Abstract

Background:

Transition-related patient safety errors, are high among patients discharged from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and interventions are needed to improve communication between hospital and SNF providers. Our objective was to describe the implementation of a pilot telehealth videoconference program modeled after Extension for Community Health Outcomes-Care Transitions and examine patient safety errors and readmissions.

Methods:

A multidisciplinary telehealth videoconference program was implemented at two academic hospitals for patients discharged to participating SNFs. Process measures, patient safety errors, and hospital readmissions were evaluated retrospectively for patients discussed at weekly conferences between July 2019-January 2020. Results were mapped to the constructs of the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) model. Descriptive statistics were reported for the conference process measures, patient and index hospitalization characteristics, and patient safety errors. Primary clinical outcome was all-cause 30-day readmissions. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was conducted using logistic regression models fit to compare probability of 30-day hospital readmission in patients discharged to participating SNFs across seven months prior to after telehealth project implementation.

Results:

There were 263 patients (67% of eligible patients) discussed during 26 telehealth videoconferences. Mean discussion time per patient was 7.7 minutes and median prep time per patient was 24.2 minutes for the hospital pharmacist and 10.3 minutes for the hospital clinician. A total of 327 patient safety errors were uncovered, mostly related to communication (54%) and medications (43%). Differences in slopes (program period vs. pre-implementation) of probability of readmission across the two time periods were not statistically significant [OR 0.95, (95% CI 0.75, 1.19)].

Conclusions:

A pilot care innovations telehealth videoconference between hospital-based and SNF provider teams was successfully implemented within a large health system and enhanced care transitions by optimizing error-prone transitions. Future work is needed to understand process flow within nursing homes and impact on clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Care Transitions, Telehealth, Patient Safety, Interdisciplinary

BACKGROUND

The transition from hospital to post-acute care has high potential for errors, hospital readmission, and mortality.1,2 Prior studies indicate that a substantial proportion of readmissions remain preventable and are often due to poor care coordination and communication of critical information between hospital and SNF.3–7 Inadequate hospital discharge information and a high prevalence of medication discrepancies are significant barriers to the safety of care transitions.8–10 Interventions are needed that allow for systematic discussion of patients to facilitate effective and safe hand-offs of care from hospital to SNF. For example, the Health Optimization Program for Elders (HOPE) improved hospital-to-SNF transitions through pre-discharge transitions of care consultations by geriatric care specialists, and lowered 30-day readmission rates.11 However, such programs do not include a scalable system for weekly provider-to-provider discussion of transitional care pillars, such as medication reconciliation and optimization, laboratory follow-up needs, patient-specific disease management, and advance care planning.12

The opportunities within telehealth offer a novel solution by which hospital and SNF providers can improve communication and coordination of care. In 2013, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center adopted Project Extension for Community Health Outcomes (ECHO) to improve care transitions through weekly interdisciplinary videoconferences between hospital and SNF care teams and this resulted in a 43% lower odds of thirty-day readmission, a 5-day shorter length of stay in SNFs, and lower total cost of care for the intervention group.13,14 With support from an institutional innovations pilot award, we sought to apply the ECHO-Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model as a clinical innovation pilot within the Duke University Health System (DUHS) and chose the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) model as our foundational approach to evaluate its performance in improving transitions of care within a large health system.15 The RE-AIM is appropriate in this context because it suggests that translatability is best evaluated by the five dimensions of reach, effectiveness, adoptions, implementation, and maintenance. Using RE-AIM as a framework, we describe 1) implementation of a telehealth videoconference program and 2) examine patient safety errors and readmissions.

Design & Setting

This clinical innovation program intervenes on care transitions through a weekly telehealth videoconference between hospital and SNF providers. The participating hospitals included a 979-bed academic tertiary care hospital and a 369-bed academic community hospital.. The participating SNFs included one for-profit 140-bed facility and one not-for-profit 110-bed facility, each taking the majority of their post-acute admissions from the two participating hospitals. The Duke Health Institutional Review Board approved this project.

