffered paraformaldehyde plus 1% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4°C. After being washed with a 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), the tissue samples were fixed for 90 to 120 min in 2% buffered OsO4 solution and washed with water. The samples were stained overnight in 0.5% uranyl acetate, washed with water, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and embedded in Epon. For light microscopic analysis, 1- to 5-μm-thick histological sections of the tissue samples were stained with methylene blue for 1 min. For electron microscopic analysis, ultrathin sections were stained with 2% methanolic uranyl acetate for 20 min and with lead citrate for an additional 10 min.

In situ hybridization.

The oligonucleotides used for in situ hybridization were previously described by Schröder et al. (18). The oligonucleotides were labeled enzymatically with digoxigenin-11-ddUTP by terminal transferase (Boehringer Mannheim) as specified by the manufacturer. Cryosections from midguts and different-sized larvae were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline pH 7,2, for 30 min at 4°C. After being rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, they were incubated for 15 min with 0.5 μg of proteinase K per ml, rinsed, and fixed again as described above. Hybridization was carried out overnight at 37°C (for the flori3 oligonucleotides) with 60 ng of labeled oligonucleotide in 20 μl of 5× SET hybridization buffer (5× SET is 0.75 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1 M Tris, 0.2% blocking reagent [Boehringer Mannheim], and 0.025% sodium dodecyl sulfate). The slides were washed for 15 min. in 0.2× SET at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was blocked by covering the slides for 30 min with a solution containing 100 mM maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% blocking reagent. The slides were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Fab fragment specific for the digoxigenin moiety (Boehringer Mannheim). Unbound Fab fragments were removed by washing with a solution containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2 (pH 9.5). Alkaline phosphatase activity was visualized by observing the formation of a dark colored insoluble precipitate. As a substrate, a 1:50 dilution of the nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate stock solution (Boehringer Mannheim) was used prepared in a solution containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2 (pH 9.5).

Antibiotic treatment.

After a starvation period of 3 days, several groups of C. floridanus workers were fed with 1% (wt/vol) rifampin-honey or tetracycline-honey solution on days 4 and 7, respectively. Then the animals were fed normally with food devoid of antibiotics for 1 week. This alternating application of food enriched with antibiotics and of normal food was repeated four times. After 8 weeks, the animals were either sacrificed to analyze their bacterial load or further cultivated under normal conditions for several months for further investigations.

RESULTS

Distribution of the endosymbiotic bacteria in tissues of workers, queens, and males of C. floridanus.

