Abstract

Quantitative Taq nuclease assays (TNAs) (TaqMan PCR), nested PCR in combination with denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), and epifluorescence microscopy were used to analyze the autotrophic picoplankton (APP) of Lake Constance. Microscopic analysis revealed dominance of phycoerythrin (PE)-rich Synechococcus spp. in the pelagic zone of this lake. Cells passing a 3-μm-pore-size filter were collected during the growth period of the years 1999 and 2000. The diversity of PE-rich Synechococcus spp. was examined using DGGE to analyze GC-clamped amplicons of a noncoding section of the 16S-23S intergenic spacer in the ribosomal operon. In both years, genotypes represented by three closely related PE-rich Synechococcus strains of our culture collection dominated the population, while other isolates were traced sporadically or were not detected in their original habitat by this method. For TNAs, primer-probe combinations for two taxonomic levels were used, one to quantify genomes of all known Synechococcus-type cyanobacteria in the APP of Lake Constance and one to enumerate genomes of a single ecotype represented by the PE-rich isolate Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807. During the growth period, genome numbers of known Synechococcus spp. varied by 2 orders of magnitude (2.9 × 103 to 3.1 × 105 genomes per ml). The ecotype Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 was detected in every sample at concentrations between 1.6 × 101 and 1.3 × 104 genomes per ml, contributing 0.02 to 5.7% of the quantified cyanobacterial picoplankton. Although the quantitative approach taken in this study has disclosed several shortcomings in the sampling and detection methods, this study demonstrated for the first time the extensive internal dynamics that lie beneath the seemingly arbitrary variations of a population of microbial photoautotrophs in the pelagic habitat.

In oligo- and mesotrophic lakes the autotrophic picoplankton (APP) can contribute up to 65% of the primary production (41). However, abundance and depth distribution of APP are highly variable. Large intra- and interannual fluctuations of cell numbers characterize the depth-integrated APP profiles of Lake Constance, a deep mesotrophic, monomictic lake of glacial origin (10). After a decade of monitoring, a pattern emerged in the seasonal development of the APP. The abundance is low throughout winter until lake stratification initiates the development of a spring population, in some years rising to impressive spring maxima. The spring population collapses during the clear-water phase, and low abundances prevail during most of the summer. A second maximum develops usually in late summer and disappears again in September or October (10). The factors causing the sharp fluctuations in the population after the initial spring bloom are not known, but grazing (31) and also loss due to viral lysis (37) may limit the size of the populations during the summer period.

The APP of Lake Constance is dominated by phycoerythrin (PE)-rich Synechococcus spp., whereas phycocyanin (PC)-rich species and eukaryotic algae represent less than 5% of the pelagic community (10). Between 1988 and 1994, we isolated 26 PE- and PC-rich Synechococcus strains from the pelagic zone. Molecular fingerprinting by restriction fragment length polymorphism of psbA genes revealed 12 unique genotypes (29). 16S rRNA sequence-inferred phylogenetic analysis identified all Synechococcus spp. isolated from Lake Constance as members of three lineages of the picophytoplankton clade sensu Urbach et al. (36), which also comprises marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus spp. (A. Ernst, S. Becker, U. Wollenzien, and C. Postius, submitted for publication).

The 12 pelagic Synechococcus isolates from Lake Constance differed in pigmentation, surface structures, and physiological characteristics potentially influencing growth rates as well as trophic interactions (for a review, see reference 29). Differences in pigmentation and photosynthetic performance were also described for isolates of the phylogenetically related, marine Prochlorococcus spp. (22). Different genotypes of this population had been traced by fluorescence in situ hybridization targeting the 16S rRNA in combination with light microscopy or flow cytometry (42, 44). The depth-dependent distribution of genotypes confirmed the hypothesis deduced from physiological studies that they represent ecotypes adapted to different environmental conditions (8, 22, 36, 42). Based on the characteristics of a freshwater ecosystem, we had proposed that different ecotypes form subpopulations, which occur successively throughout the year (5). The succession of subpopulations could be driven by seasonal changes in the biotic and abiotic environment, as described for the succession of algae in spring, summer, and autumn populations (33). Alternatively, the subpopulations of the pelagic Synechococcus populations could exhibit a chaotic behavior in time as proposed by Huisman and Weissing (14) for mixed populations of algae.

To get insights into the internal dynamics of the freshwater APP, we wanted to trace ecophysiologically distinct, isolated strains in their natural environment. However, a low plating efficiency, the lack of morphological differences (7), and the close phylogenetic relation of these isolates (Ernst et al., submitted) precluded the in situ study of ecotype dynamics by traditional or modern methods (e.g., fluorescence in situ hybridization).

PE-rich Synechococcus spp. isolated from the APP of Lake Constance exhibit a sequence divergence of 0 to 8 nucleotides in 1,456 nucleotides of the 16S rRNA, with four clustered mutations that were not specific for the lineage (Ernst et al., submitted). However, as with many members of the picophytoplankton clade, they possess a long and highly variable internal transcribed spacer (ITS-1) separating 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and 23S rDNA, which reflects the phylogenetic relations inferred from 16S rRNA sequences (17; Ernst et al., submitted). Therefore, we chose target sequences in the ITS-1 to trace the isolated Synechococcus strains in their natural habitat.

Unlike structural components of the ribosomal operon, the noncoding sections of the ribosomal ITS do not accumulate in cells. Hence, for the detection of different organisms, the ITS-1 has to be amplified by PCR. In this study, the PCR products were quantified directly in a Taq nuclease assay (TNA) or analyzed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). The latter method allows homologous PCR products to be distinguished on the basis of their melting behavior in a gradient of denaturants. As little as one base difference in the sequence can be sufficient to distinguish two amplicons of the same length (9). This technique has a high resolution and is now frequently used to demonstrate shifts in the genetic diversity of microbial communities (26), but quantitative aspects, which are frequently implicated in the interpretation of DGGE data, have been questioned. PCR is a nonlinear reaction in which small differences in the amplification efficiency and competitive effects between primer and amplicons can lead to a significant bias within and between reactions (3, 21, 24, 35, 38, 40). Quantification by PCR conducted over a fixed number of cycles requires analysis of serially diluted samples to which endogenous amplification standards have been added (32).