Program Participants

All adult patients discharged from the two hospitals to two participating pilot SNFs after their respective start dates were eligible for discussion in the weekly videoconferences. Initially the SNFs provided the patient list needed for preparation and teleconference discussion. However, the DUHS informatics team quickly developed and implemented an automated weekly report per hospital of all discharges to SNFs for this purpose.

Description of Telehealth Video Enhancement Conference Program

The program involved a secure weekly telehealth videoconference between hospital and SNF clinical teams. The multidisciplinary hospital-based team included a hospitalist (2 physicians and one physician assistant rotating), two hospital clinical pharmacists (one for each hospital), a geriatrics fellow, a case manager, and a geriatrics nurse practitioner. Members of the care team from each SNF varied slightly between SNFs, but included a clinical representative, the director of nursing or advanced practice provider, and discharge representative, such as social worker or navigator, and an administrator. Prior to the conference, the participating SNFs securely shared the medication administration record (MAR) and physician orders for each patient with the hospital clinical team and completed a structured intake form to specify concerns or issues during the transition from hospital to SNF, as well as any new challenges for the patient since SNF admission. Prior to the conference, the lead hospital clinician (one of the three team hospitalists) reviewed the medical chart of each patient, including the recent hospitalization and SNF intake form. Of note, the lead hospital clinician was rarely part of the original inpatient treatment team for the patients discussed. The hospital clinical pharmacists reconciled each patient’s home medication list, hospital discharge medication list, and SNF MAR, identified medication errors, and assembled recommendations for medication optimization prior to the conference each week. Each SNF was allotted a total of 0.5 to 1.5 hours for the weekly conference. Each weekly conference was led by the hospital clinician who oversaw discussion of transitional care pillars and invited the pharmacists and SNF team members to address their respective findings for each patient. Patient safety errors identified during the transition from hospital to SNF, such as medication errors or a code status discrepancy, were recorded by a hospital team member within secure internal team documentation.

Unlike the original ECHO model described for Hepatitis C, this format did not include formal didactics or provide continuing education credits. It closely mirrored the ECHO-CT model in respect to team composition, format, time allotted and focus on transitional care pillars.13, 14 Each patient was discussed only once. Discharge coordinators, hospital staff, and patients/families were not informed about the pilot project so as to avoid any impact on referral rates. Neither facility attempted to use this as a recruitment tool.

Implementation Strategy

The implementation strategy involved several steps. First, we identified the participating SNF sites and participating staff at the hospitals and SNFs. Organized by the hospitalist leader, all identified staff were engaged through meetings and communications in a 3 month preparatory phase, 6 month implementation phase, 3 month analysis phase while the pilot continued. Second, we trained hospital staff on how to perform case reviews and how to track process measures and safety errors. Third, a start date was identified for each SNF participant. To overcome early barriers (e.g. video-technology, prep-time), we opted for a phased approach to onboarding the SNFs and ramping up collection of measures over time. Simultaneously, the hospital team gave attention to collecting and incorporating feedback from team members and participating SNFs through intentional solicitation and routine debriefs after each conference. Fourth, we selected methods and frequency of tracking process measures (e.g. REDCap database, weekly collection), as well as assigned team members to facilitate documentation of measures. From program inception, we engaged two health system sponsors, the leader of population health and the president of one of the hospitals, which facilitated open communication regarding future health system support of the program beyond the pilot phase.

Program Measures

Process Measures:

The conference process measures included the number and duration of telehealth videoconferences, number of hospital and SNF personnel on the conferences, and the self-reported amount of preparation time required by the hospital pharmacist and clinician. These measures were manually recorded by team members during the conferences. SNF-level process measures were not collected to keep administrative burdens on the participating SNFs to a minimum.