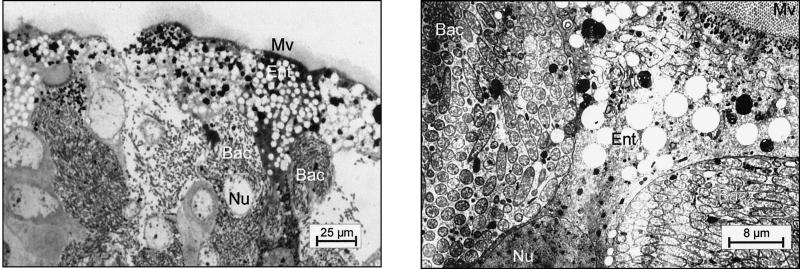

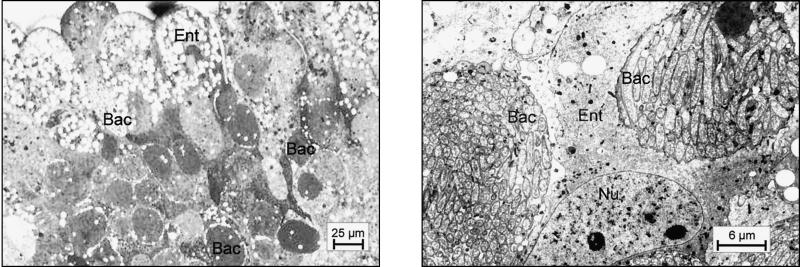

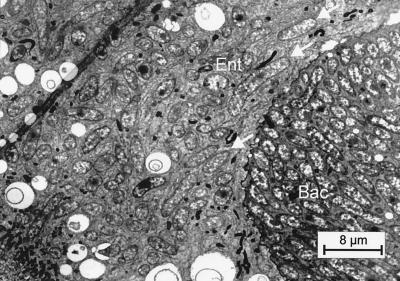

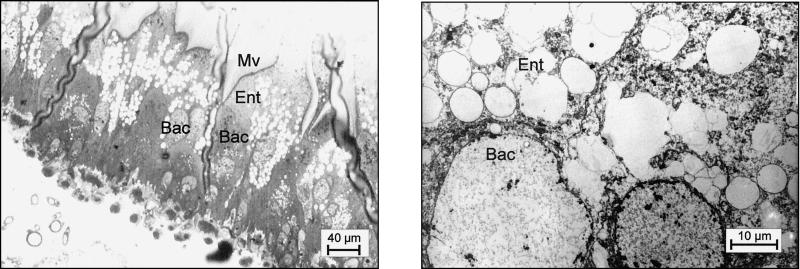

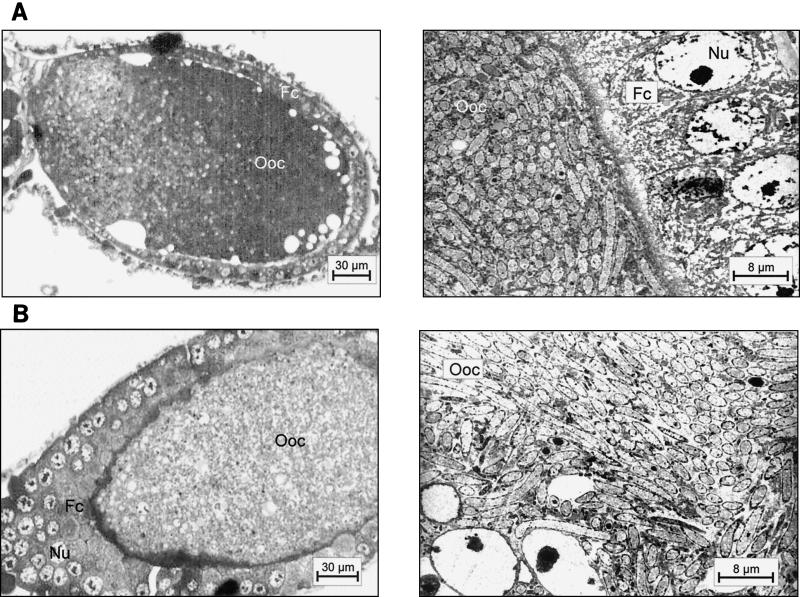

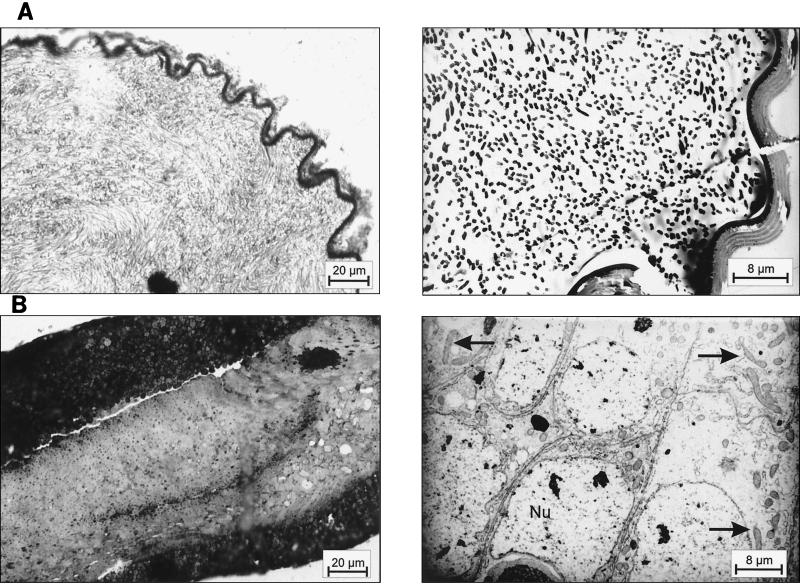

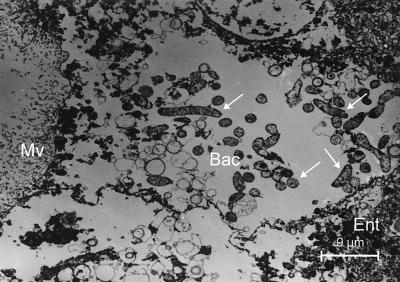

As shown previously, small and large workers of C. floridanus contain many bacteriocytes within their midgut epithelium (18). These bacteriocytes are entirely filled with endosymbiotic bacteria apparently floating freely in the cytoplasm of the host cells (Fig. 1). Very similar findings were made in young virgin queens of C. floridanus (Fig. 2) or males derived from queens or workers (Fig. 3). In C. floridanus males, however, bacteria were also located in normal enterocytes. Similar to the situation in bacteriocytes, no membrane structures surrounding these bacteria could be detected, indicating that they exist unrestrained in the cytosol (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, mature queens several years old differed in a remarkable way from young virgin queens. Although these older individuals had a high bacterial load in their ovaries, their midgut harbored for fewer bacteriocytes, which contain only very few or no bacteria at all (Fig. 4). In the ovaries of workers and queens, we found bacteria exclusively in oocytes but never in associated cells (Fig. 5). This held true even for the apical regions of the ovarioles containing premature oocytes (data not shown). The spermathecae of mated queens did not contain bacteria, although occasionally a few bacteria were detected in the testicles of males (Fig. 6).

FIG. 1.

Bacteriocytes in the midgut of a C. floridanus worker. (Left) Methylene blue-stained thin section of the midgut; (right) electron micrograph showing an enlargement of a typical region. Ent, enterocyte; Mv, microvilli; Bac, bacteriocyte; Nu, nucleus.