Alternatively, PCR-based quantification can be achieved by real-time PCR technology, in which the accumulation of the PCR product or the activity of Taq polymerase are continuously monitored by fluorescent labels. A particular form of real-time PCR is the TNA, also called a 5′ nuclease assay or TaqMan PCR. In TNA, the activity of Taq polymerase is monitored by the hydrolysis of an oligonucleotide probe (TaqMan probe) labeled with two fluorescent dyes (18, 19). In the intact probes, the fluorescence of 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM), acting as a reporter, is diminished by a quencher, 6-carboxy-tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). If this probe binds to a complementary target sequence during the annealing phase of PCR, the probe becomes hydrolyzed by the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of Taq polymerase (13). The release of the reporter during each round of amplification allows for rapid detection and quantification of target DNA without the need for post-PCR processing (18, 19). The reaction is calibrated by establishing a correlation between the concentration of target sequences (number of genomes) in the assay prior to amplification and the cycle at which fluorescence reaches a threshold value, the threshold cycle (11). Real-time PCR allows control of the amplification efficiency in every reaction and absolute determination of templates in an assay (3). As DGGE and TNA are not bound to particular genes or gene products, the application of these techniques can be tailored to the phylogenetic level at which microbial abundance and diversity are studied.

For the analysis of the Synechococcus-type cyanobacteria in the APP of Lake Constance, several PCR assays with different specificities were developed. For analysis of the genetic diversity in a lineage of PE-rich Synechococcus spp., a fragment of the ITS-1 was amplified by nested PCR and analyzed with DGGE. For quantitative PCR, two different primer pairs and TaqMan probes were used. One assay was designed to quantify all known (isolated) Synechococcus strains and all strains present in the environment that share target sequences for primers and probe in conserved sections in the ITS-1 with these isolates. A second TNA was designed for the specific detection of cells that share primer and probe sequences with a single isolated ecotype, Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 (3). Cultured PE-rich strain BO 8807 is distinguished from the seven closest related PE-rich isolates by a rod-shaped morphology with a longitudinal axis of 4.42 ± 2.62 μm (7), a highly glycosylated S-layer (6), and a lowered clearance rate in predation experiments with a chrysomonade and a nanoflagellate (1, 25). The feasibility of DGGE and TNA in tracing a particular ecotype in a natural population consisting of numerous closely related organisms and unknown diversity is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and culture conditions.

Synechococcus spp. (strains BO 8807, BO 8808, BO 8809, BO 9101, BO 9402, BO 9403, and BO 9404) were isolated from the pelagic zone of Lake Constance (Bodensee) (4, 30) and were cultured in 40 ml of the mineral liquid medium BG11 (34) under low light intensity between 5 and 10 microeinsteins m−2 s−1.

Sampling.

Every 2 or 3 weeks 10 liters of a mixed water sample (integration over 0 to 8 m depth) was collected at a fixed sampling site in the northwestern part (Überlinger See) of Lake Constance. Additionally, surface water (0-m depth) was collected from the pelagic and the littoral zone at the fixed sampling site near the maximum depth of Überlinger See and above a water column of 5 m, respectively. After a first filtration step through a 30-μm mesh, the water was filtered under low vacuum (0.3 × 105 Pa) through a 3-μm filter (cellulose), which was changed after filtration of 2 liters to avoid clogging of the filter. For the collection of picoplankton, 0.15-μm filters (cellulose acetate, 47-mm diameter) were used and stored at −20°C until DNA extraction. Filters were received from Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany.

Epifluorescence microscopy.

For cell counts of cyanobacterial picoplankton, water samples from Überlinger See or cultures of unialgal Synechococcus spp. were fixed with formalin (final concentration, 0.2% [vol/vol]) and concentrated under vacuum on black polycarbonate filters with a 0.2-μm pore size (Nuclepore, Tübingen, Germany). To achieve equal distribution of cells on filters, a second cellulose nitrate filter (0.45-μm pore size; Nuclepore) was placed beneath the filter for concentration of cells. Using a Labophot-2 microscope (Nikon) equipped with a 100/1.25 oil objective and an interference filter combination BA 590, the cell number of all single-cell coccoid cyanobacteria was determined, whereby colony-forming cells were excluded. No eukaryotic picoplankton was detected, since staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and excitation with filter BA 450 showed no presence of eukaryotic cells. Samples were analyzed in triplicate, and from each filter the cells of 10 different areas were counted.

Isolation of DNA.

DNA from cultivated strains was obtained by a phenol-chloroform extraction method described previously (3). The concentration and purity of genomic DNA was determined by measuring the absorption ratio A260/A280. For the estimation of genome copy numbers for pelagic Synechococcus spp., a genome size of 3 Mbp was assumed. Using an approximate molecular mass for a base pair of 650 Da, 1 ng of genomic DNA represented 3 × 105 copies of Synechococcus spp. genomes. For DNA extraction, filters with cells were cut in 16 equal pieces along lines imprinted by the filter support (Nalgene, Braunschweig, Germany) during the filtration process. Pieces were incubated with 400 μl of 5% (wt/vol) Chelex-100 (sodium form; 100 to 200 mesh; Bio-Rad, München, Germany) in a reaction tube for 30 min at 100°C and shaken several times while boiling (modified after reference 39). After vortexing at high speed for 10 s and centrifugation for 2 min, the supernatant was used as template in TNAs or in conventional PCR. From each filter the DNA of three different pieces was extracted and analyzed in duplicate.

DGGE.

For analysis of environmental samples with DGGE, PCR products were amplified in two successive PCRs, conducted as a nested PCR. In 25-μl volumes, 2 μl of supernatant of Chelex-100 extraction from filter pieces (see above) was mixed with 200 nM concentrations of the primers PITSANF and PITSEND (from MWG, Ebersberg, Germany, or Interactiva, Ulm, Germany), 2.5 mM Mg2+, 2.5 μl of 10× reaction buffer, and 0.625 U of Taq polymerase from Qiagen, Hilden, Germany. The PCR was conducted in a PTC-100 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc.) using a two-step cycling program as follows: after an initial denaturation at 95°C (3 min), the program comprised 30 cycles of a 2.5-min annealing-extension step at 60°C and a denaturation step (40 s) at 94°C. The reaction was terminated with a final polymerization step at 70°C for 5 min. For the second reaction, 2 μl of the first assay mixture was used as a template in 50-μl-volume assays for amplification. The reaction mixtures contained primers PITSGCANF and PITSGC (Table 1 and Fig. 1; from Interactiva or Genaxis, Spechbach, Germany) and other components as described above, and the PCR was performed after an initial incubation of 3 min at 95°C as follows: 35 cycles of 1.5 min at 65°C for annealing-polymerization and 30 s at 94°C for denaturation. The reactions were terminated with a final step at 70°C for 5 min. DGGE markers were generated by amplification of 10 ng of genomic DNA from isolated Synechococcus strains in a single reaction, using the primers PITSGCANF and PITSGC to produce GC-clamped fragments.