Patient Characteristics:

We examined age, gender, race, case mix index (CMI), hospital length of stay (LOS), and readmission risk score at time of hospital discharge. The CMI is the average of the Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group weight for each discharge and reflects clinical complexity and resource needs.16 A higher CMI indicates increased complexity and resource needs. The readmission risk score is an internally developed continuous measure to predict 30-day hospital readmission that incorporates metrics such as demographics, comorbidities, patient level health data, and care utilization, including hospital length of stay and emergency department (ED) visits.17 We also captured time between discharge and telehealth videoconference. Demographic data and patient level factors were captured via automated abstraction from the Electronic Health Record (EHR).

Patient Safety Errors:

The patient safety errors were identified either during pre-conference preparation work or during the video telehealth conference meetings in conversations between the hospital team and SNF teams. The operational definitions for these patient safety errors were based on work from Moore and colleagues who examined types of medical errors associated with care transitions, as well as the Coleman transitions of care pillars.18, 19 Two independent investigators present during the videoconferences cataloged patient safety errors and subsequently subcategorized them into medication-related errors (e.g. missing stop dates, duplicative therapy, incorrect renal dosing), durable medical equipment errors (e.g. incomplete or absent directions for use), or communication errors (e.g. code status discrepancy, missing referral information, or unclear catheter instructions). Medication error classification categories were determined through literature review and vetted by clinical pharmacists not included in data collection or the intervention. Medication errors were identified through the review of a comparison of the SNF MAR and the hospital discharge to outside facility form. Errors that fell into two categories, such as an antibiotic without a stop date, were classified as both a medication error as well as a communication error.

Clinical Outcomes:

The primary clinical outcome was all-cause 30-day readmissions to any hospital in DUHS. Readmissions were calculated from the date of hospital discharge and were queried within the EHR based on the index hospitalization. Death date within 30 days of hospital discharge was similarly abstracted from the EHR to calculate a 30-day readmission and mortality composite event.

Statistical Methods

Sample:

The sample for program evaluation consisted of patients discharged from the DUHS hospitals to participating SNFs during the pilot program windows. An original EHR data abstraction included all patients discharged from the participating hospitals to any SNF between January 1, 2018 and January 31, 2020 (N=9,759). Only patients discharged to one of the two participating facilities were included in the evaluation sample (n=1129). The evaluation period included July 1, 2019 to January 31, 2020 for SNF A and August 27, 2019 to January 31, 2020 for SNF B, resulting in a final sample size of 391 patients who were eligible to receive the telehealth videoconference program during these periods. A historic comparison cohort of patients who did not receive the program included patients discharged from DUHS to the participating SNFs during the same timeframe of the previous year, resulting in a final sample size of 676 for the 30-day mortality outcome (285 in the prior year and 391 post intervention implementation). Model-specific exclusions were made to ensure 30-day follow-up time was available for hospital readmissions (N=645), analysis of the composite 30-day readmission-mortality outcome used all available discharges (N=676).

Analysis:

Descriptive statistics were performed for the conference process measures, patient and index hospitalization characteristics, and patient safety errors. Using an intent to treat (ITT) approach, thirty-day hospital readmission and composite 30-day hospital readmission and death rates were modeled with logistic regression. Models included hospital discharges from individuals discharged to participating SNFs during July 2018-January 2019 (prior to implementation of the telehealth program) and from July 2019-January 2020. Logistic regression models were fit to compare probability of readmission across seven months prior to telehealth project implementation to that across seven months during the project. The trends were modeled using a linear trend over time (in the logit scale): one line for the pre-implementation period (months 1 to 7), and a different line during implementation (months 13–19). The two time periods were compared by statistically testing for differences in slopes and intercepts of the linear trends. Adjusted versions of the models accounted for hospital length of stay, age, sex, race, CMI weight, and a readmission risk score. The statistics were generated using SAS/STAT software (SAS Institute Inc. 2020. SAS/STAT® 15.2 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.).