FIG. 2.

Bacteriocytes in the midgut of a virgin queen. (Left) methylene blue-stained thin section of the midgut epithelium; (right) electron micrograph showing an enlargement of a typical region. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 1.

FIG. 3.

Occurrence of endosymbiotic bacteria in bacteriocytes and enterocytes of a male derived from a queen. The electron micrograph shows a typical bacteriocyte filled with bacteria and nearby enterocytes also harboring the endosymbionts, some of which are marked with white arrows. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 1.

FIG. 4.

Empty bacteriocytes in the midgut of a mature queen. (Left) Methylene blue-stained thin section of the midgut epithelium; (right) electron micrograph showing an enlargement of a typical region. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 1.

FIG. 5.

(A) Ovary of a mature queen showing an oocyte (Ooc) filled with bacteria and associated follicle cells (Fc). (Left) Methylene blue-stained thin section; (right) electron micrograph of an oocyte surrounded by follicle cells. (B) Ovary of a worker showing an oocyte (Ooc) filled with bacteria and associated follicle cells (Fc). (Left) methylene blue-stained thin section; (right) electron micrograph of the cytoplasm of an oocyte. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 1.

FIG. 6.

(A) The spermatheca of a mature queen does not harbor endosymbiotic bacteria. (Left) Methylene blue-stained thin section of the spermatheca; (right) electron micrograph. (B) The testicle of a male harbors only few endosymbiotic bacteria. (Left) Methylene blue-stained thin section of the testicle; (right) electron micrograph. The arrows indicate the presence of some bacteria.

Distribution of “Candidatus Blochmannia floridanus” during embryogenesis and larval development of C. floridanus.

