Abstract

Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT) remains standard of care for eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM), although recently its role has been questioned. The aim of the study was to evaluate trends in patient characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of NDMM who underwent upfront auto-SCT over three decades. We conducted a single-center retrospective analysis of patients with NDMM who underwent upfront auto-SCT at MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1988 to 2021. Primary end points were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Patients were grouped by the year of auto-SCT: 1988–2000 (n = 249), 2001–2005 (n = 373), 2006–2010 (n = 568), 2011–2015 (n = 815) and 2016–2021 (n = 1036). High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities were defined as del (17p), t (4;14), t (14;16), and 1q21 gain or amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization. We included 3041 MM patients in the analysis. Median age at auto-SCT increased from 52 years (1988–2000) to 62 years (2016–2021), as did the incidence of high-risk cytogenetics from 15% to 40% (P < .001). Comorbidity burden, as measured by a Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-Specific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) of >3, increased from 17% (1988–2000) to 28% (2016–2021) (P < .001). Induction regimens evolved from predominantly chemotherapy to immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) and proteasome inhibitor (PI) based regimens, with 74% of patients receiving IMiD-PI triplets in 2016–2021 (39% bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRD) and 35% carfilzomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone [KRD]). Response rates prior to auto-SCT steadily increased, with 4% and 10% achieving a ≥CR and ≥VGPR compared to 19% and 65% between 1988–2000 and 2016–2021, respectively. Day 100 response rates post auto-SCT improved from 24% and 49% achieving ≥CR and ≥VGPR between 1988–2000 to 41% and 81% between 2016–2021, respectively. Median PFS improved from 22.3 months between 1988–2000 to 58.6 months between 2016–2021 (HR 0.42, P < .001). Among patients with high-risk cytogenetics, median PFS increased from 13.7 months to 36.8 months (HR 0.32, P < .001). Patients aged ≥65 years also had an improvement in median PFS from 33.6 months between 2001 and 2005 to 52.8 months between 2016–2021 (HR 0.56, P = .001). Median OS improved from 55.1 months between 1988–2000 to not reached (HR 0.41, P < .001). Patients with high-risk cytogenetics had an improvement in median OS from 32.9 months to 66.5 months between 2016–2021 (HR 0.39, P < .001). Day 100 non-relapse mortality from 2001 onwards was ≤1%. Age-adjust rates of second primary malignancies were similar in patients transplanted in different time periods. Despite increasing patient age and comorbidity burden, this large real-world study demonstrated significant improvements in the depth of response and survival outcomes in patients with NDMM undergoing upfront auto-SCT over the past three decades, including those with high-risk disease.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Transplantation, Autologous

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell disorder accounting for nearly 2% of cancer diagnoses, with an increasing incidence in recent years [1]. It is characterized by the proliferation of malignant plasma cells within the bone marrow, with production of monoclonal proteins and end-organ damage [2]. Significant progress has been made in the treatment of MM over the past few decades, with continuously improving induction and salvage regimens, alongside the widespread use of post-transplant maintenance therapies. It is well established that induction regimens containing immunomodulatory agents (IMiDs) and proteasome inhibitors (PI) are superior to chemotherapy alone [3–6]. Similarly, three drug induction regimens have improved response rates and survival outcomes compared to two drug regimens [7–9]. Maintenance therapy has further improved outcomes and is now routinely used [10]. Despite considerable change in the landscape of anti-myeloma therapies, upfront autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT) has remained standard of care for newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) patients [11].

While remarkable advancements have been made in MM therapeutics, achieving a cure remains elusive, with most patients experiencing relapse following contemporary anti-myeloma induction regimens and auto-SCT. Several population-based studies have shown steady improvement in survival, but disparities have been reported among several patient subgroups, including older patients [12,13] and those with high-risk cytogenetics [14]. Although real-world studies have shown consistent improvements in overall survival (OS), there have been conflicting reports on trends in progression-free survival (PFS) in recent years [14–16]. Population-based analyses remain crucial for assessing real-world outcomes since many patients who have received treatment would not have met the eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials.

In this study we examined survival trends in a large cohort of MM patients who underwent upfront auto-SCT at MD Anderson Cancer Center over the past three decades. Further, we also studied the evolving patient characteristics and treatment trends in the last three decades.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, single-center, chart review study of patients with NDMM who underwent upfront auto-SCT between 1988 and 2021. Data were obtained from our institution’s transplant database. Primary end points were PFS and OS. Secondary endpoints were hematological response and minimal residual disease (MRD) status after auto-SCT. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Patients were grouped by the year of transplantation as follows: 1988–2000, 2001–2005, 2006–2010, 2011–2015, and 2016–2021. Response rates were assessed in accordance with criteria established by the International Myeloma Working Group [17]. To evaluate the MRD status in bone marrow samples, we employed an 8-color next-generation flow cytometry (NGF) technique. Sensitivity of our assay is 1/10−5 cells (0.001%) as determined by the acquisition and analysis of a minimum of 2 million events. We performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis to identify high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, specifically t (4;14), t (14;16), del (17p), and 1q21 gain or amplification. The FISH probe sets used were IGH::FGFR3 dual-color dual-fusion probes, IGH::MAF dual-color dual-fusion probes, TP53/CEP17 dual-color probes, and CDKN2C/CKS1B dual-color probes. The routine use of the myeloma FISH panel at MD Anderson Cancer Center started in 2013, while the enrichment of plasma cells by CD-138 selection started in 2021.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, presenting median (range) for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. OS time was computed from the date of auto-SCT to either the date of death or the last follow-up. PFS time was computed from the date of auto-SCT to either the date of disease progression, death (if occurred without disease progression), or the last follow-up. Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and group differences were assessed using the log-rank test. Associations between demographic and clinical factors and survival outcomes were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Measures obtained after auto-SCT (e.g., 100-day and best response, MRD after auto-SCT and maintenance treatment) were included in the Cox model as time-dependent covariates. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was computed from the date of auto-SCT to either the date of death or the last follow-up and estimated using the competing risks method, where progression was the competing risk. A significance level of 5% was used for all statistical tests, and no adjustments for multiple testing were applied. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 for Windows (Copyright © 2002–2012 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient, Disease, and Treatment Characteristics