We used the RE-AIM model to organize the results by the major dimensions of translatability; reach and effectiveness as individual levels of program impact, and adoption, implementation, and maintenance as organizational levels of program impact. The evaluation of implementation and maintenance are based on investigator perspectives and results are qualitatively described. Definitions used to evaluate each of the five RE-AIM measures are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

RE-AIM Measure Definitions

| Used Definition | |

|---|---|

| Reach | Number of patients with completed telehealth videoconferences out of all who were eligible |

| Effectiveness | Patient safety error identification and impact on clinical outcomes of readmissions and mortality |

| Adoption | Hospital and SNF1 staff participation and process measures of conference time and preparation time |

| Implementation | Key elements of intervention delivery |

| Maintenance | Barriers identified |

SNF=Skilled Nursing Facility

RESULTS

Reach

There were 676 total patient cases included in the evaluation, 285 in the historical period, and 391 in the intervention period. The patient and index hospitalization characteristics by implementation period (historic and intervention) are detailed in Table 2. The overall median age was 78 years, 58% were female, 42% were non-white, and the median hospital LOS was 6.7 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient and Index Hospitalization Characteristics

| Historic Group (N=285) | Telehealth ITT Group (N=391) | Total (N=676) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telehealth Discussion Occurred | |||

| Yes | N/A | 263 (67%) | N/A |

| Days Between Discharge and Telehealth Discussion | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | N/A | 6 (5,8) | N/A |

| Age at Discharge | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 78 (70, 85) | 78 (70, 86) | 78 (70, 85) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 163 (57%) | 232 (59%) | 395 (58%) |

| Male | 122 (43%) | 159 (41%) | 281 (42%) |

| Race | |||

| Non-White1 | 125 (44%) | 161 (41%) | 286 (42%) |

| White | 160 (56%) | 230 (59%) | 390 (58%) |

| Hospital Length of Stay | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 6.9 (4.5, 10.1) | 6.7 (4.6, 10.1) | 6.7 (4.5, 10.1) |

| CMI | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.9 (1.0, 2.3) | 1.7 (1.0, 2.1) |

| Discharge Readmission Risk Score | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 18 (14, 25) | 18 (13, 24) | 18 (14, 25) |

| Discharge Readmission Risk Level | |||

| Low | 131 (46%) | 193 (49%) | 324 (48%) |

| Medium | 92 (32%) | 122 (31%) | 214 (32%) |

| High | 62 (22%) | 76 (19%) | 138 (20%) |

Non-white includes any response that was not White/Caucasian. Including Black/African American, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, or multiple race responses.

There were 26 weekly conferences held across two participating SNFs between July 2019 and January 2020. There were 391 total patient cases included in the evaluation. Within the telehealth videoconference evaluation group, 263 out of 391 (67%) cases were discussed on the videoconferences. Due to the nature of holding only one conference per week, some patients were discharged, died or readmitted from the SNF before the conference call took place. Additionally, patients were missed when conferences were cancelled due to holidays or active federal/state surveys that precluded participation. The median time from hospital discharge to conference call discussion with the SNF was 6 days (IQR 5, 8).

Effectiveness

Patient Safety Errors

A total of 327 errors were identified during the transition from hospital to SNF, with the most common being categorized as medication and communication. Of the 327 errors uncovered, 54% (177) were related to communication, 43% (139) to medications, and 3% (11) to DME. Of the communication errors, 68% (121) were related to medication, 6% (10) to DME equipment, and 26% (46) were exclusively communication errors. These errors resulted in cascades of smaller Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles20 executed through existing safety reporting and quality improvement infrastructure. For example, we commonly encountered missing antibiotic stop dates and missing Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Machine settings on discharge paperwork. We clarified the missing information for these individual patients, and then improved our system’s discharge to outside facility form to require antibiotic end dates and automatically import CPAP settings.