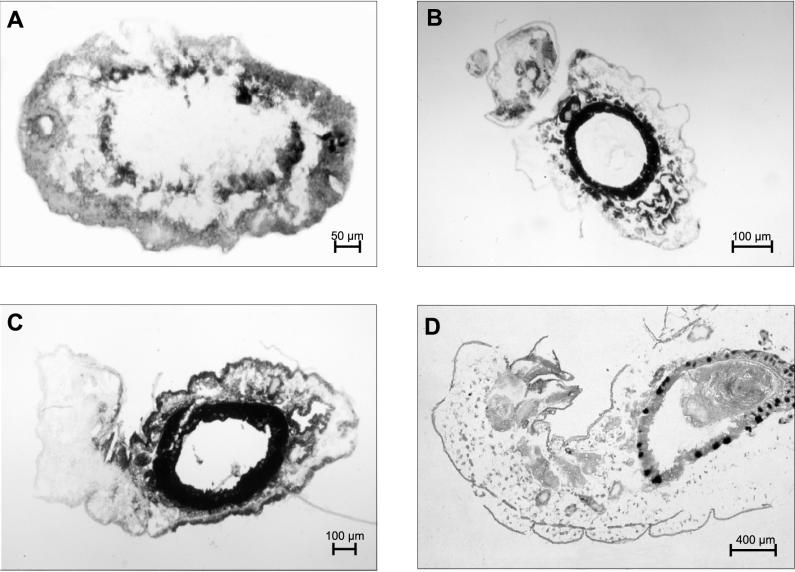

In situ hybridization with digoxygenin-labeled oligonucleotide probes complementary to 16S RNA of B. floridanus enabled us to investigate the distribution and migration of the endosymbionts during various developmental stages. In freshly laid eggs, most of the bacteria were found in a central ring-like structure which corresponds to an endodermal region forming the midgut in later stages of embryogenesis (Fig. 7). The strong association of the bacteria with these endodermal tissues became even more evident in later phases and during larval development, when the gut tissue surrounding an internal cavity had already formed. However, in various developmental stages, the bacteria could also be detected in tissues which should not be of endodermal origin (Fig. 7). The preparation of the fragile embryos for microscopic analysis is very artifact prone. We were therefore not yet able to elucidate conclusively in early developmental stages whether the bacteria are located intra- or extracellularly. However, prior to pupae formation, the bacteria were detected exclusively intracellularly in bacteriocytes within the midgut epithelium (Fig. 7). Interestingly, in these larvae the bacteriocytes generally appeared to be located on the basolateral side of the midgut epithelium, whereas in adult animals the location of the bacteriocytes was more variable and the bacteriocytes occasionally were even in contact with the midgut lumen (Fig. 1).

FIG. 7.

In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled C. floridanus-specific oligonucleotides of cryosections of various developmental stages. A black area indicates the presence of bacteria. (A) Freshly laid egg; (B) 1-mm larva; (C) 3 mm larva; (D) 6-mm larva; (E) negative control.

Effect of antibiotic treatment on workers of C. floridanus.

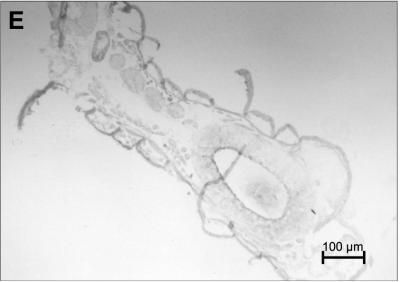

To investigate whether the symbiosis between bacteria and C. floridanus is obligatory for both partners, we attempted to cleanse the ants of their symbionts by treating them with antibiotics. The workers were fed with honey water enriched with chloramphenicol, Ciprobay 200, rifampin, or tetracyline. A significant effect on the bacteria could be detected only after rifampin or tetracycline treatment, which caused nearly complete clearance of the bacteria from their hosts. In fact, in such treated animals, bacteria could be detected only sporadically (Fig. 8). We cannot say whether the few remaining bacteria were still viable. However, treated workers that were exposed to normal feeding for a subsequent period of 13 weeks did not show any traces of bacteria in their bacteriocytes. It is noteworthy that tetracycline, but not rifampin, caused significant damage to the midgut tisues of the ants, but after a period of up to 13 weeks the gut epithelium recovered, showing a normal appearance with the exception that the bacteriocytes were empty and appeared somehow collapsed. During this period, most animals recovered entirely and no difference between the drug-treated animals and the control group could be noted with regard to feeding behaviour or general colony appearance (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Electron micrograph of the midgut tissue of C. floridanus immediately after the end of tetracycline treatment. The arrows indicate the presence of several residual bacteria in this particular bacteriocyte. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