A total of 3041 patients with NDMM who underwent upfront auto-SCT were included in our study. Median age at auto-SCT increased over time, from 52 years (range 23–71) in 1988–2000 to 62 years (range 29–83) in 2016–2021 (P < .001), with only 1% of patients ≥65 years of age in 1988–2000 compared to 38% in 2016–2021 (P < .001). In patients with known cytogenetics, the incidence of high-risk cytogenetics increased over the study period, from 15% to 40% in 1988–2000 and 2016–2021, respectively (P < .001). Disease risk by Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) stage remained stable over time, with R-ISS stage III in 7%−11% of patients throughout the study period (P = .54). The comorbidity burden, as measured by the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-Specific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI), increased over time, with HCT-CI > 3 in 17% of patients in 1988–2000 compared to 28% in 2016–2021 (P < .001).

Induction regimens evolved over time, from predominately conventional chemotherapy (39%) in 1988–2000 to IMiD and PI-based regimens, with 74% receiving an IMiD-PI containing triplet (39% bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRD) and 35% carfilzomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone [KRD]) between 2016–2021 (P < .001). In 1988–2000, the primary conditioning regimen consisted of thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide, which was used in 47% of patients. Starting in the year 2000, single agent melphalan became the predominant regimen, with >75% patients receiving melphalan alone during each time period. A combination of busulfan and melphalan was increasingly used after 2005, with 5%, 12%, and 18% of patients receiving this conditioning regimen between 2006–2010, 2011–2015, and 2016–2021, respectively. The use of maintenance therapy fluctuated, with 73% of patients receiving maintenance between 1988–2000, decreasing to 30% in 2001–2005 and increasing to >80% from 2011 onwards. The most common maintenance regimens after 2005 were lenalidomide-based, administered to at least 77% of patients from 2006 onwards. Table 1 summarizes patient and disease characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Time Period | P-Value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988–2000 (N = 249) |

2001–2005 (N = 373) |

2006–2010 (N = 568) |

2011–2015 (N = 815) |

2016–2021 (N = 1,036) |

||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 166 (67) | 224 (60) | 333 (59) | 468 (57) | 622 (60) | .13 |

| Female | 83 (33) | 149 (40) | 235 (41) | 347 (43) | 414 (40) | |

| Age at auto-SCT (years) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 51.7 (22.7, 70.9) | 55.8 (29.4, 77.4) | 59.6 (31.0, 80.6) | 61.6 (25.4, 80.3) | 62.3 (29.0, 83.0) | < .001† |

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| <65 years | 247 (99) | 327 (88) | 413 (73) | 526 (65) | 638 (62) | < .001‡ |

| ≥65 years | 2 (1) | 46 (12) | 155 (27) | 289 (35) | 398 (38) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Black | 22 (9) | 63 (17) | 95 (17) | 141 (18) | 198 (19) | .004 |

| Non-black | 224 (91) | 307 (83) | 463 (83) | 655 (82) | 822 (81) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 3 | 10 | 19 | 16 | |

| Light chain type, n (%) | ||||||

| Kappa | 142 (65) | 228 (62) | 371 (66) | 532 (66) | 682 (66) | .67 |

| Lambda | 73 (33) | 137 (37) | 191 (34) | 272 (34) | 346 (34) | .75 |

| Biclonal | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 7 (1) | 1 (<1) | .011§ |

| Unknown | 30 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 7 | |

| Cytogenetic risk, n (%) | ||||||

| Standard | 47 (85) | 254 (87) | 474 (93) | 605 (78) | 582 (60) | < .001 |

| High | 8 (15) | 38 (13) | 37 (7) | 168 (22) | 389 (40) | |

| Unknown | 194 | 81 | 57 | 42 | 65 | |

| R-ISS, n (%) | ||||||

| I | 8 (21) | 32 (34) | 88 (35) | 203 (37) | 268 (34) | .54 |

| II | 26 (68) | 55 (59) | 142 (57) | 299 (55) | 443 (56) | |

| III | 4 (11) | 7 (7) | 21 (8) | 45 (8) | 83 (10) | |

| Unknown | 211 | 279 | 317 | 268 | 242 | |

| HCTCI, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤3 | 53 (83) | 304 (82) | 444 (78) | 637 (78) | 742 (72) | < .001 |

| >3 | 11 (17) | 69 (18) | 123 (22) | 177 (22) | 293 (28) | |

| Induction regimen, n (%) | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 98 (40) | 81 (22) | 20 (4) | 32 (4) | 7 (1) | < .001* |