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Primer (P) or probe (S) | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Tm (°C)b |

|---|---|---|

| P8807AP | CATTCTTGACAAGTTAACCAGTTAGCTG | 57 |

| P8807AM | CAAGGTTCTGCTGACATTCAAACA | 57 |

| P100PA | GGTTTAGCTCAGTTGGTAGAGCGC | 58 |

| P3 | TTGGATGGAGGTTAGCGGACT | 56 |

| PITSANF | CGTAACAAGGTAGCCGTAC | 46 |

| PITSEND | CTCTGTGTGCCAAGGTATC | 45 |

| PITSGCANF | GTGATGTCTGAGTAATTTATTCTCAGGC | 56 |

| PITSGCc | GCCGCGCCCGCCGGCCGCCCGCGCGCCC GCCGCCGCGCCCGCCGCCGCCCGGCGG AATTATAAATATAGGAGCTCTCGCCGCAAC | 86d |

| S8807A | R-TCTCCAGGGCAGCATTGAATCCAG-Q | 64 |

| S100A | R-CTTTGCAAGCAGGATGTCAGCGGTT-Q | 65 |

The localization of the fluorescent dyes of the probes are indicated with R (reporter [FAM]) and Q (quencher [TAMRA]).

Tm was calculated using PCRplan from PCGene version 6.7.

AT sequence (underlined) was introduced between GC clamp and primer sequence to optimize melting behavior of fragments in DGGE (45).

Tm was calculated using percent GC at 50 mM NaCl.

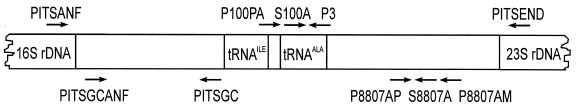

FIG. 1.

Target positions of PCR primers and probes in the ribosomal operon of Synechococcus spp. used in this study. The target sequence and the arrows indicating the 5′-to-3′ orientation of the oligonucleotides are not drawn to scale.

For DGGE, 10% polyacrylamide (acrylamide-N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide; 37.5:1) gels (0.8 mm) with 10 to 40% denaturing gradient were used, in which 100% is defined as 7 M urea and 40% (vol/vol) formamide. Electrophoresis was performed at 60°C for 4 h at 200 V with 1× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer (pH 8) containing 88 mM Tris, 88 mM boric acid, and 2 mM Na2-EDTA. Five microliters of GC-clamped PCR products from the amplified environmental DNA and 1 μl from isolated Synechococcus spp. as marker were applied per lane. The gels were stained with Sybr Gold nucleic acid gel stain (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany) for 30 min and documented under UV transillumination.

For confirmation of the identity of fragments, bands were excised from DGGE gels and transferred to 30 μl of elution buffer containing 0.5 M NH4-acetate and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8. The extraction of DNA followed the instructions of Ausubel et al. (2). In brief, the excised gel piece was shaken in the elution buffer overnight at 37°C, 800 rpm, and DNA was precipitated twice with cold ethanol. The extracted fragment was first dissolved in 20 μl of sterile water, diluted 20-fold, and used as template in PCR for reamplification (see above, second step of nested PCR). The migration behavior of these fragments was rechecked in 10 to 40% gradient gels before double-stranded sequencing was performed at GATC GmbH, Konstanz, Germany.

TNAs.

Primers and labeled probes for TNA (Table 1 and Fig. 1) were developed on the basis of ITS-1 sequences of Synechococcus strains isolated from the pelagic zone of Lake Constance as described previously (3). The TNA was conducted as reported previously, but the sample volume was reduced from 25 μl to 10 μl, of which 4 μl comprised supernatant from a DNA extraction with Chelex-100. The assays were pretreated for 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C before a two-step cycling program with 45 cycles of annealing and extension at 60°C for 60 s and 15-s denaturation at 94°C was carried out. Reactions were performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). A normalized fluorescence of ΔRQ = 0.02 was used as the threshold to identify the reaction cycle CT for construction of standard curves (11). The constant amplification efficiency, ɛc, of TNAs achieved with different primer-probe combinations was calculated from the slope s of log-linear calibration curves using the equation ɛc = 10−1/s − 1 (15). The reaction efficiency at the threshold value (ΔRQ = 0.02) was calculated for every TNA using a nonlinear least-squares fit of the sigmoid product curve determined in the TNA, calculated with the equation T(i + 1) = Ti [1 + Km (Ti + Km)−1] (32), in which T0 and Km were varied. In TNAs, the template and amplicon concentration Ti is equivalent to the fluorescence ΔRQi of the reporter in the ith cycle. The reaction efficiency is calculated at the threshold value by using the equation ɛ0.02 = Km (0.02+ Km)−1 (32; for details, see reference 3). For the least-squares fit, 5 to 13 successive cycles starting with the second cycle of consecutive positive ΔRQ values were used.

RESULTS

Genetic diversity of pelagic PE-rich Synechococcus spp. from Lake Constance.

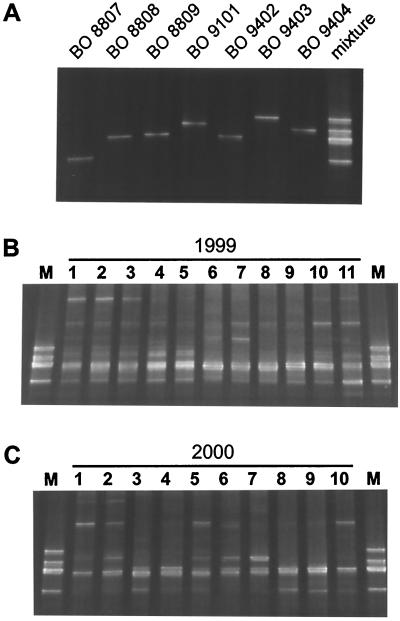

The diversity in the population of PE-rich Synechococcus spp. of Lake Constance was characterized by DGGE. To identify seven closely related PE-rich Synechococcus strains isolated from the pelagic zone, GC-clamped amplicons comprising 194 bp of the ITS-1 were produced with primers PITSGCANF and PITSGC in a single PCR (see Fig. 1 for primer positions). Every isolate exhibited a unique fragment, confirming the homogeneity of the unialgal but nonaxenic cultures (Fig. 2A) and the sequence conservation in this noncoding part of the ITS-1 among the two ribosomal operons detected in these strains by Southern analysis (Ernst et al., submitted). For analysis of the natural population, the picoplankton fraction of the epilimnion (0 to 8 m depth) of Lake Constance was obtained by filtration of 10 liters of water with a 30-μm mesh and a 3-μm filter to exclude predatory plankton. The APP was finally collected on filters with a 0.15-μm pore size. DNA extracted from sections of these filters was amplified by nested PCR. PCR products of the first reaction, conducted with primers targeting 16S rDNA and 23S rDNA, were not visible on agarose gel (data not shown). However, DGGE analysis of the short GC-clamped fragments produced from these templates in a nested PCR confirmed the high diversity of PE-rich strains expected from the low redundancy of isolation of single genotypes (30). Amplicons with similar melting behaviors to those of strains BO 8808, BO 8809, and BO 9402, which could not be separated on our gels, dominated in all samples collected in 1999 and 2000 (Fig. 2B and C). Also, strain BO 8807 seemed to be present in every sample of 1999 (Fig. 2B) and in several samples from the year 2000 (Fig. 2C). For confirmation, the amplicons comigrating with the amplicon of strain BO 8807 were excised and extracted from the DGGE gels, reamplified, and sequenced. From only one of the samples collected in 1999 was the sequence of strain BO 8807 recovered unequivocally (Fig. 2B, lane 11). In other samples of this year the sequence was either not detectable or was present in a background of at least one other fragment producing more than four ambiguous base positions but migrating to the same position in DGGE. In 2000, the presence of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 was confirmed in two samples (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 8).