The present study follows up on investigations conducted many decades ago, which, in the long term, aim at an understanding of the biological significance of the endosymbiosis between intracellular bacteria and their ant hosts. These early studies had already revealed fascinating insights in the biology of the symbiosis of bacteria with ants of the genera Camponotus and Formica, but they remained inconclusive and controversial, e.g., regarding the question of how the bacteria enter the oocytes and whether the bacteria are also located in follicle or nurse cells surrounding the oocytes (3, 6, 10, 13). For example, an invasion of bacteria from the midgut bacteriocytes was reported which was believed to be followed by massive infiltration of the bacteria into the nearby ovarioles (5). In the ovarioles the bacteria may then invade oocyte-associated cells (5, 13), from which they ought to be transferred to the developing oocytes in an unknown way. To readdress the issue of oocyte invasion, we attempted to identify the bacteria in all parts of the ovaries including those containing premature oocytes. We detected bacteria exclusively in the oocytes and never in other cell types such as trophocytes, follicular epithelium, or interfollicular tissue. This still leaves unsolved the question of how the bacteria reach the oocytes.

Interestingly, although males appear to represent dead ends for the symbionts, a few bacteria were occasionally detected in the testis follicles, indicating that in males a similar migration of the bacteria to that in the female individuals may take place, albeit apparently with low efficiency. The presence of bacteria in the testes obviously is not relevant for the transmission to the next generation of hosts, because no bacteria could be detected in the spermathecae of young mated queens, confirming the exclusive maternal transmission route of the bacteria.

In the freshly laid eggs, the bacteria quickly become associated with endodermal tissue forming the midgut. However, in situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled bacterium-specific oligonucleotides shows that at the various developmental stages significant numbers of bacteria are also present in other tissues. In fact, only in the last-instar larvae could the bacteria be detected exclusively in the midgut tissue within typical bacteriocytes. We could not determine whether this migration of the endosymbionts within the developing animal is accomplished by extracellular bacteria or by movements of bacterium-filled cells. However, these data may be reconciled with early observations made by Buchner and Hecht, who described movements of bacterium-filled cells and even relocation of the bacteria from one cell type to another (5, 10). In particular they described the occurrence of “primary bacteriocytes” with a very short life span at early stages of embryogenesis. After the degeneration of these cells, the bacteria were presumed to be taken up by so-called “definitive bacteriocytes.” Apart from their presence in bacteriocytes, Hecht found that during embryogenesis, the bacteria were also transiently present in large syncytial giant cells (10). Migration of bacteriocytes and the existence of bacterium-containing syncytia is in concordance with our observations of bacterium-specific staining in parts of the developing animals outside of the endodermal region.

Prior to pupa formation, the larval midgut very much resembles that of adult animals. In fact, the only obvious difference between the larval and adult midgut tissues concerns the shape and position of the bacteriocytes. These structures are smaller in the larvae, are found mainly on the basolateral side of the enterocytes, and do not face the lumen of the midgut. In adult animals the distribution of the bacteriocytes is less ordered and bacteriocytes may even come in contact with the midgut lumen. An interesting exception is observed in males of C. floridanus, in which the bacteria are found in enterocytes as well as in the bacteriocytes. Similar to the situation in bacteriocytes, the bacteria present in the enterocytes apparently are not confined to vacuoles. It is not yet known whether the presence of bacteria in enterocytes of males is the result of an active invasion process of bacteriocyte-derived bacteria.