| IMiD-based doublets | 4 (2) | 198 (53) | 216 (38) | 64 (8) | 19 (2) | |

| KRD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (<1) | 362 (35) | |

| VCD | 0 | 0 | 45 (8) | 155 (19) | 101 (10) | |

| VD | 0 | 2 (1) | 107 (19) | 167 (20) | 64 (6) | |

| VRD | 0 | 0 | 60 (11) | 298 (37) | 407 (39) | |

| Other | 146 (59) | 91 (24) | 120 (21) | 97 (12) | 75 (7) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Post-induction response, n (%) | ||||||

| sCR/CR | 9 (4) | 29 (8) | 39 (7) | 89 (11) | 197 (19) | < .001‡ |

| VGPR | 16 (6) | 62 (17) | 237 (42) | 333 (41) | 479 (46) | |

| PR | 134 (54) | 235 (63) | 277 (49) | 375 (46) | 339 (33) | |

| SD | 87 (35) | 44 (12) | 15 (3) | 18 (2) | 21 (2) | |

| PD | 1 (<1) | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | ||||||

| Mel | 55 (22) | 297 (80) | 495 (87) | 708 (87) | 780 (75) | < .001‡ |

| Mel-based other | 70 (28) | 70 (19) | 44 (8) | 13 (2) | 44 (4) | |

| BuMel based | 0 | 6 (2) | 29 (5) | 94 (12) | 182 (18) | |

| Thiotepa/Bu/Cy | 118 (47) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 6 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 (3) | |

| Any maintenance, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 181 (73) | 112 (30) | 231 (41) | 673 (83) | 848 (82) | < .001 |

| No | 68 (27) | 261 (70) | 337 (59) | 142 (17) | 188 (18) | |

| Maintenance, n (%) | ||||||

| Len +/−Dexa | 0 | 6 (5) | 173 (75) | 515 (77) | 664 (78) | < .001‡ |

| Imid +/−Dexa∥ | 40 (22) | 66 (59) | 43 (19) | 3 (<1) | 6 (1) | |

| PI +/−Dexa | 0 | 3 (3) | 9 (4) | 63 (9) | 69 (8) | |

| Other | 141 (78) | 37 (33) | 6 (3) | 92 (14) | 109 (13) | |

Chi-squared test.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Chi-squared test was used due to computational issues using exact tests.

Generalization of Fisher’s exact test.

Includes: thalidomide + dexamethasone and pomalidomide + dexamethasone.

Abbreviations: auto-SCT = autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; Bu/Cy = busulfan/cyclophosphamide; BuMel = busulfan + melphalan; CR = complete response; Dexa = dexamethasone; HCT-CI = hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity Index; IMiD = immunomodulatory drug; KRD = carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone; Len = lenalidomide; Mel = melphalan; nCR = near complete response; PD = progressive disease; PI = proteasome inhibitor; PR = partial response; R-ISS = revised international staging system; sCR = stringent complete response; SD = stable disease; VCD = bortezomib + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone; VD = bortezomib + dexamethasone; VGPR = very good partial response; VRD = bortezomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone.

Response Rates and MRD

After completing induction therapy and prior to transplantation, response rates steadily increased throughout the study period, with 4% and 10% of patients achieving a ≥complete response (CR) and ≥very good partial response (VGPR) between 1988–2000, and 19% and 65% of patients achieving a ≥ CR and ≥ VGPR between 2016–2021, respectively (P < .001). MRD testing was infrequent before 2011, with an incidence of MRD negative responses prior to transplant of 58% and 57% in 2011–2015 and 2016–2021, respectively.