FIG. 2.

Separation of PE-rich Synechococcus spp. from Lake Constance with DGGE. Ten to 40% gradients were used; for details, see Materials and Methods. (A) Migration behavior of seven PE-rich Synechococcus isolates from Lake Constance, for establishment of a marker. (B) Band pattern determined for environmental samples 1 to 11 from 1999 (compare with Fig. 4A). (C) Band pattern with environmental samples 1 to 10 from 2000 (compare with Fig. 4B). M, marker, represents a mixture of fragments depicted in panel A. One microliter from PCR mixtures with isolated strains (panel A and each strain in the marker) and 5 μl from assays with environmental DNA were applied per lane.

Calibration of quantitative TNAs.

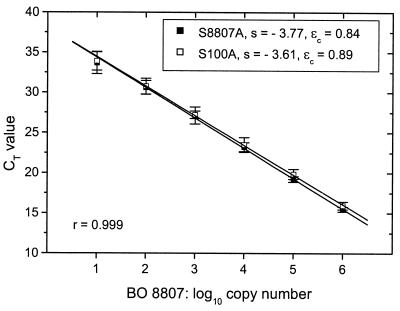

In this study, we quantified the cyanobacterial APP and a single ecotype, Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807, by applying two TNAs hereafter denoted as general TNA and strain-specific TNA. The relative positions of the primers and probes used in the TNAs differed from those used for GC-clamped fragments (Fig. 1) because of specific limitations in the construction of TaqMan probes (3). As TNA chemistry is still expensive, log-linear calibration curves for both primer-probe combinations were established for 10-μl-volume assays by plotting the PCR cycle number CT, at which the fluorescence signal passed the fluorescence threshold, versus the input copy number of genomes (Fig. 3). The input copy number of the DNA of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 used for calibration was estimated assuming a genome size of 3 Mbp (3). With 10-μl-volume assays, containing 4 μl of the DNA to be analyzed, calibration curves over 5 orders of magnitude were obtained. This represented a significantly smaller range than the 8 orders of magnitude achievable with 25-μl-volume assays (3), but it seemed sufficient for quantitative analysis of environmental samples. Calibration curves produced in 5-μl TNAs were not feasible (data not shown). The constant amplification efficiency of the PCR (15) was calculated from the negative slope of the calibration curve to be 0.84 for probe S8807A (amplicon size, 107 bp) and 0.89 for probe S100A (amplicon size, 98 bp). The slopes of the calibrations in the 10-μl-volume assays differed more than those reported for 25-μl-volume assays (0.86 for probe S8807A and 0.84 for probe S100A) (3).

FIG. 3.

Standard curves obtained by the threshold cycle method in real-time PCR. For TNAs, 10-ml-assay volumes contained approximately 101 to 106 copies of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 genomes, 5 μl of 2× TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (5 mM Mg2+ final concentration), 300 nM concentrations of primers, and 200 nM concentrations of probe. Primers used with probe S8807A were P8807AP and P8807AM; primers used with probe S100A were P100PA and P3. For PCR conditions, see Materials and Methods. Fluorescence threshold ΔRQ = 0.02; s = slope. Amplification efficiency was calculated as follows: ɛc = 10−1/s − 1. Error bars represent the standard deviations of six experiments.

Determination of cell and genome numbers and filtration losses.

The TNA was calibrated per number of genomes in the extracted DNA of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807, thus omitting a problem arising from the (unknown) number of ribosomal operons per genome. However, it is well known that the number of genomes per cell can vary and some cyanobacteria may harbor more than 10 copies of their haploid genome in a single cell (12, 20). To estimate genome numbers per Synechococcus cell, the cells of a 1-week-old culture exhibiting short cells and an 8-week-old culture with considerably elongated cells of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 were counted by epifluorescence microscopy and then collected on 0.15-μm filters for DNA extraction (Table 2). The number of genomes per cell determined with the two TNA formats described above was calculated to be 3.2 to 4.1 in young cultures (filter 1) and 2.6 to 3.1 in cultures with aged, elongated cells (filter 2). The comparison of the two TNAs showed that the calibrations deviated by 22% (filter 1) and 16% (filter 2).

TABLE 2.

Cell counts and genomes of autotrophic picoplankton detected by TNA probes S100A and S8807A

| Filter no. | Filter pore size (μm) | Water sample | Counted cells/ml (+ no. of BO 8807 cells added) | APP

|

Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomes detected/mld | Genomes/cell | Genomes detected/mle | Genomes/cell | ||||

| 1 | 0.15 | Cell-free lake water | + 1.43 × 104 BO 8807a | 4.56 × 104 | 3.2 | 5.81 × 104 | 4.1 |

| 2 | 0.15 | Cell-free lake water | + 6.87 × 104 BO 8807b | 1.75 × 105 | 2.6 | 2.12 × 105 | 3.1 |

| 3 | 3 | Pelagic 0-8 m 25/09/2001 | 7.89 × 104 | 3.63 × 104 | 0.98 | 5.7 × 101 | |

| 4 | 0.15 | Filtrate of filter 3 | NDc | 4.11 × 104} | |||

| 5 | 3 | Pelagic 0-8 m 25/09/2001 | 7.89 × 104 + 1.43 × 104 BO 8807a | 6.6 × 104 | 1.6 | 1.82 × 104 | |

| 6 | 0.15 | Filtrate of filter 5 | NDc | 8.32 × 104} | 2 × 104 | ||

| 7 | 3 | Pelagic 0-8 m 25/09/2001 | 7.89 × 104 + 6.87 × 104 BO 8807b | 1.36 × 105 | 1.7 | 8.46 × 104 | |

| 8 | 0.15 | Filtrate of filter 7 | NDc | 1.09 × 105} | 4.32 × 104 | ||

1-week-old culture.

8-week-old culture.

ND, not determined.

With probe S100A.