Clinical Outcomes

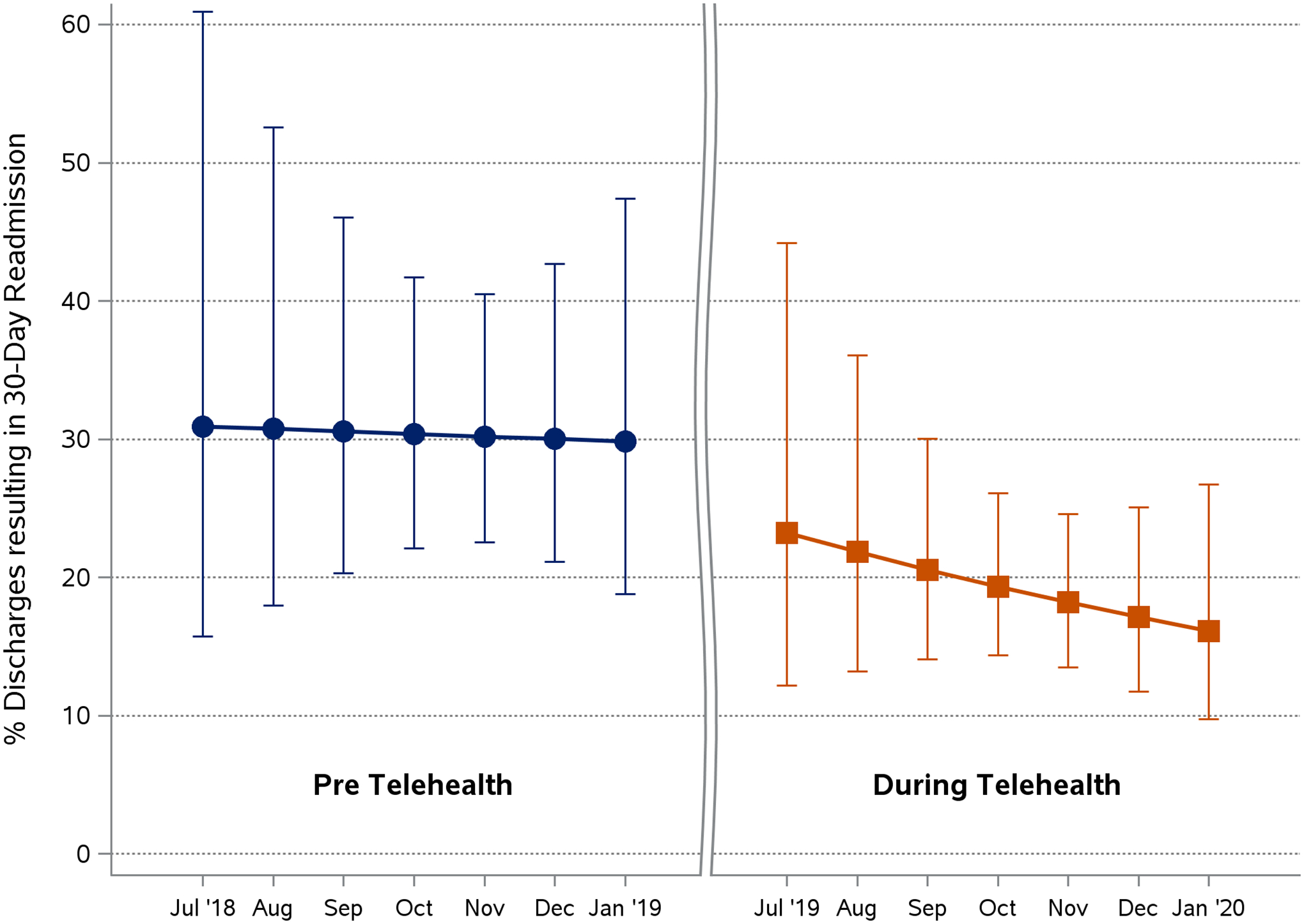

The rates of readmission varied between 0 and 35.3 over the observed time period (Supplemental Table S1). In the period one year prior to the telehealth interventions implementation, the expected odds of hospital readmission were 1% lower than the odds of readmission the month prior [OR 0.99 (95% CI 0.85, 1.17)], given observed covariates. After implementation of the intervention, the expected odds of hospital readmission were 6% lower than the odds of readmission in the month prior [OR .94, (95% CI 0.80, 1.11)]. The difference in slopes (pre-Telehealth vs. during Telehealth) was not statistically significant [OR 0.95, (95% CI 0.75, 1.19)] (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table S2). These findings suggest that there may have been a slight, though insignificant, reduction in the probability of 30-day hospital readmission across both time periods, but the trend was not altered in a statistically meaningful way after implementation of the telehealth program. Conclusions were consistent with and without covariate adjustment and in the models using a composite 30-day and mortality outcome (Supplemental Table S3).