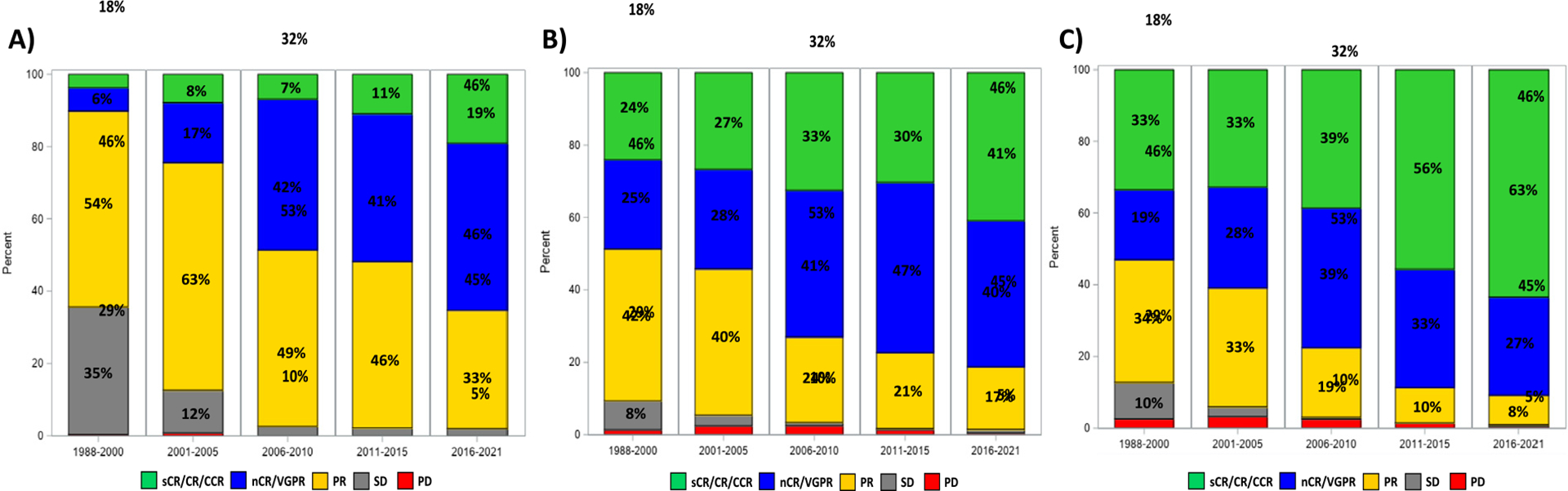

Day 100 post-transplant response rates steadily increased over time. Between 1988–2000, 24% and 49% of patients achieved a ≥CR and ≥VGPR, respectively, compared to 41% and 81% between 2016–2021. Similarly, best post-transplant response rates improved over time, with 33% and 53% reaching a ≥CR and ≥VGPR between 1988–2000, and 63% and 91% achieving these responses between 2016–2021, respectively. Post-transplant MRD negative responses were observed in 75% and 63% of assessed cases in 2011–2015 and 2016–2021, respectively. Pre- and post-transplant hematological responses are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hematological responses according to year of transplant: (A) prior to transplant, (B) at day 100 after transplant, and (C) at best post-transplant response.

Survival Outcomes

As expected, the median follow-up duration for survivors varied across cohorts: 1988–2000 (238.9 months, range 18.6–327.4), 2001–2005 (184.5 months, range 1.1–254.9), 2006–2010 (142.2 months, range 5.8–196.4), 2011–2015 (80.5 months, range 0.9–129.3), and 2016–2021 (26.9 months, range 0.7–75.2) (P < .001).