With probe S8807A.

Natural samples were routinely passed through a 30-μm and a 3-μm filter before the picoplankton was collected on a 0.15-μm filter. TNA analysis of the 3- and 0.15-μm filters showed that 46% of the genomes detected by the S100A probe were retained on the 3-μm filter (Table 2, filters 3 and 4). Similar loss was observed when the natural sample was spiked with a young culture of strain BO 8807 (filters 5 and 6), and higher loss (55%) occurred when the sample was spiked with an aged culture (filters 7 and 8). Combining the number of genomes detected on both filter types and comparing them with cell numbers revealed a much lower number of genomes per cell in samples containing the natural community than in the cultured strain BO 8807 (filters 3 to 8). These results caused us to analyze samples collected at different times, depths, and locations by epifluorescence microscopy and TNA (Table 3). Microscopic counting of the autofluorescent cells showed that in most experiments the 30-μm filter retained less then 15% of the APP, while the 3-μm filter was responsible for up to 65% filtration losses (average, 55%). Finally, the number of cells in water samples which had passed the 3-μm filter was compared with the number of genomes detectable with probe S100A in the TNA. The genome number per cell varied between 0.64 and 1.27 with an average of 0.91, indicating that a significant fraction of the natural autofluorescent APP was not detected by the TNA designed to recognize all Synechococcus spp. represented in our culture collection.

TABLE 3.

Numbers of cells and genomes of APP passing filters with 30- and 3-μm pore size

| Date (day/mo/yr) | Sampling site | Total APPa (cells/ml) | Cells passing 30-μm filter

|

Cells passing 3-μm filter

|

Genomes on 0.15-μm filterb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells/ml | % of total | Cells/ml | % of total | Genomes/ml | Genomes/celle | |||

| 14/08/2001 | Pelagic, 0-8 m | 1.5 × 105 | NDc | 6.22 × 104 | 41.5 | 3.96 × 104 | 0.64 | |

| Pelagic, 0 m | 1.38 × 105 | NDc | 6.59 × 104 | 47.8 | 4.46 × 104 | 0.68 | ||

| Littoral, 0 m | 1.54 × 105 | NDc | 5.94 × 104 | 38.6 | 5.19 × 104 | 0.87 | ||

| 28/08/2001 | Pelagic, 0-8 m | NDc | 9.56 × 104 | 4.83 × 104 | 50.5d | 6.02 × 104 | 1.25 | |

| Pelagic, 0 m | NDc | 1.25 × 105 | 5.11 × 104 | 40.9d | 5.45 × 104 | 1.07 | ||

| Littoral, 0 m | NDc | 1.21 × 105 | 4.64 × 104 | 38.3d | 4.89 × 104 | 1.05 | ||

| 11/09/2001 | Pelagic, 0-8 m | 1.01 × 105 | 7.52 × 104 | 74.5 | 3.53 × 104 | 35.0 | 3.34 × 104 | 0.95 |

| Pelagic, 0 m | 8.91 × 104 | 7.8 × 104 | 87.5 | 4.27 × 104 | 47.9 | 2.76 × 104 | 0.65 | |

| Littoral, 0 m | 8.91 × 104 | 7.9 × 104 | 88.7 | 4.36 × 104 | 48.9 | 2.72 × 104 | 0.62 | |

| 25/09/2001 | Pelagic, 0-8 m | 7.89 × 104 | 7.7 × 104 | 97.6 | 4.18 × 104 | 53.0 | 4.11 × 104 | 0.98 |

| Pelagic, 0 m | 7.98 × 104 | 6.59 × 104 | 82.6 | 4.18 × 104 | 52.4 | 5.32 × 104 | 1.27 | |

| Littoral, 0 m | 7.42 × 104 | 6.78 × 104 | 91.4 | 5.29 × 104 | 71.3 | 4.45 × 104 | 0.84 | |

No prefiltration.

Detected with probe S100A.

ND, not determined.

Percentage of cells per milliliter passing 30-μm filter.

Compared to cells passing 3-μm filter.

Abundance of APP and Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 in the years 1999 and 2000.

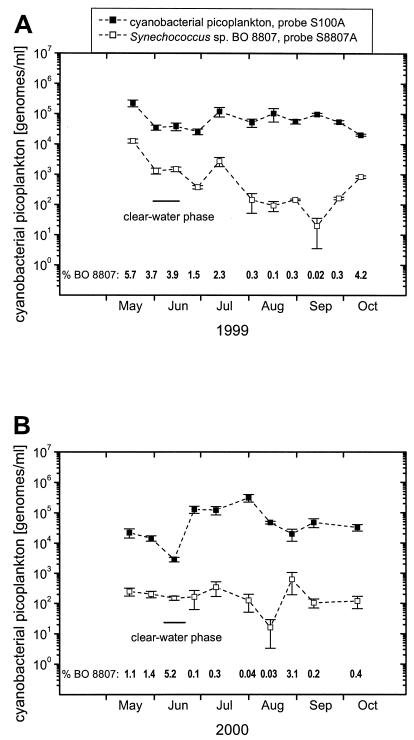

With the general TaqMan probe S100A and primer set P100PA/P3, genomes sharing genetic characteristics with all Synechococcus spp. represented in our culture collection were quantified during the growth seasons of the years 1999 and 2000. In addition, the same samples were analyzed using the strain-specific TaqMan probe S8807A and the primer set P8807AP/P8807AM exhibiting four mismatches with sequences of all known PE-rich Synechococcus spp. other than Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807. The results are presented as numbers of genomes per milliliter without corrections for prospective filtration losses. In 1999, numbers of genomes detected with the general primer-probe combination varied between 2 × 104 and 2 × 105 per ml (Fig. 4A). Genomes with the genetic signature of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 were detected in all samples collected in 1999, contributing as little as 2 × 101 (0.02%) and up to 1.3 × 104 (5.7%) genomes per ml. In the growth season of the year 2000, total variation in APP was larger, ranging from 2.9 × 103 to 3.1 × 105 genomes per ml (Fig. 4B). Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 was also detected in every sample of 2000. The highest relative abundances, 5.2 and 3.1%, were observed during the short clear-water phase in mid-June (D. Straile, personal communication) and in the summer population at the end of August only 2 weeks after the subpopulation had passed a minimum in the absolute and relative abundance.

FIG. 4.

Abundance of cyanobacterial picoplankton (Synechococcus spp.) and Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 in the pelagic zone of Lake Constance during the growth periods 1999 (A) and 2000 (B). Genomes per milliliter were determined by TNAs; the results were not corrected for prospective filtration losses. The percentage of BO 8807 is the relative genome numbers of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 (□) compared to the total genome number of Synechococcus spp. (▪), determined with probe S100A. Error bars represent standard deviations of three filter pieces analyzed in duplicate.