Figure 1.

Discharges Resulting in 30-day Readmissions

Adoption

Median discussion time per patient was 7.7 minutes (IQR 6.5, 8.6). Median prep time per patient for the weekly conferences for the hospital clinical pharmacist was 24.2 minutes (IQR 19.1, 27.6) and 10.3 minutes (IQR 6.2, 12.9) for the hospital clinician (Table 3). We experienced sustained engagement of both hospital (mean 6 participants) and SNF personnel (mean 4 participants per SNF) over the 7-month pilot (Table 3). We anticipated a need for assistance with hardware and internet access but found both of our SNF participants were equipped with a private conference room including video capabilities and internet access.

Table 3.

Conference Characteristics

| July 2019 – January 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Conferences | 26 |

| Number of patients discussed | 263 |

| Discussion time per patient, median (IQR1) (min) | 7.7 (6.5, 8.6) |

| Hospital personnel, mean (SD2) | 6 (1.6) |

| SNF personnel, mean (SD) | 4 (1.6) |

| Pharmacy prep time per patient, median (IQR) (min)3 | 24.2 (19.1, 27.6) |

| Clinician prep time per patient, median (IQR) (min)3 | 10.3 (6.2, 12.9) |

IQR=Interquartile Range

SD=Standard Deviation

Data from subset of 18 conferences

Implementation

There were several programmatic elements that were key to the delivery of the intervention. First, by scheduling video communication our intervention mitigated many of the barriers to provider communication across care settings such as lack of interoperable EHRs and difficulty contacting providers across systems. Second, medication reconciliation and optimization played an important role in identifying patient safety errors during the conferences, which provided improvements in standardizing discharge information communication. Third, as relationships were firmly established towards the end of the pilot phase, SNFs gave the hospital pharmacists read-only access to their EMRs which mitigated the need to upload copies of medication administration records to the hospital team prior to the weekly meeting, thus eliminating administrative burden. Lastly, health system informatics, data science, and implementation teams were leveraged to improve program efficiency and sustainability. Using real-time data dashboards, our team developed a more streamlined process to identify hospital patients discharged to SNFs prior to the conferences that mitigated the need for SNFs to send a list of admissions, as well as to track patient outcomes and demonstrate program value to stakeholders.

Maintenance

The resources required of SNFs to fully participate in the program, such as dedicated time and personnel, were constantly being evaluated to optimize participation and opportunities for expansion. For example, because it was difficult to discuss patients who had just arrived when SNF staff had not yet finished their assessments, we transitioned from discussing patients admitted 1–8 days out from the meeting to 3–10 days out. With this change, the SNF intake form was not necessary since those participating in the SNF teleconference team came with information they collected in their normal workflow. Removing this requirement decreased SNF preparation time for the teleconference and has not fundamentally altered information exchange. At the end of the internal innovation support, leadership within the Duke population health and accountable care structure agreed to support the program going forward with plans to include a third SNF, continue monitoring outcomes, and assess opportunities for further refinement and expansion.

CONCLUSIONS

Discussion

A weekly multidisciplinary telehealth videoconference to transition patients from hospital to SNF was adopted with sustained engagement from both hospital and SNF personnel. The hospital team was able to conduct weekly videoconferences with two community SNFs, perform medication reconciliation and optimization, and discuss medical follow-up needs. Our findings corroborate with published evidence from the ECHO-CT model, and we uniquely apply the RE-AIM framework to explore the factors that influence translatability of this model to clinical practice. Whereas, we did not show a statistically significant difference in readmission probability across time periods, and a larger sample is likely need to show positive change, our evaluation of this pilot program demonstrates the value in other ways of a telehealth care transitions program within both the hospital and post-acute care setting.