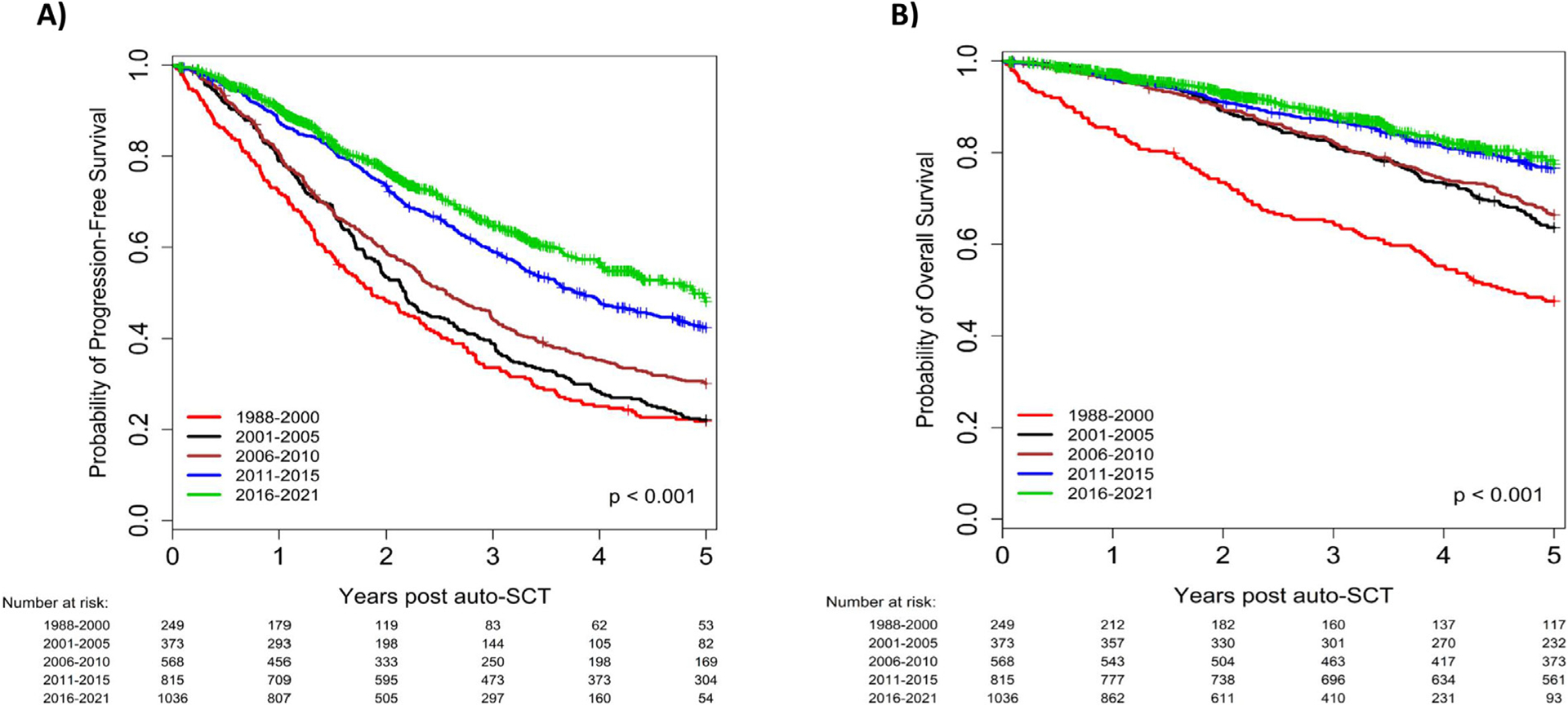

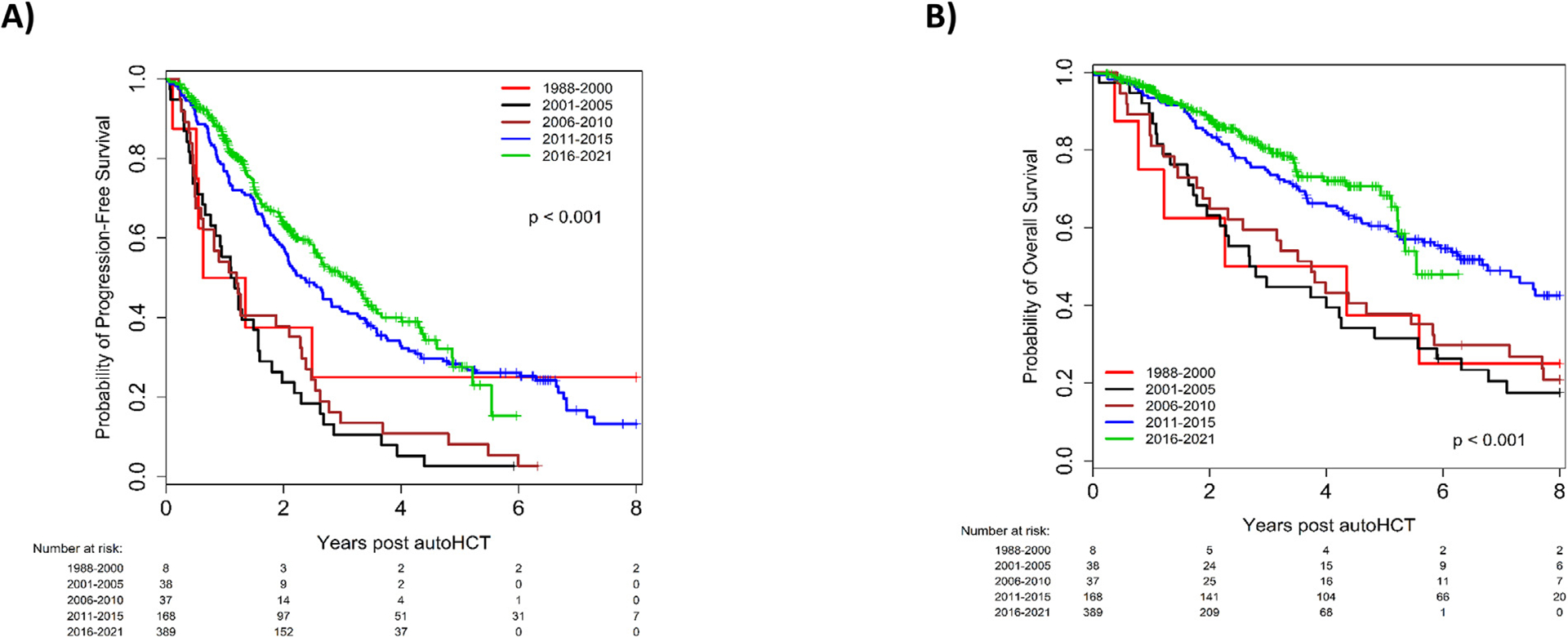

The median PFS in the entire study population was 38.3 months, which improved from 22.3 months between 1988–2000 to 58.6 months between 2016–2021 (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.34–0.48, P < .001; Figure 2A). Notably, patients with high-risk cytogenetics also had a significant improvement in PFS in recent years, with a median PFS of 28.0 months in 2011–2015 (HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.26–0.55, P < .001) and 36.8 months in 2016–2021 (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.22–0.45, P < .001), compared to only 13.7 months in 2001–2005 (Figure 3A). Patients aged ≥65 years also had a significant improvement in median PFS over time from 33.6 months between 2001 and 2005 to 52.8 months between 2016–2021 (P < .001). There was no significant difference in PFS within the R-ISS stage III cohort based on time of transplant. Univariate analyses for PFS in the entire cohort and in specific subgroups are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B), according to year of transplant; entire cohort.

Figure 3.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B), according to year of transplant; patients with high-risk multiple myeloma.

In multivariable analysis (MVA), undergoing auto-SCT in 2016–2021 (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.45–0.76, P < .001) was associated with significantly improved PFS compared to 1988–2000. Other variables that were associated with significantly better PFS in MVA included biclonal light chain type (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32–1.00, P = .048) compared to kappa light chain disease); achieving MRD negative ≥CR prior to auto-SCT (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.42–0.70, P < .001); achieving MRD negative ≥CR after auto-SCT (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.95, P = .013); and use of post-transplant maintenance therapy (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.96, P = .007). Conversely, variables that were associated with worse PFS in MVA included lambda light chain type (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.33, P < .001) compared to kappa light chain disease; high risk cytogenetics (HR 2.06, 95% CI 1.80–2.36, P < .001); R-ISS stage II (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.00–1.35, P = .045) or stage III (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.22–2.03, P < .001) compared to R-ISS stage I; and conditioning with thiotepa/Bu/Cy (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.08–1.92, P = .012) with melphalan as a reference (Supplementary Table 3).