For quantitative analysis, it is important that the reaction efficiency of TNA observed at the threshold cycle is similar for DNA of the laboratory-grown strain used for calibration and DNA from environmental samples (3). This is of particular importance if a single genotype is quantified in a high background of closely related strains, as for strain BO 8807 in the APP of Lake Constance, because these conditions may lead to a suppression of the amplification of the minor component, as observed in competitive PCR (3, 32, 35). Therefore, the reaction efficiency ɛ0.02 was determined at the fluorescence threshold value ΔRQ = 0.02 by applying the equations deduced by Schnell and Mendoza (32; see Materials and Methods). In the TNA conducted for calibration, ɛ0.02 varied between 0.970 and 0.988 (data not shown), and similar values were achieved in the environmental samples (Table 4), indicating unbiased quantification of Synechococcus sp. BO 8807 genomes in all samples.

TABLE 4.

Amplification efficiency in TNA for quantification of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 in environmental samples

| Date of sampling (day/mo/yr) | Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 (genomes/ml) | Amplification efficiencya |

|---|---|---|

| 18/05/1999 | 12,640 ± 1,964 | 0.974 ± 0.0045 |

| 02/06/1999 | 1,306 ± 278 | 0.959 ± 0.0034 |

| 15/06/1999 | 1,483 ± 248 | 0.966 ± 0.0038 |

| 29/06/1999 | 379 ± 48 | 0.961 ± 0.0024 |

| 13/07/1999 | 2,725 ± 925 | 0.976 ± 0.0032 |

| 03/08/1999 | 144 ± 91 | 0.992 ± 0.0133 |

| 17/08/1999 | 94 ± 34 | 0.973 ± 0.0 |

| 31/08/1999 | 147 ± 9 | 0.969 ± 0.0025 |

| 14/09/1999 | 20 ± 16 | 0.969 ± 0.0032 |

| 28/09/1999 | 164 ± 16 | 0.972 ± 0.0110 |

| 12/10/1999 | 840 ± 91 | 0.964 ± 0.0031 |

| 16/05/2000 | 248 ± 73 | 0.954 ± 0.0095 |

| 30/05/2000 | 203 ± 50 | 0.967 ± 0.0008 |

| 14/06/2000 | 149 ± 23 | 0.999 ± 0.0 |

| 27/06/2000 | 165 ± 103 | 0.966 ± 0.0019 |

| 11/07/2000 | 341 ± 174 | 0.964 ± 0.0039 |

| 01/08/2000 | 125 ± 74 | 0.970 ± 0.0033 |

| 15/08/2000 | 16 ± 13 | 0.984 ± 0.0278 |

| 29/08/2000 | 624 ± 431 | 0.962 ± 0.0030 |

| 12/09/2000 | 105 ± 35 | 0.965 ± 0.0025 |

| 10/10/2000 | 119 ± 52 | 0.970 ± 0.0004 |

Defined by describing the yield y of PCR cycle n as yn + 1 = yn (1 + ɛ).

DISCUSSION

TNA performance.

As TNA chemistry is still expensive, we tested the application of small-volume TNAs to reduce costs. The 10-μl-volume assays with the two primer-probe combinations produced similar log-linear calibration curves (Fig. 3), but the difference in the slopes was larger than in the 25-μl assay format (3). It should be noted that due to the log-linear relation, quantitative PCR is very sensitive to variations in the slope of the calibration curve, and this may have contributed to a systematic error that was observed in quantification of the same DNA by two different TNAs, as shown in Table 2. Furthermore, the 10-μl assays with 4 μl of the DNA to be analyzed exhibited a significantly smaller detection range than 25-μl assays (3). Calibration curves produced in 5-μl TNAs were not feasible (data not shown). This is a notable difference from TaqMan assays performed for allele discrimination, for which 5-μl-volume TNAs gave satisfactory results (23). However, in the latter assays the relative fluorescence of the two probes, each targeting an allele, is determined in a single experiment and external calibration is not required, making these assays much less sensitive to errors introduced by manual pipetting of the template.

Critical factors in environmental analysis are the extraction efficiency, purity, and stability of nucleic acids from environmental samples (27, 28). In this study we employed Chelex-100, a chelating agent with an ion-exchanging feature, for efficient extraction of DNA from filters. Serial dilution of this environmental DNA and application in 10-μl TNAs did not indicate any inhibitory effects of the 4 μl of the extract (data not shown). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that the reaction efficiency of TNAs observed at the threshold cycle is similar for DNA of the laboratory-grown strain used for calibration and for DNA from environmental samples (Table 4). This ensured that false quantification caused by PCR inhibitors or by competitive conditions in the PCR did not occur.

Tracing of isolated strains by TNA and DGGE.

In this study, real-time PCR with TaqMan probes and DGGE were used to trace phylogenetically closely related, PE-rich Synechococcus spp. that form subpopulations in the APP of Lake Constance. For the amplifications in nested PCR for DGGE and TNA for quantitative tracing on the ecotype level, target sequences of primers and probes were selected that are conserved in the ribosomal operon of 12 PE- and PC-rich strains isolated from Lake Constance and in eight additional Synechococcus spp. isolated from other fresh and brackish waters, comprising five different lineages in a 16S rRNA inferred phylogenetic tree (Ernst et al., submitted). The target sequences of the PCR used to produce a GC-clamped fragment for DGGE were selected to amplify all known PE-rich Synechococcus spp. of the pelagic habitat. Additionally, a strain-specific primer-probe combination was designed for quantitative detection by TNA of a single ecotype, Synechococcus sp. BO 8807. From the high amplification efficiency ɛ0.02 at the cycle used for quantification (Table 4), which indicates the absence of homologous fragments that are amplified but not detected by the TaqMan probe, we can assume that this primer-probe combination was highly specific for tracing of Synechococcus sp. BO 8807 in the natural habitat. Hence, the detection of genome numbers of this strain over 4 orders of magnitude during the two periods of observation was possible (Fig. 4). Not only the absolute genome numbers but also the fractional contribution of strain BO 8807 to the TNA-quantified population of picocyanobacteria were highly variable. The discrepancies between the two quantitative determinations could not be explained without a complementary study of the population by DGGE, demonstrating frequent shifts in the genetic composition of the population throughout the observation period (Fig. 2). However, while TNA allowed tracing of 10 genomes in assays for the construction of standard curves (Fig. 3) or 16 BO 8807 genomes per ml in the habitat (Table 4), tracing of single ecotypes by DGGE was not always possible. The latter method is not only limited by the relatively low sensitivity of gel-based analysis methods of PCR products but also by a PCR bias, known from competitive PCR, which leads to suppression of a minor constituent in samples containing more than one template (3, 32). This explains why Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807, which by quantitative analysis was shown to frequently contribute less than 1% to the TNA-quantified population (Fig. 4), was only sporadically detected by DGGE.