Interestingly, in contrast to young virgin queens, mature queens several years of age showed a strong degeneration of the bacteriocytes and an elimination of the endosymbionts from the midgut, indicating an age-dependent decrease of the endosymbiont population in the midgut, although the bacterial load in the ovaries of the same insects remained unchanged. Such a phenomenon could not be observed with males or workers of C. floridanus; however, these animals have a comparatively short life span not exceeding several weeks or months, respectively, whereas a Camponotus queen can live and reproduce for more than 10 years. Some degree of bacteriocyte degeneration was also reported for small and large workers of C. ligniperdus reaching an age of more than 40 weeks (13). Ants given from antibiotic treatment did not show any residue of endosymbionts; this suggests that either the few bacteria detected directly after antibiotic administration were not viable or, in contrast to the bacteria present in eggs, larvae, and pupae, the symbionts present in bacteriocytes of adult animals cannot multiply efficiently. Furthermore, antibiotic treatment of the workers apparently did not interfere negatively with their health after they had survived and recovered from the treatment under standard cultivation conditions. It is therefore possible that the Camponotus-“Candidatus Blochmannia” endosymbiosis is most important during embryogenesis and larval development and may play a minor or no role in the biology of adult animals. The adult host animals may even tolerate the degeneration of the symbiosis once the transmission of the symbionts to the next generation is accomplished.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dagmar Beier, Jürgen Gadau, Michael Kuhn, and Evi Zientz for critical reading of the manuscript and for many discussions.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB567/C2) and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aksoy, S., X. Chen, and V. Hypsa. 1997. Phylogeny and potential transmission routes of midgut-associated endosymbionts of tsetse (Diptera: Glossinidae). Insect Mol. Biol. 6:183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann, P., L. Baumann, C. Y. Lai, D. Rouhbakhsh, N. A. Moran, and M. A. Clark. 1995. Genetics, physiology, and evolutionary relationships of the genus Buchnera: intracellular symbionts of aphids. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:55-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blochmann, F. 1882. Über das Vorkommen bakterienähnlicher Gebilde in den Geweben und Eiern verschiedener Insekten. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 11:234-240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolton, B. 1996. A new general catalogue of the ants of the world. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- 5.Buchner, P. 1918. Vergleichende Eistudien. I. Die akzessorischen Kerne des Hymenoptereneies. Arch. Mikroskop. Anat. II 91:70-88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchner, P. 1965. Endosymbiosis of animals with plant microorganisms. Intersciences Publishers Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 7.Chen, X., S. Li, and S. Aksoy. 1999. Concordant evolution of a symbiont with its host insect species: molecular phylogeny of genus Glossina and its bacteriome-associated endosymbiont, Wigglesworthia glossinidia. J. Mol. Evol. 48:49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, M. A., L. Baumann, M. L. Thao, N. A. Moran, and P. Baumann. 2001. Degenerative minimalism in the genome of a psyllid endosymbiont. J. Bacteriol. 183:1853-1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas, A. E. 1998. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbiosis: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43:17-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecht, O. 1924. Embryonalentwicklung und Symbiose bei Camponotus ligniperda. Z. Wiss. Zool. 122:173-204. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hölldobler, B., and E. O. Wilson. 1990. The ants. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- 12.Jungen, H. 1968. Endosymbionten bei Ameisen. Insect Soc. 15:227-232. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolb, G. 1959. Untersuchungen über die Kernverhältnisse und morphologischen Eigenschaften symbiontischer Mikroorganismen bei verschiedenen Insekten. Z. Morphol. Ökol. Tiere 48:1-71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanham, U. N. 1968. The Blochmann bodies: hereditary intracellular symbionts of insects. Biol. Rev. 43:269-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lilienstern, M. 1932. Beiträge zur Bakteriensymbiose der Ameisen. Z. Morphol. Ökol. Tiere 26:110-134. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelloquin, J. J., S. G. Miller, S. A. Klotz, R. Stouhammer, L. R. Davis, and J. H. Klotz. 2001. Bacterial endosymbionts from the genus Camponotus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology 38(3B):695-708. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sauer, C., E. Stackebrandt, J. Gadau, B. Hölldobler, and R. Gross. 2000. Systematical characterization and congruent evolution of Camponotus species and their endosymbiotic bacteria: proposal of a novel taxon Candidatus Blochmannia (gen. nov.). Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:1877-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schröder, D., H. Deppisch, M. Obermayer, G. Krohne, E. Stackebrandt, B. Hölldobler, W. Goebel, and R. Gross. 1996. Intracellular endosymbiotic bacteria of Camponotus species (carpenter ants): systematics, evolution and ultrastructural analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 21:479-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigenobu, S., H. Watanabe, M. Hattori, Y. Sakaki, and H. Ishikawa. 2000. Genome sequence of the endocellular bacterial symbiont of aphids Buchnera sp. APS. Nature 407:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spaulding, A. W., and C. D. von Dohlen. 2000. Psyllid endosymbionts exhibit patterns of co-speciation with hosts and destabilizing mutations in ribosomal RNA. Insec. Mol. Biol. 10:57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zientz, E., F. J. Silva, and R. Gross. 2001. Genome interdependence in insect-bacterium symbioses. Genome Biol. 2:1032.1-1032.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]