Our identification of patient safety errors demonstrates the common occurrence of communication and medication-related errors in the transition from hospital to SNF and provides opportunities for system-wide care transition improvement strategies. We replicated findings from ECHO-CT that the majority of transitions safety events identified are communication and medication issues.21 Some of the common safety errors we identified resulted in cascades of PDSA cycles, that produced systems level improvements.20 While not included in our data collection and analysis, we hypothesize that medication reconciliation and optimization may have preemptively identified discrepancies and reduced the potential for adverse drug events that may lead to readmission, while systematic discussion of each patient may have uncovered pertinent follow-up needs or goals of care that decreased the need for rapid transfers back to the hospital.22,23 Telehealth videoconferences provide systematic opportunities for identifying and managing transition-related patient safety errors. These errors are important targets for system wide care transition improvement strategies and further enhance the value of this program for the hospitals and health system beyond the individual patients discussed each week. Finally, the expertise gained about care transitions by the hospitalist and pharmacist leaders involved in the program may be shared with peers and also contribute to system-wide transition improvements.

Organizational adoption of the program required time and effort from the clinicians and pharmacists to both prepare for and conduct the conferences which represents a cost to the health system; the ECHO-CT program demonstrated the opportunity for significant healthcare cost savings in terms of Medicare spending.14 Similarly, for SNFs, whereas there were several barriers to implementation of our program, the benefits of participation may include improved quality measures, which have become increasingly important metrics by which the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services evaluate and determine payment to SNFs,24 and future work on cost-savings to SNFs is warranted Further, our organizational adoption centered not only on readmission avoidance but also on building relationships that support other transitions and additional SNF utilization through 3-day waiver opportunities. This would allow patients to avoid hospital cost when not needed and move more seamlessly from emergency department and outpatient settings directly to post-acute care. Also, we found that many individuals discharged to SNF reflected a low level of rehabilitation potential.25 This led to discussions around the importance of continued palliative discussions and use of consultative referrals which were available at both SNFs. After the pilot program’s completion, our system’s discharge to outside facility form was further enhanced to include recent medical notes regarding advance directives so that SNF providers could more easily continue these discussions with patients and families.

The key programmatic elements critical to the successful implementation of this program in the “real-world” setting were 1) enhanced communication between settings using a videoconference platform, 2) identification of patient safety errors during conference sessions that result in opportunities for intervention at both the patient level and the systems level within the hospitals, and 3) use of real-time dashboards to identify eligible patients and track program outcomes. Inclusion of these elements as targets for system-wide care transition improvement strategies may help ensure large potential impact across other health systems choosing to implement such a program.

There are several limitations to our program implementation. First, the single site may limit generalizability. Second, only a portion of the eligible patients were discussed in the videoconferences and only two SNFs were engaged. However, the resulting institutional system level improvements in transitions of care may generalize to non-discuss patients, and thus benefit patients not directly targeted by our program. Third, our analysis did not include SNF-level data, such as SNF characteristics, process measures, length of stay, or 30-day readmission rates after SNF discharge, which are important metrics for assessing program value and promoting SNF participation in the future. Fourth, though identification and assessment of patient safety errors was conducted in a standardized way, a blinded adjudication of errors was not performed..

Conclusion

Our video telehealth transitions enhancement conference provides an example of translatability and implementation of the ECHO-CT model within a large health system. Effective stakeholder engagement within a health system and across care settings is essential for program sustainability. Future implementation work should include evaluating methods for further program expansion, measurement of program financial impact, and the patients and facilities most likely to benefit from systematic enhancements in care transitions.

Supplementary Material

Impact Statement:

We certify that this work is confirmatory of recent novel clinical research of weekly interdisciplinary videoconferences between hospital and skilled nursing facility care teams.13,14 However, our pilot program takes this model outside of a traditional research design and evaluates its performance in improving transitions of care within a large academic health system. Further our work extends the original findings by evaluating the care transition patient safety errors identified during videoconferences.

Key Points.