Another problem arose from the number of variable positions (22 in the seven isolated strains) in the 194-bp sequence of genuine ITS-1 in the GC-clamped fragments, which apparently can lead to compensatory effects in the melting behavior of different fragments. This problem precluded the visualization of shifts between genotypes that dominated the populations in both years, of which we have three cultivated strains, BO 8808, BO 8809, and BO 9402. This problem also obscured the detection of strain BO 8807 in the year 1999 (Fig. 2), but the absence of the comigrating fragment in the year 2000 demonstrated that even among codominant genotypes a year-to-year variability can be observed in the APP.

Cell and genome numbers.

Comparison of microscopic cell counts and determination of number of genomes by TNA resulted in 2.6 to 4.1 genomes per cell in the cultivated Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807, depending on the age of the culture and the TNA used (Table 2). However, the genome number calculated per cell of the natural population was ≈1 (Tables 2 and 3). This low number could not be explained by a lowered DNA extraction efficiency from filters, because the addition of cultivated strain BO 8807 to a natural sample yielded the genome number expected from the consideration of the individual determinations (Table 2). We therefore have to consider that the APP is dominated by Synechococcus spp. that do not share characteristics of the cultivated strain BO 8807. The most obvious deviant characteristic of this strain are elongated cells containing several genomes (Table 2), which appear in stationary cultures, while this may not be the case with coccoid species. Another possibility is that genera of the APP are missing in our culture collection that were not amplified by the PCR primers used in the general Synechococcus TNA (see above). Thus, although an experimentally determined 1:1 relation of genomes and cells per milliliter was obtained (Tables 2 and 3), a general application of a conversion factor of 1 remains questionable.

Population dynamics in the APP.

In the years 1999 and 2000 we determined the number of genomes of Synechococcus spp. with known genetic profiles contributing to the cyanobacterial APP of Lake Constance. These known species in the APP showed two abundance patterns known from previous studies, in which cells were counted by epifluorescence microscopy (10). An intensive spring bloom with up to 2 × 105 genomes per ml was observed in May 1999 (Fig. 4A). It was terminated by a drop of 1 order of magnitude occurring at the start of the clear-water phase at the end of May (D. Straile, personal communication). The APP recovered in July and diminished again in October, when stratification of the water column was lost. In 2000, the known species in the APP were much less abundant in May (2 × 104 genomes per ml), but nevertheless genome number decreased by more than 1 order of magnitude during the clear-water phase in mid-June (D. Straile, personal communication) (Fig. 4B). Unusually though, the population recovered immediately after the clear-water phase to reach more than 105 genomes per ml until in mid-August the population started to decline (Fig. 4B). In both years, organisms with the ITS-1 sequence signature of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 were detected in every sample examined, but in most cases they contributed less than 5% to the total APP. The development of this subpopulation seemed to be largely independent from that of the other members of the APP, as demonstrated by the wide range of relative abundances in both years. Interestingly though, the range of relative abundance, 0.02 and 5.7% in 1999 and 0.03 to 5.2% in 2000, and a high relative abundance during the clear-water phase were similar in both years. In contrast to other Synechococcus ecotypes we have in culture, Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807 forms rods completely covered by a regularly structured glycosylated protein, forming an S-layer (6). We assumed that this surface structure was responsible for reduced predation in feeding experiments with a chrysomonad and a nanoflagellate from Lake Constance (1, 25). These experimental observations may relate to the high relative abundance of this strain during the clear-water phase. However, the data demonstrate that during summer, possibly due to succession in the heterotrophic nanoplankton, this protection diminished. In both years, a relative and absolute minimum of Synechococcus sp. strain BO 8807, about 20 genomes per ml, was observed at the end of the summer bloom. Production of and lysis by viruses were unlikely causes of this decline, because the ecotype had a low abundance throughout the summer population (up to several hundred genomes per milliliter), which is at or below the threshold concentration of hosts required for successful phage replication in pure cultures (16, 43).

Concluding remarks.

In this study we showed for the first time the dynamics of populations and subpopulations in the autotrophic picoplankton of a deep lake. The quantitative approach with TNA unveiled shortcomings in the sampling procedure and led to the conclusion that there must be a group of Synechococcus-type cyanobacteria not detected by our PCR-based assays. However, within the group of detectable organisms the wide dynamic range of TNA is an invaluable advantage in studying dynamics in microbial populations. On the other hand, diversity cannot be demonstrated by TNA and, thus, cannot replace DGGE. The study also showed that the use of ITS-1 as a target and the use of specific primers facilitated the recovery of signals from isolated strains in their natural habitat.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to BITg, Biotechnologie Institut Thurgau an der Universität Konstanz, Tägerwilen, Switzerland, for utilization of the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system, and we thank P. Herman for help in data evaluation.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through Sonderforschungsbereich 454 “Bodenseelitoral.”

Footnotes

This is publication 2846 of NIOO, Centre for Estuarine and Coastal Ecology, Yerseke, The Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1.Assmann, D. 1998. Nahrungsselektion und Nahrungsverwertung Chroococcaler Cyanobakterien durch Heterotrophe Nanoflagellaten. Ph.D. thesis. Universität Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany.

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1992. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Becker, S., P. Böger, R. Oehlmann, and A. Ernst. 2000. PCR bias in ecological analysis: a case study for quantitative Taq nuclease assays in analyses of microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4945-4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst, A. 1991. Cyanobacterial picoplankton from Lake Constance. I. Isolation by fluorescence characteristics. J. Plankton Res. 13:1307-1312. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernst, A., S. Becker, K. Hennes, and C. Postius. 2000. Is there a succession in the autotrophic picoplankton of temperate zone lakes?, p. 623-629. In C. R. Bell, M. Brylinski, and P. Johnson-Green (ed.), Microbial biosystems: new frontiers. Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Microbial Ecology. Atlantic Canada Society for Microbial Ecology, Halifax, Canada.