Median OS was 99.4 months in the entire study population, which steadily improved from 55.1 months in 1988–2000 to not reached in 2016–2021 (HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.24–0.40, P < .001; Figure 2B). For patients with high-risk cytogenetics, OS improved from a median of 32.9 months in 2001–2005 to 66.5 months in 2016–2021 (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.20–0.51, P < .001; Figure 3B). For patients aged ≥ 65 years, median OS improved from 67.2 months in 2001–2005 to not reached in 2016–2021, without reaching a statistically significant difference (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.43–1.05, P = .08). Univariate analyses for OS in the entire cohort and in specific subgroups are presented in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

In MVA, several variables were significantly associated with worse OS including age ≥ 65 years (HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.27–1.73, P < .001); lambda light chain type (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.02–1.32, P = .029) compared to kappa light disease; high-risk cytogenetics (HR 2.25, 95% CI 1.85–2.73, P < .001); R-ISS stage II (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.03–1.59, P = .028) or stage III (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.37–2.72, P < .001) compared to R-ISS stage I; HCT-CI > 3 (HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.16–1.60, P < .001); elevated baseline LDH (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01–1.53, P = .044), whereas achieving CR prior to auto-SCT (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.54–0.90, P = .005); achieving post-transplant MRD negative ≥CR (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46–0.90, P = .010); and use of post-transplant maintenance therapy (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68–0.92, P = .002) were associated with better OS (Supplementary Table 6).

Day 100 NRM in the entire cohort was 1%. Between 1988 and 2000, day 100 NRM was 6%, whereas from 2001 onwards NRM remained ≤1% (P < .001).

Second Primary Malignancies

Two-hundred and ninety-five patients (9.7%) in the entire cohort developed a second primary malignancy (SPM), comprising mostly of solid malignancies (n = 131, 44%), followed by non-melanoma skin malignancies (n = 80, 27%). Sixty-nine patients (23%) developed myeloid malignancies (mostly myelodysplastic syndrome, n = 61) and 13 patients (4%) developed lymphoid malignancies. One-hundred and twenty-three patients (42%) developed SPM after progression of their MM, 63 (21%) developed SPM prior to MM progression, and 109 (37%) developed SPM without MM progression. Patients transplanted in the most recent cohort between 2016–2021 had a trend towards higher 2-year and 3-year SPM rates compared to the 1988–2000 cohort in univariate analysis ([HR 3.48, P = .09] and [HR 2.77, P = .053], respectively). The absolute risk of SPM during the entire follow-up was significantly higher in the 2016–2021 cohort (HR 1.72, P = .038). However, after adjusting for age at transplant, the 2-year and 3-year SPM rates, as well as the overall risk of SPM during the entire follow-up were similar between different cohorts (P = .30, P = .59, and P = .87, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, we observed a gradual improvement in survival outcomes of NDMM patients undergoing upfront auto-SCT over the past three decades. Despite a growing proportion of older patients with increasing co-morbidity burden and more patients with high-risk disease in the later cohorts, patients achieved deeper and more durable responses. Importantly, we observed improved PFS throughout the study period in patients with high-risk NDMM and in patients older than 65. Furthermore, those with high-risk NDMM also had a significant improvement in OS over time.

Significant progress in MM treatment in recent years has improved survival outcomes, largely due to a shift from conventional chemotherapy-based regimens to PI and IMiD-based regimens in both upfront and relapsed settings. Three-drug induction regimens that include IMiDs and PIs are now standard of care, with VRD being the most common induction regimen for both transplant-eligible and ineligible patients [18]. Our data aligns with this trend, as we observed an increase in the use of three-drug regimens over time, with 74% of patients receiving a PI-IMiD-based triplet in the most recent cohort (2016–2021). Median PFS and OS for those receiving VRD induction were 48.7 months and 122.7 months, respectively, while median PFS and OS for those receiving KRD induction were 62.2 months and not reached, respectively. While these results are encouraging, it highlights that even with modern treatments, most patients with MM will ultimately relapse.

The subgroup of patients that received VRD induction (n = 765) in our study had a relatively shorter PFS compared to the PFS from the previously published randomized trials [19] and retrospective analyses [20]. This could be partly explained by a relatively higher proportion of patients with high-risk cytogenetics in this subgroup (32% [226/713 evaluable patients]), and the fact that not all patients received post-transplant maintenance (n = 620, 81%).

Despite significant advancements in the treatment of MM, outcomes in certain subgroups remain suboptimal. Patients with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities have inferior outcomes following auto-SCT compared to standard risk patients. In an analysis from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), patients with high-risk disease had shorter PFS compared to standard-risk patients, with 3-year PFS of 37% versus 49% (P < .001) and OS of 72% versus 85% (P < .001), respectively [21]. In the current study, we found promising outcomes for patients with high-risk cytogenetics who underwent auto-SCT in more recent years. For patients who underwent auto-SCT between 2016–2021, the median PFS was 36.8 months, representing a significant improvement over the 13.7 months observed in the 2001–2005 cohort. This low PFS rate in the earlier cohort can be partly attributed to a low use of post-transplant maintenance at that time. Furthermore, this may partly be attributed to less effective induction therapy that mainly consisted of doublets, rather than triplets, between 2001–2005. For high-risk patients transplanted between 2016–2021 the median OS was 66.5 months, although follow-up for this group remains relatively short, with 84% still alive at the 5-year mark. These findings align with the SWOG-1211 prospective trial, where high-risk NDMM patients who received VRD induction followed by dose-attenuated VRD maintenance until progression achieved a median PFS of 34 months. In that study, high-risk MM was defined by high-risk gene expression profiling, t (14;16), t (14;20), del (17p), amp1q21, primary plasma cell leukemia, or elevated LDH [22]. Similarly, patients with high-risk (t [14;16], t [14;20], del [17p]) untreated MM in the SWOG S0777 trial who received VRD induction followed by continuous Rd consolidation had a median PFS of 38 months [23]. In the phase III randomized DETERMINATION trial, upfront auto-SCT was associated with superior PFS compared to continuous RVD induction [24]. The PFS advantage was observed in patients with high-risk cytogenetics (HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.21–3.26). The PERSEUS trial demonstrated deeper responses and superior PFS for patients who were treated with daratumumab + VRD induction compared to those treated with VRD [25]. The PFS advantage was maintained in the subgroup of patients with high-risk cytogenetics (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.36–0.99).