Telehealth videoconferencing uncovers safety errors for hospital to skilled nursing facility (SNF) transitions.

Identified patient safety errors may enhance system-wide care transitions

Why does this matter?

Transitions telehealth videoconferences are feasible and can identify patient safety errors.

Funding:

This work was supported and funded by the Duke Institute for Health Innovation (DIHI) through the DIHI Innovation Pilots RFA 2019 program;. The Duke BERD Method Core(UL1TR002553.); Duke Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (NIA P30 AG028716-01).

Sponsor’s Role

This work was supported and funded by the Duke Institute for Health Innovation (DIHI) through the DIHI Innovation Pilots RFA 2019 program; The Duke BERD Method Core(UL1TR002553); the Duke Telehealth Office, Duke Population Health Management Office; and the Duke Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30-AG028716). Additional clinical leadership was provided by Rachel Hughes, MD and Elisabeth Kidd, PA-C. David Ming, MD provided expertise through manuscript editing and feedback.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D et al. Hospital readmission from post-acute care facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Skilled Nursing Facility 30-Day All-Cause Readmission Measure (SNFRM) NQF #2510: All-Cause Risk-Standardized Readmission Measure Technical Report Supplement—2019 Update. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/SNF-VBP/Downloads/SNFRM-TechReportSupp-2019-.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed February 2020.

- 3.Ouslander JG, Diaz S, Hain D, Tappen R. Frequency and Diagnoses Associated With 7-and 30-Day Readmission of Skilled Nursing Facility Patients to a Nonteaching Community Hospital. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(3):195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasilevskis EE, Ouslander JG, Mixon AS et al. Potentially avoidable readmissions of patients discharged to post-acute care: perspectives of hospital and skilled nursing facility staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(2):269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dusek B, Pearce N, Harripaul A, Lloyd M. Care transitions: a systematic review of best practices. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(3):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton MC, Ouellet GM, Minges KE, Gawel M, Hodshon B, Chaudhry SI. Care transitions between hospitals and skilled nursing facilities: perspectives of sending and receiving providers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(11):565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark B, Baron K, Tynan-McKiernan K et al. Perspectives of clinicians at skilled nursing facilities on 30-day hospital readmissions: a qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King BJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, Polnaszek BE, Bowers BJ, Kind AJ. The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: a qualitative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1095–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, McGee S, Terrill E, Miller K. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):630–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jusela C, Struble L, Gallagher NA et al. Communication between acute care hospitals and skilled nursing facilities during care transitions a retrospective chart review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2017;43:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krol ML, Allen C, Matters L, Jolly Graham A, English W, White HK. Health Optimization Program for Elders: Improving the Transition From Hospital to Skilled Nursing Facility. J Nurs Care Qual. 2019;34(3):217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S. The Care Transitions Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes—care transitions: Enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health, 1999;89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Case Mix Index.” CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Acute-Inpatient-Files-for-Download-Items/CMS022630

- 17.Gallagher D, Zhao C, Brucker A, et al. Implementation and Continuous Monitoring of an Electronic Health Record Embedded Readmissions Clinical Decision Support Tool. J Personalized Med. 2020;10(3): 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S. The Care Transitions Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2021. “How to Improve.” IHI.org. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementTestingChanges.aspx

- 21.Gonzalez MR, Junge-Maughan L, Lipsitz LA, Moore A. ECHO-CT: An Interdisciplinary Videoconference Model for Identifying Potential Postdischarge Transition-of-Care Events. J Hosp Med. 2021. Feb;16(2):93–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilcup M, Schultz D, Carlson J, Wilson B. Postdischarge pharmacist medication reconciliation: impact on readmission rates and financial savings. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2013;53(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaMantia MA, Scheunemann LP, Viera AJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Hanson LC. Interventions to improve transitional care between nursing homes and hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2019. “Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing Program Updated.” CMS.gov. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/SE18003.pdf

- 25.Flint LA, David DJ, Smith AK. Rehabbed to Death. N Engl J Med. 2019. Jan 31;380(5):408–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.