- 6.Ernst, A., C. Postius, and P. Böger. 1996. Glycosylated surface proteins reflect genetic diversity among Synechococcus species of Lake Constance. Arch. Hydrobiol. Adv. Limnol. 48:1-6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst, A., G. Sandmann, C. Postius, S. Brass, U. Kenter, and P. Böger. 1992. Cyanobacterial picoplankton from Lake Constance. II. Classification of isolates by cell morphology and pigment composition. Bot. Acta 105:161-167. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris, J. F., and B. Palenik. 1998. Niche adaptation in ocean cyanobacteria. Nature 396:226-228. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer, S. G., and L. S. Lerman. 1979. Length-independent separation of DNA restriction fragments in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Cell 16:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaedke, U., and T. Weisse. 1998. Seasonal and interannual variability of picocyanobacteria in Lake Constance (1987-1997). Arch. Hydrobiol. Adv. Limnol. 53:143-158. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heid, C. A., J. Stevens, K. J. Livak, and P. M. Williams. 1996. Real-time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 6:986-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herdman, M., J. B. Janvier, J. B. Waterbury, R. Rippka, R. Y. Stanier, and M. Mandel. 1997. Deoxyribonucleic acid base composition of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111:63-71. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland, P. M., R. D. Abramson, R. Watson, and D. H. Gelfand. 1991. Detection of specific polymerase chain reaction product by utilizing the 5′→3′ exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7276-7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huisman, J., and J. Weissing. 1999. Biodiversity of plankton by species oscillation and chaos. Nature 402:407-410. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein, D., P. Janda, R. Steinborn, M. Müller, B. Salmons, and W. H. Günzburg. 1999. Proviral load determination of different feline immunodeficiency virus isolates using real-time polymerase chain reaction: influence of mismatches on quantification. Electrophoresis 20:291-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokjohn, T. A., G. S. Sayler, and R. V. Miller. 1991. Attachment and replication of Pseudomonas aeroginosa bacteriophages under conditions simulating aquatic environments. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:661-666. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laloui, W., K. A. Palinska, R. Rippka, F. Partensky, N. Tandeau de Marsac, M. Herdman, and I. Iteman. 2002. Genotyping of axenic and non-axenic isolates of the genus Prochlorococcus and the OMF-‘Synechococcus' clade by size, sequence analysis or RFLP of the internal transcribed spacer of the ribosomal operon. Microbiology 148:453-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, L. G., C. R. Connel, and W. Bloch. 1993. Allelic discrimination by nick-translation PCR with fluorogenic probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3761-3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak, K. J., S. J. A. Flood, J. Marmaro, W. Giusti, and K. Deetz. 1995. Oligonucleotides with fluorescent dyes at opposite ends provide a quenched probe system useful for detecting PCR product and nucleic acid hybridization. PCR Methods Appl. 4:357-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llabarre, J., F. Chauvat, and P. Thuriaux. 1989. Insertional mutagenesis by random cloning of antibiotic resistance genes into the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 171:3449-3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyerhans, A., J.-P. Vartanian, and S. Wain-Hobson. 1990. DNA recombination during PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:1687-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore, L. R., G. Rocap, and S. W. Chisholm. 1998. Physiology and molecular phylogeny of coexisting Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Nature 393:464-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morin, P. A., R. Saiz, and A. Monjazeb. 1999. High-throughput single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping by fluorescent 5′ exonuclease assay. BioTechniques 27:538-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison, C., and F. Gannon. 1994. The impact of the PCR plateau phase on quantitative PCR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1219:493-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller, H. 1996. Selective feeding of a freshwater chrysomonad, Paraphysomonas sp., on chroococcoid cyanobacteria and nanoflagellates. Arch. Hydrobiol. Adv. Limnol. 48:63-71. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muyzer, G., and K. Smalla. 1998. Application of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE) in microbial ecology. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:127-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nogva, H. K., A. Bergh, A. Holck, and K. Rudi. 2000. Application of the 5′-nuclease PCR assay in evaluation and development of methods for quantitative detection of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4029-4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nogva, H. K., K. Rudi, K. Naterstad, A. Holck, and D. Lillehaug. 2000. Application of 5′-nuclease PCR for quantitative detection of Listeria monocytogenes in pure cultures, water, skim milk, and unpasteurized whole milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4266-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postius, C., and A. Ernst. 1999. Mechanisms of dominance: coexistence of picocyanobacterial genotypes in a freshwater ecosystem. Arch. Microbiol. 172:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Postius, C., A. Ernst, U. Kenter, and P. Böger. 1996. Persistence and genetic diversity among strains of phycoerythrin-rich cyanobacteria from the picoplankton of Lake Constance. J. Plankton Res. 18:1159-1166. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riemann, L., G. F. Steward, and F. Azam. 2000. Dynamics of bacterial community composition and activity during a mesocosm diatom bloom. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:578-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnell, S., and C. Mendoza. 1997. Enzymological considerations for a theoretical description of the quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction (QC-PCR). J. Theor. Biol. 184:433-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sommer, U., M. Z. Gliwicz, W. Lampert, and A. Duncan. 1986. The PEG-model of seasonal succession of planktonic events in fresh waters. Arch. Hydrobiol. 106:433-471. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanier, R. Y., R. Kunisawa, M. Mandel, and G. Cohen-Baziere. 1971. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol. Rev. 35:171-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki, M. T., and S. J. Giovannoni. 1996. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:625-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbach, E., D. J. Scanlan, D. L. Distel, J. B. Waterbury, and S. W. Chisholm. 1998. Rapid diversification of marine picoplankton with dissimilar light harvesting structures inferred from sequences of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (cyanobacteria). J. Mol. Evol. 46:188-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Hannen, E. J., G. Zwart, M. P. van Agterveld, H. J. Gons, J. Ebert, and H. J. Laanbroek. 1999. Changes in bacterial and eukaryotic community structure after mass lysis of filamentous cyanobacteria associated with viruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:795-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Wintzingerode, F., U. B. Göbel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Micobiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh, P. S., D. A. Metzger, and R. Higuchi. 1991. Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. BioTechniques 10:506-513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, G. C.-Y., and Y. Wang. 1997. Frequency of formation of chimeric molecules as a consequence of PCR coamplification of 16S rRNA genes from mixed bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4645-4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisse, T., and U. Kenter. 1991. Ecological characteristics of autotrophic picoplankton in a prealpine lake. Int. Rev. Gesamt. Hydrobiol. 76:493-504. [Google Scholar]

- 42.West, N. J., W. A. Schönhuber, N. J. Fuller, R. I. Amann, R. Rippka, A. F. Post, and D. J. Scanlan. 2001. Closely related Prochlorococcus genotypes show remarkably different depth distributions in two oceanic regions as revealed by in situ hybridization using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides. Microbiology 147:1731-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiggins, B. A., and M. Alexander. 1985. Minimum bacterial density for bacteriophage replication: implications for significance of bacteriophages in natural ecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:19-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Worden, A. Z., S. W. Chisholm, and B. J. Binder. 2000. In situ hybridization of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (marine cyanobacteria) spp. with rRNA-targeted peptide nucleic acid probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:284-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, Y., V. M. Hayes, J. Osinga, I. M. Mulder, M. W. Looman, C. H. Buys, and R. M. Hofstra. 1998. Improvement of fragment and primer selection for mutation detection by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:5432-5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]