Of note, the proportion of patients with high-risk cytogenetics in our study increased significantly from 15% in the earliest period to 40% in the most recent period. This is due to several factors, including the increased availability and increased use of Myeloma FISH panel from 2013 at our center, and an increased awareness of poor outcomes of MM patients with high-risk cytogenetics and their increased referral for transplant. We also found that patients with lamda light chain MM had inferior survival outcomes. This observation was made in previous studies [26], including a recent study by our group [27]. However, the impact of having lambda light chain in the general MM population remains uncertain, and additional studies are required to confirm this finding. The Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) reported improved OS for both transplant-eligible (not reached vs. 111 months, P < .0001) and transplant-ineligible MM patients (83.7 months vs. 58.8 months, P < .0001) diagnosed between 2005–2009 and 2010–2014, respectively [14]. However, there was no significant difference in PFS between these two eras for both patient groups. Importantly, the IFM study did not show an improved OS in high-risk patients within the transplant-eligible cohort. In contrast, our analysis demonstrated significant improvements in both PFS and OS among individuals with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities throughout the study period. The differences are likely in part related to maintenance therapy, which was not used in the IFM study, but was used in >80% of patients in our cohort after 2010. Post-transplant lenalidomide maintenance has been shown to improve survival outcomes in MM patients in general [28], and in high-risk patients in particular [29].

We did not examine the impact of monoclonal antibodies on outcomes in our study. Several prospective trials incorporating daratumumab for NDMM, including ALCYONE [30] and MAIA [31] did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit in high-risk MM, although sample sizes were limited. However, a subsequent meta-analysis of these trials suggested that the addition of daratumumab improved outcomes regardless of cytogenetic risk, with superior PFS in both high-risk (pooled HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.47–0.95; P = .02) and standard-risk disease (pooled HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.37–0.54; P < .001) [32]. Future prospective trials will hopefully clarify the role of monoclonal antibodies in MM in the upfront setting, and their impact in patients with high-risk disease.

Our results align with several other published datasets and population-based studies that showed improved outcomes for patients with MM over time. A single-center study in Spain spanning 45 years revealed consistent improvements in relative survival rates, with the most significant gains observed in patients younger than 65 [33]. A nationwide Norwegian registry study with over 10,000 MM patients revealed a gradual increase in relative survival from 1982 to 2017 [15]. Similarly, a CIBMTR analysis of patients with MM who underwent auto-SCT within 12 months of diagnosis showed a gradual improvement in PFS between 1995–1999, 2000–2004 and 2005–2010 [16]. In the latter two cohorts, patients were older, had a lower likelihood of having stage III disease, and were more likely to receive induction therapy with thalidomide, lenalidomide or bortezomib. The analysis showed an incremental improvement in 2-year PFS (50% vs. 55% vs. 57%) and 5-year OS (47% vs. 55% vs. 57%) over these consecutive time periods, respectively. The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) reported an analysis of 117,711 MM patients who received auto-SCT between 1995 and 2019. This study found a considerable improvement in 5-year OS, from 52% to 69%, with only a modest increase in 5-year PFS from 28% to 31% over the same time periods [34]. Similar to our report, NRM decreased from 5.9% to 1.5% during the study period. While population-based studies have shown evolving trends, there are limited real-world studies on this topic. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the largest single-center investigation to date on the treatment and outcomes of an unselected cohort of MM patients who underwent upfront auto-SCT at a single center. Almost 10% of our study cohort developed a SPM during the follow-up. Patients transplanted in earlier cohorts had longer follow-up time to develop the SPM. On the other hand, in recent years auto-SCT was utilized in an increasingly older population, with an inherently higher risk of SPM. Therefore, we compared short-term 2-year and 3-year rates of SPM between patients transplanted in the different time periods. After adjusting for age, we did not find a significant difference between the cohorts. In a recent analysis of the CIBMTR database 4% of MM patients who received auto-SCT developed SPM, after a median of 33 (range 2–96) months [35]. However, in a recent report by our group at MD Anderson Cancer Center, the time to development of SPM was longer, at 40 (range 2–142) months [36]. Thus, in the present study, some of the later SPM might not have been accounted for, even with the higher cut-off of 3-years.

With increasing use of quadruplet regimens containing PIs, IMiDs and monoclonal antibodies, response rates and survival outcomes following auto-SCT are expected to improve even more. While the role of upfront auto-SCT continues to be challenged [24], longer PFS, low NRM, predictable cost, and manageable toxicity support its continued use.

Our study has inherent limitations associated with its retrospective nature, including missing data due to variations in record keeping and data collection. The study population also exhibits significant heterogeneity, making it challenging to account for potential confounders. Additionally, our analysis is limited to patients who underwent upfront auto-SCT, and the findings may not apply to those who did not receive this treatment modality. Nevertheless, this extensive analysis spanning multiple decades provides valuable insights into evolving trends in the characteristics of MM patients undergoing upfront auto-SCT and their outcomes.

In summary, our analysis of over 3,000 NDMM patients who underwent upfront auto-SCT demonstrates significant improvements in response rates and survival over the last three decades, including in the elderly and those with high-risk disease, supporting its role as an effective treatment modality for eligible patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2024.06.001.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure:

This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI Grant P30 CA016672). RZO, the Florence Maude Thomas Cancer Research Professor, would like to acknowledge support from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (SCOR-12206-17), the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA266612), the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the Riney Family Multiple Myeloma Research Fund at MD Anderson from the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: No conflicts of interest declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Padala SA, Barsouk A, Barsouk A, et al. Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar SV. Updated diagnostic criteria and staging system for multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e418–e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harousseau JL, Attal M, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone is superior to vincristine plus doxorubicin plus dexamethasone as induction treatment prior to autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the IFM 2005–01 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(30):4621–4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lokhorst HM, van der Holt B, Zweegman S, et al. A randomized phase 3 study on the effect of thalidomide combined with adriamycin, dexamethasone, and high-dose melphalan, followed by thalidomide maintenance in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;115 (6):1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Gregory WM, et al. Cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone as induction therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients destined for autologous stem-cell transplantation: MRC Myeloma IX randomized trial results. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):442–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IG, van der Holt B, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2946–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet. 2010;376(9758):2075–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreau P, Avet-Loiseau H, Facon T, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone versus reduced-dose bortezomib, thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction treatment before autologous stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;118 (22):5752–5758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosinol L, Oriol A, Teruel AI, et al. Superiority of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD) as induction pretransplantation therapy in multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 3 PETHEMA/GEM study. Blood. 2012;120(8):1589–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(10):895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beksac M, Hayden P. Upfront autologous transplantation still improving outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(2):e80–ee2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorsteinsdottir S, Dickman PW, Landgren O, et al. Dramatically improved survival in multiple myeloma patients in the recent decade: results from a Swedish population-based study. Haematologica. 2018;103(9): e412–e4e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristinsson SY, Anderson WF, Landgren O. Improved long-term survival in multiple myeloma up to the age of 80 years. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1346–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corre J, Perrot A, Hulin C, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma during the 2005–2009 and 2010–2014 periods. Leukemia. 2021;35(12):3600–3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langseth ØO, Myklebust T, Johannesen TB, Hjertner Ø, Waage A. Incidence and survival of multiple myeloma: a population-based study of 10 524 patients diagnosed 1982–2017. Br J Haematol. 2020;191(3):418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa LJ, Zhang MJ, Zhong X, et al. Trends in utilization and outcomes of autologous transplantation as early therapy for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(11):1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):e328–ee46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2012 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(1):78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone with transplantation for myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14): 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaballa MR, Ma J, Tanner MR, et al. Real-world long-term outcomes in multiple myeloma with VRD induction, Mel200-conditioned auto-HCT, and lenalidomide maintenance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022;63(3):710–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott EC, Hari P, Sharma M, et al. Post-transplant outcomes in high-risk compared with non-high-risk multiple myeloma: a CIBMTR analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(10):1893–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usmani SZ, Hoering A, Ailawadhi S, et al. Bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without elotuzumab in patients with untreated, high-risk multiple myeloma (SWOG-1211): primary analysis of a randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8(1):e45–e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durie BGM, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389 (10068):519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson PG, Jacobus SJ, Weller EA, et al. Triplet therapy, transplantation, and maintenance until progression in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):132–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonneveld P, Dimopoulos MA, Boccadoro M, et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024;390 (4):301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shustik C, Bergsagel DE, Pruzanski W. Kappa and lambda light chain disease: survival rates and clinical manifestations. Blood. 1976;48(1):41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alzahrani K, Pasvolsky O, Wang Z, et al. Impact of revised International Staging System 2 risk stratification on outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma receiving autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2024;204(5):1944–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(29):3279–3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panopoulou A, Cairns DA, Holroyd A, et al. Optimizing the value of lenalidomide maintenance by extended genetic profiling: an analysis of 556 patients in the myeloma XI trial. Blood. 2023;141(14):1666–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mateos MV, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, et al. Daratumumab plus bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):518–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2104–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giri S, Grimshaw A, Bal S, et al. Evaluation of daratumumab for the treatment of multiple myeloma in patients with high-risk cytogenetic factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(11):1759–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodríguez-Lobato LG, Pereira A, Fernández de Larrea C, et al. Real-world data on survival improvement in patients with multiple myeloma treated at a single institution over a 45-year period. Br J Haematol. 2022;196(3):649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swan D, Hayden PJ, Eikema DJ, et al. Trends in autologous stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: changing demographics and outcomes in European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation centres from 1995 to 2019. Br J Haematol. 2022;197(1):82–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ragon BK, Shah MV, D’Souza A, Estrada-Merly N, Gowda L, George G, et al. Impact of second primary malignancy post-autologous transplantation on outcomes of multiple myeloma: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood Adv. 2023;7(12):2746–2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasvolsky O, Milton DR, Masood A, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide maintenance after upfront autologous stem cell transplant for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: The MD Anderson experience. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(10):1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.